Introduction

Chronic low back pain (CLBP) is a widespread public

and occupational health issue, affecting ~23% of the population,

with 11-12% experiencing disability (1,2).

CLBP lasts 12 weeks or more and is influenced by various factors,

including genetics, age, fitness level, weight and mental

well-being (3,4). A number of studies have shown that

the prevalence of CLBP steadily increases from the 3rd to the 6th

decade of life, with a higher prevalence observed among women

(3,4). In developed countries, 49-90% of

individuals will experience at least one episode of low back pain

in their lifetime, with the majority experiencing temporary relief

within 2 weeks. However, 2-7% of people will go on to develop CLBP

(3,4).

Duloxetine, a serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake

inhibitor, increases dopamine levels in the prefrontal cortex and

enhances the activity of noradrenergic and serotonergic neurons in

the descending spinal pathway; thus, alleviates neuropathic and

chronic pain (5,6). Clinical trials as well as systematic

reviews, have demonstrated its effectiveness in treating CLBP, with

significant improvements compared with placebo. A clinical trial

conducted by Skljarevski et al (7), involving 404 patients with

non-radicular CLBP over a 13-week period, demonstrated that the

duloxetine group exhibited improvement in functional outcomes

compared with the placebo group. Two previous systematic reviews by

Weng et al (8) and Hirase

et al (9) have been

conducted to investigate the effect of duloxetine on CLBP. However,

Weng et al (8) examined the

impact of duloxetine on CLBP and osteoarthritis, while Hirase et

al (9) performed a systematic

review without a meta-analysis due to heterogeneity.

Considering the lack of comprehensive investigations

into CLBP and the publication of recent clinical trials evaluating

the use of duloxetine, the present systematic review was conducted

to incorporate the most up-to-date evidence available as of the

publication date of the present study. The current review aimed to

not only assess the efficacy of duloxetine in managing CLBP but

also explore its impact on the quality of life of the patients and

the frequency of serious adverse effects.

Materials and methods

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items

for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement

(10), ensuring methodological

rigor and transparency throughout the research process.

Eligibility criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that examined

duloxetine across various dosage regimens in individuals suffering

from chronic low back pain (CLBP) were included, compared with

placebo. Observational studies, those with duplicated or

overlapping populations, and those focusing solely on acute low

back pain were excluded. Furthermore, studies that used accompanied

treatment, such as exercise, electrotherapy or physiotherapy were

excluded from this meta-analysis to maintain the integrity and

relevance of the selected literature.

Search strategy

A comprehensive and systematic search strategy was

developed based on four prominent electronic bibliographic

databases: PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Web of Science

(https://0710oser8-1106-y-https-www-webofscience-com.mplbci.ekb.eg/wos/woscc/basic-search),

Cochrane Central (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/advanced-search) and

Scopus (https://07105seqa-1106-y-https-www-scopus-com.mplbci.ekb.eg/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic).

The present study aimed to maximize the retrieval of relevant

articles published from the inception of each database up to March

2024. The search strategy used was as follows: For PubMed,

(duloxetine hydrochloride OR duloxetine OR Cymbalta) AND (low back

pain OR back pain OR back pain OR backache); for Web of Science,

(duloxetine OR Cymbalta) AND (low back pain OR back pain OR back

pain OR backache); for Cochrane, (duloxetine OR Cymbalta) AND (low

back pain OR back pain OR back pain OR backache); and for Scopus,

(duloxetine OR Cymbalta) AND (low back pain OR back pain OR back

pain OR backache).

Study selection

A total of 2 independent reviewers performed the

study selection process. Initially, titles and abstracts were

screened to identify potentially eligible studies, followed by

full-text screening to confirm eligibility based on the predefined

inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using a structured

electronic data extraction sheet. A total of 2 independent

reviewers extracted the following data from the included studies:

Study name, year of publication, study design, interventions,

duration of duloxetine treatment, sample size, mean age, male

percentage, weight, follow up duration and outcome measures.

Definition of outcomes parameters

The visual analogue scale (VAS) is a subjective,

self-reported, pain rating scale. It is used to track pain

regression. A handwritten mark placed at one point along the length

of a 10 cm line that represents a continuum between the two ends of

the scale; ‘no pain’ on the left end (0 cm) of the scale and ‘worst

pain’ on the right (10 cm). Measurements from the zero point (left

end) of the scale to the patients' marks are recorded in cm and are

interpreted as their pain (11).

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) is a self-reported

assessment. It provides information on the intensity of pain

(sensory dimension or BPI-severity) and the degree to which pain

interferes with function (reactive dimension or BPI-Interference).

BPI-I is rated on a scale of 0 (no interference) to 10 (interferes

completely). The average of 7 items or questions that the BPI-I

scale addresses (general activity, mood, walking ability, normal

work, relations with other people, sleep and enjoyment of life)

were reported (12). The

Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire-24 (RMDQ-24) measures

physical disability due to CLBP on a scale ranging from 0 (no

disability) to 24 (severe disability) (13).

The SF-36 includes 36 questions. In total, 8

different sub-scores (physical and social functioning, physical and

emotional role limitations, mental health, energy, pain, and

general health perceptions), and a mental and physical summary

score can be obtained from these. A maximum score of 100 resembles

the best possible health state (14). Patients' global impression of

improvement (PGI-I) compares a participant's perception of

improvement at the time of assessment with treatment initiation

time. Score varies from 1 (very much better) to 7 (very much worse)

(15).

Of the included studies, only Raskin et al

(16) specifically addressed

depression, defining it according to DSM-IV criteria (17). While this definition was referenced

in the present study, none of the other 7 studies included a focus

on depression. Depression was defined according to the criteria of

DSM- IV (17). The included study

by Raskin et al (16) also

defined depression as in the DSM-IV. The diagnosis was confirmed by

the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview, a standardized

diagnostic interview based on DSM-IV criteria (17). Baseline disease severity was

defined by patients' scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

with 17 items (HAM-D) (18).

Patients were required to have a HAM-D total score of ≥18 at visits

1 and 2; a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of ≥20 with

or without mild dementia; and at least one previous episode of

major depression. Patients with an MMSE score of 20 to 23 were

categorized as having mild dementia, while those with a score of

≥24 were categorized as having no dementia (18).

Quality assessment

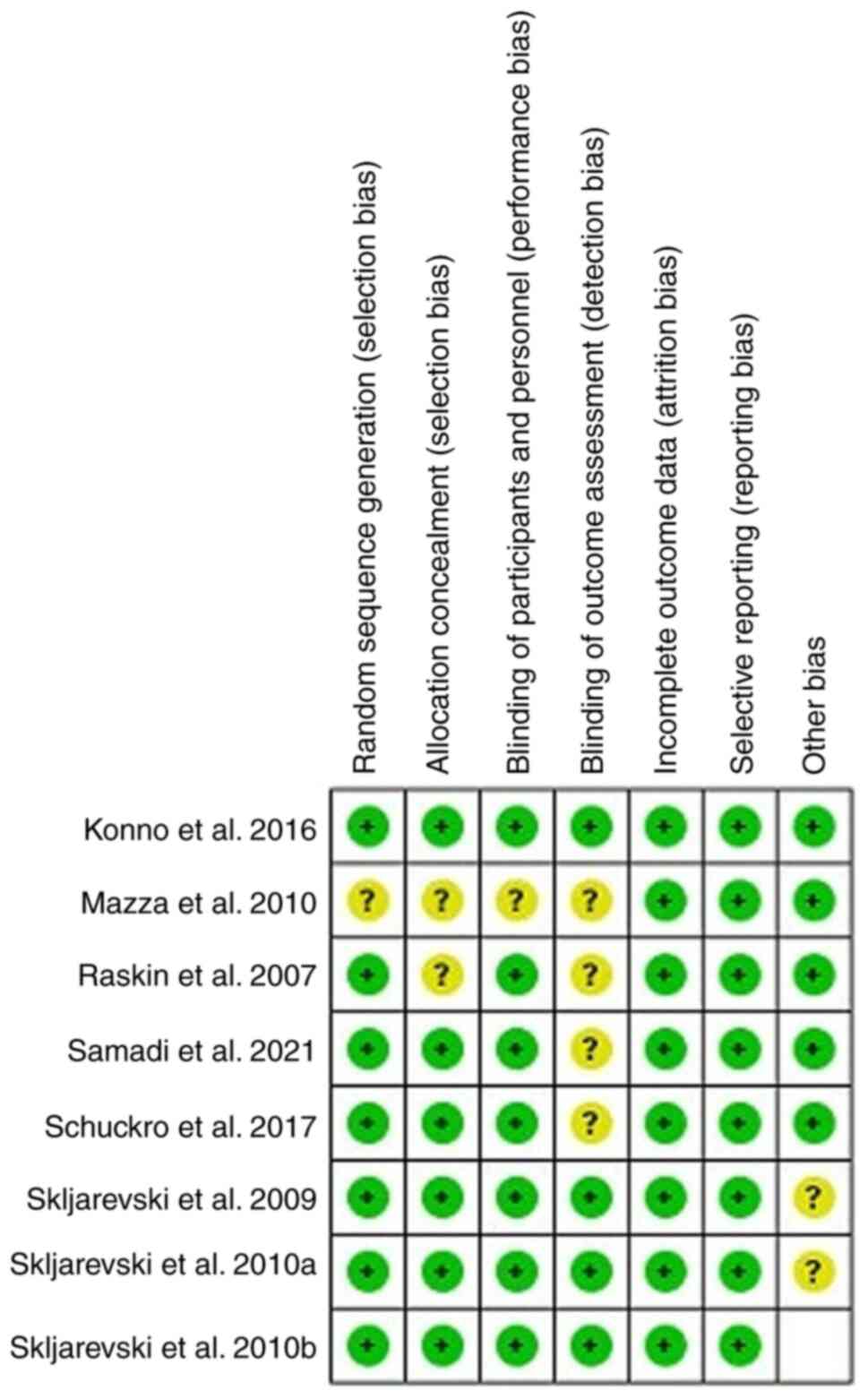

The risk of bias in the included RCTs was assessed

using the well-established Cochrane collaboration tool (19). This evaluation included sequence

generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome

data, selective outcome reporting and other potential sources of

bias. Each study's bias risk was categorized as ‘Low’, ‘High’, or

‘Unclear’ ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the

methodological quality and robustness of the included studies.

Data analysis

For dichotomous data, risk ratios (RR) with 95%

confidence intervals (CIs) were used. For continuous data, the mean

differences (MD) with 95% CI were employed. Data synthesis was

performed using the R software (meta-package; v.6.5-0; https://www.r-project.org/). Visual inspection of the

forest plots and measurement of the Q and I2 statistics

were used to assess heterogeneity. Significant statistical

heterogeneity was indicated by the Q statistic P<0.1 or

I2>50%. Random effect model was used in the

meta-analysis.

Results

Search results

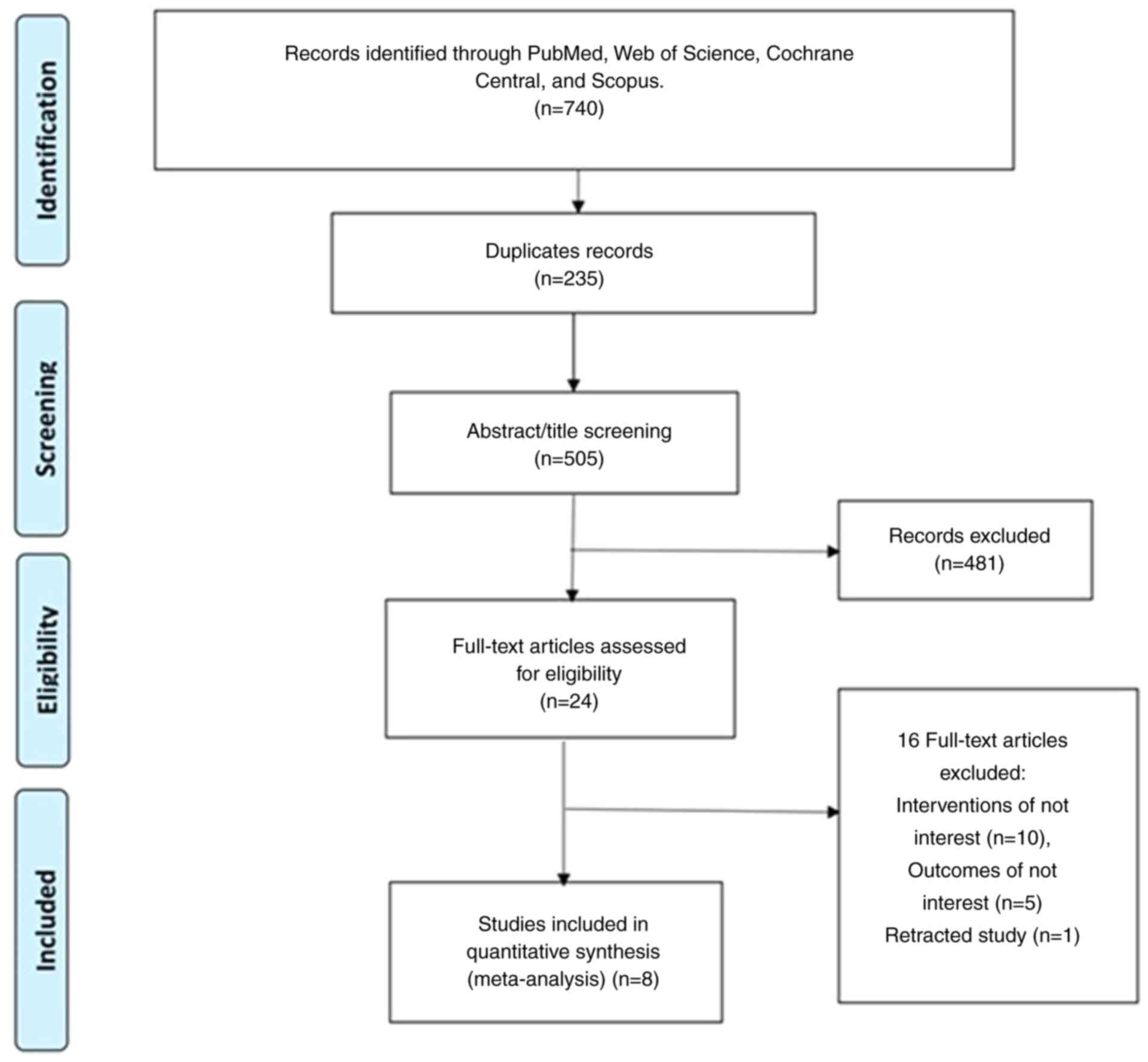

A total of 740 records were identified, 235

redundant entries were removed and 505 unique records were

reviewed. After assessing the full-text articles, the pool was

narrowed down to 24 relevant studies, and finally a total of 8

studies were included in the meta-analysis. Any discrepancies were

resolved through discussion and consensus to ensure the robustness

and integrity of the study selection process. The study selection

process is shown in Fig. 1.

Study characteristics

The included studies collectively enrolled a total

of 1,985 patients. These studies have exhibited diverse

characteristics, as summarized in Table I. The methodological quality of

each study was evaluated using the Cochrane collaboration tool,

illuminating a spectrum ranging from moderate to high quality

(Fig. 2).

| Table ISummary table of included studies;

RCT, randomized controlled trial; NA, not available. |

Table I

Summary table of included studies;

RCT, randomized controlled trial; NA, not available.

| First author,

year | Study design | Interventions | Duration of

duloxetine treatment in weeks | Sample size | Mean age (standard

deviation) (Intervention/control) | Male n (%)

(Intervention/control) | Weight (kg)

(Intervention/control) | Follow up in

weeks | Outcome

parameters | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Raskin et

al, 2007 | RCT | Duloxetine (60 mg)

vs. placebo | 8 | 311 | 72.6 (5.7)/73.3

(5.7) | 82 (39.6%)/44

(42.3%) | 80 (17.7)/79.7

(18.8) | 8 | VAS | (16) |

| Skljarevski et

al, 2009 | RCT | Duloxetine 60-120mg

vs. placebo | 13 | 404 | 52.9 (12.8)/54.0

(13.5) | 23 (39%)/53

(45.3%) | 84.9 (14.2)/81.9

(17.4) | 13 | Weekly mean 24-h

average pain, RMDQ-24), PGI-I, BPI | (24) |

| Mazza et al,

2010 | RCT | Duloxetine 60 mg

vs. Escitalopram 20 mg | 13 | 85 | 53.6 (13.5)/52

(12.4) | 18 (43.1)/17

(43.6) | 81.5 (18.6)/82.7

(16.9) | 13 | Weekly mean 24-h

average pain, CGI-S, SF-36 | (32) |

| Skljarevski et

al, 2010a | RCT | Duloxetine 60-120

mg vs. placebo | 13 | 236 | 51.8 (14.9)/51.2

(13.5) | 44 (38.3)/48

(39.7) | 76.2 (14.7)/75.9

(13.9) | 13 | BPI, RMDQ, PGI,

CGI-S, BPI-S,BPI-I, weekly means of the 24-hour average pain | (23) |

| Skljarevski et

al, 2010b | RCT | Duloxetine 60 mg

vs. placebo | 12 | 401 | 54.9 (13.7)/53.4

(14.2) | 80 (40.4)/75

(36.9) | 78.3 (15.8)/79.4

(14.7) | 12 | BPI, PGI-I,

RMDQ-24, BPI-S, BPI-I, SF-36 | (7) |

| Konno et al,

2016 | RCT | Duloxetine 60 mg

vs. placebo | 14 | 458 | 60.0 (13.2)/57.8

(13.7) | 115 (50.0)/104

(46.0) | 63.56 (12.75)/63.15

(13.42) | 14 | BPI, GGI-S,

RMDQ | (22) |

| Schukro et

al, 2016 | RCT | Duloxetine 120 mg

vs. placebo | 8 | 40 | 57.9 (13.4) | 20 (49%) | 80.5 (18.3) | 8 | VAS | (20) |

| Samadi et

al, 2021 | RCT | Duloxetine 30 mg

vs. placebo | 6 | 50 | 45.13 (15.41)/52

(11.53) | 7 (46.67%)/11

(68.75%) | NA | 6 | VAS, SF-36 | (21) |

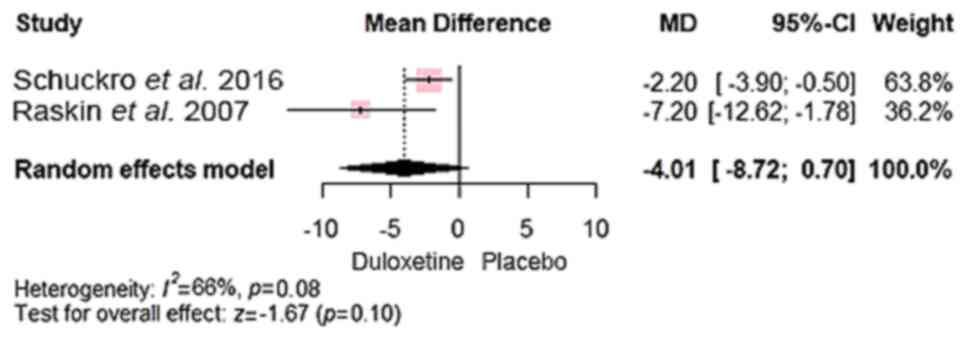

Outcomes. Pain reduction and physical

improvement

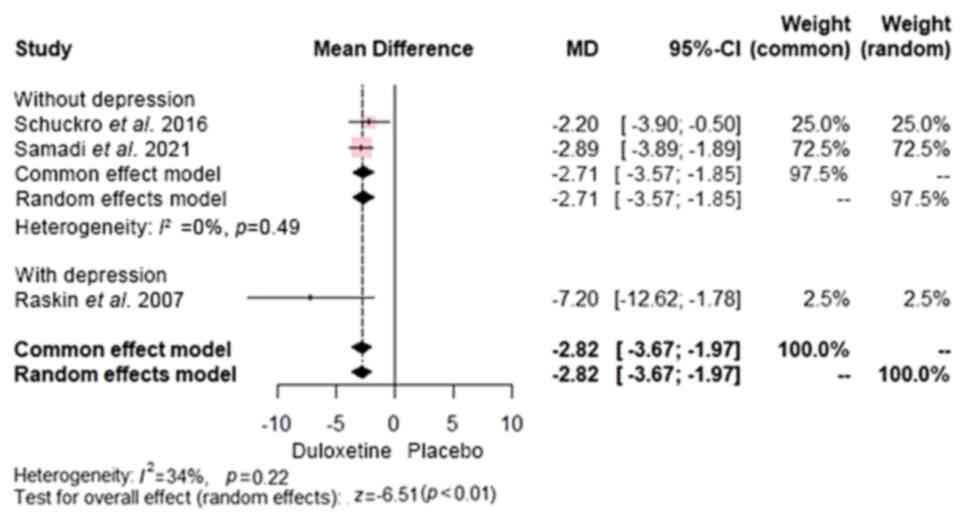

The results revealed that duloxetine was superior to

placebo in reducing pain intensity, as demonstrated by significant

improvements on both the VAS (20,21)

[MD, -2.82; 95% CI, (-3.67 to -1.97); P<0.0001]. A subgroup

analysis was conducted to differentiate patients with concomitant

depression from those with only CLBP. The results of both groups

(CLBP with and without depression) showed that duloxetine had

significant advantage over control [MD, -2.71; 95% CI, (-3.57 to

-1.85) and MD, -7.20; 95% CI, (-12.62 to -1.78), respectively]

(Fig. 3).

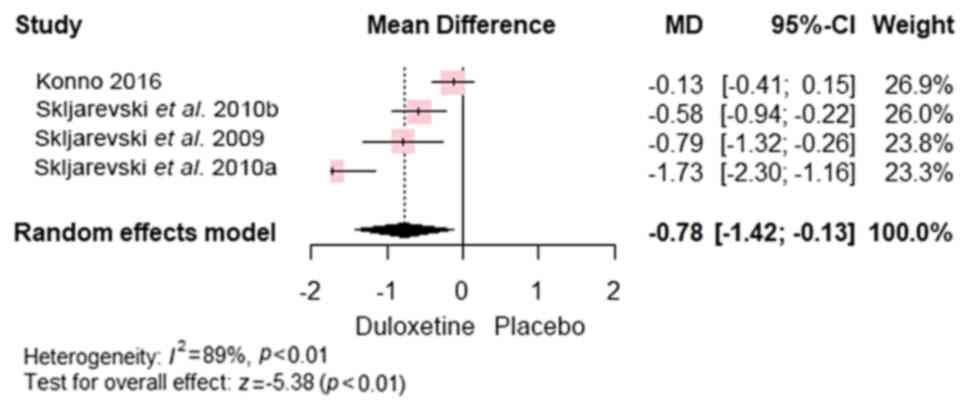

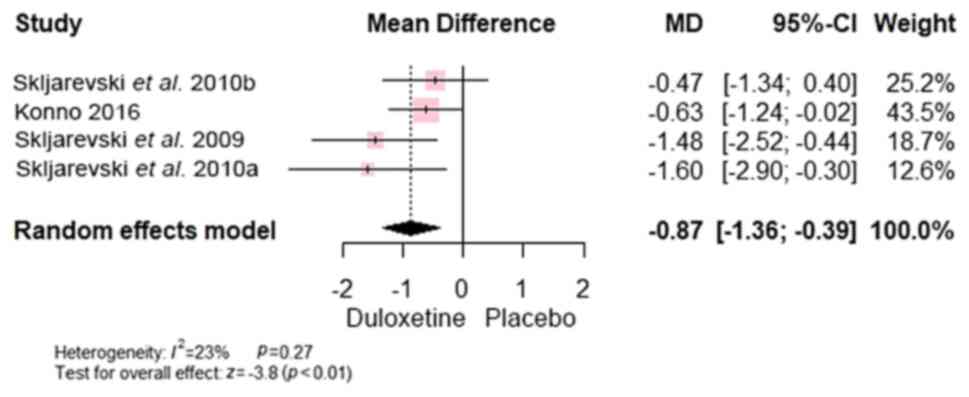

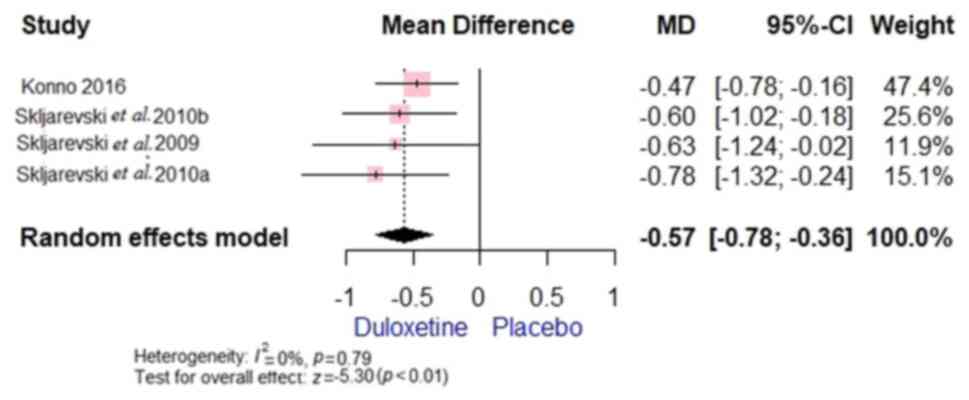

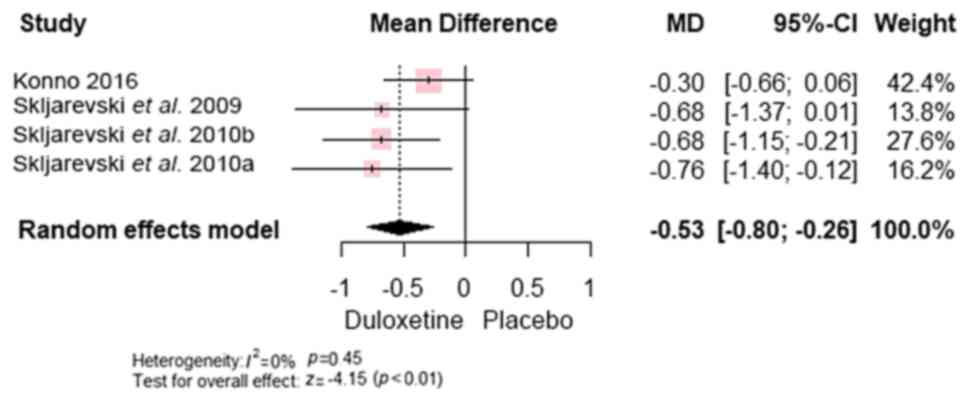

Furthermore, the overall mean difference favoured

duloxetine over control in terms of the BPI score (7,22-24)

[MD, -0.78; 95% CI, (-1.42 to -0.13); P<0.0001] (Fig. 4). In addition, the overall mean

difference between favoured duloxetine over control regarding the

RMDQ-24 scale [MD, -0.87; 95% CI, (-1.36 to -0.39), P<0.0001]

(Fig. 5), BPI-S average pain [MD,

-0.57; 95% CI, (-0.78 to -0.36); P<0.00001] (Fig. 6) and worst pain [MD, -0.53; 95% CI,

(-0.80 to -0.26); P<0.0001] (Fig.

7).

Quality of life. One study (21) reported on impact of duloxetine on

overall SF-36 scores, and showed no significant difference between

the compared groups [MD, 4.30; 95% CI, (-3.59 to 12.19);

P>0.05].

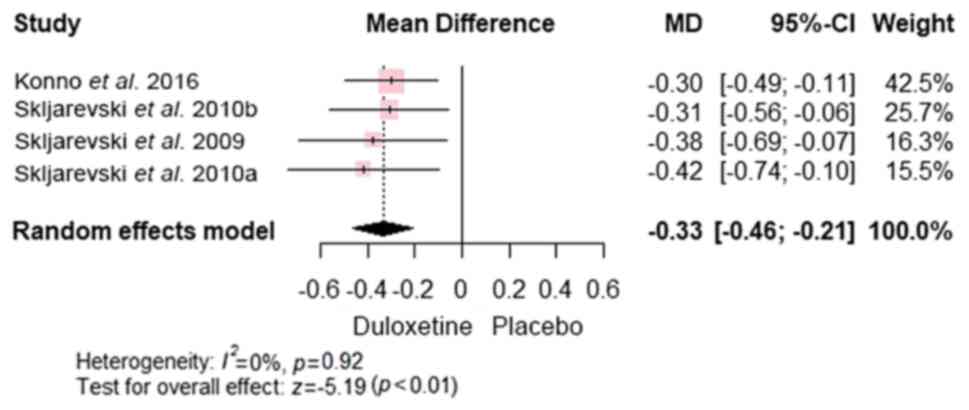

PGI-I. Assessment of PGI-I across the 4

studies (7,22-24)

revealed significant advantages of duloxetine over placebo [MD,

-0.33; 95% CI, (-0.46 to -0.21); P<0.0001)], with no significant

heterogeneity (P=0.92 and I2=0%) (Fig. 8).

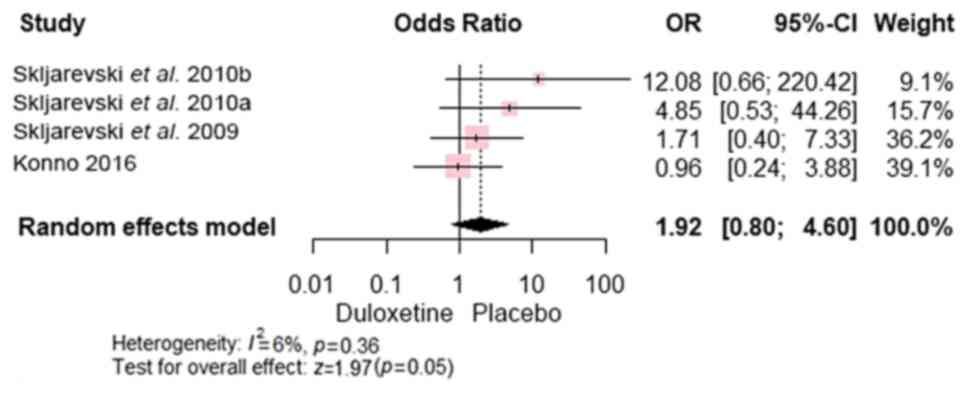

Safety and tolerability. In total, 7 studies

reported data on safety and tolerability while the study conducted

by Samadi et al (21) did

not report any data on side effects. The analysis revealed no

significant difference in the occurrence of serious adverse events

(chest pain, vertigo, dyspnoea, perioral numbness, perioral

numbness, myocardial infarction, toxic myopathy, asthma and alcohol

poisoning) between the duloxetine and control groups [RR, 1.92; 95%

CI, (0.80 to 4.60); P=0.054], with studies (7,22-24)

demonstrating homogeneity (P=0.36 and I2=6%) (Fig. 9).

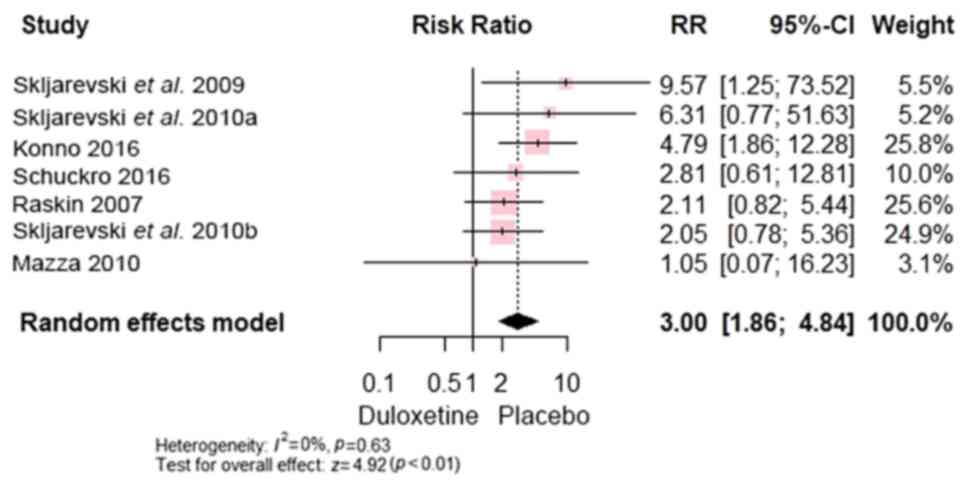

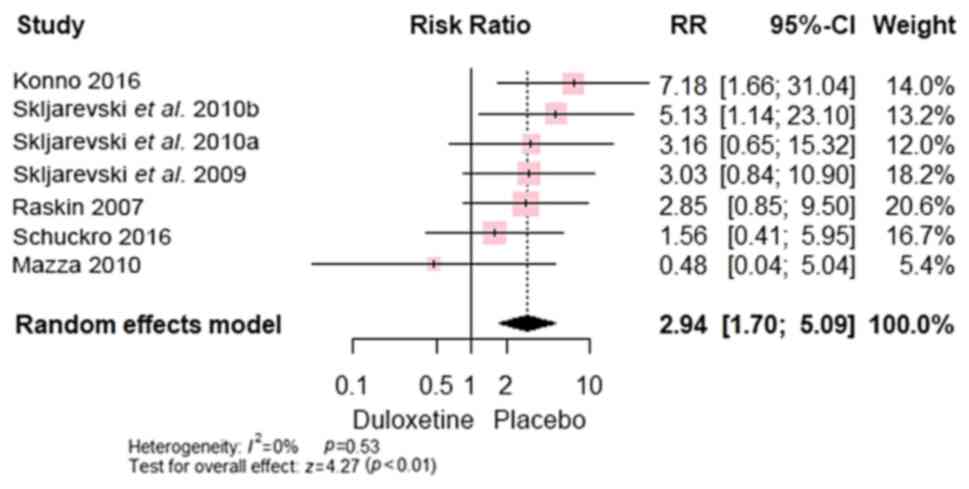

Compared with control, duloxetine exhibited more

constipation [RR, 3.00; 95% CI, (1.86 to 4.84); P<0.00001]

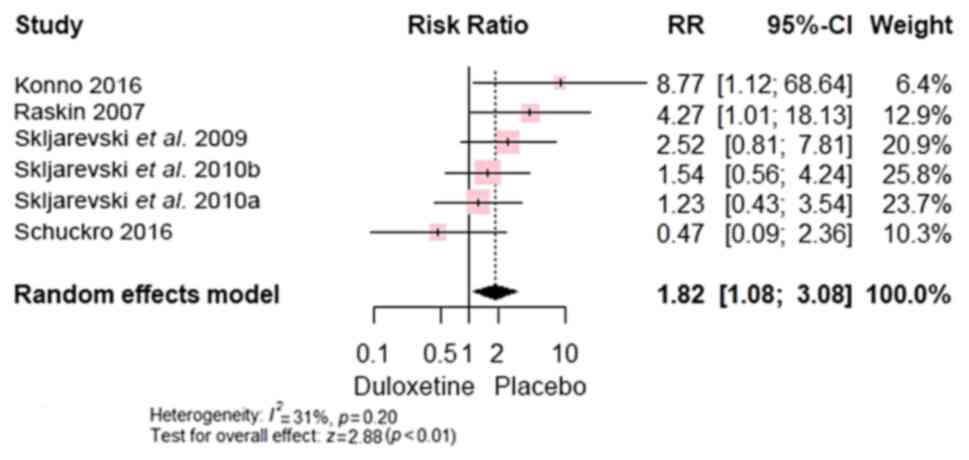

(Fig. 10), diarrhoea [RR, 1.82;

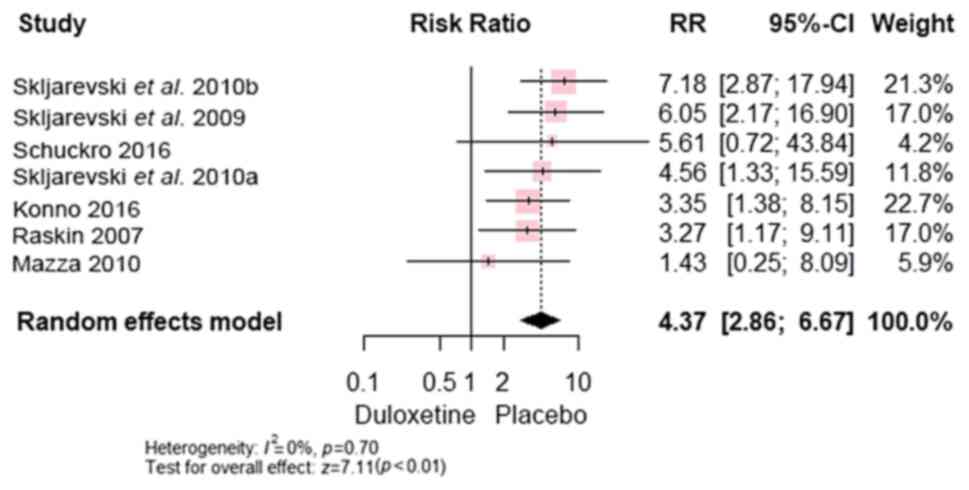

95% CI, (1.08 to 3.08); P<0.0001] (Fig. 11), nausea [RR, 4.37; 95% CI, (2.86

to 6.67); P<0.00001] (Fig. 12)

and dizziness [RR, 2.94; 95% CI, (1.70 to 5.09); P=0.0001]

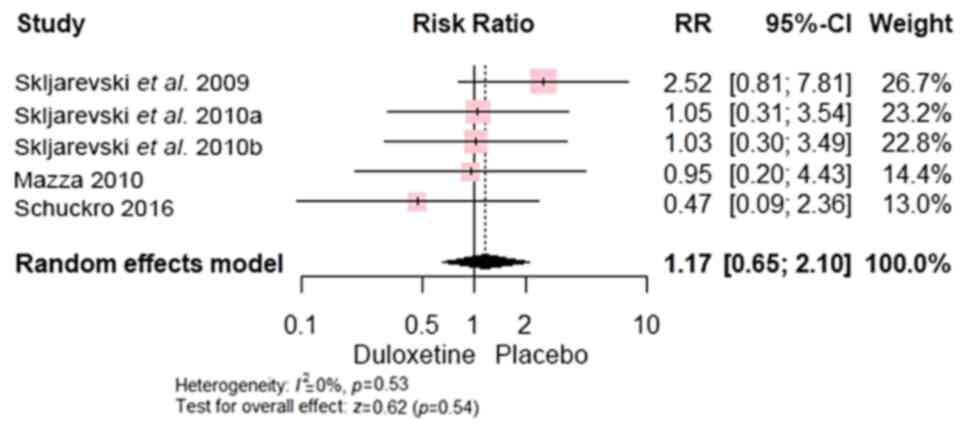

(Fig. 13). In addition, no

significant difference was found between both groups regarding

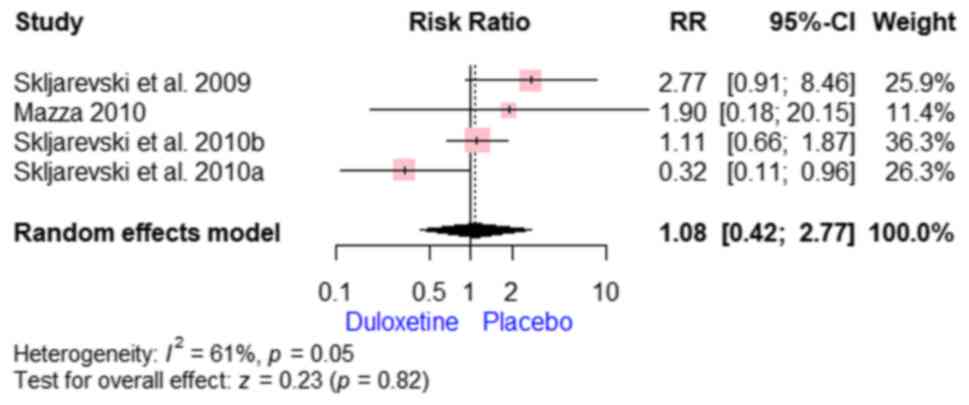

insomnia [RR, 1.17; 95% CI, (0.65 to 2.10); P=0.54] (Fig. 14) and headache [RR, 1.08; 95% CI,

(0.42 to 2.77); P=0.82] (Fig.

15).

Sensitivity analysis. A sensitivity analysis

was performed to evaluate the impact of excluding the study by

Samadi et al (21) that

included post-surgical patients. The aforementioned study only

reported on the VAS outcome. After removing it, the analysis did

not show significant difference between duloxetine and placebo in

terms of VAS outcome, as revealed in Fig. 16.

Discussion

The present study, including eight RCTs, provides

robust evidence, supporting the efficacy of duloxetine in reducing

pain and enhancing quality of life of patients with CLBP.

Duloxetine demonstrated superior outcomes over placebo in pain

reduction measured by the VAS, BPI, BPI-S, RMDQ-24 scales and worse

pain scales. In addition, duloxetine improved quality of life

assessed by the SF-36. Clinically, these results favor the

duloxetine group, indicating its efficacy in alleviating CLBP

symptoms and enhancing patients' overall well-being (25,26).

Although the overall trend supports the

effectiveness of duloxetine, individual study outcomes may vary.

Variations in the study design, patient populations and

methodological approaches contributed to the observed

heterogeneity. Discrepancies in the findings can be attributed to

factors such as differences in drug dosage, concomitant medication

usage, and patient characteristics such as age and comorbidities.

Methodological disparities, including study duration and outcome

measures, also contribute to variability among studies (27).

The superiority of the duloxetine group over the

placebo is scientifically grounded in its pharmacological mechanism

of action. As an antidepressant and serotonin-noradrenaline

reuptake inhibitor, duloxetine modulates neurotransmitter levels in

the central nervous system and attenuates pain-signaling pathways.

This neurobiological mechanism, coupled with the demonstrated

efficacy in clinical trials, elucidates why the duloxetine group

exhibited superior outcomes in terms of pain reduction and quality

of life improvement (28,29).

Previous studies have similarly highlighted the

efficacy of duloxetine in the management of CLBP, corroborating the

present findings (30,31). However, the present study advances

the existing literature by incorporating the most up-to-date

evidence through a comprehensive systematic review and

meta-analysis. These findings align with those of previous studies

that underscore the effectiveness of duloxetine in treating CLBP

(9). Nevertheless, the present

study provides additional insights and robust evidence, further

strengthening the existing body of literature on this topic.

The strengths of the present study include a

comprehensive methodology adhering to the PRISMA guidelines,

meticulous selection and analysis of relevant studies, and robust

assessment of study quality. However, limitations include the

observed heterogeneity across studies, potential biases inherent in

meta-analyses and limited number of included studies, which may

affect the generalizability of the findings.

Based on these results, future research should focus

on specific subpopulations, such as patients with depression and

CLBP, and explore the comparative efficacy of duloxetine in

conjunction with conservative therapies. Additionally, further

investigations into the efficacy of duloxetine across various types

of back pain and its long-term effects are warranted. Future

studies should also address the methodological inconsistencies and

biases observed in previous research to strengthen the evidence

base for the use of duloxetine in managing CLBP.

In conclusion, the present study has yielded

promising outcomes concerning pain alleviation and improvements in

the quality of life among individuals afflicted with CLBP. While

acknowledging limitations such as study heterogeneity and the

restricted number of included studies, the findings present

compelling evidence for the efficacy of duloxetine in mitigating

CLBP. These results highlight the potential of duloxetine as a

valuable therapeutic intervention in CLBP management, particularly

in individuals with comorbid depression. Further research is

imperative to address the prevailing limitations and

comprehensively validate these findings. Such efforts are crucial

for refining treatment approaches and advancing CLBP management on

a global scale.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

MSAS, AZA and DB conceptualized and designed the

study, contributed to data analysis and interpretation, and played

a major role in writing the manuscript. HEM and ZB did the initial

screening while ZB and DB contributed to full text screening and

data interpretation. HEM and ZB curated and analyzed the data,

created visualizations, and contributed to the interpretation of

results. DB, HEM and ZB drafted the initial manuscript, synthesized

study findings, and incorporated feedback from co-authors. All

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. MSAS

and HEM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Alfalogy E, Mahfouz S, Elmedany S, Hariri

N and Fallatah S: Chronic low back pain: Prevalence, impact on

quality of life, and predictors of future disability. Cureus.

15(e45760)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kahere M, Hlongwa M and Ginindza TG: A

scoping review on the epidemiology of chronic low back pain among

adults in sub-saharan africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

19(2964)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Nicol V, Verdaguer C, Daste C, Bisseriex

H, Lapeyre É, Lefèvre-Colau MM, Rannou F, Rören A, Facione J and

Nguyen C: Chronic low back pain: A narrative review of recent

international guidelines for diagnosis and conservative treatment.

J Clin Med. 12(1685)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Hnatešen D, Pavić R, Radoš I, Dimitrijević

I, Budrovac D, Čebohin M and Gusar I: Quality of life and mental

distress in patients with chronic low back pain: A cross-sectional

study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(10657)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Onuţu AH: Duloxetine, an antidepressant

with analgesic properties-A preliminary analysis. Rom J Anaesth

Intensive Care. 22:123–128. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dhaliwal JS, Spurling BC and Molla M:

Duloxetine. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing

Copyright ©. 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2024.

|

|

7

|

Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Desaiah D, Alaka

KJ, Palacios S, Miazgowski T and Patrick K: Duloxetine versus

placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: A 12-week,

fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trial. J Pain. 11:1282–1290.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Weng C, Xu J, Wang Q, Lu W and Liu Z:

Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in osteoarthritis or chronic low

back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 28:721–734. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hirase T, Hirase J, Ling J, Kuo PH,

Hernandez GA, Giwa K and Marco R: Duloxetine for the treatment of

chronic low back pain: A systematic review of randomized

placebo-controlled trials. Cureus. 13(e15169)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gift AG: Visual analogue scales:

Measurement of subjective phenomena. Nur Res. 38:286–288.

1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Cleeland CS and Ryan KM: Pain assessment:

Global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap.

23:129–138. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Stratford PW and Riddle DL: A roland

morris disability questionnaire target value to distinguish between

functional and dysfunctional states in people with low back pain.

Physiother Can. 68:29–35. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hays RD, Sherbourne CD and Mazel RM: The

rand 36-item health survey 1.0. Health Econ. 2:217–227.

1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Srikrishna S, Robinson D and Cardozo L:

Validation of the patient global impression of improvement (PGI-I)

for urogenital prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 21:523–528.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Raskin J, Wiltse CG, Siegal A, Sheikh J,

Xu J, Dinkel JJ, Rotz BT and Mohs RC: Efficacy of duloxetine on

cognition, depression, and pain in elderly patients with major

depressive disorder: An 8-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trial. Am J Psychiatry. 164:900–909. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Stein DJ, Phillips KA, Bolton D, Fulford

KW, Sadler JZ and Kendler KS: What is a mental/psychiatric

disorder? From DSM-IV to DSM-V. Psychol Med. 40:1759–1765.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Nixon N, Guo B, Garland A, Kaylor-Hughes

C, Nixon E and Morriss R: The bi-factor structure of the 17-item

hamilton depression rating scale in persistent major depression;

dimensional measurement of outcome. PLoS One.

15(e0241370)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni

P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L and Sterne JAC:

Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group.

The Cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in

randomised trials. BMJ. 343(d5928)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Schukro RP, Oehmke MJ, Geroldinger A,

Heinze G, Kress HG and Pramhas S: Efficacy of duloxetine in chronic

low back pain with a neuropathic component: A randomized,

double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. Anesthesiology.

124:150–158. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Samadi A, Salehian R, Kiani D and Jolfaei

AG: Effectiveness of duloxetine on severity of pain and quality of

life in chronic low back pain in patients who had posterior spinal

fixation. J Orth Trauma Rehabil. 6(144)2021.

|

|

22

|

Konno S, Oda N, Ochiai T and Alev L:

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of

duloxetine monotherapy in Japanese patients with chronic low back

pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 41:1709–1717. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Skljarevski V, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H,

Zhang Q, Chappell AS, Detke MJ, Iyengar S, Atkinson JH and Backonja

M: Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low

back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 35:E578–E585. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Skljarevski V, Ossanna M, Liu-Seifert H,

Zhang Q, Chappell A, Iyengar S, Detke M and Backonja M: A

double-blind, randomized trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the

management of chronic low back pain. Eur J Neurol. 16:1041–1048.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Brown JP and Boulay LJ: Clinical

experience with duloxetine in the management of chronic

musculoskeletal pain. A focus on osteoarthritis of the knee. Ther

Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 5:291–304. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Rodrigues-Amorim D, Olivares JM, Spuch C

and Rivera-Baltanás T: A systematic review of efficacy, safety, and

tolerability of duloxetine. Front Psychiatry.

11(554899)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Jia Z, Yu J, Zhao C, Ren H and Luo F:

Outcomes and predictors of response of duloxetine for the treatment

of persistent idiopathic dentoalveolar pain: A retrospective

multicenter observational study. J Pain Res. 15:3031–3041.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yasuda H, Hotta N, Nakao K, Kasuga M,

Kashiwagi A and Kawamori R: Superiority of duloxetine to placebo in

improving diabetic neuropathic pain: Results of a randomized

controlled trial in Japan. J Diabetes Investig. 2:132–139.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Obata H: Analgesic mechanisms of

antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Int J Mol Sci.

18(2483)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Onda A and Kimura M: Reduction in anxiety

during treatment with exercise and duloxetine is related to

improvement of low back pain-related disability in patients with

non-specific chronic low back pain. Fukushima J Med Sci.

66:148–155. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ferreira GE, McLachlan AJ, Lin C-WC, Zadro

JR, Abdel-Shaheed C, O'Keeffe M and Maher CG: Efficacy and safety

of antidepressants for the treatment of back pain and

osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ.

372(m4825)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mazza M, Mazza O, Pazzaglia C, Padua L and

Mazza S: Escitalopram 20 mg versus duloxetine 60 mg for the

treatment of chronic low back pain. Expert Opin Pharmacother.

11:1049–1052. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|