Introduction

The development of the lens in the eye begins with

the PAX6-expressing epidermal ectoderm making contact with the

optic vesicle. Subsequently, SOX2 is expressed in the ectoderm

region in contact with the optic vesicle, and the coordinated

action of PAX6 as a partner factor for SOX2 causes cells in contact

with the optic vesicle to thicken and form lens placodes, which are

depressed inward by the formation of the optic cup (1). The lens placode is eventually

separates from the epidermal ectoderm to form a spherical lens

vesicle with an array of surrounding cells. Moreover, the cells

that are positioned on the side of the lens follicle extend toward

the interior of the lens placode and fill the interior (2,3).

The human lens is 9-10 mm in diameter and is

surrounded by a lens capsule, which is rich in type IV collagen. On

the corneal side, the lens epithelium is composed of a single layer

of lens epithelial cells (LECs). Around the equatorial region of

the lens, LECs separate from the capsule and begin to elongate

toward the anterior and posterior poles of the lens, where the LECs

differentiate into lens fiber cells (LFCs). Eventually, the

organelles inside the LFCs disappear (4) and are replaced by lens fibers filled

with crystallin proteins. At the center of the lens lies the lens

nucleus (fetal nucleus), which is formed during development and is

surrounded by lens fibers (5).

After birth, LECs continue to proliferate slowly, and the few

remaining lens-tissue stem cells expressing p75NTR are suspected to

be involved in proliferation (6).

However, the proliferation of these cells slows with age (7).

The lens is composed of approximately 90%

crystallin, a water-soluble protein. Crystallin in vertebrates is

mainly classified into α-, β-, and γ-crystallin. α-crystallin has 2

subunits of αA- and αB-, β-crystallin has 7 subunits of βA1-βA4 and

βB1-βB3, and γ-crystallin has 5 subunits of γA-γD and γS (8). In the lens, α-crystallin is a 40-mer,

β-crystallin is a 2-6-mer, and γ-crystallin is a monomer, which

play an important role in interacting with each other to maintain

the transparency of the lens (9).

α-crystallin is a major component of the lens, accounts for

approximately 30% of the water-soluble protein in the lens, and

functions as a molecular chaperone that suppresses aggregation of

other crystallin species (10). In

humans, αB-crystallin is expressed in tissues other than the eye,

whereas αA-crystallin is expressed only in the lens (11). βB2-crystallin is the main component

of β-crystallin. It has been reported that in βB2-crystallin

obtained from the lens of senile cataract, the Asp residue at the

C-terminal site undergoes significant site-specific isomerization,

which occurs at the site of interaction with βB2-crystallin itself

and other βB-crystallins, and it may contribute to the formation of

senile cataract by affecting the crystallin subunit-subunit

interaction and inducing abnormal crystallin aggregation (12).

After the lens of a newt is removed, the pigmented

epithelial cells (PECs) located on the dorsal side of the iris

first start to dedifferentiate, a process during which their

pigment is degranulated, and then differentiate into LECs to

regenerate a new lens (13,14).

By contrast, regeneration of the lens in mammals does not occur

once the lens capsule is removed (15). Intriguingly, if only the contents

of the lens are removed and the lens capsule and LECs are

preserved, the lens reproduces the same process as that occurring

during embryonic development and forms a regenerated lens (16-18).

However, the regenerated LECs exhibit aberrant, morphological

changes, including irregular cell arrangement, mitochondrial

degeneration, and vacuoles in the cytoplasm (19).

Induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, first

described by Takahashi et al (20), are pluripotent cells that can

differentiate into diverse cell types. Notably, iPS cells have also

been reported to differentiate into LECs (21-24),

but no study thus far has reported their formation of

three-dimensional cell aggregates. Here, we investigated the

formation of three-dimensional cellular aggregates expressing

lens-specific proteins using human iris-derived tissue cells and

iPS cells.

Materials and methods

Preparation of human iris tissue

specimens

The tissues examined in the study were collected

from patients with glaucoma during treatment with partial iris

resection, and pieces of the collected human iris tissue were fixed

in SUPER FIX™ rapid fixative solution (cat. no. KY-500;

Kurabo Industries Ltd.) (6).

Subsequently, paraffin sections were prepared from the fixed

tissues by following standard procedures, and the sections were

stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Iris samples were

collected from patients who underwent partial iris resection as a

treatment for glaucoma at the Department of Ophthalmology, Fujita

Health University Hospital, between April 2015 and March 2017, and

who consented to the study. The mean age of the patients was

58.9±5.4 years, 4 males and 7 females. Patients with ocular

diseases other than glaucoma were excluded from the study. This

study was performed with the approval (approval no. 05-065) of the

Ethics Review Committee of Fujita Health University. The experiment

was carried out with the approval (approval no. DP16055) of the

Recombinant DNA Experiment Committee of Fujita Health University.

All study participants provided written informed consent for their

tissue to be used, and the study complied with the tenets of the

Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human tissues.

Isolation and culture of cells from

human iris tissue

Human iris tissue was processed as described

(25,26). Briefly, iris tissue was treated

with 0.2% collagenase (cat. no. C9722-50MG; Merck KGaA) and washed

twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; cat. no. D8662-500ML;

Merck KGaA), and the isolated human iris tissue-derived cells

(H-iris cells) were cultured in iris culture medium (iris medium):

Advanced Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12 (Advanced

DMEM/F12; cat. no. 12634010; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.)

supplemented with 5% (w/v) mixed serum [heat-inactivated human

serum (cat. no. H3667-20ML; Merck KGaA), KnockOut™ Serum

Replacement (KSR; cat. no. 10828010; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and

Artificial Serum, Xeno-free (cat. no. A2G10P2CC; Cell Science &

Technology Institute, Inc.) in a 5:3:2 ratio], 10 ng/ml basic

fibroblastic growth factor (b-FGF; cat. no. F0291; Merck KGaA), 10

ng/ml epidermal growth factor (cat. no. E9644; Merck KGaA), 1%

(w/v) GlutaMAX™ (cat. no. 35050061; Thermo Fisher

Scientific), 0.1% (w/v) CultureSure® Y-27632 solution

(used only when starting the culture; cat. no. 039-24591; FUJIFILM

Wako Pure Chemical Corporation), and 1% (w/v)

penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. P4458-100ML; Merck KGaA). The

cells were plated in culture dishes coated with type I collagen

(cat. no. TMTCC-050; Toyobo Co., Ltd.) and incubated at 37˚C in a

5% CO2 humidified incubator, and the cultured cells were

examined using an inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a

digital camera system (Power IX-71 and DP-71; Olympus

Corporation).

Preparation of human iris-derived iPS

cells

Human iris-derived iPS (H-iris iPS) cells were

prepared through cell reprogramming using H-iris cells, as

described previously (26).

Briefly, H-iris cells were reprogrammed by employing a

micro-electroporation method performed using an Epi5™

Episomal iPSC Reprogramming Kit (cat. no. A15960; Thermo Fisher

Scientific) (27). After cloning,

StemFit® (cat. no. RCAK02N; ReproCELL Inc.) mixed with

0.1% (w/v) CultureSure® Y-27632 solution (only at the

beginning of culture) was used as the iPS cell-culture medium, and

iMatrix-511 (Laminin-5; cat. no. 892011; Takara Bio Inc.) was used

as the coating agent (STEP-0 culture condition; Fig. 1). During passaging, the H-iris iPS

cells were detached using a mixture of Accutase (cat. no.

AT104-100ML; M&S TechnoSystems, Inc.) and TrypLE Select Enzyme

(cat. no. 12563011; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The H-iris cells and

H-iris iPS cells were confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma

infection using a mycoplasma detection kit (EZ-PCR™

Mycoplasma Test Kit, cat. no. 20-700-20; Biological Industries USA

Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The experiment

was conducted with the approval (no. DP16055) of the Recombinant

DNA Experiment Committee of Fujita Medical University.

Differentiation of H-iris cells and

H-iris iPS cells into LECs

The composition of the used LEC medium (with the

STEP-4 culture condition being the same; Fig. 1), which induces H-iris cells to

differentiate into LECs, was as follows (28): 10% (w/v) fetal bovine serum (cat.

no. 04-111-1A; Biological Industries Israel Beit-Haemek), 10 ng/ml

b-FGF, 1% (w/v) minimum essential medium non-essential amino acids

(cat. no. 11140050; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5% (w/v)

GlutaMAX™, DMEM high-glucose medium (cat. no. 11965092;

Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1% (w/v) penicillin/streptomycin

solution.

The common differentiation culture conditions were

based on reports describing the differentiation of human embryonic

stem (ES) cells into lens progenitor cells and lentoid bodies

(29); H-iris iPS cells were

cultured in Lens differentiation base medium: Advanced DMEM/F12

supplemented with 0.05% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (cat. no.

012-23881; FUJIFILM Wako), 1% (w/v) non-essential amino acids

(Thermo Fisher Scientific), 0.5% (w/v) GlutaMAX™, 0.5%

(w/v) N-2 MAX Media Supplement (cat. no. 17502048; Thermo Fisher

Scientific), 1% (w/v) B-27 supplement (cat. no. 17504044; Thermo

Fisher Scientific), 100 ng/ml b-FGF, and 0.1% (w/v)

CultureSure® Y-27632 solution, with 100 ng/ml Noggin

(cat. no. 6057-NG; R&D Systems, Inc.) added for 6 days

(STEP-1). On the 6th day, the medium was replaced with lens

differentiation base medium containing 20 ng/ml bone morphogenetic

protein-4/7 (cat. no. 3727-BP; R&D Systems) and 100 ng/ml b-FGF

(STEP-2), and on the 18th day, this medium was replaced with lens

differentiation base medium containing 20 ng/ml Wnt-3a (cat. no.

5036-WN; R&D Systems) and 100 ng/ml b-FGF (STEP-3).

Distinct culture environments were used in our

experiments, Experiments 1-5 (Ex.1-Ex.5), as described below

(summarized in Fig. 1): Ex.1:

1x105 H-iris iPS cells were seeded into 3.5 cm adhesive

cell-culture dishes coated with iMatrix-511 and cultured in iPS

culture medium at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator,

and starting from the next day, the cells were maintained as

adherent cultures sequentially under STEP-1, STEP-2, and STEP-3

culture conditions. Ex.2: 1x105 H-iris iPS cells were

seeded into 3.5 cm adhesive cell-culture dishes coated with

iMatrix-511 and cultured in iPS culture medium at 37˚C in a 5%

CO2 humidified incubator, and from the next day, the

cells were maintained as adherent cultures sequentially under

STEP-1, STEP-2, and STEP-3 culture conditions. Under STEP-3

conditions applied for the last 10 days, the cells were detached

using a mixture of Accutase and TrypLE Select Enzyme and cultured

using the inclined rotational-suspension method in a centrifuge

tube. Ex.3: 1x106 H-iris iPS cells were cultured

sequentially under the culture conditions of STEP-1 using the

static-suspension method, STEP-2 using the inclined

rotational-suspension method, and STEP-3 using the horizontal

rotational-suspension method in a centrifuge tube. Ex.4:

1x106 H-iris iPS cells were cultured in a centrifuge

tube under STEP-1, STEP-2, and STEP-3 culture conditions

sequentially using the static-suspension method and then using the

inclined rotational-suspension method under STEP-4 conditions for 2

weeks. Ex.5 is described in the next subsection. The medium was

changed every 2 days in Ex.1-Ex.5. For inclined rotation in the

experiments, an NRC20D rotary mixer (Nissinrika Co., Ltd., Tokyo,

Japan) was used at 3 rpm and a tilt angle of 45˚, and for

horizontal rotation, an RT-50 rotator (TAITEC Corporation) was used

at 35 rpm.

Differentiation of multiple ocular

cells

As reported by Hayashi et al (30), H-iris iPS cells were cultured using

the self-formed ectodermal autonomous multi-zone (SEAM) method for

ocular cells (Ex.5). Briefly, H-iris iPS cells were seeded into

iMatrix-511-coated cell-culture dishes at 350 cells/cm2

using the StemFit® medium, and at 4 weeks after seeding,

the culture medium (SEAM medium) was changed to the following

differentiation medium: DMEM (cat. no. D5796-500ML; Merck KGaA)

supplemented with 10% (w/v) KSR, 1% (w/v) sodium pyruvate (cat. no.

11360070; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% (w/v) non-essential amino

acids, 1% (w/v) GlutaMAX™, 1% (w/v) monothioglycerol

(cat. no. 195-15791; FUJIFILM Wako), and 1% (w/v)

penicillin/streptomycin; the cells were cultured at 37˚C in a 5%

CO2 humidified incubator. The cells present in the area

where LECs were observed using the SEAM method were harvested and

cultured using the rotational-suspension method. After 4 weeks, the

cell aggregates that formed between the 2nd and 3rd zones of the

SEAM were picked using a pipette, cloned, and cultured in LEC

medium, and then 1x106 proliferated cells were cultured

under the same conditions as in Ex.3 and differentiated into

LECs.

Reverse transcription and quantitative

PCR (qPCR)

Total cellular RNA was extracted using a

TaqMan® Gene Expression Cells-to-CT™ Kit

(cat. no. A25603; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and RNA concentrations

were measured using a spectrophotometer (NanoVue™; GE

Healthcare) (31). Total RNA was

reverse-transcribed using a GeneAmp® PCR System 9700

Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to synthesize cDNA, and,

subsequently, qPCR was performed using an ABI PRISM®

7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and

the following primers and probes (TaqMan® Gene

Expression assays; cat. no. 4331182; Thermo Fisher Scientific):

p75NTR (assay ID. Hs00609976_m1), SOX2 (assay ID.

Hs00415716_m1), PAX6 (assay ID. Hs01088114_m1), type IV

collagen (assay ID. Hs00266237_m1), and the crystalline

lens-marker gene αA-crystallin (assay ID. Hs00166138_m1);

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; assay ID.

Hs99999905_m1) was used as an internal positive control. The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: reverse transcription: 60

min at 37˚C and 5 min at 95˚C. qPCR: 2 min at 50˚C, 10 min at 95˚C,

15 sec at 95˚C and 1 min at 60˚C, for 50 cycles. Relative

expression was analyzed by the delta-delta Ct method using Ct

values obtained from qPCR amplification.

Sectioned specimens of cell

aggregates

Cell aggregates were collected from suspension

cultures and treated using the cell-block method (32) to prepare paraffin-section specimens

using a fixative solution as described previously.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as

previously described (26,33). Briefly, fixed cells were

permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (cat. no. 04605-250; FUJIFILM

Wako), blocked with a serum-free ready-to-use blocking reagent

(cat. no. X090930-2; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) for 5 min at room

temperature, and stained with one of the following primary

antibodies (incubated for 1 h at 37˚C): anti-human αA-crystallin

rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:100; cat. no. ab5595; Abcam plc.),

anti-human PAX6 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:100; cat. no.

14-9914-80; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-human SOX2 rat

monoclonal antibody (1:100; cat. no. 14-9811-82; Thermo Fisher

Scientific), anti-human type IV collagen rabbit polyclonal antibody

(1:200; cat. no. LB-0445; Life Science Laboratories, Inc.),

anti-p75NTR rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:200; cat. no. ANT-007;

Alomone Labs), and anti-human βB2-crystallin rabbit polyclonal

antibody (1:100; cat. no. ab252971; Abcam). Next, the cells were

incubated with an appropriate secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor

594-labeled anti-mouse IgG donkey antibody (1:500; cat. no.

A-21203; Thermo Fisher Scientific), Alexa Fluor 594-labeled

anti-rabbit IgG goat antibody (1:500; cat. no. A-11037; Thermo

Fisher Scientific), or Alexa Fluor 594-labeled anti-rat IgG goat

antibody (1:500; cat. no. A-11007; Thermo Fisher Scientific), for 1

h at 37˚C. DAPI (VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with DAPI; cat. no.

H-1200; Vector Laboratories) was used for nuclear staining. The

immunostaining was evaluated using a fluorescence microscope (Power

BX-51; Olympus).

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate and

repeated at least thrice. Data are presented as means ± standard

deviation (SD) and were analyzed using repeated measures analysis

of variance with Tukey's post hoc test. Statistical Package for

Social Science (SPSS) Statistics 24 (IBM Corporation) was used for

statistical analyses.

Results

Primary culture and differentiation of

H-iris cells

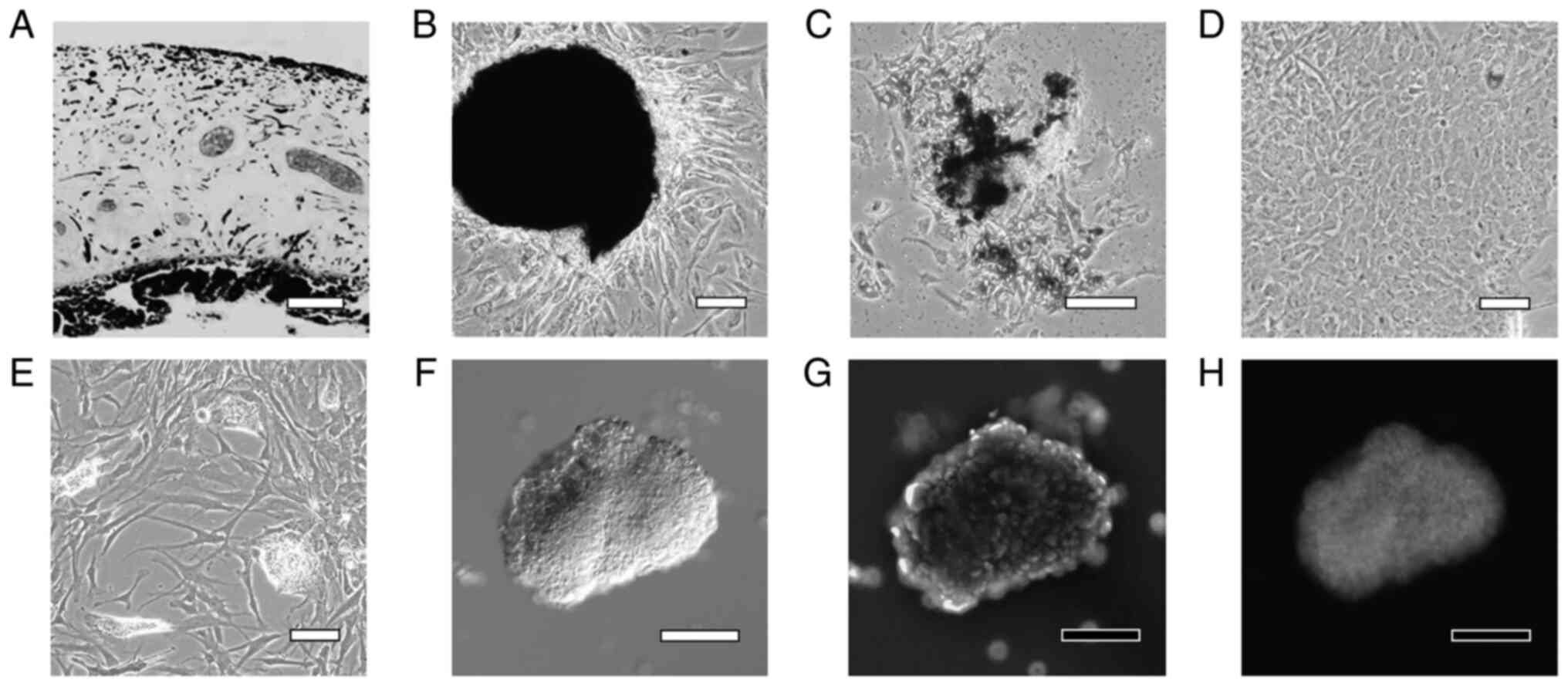

Human iris tissue was enzymatically treated and

decomposed into small pieces (Fig.

2A). Cells proliferated from the tissue pieces that adhered to

dishes (Fig. 2B), and while some

of these cells contained a pigment in the cytoplasm, the pigment

was degranulated in several cells (Fig. 2C). On Day 7 of culture, the cells

became confluent and the cultures included very few pigmented cells

(Fig. 2D). After culturing in

STEP-4 medium for 3 weeks, the cultures contained small cell masses

(lentoid body-like masses) in which the cells were partially

aggregated (Fig. 2E). When the

small cell aggregates were collected using a pipette and

immunostained with an αA-crystallin antibody, numerous brightly

stained cells were observed (Fig.

2F-H).

Differentiation using the Ex.1

method

When iPS cells cultured in iPS medium (Fig. 3A) were cultured in STEP-1 medium

for 6 days, cells featuring short protrusions were observed

(Fig. 3B). After 12 days in STEP-2

medium, the cells were fully confluent and partially multilayered

(Fig. 3C), and after 17 days in

STEP-3 medium, the cells were further multilayered (Fig. 3D). On the last day of culture of

each step from STEP-0 to STEP-3, the cells were collected and total

RNA was extracted and reverse-transcribed to produce cDNA for PCR

analyses; our results showed that p75NTR mRNA expression

levels were significantly higher at STEP-1, -2, and -3 than at

STEP-0 (Fig. 3E). Moreover, at

STEP-3, the cultures included a few αA-crystallin-positive cell

populations, and the αA-crystallin-positive cells were negative for

SOX2 (Fig. 3F-I).

The expression of PAX6, SOX2, and αA-crystallin

proteins at each step was confirmed through immunostaining

performed under identical conditions. The expression of

αA-crystallin was strongest at STEP-3, but the expression was not

uniform, with certain cells expressing the protein more strongly

than others, and the expression tended to be stronger in aggregated

cells than in non-aggregated cells (Fig. 4). Fig.

4 examines the changes in protein expression of PAX6, SOX2, and

αA-crystallin during lens development in vivo at different

culture steps. Since iPS cells were used in this study, SOX2, one

of the markers of iPS cells, is strongly expressed in STEP-0.

However, by starting the induction of differentiation to lens, the

expression of SOX2 decreased once in STEP-1, but as the

differentiation STEP to lens progressed, the expression of SOX2

became strong again. On the other hand, PAX6 was slightly expressed

in STEP-1. In addition, αA-crystallin, a marker of lens protein,

was hardly detected until STEP-2, but was strongly detected in

STEP-3, indicating that the cells differentiated into lens

epithelial cells.

Differentiation using the Ex.2

method

The Ex.2 method was the same as the Ex.1 method

until the end of STEP-2, but in STEP-3, starting from 7 days after

initiation of the culture, the cells were cultured on a rotary

culture device (Fig. 5A). After 10

days of this rotational suspension culture, opaque cell aggregates

were formed (Fig. 5B). Sections of

the cell aggregates were prepared using the cell-block method, and

H&E staining revealed that the aggregates were surrounded by

one or two layers of cells, with the aggregate interior being

filled with cells distinct from the cells around the aggregates

(Fig. 5C). Moreover, the cells

forming the aggregates showed cytoplasmic staining for

αA-crystallin (Fig. 5D and

E). An illustration of the

developmental process of the lens is presented in Fig. 5F. Initially, a lens follicle

featuring a hollow center is formed, and then the interior of the

follicle is filled with cells extending from one direction on the

optic cup side.

Differentiation by the Ex.3

method

In the Ex.3 method, cell aggregates were formed

starting from the STEP-1 stage, with differentiation occurring in

the cell aggregates, and several days after the start of culture in

STEP-3, numerous sac-like structures were observed around the cell

aggregates (Fig. 6A and B). The sac-like structures were

translucent (Fig. 6C), and H&E

staining of cell-block sections revealed that these structures were

formed by two layers of cell membranes, with the inner layer being

hollow (Fig. 6D). The two cell

layers showed identical staining for αA-crystallin (Fig. 6E), although the outer cells showed

stronger type IV collagen staining than did the inner cells

(Fig. 6F). Conversely, in H&E

staining of the cell aggregates, we observed that these structures

were formed by two layers of cells, and cells whose nuclei were

larger and cytoplasm was darkly stained with eosin were observed

compared to the sac-like structures (Fig. 6G). The cells whose cytoplasm was

darkly stained with eosin were also strongly positive for

αA-crystallin (Fig. 6H) and type

IV collagen (Fig. 6I) in both the

inner and outer layers of the two-layer structure.

Differentiation using the Ex.4

method

In the Ex.4 method, cells were cultured using the

static-suspension method to allow the formation of cell-cell

junctions for differentiation. Subsequently, a step involving

rotational suspension culture, STEP-4, was included for an

additional 2 weeks. Expression analysis of five genes revealed that

the expression levels in STEP-3 and STEP-4 were significantly

higher than the changes between STEP-0 and STEP-1 and STEP-2

(Fig. 7A-E). The expression levels

of p75NTR and type IV collagen were significantly higher in

STEP-3 than in STEP-0, with the expression levels of the two genes

decreasing in STEP-1 as compared to the level in STEP-0 but

increasing thereafter. The expression levels of SOX2 and

PAX6 increased during ocular differentiation, and in the

Ex.4 method, the expression levels of these genes were

significantly increased in STEP-3 and STEP-4.

Visual examination of cell aggregates obtained at

the end of culture (Fig. 8A)

revealed that the aggregates were milky-white and opaque, although

the opacity was lighter in certain areas than in others. The

results of H&E staining of sectioned specimens further showed

that vacuoles formed inside the cell aggregates (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the surface of the

cell aggregates was stratified, as illustrated in Fig. 8C showing an enlarged view of Area 1

from Fig. 8B, and these cells were

positive for SOX2 (Fig. 8D),

p75NTR (Fig. 8E), αA-crystallin

(Fig. 8F), and type IV collagen

(Fig. 8G). Conversely, in the

region that is marked as Area 2 in Fig. 8B and enlarged in Fig. 8H, the cells on the surface of the

aggregates transitioned from multilayers to monolayers, and the

monolayers were negative for SOX2 (Fig. 8I); furthermore, in this region,

p75NTR expression was decreased (Fig.

8J), and αA-crystallin staining was not detected (Fig. 8F), but positive staining for type

IV collagen was observed (Fig.

8G).

Differentiation using the Ex.5 (SEAM)

method

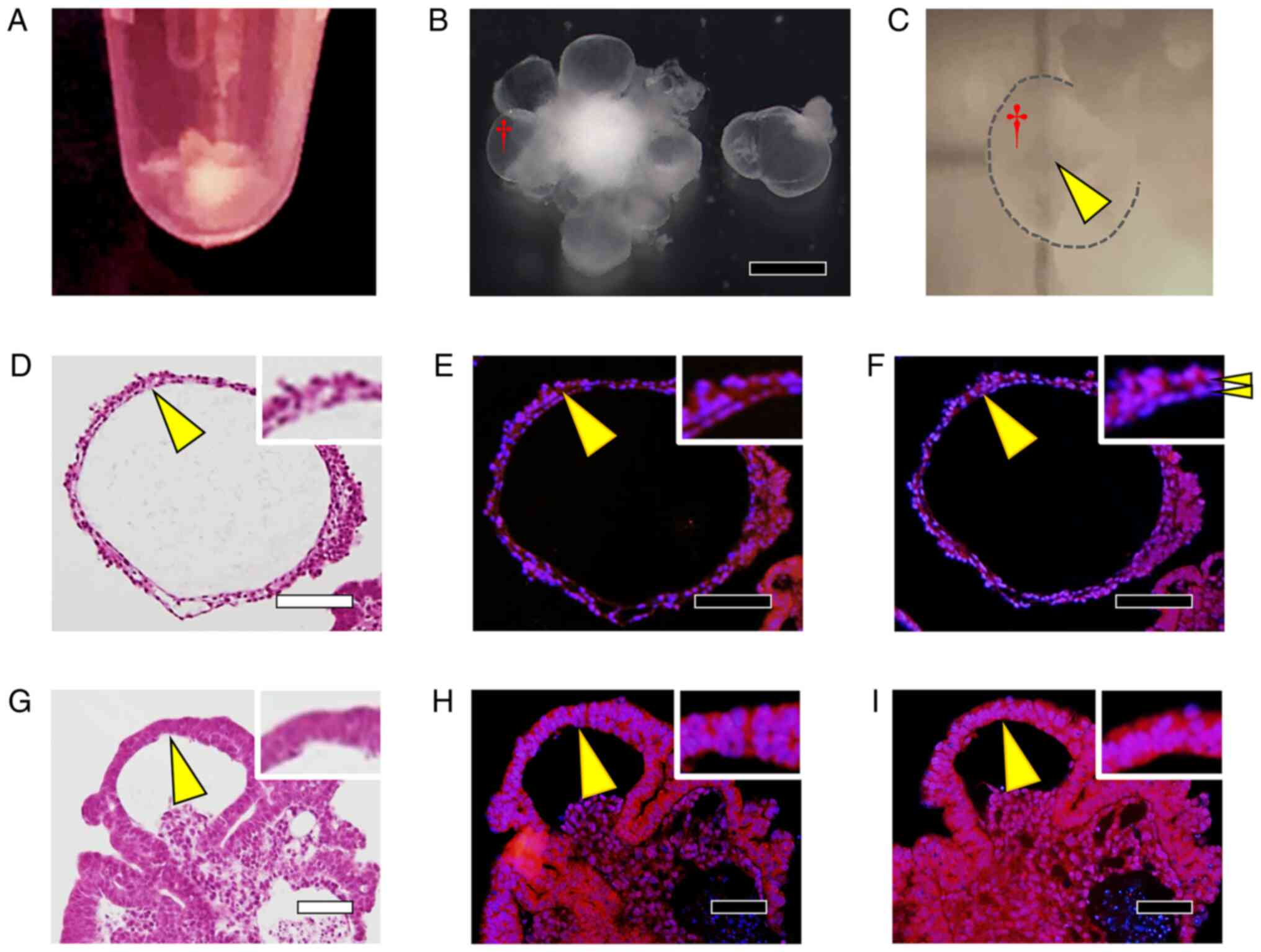

H-iris iPS cells (Fig.

9A) were cultured continuously for 4 weeks in a differentiation

medium of the same composition. At the end of culture, small cell

aggregates were observed at the boundary between the 2nd and 3rd

zones (Fig. 9B), and these

aggregates were positive for αA-crystallin (Fig. 9C). The cell aggregates were

carefully harvested using a pipette and cultured using the static-

and rotational-suspension methods. H&E staining of sections of

the cell aggregates revealed that the cells were arranged in

concentric circles, and in the cells in the interior of the

aggregates, the cytoplasm was uniformly stained with eosin

(Fig. 9D). αA-crystallin staining

was detected in the cells surrounding the aggregates and in the

inner cells whose cytoplasm was stained with eosin (Fig. 9E), and βB2-crystallin staining was

slightly stronger in the inner cells than in the cells around the

aggregates (Fig. 9F). Moreover,

the cells around and inside the cell aggregates were positive for

type IV collagen, and the inner cells whose cytoplasm was uniformly

stained with eosin also particularly stained strongly for type IV

collagen (Fig. 9G).

Discussion

In this study, we cultured human iris-derived tissue

cells and iPS cells using various culture methods and generated

three-dimensional cell aggregates expressing αA-crystallin, a

lens-specific protein.

The history of research on lens regeneration began

with lens regeneration in newts, which was discovered in the 1890s

(34,35). In newts, when the lens is removed,

the pigment in the iris degranulates and then the iris tissue

regenerates the lens. Lens regeneration in newts is unique, with

the lens being unfailingly regenerated from the dorsal iris.

Studies conducted using transgenic newts have shown that b-FGF and

Wnt play a major role in the regeneration of the lens, refuting the

notion that tissue stem cells exist only in the dorsal iris

(36), and lens regeneration has

also been shown to occur several times during the lifetime of a

newt (13,37). However, no study to date has

reported lens regeneration from the iris in mammals. We have been

conducting research in the field of regenerative medicine with a

focus on iris tissue (38-41).

Here, we found that lentoid body-like cell aggregates expressing a

very small but lens-specific protein were formed in cultures of

cells derived from human iris tissue. We previously reported that

cultured H-iris cells included cells positive for tissue stem cell

markers (CD271 and p75NTR) (26),

and p75NTR is also a tissue stem cell marker in the lens (42). Our method of culturing iris tissue

can also be used to culture certain cells that are positive for

tissue stem cell markers, and this is the first report of PECs in

human iris tissue degranulating and differentiating into small cell

aggregates (lentoid body-like cell masses) expressing

αA-crystallin, a marker for LECs.

First, we cultured H-iris iPS cells to induce their

differentiation into lens epithelial progenitor cells based on a

report that ES cells can differentiate into these progenitor cells

(29). As compared to the iPS

cells at STEP-0, the progressively differentiating cells showed

increasing mRNA expression of p75NTR, a marker of lens

epithelial stem cells. Moreover, PAX6 protein expression increased

during STEP-1, the stage at which p75NTR mRNA expression

started to increase, whereas SOX2 protein expression decreased once

during STEP-1 and increased again during STEP-3. The association

between PAX6 and SOX2 is critical because the two

have been reported to act in conjunction to activate the expression

of δ-crystallin and induce the development of lens placodes

(1). Cells expressing

αA-crystallin protein were observed during STEP-3, where

crystallin-positive cells were aggregated and not all cells

expressed αA-crystallin. Cell-cell interactions could play a

crucial role in lens differentiation by inducing the formation of

cell aggregates.

The maturation of cartilage cells has been reported

to be promoted by the application of a mechanical stimulation or

load to cells, and cellular aggregates generated using rotational

culture have been proposed to represent an essential component for

creating artificial cartilage through tissue engineering (43-47).

Here, from the middle of STEP-3, when rotational suspension culture

was performed as a mechanical stimulus (Ex.2), the cell aggregates

formed were surrounded by one or two layers of cells, and cells

elongating inward from certain directions were observed to fill the

interior of the aggregates. Our finding is similar to the observed

proliferation and migration of cells during lens formation during

development, and these cells expressed αA-crystallin. However, the

cell aggregates grew to <1 mm as the largest size.

Considering the aforementioned results, we next

cultured cells by employing the cell aggregates from STEP-1 and

subjecting them to tilt rotation and horizontal rotation (Ex.3).

Translucent sac-like structures formed by two layers of cell

membranes were observed. In the sac-like structures, type IV

collagen was strongly expressed outside the bilayer, mimicking the

type IV collagen-rich lens capsule present on the outer surface of

the lens (48-50).

However, because the process of development and growth of the lens

capsule remains unclear, embryological and cell-based studies on

the lens capsule are required.

As the next method, STEP-4 using LEC medium was

performed (Ex.4). All measured gene expression increased during

STEP-3 and further increased in STEP-4. The cell aggregates grew to

~2 mm in size, with the surrounding cells, including LECs, arranged

in the same manner as in the lens in certain areas, and a few

vacuolated areas were present in the interior.

Lastly, in Ex.5, the areas where LECs formed in

differentiated SEAM were collected and cultured. The SEAM method is

a two-dimensional adhesion-culture method, and the concentric SEAMs

formed by cells differentiating on their own through cell-cell

interaction without changing the medium conditions mimic the

development of the whole eye: the location of cells in different

zones shows lineages spanning the superficial ectoderm, lens,

neural retina, and retinal pigment epithelium of the eye. When

cells in the areas where superficial ectoderm differentiate under

the SEAM method are collected and further differentiated using the

air-lift method, a three-dimensional cell sheet expressing proteins

characteristic of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium is formed

(23,30,51).

Therefore, in the case of cells differentiated according to the

SEAM regions, differentiation is induced in a manner that is highly

distinct from the differentiation triggered previously in iPS cells

using other methods. A relatively uniform interior was detected in

the cell aggregates generated by collecting αA-crystallin-positive

cells formed using the SEAM method and then culturing them using

static- and rotational-suspension methods, and βB2-crystallin and

type IV collagen positivity was also detected. However, no lens

capsule was observed in these cell aggregates. It could be

challenging to completely control the directionality of cell

arrangement in cell aggregates without a lens capsule being present

as a basement membrane.

The lens nucleus is located at the center of the

lens, where organelles are lost during development. A recent study

on organelle degradation inside the lens reported that organelle

degradation by phospholipases of the PLAAT family leads to the

achievement of optimal transparency and refractive function of the

lens (4). Organelles affect light

scattering, and in a flow cytometer, a widely used research

instrument, the measurement is based on the principle that

laterally scattered light is affected by the size of the cell

nucleus and the presence of cell membranes and organelles (52,53).

We speculate that one of the reasons why the cell aggregates

produced in this study were not transparent is that intracellular

organelles remained and affected light scattering.

In the case of cataracts, a disease that causes

opacity of the lens, several artificial lenses (intraocular lenses;

IOLs) have been developed through micro-incisions and are being

used for clinical treatment. Regeneration of the lens in

vitro is highly intriguing as a basic research subject, but for

clinical application, the regeneration achieved must offer

advantages over current IOL-based treatments. Multifocal IOLs that

can focus at distinct distances are also being developed for

clinical use. In cataract surgery, the lens capsule is preserved

and only the opaque lens is emulsified using ultrasound and then

suctioned out. However, the IOLs currently used in clinical

practice are not perfect, and cataract surgery cannot enhance the

patient's ability to adjust the lens focus, particularly after

surgery. This is because the ciliary muscle connected to the lens

capsule is responsible for the focusing, and considering that the

ciliary body is also connected to the lens capsule (54), the in vitro regeneration of

the ciliary body is also related to the lens capsule and lens. We

aim to continue investigating the collective regeneration of the

lens, lens capsule, and ciliary body in vitro. We believe

that this can contribute to a finer focus adjustment after IOL

implantation if iPS cells can be used to regenerate weakened

ciliary bodies.

In conclusion, we have reported that H-iris cells

and iris tissue-derived iPS cells can be used to generate a variety

of three-dimensional cell aggregates expressing αA-crystallin, a

protein specific to the lens. However, all the cell aggregates

formed in this study were opaque, and we were thus unable to

regenerate a transparent lens. In the future, we will investigate

the degradation of organelles necessary to achieve transparency of

the interior of the generated cell aggregates expressing

lens-specific proteins by creating transgenic cells that induce the

disappearance of organelles, and we will conduct research on the

regeneration of transparent lenses. In addition, we aim to utilize

this cell aggregate model for various applications, such as

studying ciliary body regeneration by co-culture and creating an

in vitro cataract model that can evaluate the effects of

drugs and the effects of radiation exposure.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Chieko Nishikawa

(Fujita Health University) for help with experiments and Ms. Mari

Seto (Kanazawa Medical University) for English editing and

technical support.

Funding

Funding: This research was funded by MEXT/JSPS KAKENHI (grant

nos. 17K11495, 20K09838, and 20K09815).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

NH and NY designed the study. NH, NY and YK were

responsible for the data collection and manuscript writing. NH, NY,

YK, NN, SI and KI participated in the experiments. NH, YK, NN and

SI were responsible for data acquisition and analysis. NY and NN

were responsible for statistical analysis. YK and NN were

responsible for literature searches. NH, NY, YK and SI reviewed and

revised the manuscript. NY and KI confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Review

Committee of Fujita Health University (approval no. 05-065, first

approval date: 21 December 2005, followed by continued ethical

approval; Aichi, Japan). The written informed consent was obtained

from all subjects. The experiment was carried out with the approval

of the Recombinant DNA Experiment Committee of Fujita Health

University (approval no. DP16055, approval date: 17 November 2016;

Aichi, Japan).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kamachi Y, Uchikawa M, Tanouchi A, Sekido

R and Kondoh H: Pax6 and SOX2 form a co-DNA-binding partner complex

that regulates initiation of lens development. Genes Dev.

15:1272–1286. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chow RL and Lang RA: Early eye development

in vertebrates. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 17:255–296. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Iribarren R: Crystalline lens and

refractive development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 47:86–106.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Morishita H, Eguchi T, Tsukamoto S,

Sakamaki Y, Takahashi S, Saito C, Koyama-Honda I and Mizushima N:

Organelle degradation in the lens by PLAAT phospholipases. Nature.

592:634–638. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kuszak JR, Zoltoski RK and Tiedemann CE:

Development of lens sutures. Int J Dev Biol. 48:889–902.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Yamamoto N, Tanikawa A and Horiguchi M:

Basic study of retinal stem/progenitor cell separation from mouse

iris tissue. Med Mol Morphol. 43:139–144. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Griep AE: Cell cycle regulation in the

developing lens. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 17:686–697. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Fujii N, Sakaue H, Sasaki H and Fujii N: A

rapid, comprehensive liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry

(LC-MS)-based survey of the Asp isomers in crystallins from human

cataract lenses. J Biol Chem. 287:39992–40002. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Delaye M and Tardieu A: Short-range order

of crystallin proteins accounts for eye lens transparency. Nature.

302:415–417. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Magami K, Hachiya N, Morikawa K, Fujii N

and Takata T: Isomerization of Asp is essential for assembly of

amyloid-like fibrils of αA-crystallin-derived peptide. PLoS One.

16(e0250277)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Sprague-Piercy MA, Rocha MA, Kwok AO and

Martin RW: α-Crystallins in the vertebrate eye lens: Complex

oligomers and molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 72:143–163.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Takata T, Murakami K, Toyama A and Fujii

N: Identification of isomeric aspartate residues in βB2-crystallin

from aged human lens. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom.

1866:767–774. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Eguchi G, Eguchi Y, Nakamura K, Yadav MC,

Millán JL and Tsonis PA: Regenerative capacity in newts is not

altered by repeated regeneration and ageing. Nat Commun.

2(384)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Barbosa-Sabanero K, Hoffmann A, Judge C,

Lightcap N, Tsonis PA and Del Rio-Tsonis K: Lens and retina

regeneration: New perspectives from model organisms. Biochem J.

447:321–334. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Gwon A: Lens regeneration in mammals: A

review. Surv Ophthalmol. 51:51–62. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gwon A, Gruber LJ and Mantras C: Restoring

lens capsule integrity enhances lens regeneration in New Zealand

albino rabbits and cats. J Cataract Refract Surg. 19:735–746.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Gwon A, Gruber L, Mantras C and Cunanan C:

Lens regeneration in New Zealand albino rabbits after endocapsular

cataract extraction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 34:2124–2129.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lin H, Ouyang H, Zhu J, Huang S, Liu Z,

Chen S, Cao G, Li G, Signer RA, Xu Y, et al: Lens regeneration

using endogenous stem cells with gain of visual function. Nature.

531:323–328. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu X, Zhang M and Liu Y, Challa P,

Gonzalez P and Liu Y: Proteomic analysis of regenerated rabbit

lenses reveal crystallin expression characteristic of adult

rabbits. Mol Vis. 14:2404–2412. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M,

Ichisaka T, Tomoda K and Yamanaka S: Induction of pluripotent stem

cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell.

131:861–872. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chen P, Chen JZ, Shao CY, Li CY, Zhang YD,

Lu WJ, Fu Y, Gu P and Fan X: Treatment with retinoic acid and lens

epithelial cell-conditioned medium in vitro directed the

differentiation of pluripotent stem cells towards corneal

endothelial cell-like cells. Exp Ther Med. 9:351–360.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Qiu X, Yang J, Liu T, Jiang Y, Le Q and Lu

Y: Efficient generation of lens progenitor cells from cataract

patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. PLoS One.

7(e32612)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, Katori R, Sasamoto

Y, Taniwaki Y, Takayanagi H, Tsujikawa M, Sekiguchi K, Quantock AJ

and Nishida K: Coordinated generation of multiple ocular-like cell

lineages and fabrication of functional corneal epithelial cell

sheets from human iPS cells. Nat Protoc. 12:683–696.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Liu Z, Wang R, Lin H and Liu Y: Lens

regeneration in humans: Using regenerative potential for tissue

repairing. Ann Transl Med. 8(1544)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sun G, Asami M, Ohta H, Kosaka J and

Kosaka M: Retinal stem/progenitor properties of iris pigment

epithelial cells. Dev Biol. 289:243–252. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Yamamoto N, Hiramatsu N, Ohkuma M,

Hatsusaka N, Takeda S, Nagai N, Miyachi EI, Kondo M, Imaizumi K,

Horiguchi M, et al: Novel technique for retinal nerve cell

regeneration with electrophysiological functions using human

iris-derived iPS cells. Cells. 10(743)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Drozd AM, Walczak MP, Piaskowski S,

Stoczynska-Fidelus E, Rieske P and Grzela DP: Generation of human

iPSCs from cells of fibroblastic and epithelial origin by means of

the oriP/EBNA-1 episomal reprogramming system. Stem Cell Res Ther.

6(122)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yamamoto N, Takeda S, Hatsusaka N,

Hiramatsu N, Nagai N, Deguchi S, Nakazawa Y, Takata T, Kodera S,

Hirata A, et al: Effect of a lens protein in low-temperature

culture of novel immortalized human lens epithelial cells

(iHLEC-NY2). Cells. 9(2670)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Yang C, Yang Y, Brennan L, Bouhassira EE,

Kantorow M and Cvekl A: Efficient generation of lens progenitor

cells and lentoid bodies from human embryonic stem cells in

chemically defined conditions. FASEB J. 24:3274–3283.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, Sasamoto Y, Katori

R, Nomura N, Ichikawa T, Araki S, Soma T, Kawasaki S, Sekiguchi K,

et al: Co-ordinated ocular development from human iPS cells and

recovery of corneal function. Nature. 531:376–380. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hiramatsu N, Yamamoto N, Isogai S, Onouchi

T, Hirayama M, Maeda S, Ina T, Kondo M and Imaizumi K: An analysis

of monocytes and dendritic cells differentiated from human

peripheral blood monocyte-derived induced pluripotent stem cells.

Med Mol Morphol. 53:63–72. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Krogerus L and Kholova I: Cell block in

cytological diagnostics: Review of preparatory techniques. Acta

Cytol. 62:237–243. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Isogai S, Yamamoto N, Hiramatsu N, Goto Y,

Hayashi M, Kondo M and Imaizumi K: Preparation of induced

pluripotent stem cells using human peripheral blood monocytes. Cell

Reprogram. 20:347–355. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Henry JJ and Hamilton PW: Diverse

evolutionary origins and mechanisms of lens regeneration. Mol Biol

Evol. 35:1563–1575. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Papaconstantinou J: L.S. stone: Lens

regeneration-contributions to the establishment of an in vivo model

of transdifferentiation. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 301:787–792.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hayashi T, Mizuno N, Takada R, Takada S

and Kondoh H: Determinative role of Wnt signals in dorsal

iris-derived lens regeneration in newt eye. Mech Dev. 123:793–800.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sousounis K, Qi F, Yadav MC, Millán JL,

Toyama F, Chiba C, Eguchi Y, Eguchi G and Tsonis PA: A robust

transcriptional program in newts undergoing multiple events of lens

regeneration throughout their lifespan. Elife.

4(e09594)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Eguchi G, Abe SI and Watanabe K:

Differentiation of lens-like structures from newt iris epithelial

cells in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 71:5052–5056.

1974.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Kodama R and Eguchi G: From lens

regeneration in the newt to in-vitro transdifferentiation of

vertebrate pigmented epithelial cells. Semin Cell Biol. 6:143–149.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kosaka M, Kodama R and Eguchi G: In vitro

culture system for iris-pigmented epithelial cells for molecular

analysis of transdifferentiation. Exp Cell Res. 245:245–251.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Abe T, Takeda Y, Yamada K, Akaishi K,

Tomita H, Sato M and Tamai M: Cytokine gene expression after

subretinal transplantation. Tohoku J Exp Med. 189:179–189.

1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yamamoto N, Majima K and Marunouchi T: A

study of the proliferating activity in lens epithelium and the

identification of tissue-type stem cells. Med Mol Morphol.

41:83–91. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Furukawa KS, Suenaga H, Toita K, Numata A,

Tanaka J, Ushida T, Sakai Y and Tateishi T: Rapid and large-scale

formation of chondrocyte aggregates by rotational culture. Cell

Transplant. 12:475–479. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Nagai T, Furukawa KS, Sato M, Ushida T and

Mochida J: Characteristics of a scaffold-free articular chondrocyte

plate grown in rotational culture. Tissue Eng Part A. 14:1183–1193.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Duke PJ, Daane EL and Montufar-Solis D:

Studies of chondrogenesis in rotating systems. J Cell Biochem.

51:274–282. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Baker TL and Goodwin TJ: Three-dimensional

culture of bovine chondrocytes in rotating-wall vessels. In Vitro

Cell Dev Biol Anim. 33:358–365. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Marlovits S, Tichy B, Truppe M, Gruber D

and Schlegel W: Collagen expression in tissue engineered cartilage

of aged human articular chondrocytes in a rotating bioreactor. Int

J Artif Organs. 26:319–330. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Cummings CF and Hudson BG: Lens capsule as

a model to study type IV collagen. Connect Tissue Res. 55:8–12.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Matsuura-Hachiya Y, Arai KY, Muraguchi T,

Sasaki T and Nishiyama T: Type IV collagen aggregates promote

keratinocyte proliferation and formation of epidermal layer in

human skin equivalents. Exp Dermatol. 27:443–448. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kelley PB, Sado Y and Duncan MK: Collagen

IV in the developing lens capsule. Matrix Biol. 21:415–423.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Nomi K, Hayashi R, Ishikawa Y, Kobayashi

Y, Katayama T, Quantock AJ and Nishida K: Generation of functional

conjunctival epithelium, including goblet cells, from human iPSCs.

Cell Rep. 34(108715)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Barbiero G, Duranti F, Bonelli G, Amenta

JS and Baccino FM: Intracellular ionic variations in the apoptotic

death of L cells by inhibitors of cell cycle progression. Exp Cell

Res. 217:410–418. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

de Gann MP, Belaud-Rotureau MA, Voisin P,

Leducq N, Belloc F, Canioni P and Diolez P: Flow cytometric

analysis of mitochondrial activity in situ: Application to

acetylceramide-induced mitochondrial swelling and apoptosis.

Cytometry. 33:333–339. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Kinoshita H, Suzuma K, Kaneko J, Mandai M,

Kitaoka T and Takahashi M: Induction of functional 3D ciliary

epithelium-like structure from mouse induced pluripotent stem

cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 57:153–161. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|