Introduction

Fracture not only directly destroys bone integrity,

but also causes damage to local soft tissues and interrupts blood

flow, which is followed by the onset of ischemic-hypoxia in the

local bone tissue. The poor oxygen supply and nutrient deficiency

at the fracture site affects the fracture healing, particularly

without timely treatment, as the ischemic-hypoxia deteriorates the

physiological status of local osteoblast cells and inhibits bone

repair (1). Oxygen deprivation under

ischemic conditions causes functional impairment of the cells and

often structural tissue damage (2).

Furthermore, ischemia at fracture sites is the key cause of delayed

union or non-union fracture healing, and it is rarely a solitary

factor affecting fracture repair (3). Studies have shown that the early stages

of fracture in humans are characterized by inflammation and

hypoxia, and the initial inflammatory phase of fracture represents

a critical step for the outcome of the healing process (4–6).

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) has a regulatory function

during inflammation resolution in vivo (7,8).

HIF-1 is a transcription factor that acts as a

master regulator in oxygen homeostasis, existing as a heterodimer

composed of α and β subunits. HIF-1β, an aryl hydrocarbon receptor

nuclear translocator, is expressed in normoxic cells

constitutively; HIF-1α is continuously synthesized and only present

in hypoxic cells, due to rapid degradation by the

ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions (9). HIF-1α plays a key role in the cellular

response to hypoxia and is involved in glucose metabolism, vascular

remodeling and erythropoiesis via gene activation (10), in addition to being required for

solid tumor formation and embryonic vascularization (11). When cells are exposed to hypoxia,

HIF-1α initiates the protective and adaptive mechanism; if this is

not sufficient to rescue cells from the severe hypoxia, the cells

die via apoptosis and even necrosis (12).

Apoptosis, which is also called programmed cell

death, is induced by hypoxic conditions, which cause decreases in

the mitochondrial membrane potential and the release of cytochrome

c (13). The released

cytochrome c then stimulates the protein caspase 9, which

activates the apoptosis executioner caspase 3, thus leading to cell

death (14). It has been reported

that the activation of HIF-1α delays inflammation resolution by

reducing neutrophil apoptosis (7).

It has also been demonstrated that HIF-1α may act as a protective

factor in the apoptotic process of cardiac fibroblasts and

represent a potential therapeutic target for heart remodeling

following injury due to hypoxia (15). HIF-1α plays a role in hypoxia-induced

apoptosis and does not only stimulate, but may also prevent

apoptosis (16).

In the present study, the viability of the

osteoblast cell line MC3T3-E1 was investigated following exposure

to hypoxia, and HIF-1α protein expression was determined. The

HIF-1α level was then manipulated and the reduction in the

viability of the MC3T3-E1 cells in response to the hypoxia was

re-evaluated.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

Osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells were purchased from the

American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured

in α-Minimum Essential Media (αMEM; Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen

Life Technologies) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Subsequent to

reaching 85–95% confluence, the MC3T3-E1 cells were washed with

0.1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and detached with 0.25%

trypsin (dissolved in 0.1% PBS; Ameresco Inc., Framingham, MA, USA)

with 0.025% EDTA and subcultured. To upregulate the HIF-1α, a

murine HIF-1α coding sequence was amplified and cloned into a

eukaryotic expression vector, pcDNA3.1 (+) (Invitrogen Life

Technologies), and confirmed by sequencing. HIF-1α-pcDNA3.1 (+), or

chloramphenicol acetyl transferase (CAT)-pcDNA3.1 (+) vectors were

then transfected into MC3T3-E1 cells to upregulate the HIF-1α level

or act as a control, respectively. The positive clone, MC3T3-E1

(HIF-1α), and MC3T3-E1 (Con) were selected in the presence of 800

µg/ml G418 and maintained in medium containing G418 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) at 400 µg/ml. To suppress

HIF-1α expression, HIF-1α-specific small interfering (si)RNAs and

siRNA control (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA)

were utilized at a concentration of 40 nM. Each siRNA was

transfected into the MC3T3-E1 cells using Lipofectamine® 2000

(Invitrogen Life Technologies).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total mRNA was extracted from the MC3T3-E1 or

MC3T3-E1 (HIF-1α) cells with the RNeasy® Mini kit (Qiagen,

Valencia, CA, USA), and an RNase inhibitor (Promega Corp., Madison,

WI, USA) was then added. A SYBR® Green RT-qPCR kit (Takara, Tokyo,

Japan) was used for the RT-qPCR analysis of HIF-1α mRNA, and

tubulin was used as a reference gene. The ∆∆Ct method was used for

relative quantification (17).

Protein sample isolation and western

blot analysis

Whole MC3T3-E1 or MC3T3-E1 (HIF-1α) cells were

collected and lyzed with a cell lysis reagent (Pierce, Rockford,

IL, USA). Protein samples were then treated with a protease

inhibitor cocktail kit (Roche Biochemicals, Basel, Switzerland) and

quantified with a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA). SDS-PAGE gel (8–12%) was used

to separate the protein samples, which were then transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. HIF-1α and tubulin protein

levels were detected by immunoblot analysis using rabbit polyclonal

antibodies against mouse HIF-1α (#ab82832) or tubulin (#ab18251;

1:500; Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G

conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Pierce) and an enhanced

chemiluminescence detection system (SuperSignal® West Femto;

Pierce) were used for detection. The HIF-1α level was expressed as

a percentage relative to tubulin expression.

Cell viability determination by MTT

assay

MC3T3-E1 cells with overexpression of HIF-1α or CAT

were seeded in 96-well plates. Upon reaching 85% confluence, the

medium was substituted with αMEM containing 2% FBS. At different

time-points post-normoxia or -hypoxia treatment, with or without

siRNA transfection, the MTT assay (Invitrogen Life Technologies)

was conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The

optical density was then measured at 570 nm using a

spectrophotometer.

Determination of caspase

activation

MC3T3-E1 or MC3T3-E1 (HIF-1α) cells were seeded on

six-well plates and treated with hypoxia for 24 or 48 h. The

activity of caspase 3 was determined as previously described

(18). Briefly, MC3T3-E1 or MC3T3-E1

(HIF-1α) cells were pelleted and resuspended in lysis buffer, prior

to being incubated with Ac-DEVD-AMC fluorogenic peptide substrates

(BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) for caspase 3 for 30 to 60 min

at 37°C. The yellow-green fluorescence of the reaction product was

monitored on a spectrofluorometer by setting the excitation and

emission wavelengths to 380 and 440 nm, respectively. The amount of

yellow-green fluorescence was proportional to the amount of active

caspase 3 present in the samples. The increase in caspase activity

was expressed as a relative value to the control group.

Detection of apoptotic cells

MC3T3-E1 or MC3T3-E1 (HIF-1α) cells were seeded into

Nunc™ LabTek™ II chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International Corp.,

Rochester, NY, USA) and subjected to hypoxia with or without siRNA

transfection. The cells were then fixed, washed and stained with 1

µg/ml Hoechst 33528 (Invitrogen Life Technologies) using standard

procedures (19). Apoptotic cells

were screened and counted under a fluorescence microscope (Carl

Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) using a 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

filter set.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA)

was used for statistical analyses. The Student's t-test was used to

analyze the difference between two groups. Data are presented as

the mean ± standard error of the mean, and P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Viability and HIF-1α expression of

MC3T3-E1 cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions

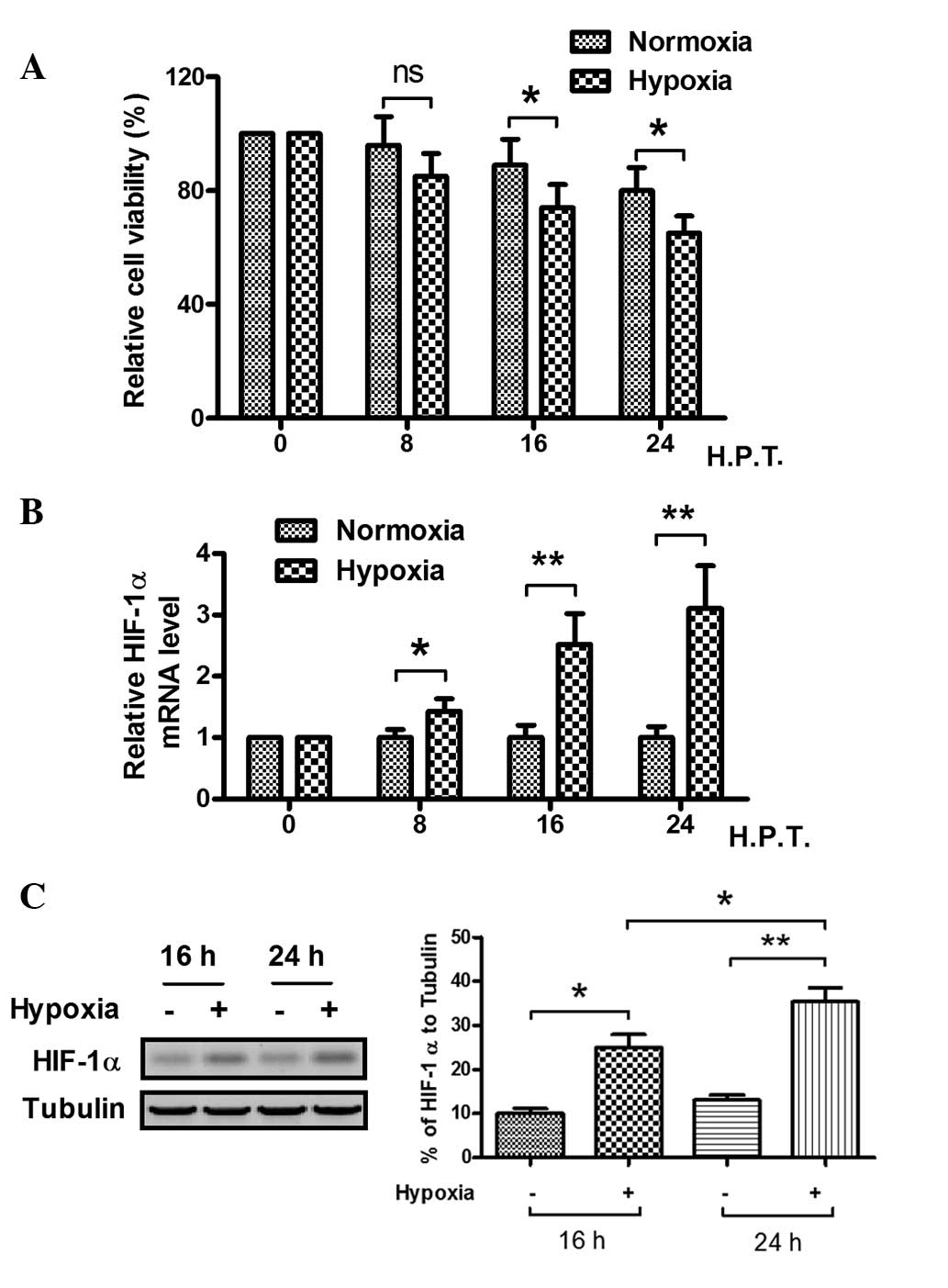

To explore the effect of hypoxia on the MC3T3-E1

cell line, the viability and HIF-1α protein levels of the cells

were examined. In hypoxic and normoxic conditions, the viability of

the cells was observed by MTT assay. The relative cell viability

decreased significantly after 16 h in hypoxia, as compared with the

cell viability in the normoxic condition (Fig. 1A). When the MC3T3-E1 cells were

cultured in 1% O2 conditions for 8 h or longer, the

relative HIF-1α mRNA level became higher than that of cells

cultured in 20% O2 conditions, particularly when the

cells were cultured for >16 h, as demonstrated by fluorescence

qPCR (Fig. 1B). Western blot

analysis was also conducted to analyze HIF-1α expression at the

protein level, as shown in Fig. 1C.

The HIF-1α expression in the MC3T3-E1 cells was significantly

higher when the cells were cultured under hypoxic conditions for 16

and 24 h. These results suggest that the hypoxic condition reduces

the viability of MC3T3-E1 cells and induces HIF-1α protein

expression.

Effect of upregulated HIF-1α

expression on the hypoxia-induced decrease in cell viability

As stated previously, the viability of cells was

decreased and the expression of HIF-1α was increased by the hypoxic

condition. In order to elucidate the effect of HIF-1α expression on

the viability decrease in the MC3T3-E1 cell line caused by hypoxia,

the viability of cells with forced expression of HIF-1α was

investigated using an MTT assay. As shown in Fig. 2A and B, significantly high levels of

HIF-1α expression were confirmed in the HIF-1α-pcDNA3.1-transfected

cells, as compared with the hypoxic and control groups. In

addition, as shown in Fig. 2C, the

MTT assay demonstrated that the viability of the MC3T3-E1 cells was

increased by the forced expression of HIF-1α. These results showed

that the effect of the forced HIF-1α expression was in contrast to

the effect of hypoxia on the viability of MC3T3-E1 cells.

Effect of HIF-1α-knockdown on the

hypoxia-induced decrease in cell viability

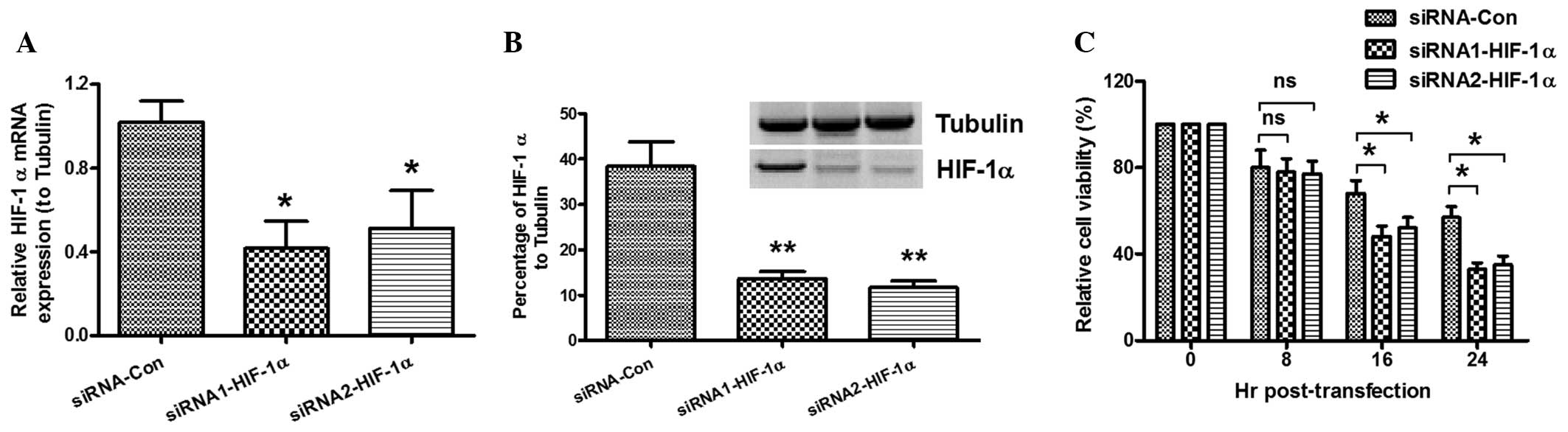

To detect the role of HIF-1α in the hypoxia-induced

decrease in cell viability, MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured under

hypoxic conditions and transfected with siRNA. The MTT assay and

western blot analysis were then conducted to confirm the relative

expression levels of HIF-1α to tubulin and determine cell

viability. As shown in Fig. 3A, low

levels of HIF-1α mRNA expression were found post-siRNA

transfection. The western blotting results also demonstrated that

the HIF-1α expression in the cells transfected with HIF-1α-siRNA

was significantly lower than that in the siRNA-control group

(Fig. 3B). The viability of the

MC3T3-E1 cells post-siRNA transfection under hypoxic conditions was

determined by MTT assay. Fig. 3C

shows that the viability of the cells was reduced by

HIF-1α-knockdown. These results suggest that HIF-1α-knockdown

enhances the hypoxia-induced decrease in cell viability.

Effect of HIF-1α on the

hypoxia-induced osteoblast apoptosis and caspase 3 activity

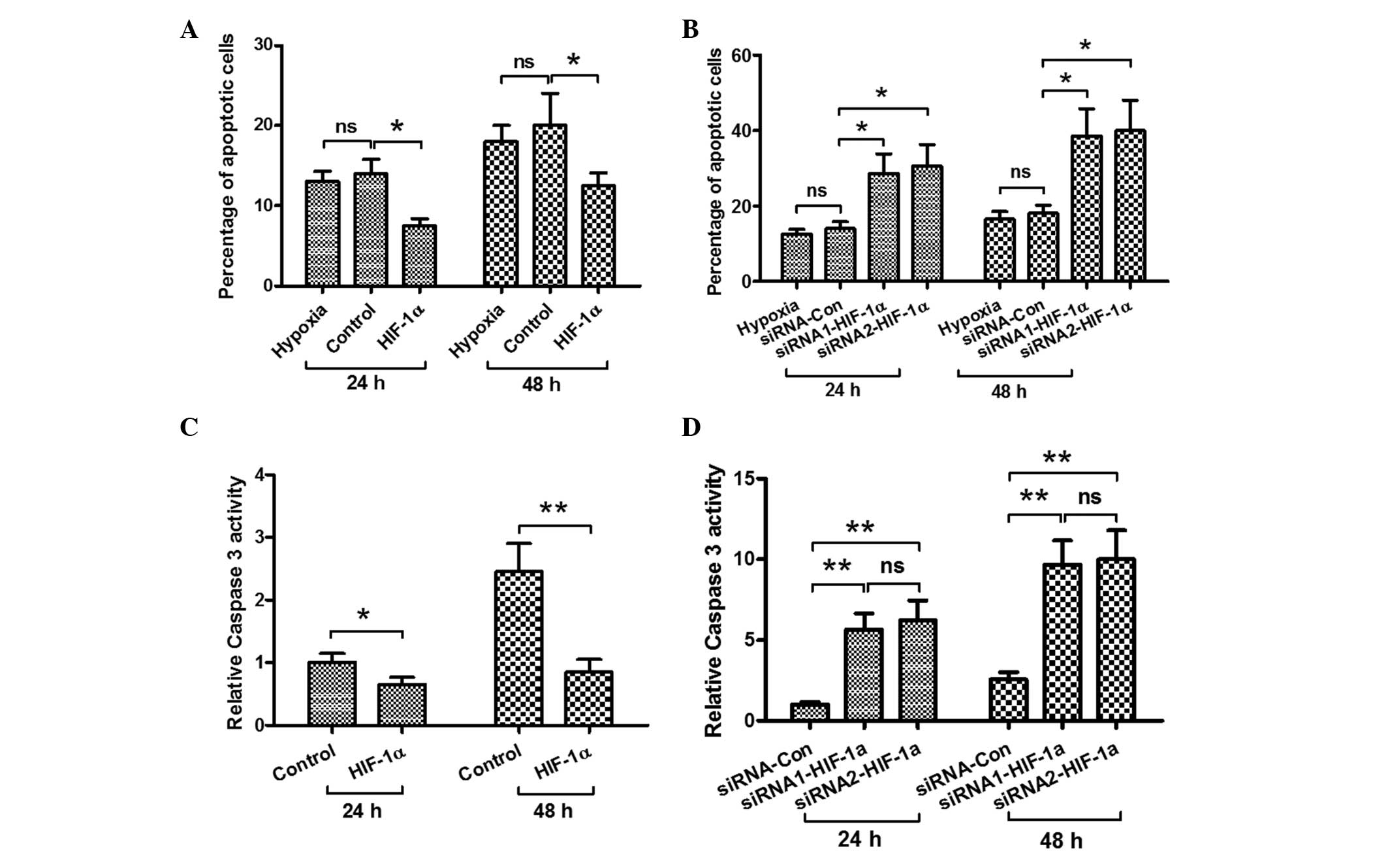

In order to explore the possible mechanism by which

HIF-1α attenuates the hypoxia-induced decrease in MC3T3-E1 cell

viability, the effects of HIF-1α on the hypoxia-induced osteoblast

apoptosis and the activity of caspase 3 were investigated. The

cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1 (+) (control) and

HIF-1α-pcDNA3.1 (+) under hypoxic conditions. As shown in Fig. 4A, forced HIF-1α expression

significantly suppressed the hypoxia-induced apoptosis after 24 and

48 h. By contrast, when the cells were transfected with siRNA

(control) and two types of siRNA-HIF-1α during hypoxia, the levels

of HIF-1α in the siRNA-HIF-1α-transfected cell groups were

decreased and the percentage of cells undergoing apoptosis was

increased significantly (Fig. 4B).

In addition, the activity of caspase 3 was examined; as shown in

Fig. 4C, the activity of caspase 3

was inhibited in the cells with forced HIF-1α expression under

hypoxia after 24 and 48 h. By contrast, in the

siRNA-HIF-1α-transfected osteoblasts, the hypoxia-induced caspase 3

activity was enhanced (Fig. 4D).

These results show that HIF-1α inhibits hypoxia-induced osteoblast

apoptosis.

Discussion

Secondary or indirect bone healing typically

involves four phases, known as the inflammatory, soft callus, hard

callus and remodeling phases (20).

Numerous factors can affect fracture healing, including the

coordination of multiple cell types (such as osteoblasts and

chondrocytes); cytokines (such as transforming growth factor-β,

basic fibroblast growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor),

which have a regulatory effect on the initiation and development of

the fracture repair process (21–23); and

the oxygen level of the tissues at the fracture site. Since oxygen

plays a critical role as a participant in multiple basic cellular

processes, hyperbaric oxygen therapy is one of the methods used to

promote fracture healing by delivering 100% oxygen at pressures

greater than one atmosphere (24).

Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) can also accelerate

fracture healing by inducing the homing of circulating osteogenic

progenitors to the fracture site (25); furthermore, LIPUS treatment combined

with functional electrical stimulation treatment has shown better

effects in accelerating new bone formation (26). In addition, improvements in the

adaptation of osteoblasts and chondrocytes to hypoxia ameliorate

the physiological status of these cells, which are subject to

hypoxia (27).

The protective role of HIF-1α has been confirmed in

various types of cells (28). Cells

with high HIF-1α levels showed more resistance to apoptosis caused

by hypoxia and glucose deprivation than did cell lines with low

HIF-1α expression under normoxia (28). It can thus be concluded that HIF-1α

plays a role in hypoxia-induced apoptosis, and acts as an

antiapoptotic factor (12). In the

present study, the viability of MC3T3-E1 cells decreased and the

expression of HIF-1α protein in the MC3T3-E1 cells increased under

hypoxic conditions. It was also found that the viability of

HIF-1α-transfected MC3T3-E1 cells was higher than that in cells

without forced expression of HIF-1α (Fig. 2C), whereas HIF-1α-knockdown by siRNA

in MC3T3-E1 cells enhanced the hypoxia-induced decrease in cell

viability (Fig. 3C). It was

ascertained that the forced expression of HIF-1α in the MC3T3-E1

cell line attenuated the hypoxia-induced decrease in cell viability

by inhibiting apoptosis. These results indicate that HIF-1α plays a

key role in the hypoxia-induced decrease in osteoblast

viability.

In conclusion, the viability of the MC3T3-E1 cell

line decreased under hypoxia and HIF-1α expression was upregulated.

The forced expression of HIF-1α in the MC3T3-E1 cell line

attenuated the hypoxia-induced decrease in osteoblast viability by

inhibiting apoptosis. These present findings provide novel insight

into the mechanism underlying the hypoxia-induced decrease in cell

viability, and indicate that HIF-1α expression affects cell

viability by inhibiting apoptosis.

References

|

1

|

Lu C, Wang X, Sinha A, et al: The role of

oxygen during fracture healing. Bone. 52:220–229. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Scaringi R, Piccoli M, Papini N, et al:

NEU3 sialidase is activated under hypoxia and protects skeletal

muscle cells from apoptosis through the activation of the epidermal

growth factor receptor signaling pathway and the hypoxia-inducible

factor (HIF)-1α. J Biol Chem. 288:3153–3162. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lu C, Hu D, Miclau T and Marcucio RS:

Ischemia leads to delayed-union during fracture healing: a mouse

model. J Orthop Res. 25:51–61. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kolar P, Gaber T, Perka C, Duda GN and

Buttgereit F: Human early fracture hematoma is characterized by

inflammation and hypoxia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 469:3118–3126.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hoff P, Maschmeyer P, Gaber T, et al:

Human immune cells' behavior and survival under bioenergetically

restricted conditions in an in vitro fracture hematoma model. Cell

Mol Immunol. 10:151–158. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Hoff P, Gaber T, Schmidt-Bleek K, et al:

Immunologically restricted patients exhibit a pronounced

inflammation and inadequate response to hypoxia in fracture

hematomas. Immunol Res. 51:116–122. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Elks PM, van Eeden FJ, Dixon G, et al:

Activation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (hif-1α) delays

inflammation resolution by reducing neutrophil apoptosis and

reverse migration in a zebrafish inflammation model. Blood.

118:712–722. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Eltzschig HK and Carmeliet P: Hypoxia and

inflammation. N Engl J Med. 364:656–665. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Salceda S and Caro J: Hypoxia-inducible

factor 1alpha (HIF-1alpha) protein is rapidly degraded by the

ubiquitin-proteasome system under normoxic conditions. Its

stabilization by hypoxia depends on redox-inducud changes. J Biol

Chem. 272:22642–22647. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Corn PG, Ricci MS, Scata KA, et al: Mxi1

is induced by hypoxia in a HIF-1-dependent manner and protects

cells from c-Myc-induced apoptosis. Cancer Biol Ther. 4:1285–1294.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ryan HE, Lo J and Johnson RS: HIF-1alpha

is required for solid tumor formation and embryonic

vascularization. EMBO J. 17:3005–3015. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Piret JP, Mottet D, Raes M and Michiels C:

Is HIF-1alpha a pro-or an anti-apoptotic protein? Biochem

Pharmacol. 64:889–892. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Sinha K, Das J, Pal PB and Sil PC:

Oxidative stress: the mitochondria-dependent and

mitochondria-independent pathways of apoptosis. Arch Toxicol.

87:1157–1180. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang TM, Qi SN, Zhao N, et al: Induction

of apoptosis through caspase-independent or caspase-9-dependent

pathway in mouse and human osteosarcoma cells by a new nitroxyl

spin-labeled derivative of podophyllotoxin. Apoptosis. 18:727–738.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Yang B, He K, Zheng F, et al:

Over-expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha in vitro

protects the cardiac fibroblasts from hypoxia-induced apoptosis. J

Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 15:579–586. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Greijer AE and van der Wall E: The role of

hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) in hypoxia induced apoptosis. J

Clin Pathol. 57:1009–1014. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(ΔΔC(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Seong GJ, Park C, Kim CY, et al:

Mitomycin-C induces the apoptosis of human Tenon's capsule

fibroblast by activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1 and caspase-3

protease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 46:3545–3552. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sareen D, van Ginkel PR, Takach JC, et al:

Mitochondria as the primary target of resveratrol-induced apoptosis

in human retinoblastoma cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

47:3708–3716. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kumar G and Narayan B: The biology of

fracture healing in long bonesClassic Papers in Orthopaedics.

Banaszkiewicz P and Kader D: Springer; London: pp. 531–533.

2014

|

|

21

|

Bolander ME: Regulation of fracture repair

by growth factors. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 200:165–170. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Cho TJ, Gerstenfeld LC and Einhorn TA:

Differential temporal expression of members of the transforming

growth factor beta superfamily during murine fracture healing. J

Bone Miner Res. 17:513–520. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Nakamura T, Hara Y, Tagawa M, et al:

Recombinant human basic fibroblast growth factor accelerates

fracture healing by enhancing callus remodeling in experimental dog

tibial fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 13:942–949. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bennett MH, Stanford RE and Turner R:

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for promoting fracture healing and

treating fracture non-union. Cocbrane Database Syst Rev.

11:CD0047122012.

|

|

25

|

Kumagai K, Takeuchi R, Ishikawa H, et al:

Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound accelerates fracture healing by

stimulation of recruitment of both local and circulating osteogenic

progenitors. J Orthop Res. 30:1516–1521. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Hu J, Qu J, Xu D, Zhang T, Qin L and Lu H:

Combined application of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound and

functional electrical stimulation accelerates bone-tendon junction

healing in a rabbit model. J Orthop Res. 32:204–209. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Steinbrech DS, Mehrara BJ, Saadeh PB, et

al: Hypoxia regulates VEGF expression and cellular proliferation by

osteoblasts in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 104:738–747. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Akakura N, Kobayashi M, Horiuchi I, et al:

Constitutive expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha renders

pancreatic cancer cells resistant to apoptosis induced by hypoxia

and nutrient deprivation. Cancer Res. 61:6548–6554. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|