Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also

termed ‘hemophagocytic syndrome’ or ‘macrophage activation

syndrome’, is a life-threatening condition characterized by

pathological inflammatory responses (1). Clinical manifestations of HLH include

recurrent fever, cytopenia, splenomegaly and sepsis-like syndrome,

potentially culminating in multiple organ failure (MOF). HLH is

classified into primary and secondary forms. Primary HLH is a

hereditary condition predominantly observed in pediatric

populations. Secondary HLH stems from malignancies, autoimmune

diseases or idiopathic causes (2).

Although numerous malignancies can accompany HLH,

lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (LAHS) is particularly

prevalent. Malignant lymphoma is categorized into low-grade and

high-grade lymphoma. It is worth noting that LAHS can manifest as a

symptom of high-grade lymphoma rather than low-grade lymphoma

(3,4) and is associated with poor prognosis

(5). Although LAHS is usually

treated with corticosteroid therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy for

lymphoma (6), the significance of

surgical intervention remains unclear, as no surgical cases have

been reported to date.

The present study described a challenging case of

lymphoma-associated splenomegaly, which led to severe HLH following

splenectomy. It was possible to save the patient through timely

splenectomy to reduce the tumor burden, enabling safe and effective

steroid pulse therapy and chemotherapy.

Case report

A 71-year-old man with a medical history of

hypertension and hyperuricemia presented to the primary hospital,

Japan Baptist Hospital's Department of Internal Medicine (Kyoto,

Japan), with fatigue and anorexia in February 2023. Laboratory test

results revealed anemia [hemoglobin (Hb), 10 g/dl; normal range,

12–16 g/dl], thrombocytopenia [platelet count (Plt),

100×103/µl; normal range, 150–450×103/µl],

elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels (LDH, 627 U/l; normal range,

140–271 U/l) and a markedly elevated ferritin level (6,210 ng/ml;

normal range, 15–500 ng/ml). In addition, the patient's soluble

interleukin 2 receptor (sIL-2R) level was significantly increased

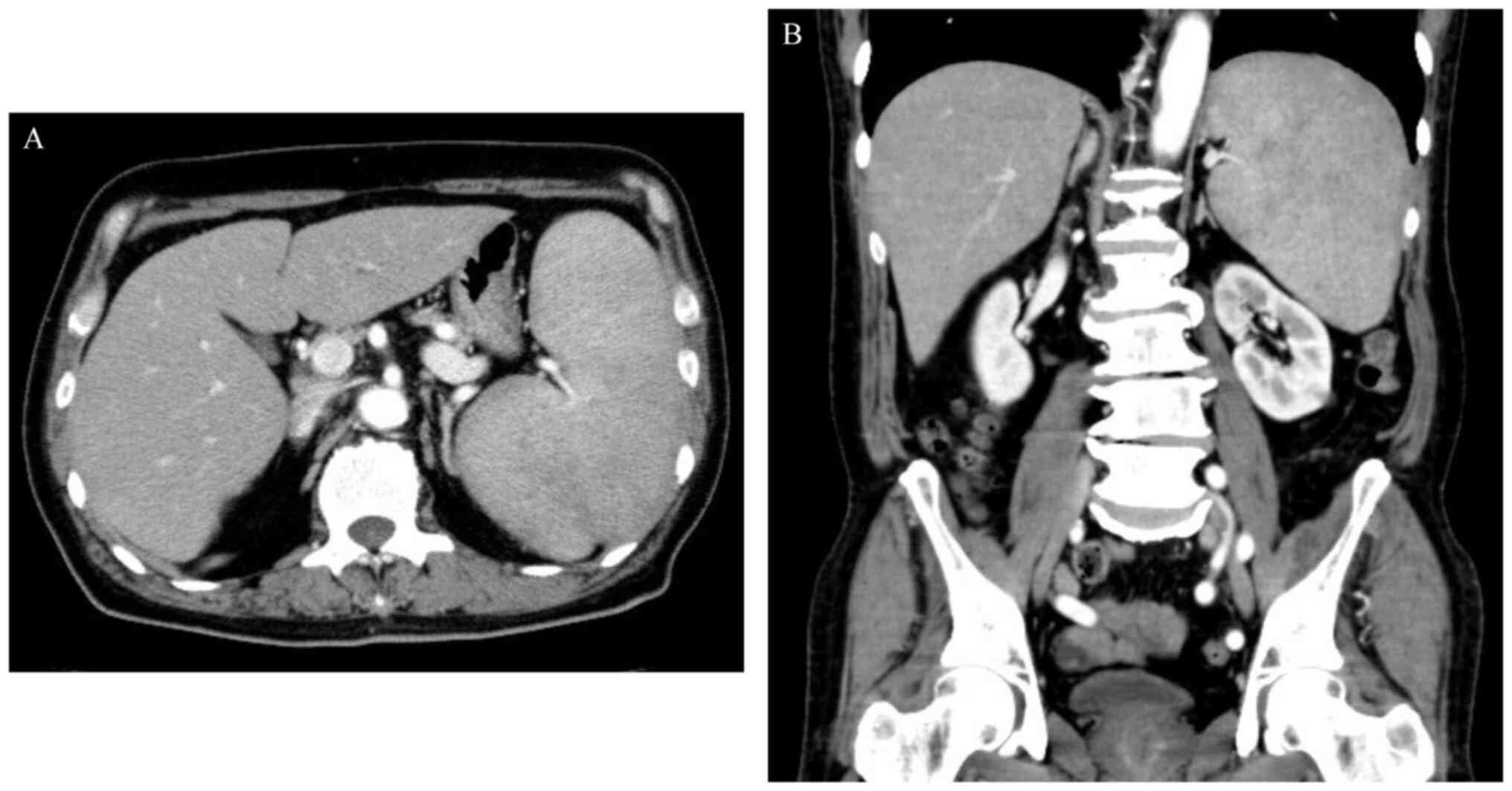

at 11,328 U/ml (normal range, 122–496 U/ml). Abdominal computed

tomography (CT) revealed splenomegaly, without enlarged lymph nodes

(Fig. 1).

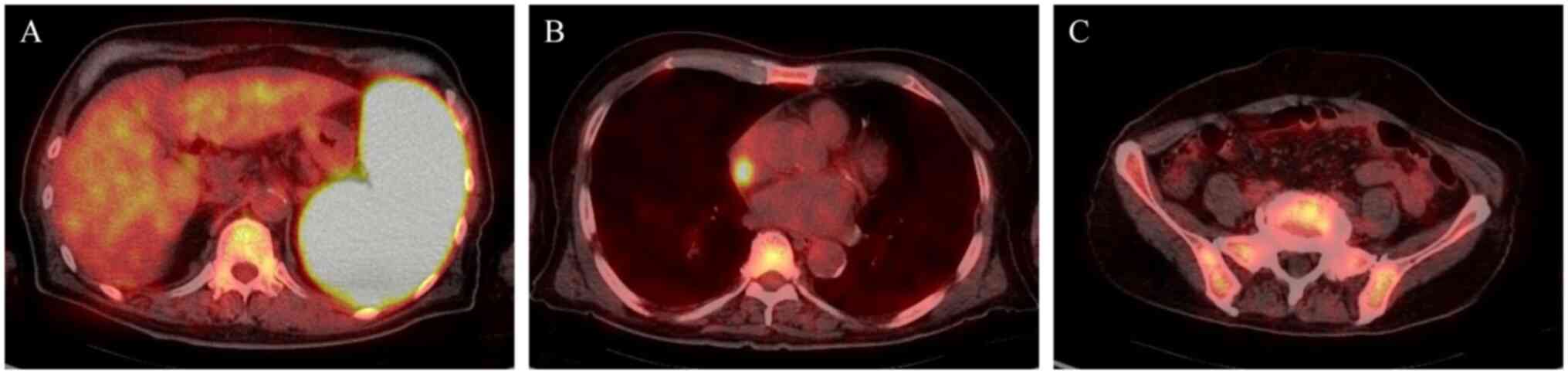

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography

(FDG-PET)/CT showed the most pronounced increased uptake of FDG in

the spleen, followed by the right atrium and the bone marrow

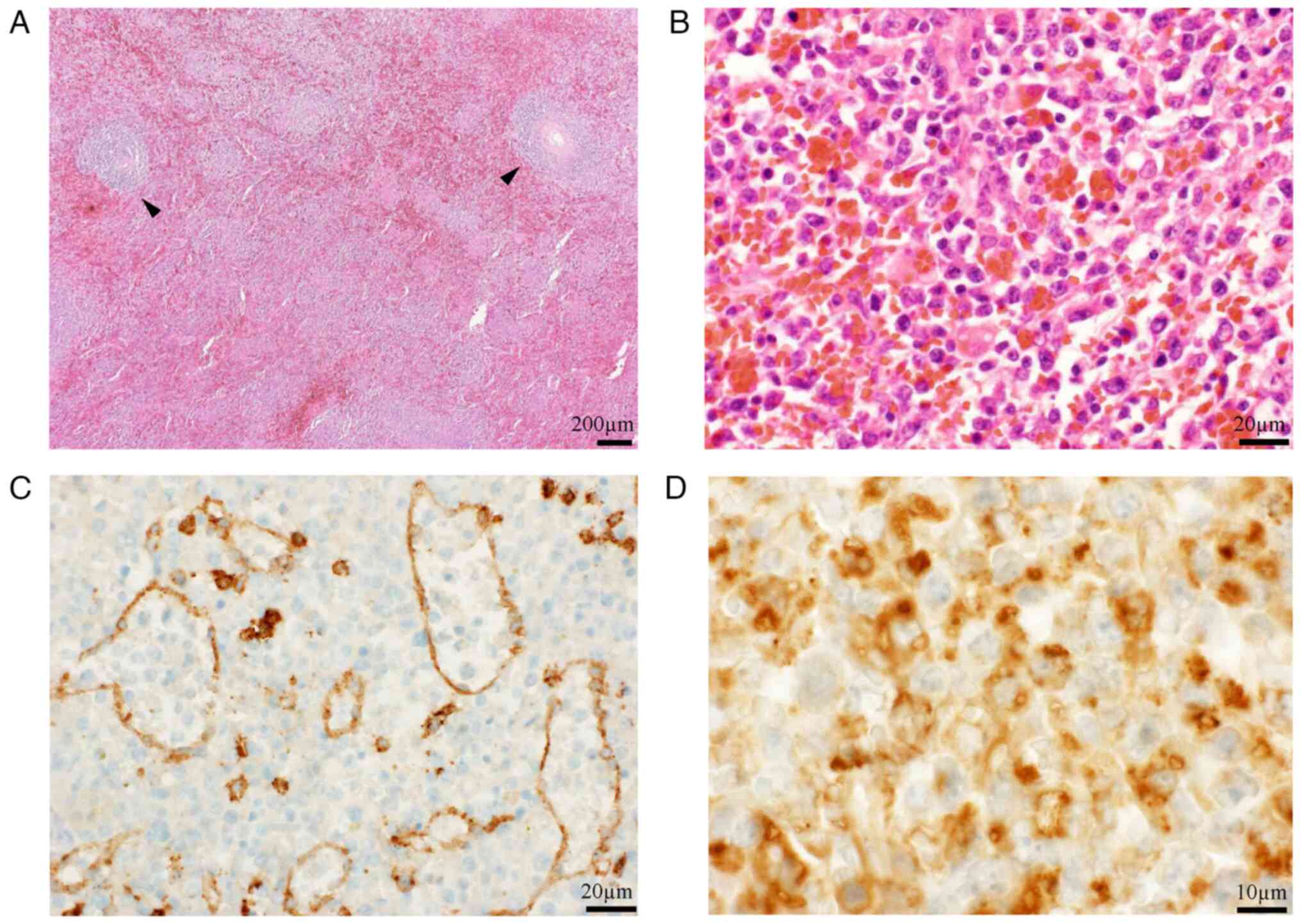

(Fig. 2). The bone marrow biopsy

identified an increase in small lymphocytes with occasional large

cells on Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) staining (7) (Fig. 3A and

B). Clonality was confirmed through cytogenetic examination of

T cell receptor γ chain Jγ rearrangement (8,9) using

Southern blot analysis (10) with

restriction enzymes EcoRI, BamHI and HindIII (Takara Bio, Inc.)

(Fig. 3C).In addition, clonality

was supported by flow cytometric analysis with CD45 gating

(11) (Fig. 3D). Flow cytometry utilized a panel

of pre-diluted antibodies from BD Biosciences, including CD45

(PerCP) (cat. no. 347464), CD2 (FITC) (cat. no. 347593), CD19

(BV421) (cat. no. 562440), CD3 (PE) (cat. no. 347347), CD8 (BV510)

(cat. no. 563919), CD4 (APC-H7) (cat. no. 641398), CD25 (BV421)

(cat. no. 562442), CD5 (FITC) (cat. no. 347303), CD23 (BV421) (cat.

no. 562707), CD10 (PE) (cat. no. 340921), CD20 (APC-H7) (cat. no.

641396), CD11c (BV510) (cat. no. 563026), CD16 (BV510) (cat. no.

563830), CD56 (APC) (cat. no. 341025), CD30 (FITC) (cat. no.

341644), CD7 (APC) (cat. no. 561604), kappa light chains (PE) (cat.

no. 346601), and lambda light chains (APC-H7) (cat. no. 656648),

all used according to the manufacturer's protocol; however, a

definitive diagnosis of the histological subtype could not be

established.

Despite the abnormal laboratory data, the patient's

activities of daily living were relatively preserved. After

comprehensive assessment under outpatient conditions, elective

surgery was planned to obtain a histological diagnosis two weeks

after the initial presentation. On admission, 2 days

preoperatively, the patient exhibited a spike fever of 39°C and

progressive cytopenia (Hb, 8.6 g/dl; and Plt, 62×103/µl)

was observed. The next day (the day before surgery), 20 units of

platelet concentrate were transfused, but the Plt count had dropped

to 55×103/µl on the operative day. Due to the patient's

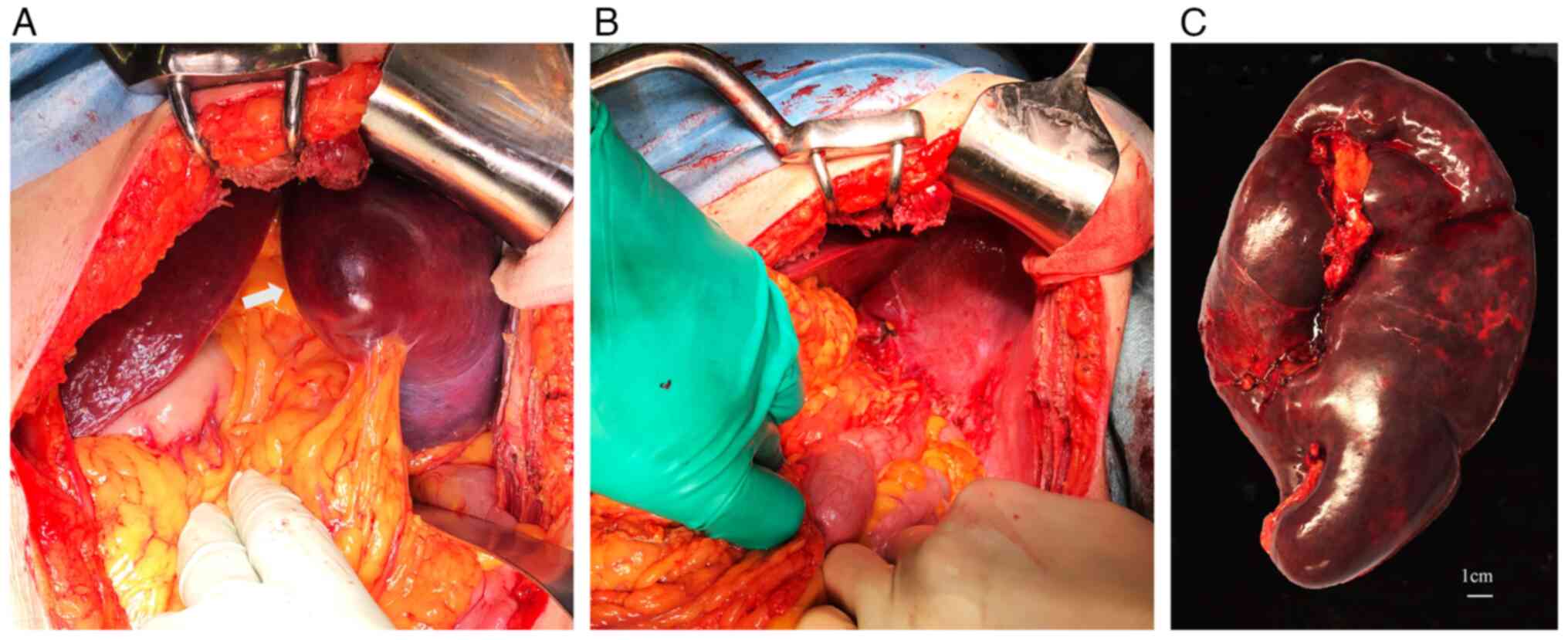

significant splenomegaly, laparotomy was selected instead of

laparoscopy. Splenectomy was eventually performed via a left

subcostal incision (Fig. 4A). The

procedure involved the separate ligation of the splenic artery and

vein, and the spleen was extracted by stapling the tail of the

pancreas at the splenic hilum (Fig.

4B). The operation lasted for 100 min, with an estimated blood

loss of 600 ml. The excised specimen weighed 1,100 g (Fig. 4C). Subsequent histological

examination confirmed the diagnosis of low-grade B-cell lymphoma

with focal transformation to high-grade lymphoma with severe

hemophagocytosis on HE staining (7)

(Fig. 5). To confirm red-pulp, but

not white-pulp, involvement of the lymphoma, immunohistochemistry

was performed using an anti-CD8 antibody (cat. no. M7103; DAKO) at

a dilution of 1:100, and Bentana ultraView DAB universal kit (Roche

Diagnostics) for identification of sinus endothelial cells

according to the manufacturers' standard protocols. The lymphoma

predominantly involved the red pulp with some remaining atrophic

white pulp, and the histological diagnosis was

immunohistochemically confirmed using a CD68 probe (cat. no.

NCL-CD68-KP1; Novocastra) at a dilution of 1:400 (Fig. 5). Thus, splenic marginal-zone

lymphoma (commonly seen in this organ) could not be included in the

histologic differential diagnosis; the lymphoma was finally

characterized as unclassifiable. The patient was diagnosed with

stage IVB disease according to the Ann Arbor Classification System

(12).

Despite having undergone surgery, the pre-existing

symptoms of intermittent fever and fatigue did not improve

postoperatively. The patient exhibited low blood pressure and

required temporary dopamine administration. On postoperative day

(POD) 3, a rapid decrease in the Plt count (62×103/µl)

and elevation in LDH (1,948 U/l), aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

(234 U/l; normal range, 8–48 U/l), total bilirubin (T-Bil) (6.6

mg/dl; normal range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dl), direct bilirubin (D-Bil) (4.5

mg/dl; normal range, 0.0–0.3 mg/dl) and C-reactive protein (CRP)

levels (18.56 mg/dl; normal range, <0.5 mg/dl) were observed

(Fig. 6). CT scanning did not

detect any postoperative complications, such as pancreatic leakage.

To exclude the possibility of drug-induced liver damage or

potential embolism, medication adjustments were made and heparin

was administered. However, the patient's condition further

deteriorated.

| Figure 6.Detailed treatment course of the

patient. Line graph illustrating changes in key biochemical markers

(T-Bil, AST, LDH, Ferritin and sIL-2R) over time, starting from the

preoperative period. Note that a significant improvement is

observed following steroid pulse therapy and subsequent

chemotherapy for the lymphoma. The steroid administration was

switched from intravenous injection of mPSL to oral intake of

prednisolone on POD 14. T-Bil, total bilirubin (normal range,

0.3–1.2 mg/dl); AST, aspartate transaminase (normal range, 8–48

U/l); LDH, lactate dehydrogenase (normal range, 140–271 U/l);

Ferritin (normal range, 15–500 ng/ml); sIL-2R, soluble interleukin

2 receptor (normal range, 122–496 U/ml); mPSL, methylprednisolone;

POD, postoperative day; R-EPOCH, Rituximab, Etoposide, Prednisone,

Oncovin, Cyclophosphamide and Hydroxydaunorubicin. |

Consequently, the patient was transferred to a

tertiary care institution on POD 5, where he was admitted to the

intensive care unit (ICU). Laboratory reassessment revealed the

following abnormalities: Decrease in Hb (8.3 g/dl) and Plt

(47×103/µl); and significant elevations in LDH (3,616

U/l), AST (691 U/l), alanine aminotransferase (112 U/l; normal

range, 7–55 U/l), T-Bil (21 mg/dl), D-Bil (17 mg/dl), creatinine

(1.77 mg/dl; normal range, 0.5–1.2 mg/dl), CRP (23.44 mg/dl),

ferritin (25,197 ng/ml) and sIL-2R (30,420 U/ml). The patient also

exhibited hypoglycemia, with a blood glucose level of 25 mg/dl

(normal range: 70–99 mg/dl), indicative of hepatic failure.

However, since coagulation markers, such as prothrombin time and

activated partial thromboplastin clotting time, were normal, plasma

exchange therapy was deemed unnecessary (13).

The diagnosis of concurrent HLH was made and

treatment with immunosuppressive therapy, steroid pulse therapy at

1,000 mg/day for 3 days, was immediately initiated under mechanical

ventilation and continuous hemodiafiltration. Following this

intervention, liver dysfunction was gradually ameliorated; the

steroid dosage was tapered down (Fig.

6). The patient was extubated on POD 12 and subsequent

chemotherapy for lymphoma with the R-EPOCH regimen (Rituximab,

Etoposide, Prednisone, Oncovin, Cyclophosphamide and

Hydroxydaunorubicin) was initiated on POD 14. Considering the

hepatic dysfunction and tumor load, the initial dose of the regimen

was reduced to 50%, and the administration of rituximab was delayed

until POD 26. Bradycardia with a heart rate of 40 beats/min was

transiently observed, presumably due to the infiltration of

lymphoma into the sinoatrial node (Fig.

2B). However, there was no need for the placement of a

pacemaker. After chemotherapy initiation, this bradycardia

gradually improved, and further improvements in liver function were

observed. The patient was discharged from the ICU on POD 23 and

hemodialysis was discontinued on POD 30.

After experiencing gastric ulcer bleeding on POD 19

and acute pancreatitis on POD 27 as complications of steroid

treatment, which were successfully managed with hemostasis and

endoscopic drainage, a second course of R-EPOCH therapy was

initiated on POD 77. After the patient's condition stabilized, he

was transferred back to our primary hospital on POD 93 and was

discharged home on POD 168. At eight months after the onset, the

patient remains alive with improved performance status and his

treatment is ongoing, specifically continuing with consolidation

therapy for lymphoma. He is undergoing outpatient consultations

with a frequency of approximately once every two weeks.

Discussion

HLH comprises a spectrum of conditions driven by

uncontrolled inflammatory reactions. Among secondary HLH,

malignancy-related HLH is predominantly associated with non-Hodgkin

lymphomas. Of note, LAHS demonstrates a dismal prognosis with an

average survival of only 37 days after treatment initiation

(5), and this condition has been

extensively studied (14,15). LAHS is itself a fatal condition,

which often results in death despite intensive treatment with

corticosteroid pulse therapy and cytotoxic chemotherapy (4,16–20).

Splenomegaly, or an increased standardized uptake

value on FDG-PET, is a frequent manifestation of numerous

hematological disorders, including malignant lymphomas (21). An enlarged spleen may act as a

reservoir for malignant cells, potentially accelerating disease

progression. Splenectomy can alleviate related symptoms, such as

abdominal discomfort and cytopenia, while allowing for diagnosis

based on histopathological examination. This procedure may also

offer therapeutic benefits, particularly in cases of B-cell splenic

lymphoma (22–24). There is a distinct subset of HLH

cases of unknown etiology that poses a clinical challenge. In such

cases, splenectomy has been shown to serve as an effective

diagnostic and therapeutic strategy (25–27),

while a clinical trial is currently underway to validate its

efficacy (NCI02862054). It can be inferred from these observations

that the role of splenectomy in the context of splenic lymphoma and

secondary HLH of idiopathic etiology has been established.

Malignant HLH is associated with MOF, leading to

high rates of morbidity and mortality. In the present case, the

preoperative progressive decrease in Hb and Plt indicates that

signs of MOF were already present. If only chemotherapy had been

administered without surgical intervention, there would have been a

potential risk of triggering a severe tumor lysis syndrome and

exacerbating pre-existing HLH due to the high tumor burden

(28). Therefore, without

splenectomy, the patient may have experienced more disastrous

outcomes, such as the progression of MOF, splenic rupture (29), and even death. Retrospectively, the

splenectomy did have a role in reducing the tumor burden, which in

turn facilitated safer and more effective chemotherapy.

However, a critical question remains in the present

case: Despite the removal of a significant tumor mass, why did the

patient still develop severe HLH? Based on the postoperative course

of the case, it is evident that surgery alone failed to halt the

development of HLH, with hypotension observed postoperatively,

suggesting a concurrent cytokine storm. Initially, it was assumed

that his splenic lymphoma was primarily indolent. However, highly

elevated ferritin levels at the presentation suggested the presence

of HLH preoperatively. Pathological findings of the spleen

supported this, further revealing high-grade lymphoma

transformation. There is a high likelihood that the acute

transformation occurred immediately before surgery. On the other

hand, the widespread progression of HLH may have resulted from

several factors during the surgical procedure: The surgical

stimulation could have activated the lymphoma cells to secrete

large amounts of soluble factors, such as TNF-α (30), or the operative procedure may have

dispersed cellular components into the systemic circulation

(31).

The HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria are well-known

(2). However, adult patients may

exhibit symptoms that are difficult to distinguish from sepsis or

MOF of other causes. Delayed diagnosis of LAHS may have fatal

consequences (17,18). Currently, no standardized treatment

strategy exists, and whether an HLH-directed or malignancy-directed

approach should be adopted (32,33)

remains unclear. In the case of the present study, upon his

transfer to a tertiary hospital on POD 5, the patient met 6 of the

8 HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria, leading to the identification of

his condition. Finally, immunosuppressive therapy preceded,

stabilizing the patient's condition and allowing us to commence

chemotherapy. At the time of conclusion of the present study, eight

months postoperatively, the patient has achieved a longer survival

than typical reported cases.

In conclusion, while splenic lymphoma typically

manifests with low-grade lymphoma, it can transform into a

high-grade lymphoma, which can accompany severe complications such

as HLH and MOF. In the present case, splenectomy served not only in

the diagnosis but also in tumor cytoreduction before chemotherapy.

Furthermore, through interdisciplinary collaboration between the

surgical and hematology teams, the patient's condition was

successfully treated by performing a timely splenectomy to reduce

the tumor burden, followed by steroid pulse therapy and

chemotherapy. Of note, surgery and subsequent chemotherapy may be

life-saving in certain cases of LAHS, as this strategy may assist

in avoiding chemotherapy-related fatal complications.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

HM, KO and KK participated in the surgical

procedures. MSh, YI, AU, MSu, TS and KK were involved in clinical

management. HM drafted the manuscript. MSh, YI, AU, MSu, TS, KO and

KK revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All

the authors have read and approved the final manuscript. HM and KK

have independently reviewed and confirm all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of this case report and the

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HLH

|

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

|

|

MOF

|

multiple organ failure

|

|

LAHS

|

lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic

syndrome

|

|

Hb

|

hemoglobin

|

|

Plt

|

platelet count

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

sIL-2R

|

soluble interleukin 2 receptor

|

|

CT

|

computed tomography

|

|

FDG-PET

|

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography

|

|

HE

|

Hematoxylin and Eosin

|

|

POD

|

postoperative day

|

|

AST

|

aspartate aminotransferase

|

|

T-Bil

|

total bilirubin

|

|

D-Bil

|

direct bilirubin

|

|

CRP

|

C-reactive protein

|

|

ICU

|

intensive care unit

|

|

R-EPOCH

|

Rituximab, Etoposide, Prednisone,

Oncovin, Cyclophosphamide and Hydroxydaunorubicin

|

|

SUV

|

standardized uptake value

|

|

mPSL

|

methylprednisolone

|

References

|

1

|

La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, von Bahr

Greenwood T, Machowicz R, Berliner N, Birndt S, Gil-Herrera J,

Girschikofsky M, Jordan MB, et al: Recommendations for the

management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood.

133:2465–2477. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM,

Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski

J and Janka G: HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

48:124–131. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lee JC and Logan AC: Diagnosis and

management of adult malignancy-associated hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis. Cancers (Basel). 15:18392023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pasvolsky O, Zoref-Lorenz A, Abadi U,

Geiger KR, Hayman L, Vaxman I, Raanani P and Leader A:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a harbinger of aggressive

lymphoma: A case series. Int J Hematol. 109:553–562. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Li F, Li P, Zhang R, Yang G, Ji D, Huang

X, Xu Q, Wei Y, Rao J, Huang R and Chen G: Identification of

clinical features of lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome

(LAHS): An analysis of 69 patients with hemophagocytic syndrome

from a single-center in central region of China. Med Oncol.

31:9022014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang H, Xiong L, Tang W, Zhou Y and Li F:

A systematic review of malignancy-associated hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis that needs more attentions. Oncotarget.

8:59977–59985. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fischer AH, Jacobson KA, Rose J and Zeller

R: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of tissue and cell sections. CSH

Protoc. 2008.pdb.prot4986. 2008.

|

|

8

|

Moreau EJ, Langerak AW, van Gastel-Mol EJ,

Wolvers-Tettero IL, Zhan M, Zhou Q, Koop BF and van Dongen JJ: Easy

detection of all T cell receptor gamma (TCRG) gene rearrangements

by Southern blot analysis: Recommendations for optimal results.

Leukemia. 13:1620–1626. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

van Dongen JJ and Wolvers-Tettero IL:

Analysis of immunoglobulin and T cell receptor genes. Part I: Basic

and technical aspects. Clin Chim Acta. 198:1–91. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Southern E: Southern blotting. Nat Protoc.

1:518–525. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim B, Lee ST, Kim HJ and Kim SH: Bone

marrow flow cytometry in staging of patients with B-cell

non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Lab Med. 35:187–193. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Carbone PP, Kaplan HS, Musshoff K,

Smithers DW and Tubiana M: Report of the committee on Hodgkin's

disease staging classification. Cancer Res. 31:1860–1861.

1971.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Schwartz J, Padmanabhan A, Aqui N, Balogun

RA, Connelly-Smith L, Delaney M, Dunbar NM, Witt V, Wu Y and Shaz

BH: Guidelines on the use of therapeutic apheresis in clinical

practice-evidence-based approach from the writing committee of the

American society for apheresis: The seventh special issue. J Clin

Apher. 31:149–162. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li B, Guo J, Li T, Gu J, Zeng C, Xiao M,

Zhang W, Li Q, Zhou J and Zhou X: Clinical characteristics of

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with non-hodgkin

B-Cell lymphoma: A multicenter retrospective study. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma Leuk. 21:e198–e205. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yao S, Jin Z, He L, Zhang R, Liu M, Hua Z,

Wang Z and Wang Y: Clinical features and prognostic risk prediction

of non-hodgkin lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Front

Oncol. 11:7880562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Che Y, Xu L, Zhang X, Qiu X, Song J, Ding

X and Sun X: Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis triggered

by peripheral T-cell lymphoma: An unusual case report. Clin Case

Rep. 10:e65282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Paluszkiewicz P, Martuszewski A, Majcherek

M, Kucharska M, Bogucka-Fedorczuk A, Wróbel T and Czyż A:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis secondary to peripheral T cell

lymphoma with rapid onset and fatal progression in a young patient:

A case report and review of the literature. Am J Case Rep.

22:e9327652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Iizuka H, Mori Y, Iwao N, Koike M and

Noguchi M: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis associated with

Epstein-Barr virus-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, NOS of

bone marrow-liver-spleen type: An autopsy case report. J Clin Exp

Hematop. 61:102–108. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tang S, Zhao C and Chen W: Aggressive

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis: report of one case. Int J Clin Exp Pathol.

13:2392–2396. 2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Patel R, Patel H, Mulvoy W and Kapoor S:

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with secondary hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis presenting as acute liver failure. ACG Case Rep

J. 4:e682017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hu Y, Zhou W, Sun S, Guan Y, Ma J and Xie

Y: 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-based

prediction for splenectomy in patients with suspected splenic

lymphoma. Ann Transl Med. 9:10092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pata G, Bartoli M, Damiani E, Solari S,

Anastasia A, Pagani C and Tucci A: Still a role for surgery as

first-line therapy of splenic marginal zone lymphoma? Results of a

prospective observational study. Int J Surg. 41:143–149. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kennedy ND, Lê GN, Kelly ME, Harding T,

Fadalla K and Winter DC: Surgical management of splenic marginal

zone lymphoma. Ir J Med Sci. 187:343–347. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Archibald WJ, Baran AM, Williams AM,

Salloum RM, Richard Burack W, Evans AG, Syposs CR and Zent CS: The

role of splenectomy in management of splenic B-cell lymphomas. Leuk

Res. 128:1070532023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ma J, Jiang Z, Ding T, Xu H, Song J, Zhang

J, Xie Y and Wang W: Splenectomy as a diagnostic method in

lymphoma-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis of unknown

origin. Blood Cancer J. 7:e5342017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jing-Shi W, Yi-Ni W, Lin W and Zhao W:

Splenectomy as a treatment for adults with relapsed hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis of unknown cause. Ann Hematol. 94:753–760.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fouquet G, Larroche C, Carpentier B,

Terriou L, Urbanski G, Lacout C, Lazaro E, Salmon Gandonnière C,

Perlat A, Lifermann F, et al: Splenectomy for haemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis of unknown origin: risks and benefits in 21

patients. Br J Haematol. 194:638–642. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Howard SC, Jones DP and Pui CH: The tumor

lysis syndrome. N Engl J Med. 364:1844–1854. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Han SM, Teng CL, Hwang GY, Chou G and Tsai

CA: Primary splenic lymphoma associated with hemophagocytic

lymphohistiocytosis complicated with splenic rupture. J Chin Med

Assoc. 71:210–213. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Griffin G, Shenoi S and Hughes GC:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: An update on pathogenesis,

diagnosis, and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol.

34:1015152020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Hunt DJ, Royer AM and Maxwell RA: Post

splenectomy tumor lysis syndrome. Am Surg. 78:E299–E300. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Daver N, McClain K, Allen CE, Parikh SA,

Otrock Z, Rojas-Hernandez C, Blechacz B, Wang S, Minkov M, Jordan

MB, et al: A consensus review on malignancy-associated

hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer.

123:3229–3240. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Song Y, Wang J, Wang Y, Wu L and Wang Z:

Requirement for containing etoposide in the initial treatment of

lymphoma associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cancer Biol

Ther. 22:598–606. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|