Introduction

Bladder cancer is the ninth most common malignancy

worldwide; an estimated 386,300 new cases and 150,200 deaths from

bladder cancer occurred in 2008 worldwide (1,2). The

majority of bladder cancer occurred in males and among them,

non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounted for 75–85% and

the incidence rate was closely correlated to age (1,2).

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common cause of

urination obstacles in elderly men; the incidence is also rising

with the aging population (3). It

is not unusual to encounter the clinical scenario of a male patient

undergoing endoscopic treatment for bladder cancer (TURBT) who also

requires transurethral resection of prostate (TURP). It was unclear

whether it was safe to combine the two procedures since there was a

risk of circulating cancer cells that may implant into the raw

prostatic fossa and thereby enhance the risk of subsequent

recurrences. In 1953 and 1956, simultaneous resection was first

reported by Kiefer (4) and Hinman

(5) based on four and three

patients, respectively. The results indicated that simultaneous

resection was inadvisable due to the high recurrence (100%) in the

vesical neck or prostatic urethra. However, Greene and Yalowitz

(6) in 1972 studied 100 patients

who underwent simultaneous transurethral resection and the authors

observed that simultaneous resection was preferable without

increasing the risk of tumor recurrence. Since then, numerous

studies on this issue have been conducted, however, the results of

these studies were different or even contradictory (7). A previous meta-analysis (8), based on five pooled non-randomized

concurrent controlled trials (NRCCTs) and one randomized controlled

trial (RCT), reported a statistically significant result. NRCCT

suffers more confounding factors and biases than RCT and they are

not suitable for pooling, so the results were unconvincing.

It was unclear whether simultaneous resection of

bladder tumor and prostate were safe and preferable for patients

with NMIBC and BPH. An in depth reassessment of this issue may have

important public health and clinical implications, so we performed

this systematic review and meta-analysis to examine all the

published evidence involving NRCCTs and RCTs, to provide

unambiguous evidence whether simultaneous TURBT/TURP in the

treatment of NMIBC with BPH was feasible.

Materials and methods

Literature search

A systematic search of the Cochrane Central Register

of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), PubMed, EMBASE and the ISI Web of

Knowledge databases for the relevant published studies was

conducted from their establishment to March 21, 2012. The relevant

search terms were (‘prostatic hyperplasia’ OR ‘Benign Prostate

Hyperplasia’ OR ‘prostate’) AND (‘simultaneous’ OR ‘simultaneously’

OR ‘synchronous’ OR ‘coinstantaneous’) AND (‘bladder tumor’ OR

‘bladder tumour’ OR ‘bladder cancer’ OR ‘bladder neoplasm’ OR

‘bladder carcinoma’ OR ‘vesical neoplasma’) AND (‘recurrence’ OR

‘relapse’). References were explored to identify relevant

manuscripts. Only studies published in English were included.

Study selection

A study was included in this systematic review when

the following criteria were met: i) type of research: published RCT

or NRCCTs; ii) participants: patients with NMIBC (including Ta, T1)

combining benign prostatic hyperplasia (regardless of the severity,

but excluding prostate cancer), and including information about

patient age, length of follow-up and tumor stage; iii)

interventions: simultaneous group (TURBT+TURP, resection of bladder

tumor first, then prostate resection); control group (TURBT only),

regardless of whether adjuvant chemotherapy was administered; iv)

outcomes: overall tumor recurrence rates, recurrence rate at the

prostatic urethra and/or bladder neck, and tumor progression and v)

it was possible to obtain full texts.

Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality of each RCT was assessed

using the Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias

(9), which utilizes seven aspects:

i) details of randomization method, ii) allocation concealment,

iii) blinding of participants and personnel, iv) blinding of

outcome assessment, v) incomplete outcome data, vi) selective

outcome reporting and vii) other sources of bias, to provide a

qualification of risk of bias.

For NRCCTs, we used MINORS (Methodological Index for

Non-Randomized Studies) guidelines (10) to assess the methodological quality.

MINORS guidelines consisted of 12 indexes: i) a clearly stated aim,

ii) inclusion of consecutive patients, iii) prospective collection

of data, iv) endpoints appropriate to the aim of the study, v)

unbiased assessment of the study endpoint, vi) follow-up period

appropriate to the aim of the study, vii) loss to follow-up less

than 5%, viii) prospective calculation of the study size, ix)

adequate control group, x) contemporary groups (control and studied

group should be managed during the same time period, no historical

comparison), xi) baseline equivalence of groups and xii) adequate

statistical analyses, every item has two scores and the total score

is 24; when the score is ≥16 points this indicates high quality,

otherwise the quality is low (<16 points).

Data extraction

Two researchers read the full texts independently

and extracted the contents as follows: the sample inclusion

criteria and sample size, methods and processes of sampling and

grouping, basic information, interventions, outcome, length of

follow-up, loss rates and reasons for the loss, and statistical

methods of the studies. To obtain the missing information, authors

were contacted by phone or e-mail. In studies involving RCT with

multiple groups or non-randomized clinical trials, only the

experimental and control groups associated with this study were

extracted.

Level of evidence

We evaluated the level of evidence by using the

GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and

Evaluation) approach (11). In

addition, the GRADEprofiler 3.6 software (12) was used to create the evidence

profile.

The GRADE system included: level of evidence: i)

high quality (or A); further research is extremely unlikely to

change our confidence in the estimate of effect, ii) moderate

quality (or B); further research is likely to have an important

impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change

the estimate, iii) low quality (or C); further research is

extremely likely to have an important impact on our confidence in

the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate and iv)

very low quality (or D); we are extremely uncertain about the

estimate.

Statistical analysis

We proposed to pool results from single studies by

meta-analysis where this was identified to be both clinically and

statistically appropriate. We computed pooled ORs and 95% CIs using

the Cochrane Review Manager 5.1 software (version 5.1.6) to

generate forest plots and to assess the heterogeneity of the

included studies. Heterogeneity was quantified by using the

I2 statistic; low, moderate and high represented

I2 values of 40, 70 and 100%, respectively. Where

I2≤40% indicates there was no evidence of heterogeneity,

the fixed-effects model was used, otherwise the random-effects

model was used. In the presence of heterogeneity, we performed

sensitivity analyses to explore possible explanations for

heterogeneity and to examine the influence of various exclusion

criteria on the overall risk estimate. We also investigated the

influence of a single study on the overall risk estimate by

removing each study in each turn, to test the robustness of the

main results. Subgroup analysis was also conducted if significant

heterogeneity was identified, according to methodological quality

(low-quality studies vs. high-quality studies). Where possible,

potential publication bias was assessed by visual inspection of the

funnel plots of the primary outcome.

Results

Search results

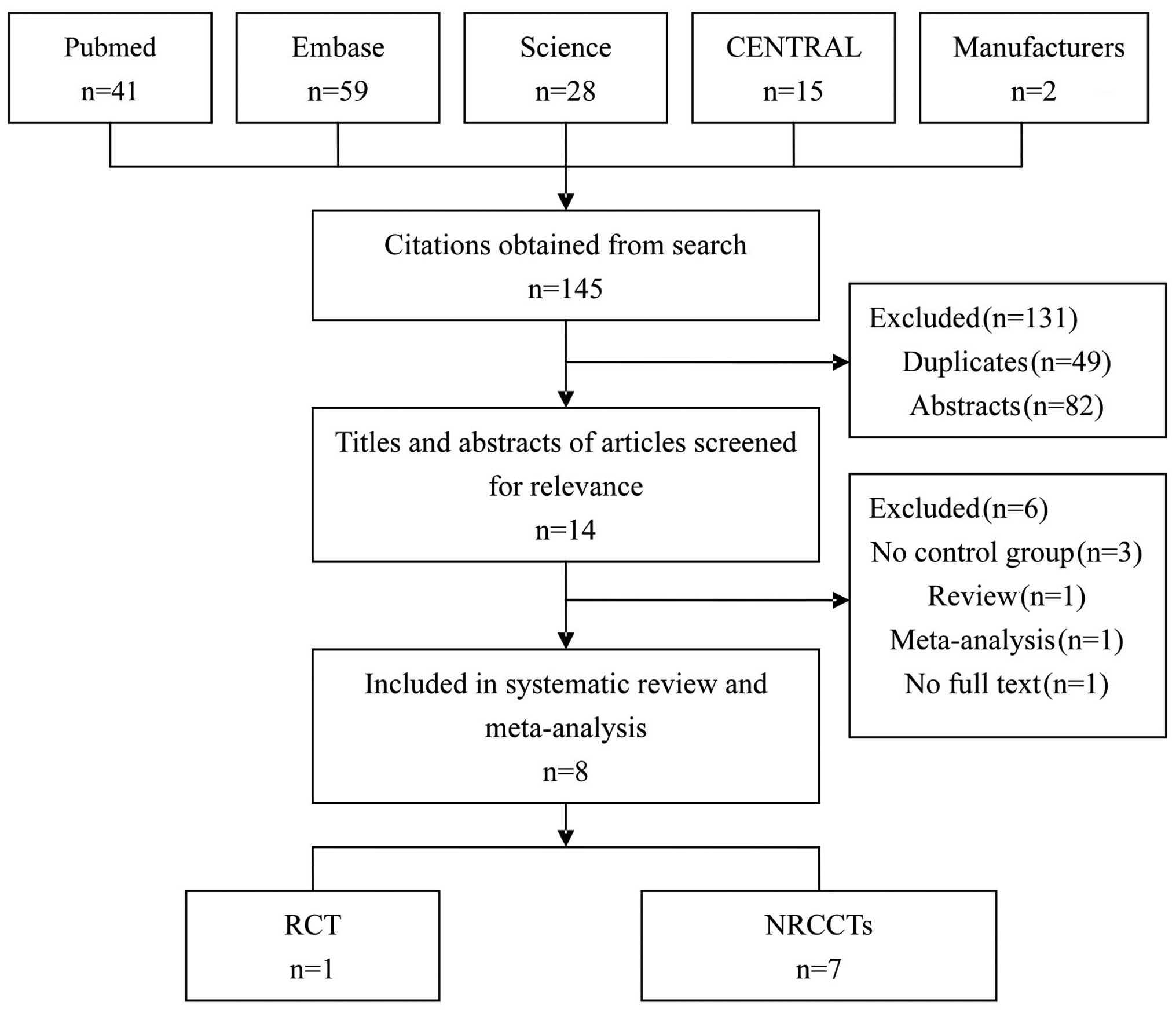

The initial search obtained 145 articles. After

reading the abstracts and the full texts, 8 were selected for this

study, including 1 RCT (13) and 7

NRCCTs (6,14–19).

Fig. 1 shows the process of

selection.

Characteristics and quality of included

studies

Table I shows the

characteristics and quality points of each included study. Of the 8

studies, 3 were performed in the USA (6,14,15),

2 in Korea (17,18) and the remaining (13,16,19)

in India, Turkey and Tunisia, respectively, during the period

between 1972 and 2010, the total number of patients in each study

ranged from 48 to 287. The baselines of 7 NRCCTs were similar and

individual results are shown in Tables

II and III. According to

MINORS evaluation criteria (10),

one study scored 22 points, 2 studies scored 20 points and 4

studies scored 19 points (Table

I). The quality of RCTs according to the Cochrane Collaboration

guidelines, provided a qualification of risk of bias. It refered to

randomization only, lacking information with regard to allocation

concealment and blind measurement; but no incomplete outcome data,

no selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias, therefore

there was a moderate risk of bias.

| Table ICharacteristics of each primary

study. |

Table I

Characteristics of each primary

study.

| Study (ref.) | Year | Country of

origin | Study type | Patients (n)

| Mean age | Mean follow-up

(months) | Outcome | Quality (points) |

|---|

| Simultaneous

group | Control group |

|---|

| Greene and Yalowitz

(6) | 1972 | USA | NRCCT | 100 | 100 | NA | 132/132 | 1, 2,

4 | High (19) |

| Laor et

al(14) | 1981 | USA | NRCCT | 137 | 150 | 71/60 | 69/96 | 1, 2,

4 | High (19) |

| Vicente et

al(15) | 1988 | USA | NRCCT | 100 | 100 | 69/60 | 47/46 | 1, 2 | High (20) |

| Ugurlu et

al(16) | 2007 | Turkey | NRCCT | 31 | 34 | 55.97/68.22 | 30.6/27.4 | 1, 2,

3 | High (19) |

| Kim et

al(17) | 2009 | Korea | NRCCT | 24 | 165 | 70/64.1 | 52.2/43.8 | 1, 2,

3 | High (19) |

| Ham et

al(18) | 2009 | Korea | NRCCT | 106 | 107 | 66.7/65.5 | 50.1/54.3 | 1, 2,

3, 4, 5 | High (22) |

| Jaidane et

al(19) | 2010 | Tunisia | NRCCT | 85 | 85 | 71/71 | 35.2/33.1 | 1, 2,

3 | High (20) |

| Singh et

al(13) | 2009 | India | RCT | 24 | 24 | 56.06/57.36 | 35.7/37.6 | 1, 2,

3 | Moderate |

| Table IICharacteristics of the simultaneous

groups. |

Table II

Characteristics of the simultaneous

groups.

| Study | Year | Patients (n) | Total recurrence n

(%) | Recurrence in

bladder neck and/or prostatic fossa, n (%) | Progression

(%) | Single/multiple

(n) | Ta/T1 (n) | Grade (n) | Adjuvant

chemotherapy |

|---|

| Greene and Yalowitz

(6) | 1972 | 100 | 54 (54) | 17 (17) | NA | 81/19 | NA | 57/29/14a | NA |

| Laor et

al(14) | 1981 | 137 | 77 (56.2) | 21 (15) | NA | 112/25 | NA | 34/35/51a | NA |

| Vicente et

al (15) | 1988 | 100 | 55 (55) | 10 (10) | NA | 58/42 | 21/79 | 4/78/18a | NA |

| Ugurlu et al

(16) | 2007 | 31 | 11 (35.5) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (9.7) | 31/0 | 25/6 | 26/3/2a | N |

| Kim et al

(17) | 2009 | 24 | 9 (37.5) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (8.3) | NA | 8/16 | 13/11b | NA |

| Ham et al

(18) | 2009 | 106 | 31 (29.2) | 0 | 10 (9.4) | 58/48 | 21/85 | 60/46b | Y |

| Jaidane et

al (19) | 2010 | 85 | 17 (20) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 70/15 | 9/76 | 32/45/8a | Y |

| Singh et al

(13) | 2009 | 24 | 12 (50) | 4 (16.2) | 3 (12.5) | 24/0 | 17/7 | 10/11/3a | N |

| Table IIICharacteristics of the control

groups. |

Table III

Characteristics of the control

groups.

| Study | Year | Patients (n) | Total recurrence n

(%) | Recurrence in

bladder neck and/or prostatic fossa, n (%) | Progression

(%) | Single/multiple

(n) | Ta/T1(n) | Grade (n) | Adjuvant

chemotherapy |

|---|

| Greene and Yalowitz

(6) | 1972 | 100 | 54 (54) | 16 (16) | NA | 77/23 | NA | 59/23/18a | NA |

| Laor et

al(14) | 1981 | 150 | 92 (61.3) | 27 (18) | NA | 124/26 | NA | 35/7/57a | NA |

| Vicente et

al(15) | 1988 | 100 | 73 (73) | 10 (10) | NA | 52/48 | 24/76 | 18/73/9a | NA |

| Ugurlu et

al(16) | 2007 | 34 | 14 (41.2) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (8.8) | 34/0 | 25/9 | 31/3/0a | N |

| Kim et

al(17) | 2009 | 165 | 37 (22.4) | 3 (1.8) | 10 (6.1) | NA | 43/109 | 81/84b | NA |

| Ham et

al(18) | 2009 | 107 | 46 (43.0) | 0 | 12 (11.2) | 56/51 | 19/88 | 59/48b | Y |

| Jaidane et

al(19) | 2010 | 85 | 20 (23.5) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.3) | 65/20 | 11/74 | 33/44/8a | Y |

| Singh et al

(13) | 2009 | 24 | 11 (42.8) | 3 (12.5) | 2 (8.3) | 24/0 | 18/6 | 9/11/4a | N |

Overall tumor recurrence rates

Meta-analysis of 7 NRCCTs (6,14–19)

by a fixed-effects model (P=0.12; I2, 40%) revealed that

simultanuous resection did not increase the recurrence rate of

bladder tumor, on the contrary, recurrence rate was statistically

lower than that in the control group (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.60–0.96;

P=0.02; Fig. 2).

The overall recurrence rate in simultanuous and

control groups was 50 and 42.8%, respectively, (P>0.05) in the

study by Singh et al (13).

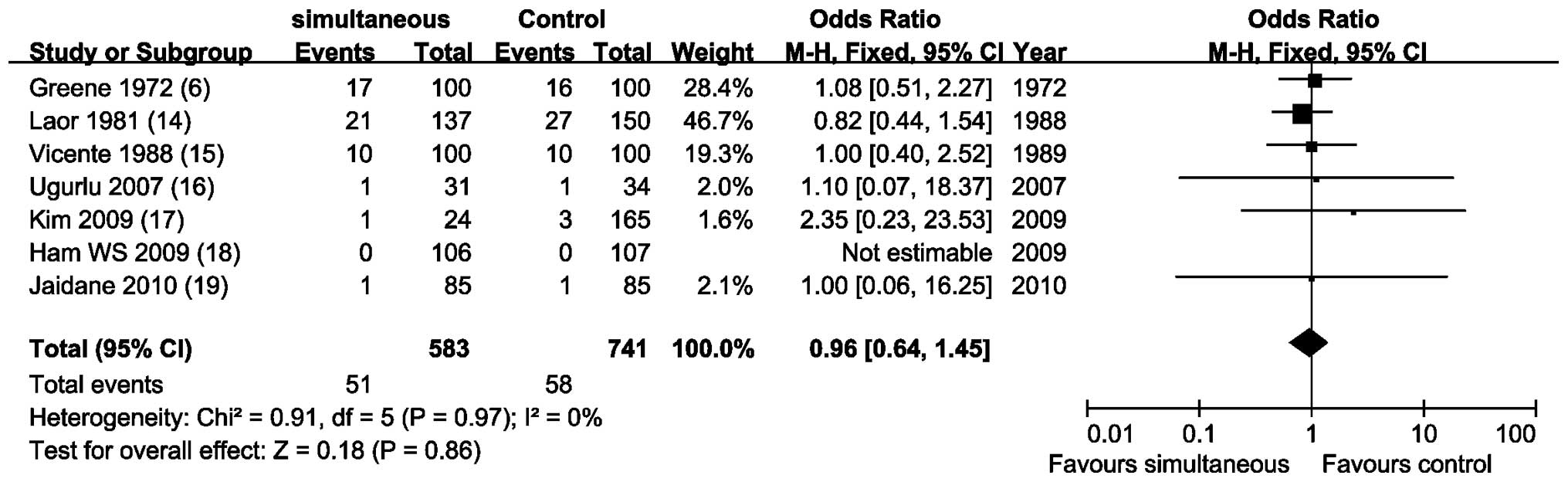

Recurrence rate at the prostatic urethra

and/or bladder neck

Meta-analysis of 7 NRCCTs (6,14–19)

by a fixed-effects model (P=0.97; I2, 0%) showed that

there was no statistical difference to compare recurrence rate to

the prostatic urethra and/or bladder neck (OR, 0.96; 95% CI,

0.64–1.45; P=0.86; Fig. 3).

The recurrence rate at the prostatic urethra and/or

bladder neck was 16.2 and 12.5%, respectively, (P>0.05) in the

study by Sing et al (13).

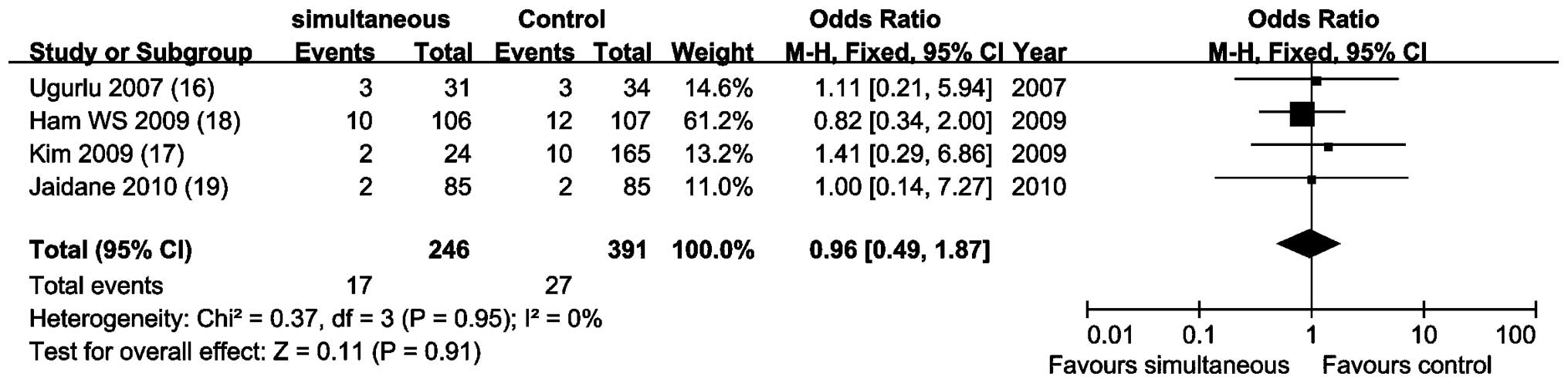

Tumor progression rates

Meta-analysis of 4 NRCCTs (16–19)

by a fixed-effects model (P=0.95; I2, 0%) showed that

the tumor progression rates were similar and there was no

statistical difference (OR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.49–1.87; P=0.91;

Fig. 4).

The tumor progression rate was 12.5 and 8.3%,

respectively, (P=0.05) in the study by Singh et al (13).

GRADE profile evidence

The included NRCCTs had the same three outcome

indicators, they were the overall tumor recurrence rates,

recurrence rate at bladder neck/prostatic fossa and tumor

progression. The GRADE system evidence for each outcome level and

reasons for upgrade and downgrade are shown in Table IV. Table IV also shows the GRADE quality of

evidence for the included RCT.

| Table IVGRADE profile evidence of the

included studies. |

Table IV

GRADE profile evidence of the

included studies.

Quality assessment

| No. of patients

| Effect

| | |

|---|

| No. of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other

considerations | Simultaneous | Control | Relative (95%

CI) | Absolute | Quality | Importance |

|---|

| Recurrence |

| 7 | NRCCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | Strong

associationb | 254/583

(43.6%) | 336/741

(45.3%) | OR 0.76

(0.6–0.96) | 67 fewer/1000 (from

10 fewer to 121 fewer) | ⊕⊕○○

Low | Critical |

| 1 | RCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | None | 12/24 (50%) | 11/24 (45.8%) | RR 1.09

(0.6–1.97) | 41 more/1000 (from

183 fewer to 445 more) | ⊕⊕⊕○

Moderate | Critical |

| Recurrence rate at

the prostatic urethra and/or bladder neck |

| 7 | NRCCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | Strong

associationb,

increased effect for RR ∼1c | 51/583 (8.7%) | 58/741 (7.8%) | OR 0.96

(0.64–1.45) | 3 fewer/1000 (from

27 fewer to 31 more) | ⊕⊕⊕○

Moderate | Critical |

| 1 | RCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | None | 4/24 (16.7%) | 3/24 (12.5%) | RR 1.33

(0.33–5.33) | 41 more/1000 (from

84 fewer to 541 more) | ⊕⊕⊕○

Moderate | Critical |

| Progression |

| 4 | NRCCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | Strong

associationb

increased effect for RR ∼1c | 17/246 (6.9%) | 27/391 (6.9%) | OR 0.96

(0.49–1.87) | 3 fewer/1000 (from

34 fewer to 53 more) | ⊕⊕⊕○

Moderate | Important |

| 1 | RCT | Seriousa | No serious

inconsistency | No serious

indirectness | No serious

imprecision | None | 3/24 (12.5%) | 2/24 (8.3%) | RR 1.5

(0.27–8.19) | 42 more/1000 (from

61 fewer to 599 more) | ⊕⊕⊕○

Moderate | Important |

Discussion

Previous data have demonstrated that benign

prostatic hyperplasia and other lower urinary tract obstructions

were important factors in the pathogenesis of bladder cancer

(20,21). In patients with benign prostatic

hyperplasia, the retention of urine prolonged the duration of

chemical carcinogens in bladder, and increasing the incidence of

bladder cancer. Melicow et al (22) suggested that 4-aminobiphenyl and

benzidine were decomposed into carcinogens, since the activity of

urinary β-glucuronidase increased in patients with prostatic

hyperplasia. This would cause bladder cancer. Due to the lower

urinary tract obstruction, the bladder is susceptible to become

infected, form stones and diverticulitis. Long-term and chronic

irritation would cause the formation of epithelial hyperplasia and

cystic or glandular cystitis. Part of the epithelium extended to

the submucosal connective tissue formed von Brunn nests, this may

become adenocarcinoma. As reported previously, these complications

also stimulate transitional metaplasia and lead to squamous cell

carcinoma. Therefore, early surgery over the same period to remove

the lower urinary tract obstruction, not only does not increase the

overall recurrence rate of bladder cancer, but also has the

potential to reduce the recurrence rate (6,23).

In the past, patients with NMIBC and BPH were often

treated with open or staging surgery. However, open surgery has

certain shortcomings, including serious trauma, more postoperative

complications and a longer time to recovery, particulary unbearable

for elderly patients. Staging surgery would increase the risk of

surgery and wasted money. With the development and popularity of

urological endoscopic technology, numerous scholars now suggest

simultanuous resection. However, in theory, simultanuous resection

may increase the risk that cancer cells implant into the bladder

neck and prostatic fossa. It was controversial whether simultanuous

resection was feasible, although there were numerous associated

studies.

There was a relevant meta-analysis published by Luo

et al (8) in 2011,

involving 6 studies and 983 patients. There was evidence that

simultaneous TURBT/TURP did not increase the overall recurrence

rate or recurrence rate in bladder neck/prostatic fossa. The

shortcomings in this meta-analysis were as follows: i) incomplete

retrieval or intended selective inclusion, so the efficiency of

retrieval was low and would cause serious publication bias; ii)

performed meta-analysis misused RR to pool the NRCCTs, which is the

statistical index for prospective design (e.g. RCT); iii) failure

to provide the risk bias figure, and failure to provide complete

risk bias evaluation; iv) the methodological quality assessment

tool for RCT was misused to assess the quality of NRCCTs, and

failed to provide complete risk bias evaluation. In addition, the

author also indicated in this paper that the size of inclusive and

total samples were small. The results still require proof that

includes larger sample size controlled clinical trials in the

future, in order to obtain more accurate conclusions.

This study overcame the shortcomings of the previous

study, based on a comprehensive literature search, evaluated RCT

and NRCCTs using appropriate criteria, meta-analysis of NRCCTs,

qualitative analysis of RCT, and the use of GRADE quality of

evidence given in the standard classification. The results showed:

simultaneous resection did not increase recurrence rate, on the

contrary, the overall recurrence rate was lower than that of

control group, it also did not increase the risk of tumor

metastasis or tumor progression rate.

We also assessed the level of evidence using the

GRADE approach. According to the GRADE approach, the quality of the

evidence was only intermediate (the first two or three outcome

indicators) and low (first outcome indicators) due to the limited

evidence derived from combined NRCCT, and other reasons as follows:

i) lack of allocation concealment and blinding and ii) the study

controlled important confounding factors, but did not control

others. RCTs were generally high quality, but this included one RCT

with significant limitations of the study. Therefore, the quality

of evidence was moderate in this RCT.

However, there were the following limitations in

this meta-analysis. Firstly, we included only one RCT, so high

quality meta-analysis of RCT could not be performed. Secondly, for

non-randomized trials, the possibility of other bias reflected in

the tumor status (single/multiple, tumor grade, associated with

carcinoma in situ, etc.), postoperative bladder perfusion,

technical surgical differences and transurethral tumor samples for

inspection and other aspects of quality problems. Thirdly, the lack

of long-term assessment of key indicators, such as the 5- or

10-year survival rate of patients. Lastly, the study sample size

and overall sample size were small.

In summary, current evidence suggests that: for

patients with NMIBC and BPH, simultanuous resection relief of the

lower urinary tract obstruction, did not increase the overall

recurrence rate of bladder tumors, but also did not cause

metastasis and tumor progression, reduced expenses and shortened

hospital stay and may reduce the relapse rate and improve the

quality of life of patients. Based on the GRADE system, the quality

of evidence, the recommended level was 2B. Due to the lack of

evaluation of the system, further studies are required to be

designed strictly according to CONSORT criteria (24), to design larger sample,

high-quality, multi-center RCT, and include long-term key outcome

indicators (such as 5- or 10-year survival rate of patients), in

order to further evaluate the efficacy and safety of simultanuous

resection.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the

Foundation of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (Wuhan China;

no. 115004) for Xing-Huan Wang and the Intramural Research Program

of the Hubei University of Medcine (Shiyan China; no. 2011 CZX01)

for Xian-Tao Zeng.

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Babjuk M, Oosterlinck W, Sylvester R, et

al: EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of

the bladder, the 2011 update. Eur Urol. 59:997–1008. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Rowhrborm CG and McConnell JD: Etiology,

pathophysiology, epidemiology and natural history of benign

prostatic hyperplasia. Campbell's Urology. Walsh PC, Retik AB,

Vaughan ED Jr and Wein AJ: W. B. Saunders Company. (Philadelphia,

PA). 1297–1330. 2002.

|

|

4

|

Kiefer JH: Bladder tumor recurrence in the

urethra: a warning. J Urol. 69:652–656. 1953.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hinman F Jr: Recurrence of bladder tumors

by surgical implantation. J Urol. 75:695–696. 1956.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Greene LF and Yalowitz PA: The

advisability of concomitant transurethral excision of vesical

neoplasm and prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 107:445–447.

1972.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kouriefs C, Loizides S and Mufti G:

Simultaneous transurethral resection of bladder tumour and

prostate: is it safe? Urol Int. 81:125–128. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Luo SJ, Lin YJ and Zhang WL: Does

simultaneous transurethral resection of bladder tumor and prostate

affect the recurrence of bladder tumor? A meta-analysis. J

Endourol. 25:291–296. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Higgins JPT and Green S: Cochrane Handbook

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated

Macch 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011.Available at

https://www.cochrane-handbook.org.

|

|

10

|

Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski

F, Panis Y and Chipponi J: Methodological index for non-randomized

studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument.

ANZ J Surg. 73:712–716. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al:

GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and

strength of recommendations. BMJ. 336:924–926. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

GRADEpro. [Computer program]. Version 3.6

for Windows. Brozek J, Oxman A, Schünemann H, 2011.

|

|

13

|

Singh W, Sinha RJ and Sankhwar SNS:

Outcome of simultaneous transurethral resection of bladder tumor

and transurethral resection of the prostate in comparison with the

procedures in two separate sittings in patients with bladder tumor

and urodynamically proven bladder outflow obstruction. J Endourol.

23:2007–2011. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Laor E, Grabstald H and Whitmore WF: The

influence of simultaneous resection of bladder tumors and prostate

on the occurrence of prostatic urethral tumors. J Urol.

126:171–175. 1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Vicente J, Chéchile G, Pons R and Méndez

G: Tumor recurrence in prostatic urethra following simultaneous

resection of bladder tumor and prostate. Eur Urol. 15:40–42.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ugurlu O, Gonulalan U, Adsan O, Kosan M,

Oztekin V and Cetinkaya M: Effects of simultaneous transurethral

resection of prostate and solitary bladder tumors smaller than 3 cm

on oncologic results. Urology. 70:55–59. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kim S, Park S and Ahn H: Oncologic results

of simultaneous transurethral resection of superficial bladder

cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 74:S1442009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ham WS, Kim WT, Jeon HJ, Lee DH and Choi

YD: Long-term outcome of simultaneous transurethral resection of

bladder tumor and prostate in patients with nonmuscle invasive

bladder tumor and bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol.

181:1594–1599. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jaidane M, Bouicha T, Slama A, et al:

Tumor recurrence in prostatic urethra following simultaneous

resection of bladder tumor and prostate: a comparative

retrospective study. Urology. 75:1392–1395. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Mommsen S and Sell A: Prostatic

hypertrophy and venereal disease as possible risk factors in the

development of bladder cancer. Urol Res. 11:49–52. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fellows GJ: The association between

vesical carcinoma and urinary obstruction. Eur Urol. 4:187–188.

1978.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Melicow MM, Uson AC and Lipton R:

beta-Glucuronidase activity in the urine of patients with bladder

cancer and other conditions. J Urol. 86:89–94. 1961.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Karaguzhin SG, Merinov DS and Martov AG:

One-stage transurethral resection of the urinary bladder and the

prostate in patients with superficial cancer of the urinary bladder

combined with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urologiia. 17–21.

2005.(In Russian).

|

|

24

|

Schulz KF, Moher D and Altman DG: CONSORT

2010 comments. Lancet. 376:1222–1223. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|