Introduction

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is a

minimally invasive technique used to restore nasal cavity

ventilation and sinus function (1).

Bleeding is an important challenge for clinicians to overcome in

FESS. Due to the enriched blood vessels in the nasal cavity and

hemostasis difficulty, bleeding not only hinders the surgical field

of FESS, but also prolongs the duration of surgery time and

increases the risk of complications (2).

Various methods are used to reduce bleeding during

FESS surgery, but controlled hypotension remains an important

factor (3). In the past, vasoactive

drugs were used for the control of blood pressure; however, these

agents are prone to causing hemodynamic instability and, in severe

cases, even organ ischemia leading to significant organ dysfunction

(4). Currently, anesthesia

techniques and drugs are more commonly used for controlling blood

pressure and heart rate (HR), in order to reduce FESS bleeding

(5). Previous studies have reported

that the use of propofol and remifentanil for total intravenous

anesthesia has a notable advantage in reducing bleeding compared

with inhalation anesthesia (6–8), which

has made propofol and remifentanil for total intravenous anesthesia

the preferred method for FESS surgery anesthesia. However, there

may still be room for improvement in reducing intraoperative

bleeding and improving the surgical field. At present, there is

little research in this area.

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2

adrenoceptor agonist which inhibits activity of the sympathetic

nervous system, reduces the release of catecholamines, lowers blood

pressure and slows the HR (9).

Previous studies have indicated that dexmedetomidine, like

remifentanil, is effective in controlling blood pressure and

maintaining hemodynamic stability, so as to achieve the same

surgical field as remifentanil (10,11).

However, it is not yet known what the effects would be if these two

drugs were used in combination.

The primary objective of this prospective,

randomized, controlled study was to evaluate the effect of

dexmedetomidine combined with target-controlled infusion (TCI) of

propofol and remifentanil on FESS bleeding and the surgical

field.

Materials and methods

Patients and characteristics

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shenzhen People's Hospital (Shenzhen, China). Written

informed consent was obtained from all participants. A total of 62

patients undergoing elective FESS surgery, American Society of

Anesthesiologists (ASA) class I–II, aged 19–53 years old,

participated in the present study between September 2013 and

January 2016. Exclusion criteria were as follows: body mass index

≥25, HR <50 times per min, heart block, hypertension, coronary

heart disease, diabetes, history of asthma, chronic obstructive

emphysema, treatments with antibiotics or anticoagulants,

coagulation abnormalities, failure of cooperation because of mental

disorders, and use of sedative and analgesic drugs within 48 h

before surgery. An anesthesiologist, who participated in the design

of the grouping but not in anesthesia and data collection, assigned

dexmedetomidine. A different anesthesiologist performed clinical

anesthesia and data collection. Surgeons and patients were blinded

to the groupings.

Patient grouping

Patients were randomly divided into an experimental

group and a control group with 31 cases in each group. In the

experimental group, the procedure was as following: Before the

induction of anesthesia, infusion of 0.5 µg kg−1

dexmedetomidine was performed within 15 min, followed by 0.5 µg

kg−1 h−1 dexmedetomidine via intravenous pump

continuous injection until the end of the surgery. The control

group were administered with an intravenous pump injection normal

saline equivalent to the volume of dexmedetomidine administered in

the experimental group. All patients entered the operating room

without pre-medication and having fasted for 8–12 h. An anesthesia

monitor was used (Compact Anesthesia Monitor; GE Healthcare,

Chicago, IL, USA) and routine electrocardiogram monitoring was

carried out. Saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) and

end tidal carbon dioxide (PetCO2) were monitored. Depth

of anesthesia was measured using a bispectral index (BIS) system

(BIS Vista Monitoring System, Aspect Medical Systems; Covidien,

Dublin, Ireland). All patients were subjected to tracheal

intubation and general anaesthesia with TCI of propofol and

remifentanil to maintain the effect-site concentration. Oxygen

ventilation of 5 l·min−1, was administered 5 min before

using commercial TCI system (Base Observational, Fresenius Kabi AG,

Bad Homburg, Germany). TCI consisted of 4 µg ml−1

propofol (Schnider model) and 3 ng ml−1 remifentanil

(Minto model) for anesthesia induction of (12). Tracheal intubation was performed 120

sec after administration of intravenous injection of 0.2 mg

kg−1 cisatracurium ammonium and mask-assisted

ventilation following TCI (endotracheal tube diameter, 7.0 mm for

females and 7.5 mm for males). Subsequently, endotracheal tube was

connected with the anesthesia machine (Primus; Draeger Medical Ag

& Co. KGaA, Luebeck, Germany) to control the breathing, and

respiratory parameters were adjusted to the following: Tidal

volume, 6–10 ml kg−1; respiratory rate, 12–16 times/min;

inspiration/expiration ratio, 1:2; PetCO2 maintained at

35–45 mmHg; and airway pressure maintained at 10–20

mmH2O. TCI of 2–8 µg ml−1 propofol and 2–6 ng

ml−1 remifentanil was applied to maintain anesthesia.

Through adjusting the dosage of the propofol and remifentanil, BIS

value was maintained at 45–55 and mean arterial pressure (MAP) was

maintained at 70–80 mmHg. Intravenous injection of 0.25 mg atropine

was administered if HR was <50 times/min, which was considered

as bradycardia.

Surgery

All patients were in the supine position for

surgery. Prior to the start of surgery, four pieces of tampon,

soaked in adrenaline and lidocaine mixture solution (0.1%

epinephrine: 2% lidocaine, 1:1) were used to shrink the blood

vessels in the nasal mucosa. All surgical procedures were performed

by the same surgeon using standard procedures.

At the end of surgery, propofol and remifentanil

were replaced with intravenous injection of 40 mg parecoxib sodium

for postoperative analgesia. Patients were moved into

Postanesthesia Care Unit (PACU), where another anesthesiologist,

responsible for recovery from anesthesia, finished extubation after

patients were awake. 1 µg kg−1 fentanyl was administered

if visual analog scale (VAS) score was >5 in the PACU.

Intra-operative variables and recovery

profiles for patients

In the operating room, MAP and HR were recorded at

baseline (T0), before anesthesia induction (T1), before tracheal

intubation (T2), at the moment of tracheal intubation (T3), before

the start of surgery (T4), 15 min after the start of surgery (T5),

at the end of surgery (T6) and at the moment of extubation

(T7).

The following parameters were recorded: Duration of

surgery, duration of anesthesia (from anesthesia induction to

anesthetic drug withdrawal), consumption of propofol and

remifentanil, incidence of bradycardia and blood loss. Following

completion of the surgery, surgeons evaluated the surgical field

using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), from 0 (worst) to 10 (best)

(10). Extubation time (from

anesthetic drug withdrawal to extubation and respiratory rate after

extubation were recorded. The Observer's Assessment of

Alertness/Sedation (OAA/S) scale (13) was used to assess sedation 5 min after

extubation and pain severity was recorded using VAS (11) before the patient left the recovery

room. The use of fentanyl was observed in recovery room. Hypoxemia

after extubation (SpO2 <90%) and postoperative nausea

and vomiting (PONV) were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed using

SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were presented as

the mean ± standard deviation and analyzed with a Student's t-test

while count data were presented as percentage (%) or median

(interquartile range) and analyzed using the χ2 test,

respectively. MAP and HR were analyzed using one-way analysis of

variance (ANAOVA) followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc test. Grade

data, including NRS, OAA/S and VAS, were analyzed using the Mann

Whitney-U test. P<0.05 was considered as the level of

significant difference.

Results

Demographic characteristics of

patients

A total of 64 patients participated in the present

study. Data from 62 patients were successfully collected and

analyzed. The patients' characteristics did not differ between the

two groups (Table I).

| Table I.Demographic characteristics of

patients. |

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of

patients.

| Characteristic | Experimental group

(n=31) | Control group

(n=31) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 35.7±8.4 | 36.2±9.9 | 0.44 |

| Sex,

male/female | 21/10 | 17/14 | 0.43 |

| ASA classification,

I/II | 26/5 | 28/3 | 0.71 |

| Height, cm | 169.5±7.9 | 166.9±8.7 | 0.33 |

| Weight, kg | 65.3±10.1 | 61.9±9.2 | 0.67 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | 22.6±1.8 | 22.1±1.4 | 0.10 |

MAP and HR measurement

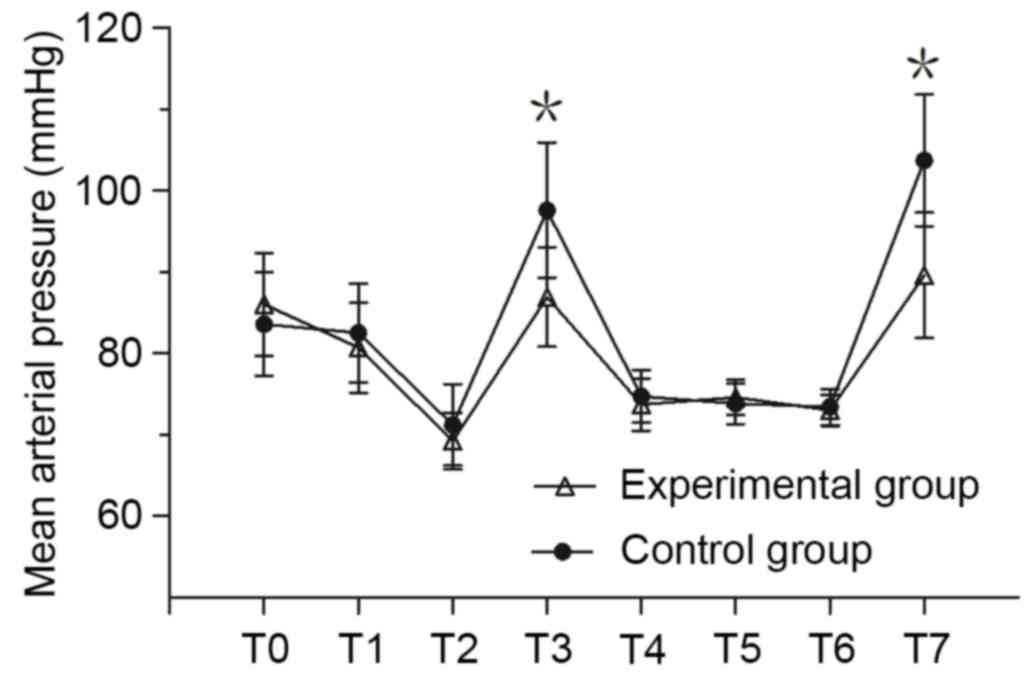

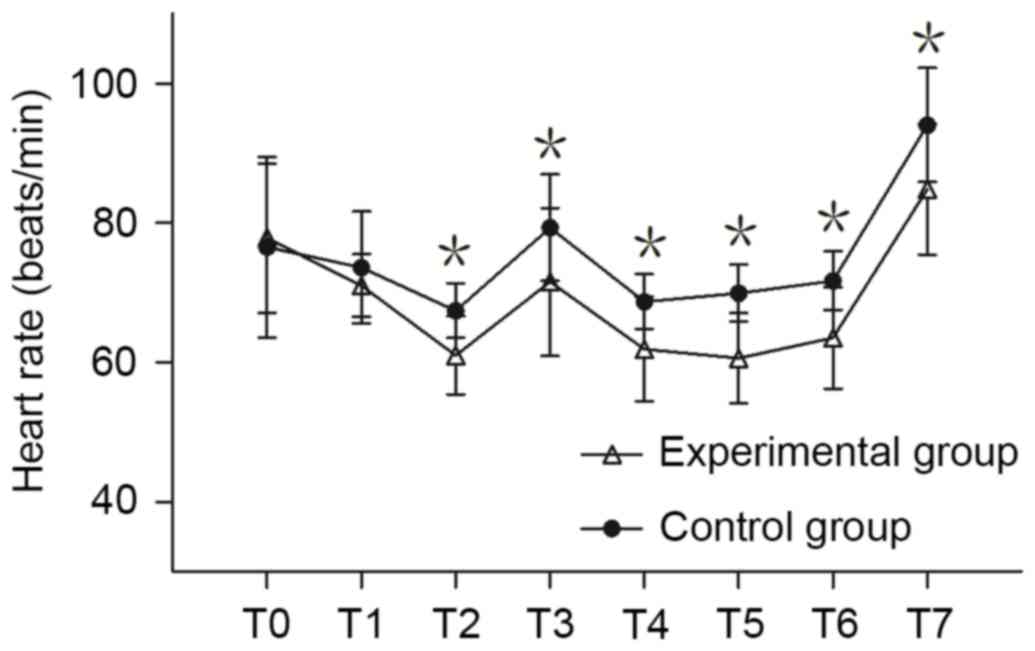

MAP and HR of the experimental group at T3 and T7

was significantly lower compared with the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 1). There was no significant

difference in MAP between the two groups at any other time point.

There was no significant difference in HR between the two groups at

T0 and T1; however, the HR of the experimental group was

significantly lower compared with the control group at T2-T7

(P<0.05; Fig. 2).

Intraoperative variables of

patients

Intraoperative observation results are shown in

Table II. There was no significant

difference between the two groups in terms of the surgical duration

or anesthesia duration. In the experimental group, the mean

infusion rates of propofol and remifentanil during surgery were

101.5±8.2 µg kg−1 min−1 and 6.1±0.2 µg

kg−1 h−1 respectively, which was

significantly lower than the control group, in which the infusion

rates were 117.9±4.3 µg kg−1 min−1 (P=0.001)

and 9.1±0.4 µg kg−1 h−1 (P=0.045),

respectively. The incidence rate of bradycardia was higher in the

experimental group compared with the control group (22.6 vs. 9.7%);

however, this difference was not statistically significant. Blood

loss in the experimental group was 195±52.5 ml, which was

significantly lower than the control group (260.7±71.6 ml;

P=0.007). Surgeon satisfaction scores were significantly higher in

the experimental group compared with the control group [median

(interquartile range): 8 (7) vs. 7

(6); P<0.01].

| Table II.Intraoperative variables. |

Table II.

Intraoperative variables.

| Variable | Experimental group

(n=31) | Control group

(n=31) | P-value |

|---|

| Duration of

surgery, min | 70.3±6.2 | 83.8±8.8 | 0.149 |

| Duration of

anesthesia, min | 86.3±6.0 | 98.0±8.8 | 0.059 |

| Propofol

consumption, µg/kg/min | 101.5±8.2 | 117.9±4.3 | 0.001 |

| Remifentanil

consumption, µg/kg/h | 6.1±0.2 | 9.1±0.4 | 0.045 |

| Incidence of

bradycardiaa | 7 (22.6) | 3 (9.7) | 0.301 |

| Blood loss, ml | 195.0±52.5 | 260.7±71.6 | 0.007 |

| Satisfaction

scoreb | 8 (7) | 7 (6) | <0.01 |

Recovery outcomes

Postoperative recovery data of the patients were

shown in Table III. There was no

significant difference in extubation time between the experimental

group and the control group (17.1±3.2 vs. 14.8±2.8 min; P>0.05).

There was no significant difference in respiratory rate in PACU

between the experimental group and the control group (14.9±1.8 vs.

15.4±1.9 beats min−1). The VAS score of the experimental

group was significantly improved when compared with the control

group [median (interquartile range): 2 (1) vs. 3 (2);

P<0.01]. None of the patients were administered fentanyl for

analgesic recovery. There was no significant difference in

postoperative OAA/S sedation score between the two groups [median

(interquartile range): 1 (1) vs. 1

(1)]. There was no significant

difference in the incidence of PONV between the experimental group

and control group (6.5 vs. 12.9%). There was no case of hypoxia in

either group.

| Table III.Recovery profiles of patients. |

Table III.

Recovery profiles of patients.

| Variable | Experimental group

(n=31) | Control group

(n=31) | P-value |

|---|

| Extubation time,

min | 17.1±3.2 | 14.8±2.8 | 0.422 |

| Respiratory rate in

PACU, breaths/min | 14.9±1.8 | 15.4±1.9 | 0.705 |

| Postoperative

paina | 2 (1) | 3 (2) | <0.010 |

| Postoperative

sedationa | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0.084 |

| Incidence of

PONVb | 2 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 0.671 |

Discussion

The results of the present study suggested that

target-controlled infusion of propofol and remifentanil combined

with dexmedetomidine for FESS was able to reduce the intraoperative

bleeding and improve the satisfaction score of the surgical field,

compared with target-controlled infusion of propofol and

remifentanil alone. Dexmedetomidine also reduced increases in MAP

and HR during tracheal intubation and extubation, and reduced

postoperative pain.

Surgical bleeding is a critical issue in FESS since

bleeding makes the anatomical structure difficult to identify,

leading to serious complications and affecting the outcomes of

surgery (5). Numerous studies have

indicated controlled hypotension with anesthetic or vasoactive

drugs may reduce bleeding and improve the quality of FESS (11,14–16).

However, vasoactive drugs cannot reduce the FESS bleeding when MAP

was controlled at level of 65–75 mmHg (17); conversely, vascular dilation caused

by the drug would increase surgical bleeding and has a negative

impact on the surgical field (14).

Previous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation

between the HR and surgical field bleeding during surgery (18–20).

Compared with nitroglycerin, esmolol reduces bleeding by slowing

down HR and offering an improved surgical approach with only

minimal reduction in MAP (18).

Therefore, FESS should be performed at a lower level of HR

(20) as controlling HR is more

effective on improving the surgical approach than lowering MAP.

Compared with inhalation anesthesia, including isoflurane,

sevoflurane, total intravenous anesthesia with propofol and

remifentanil is able quickly and effectively to lower HR and MAP,

reduce bleeding and provide an improved surgical approach (6–8,21,22). The

reason for this is that inhalation anesthetics dilate blood vessels

and cause reflex tachycardia (23).

Although inhalation anesthetics can reduce MAP, the surgical

approach was still not improved because of the increased HR and

dilated nasal mucosal vessels during FESS (24). Even if balanced anesthesia combined

with esmolol controls the HR, the surgical approach is not

ameliorated compared with total intravenous anesthesia (25).

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2

adrenoceptor agonist that inhibits norepinephrine release, thereby

reducing HR and blood pressure (9).

This effect makes it similar to remifentanil (10,11) and

esmolol (26) in reducing bleeding

and improving the surgical approach. In the present study, total

intravenous anesthesia with propofol and remifentanil combined with

dexmedetomidine maintained HR at a lower level, reduced bleeding

and improved surgical satisfaction scores. In addition, unlike

anesthetic drugs which dilate blood vessels, dexmedetomidine

constricts peripheral arteries and veins (27). Although there is no clear clinical

evidence that dexmedetomidine can contract blood vessels in the

nasal mucosa, it is not ruled out that reducing bleeding may be

associated with vasoconstriction.

In order to reduce bleeding, clinical control of

hypotension typically controls MAP below the normal range in

clinical practice (3). But

hypotension reduces visceral blood flow, which causes important

organ dysfunction, particularly in elderly patients and patients

with organ damage (28). A previous

study indicated that it was not necessary to deliberately decrease

the MAP to a dangerous level for reaching a clear surgical field

(29). In the present study,

administration of dexmedetomidine provided good vision during the

surgery although MAP was maintained at relatively high level (70–80

mmHg), which increased patient safety.

During surgical procedures, the dosage of anesthetic

drugs, including propofol and remifentanil, was increased in order

to control blood pressure (10),

which resulted in deep anesthesia, thereby affecting the long-term

prognosis of patients (30). As an

anesthetic adjuvant, dexmedetomidine may reduce the dosage of

opioids and propofol (31). In the

present study, compared with propofol and remifentanil alone,

dexmedetomidine was able to significantly decrease the mean

infusion rate of propofol (101.5±8.2 vs. 117.9±4.3 µg

kg−1 min−1) and remifentanil (6.1±0.2 vs.

9.1±0.4 µg kg−1 h−1) and reduce the dosage at

the same depth of anesthesia. In cases where it is not possible to

monitor the depth of anesthesia, this effect may be able to avoid

the side effects caused by deep anesthesia.

Dexmedetomidine has also been reported to have

additional advantages, including decreasing stress response during

tracheal intubation (32) and

extubation (33) and improving

postoperative analgesia quality (32). In the present study, dexmedetomidine

reduced MAP and HR during intubation and extubation and reduced the

postoperative VAS value, which is consistent with previous studies

(32,33). Guven et al (34) reported that dexmedetomidine was able

to reduce the incidence of PONV. This conclusion was not reached in

the present study because Guven administered a higher initial dose

of dexmedetomidine compared with the present study (1.0 vs. 0.5 µg

kg−1 h−1).

However, the present study had some limitations.

Firstly, the control group had a relatively high MAP and there was

no patient group with low MAP. Therefore, further analysis is

required to investigate whether dexmedetomidine can reduce FESS

hemorrhage and improve the surgical approach in cases of low MAP.

Secondly, the quality of the surgical approach was assessed by the

same surgeon in the present study, which may be subjective because

different surgeons may give different scores based on proficiency,

mental state and other factors. Therefore, large sample,

multi-center clinical trials are required to confirm the findings

of the present study.

In conclusion, the present study indicated that

propofol and remifentanil target-controlled infusion combined with

dexmedetomidine for FESS reduced intraoperative bleeding and

improved the quality of the surgical field in the case of

relatively high MAP. In addition, dexmedetomidine also reduced the

increase in MAP and HR during intubation and extubation, and

improved the quality of postoperative analgesia.

References

|

1

|

Slack R and Bates G: Functional endoscopic

sinus surgery. Am Fam Physician. 58:707–718. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Cinčikas D, Ivaškevičius J, Martinkėnas JL

and Balseris S: A role of anesthesiologist in reducing surgical

bleeding in endoscopic sinus surgery. Medicina (Kaunas).

46:730–734. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Degoute CS: Controlled hypotension: A

guide to drug choice. Drugs. 67:1053–1076. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ge YL, Lv R, Zhou W, Ma XX, Zhong TD and

Duan ML: Brain damage following severe acute normovolemic

hemodilution in combination with controlled hypotension in rats.

Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 51:1331–1337. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Amorocho MR and Sordillo A: Anesthesia for

functional endoscopic sinus surgery: A review. Anesthesiol Clin.

28:497–504. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tirelli G, Bigarini S, Russolo M,

Lucangelo U and Gullo A: Total intravenous anaesthesia in

endoscopic sinus-nasal surgery. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital.

24:137–144. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Miłoński J, Zielińska-Bliźniewska H,

Golusiński W, Urbaniak J, Sobański R and Olszewski J: Effects of

three different types of anaesthesia on perioperative bleeding

control in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 270:2045–2050. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Marzban S, Haddadi S, Nia Mahmoudi H,

Heidarzadeh A, Nemati S and Nabi Naderi B: Comparison of surgical

conditions during propofol or isoflurane anesthesia for endoscopic

sinus surgery. Anesth Pain Med. 3:234–238. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gerlach AT and Dasta JF: Dexmedetomidine:

An updated review. Ann Pharmacother. 41:245–252. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim H, Ha SH, Kim CH, Lee SH and Choi SH:

Efficacy of intraoperative dexmedetomidine infusion on

visualization of the surgical field in endoscopic sinus surgery.

Korean J Anesthesiol. 68:449–454. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lee J, Kim Y, Park C, Jeon Y, Kim D, Joo J

and Kang H: Comparison between dexmedetomidine and remifentanil for

controlled hypotension and recovery in endoscopic sinus surgery.

Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 122:421–426. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yeganeh N, Roshani B, Latifi H and Almasi

A: Comparison of target-controlled infusion of sufentanil and

remifentanil in blunting hemodynamic response to tracheal

intubation. J Inj Violence Res. 5:101–107. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hall DL, Weaver J, Ganzberg S, Rashid R

and Wilson S: Bispectral EEG index monitoring of high-dose nitrous

oxide and low-dose sevoflurane sedation. Anesth Prog. 49:56–62.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Boezaart AP, van der Merwe J and Coetzee

A: Comparison of sodium nitroprusside- and esmolol-induced

controlled hypotension for functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Can

J Anaesth. 42:373–376. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Crawley BK, Barkdull GC, Dent S, Bishop M

and Davidson TM: Relative hypotension and image guidance: Tools for

training in sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

135:994–999. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Cardesín A, Pontes C, Rosell R, Escamilla

Y, Marco J, Escobar MJ and Bernal-Sprekelsen M: Hypotensive

anaesthesia and bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery: An

observational study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 271:1505–1511.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Jacobi KE, Böhm BE, Rickauer AJ, Jacobi C

and Hemmerling TM: Moderate controlled hypotension with sodium

nitroprusside does not improve surgical conditions or decrease

blood loss in endoscopic sinus surgery. J Clin Anesth. 12:202–207.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Srivastava U, Dupargude AB, Kumar D, Joshi

K and Gupta A: Controlled hypotension for functional endoscopic

sinus surgery: Comparison of esmolol and nitroglycerine. Indian J

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 65:440–444. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wormald PJ, Athanasiadis T, Rees G and

Robinson S: An evaluation of effect of pterygopalatine fossa

injection with local anesthetic and adrenalin in the control of

nasal bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol.

19:288–292. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Nair S, Collins M, Hung P, Rees G, Close D

and Wormald PJ: The effect of beta-blocker premedication on the

surgical field during endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope.

114:1042–1046. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Eberhart LH, Folz BJ, Wulf H and Geldner

G: Intravenous anesthesia provides optimal surgical conditions

during microscopic and endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope.

113:1369–1373. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wormald PJ, van Renen G, Perks J, Jones JA

and Langton-Hewer CD: The effect of the total intravenous

anesthesia compared with inhalational anesthesia on the surgical

field during endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol. 19:514–520.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Toivonen J, Virtanen H and Kaukinen S:

Deliberate hypotension induced by labetalol with halothane,

enflurane or isoflurane for middle-ear surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol

Scand. 33:283–289. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Snidvongs K, Tingthanathikul W,

Aeumjaturapat S and Chusakul S: Dexmedetomidine improves the

quality of the operative field for functional endoscopic sinus

surgery: Systematic review. J Laryngol Otol. 129:S8–13. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ragab SM and Hassanin MZ: Optimizing the

surgical field in pediatric functional endoscopic sinus surgery: A

new evidence-based approach. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 142:48–54.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Shams T, El Bahnasawe NS, Abu-Samra M and

El-Masry R: Induced hypotension for functional endoscopic sinus

surgery: A comparative study of dexmedetomidine versus esmolol.

Saudi J Anaesth. 7:175–180. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Talke P, Lobo E and Brown R: Systemically

administered alpha2-agonist-induced peripheral vasoconstriction in

humans. Anesthesiology. 99:65–70. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Larsen R and Kleinschmidt S: Controlled

hypotension. Anaesthesist. 44:291–308. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sieśkiewicz A, Drozdowski A and Rogowski

M: The assessment of correlation between mean arterial pressure and

intraoperative bleeding during endoscopic sinus surgery in patients

with low heart rate. Otolaryngol Pol. 64:225–228. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Monk TG, Saini V, Weldon BC and Sigl JC:

Anesthetic management and one-year mortality after noncardiac

surgery. Anesth Analg. 100:4–10. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Arcangeli A, D'Alò C and Gaspari R:

Dexmedetomidine use in general anaesthesia. Curr Drug Targets.

10:687–695. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Gunalan S, Venkatraman R, Sivarajan G and

Sunder P: Comparative evaluation of bolus administration of

dexmedetomidine and fentanyl for stress attenuation during

laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation. J Clin Diagn Res.

9:UC06–UC09. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fan Q, Hu C, Ye M and Shen X:

Dexmedetomidine for tracheal extubation in deeply anesthetized

adult patients after otologic surgery: A comparison with

remifentanil. BMC Anesthesiol. 15:1062015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Guven DG, Demiraran Y, Sezen G, Kepek O

and Iskender A: Evaluation of outcomes in patients given

dexmedetomidine in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Ann Otol

Rhinol Laryngol. 120:586–592. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|