Introduction

Hepatitis A and E are common acute, self-limited

viral infections produced by hepatitis A virus (HAV) and hepatitis

E virus (HEV), respectively, generally acquired by the fecal-oral

route, via either person-to-person contact or ingestion of

contaminated food or water (1,2). A

rare modality of transmission is blood transfusion, in the case of

contaminated blood or when the donor is in the viremic prodromal

phase of the infection at the time of blood donation which is more

frequently encountered in the transmission of hepatitis B or C

(3). HAV infection affects 120

million people annually worldwide, especially children (4). By contrast, World Health Organization

(WHO) estimated that HEV causes 20 million new infections annually

and over 55,000 deaths (5).

Identified for the first time in 1983, in sporadic cases of

infections in low-income countries from Asia and Africa, the number

of cases of HEV infections has continuously increased over the last

15 years, especially in developed countries (6). Currently, HEV infection represents a

worldwide public health issue (7).

Netherlands reported a 5-fold increased incidence of HEV infections

in 2014 compared to previous years, while the number of cases in

Germany went up 40-fold in the last 10 years (8,9).

In both HAV and HEV infections, the levels of

endemicity are strongly correlated with hygienic and sanitary

conditions of each geographic area and are divided into areas with

high, intermediate or low endemicity as defined by results of

age-seroprevalence surveys (10,11). A

special interest is given to middle-income countries with varied

epidemiological profiles but are an important factor in the spread

of fecal-oral transmitted infections through international economic

and social globalization (12,13).

This process of socio-economic interdependence may lead to

significant changes in the epidemiological patterns of infections.

Located in southeastern Europe, Romania is part of this

globalization process due to a growing number of foreign visitors

or international food trade. Romania has an intermediate endemicity

of HAV infection (14). On the

other hand, the seroprevalence of HEV infection in Romania is still

unknown. Based on studies of seroprevalence of IgG HEV antibodies,

an incidence of 12% was noted in 2009. Further studies revealed an

increased number of cases in Romania by 14% among medical staff and

up to 28% among the general population (6,14).

In this context, the aim of the present study was to

evaluate the most recent epidemiological, clinical, biological and

therapeutic data concerning HAV and HEV infections based on

clinical practice at ‘Sf. Parascheva’ Clinic Hospital of Infectious

Diseases (Iasi, Romania).

Patients and methods

Patients

This was a retrospective analysis of hospital-based

medical records of patients with a diagnosis of hepatitis A and

hepatitis E viral infections hospitalized between 2018 and 2019 at

‘Sf. Parascheva’ Clinic Hospital of Infectious Diseases from Iaşi.

The inclusion criteria for the study consist of in-patients with a

diagnosis of HAV and HEV infections confirmed by blood tests and

serological tests. Patients with hepatic disease (other than HAV or

HEV) were excluded from the study.

Data collection

The following data were collected: Demographic data,

medical and medication history, clinical data, blood and urine

tests, serological tests, treatment administered and outcome. All

blood and urine tests were performed by the central hospital's

laboratory. The District Public Health Directorate, Iasi, Romania,

performed the serology tests (IgM HVA and IgM HVE,

respectively).

Statistical analysis

Only cases with a complete dataset were included in

the statistical analysis. Data were analyzed by descriptive

statistics, where applicable. Correlation between demographic

parameters, clinical data and outcome was performed using Pearson

test in XLSTAT version 2019 software. Kendall's Τau correlation

coefficients were calculated (11).

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Software for

Excel (XLSTAT) version 2019.

Results

Our analysis consisted of 272 HAV- and HEV-infected

patients with complete dataset, of which 98.9% were HAV infections

and only 1.1% were HEV infection cases. There were no recorded

cases of HAV and HEV coinfection. Patients were hospitalized at

‘Sf. Parascheva’ Clinic of Infectious Diseases in Iasi between 2018

and 2019.

Patient characteristics

A wide range of age was noted for the HAV-infected

patients (between 11 months and 47 years), but as expected, most

patients were aged 8-15 years (53% cases) (Fig. 1).

Most of the patients were male (53.9% cases) with

epidemiological context of outbreaks of HAV infections from rural

areas (87.73% cases) (Table I).

| Table ICharacteristics of the HAV and HEV

patients (N=272). |

Table I

Characteristics of the HAV and HEV

patients (N=272).

| Characteristics | HAV infection | HEV infection |

|---|

| Mean age ± SD

(years) | 13.31±8.56 | 54.33±3.06 |

| Male/female

ratio | 145 (53.9%)/124

(46.1%) | 3 (100%)/0 (0%) |

| Residence area -

rural, n (%) | 236 (87.73%) | 2 (66.67%) |

| Symptomatology, n

(%) | 168 (62.45%) | 3 (100%) |

| Comorbidities, n

(%) | 12 (4.46%) | 2 (66.67%) |

Comorbidities were recorded in 12 cases (6.3%) of

HAV infections, the majority represented by digestive disorders

(41.66%, 5 cases). Hypertension (24.99%, 3 cases), chronic

peripheral venous insufficiency (8.33%, 1 case), chronic kidney

disease (8.33%, 1 case), urinary infection (8.33%, 1 case) and

oncological pathology (8.33%, 1 case) were also noted in this group

of patients (Fig. 2).

In regards to HEV infection, only 3 male patients

with a mean age of 54.3 years were identified in the hospital

database (Table I). None of the

patients had international travel history within the last 2 months,

but only one patient described previous contact with farm animals

and possible contaminated water.

Clinical findings

Regarding the onset symptomatology, most of the

HAV-infected patients (57.24%, 154 cases) had digestive

disturbances (abdominal pain, nausea) and/or jaundice (52.78%, 142

cases) at clinical examination. Flu-like onset was presented in 31

patients (11.52%), fatigue and neurasthenia in 17 patients (6.31%)

and pruritus was found in 7 patients (2.6%) (Fig. 3).

Regarding the HEV cases, the patients described a

typical onset of infection with digestive symptoms (nausea,

vomiting, abdominal pain) in 2 cases or with flu-like associated

with somnolence and asthenia in the third case.

Laboratory findings

In the HAV cases, biological investigations revealed

cholestasis in 59.65% of the cases. Based on the intensity of

cholestasis syndrome, it was found that most patients had the

moderate form of the disease, with a slight significant difference

between adults (67.19%) (Fig. 4)

and children (54.43% cases) (Fig.

5).

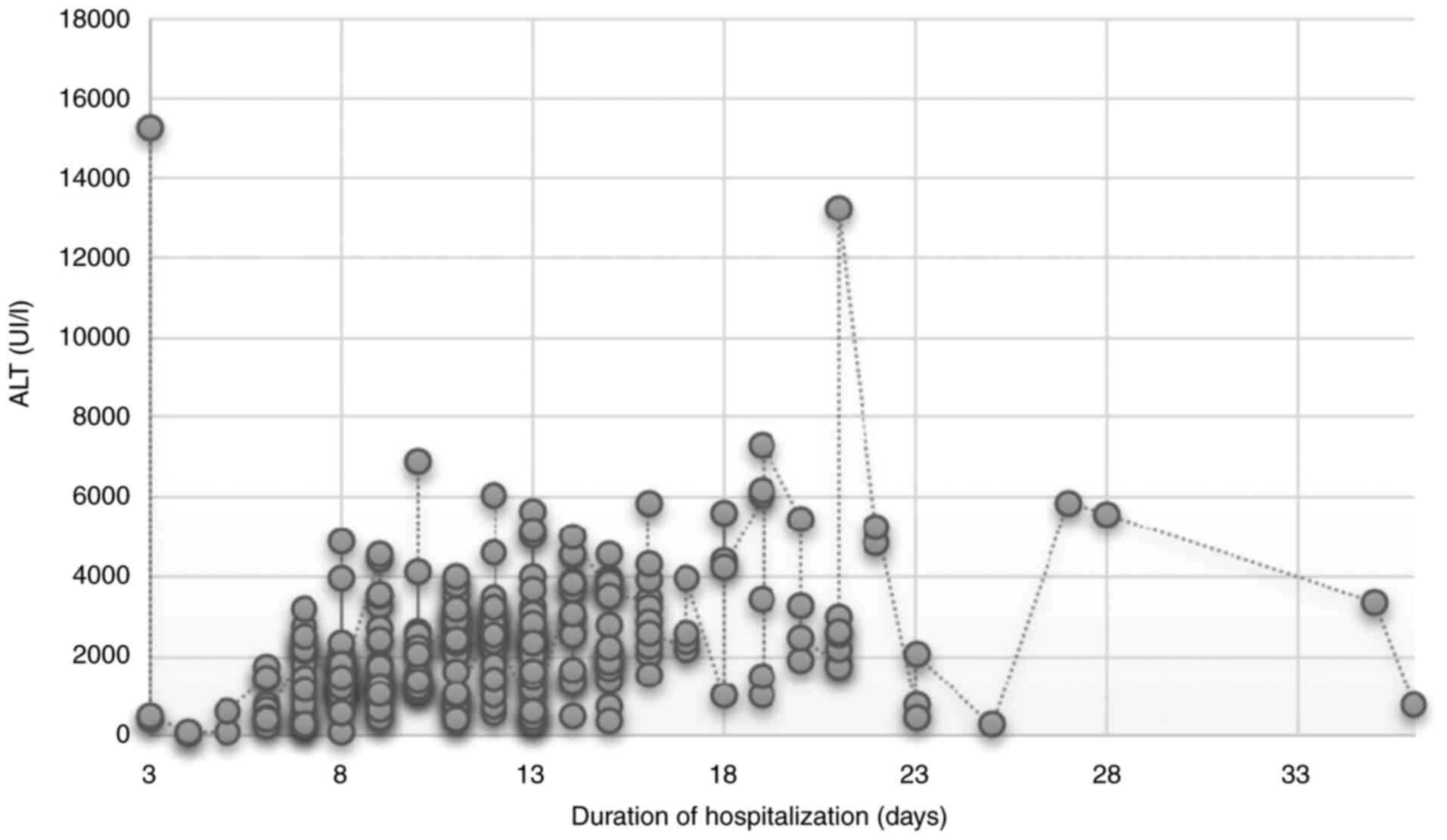

During an average hospitalization period of 12 days

(maximum period of 36 days), the evolution was favorable with a

mean decrease of 83% for alanine transaminase (ALT) and 60% for

bilirubin.

In HEV, jaundice with significant cytolysis

(transaminases increased up to 100-fold) and moderate cholestatic

syndrome were noted in all 3 cases.

HEV infection had a self-limited evolution under

hepatoprotective treatment with jaundice remission and significant

decrease in cytolysis and cholestasis in up to 16 days of

hospitalization (Fig. 6).

Extrahepatic manifestations were not identified in all 3 cases and

associated disorders (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, pre-renal

failure) were not aggravated by viral infection.

Evolution

After hospital isolation, diet, strict hygiene,

hepatoprotective treatment and isoprinosine administration (in 2.5%

of cases), over 95% of the HAV-infected patients showed a favorable

evolution, with only 5 cases of relapse in the first 3 months

post-first infection.

There was a weak association between duration of

hospitalization and age (Kendall's tau=0.198; Fig. 7) but a stronger correlation with

severity of liver dysfunction (Kendall's tau=0.297, Fig. 8).

The cases diagnosed with HEV, found in adult men,

had a favorable evolution, with a hospital stay of ~2 weeks.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, we evaluated the

epidemiological and clinical-biological evolution of patients with

HAV and HEV infections hospitalized at ‘Sf. Parascheva’ Clinic

Hospital of Infectious Diseases in Iaşi in northeastern Romania.

Only laboratory-confirmed cases with clinical criteria were

included. Of the total number of patients hospitalized in our

clinic during the analyzed period, 272 cases were included in our

study. The majority of these cases originated from rural areas with

poor sanitary conditions and/or bad hygienic habits. Moreover, in

some cases with HAV disease, a familial aggregation was noted.

Hepatitis A infection occurs worldwide, sporadically

or in an epidemic form. Globally, an estimated 1.4 million cases

occur each year (15). The US

reported an increase in the incidence of HAV by 294% during

2016-2018 compared to 2013-2015 and in 2017, more than 650 people

in the state of California were infected with hepatitis A

(including 417 hospitalizations and 21 deaths) (16).

International outbreaks have occurred via

importation of contaminated food from areas where HAV is endemic

(17). In some circumstances,

seemingly sporadic occurrences may reflect cases from

geographically distant outbreaks. In one report, for example, 213

cases of hepatitis A were detected in 23 schools in Michigan and 29

cases in 13 schools in Maine; all were related to contaminated

frozen strawberries from a common source (18).

The epidemiological characteristics of HAV disease

recorded in our study are in line with other Southeastern European

countries (19,20). Tsankova et al found in

Bulgaria recurrent outbreaks with time and geographic fluctuations.

Similar with our data, male gender and children aged less than 9

years are the main risk factors associated with spread of the

disease (20).

However, adult patients appear to be more frequently

affected in the last few years since we found 9% of cases in 2018

and ~15% of cases aged over 25 years. Even though we have noted

this increase in the age of HAV-infected patients during this

period, the incidence of this infection is uncommon in patients

over 50 years. When the serological tests for HAV infection in 3

male patients aged over 50 years were negative, we took into

consideration HEV infection.

In a recent study performed in northwestern Romania,

the mean age of HEV-infected patients was 50.6 years compared to

39.1 years for HAV infection (21).

The diagnosis was based on clinical and serological IgM anti-HEV

tests. We must mention that only three other cases were confirmed

in our clinic in the last 11 years and is not a frequent cause of

viral hepatitis in our country.

The cases of HEV previously reported, diagnosed and

treated in the infectious diseases clinic in Iași were not

numerous, but, nevertheless, recent studies conducted in our region

found a seroprevalence of 32.5% in the general population, which

indicates the fact that most cases are possibly related to zoonotic

transmission (22) similar to the

way of transmission of leptospirosis (23,24).

Other studies show a seroprevalence rate of IgG HEV antibodies up

to 17% in Romania, comparable to other east European countries

(e.g. 20.9% in Bulgaria, 15% in Serbia) (25).

In 2014, research on the evidence of HAE infection

in pigs and humans in the northeastern part of Romania showed a

seroprevalence of 17.14% (12/70) and 12.82% (10/78), in the tested

human sera. The authors also reported that HEV infections were

found in middle-aged adults exposed to the virus through contact

with pig farms (26,27).

The genotype 4 of HEV is the most frequently

detected in the European area and is involved especially in cases

of zoonotic transmission, including undercooked deer meat, wild

boar meat, pig liver sausage, and internal organs of animals

(28,29). Information regarding other possible

routes of transmission (e.g. blood transfusions, organ donors,

vertical transmission) are limited in our region (30).

The risk of infection is increased in travelers in

endemic areas (31). However, we

could not identify a clear epidemiological context for our

HEV-infected patients. Most patients with acute HEV are

asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, but severe cases were noted in

middle age male or elderly patients, especially with comorbidities.

The HEV infection is often associated with extrahepatic

manifestation, including central nervous system (CNS) disorders,

acute pancreatitis, glomerulonephritis or hematological

abnormalities (32-34)

which can also cause psychological distress and may require the

intervention of a psychologist (35,36).

In conclusion, moderate cases with only hepatic

involvement were found in our hospital. The number of cases of HEV

infection identified in our hospital was extremely low compared to

HAV infections. One reason is that an HAV infection is a nationally

notifiable infectious disease that must be reported from all

medical specialists to the District Public Health directorates,

when detected. By contrast, HEV infections remain underevaluated in

humans in our region. In the meantime, studies performed in farmed

and wild animals confirm that HEV is a ubiquitously pathogen in

swine in northeastern Romania and is a potential reservoir for

HEV-associated infection.

HEV infection is a new threat to global public

health with fatal outcome in sporadic cases. Even in light of this

fact, the evaluation within Europe is still uncertain due to

limitations in surveillance systems, differences between diagnosis

tests and lack of information.

Although the seroprevalence of HEV infection is

increasing in Romania, the use of different methods for the

diagnosis of hepatitis and the increased incidence of HEV infection

among asymptomatic patients, can allow this pathology to go

undiagnosed.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published.

Authors' contributions

IFM, SL and MCL designed the study. IFM and GEL

retrieved the data concerning the HEV infections. IMH, CM and GAL

retrieved the data concerning HAV infections. CM, IAHA and AV were

responsible for the data analyses. GEL, IFM and IMH made

substantial contributions to discussion of the data. IFM, IMH and

GAL drafted the manuscript. MCL, AV, CM and IMH critically revised

the manuscript. All authors read and give final approval of the

version to be submitted for publication.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

No ethics approval was required as the study was

performed based on medical records, retrospectively. The results of

this study do not include patient names or any personally

identifiable data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gossner CM, Severi E, Danielsson N, Hutin

Y and Coulombier D: Changing hepatitis A epidemiology in the

European union: New challenges and opportunities. Euro Surveill.

20(21101)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Pavio N, Meng XJ and Doceul V: Zoonotic

origin of hepatitis E. Curr Opin Virol. 10:34–41. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Stănculeţ N, Grigoraş A, Predescu O,

Floarea-Strat A, Luca C, Manciuc C, Dorobăţ C and Căruntu ID:

Operational scores in the diagnosis of chronic hepatitis. A

semi-quantitative assessment. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 53:81–87.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dalton HR, Pas SD, Madden RG and van der

Eijk AA: Hepatitis e virus: Current concepts and future

perspectives. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 16(399)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

World Health Organization: Hepatitis E

Fact sheet (updated July 2016). http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs280/en/.

Accessed June 20, 2019.

|

|

6

|

Luca MC, Harja-Alexa IA, Luca S,

Leonte-Enache G, Matei A and Vata A: Hepatitis E-effect on the

liver and beyond. Ro J Infect Dis. 21:172–179. 2018.

|

|

7

|

Ditah I, Ditah F, Devaki P, Ditah C,

Kamath PS and Charlton M: Current epidemiology of hepatitis E virus

infection in the United States: Low seroprevalence in the national

health and nutrition evaluation survey. Hepatology. 60:815–822.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Aspinall EJ, Couturier E, Faber M, Said B,

Ijaz S, Tavoschi L, Takkinen J and Adlhoch C: The Country Experts:

Hepatitis E virus infection in Europe. Surveillance and descriptive

epidemiology of confirmed cases, 2005 to 2015. Euro Surveill.

22(30561)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Faber M, Askar M and Stark K: Case-control

study on risk factors for acute hepatitis E in Germany, 2012 to

2014. Euro Surveill. 23:17–00469. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Mushahwar IK: Hepatitis E virus: Molecular

virology, clinical features, diagnosis, transmission, epidemiology,

and prevention. J Med Virol. 80:646–658. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gust ID: Epidemiological patterns of

hepatitis A in different parts of the world. Vaccine. 10 (Suppl

1):S56–S58. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Vâță A, Manciuc C, Dorobăț C, Vâță LG and

Luca CM: Biochemical investigations in the assessment of health

risks for over 35-year-old patients affected by environments with

hepatitis A virus. EEMJ. 17:2749–2754. 2018.

|

|

13

|

Tahaei SM, Mohebbi SR and Zali MR: Enteric

hepatitis viruses. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 5:7–15.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Istrate A and Rădulescu AL: A comparison

of hepatitis E and A in a teaching hospital in Northwestern

Romania. Acute hepatitis E-a mild disease? Med Pharm Rep. 93:30–38.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

World Health Organization. Global Alert

and Response (GAR): Hepatitis A. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/hepatitis/whocdscsredc2007/en/index4.html#estimated.

Accessed April 22, 2020.

|

|

16

|

California Department of Public Health.

Hepatitis A. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/Immunization/Hepatitis-A.aspx.

Accessed April 22, 2020.

|

|

17

|

Wheeler C, Vogt TM, Armstrong GL, Vaughan

G, Weltman A, Nainan OV, Dato V, Xia G, Waller K, Amon J, et al: An

outbreak of hepatitis A associated with green onions. N Engl J Med.

353:890–897. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hutin YJ, Pool V, Cramer EH, Nainan OV,

Weth J, Williams IT, Goldstein ST, Gensheimer KF, Bell BP, Shapiro

CN, et al: A multistate, foodborne outbreak of hepatitis A.

National hepatitis a investigation team. N Engl J Med. 340:595–602.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mrzljak A, Dinjar-Kujundzic P, Jemersic L,

Prpic J, Barbic L, Savic V, Stevanovic V and Vilibic-Cavlek T:

Epidemiology of hepatitis E in South-East Europe in the ‘one

health’ concept. World J Gastroenterol. 25:3168–3182.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Tsankova GS, Todorova TT, Ermenlieva NM,

Popova TK and Tsankova DT: Epidemiological study of hepatitis a

infection in Eastern Bulgaria. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 59:63–69.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Teshale EH, Hu DJ and Holmberg SD: The two

faces of hepatitis E virus. Clin Infect Dis. 51:328–334.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Riveiro-Barciela M, Minguez B, Girones R,

Rodriguez-Frias F, Quer J and Buti M: Phylogenetic demonstration of

hepatitis E infection transmitted by pork meat ingestion. J Clin

Gastroenterol. 49:165–168. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Manciuc DC, Iordan IF, Adavidoaiei AM and

Largu MA: Risks of leptospirosis linked to living and working

environments. EEMJ. 17:749–753. 2018.

|

|

24

|

Manciuc C, Dorobăţ C, Hurmuzache M and

Nicu M: Leptospirosis: Clinical and environmental aspects of the

Iaşi County. EEMJ. 6:133–136. 2007.

|

|

25

|

Guerra JAAA, Kampa KC, Morsoletto DGB,

Junior AP and Ivantes CAP: Hepatitis E: A literature review. J Clin

Transl Hepatol. 5(376)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kamar N, Bendall R, Legrand-Abravanel F,

Xia NS, Ijaz S, Izopet J and Dalton HR: Hepatitis E. Lancet.

379:2477–2488. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Aniţă A, Gorgan L, Aniţă D, Oşlobanu L,

Pavio N and Savuţa G: Evidence of hepatitis E infection in swine

and humans in the East Region of Romania. Int J Infect Dis.

29:232–237. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Murrison LB and Sherman KE: The enigma of

hepatitis E virus. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 13:484–491.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Li TC, Chijiwa K, Sera N, Ishibashi T,

Etoh Y, Shinohara Y, Kurata Y, Ishida M, Sakamoto S, Takeda N and

Miyamura T: Hepatitis E virus transmission from wild boar meat.

Emerg Infect Dis. 11:1958–1960. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Teshale EH and Hu DJ: Hepatitis E:

Epidemiology and prevention. World J Hepatol. 3:285–291.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Khuroo MS, Kamili S and Jameel S: Vertical

transmission of hepatitis E virus. Lancet. 345:1025–1026.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Hewitt PE, Ijaz S, Brailsford SR, Brett R,

Dicks S, Haywood B, Kennedy IT, Kitchen A, Patel P, Poh J, et al:

Hepatitis E virus in blood components: A prevalence and

transmission study in southeast England. Lancet. 384:1766–1773.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kim JH, Nelson KE, Panzner U, Kasture Y,

Labrique AB and Wierzba TF: A systematic review of the epidemiology

of hepatitis E virus in Africa. BMC Infect Dis.

14(308)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Colson P, Borentain P, Queyriaux B, Kaba

M, Moal V, Gallian P, Heyries L, Raoult D and Gerolami R: Pig liver

sausage as a source of hepatitis E virus transmission to humans. J

Infect Dis. 202:825–834. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Manciuc C and Largu A: Impact and risk of

institutionalized environments on the psyho-emotional development

of the HIV-positive youth. Environ Eng Manag J. 13:3123–3129.

2014.

|

|

36

|

Manciuc C, Filip-Ciubotaru F, Badescu A,

Duceag LD and Largu AM: The patient-doctor-psychologist triangle in

a case of severe imunosupression in the HIV infection. Rev Med Chir

Soc Med Nat Iasi. 120:119–123. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|