Introduction

Delicate nickel-titanium instruments are essential

in root canal therapy. However, when the operation of the surgeon

is not standard or the morphology of the root canal is too complex,

the force applied to the instrument exceeds the antifatigue

strength, and the instrument is likely to fracture in the root

canal (1). It has been previously

reported that the worldwide probability of instrument fracturing

during root canal treatment ranges from 0.7 to 7.4%, which is

difficult to avoid even by experienced dentists and endodontists

(2-4).

Fatigue separation accounts for 50-90% of instrument separations

worldwide (5). During the process

of root canal preparation, tensile and compressive stresses are

repeatedly applied to the instrument, resulting in microcracks on

its surface. When the instrument works in the curved or narrow

parts of the root canal, the cracks are easily broken, resulting in

separation. The retention of fractured instruments (FIs) in the

root canal makes disinfection of the root canal, a critical factor

in the success of root canal therapy outcomes, difficult to achieve

effectively, thus reducing the success rate of treatment (6).

From the perspective of the patient, residual FIs

may trigger anxiety as they may be viewed as treatment failure or

even medical malpractice. Any problems the patient encounters in

the future may be attributed to this. Therefore, with the

popularization and availability of dental microscopy, ultrasonic

equipment and professional tools for removing FIs, the removal of

FIs is becoming the first-choice strategy for clinicians (7). However, since the majority of

separations occur during the treatment of root canals with poor

surgical fields and small, curved and severely calcified root

canals, not all files can be effectively removed. During the

process of establishing a straight path in the root canal, varying

degrees of tooth tissue are removed, increasing the risk of lateral

perforation and root fracture (8).

Therefore, bypass techniques, which consist of retaining and

bypassing the FI to seal the apical stop, should be considered.

However, the success rate of bypass techniques remains a topic of

debate in the field of root canal therapy. This report attempts to

explore the feasibility of bypass technique for FIs by comparing

the postoperative outcomes of removal and bypass techniques for the

same tooth.

Case report

The present case involved a 41-year-old female

patient who was conscious with no underlying disease. The patient

complained of pain in the left upper posterior tooth for 6 months,

which intensified in the last 3 days before presentation. The

patient reported that the affected tooth had been treated in

another hospital due to pain 2 years prior, but the discomfort

persisted after treatment. A sudden onset of pain 6 months prior to

admittance to hospital, which was not treated, had occurred

intermittently since then. However, 3 days prior to admittance to

hospital, the pain worsened and was only slightly relieved by

anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition, 2 days prior to admittance to

hospital, the patient was treated at another hospital, which

suggested implant restoration after extraction of the affected

tooth. In September 2021, after studying the medical history, the

implantologist at Xi'an International Medical Center Hospital in

Xi'an, China referred the patient to the endodontist for further

evaluation of the retention value of the affected tooth.

Intraoral examination revealed a large area of

defects on the distal proximal surface of tooth no. 26, with

partial loss of white filling material and secondary caries at the

edge of the material. The affected tooth experienced severe pain on

percussion, but no discomfort from cold stimulation or probing. The

extent of loosening was I˚. The buccal vestibular sulcus of the

affected tooth was swollen and painful to press. A fistula was

observed in the mucosa of the buccal apical region. Periodontal

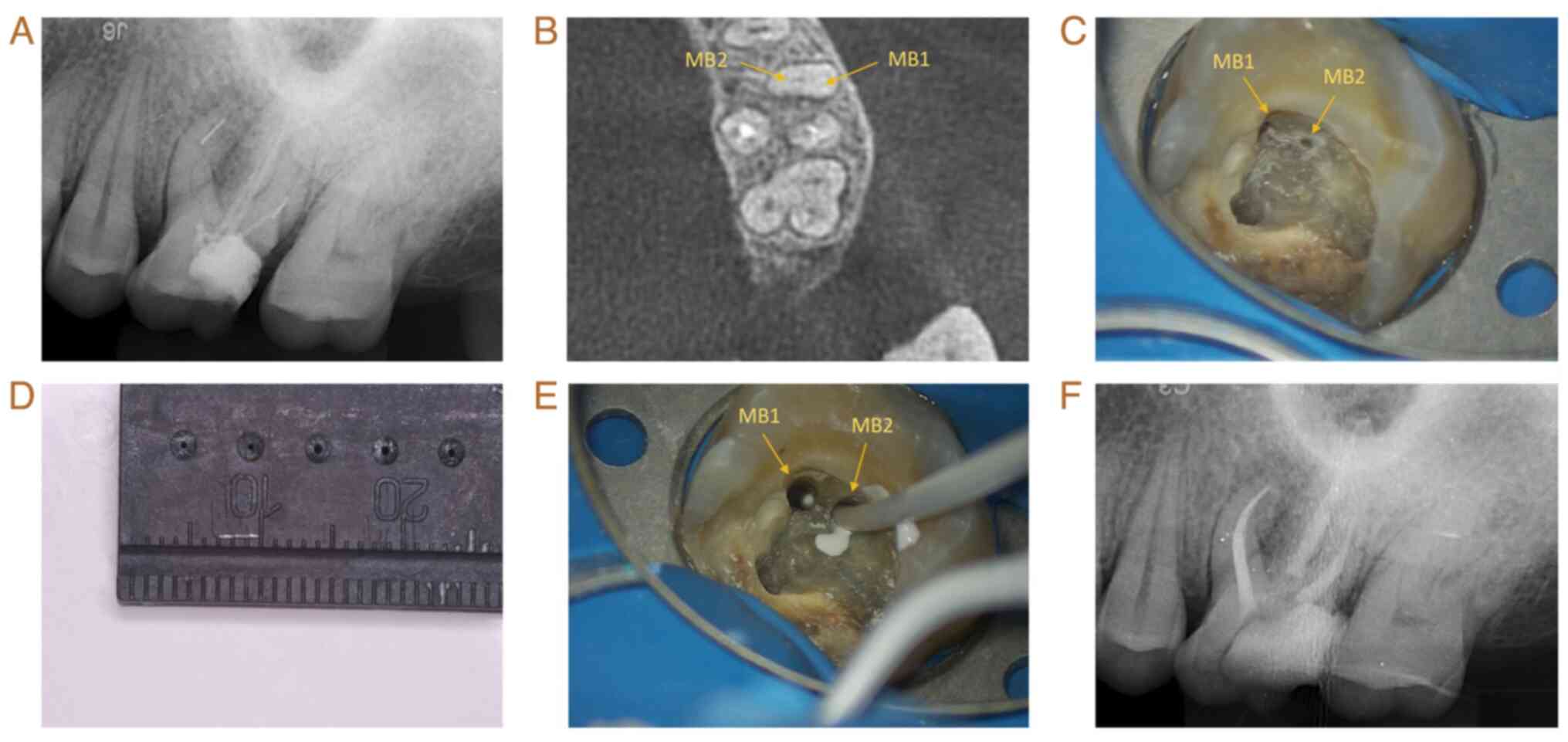

probing revealed no significant attachment loss. Diagnostic X-ray

revealed that tooth no. 26 had been endodontically treated

(Fig. 1A). There were suspected

FIs in the apical segment of the mesiobuccal (MB) root and the

middle segment of the distal buccal (DB) root; the palatal (P)

canal filling was underfilled, and there was also a large hypodense

area surrounding the periapex of the three aforementioned roots

(Fig. 1A). Cone-beam CT (CBCT)

revealed that the MB root was suspected of having two canals, where

the FI was present in the first MB canal (MB1) but there was no

obvious filling in the MB2 (Fig.

1B). On the basis of these observations, a diagnosis of chronic

apical periodontitis was made for tooth no. 26. Since the patient

expressed a desire to retain the affected tooth, root canal

retreatment of tooth no. 26 was planned after communication with

the patient. Specifically, the intended protocol involved removing

the FI at the middle of the DB canal, establishing a bypass through

the MB2 canal for treating the MB root and then retreating the P

root.

The original filling was removed via a diamond bur,

after a rubber dam was used to isolate the affected tooth. Under a

dental operating microscope (OMS 2380; Zumax Medical Co., Ltd.),

two root canal orifices, MB1 and MB2, could be observed in the MB

root (Fig. 1C). The FIs in the DB

canal were removed (Fig. 1D) via

the ET20 and ET25 working tips with an ultrasonic therapeutic

instrument (P5 Newtron XS; Satelec; Acteon). A mechanical

endodontic retreatment file (PROTAPER A1412; Dentsply Sirona, Inc.)

was used to remove the filling material in the P canal. The initial

working length of the root canals was measured via diagnostic X-ray

and an apex locator (PROPEX II; Dentsply Sirona, Inc.).

Subsequently, no. 8 and no. 10 K files (K-FILES; Mani, Inc.) were

used to dredge the canals. The root canals were prepared using an

X-SMART endodontic micromotor (X-SMART PLUS; Dentsply Sirona,

Inc.). During preparation, the root canals were irrigated

repeatedly with 20 ml of 1% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution

and 5 ml of 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution.

The DB, MB1 and MB2 canals were prepared with a #25/0.04 taper,

whereas the P canal was prepared with a #35/0.04 taper. After

repeated irrigation using an ultrasonic therapeutic instrument,

sterile paper tips were used to dry the root canals, and calcium

hydroxide paste (ApexCal; Ivoclar Vivadent) was inserted into the

root canals. Upon inserting the paste into the MB2 root canal

orifice, it was observed that the paste flowed upwards from the MB1

root foramen (Fig. 1E), supporting

the suspicions that the MB1 canal fused with MB2 to form a single

canal at the apical segment. A sterile cotton pellet was placed in

the pulp chamber before the access cavity was sealed via temporary

sealing paste (Cavit-G; 3M ESPE).

At 2 weeks after the procedure, the affected tooth

had no percussion pain or abnormal mobility. The apical segments of

the MB2, DB and P canals were filled with large taper gutta-perchas

(RECIPROC; VDW GmbH) and injectable root canal sealers (iRoot SP;

Innovative BioCeramix, Inc.) via the vertical compression

technique. The middle and coronal segments of the four root canals

were filled with warm gutta-percha via a gutta-percha heating

system (WL-B1; B&L Biotech). After filling, X-ray imaging

revealed that all the root apexes were fully filled (Fig. 1F).

At 1 week later, the affected tooth demonstrated no

percussion pain, no abnormal mobility and no obvious abnormalities

in the buccal or lingual mucosa. The tooth was restored with an

onlay.

At 9 months after surgery, CBCT revealed that the

hypodense area surrounding the DB, MB and P root apex had

significantly diminished (Fig. 2).

At 27 months after surgery, CBCT revealed that the hypodense areas

surrounding the DB, MB and P root apex almost completely

disappeared (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2Follow-up observation of tooth no. 26

via X-ray. (A) Sagittal X-ray of the MB root. the first was taken

before the operation, the second was taken 9 months after the

operation and the third was taken 27 months after the operation.

(B) Coronal X-ray of the MB root. The first was taken before the

operation, the second was taken 9 months after the operation and

the third was taken 27 months after the operation. (C) Sagittal

X-ray of the DB root. The first was taken before the operation, the

second was taken 9 months after the operation and the third was

taken 27 months after the operation. (D) Coronal X-ray of the DB

root. The first was taken before the operation, the second was

taken 9 months after the operation and the third was taken 27

months after the operation. (E) Sagittal X-ray of the P root. The

first was taken before the operation, the second was taken 9 months

after the operation and the third was taken 27 months after the

operation. (F) Coronal X-ray of the P root. The first was taken

before the operation, the second was taken 9 months after the

operation and the third was taken 27 months after the operation.

(G) Cross-sectional X-ray of the three types of roots. The first

was taken before the operation, the second was taken 9 months after

the operation and the third was taken 27 months after the

operation. MB, mesiobuccal; FI, fractured instrument; DB, distal

buccal; P, palatal. |

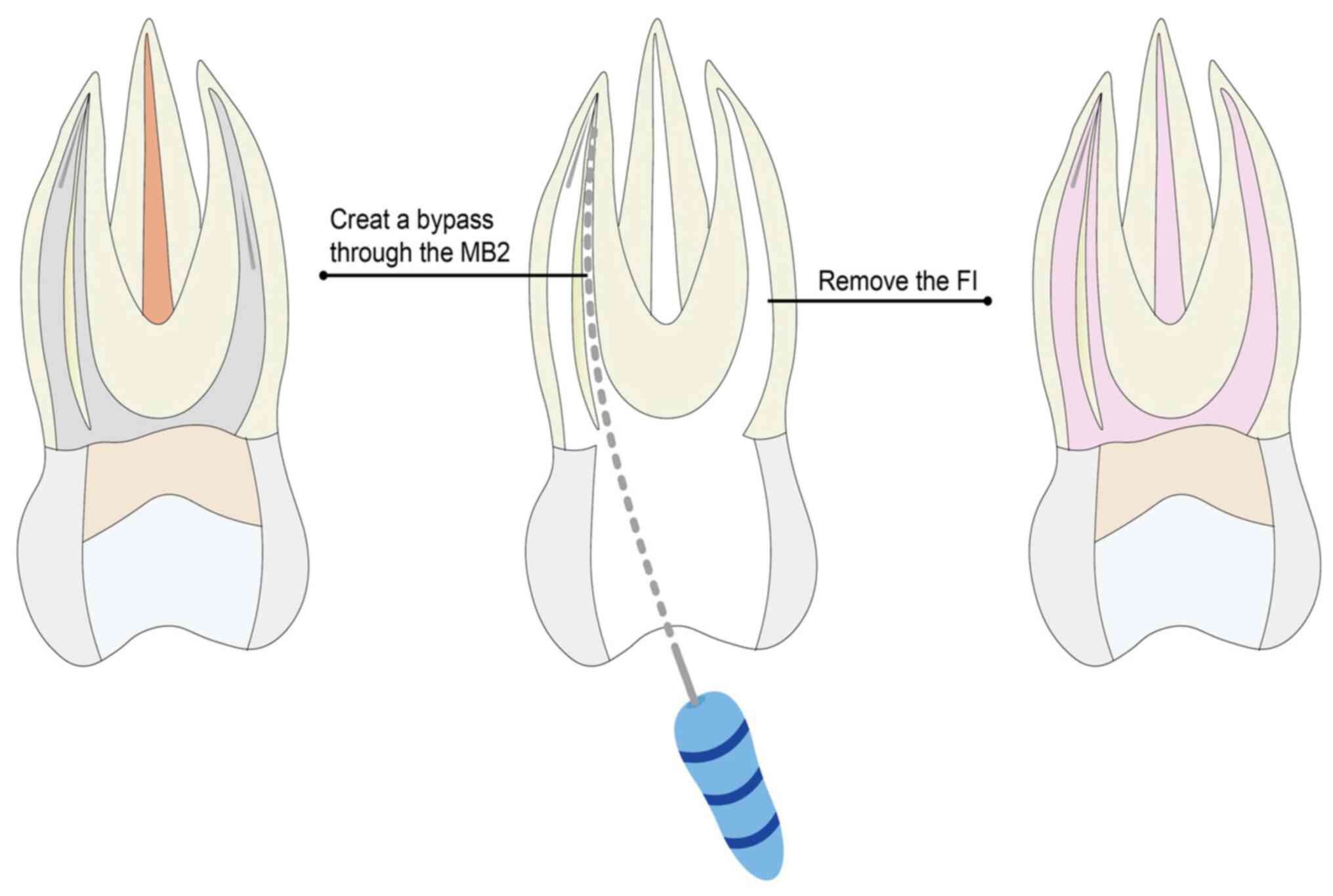

In the present case, FIs were successfully removed

from the middle third of the DB canal under an oral microscope with

the use of ultrasonic equipment. If attempts were made to remove

the FI in the MB root, regardless of success, then a large amount

of tooth tissue would have to be removed, increasing the risk of

para-perforation and root fracture. In addition, preoperative CBCT

revealed that the MB root had two canals, MB1 and MB2, which were

suspected to have fused into one canal at the apical segment.

Furthermore, the incidence of 2-into-1 canal when two canals are

present in the MB root of the maxillary first molar is ~60%

(9). Therefore, filling the apical

foramen of the MB root by establishing a bypass through MB2 was

planned before the operation, and was successfully implemented

(Fig. 3).

At 9 months after surgery, the periapical hypodense

areas surrounding the MB, DB and P roots markedly decreased, and

the periapical tissue had almost completely recovered at 27 months

after surgery.

The present report compared the postoperative

outcomes of removal and bypass techniques for the same tooth. The

bypass technique should therefore be considered a nonsurgical

treatment if the FIs in the root canal are difficult to remove or

if the post-removal risks become unacceptable.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, universal guidelines

for the management of root canals with FIs remain elusive. A

previous retrospective study suggested that the ability of a

physician to make a balanced decision by combining clinical

experience with the specific condition of the affected tooth is

important (7). During the

preoperative planning of the present case, the location of the FIs,

the anatomical characteristics of the root canals and the risk of

removal were considered. The final decision was made to remove the

FI in the middle of the DB canal and to treat the FI in the MB

canal by bypass. This allowed for the observation of differences in

the therapeutic outcomes between the removal technique and the

bypass technique. At 9 and 27 months of follow-up, the periapical

inflammation in both roots was markedly improved and the treated

tooth became asymptomatic. The results demonstrated that as long as

the root canal system was disinfected as much as possible, the

pathogens remaining on the FI surface of the root canal could be

effectively removed and the disinfected FIs would not cause

secondary infection of the root canal. When FIs are used as part of

the filling process, the root canal is tightly filled to prevent

the invasion of foreign pathogens and an ideal retreatment effect

can be achieved. Overall, as long as the infection in the root

canal is removed as much as possible and the root canal is tightly

filled, successful treatment can be performed. In the present case,

this was successfully achieved by using the bypass technique.

The removal of FIs has been considered the ideal

treatment after instrument separation (8). Widely accepted removal techniques

include the Endo Extractor system, the wire loop technique, the

Masserann kit and ultrasonication (10). In previous years, several reports

have proposed endodontic templates for guiding trephines (11), computer-assisted methods (12), modified hollow tube-based extractor

systems (13) and innovative

low-cost device techniques (14).

Previous studies have shown that the success rate of removal is

85.5% when the FI is visible under an oral microscope, but only

47.7% when the FI is not visible (7,15).

Among numerous file removal methods, ultrasonic techniques have

been consistently reported as safe and successful (16). In the present case, the visible FI

from the middle segment of the DB canal was successfully removed

using an ultrasonic device under the microscope. Ultrasonic

equipment has been used in endodontics since 1957 and has been

constantly improved. Current handpieces operating at 1-8 kHz have

been documented to improve the success rate of FI removal because

of their low shear stresses and fewer changes on the canal surface

(17).

In a series of cases reported by Hindlekar et

al (18), FIs were

successfully removed via the Acteon Satelec P5 Neutron, the same

device used for the present case. The unit tips of the device move

back and forth in a linear piston-like manner, rendering them

suitable for endodontic treatment (19). However, notably, the heat generated

by the friction between the ultrasonic tips and the root canal wall

may lead to instrument fatigue and secondary fracture of the

fragment. Therefore, ultrasonic tips at low-power levels cannot be

operated for prolonged periods (20). Hashem (21) previously demonstrated that water

should not be used to cool the ultrasonic tip to maintain a good

surgical field of view, and the power of the device should be set

to moderate and used intermittently (21).

Madarati et al (7) have suggested that five factors can

affect the efficacy of the bypass technique: i) Severity of the

tooth symptoms; ii) whether the tooth can establish a smooth bypass

to reach the apical stop; iii) whether the infectious tissue

surrounding the periapex of the affected tooth can be effectively

removed; iv) whether the bypass can be tightly filled; and v)

whether the periodontal infection can be effectively controlled if

the affected teeth have periodontal symptoms. In addition, the

treatment success rate of teeth with pulpitis is considerably

higher compared with that of teeth with periapical inflammation

(22). Although there was severe

periapical inflammation in the MB root of the affected tooth in the

present case, the inflammation was effectively controlled after the

establishment of a smooth bypass, removal of as much apical

infectious tissue as possible and tight filling of the apical stop.

The treatment effect on the affected tooth was obvious. The

periapical hypodense areas surrounding the MB root apex had

significantly diminished at 9 months after treatment, and almost

completely disappeared at 27 months after treatment. And by now,

the affected tooth has not experienced any discomfort.

Recently, with the upgrading of dental instruments

and the accumulation of research data, the type of FI and the

degree of canal curvature have also become important factors

affecting bypass therapy outcomes (23). It has been reported that the

success rate of bypassing RaCe is higher compared with that of K3

and Hero 642 rotary nickel-titanium files (23). By contrast, the success rate of the

bypass technique is improved for instruments that fractured in the

anterior part of the curved canal (23). In addition, compared with normal

root canals, the success rate of excessively curved canals is

markedly reduced (23).

Kalogeropoulos et al (24) suggested that preoperative CBCT

examination plays an important role in decision making prior to the

management of FI. In the present case, preoperative CBCT

examination revealed that the MB canal where the FI was located was

fused with the MB2 at the apical segment, justifying the bypass

technique instead of the removal technique on the basis of clinical

experience. For the effective removal of the smear layer and

infectious tissues in the root canal, Sinha et al (25) previously demonstrated that the use

of both EDTA and NaClO with the ultrasonic system appears to be the

most effective combination of flushing fluid. Liu et al

(26) reported that

laser-activated irrigation (LAI) and LAI combined with the

photon-induced photoacoustic streaming technique results in

increased vaporized bubble kinetics and superior cleaning efficacy

in the apical area, even in the presence of FIs. In addition, the

filling of bypass canals is one of the key factors for the success

of root canal therapy. Vadachkoria et al (27) demonstrated that thermoplastic

GuttaMaster and GuttaFusion show superior adhesion to the walls.

The heated gutta-percha has good fluidity and plasticity. The

vertical condensation technique used in the filling process can

fill the hot gutta-percha into all corners of the bypass canal,

achieving a satisfactory filling effect for some small curved

irregular gaps between the FI and the root canal wall. The cooled

gutta-percha and FIs then form a dense whole in the root canal that

is close to the root canal wall, achieving an ideal

three-dimensional root canal filling effect, tightly sealing the

root canal system and improving the success rate of root canal

treatment (28).

In conclusion, the present case suggested that the

bypass technique can be considered an alternative treatment if

removing FIs from root canals is considered too difficult and/or

risky. Clinicians should combine their clinical experience and the

specific FI conditions to make further decisions. However, there

are certain limitations to the present report. The results observed

in only one case are not sufficiently convincing and more samples

and data should be collected in follow-up research. In a follow-up

study, a total of 60 teeth that were removed during orthodontic

treatment will be selected and the nickel-titanium instruments in

the root apical segment will be broken. One group will be treated

by the removal technique, and the other group will be treated by

the bypass technique. The success rates of the two groups will be

recorded and the data will be statistically analysed. The results

will be used to further validate the current conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Natural Science

Foundation of Shaanxi Province (grant no. 022JM-447).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AZ and RM performed the treatment. XJ collected

data, RC analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. EY and QZ made

contributions to the study's conception and design. AZ conceived

the study and provided financial support. AZ and RC confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

The patient involved in the present study provided

written informed consent for publication of their data and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wycoff RC and Berzins DW: An in vitro

comparison of torsional stress properties of three different rotary

nickel-titanium files with a similar cross-sectional design. J

Endod. 38:1118–1120. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Spili P, Parashos P and Messer HH: The

impact of instrument fracture on outcome of endodontic treatment. J

Endod. 31:845–850. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Khasnis SA, Kar PP, Kamal A and Patil JD:

Rotary science and its impact on instrument separation: A focused

review. J Conserv Dent. 21:116–124. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Parashos P and Messer HH: Rotary NiTi

instrument fracture and its consequences. J Endod. 32:1031–1043.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Plotino G, Costanzo A, Grande NM, Petrovic

R, Testarelli L and Gambarini G: Experimental evaluation on the

influence of autoclave sterilization on the cyclic fatigue of new

nickel-titanium rotary instruments. J Endod. 38:222–225.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McGuigan MB, Louca C and Duncan HF:

Clinical decision-making after endodontic instrument fracture. Br

Dent J. 214:395–400. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Madarati AA, Hunter MJ and Dummer PM:

Management of intracanal separated instruments. J Endod.

39:569–581. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Tikhonova S, Booij L, D'Souza V, Crosara

KTB, Siqueira WL and Emami E: Investigating the association between

stress, saliva and dental caries: A scoping review. BMC Oral

Health. 18(41)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Cleghorn BM, Christie WH and Dong CC: Root

and root canal morphology of the human permanent maxillary first

molar: A literature review. J Endod. 32:813–821. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chhina H, Hans MK and Chander S:

Ultrasonics: A novel approach for retrieval of separated

instruments. J Clin Diagn Res. 9:ZD18–ZD20. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Bordone A, Ciaschetti M, Perez C and

Couvrechel C: Guided endodontics in the management of intracanal

separated instruments: A case report. J Contemp Dent Pract.

23:853–856. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Pradhan B, Gao Y, Gao Y, Guo T, Cao Y and

He J: Broken instrument removal from mandibular first molar with

conebeam computed tomography based pre-operative computer-assisted

simulation: A case report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 59:795–798.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

AlRahabi MK and Ghabbani HM: Removal of a

separated endodontic instrument by using the modified hollow

tube-based extractor system: A case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep.

8(2050313X20907822)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Monteiro JC, Kuga MC, Dantas AA,

Jordao-Basso KC, Keine KC, Ruchaya PJ, Faria G and Leonardo Rde T:

A method for retrieving endodontic or atypical nonendodontic

separated instruments from the root canal: A report of two cases. J

Contemp Dent Pract. 15:770–774. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Nevares G, Cunha RS, Zuolo ML and Bueno

CE: Success rates for removing or bypassing fractured instruments:

A prospective clinical study. J Endod. 38:442–444. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Fu M, Huang X, Zhang K and Hou B: Effects

of ultrasonic removal of fractured files from the middle third of

root canals on the resistance to vertical root fracture. J Endod.

45:1365–1370. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Lea SC, Walmsley AD, Lumley PJ and Landini

G: A new insight into the oscillation characteristics of endosonic

files used in dentistry. Phys Med Biol. 49:2095–2102.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hindlekar A, Kaur G, Kashikar R and

Kotadia P: Retrieval of separated intracanal endodontic

instruments: A series of four case reports. Cureus.

15(e35694)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cuje J, Bargholz C and Hulsmann M: The

outcome of retained instrument removal in a specialist practice.

Int Endod J. 43:545–554. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Madarati AA, Qualtrough AJ and Watts DC:

Factors affecting temperature rise on the external root surface

during ultrasonic retrieval of intracanal separated files. J Endod.

34:1089–1092. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hashem AA: Ultrasonic vibration:

Temperature rise on external root surface during broken instrument

removal. J Endod. 33:1070–1073. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sjogren U, Figdor D, Persson S and

Sundqvist G: Influence of infection at the time of root filling on

the outcome of endodontic treatment of teeth with apical

periodontitis. Int Endod J. 30:297–306. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Arshadifar E, Shahabinejad H, Fereidooni

R, Shahravan A and Kamyabi H: Possibility of bypassing three

fractured rotary NiTi files and its correlation with the degree of

root canal curvature and location of the fractured file: An in

vitro study. Iran Endod J. 17:62–66. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kalogeropoulos K, Xiropotamou A, Koletsi D

and Tzanetakis GN: The effect of cone-beam computed tomography

(CBCT) evaluation on treatment planning after endodontic instrument

fracture. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(4088)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Sinha S, Barua AND, Rana KS, Singh K,

Kumar S and Saini R: Comparison of efficacy of various intracanal

irrigants with ultrasonic bypass system. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 13

(Suppl 2):S1390–S1393. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu J, Watanabe S, Mochizuki S, Kouno A

and Okiji T: Comparison of vapor bubble kinetics and cleaning

efficacy of different root canal irrigation techniques in the

apical area beyond the fractured instrument. J Dent Sci.

18:1141–1147. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Vadachkoria O, Mamaladze M, Jalabadze N,

Chumburidze T and Vadachkoria D: Evaluation of three obturation

techniques in the apical part of root canal. Georgian Med News.

17-21:2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ho ES, Chang JW and Cheung GS: Quality of

root canal fillings using three gutta-percha obturation techniques.

Restor Dent Endod. 41:22–28. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|