Ion channels are pore-creating proteins that allow

the flow of inorganic ions through the cell membrane, plasma

membrane or intracellular organelles in a variety of tissues. They

can also provide a rapid diffusion pathway depending on the

electrochemical potential of the ions across the cell membrane.

Therefore, they can regulate the intracellular and extracellular

ion concentration involved in the establishment of membrane

potential, thus enabling them to play a notable role in several

physiological activities. Such basic physiological activities

include muscle contraction, protrusion transmission, action

potential transmission and cell secretion (1-6).

The three Nobel Prizes in physiology or medicine in

1963 and 1991 and in chemistry in 2003, revealed the necessary to

research the structure and function of ion channels (1). Ion channels are characterized by two

fundamental features, namely selectivity and gating (2). Therefore, depending on the

sensitivity of the gate to different stimuli, the ion channels can

be divided into voltage-, chemically- and mechanically gated

subgroups. The majority of ion channels, such as K+,

Na+, Ca2+, HCN and transient receptor

potential (TRP) channels, are similar in structure and form the

subgroup of voltage-gated channels since they may arise from the

same distant progenitor gene. Other ion channels such as

Cl-, aquaporins and junction proteins have different

structures compared with voltage-gated channels (1,2). The

function of ion channels is to respond to the opening and closing

of gating cues and to determine the types of ions that can pass

through. Additionally, ion channels consist of a ligand-binding and

ion permeation mechanism. Currently, the mechanisms underlying ion

permeation remains unclear (7,8).

Since several diseases are caused by ion channel mutations or other

dysfunctions, ion channels are considered major therapeutic targets

(9,10).

Proteinuria is a condition characterized by the

presence of protein in the urine at >150 mg/24 h or by positive

result from qualitative urinalysis testing. Proteinuria can be

divided into five categories: i) physiological proteinuria; ii)

glomerulinuria; iii) tubulminuria; iv) overload proteinuria; and v)

mixed proteinuria. The occurrence of proteinuria is closely

associated with impaired glomerular filtration membrane, which can

affect glomerular selective filtration function, thus allowing

several macromolecular substances, including proteins, to pass

through the filtration membrane, eventually promoting the

development of proteinuria (11).

The glomerular filtration membrane consists of glomerular capillary

endothelial cells (ECs), the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and

renal capsule visceral layer epithelial cells (podocytes) (12-14).

The outermost layer of the glomerular basement membrane, the

outermost podocyte foot processes and its inter slit diaphragm (SD;

fissure membrane) are the main barriers of the glomerular

filtration membrane, as such they are key points of weakness in the

development of proteinuria (12-14).

The SD is a thin film between the adjacent bipedal processes on the

epithelial side of the GBM and is an isoaperture zipper-like

electron dense structure that forms the final part of the molecular

barrier and plays a significant role in preventing the efflux of

the majority of proteins (15).

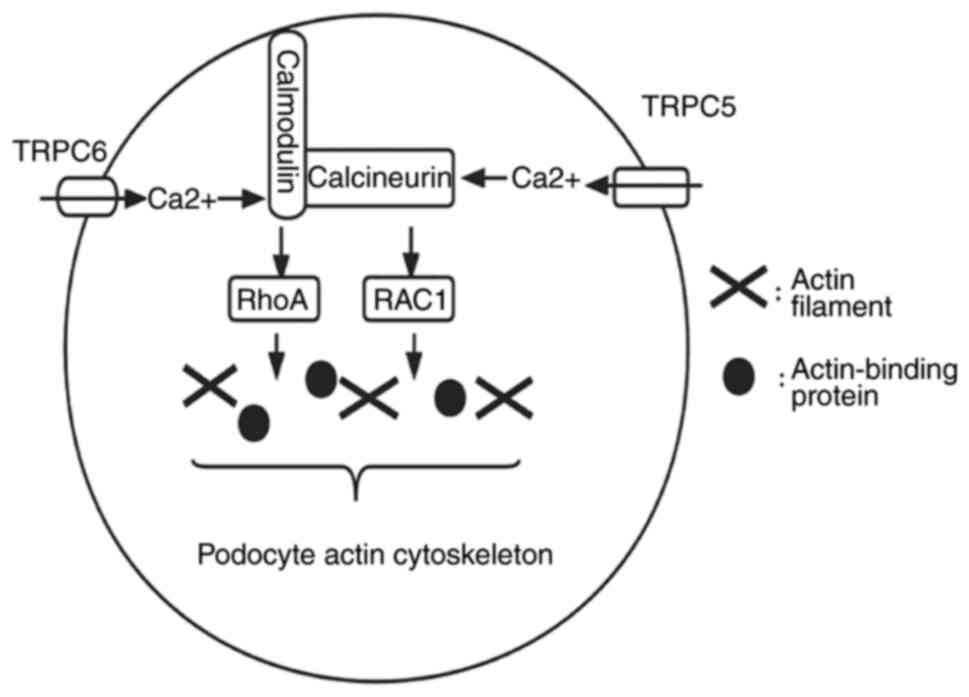

When podocytes are damaged by several factors (such as genetic

abnormalities or infection) the expression of SD-related proteins

can decrease, leading to foot process fusion (a manifestation of

podocyte damage, which can increase glomerular permeability to

macromolecular substances) and GBM shedding, eventually resulting

in proteinuria. SD-associated proteins include nephrotic protein

(nephrin), podocyte cleft membrane protein (podocin),

CD2-associated protein and TRP cation channel protein (TRPC)

(16) and each protein plays a

different role. Nephrin maintains the structural strength of SD and

participates in the signal transmission of podocytes to regulate

the remodeling of podocyte cytoskeleton; podocin can form protein

complexes in the lipid microdomain of foot process membrane and

regulates SD filtration permeability through signal transduction;

CD2AP is important for maintaining the integrity of the structure

and function of podocytes; and the role of TRPC is described in

Ca2+ channels (15,16).

In addition, proteinuria is one of the suggestive indicators of

kidney diseases and contributes to the diagnosis of these diseases.

Currently, studies have supported the association between the onset

of proteinuria and the activation or inhibition of ion channels

(8,12). Therefore, further understanding of

the mechanism underlying the action of ion channels and that of the

related ion transporters in proteinuria could advance targeted

therapy in patients with kidney disease-induced proteinuria.

TRP channels, a class of cationic channel proteins,

act as signal converters via altering membrane potential or the

intracellular concentration of Ca2+ (56,57).

In 1989, Montell and Rubin (58)

identified the TRP ion channels. TRP channels can be divided into

the following six subfamilies: i) TRPA (ankyrin); ii) TRPC

(canonical); iii) TRPM (melastatin); iv) TRPML (mucolipin); v) TRPP

(polycystin); and vi) TRPV (vanilloid) (59-61).

TRP channels can be activated through several pathways, such as

intracellular or extracellular transmitters, chemical stimulation

and osmotic pressure. Furthermore, the body can perceive the

changes of the external environment through the instantaneous

receptor potential channels in the surrounding environment, thus

protecting the body (62-67).

The current review article focused on the roles of TRPC and TRPV4

on proteinuria.

The TRPV4 receptor is expressed in the

cardiovascular system, including endothelial cells, cardiac

fibroblasts, VSMCs and perivascular nerves, but also in the

kidneys. This receptor can be activated by physical factors such as

high temperature and mechanical stimulation as well as by chemical

factors such as arachidonic acid (88-92).

Gualdani et al (93) showed

that fluid flow-induced mechanical force in proximal renal tubules

activates TRPV4 and promotes the endocytosis of albumin in proximal

renal tubular epithelial cells (Fig.

4), thus promoting albumin retention. Perineuria is also

significantly increased in TRPV4-depleted tubular cells in mice

when the glomerular filter permeability in the proximal tubules is

enhanced. Taken together, the TRPV4-mediated defects in endocytosis

may underlie proteinuria and therefore TRPV4 receptors can be

considered as promising targets for controlling proteinuria

(93).

Transporters are the other types of membrane

proteins that mediate the flow of ions through the cell membrane.

These proteins are different from ion channels. Pumps, the main

active transporters, use energy generated by ATP hydrolysis to

transport ions against electrochemical gradients, independent of

passive diffusion (131). In

addition, pumps are involved in several activities, such as

maintaining ion homeostasis by regulating the activity of pumps,

and require one or more proteins to maintain, including

Na+/K+-ATPases and

Na+/H+ exchanger proteins (131,132). Orlov et al (133) showed that proteinuria is

associated with abnormalities in the ion transporter

Na+/H+ exchange factor and

Na+/K+/2Cl- co-transporter in a

human model of primary hypertension. Hypertension and proteinuria

are the main features of preeclampsia (134). Graves (134) demonstrated that the above effect

is partially due to defects in Na+/K+-ATPases

or Na+ pumps. ClC-5 is the Cl-/H+

anti-transporter expressed in early proximal tubular endosomes

(135). When the function of

ClC-5 is impaired in endosomes, not only is the expression of

Na+/H+ exchange factors on the apical surface

of proximal tubules altered, but also reabsorption of low molecular

weight proteins and proximal tubular cell dysfunction are observed,

thus leading to albuminuria (135-137).

A study on a nephrotic syndrome rat model revealed that

amiloride-sensitive ENaCs are activated and the expression levels

of Na+ transporters are reduced in proximal renal

tubules, which may be due to the compensatory function (138). Furthermore, Gadau et al

(139) used an anti-Thy1

vasoproliferative glomerulonephritis rat model to evaluate the

association between the changes in Na+ and water

homeostasis and those in the renal tubular epithelium with

Na+ retention. The results showed that the abundance of

salt and water transporters (Na+/H+

exchanger-3, Na+/K+/2Cl-

co-transporter and aquaprin-1) in the proximal tubular brush border

membrane decreased, thus indicating that ion transporters are a

relevant mechanism of channel activation in glomerular diseases.

These findings suggest that there is an association between the

above mechanism and the occurrence and development of proteinuria.

In addition, de Seigneux et al (140) investigated the association

between proteinuria and phosphoremia in a nephrotic proteinuria

mouse model. The results showed that expression of

Na+/Na+ phosphate apical symporter is

abnormal in mice with proteinuria, while the albuminuria-induced

alterations on phosphate tubular handling are not associated with

the glomerular filtration rate. Another study by Shimizu et

al (141) exploring the

effects of N-acetylcysteine on kidney function and Na+

and water transporters in mice, showed that

Na+/K+/2Cl- co-transporter 2 and

aquaporin 2 are both upregulated and proteinuria is alleviated in

mice in that received the treatment. The above studies support an

association between proteinuria and ion transporters, thus

indicating that ion transporters could also be considered as

therapeutic targets for reducing proteinuria in patients.

Proteinuria is a significantly distinct determinant

of kidney disease progression and mortality. Therefore, unravelling

the mechanism of action of Na+, Ca2+,

Cl- and K+ channels and ion transporters in

proteinuria could provide novel insights into the identification of

novel targets for treating proteinuria and delaying kidney

diseases.

We thank Dr Yanqiang Wang (Department of Neurology

II, Affiliated Hospital of Weifang Medical University, Weifang,

China) for his instructive advice and useful suggestions and

providing help to finish the present review.

Funding: No funding was received.

Not applicable.

JL, XuL and NX wrote the review, collected

literature information and created figures. HH and XiL reviewed the

manuscript and proposed final revisions. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Kondratskyi A, Kondratska K, Skryma R,

Klionsky DJ and Prevarskaya N: Ion channels in the regulation of

autophagy. Autophagy. 14:3–21. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA, Veale

EL, Striessnig J, Kelly E, Armstrong JF, Faccenda E, Harding SD,

Pawson AJ, et al: The concise guide to pharmacology 2019/20: Ion

channels. Br J Pharmacol. 176 (Suppl 1):S142–S228. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Roux B: Ion channels and ion selectivity.

Essays Biochem. 61:201–209. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cheng J, Wen J, Wang N, Wang C, Xu Q and

Yang Y: Ion channels and vascular diseases. Arterioscler Thromb

Vasc Biol. 39:e146–e156. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Anderson KJ, Cormier RT and Scott PM: Role

of ion channels in gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastroenterol.

25:5732–5772. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Armijo JA, Shushtarian M, Valdizan EM,

Cuadrado A, de las Cuevas I and Adín J: Ion channels and epilepsy.

Curr Pharm Des. 11:1975–2003. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Moiseenkova-Bell V, Delemotte L and Minor

DL Jr: Ion channels: Intersection of structure, function, and

pharmacology. J Mol Biol. 433(167102)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wang L and Yule DI: Differential

regulation of ion channels function by proteolysis. Biochim Biophys

Acta Mol Cell Res. 1865:1698–1706. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Catterall WA, Lenaeus MJ and Gamal El-Din

TM: Structure and pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium and calcium

channels. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 60:133–154. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

De Logu F and Geppetti P: Ion channel

pharmacology for pain modulation. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 260:161–186.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pallet N, Bastard JP, Claeyssens S,

Fellahi S, Delanaye P, Piéroni L and Caussé E: groupe de travail

SFBC, SFNDT, SNP. Proteinuria typing: How, why and for whom? Ann

Biol Clin (Paris). 77:13–25. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Barton M: Reversal of proteinuric renal

disease and the emerging role of endothelin. Nat Clin Pract

Nephrol. 4:490–501. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Nowak A and Serra AL: Assessment of

proteinuria. Praxis (Bern 1994). 102:797–802. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

14

|

D'Amico G and Bazzi C: Pathophysiology of

proteinuria. Kidney Int. 63:809–825. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Menzel S and Moeller MJ: Role of the

podocyte in proteinuria. Pediatr Nephrol. 26:1775–1780.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Miner JH: Glomerular basement membrane

composition and the filtration barrier. Pediatr Nephrol.

26:1413–1417. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kallen RG, Cohen SA and Barchi RL:

Structure, function and expression of voltage-dependent sodium

channels. Mol Neurobiol. 7:383–428. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lee CH and Ruben PC: Interaction between

voltage-gated sodium channels and the neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin.

Channels (Austin). 2:407–412. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hanukoglu I and Hanukoglu A: Epithelial

sodium channel (ENaC) family: Phylogeny, structure-function, tissue

distribution, and associated inherited diseases. Gene. 579:95–132.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Brunklaus A, Ellis R, Reavey E, Semsarian

C and Zuberi SM: Genotype phenotype associations across the

voltage-gated sodium channel family. J Med Genet. 51:650–658.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Soundararajan R, Pearce D, Hughey RP and

Kleyman TR: Role of epithelial sodium channels and their regulators

in hypertension. J Biol Chem. 285:30363–30369. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Büsst CJ: Blood pressure regulation via

the epithelial sodium channel: From gene to kidney and beyond. Clin

Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 40:495–503. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zachar RM, Skjødt K, Marcussen N, Walter

S, Toft A, Nielsen MR, Jensen BL and Svenningsen P: The epithelial

sodium channel γ-subunit is processed proteolytically in human

kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 26:95–106. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Svenningsen P, Friis UG, Bistrup C, Buhl

KB, Jensen BL and Skøtt O: Physiological regulation of epithelial

sodium channel by proteolysis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens.

20:529–533. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ware AW, Rasulov SR, Cheung TT, Lott JS

and McDonald FJ: Membrane trafficking pathways regulating the

epithelial Na+ channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

318:F1–F13. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Bockenhauer D: Over- or underfill: Not all

nephrotic states are created equal. Pediatr Nephrol. 28:1153–1156.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Larionov A, Dahlke E, Kunke M, Zanon

Rodriguez L, Schiessl IM, Magnin JL, Kern U, Alli AA, Mollet G,

Schilling O, et al: Cathepsin B increases ENaC activity leading to

hypertension early in nephrotic syndrome. J Cell Mol Med.

23:6543–6553. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Fila M, Sassi A, Brideau G, Cheval L,

Morla L, Houillier P, Walter C, Gennaoui M, Collignon L, Keck M, et

al: A variant of ASIC2 mediates sodium retention in nephrotic

syndrome. JCI Insight. 6(e148588)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Svenningsen P, Skøtt O and Jensen BL:

Proteinuric diseases with sodium retention: Is plasmin the link?

Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 39:117–124. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hinrichs GR, Jensen BL and Svenningsen P:

Mechanisms of sodium retention in nephrotic syndrome. Curr Opin

Nephrol Hypertens. 29:207–212. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Passero CJ, Hughey RP and Kleyman TR: New

role for plasmin in sodium homeostasis. Curr Opin Nephrol

Hypertens. 19:13–19. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Briet M and Schiffrin EL: Aldosterone:

Effects on the kidney and cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Nephrol.

6:261–273. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shapovalov G, Skryma R and Prevarskaya N:

Calcium channels and prostate cancer. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug

Discov. 8:18–26. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Prevarskaya N, Ouadid-Ahidouch H, Skryma R

and Shuba Y: Remodelling of Ca2+ transport in cancer: How it

contributes to cancer hallmarks? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol

Sci. 369(20130097)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Mignen O, Thompson JL and Shuttleworth TJ:

Ca2+ selectivity and fatty acid specificity of the noncapacitative,

arachidonate-regulated Ca2+ (ARC) channels. J Biol Chem.

278:10174–10181. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Lewis RS: Store-operated calcium channels:

From function to structure and back again. Cold Spring Harb

Perspect Biol. 12(a035055)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Zhou Y and Greka A: Calcium-permeable ion

channels in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

310:F1157–F1167. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Patergnani S, Danese A, Bouhamida E,

Aguiari G, Previati M, Pinton P and Giorgi C: Various aspects of

calcium signaling in the regulation of apoptosis, autophagy, cell

proliferation, and cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 21(8323)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Lou J, Yang X, Shan W, Jin Z, Ding J, Hu

Y, Liao Q, Du Q, Xie R and Xu J: Effects of calcium-permeable ion

channels on various digestive diseases in the regulation of

autophagy (review). Mol Med Rep. 24(680)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Perez-Reyes E: Molecular physiology of

low-voltage-activated t-type calcium channels. Physiol Rev.

83:117–161. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zamponi GW, Striessnig J, Koschak A and

Dolphin AC: The physiology, pathology, and pharmacology of

voltage-gated calcium channels and their future therapeutic

potential. Pharmacol Rev. 67:821–870. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Catterall WA: Voltage-gated calcium

channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 3(a003947)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Sairaman A, Cardoso FC, Bispat A, Lewis

RJ, Duggan PJ and Tuck KL: Synthesis and evaluation of

aminobenzothiazoles as blockers of N- and T-type calcium channels.

Bioorg Med Chem. 26:3046–3059. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Tsunemi T, Saegusa H, Ishikawa K, Nagayama

S, Murakoshi T, Mizusawa H and Tanabe T: Novel Cav2.1 splice

variants isolated from Purkinje cells do not generate P-type Ca2+

current. J Biol Chem. 277:7214–7221. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Yamaguchi S, Okamura Y, Nagao T and

Adachi-Akahane S: Serine residue in the IIIS5-S6 linker of the

L-type Ca2+ channel alpha 1C subunit is the critical determinant of

the action of dihydropyridine Ca2+ channel agonists. J Biol Chem.

275:41504–41511. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Hansen PB: Functional and pharmacological

consequences of the distribution of voltage-gated calcium channels

in the renal blood vessels. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 207:690–699.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ohta M, Sugawara S, Sato N, Kuriyama C,

Hoshino C and Kikuchi A: Effects of benidipine, a long-acting

T-type calcium channel blocker, on home blood pressure and renal

function in patients with essential hypertension: A retrospective,

‘real-world’ comparison with amlodipine. Clin Drug Investig.

29:739–746. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mishima K, Maeshima A, Miya M, Sakurai N,

Ikeuchi H, Hiromura K and Nojima Y: Involvement of N-type Ca(2+)

channels in the fibrotic process of the kidney in rats. Am J

Physiol Renal Physiol. 304:F665–F673. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Tamargo J and Ruilope LM: Investigational

calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension. Expert

Opin Investig Drugs. 25:1295–1309. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Khanna R, Yu J, Yang X, Moutal A,

Chefdeville A, Gokhale V, Shuja Z, Chew LA, Bellampalli SS, Luo S,

et al: Targeting the CaVα-CaVβ interaction yields an antagonist of

the N-type CaV2.2 channel with broad antinociceptive efficacy.

Pain. 160:1644–1661. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Ando K: L-/N-type calcium channel blockers

and proteinuria. Curr Hypertens Rev. 9:210–218. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Lei B, Nakano D, Fujisawa Y, Liu Y, Hitomi

H, Kobori H, Mori H, Masaki T, Asanuma K, Tomino Y and Nishiyama A:

N-type calcium channel inhibition with cilnidipine elicits

glomerular podocyte protection independent of sympathetic nerve

inhibition. J Pharmacol Sci. 119:359–367. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Fan YY, Kohno M, Nakano D, Ohsaki H,

Kobori H, Suwarni D, Ohashi N, Hitomi H, Asanuma K, Noma T, et al:

Cilnidipine suppresses podocyte injury and proteinuria in metabolic

syndrome rats: Possible involvement of N-type calcium channel in

podocyte. J Hypertens. 28:1034–1043. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Tamargo J: New calcium channel blockers

for the treatment of hypertension. Hipertens Riesgo Vasc. 34 (Suppl

2):S5–S8. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Spanish).

|

|

55

|

Hansen PB, Poulsen CB, Walter S, Marcussen

N, Cribbs LL, Skøtt O and Jensen BL: Functional importance of L-

and P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels in human renal

vasculature. Hypertension. 58:464–470. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Nilius B and Owsianik G: The transient

receptor potential family of ion channels. Genome Biol.

12(218)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Ramsey IS, Delling M and Clapham DE: An

introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 68:619–647.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Montell C and Rubin GM: Molecular

characterization of the Drosophila trp locus: A putative integral

membrane protein required for phototransduction. Neuron.

2:1313–1323. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Gees M, Owsianik G, Nilius B and Voets T:

TRP channels. Compr Physiol. 2:563–608. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Caterina MJ and Pang Z: TRP channels in

skin biology and pathophysiology. Pharmaceuticals (Basel).

9(77)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Li H: TRP channel classification. Adv Exp

Med Biol. 976:1–8. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Zhao Y, McVeigh BM and Moiseenkova-Bell

VY: Structural pharmacology of TRP channels. J Mol Biol.

433(166914)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Nilius B: TRP channels in disease. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1772:805–812. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Moran MM: TRP channels as potential drug

targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 58:309–330. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Koivisto AP, Belvisi MG, Gaudet R and

Szallasi A: Advances in TRP channel drug discovery: From target

validation to clinical studies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 21:41–59.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Feng YL, Chen H, Chen DQ, Vaziri ND, Su W,

Ma SX, Shang YQ, Mao JR, Yu XY, Zhang L, et al: Activated

NF-κB/Nrf2 and Wnt/β-catenin pathways are associated with lipid

metabolism in CKD patients with microalbuminuria and

macroalbuminuria. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1865:2317–2332. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Voets T, Vriens J and Vennekens R:

Targeting TRP channels-valuable alternatives to combat pain, lower

urinary tract disorders, and type 2 diabetes? Trends Pharmacol Sci.

40:669–683. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Wang Q, Tian X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Li J, Zhao

T and Li P: Role of transient receptor potential canonical channel

6 (TRPC6) in diabetic kidney disease by regulating podocyte actin

cytoskeleton rearrangement. J Diabetes Res.

2020(6897390)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Bacsa B, Tiapko O, Stockner T and

Groschner K: Mechanisms and significance of Ca2+ entry

through TRPC channels. Curr Opin Physiol. 17:25–33. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Möller CC, Flesche J and Reiser J:

Sensitizing the slit diaphragm with TRPC6 ion channels. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 20:950–953. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Möller CC, Wei C, Altintas MM, Li J, Greka

A, Ohse T, Pippin JW, Rastaldi MP, Wawersik S, Schiavi S, et al:

Induction of TRPC6 channel in acquired forms of proteinuric kidney

disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 18:29–36. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Schaldecker T, Kim S, Tarabanis C, Tian D,

Hakroush S, Castonguay P, Ahn W, Wallentin H, Heid H, Hopkins CR,

et al: Inhibition of the TRPC5 ion channel protects the kidney

filter. J Clin Invest. 123:5298–5309. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Tian D, Jacobo SM, Billing D, Rozkalne A,

Gage SD, Anagnostou T, Pavenstädt H, Hsu HH, Schlondorff J, Ramos A

and Greka A: Antagonistic regulation of actin dynamics and cell

motility by TRPC5 and TRPC6 channels. Sci Signal.

3(ra77)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Shalygin A, Shuyskiy LS, Bohovyk R,

Palygin O, Staruschenko A and Kaznacheyeva E: Cytoskeleton

rearrangements modulate TRPC6 channel activity in podocytes. Int J

Mol Sci. 22(4396)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Schlondorff J: TRPC6 and kidney disease:

Sclerosing more than just glomeruli? Kidney Int. 91:773–775.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Schlöndorff JS and Pollak MR: TRPC6 in

glomerular health and disease: What we know and what we believe.

Semin Cell Dev Biol. 17:667–674. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Kim EY, Yazdizadeh Shotorbani P and Dryer

SE: Trpc6 inactivation confers protection in a model of severe

nephrosis in rats. J Mol Med (Berl). 96:631–644. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Hall G, Wang L and Spurney RF: TRPC

channels in proteinuric kidney diseases. Cells.

9(44)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

van der Wijst J and Bindels RJM: Renal

physiology: TRPC5 inhibition to treat progressive kidney disease.

Nat Rev Nephrol. 14:145–146. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Walsh L, Reilly JF, Cornwall C, Gaich GA,

Gipson DS, Heerspink HJL, Johnson L, Trachtman H, Tuttle KR, Farag

YMK, et al: Safety and efficacy of GFB-887, a TRPC5 channel

inhibitor, in patients with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis,

treatment-resistant minimal change disease, or diabetic

nephropathy: TRACTION-2 trial design. Kidney Int Rep. 6:2575–2584.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Reiser J, Polu KR, Möller CC, Kenlan P,

Altintas MM, Wei C, Faul C, Herbert S, Villegas I, Avila-Casado C,

et al: TRPC6 is a glomerular slit diaphragm-associated channel

required for normal renal function. Nat Genet. 37:739–744.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Wiggins RC: The spectrum of

podocytopathies: A unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney

Int. 71:1205–1214. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Zhou Y, Castonguay P, Sidhom EH, Clark AR,

Dvela-Levitt M, Kim S, Sieber J, Wieder N, Jung JY, Andreeva S, et

al: A small-molecule inhibitor of TRPC5 ion channels suppresses

progressive kidney disease in animal models. Science.

358:1332–1336. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Zhang H, Ding J, Fan Q and Liu S: TRPC6

up-regulation in Ang II-induced podocyte apoptosis might result

from ERK activation and NF-kappaB translocation. Exp Biol Med

(Maywood). 234:1029–1036. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Wang Z, Wei X, Zhang Y, Ma X, Li B, Zhang

S, Du P, Zhang X and Yi F: NADPH oxidase-derived ROS contributes to

upregulation of TRPC6 expression in puromycin

aminonucleoside-induced podocyte injury. Cell Physiol Biochem.

24:619–626. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Kistler AD, Singh G, Altintas MM, Yu H,

Fernandez IC, Gu C, Wilson C, Srivastava SK, Dietrich A, Walz K, et

al: Transient receptor potential channel 6 (TRPC6) protects

podocytes during complement-mediated glomerular disease. J Biol

Chem. 288:36598–36609. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Zhou Y, Kim C, Pablo JLB, Zhang F, Jung

JY, Xiao L, Bazua-Valenti S, Emani M, Hopkins CR, Weins A and Greka

A: TRPC5 channel inhibition protects podocytes in

puromycin-aminonucleoside induced nephrosis models. Front Med

(Lausanne). 8(721865)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Randhawa PK and Jaggi AS: TRPV4 channels:

Physiological and pathological role in cardiovascular system. Basic

Res Cardiol. 110(54)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Everaerts W, Nilius B and Owsianik G: The

vanilloid transient receptor potential channel TRPV4: From

structure to disease. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 103:2–17.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Kassmann M, Harteneck C, Zhu Z, Nürnberg

B, Tepel M and Gollasch M: Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1

(TRPV1), TRPV4, and the kidney. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 207:546–564.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Mannaa M, Markó L, Balogh A, Vigolo E,

N'diaye G, Kaßmann M, Michalick L, Weichelt U, Schmidt-Ott KM,

Liedtke WB, et al: Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 channel

deficiency aggravates tubular damage after acute renal ischaemia

reperfusion. Sci Rep. 8(4878)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Karasawa T, Wang Q, Fu Y, Cohen DM and

Steyger PS: TRPV4 enhances the cellular uptake of aminoglycoside

antibiotics. J Cell Sci. 121:2871–2879. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Gualdani R, Seghers F, Yerna X, Schakman

O, Tajeddine N, Achouri Y, Tissir F, Devuyst O and Gailly P:

Mechanical activation of TRPV4 channels controls albumin

reabsorption by proximal tubule cells. Sci Signal.

13(eabc6967)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Duran C, Thompson CH, Xiao Q and Hartzell

HC: Chloride channels: Often enigmatic, rarely predictable. Annu

Rev Physiol. 72:95–121. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Xia J, Wang H, Li S, Wu Q, Sun L, Huang H

and Zeng M: Ion channels or aquaporins as novel molecular targets

in gastric cancer. Mol Cancer. 16(54)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Gururaja Rao S, Ponnalagu D, Patel NJ and

Singh H: Three decades of chloride intracellular channel proteins:

From organelle to organ physiology. Curr Protoc Pharmacol.

80:11.21.1–11.21.17. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Berend K, van Hulsteijn LH and Gans RO:

Chloride: The queen of electrolytes? Eur J Intern Med. 23:203–211.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Jentsch TJ, Stein V, Weinreich F and

Zdebik AA: Molecular structure and physiological function of

chloride channels. Physiol Rev. 82:503–568. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Suzuki M, Morita T and Iwamoto T:

Diversity of Cl(-) channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 63:12–24.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Scheel O, Zdebik AA, Lourdel S and Jentsch

TJ: Voltage-dependent electrogenic chloride/proton exchange by

endosomal CLC proteins. Nature. 436:424–427. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Uchida S: In vivo role of CLC chloride

channels in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 279:F802–F808.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Schriever AM, Friedrich T, Pusch M and

Jentsch TJ: CLC chloride channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol

Chem. 274:34238–34244. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Jentsch TJ and Pusch M: CLC chloride

channels and transporters: Structure, function, physiology, and

disease. Physiol Rev. 98:1493–1590. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Hryciw DH, Ekberg J, Pollock CA and

Poronnik P: ClC-5: A chloride channel with multiple roles in renal

tubular albumin uptake. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 38:1036–1042.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Novarino G, Weinert S, Rickheit G and

Jentsch TJ: Endosomal chloride-proton exchange rather than chloride

conductance is crucial for renal endocytosis. Science.

328:1398–1401. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Devuyst O and Luciani A: Chloride

transporters and receptor-mediated endocytosis in the renal

proximal tubule. J Physiol. 593:4151–4164. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

Günther W, Piwon N and Jentsch TJ: The

ClC-5 chloride channel knock-out mouse-an animal model for Dent's

disease. Pflugers Arch. 445:456–462. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Faria D, Rock JR, Romao AM, Schweda F,

Bandulik S, Witzgall R, Schlatter E, Heitzmann D, Pavenstädt H,

Herrmann E, et al: The calcium-activated chloride channel Anoctamin

1 contributes to the regulation of renal function. Kidney Int.

85:1369–1381. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y,

Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, et al: TMEM16A confers

receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature.

455:1210–1215. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

González C, Baez-Nieto D, Valencia I,

Oyarzún I, Rojas P, Naranjo D and Latorre R: K(+) channels:

Function-structural overview. Compr Physiol. 2:2087–2149.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Sigworth FJ: Potassium channel mechanics.

Neuron. 32:555–556. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Gulbis JM and Doyle DA: Potassium channel

structures: Do they conform? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 14:440–446.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Kuang Q, Purhonen P and Hebert H:

Structure of potassium channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 72:3677–3693.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Noma A: ATP-regulated K+ channels in

cardiac muscle. Nature. 305:147–148. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Ashcroft FM and Rorsman P: K(ATP) channels

and islet hormone secretion: New insights and controversies. Nat

Rev Endocrinol. 9:660–669. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Rorsman P, Ramracheya R, Rorsman NJ and

Zhang Q: ATP-regulated potassium channels and voltage-gated calcium

channels in pancreatic alpha and beta cells: Similar functions but

reciprocal effects on secretion. Diabetologia. 57:1749–1761.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Tinker A, Aziz Q, Li Y and Specterman M:

ATP-sensitive potassium channels and their physiological and

pathophysiological roles. Compr Physiol. 8:1463–1511.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Cole WC, Chen TT and Clément-Chomienne O:

Myogenic regulation of arterial diameter: Role of potassium

channels with a focus on delayed rectifier potassium current. Can J

Physiol Pharmacol. 83:755–765. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Jackson MB, Konnerth A and Augustine GJ:

Action potential broadening and frequency-dependent facilitation of

calcium signals in pituitary nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 88:380–384. 1991.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Guéguinou M, Chantôme A, Fromont G,

Bougnoux P, Vandier C and Potier-Cartereau M: KCa and Ca(2+)

channels: The complex thought. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1843:2322–2333. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

Sforna L, Megaro A, Pessia M, Franciolini

F and Catacuzzeno L: Structure, gating and basic functions of the

Ca2+-activated K channel of intermediate conductance. Curr

Neuropharmacol. 16:608–617. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Walewska A, Kulawiak B, Szewczyk A and

Koprowski P: Mechanosensitivity of mitochondrial large-conductance

calcium-activated potassium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta

Bioenerg. 1859:797–805. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Fezai M, Ahmed M, Hosseinzadeh Z and Lang

F: Up-regulation of the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel

by glycogen synthase kinase GSK3β. Cell Physiol Biochem.

39:1031–1039. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Giebisch G: Potassium channels and the

kidney. Nephrologie. 21:223–228. 2000.PubMed/NCBI(In French).

|

|

125

|

Sorensen CM, Braunstein TH,

Holstein-Rathlou NH and Salomonsson M: Role of vascular potassium

channels in the regulation of renal hemodynamics. Am J Physiol

Renal Physiol. 302:F505–F518. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

126

|

Tamura Y, Tanabe K, Kitagawa W, Uchida S,

Schreiner GF, Johnson RJ and Nakagawa T: Nicorandil, a K(atp)

channel opener, alleviates chronic renal injury by targeting

podocytes and macrophages. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol.

303:F339–F349. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

127

|

Snijder PM, Frenay AR, Koning AM, Bachtler

M, Pasch A, Kwakernaak AJ, van den Berg E, Bos EM, Hillebrands JL,

Navis G, et al: Sodium thiosulfate attenuates angiotensin

II-induced hypertension, proteinuria and renal damage. Nitric

Oxide. 42:87–98. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

128

|

Hyodo T, Oda T, Kikuchi Y, Higashi K,

Kushiyama T, Yamamoto K, Yamada M, Suzuki S, Hokari R, Kinoshita M,

et al: Voltage-gated potassium channel Kv1.3 blocker as a potential

treatment for rat anti-glomerular basement membrane

glomerulonephritis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 299:F1258–F1269.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

129

|

Huang C, Zhang L, Shi Y, Yi H, Zhao Y,

Chen J, Pollock CA and Chen XM: The KCa3.1 blocker TRAM34 reverses

renal damage in a mouse model of established diabetic nephropathy.

PLoS One. 13(e0192800)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

130

|

Piwkowska A, Rogacka D, Audzeyenka I,

Kasztan M, Angielski S and Jankowski M: Insulin increases

glomerular filtration barrier permeability through PKGIα-dependent

mobilization of BKCa channels in cultured rat podocytes. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1852:1599–1609. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

131

|

Neverisky DL and Abbott GW: Ion

channel-transporter interactions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol.

51:257–267. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

132

|

Veiras LC, McFarlin BE, Ralph DL, Buncha

V, Prescott J, Shirvani BS, McDonough JC, Ha D, Giani J, Gurley SB,

et al: Electrolyte and transporter responses to angiotensin II

induced hypertension in female and male rats and mice. Acta Physiol

(Oxf). 229(e13448)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

133

|

Orlov SN, Adragna NC, Adarichev VA and

Hamet P: Genetic and biochemical determinants of abnormal

monovalent ion transport in primary hypertension. Am J Physiol.

276:C511–C536. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

Graves SW: Sodium regulation, sodium pump

function and sodium pump inhibitors in uncomplicated pregnancy and

preeclampsia. Front Biosci. 12:2438–2446. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

135

|

Devuyst O, Jouret F, Auzanneau C and

Courtoy PJ: Chloride channels and endocytosis: New insights from

Dent's disease and ClC-5 knockout mice. Nephron Physiol.

99:p69–p73. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

136

|

Shipman KE and Weisz OA: Making a dent in

dent disease. Function (Oxf). 1(zqaa017)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

137

|

Anglani F, Gianesello L, Beara-Lasic L and

Lieske J: Dent disease: A window into calcium and phosphate

transport. J Cell Mol Med. 23:7132–7142. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

138

|

Svenningsen P, Friis UG, Versland JB, Buhl

KB, Møller Frederiksen B, Andersen H, Zachar RM, Bistrup C, Skøtt

O, Jørgensen JS, et al: Mechanisms of renal NaCl retention in

proteinuric disease. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 207:536–545.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

139

|

Gadau J, Peters H, Kastner C, Kühn H,

Nieminen-Kelhä M, Khadzhynov D, Krämer S, Castrop H, Bachmann S and

Theilig F: Mechanisms of tubular volume retention in

immune-mediated glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 75:699–710.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

140

|

de Seigneux S, Wilhelm-Bals A and

Courbebaisse M: On the relationship between proteinuria and plasma

phosphate. Swiss Med Wkly. 147(w14509)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

141

|

Shimizu MH, Volpini RA, de Bragança AC,

Campos R, Canale D, Sanches TR, Andrade L and Seguro AC:

N-acetylcysteine attenuates renal alterations induced by senescence

in the rat. Exp Gerontol. 48:298–303. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|