Introduction

Pegylated IFN (PEG-IFN) and ribavirin (RBV)

treatment for chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection in 2005 has

improved treatment outcomes (1).

Furthermore, the approval of a new PEG-IFN/RBV/telaprevir (TVR)

triple treatment for CHC in 2011 improved the rate of achieving a

sustained virologic response (SVR) and shortened the length of

treatment (1–3).

Qualitative and quantitative methods have identified

that IFN-based CHC treatment has a negative impact on the

health-related quality of life (HRQOL) of patients (4–6). To the

best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports on the impact

of TVR-based treatment on the QOL of patients with CHC infection.

In TVR-based triple treatment, the possibility of side effects,

such as high-grade anemia, skin disorders and renal insufficiency,

has made understanding its impact on patient QOL important.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the HRQOL of

patients with CHC treated with TVR-based triple therapy using the

36-item short form health survey (SF-36) (7).

Materials and methods

Study participants and treatment

The present study examined 34 patients with CHC (18

men and 16 women; mean age, 62.8±10.1 for men and 63.6±10.4 years

for women), who could be followed up long term, following triple

treatment with PEG-IFN/RBV/TVR at Saiseikai Niigata Daini Hospital

(Niigata, Japan) between November 2011 and March 2014. Written

informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the Ethical

Committee of Saiseikai Niigata Daini Hospital (Niigata, Japan)

approved this study, which was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki.

All patients received TVR (Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma

Corporation, Osaka, Japan) in combination with PEG-IFN α2b and RBV

(both MSD, Tokyo, Japan) for 12 weeks. This was followed by an

additional 12 weeks of PEG-IFN α2b and RBV alone. TVR (750 mg) was

orally administered every 8 h, PEG-IFN α2b (1.5 µg/kg) was injected

subcutaneously weekly and oral RBV was given daily at a dose of

between 600 and 800 mg based on the body weight of the patient.

Assessment of HRQOL

The association between the HRQOL of patients with

CHC treated with TVR-based treatment and gender, age or treatment

history was examined. The HRQOL of study participants was measured

using a 36-item self-administered questionnaire, the SF-36. The

SF-36 evaluates the following eight physical and mental health

areas: Physical functioning (PF), physical role functioning (RP),

bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social role

functioning (SF), emotional role functioning (RE) and mental health

(MH) (7). Each of the 8 areas was

scored on a scale of 0–100, where a higher score indicated better

health subjectively. These scores were calculated from the

questionnaires as described previously (8–10).

Briefly, a Japanese-validated version of SF-36 was used and the

results were compared to a Japanese normative sample score of the

SF-36 in 2,966 individuals (10,11).

Scores were calculated based on the standard value (100 points) for

the Japanese population.

Evaluation of HRQOL using the SF-36 was performed

prior to treatment (0W), 2 weeks following the start of treatment

(2W), 3 months following the start of treatment (12W), 6 months

following the start of treatment (24W) and 1 year following the

start of treatment (48W). In examination on the basis of treatment

history, patients were classified as naïve (no prior CHC treatment;

n=14), relapsed (recurrence of virus following treatment for CHC;

n=19) or null responders (no change in viral load following CHC

treatment; n=1, excluded from analysis due to low number).

Statistical analysis

Intergroup HRQOL was compared using the Student's

t-test, the chi-squared test and the Mann-Whitney U test, while

scores prior to and following the start of treatment were compared

using a paired t-test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference. Statistical analysis was

performed using StatView software (version 5.0; SAS Institute,

Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Examination on the basis of

gender

The clinical characteristics of patients were

compared on the basis of gender (Table

I). The men showed significantly higher values for height

(P<0.01), weight (P<0.01), and body mass index (BMI;

P<0.05), whereas the women exhibited a significantly higher

serum concentration of RBV (12.6±2.1 mg/kg vs. 10.6±2.1 mg/kg;

P<0.05) and TVR (39.8±7.7 mg/kg vs. 30.6±5.6 mg/kg; P<0.01).

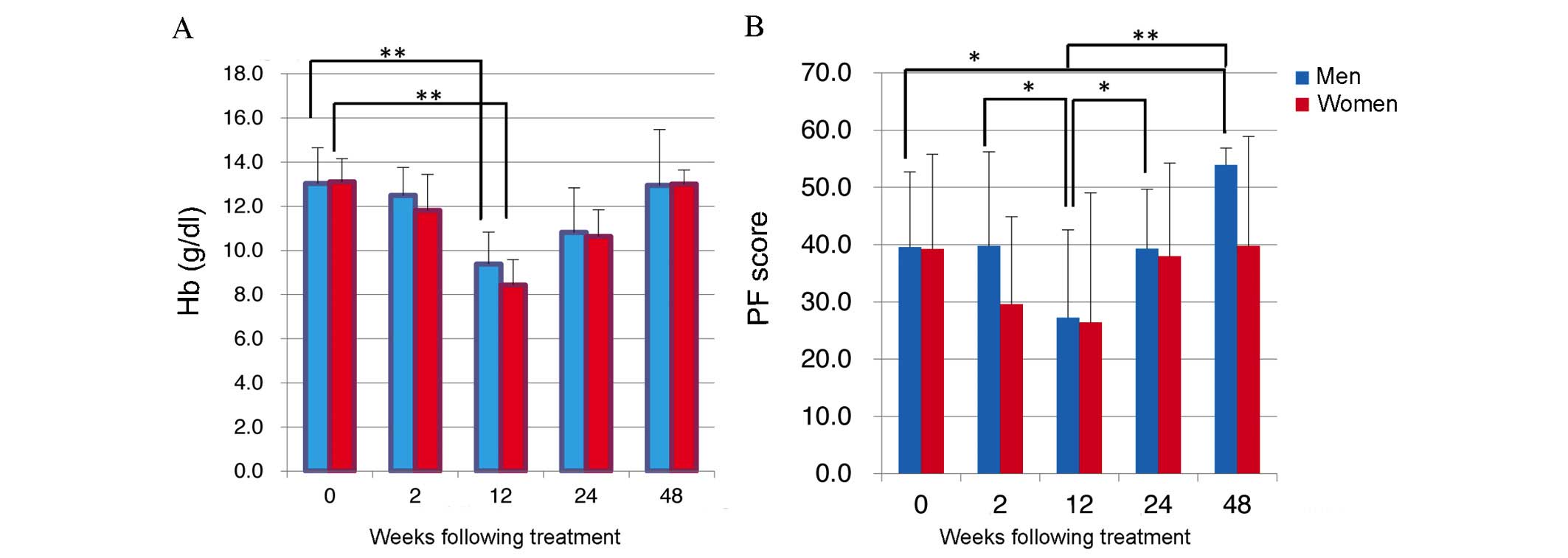

Hemoglobin (Hb) levels dropped in men and women during treatment as

SF-36 scores fell (Fig. 1A). Mean Hb

levels were 13.0±1.6 g/dl in men and 13.1±1.0 g/dl in women prior

to starting treatment, but dropped significantly to 9.4±1.4 g/dl

and 8.4±1.2 g/dl, respectively, by 12W (P<0.05; Fig. 1A). However, at 48W Hb values were

13.0±2.5 g/dl in men and 13.0±0.6 g/dl in women (Fig. 1A), indicating that baseline Hb levels

had been recovered.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to gender. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to gender.

|

| Gender |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | Male (n=18) | Female (n=16) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 62.8±10.1 | 63.6±10.4 | nsa |

| Height (cm) | 165.2±5.8 | 155±5.1 | P<0.0a |

| Weight (kg) | 66.5±9.3 | 52.7±5.8 | P<0.0a |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 24.3±2.6 | 22.0±2.6 |

P<0.05a |

| Treatment history

(no. naïve/relapse/null) | 8/9/1 | 6/10/0 | nsb |

| Serum PEG-IFN

concentration (µg/kg) | 1.55±0.2 | 1.76±0.3 | nsa |

| Serum RBV

concentration (mg/kg) | 10.6±2.1 | 12.6±2.1 |

P<0.05a |

| Serum TVR

concentration (mg/kg) | 30.6±5.6 | 39.8±7.7 |

P<0.01a |

HRQOL improved markedly following completion of

TVR-based triple treatment in complete-responders, with higher

scores compared with those prior to treatment (data not shown).

Interestingly, anemia (Hb <8 g/dl) and skin symptoms appeared

frequently during treatment, corresponding to scores for physical

functioning dropped (data not shown).

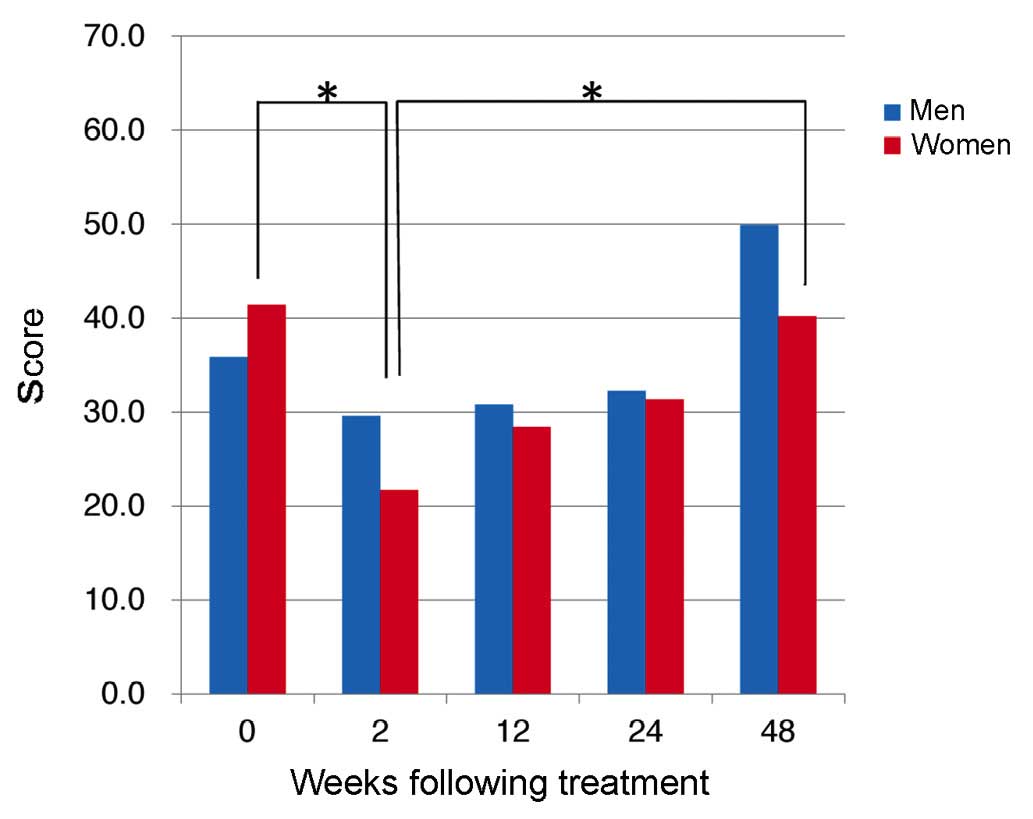

Comparison of PF scores revealed a downward trend

for men (n=18) and women (n=16) following TVR-based triple

treatment until 12W, with PF scores in men dropping significantly

from 39.8±16.4 at 2W to 27.2±15.4 at 12W (P=0.037; Fig. 1B). In addition, PF improved from 12W,

with a mean PF score in men of 53.9±3.0 at 48W, significantly

higher than the pre-treatment score of 39.6±13.1 (P=0.0009;

Fig. 2). In addition, scores for RP

dropped significantly in women between 0W and 2W (P=0.0046;

Fig. 2).

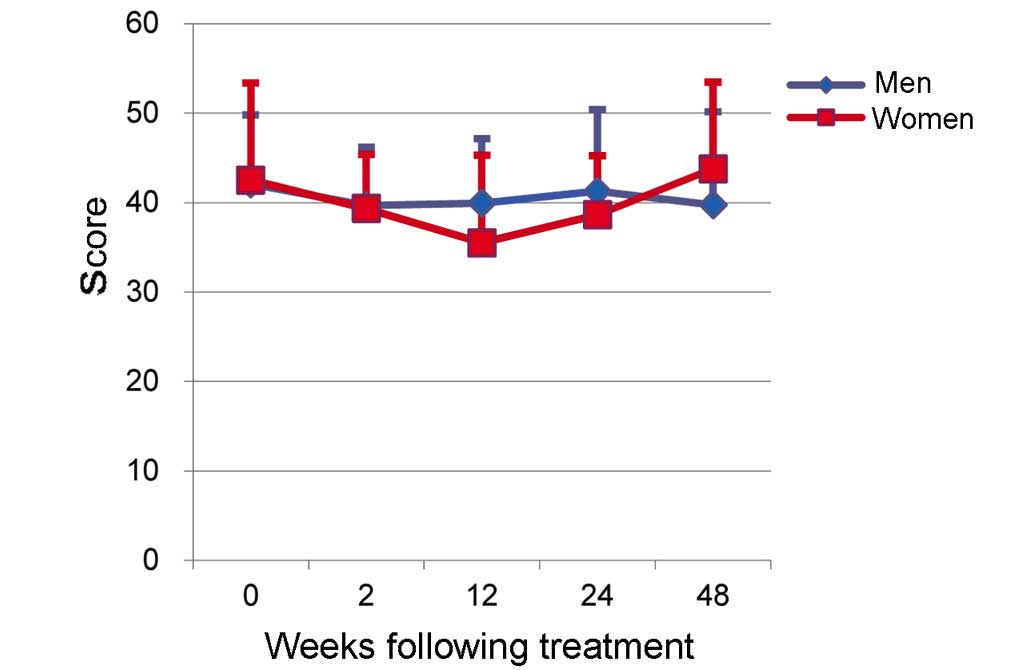

The score for MH in women was 42.5±10.8 prior to

treatment (0W) and 35.5±9.8 at 12W (Fig.

3). Although a downward trend was seen, this difference was not

significant. No significant differences in MH scores were seen

between men and women, and no effects of TVR-based treatment on MH

scores were observed (Fig. 3).

Examination on the basis of age

Patient characteristics were compared between

patients ≥65 years old (elderly group, n=19) and those <65 years

old (non-elderly group, n=15). The results of this comparison are

presented in Table II. While

significant differences in height (P<0.05) and treatment history

(P<0.01) were seen between the elderly and non-elderly groups,

no significant differences were seen in PEG-IFN, RBV or TVR

dosage.

| Table II.Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to age. |

Table II.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to age.

|

| Age |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | Non-elderly group

(<65 years old; n=15) | Elderly group (≥65

years old; n=19) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) |

52.8±4.8 | 70.4±4.9 |

P<0.01a |

| Gender

(male/female) | 8/7 | 10/9 | nsb |

|

BMI(kg/m2) | 22.9±2.6 | 23.5±3.1 | nsa |

| Height (cm) | 163.8±7.3 | 158.4±6.9 |

P<0.05a |

| Weight (kg) | 62.0±11.1 | 59.1±10.0 | nsa |

| Treatment history

(Naïve/Relapse/Null) | 10/5/0 | 4/14/1 |

P<0.01b |

| Serum PEG-IFN

concentration (µg/kg) | 1.65±0.2 | 1.64±0.3 | nsa |

| Serum RBV

concentration (mg/kg) | 11.68±1.4 | 11.3±2.8 | nsa |

| Serum TVR

concentration (mg/kg) | 36.3±7.2 | 33.6±8.6 | nsa |

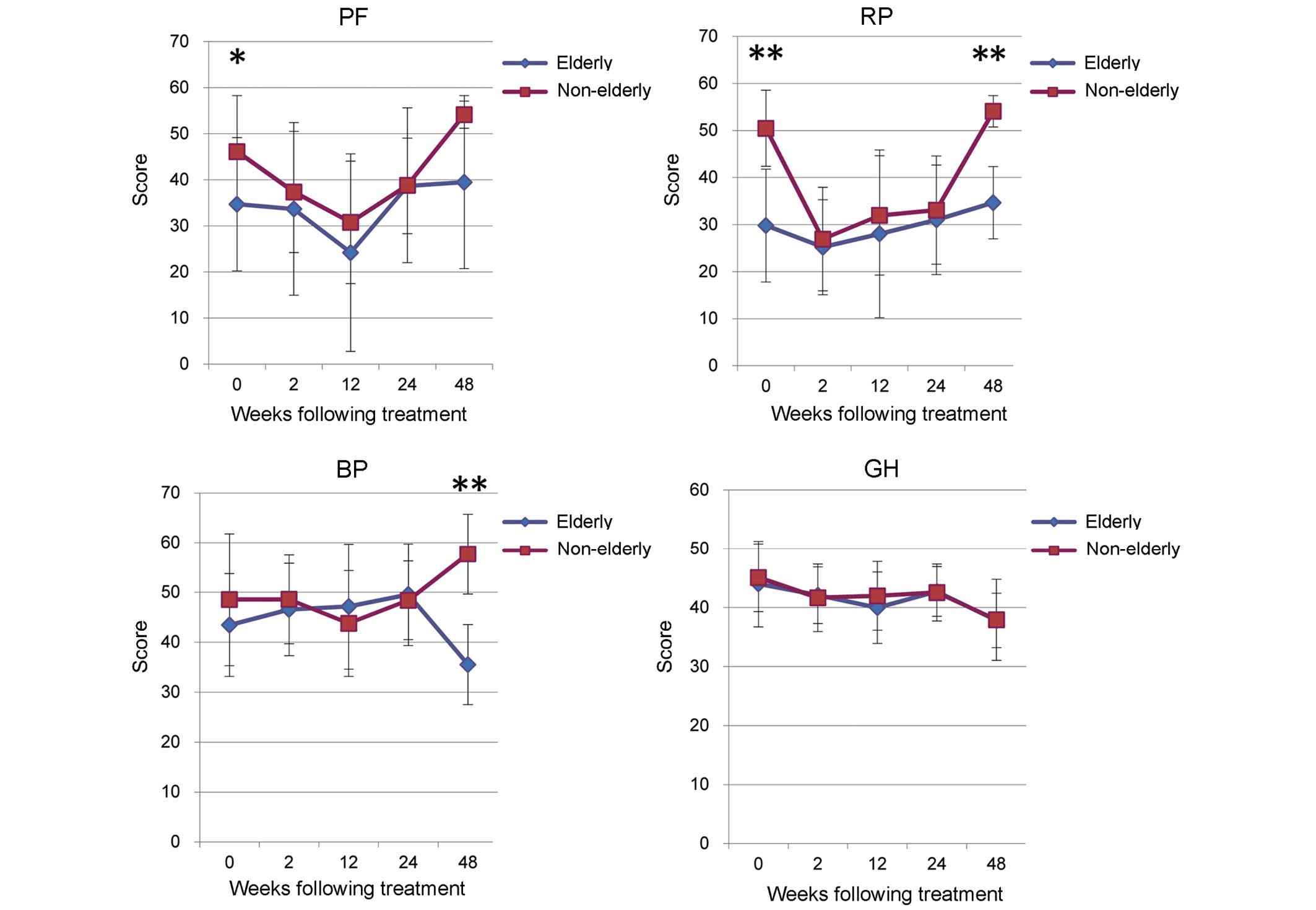

The non-elderly group exhibited significantly higher

scores in PF (P<0.05) and RP (P<0.01) prior to treatment,

which are correlated with physical health (Fig. 4). However, a drop in scores was seen

the non-elderly and elderly groups during TVR treatment (Fig. 4). A significant rise in RP score was

seen in the non-elderly group at 48W, following completion of

treatment (P<0.01; Fig. 4).

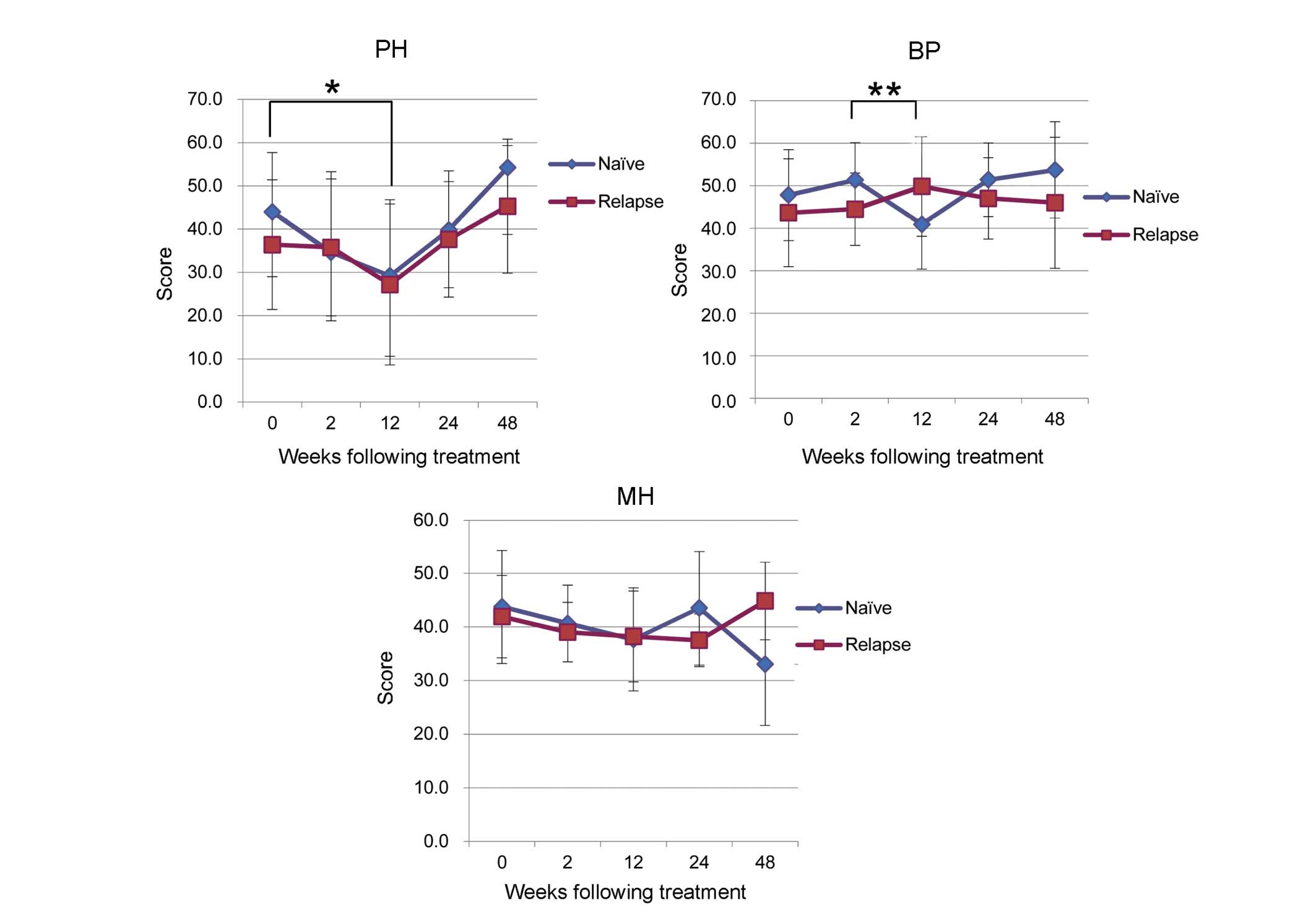

Examination on the basis of prior

treatment history

A comparison of patient characteristics according to

prior treatment history is presented in Table III. Patients were classified as

naïve (n=14), relapsed (n=19) or null responders (n=1). However,

the null responders group was excluded from this analysis. A

tendency towards low PF scores, correlated with poor physical

health, was seen in the naïve and relapse groups during TVR-based

treatment. In the naïve group, the mean PF score was 44.0±13.7

prior to treatment and decreased significantly to 29.2±17.6 between

0W and 12W (P=0.02; Fig. 5). In the

relapse group the decrease was not significant (Fig. 5). MH tended to decrease during

TVR-based treatment, however, no significant difference was seen

between groups (Fig. 5).

| Table III.Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to prior treatment history. |

Table III.

Clinical characteristics of patients

with chronic hepatitis C during TVR-based triple treatment

according to prior treatment history.

|

| Treatment

history |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Characteristic | Naïve (n=14) | Relapse (n=19) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 58.8±10.9 | 66.3±8.7 | nsa |

| Gender

(male/female) | 8/6 | 9/10 | nsb |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 22.7±2.9 | 23.6±2.9 | nsa |

| Height (cm) | 163.4±7.25 | 158.5±7.4 | nsa |

| Weight (kg) | 60.7±9.8 | 59.7±11.4 | nsa |

| Serum PEG-IFN

concentration (µg/kg) | 1.7±0.2 | 1.6±0.4 | nsa |

| Serum RBV

concentration (mg/kg) | 11.0±1.7 | 11.8±2.7 | nsa |

| Serum TVR

concentration (mg/kg) | 35.7±6.8 | 34.1±9.2 | nsa |

Discussion

CHC infection may be associated with a considerable

reduction in HRQOL, regardless of the disease stage (12–15).

However, the precise mechanism of decreased HRQOL in patients with

CHC has not been elucidated, although there are a number of reports

indicating an association between the degree of fibrosis, gender

and age (16,17).

IFN treatment requires long-term outpatient

treatment, making QOL evaluations essential. IFN-free hepatitis C

treatment has now been approved (18) and is being actively implemented.

However, QOL evaluations prior to and following IFN treatment

remain important, even in this era of IFN-free treatment.

HRQOL evaluations include comprehensive

health-related and disease-specific assessments. Comprehensive

HRQOL evaluations include the SF-36, developed in the United States

and used worldwide. A Japanese version, developed by Fukuhara et

al (10), is used in various

fields in Japan and reports of its usefulness have emerged

(10,11). The SF-36 allows patients to

quantitatively self-evaluate their physical and emotional QOL with

relative ease. The SF-36 is a multidimensional, comprehensive QOL

measure comprising of 36 items covering 8 areas, which are related

to physical or emotional health. Each of the 8 areas contains 2–5

levels of questions that are scored on an ordinal scale, allowing

the patient to understand their health from multiple aspects and

evaluate their QOL. Each of the 8 areas was scored on a scale of

0–100, where a higher score indicated better health

subjectively.

A systematic review by Spiegel et al

(19) found 15 studies that compared

the HRQOL of patients with hepatitis C virus (seropositive) with

healthy controls, which identified a decrease in weighted mean

SF-36 scores including PF and RP. Previous studies have reported a

decreased HRQOL in 6 SF-36 areas in patients with CHC compared with

patients without CHC, particularly in VT, GH and RP (20,21). In

the current study, patients with CHC undergoing TVR-based treatment

exhibited significantly lower SP-36 scores in 5 areas (PF, RP, BP,

GH and MH), indicating a decrease in their HRQOL. The results of

the current study are in agreement with previous studies comparing

the HRQOL of patients with CHC patients prior to and following

antiviral treatment (IFN or IFN/RBV) (22,23).

In the current study, SF-36 scores dropped in

conjunction with the progression of anemia and were lowest at 12W.

It is important to assess subjective symptoms with the SF-36 early

and to adjust dosages accordingly, in order to minimize the number

of patients who drop out of treatment, improve therapeutic efficacy

and maintain patient QOL. Furthermore, the findings of the current

study suggest that anemia is an important factor in maintaining

QOL, highlighting the importance of controlling drug dosage during

treatment.

A number of improvements have been made to IFN

treatment in recent years, enhancing its therapeutic effects and

increasing the patient response rate. In the present study, the

negative effects of TVR-based triple treatment on HRQOL were

stronger in regards to physical health compared with emotional

health. This is because PF scores decreased until 12W, but then

followed an upward trend, which may be the result of the side

effects of TVR decreasing. Conversely, PF scores, which correlate

strongly with physical health, tended to exceed scores from prior

to treatment (0W) by 48W, regardless of gender, age or treatment

history. This suggests that TVR-based triple treatment improves

physical HRQOL, which is likely associated with a SVR. In further

studies, the HRQOL in patients with IFN vs. IFN-free treatment will

be investigated.

In conclusion, the present study evaluated HRQOL,

using the SF-36, in patients with CHC during TVR-based triple

treatment. Surveys using the SF-36 offer a useful indicator of

patient QOL, which may be used to reduce the number of patients who

discontinue treatment and to improve IFN treatment in the

future.

References

|

1

|

McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC,

Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, McNair L, Alam J and Muir AJ:

PROVE1 Study Team: Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for

chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 360:1827–1838.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hézode C, Forestier N, Dusheiko G, Ferenci

P, Pol S, Goeser T, Bronowicki JP, Bourlière M, Gharakhanian S,

Bengtsson L, et al: Telaprevir and peginterferon with or without

ribavirin for chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 360:1839–1850.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

McHutchison JG, Manns MP, Muir AJ,

Terrault NA, Jacobson IM, Afdhal NH, Heathcote EJ, Zeuzem S,

Reesink HW, Garg J, et al: Telaprevir for previously treated

chronic HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 362:1292–1303. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kinder M: The lived experience of

treatment for hepatitis C. Gastroenterol Nurs. 32:401–408. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Liu J, Lin CS, Hu SH, Liang ML, Zhao ZX

and Gao ZL: Quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C

after PEG-Interferon a-2a treatment. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi.

19:890–893. 2011.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Marcellin P, Chousterman M, Fontanges T,

Ouzan D, Rotily M, Varastet M, Lang JP, Melin P and Cacoub P:

CheObs Study Group: Adherence to treatment and quality of life

during hepatitis C therapy: A prospective, real-life, observational

study. Liver Int. 31:516–524. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M and Gandek B:

SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. The Health

Institute, New England Medical Center; Boston, MA: 1993

|

|

8

|

Aaronson NK, Acquadro C, Alonso J, Apolone

G, Bucquet D, Bullinger M, Bungay K, Fukuhara S, Gandek B and

Keller S: International quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project.

Qual Life Res. 1:349–351. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ware JE Jr and Gandek B: Overview of the

SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life

assessment (IQOLA) project. J Clin Epidemiol. 51:903–912. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fukuhara S, Bito S, Green J, Hsiao A and

Kurokawa K: Translation, adaptation, and validation of the SF-36

health survey for use in Japan. J Clin Epidemiol. 51:1037–1044.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fukuhara S and Suzukamo Y: Manual of

SF-36v2 Japanese version. Institute for Health Outcomes and Process

Evaluation Research; Kyoto: 2004

|

|

12

|

Foster GR, Goldin RD and Thomas HC:

Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction

in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology.

27:209–212. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rodger AJ, Jolley D, Thompson SC, Lanigan

A and Crofts N: The impact of diagnosis of hepatitis C virus on

quality of life. Hepatology. 30:1299–1301. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Strauss E and Teixeira MC Dias: Quality of

life in hepatitis C. Liver Int. 26:755–765. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Younossi Z, Kallman J and Kincaid J: The

effects of HCV infection and management on health-related quality

of life. Hepatology. 45:806–816. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Bonkovsky HL, Snow KK, Malet PF,

Back-Madruga C, Fontana RJ, Sterling RK, Kulig CC, Di Bisceglie AM,

Morgan TR, Dienstag JL, et al: Health-related quality of life in

patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced fibrosis. J Hepatol.

46:420–431. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Teuber G, Schäfer A, Rimpel J, Paul K,

Keicher C, Scheurlen M, Zeuzem S and Kraus MR: Deterioration of

health-related quality of life and fatigue in patients with chronic

hepatitis C: Association with demographic factors, inflammatory

activity, and degree of fibrosis. J Hepatol. 49:923–929. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J,

Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ido A, Yamamoto K, Takaguchi K, et

al: Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b

infection. Hepatology. 59:2083–2091. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Spiegel BM, Younossi ZM, Hays RD, Revicki

D, Robbins S and Kanwal F: Impact of hepatitis C on health related

quality of life: A systematic review and quantitative assessment.

Hepatology. 41:790–800. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Björnsson E, Verbaan H, Oksanen A, Frydén

A, Johansson J, Friberg S, Dalgård O and Kalaitzakis E:

Health-related quality of life in patients with different stages of

liver disease induced by hepatitis C. Scand J Gastroenterol.

44:878–887. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kwan JW, Cronkite RC, Yiu A, Goldstein MK,

Kazis L and Cheung RC: The impact of chronic hepatitis C and

co-morbid illnesses on health-related quality of life. Qual Life

Res. 17:715–724. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kang SC, Hwang SJ, Lee SH, Chang FY and

Lee SD: Health-related quality of life and impact of antiviral

treatment in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis C in Taiwan.

World J Gastroenterol. 11:7494–7498. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Hollander A, Foster GR and Weiland O:

Health-related quality of life before, during and after combination

therapy with interferon and ribavirin in unselected Swedish

patients with chronic hepatitis C. Scand J Gastroenterol.

41:577–585. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|