Introduction

Obesity is characterized by the excessive

accumulation of body fat due to the imbalance between energy intake

and expenditure (1). Excessive

accumulation of body fat, leading to obesity, is attributed to an

increase in both the size and number of adipocytes differentiated

from preadipocytes (2). Obesity, a

precursor to various metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes,

cardiovascular diseases, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and

cancer, is a global health concern owing its role in the etiology

of various conditions (3).

Furthermore, obesity leads to infectious diseases by weakening the

immune system, thereby increasing the risk of infection by foreign

pathogens and/or worsening the patient prognosis, ultimately

increasing the mortality rate (4,5).

Obese patients exhibited high infection and mortality rates during

the coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (6). Therefore, obesity treatment is

important for protection from such viral pandemics. To date,

numerous pharmaceuticals, such as orlistat, lorcaserin,

phentermine/topiramate and liraglutide, have been developed for

obesity treatment. However, these medications induce various side

effects, such as flatus with discharge, insomnia, dysgeusia, nausea

and headache, affecting their long-term use (7). Consequently, natural product-based

supplements without side effects have been extensively studied for

obesity treatment. Owing to increasing health consciousness,

natural substances are preferred for the development of

anti-obesity products (8).

Chrysosplenium flagelliferum (CF), belonging

to family Saxifragaceae, is a plant mainly found in the

Northern Hemisphere regions, such as Russia, China, Japan and South

Korea (9). CF is traditionally

used to treat inflammation (10).

Methanol extract of CF has been revealed to exert antioxidant and

antibacterial effects against Propionibacterium acnes

(10). However, the

pharmacological efficacy of CF and its potential therapeutic

effects remain largely unexplored. CF is listed as an approved food

ingredient by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety of the Republic

of Korea, and no adverse effects associated with its use have been

reported to date. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to

assess the pharmacological efficacy of CF by evaluating its

anti-obesity and immunostimulatory effects and explore the

underlying mechanisms using a cell-based approach in vitro

to facilitate the development of new functional agents.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents

Dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX),

insulin, Oil red O, PD98059 [extracellular signal-regulated kinase

(ERK)-1/2 inhibitor], SB203580 (p38 inhibitor), SP600125 [c-Jun

N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor], C29 [Toll-like receptor (TLR)2

inhibitor], TAK-242 (TLR4 inhibitor) referred to as TAK hereafter

and BAY 11-7082 [BAY; nuclear factor (NF)-κB inhibitor] were

purchased from MilliporeSigma. Primary antibodies against the

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ (cat. no.

2435), CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α (CEBPα; cat. no. 8178),

adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL; cat. no. 2138),

hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL; cat. no. 4107), phosphorylated

(p)-HSL (cat. no. 4137), perilipin-1 (cat. no. 9349), AMP-activated

protein kinase, catalytic, α-1 (AMPKα also known as AMPK; cat. no.

5831), p-AMPKα (cat. no. 2535), and β-actin (cat. no. 5125), as

well as horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (cat. no.

7074) and anti-mouse IgG (cat. no. 7076) secondary antibodies were

purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. The primary antibody

against PPARγ coactivator 1-α (PGC-1α; cat. no. sc-518025) was

purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Control small

interfering RNA (siRNA; cat. no. 6568) and β-catenin siRNA (cat.

no. sc-29210) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology Inc.

and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., respectively.

Sample preparation

CF was obtained as a dehydrated powder from the

National Institute of Forest Science (Seoul, South Korea). To

prepare the extract, distilled water, with a volume 20-fold that of

CF, was added to 10 g of CF. This mixture underwent a 24-h

extraction process in a water bath at 60˚C. The resultant extract

was lyophilized, re-dissolved in distilled water, and subsequently

used in cellular assays.

Cell culture

RAW264.7 murine macrophages (cat. no. TIB-71) and

3T3-L1 mouse preadipocytes (cat. no. CL-173) were obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection. Culture of RAW264.7 cells was

conducted in a controlled CO2 incubator environment

(37˚C, 5% CO2) using Dulbecco's modified Eagle's

medium/nutrient mixture F-12 (DMEM/F-12) (cat. no. SH3023.01;

Cytiva), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (cat. no.

16000-044; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and a combination

of penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 µg/ml).

Additionally, 3T3-L1 cells were propagated under similar conditions

(37˚C, 5% CO2) in DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 10%

bovine calf serum (cat. no. 16170-078; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and penicillin/streptomycin combination.

Measurement of the viability of

RAW264.7 and 3T3-L1 cells

Cell viability was assessed via

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay. RAW264.7 and 3T3-L1 cells (at >90% confluence in the

wells), following CF treatment (50-200 µg/ml), were incubated for

24 h and 8 days, respectively, in 96-well plates at 37˚C. Following

incubation, the cells were treated with the MTT reagent (1 mg/ml)

and incubated for 4 h at 37˚C. After the addition of dimethyl

sulfoxide, the cells were incubated for 10 min at room temperature.

Finally, absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at 570

nm using the UV/visible spectrophotometer (Xma-3000PC; Human

Corporation).

Differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells

A total of 2 days after reaching full confluence

[designated as day 0 (D0)] in a 6-well culture plate, 3T3-L1

preadipocytes were induced to differentiate. Briefly, the cells (at

100% confluence in the wells) were incubated in DMEM/F-12 enriched

with DMI cocktail (0.05 mM IBMX, 1 µM dexamethasone, and 10 µg/ml

insulin) until D2 at 37˚C. The cells were then cultured for 2 more

days in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10 µg/ml insulin until D4 at

37˚C. The culture continued from D6 to D8 at 37˚C, and the medium

was renewed every other day.

Transfection with siRNA

The 3T3-L1 cells (2x106 cells/well) were

plated in a 6-well plate and incubated overnight to achieve

adherence. Subsequently, the cells were transfected with the

control-siRNA (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.) and β-catenin-siRNA

(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), each at a concentration of 100

nM. Transfection was performed for 48 h using the TransIT-TKO

transfection reagent (Mirus Bio), according to the manufacturer's

protocol. Control-siRNA was used as non-targeting siRNA for the

negative control. Immediately following the completion of siRNA

transfection, cell differentiation was initiated.

Oil red O staining of 3T3-L1

cells

Under differentiation, cells were treated with CF

for D0-D8, D0-D2, or D8-D10 and the concentration of CF used in the

experiments ranged from 50 to 200 µg/ml in the dose-dependent

studies, while it was set at 200 µg/ml in all other cases.

Following treatment, 3T3-L1 cells were fixed with 10% formalin at

an ambient temperature for 1 h. Following fixation, the cells were

rinsed thrice with distilled water and dehydrated using 60%

isopropanol for 5 min at room temperature. Fully dehydrated 3T3-L1

cells were subjected to Oil red O staining for 20 min at room

temperature for lipid droplet visualization. After staining, the

cells were rinsed twice with distilled water and examined under a

light microscope (Olympus Corporation) at a magnification of x400.

To quantify the accumulated lipid droplets, Oil red O was extracted

from the stained lipid droplets in completely dried cells using

100% isopropanol. Finally, absorbance was measured at 500 nm using

the microplate reader (Xma-3000PC).

Measurement of glycerol levels in

3T3-L1 cells

Upon reaching maximum confluency in a 6-well plate,

3T3-L1 cells (at 100% confluence in the wells) were cultured for an

additional 2 days. Post this period (D0), the cells were mixed with

DMI (0.05 mM IBMX, 1 µM dexamethasone and 10 µg/ml insulin) and

incubated for 2 days (D2). The 3T3-L1 cells were then exposed to

insulin (10 µg/ml) and cultured for another 2 days (D4). The cells

were further cultured for 4 days, with the medium refreshed every

other day (D6-D8). Following differentiation, the 3T3-L1 cells were

treated with CF (200 µg/ml) and were incubated for 2 days (D8-D10).

All the steps were performed at a constant temperature of 37˚C in a

5% CO2 environment. After 2 days of CF treatment (D10),

free glycerol content was evaluated using a Glycerol Cell-Based

Assay Kit (cat. no. 10011725; Cayman Chemical Company), according

to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the cell culture

medium was mixed with the prepared free glycerol assay reagent at a

1:4 ratio and incubated at room temperature for 15 min.

Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 540 nm using the

microplate reader (Xma-3000PC).

Measurement of nitric oxide (NO)

levels in RAW264.7 cells

RAW264.7 cells (1x105 cells/well) were

propagated in a 96-well culture plate in DMEM/F-12 supplemented

with 10% FBS. The cells were exposed to CF for 24 h at 37˚C. In

addition, the cells were pretreated with C29 (100 µM, TLR2

inhibitor), TAK (5 µM, TLR4 inhibitor), PD (20 µM, ERK1/2

inhibior), SB (20 µM, p38 inhibitor), SP (20 µM, JNK inhibitor) or

BAY (10 µM, NF-κB inhibitor) at 37˚C for 2 h and then co-treated

with CF (200 µg/ml) at 37˚C for 24 h. To quantify NO levels, the

culture medium was mixed with the Griess reagent (cat. no.

G4410-10G; MilliporeSigma) and incubated for 15 min at ambient

temperature. Absorbance of the resulting mixture was measured at

540 nm using the UV/visible spectrophotometer (Xma-3000PC). The

concentration of CF used in the experiments ranged from 50 to 200

µg/ml in the dose-dependent studies, while it was set at 200 µg/ml

in all other cases.

Measurement of phagocytotic activity

in RAW264.7 cells

Phagocytic activity in RAW264.7 cells was assessed

using the neutral red uptake method. The cells (at over 90%

confluence in the wells) were cultured in DMEM/F-12 enriched with

10% FBS and treated with CF (50-200 µg/ml) at 37˚C for 24 h. In

addition, the cells were pretreated with C29 (100 µM, TLR2

inhibitor) or TAK (5 µM, TLR4 inhibitor) at 37˚C for 2 h and then

co-treated with CF (200 µg/ml) at 37˚C for 24 h. For phagocytic

assessment, the cells were stained with 0.01% neutral red at 37˚C

for 2 h and treated with a lysis solution (50:50 mixture of ethanol

and 1% acetic acid) to extract neutral red at room temperature.

Absorbance of the released dye was measured at 540 nm using the

UV/visible spectrophotometer (Xma-3000PC) to assess the extent of

phagocytic uptake.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

RAW264.7 cells (at >90% confluence in the wells)

were treated with CF for 24 h in the presence or absence of

chemical inhibitors. The concentration of CF used in the

experiments ranged from 50 to 200 µg/ml in the dose-dependent

studies, while it was set at 200 µg/ml in all other cases. Total

RNA was carefully extracted from RAW264.7 cells using the RNeasy

Mini Kit (Qiagen, Inc.). RNA (1 µg) was subsequently

reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the Verso cDNA Kit (Thermo

Fisher Scientific Inc.). RT-PCR analysis was performed targeting

inducible NO synthase (iNOS), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, tumor

necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) using the prepared cDNA and PCR Master Mix

Kit (Promega Corporation). All primers used for amplification are

listed in Table I. PCR cycles (30

in total) were executed in a PCR Thermal Cycler Dice (Takara Bio,

Inc.) as follows: Denaturation at 94˚C for 30 sec, annealing at

55˚C for 1 min, and extension at 72˚C for 1 min. The amplified

products were electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel at 100 V for 15

min. The DNA bands on the agarose gel were visualized using Safe

Shine Green (10,000X) (cat. no. G6051; Biosesang). Band intensities

were quantitatively analyzed using the UN-SCAN-IT 5.1 software

(Silk Scientific, Inc). GAPDH was used as a loading control for

normalization in RT-PCR analysis.

| Table ISequences of primers used in the

amplification of cDNA. |

Table I

Sequences of primers used in the

amplification of cDNA.

| Primers | Sequences |

|---|

| iNOS | Forward,

5'-TTGTGCATCGACCTAGGCTG GAA-3' |

| | Reverse,

5'-GACCTTTCGCATTAGCATGGA AGC-3' |

| IL-1β | Forward,

5'-GGCAGGCAGTATCACTCATT-3' |

| | Reverse,

5'-CCCAAGGCCACAGGTATTT-3' |

| IL-6 | Forward,

5'-GAGGATACCACTCCCAACAG ACC-3' |

| | Reverse,

5'-AAGTGCATCATCGTTGTTCAT ACA-3' |

| TNF-α | Forward,

5'-TGGAACTGGCAGAAGAGGCA-3' |

| | Reverse,

5'-TGCTCCTCCACTTGGTGGTT-3' |

| GAPDH | Forward,

5'-GGACTGTGGTCATGAGCCCTT CCA-3' |

| | Reverse,

5'-ACTCACGGCAAATTCAACGG CAC-3' |

Western blot analysis

Under differentiation, 3T3-L1 cells were treated

with CF for D0-D8, D0-D2, D0-D4 or D8-D10. The concentration of CF

used in the experiments ranged from 100 to 200 µg/ml in the

dose-dependent studies, while it was set at 200 µg/ml in all other

cases. RAW264.7 cells were treated with CF (200 µg/ml) for 1-6 h in

the absence of TAK (5 µM) or were treated with CF (200 µg/ml) for 3

h in the presence of TAK (5 µM) at 37˚C. After washing with

phosphate-buffered saline, proteins were extracted from RAW264.7

and 3T3-L1 cells using a radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer

(cat. no. BP-115DG; Boston BioProducts, Inc.). The resulting

lysates were centrifuged at 4˚C and 25,200 x g for 30 min. Protein

concentrations were quantified using the bicinchoninic acid assay

kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). For electrophoresis, 30 µg of

protein from each sample was loaded per well, resolved via 10%

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and

transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h at room

temperature and incubated overnight with primary antibodies in a 5%

bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution (1:1,000 dilution) at 4˚C.

Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with 5% BSA solution

with secondary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution) for 1 h at room

temperature. An ECL Select™ Western Blotting Detection Reagent

(cat. no. RPN2232; Cytiva) was then added to visualize the

horseradish peroxidase activity. Protein bands were visualized

using the LI-COR C-DiGit Blot Scanner (LI-COR Biosciences) and

quantitatively analyzed using UN-SCAN-IT gel software version 5.1

(Silk Scientific, Inc.). Actin was used as a loading control for

normalization in western blot analysis.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated at least three times.

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism v.5.0

(GraphPad; Dotmatics), and data are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation. All data were analyzed using one-way analysis

of variance, followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test. P#x003C;0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

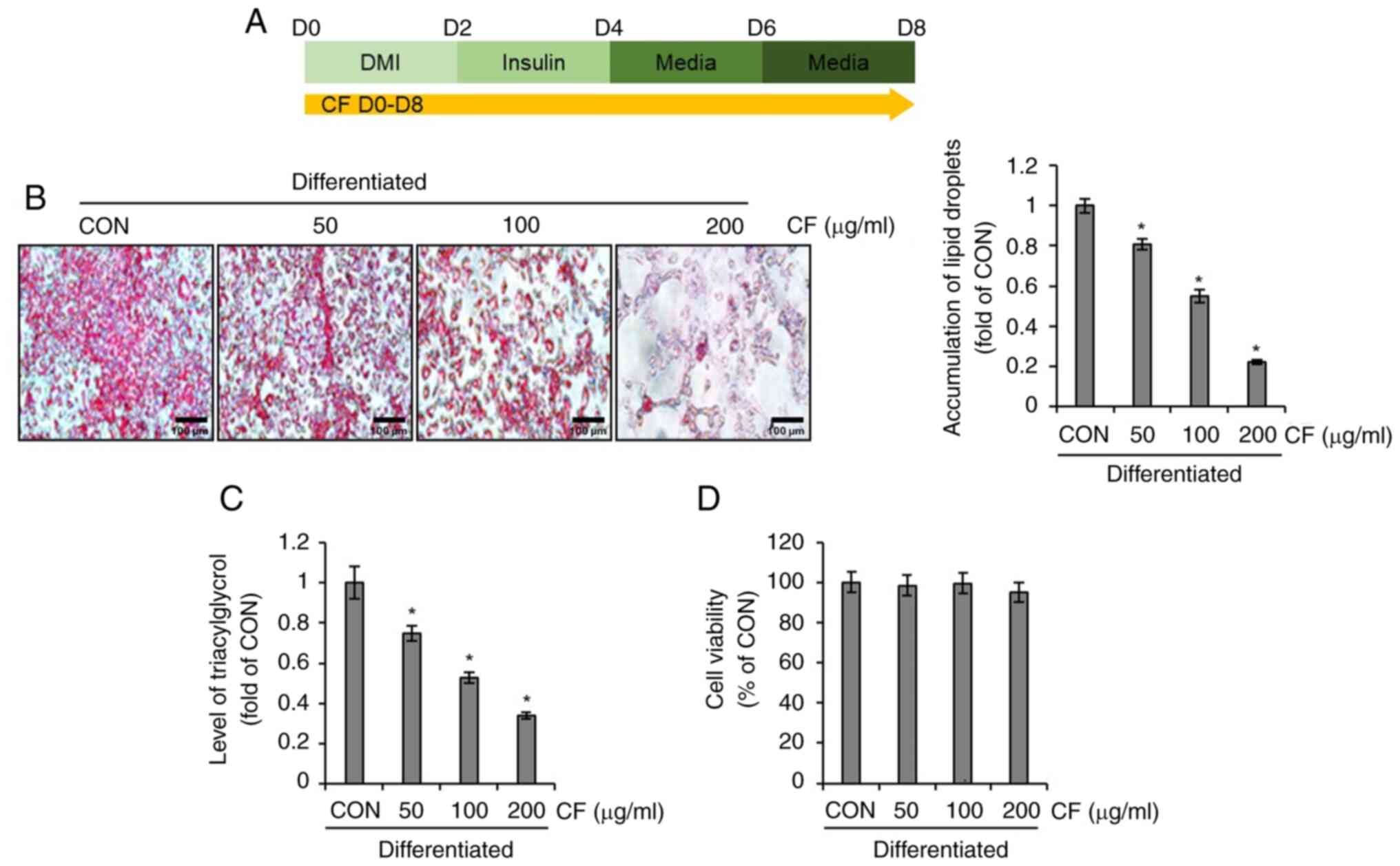

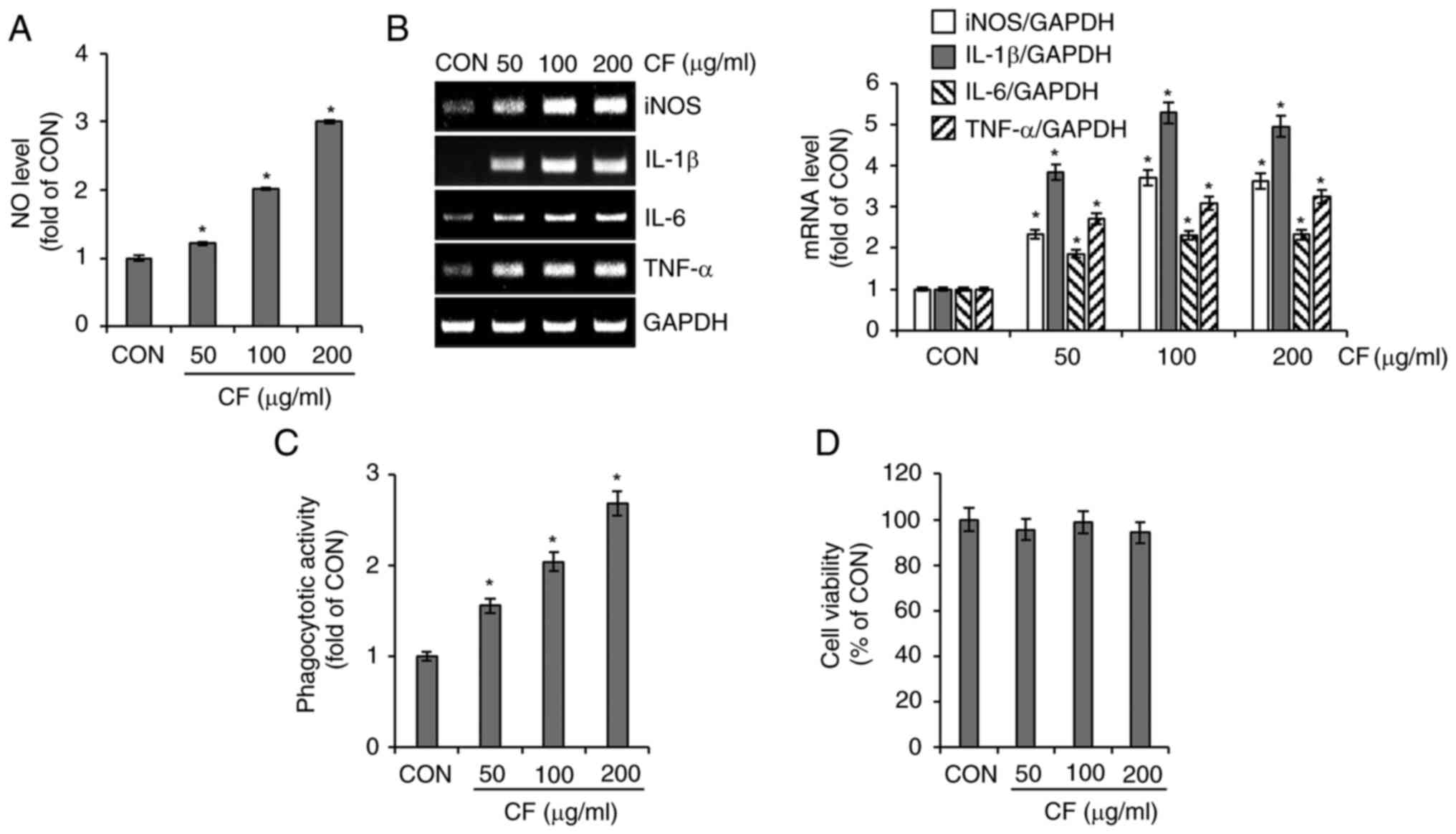

Effect of CF on lipid droplet

accumulation in 3T3-L1 cells

To investigate whether CF inhibits lipid droplet

accumulation in differentiated 3T3-L1 cells, the differentiation of

3T3-L1 cells was induced using DMI and insulin while administering

CF from D0 to D8. Subsequently, the extent of lipid formation and

triglyceride accumulation was analyzed (Fig. 1A). As illustrated in Fig. 1B and C, CF significantly reduced the

accumulation of lipid droplets and triglycerides in differentiated

3T3-L1 cells. To ascertain whether the inhibition of lipid droplets

and triglyceride accumulation mediated by CF is due to its

cytotoxic effects on 3T3-L1 cells, the impact of CF on cellular

viability was evaluated. CF exerted no detrimental effect on 3T3-L1

cell survival (Fig. 1D).

| Figure 1Effect of CF on the accumulation of

lipid droplets and triacylglycerol in 3T3-L1 cells. CF was

administered to 3T3-L1 cells undergoing differentiation induced by

DMI and insulin, from D0 to D8. Subsequently, the extent of lipid

accumulation, the content of triacylglycerol and cell viability

were measured. (A) Experimental design. (B) Oil Red O staining

(magnification, x400), (C) triacylglycerol content and (D) cell

viability in CF-treated 3T3-L1 cells. *P#x003C;0.05 vs.

CON. CF, Chrysosplenium flagelliferum; DMI, dexamethasone,

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, insulin; D, day; CON, control. |

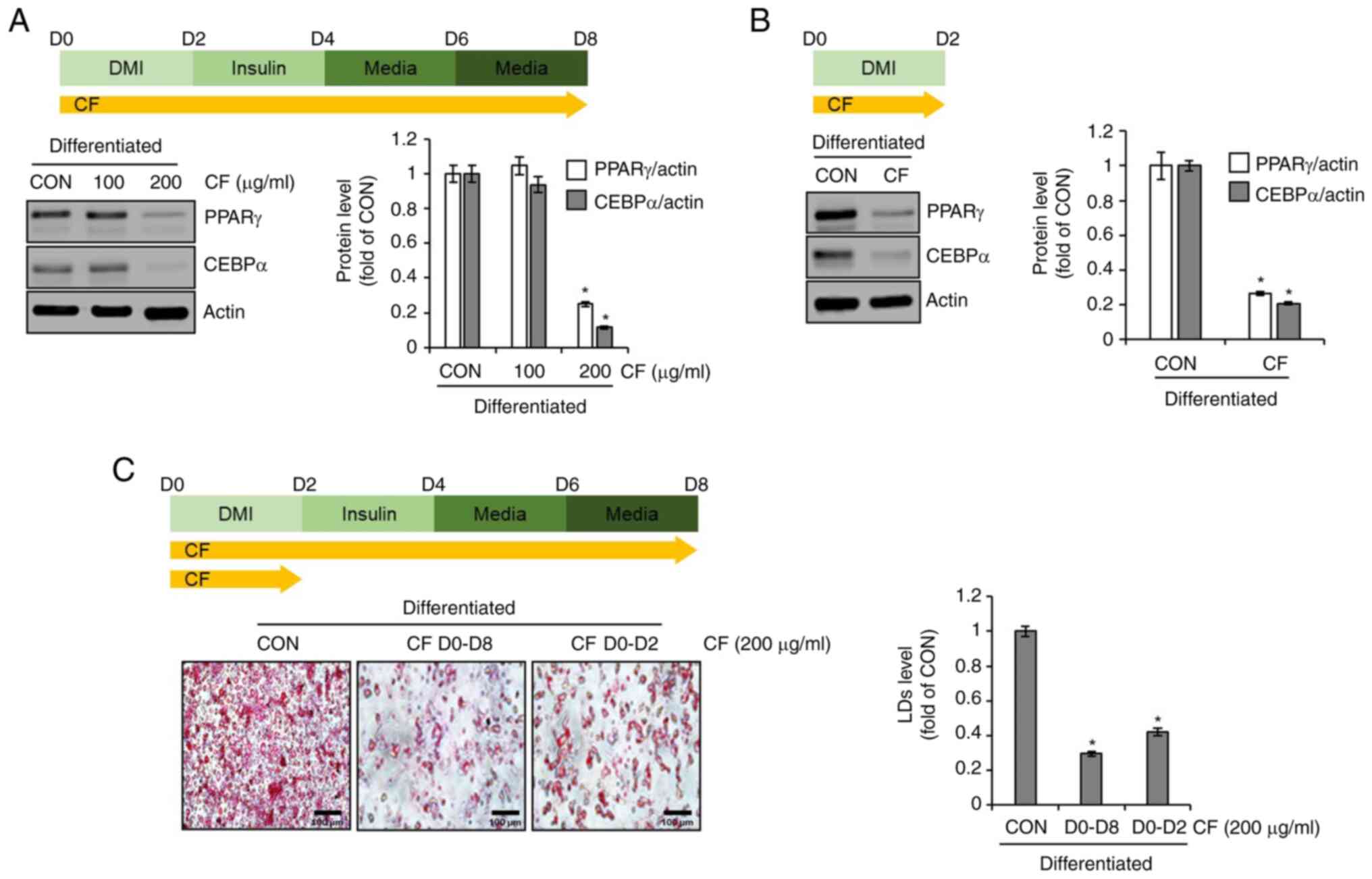

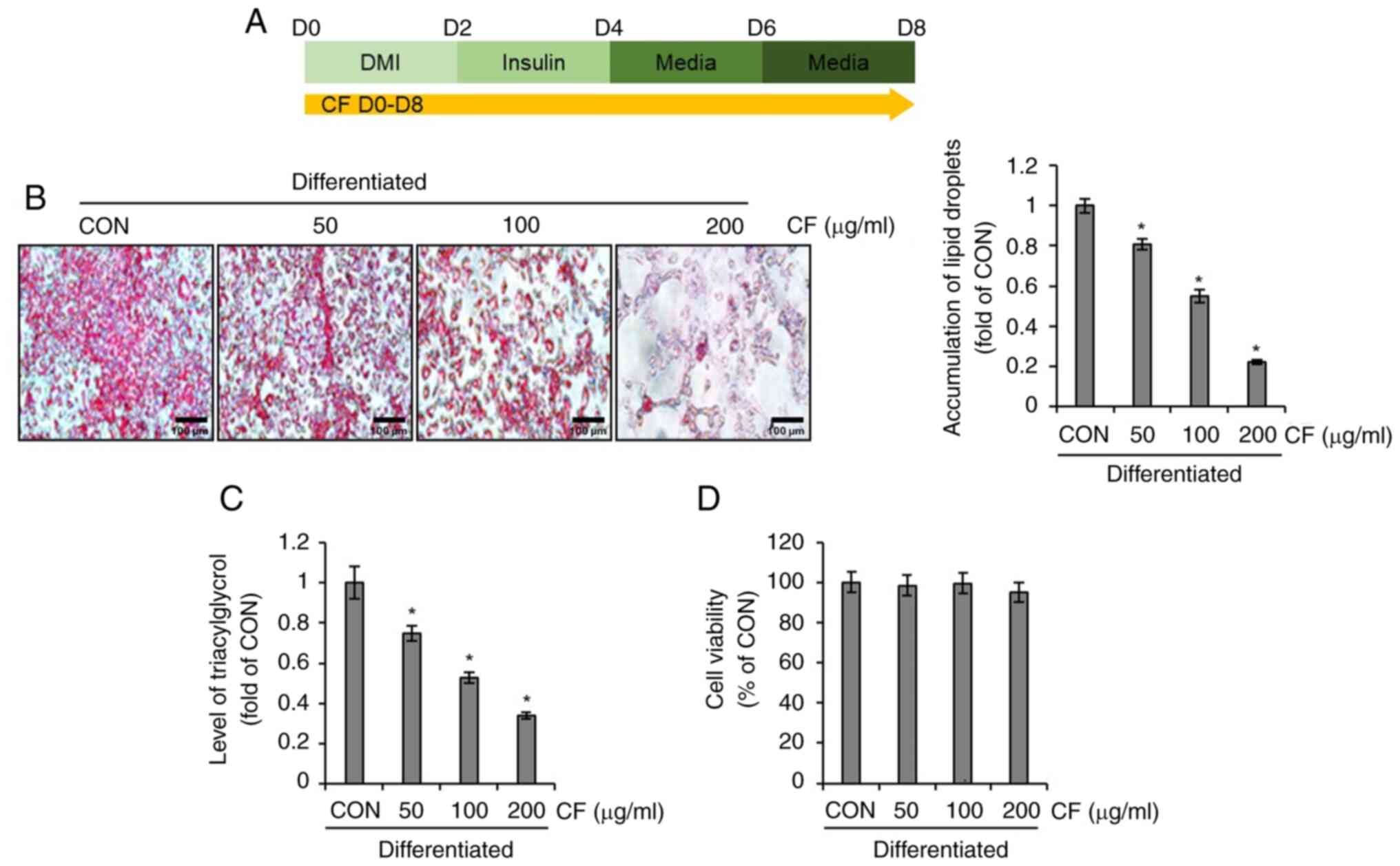

Effect of CF on the adipogenic

differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells

To evaluate whether CF inhibits adipogenic

differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells, differentiation was induced by the

use of DMI and insulin while administering CF from D0 to D8.

Subsequently, western blot analysis was conducted to determine the

expression levels of adipogenic differentiation-related molecules,

PPARγ and CEBPα. At 100 µg/ml, CF did not decrease the protein

levels of PPARγ and CEBPα. However, at 200 µg/ml, CF significantly

reduced the protein levels of PPARγ and CEBPα (Fig. 2A). Considering the necessity of

PPARγ and CEBPα for the differentiation of preadipocytes into

adipocytes, which is marked by the accumulation of lipid droplets

(11,12), it was investigated whether CF

reduces the protein levels of PPARγ and CEBPα during this critical

differentiation stage. First, the differentiation of preadipocytes

into adipocytes was induced using DMI while administering CF from

D0 to D2. Subsequently, western blot analysis was conducted to

assess the alterations in the protein levels of PPARγ and CEBPα

induced by CF. CF significantly reduced the protein levels of PPARγ

and CEBPα during the differentiation from preadipocytes to

adipocytes (Fig. 2B). To determine

whether the inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation to

adipocytes by CF results in decreased lipid droplet accumulation,

the extent of lipid accumulation was compared after treatment with

CF from D0 to D8 and D0 to D2. As revealed in Fig. 2C, a notable reduction in lipid

accumulation was observed in the 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF from

D0 to D2 or from D0 to D8. Furthermore, the reduction of the

accumulation in the D0 to D8 group was greater than that in the D0

to D2 group.

| Figure 2Effect of CF on the expression of

adipogenic markers in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) CF was administered to

3T3-L1 cells undergoing differentiation induced by DMI and insulin,

from D0 to D8. Experimental design and western blot analysis of

PPARγ and CEBPα in 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF (D0-D8). (B) CF

(200 µg/ml) was administered to 3T3-L1 cells undergoing

differentiation induced by DMI, from D0 to D2. Experimental design

and western blot analysis of PPARγ and CEBPα in 3T3-L1 cells

treated with CF (D0-D2). (C) CF was administered to 3T3-L1 cells

undergoing differentiation induced by DMI and insulin, from D0 to

D8 or from D0 to D2. Experimental design and Oil Red O staining

(magnification, x400) in 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF (D0-D8 or

D0-D2). *P#x003C;0.05 vs. CON. CF, Chrysosplenium

flagelliferum; D, day; DMI, dexamethasone,

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, insulin; PPARγ, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor gamma; CEBPα,

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α; CON, control; LDs, lipid

droplets. |

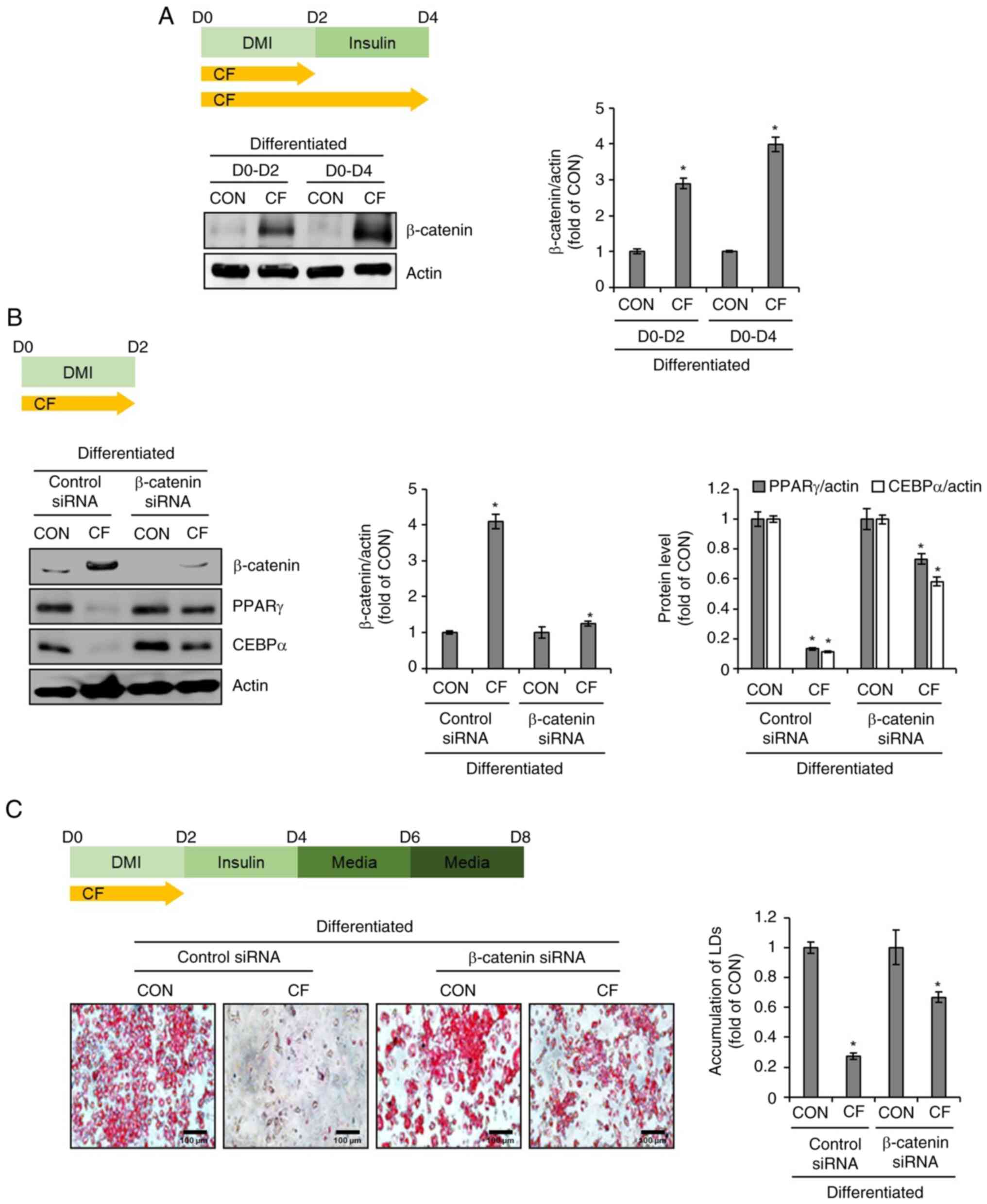

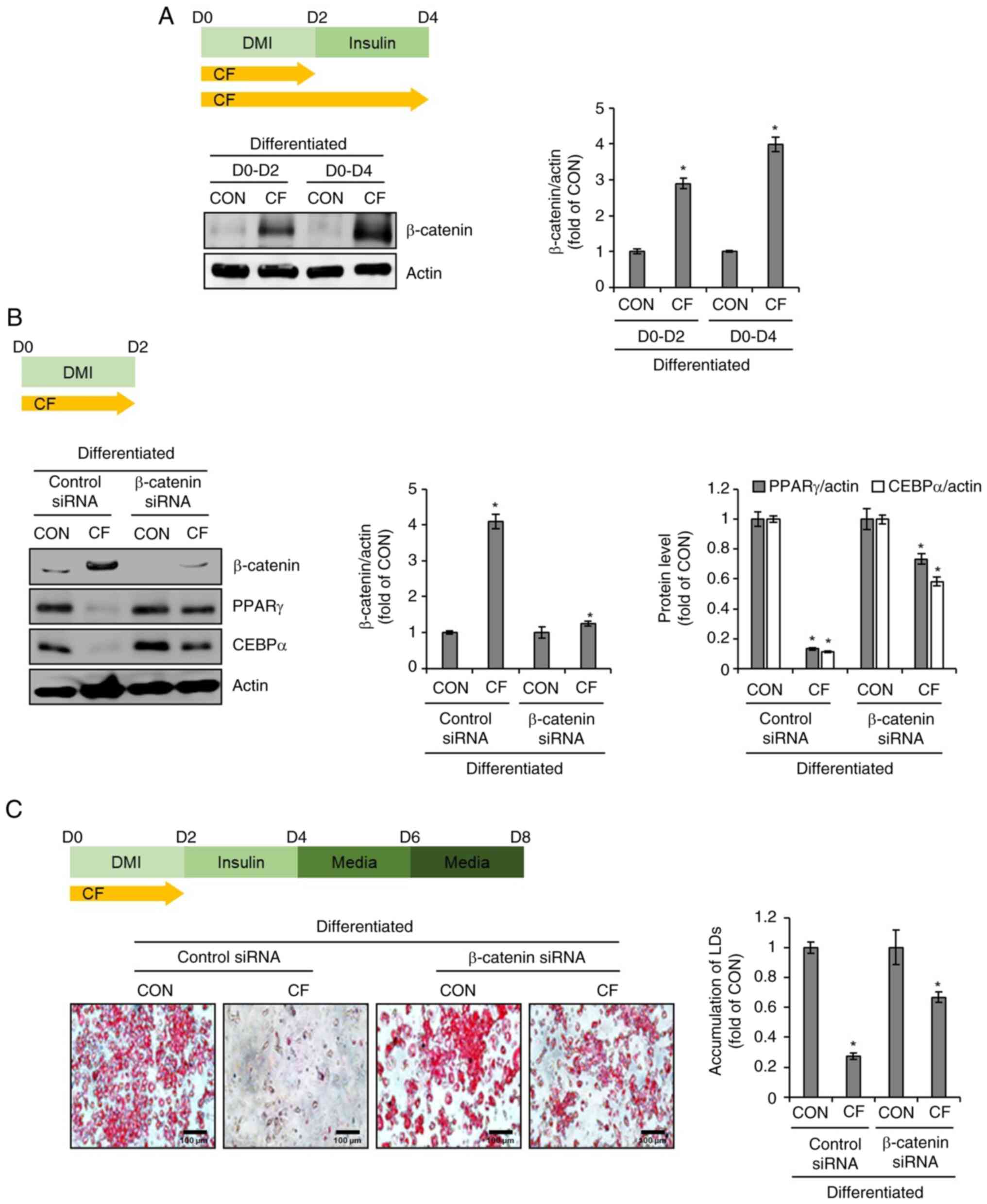

Effect of β-catenin on CF-mediated

inhibition of adipogenic differentiation in 3T3-L1 cells

To investigate the impact of CF on the protein

levels of β-catenin in 3T3-L1 cells, CF was administered from D0 to

D2 and from D0 to D4. Subsequently, western blot analysis was used

to assess the alterations in the protein levels of β-catenin

induced by CF. As illustrated in Fig.

3A, CF increased the protein levels of β-catenin in a

time-dependent manner. To further ascertain the impact of increased

β-catenin protein levels induced by CF on the protein levels of

PPARγ and CEBPα, the changes in PPARγ and CEBPα protein levels were

analyzed in 3T3-L1 cells after β-catenin knockdown using the

β-catenin siRNA. Western blot analysis revealed that CF

significantly reduced the protein levels of PPARγ and CEBPα in

3T3-L1 cells without β-catenin knockdown (Fig. 3B). However, in 3T3-L1 cells with

β-catenin knockdown, CF significantly decreased the protein levels

of PPARγ and CEBPα, but to a more modest degree than the cells

without β-catenin knockdown (Fig.

3B). To further evaluate whether the inhibition of the

CF-mediated decrease in the protein levels of PPARγ and CEBPα due

to β-catenin knockdown affects the CF-mediated suppression of lipid

droplet accumulation, β-catenin-knockdown 3T3-L1 cells were treated

with CF from D0 to D2 and lipid droplet accumulation was analyzed

on D8. As revealed in Fig. 3C,

treatment of cells without β-catenin knockdown with CF resulted in

a notable decrease in lipid droplet accumulation. However, in cells

with β-catenin knockdown, the CF-mediated inhibitory effect on

lipid droplet accumulation was significantly diminished.

| Figure 3Effect of CF on β-catenin expression

in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) CF (200 µg/ml) was administered to 3T3-L1

cells undergoing differentiation induced by DMI and insulin, from

D0 to D2 or D0 to D4. Experimental design and western blot analysis

of β-catenin in 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF (D0-D2 or D0-D4). (B)

CF (200 µg/ml) was administered to β-catenin-knock downed 3T3-L1

cells undergoing differentiation induced by DMI and insulin, from

D0 to D2. Experimental design and western blot analysis of PPARγ

and CEBPα in β-catenin-knockdown 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF

(D0-D2). (C) CF (200 µg/ml) was administered to β-catenin-knockdown

3T3-L1 cells undergoing differentiation induced by DMI and insulin,

from D0 to D2. Experimental design and Oil Red O staining

(magnification, x400) in β-catenin-knockdown 3T3-L1 cells treated

with CF (D0-D2). *P#x003C;0.05 vs. CON. CF,

Chrysosplenium flagelliferum; D, day; DMI, dexamethasone,

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, insulin; CON, control; siRNA, small

interfering RNA; PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

gamma; CEBPα, CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α; LDs, lipid

droplets. |

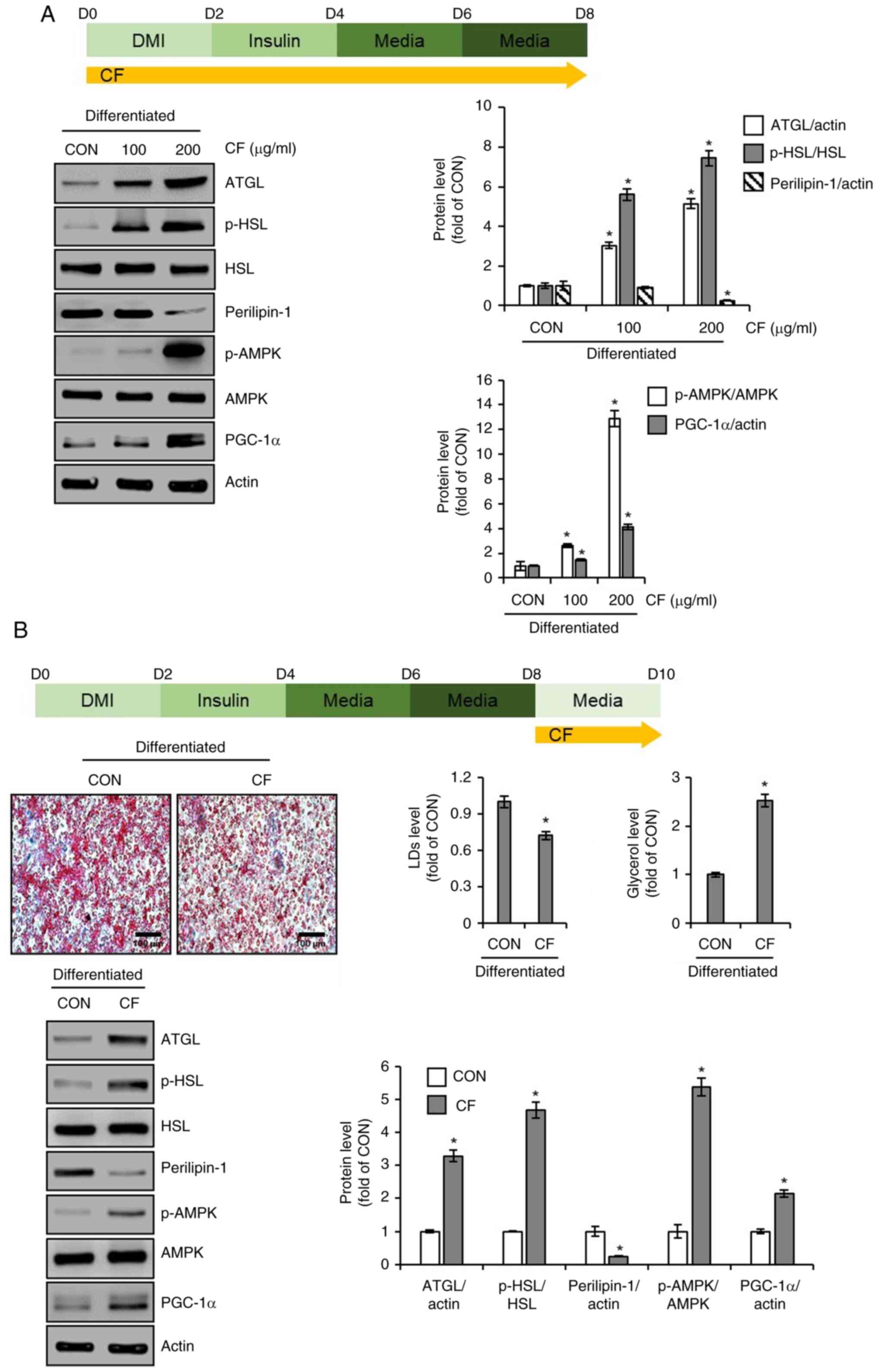

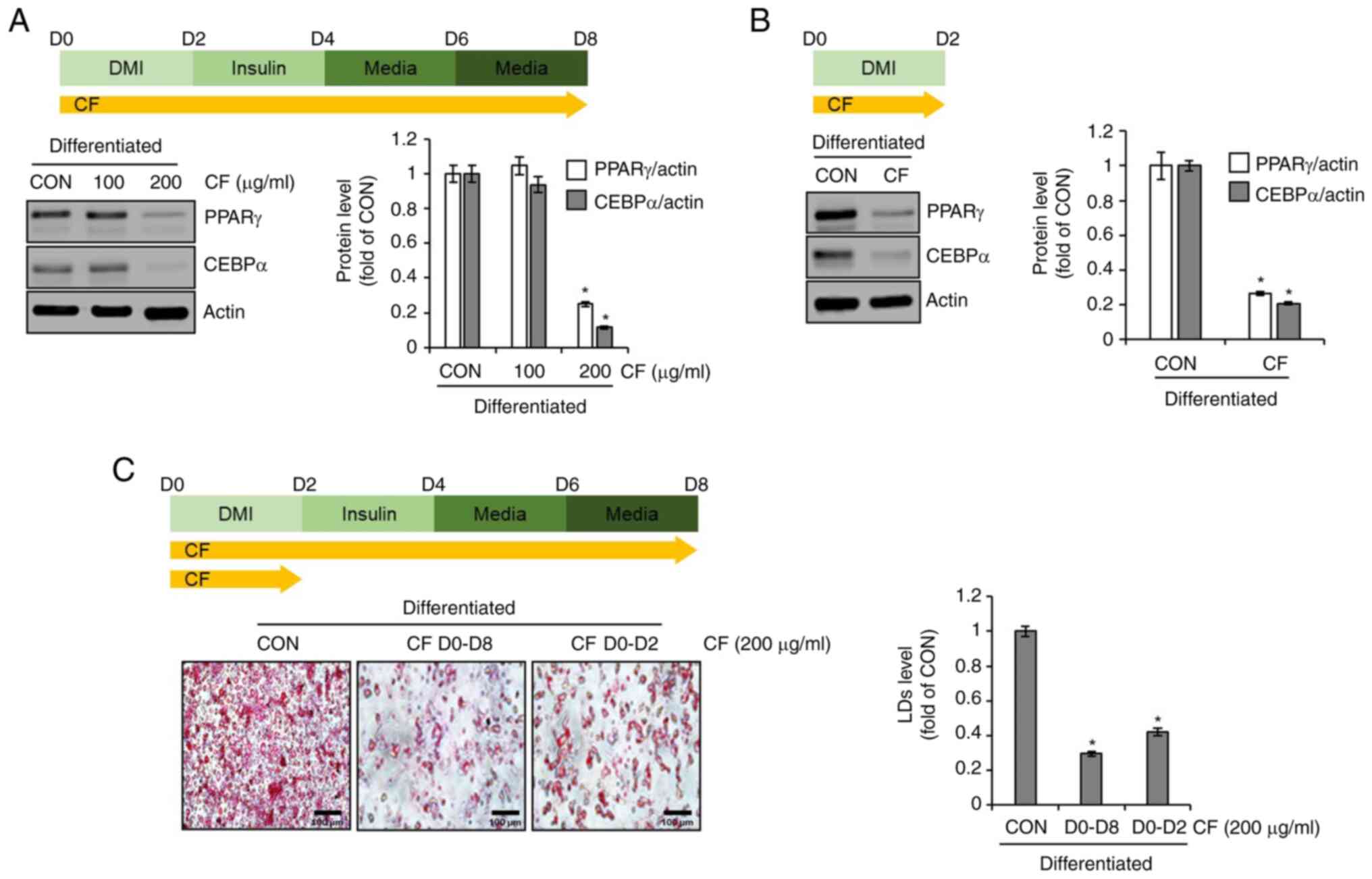

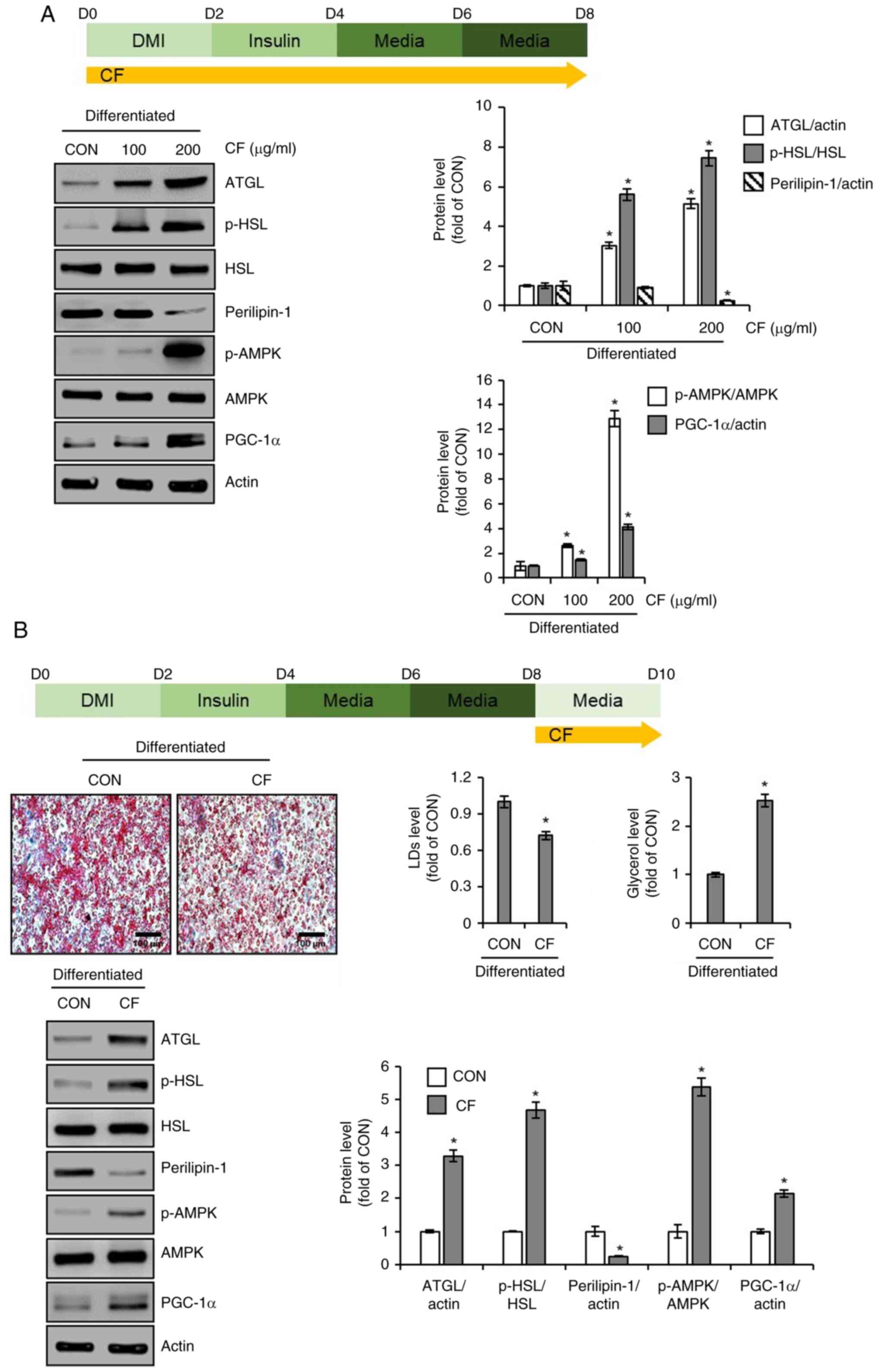

Effects of CF on lipolysis and

thermogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells

To explore the effects of CF on lipolysis and

thermogenesis in 3T3-L1 cells, the cells were treated with CF from

D0 to D8 during the differentiation process. Subsequently, western

blotting was conducted to assess the changes in protein levels of

lipolysis-related molecules, such as ATGL, p-HSL, HSL, perilipin-1

and thermogenesis-related molecules, such as p-AMPK, AMPK and

PGC-1α. As illustrated in Fig. 4A,

3T3-L1 cells treated with CF exhibited a concentration-dependent

increase in ATGL and the ratio of p-HSL to HSL, whereas perilipin-1

levels decreased. Additionally, CF treatment led to an increase in

the ratio of p-AMPK to AMPK and PGC-1α. Thus, to determine whether

the induction of lipolysis and thermogenesis mediated by CF

contributes to the reduction in accumulated lipid droplets, the

cells were treated with CF from D8 to D10, whereas lipid

accumulation was induced without CF treatment from D0 to D8.

Subsequently, the changes in lipid accumulation, glycerol release

and protein levels of molecules related to lipolysis and

thermogenesis were analyzed. As depicted in Fig. 4B, treatment of cells with complete

lipid accumulation with CF resulted in a decrease in accumulated

lipids and an increase in glycerol levels. Furthermore, CF

treatment led to an increase in the levels of lipolysis-related

molecules, such as ATGL and p-HSL, and a decrease in perilipin-1

(Fig. 4B). Additionally, CF

enhanced the levels of thermogenesis-related molecules, including

p-AMPK and PGC-1α (Fig. 4B).

| Figure 4Effect of CF on the expression of

lipolytic and thermogenic markers in 3T3-L1 cells. (A) CF (200

µg/ml) was administered to 3T3-L1 cells undergoing differentiation

induced by DMI and insulin, from D0 to D8. Experimental design and

western blot analysis of ATGL, p-HSL, HSL, perilipin-1, p-AMPK,

AMPK, and PGC-1α in 3T3-L1 cells treated with CF (D0-D8). (B) CF

(200 µg/ml) was administered to differentiated 3T3-L1 by DMI and

insulin, from D8 to D10. Experimental design, Oil Red O staining

(magnification, x400), glycerol level, and western blot analysis of

ATGL, p-HSL, perilipin-1, p-AMPK, and PGC-1α in 3T3-L1 cells

treated with CF (D8-D10). *P#x003C;0.05 vs. CON. CF,

Chrysosplenium flagelliferum; DMI, dexamethasone,

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, insulin; D, day; ATGL, adipose

triglyceride lipase; p-, phosphorylated; HSL, hormone-sensitive

lipase; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; PGC-1α, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α; CON, control. |

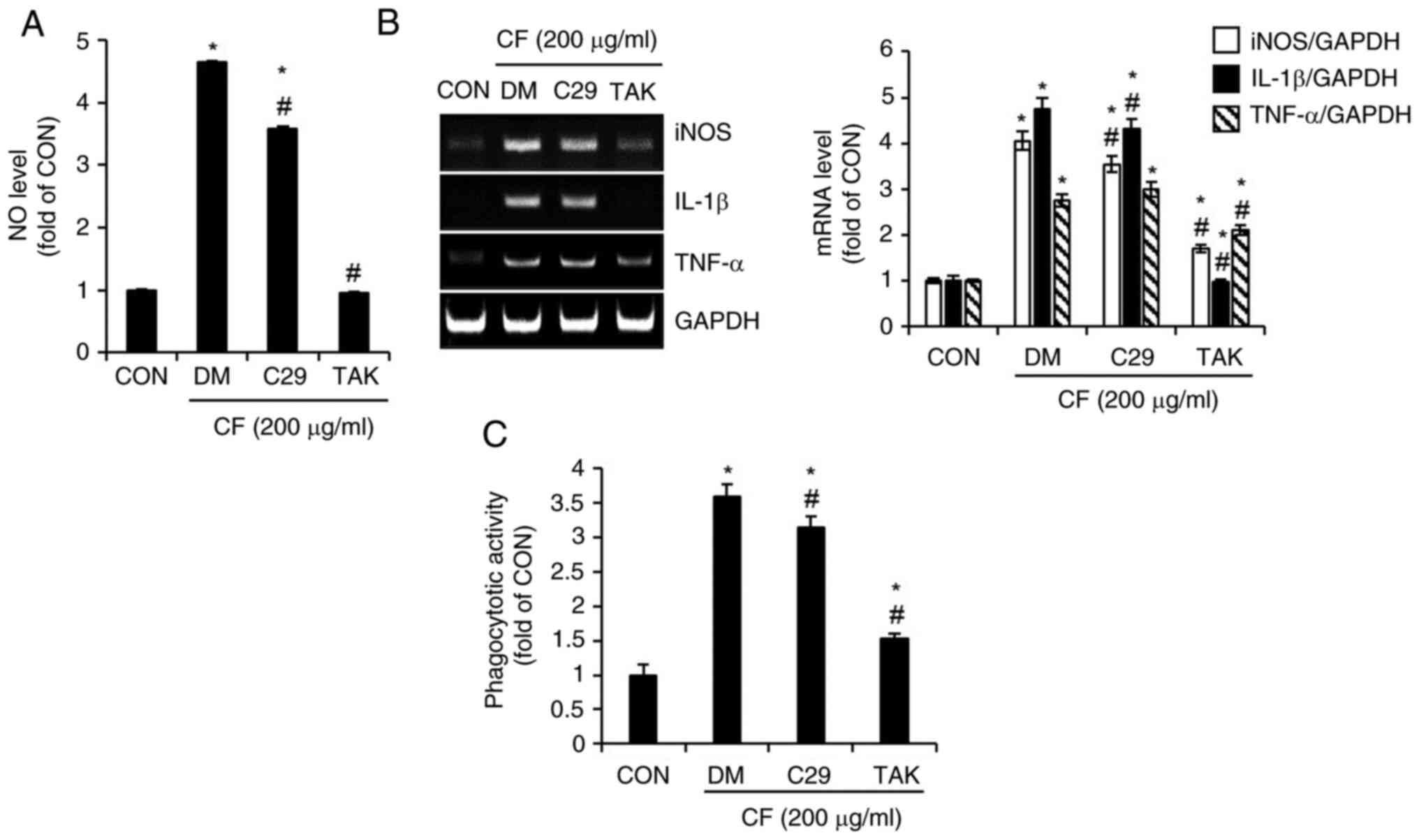

Effect of CF on macrophage activation

in RAW264.7 cells

To investigate the immunostimulatory activity of CF,

its effect on macrophage activation was analyzed in RAW264.7 cells.

As shown in Fig. 5A and B, cells treated with CF exhibited a

significant increase in the secretion of NO and the expression of

iNOS, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α. Furthermore, CF significantly enhanced

the phagocytic activity of RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5C). However, CF did not exhibit

cytotoxic effects on RAW264.7 cells (Fig. 5D).

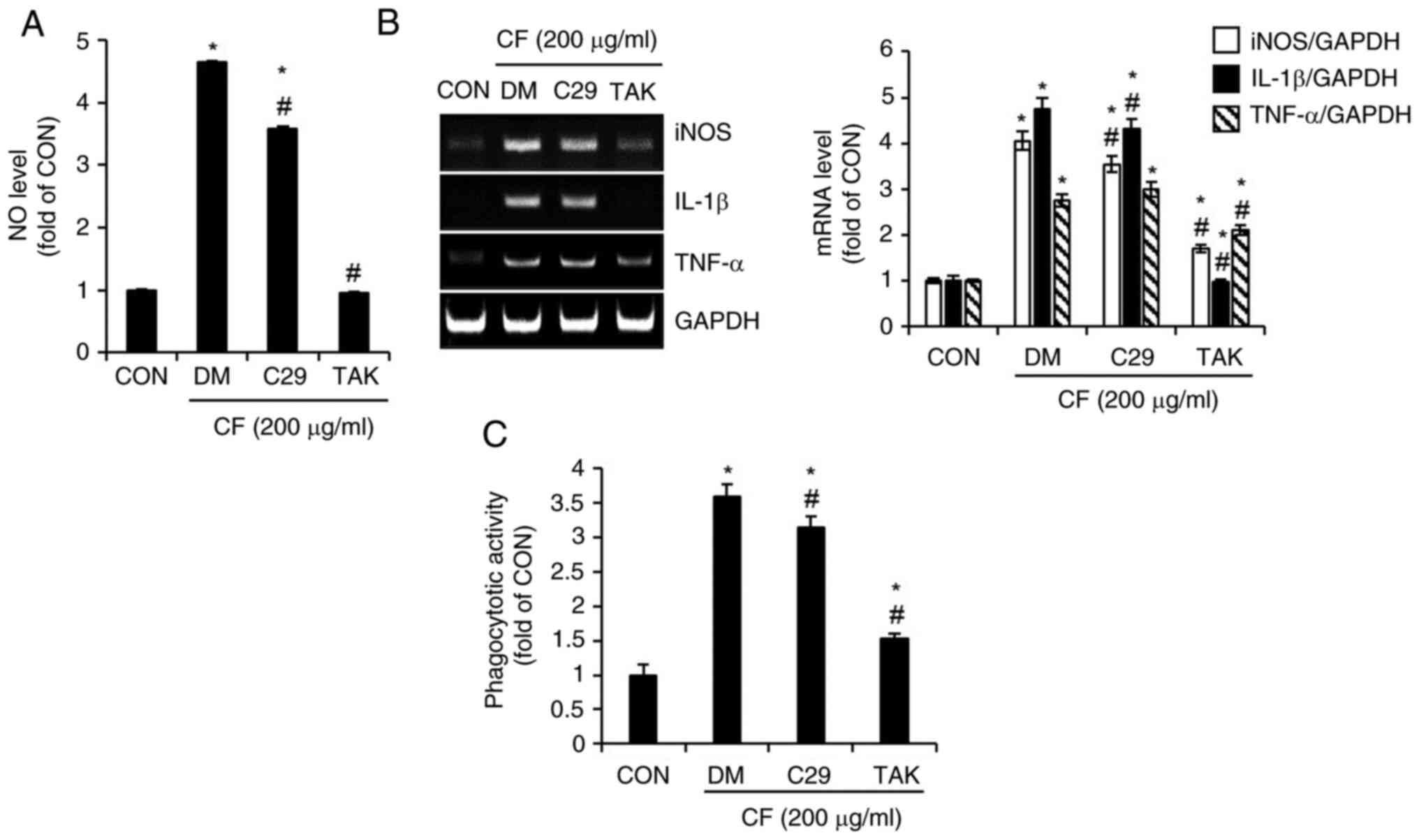

Effects of TLR2 and TLR4 on

CF-mediated activation of RAW264.7 macrophages

To evaluate the impact of TLR2 and TLR4 on

CF-mediated activation of macrophages, RAW264.7 cells were treated

with CF, where TLR2 and TLR4 were inhibited using C29sp16 and TAK,

respectively. Subsequently, the changes in the levels of NO, the

expression of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α, as well as alterations in

phagocytic activity were analyzed. As illustrated in Fig. 6A, compared with untreated cells

(CON group), cells treated solely with CF (DM group) exhibited a

notable increase in NO production, whereas the inhibition of TLR2

by C29 only slightly suppressed CF-mediated NO production. However,

the inhibition of TLR4 by TAK resulted in an almost complete

absence of CF-mediated NO production. The expression of iNOS, IL-1β

and TNF-α mediated by CF was slightly decreased by the inhibition

of TLR2 but significantly reduced by the inhibition of TLR4

(Fig. 6B). Furthermore, it was

observed that the activation of phagocytic activity in RAW264.7

cells mediated by CF was more substantially reduced by the

inhibition of TLR4 than by the inhibition of TLR2 (Fig. 6C).

| Figure 6Effect of TLR2 and TLR4 on

CF-mediated activation of macrophages in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7

cells were pretreated with C29 (TLR2 inhibitor, 100 µM) or TAK

(TLR4 inhibitor, 5 µM) for 2 h and then co-treated with CF (200

µg/ml) for 24 h. (A) The level of NO, (B) reverse transcription PCR

analysis of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α, and (C) phagocytotic activity in

RAW264.7 cells treated with CF for 24 h in the presence of C29 or

TAK. *P#x003C;0.05 vs. CON. #P#x003C;0.05 vs.

DM. TLR, toll-like receptor; CF, Chrysosplenium

flagelliferum; TAK, TAK-242; NO, nitric oxide; iNOS, inducible

nitric oxide synthase; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis

factor-α; CON, control; DM, DMSO group. |

Effects of mitogen-activated protein

kinase (MAPK) and NF-κB signaling pathways on CF-mediated

activation of RAW264.7 macrophages

To investigate the effects of MAPK and NF-κB

signaling pathways on CF-mediated activation of macrophages,

RAW264.7 cells were treated with CF and with the inhibitors of each

signaling pathway. Subsequently, the changes in NO production and

the expression of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α were examined. As

demonstrated in Fig. 7A, the

inhibition of ERK1/2 by PD had no effect on CF-mediated NO

production. However, the inhibition of p38 by SB and the inhibition

of JNK by SP both suppressed CF-mediated NO production, with the

suppression due to JNK inhibition being particularly pronounced.

Therefore, the impact of JNK inhibition by SP on the expression of

iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α mediated by CF was analyzed. The results

revealed that the inhibition of JNK significantly decreased the

CF-mediated expression of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α (Fig. 7B). Furthermore, it was confirmed

that the inhibition of NF-κB by BAY also resulted in a significant

decrease in the CF-mediated production of NO and the expression of

iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α (Fig. 7C).

Thus, it was then investigated whether CF activated the JNK and

NF-κB signaling pathways. The results indicated that CF increases

the phosphorylation of JNK and p65, which are the active forms of

JNK and NF-κB signaling, respectively (Fig. 7D). As the activation of macrophages

mediated by CF primarily occurs via TLR4 stimulation, it was

analyzed whether the activation of JNK and NF-κB by CF is

influenced by TLR4. Inhibition of TLR4 by TAK significantly

suppressed the CF-mediated phosphorylation of JNK and p65 (Fig. 7E).

| Figure 7Effect of MAPK and NF-κB signaling

pathways on CF-mediated activation of macrophages in RAW264.7

cells. (A) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with PD (ERK1/2

inhibitor, 20 µM), SB (p38 inhibitor, 20 µM) or SP (JNK inhibitor,

20 µM) and then co-treated with CF (200 µg/ml) for 24 h. The level

of NO and (B) RT-PCR analysis of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α in RAW264.7

cells treated with CF in the presence of PD, SB or SP. (C) RAW264.7

cells were pretreated with BAY (NF-κB inhibitor, 10 µM), and then

co-treated with CF (200 µg/ml) for 24 h. The level of NO and RT-PCR

analysis of iNOS, IL-1β, and TNF-α in RAW264.7 cells treated with

CF for 24 h in the presence of BAY. (D) RAW264.7 cells were treated

with CF (200 µM) for the indicated time-points. Western blot

analysis of p-JNK, JNK, p-p65 and p65 in RAW264.7 cells treated

with CF. (E) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with TAK (TLR4

inhibitor, 5 µM) for 2 h and the co-treated with CF (200 µM) for 3

h. Western blot analysis of p-JNK, JNK, p-p65, and p65 in RAW264.7

cells treated with CF in the presence of TAK.

*P#x003C;0.05 vs. CON. #P#x003C;0.05 vs. DM.

CF, Chrysosplenium flagelliferum; PD, PD98059; SB, SB203580;

SP, SP600125; NO, nitric oxide; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide

synthase; IL-1β, interleukin-1β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α;

BAY, BAY11-7082; p-, phosphorylated; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase;

TAK, TAK-242; CON, control; DM, DMSO group. |

Discussion

In the human body, excess energy is stored in

adipocytes in the form of lipids via a process that is a hallmark

of obesity (11). Obesity is

characterized by the enlargement of existing adipocytes and

increase in the number of new adipocytes due to preadipocyte

differentiation (11). To

investigate the potential anti-obesity effects of CF, the changes

in lipid accumulation within adipocytes after CF treatment were

examined in the present study. A significant reduction in lipid

accumulation in the adipocytes treated with CF was observed.

However, CF did not exert any adverse effects on adipocyte

viability. These findings suggested the anti-obesity activity of CF

and highlighted its potential as a safe and effective agent to

combat obesity. Lack of a detrimental effect on adipocyte viability

further underscored its suitability as a therapeutic agent for

obesity management. Adipogenesis, differentiation of preadipocytes

into mature adipocytes, plays a key role in increasing the number

of lipid-storing adipocytes (11).

Consequently, adipogenesis inhibition has been used as a molecular

target for the discovery of new anti-obesity agents, underlining

its significance in obesity research and treatment (11). In the present study, to evaluate

the inhibitory effect of CF on adipogenesis, preadipocytes

undergoing differentiation into adipocytes were treated with CF.

Post-treatment, western blot analysis was employed to assess the

expression changes of PPARγ and C/EBPα, key regulators instrumental

in the activation of adipogenesis (12). PPARγ has been demonstrated to be

essential for both adipogenesis and the maintenance of adipocyte

phenotype, as evidenced through in vivo and ex vivo

studies (13-16).

Similarly, C/EBPα has been proven to be crucial for the

differentiation and maintenance of white adipose tissue, also

validated through in vivo and ex vivo experiments

(17-20).

These existing reports collectively indicate that the suppression

of PPARγ and C/EBPα expression can effectively inhibit

adipogenesis. In the present study, it was revealed that CF

inhibits the expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα, which in turn leads to

the suppression of lipid accumulation within adipocytes. These

results demonstrate that the anti-obesity activity of CF may

primarily operate through the suppression of adipogenesis, mediated

by the inhibition of PPARγ and C/EBPα expression. Activation of the

Wnt signaling pathway inhibits the expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα,

thereby maintaining preadipocytes in an undifferentiated state and

suppressing adipogenesis. Conversely, inhibition of Wnt signaling

induces adipogenic differentiation (21). During adipogenic differentiation,

the degradation of β-catenin leads to an increase in the expression

of PPARγ and C/EBPα. However, an elevation in β-catenin levels,

even under conditions favoring adipogenic differentiation, results

in decreased expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα, thereby inhibiting

adipogenesis (22). Therefore, to

determine whether the CF-induced decrease in PPARγ and C/EBPα is

associated with Wnt signaling, adipocytes undergoing adipogenic

differentiation were treated with CF. Subsequently, western blot

analysis was conducted to assess the changes in the levels of

β-catenin protein. The results revealed that CF treatment led to an

increase in the levels of β-catenin protein. Furthermore, in

adipocytes where β-catenin was knocked down by siRNA, the

CF-mediated decrease in PPARγ and C/EBPα was notably attenuated.

This observation also led to the discovery that such β-catenin

knockdown by siRNA consequently reduced the CF-mediated inhibition

of lipid accumulation. These results indicated that CF inhibits

adipogenesis through the activation of Wnt signaling, leading to

the suppression of PPARγ and C/EBPα expression. However, a

limitation of this study is the inability to ascertain whether the

CF-mediated increase in β-catenin protein levels is due to the

inhibition of proteasomal degradation or a result of

transcriptional activation. Consequently, further mechanistic

studies are required to elucidate the specific pathway involved in

the CF-mediated elevation of β-catenin protein levels. It has been

reported that the most ideal mechanism for anti-obesity treatments

encompasses the augmentation of lipolysis and the enhancement of

energy expenditure (23).

Lipolysis is a catabolic reaction in which triacylglycerol stored

in adipocytes is hydrolyzed to glycerol and fatty acids (24). During lipolysis, triacylglycerol is

progressively hydrolyzed to diacylglycerol, monoacylglycerol, and

glycerol by a series of lipolytic enzymes (25). ATGL catalyzes the hydrolysis of

triacylglycerol to diacylglycerol, which is subsequently hydrolyzed

to monoacylglycerol by HSL (26).

As ATGL and HSL account for >90% of the triacylglycerol

hydrolysis (26), they are

considered pivotal indicators of lipolysis (27-29).

Furthermore, perilipin-1, which encircles lipid droplets within

adipocytes, has been revealed to play a role in lipolysis (30,31).

Perilipin-1 was shown to inhibit lipolysis while concurrently

promoting lipid synthesis and lipid droplet formation (32). Furthermore, perilipin-1 was

demonstrated to lead to increased lipolysis, resulting in a

reduction in the size of lipid droplets within adipocytes (33). In the present study, CF increased

the protein levels of ATGL and p-HSL in adipocytes, while

concurrently reducing the protein levels of perilipin-1. Upon

treatment of lipid-laden adipocytes with CF, a reduction in the

number of lipid droplets and an increase in glycerol content were

observed. These findings indicated that CF can induce lipolysis,

suggesting that its lipolytic action may contribute to the

inhibition of lipid accumulation. Lipolysis in white adipose tissue

is essential for thermogenesis (34). Furthermore, it has been reported

that the browning of white adipose tissue can facilitate

thermogenesis, thereby promoting energy expenditure (35). AMPK, a critical metabolic sensor

and regulator of energy balance, induces browning of white adipose

tissue (36). PGC-1α, known as a

master transcriptional coactivator in mitochondrial biogenesis, is

widely used as a key indicator for the differentiation of white

adipose tissue into brown adipocytes (37). In the present study, it was

confirmed that CF increases the protein levels of p-AMPK and PGC-1α

in adipocytes. Although the current study did not analyze the

impact of CF on the protein levels of uncoupling protein-1 and PR

domain containing 16, closely associated with the browning of white

adipocytes, which presents a limitation, the observed increase in

the protein levels of p-AMPK and PGC-1α by CF can be considered

evidence suggesting that CF may induce the browning of white

adipocytes.

Macrophages maintain homeostasis by defending

against foreign pathogens, processing internal waste and

facilitating tissue repair (38).

When foreign pathogens invade the human body, activated

macrophages, as a key component of the innate immune system,

phagocytize these invaders and secrete pro-inflammatory mediators,

such as NO, iNOS, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (38). Furthermore, macrophages possess the

ability to present antigens to adaptive immune cells, such as T and

B cells, and pro-inflammatory mediators secreted by macrophages

contribute to the activation of these T and B cells (39). In conclusion, these studies may

serve as evidence suggesting that the activation of macrophages can

play a positive role in both innate and adaptive immune responses.

In the present study, it was confirmed that CF enhances the

production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as NO, iNOS, IL-1β,

IL-6 and TNF-α, in macrophages and activates their phagocytic

activity. These findings provided evidence that CF induces

macrophage activation. Although this study did not elucidate the

relationship between CF-mediated activation of macrophages and

adaptive immune cells, such as T and B cells, which is a

limitation, existing research that macrophage activation can induce

T and B cell activation (39)

suggests that CF may contribute to the activation of these cells

through its role in macrophage activation. The inflammatory

response of macrophages to eliminate foreign pathogens initiates

upon the recognition of these pathogens by macrophages (38). Macrophages recognize

pathogen-associated molecular patterns of foreign pathogens via

pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) (38). Among the various PRRs in

macrophages, TLRs play a pivotal role in the recognition of foreign

pathogens (38). TLR2 and TLR4

play crucial roles in the elimination of foreign pathogens by

inducing the production of proinflammatory mediators and activating

phagocytic activity in macrophages (40). In the present study, it was

observed that inhibition of TLR4 in cells resulted in a significant

decrease in CF-mediated pro-inflammatory mediator production and

phagocytic activation compared with cells with inhibition of TLR2.

Although the present study did not fully analyze the relationship

between CF-mediated macrophage activation and all PRRs present in

macrophages, which is a limitation, the findings suggested that

TLR4 plays a central role in the activation of macrophages mediated

by CF. TLR4-mediated macrophage activation involves the signaling

pathways of NF-κB and MAPK (41).

In the current study, it was observed that the inhibition of JNK, a

component of the MAPK signaling pathway, and NF-κB notably reduced

the production of CF-mediated pro-inflammatory mediators, and the

inhibition of TLR4 suppressed CF-mediated activation of JNK and

NF-κB. These findings may serve as evidence that CF-mediated

macrophage activation can be attributed to the activation of the

TLR4-dependent JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

In the present study, it was found that CF inhibited

adipogenesis and induced lipolysis and thermogenesis, thereby

suppressing excessive lipid accumulation in adipocytes.

Additionally, CF stimulated macrophage activation via

TLR4-dependent activation of the JNK and NF-κB signaling pathways.

These findings indicated that CF exerts anti-obesity and

immunostimulatory effects. Combined with the previously reported

antioxidant and antimicrobial effects, the anti-obesity and

immunostimulatory effects demonstrated in the present study expand

the known pharmacological activity spectrum of CF. However, this

study primarily relied on in vitro cellular assays and

lacked in vivo experiments using animal models, representing

a major limitation. Therefore, future in vivo studies using

animal models are necessary to verify these findings and facilitate

the development of new functional materials for the anti-obesity

and immunostimulatory applications of CF.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by the National Institute

of Forest Science, Korea (grant no. FP0802-2023-01-2023), the

R&D Program for Forest Science Technology (grant no.

RS-2024-00405196) provided by the Korea Forest Service (Korea

Forestry Promotion Institute, Seoul, Korea).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JWC, GHP, HJC, JWL, HYK and MYC performed cell-based

experiments and analyzed the data. JWC and GHP wrote the

manuscript. JBJ designed the experiments and wrote and edited the

manuscript. JWC, GHP, HJC, JWL, HYK, MYC and JBJ confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All the authors have read and

approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jin H, Han H, Song G, Oh HJ and Lee BY:

Anti-obesity effects of GABA in C57BL/6J mice with high-fat

diet-induced obesity and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Int J Mol Sci.

25(995)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kang SA and Yu HS: Anti-obesity effects by

parasitic nematode (Trichinella spiralis) total lysates.

Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 13(1285584)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Shi Q, Wang Y, Hao Q, Vandvik PO, Guyatt

G, Li J, Chen Z, Xu S, Shen Y, Ge L, et al: Pharmacotherapy for

adults with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and network

meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 399:259–269.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Huttunen R and Syrjänen J: Obesity and the

outcome of infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 10:442–443.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Muscogiuri G, Pugliese G, Laudisio D,

Castellucci B, Barrea L, Savastano S and Colao A: The impact of

obesity on immune response to infection: Plausible mechanisms and

outcomes. Obes Rev. 22(e13216)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nour TY and Altintaş KH: Effect of the

COVID-19 pandemic on obesity and its risk factors: A systematic

review. BMC Public Health. 23(1018)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tak YJ and Lee SY: Anti-obesity drugs:

Long-term efficacy and safety: An updated review. World J Mens

Health. 39:208–221. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Sun NN, Wu TY and Chau CF: Natural dietary

and herbal products in anti-obesity treatment. Molecules.

21(1351)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yan WJ, Yang TG, Liao R, Wu ZH, Qin R and

Liu H: Complete chloroplast genome sequence of Chrysosplenium

macrophyllum and Chrysosplenium flagelliferum

(Saxifragaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5:2040–2041.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Choi HA, Ahn SO, Lim HD and Kim GJ: Growth

suppression of a gingivitis and skin pathogen Cutibacterium

(Propionibacterium) acnes by medicinal plant extracts.

Antibiotics (Basel). 10(1092)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Jakab J, Miškić B, Mikšić S, Juranić B,

Ćosić V, Schwarz D and Včev A: Adipogenesis as a potential

anti-obesity target: A review of pharmacological treatment and

natural products. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 14:67–83.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Madsen MS, Siersbaek R, Boergesen M,

Nielsen R and Mandrup S: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

γ and C/EBPα synergistically activate key metabolic adipocyte genes

by assisted loading. Mol Cell Biol. 34:939–954. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Barak Y, Nelson M, Ong E, Jones Y,

Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien K, Koder A and Evans R: PPAR gamma is required

for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell.

4:585–595. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Rosen E, Sarraf P, Troy A, Bradwin G,

Moore K, Milstone D, Spiegelman B and Mortensen R: PPAR gamma is

required for the differentiation of adipose tissue in vivo and in

vitro. Mol Cell. 4:611–617. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Whitesall SE,

D'Alecy LG, Duquaine DC, Brosius FC III, Gonzalez F, Vinson C,

Pierre MA, Milstone DS and Mortensen RM: Hypotension,

lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized

PPARgamma-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. J Clin

Invest. 117:812–822. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Imai T, Takakuwa R, Marchand S, Dentz E,

Bornert JM, Messaddeq N, Wendling O, Mark M, Desvergne B, Wahli W,

et al: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma is required

in mature white and brown adipocytes for their survival in the

mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:4543–4547. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Linhart HG, Ishimura-Oka K, DeMayo F, Kibe

T, Repka D, Poindexter B, Bick RJ and Darlington GJ: C/EBPalpha is

required for differentiation of white, but not brown, adipose

tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 98:12532–12537. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Wang N, Finegold M, Bradley A, Ou C,

Abdelsayed S, Wilde M, Taylor L, Wilson D and Darlington G:

Impaired energy homeostasis in C/EBP alpha knockout mice. Science.

269:1108–1112. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Yang J, Croniger C, Lekstrom-Himes J,

Zhang P, Fenyus M, Tenen D, Darlington G and Hanson R: Metabolic

response of mice to a postnatal ablation of CCAAT/enhancer-binding

protein alpha. J Biol Chem. 280:38689–38699. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rosen E, Hsu CH, Wang X, Sakai S, Freeman

M, Gonzalez F and Spiegelman B: C/EBPalpha induces adipogenesis

through PPARgamma: A unified pathway. Genes Dev. 16:22–26.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Rosen ED and MacDougald OA: Adipocyte

differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

7:885–896. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chang E and Kim CY: Natural products and

obesity: A focus on the regulation of mitotic clonal expansion

during adipogenesis. Molecules. 24(1157)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yang XD, Ge XC, Jiang SY and Yang YY:

Potential lipolytic regulators derived from natural products as

effective approaches to treat obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

13(1000739)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Saponaro C, Gaggini M, Carli F and

Gastaldelli A: The subtle balance between lipolysis and

lipogenesis: A critical point in metabolic homeostasis. Nutrients.

7:9453–9474. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Song Z, Xiaoli AM and Yang F: Regulation

and metabolic significance of de novo lipogenesis in adipose

tissues. Nutrients. 10(1383)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Brejchova K, Radner FPW, Balas L,

Paluchova V, Cajka T, Chodounska H, Kudova E, Schratter M,

Schreiber R, Durand T, et al: Distinct roles of adipose

triglyceride lipase and hormone-sensitive lipase in the catabolism

of triacylglycerol estolides. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

118(e2020999118)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mottillo EP and Granneman JG:

Intracellular fatty acids suppress β-adrenergic induction of

PKA-targeted gene expression in white adipocytes. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 301:E122–E131. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Chakrabarti P, English T, Karki S, Qiang

L, Tao R, Kim J, Luo Z, Farmer SR and Kandror KV: SIRT1 controls

lipolysis in adipocytes via FOXO1-mediated expression of ATGL. J

Lipid Res. 52:1693–1701. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Barbato DL, Aquilano K, Baldelli S,

Cannata SM, Bernardini S, Rotilio G and Ciriolo MR: Proline

oxidase-adipose triglyceride lipase pathway restrains adipose cell

death and tissue inflammation. Cell Death Differ. 21:113–123.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Granneman JG, Moore HP, Krishnamoorthy R

and Rathod M: Perilipin controls lipolysis by regulating the

interactions of AB-hydrolase containing 5 (Abhd5) and adipose

triglyceride lipase (Atgl). J Biol Chem. 284:34538–34544.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Contreras GA, Strieder-Barboza C and

Raphael W: Adipose tissue lipolysis and remodeling during the

transition period of dairy cows. J Anim Sci Biotechnol.

8(41)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Straub BK, Stoeffel P, Heid H, Zimbelmann

R and Schirmacher P: Differential pattern of lipid

droplet-associated proteins and de novo perilipin expression in

hepatocyte teratogenesis. Hepatology. 47:1936–1946. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Temprano A, Sembongi H, Han GS, Sebastián

D, Capellades J, Moreno C, Guardiola J, Wabitsch M, Richart C,

Yanes O, et al: Redundant roles of the phosphatidate phosphatase

family in triacylglycerol synthesis in human adipocytes.

Diabetologia. 59:1985–1994. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Shin H, Shi H, Xue B and Yu L: What

activates thermogenesis when lipid droplet lipolysis is absent in

brown adipocytes? Adipocyte. 7:143–147. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Nguyen VTT, Vu VV and Pham PV: Brown

adipocyte and browning thermogenesis: Metabolic crosstalk beyond

mitochondrial limits and physiological impacts. Adipocytes.

12(2237164)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Van der Vaart JI, Boon MR and Houtkooper

RH: The role of AMPK signaling in brown adipose tissue activation.

Cells. 10(1122)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Gulyaeva O, Dempersmier J and Sul HS:

Genetic and epigenetic control of adipose development. Biochim

Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 1864:3–12. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Hirayama D, Iida T and Nakase H: The

phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and

tissue homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 19(92)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Navegantes KC, de Souza Gomes R, Pereira

PAT, Czaikoski PG, Azevedo CHM and Monteiro MC: Immune modulation

of some autoimmune diseases: The critical role of macrophages and

neutrophils in the innate and adaptive immunity. J Transl Med.

15(36)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Lagos LS, Luu TV, De Haan B, Faas M and De

Vos P: TLR2 and TLR4 activity in monocytes and macrophages after

exposure to amoxicillin, ciprofloxacin, doxycycline and

erythromycin. J Antimicrob Chemother. 77:2972–2983. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Wu J, Mo J, Xiang W, Shi X, Guo L, Li Y,

Bao Y and Zheng L: Immunoregulatory effects of Tetrastigma

hemsleyanum polysaccharide via TLR4-mediated NF-κB and MAPK

signaling pathways in Raw264.7 macrophages. Biomed Pharmacother.

161(114471)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|