Introduction

Ectopic splenic autotransplantation (ESAT) following

splenectomy or trauma may occasionally be encountered in clinical

practice; however, clinicians or general radiology practitioners

often find the diagnosis of this condition challenging (1–4). The

majority of ESAT cases have no clinical symptoms and it is

difficult to diagnose the exact incidence rate. Computed tomography

(CT), ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging are not specifically

designed for the diagnosis of ESAT, and certain patients are

misdiagnosed and undergo surgery. However, radionuclide spleen

imaging has the potential of being a more specific diagnostic

method for ESAT and may avert surgery. The present study reports a

case of ESAT, which was diagnosed using radionuclide splenic

imaging. Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants.

Case report

A 41-year-old male patient was admitted to the

General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command (Guangzhou, China)

due to upper abdominal pain persisting for 12 h. The patient had

been involved in a traffic collision and had undergone a splenic

resection 10 years prior, which were hypothesized to have been

associated with the symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 15-cm

longitudinal and transverse operational incision scar, abdominal

tenderness and rebound tenderness, with a negative Murphys

sign.

Laboratory examination

The laboratory examination results were as follows:

White blood cell count, 2.1×1010 cells/l; neutrophils,

84.6%; serum amylase, 246 U/l; serum lipase, 407 U/l;

carcinoembryonic antigen, 2.27 g/ml; α-fetoprotein, 6.17 mg/l; and

CA199, 22.47 U/ml. These results were within normal ranges,

indicating that it was unlikely that the patients symptoms were

tumor-related.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT

scanning

The CT scan showed that the patient suffered from

acute pancreatitis, severe fatty liver and small gallstones, and

there were foci in S3 and S6 of the liver and multiple

space-occupying foci in the ascending colon. The PET/CT scan showed

the following: i) Multiple soft-tissue shadows in the abdominal

cavity, peritoneum and Glisson's capsule, which were suggested to

be benign lesions, since no metabolic disorder was observed; ii) a

small area of low-density shadows near the tail of the pancreas,

which was considered to be inflammation, since the metabolic

activity was mildly increased in that area; iii) multiple shadows

of enlarged lymph nodes around the porta hepatis and pancreas, with

a mildly increased metabolic activity; iv) absence of the spleen,

since splenectomy had been performed (Fig. 1).

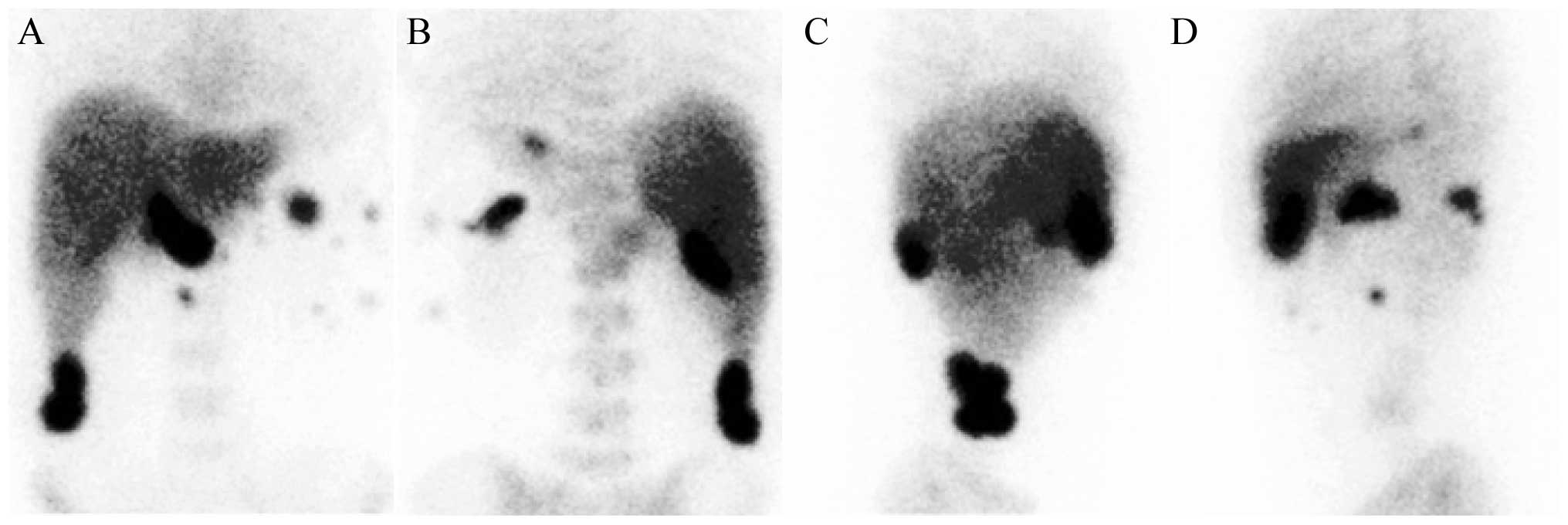

Radionuclide imaging

The spleen was absent from its normal position

(following splenectomy), but abnormal phagocytosis of multiple red

blood cells was observed in the abdomen, which was considered to be

ESAT (Fig. 2).

Clinical diagnosis

The patient was diagnosed with acute pancreatitis,

cholecystitis with gallstones, fatty liver and ESAT following

splenectomy. The patient subsequently recovered well after

receiving antipyretic analgesics and rehydration therapy..

Discussion

ESAT refers to the spontaneous transplantation of

splenic tissue following injury or splenectomy. ESAT may occur in

various sites, such as the chest, pelvic cavity or subcutaneous

tissue, but is mainly found in the abdominal cavity (5–7). In the

majority of cases, ESAT is asymptomatic and does not affect any

physiological function; therefore, intervention is usually not

required (8). In the present case,

the patient presented with acute pancreatitis and ESAT was detected

accidentally; it did, however, affect clinical diagnosis to a great

extent, as ESAT is easily misdiagnosed as a tumor. Conventional

radionuclide splenic imaging is a method specific for the diagnosis

of ESAT, and in the present case it proved to be more

diagnostically significant compared with PET/CT.

References

|

1

|

Oda J, Tachikawa N and Suda T: A solid

mass in pelvic region. Gastroenterology. 137:e9–e10. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wallace S, Herer E, Kiraly J, Valikangas E

and Rahmani R: A wandering spleen: Unusual cause of a pelvic mass.

Obstet Gynecol. 112:478–480. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fiquet-Francois C, Belouadah M, Ludot H,

et al: Wandering spleen in children: Multicenter retrospective

study. J Pediatr Surg. 45:1519–1524. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bouassida M, Sassi S, Chtourou MF, et al:

A wandering spleen presenting as a hypogastric mass: Case report.

Pan Afr Med. J11:312012.

|

|

5

|

Di Crosta I, Inserra A, Gil CP, Pisani M

and Ponticelli A: Abdominal pain and wandering spleen in young

children: The importance of an early diagnosis. J Pediatr Surg.

44:1446–1449. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dirican A, Burak I, Ara C, Unal B, Ozgor D

and Meydanli MM: Torsion of wandering spleen. Bratisl Lek Listy.

110:723–725. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tseng CA and Chou AL: Images in clinical

medicine. Pelvic spleen. N Engl J Med. 361:12912009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dillman JR and Strouse PJ: Clinical image.

The ‘wandering’ spleen. Pediatr Radiol. 40:2312010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|