Introduction

Immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) is a type of

immune complex-mediated glomerulonephritis that is pathologically

characterized by the deposition of IgA immune complexes in the

mesangium of the kidney (1). IgAN is

the most common form of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide,

particularly in China (2). In

addition, 15–20% of patients with IgAN develop end-stage renal

failure (ESRD) within 10 years, and 30–40% within 20 years

(3–5). Proteinuria is regarded as the most

severe risk factor for unfavorable renal prognosis, and its

reduction is an important therapeutic goal in clinical practice

(6).

Optimized supportive therapy is the key strategy for

patients with IgAN who are at risk of progression, with

renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) inhibitors being the most common

treatment. However, the optimal immunosuppressive treatment

strategy for patients with IgAN suffering from moderate to severe

proteinuria remains uncertain. According to the guidelines outlined

by the clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis (7), patients with IgAN who suffer from

persistent proteinuria of >1 g/day following 6 months of

treatment with RAS inhibitors are recommended to undergo

corticosteroid therapy. There is an ongoing debate over the

efficacy and safety of immunosuppressive agents other than

glucocorticoid monotherapy in patients with IgAN who present with

moderate to severe proteinuria; specifically, the use of relatively

novel agents, including leflunomide (LET) and mycophenolate mofetil

(MMF).

Increasing attention has been paid to the role of

immunosuppressive agents in the treatment of patients with IgAN.

The present report aimed to generate a meta-analysis from the most

up-to-date studies regarding the safety and efficacy of various

immunosuppressive therapeutic strategies for the treatment of

patients with IgAN, in order to provide comprehensive current

information to nephrologists to aid decision making. China has the

largest population worldwide, and has a high incidence of IgAN. In

order to exclude interferences that may be due to the ethnicity of

patients, the present meta-analysis was performed using studies

involving Chinese patients exclusively.

Methods

Information sources and search

strategy

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that

assessed the efficacy and safety of various immunosuppressive

agents in the treatment of Chinese patients with IgAN between 1990

and September 2013 were included in the present meta-analysis.

Numerous databases were searched for eligible RCTs, including:

PubMed, Excerpta Medica database, the Cochrane Library, Chinese

National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang, Weipu, Chinese

Biomedical Literature Database and Qinghuatongfang. The following

medical terms and phrases were used for the search: ‘Immunoglobulin

A nephropathy’; ‘IgA nephropathy’; ‘Berger disease’;

‘glomerulonephritis’; ‘RCT’; ‘controlled clinical trial’ and

‘immunosuppressive therapy’. Only RCTs published in either English

or Chinese were considered to be eligible. The title and abstract

of the search results were analyzed by two independent

investigators. According to the inclusion criteria, reference lists

from all identified articles were also searched.

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used in the

present meta-analysis: (i) Prospective RCTs comparing various

immunosuppressive agents; (ii) the selected patients with IgAN were

Chinese, whether adults or children; (iii) diagnosis of IgAN was

performed via renal biopsy; and (iv) the study was published in

English or Chinese.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they: (i) Assessed

secondary types of IgAN or patients who were not Chinese; (ii) were

designed without randomization, such as retrospective studies and

descriptive studies; (iii) included the use of traditional Chinese

medicine, with its unknown additional effects on immunosuppressive

agents and uncertain doses of active components; (iv) only assessed

corticosteroids; or (v) failed to exclude patients with other

systemic diseases, such as lupus, Henoch-Schonlein purpura and

rheumatoid arthritis.

Study selection

All of the studies included in the present

meta-analysis were independently assessed by two reviewers, in

accordance with the set criteria, through retrieved abstracts and,

if necessary the full texts. Disagreements were resolved in

consultation with a third reviewer until a consensus was

reached.

Data extraction

Data were independently extracted from each study by

two reviewers using a predesigned review form (Microsoft Office

Excel 2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA); disagreements

were resolved in discussion with a third reviewer until a consensus

was reached.

The review form included the following data: First

author and unit of each study; year of publication; country of

publication; journal; patient characteristics, including age,

gender and ethnicity; interventions, including type of

immunosuppressive agents, dose and usage; and the methodology of

the RCTs. Baseline, final proteinuria, serum creatinine and serum

albumin levels, and the type of outcome (complete remission,

partial remission and total effective rate) were recorded. In

addition, the presence of side effects, including: Elevated levels

of liver enzymes; hypertension; diabetes; glaucoma; cataracts;

leukocytopenia and infection, were recorded.

Assessments of methodological

quality

The respective qualities of the RCTs were

independently assessed by two authors, using the scoring system

developed by Jadad et al (8).

The quality scoring system was as follows: (i) Generation of random

sequences (2=appropriate, computer generated random numbers or

similar methods; 1=unknown, randomized trials but did not describe

the method of random distribution; 0=inappropriate, adopted the

method of alternate distribution such as single and double); (ii)

randomization concealment (2=appropriate, clinicians and patients

matched by unpredictable assigned sequence method; 1=unknown, only

stating the use of a random number table or other random allocation

scheme; 0=description not clear); (iii) blinding method

(2=appropriate, using the identical placebo or similar methods;

1=not clear, statement for blinding method, but no description

available; 0=inappropriate, did not adopt the method of double

blinding, or inappropriate blinding such as tablets and

injections); (iv) withdrawal (1=described the withdrawal or exit

and indicated the reasons; 0=did not describe the withdrawal or

exit or the reasons thereof).

Data analysis and statistical

methods

Statistical analyses were performed using Review

Manager software (version 5.0.2; The Cochrane Collaboration,

Oxford, UK). Two-sided P-values were obtained via the χ2

test and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference. Dichotomous outcome data were analyzed

using the odds ratio, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and the

standardized mean difference (SMD). 95% CI was used as a summary

estimator for continuous outcomes. The heterogeneity of the trial

results was investigated visually by examination of the plots and

statistically via the heterogeneity I2 values. In order

to reveal possible publication bias, funnel plots of study size vs.

effect size were visually assessed for the total clinical remission

rate.

Results

Study characteristics

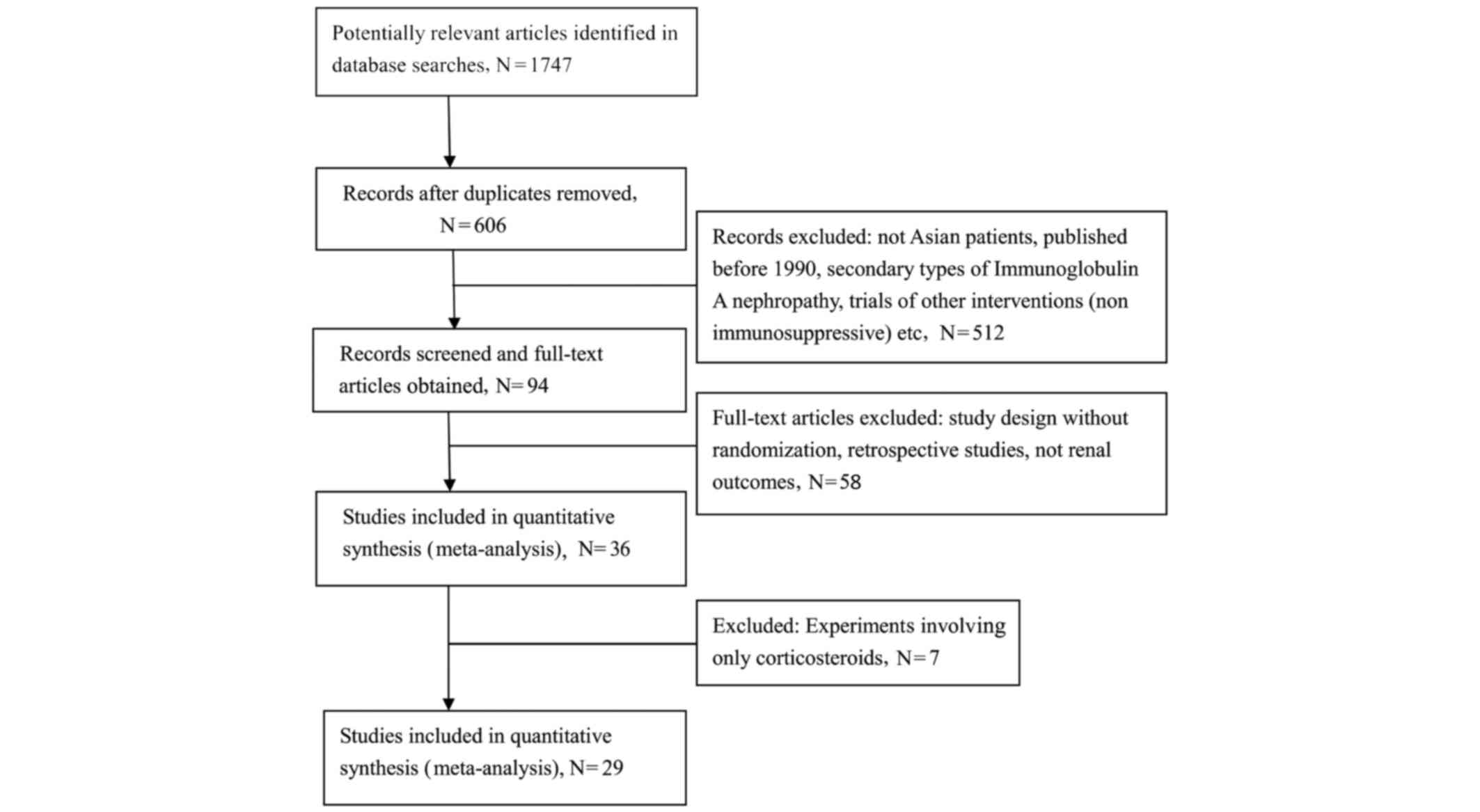

The combined search identified 1,747 articles, of

which 1,653 were excluded during the initial review. The main

reasons for the exclusion of eligible RCTs were: Non-randomization,

evaluation of other interventions (e.g. non-immunosuppressive

agents), and a lack of renal outcomes of interest. Furthermore,

animal and basic research studies were excluded, in addition to a

number of review articles on the topic. The full-text versions of

the remaining 94 articles were analyzed and a further 64 articles

were excluded for similar reasons. Overall, 29 studies (9–37),

including 1,466 patients, were included in the present

meta-analysis (Fig. 1). The

following comparisons were analyzed: MMF (or plus steroid) vs.

steroid therapy alone (n=6); azathioprine (AZA) (or plus steroid)

vs. steroid (n=5); LET (or plus steroid) vs. CTX (or plus steroid)

(n=4); CTX (or plus steroid) vs. steroid (n=2). In 13 studies, LET

was involved in the comparison. The characteristics of the included

RCTs are shown in Table I.

| Table I.Characteristics of the included

trials. |

Table I.

Characteristics of the included

trials.

| Study

(reference) | Number of

patients | Mean age (years) | Length (months) | Baseline proteinuria

(g/day) | Initial dose of

immunosuppressive agents (per day) | Quality grade |

|---|

| AZA (or plus steroid)

vs. steroid |

| Huang S

(9) | 36 | 30.8/30.8 | 9 |

1.78±1.11/1.82±1.23 | 2 mg/kg AZA | 3 |

| Kuang B

(10) | 64 |

18.0–68.0a | 6 |

0.39±0.09/0.38±0.09 | 2 mg/kg AZA | 1 |

| Li YN

(11) | 42 |

18.0–65.0a | 12 |

1.41±1.29/1.32±0.91 | 1.5 mg/kg AZA | 3 |

| Ma FL

(12) | 80 | 37.1/37.5 | NC |

1.80±1.17/1.83±1.52 | 2 mg/kg AZA | 2 |

| Xu H

(13) | 70 | 38.4/35.2 | 18 |

38.42±12.80/35.26±13.27 | 2 mg/kg AZA | 4 |

| MMF (or plus steroid)

vs. steroid |

| Tang SC

(18) | 40 | 42.1/43.3 | 8 |

1.80±0.21/1.87±0.28 | 2 g (weight, ≥60kg)

or 1.5 g (weight, <60kg) MMF | 3 |

| Chen XM

(14) | 62 | 28.0/29.0 | 24 |

3.20±1.70/2.90±1.50 | 1.0 g (weight.

<50kg) or 1.5 g (weight, >50kg) MMF | 2 |

| Chen XSh

(15) | 39 | 42.7/38.6 | 12 | NC | 1.5 g MMF | 3 |

| Guo QY

(16) | 34 | 8.7/9.4 | 12 |

0.97±0.34/1.13±0.23 | 800–1000

mg/m2 MMF | 2 |

| Huang Z

(17) | 38 | 34.0/32.0 | 2 |

6.71±5.53/5.89±4.90 | 0.5–2 gMMF | 2 |

| Wang WM

(19) | 40 | 40.0/39.4 | 12 |

1.75±1.60/1.51±0.92 | 1.0–1.5 g MMF

(weight, <50kg is 1.0g) | 3 |

| LET (or plus

steroid) vs. steroid |

| Lou TQ

(25) | 55 | 33.0/33.0 | 6 |

1.30±0.70/1.60±0.80 | 60 mg LET | 4 |

| Yang FY

(30) | 82 | 36.6/38.2 | 6 |

2.60±1.40/2.50±1.20 | 50 mg LET | 4 |

| Hu RH

(22) | 45 | 42.7/42.7 | 9 |

2.16±0.64/2.08±0.73 | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| Zhang Y

(32) | 42 | 16–68a | 6 | 2.85±0.80/NC | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| Wang L

(29) | 36 | 36.3/34.2 | 6 |

2.38±1.31/2.42±1.28 | 50 mg LET | 2 |

| Fu Q

(21) | 37 | 32.6/36.5 | 1 |

2.56±0.90/2.48±0.82 | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| Li T

(24) | 60 | 36.4/37.7 | 6 |

2.40±1.30/2.50±1.40 | 50 mg LET | 2 |

| Cao LO

(20) | 36 | 40.0/38.0 | 6 |

2.4(1.4–4.0)/2.6(1.7–3.1) | 40 mg LET | 3 |

| Huang

YX (23) | 62 | 43.5/43.5 | 6 |

2.30±1.30/2.20±1.20 | 40 mg LET | 4 |

| Pu L

(26) | 60 | 36.2/37.4 | 6 |

2.10±0.94/2.08±1.03 | 20 mg LET | 3 |

| Zhang

LW (31) | 30 | 43.5/42.8 | 6 |

2.43±1.32/2.24±1.14 | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| Sun MD

(28) | 36 | 37.0/37.0 | 3 | 2.68

±0.68/2.66±0.69 | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| Shen P

(27) | 42 | 32.5/31.4 | 6 |

3.16±1.42/3.08±1.52 | 50 mg LET | 3 |

| CTX (or plus

steroid) vs. steroid |

| Wang WM

(19) | 40 | 39.5/39.4 | 12 |

1.74±1.06/1.51±0.92 | 0.5–0.75

g/m2 CTX | 3 |

| Liu Y

(33) | 32 | NC | 12 |

1.55±0.44/1.38±0.62 | 8–12 mg/kg CTX | 3 |

| LET (or plus

steroid) vs. CTX (or plus steroid) |

| Guo M

(34) | 60 | NC | 28 |

5.12±1.08/5.14±1.34 | 50 mg LET; 8–12

mg/kg CTX | 3 |

| Zhong

ShH (37) | 56 | NC | 7 |

5.16±1.32/5.10±1.07 | 50 mg LET; 8–12

mg/kg CTX | 3 |

| Zhang

HF (36) | 40 | 43.7/43.7 | 4 | NC | 50 mg LET; 8–12

mg/kg CTX | 4 |

| Sun ZhX

(35) | 70 | 35.7/35.7 | 12 |

2.61±1.38/2.54±1.28 | 50 mg LET; 0.75

g/m2 CTX | 3 |

Effects of interventions

AZA (or plus steroid) vs. steroid

Five RCTs (9–13) involving 292 patients compared the

administration of AZA (or plus steroids) with steroid therapy. AZA

(2–5 mg/kg/day) was administered for 6–24 months. Prednisolone

(0.8–1.0 mg/kg/day) was administered for 4–8 weeks and subsequently

tapered off within one year (9–13).

Patients receiving AZA demonstrated significantly increased

complete response (CR)/partial response (CR) proteinuria remission

rates [CR/PR; relative risk (RR), 3.43; 95% confidence interval

(CI), 1.92–6.12, P<0.0001] (Fig.

2), as compared with the steroid therapy alone.

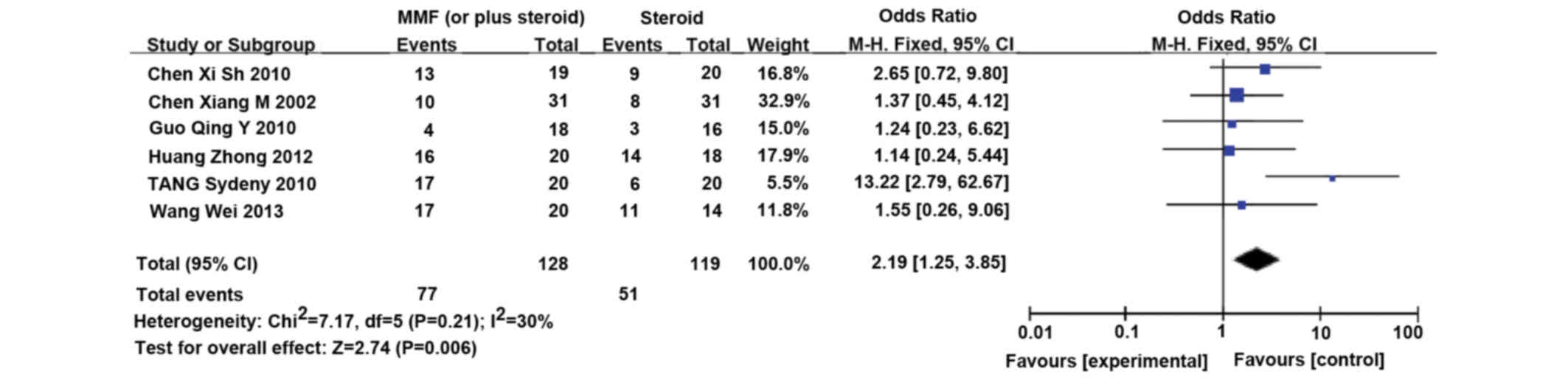

MMF (or plus steroid) vs. steroid

Six RCTs (14–19)

involving 253 patients compared MMF (or plus steroid) with steroid

therapy alone. MMF (1.0–2.0 g/day) was orally administered for 3–6

months, and gradually tapered thereafter. The immunosuppressive

treatment lasted for <12 months (14–19).

Patients receiving MMF demonstrated significantly increased CR/PR

proteinuria remission rates (CR/PR; RR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.25–3.85,

P=0.006) (Fig. 3), as compared with

the steroid therapy alone.

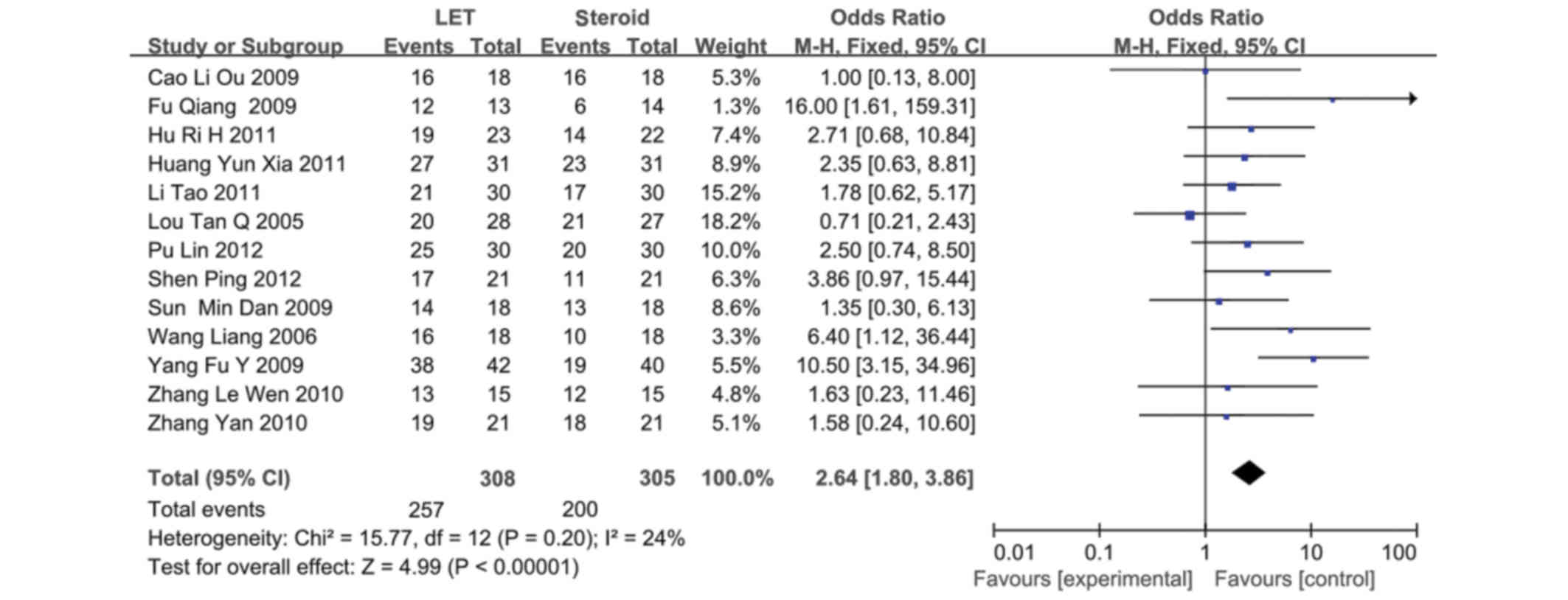

LET (or plus steroid) vs. steroid

A total of 13 RCTs (20–32)

involving 623 patients compared LET (or plus steroid) with steroid

therapy alone. LET (50 mg/day) was orally administered for 3 days,

reduced to 20–30 mg/day for 3 months, and subsequently tapered

(20–32). LET demonstrated a marked advantage on

CR/PR proteinuria remission, as compared with the steroid therapy

(CR/PR; RR, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.80–3.86; P<0.00001) (Fig. 4).

CTX (or plus steroid) vs. steroid

Two RCTs (19,33)

involving 72 patients compared CTX (or plus steroid) treatment with

steroid therapy alone. CTX (0.5–0.75 g/m2) was

intravenously administered in monthly pulses for six months,

followed by quarterly pulses for the next six months. The

immunosuppressive therapy lasted for 12 months in total (19–33).

Patients receiving CTX (or plus steroid) demonstrated markedly

increased reductions in urinary protein excretion levels by the end

of treatment, as compared with patients treated with steroid

therapy exclusively (SMD, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.41–1.41; P=0.0004)

(Fig. 5).

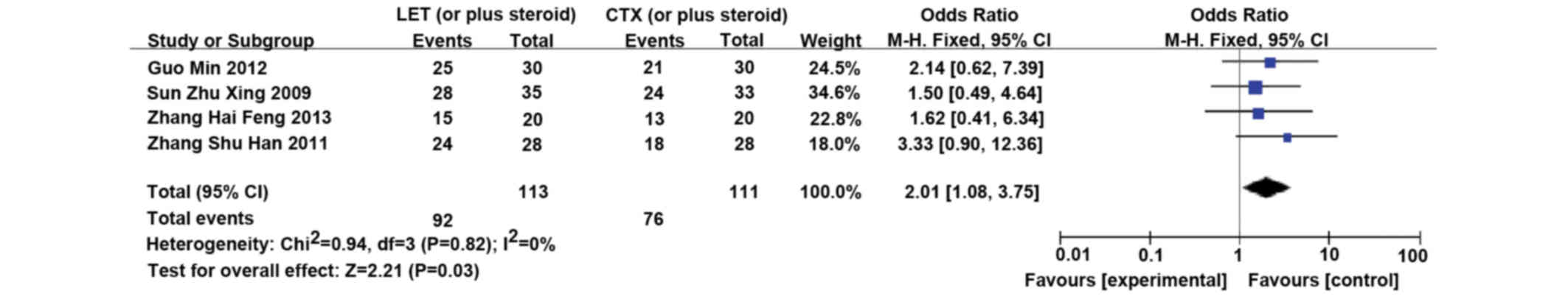

LET (or plus steroid) vs. CTX (or plus

steroid)

Four RCTs (34–37)

involving 226 patients compared LET (or plus steroid) with CTX (or

plus steroid). LET (50 mg/day) was orally administered for 3 days,

tapered, and subsequently reduced to 20 mg/day for 3 months

(34–37). LET was significantly more effective

in inducing remission, as compared with CTX (CR/PR; RR, 2.01; 95%

CI, 1.08–3.75; P=0.03) (Fig. 6).

Side effects

Although it is challenging to statistically analyze

the side effects in a single comparison, the major side effects for

each agent were recorded. A total of 143 patients were treated with

AZA, and adverse events were reported in 79 patients, including:

Myelosuppression (n=5; 6.3%), liver dysfunction (n=6; 7.6%), and

digestive symptoms (n=8; 0.12%). Infection was the most frequent

side effect of AZA (14/79, 17.7%). A total of 16 patients (14.8%)

treated with MMF demonstrated digestive symptoms; whereas a further

4 patients (3.7%) exhibited elevated liver enzymes. A total of

13/267 patients (4.7%) treated with LET demonstrated elevated liver

enzymes, and a further 10 patients (3.7%) exhibited digestive

symptoms.

No obvious nephrotoxicity directly related to the

administration of immunosuppressive agents was demonstrated. In the

‘LET (or plus steroid) vs. CTX (or plus steroid)’ comparison, 9 and

13 patients treated with LET and CTX, respectively, demonstrated

liver dysfunction; whereas 1 and 3 patients receiving CTX and LET,

respectively, demonstrated digestive symptoms. Furthermore,

leukocytopenia was detected in 6 patients treated with CTX, whereas

5 individuals treated with LET demonstrated alopecia.

Publication bias and sensitivity

analysis

Publication bias was examined using funnel plots,

which did not show any significant visual asymmetry (Fig. 7). Furthermore, in order to assess the

robustness of the meta-analysis results, a sensitivity analysis

focusing on the patients and the quality of the RCTs was conducted.

Analysis was performed by excluding low quality RCTs. As outlined

in Table I, the quality scores of

all included RCTs were not high; therefore, any RCTs scoring less

than 3 points were excluded (n=7). This sensitivity analysis did

not substantially change the results of the comparisons.

Discussion

IgAN, which was initially identified by Berger and

Hinglais in 1968 (1), is the most

common form of primary glomerular nephritis in Asia. The

immunological mechanisms associated with the development and

progression of IgAN suggest that immunosuppressive therapies may

have a beneficial role in the treatment of IgAN and associated

proteinuria. Although previous studies have demonstrated that the

administration of glucocorticoids may reduce the risk of ESRD in

patients with IgAN (38,39), the optimal immunosuppressive

treatment strategy for patients with IgAN who suffer with moderate

to severe proteinuria remains uncertain. In the present

meta-analysis, a comprehensive literature search with limited

restrictions in publication language was performed in order to

compare the efficacy and safety of immunosuppressive agents such as

CTX, LET, MMF and AZA, which are widely used in the treatment of

Chinese patients with IgAN.

A total of 1,466 patients from 29 studies (9–37) were

included in the present meta-analysis. As too few studies reported

long-term outcomes, the present meta-analysis only reviewed

short-term parameters in order to evaluate the efficacy of the

respective treatments, including the final urinary protein

excretion and therapeutic remission (complete or partial) of the

participants. The most frequently used definition for ‘partial

remission’ of proteinuria was 0.3–2.0 g/day or a decrease of 50%.

Complete remission of proteinuria was defined as <0.3 g/day and

serum albumin >35 g/l with normal renal function. However, these

definitions may be heterogeneous.

Notably, the patients demonstrated an improved

treatment response to AZA administration, as compared with steroid

treatment alone (RR, 3.43; 95% CI; 1.92–6.12; P<0.0001). In

addition, following treatment with MMF therapy, the Chinese

patients with IgAN demonstrated significantly increased CR/PR

remission rates (CR/PR; RR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.25–3.85; P=0.006), as

compared with the administration of steroid alone. In the analysis

of ‘LET (or plus steroid) versus steroid’, the administration of

LET demonstrated an improved response, as compared with steroid

treatment alone. Tolerable side effects were demonstrated in

patients administered AZA, MMF and LET. Only two studies involving

72 patients compared CTX plus steroid and steroid therapy alone;

therefore further high quality RCTs are required in the future to

determine the effects of CTX. Four studies were included in the

analysis of ‘CTX (or plus steroid) versus LET (or plus steroid)’;

LET administration was significantly effective in inducing

remission of proteinuria and was associated with a lower incidence

of adverse reactions, as compared with CTX.

Some findings of the present study were consistent

with the results of previous studies in patients of various

ethnicities. Several RCTs have demonstrated that, when combined

with steroid treatment, CTX was able to reduce urinary protein

levels and conserve kidney function in patients with IgAN (19,33).

Yoshikawa et al (40)

demonstrated that the administration of AZA plus steroid therapy

resulted in the increased complete remission of proteinuria in 80

juvenile patients newly diagnosed with IgAN. However, the efficacy

of MMF administration in patients with IgAN differs among

ethnicities. In a Belgian study that assessed MMF vs. placebo in 34

patients, Maes et al (41)

demonstrated an average proteinuria level of 1.8 g/day; whereas no

differences in the reduction of proteinuria or preservation of

glomerular filtration rate were demonstrated. Similarly, in a North

American study, Frisch et al (42) demonstrated that a 1-year regimen of

MMF vs. placebo in patients with IgAN with an initial average

proteinuria level of 2.7 g/day provided no benefits over 24 months.

The efficacy and safety of LET in the treatment of patients with

IgAN in other ethnicities is unknown, and no relevant RCTs were

found. Due to the heterogeneity of the results from previous

studies, the optimal immunosuppressive therapeutic strategy for the

treatment of patients with IgAN remains controversial. The reasons

for this heterogeneity require further investigation, however, the

following may be considered contributing factors: Ethnicity

differences; variations in the levels of therapeutic agent

achieved; limited number of trials and small sample sizes; and

suboptimal methodological quality. The results of the present

meta-analysis demonstrated the potential of immunosuppressive

agents, including AZA, CTX, MMF and LET, as a short-term (6–12

months) therapeutic strategy for the treatment of proteinuria in

patients with IgAN.

The present meta-analysis had various strengths.

Firstly, in an attempt to minimize bias, rigorous methods were used

and only randomized trials were included. Secondly, as compared

with previous meta-analyses, a greater number of studies were

included and attempts were made to tabulate the occurrence of

adverse events. It remains premature to recommend the routine use

of AZA, CTX, MMF and LET immunosuppressive agents as treatment for

patients with IgAN, for various reasons. The data analyzed in the

present meta-analysis were obtained from short-term studies with

small sample sizes, which were generally conducted in a single

center. Furthermore, as the analysis was conducted on pooled data

from published papers, individual patient and original data were

not available, which prevented a more detailed analysis from being

completed, which may have yielded more comprehensive results.

In conclusion, based on the Chinese patients and

short duration RCTs examined, the administration of AZA, MMF, LET

and CTX, demonstrated superior potency in inducing the remission of

proteinuria in patients with IgAN with tolerable adverse effects,

as compared with steroid treatment. In addition, as compared with

CTX, LET administration demonstrated a lower incidence of adverse

reactions. Furthermore, the results of the present meta-analysis

support the need for a large, high-quality multicenter trial in

order to ascertain whether immunosuppressive treatments may be

effective in a broad population of patients with high-risk IgAN,

specifically to determine their effects in kidney failure.

Acknowledgements

The present meta-analysis was supported by the Jiang

Xi Natural Science Foundation Program (grant no. 20122BAB215004)

and the National Natural Science Foundation for Innovative Research

Groups of China (grant no. 81260120). The authors of the present

study acknowledge Professor Haiping Mao, Dr Li Fan and Dr Rong R of

the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University for their

support in data analyses.

Note added at revision of article

Subsequently to the publication of the above

article, an interested reader drew to our attention that the

article described the use of the drug acetazolamide for IgA

nephropathy on a number of occasions in the text, whereas the

references refer to the drug azathioprine. The authors confirmed

that, owing to an oversight on their part, all the references to

“acetazolamide” in their paper (abbreviated as ‘AZA’) should have

been written as “azathioprine”. Given the nature of this error,

note that the drug name for ‘AZA’ has been corrected in the article

itself, and this is a revised version of the original article.

References

|

1

|

Berger J and Hinglais N: Intercapillary

deposits of IgA-IgG. J Urol Nephrol (Paris). 74:694–695. 1968.(In

French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bartosik LP, Lajoie G, Sugar L and Cattran

DC: Predicting progression in IgA nephropathy. Am J Kidney Dis.

38:728–735. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

D Amico G: Natural history of idiopathic

IgA nephropathy: Role of clinical and histological prognostic

factors. Am J Kidney Dis. 36:227–237. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Alamartine E, Sabatier JC, Guerin C,

Berliet JM and Berthoux F: Prognostic factors in mesangial IgA

glomerulonephritis: An extensive study with univariate and

multivariate analyses. Am J Kidney Dis. 18:12–19. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bogenschütz O, Bohle A, Batz C, Wehrmann

M, Pressler H, Kendziorra H and Gärtner HV: IgA nephritis: On the

importance of morphological and clinical parameters in the

long-term prognosis of 239 patients. Am J Nephrol. 10:137–147.

1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Reich HN, Troyanov S, Scholey JW and

Cattran DC: Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry: Remission of

proteinuria improves prognosis in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 18:3177–3183. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Beck L, Bomback AS, Choi MJ, Holzman LB,

Langford C, Mariani LH, Somers MJ, Trachtman H and Waldman M: KDOQI

US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for

glomerulonephritis. Am J Kidney Dis. 62:403–441. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson

C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ and McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of

reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary?

Control Clin Trials. 17:1–12. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Huang S: Clinical observation of

Benazepril combined with azathioprine on IgA nephropathy. Guo Ji Yi

Yao Wei Sheng. 20:53–55. 2009.

|

|

10

|

Kuang B: Clinical observation of

Benazepril combined with azathioprine on IgA nephropathy. ZhongGuo

Xian Dai Yi Sheng. 19:6–7. 2010.

|

|

11

|

Li YN: Curative effect analysis of

Benazepril combined with azathioprine on IgA nephropathy along with

the amount of proteinuria. Hua Bei Mei Tan Yi Xue Yuan XueBao.

4:471–472. 2011.

|

|

12

|

Ma FL: Clinical research oil azathioprine

combined with benazepril treating IgA nephropathy. Xian Dai Zhen

Duan Yu Zhi Liao. 6:653–654. 2012.

|

|

13

|

Xu H: Azathioprine and prednisone,

valsartan Clinical observation on treatment of IgA nephropathy. Zhe

Jiang Yi Xue. 3:227–229. 2013.

|

|

14

|

Chen XM, Chen P, Cai G, Wu J, Cui Y, Zhang

Y, Liu S and Tang L: A randomized control trial of mycophenolate

mofeil treatment in severe IgA nephropathy. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi.

82:796–801. 2002.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Chen XSh: Clinic Effect of Mycophenolate

Mofetil combined Valsartan on IgA Nephropathy. Zhong Guo Yi Yao Zhi

Nan. 20:53–54. 2010.

|

|

16

|

Guo QY: Efficacy of pediatric IgA

nephropathy mycophenolate mofetil combined hormone therapy. Guang

Dong Yi Xue. 7:902–903. 2010.

|

|

17

|

Huang Zh: Efficacy of focal proliferative

sclerosing 38 cases of patients with IgA nephropathy. He Nan Yi Xue

Yan Jiu. 4:437–439. 2012.

|

|

18

|

Tang SC, Tang AW, Wong SS, Leung JC, Ho YW

and Lai KN: Long-term study of mycophenolate mofetil treatment in

IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 77:543–549. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang WM: Clinical study on treatment of

IgA nephropathy with renal insufficiency by corticosteroid,

corticosteroid combined with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroid

combined with mycophenolate mofetil. Shang Hai Jiao Tong Da Xue Xue

Bao. 2:162–167, 173. 2013.

|

|

20

|

Cao LO: Leflunomide in combination with

medium/low dose of prednisolone in treatment of progressive IgA

nephropathy. Shanghai Yi Xue. 9:791–795. 2009.

|

|

21

|

Fu Q: Effects of leflunomide combined with

hormone therapy for lg a nephropathy. Shan Xi Yi Xue Za Zhi.

3:351–353. 2009.

|

|

22

|

Hu RH: IgA nephropathy leflunomide

combined with hormone therapy. J Clinical Internal Medicine.

12:837–839. 2011.

|

|

23

|

Huang YX: Leflunomide combined small dose

glucocorticoid treatment of progressive IgA nephropathy Efficacy.

Chinese Journal of Primary Medicine and Pharmacy. 18:1965–1966.

2011.

|

|

24

|

Li T: Study on effect of leflunomide

combined with glucocorticoid in treatment of progressive IgA

nephropathy. Modern J Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western

Medicine. 1:13–15. 2011.

|

|

25

|

Lou TQ: Controlled trial of leflunomide in

the treatment of immunoglobulin a nephropathy. Journal of Sun

Yat-sem University (Medical Sciences). 5:570–572. 2005.

|

|

26

|

Pu L: Efficacy of benazepril combined with

leflunomide in treatment of IgA nephropathy. Jiangsu Medical

Journal. 11:1277–1279. 2012.

|

|

27

|

Shen P: Leflunomide combined with low-dose

hormone therapy efficacy of IgA nephropathy. Chinese J General

Practice. 10:1580–1581. 2012.

|

|

28

|

Sun MD: Clinical observation of

leflunomide treatment of IgA nephropathy. Chinese J Gerontology.

16:2038–2039. 2009.

|

|

29

|

Wang L: Leflunomide combined with

prednisone treatment of progressive IgA nephropathy Chronic. Suzhou

University J Medical Science. 4:677–679. 2006.

|

|

30

|

Yang FY: Controlled studies of leflunomide

treatment of IgA nephropathy. China Practical Medical. 22:17–19.

2009.

|

|

31

|

Zhang LW: Efficacy of leflunomide combined

with hormone treatment of chronic progressive IgA nephropathy.

Chinese Journal of Modern Drug Application. 20:116–118. 2010.

|

|

32

|

Zhang Y: Efficacy of leflunomide combined

with prednisone in the treatment of advanced IgA nephropathy.

Academic J Guangzhou Medical College. 23:82–85. 2010.

|

|

33

|

Liu Y: Accompanied by moderate proteinuria

treatment of IgA nephropathy. China Medical Herald. 6:23–24.

2006.

|

|

34

|

Guo M: Compare leflunomide or

cyclophosphamide combined hormone therapy of chronic progressive

IgA nephropathy. Guide of China Medicine. 28:142–143. 2012.

|

|

35

|

Sun ZhX: Comparison of the efficacy of

treatment with leflunomide and cyclophosphamide IgA nephropathy

renal dysfunction. Suzhou University J Medical Science. 5:961–963.

2009.

|

|

36

|

Zhang HF: Leflunomide combined with

glucocorticoids contrast cyclophosphamide glucocorticoid treatment

efficacy of IgA nephropathy. J Taishan Medical College. 6:434–436.

2013.

|

|

37

|

Zhong ShH: Controlled studies of

leflunomide and cyclophosphamide-based therapy to nephrotic

syndrome of IgA nephropathy. J North China Coal Medical University.

5:593–594. 2011.

|

|

38

|

Lv J, Xu D, Perkovic V, Ma X, Johnson DW,

Woodward M, Levin A, Zhang H and Wang H; TESTING Study Group, :

Corticosteroid therapy in IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol.

23:1108–1116. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Katafuchi R, Ninomiya T, Mizumasa T, Ikeda

K, Kumagai H, Nagata M and Hirakata H: The improvement of renal

survival with steroid pulse therapy in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol

Dial Transplant. 23:3915–3920. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yoshikawa N, Honda M, Iijima K, Awazu M,

Hattori S, Nakanishi K and Ito H; Japanese Pediatric IgA

Nephropathy Treatment Study Group, : Steroid treatment for severe

childhood IgA nephropathy: A randomized, controlled trial. Clin J

Am Soc Nephrol. 1:511–517. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Maes BD, Oyen R, Claes K, Evenepoel P,

Kuypers D, Vanwalleghem J, Van Damme B and Vanrenterghem YF:

Mycophenolate mofetil in IgA nephropathy: Results of a 3-year

prospective placebo-controlled randomized study. Kidney Int.

65:1842–1849. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Frisch G, Lin J, Rosenstock J, Markowitz

G, D'Agati V, Radhakrishnan J, Preddie D, Crew J, Valeri A and

Appel G: Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) vs placebo in patients with

moderately advanced IgA nephropathy: A double-blind randomized

controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 20:2139–2145. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|