Introduction

Wilms tumor (WT) is one of the most common types of

pediatric solid tumor, with a prevalence of 1 in 10,000 children

worldwide (1). WT typically occurs

in healthy children; however, ~10% of children who have congenital

anomalies, including Denys-Drash syndrome and Beckwith-Wiedemann

syndrome, have been reported to exhibit a predisposition to this

type of cancer (2,3). WT is an embryological tumor that is

composed of a variable mixture of stromal, blastemal and epithelial

elements and is histologically similar to renal embryogenesis

(4). It has been verified that

certain genetic mutations, including those in Wilms tumor 1 (WT1),

Wilms tumor on the X (WTX) and catenin b1 (CTNNB1), are associated

with WT susceptibility (5–7). WT1 is closely associated with renal

development and its mutations account for ~20% of WT cases

(8). It has been identified from a

large number of WT cases that CTNNB1 mutations overlap with the WT1

mutation while the WTX mutation is predominantly mutually exclusive

(9). Furthermore, a number of

studies have suggested the involvement of various genes and

cellular signaling pathways in the occurrence and development of WT

(10,11). A previous study indicated that KRAS

mutations participate in the WT occurrence by activating the

PI3K/AKT pathway (12). However, the

definite molecular mechanisms remain unknown. Therefore, it is

necessary to study the underlying molecular mechanisms of WT to

prevent tumorigenesis and develop effective therapeutic

measures.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs/miRs) are a class of small

non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by

post-transcriptionally binding to the 3′ untranslated region of

target mRNAs, inducing mRNA degradation or silencing (13). In previous decades, a large number of

miRNAs have been identified in humans and numerous previous studies

have demonstrated their role of acting as oncogenes or tumor

suppressors by regulating tumor occurrence, progression and

survival (14,15). For example, Zhu et al

(16) reported that miR-92a-3p

suppresses the proliferation, migration and invasion of WT cells by

modulating the NOTCH1 signaling pathway. Therefore, identification

of differentially expressed miRNAs (DEMs) has been demonstrated to

be a promising strategy in the identification of novel biomarkers

for the early diagnosis or prognosis of WT.

Application of microarray analysis or

high-throughput sequencing can quickly identify differentially

expressed genes (DEGs) and DEMs in tumor samples, and these are

promising techniques in clinical research, including molecular

classification, targeted drug discovery and survival prediction

(17,18). The present study identified DEGs in

WT using the GSE66405 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus

(GEO) database and data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

database (19). Additionally,

analysis of DEMs was performed using the GSE57370 dataset and TCGA

database (20). Overall, the present

study aimed to provide information that would promote the

understanding of the molecular mechanisms of WT.

Materials and methods

Raw data

All datasets used in the present study were

downloaded from the GEO (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and TCGA

(https://cancergenome.nih.gov/) databases

(21). The GSE66405 dataset includes

mRNA expression profiles of 28 WT and four paracancerous normal

samples, which were determined using the Agilent-039494 SurePrint

G3 Human GE v2 8×60K (GPL17077) platform (17). The GSE57370 dataset includes miRNA

expression profiles of 62 WT and four paracancerous normal samples,

which were determined using the Agilent-031181

Unrestricted_Human_miRNA_V16.0_Microarray (GPL16770) platform

(18). In addition, further mRNA and

miRNA expression profiles were downloaded from the TCGA WT datasets

(mRNA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository?facetTab=files&filters=%7B%22op%22%3A%22and%22%2C%22content%22%3A%5B%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22cases.project.project_id%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22TARGET-WT%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.analysis.workflow_type%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22HTSeq%20-%20Counts%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.experimental_strategy%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22RNA-Seq%22%5D%7D%7D%5D%7D;

miRNA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository?facetTab=files&filters=%7B%22op%22%3A%22and%22%2C%22content%22%3A%5B%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22cases.project.project_id%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22TARGET-WT%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.data_category%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22Transcriptome%20Profiling%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.data_type%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22miRNA%20Expression%20Quantification%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.experimental_strategy%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22miRNA-Seq%22%5D%7D%7D%5D%7D&searchTableTab=files),

which included 6 paracancerous normal renal tissues and 126 or 132

tumor samples, respectively.

Identification of DEGs and DEMs

The R 3.5.0 software (https://www.r-project.org/) was used to identify the

DEGs between WT and normal samples in the GSE66405 dataset using

the limma package with the following cut-off criteria: Fold change

(FC)>2 and P<0.05 (22).

Additionally, the DEGs in the TCGA WT dataset were determined using

the edgeR package with FC>2 and a false discovery rate (FDR)

adjusted P<0.05 as the cut-off criteria (23). Similarly, DEMs were screened with

FC>1 and P<0.05 in GSE57370, and FC>1 and FDR adjusted

P<0.05 in the TCGA dataset. The limma and edgeR packages were

installed using Bioconductor version 3.7 (https://www.bioconductor.org/).

Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway

enrichment analysis

The Database for Annotation, Visualization and

Integrated Discovery (DAVID 6.8; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to perform GO

and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway

enrichment analyses of the DEGs. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant result (24).

Protein-protein interaction (PPI)

network construction and module analysis

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting

Genes (STRING 11.0; http://string.embl.de/) database was used to obtain

PPI information for the DEGs, and interactions with a combined

score >0.7 were considered as significant protein pairs

(25). Subsequently, Cytoscape 3.6.1

software was used to visualize the PPI network and Molecular

Complex Detection (MCODE) was used to screen central modules of the

network with the following cut-off criteria: Degree=2, node score

cut-off=0.2, k-score=2 and maximum depth=100 (26,27).

Validation of hub genes

Oncomine (https://www.oncomine.org), an online microarray

database, was utilized to collect and analyze gene expression data

for tumor and paracarcinoma normal samples. The Yusenko et

al (28) renal dataset was used

to verify the differential expression of hub genes between four WT

and five normal renal samples. The log2 median-centered intensity

value was visualized by GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad

Software, Inc.).

Prediction of miRNA targets

Target genes of the DEMs in the GSE57370 dataset and

TCGA dataset were predicted using TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), miRTarBase

(http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/index.php) and

miRDB (http://mirdb.org/). Only targets identified by

all three databases were further analyzed by comparing them with

previously identified DEGs (29).

Furthermore, the predicted mRNA-miRNA regulatory interactions were

visualized using Cytoscape version 3.6.1.

Results

Identification of common DEGs in

GSE66405 and TCGA

A total of 996 DEGs in GSE66405 were identified

according to the aforementioned cut-off criteria, including 280

upregulated and 716 downregulated genes (Fig. 1A; Table

SI). In addition, 6,608 DEGs were identified in the TCGA

dataset, including 3,607 upregulated and 3,001 downregulated genes

(Fig. 1B; Table SII). A Venn diagram was used to

present the overlapping 181 upregulated and 432 downregulated genes

identified in both datasets (Fig. 1C and

D).

GO term and KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis of DEGs

To gain further insights into the function and

mechanisms of WT, the identified common DEGs were uploaded to DAVID

to perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses. The top 10

terms of each analysis with the lowest P-values are presented in

Fig. 2. According to KEGG pathway

analysis, the DEGs were predominantly enriched in the ‘Metabolic

pathway’. In addition, certain DEGs were significantly involved in

‘peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) signaling

pathway’ and ‘Protein digestion and absorption’. GO biological

process terms revealed that the DEGs were primarily enriched in

‘response to drug’, ‘ion transmembrane transport’ and ‘excretion’.

At the cellular component level, the DEGs were mainly enriched in

‘integral component of membrane’, ‘extracellular exosome’ and

‘plasma membrane’. At the molecular function level, the DEGs

predominantly served a role in ‘transporter activity’ and ‘heparin

binding’.

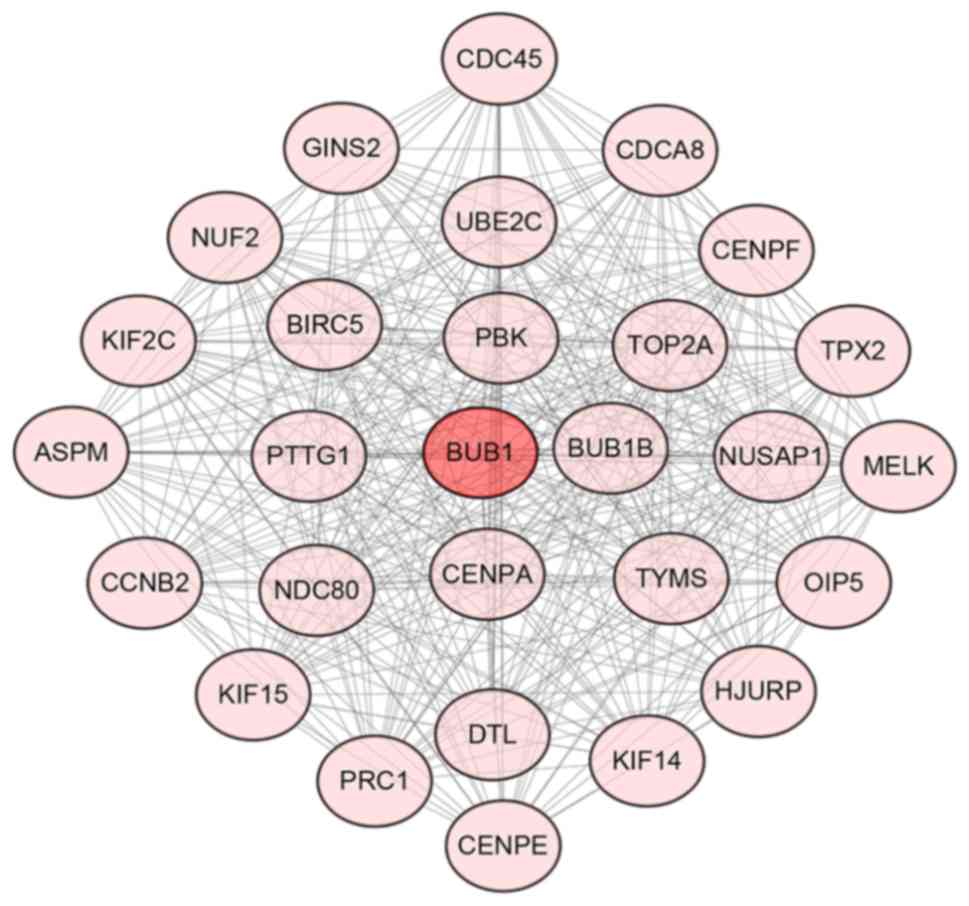

PPI network analysis

All 613 common DEGs were mapped into a PPI network

using the STRING online database and the network was visualized

using Cytoscape (Fig. S1). BUB1

mitotic checkpoint serine (BUB1) was identified as the gene with

the highest degree in the overall network, with a degree of 33.

Fig. 3 presents the most significant

gene module of the PPI network, which included 28 genes with 366

edges. In addition, key pathways and GO terms of these hub genes

are presented in Fig. 4 and Table SIII. These hub genes were

predominantly involved in the cell cycle [BUB1, BUB1B mitotic

checkpoint serine/threonine kinase B (BUB1B), cell division cycle

protein 45 (CDC45), cyclin B2 (CCNB2) and pituitary

tumor-transforming 1 (PTTG1)] and oocyte meiosis pathways (BUB1,

CCNB2 and PTTG1). Furthermore, BUB1 was revealed to be involved in

all of the GO terms identified. As a result, BUB1 was considered to

be a central hub gene.

Validation of hub genes in the cell

cycle pathway

To further validate the results, the present study

examined the expression levels of five hub genes (BUB1, BUB1B,

CDC45, CCNB2 and PTTG1) using the Oncomine database. As indicated

by the Yusenko Renal dataset, all five genes were significantly

upregulated in tumor samples compared with in normal samples

(P<0.05; Fig. 5). This suggested

that dysregulation of the cell cycle pathway, as well as

alterations in the mRNA expression levels of these genes, may be

closely associated with WT.

Identification of common DEMs in

GSE57370 and the TCGA dataset

A total of 79 and 167 DEMs were identified using the

GSE57370 and TCGA datasets, respectively, including 26 and 101

upregulated, and 53 and 66 downregulated miRNAs, respectively

(Fig. 6A and B; Tables SIV and SV). Venn diagrams present the 29

overlapping miRNAs, which included 6 upregulated and 23

downregulated miRNAs (Fig. 6C and

D).

Prediction of a regulatory network of

DEMs-DEGs

A total of 879 target genes of the 6 upregulated and

23 downregulated miRNAs were predicted by the TargetScan,

miRTarBase and miRDB databases. Among the 879 genes, 19 were

identified to overlap with the identified DEGs (29–31).

Subsequently, the present study constructed a potential regulatory

network of the DEMs-DEGs, which was visualized using Cytoscape

(Fig. 7). In addition, Table SVI presents the GO term and KEGG

pathway enrichment analyses of the 19 overlapping genes. Among

these genes, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein family member 3

(WASF3) and MARCKS like 1 (MARCKSL1) were enriched in the ‘Fc gamma

R-mediated phagocytosis pathway’. Subsequently, the present study

validated their expression using Oncomine and the Yusenko Renal

dataset and revealed that the two genes were overexpressed in WT

compared with in the normal group. When referring to the expression

profile of DEMs and the miRNA-mRNA network, downregulated

hsa-miR-200b, hsa-miR-429 and hsa-miR-30c-2 may be the upstream

regulatory elements of WASF3 and MARCKSL1 (Fig. 8).

Discussion

WT is a serious threat to the health of children and

develops as a result of abnormalities of various genes which are

normally responsible for cellular growth, proliferation and

differentiation (32,33). It has been reported that ~5% of

children have mutations in WT1 or epigenetic defects at chromosome

11p15, which are predispositions for WT (5,34). In

previous decades, a number of genes, including CTNNB1, WTX and

tumor protein p53, have been reported to be involved in the

tumorigenesis and progression of WT (35–37).

Therefore, identification of key genes is vital for understanding

the pathogenesis and abnormal biological behavior of WT, and to

identify novel therapeutic targets of WT.

First, the present study analyzed available

microarray and RNA-sequencing data from the GEO and TCGA databases

to identify significant DEGs and DEMs, and 613 significant DEGs

were selected by bioinformatics analysis. DAVID was used to perform

further analysis of these DEGs to identify their potential

associated cellular signaling pathways and functions. KEGG pathway

analysis revealed that 65 DEGs of WT were enriched in ‘Metabolic

pathways’, 12 were enriched in the ‘PPAR signaling pathway’ and 12

were enriched in ‘Protein digestion and absorption’. GO term

analysis indicated that DEGs were involved in the ‘response to

drug’, ‘ion transmembrane transport’ and ‘excretion’ biological

processes terms. Furthermore, the DEGs were demonstrated to serve a

role in ‘transporter activity’ and ‘heparin binding’ at the

molecular function level.

Subsequently, according to PPI network construction

and module analysis, a hub gene module was identified. This hub

gene module contained 28 upregulated genes, and BUB1 was considered

as the central gene. BUB1 was identified as the gene with the

highest degree (33) in the network,

while centromere protein A, ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 C and

kinesin family member 2C each had a degree of 32. KEGG and GO

analyses demonstrated that these 28 hub genes were mainly involved

in ‘Cell cycle’ and ‘Oocyte meiosis pathway’, and were also

associated with multiple processes of mitosis according to the

molecular biological function terms. Expression validation based on

the Oncomine database was performed to investigate the expression

levels of BUB1, BUB1B, CDC45, CCNB2 and PTTG1, which were all

associated with the ‘Cell cycle pathway’. As expected, all five

genes were upregulated in tumor tissues compared with in normal

samples. Therefore, it may be hypothesized that disorders of the

cell cycle pathway and associated genes may contribute to the

occurrence of WT.

Cell cycle progression consists of five known

phases: G0 (gap 0), G1 (gap 1), S (DNA

synthesis), G2 (gap 2) and M (mitosis) phase. A number

of checkpoints function between these phases to ensure that the

integrity of cellular components and the fidelity of DNA synthesis

are monitored (38). As is well

understood, an abnormal distribution of cells throughout the cell

cycle is a hallmark of human cancer, due to accumulating

alterations of genes in the cell cycle pathway possibly resulting

in impaired abilities of cell division, cell proliferation and

response to DNA damage (39,40). BUB1, a mitotic checkpoint protein,

has been demonstrated to be overexpressed in various types of

cancer, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate cancer, and

has been associated with the proliferation, migration and invasion

of tumor cells (41,42). Furthermore, a number of studies have

suggested that BUB1 may be a biomarker for the clinical prognosis

of numerous types of tumor, including breast and gastric cancer

(43,44). Therefore, it is worth investigating

the role of BUB1 in WT further.

miRNAs are popularly applied in the diagnosis and

clinical prognosis of various types of tumor due to their

regulatory role of mRNAs, which affects the malignant behavior of

tumor cells (45,46). In addition, due to an increasing

amount of attention for miRNAs, a number of miRNAs have been

identified to be involved in the occurrence, development and

survival of tumor (47,48). Therefore, screening key miRNAs may be

beneficial to further investigate their specific roles in WT. By

integrating the miRNA microarray data in GSE57370 with the

miRNA-sequencing data in the TCGA dataset, 29 overlapping DEMs were

identified in the present study. These DEMs may serve important

roles in WT.

Furthermore, TargetScan, miRTarBase and miRDB were

used to predict the target genes of the DEMs and only genes

identified by all three databases were further analyzed.

Subsequently, 879 target genes were integrated with the

aforementioned DEGs, and 19 overlapping genes were identified. A

DEMs-DEGs network was constructed to reveal potential regulatory

pathways by which the 16 DEMs and 19 DEGs serve their roles. In

KEGG pathway analysis, two genes were revealed to be involved in

the Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis pathway. It was demonstrated

that WASF3 and MARCKSL1 were highly expressed in the tumor samples

in the Yusenko Renal dataset. Based on the expression profiles of

the DEMs and the miRNA-mRNA network, downregulated hsa-miR-200b and

hsa-miR-429 may be the upstream regulatory elements of WASF3, and

hsa-miR-30c-2 may be the regulator of MARCKSL1. It has been

reported that miR-200b may inhibit the growth and motility of

breast cancer cells (49). miR-429

can suppress the cell proliferation, migration and invasion of

nasopharyngeal carcinoma (50).

Similarly, miR-30c-2 has been demonstrated to be involved in cancer

cell proliferation and apoptosis (51). Additionally, WASF3 and MARCKSL1 have

been reported to be associated with malignant behaviors of certain

tumor types, including bladder and breast cancer (52,53).

Therefore, one may speculate that the three regulatory pathways of

miR-200b/WASF3, miR-429/WASF3 and miR-30c-2/MARCKSL1 may serve

significant roles in WT. However, this remains to be validated by

future experiments.

In the present study, five hub genes were

identified, and these were associated with the cell cycle pathway

and may be potential biomarkers of WT. Furthermore, the present

study predicted potential miRNA-mRNA regulatory pathways by

constructing an interaction network. These results may direct

experimental investigations regarding the molecular mechanisms in

WT.

In conclusion, the present study identified 613 DEGs

and 29 DEMs by bioinformatics analysis, which may be potential

biomarkers for the occurrence of WT. By screening the hub module in

a PPI network and performing functional enrichment analyses, five

hub genes (BUB1, BUB1B, CDC45, CCNB2 and PTTG1) associated with the

cell cycle and mitosis were identified. These may serve important

roles in WT. In addition, differential expression levels of these

genes were verified using the Oncomine database. Furthermore, the

present study predicted potential regulatory mechanisms of the DEMs

and DEGs in WT, and aimed to assist further molecular biological

investigations that may verify these mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Natural Science Funding of China (grant nos. 81600514 and

81670608).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the

current study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus

repository (accession numbers GSE66405 and GSE57370) and TCGA

repository (mRNA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository?facetTab=files&filters=%7B%22op%22%3A%22and%22%2C%22content%22%3A%5B%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22cases.project.project_id%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22TARGET-WT%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.analysis.workflow_type%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22HTSeq%20-%20Counts%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.experimental_strategy%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22RNA-Seq%22%5D%7D%7D%5D%7D;

miRNA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository?facetTab=files&filters=%7B%22op%22%3A%22and%22%2C%22content%22%3A%5B%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22cases.project.project_id%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22TARGET-WT%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.data_category%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22Transcriptome%20Profiling%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.data_type%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22miRNA%20Expression%20Quantification%22%5D%7D%7D%2C%7B%22op%22%3A%22in%22%2C%22content%22%3A%7B%22field%22%3A%22files.experimental_strategy%22%2C%22value%22%3A%5B%22miRNA-Seq%22%5D%7D%7D%5D%7D&searchTableTab=files).

The remaining datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

WW, MT and WZ designed the study and contributed to

language editing and proofreading. RL, ZQ, YW, LZ and XG retrieved

and processed the data. LZ and XZ analyzed the data. LZ and XG

wrote and edited the manuscript, and prepared figures and tables.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Charlton J, Pavasovic V and

Pritchard-Jones K: Biomarkers to detect Wilms tumors in pediatric

patients: Where are we now? Future Oncol. 11:2221–2234. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Scott RH, Stiller CA, Walker L and Rahman

N: Syndromes and constitutional chromosomal abnormalities

associated with Wilms tumour. J Med Genet. 43:705–715. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hung IJ, Chang WH, Yang CP, Jaing TH,

Liang DC, Lin KH, Lin DT, Hsiao CC, Hsieh YL, Chen JS, et al:

Epidemiology, clinical features and treatment outcome of Wilms'

tumor in Taiwan: A report from Taiwan pediatric oncology group. J

Formos Med Assoc. 103:104–111. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Al-Hussain T, Ali A and Akhtar M: Wilms

tumor: An update. Adv Anat Pathol. 21:166–173. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Segers H, Kersseboom R, Alders M, Pieters

R, Wagner A and van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM: Frequency of WT1 and

11p15 constitutional aberrations and phenotypic correlation in

childhood Wilms tumour patients. Eur J Cancer. 48:3249–3256. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Fukuzawa R, Holman SK, Chow CW,

Savarirayan R, Reeve AE and Robertson SP: WTX mutations can occur

both early and late in the pathogenesis of Wilms tumour. J Med

Genet. 47:791–794. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li CM, Kim CE, Margolin AA, Guo M, Zhu J,

Mason JM, Hensle TW, Murty VV, Grundy PE, Fearon ER, et al: CTNNB1

mutations and overexpression of Wnt/beta-catenin target genes in

WT1-mutant Wilms' tumors. Am J Pathol. 165:1943–1953. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Haber DA, Buckler AJ, Glaser T, Call KM,

Pelletier J, Sohn RL, Douglass EC and Housman DE: An internal

deletion within an 11p13 zinc finger gene contributes to the

development of Wilms' tumor. Cell. 61:1257–1269. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Scott RH, Murray A, Baskcomb L, Turnbull

C, Loveday C, Al-Saadi R, Williams R, Breatnach F, Gerrard M, Hale

J, et al: Stratification of Wilms tumor by genetic and epigenetic

analysis. Oncotarget. 3:327–335. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fu W, Zhuo Z, Hua RX, Fu K, Jia W, Zhu J,

Zhang J, Cheng J, Zhou H, Xia H, et al: Association of KRAS and

NRAS gene polymorphisms with Wilms tumor risk: A four-center

case-control study. Aging (Albany NY). 11:1551–1563. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Diets IJ, Hoyer J, Ekici AB, Popp B,

Hoogerbrugge N, van Reijmersdal SV, Bhaskaran R, Hadjihannas M,

Vasileiou G, Thiel CT, et al: TRIM28 haploinsufficiency predisposes

to Wilms tumor. Int J Cancer. 145:941–951. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Polosukhina D, Love HD, Correa H, Su Z,

Dahlman KB, Pao W, Moses HL, Arteaga CL, Lovvorn HN III, Zent R and

Clark PE: Functional KRAS mutations and a potential role for

PI3K/AKT activation in Wilms tumors. Mol Oncol. 11:405–421. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics,

biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S,

Cimmino A, Petrocca F, Visone R, Iorio M, Roldo C, Ferracin M, et

al: A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines

cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:2257–2261. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu GL, Yang HJ, Liu B and Liu T: Effects

of microRNA-19b on the proliferation, apoptosis, and migration of

Wilms' tumor cells via the PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J Cell

Biochem. 118:3424–3434. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zhu S, Zhang L, Zhao Z, Fu W, Fu K, Liu G

and Jia W: MicroRNA-92a-3p inhibits the cell proliferation,

migration and invasion of Wilms tumor by targeting NOTCH1. Oncol

Rep. 40:571–578. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu

VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr and Kinzler KW: Cancer genome landscapes.

Science. 339:1546–1558. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Guo Y, Bao Y, Ma M and Yang W:

Identification of key candidate genes and pathways in colorectal

cancer by integrated bioinformatical analysis. Int J Mol Sci.

18:E7222017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ludwig N, Werner TV, Backes C, Trampert P,

Gessler M, Keller A, Lenhof HP, Graf N and Meese E: Combining miRNA

and mRNA expression profiles in Wilms tumor subtypes. Int J Mol

Sci. 17:4752016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wegert J, Ishaque N, Vardapour R, Geörg C,

Gu Z, Bieg M, Ziegler B, Bausenwein S, Nourkami N, Ludwig N, et al:

Mutations in the SIX1/2 pathway and the DROSHA/DGCR8 miRNA

microprocessor complex underlie high-risk blastemal type Wilms

tumors. Cancer Cell. 27:298–311. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tomczak K, Czerwińska P and Wiznerowicz M:

The cancer genome atlas (TCGA): An immeasurable source of

knowledge. Contemp Oncol (Pozn). 19:A68–A77. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Diboun I, Wernisch L, Orengo CA and

Koltzenburg M: Microarray analysis after RNA amplification can

detect pronounced differences in gene expression using limma. BMC

Genomics. 7:2522006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ and Smyth GK:

EdgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis

of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 26:139–140. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang

J, Gao W, Lane HC and Lempicki RA: DAVID: Database for annotation,

visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 4:P32003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S,

Forslund K, Heller D, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Roth A, Santos

A, Tsafou KP, et al: STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction

networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res.

43:D447–D452. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang PL

and Ideker T: Cytoscape 2.8: New features for data integration and

network visualization. Bioinformatics. 27:431–432. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bader GD and Hogue CW: An automated method

for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction

networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 4:22003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yusenko MV, Kuiper RP, Boethe T, Ljungberg

B, van Kessel AG and Kovacs G: High-resolution DNA copy number and

gene expression analyses distinguish chromophobe renal cell

carcinomas and renal oncocytomas. BMC Cancer. 9:1522009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW and Bartel DP:

Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs.

Elife. 4:050052015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Chou CH, Chang NW, Shrestha S, Hsu SD, Lin

YL, Lee WH, Yang CD, Hong HC, Wei TY, Tu SJ, et al: miRTarBase

2016: Updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target

interactions database. Nucleic Acids Res. 44:D239–D247. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Wong N and Wang X: miRDB: An online

resource for microRNA target prediction and functional annotations.

Nucleic Acids Res. 43:D146–D152. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Pierce J, Murphy AJ, Panzer A, de

Caestecker C, Ayers GD, Neblett D, Saito-Diaz K, de Caestecker M

and Lovvorn HN III: SIX2 effects on wilms tumor biology. Transl

Oncol. 7:800–811. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yap LW, Brok J and Pritchard-Jones K: Role

of CD56 in normal kidney development and Wilms tumorigenesis. Fetal

Pediatr Pathol. 36:62–75. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nordenskjöld A, Friedman E, Sandstedt B,

Söderhäll S and Anvret M: Constitutional and somatic mutations in

the WT1 gene in Wilms' tumor patients. Int J Cancer. 63:516–522.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Alexandrescu S, Akhavanfard S, Harris MH

and Vargas SO: Clinical, pathologic, and genetic features of Wilms

tumors with WTX gene mutation. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 20:105–111.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Deng C, Dai R, Li X and Liu F: Genetic

variation frequencies in Wilms' tumor: A meta-analysis and

systematic review. Cancer Sci. 107:690–699. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ooms AH, Gadd S, Gerhard DS, Smith MA,

Guidry Auvil JM, Meerzaman D, Chen QR, Hsu CH, Yan C, Nguyen C, et

al: Significance of TP53 mutation in Wilms tumors with diffuse

anaplasia: A report from the children's oncology group. Clin Cancer

Res. 22:5582–5591. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dominguez-Brauer C, Thu KL, Mason JM,

Blaser H, Bray MR and Mak TW: Targeting mitosis in cancer: Emerging

strategies. Mol Cell. 60:524–536. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Alimbetov D, Askarova S, Umbayev B, Davis

T and Kipling D: Pharmacological targeting of cell cycle, apoptotic

and cell adhesion signaling pathways implicated in chemoresistance

of cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 19:E16902018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Knudsen ES, Pruitt SC, Hershberger PA,

Witkiewicz AK and Goodrich DW: Cell cycle and beyond: Exploiting

new RB1 controlled mechanisms for cancer therapy. Trends Cancer.

5:308–324. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Xu B, Xu T, Liu H, Min Q, Wang S and Song

Q: miR-490-5p suppresses cell proliferation and invasion by

targeting BUB1 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Pharmacology.

100:269–282. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Fu X, Chen G, Cai ZD, Wang C, Liu ZZ, Lin

ZY, Wu YD, Liang YX, Han ZD, Liu JC and Zhong WD: Overexpression of

BUB1B contributes to progression of prostate cancer and predicts

poor outcome in patients with prostate cancer. Onco Targets Ther.

9:2211–2220. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Stahl D, Braun M, Gentles AJ, Lingohr P,

Walter A, Kristiansen G and Gütgemann I: Low BUB1 expression is an

adverse prognostic marker in gastric adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget.

8:76329–76339. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ocaña A, Pérez-Peña J, Díez-González L,

Sánchez-Corrales V, Templeton A, Seruga B, Amir E and Pandiella A:

Transcriptomic analyses identify association between mitotic

kinases, PDZ-binding kinase and BUB1, and clinical outcome in

breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 156:1–8. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Wei YT, Guo DW, Hou XZ and Jiang DQ:

miRNA-223 suppresses FOXO1 and functions as a potential tumor

marker in breast cancer. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand).

63:113–118. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sharma P and Sharma R: miRNA-mRNA

crosstalk in esophageal cancer: From diagnosis to therapy. Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 96:449–462. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhang D, Zhao L, Shen Q, Lv Q, Jin M, Ma

H, Nie X, Zheng X, Huang S, Zhou P, et al: Down-regulation of

KIAA1199/CEMIP by miR-216a suppresses tumor invasion and metastasis

in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 140:2298–2309. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Jia AY, Castillo-Martin M, Bonal DM,

Sánchez-Carbayo M, Silva JM and Cordon-Cardo C: MicroRNA-126

inhibits invasion in bladder cancer via regulation of ADAM9. Br J

Cancer. 110:2945–2954. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Lv Z, Wei J, You W, Wang R, Shang J, Xiong

Y, Yang H, Yang X and Fu Z: Disruption of the

c-Myc/miR-200b-3p/PRDX2 regulatory loop enhances tumor metastasis

and chemotherapeutic resistance in colorectal cancer. J Transl Med.

15:2572017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Wang Z, Zhu Z, Lin Z, Luo Y, Liang Z,

Zhang C, Chen J and Peng P: miR-429 suppresses cell proliferation,

migration and invasion in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by

downregulation of TLN1. Cancer Cell Int. 19:1152019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Tang CT, Liang Q, Yang L, Lin XL, Wu S,

Chen Y, Zhang XT, Gao YJ and Ge ZZ: RAB31 targeted by miR-30c-2-3p

regulates the GLI1 signaling pathway, affecting gastric cancer cell

proliferation and apoptosis. Front Oncol. 8:5542018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jin H, Xie Q, Guo X, Xu J, Wang A, Li J,

Zhu J, Wu XR, Huang H and Huang C: p63α protein up-regulates heat

shock protein 70 expression via E2F1 transcription factor 1,

promoting Wasf3/Wave3/MMP9 signaling and bladder cancer invasion. J

Biol Chem. 292:15952–15963. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Kim BR, Dong SM, Seo SH, Lee JH, Lee JM,

Lee SH and Rho SB: Lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2) controls

tumor-associated cell proliferation through the interaction with

MARCKSL1. Cell Signal. 26:1765–1773. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|