Introduction

Colon diverticula are outpouchings of the mucosa and

muscularis mucosa. Diverticula develop where the colon wall is weak

(1), the negative outcomes of which

are bleeding and acute diverticulitis (2,3).

Bleeding from diverticula accounts for 20–50% of lower

gastrointestinal bleeding cases (4);

this is usually self-limiting, but is occasionally fatal for

patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and

anticoagulants (5–7). Acute diverticulitis is treated with

antibiotics (8), which can cause

complications, and surgery is required if diverticulum perforation

occurs (9). The risk of bleeding and

perforation may be reduced if the presence of diverticula is

identified in advance.

Studies on the risks of diverticula predominantly

focus on aging, genetic factors and dietary fiber. The odds ratio

of siblings with diverticula is 7.15 for monozygotic twins and 3.2

for dizygotic twins (10). Among the

cases of diverticula, 40% result from inherited factors and 60%

from environmental factors (10).

However, controversy remains over whether dietary fiber is one of

the causes (11,12). Crowe et al (11) concluded that increased dietary fiber

intake decreases the risk of diverticula, but Peery et al

(12) reported that fiber intake

does not affect the prevalence of diverticula. With regard to risk

factors, Song et al (13)

attributed aging, high-fat diets and high alcohol consumption as

factors increasing the risk of diverticula.

If laboratory data that are correlated with the

presence of diverticula were available, it would be possible to

develop strategies to decrease the risk of developing diverticula;

the present study therefore analyzed the laboratory data of

patients who underwent colonoscopy in order to determine variables

that predict the presence of diverticula.

Materials and methods

Patients

Patient records from between April 2011 and March

2014 were analyzed retrospectively. A total of 1,520 patients

underwent colonoscopy and were included in the analysis, including

758 men (mean age ± standard deviation, 68.9±10.9 years) and 762

women (68.7±10.8 years). The current study was approved by the

National Hospital Organization Shimshizu Hospital Ethics Committee

(Yotsukaido, Japan) and was not categorized as a clinical trial as

it was performed during routine clinical practice. Written informed

consent was waived since the present study was retrospective.

Patient anonymity was preserved.

Colonoscopy

A colonoscopy was performed for patients with

abdominal symptoms, anemia or positive fecal occult blood. A

colonoscopy was also performed for screening purposes. The

colonoscopy devices used were CF-Q260DL/I and PCF-Q260AL/I

(Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Blood variables

White blood cell count, platelet count, body mass

index, and levels of hemoglobin (Hb), C-reactive protein, total

protein, albumin, total bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, aspartate

aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl

transpeptidase, lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid (UA), blood urea

nitrogen, creatinine, total cholesterol, triglyceride (TG),

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol, blood glucose, HbA1c, carcinoembryonic antigen and

carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were analyzed.

Statistical analysis

A one-way analysis of variance was performed to

analyze the association between the presence of diverticula and

each variable. A χ2 test was used to determine the

correlation between the presence of diverticula and age group,

gender and UA levels ≥5.1 mg/dl. A receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed to determine the

threshold values able to predict the presence of diverticula.

Specificity and sensitivity were automatically calculated using an

ROC program in the statistical software. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate statistical significance. JMP 10.0.2 software (SAS

Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for the statistical

analysis.

Results

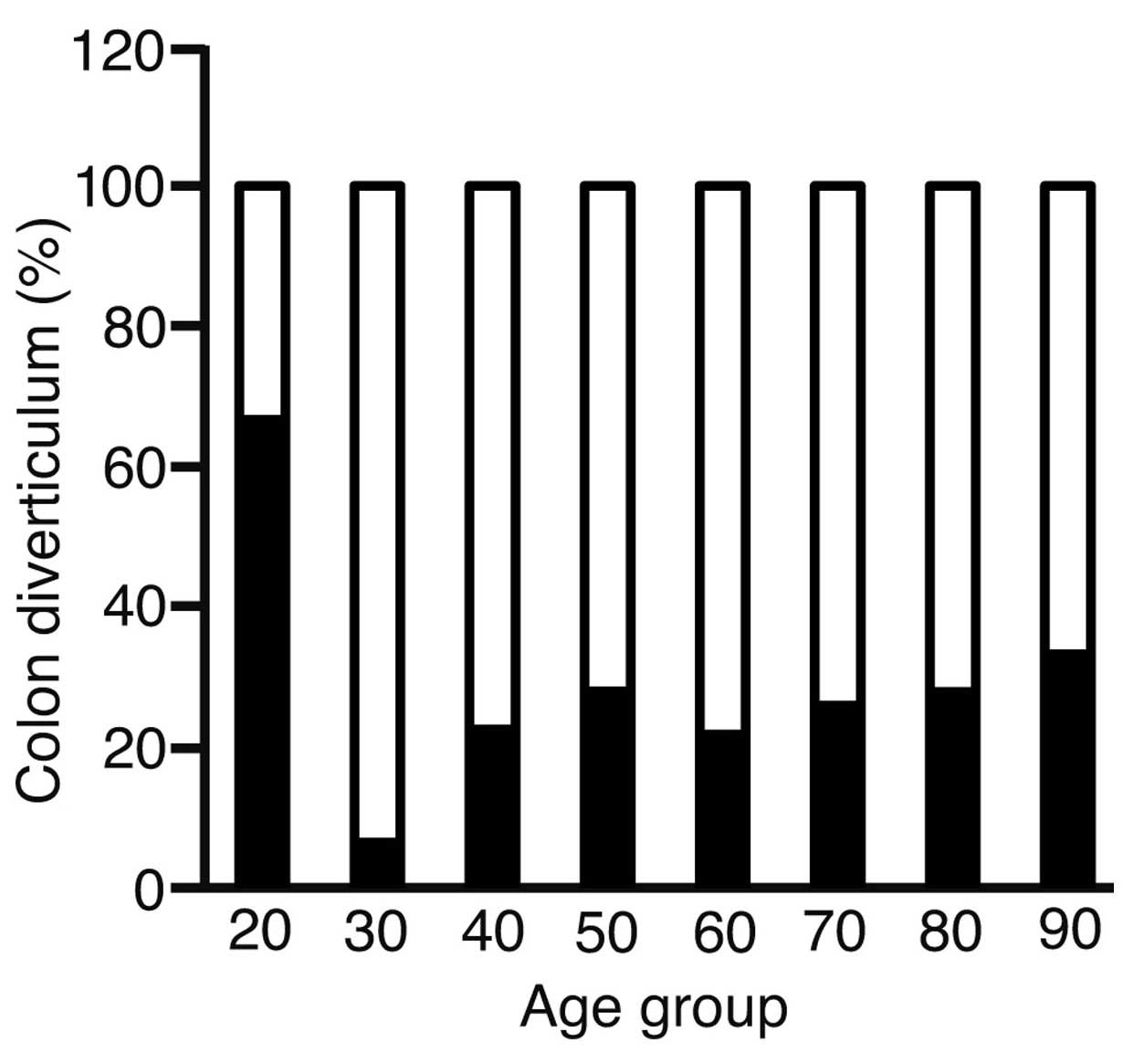

To analyze the correlation between age and the

presence of diverticula, the patients were divided into the

following age groups: Group 20 (20–29 years old, 3 patients); group

30 (30–39 years old, 31 patients); group 40 (40–49 years old, 93

patients); group 50 (50–59 years, 125 patients); group 60 (60–69

years old, 508 patients); group 70 (70–79 years old, 597 patients);

group 80 (80–89 years old; 154 patients) and group 90 (>90 years

old; 9 patients) (Fig. 1). The

incidence of diverticula increased with advancing age, but no

significant correlation was found by χ2 test

(P=0.0643).

The experimental variables were compared to

determine significant differences between patients with and without

diverticula (Table I). Hb levels

were lower in patients with diverticula compared with those without

diverticula (P=0.0027). UA and TG levels were also higher in

patients with diverticula (P=0.0066 and P=0.0136,

respectively).

| Table I.Blood variable differences in patients

with and without colon diverticula. |

Table I.

Blood variable differences in patients

with and without colon diverticula.

| Variable | Total number of

patients | Patients without

colon diverticula, n | Variable level, mean

± SD | Patients with colon

diverticula, n | Variable level, mean

± SD | P-value |

|---|

| WBC, µl | 743 | 563 | 6.06±2.06 | 180 | 6.22±2.08 | 0.3514 |

| Hb, g/dl | 742 | 63 | 12.8±0.22 | 179 | 1.24±0.20 | 0.0027 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 392 | 303 | 0.95±3.11 | 89 | 0.69±1.63 | 0.4452 |

| Plt,

104/µl | 734 | 554 | 2.23±0.73 | 180 | 2.20±0.69 | 0.6652 |

| TP, g/dl | 492 | 370 | 6.89±0.68 | 122 | 6.77±0.89 | 0.1268 |

| Alb, g/dl | 350 | 264 | 3.99±0.04 | 86 | 4.02±0.06 | 0.5985 |

| T-Bil, mg/dl | 499 | 378 | 0.76±0.42 | 121 | 0.75±0.33 | 0.9497 |

| ALP, IU/l | 255 | 196 | 2.38±1.02 | 59 | 2.23±0.59 | 0.2807 |

| AST, IU/l | 677 | 511 | 2.46±1.33 | 166 | 2.66±3.30 | 0.2617 |

| ALT, IU/l | 713 | 545 | 2.16±1.35 | 168 | 2.53±3.87 | 0.0591 |

| γ-GTP, IU/l | 290 | 225 | 0.51±2.24 | 65 | 0.45±0.56 | 0.8382 |

| LDH, IU/l | 379 | 297 | 2.06±1.04 | 82 | 1.97±0.49 | 0.4360 |

| UA, mg/d) | 282 | 213 | 5.13±1.46 | 69 | 5.66±1.28 | 0.0066 |

| BUN, mg/dl | 469 | 353 | 1.61±1.46 | 116 | 1.52±0.50 | 0.5124 |

| Cre, mg/dl | 713 | 545 | 0.84±0.39 | 168 | 0.86±0.26 | 0.6060 |

| T-Chol, mg/dl | 286 | 222 | 2.01±0.38 | 64 | 1.99±0.41 | 0.6999 |

| TG, mg/dl | 259 | 198 | 1.24±0.81 | 61 | 1.53±0.77 | 0.0136 |

| HDL, mg/dl | 197 | 145 | 5.97±1.75 | 52 | 5.68±1.59 | 0.2982 |

| LDL, mg/dl | 272 | 204 | 1.17±0.28 | 68 | 1.21±0.29 | 0.3834 |

| BG, mg/dl | 375 | 294 | 1.19±0.40 | 81 | 1.24±0.50 | 0.3211 |

| HbA1c, % | 180 | 139 | 6.17±0.94 | 41 | 6.27±1.35 | 0.5805 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 273 | 212 | 2.25±0.36 | 61 | 2.29±0.40 | 0.4734 |

| CEA, ng/ml | 208 | 167 | 1.61±7.68 | 41 | 9.86±5.61 | 0.0669 |

| CA19-9, U/ml | 205 | 165 | 0.22±0.63 | 40 | 0.66±3.20 | 0.0984 |

Table II reports the

χ2 test results comparing the prevalence of diverticula

between male and female patients. Diverticula were more frequent in

male patients than in female patients (P=0.0001). The mean ages of

the male and female patients with diverticula were 69.2±11.0 and

68.0±10.2 years, respectively.

| Table II.Association between gender and the

presence of colon diverticula. |

Table II.

Association between gender and the

presence of colon diverticula.

|

| Colon diverticula,

n |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Gender | Absent | Present | Total, n |

|---|

| Male |

543 | 219 |

762 |

| Female |

605 | 153 |

758 |

| Total | 1148 | 372 | 1520 |

Table I demonstrates

that UA levels were significantly higher in patients with

diverticula compared with those without diverticula. To confirm

these results, the patients were divided into two groups according

to UA level, as follows: Patients with UA levels ≥5.1 mg/dl and

those with UA levels <5.1 mg/dl. In the patient sample of the

current study, 5.1 mg/dl was the median UA level. The prevalence of

diverticula was compared between the two groups (Table III); this was significantly higher

in patients with UA levels ≥5.1 mg/dl than in those with UA levels

<5.1 mg/dl (P=0.0004; χ2 test). Diverticula were

markedly more frequent in patients with UA levels ≥5.1 mg/dl.

| Table III.Association between uric acid level

and the presence of colon diverticula. |

Table III.

Association between uric acid level

and the presence of colon diverticula.

|

| Colon diverticula,

n |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Uric acid

level | Absent | Present | Total, n |

|---|

| High (≥5.1

mg/dl) | 99 | 49 | 148 |

| Low (<5.1

mg/dl) | 114 | 20 | 134 |

| Total | 213 | 69 | 282 |

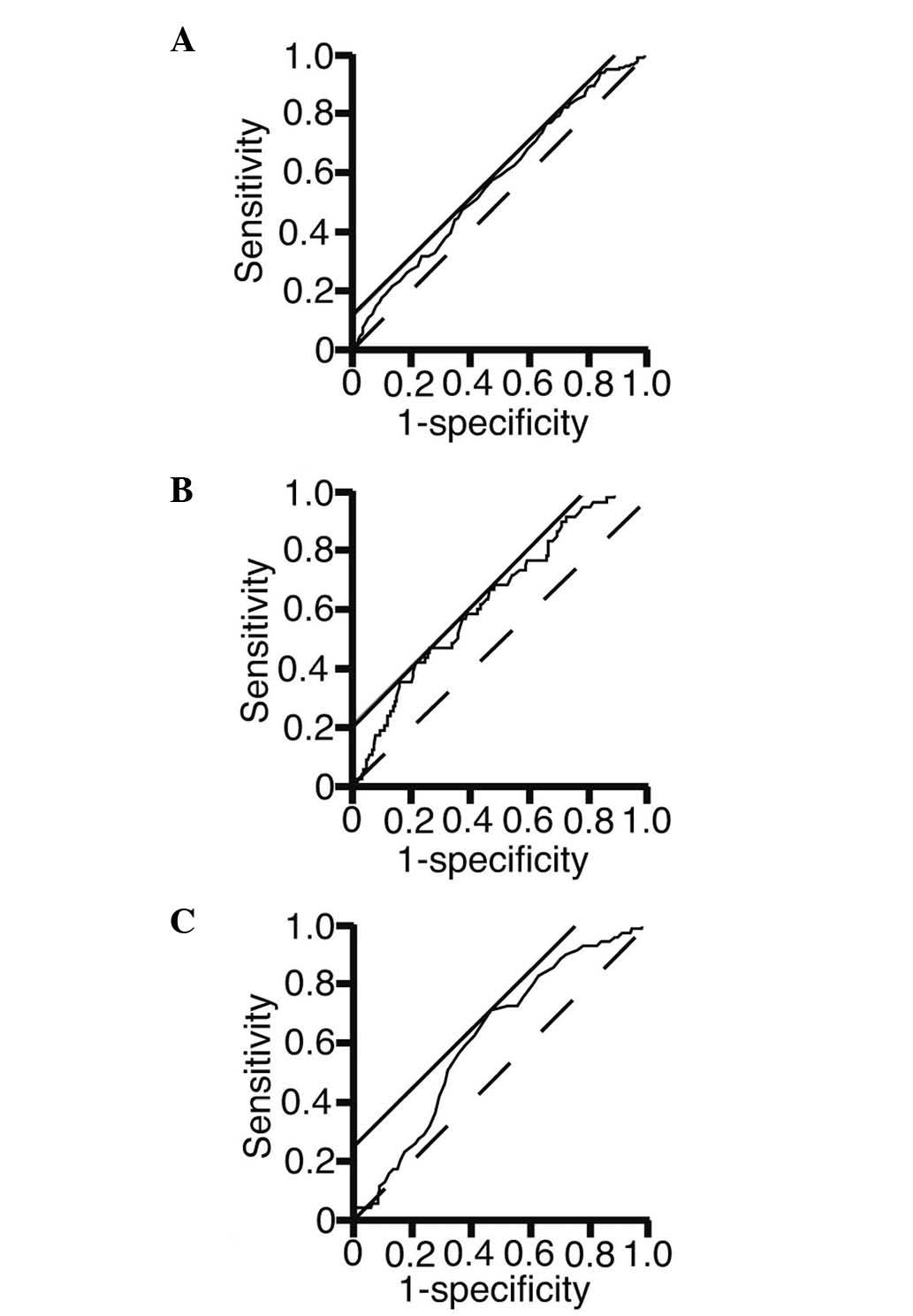

To address the possibility that the presence of

diverticula could be predicted using laboratory test variables, an

ROC analysis was performed (Fig. 2).

The area under the curve, threshold value, sensitivity and

specificity are presented in Table

IV. The threshold values of the Hb, TG and UA levels were

12,400, 146 and 5.1 mg/dl, respectively. The sensitivity of the Hb

and UA levels at the threshold values was 76.5 and 71.0%,

respectively.

| Table IV.Threshold values to predict the

presence of colon diverticula. |

Table IV.

Threshold values to predict the

presence of colon diverticula.

| Blood variable | AUC | Threshold value,

mg/dl | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % |

|---|

| Hb | 0.56926 | 12400 | 76.5 | 34.1 |

| TG | 0.63512 | 146 | 47.5 | 75.3 |

| UA | 0.62105 | 5.1 | 71.0 | 53.5 |

Discussion

The correlation between laboratory data, with the

exception of age, and the presence of diverticula has not been

previously reported. In the present study, the presence of

diverticula was significantly associated with low Hb levels, and

high TG and UA levels. A non-significant trend with increasing age

was also revealed. The prevalence of diverticula may increase with

advancing age due to structural changes in the colon wall (10,13,14). To

the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to report

an association between diverticula and low Hb, high TG and high UA

levels.

The current study revealed that the Hb levels were

lower in patients with diverticula than in those individuals

without; lower Hb levels were likely associated with the presence

of diverticula as this is a major cause of lower gastrointestinal

bleeding (15).

Higher TG levels are associated with metabolic

syndrome (16,17) and TG level decreases as metabolic

syndrome improves following lifestyle changes (18). In the present study, high TG levels

were associated with diverticula. These previous data, alongside

the data from the current study, indicate that diverticula may be

associated with metabolic syndrome. Foster et al (19) compared the prevalence of diverticula

between patients with and without ischemic heart disease and

demonstrated that diverticula occurred in 57 and 25% of patients,

respectively. This indicated an association with ischemic heart

disease, which itself has a known association with high TG levels

(20). Previous studies, together

with the present data, thus indicate that high TG levels may be

associated with diverticula.

The data in the current study clearly suggested that

the prevalence of diverticula was associated with higher UA levels;

to the best of our knowledge, the current study presents the first

report of this association. The molecular details, however, are not

known. The data on TG and UA presented in the current study may

suggest that a reduction in TG and UA levels decreases the risk of

diverticula.

Fernández et al (21) reported that predicting colonoscopic

outcomes is challenging when based on blood examination results

alone. The sensitivity of the Hb level at 12,400 mg/dl was 76.5% in

the current study, suggesting that low Hb levels may be due to

diverticulum bleeding. A notable finding was that the threshold

value of UA was 5.1 mg/dl, the same value as the median.

To conclude, low Hb levels and high TG and UA levels

are associated with the presence of diverticula. Therefore,

colonoscopy may be recommended for patients with high TG and UA

levels, in order to detect colon diverticula.

References

|

1

|

Meyers MA, Volberg F, Katzen B, Alonso D

and Abbott G: The angioarchitecture of colonic diverticula.

Significance in bleeding diverticulosis. Radiology. 108:249–261.

1973. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wilkins T, Baird C, Pearson AN and Schade

RR: Diverticular bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 80:977–983.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Humes DJ and Spiller RC: Review article:

The pathogenesis and management of acute colonic diverticulitis.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 39:359–370. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Marion Y, Lebreton G, Le Pennec V, Hourna

E, Viennot S and Alves A: The management of lower gastrointestinal

bleeding. J Visc Surg. 151:191–201. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jansen A, Harenberg S, Grenda U and Elsing

C: Risk factors for colonic diverticular bleeding: A Westernized

community based hospital study. World J Gastroenterol. 15:457–461.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tsuruoka N, Iwakiri R, Hara M, Shirahama

N, Sakata Y, Miyahara K, Eguchi Y, Shimoda R, Ogata S, Tsunada S,

et al: NSAIDs are a significant risk factor for colonic

diverticular hemorrhage in elder patients: Evaluation by a

case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 26:1047–1052. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Rimm EB, Wing

AL and Willett WC: Use of acetaminophen and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs: A prospective study and the risk of

symptomatic diverticular disease in men. Arch Fam Med. 7:255–260.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Weizman AV and Nguyen GC: Diverticular

disease: Epidemiology and management. Can J Gastroenterol.

25:385–389. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Afshar S and Kurer MA: Laparoscopic

peritoneal lavage for perforated sigmoid diverticulitis. Colorectal

Dis. 14:135–142. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Granlund J, Svensson T, Olén O, Hjern F,

Pedersen NL, Magnusson PK and Schmidt PT: The genetic influence on

diverticular disease - a twin study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

35:1103–1107. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Crowe FL, Appleby PN, Allen NE and Key TJ:

Diet and risk of diverticular disease in Oxford cohort of European

Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC):

Prospective study of British vegetarians and non-vegetarians. BMJ.

343:d41312011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Peery AF, Barrett PR, Park D, Rogers AJ,

Galanko JA, Martin CF and Sandler RS: A high-fiber diet does not

protect against asymptomatic diverticulosis. Gastroenterology.

142:266–272.e1. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Song JH, Kim YS, Lee JH, Ok KS, Ryu SH,

Lee JH and Moon JS: Clinical characteristics of colonic

diverticulosis in Korea: A prospective study. Korean J Intern Med.

25:140–146. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Heise CP: Epidemiology and pathogenesis of

diverticular disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 12:1309–1311. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Wilkins T, Khan N, Nabh A and Schade RR:

Diagnosis and management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am Fam

Physician. 85:469–476. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Tomizawa M, Kawanabe Y, Shinozaki F, Sato

S, Motoyoshi Y, Sugiyama T, Yamamoto S and Sueishi M: Elevated

levels of alanine transaminase and triglycerides within normal

limits are associated with fatty liver. Exp Ther Med. 8:759–762.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tomizawa M, Kawanabe Y, Shinozaki F, Sato

S, Motoyoshi Y, Sugiyama T, Yamamoto S and Sueishi M: Triglyceride

is strongly associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease among

markers of hyperlipidemia and diabetes. Biomed Rep. 2:633–636.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yamaoka K and Tango T: Effects of

lifestyle modification on metabolic syndrome: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 10:1382012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Foster KJ, Holdstock G, Whorwell PJ, Guyer

P and Wright R: Prevalence of diverticular disease of the colon in

patients with ischaemic heart disease. Gut. 19:1054–1056. 1978.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lisak M, Demarin V, Trkanjec Z and

Basić-Kes V: Hypertriglyceridemia as a possible independent risk

factor for stroke. Acta Clin Croat. 52:458–463. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fernández E, Linares A, Alonso JL,

Sotorrio NG, de la Vega J, Artimez ML, Giganto F, Rodríguez M and

Rodrigo L: Colonoscopic findings in patients with lower

gastrointestinal bleeding send to a hospital for their study. Value

of clinical data in predicting normal or pathological findings. Rev

Esp Enferm Dig. 88:16–25. 1996.(In Spanish). PubMed/NCBI

|