Introduction

Hyperpigmentation is commonly observed in humans

following skin damage and during the healing response; it includes

post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation after burns, wounds or laser

surgery. Hyperpigmentation is a major concern for the majority of

people it affects as it induces significant cosmetic problems that

may affect quality of life. However, the treatment of

hyperpigmentation remains a challenge and the results are

discouraging. Recently, a number of studies have focused on pigment

cells and wound healing (1–4); however, knowledge of skin

repigmentation following cutaneous injury remains sparse.

The role of angiotensin II (Ang II) in the control

of systemic blood pressure and volume homeostasis is well known and

has been extensively studied (5,6).

Recently, it was suggested that Ang II is also involved in the

healing of skin wounds. It has been proposed that exogenously

administered Ang II is a potent accelerator of cutaneous wound

repair (7,8). These reports indicated that the topical

administration of Ang II accelerated skin wound healing by

stimulating dermal repair, including angiogenesis and epidermal

repair, in vivo. Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that

Ang II is angiogenic and modulates the proliferation, growth factor

production and chemotaxis of numerous cell types (8–10).

Steckelings et al (11)

reported that human skin expresses Ang II type 1 (AT1) and type 2

(AT2) receptors, and that AT1 and AT2 receptor expression is

markedly enhanced within the epidermal and dermal areas of scar

tissue (12). A previous study

reported that inhibiting the AT1 receptor limited murine melanoma

growth (13). In addition,

Steckelings et al (11)

detected the expression of AT1 mRNA in cultured primary

melanocytes, suggesting its possible function in melanocytes.

Pigment production is complex and controlled by

numerous extrinsic and intrinsic factors involved in melanin

synthesis and melanocyte transport. Melanogenesis is controlled by

complex regulatory mechanisms. The genes encoding tyrosinase (TYR)

and TYR-related proteins contain common transcription initiation

sites, particularly microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

(MITF) binding sites. MITF serves a crucial function in the

transcriptional regulation of melanogenesis (14). The intracellular signal transduction

pathways of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), protein kinase C

(PKC) and nitrogen oxide (NO) are involved in the regulation of

melanogenesis (15). A number of

previous studies have indicated that cAMP and PKC are involved in

key signal transduction pathways that participate in the regulation

of melanogenesis (16–18). In the cardiovascular system, Ang II

shares certain subcellular pathways with the following pathways,

widely interacting with them: AT1, PKC, and

Na+/H+ exchange (NHE) (19), endothelin-1 (ET-1) and NO (20) and cAMP (21). The present study was based on the

hypothesis that Ang II may be able to modulate melanocyte

melanogenesis via different pathways. To clarify this issue, the

effects of Ang II on human melanocyte melanogenesis were

investigated in order to elucidate the possible mechanisms

involved.

Materials and methods

Compounds and drugs

Mouse polyclonal antibodies against MITF (sc-56725)

and TYR (sc-20035), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibodies (sc-2005) were purchased

from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). A

protein quantification kit and agarose were purchased from Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc. (Hercules, CA, USA). PCR Master Mix was

purchased from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI, USA).

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), M254 medium and human melanocyte

growth supplements were purchased from Cascade Biologics, Inc.

(Mansfield, UK). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and an RNeasy Mini kit

were from Qiagen, Inc. (Valencia, CA, USA). Ang II, H-89 (PKA

inhibitor) and Ro-32-0432 (PKC inhibitor) were from EMD Millipore

(Billerica, MA, USA). L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (L-DOPA), EDTA,

glycine, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and Tris were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Melanocyte culture

The present study was ethically approved by the

General Hospital of Beijing Military Region of PLA. Primary

melanocyte cultures were established as follows: Normal melanocytes

were isolated from the epidermis of human foreskins. Skin grafts

were cut into 5×5 mm pieces and incubated with trypsin-EDTA (0.25%

trypsin, 0.02% EDTA) at 4°C overnight. Trypsin activity was

required to separate the epidermis from the dermis, via

intercellular detachment. The next day, trypsin activity was

neutralized by adding FBS in a 1:1 ratio and replacing it with PBS

solution. The epidermis was separated from the dermis using sterile

forceps. The specimens were pipetted thoroughly to separate the

cells and form cell-rich suspensions. The solid waste tissue was

removed and the suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min.

Then, melanocytes were selectively grown in M254 medium containing

human melanocyte growth supplements. The cell number was adjusted

to 2.5×104 cells/cm2. Cultures were

maintained at 37°C in a humidified 95% air and 5% CO2

atmosphere. The medium was changed at 2–3-day intervals, and the

cultures were routinely examined for contamination and cell

outgrowth. Cells were split at confluence using 5-min trypsin

treatment at room temperature. Subculturing was conducted once a

week and experiments were carried out from passages II–IV.

Treatment with Ang II alone or in

combination with H-89 or Ro-32-0432

Confluent cells were plated at subconfluent

densities (2×105 cells) in 6-well plates and grown for 4

days until confluent. Then, they were treated with different

concentrations (0.01, 0.1, 1, 10 and 100 nM) of Ang II for 24 h. In

some experiments, the cells were incubated with 1 µM H-89 or

Ro-32-0432 for 60 min prior to stimulation with 100 nM Ang II. The

culture medium was removed and the cells were washed twice with

PBS. Then, fresh assay medium supplemented with 0.1% FBS was added

for 24 h. Subsequently, the melanin content assay was performed,

and TYR activity and melanin content were determined. Cell

homogenates and supernatants were collected for RNA extraction

using the RNeasy Mini kit and for protein quantification using the

kit from Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. by a procedure based on the

Bradford method.

TYR activity assay

Melanocytes were treated with Ang II for the

indicated durations, and then washed with ice-cold 1X PBS. Lysis

buffer, containing 150 µl 1% Triton X-100 in 0.1 M phosphate

buffer, was added to each 6-well plate. Cells were scraped and

transferred to a 1.5-ml tube, lysed using 3–5 freeze-thaw cycles in

liquid nitrogen and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5–10 min at 4°C.

Samples (300–500 µg/80 µl) were transferred to a new 96-well plate

on ice. L-DOPA (20 µl, 5 mM) was added to each well, the plate was

incubated at 37°C for 1 h and the absorbance was measured at 475 nm

using a DU-70 spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA,

USA).

Melanin content assay

Melanin content was determined using a standard

procedure (22). Cells were lysed

with 200 µl 1 N NaOH and pipetted repeatedly to homogenize them.

Then, the cell extract was transferred to 96-well plates. Relative

melanin content was determined by absorbance at 405 nm using a

Synergy H1MF enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay plate reader

(BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA).

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase

reaction were performed as described previously (23). The MITF and TYR mRNA expression

levels were evaluated using RT-qPCR. Total RNA was extracted at the

indicated time points using a TRIzol kit (Invitrogen Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse-transcribed using an

RT kit (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Semi-quantitative PCR was

performed using PCR Master Mix and primers for MITF and TYR;

Table I lists the primer sequences

and amplicon size. PCR was performed using a touchdown protocol as

previously described (24). Briefly,

touchdown PCR was performed using the following program: 1 cycle at

94°C for 2 min, 12 cycles at 92°C for 20 sec, 68°C for 30 sec and

70°C for 45 sec with a reduction of 1°C per cycle, and 22 cycles at

92°C for 20 sec, 55°C for 30 sec and 70°C for 45 sec. PCR products

were separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels and visualized

with ethidium bromide staining. PCR band intensity was expressed as

the relative intensity against β-actin.

| Table I.Primers used in reverse

transcription-quantitative polymase chain reaction. |

Table I.

Primers used in reverse

transcription-quantitative polymase chain reaction.

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Size (bp) |

|---|

| MITF | F:

CACAACCTGATTGAACGAAG |

|

|

| R:

GTGGATGGAATAAGGGAAAG | 284 |

| TYR | F:

ACGATGTGGACGAGTGT |

|

|

| R:

CAGAGGCAGGTGAAGGT | 133 |

| β-actin | F:

ATCATGTTTGAGACCTTCAACA |

|

|

| R:

CATCTCTTGCTCGAAGTCCA | 318 |

|

Western blot analysis

MITF and TYR protein expression was evaluated using

western blot analysis. Isolated human foreskin sheets were

homogenized using a pestle in lysis buffer and centrifuged for 30

min at 15,000 × g at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and protein

concentration determined using the protein quantification kit,

based on the bicinchoninic acid method. Proteins (20 µg) were

denatured with SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 min and separated in

10–12% polyacrylamide gels (Novex; Life Technologies, Grand Island,

NY, USA). Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred in

1X transfer buffer (25 mM Tris, 192 mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, 20%

methanol, pH 8.4) to a 0.45-µm Immobilon-P polyvinylidene

difluoride membrane (EMD Millipore) in a Mini PROTEAN II Transfer

Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) set at a constant voltage of 120

mV for 2 h. Membranes were blocked in 5% non-fat dry milk in

Tris-buffered saline (TBS) solution for ≥1 h at room temperature.

Blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal mouse

anti-MITF (1:1,1000) or anti-TYR (1:1,000) antibodies. Membranes

were washed three times with TBS containing 1% Triton X-100

(TBS-T), incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies

(1:2,000) for 2 h at room temperature, then washed 4 times with

TBS-T. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by exposing membrane

blots to a chemiluminescent solution and the proteins were

visualized on X-ray film using an enhanced chemiluminescence

western blot detection system (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.,

Rockford, IL, USA). Three independent experiments were performed in

triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

software, version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are

presented as the mean ± standard error. Statistical analysis

between groups was performed using analysis of variance. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

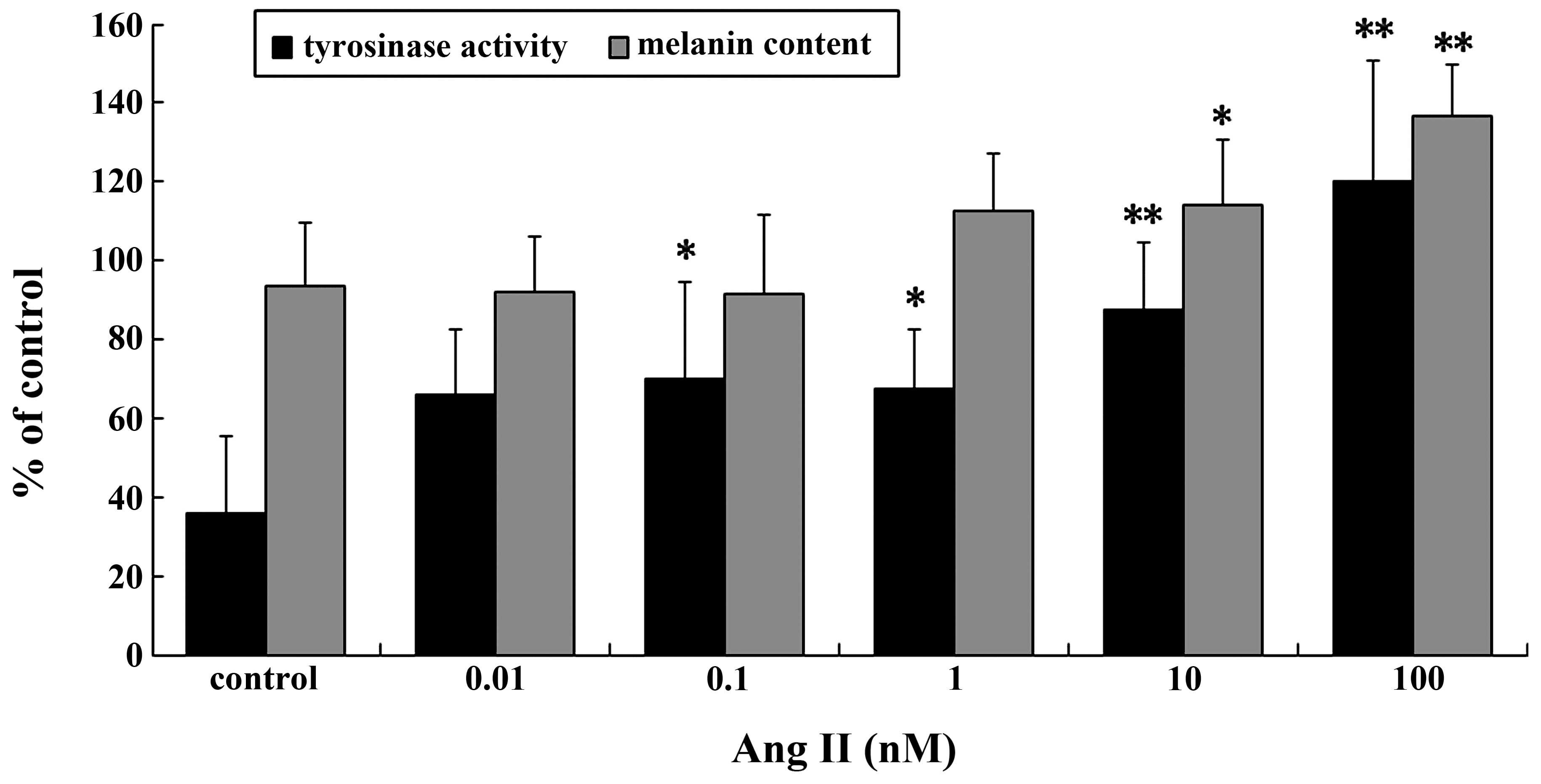

Ang II regulates TYR activity and

melanin content

TYR activity and melanin content increased

significantly in a dose-dependent manner following treatment with

Ang II (Fig. 1). Significant

increases in TYR activity and melanin content were observed in the

cells incubated with 0.1–100 nM Ang II for 24 h. The maximal

increases were achieved with 100 nM Ang II (P<0.01).

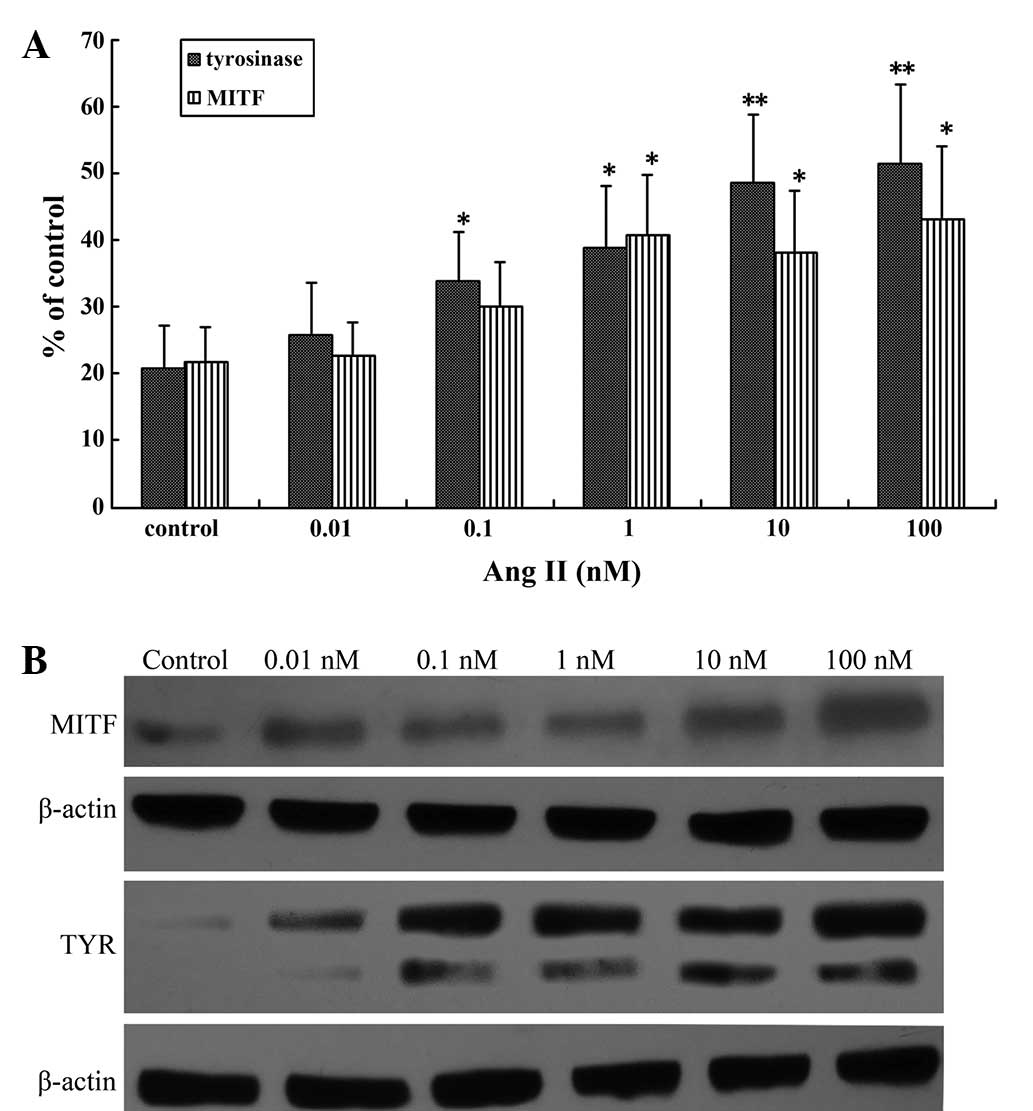

Ang II regulates MITF and TYR mRNA and

protein expression

MITF is the master regulator of melanogenesis,

regulating the expression of TYR (7,25), the

key regulatory enzyme in melanin biosynthesis (26). Investigation of the effects of Ang II

on MITF and TYR mRNA and protein expression levels in human

melanocytes by RT-qPCR and western blot analysis revealed that

there was a significant increase in transcription following a 24-h

incubation with higher concentrations of Ang II (0.1–100 nM;

Fig. 2A). A maximal increase was

achieved with 100 nM Ang II (P<0.01; Fig. 2B).

PKC inhibitor inhibits Ang II-induced

melanogenesis

Previous studies have reported that PKA and PKC

activation stimulates melanogenesis (27,28).

Therefore, in the present study, H-89 (a PKA inhibitor) and

Ro-32-0432 (a PKC inhibitor) were used to evaluate the molecular

mechanisms by which Ang II induces melanogenesis. Melanin content

and TYR activity were detected under the combined effect of 100 nM

Ang II and 1 µM H-89 or Ro-32-0432. Ro-32-0432 completely

attenuated the Ang II-induced increases in melanin content and TYR

activity while H-89 had no effect on melanin synthesis (Fig. 3A). TYR mRNA and protein expression

levels were detected following the combined treatment with 100 nM

Ang II and Ro-32-0432. RT-qPCR and western blot analysis revealed

that TYR expression was markedly decreased following the combined

Ang II and Ro-32-0432 treatment (Fig.

3B).

Discussion

The role of Ang II in wound healing has not been

fully elucidated; however, previous studies have indicated that Ang

II is a potent accelerator of cutaneous wound repair, which certain

studies have demonstrated by wounding healing skin (7,8,29). Notably, previous studies have

demonstrated significant AT1 receptor expression in primary human

melanocytes (12), and found that

inhibition of the AT1 receptor limited murine melanoma growth

(13). To the best of our knowledge,

the present study provides the first indication of the role of Ang

II in human melanocyte melanogenesis and elucidates the possible

mechanisms involved.

Melanogenesis is controlled by complex regulatory

mechanisms, and TYR is the rate-limiting enzyme in melanogenesis.

In order to investigate the effect of Ang II on human melanocyte

melanogenesis, melanocyte TYR activity and melanin content were

evaluated. The results indicate that Ang II significantly increased

TYR activity and melanin synthesis, suggesting that Ang II

stimulates melanogenesis.

Melanin synthesis is stimulated by numerous

effectors, including cAMP- elevating agents, ultraviolet (UV)

light, and TYR. The primary transcription factor in the regulation

of TYR gene expression is MITF, which serves a crucial function in

the regulation of various aspects of melanocyte survival and

differentiation (30). Studies

suggest that MITF mediates cAMP-induced increases in the expression

of a number of melanogenic proteins (27,31). In

order to evaluate the mechanism by which Ang II induces

pigmentation, the effects of Ang II on MITF and TYR mRNA and

protein expression levels were investigated in human melanocytes.

MITF expression was significantly increased following treatment

with 100 nM Ang II. RT-qPCR and western blot analysis revealed that

Ang II upregulated the expression levels of pigment cell-specific

genes, specifically TYR and MITF, in melanocytes, suggesting that

Ang II stimulates melanin synthesis by upregulating MITF in

melanocytes.

Previous studies of melanin synthesis signaling

pathways suggest that the cAMP/PKA and diacylglycerol (DAG)/PKC

pathways are involved in melanin synthesis; a number of

inextricably linked signaling pathways have been identified

(16–18). Previously, research on melanocyte

proliferation and melanogenesis signal transduction has focused on

the role of cAMP, where the cAMP pathway is a key modulator of

melanogenesis. Studies have shown that cAMP-induced increases in

the expression of numerous melanogenic proteins are mediated by

MITF (27,31). The cAMP pathway upregulates MITF,

which is crucial for key melanogenic proteins such as TYR,

TYR-related protein-1 (TRP-1) and TRP-2. Notably, Park et al

demonstrated that the cAMP pathway also upregulates PKC-β

expression via MITF (32). In the

present study, H-89 (PKA inhibitor) and Ro-32-0432 (PKC inhibitor)

were used to evaluate the molecular mechanism by which Ang II

induces melanogenesis. It was observed that the PKC inhibitor

completely attenuated the Ang II-stimulated increase in melanin

content and TYR activity, suggesting that Ang II stimulated

melanogenesis via the PKC pathway. The PKC pathway has been

identified to be an intracellular signaling pathway that regulates

melanogenesis. A previous study observed that adding

diacylglycerol, an endogenous PKC activator, to cultured human

melanocytes caused a rapid 3–4-fold increase in total melanin

content, and that a PKC inhibitor blocked this increase (17). Conversely, topical application of a

selective PKC inhibitor reduced pigmentation and blocked UV-induced

pigmentation in guinea pig skin (33). In cultured pigment cells, PKC

depletion reduced the melanin content markedly (34,35) and

blocked α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone-induced melanogenesis

completely (35). In addition, the

results of the present study indicate that H-89 had no effect on

melanin synthesis, suggesting that Ang II does not stimulate the

PKA pathway in human melanocytes. The present results are

consistent with the findings of Mehta and Griendling (21), which were that PKA activation should

not occur under Ang II-stimulated conditions. Molnar et al

(36) established that PKA is not

involved in Ang II-mediated cAMP response-binding element

activation in smooth muscle cells, which contradicts a study by

Funakoshi et al (37), which

reported that PKA was activated in response to Ang II stimulation.

Previous studies have also shown that Ang II mediates various

cellular functions involving PKC signaling in cardiovascular

function and disease (38). Müller

et al (39) reported that Ang

II inhibits renin gene transcription via the PKC pathway. The

results of the present study suggest that the PKC pathway mediates

the induction of TYR mRNA and protein expression by Ang II.

In summary, to the best of our knowledge, the

present study is the first to demonstrate the effects of Ang II on

melanogenesis and to identify the molecular mechanisms by which it

induces melanogenesis. Specifically, the present results

demonstrate that the Ang II-induced pigmentation effect in human

melanocytes requires PKC and that the mechanism involves the PKC

pathway and MITF upregulation. Collectively, these results may

provide a new strategy for the cosmetic study of

hyperpigmentation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the native English speaking

scientists of Elixigen Corporation for editing this manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Hirobe T: Proliferation of epidermal

melanocytes during the healing of skin wounds in newborn mice. J

Exp Zool. 227:423–431. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tobin DJ: The cell biology of human hair

follicle pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24:75–88. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nishimura EK: Melanocyte stem cells: A

melanocyte reservoir in hair follicles for hair and skin

pigmentation. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 24:401–410. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ito M, Liu Y, Yang Z, Nguyen J, Liang F,

Morris RJ and Cotsarelis G: Stem cells in the hair follicle bulge

contribute to wound repair but not to homeostasis of the epidermis.

Nat Med. 11:1351–1354. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

McKinney CA, Fattah C, Loughrey CM,

Milligan G and Nicklin SA: Angiotensin-(1–7) and angiotensin-(1–9):

Function in cardiac and vascular remodelling. Clin Sci (Lond).

126:815–827. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

RuizOrtega M, Lorenzo O, Rupérez M,

Esteban V, Suzuki Y, Mezzano S, Plaza JJ and Egido J: Role of the

renin-angiotensin system in vascular diseases: Expanding the field.

Hypertension. 38:1382–1387. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Takeda H, Katagata Y, Hozumi Y and Kondo

S: Effects of angiotensin II receptor signaling during skin wound

healing. Am J Pathol. 165:1653–1662. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Rodgers K, Abiko M, Girgis W, St Amand K,

Campeau J and di Zerega G: Acceleration of dermal tissue repair by

angiotensin II. Wound Repair Regen. 5:175–183. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rodgers KE, DeCherney AH, St Amand KM,

Dougherty WR, Felix JC, Girgis WW and di Zerega GS: Histologic

alterations in dermal repair after thermal injury effects of

topical angiotensin II. J Burn Care Rehabil. 18:381–388. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Nozawa Y, Matsuura N, Miyake H, Yamada S

and Kimura R: Effects of TH-142177 on angiotensin II-induced

proliferation, migration and intracellular signaling in vascular

smooth muscle cells and on neointimal thickening after balloon

injury. Life Sci. 64:2061–2070. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Steckelings UM, Wollschläger T, Peters J,

Henz BM, Hermes B and Artuc M: Human skin: Source of and target

organ for angiotensin II. Exp Dermatol. 13:148–154. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Steckelings UM, Henz BM, Wiehstutz S,

Unger T and Artuc M: Differential expression of angiotensin

receptors in human cutaneous wound healing. Br J Dermatol.

153:887–893. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Otake AH, Mattar AL, Freitas HC, Machado

CM, Nonogaki S, Fujihara CK, Zatz R and Chammas R: Inhibition of

angiotensin II receptor 1 limits tumor-associated angiogenesis and

attenuates growth of murine melanoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

66:79–87. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Widlund HR and Fisher DE:

Microphthalamia-associated transcription factor: A critical

regulator of pigment cell development and survival. Oncogene.

22:3035–3041. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee AY and Noh M: The regulation of

epidermal melanogenesis via cAMP and/or PKC signaling pathways:

Insights for the development of hypopigmenting agents. Arch Pharm

Res. 36:792–801. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Buscà R and Ballotti R: Cyclic AMP a key

messenger in the regulation of skin pigmentation. Pigment Cell Res.

13:60–69. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Gordon PR and Gilchrest BA: Human

melanogenesis is stimulated by diacylglycerol. J Invest Dermatol.

93:700–702. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Park HY and Gilchrest BA: Signaling

pathways mediating melanogenesis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand).

45:919–930. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

LeiteMoreira AF, CastroChaves P,

PimentelNunes P, LimaCarneiro A, Guerra MS, Soares JB and

Ferreira-Martins J: Angiotensin II acutely decreases myocardial

stiffness: A novel AT1, PKC and Na+/H+

exchanger-mediated effect. Br J Pharmacol. 147:690–697. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Berthold H, Just A, Kirchheim HR and Ehmke

H: Interaction between nitric oxide and endogenous vasoconstrictors

in control of renal blood flow. Hypertension. 34:1254–1258. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mehta PK and Griendling KK: Angiotensin II

cell signaling: Physiological and pathological effects in the

cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 292:C82–C97.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lei TC, Virador VM, Vieira WD and Hearing

VJ: A melanocyte-keratinocyte coculture model to assess regulators

of pigmentation in vitro. Anal Biochem. 305:260–268. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Virador VM, Kobayashi N, Matsunaga J and

Hearing VJ: A standardized protocol for assessing regulators of

pigmentation. Anal Biochem. 270:207–219. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Marin-Castaño ME, Elliot SJ, Potier M,

Karl M, Striker LJ, Striker GE, Csaky KG and Cousins SW: Regulation

of estrogen receptors and MMP-2 expression by estrogens in human

retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 44:50–59.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Aksan I and Goding CR: Targeting the

microphthalmia basic helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper transcription

factor to a subset of E-box elements in vitro and in

vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 18:6930–6938. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Halaban R, Pomerantz SH, Marshall S,

Lambert DT and Lerner AB: Regulation of tyrosinase in human

melanocytes grown in culture. J Cell Biol. 97:480–488. 1983.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bertolotto C, Abbe P, Hemesath TJ, Bille

K, Fisher DE, Ortonne JP and Ballotti R: Microphthalmia gene

product as a signal transducer in cAMP-induced differentiation of

melanocytes. J Cell Biol. 142:827–835. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Price ER, Horstmann MA, Wells AG,

Weilbaecher KN, Takemoto CM, Landis MW and Fisher DE:

alpha-Melanocyte-stimulating hormone signaling regulates expression

of microphthalmia, a gene deficient in Waardenburg syndrome. J Biol

Chem. 273:33042–33047. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Steckelings UM, Artuc M, Paul M, Stoll M

and Henz BM: Angiotensin II stimulates proliferation of primary

human keratinocytes via a non-AT1, non-AT2 angiotensin receptor.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 229:329–333. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gaggioli C, Buscà R, Abbe P, Ortonne JP

and Ballotti R: Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

(MITF) is required but is not sufficient to induce the expression

of melanogenic genes. Pigment Cell Res. 16:374–382. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Shibahara S, Takeda K, Yasumoto K, Udono

T, Watanabe K, Saito H and Takahashi K: Microphthalmia-associated

transcription factor (MITF): Multiplicity in structure, function,

and regulation. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 6:99–104. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Park HY, Wu C, Yonemoto L, MurphySmith M,

Wu H, Stachur CM and Gilchrest BA: MITF mediates cAMP-induced

protein kinase C-beta expression in human melanocytes. Biochem J.

395:571–578. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Park HY, Lee J, González S, MiddelkampHup

MA, Kapasi S, Peterson S and Gilchrest BA: Topical application of a

protein kinase C inhibitor reduces skin and hair pigmentation. J

Invest Dermatol. 122:159–166. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Niles RM and Loewy BP: Induction of

protein kinase C in mouse melanoma cells by retinoic acid. Cancer

Res. 49:4483–4487. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Park HY, Russakovsky V, Ao Y, Fernandez E

and Gilchrest BA: Alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone-induced

pigmentation is blocked by depletion of protein kinase C. Exp Cell

Res. 227:70–79. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Molnar P, Perrault R, Louis S and Zahradka

P: The cyclic AMP response element-binding protein (CREB) mediates

smooth muscle cell proliferation in response to angiotensin II. J

Cell Commun Signal. 8:29–37. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Funakoshi Y, Ichiki T, Takeda K, Tokuno T,

Iino N and Takeshita A: Critical role of cAMP-response

element-binding protein for angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy of

vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 277:18710–18717. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chintalgattu V and Katwa LC: Role of

protein kinase C-delta in angiotensin II induced cardiac fibrosis.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 386:612–616. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Müller MW, Todorov V, Krämer BK and Kurtz

A: Angiotensin II inhibits renin gene transcription via the protein

kinase C pathway. Pflugers Arch. 444:499–505. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|