Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) chronically infects ~180

million people worldwide, and is a frequent cause of liver

diseases, including liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma

(1,2). The seroprevalence of hepatitis C

infection in the general population of China is estimated to be

0.8–2.1% (3). The rate is much

higher in certain subgroups such as injecting drug users or

subjects with hemophilia (3).

The discovery of direct-acting antiviral agents

(DAAs) in 2002 led to the development of small molecules to block

the replication of HCV, including novel antiviral targets (4,5). Based

on the impressive improvements in sustained virologic response

(SVR) rates in phase III trials (6),

the first two protease inhibitors telaprevir and boceprevir were

recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, and are

currently recommended first line agents for genotype 1 infections.

However, while they are generally well-tolerated, adverse events

are common, and the agents are very expensive. Furthermore, triple

therapy is not approved for use in non-genotype 1 HCV infections,

and there are numerous drug-drug interactions that preclude their

use. Prior to the development of triple therapy, peginterferon α-2b

or peginterferon α-2a alone, or in combination with weight-based

ribavirin had been the standard treatment chronic hepatitis C

resulting in SVRs of 30 and 50% (7,8)

respectively, for genotype 1 cases, and 80% for genotypes 2 and 3

(9–12).

Two polyethylene glycol (PEG)-modified interferons,

interferon (IFN)-α-2a containing a branched 40-kD PEG molecule

(PEGASYS®; F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., Basel,

Switzerland) and IFN-α-2b containing a linear 12-kD PEG molecule

(PEG-INTRON®; Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ,

USA) are currently on the market. However, side effects are quite

problematic, and the efficacy of PEG-IFN monotherapy is limited.

Consensus interferon (CIFN) was designed in order to maximize

efficacy, and minimize side effects. It is composed of the most

frequently observed amino acids in each corresponding position in

the natural α IFNs. CIFN shares an 89, 30, and 60% homology with

IFN-α, IFN-β and IFN-ω, respectively (13). CIFN has been shown to be efficacious

in HCV genotype 1 patients who have failed therapy with PEG-IFN

(14). In order to increase the

duration of action, recombinant human CIFN was PEG-modified

(pegylated) by Chongqing Fujin Biomedical Co., Ltd. (Chongqing,

China). Compared with naturally occurring IFN-α, PEG-CIFN has

demonstrated enhanced in vivo antiviral activity in

cynomolgus monkeys; serum sample analyses from PEG-CIFN-treated

monkeys showed a dose-dependent antiviral activity (15). The PEG-CIFN investigated in the

current study was produced by the covalent attachment of a single

20-kDa methoxypolyethylene glycol-propionaldehyde molecule to the

N-terminus of IFN, forming a molecule with an average molecular

weight of ~40 kDa. This modification results in a longer half-life

and sustained antiviral action (15). PEG-CIFN has exhibited improved

pharmacokinetic properties compared with CIFN in monkeys and rats,

with 12- and 15-fold increases in elimination half-life, and 100-

and 10-fold reductions in serum clearance, as well as a 2.5- and

10-fold increases in the time to reach peak serum concentrations,

respectively (15).

In vitro studies have shown that the

antiviral mechanism of action of PEG-CIFN is identical to that of

CIFN: Competitive inhibition of virus binding with receptors on

target cells. Therefore, damage to target cells can be minimized.

Studies in animals have suggested that PEG-CIFN has significant

antiviral activity (16). The aim of

the current study was to determine the tolerability and antiviral

activity of PEG-CIFN in adults with HCV infection.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Forty-eight subjects from Jilin province, China were

enrolled in the study, and the characteristics of the subjects are

shown in Table I.

| Table I.Characteristics of the study

subjects. |

Table I.

Characteristics of the study

subjects.

| Characteristic | Peginterferon α-2a

(Pegasys) | PEG-CIFN 1.0

µg/kg | PEG-CIFN 1.5

µg/kg | PEG-CIFN 2.0

µg/kg | PEG-CIFN 3.0

µg/kg |

|---|

| Male/female

ratio | 7/2 | 5/5 | 7/3 | 6/3 | 8/2 |

| Age (years, mean ±

SD) | 46.56±8.82 | 46.60±12.55 | 51.90±9.15 | 48.44±7.28 | 44.60±3.57 |

| Body mass index

(kg/m2, mean ± SD) | 23.38±2.62 | 23.83±2.16 | 23.92±1.87 | 22.64±2.28 | 22.83±2.82 |

| AST (IU/l, mean ±

SD) | 47.11±24.60 | 35.85±16.46 | 42.90±22.53 | 45.22±34.56 | 30.60±11.28 |

| ALT (IU/l, mean ±

SD) | 80.11±58.67 | 52.90±29.18 | 58.50±38.43 | 53.44±40.93 | 49.00±27.07 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl,

mean ± SD) | 159.88±12.18 | 141.40±14.10 | 157.80±12.55 | 149.00±11.98 | 159.30±17.73 |

| White blood cells

(/mm3, mean ± SD) | 5.81±0.91 | 4.54±2.25 | 6.44±1.81 | 6.82±1.77 | 5.59±0.98 |

| Platelet count

(/mm3, mean ± SD) | 171.50±31.92 | 161.25±58.70 | 181.80±43.57 | 175.22±51.00 | 185.6±38.28 |

| Genotype (n) |

|

|

|

|

|

| 1b | 2 | 10 | 6a | 2 | 10 |

| 2a | 7 | 0 | 5 | 7b | 0 |

| Viral count

(log10IU/l, mean ± SD) | 5.90±1.12 | 6.58±0.59 | 6.27±0.95 | 6.65±0.63 | 6.50±0.74 |

| Fibroscan | 7.83±4.12 | 6.36±2.45 | 7.20±5.75 | 6.46±2.09 | 6.36±2.45 |

Inclusion criteria: Eligible subjects were 18–65

years old, with compensated liver disease due to chronic HCV

infection, plasma HCV RNA levels >2,000 IU/ml, and no history of

previous anti-HCV treatment, an absolute neutrophil count

>1,500/ml3, a platelet (PLT) count of

>90,000/mm3 and hemoglobin levels of >12 g/dl (for

women) or >13 g/dl (for men), body mass index (BMI) between 18

and 26 kg/m2 and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level

<240 IU/l.

Exclusion criteria: Co-infection with human

immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis B, any other cause of liver

disease, severe depression or a severe psychiatric disorder, active

drug or alcohol abuse, liver cirrhosis, or hepatocellular

carcinoma, abnormal serum creatinine level, serum total bilirubin

level >34.2 µmol/l or serum albumin <35 g/l.

This clinical trial was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University (Jilin, China).

All subjects provided signed informed consent prior to

enrollment.

Study design

The 48 adult subjects infected with HCV were divided

into five groups. The first group received weekly PEG-CIFN by

subcutaneous injections at a dose of 1.0 µg/kg, and were observed

for 4 weeks. If the subjects tolerated the dose, the next groups

received 1.5 and 2.0 µg/kg PEG-CIFN weekly for 14 weeks, but were

not given drug at weeks 2 and 14 due to pharmacokinetic

experiments. Therefore, in total the patients received 12 doses of

PEG-CIFN monotherapy. One group received the maximum dose of

PEG-CIFN (3.0 µg/kg) only to evaluate tolerance according to the

protocol. Pegylated IFNα-2a (peginterferon α-2a; Pegasys) was

administered at a dose of 180 µg using the same treatment protocol

as the PEG-CIFN groups and served as a positive control.

Safety was assessed by physicians of the First

Hospital of Jilin University, at weeks 2, 4 and 8 or other

(emergency) visits. If >50% of subjects had any of the following

adverse events, the dose escalation was terminated: Absolute

neutrophil count (ANC) <0.5×109/l, PLT count

<30×109/l, ALT >400 IU/l, persistent ALT rise or

accompanied by bilirubin elevation after dose titration, serum

total bilirubin >51.3 µmol/l, development of ascites, hepatic

encephalopathy, or psychiatric disorders, allergic reactions,

uncontrolled thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, serious damage to

the heart, kidney, brain, lung, etc.

If a serious adverse event occurred during the

course of treatment, we discontinued or modified the dosage of

PEG-CIFN until the adverse event abated or decreased in severity.

The process for dose reduction consisted of two-steps. If the ANC

or PLT count was 0.5×109-0.75×109/l or

30×109-50×109/l, respectively, the treatment

dose of PEG-CIFN was reduced. If the ANC or PLT count fell below

0.5×109/l or 30×109/l, respectively, the drug

was discontinued. Drug doses could be increased once the cytopenia

resolved (when the ANC was ≥0.75×109/l or the PLT count

was ≥50×109/l).

Study drugs

PEG-CIFN was developed by Chongqing Fujin Biomedical

Co., Ltd., and produced by Beijing Kain Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd. (Beijing, China). Peginterferon α-2a was produced by F.

Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc. Agents were stored until use under

conditions recommended by the manufacturers.

Follow-up

The subjects were monitored every week by physical

examination, vital signs, inquiries of adverse reactions and weight

measurements. At weeks 4, 8 and 14, HCV RNA levels were measured by

quantitative polymerase chain reaction using the COBAS TaqMan HCV

test (Roche Molecular Systems, Pleasanton, CA, USA), which has a

low limit of quantitation (15 IU/ml). Complete blood cell counts

were measured weekly and drug dosages adjusted accordingly for

abnormalities in hemoglobin levels, ANC and PLT count. Subjects

were randomly assigned to groups. If subjects missed more than one

follow-up visit, those persons were considered non-compliant and

were removed from the study. Evaluation of tolerability index test

results for PEG-CIFN and peginterferon α-2a groups were compared

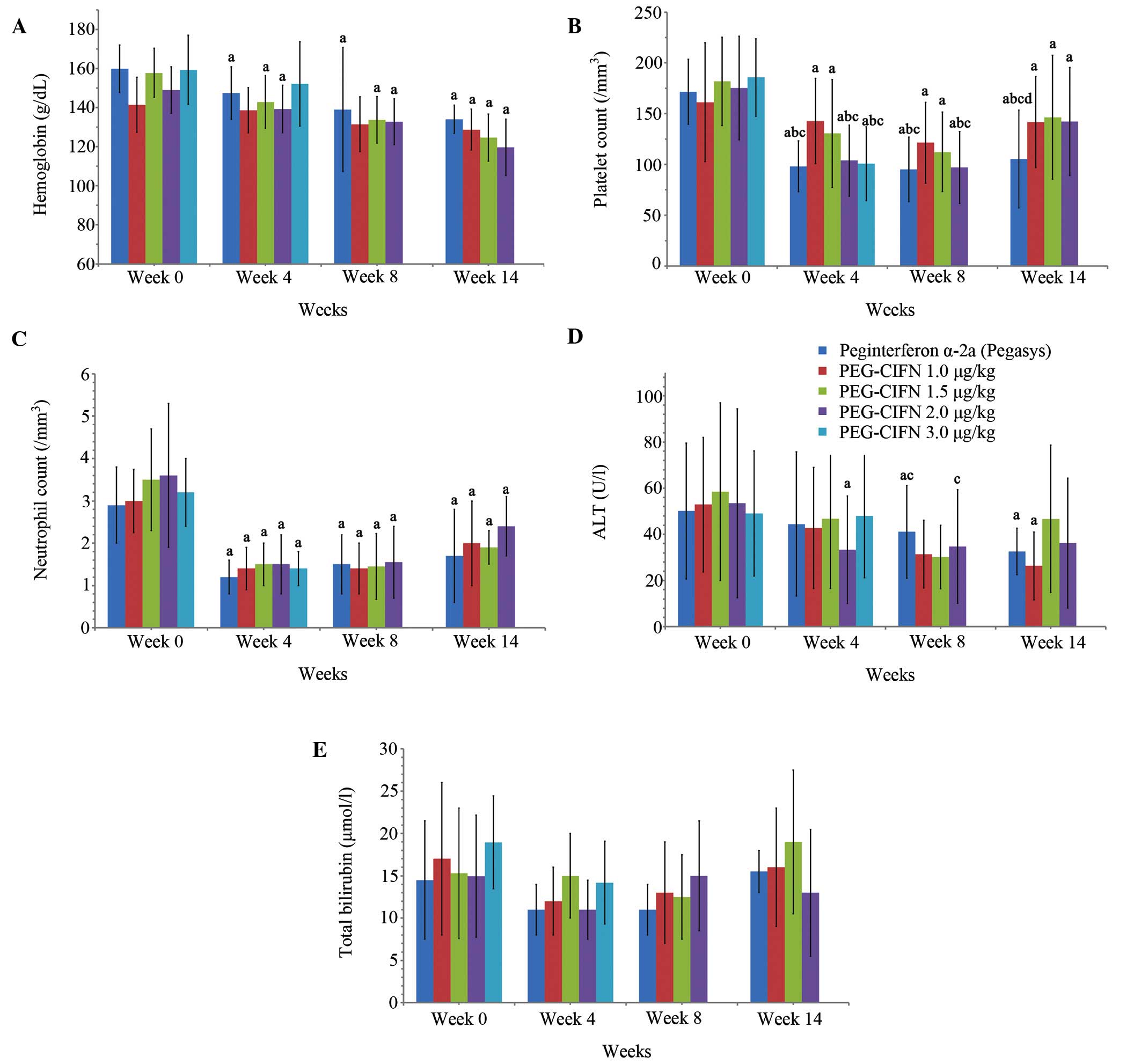

with the same dose group at week 0 (Fig.

1).

Efficacy

The primary efficacy criterion was the percentage of

subjects whose HCV RNA levels were undetectable at week 14 [early

virologic response (EVR) after 12 doses of PEG-CIFN]. The secondary

efficacy criterion was the percentage of subjects whose HCV RNA

levels were undetectable at week 4 and after a further 3 doses of

PEG-CIFN at week 8. Reductions in HCV RNA levels at weeks 4, 8 and

14 were expressed as log10.

Statistical analysis

The results were analyzed with analysis of variance

tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests using SAS software, version 9.0 (SAS

Institute, Cary, NC, USA). The results were presented as means ±

standard deviations. Multivariable logistic regression analyses

involving age, gender, baseline HCV RNA levels, baseline ALT

levels, baseline aspartate aminotransferase levels, BMI and

treatment regimens were performed to determine virologic responses

at weeks 4, 8 and 14. Virologic response was defined as an

undetectable HCV RNA level (<15 IU/ml). P<0.05 in two-sided

tests were considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The study enrolled 48 HCV-infected subjects of whom

15 subjects were female (31.2%). The average age of the patients

was 47.4 years, ranging from 20 to 65 years. There were no

significant differences between the dose groups at baseline for any

of these characteristics (Table

I).

Tolerance

PLT counts

The PLT counts of each group decreased from the

baseline to week 8, and then began to rebound at week 9. The PLT

counts of all PEG-CIFN dose groups were significantly higher than

that of the peginterferon α-2a group at weeks 4, 8 and 14. Actual

numbers and percentage changes are listed in Table II.

| Table II.Evaluation of tolerability results

for the PEG-CIFN and Peg interferonα-2a groups. |

Table II.

Evaluation of tolerability results

for the PEG-CIFN and Peg interferonα-2a groups.

| Evaluation

index | Time (week) | Peginterferon α-2a

(n=9) | PEG-CIFN 1.0 µg/kg

(n=10) | PEG-CIFN 1.5 µg/kg

(n=10) | PEG-CIFN 2.0 µg/kg

(n=9) | PEG-CIFN 3.0 µg/kg

(n=10) |

|---|

| Hemoglobin <100

g/dl, | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| n (%) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| 8 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

|

| 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| ANC <0.75 and

>0.5/mm3, | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| n (%) | 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.11) | 0 (0) |

|

| 8 | 1 (11.11) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

|

|

| 14 | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| Platelet

count, | 0 | 171.50±31.92 | 161.25±58.70 | 181.80±43.57 | 175.22±51.00 | 185.6±38.28 |

| /mm3,

mean ± SD | 4 | 98.11±25.10 |

142.70±42.05a |

130.40±53.18a |

103.78±35.13a |

100.80±36.41a |

|

| 8 |

95.11±31.80a |

121.40±39.79a |

112.30±39.27a |

97.00±35.40a |

|

|

| 14 |

105.33±48.07a,b |

141.80±44.98a,c,d |

146.50±60.92a,c,e |

142.30±53.21a,c,f |

|

| ALT | 0 |

110.11±37.34a | 52.90±29.18 | 58.50±38.43 |

53.44±40.93 | 49.00±27.07 |

| IU/l, mean ±

SD | 4 | 80.11±58.67 |

42.80±26.28a |

46.80±30.29a |

33.33±23.36a |

|

|

| 8 |

44.44±30.82a |

31.40±14.70a | 66.60±30.57 |

34.78±24.60a |

|

|

| 14 |

41.11±16.80a |

26.33±14.65a |

46.70±31.97a |

36.20±28.14a |

|

| Total

bilirubin>34.2 µmol/l, | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| n (%) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

|

|

| 8 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

|

| 14 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

It was observed that the thrombocytopenic effect of

PEG-CIFN was more moderate compared with that of peginterferon α-2a

(180 µg) group. Therefore, subjects with cirrhosis and

pre-treatment thrombocytopenia may be more suitably treated with

PEG-CIFN rather than with the currently approved pegylated IFNs.

However, even in the PEG-CIFN groups, PLT counts decreased until

week 8, and then became relatively stable. This suggests that the

clinical observation time should be extended from to 4 to 8 weeks

(16).

Hemoglobin levels

The hemoglobin levels in each group remained >100

g/dl. None of the groups required adjustments in dosage due to

anemia.

Neutrophil counts

ANCs at weeks 4, 8 and 14 were significantly lower

than that at baseline (P<0.05). There were no statistically

significant differences in ANCs between any dose group at baseline,

and weeks 4, 8 and 14.

At weeks 4, 8 and 14, there were 5 subjects whose

ANCs were <0.75/mm3 but >0.5/mm3 in the

PEG-CIFN 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 µg/kg groups and the peginterferon α-2a

group combined. According to the protocol, their doses were reduced

by 25%. After 1 week, the neutrophil counts rose to

>0.75×109/l. Original doses were then

re-instated.

PLT counts and ANCs decreased following the

initiation of treatment, and then slowly rose with increasing

treatment time or dose adjustment. The rebound in counts was

significant in all PEG-CIFN groups compared with the peginterferon

α-2a group.

Total bilirubin levels

Total bilirubin levels did not change significantly

between any group at any time point.

Fibroscan values

Fibroscan values were tested at screening and week

14 of the study. FibroScan use the vibration control of the

instantaneous elastic imaging to assess the hardness of the liver.

The larger the value of elasticity, the greater the value of liver

tissue hardness. For viral hepatitis, fibrosis was staged on a

scale as follows: F2 (stiffness 0–7.3 kPa); F2-F3 (stiffness

7.3–12.4 kPa); F3-F4 (stiffness 12.4–17.5 kPa) and ≥F4 (stiffness

≥17.5 kPa). In the PEG-CIFN 2.0 µg/kg group, the Fibroscan values

increased significantly compared with that at baseline (P<0.05).

There were no statistically significant differences between the

baseline value and the value at week 14 in any of the other dose

groups.

Ophthalmologic complications

It has been reported that IFN-associated retinopathy

occurs in 15–64% of IFN-treated patients (17). In the current study, it was found

that 35.4% of subjects had ocular adverse reactions. These were

mostly mild or moderate and gradually diminished. These events

consisted of papilledema (5 subjects), retinopathy (5 subjects),

arteriosclerosis (5 subjects), intraocular pressure and fundus

cup-disc ratio, C/D≥0.5 (2 subjects).

Other adverse events

Adverse reactions were monitored and recorded

weekly. Common adverse reactions were fatigue, poor appetite,

feverishness, musculoskeletal pain, hair loss and depression. The

incidence of the majority of the psychiatric and physical adverse

events increased with increasing doses of PEG-CIFN, and they were

higher than those of the pegylated IFN-2a group. All the events

were mild or moderate and did not result in discontinuation of

treatment.

The incidence of adverse reactions increased with

increasing dose (Table III). The

incidence of adverse reactions was highest in the 3.0 µg/kg group,

and some adverse reactions occurred in all participants in this

group (100%).

| Table III.Common adverse reactions [n (%)]. |

Table III.

Common adverse reactions [n (%)].

| Event | PEG-CIFN 1.0 µg/kg

(%) | PEG-CIFN 1.5 µg/kg

(%) | PEG-CIFN 2.0 µg/kg

(%) | PEG-CIFN 3.0 µg/kg

(%) | Peginterferon α-2a

(%) |

|---|

| Fatigue | 5 (50) | 3 (30) | 9 (100) | 10 (100) | 4 (40) |

| Headache | 5 (50) | 3 (30) | 8 (88.9) | 8 (80) | 5 (50) |

| Insomnia | 1 (10) | 1 (10) | 2 (22.2) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) |

| Feverishness | 2 (20) | 2 (20) | 3 (33.3) | 8 (80) | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal

pain | 7 (70) | 5 (50) | 6 (66.7) | 10 (10) | 5 (50) |

| Xerostomia | 6 (60) | 4 (40) | 9 (100) | 10 (100) | 5 (50) |

| Injection site

reaction | 0 | 4 (40) | 9 (100) | 9 (90) | 0 |

| Indigestion | 0 | 0 | 2 (22.2) | 0 | 1 (10) |

| Flu-like

symptoms | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 | 4 (40) | 0 |

| Poor appetite | 0 | 7 (70) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (30) | 1 (10) |

| Hair loss | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (40) | 1 (10) |

| Depression | 3 (30) | 0 (0) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

Efficacy

Virologic response

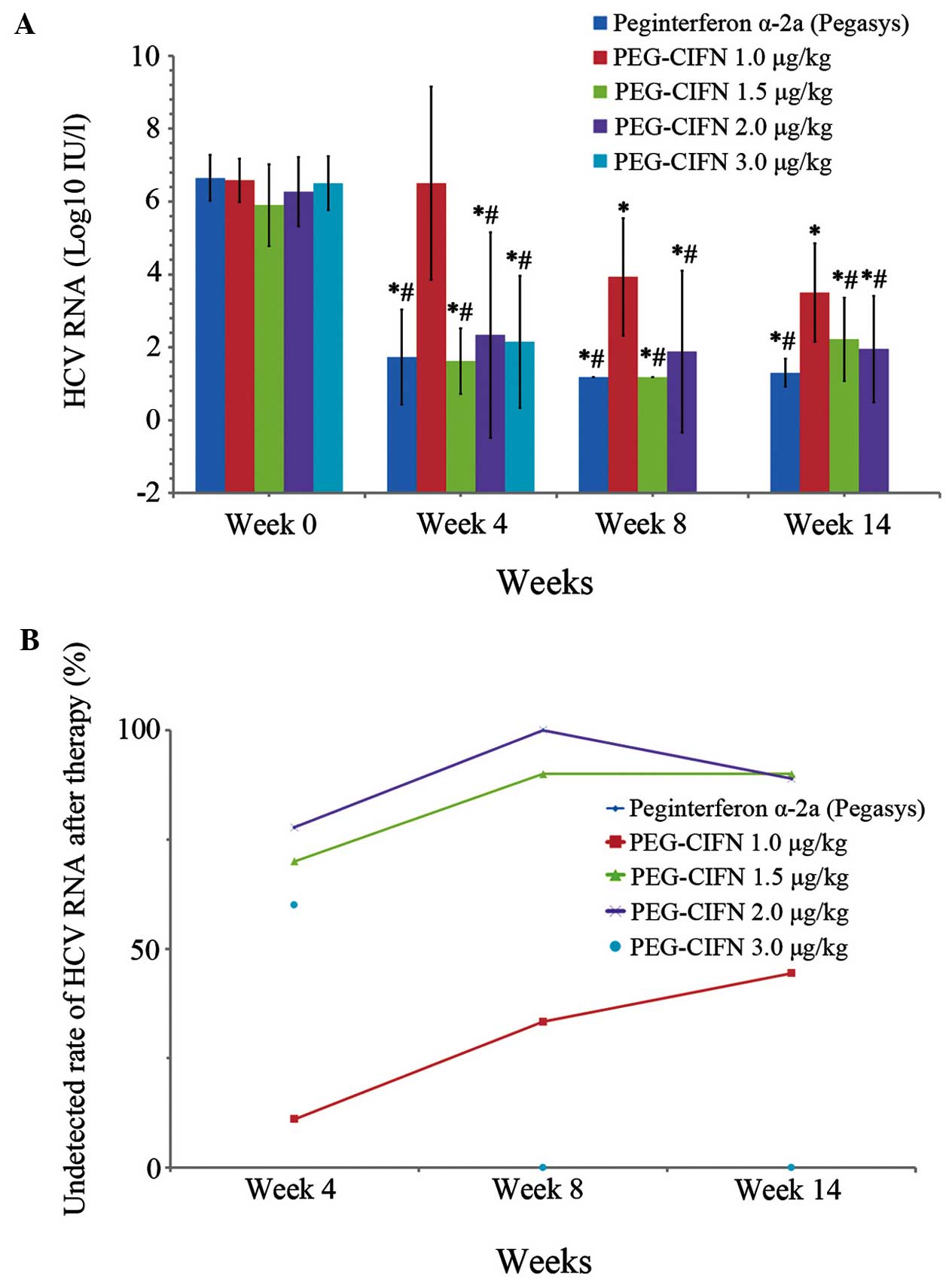

There were no significant differences in baseline

HCV RNA levels between any of the groups (Table IV). Serum HCV RNA levels decreased

significantly at weeks 4, 8 and 14 for all groups compared with

baseline (P<0.05; Fig. 2).

| Table IV.Baseline HCV RNA levels in the

treatment groups. |

Table IV.

Baseline HCV RNA levels in the

treatment groups.

| Group | n | HCV RNA level

(log10IU/l, mean ± SD) |

|---|

| Peginterferon

α-2a | 9 | 5.90±1.12 |

| PEG-CIFN 1.0

µg/kg | 10 | 6.58±0.59 |

| PEG-CIFN 1.5

µg/kg | 10 | 6.27±0.95 |

| PEG-CIFN 2.0

µg/kg | 9 | 6.65±0.63 |

| PEG-CIFN 3.0

µg/kg | 10 | 6.50±0.74 |

The RVR rates for the PEG-CIFN 1.5, 2.0 and 3.0

µg/kg groups and for the peginterferon α-2a group were 70% (7/10),

77.8% (7/9), 60% (6/10) and 77.8% (7/9), respectively. These rates

were all significantly higher than that in the PEG-CIFN 1.0 µg/kg

group (10%, 1/10) (P<0.05).

At week 8, the extended RVR rates of the PEG-CIFN

1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 µg/kg groups and for the peginterferon α-2a group

were 10% (1/10), 70% (7/10), 77.8% (7/9) and 66.7% (6/9),

respectively.

At week 8, the HCV RNA levels decreased rate for the

PEG-CIFN 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 µg/kg groups and for the peginterferon

α-2a group were 30% (3/10), 90% (9/10), 88.8% (8/9) and 88.8%

(8/9), respectively.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were

performed to study the virologic responses. The virologic responses

at weeks 4, 8 and 14 were higher for the PEG-CIFN 1.5 and 2.0 µg/kg

groups and for the peginterferon α-2a group than that for the

PEG-CIFN 1.0 µg/kg group. There was no difference in virologic

response between the peginterferon α-2a and PEG-CIFN 2.0 µg/kg

groups at weeks 4 and 8. Virologic response rates increased with

increasing duration of drug administration.

Biochemical response

There were no statistically significant differences

in ALT levels between any dose groups at baseline, or at weeks 4, 8

or 14. The ALT levels were observed to decrease as the duration of

treatment increased, with no significant differences among all

values in the same dose group (P>0.05).

Discussion

In the past, treatment with pegylated IFN α-2a or

pegylated IFN α-2b, plus ribavirin, for 48 weeks was recommended

for patients infected with HCV genotype 1, the most common genotype

in the United States and Europe (18). By contrast, patients infected with

HCV genotypes 2 or 3 may be treated with ribavirin (800 mg/day) and

for just 24 weeks without compromising efficacy. These findings are

reflected in treatment guidelines for chronic hepatitis C (19,20). The

discovery of protease inhibitors as DAAs in 2002 led to the

development of numerous small molecules that block the replication

of HCV at novel antiviral targets (4,5). In

patients with HCV genotype 2 or 3 infection for whom treatment with

peginterferon and ribavirin was not an option, 12 or 16 weeks of

treatment with sofosbuvir and ribavirin was found to be effective

in early studies (21). Triple

therapy including direct-acting antiviral agents, other than

protease inhibitors, combined with pegylated IFN α-2a or pegylated

IFN α-2b, plus ribavirin) are showing promising results in clinical

trials. The possibility of decreased side effects and tolerability

with the same efficacy for PEG-CIFN indicate that it may play a

role in combination with new direct acting agents in the

future.

The virologic response rate for genotype 1 HCV

treated with dual therapy (pegylated IFN combined with ribavirin)

has been reported to be between 30 and 50% (7,8). In the

current study, the RVR rate at week 4 was 10% in the PEG-CIFN 1.0

µg/kg group, but 60% in the PEG-CIFN 3.0 µg/kg group. These results

suggest that the higher dose of PEG-CIFN may be the optimal dose

for genotype 1, and that PEG-CIFN monotherapy compares favorably

with dual therapy.

Host, virologic, and treatment factors such as viral

load, age, gender, race, state of fibrosis, BMI and HCV genotyping

have been reported to be associated with differences in response

rates to HCV treatment (22–24). In particular, the virologic response

to antiviral treatment in women has been reported to be higher with

standard-dose or high-dose peginterferon compared with low-dose

peginterferon α-2a (22,23). However, in the current study, no

significant effect of these factors on virological response was

found.

In conclusion, the rates of favorable virologic

response were similar, while the adverse event profile,

particularly the decreased degree of thrombocytopenia, was better

in patients who received PEG-CIFN compared with pegylated IFNα-2a.

This locally produced PEG-CIFN may make the treatment available to

many more patients. Limitations of this study include a small

sample size and a short observation period. Larger studies

particularly comparing PEG-CIFN in dual and triple therapy regimens

may be helpful in determining the role of PEG-CIFN in future

treatment of HCV infections.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Medjaden Bioscience Ltd. (Hong

Kong, China) for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

This clinical trial was supported by National S&T Surface

Project of China (grant.oo. 81172726), Chongqing Fujin Biomedical

Co., Ltd., China and Beijing Kain Technology Co., Ltd.

References

|

1

|

Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, Berg

T, Weltman M, Abate ML, Bassendine M, Spengler U, Dore GJ, Powell

E, et al: IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C

interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet. 41:1100–1104.

2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, Kurosaki

M, Matsuura K, Sakamoto N, Nakagawa M, Korenaga M, Hino K, Hige S,

et al: Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated

interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat

Genet. 41:1105–1109. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhang H, Jiang YF, He SM, Sun J, Gu Q,

Feng XW, Du B, Wang W, Shi XD, Wang CY, et al: Etiology and

prevalence of abnormal serum alanine aminotransferase levels in a

general population in Northeast China. Chin Med J (Engl).

124:2661–2668. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hinrichsen H, Benhamou Y, Wedemeyer H,

Reiser M, Sentjens RE, Calleja JL, Forns X, Erhardt A, Crönlein J,

Chaves RL, et al: Short-term antiviral efficacy of BILN 2061, a

hepatitis C virus serine protease inhibitor, in hepatitis C

genotype 1 patients. Gastroenterology. 127:1347–1355. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pawlotsky JM, Chevaliez S and McHutchison

JG: The hepatitis C virus life cycle as a target for new antiviral

therapies. Gastroenterology. 132:1979–1998. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G,

Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, Marcellin P, Muir AJ, Ferenci

P, Flisiak R, et al: Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic

hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 364:2405–2416. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Liu CH, Liu CJ, Lin CL, Liang CC, Hsu SJ,

Yang SS, Hsu CS, Tseng TC, Wang CC, Lai MY, et al: Pegylated

interferon-alpha-2a plus ribavirin for treatment-naive Asian

patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: A

multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis.

47:1260–1269. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

de Segadas-Soares JA, Villela-Nogueira CA,

Perez RM, Nabuco LC, Brandão-Mello CE and Coelho HS: Is the rapid

virologic response a positive predictive factor of sustained

virologic response in all pretreatment status genotype 1 hepatitis

C patients treated with peginterferon-alpha2b and ribavirin? J Clin

Gastroenterol. 43:362–366. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, Qi Y, Ge D,

O'Huigin C, Kidd J, Kidd K, Khakoo SI, Alexander G, et al: Genetic

variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus.

Nature. 461:798–801. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ahlenstiel G, Booth DR and George J: IL28B

in hepatitis C virus infection: Translating pharmacogenomics into

clinical practice. J Gastroenterol. 45:903–910. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, Ge D,

Fellay J, Shianna KV, Urban T, Afdhal NH, Jacobson IM, Esteban R,

et al: Interleukin-28B polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is

the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic

response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology.

139:120–129, e18. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Clark PJ, Thompson AJ and McHutchison JG:

IL28B genomic-based treatment paradigms for patients with chronic

hepatitis C infection: The future of personalized HCV therapies. Am

J Gastroenterol. 106:38–45. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Melian EB and Plosker GL: Interferon

alfacon-1: A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy in

the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Drugs. 61:1661–1691. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Moore CM, George M and Van Thiel DH:

Consensus interferon used to treat prior partial-responders to

pegylated interferon plus ribavirin. Dig Dis Sci. 56:3032–3037.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Cai Y, Zhang Z, Fan K, Zhang J, Shen W, Li

M, Si D, Luo H, Zeng Y, Fu P and Liu C: Pharmacokinetics, tissue

distribution, excretion, and antiviral activity of pegylated

recombinant human consensus interferon-α variant in monkeys, rats

and guinea pigs. Regul Pept. 173:74–81. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cheng J: New progress in therapy of

patients with chronic hepatitis C. Zhonghua Lin Chuang Gan Ran Bing

Za Zhi. 4:1–5. 2010.(In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Bajaire BJ, Paipilla DF, Arrieta CE and

Oudovitchenko E: Mixed vascular occlusion in a patient with

interferon-associated retinopathy. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2:23–29.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

McHutchison JG, Lawitz EJ, Shiffman ML,

Muir AJ, Galler GW, McCone J, Nyberg LM, Lee WM, Ghalib RH, Schiff

ER, et al: Peginterferon alfa-2b or alfa-2a with ribavirin for

treatment of hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 361:580–593.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Dienstag JL and McHutchison JG: American

Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the

management of hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 130:225–230. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H Jr, Morgan TR,

Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, Ramadori G, Bodenheimer H Jr,

Bernstein D, Rizzetto M, et al: Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin

combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: A randomized study of

treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 140:346–355.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Jacobson IM, Gordon SC, Kowdley KV,

Yoshida EM, Rodriguez-Torres M, Sulkowski MS, Shiffman ML, Lawitz

E, Everson G, Bennett M, et al: Sofosbuvir for hepatitis C genotype

2 or 3 in patients without treatment options. N Engl J Med.

368:1867–1877. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Rodriguez-Torres M, Jeffers LJ, Sheikh MY,

Rossaro L, Ankoma-Sey V, Hamzeh FM and Martin P: Latino Study

Group: Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in Latino and non-Latino

whites with hepatitis C. N Engl J Med. 360:257–267. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Shiffman ML, Salvatore J, Hubbard S, Price

A, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Luketic VA and Sanyal AJ: Treatment of

chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 with peginterferon, ribavirin,

and epoetin alpha. Hepatology. 46:371–379. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Daw MA, Elasifer HA, Dau AA and Agnan M:

The role of hepatitis C virus genotyping in evaluating the efficacy

of INF-based therapy used in treating hepatitis C infected patients

in Libya. Virol Discov. 1:32013. View Article : Google Scholar

|