Introduction

An aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC) is a rare skeletal

tumor that accounts for ~1% of all bone tumors. A spinal location

for an ABC is extremely rare. Fibrohistiocytoma is a type of

primary benign bone tumor, which is composed of fusiform

fibroblasts (1,2). It is a rare bone tumor, whose

predilection site is the pelvis. They are more common in male

patients. The combination of two primary bone benign tumors is

quite rare in the clinic. From a diagnostic standpoint,

fibrohistiocytoma and ABCs are widely confused with other

giant-cell-containing tumors of the bone. Among such tumors,

telangiectatic osteosarcoma is widely confused with ABCs,

radiologically and pathologically, and there have been reports of

telangiectatic osteosarcoma that were initially treated as ABCs

with a fatal outcome (3).

Therefore, the differential diagnosis between the two diseases

should be conducted even more cautiously to prevent

misdiagnosis.

Case report

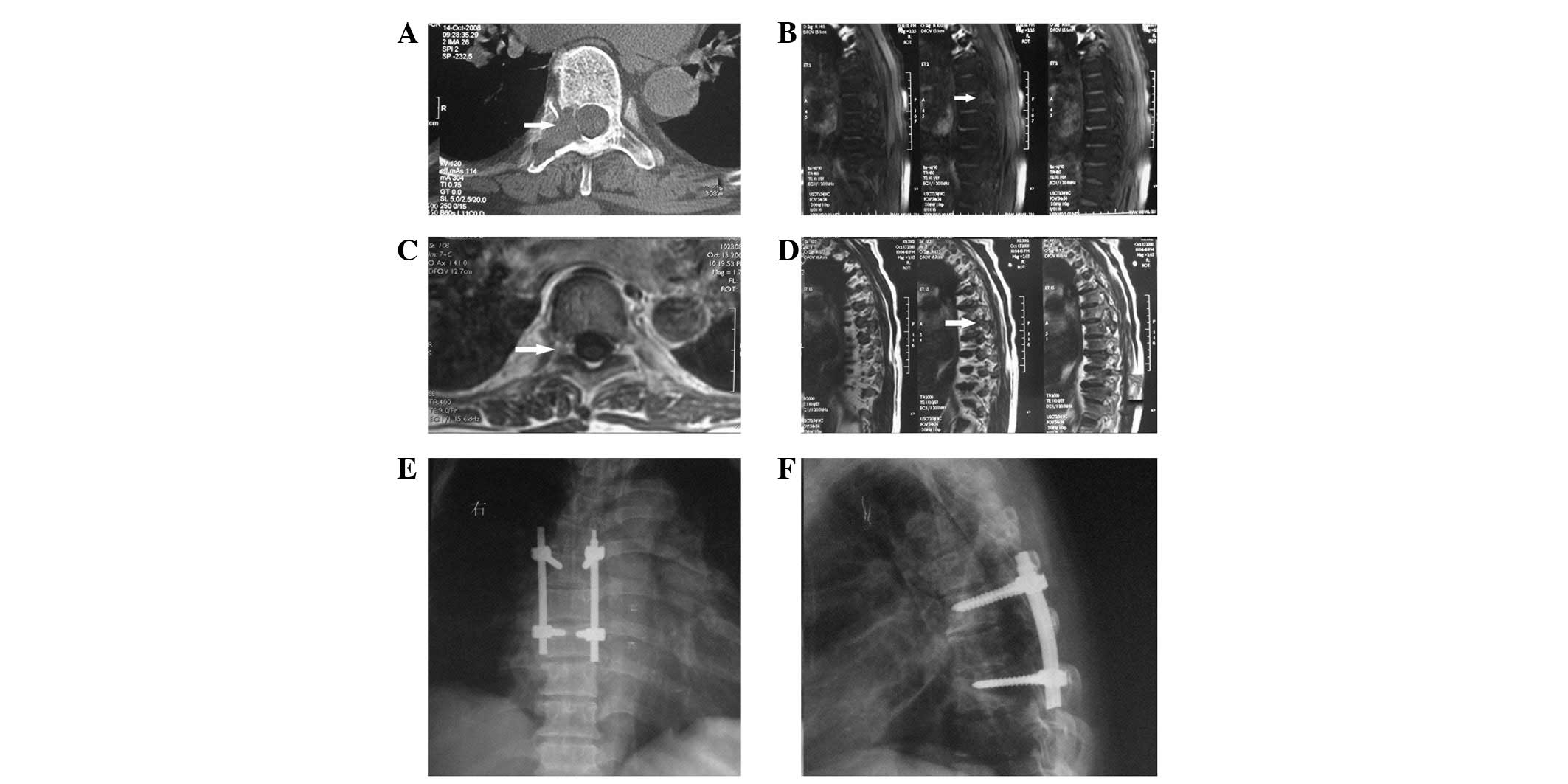

A 63-year-old female complained of back pain, and

numbness and weakness in the lower limbs. Computerized tomography

(CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1A–D) revealed an expansive, lytic

and unicameral cyst lesion localized at the pedicle and transverse

process of T7. A nuclide bone scan revealed multiple nuclide

aggregation in the costal bone and body of the vertebra. It was

considered that the patient suffered from a metastatic tumor.

However, after a thorough general examination, no sign of a primary

tumor was identified. Then, the patient underwent a positron

emission tomography (PET)-CT scan. Expansive osteoclasia was

observed in the right appendix of T7, similar to a giant cell tumor

of bone. Since the patient had rheumatic heart disease for ~10

years, heart ultrasound (heart shadow enlargement with back flow)

was performed to evaluate heart function (grade II), to ensure the

patient was able to endure surgery. Based on the clinical and

diagnostic imaging findings, plans were made to treat the lesion

with resection. Informed consent was obtained from the patient

regularly. Prior to surgery, a puncture biopsy was performed, which

resulted in the formation of scar tissue. Surgery was subsequently

performed with the use of a general anesthetic, with the patient in

the prone position. The tumor was resected and electrocautery was

used following resection to prevent recurrence. Following

excisional biopsy, segmental instrumented posterior fusion was

performed from T6 to T8 (Fig. 1E and

F). The surgery lasted for ~2.5 h. The blood loss was ~600 ml

and 2 U red blood cells were transfused intraoperatively to

maintain the normal blood volume. The pathological diagnosis was

fibrohistiocytoma combined with an ABC (Figs. 2 and 3). Immunohistochemical analysis was

negative for cytokeratin (CK), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA),

CD34, CD31, desmin (Des), smooth muscle actin (SMA), HMB45,

phosphoglucomutase 1 (PGM1) and S-100. The patient was followed-up

for >2 years. The bone grafts had been incorporated and the

patient was fully rehabilitated and free of any symptoms. Finally,

the patient succumbed 5 years after surgery from epilepsy.

Discussion

ABCs are benign, highly vascular osseous lesions

characterized by cystic, blood-filled spaces surrounded by thin

perimeters of expanded bone. The precise pathogenesis of ABC is

unclear, although theories such as post-traumatic boney alteration,

reactive vascular malformation and genetic predisposition have been

described. The most widely accepted pathogenic mechanism for the

development of ABC involves a hypothetical local circulatory

disturbance that leads to markedly increased venous pressure and

the development of dilated and enlarged vascular elements within

the affected bone (3).

Fibrohistiocytoma is a type of primary benign bone

tumor, which is composed of fusiform fibroblasts accompanied by

multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells, cystose cells and

chronic inflammatory cell infiltration. There is also likely to be

interstitial substance hemorrhage and hemosiderin deposition. It is

a rare bone tumor and the predilection site is the pelvis. It is

more common in male patients (4).

A combined lesion of two primary benign bone tumors

is quite rare in the clinic (3).

From a diagnostic standpoint, both fibrohistiocytoma and ABC are

widely confused with other giant-cell-containing tumors of bone

(3). Giant cell tumor (GCT), for

instance, is composed of mononuclear cells and osteoclast-like

multinucleated giant cells, with the potential to be locally

aggressive. Histologically, a GCT consists of homogeneous stroma

with giant and mononuclear cells dispersed evenly throughout the

tumor. Giant cell reparative granuloma (GCRG) is an uncommon,

benign, intraosseous reactive lesion for which the roentgenographic

and histological features may overlap with ABCs. Brown tumors or

von Recklinghausen’s disease typically involve the diaphysis of

long bones. The incidence of brown tumors is reported to be

1.5–1.7% of patients with chronic renal deficiency. The

radiographic and histological features of brown tumors, ABCs and

GCRG are often indistinguishable (3). However, brown tumors were recently

reported to have a much more oblated architectural growth pattern

in comparison with ABC and GCRG. Hyperparathyroidism may be ruled

out on the basis of serum calcium, phosphorus and parathyroid

hormone levels.

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma is primarily composed of

multiple dilated multi-cameral capsular cavities that contain

blood, with viable high-grade sarcomatous cells in the peripheral

rim and septae around these spaces. Hence, the lesion is widely

confused with ABCs, radiologically and pathologically, and there

have been reports of telangiectatic osteosarcomas that were

initially treated as ABCs with a fatal outcome. Radiographic

distinction between these lesions is challenging (3). However, the nodular viable high-grade

sarcomatous cells that produce osteoid around these cystic spaces

are demarcated following the administration of contrast material.

The lesion appears as a solid, thick, nodular-enhancing rim of

tissue that contains subtle mineralization when viewed with

radiographs or CT images.

Grossly, an ABC is multiloculated, consisting of

multiple blood-filled cystic spaces separated by thin, tan-white

areas that may represent a solid portion of the ABC or a primary

lesion, if present. Histologically, an ABC is composed of

blood-filled cystic spaces separated by fibrous septae.

Methods for the treatment of an ABC include

resection, curettage, embolization and intralesional injection of a

variety of agents. In the current study, we present a female

patient with thoracic spinal pain, with progressive paresthesias

and muscle weakness of the lower extremities. This case highlights

the importance of considering an ABC in the differential diagnosis

of primary spinal tumors. The differential diagnosis for this

lesion may be challenging, particularly with regard to the

possibility of the presence of osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, ABC,

osteochondroma, neurofibroma, eosinophilic granuloma, hemangioma

and other giant-cell-containing tumors of bone, including GCT,

GCRG, brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism and telangiectatic

osteosarcoma. The evaluation of spinal tumors includes a thorough

history assessment, physical examination, imaging and,

occasionally, laboratory evaluation and biopsy when indicated

(1).

Depending on the analysis of radiographic

morphology, location and the age of the patient with ABC and GCT

(5), the following criteria

suggest an ABC with a high positive predictive value: location in

the diaphysis and shaft, patient aged <17 years and growth rate

grade Lodwick-IA. GCT was selected via the following criteria:

epimetaphyseal location and growth rate grade Lodwick-II. However,

in certain cases, differential diagnosis between the two entities

is radiologically impossible.

In patients who develop a bone tumor of the

posterior elements of the spine, careful clinical and radiological

evaluation is necessary to narrow the differential diagnosis.

Treatment options for ABCs are simple curettage with or without

bone grafting, complete excision, embolization, radiation therapy

or a combination of these modalities. Embolization appears to be

the first option for spinal ABC treatment due to having the best

cost-to-benefit ratio. An intact ABC is indicated when no

pathological fracture or neurological involvements are observed

(2). New therapies have recently

been reported. Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody that

inhibits osteoclast function by blocking the cytokine receptor

activator of the nuclear factor-κB ligand. Satisfactory results

with denosumab in treating GCTs and immunohistochemical

similarities suggest that it may also have positive effects on ABCs

(6). Nevertheless, radical

surgical excision should be the goal of surgery to reduce the

recurrence rate. The recurrence rate is significantly lower in

cases of total excision (7). In

the majority of cases, a complete excision should be performed if

possible. The risk of postlaminectomy kyphosis is high. As such, a

fusion should be considered whenever a laminectomy is performed

(8,9). Prompt detection and treatment with

curettage, decompression and fusion produces a satisfactory result

and prevents spinal cord injury (10). ABCs are hypervascularized lesions.

Pre-operative selective arterial embolization of the lesion may

have some value (11). Selective

arterial embolization should be used as a preoperative adjunct to

surgery for ABC of the spine to reduce intraoperative blood loss

and the need for blood transfusions. Spinal fusion with titanium

instruments (12) is strongly

recommended if more than two facets (more than one on each side, or

more than two full facets) are violated during the excision of the

ABC.

References

|

1.

|

Thakur NA, Daniels AH, Schiller J, Valdes

MA, Czerwein JK, Schiller A, Esmende S and Terek RM: Benign tumors

of the spine. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 20:715–724. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Amendola L, Simonetti L, Simoes CE,

Bandiera S, De Iure F and Boriani S: Aneurysmal bone cyst of the

mobile spine: the therapeutic role of embolization. Eur Spine J.

22:533–541. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Iltar S, Alemdaroğlu KB, Karalezli N,

Irgit K, Caydere M and Aydoğan NH: A case of an aneurysmal bone

cyst of a metatarsal: review of the differential diagnosis and

treatment options. J Foot Ankle Surg. 48:74–79. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Macdonald D, Fornasier V and Holtby R:

Benign fibrohistiocytoma (xanthomatous variant) of the acromion. A

case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

126:599–601. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Rosales-Olivares LM, Baena-Ocampo Ldel C,

Miramontes-Martínez VP, Alpízar-Aguirre A and Reyes-Sánchez:

Aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine. Case report. Cir Cir.

74:377–380. 2006.(In Spanish).

|

|

6.

|

Lange T, Stehling C, Fröhlich B,

Klingenhöfer M, et al: Denosumab: a potential new and innovative

treatment option for aneurysmal bone cysts. Eur Spine J.

22:1417–1422. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Zileli M, Isik HS, Ogut FE, Is M, Cagli S

and Calli C: Aneurysmal bone cysts of the spine. Eur Spine J.

22:593–601. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Gurjar HK, Sarkari A and Chandra PS:

Surgical management of giant multilevel aneurysmal bone cyst of

cervical spine in a 10-year-old boy: case report with review of

literature. Evid Based Spine Care J. 3:55–59. 2012.

|

|

9.

|

Tasca L and Reinke T: Aneurysmal bone cyst

in a 21-year-old woman presenting with chronic low back pain in a

chiropractic office: A case report. J Altern Complement Med. Feb

25–2013.(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

10.

|

Levin DA, Hensinger RN and Graziano GP:

Aneurysmal bone cyst of the second cervical vertebrae causing

multilevel upper cervical instability. J Spinal Disord Tech.

19:73–75. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Vale BP, Alencar FJ, de Aguiar GB and de

Almeida BR: Vertebral aneurysmatic bone cyst: study of three cases.

Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 63:1079–1083. 2005.(In Portuguese).

|

|

12.

|

Garg S, Mehta S and Dormans JP: Modern

surgical treatment of primary aneurysmal bone cyst of the spine in

children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 25:387–392. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|