Introduction

The fruit of the plum tree Prunus mume

Siebold & Zucc. (PM) is used across East Asia, particularly in

Korea and Japan (1), as a

traditional herbal medicine for the relief of digestive problems,

fatigue and fever. PM contains a number of phenolic compounds,

including phenolic acids and flavonoids (1,2), which

have antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities in

vivo (3–6). Furthermore, PM extracts exhibit many

pharmacological activities, including antimicrobial (7–10),

immune enhancing (11), anti-cancer

(1,12,13), and

anti-fatigue (14) effects, and have

been demonstrated to enhance osteoclast differentiation (15) and improve blood flow (16). Additionally, previous studies have

reported that using PM extracts with probiotics inhibits the

development of atopic dermatitis (17) and enhances immunity (18).

Interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs) are the

pacemakers of the gastro-intestinal tract and generate rhythmic

responses in cell membrane electrical potentials (19,20),

thus serving important roles in the regulation of GI motility

(21). Additionally, endogenous

agents are able to regulate GI motility function via ICCs (22–25).

Furthermore, transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) 7

(26) or Cl− channels,

such as anoctamin1 (ANO1) (27–29), are

associated with pacemaker potentials in the GI tract. Therefore,

TRPM7 and ANO1 may be therapeutic targets for the treatment of GI

motility disorders.

It has been reported previously that PM is able to

enhance the propulsive motion and motility of the small intestine

(7) and promote the frequency of

defecation and colon contraction in rats, which supports the

potential role of PM as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of

constipation (30). However, little

is known about the effect of PM on ICC clusters in the GI tract.

The aims of the present study were to evaluate the effects of the

methanoic extract of PM (m-PM) on the electrical pacemaker

potentials of cultured ICCs and characterize m-PM-mediated

signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Preparation of m-PM

PM fruits were harvested in the Wondong area,

(Yangsan, Geongnam, Korea) in June 2012 and were authenticated by

Professor Hyungwoo Kim (School of Korean Medicine, Pusan National

University, Yangsan, Korea). A standard extraction process was

performed to obtain m-PM, as previously described (24). Briefly, 50 g PM fruit was immersed in

0.5 l methanol, sonicated for 15 min and allowed to stand for 24 h.

The extract obtained was filtered through No. 20 Whatman filter

paper and lyophilized using a freeze dryer (Labconco Corp., Kansas

City, MO, USA). A total of 2.42 g of lyophilized powder (m-PM) was

subsequently obtained (yield, 4.84%). A 12.1 g sample of m-PM was

deposited at the School of Korean Medicine, Pusan National

University (voucher no. MH2012-008).

Ethics

Animal care and experiments were conducted in

accordance with the guidelines issued by the ethics committee of

Pusan National University (Busan, Korea; Approval no.

PNU-2014-0725) and the National Institutes of Health Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (31).

Preparation of cells and cell

cultures

A total of 78 BALB/c mice (male:female, 41:37; age,

4–7 days; weight, 2.0–2.2 g; Samtako Bio Korea Co., Ltd., Osan,

Korea) were anesthetized with 0.1% ether (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) and sacrificed using cervical

dislocation. Mice were maintained under controlled conditions

(temperature, 20±2°C; humidity, 50±5%; 12 h light/dark cycles) and

were allowed free access to food and water. Small intestines were

removed and opened along the mesenteric border, and luminal

contents were removed via washing with Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate

solution. Sharp dissection was performed to remove small intestine

mucosae and small strips of intestine muscle were subsequently

equilibrated in Ca2+-free physiological salt solution

(in mmol/l: 125 NaCl, 5.36 KCl, 0.34 NaOH, 0.44

Na2HCO3, 10 glucose, 2.9 sucrose, and 11

HEPES buffer) for 20 min and dispersed using an enzyme solution

containing 1.5 mg/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical Corp.,

Lakewood, NJ, USA), 2.5 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck Millipore), 2.5 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

Millipore) and 0.5 mg/ml adenosine triphosphate (ATP)

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore). Cells were plated on glass

coverslips coated with 0.01% poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma-Aldrich;

Merck Millipore) and cultured in an atmosphere containing 95%

O2 and 5% CO2 in smooth muscle basal medium

(Clonetics Corp.; Lonza, Walkersville, MA, USA) supplemented with

stem cell factor (5 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck Millipore) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA) at 37°C.

Whole cell patch-clamp

experiments

The Na+-Tyrode solution used in bath

solution contained 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, 2 mM

CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer,

adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. A pipette solution was also used,

which contained 140 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2.7 mM

K2ATP, 0.1 mM Na guanosine triphosphate (GTP), 2.5 mM

creatine phosphate disodium, 5 mM HEPES buffer and 0.1 mM ethylene

glycol bis (2-aminoethyl ether)-N,

N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), adjusted to

pH 7.2 with KOH. The whole-cell patch-clamp technique was performed

to record the membrane electrical potentials in cultured ICCs and

membrane potentials were amplified using an Axopatch 1-D (Molecular

Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Command pulses were applied

using a Samsung-compatible personal computer and pClamp software

(ver. 9.0; Molecular Devices). Data were filtered at 1 kHz and

displayed on a computer monitor. pClamp and Origin software (ver.

8.0; MicroCal, Northampton, MA, USA) were used for statistical

analysis. All experiments were performed at 30°C.

TRPM7 overexpression

Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells (American

Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) were transfected with

Flag-murine LTRPC7/pCDNA4-TO construct and subsequently cultured in

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with 5 µg/ml blasticidin, 0.4 mg/ml zeocin and 10%

fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Adding 1 µg/ml

tetracycline to the medium for 24 h induced TRPM7 overexpression.

HEK293 cells overexpressing TRPM7 were bathed in a solution

containing 145 mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM

glucose, 1.2 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM HEPES buffer, adjusted

to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The pipette solution contained 145 mM

Cs-glutamate, 8 mM NaCl, 10 mM Cs-2-bis

(2-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic

acid, and 10 mM HEPES-CsOH, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH.

Ca2+ activated

Cl− channel overexpression

HEK-293 cells were transfected with the

pEGFP-N1-mANO1 construct for 24 h and these cells were cultured on

glass coverslips in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle medium, which was

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The bath solution

contained 146 mM HCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM

MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2 and 150 mM

N-methyl-D-glucamine (NMDG), adjusted to pH 7.4. The pipette

solution contained 150 mM NMDG-Cl, 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM

MgATP, 10 mM EGTA, 5 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM HEPES buffer at

pH 7.2 (titrated with NMDG). WEBMAX-C STANDARD software (C. Patton,

Stanford University, www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/maxc.html) was used to fix

the free calcium concentration at 200 nM.

Pharmacological agents

Pharmacological agents, including methoctramine,

4-diphenylacetoxy-N-methyl-piperidine methiodide (4-DAMP),

guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiodiphosphate) (GDP-β-S), thapsigargin,

PD98059, SB203580 and SP600125, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich

(Merck Millipore). They were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)

or distilled water and stored at −20°C. The final concentration of

DMSO in the bath solution was maintained at <0.1%.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of

the means. Student's t-test for unpaired data was performed

to compare control and experimental groups. Origin software

(version 8.0; OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) was used to perform

statistical analysis. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Effect of m-PM on pacemaker electrical

potentials in cultured ICCs

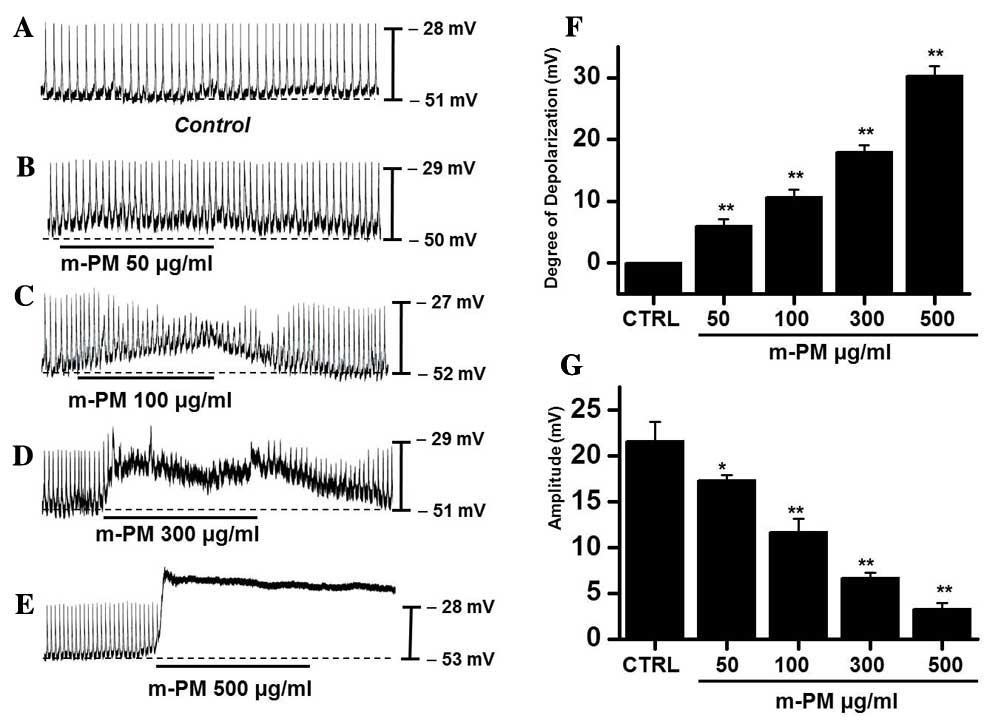

The effect of m-PM on pacemaker electrical

potentials in cultured ICCs was investigated. Mean resting

electrical potential of membranes was −51.7±2.4 mV and the

electrical amplitude was 21.6±2.3 mV. Following m-PM administration

(50–500 µg/ml), mean membrane electrical potentials were

depolarized to 6.2±1.3 (50 µg/ml), 10.6±1.2 (100 µg/ml), 18.5±1.5

(300 µg/ml) and 30.3±1.6 mV (500 µg/ml; Fig. 1A-E), and corresponding amplitudes

decreased to 17.3±0.6, 11.4±1.5, 6.7±0.8, and 3.3±0.5 mV,

respectively (Fig. 1B-E). The

effects of m-PM on pacemaker electrical potentials are presented in

Fig. 1F and G (n=7). These results

suggest that m-PM modulates the pacemaker potentials of ICCs.

m-PM receptors in cultured ICCs

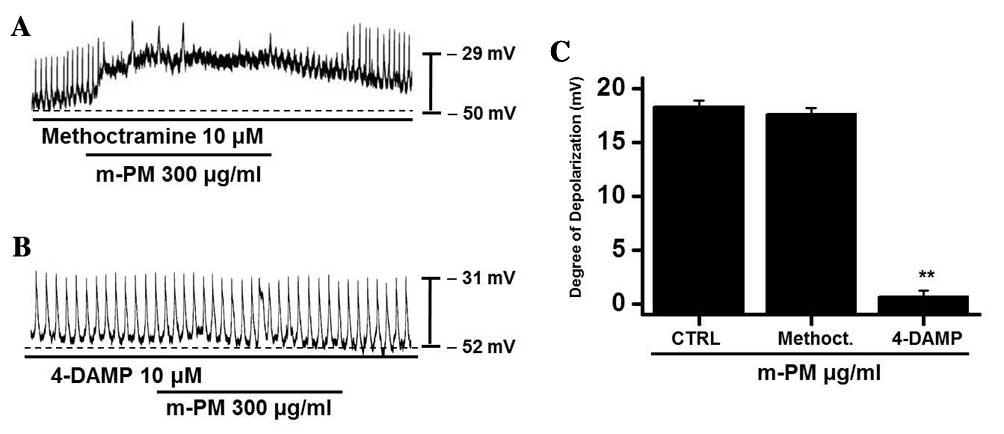

To study the m-PM receptors on ICCs, muscarinic

receptors were investigated as they mediate membrane electrical

depolarization in the GI tract (32,33).

Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that ICCs express

M2 and M3 muscarinic receptors in the GI

tract (34). Pretreatment with

muscarinic receptor antagonists was performed to identify which

muscarinic receptor was associated with the response. Membranes

were pretreated with 10 µm methoctramine, which is a muscarinic

M2 receptor antagonist, or 4-DAMP, which is a muscarinic

M3 receptor antagonist, for 5 min prior to m-PM (300

µg/ml) administration. Neither antagonist had any effect on

pacemaker potentials. Methoctramine did not inhibit the effect of

m-PM (Fig. 2A), whereas 4-DAMP was

able to inhibit m-PM-induced membrane depolarization (Fig. 2B). The mean membrane electrical

depolarization by m-PM following pretreatment with methoctramine or

4-DAMP was 17.5±0.7 and 0.9±0.4 mV, respectively (n=5 in each;

Fig. 2C). These results indicate

that m-PM affects ICCs through M3 receptors, not

M2 receptors.

Association between G proteins and

m-PM-induced pacemaker electrical potentials in cultured ICCs

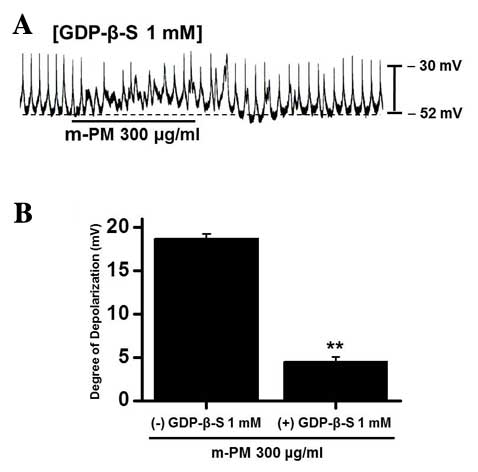

GDP-β-S, which permanently inactivates G-protein

binding proteins (35,36), was administered to determine whether

G-proteins are associated with the effects of m-PM on cultured

ICCs. m-PM (300 µg/ml) induced ICC membrane depolarization

(Fig. 1D); however, when GDP-β-S (1

mM) was present in the pipette solution, m-PM-induced

depolarization was markedly reduced (n=5; Fig. 3). These results suggest that

G-proteins have a role in the m-PM-induced pacemaker depolarization

of ICCs.

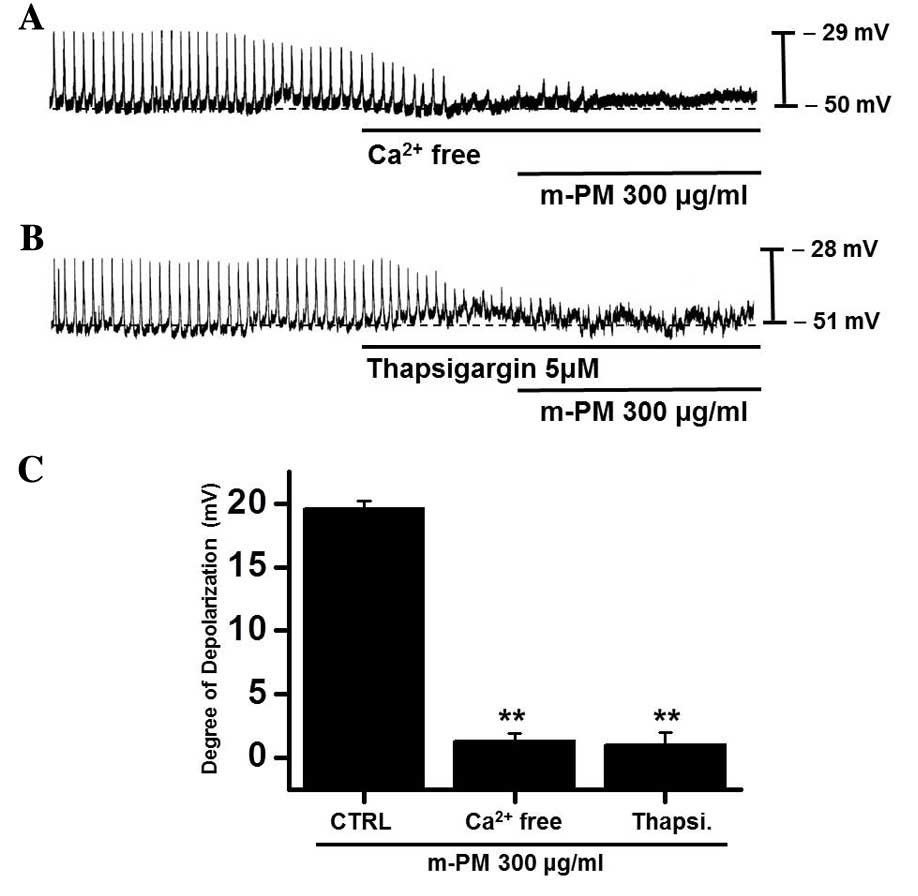

Effects of external

Ca2+-free solution and Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor

of endoplasmic reticulum on m-PM-induced pacemaker electrical

potentials of cultured ICC

An influx of external Ca2+ is required

for GI contractions and pacemaker electrical depolarizations in

ICCs (37). Furthermore, pacemaker

electrical depolarizations are regulated by intracellular

Ca2+ modulations (37).

To investigate the roles of external and internal Ca2+

on m-PM-induced pacemaker depolarizations, m-PM was applied in the

absence of external Ca2+ and in the presence of

thapsigargin (a Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor in endoplasmic

reticulum). When exposed to the external Ca2+-free

condition, pacemaker potentials were abolished and were unaffected

by the administration of m-PM (Fig.

4A). Pretreatment with thapsigargin (5 µM) also suppressed

pacemaker electrical potentials and in these conditions, m-PM had

no effect on pacemaker electrical potentials (Fig. 4B). The effects of m-PM on pacemaker

electrical potentials are presented in Fig. 4C (n=6). These results suggest

external Ca2+ or internal Ca2+ regulations

modulate m-PM-induced pacemaker electrical potentials in cultured

ICCs.

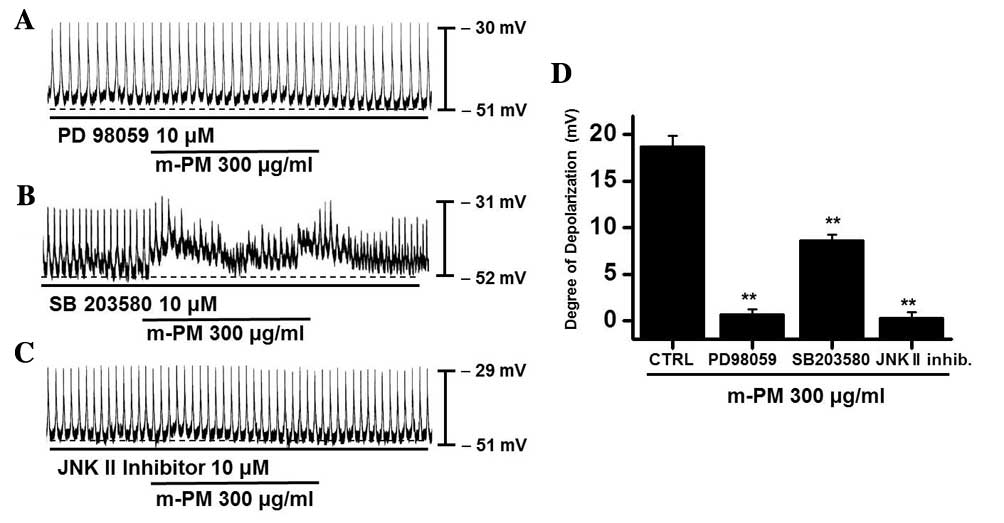

Association of mitogen-activated

protein kinase (MAPKs) with m-PM-induced pacemaker potentials of

cultured ICCs

To evaluate the mechanisms involved in the

interaction between m-PM and M3 receptors, the role of

mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) was investigated. It has

been demonstrated that muscarinic receptors are able to activate

MAPKs in various cell types (38,39);

therefore, the potential role of MAPKs in regulating the effects of

m-PM was determined by administrating a p42/44 MAPK inhibitor

(PD98059), a p38 MAPK inhibitor (SB203580) or a c-jun NH2-terminal

kinase (JNK) II inhibitor (SP600125). PD98059 (10 µM), m-PM did not

induce membrane electrical depolarization (Fig. 5A). m-PM-induced membrane electrical

depolarization was partially blocked by the administration of

SB203580 (Fig. 5B) and completely

blocked by the administration of SP600125 (Fig. 5C). The effects of m-PM on pacemaker

electrical potentials are presented in Fig. 5D (n=5). These results suggest that

MAPKs modulate m-PM-induced pacemaker electrical potentials in

cultured ICCs.

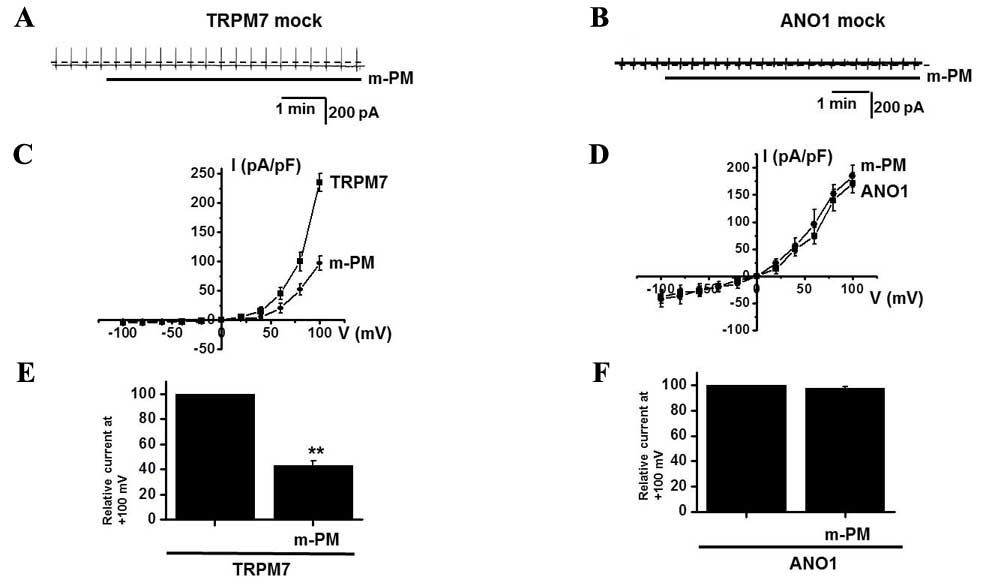

Association of TRPM7 and

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels with m-PM-induced

pacemaker potentials in cultured ICCs

In the murine small intestine, pacemaker potentials

are predominantly induced by the activation of non-selective cation

channels (25,26) or Cl−channels (27–29). To

determine which channel is associated with the m-PM-induced

depolarization of pacemaker potentials, the effects of m-PM on

TRPM7 and Ca2+-activated Cl− channels were

examined. Membranes were transfected with the FLAG-murine

TRPM7/pCDNA4/TO construct using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and ~90% of cells were transfected. In a previous

study, TRPM7-transfected HEK293 cells induced by tetracycline

produced a flag-reactive band with a relative molecular mass of 220

kilodaltons (21). Another study

revealed that ANO1 channels were overexpressed in HEK293 cells

transfected with an ANO1 construct (40) and whole cell currents were recorded

using patch-clamp techniques. In the present study, TRPM7 and ANO1

currents were activated in mock transfected cells (Fig. 6A and B) and it was demonstrated that

m-PM inhibited the activities of TRPM7 channels, but did not affect

the Ca2+-activated Cl− ANO1 channels (n=4;

Fig. 6C-F), thus indicating that the

effects of m-PM are attributable to TRPM7 channels.

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that

administration of m-PM induced depolarization of ICC pacemaker

potentials through muscarinic M3 receptor signaling

pathways in a G protein-MAPK dependent manner. Furthermore, m-PM

was able to inhibit TRPM7 currents, indicating that TRPM7 is

associated with the m-PM-induced membrane depolarization of

ICCs.

In intestinal motility, PM has been reported to

enhance propulsive motion and small intestine motility, as

determined by the coated charcoal method (7). Additionally, it has been demonstrated

that PM has laxative effects in constipation rat models, as it

accelerated the spontaneous contraction of isolated colon (30). Furthermore, citric and malic acid,

the major organic acids in plums, stimulate spontaneous

contractions in the colon (30).

These findings support the commonly held belief that plums help to

prevent constipation and that ICCs function as pacemakers in the

small intestine thus modulating GI motility. In the present study,

it was identified that m-PM depolarizes ICC pacemaker activity.

The authors of the present study have previously

investigated the effects of traditional medicines on pacemaker

electrical potentials in ICCs. It has been determined that

Poncirus fructus (PF) is able to modulate pacemaker

electrical potentials via the 5-hydroxytryptamine

(5-HT)3 and 5-HT4 receptor pathways in a

MAPK-dependent manner (24) and

gintonin-mediated membrane depolarization and

Ca2+-activated Cl− channel activation have

been observed in cultured murine ICCs via a lysophosphatidic acid

1/3 receptor signaling pathway (41). Additionally, it was determined that

San-Huang-Xie-Xin-tang (SHXXT) is able to modulate pacemaker

electrical potentials (42). The

results of in vivo experiments suggested that

SHXXT-regulated GI motility was due to the activities of

Coptidis rhizome and Rhei rhizome (42). Furthermore, Schisandra

chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. extract (SC extract) was determined

to modulate ICC pacemaker potentials via external and internal

Ca2+ regulation, and via G protein and the phospholipase

C (PLC) pathway, in a dose-dependent manner, and increased

intestinal transit rates in mouse models of normal and abnormal GI

motility (43). These studies

indicate that traditional medicines, such as PF, ginseng, SHXXT and

SC may potentially be used as gastroprokinetic agents. The results

of the present study demonstrated that m-PM exhibited the potential

of a prokinetic agent for GI motility dysfunctions.

The MAPK family of protein kinases serve critical

roles in signal transduction (44,45) and

the regulation of various cellular responses, including cell cycle

progression, differentiation, inflammation, protein synthesis and

proliferation (46). There are five

subtypes of acetylcholine muscarinic receptors

(M1-M5), of which three (M1,

M3, and M5) are coupled with PLC through a

Gq protein, whereas the other subtypes (M2

and M4) are able to inhibit adenylate cyclase via

Go or Gi proteins (47). In various cellular systems,

muscarinic receptor stimulation has been reported to activate MAPK

(48,49). In the present study, the effects of

m-PM on ICCs in the murine small intestine were investigated. m-PM

modulated pacemaker activities in ICCs through muscarinic

M3 receptor activation via G protein, PLC and

MAPK-dependent mechanisms. Therefore, ICCs are targets for m-PM and

this interaction may improve intestinal motility.

In conclusion, Prunus mume Siebold &

Zucc. was able to depolarize ICC pacemaker potentials in a G

protein and MAPK-dependent manner by stimulating M3

receptors. These findings suggest that Prunus mume Siebold

& Zucc. may be developed as a potential gastroprokinetic agent

for the treatment of GI motility disorders.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Research

Institute for Convergence of Biomedical Science and Technology

(grant no. 30-2014-011), Pusan National University Yangsan

Hospital.

References

|

1

|

Jeong JT, Moon JH, Park KH and Shin CS:

Isolation and characterization of a new compound from Prunus mume

fruit that inhibits cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 54:2123–2128.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kita M, Kato M, Ban Y, Honda C, Yaegaki H,

Ikoma Y and Moriguchi T: Carotenoid accumulation in Japanese

apricot (Prunus mume Siebold & Zucc.): Molecular analysis of

carotenogenic gene expression and ethylene regulation. J Agric Food

Chem. 55:3414–3420. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim BJ, Kim JH, Kim HP and Heo MY:

Biological screening of 100 plant extracts for cosmetic use (II):

Anti-oxidative activity and free radical scavenging activity. Int J

Cosmet Sci. 19:299–307. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tsai CH, Chang RC, Chiou JF and Liu TZ:

Improved superoxide-generating system suitable for the assessment

of the superoxide-scavenging ability of aqueous extracts of food

constituents using ultraweak chemiluminescence. J Agric Food Chem.

51:58–62. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Matsuda H, Morikawa T, Ishiwada T, Managi

H, Kagawa M, Higashi Y and Yoshikawa M: Medicinal flowers. VIII.

Radical scavenging constituents from the flowers of Prunus mume:

Structure of prunose III. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 51:440–443.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kim TK, Cha MR, Kim SJ, Kim SY, Jeon KI,

Park HR, Park EJ and Lee SC: Antioxidative activity of methanol

extract from Prunus mume byproduct. Cancer Prev Res. 10:251–256.

2005.

|

|

7

|

Wang L, Zhang HY and Wang L: Comparison of

pharmacological effects of Fructus Mume and its processed products.

Zhong Yao Cai. 33:353–356. 2010.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Chen Y, Wong RW, Seneviratne CJ, Hägg U,

McGrath C, Samaranayake LP and Kao R: The antimicrobial efficacy of

Fructus mume extract on orthodontic bracket: A monospecies-biofilm

model study in vitro. Arch Oral Biol. 56:16–21. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Seneviratne CJ, Wong RW, Hägg U, Chen Y,

Herath TD, Samaranayake PL and Kao R: Prunus mume extract exhibits

antimicrobial activity against pathogenic oral bacteria. Int J

Paediatr Dent. 21:299–305. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Enomoto S, Yanaoka K, Utsunomiya H, Niwa

T, Inada K, Deguchi H, Ueda K, Mukoubayashi C, Inoue I, Maekita T,

et al: Inhibitory effects of Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Siebold

et Zucc.; Ume) on Helicobacter pylori-related chronic gastritis.

Eur J Clin Nutr. 64:714–719. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kawahara K, Hashiguchi T, Masuda K,

Saniabadi AR, Kikuchi K, Tancharoen S, Ito T, Miura N, Morimoto Y,

Biswas KK, et al: Mechanism of HMGB1 release inhibition from

RAW264.7 cells by oleanolic acid in Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc. Int

J Mol Med. 23:615–620. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mori S, Sawada T, Okada T, Ohsawa T,

Adachi M and Keiichi K: New anti-proliferative agent, MK615, from

Japanese apricot ‘Prunus mume’ induces striking autophagy in colon

cancer cells in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 13:6512–6517. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kai H, Akamatsu E, Torii E, Kodama H,

Yukizaki C, Sakakibara Y, Suiko M, Morishita K, Kataoka H and

Matsuno K: Inhibition of proliferation by agricultural plant

extracts in seven human adult T-cell leukaemia (ATL)-related cell

lines. J Nat Med. 65:651–655. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kim S, Park SH, Lee HN and Park T: Prunus

mume extract ameliorates exercise-induced fatigue in trained rats.

J Med Food. 11:460–468. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Youn YN, Lim E, Lee N, Kim YS, Koo MS and

Choi SY: Screening of Korean medicinal plants for possible

osteoclastogenesis effects in vitro. Genes Nutr. 2:375–380. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chuda Y, Ono H, Ohnishi-Kameyama M,

Matsumoto K, Nagata T and Kikuchi Y: Mumefural, citric acid

derivative improving blood fluidity from fruit-juice concentrate of

Japanese apricot (Prunus mume Sieb. et Zucc). J Agric Food Chem.

47:828–831. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jung BG, Cho SJ, Koh HB, Han DU and Lee

BJ: Fermented Maesil (Prunus mume) with probiotics inhibits

development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice.

Vet Dermatol. 21:184–191. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jung BG, Ko JH, Cho SJ, Koh HB, Yoon SR,

Han DU and Lee BJ: Immune-enhancing effect of fermented Maesil

(Prunus mume Siebold & Zucc.) with probiotics against

Bordetella bronchi septica in mice. J Vet Med Sci. 72:1195–1202.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Huizinga JD, Thuneberg L, Kluppel M,

Malysz J, Mikkelsen HB and Bernstein A: W/kit gene required for

interstitial cells of Cajal and for intestinal pacemaker activity.

Nature. 373:347–349. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Sanders KM: A case for interstitial cells

of Cajal as pacemakers and mediators of neurotransmission in the

gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 111:492–515. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Kim BJ, Lim HH, Yang DK, Jun JY, Chang IY,

Park CS, So I, Stanfield PR and Kim KW: Melastatin-type transient

receptor potential channel 7 is required for intestinal pacemaking

activity. Gastroenterology. 129:1504–1517. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee JH, Kim SY, Kwon YK, Kim BJ and So I:

Characteristics of the cholecystokinin-induced depolarization of

pacemaking activity in cultured interstitial cells of Cajal from

murine small intestine. Cell Physiol Biochem. 31:542–554. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kim BJ, Kim SY, Lee S, Jeon JH, Matsui H,

Kwon YK, Kim SJ and So I: The role of transient receptor potential

channel blockers in human gastric cancer cell viability. Can J

Physiol Pharmacol. 90:175–186. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kim BJ, Kim HW, Lee GS, Choi S, Jun JY, So

I and Kim SJ: Poncirus trifoliate fruit modulates pacemaker

activity in interstitial cells of Cajal from the murine small

intestine. J Ethnopharmacol. 149:668–675. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Koh SD, Jun JY, Kim TW and Sanders KM: A

Ca2+-inhibited non-selective cation conductance

contributes to pacemaker currents in mouse interstitial cell of

Cajal. J Physiol. 540:803–814. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim BJ, So I and Kim KW: The relationship

of TRP channels to the pacemaker activity of interstitial cells of

Cajal in the gastrointestinal tract. J Smooth Muscle Res. 42:1–7.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Huizinga JD, Zhu Y, Ye J and Molleman A:

High-conductance chloride channels generate pacemaker currents in

interstitial cells of Cajal. Gastroenterology. 123:1627–1636. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Britton FC, O'Driscoll

KE, Hennig G, Bayguinov YR, Rock JR, Harfe BD, Sanders KM and Ward

SM: Expression of anoctamin 1/TMEM16A by interstitial cells of

Cajal is fundamental for slow wave activity in gastrointestinal

muscles. J Physiol. 587:4887–4904. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Zhu MH, Kim TW, Ro S, Yan W, Ward SM, Koh

SD and Sanders KM: A Ca2+-activated Cl(−) conductance in

interstitial cells of Cajal linked to slow wave currents and

pacemaker activity. J Physiol. 587:4905–4918. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Na JR, Oh KN, Park SU, Bae D, Choi EJ,

Jung MA, Choi CY, Lee DW, Jun W, Lee KY, et al: The laxative

effects of Maesil (Prunus mume Siebold & Zucc.) on constipation

induced by a low-fibre diet in a rat model. Int J Food Sci Nutr.

64:333–345. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

National Research Council, . Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academies Press (US);

Washington (DC): 2011, PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Huizinga JD, Chang G, Diamant NE and

El-Sharkawy TY: Electrophysiological basis of excitation of canine

colonic circular muscle by cholinergic agents and substance P. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 231:692–699. 1984.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Inoue R and Chen S: Physiology of

muscarinic receptor operated nonselective cation channels in

guinea-pig ilieal smooth muscle. EXS. 66:261–268. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Epperson A, Hatton WJ, Callaghan B,

Doherty P, Walker RL, Sanders KM, Ward SM and Horowitz B: Molecular

markers expressed in cultured and freshly isolated interstitial

cells of Cajal. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 279:C529–C539.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Komori S, Kawai M, Takewaki T and Ohashi

H: GTP-binding protein involvement in membrane currents evoked by

carbachol and histamine in guinea-pig ileal muscle. J Physiol.

450:105–126. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Ogata R, Inoue Y, Nakano H, Ito Y and

Kitamura K: Oestradiol-induced relaxation of rabbit basilar artery

by inhibition of voltage-dependent Ca channels through GTP-binding

protein. Br J Pharmacol. 117:351–359. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ward SM, Ordog T, Koh SD, Baker SA, Jun

JY, Amberg G, Monaghan K and Sanders KM: Pacemaking in interstitial

cells of Cajal depends upon calcium handling by endoplasmic

reticulum and mitochondria. J Physiol. 525:2355–361. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Yagle K, Lu H, Guizzetti M, Möller T and

Costa LG: Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by

muscarinic receptors in astroglial cells: Role in DNA synthesis and

effect of ethanol. Glia. 35:111–120. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sakai H, Otogoto S, Chiba Y, Abe K and

Misawa M: Involvement of p42/44 MAPK and RhoA protein in

augmentation of ACh-induced bronchial smooth muscle contraction by

TNF-alpha in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 97:2154–2159. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Nam JH, Kim WK and Kim BJ: Sphingosine and

FTY720 modulate pacemaking activity in interstitial cells of Cajal

from mouse small intestine. Mol Cells. 36:235–244. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kim BJ, Nam JH, Kim KH, Joo M, Ha TS, Weon

KY, Choi S, Jun JY, Park EJ and Wie J: Characteristics of

gintonin-mediated membrane depolarization of pacemaker activity in

cultured interstitial cells of Cajal. Cell Physiol Biochem.

34:873–890. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kim BJ, Kim H, Lee GS, So I and Kim SJ:

Effects of San-Huang-Xie-Xin-tang, a traditional Chinese

prescription for clearing away heat and toxin, on the pacemaker

activities of interstitial cells of Cajal from the murine small

intestine. J Ethnopharmacol. 155:744–752. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ahn TS, Kim DG, Hong NR, Park HS, Kim H,

Ha KT, Jeon JH, So I and Kim BJ: Effects of Schisandra chinensis

extract on gastrointestinal motility in mice. J Ethnopharmacol.

169:163–169. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Garrington TP and Johnson GL: Organization

and regulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling

pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 11:211–218. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Derkinderen P, Enslen H and Girault JA:

The ERK/MAP-kinases cascade in the nervous system. Neuroreport.

10:R24–R34. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Lukacs NW, Strieter RM, Chensue SW, Widmer

M and Kunkel SL: TNF-alpha mediates recruitment of neutrophils and

eosinophils during airway inflammation. J Immunol. 154:5411–5417.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Nathanson NM: A multiplicity of muscarinic

mechanisms: Enough signaling pathways to take your breath away.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:6245–6247. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Slack BE: The M3 muscarinic acetylcholine

receptor is coupled to mitogen-activated protein kinase via protein

kinase C and epidermal growth factor receptor kinase. Biochem J.

348:2381–387. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yagle K, Lu H, Guizzetti M, Möller T and

Costa LG: Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by

muscarinic receptors in astroglial cells: Role in DNA synthesis and

effect of ethanol. Glia. 35:111–120. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|