Introduction

Trigeminal neuralgia (TGN) is a transient, recurrent

and intense pain in the area on the face where the trigeminal (TG)

nerve is distributed (1–3). Previous studies have demonstrated that

80–90% of primary TGN cases are induced by vascular compression of

the TG nerve at the root entry zone (REZ) (1,4).

Superior cerebellar artery (SCA) and the anterior inferior

cerebellar artery (AICA) are the predominant vessels responsible

for the compression, followed by venous vessels (5,6). Brain

arteriovenous malformations (bAVMs) often manifest as cerebral

hemorrhage, particularly in young patients; therefore, patients

with unruptured bAVMs have a 2–4% risk of rupture and bleeding each

year, and each bleeding event is associated with an ~18% risk of

mortality (7,8). In addition, bAVMs also manifest as

chronic headaches, epilepsy and neurological deficits (8–11).

However, there have been relatively few reports of cases of TGN

caused by bAVM (4,12). The present case report describes a

case of TGN caused by bAVMs in the cerebellopontine angle (CPA).

Facial pain was successfully relieved after the patient received

partial embolization treatment, which may be associated with the

blockade of the pulsatile compression of the feeding arteries, the

arterialized draining veins or the malformed niduses. Therefore,

TGN caused by bAVMs is a vascular nerve compression disease. In the

present case study and review, the underlying mechanism and

treatment strategy of TGN caused by bAVMs were discussed in the

context of present case, and a literature review was carried

out.

Case report

A 32-year-old male was admitted to the First

Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China) on December 6,

2014, suffering from recurrent pain in his right cheek for two

years, which had increased in severity over the previous 6 months.

The patient reported that the pain began three years previously as

a stabbing-like, intense pain that occurred suddenly on the right

lower lip and mandible without any prior signs; each episode of

pain lasted for 10–30 sec. The first period of pain lasted ~1 week

and was self-relieved without medication. The pain recurred

following a period of 6 months, and the duration of each episode of

pain extended to 2–3 min. The patient was administered 800 mg oral

carbamazepine (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) daily, which was

effective at relieving the pain on the right side of the face of

the patient. In the 6 months prior to hospital admission, the

frequency of the pain in the right cheek of the patient increased.

The pain occurred >6 times every day and each episode lasted

10–30 min, and daily oral administration of 1,200 mg carbamazepine

was not effective at controlling the pain. Clinical examination

demonstrated that no significant trigger point could be palpated

and there were no abnormalities in corneal reflexes or facial

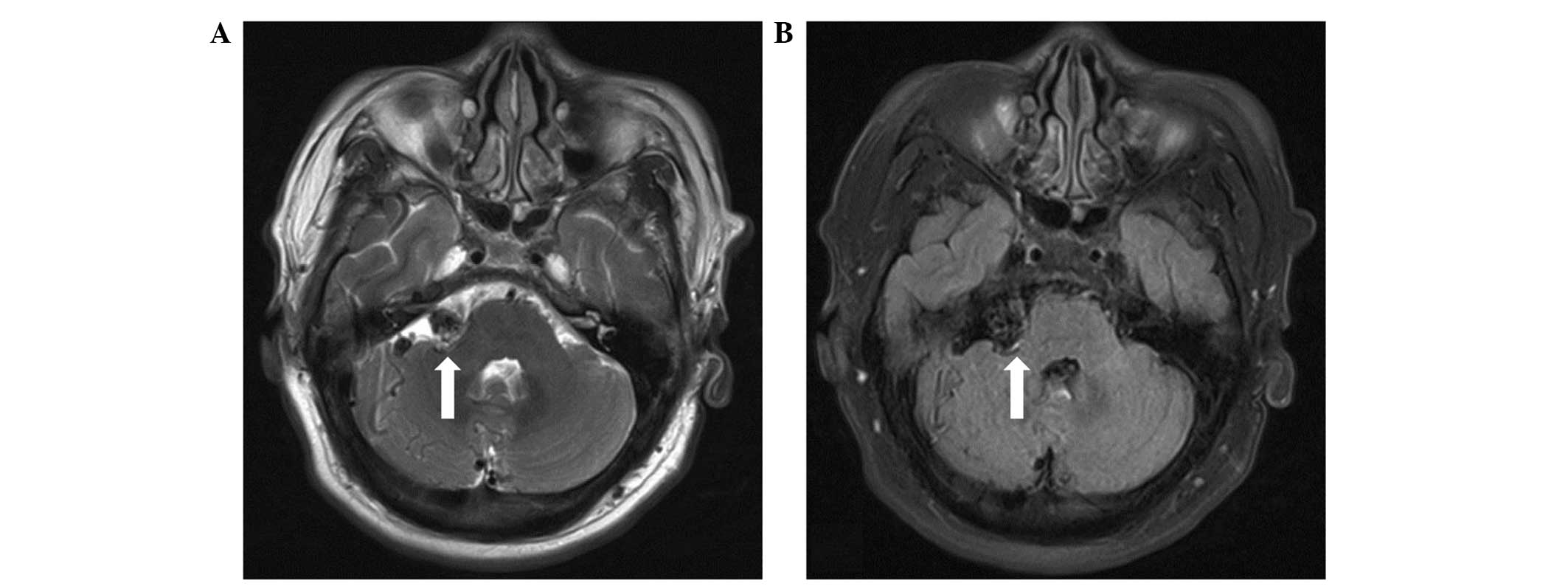

sensation. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated

the presence of flow-void signals in the abnormal vessels in the

right CPA (Fig. 1). Digital

subtraction angiography (DSA) further confirmed the diagnosis of

bAVMs, and demonstrated that the malformed niduses were fed by the

right SCA and the AICA, and drained into the adjacent venous

sinuses on the same side (Fig. 2).

Although the patient only exhibited symptoms of TGN, the patient

was treated with interventional embolization, due to the risk that

the bAVMs may bleed in the future. Embolization was conducted under

general anesthesia with intravenous 0.05–0.1 mg/kg midazolam (Nhwa,

Jiangsu, China), 1.0–1.5 µg/kg remifentanil (Renfu, Yichang,

China), 0.2–0.3 mg/kg etomidate (Nhwa), 0.6 mg/kg rocuronium

(Organon, Brussels, Belgium), and was maintained with 0.6 mg/kg

propofol (Nhwa), 5–10 mg/(kg/h) and 0.1–0.2 µg/(kg/min)

remifentanil (Renfu, Yichang, China). Following arterial puncture

and sheath insertion in the femoral artery using the Seldinger

technique (13), a 6F-guiding

catheter (Cordis Co., Miami, FL, USA) was inserted into the left

vertebral artery. Under the guidance of a Mirage micro-wire (ev3,

Irvine, California, USA), a Marathon micro-catheter was inserted

into the bAVMs. The micro-catheter entered the bAVMs via the right

AICA and onyx-18 glue (ev3) was slowly injected. Onyx-18 glue

diffused well in the bAVMs and embolized the majority of the

malformations. Angiography was conducted immediately following

surgery, which demonstrated that the majority of the bAVMs had

disappeared and the draining veins were patent (Fig. 2). There were no complications

following the surgical procedure and the pain in the right cheek of

the patient was completely relieved one week following the surgical

procedure. The patient was satisfied with the outcome of the

embolization surgery. Post-surgical follow-ups were conducted for a

period of two years via telephone. The patient experienced no

further pain in his right cheek, and thus chose not to return to

the hospital for a follow-up reexamination. The present study was

approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin

University and patient informed consent was obtained prior to the

study.

Literature review

A total of 29 studies (4,12,14–40)

which reported TGN caused by bAVMs were retrieved from the PubMed

database, the majority of which were clinical reports that

described individual cases. We searched the PubMed database up to

2015 using the key words ‘AVM’, ‘bAVM’, ‘arteriovenous

malformation’, ‘cerebral arteriovenous malformation’, ‘brain

arteriovenous malformation’, ‘Cerebral vascular malformation’ in

combination with ‘trigeminal neuralgia’ and ‘TGN’. Abstracts were

reviewed to identify relevant literature, only the TGN caused by

bAVM related literatures were enrolled.

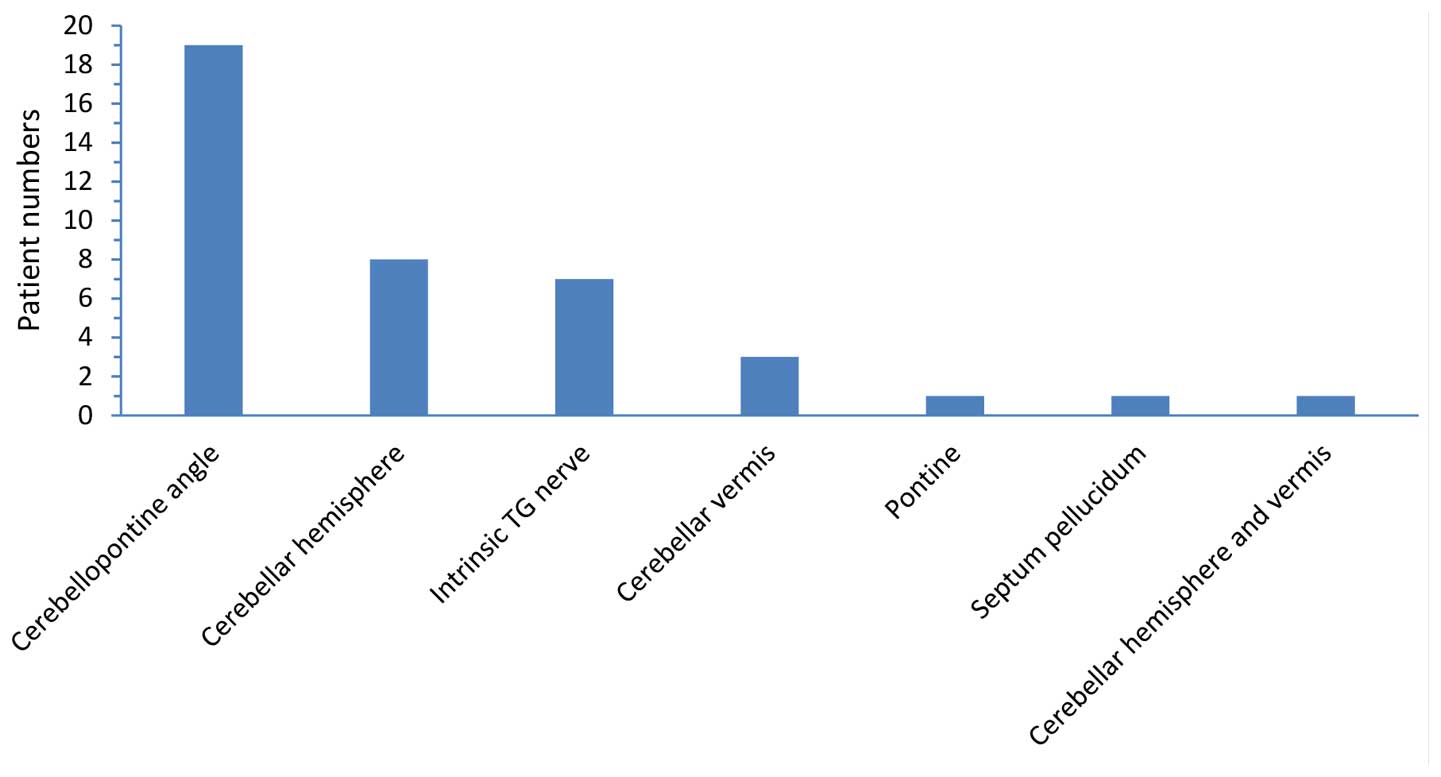

A total of 40 patients with TGN caused by bAVMs were

reported in these 29 studies (Table

I; 4,12,14-40). Excluding two patients for whom the information

was incomplete (27,33), there were 24 male and 14 female

patients (male:female ratio, ~1.71) aged between 23 and 69 years

with a mean age of 46.8±14.7 years. These patients presented with

bAVMs located in the CPA (n=19)(12,16,17,20,23,27–33,36,38),

cerebellar hemisphere (n=8)(15,18,21,26,34,35,40), the

TG nerve (n=7)(22,25,39), the

cerebellar vermis (n=3)(4,14,24), the

pontine (n=1)(37), the septum

pellucidum (n=1)(19) and both the

cerebellar hemisphere and cerebellar vermis (n=1)(38) (Fig.

3). Five of these patients had a confirmed history of repeated

hemorrhage (19,29,32,33,35). The

majority of these patients suffered from TGN on the same side as

the bAVM lesions; however, one patient suffered from TGN on the

contralateral side of the bAVMs lesions (40), and two patients suffered from

coexistent TGN and hemifacial spasm on the same side (14,16). In

terms of treatment, 2 patients received drug therapy (17) and 1 patient was without mention of

treatment (12). The other 37

patients received non-drug treatment (4,14–40), 11

patients received surgical resection alone (19,25,27–30,32), 2

patients received surgical resection following partial embolization

(23,26), 1 patient received surgical resection

following destructive neurosurgical manipulation of the TG

nerve(31), 3 patients received

surgical resection of bAVMs combined with microvascular

decompression (MVD; 14,15,18,20,24), 5 patients received an

interventional embolization treatment, 2 patients received

radiotherapy following embolization (4,21), 6

patients received MVD treatment alone (37–39), 2

patients received radiotherapy following MVD (36,40), 4

patients received destructive neurosurgical manipulation of the TG

nerve (16,17,33,38), and

1 patient received stereotactic radiotherapy (SRS; 22) (Fig. 4).

| Table I.Literature review of patients with

trigeminal neuralgia caused by bAVMs. |

Table I.

Literature review of patients with

trigeminal neuralgia caused by bAVMs.

|

|

|

|

| History of drug

therapy | Non-drug

therapy |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Author | Gender/age | bAVMs location | Compressing

vessels | Drugs | Therapeutic

effects | Treatment

methods | Complications | Therapeutic

effects | Notes | Refs. |

|---|

| Kikuchi et

al | Male/45 | CPA | Feeding

arteries | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of

bAVMs | Not mentioned | Immediate complete

relief | The patient had a

history of SAH 15 years prior | (29) |

| Figueiredo et

al | Male/18 | CPA | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | Transient numbness

in V3 | Immediate complete

relief |

| (30) |

| Kawano et

al | Male/48 | CPA | Malformed niduses

and draining veins | Not mentioned | Pain aggravated

after 2 years | Glycerol rhizolysis

was performed on either side of the semilunar ganglion of the TG

nerve, and shown to be ineffective; subsequent resection of the

bAVM was performed | Not mentioned | Immediate complete

relief |

| (31,32) |

| Kawano et

al | Female/61 | CPA | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of

bAVMs | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | The patient had a

history of hemorrhage in the left CPA 10 days prior to admission to

the hospital | (20) |

| Johnson and

Salmon | N/A | CPA | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of the TG

nerve | Not mentioned | Pain relief | The patient had a

history of SAH and multiple events of transient loss of

consciousness | (33) |

| Niwa et

al | Female/44 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Feeding arteries

and draining veins | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of bAVMs

and MVD | Not mentioned | Immediate complete

relief |

| (34) |

| Nishizawa et

al | Male/42 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Feeding

arteries | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | TGN recurred 6

months after TG nerve was blocked. Resection of the bAVMs and MVD

was subsequently performed | Not mentioned | Immediate complete

relief | The patient had a

history of SAH 10 years prior | (35) |

| Edwards et

al | Male/38 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Draining veins,

malformed niduses, and feeding arteries | Carbamazepine | Poor | Resection of the

bAVMs and MVD | Mild V1

hypesthesia | Immediate

relief |

| (25) |

|

| Female/55 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Draining veins and

malformed niduses | Carbamazepine | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | Mild V1–3

hypesthesia and corneal areflexia | Immediate

relief |

|

|

|

| Female/46 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Draining veins and

malformed niduses | Carbamazepine | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | Mild V1 & V2

hypesthesia and occasional mild dysesthesia | Immediate

relief |

|

|

|

| Female/35 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Draining veins and

malformed niduses | Carbamazepine | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | None | Immediate

relief | TGN recurred 4

years later; the be relieved by drugs |

|

|

| Female/36 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Draining veins and

malformed niduses | Carbamazepine | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | Small pontine

hematoma, transient ataxia, VII weakness, nausea, vomiting,

permanent V2 & V3 anesthesia, V1 hypesthesia, and corneal

areflexia | Immediate

relief |

| Mineura et

al | Male/21 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Draining veins | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Embolization and

resection of bAVMs | Mild cerebellar

ataxia | Complete

relief |

| (26) |

| Nomura et

al | N/A | CPA | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of

bAVMs | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

| (27) |

|

| Male/44 | CPA | Malformed

niduses | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Resection of

bAVMs | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

|

|

| Mendelowitsch et

al | Female/47 | CPA | Feeding

arteries | Not mentioned | Poor | Resection of

bAVMs | Pulmonary

embolism | Complete

relief |

| (28) |

| Anderson et

al | Female/39 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | Poor | SRS | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

| (22) |

| Wanke et

al | Male/56 | CPA | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | Poor | Embolization and

resection of bAVMs | Hydrocephalus and

SAH occurred after embolization. Surgical resection was

subsequently performed. Paresis of the III, VII and XII cranial

nerves occurred, and the trigeminal neural sensation was reduced.

Every function except the trigeminal neural sensation recovered

after 3 months | Complete relief

following resection |

| (23) |

| Athanasiou et

al | Male/56 | Cerebellar

vermis | Feeding

arteries | Carbamazepine | Little effect | Embolization | None | Complete

relief |

| (24) |

| García-Pastor et

al | Male/57 | CPA | Malformed

niduses | Not mentioned | Poor | The effect of

radiofrequency thermocoagulation of the TG nerve was poor;

micro-balloon compression of the TG nerve was subsequently

performed. | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

| (38) |

|

| Male/68 | CPA | Malformed

niduses | Not mentioned | Poor | MVD | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

|

|

|

| Male/40 | Cerebellar

hemisphere and vermis | Feeding

arteries | Not mentioned | Poor | MVD | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

|

|

|

| Male/54 | CPA | Malformed

niduses | Not mentioned | Poor | MVD | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

|

|

| Levitt et

al | Female/13 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | Poor | Multiple

embolization treatments of bAVMs had no effect; the artery of the

foramen rotundum (the blood-supplying artery of the TG nerve V2

branch) was subsequently embolized, following which the pain was

relieved | A small area of

hypesthesia on the left cheek | Immediate relief

following embolization of the artery of the foramen rotundum |

| (18) |

| Talanov et

al | Male/16 | Septum

pellucidum | Draining veins | Not mentioned |

| Resection of

bAVMs | None | Not mentioned | Pain on the left

side of the TG nerve combined with hemorrhage | (19) |

| Simon et

al | Male/72 | CPA | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | The pain increased

after 1 year | Embolization | None | Immediate complete

relief. The pain recurred 17 months later; but was relieved

following secondary embolization |

| (20) |

| Lesley | Male/55 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Feeding arteries

and draining veins | No history of drug

therapy |

| Staged embolization

and SRS | None | Complete

relief |

| (21) |

| Ferroli et

al | Female/52 | Pontine | Draining veins | Carbamazepine | Poor | MVD | None | 50% free after 1

month |

| (37) |

|

| Male/38 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Feeding arteries

and draining veins | Not mentioned | Poor | Radiofrequency

thermocoagulation of TG nerve was poor; MVD was subsequently

performed | Not mentioned | Complete

relief |

| Karibe et

al | Male/55 | Intrinsic TG

nerve | Feeding

arteries | Carbamazepine | Little effect | MVD | None complete

relief | Immediate and |

| (39) |

| Sato et

al | Female/49 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Draining veins | Not mentioned | Not mentioned | MVD + SRS | None | Complete relief

after 1 year. The size of the bAVMs was reduced | The patient had

pain on the contralateral TG nerve | (40) |

| Mori et

al | Male/69 | Cerebellar

vermis | Feeding

arteries | Carbamazepine | The pain was

relieved for 5 years, then gradually reappeared | Embolization and

SRS | Temporary truncal

ataxia following embolization | Partial relief was

achieved following embolization. Complete pain relief was achieved

following subsequent radiotherapy |

| (4) |

| Yip et

al | Female/64 | CPA | Malformed

niduses | Carbamazepine | Poor | Not mentioned |

|

|

| (12) |

| Dou et

al | Female/24 | Cerebellar

vermis | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | Poor | Embolization | None | HFS and TNG was

completely relieved | Combined with

HFS | (14) |

| Kono et

al | Male/53 | Cerebellar

hemisphere | Feeding

arteries | Anti-TN

medication | The pain increased

gradually | Embolization | None | The pain was

completely relieved after 1 month |

| (15) |

| Son et

al | Male/42 | CPA | Not mentioned | Non-specific | Poor | Radiofrequency

thermocoagulation of TG nerve and injection of carnitine | None | The pain was

relieved; carnitine was regularly injected to relieve facial spasm

(every 3–4 months) | Combined with

facial spasm | (16) |

| Machet et

al | Male/61 | CPA | Not mentioned | Oxcarbazepine | Follow-up was

conducted for 10 months; the pain was relieved | None | Not mentioned |

|

| (17) |

| Sumioka et

al | Male/66 | CPA | Feeding arteries

and malformed niduses | Not mentioned |

| MVD + SRS | Not mentioned | Immediate complete

relief. MRI showed that the bAVMs disappeared |

| (36) |

|

| Female/64 | CPA | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | Follow-up was

conducted for 18 months; the pain was relieved | None | Not mentioned |

|

|

|

|

| Male/50 | CPA | Not mentioned | Carbamazepine | The pain was

partially relieved | Micro-balloon

compression of the TG nerve | Not mentioned | Pain partially

disappeared |

Discussion

TGN is one of the most common symptoms of

neurovascular compression, and is a demyelinating lesion of the

sensory fibers of the TG nerve caused by compression of the TG

nerve at REZ by the SCA and the AICA (1–4).

However, TGN caused by bAVMs remains rare, accounting for

0.22–1.78% of primary TGN cases (12,16,38). The

present case study described a case of TGN caused by bAVMs in a

middle-aged male patient suffering from recurrent pain in the right

cheek. MRI and DSA analyses demonstrated bAVMs in the CPA of the

posterior fossa on the affected side. As it remains difficult to

distinguishing the symptoms of TGN caused by bAVMs, particularly

TGN induced by insignificant bAVMs, which is usually negative in

angiography, the symptoms of primary TGN can be easily misdiagnosed

(12,25). However, the majority of patients can

be accurately diagnosed through MRI and cerebral angiography

(4,20,21,36).

Previous studies have demonstrated that combined use of

three-dimensional (3D) constructive interference in steady state

MRI and 3D time of flight angiography clearly demonstrate the

anatomic association between the TG nerve and the surrounding

vessels, as well as other neighboring structures (41,42). DSA

clearly shows the bAVMs, including the feeding arteries, niduses

and draining veins, and determines whether they are associated with

aneurysms, which is beneficial for the preoperative evaluation of

patients (17). Among the 40

previous case reports (4,12,14–40), 39

patients (97.5%) presented with bAVMs in the posterior fossa. bAVMs

located in the posterior fossa are more likely to result in TGN

(4,12,14–18,20–40).

García-Pastor (38) conducted a

study on 375 cases of bAVMs, which demonstrated that 1.3% of the

patients with bAVMs developed TGN, whereas 9.8% of the patients

with bAVMs in the posterior fossa developed TGN. The majority of

the patients suffered from TGN on the same side as the bAVMs, and

only one patient suffered from TGN on the contralateral side of the

lesions, which was predominantly caused by the compression of the

contralateral TG nerve REZ by the arterialized draining veins

(40). The aforementioned findings

also demonstrated that TGN caused by bAVMs is a symptom of

neurovascular compression, caused by the pulsatile compression of

vessels. Pulsatile compression of the vessels may be caused by the

feeding arteries of bAVMs, arterialized draining veins or

malformation niduses (38,40,43).

Among the 40 patients evaluated (4,12,14–40),

there were 27 patients (4,12,15,19,21,24–29,31,34–40) in

whom TGN was demonstrated to originate from vascular compression as

determined by angiography or during the surgical procedure. Of

these 27 patients, TGN was caused by compression by the feeding

arteries of bAVMs (n=8)(4,15,24,28,29,35,38,39), the

draining venous system (n=4)(19,26,37,40),

malformation niduses (n=5)(12,27,38),

simultaneous compression by the feeding arteries and the draining

venous system (n=3)(21,34,38),

simultaneous compression by the feeding arteries and the

malformation niduses (n=1)(36), the

simultaneous compression by the draining venous system and the

malformation niduses (n=5)(25,31) and

simultaneous compression by the feeding arteries, the draining

venous system and the malformation niduses (n=1) (25). Since the origin of vascular

compression could not be confirmed by image analysis in certain

patients, and these patients had also received drug therapy,

interventional embolization, and destructive neurosurgical

manipulation of the TG nerve, the incidence of TGN originating from

vascular compression may be even higher.

Currently, the majority of treatments for TGN caused

by bAVMs are determined on an individual basis, and there has been

no consistent conclusion as to the optimal treatment for TGN caused

by bAVMs (14–16). Drug therapy did not yield an ideal

therapeutic effect in the majority of cases, and the patients who

received drug therapy predominantly proceeded to seek non-drug

treatments (4,12,14–16,22,23,25,28,30–32).

Non-drug treatments include surgical resection of bAVMs, MVD, SRS,

and destructive neurosurgical manipulation of the TG nerve

(4,16,33,36,37).

Therefore, when selecting a treatment, it is necessary to

comprehensively consider whether the patient has a history of

hemorrhage, whether the bAVMs are associated with aneurysms and the

origin of the compression of the TG nerve.

Theoretically, complete surgical resection is the

ideal therapeutic option, as it eliminates the compression on the

TG nerve and avoids the potential risk of hemorrhage of bAVMs,

which is particularly important for patients with a history of

hemorrhage. In addition, the craniotomy for resection of bAVMs may

also confirm whether the feeding arteries and the draining veins

compress the TG nerve root; if necessary, MVD can be performed

simultaneously (44). Among the 40

patients evaluated (4,12,14–40),

42.5% of the patients received surgical resection (n=17), and

amongst these 17 patients (19,23,25–32,34,35), 11

patients received surgical resection alone (19,25,27–30,32), 3

patients received surgical resection combined with MVD (25,34,35), and

2 patients received surgical resection due to complications

following embolization (23,26), and 1 patient received surgical

resection due poor effect after destructive neurosurgical

manipulation of the TG nerve (31).

The pain caused by TGN was immediately relieved in all the patients

who received surgical resection. The longest duration of follow-up

visits in these previous studies was 109 months (25). According to the long-term follow-up

visits reported, relapsed pain was only reported in one patient at

a four-year post-surgical follow-up, and this pain was controlled

by 400 mg/day carbamazepine (25).

The majority of these lesions were located deep in the posterior

fossa adjacent to the brain stem and surrounding important nerves

(23,26,27).

Furthermore, there were numerous complications during surgical

resection, particularly for patients with bAVMs in the TG nerve

REZ. Edwards et al (25)

reported the treatment of five patients with bAVMs in the TG nerve

REZ through surgical resection, and following the surgical

procedure, four of these patients experienced varying levels of

dysesthesia of the TG nerve, and one patient also experienced

weakening of the facial neurological function, short-term ataxia

and cerebellar hematoma. Although the remission rate of TNG is very

high after surgical resection, there are also many complications.

Thus it is a necessary to weigh the benefits and risks before the

operation.

It is sometimes difficult to perform complete

surgical resection of bAVMs, and this procedure may also be

unnecessary for some patients. Among the 40 patients (4,12,14–40)

with TGN caused by bAVMs, 55% of patients (n=22)(4,15,19,21,24–26,28,29,33–40)

presented with TGN which partially or completely originated from

the compression of feeding arteries or the draining veins, which

was confirmed by image analysis or during the surgical procedure.

Therefore, surgical resection of bAVMs was unnecessary in these

patients with TGN with no history of hemorrhage, and MVD surgery

would have been sufficient. MVD surgery of the TG nerve is >90%

effective and is capable of preserving neurological function

relatively well; thus, MVD surgery has become the first choice of

surgical treatment for primary TGN (45). Furthermore, bAVMs in the CPA, and

even malformed niduses in the TG nerve, may not necessarily result

in TGN (39,43,46).

Therefore, focusing on complete resection of bAVMs as the

predominant therapeutic option may cause further complications. The

mid-term results of a multicenter, randomized control study which

investigated the treatments of unruptured bAVMs demonstrated that

the effects of drug therapies are superior to those of invasive

therapies when treating unruptured bAVMs (47). Among the 40 patients evaluated in the

present review (4,12,14–40), 27%

of patients (n=11) received MVD surgery, with the longest duration

of follow-up being 18 months (36).

A 100% overall effective rate was achieved and no

surgery-associated complications occurred (34–40).

Interventional embolization can be used to reduce

the size of bAVMs by reducing blood supply to bAVMs (4,21,23,26).

This procedure is predominantly performed to surgically treat bAVMs

or as an adjuvant therapy prior to SRS (4,21,23,26).

However, when treating TGN caused by bAVMs, TGN may be effectively

relieved following partial embolization of bAVMs due to the change

in hemodynamics, which also demonstrates that TGN caused by bAVMs

is a symptom of neurovascular compression (20). Due to these characteristics,

interventional embolization was performed on the present patient

and TGN was completely relieved following successful embolization

of the majority of the bAVMs. Post-embolization follow-ups were

conducted for two years, and the therapeutic effect of this

treatment option remained satisfactory. Among the 40 patients

(4,12,14–40)

evaluated in the present review, 22.5% of patients (n=9)(4,14,15,18,20,21,23,24,26)

underwent interventional embolization and experienced significantly

relieved TGN following embolization. Among these 9 patients, 5

patients received an interventional embolization treatment alone

(14,15,18,20,24), 2

patients received subsequent SRS (4,21) and 2

patients received secondary surgical resection(23,26). The

longest duration of follow-up visits for patients who underwent

interventional embolization was six years (4). One patient reported relapsed pain 17

months post-embolization and the pain was subsequently relieved

following a secondary embolization (4). The pain relief may be associated with

the blocking of the pulsatile compression of the feeding arteries

of the bAVMs, the arterialized draining veins or the malformed

niduses that compressed the TG nerve following embolization, which

appears to have a similar mechanism to the MVD of the TG nerve.

However, caution should be taken with this therapeutic option as

interventional embolization and the change in hemodynamics

following embolization may induce ischemia, hemorrhage or

embolization of the venous system (4,23,26).

Among the aforementioned eight patients who received embolization,

one patient experienced transient ataxia (4), one patient received secondary surgical

resection of bAVMs due to subarachnoid hemorrhage and hydrocephalus

following the embolization (23),

and one patient suffered from severe paresis and sensory

disturbance due to the dilated draining veins following

embolization, which required surgical resection (26). Furthermore, since the rate of

complete embolization is restricted when treating bAVMs with

interventional therapy alone, and post-embolization recanalization

is relatively common, embolization alone may not result in a

long-term therapeutic effect. Simon et al (20) reported the case of a patient with TGN

caused by bAVMs whose pain was relieved following embolization;

however, the pain recurred 17 months later. It has also been

demonstrated that only short-term pain relief was achieved

following multiple embolization procedures (18), which may be associated with the

recanalization of bAVMs.

SRS is often performed following partial

embolization or combined with other treatment methods (4,21,36,40).

Among the 40 patients evaluated in the present review (4,12,14–40),

there was only one report (22) of

the achievement of an effective therapeutic effect of SRS alone. In

this case, the bAVMs were located inside the TG nerve and the size

of the malformation niduses was ~1.2×0.8×0.9 cm; the TGN was

completely relieved following 13 months of SRS (22). Notably, Levitt et al (18) treated a patient with TGN by

embolizing the supplying artery of the V2 branch of the TG nerve,

an artery of the foramen rotundum, which induced sustained relief

from TGN, but resulted in hypoesthesia of the cheeks on the same

side. Previous studies have also reported other palliative

destructive neurosurgical techniques of the TG nerve root (16,17,33,38),

including radiofrequency thermocoagulation, glycerol rhizolysis,

balloon compression and resection of the TG nerve; however, these

palliative therapies may result in complications, such as facial

numbness and weakened corneal reflexes (16,17,33,38).

Furthermore, the therapeutic effects of these palliative therapies

remain uncertain, and TGN has a relatively high recurrence rate

when treated with these therapeutic strategies (16,17,33,38).

In conclusion, surgical resection of the malformed

vessels is an ideal therapeutic option in theory, as this approach

relieves TGN and eliminates the risk of hemorrhage of bAVMs;

whereas MVD surgery is a recommended treatment for patients who

cannot receive surgical resection of bAVMs. Good therapeutic

outcomes have also been achieved with interventional embolization

in certain patients, including the patient described in the present

case study. Destructive neurosurgical manipulation of the TG nerve

may result in facial numbness and weakened corneal reflexes, and

has a high recurrence rate; therefore, this approach is only

recommended as an alternative for elderly surgery-intolerant

patients.

References

|

1

|

Love S and Coakham HB: Trigeminal

neuralgia: Pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 124:2347–2360. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alksne J, Argoff C,

Brainin M, Burchiel K, Nurmikko T and Zakrzewska JM: American

Academy of Neurology Society; European Federation of Neurological

Society: AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management.

Eur J Neurol. 15:1013–1028. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Headache Classification Committee of the

International Headache Society (IHS): The international

classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition (beta version).

Cephalalgia. 33:629–808. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mori Y, Kobayashi T, Miyachi S, Hashizume

C, Tsugawa T and Shibamoto Y: Trigeminal neuralgia caused by nerve

compression by dilated superior cerebellar artery associated with

cerebellar arteriovenous malformation: Case report. Neurol Med Chir

(Tokyo). 54:236–241. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ishikawa M, Nishi S, Aoki T, Takase T,

Wada E, Ohwaki H, Katsuki T and Fukuda H: Operative findings in

cases of trigeminal neuralgia without vascular compression:

Proposal of a different mechanism. J Clin Neurosci. 9:200–204.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL,

Subach BR, Comey CH and Resnick DK: Microvascular decompression of

cranial nerves: Lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg.

90:1–8. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Mast H, Young WL, Koennecke H-C, et al:

Risk of spontaneous haemorrhage after diagnosis of cerebral

arteriovenous malformation. The Lancet. 350:1065–1068. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Nataraj A, Mohamed MB, Gholkar A, Vivar R,

Watkins L, Aspoas R, Gregson B, Mitchell P and Mendelow AD:

Multimodality treatment of cerebral arteriovenous malformations.

World Neurosurg. 82:149–159. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Whitehead KJ, Smith MC and Li DY:

Arteriovenous malformations and other vascular malformation

syndromes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 3:a0066352013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rodríguez-Hernández A, Kim H, Pourmohamad

T, Young WL and Lawton MT: University of California, San Francisco

Arteriovenous Malformation Study Project: Cerebellar arteriovenous

malformations: Anatomic subtypes, surgical results, and increased

predictive accuracy of the supplementary grading system.

Neurosurgery. 71:1111–1124. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mast H, Young WL, Koennecke HC, Sciacca

RR, Osipov A, Pile-Spellman J, Hacein-Bey L, Duong H, Stein BM and

Mohr JP: Risk of spontaneous haemorrhage after diagnosis of

cerebral arteriovenous malformation. Lancet. 350:1065–1068. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yip V, Michael BD, Nahser HC and Smith D:

Arteriovenous malformation: a rare cause of trigeminal neuralgia

identified by magnetic resonance imaging with constructive

interference in steady state sequences. QJM: monthly journal of the

Association of Physicians. 105:895–898. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Seldinger SI: Catheter replacement of the

needle in percutaneous arteriography: a new technique. Acta Radiol.

39:368–376. 1953. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dou NN, Hua XM, Zhong J and Li ST: A

successful treatment of coexistent hemifacial spasm and trigeminal

neuralgia caused by a huge cerebral arteriovenous malformation: A

case report. J Craniofac Surg. 25:907–910. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kono K, Matsuda Y and Terada T: Resolution

of trigeminal neuralgia following minimal coil embolization of a

primitive trigeminal artery associated with a cerebellar

arteriovenous malformation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 155:1699–1701.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Son BC, Kim DR, Sung JH and Lee SW:

Painful tic convulsif caused by an arteriovenous malformation. Clin

Neuroradiol. 22:365–369. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Machet A, Aggour M, Estrade L, Chays A and

Pierot L: Trigeminal neuralgia related to arteriovenous

malformation of the posterior fossa: Three case reports and a

review of the literature. J Neuroradiol. 39:64–69. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Levitt MR, Ramanathan D, Vaidya SS, Hallam

DK and Ghodke BV: Endovascular palliation of AVM-associated

intractable trigeminal neuralgia via embolization of the artery of

the foramen rotundum. Pain Med. 12:1824–1830. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Talanov AB, Filatov Iu M, Eliava ShSh,

Novikov AE and Kulishova IaG: Arteriovenous malformation of septum

pellucidum in combination with persistent trigeminal neuralgia. Zh

Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko 50–53. discusion 53–54. 2009.(In

Russian).

|

|

20

|

Simon SD, Yao TL, Rosenbaum BP, Reig A and

Mericle RA: Resolution of trigeminal neuralgia after palliative

embolization of a cerebellopontine angle arteriovenous

malformation. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 70:161–163. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lesley WS: Resolution of trigeminal

neuralgia following cerebellar AVM embolization with Onyx.

Cephalalgia. 29:980–985. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Anderson WS, Wang PP and Rigamonti D: Case

of microarteriovenous malformation-induced trigeminal neuralgia

treated with radiosurgery. J Headache Pain. 7:217–221. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wanke I, Dietrich U, Oppel F and Puchner

MJ: Endovascular treatment of trigeminal neuralgia caused by

arteriovenous malformation: Is surgery really necessary? Zentralbl

Neurochir. 66:213–216. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Athanasiou TC, Nair S, Coakham HB and

Lewis TT: Arteriovenous malformation presenting with trigeminal

neuralgia and treated with endovascular coiling. Neurol India.

53:247–248. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Edwards RJ, Clarke Y, Renowden SA and

Coakham HB: Trigeminal neuralgia caused by microarteriovenous

malformations of the trigeminal nerve root entry zone: Symptomatic

relief following complete excision of the lesion with nerve root

preservation. J Neurosurg. 97:874–880. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mineura K, Sasajima H, Itoh Y, Kowada M,

Tomura N and Goto K: Development of a huge varix following

endovascular embolization for cerebellar arteriovenous

malformation. A case report. Acta Radiol. 39:189–192. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nomura T, Ikezaki K, Matsushima T and

Fukui M: Trigeminal neuralgia: Differentiation between intracranial

mass lesions and ordinary vascular compression as causative

lesions. Neurosurg Rev. 17:51–57. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mendelowitsch A, Radue EW and Gratzl O:

Aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation and arteriovenous fistula in

posterior fossa compression syndrome. Eur Neurol. 30:338–342. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kikuchi K, Kamisato N, Sasanuma J,

Watanabe K and Kowada M: Trigeminal neuralgia associated with

posterior fossa arteriovenous malformation and aneurysm fed by the

same artery. Case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 30:918–921.

1990.(In Japanese). View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Figueiredo PC, Brock M, De Oliveira AM

Júnior and Prill A: Arteriovenous malformation in the

cerebellopontine angle presenting as trigeminal neuralgia. Arq

Neuropsiquiatr. 47:61–71. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kawano H, Hayashi M, Kobayashi H, Tsuji T,

Kabuto M and Kubota T: Gas CT cisternography of trigeminal

neuralgia caused by AVM of the cerebellopontine angle. AJNR Am J

Neuroradiol. 8:161–162. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kawano H, Kobayashi H, Hayashi M, Tsuji T,

Kabuto M and Nozaki J: Trigeminal neuralgia caused by arteriovenous

malformation of the cerebellopontine angle-report of two cases. No

to Shinkei. 36:1175–1179. 1984.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Johnson MC and Salmon JH: Arteriovenous

malformation presenting as trigeminal neuralgia. Case report. J

Neurosurg. 29:287–289. 1968. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Niwa J, Yamamura A and Hashi K: Cerebellar

arteriovenous malformation presenting as trigeminal neuralgia. No

Shinkei Geka. 16:753–756. 1988.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nishizawa Y, Tsuiki K, Miura K, Murakami

M, Kirikae M, Hakozaki S, Saiki I and Kanaya H: Multiple

arteriovenous malformations of left parietal lobe and left

cerebellar hemisphere with symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia: A case

report. No Shinkei Geka. 16(Suppl 5): S625–S630. 1988.(In

Japanese).

|

|

36

|

Sumioka S, Kondo A, Tanabe H and Yasuda S:

Intrinsic arteriovenous malformation embedded in the trigeminal

nerve of a patient with trigeminal neuralgia. Neurol Med Chir

(Tokyo). 51:639–641. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ferroli P, Acerbi F, Broggi M and Broggi

G: Arteriovenous micromalformation of the trigeminal root:

Intraoperative diagnosis with indocyanine green videoangiography:

Case report. Neurosurgery. 67(3 Suppl Operative): onsE309–onsE310;

discussion onsE310. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

García-Pastor C, López-González F,

Revuelta R and Nathal E: Trigeminal neuralgia secondary to

arteriovenous malformations of the posterior fossa. Surg Neurol.

66:207–211; discussion 211. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Karibe H, Shirane R, Jokura H and

Yoshimoto T: Intrinsic arteriovenous malformation of the trigeminal

nerve in a patient with trigeminal neuralgia: Case report.

Neurosurgery. 55:14332004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Sato K, Jokura H, Shirane R, Akabane T,

Karibe H and Yoshimoto T: Trigeminal neuralgia associated with

contralateral cerebellar arteriovenous malformation. Case

illustration. J Neurosurg. 98:13182003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Garcia M, Naraghi R, Zumbrunn T, Rösch J,

Hastreiter P and Dörfler A: High-resolution 3D-constructive

interference in steady-state MR imaging and 3D time-of-flight MR

angiography in neurovascular compression: A comparison between 3T

and 1.5T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 33:1251–1256. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Linn J, Moriggl B, Schwarz F, Naidich TP,

Schmid UD, Wiesmann M, Bruckmann H and Yousry I: Cisternal segments

of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves: Detailed

magnetic resonance imaging-demonstrated anatomy and neurovascular

relationships. J Neurosurg. 110:1026–1041. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Krischek B, Yamaguchi S, Sure U, Benes L,

Bien S and Bertalanffy H: Arteriovenous malformation surrounding

the trigeminal nerve-case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo).

44:68–71. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Abla AA, Nelson J, Rutledge WC, Young WL,

Kim H and Lawton MT: The natural history of AVM hemorrhage in the

posterior fossa: Comparison of hematoma volumes and neurological

outcomes in patients with ruptured infra- and supratentorial AVMs.

Neurosurg Focus. 37:E62014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Zakrzewska JM and Linskey ME: Trigeminal

neuralgia. Clin Evid (Online). 10:12072014.

|

|

46

|

Maher CO, Atkinson JL and Lane JI:

Arteriovenous malformation in the trigeminal nerve. Case report. J

Neurosurg. 98:908–912. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Mohr JP, Parides MK, Stapf C, Moquete E,

Moy CS, Overbey JR, Al-Shahi Salman R, Vicaut E, Young WL, Houdart

E, et al: Medical management with or without interventional therapy

for unruptured brain arteriovenous malformations (ARUBA): A

multicentre, non-blinded, randomised trial. Lancet. 383:614–621.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|