Introduction

Thyroid diseases encompass a spectrum of conditions,

ranging from aberrant growth disorders, such as benign nodules and

cancer, to hormonal disorders, including hypothyroidism,

hyperthyroidism and thyroid storm (TS). TS is a life-threatening

exacerbation of the hyperthyroid state (1). The primary characteristic of TS is

multi-organ dysfunction that can involve the cardiovascular,

thermoregulatory, gastrointestinal-hepatic and central nervous

systems (2,3). The incidence of TS is difficult to

approximate because of its rarity and absence of universally

approved criteria for its diagnosis (4-6).

At present, the diagnosis of TS is based on laboratory tests [low

to undetectable thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) <0.01 µIU/ml

with elevated free thyroxine and free triiodothyronine], coupled

with the presence of severe signs and symptoms, including

hyperpyrexia, cardiovascular dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms

and altered mental status (2,3). At

present, there are two scoring systems that may assist, including

the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS) and the Japan Thyroid

Association criteria (2,3). The main treatment method for TS is

medical management, including antithyroid drugs (propylthiouracil

and methimazole), iodine, glucocorticoids and β-adrenergic blockers

(7).

Acute airway obstruction is a life-threatening

disease that requires emergency intervention (8,9).

Acute airway obstructions induced by thyroid lesions are mostly

attributed to poorly differentiated and anaplastic thyroid

malignancies (8,9). In addition, a large benign thyroid

goitre can compress the trachea and induce airway obstruction

(8,9). The main treatment strategy for this

condition is the removal of this pressure immediately through

surgery, as is the case for large benign thyroid goitres (10). In the present report, a rare case

of TS accompanied by acute airway obstruction was documented. It is

hard to perform a thyroidectomy immediately as the thyroid surgery

may increase the severity of the TS. Therefore, in the present

study, TS was firstly controlled by medical treatment and then a

thyroidectomy was performed to solve the airway obstruction. The

patient recovered and was eventually discharged from the hospital

with prompt and effective treatment.

Case report

A 63-year-old female patient presented to the

Emergency Department of Weifang People's Hospital (Weifang, China)

with complaints of abdominal pain, dyspnoea and fever in April

2023. The patient had suffered from thyroid goitre, which has been

growing steadily but slowly for >30 years. Intermittent dyspnoea

episodes began 5 years prior, but they became more severe during

the 3 weeks prior to presentation. In addition, the patient had a

history of hyperthyroidism for 3 years, was irregularly receiving

methimazole for treatment and their biochemical tests yielded

relatively normal laboratory examination results. The liver

[glutamic-pyruvic transaminase, 23 U/l (normal range, 0-40 U/l);

glutamic oxalacetic transaminase, 331 U/l (normal range, 0-40 U/l)]

and kidney [creatinine, 44 µmol/l (normal range, 41-81 µmol/l)]

functions were normal. Vital signs on arrival were as follows:

Rectally measured temperature of 39.5˚C; heart rate of 125 beats

per min; respiratory rate of 30 breaths per min; and blood pressure

of 131/69 mmHg. Physical examination revealed a large mass on the

anterior neck without ulceration or discharge. The mass was not

tender but was warm to the touch, with a firm-to-hard consistency.

Laboratory tests (Table I) showed

TSH at <0.01 µIU/ml (normal range, 0.38-4.34 µIU/ml), free

triiodothyronine at 30.84 pmol/l (normal range, 2.77-6.31 pmol/l)

and free thyroxine at 106.72 pmol/l (normal range, 10.44-24.38

pmol/l). These laboratory test results showed that the patient had

hyperthyroidism.

| Table ISummary of the laboratory test results

of the patient. |

Table I

Summary of the laboratory test results

of the patient.

| Parameter | Day 1 | Day 7 | Day 22 | Day 53 | Normal range |

|---|

| Free

triiodothyronine, pmol/l | 30.84 | 7.66 | 5.74 | 4.95 | 2.77-6.31 |

| Free thyroxine,

pmol/l | 106.72 | 29.04 | 18.63 | 14.32 | 10.44-24.38 |

| Thyroid-stimulating

hormone, µIU/ml | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | 2.68 | 0.38-4.34 |

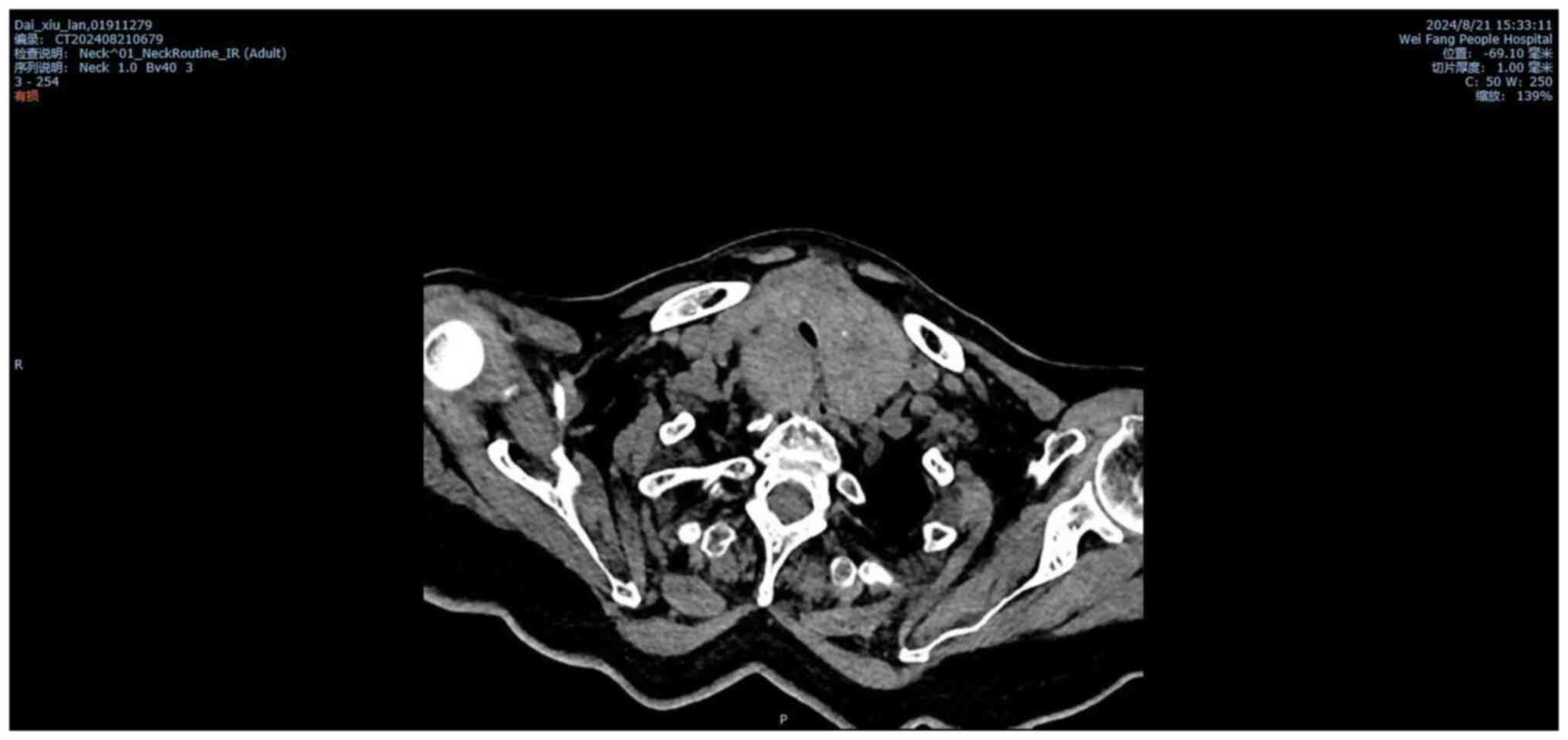

The electrocardiogram displayed marked sinus

tachycardia. Neck CT images revealed an enlarged bilateral thyroid

compressing most of the tracheal lumen, with the narrowest diameter

of the stenosis being 4.6 mm (Fig.

1). CT scan of the brain and abdomen yielded normal results

(data not shown).

Given the rapidly aggravating respiratory distress,

the patient immediately underwent an endotracheal intubation

without anaesthesia and was transferred to the intensive care

unit.

BWPS was calculated to be 70 points (with ≥45 points

indicating TS) (2,3) and the patient was diagnosed with TS

and acute airway obstruction. Treatment was promptly initiated with

nasogastric propylthiouracil (250 mg every 4 h), sodium iodide

(0.25 ml every 6 h), hydrocortisone (100 mg every 8 h) and esmolol

(10 mg every 4 h). Temperature was controlled with a cooling

blanket. In total, 7 days later, the vital signs were as follows:

Rectally measured temperature of 37.5˚C; heart rate of 92 beats per

min; and blood pressure of 125/90 mmHg. Thyroid function tests

showed TSH to be <0.01 µIU/ml, free triiodothyronine at 7.66

pmol/l and free thyroxine at 29.04 pmol/l. However, the intubation

could not be removed because of the stenosis of the trachea.

Therefore, the multidisciplinary team decided to perform a

thyroidectomy to reduce the bleeding and relapse immediately after

the TS had been controlled with medical treatment. Following

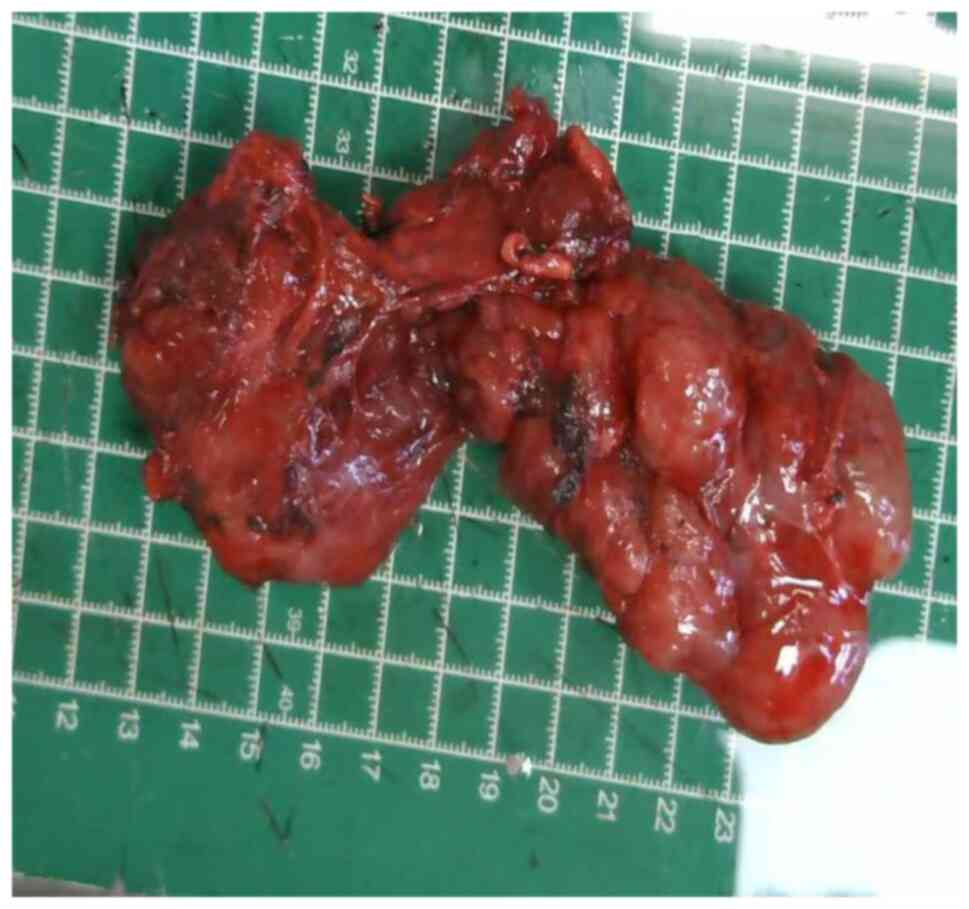

suggestions from the multidisciplinary team, a total thyroidectomy

was performed. During the gross examination, the thyroid was

composed of multiple nodules and the total volume of thyroid was

10x7x7 cm. (Fig. 2). Recurrent

laryngeal nerve and parathyroid glands were identified and

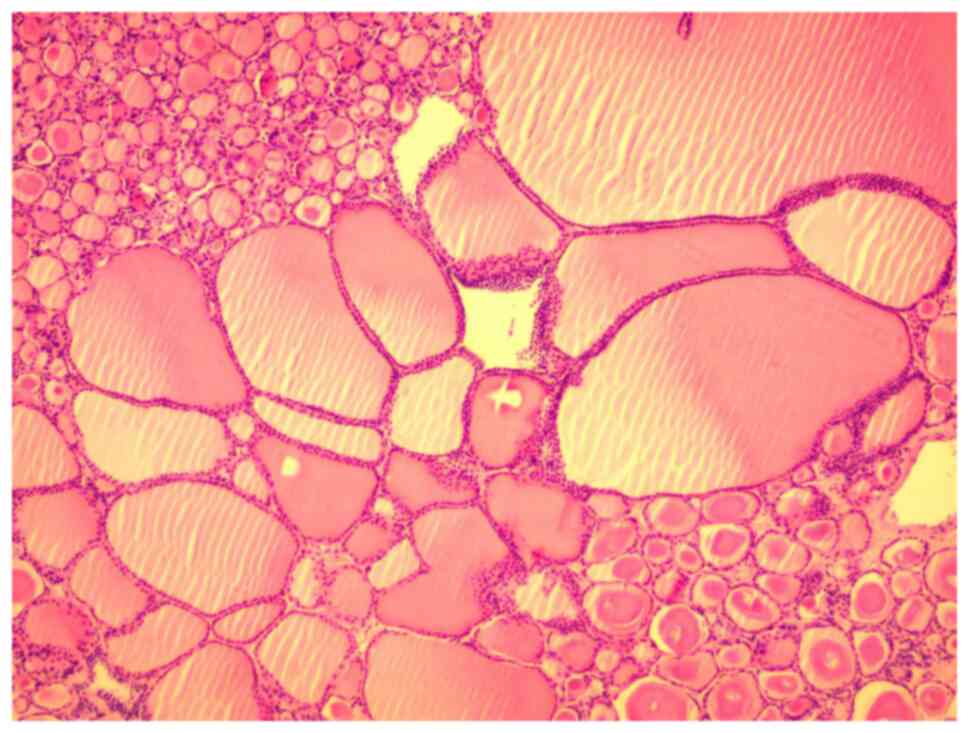

protected during the procedure. Specimens were fixed with 4%

formalin at room temperature for 12 h, embedded in paraffin, cut

into 4-µm sections, stained for 5 min at room temperature with

hematoxylin and eosin, and observed under a light microscope (x200

magnification). The thyroid demonstrated a benign multinodular

structure (Fig. 3). After surgery,

the patient was transferred to the thyroid surgery ward and their

vital signs were comparable to those at day 7. The intubation was

removed immediately after surgery. Sodium iodide (0.25 ml every 12

h) and hydrocortisone (100 mg every 12 h) were administered for 7

days after surgery. A total of 14 days after the surgery, thyroid

function tests revealed a TSH level at <0.01 µIU/ml, free

triiodothyronine at 5.74 pmol/l and free thyroxine at 18.63 pmol/l.

These results showed that the hyperthyroidism had been completely

controlled. Based on these laboratory findings and clinical

examinations, the patient's TS and trachea stenosis were deemed to

have been effectively resolved. The patient was subsequently

discharged from the hospital 15 days after the surgery.

Replacement therapy with L-thyroxine (75 µg/per day;

lifetime) began on the day that the patient was discharged from

hospital. Upon follow-up in the Thyroid Clinic of Weifang People's

Hospital, 1 month after discharge from the hospital, the patient

had normal thyroid function (TSH, 2.32 µIU/ml; free thyroxine,

14.32 pmol/l; and free triiodothyronine, 4.95 pmol/l) and did not

complain of dyspnoea. The patient has since been lost to

follow-up.

Discussion

TS is a life-threatening condition induced by

hyperthyroidism and causes multi-organ dysfunction (2,3). The

diagnosis of TS is based on laboratory tests and the presence of

severe signs and symptoms with evidence of thyrotoxicosis (2,3). TS

should be considered as one of the diagnostic possibilities in

patients with known hyperthyroidism (11,12).

Laboratory tests will typically show the TSH serum level to be low

to undetectable, whereas that of free thyroxine and free

triiodothyronine is typically elevated (11,12).

A number of precipitating factors can translate simple

thyrotoxicosis into the metabolic crisis of TS (2,3). For

example, patients with inadequately treated hyperthyroidism are at

a particularly increased risk of TS (2,3).

However, thyroid surgery without adequate drug control of

hyperthyroidism remains the most common cause of TS, although the

increased use of radioactive iodine has drastically reduced the

risk of TS due to this cause (11,12).

In addition, parturition, major trauma, non-thyroid surgery,

infection or iodine exposure from radiocontrast dyes may induce TS

in patients with thyrotoxicosis (2,3). In

the present case, the patient had a history of hyperthyroidism and

lacked a standardized treatment regimen. The compression of the

trachea induced by the goitre caused dyspnoea, which can induce a

stress response in the body. During the stress response, additional

thyroid hormones can be released into the bloodstream (11,12).

Therefore, the compression of trachea may have been one of the

causes of TS.

Hyperpyrexia (>39˚C) is universal in almost every

patient with TS (2,3). Overall, 84% of TS patients have

cardiovascular dysfunction, including tachycardia, systolic heart

failure with pulmonary and peripheral oedema, and high output heart

failure (2,3). In the present study, the patient had

tachycardia with a heart rate of 125 beats per min. A total of 51%

of patients with TS also suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms,

such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, jaundice, hepatic injury and

abdominal pain (2,3). In addition, altered mental status,

including confusion, stupor and coma, are some of the other common

symptoms of hyperthyroidism (2,3). TS

remains a diagnostic challenge, because of non-specific and varied

characteristics on presentation. Various diagnostic systems, such

as the BWPS or Japan Thyroid Association criteria (2,3),

have been previously established to facilitate the diagnosis and

evaluation of the severity of TS (13,14).

In the present case, the patient had symptoms of thermoregulatory

dysfunction, tachycardia and abdominal pain, whereas the BWPS was

calculated to be 70 points (≥45 points indicating TS). Therefore,

the patient was diagnosed with TS.

The treatment of TS should be initiated once its

diagnosis is suspected due to the 10% mortality rate associated

with this condition (2,3). A multidisciplinary team should be

organized immediately to successfully offer the patient all

possible therapeutic options. Management aims should include

attaining a euthyroid state through medical management (antithyroid

drugs and iodine) and definitive treatment through surgery. In

general, the patients with TS should be admitted to the intensive

care unit for aggressive medical management and undergo definitive

treatment. The medical treatment should not only target the

synthesis and release of thyroid hormone but also attempt to

minimize the effects of circulating thyroid hormones and prevent

end-stage organ damage (2,3). The initial management for the present

case involved the use of antithyroid hormones synthesis drugs

(propylthiouracil), antithyroid hormones synthesis drug (sodium

iodide) and an antithyroid peripheral conversion drug

(hydrocortisone), which stabilized the hemodynamic status.

Acute airway obstruction was another issue that had

to be resolved for the patient in the present report. This is a

life-threatening condition that can be caused by upper respiratory

tract infections, resulting in oedema and retention of secretions,

sudden intrathyroidal haemorrhage and tracheal stenosis or collapse

(8,9). In the present case, the cause of

acute airway obstruction was compression by the enlarged thyroid.

In addition, airway compression may be an aetiological factor and

aggravated symptom of TS. The most effective treatment method for

this condition appears to be the physical removal of airway

obstruction induced by the enlarged goitre. However, the

cardiovascular dysfunction induced by TS impedes treatment

execution because of the high mortality rates of the former

(8,9). In addition, thyroid surgery may

increase the severity of TS (2,3).

These issues cause difficulty in the design of an optimal treatment

strategy. Ultimately, in the present case, the multidisciplinary

team decided to perform thyroidectomy to reduce the bleeding and

relapse immediately after TS was controlled with medical

treatment.

A previous case report showed a case of a

42-year-old male patient with acute airway obstruction induced by a

giant thyroid accompanied by TS (15). The patient had undergone emergency

total thyroidectomy due to the failure of tracheostomy. Although

the symptoms of TS had not worsened in the perioperative period,

the TS and airway obstruction was completely resolved similar to

the present case. However, surgery in cases of uncontrolled

hyperthyroidism may enhance the crisis of TS (2,3). In

the present case, a female patient with acute airway obstruction

and TS was presented. Specifically, the symptoms of TS were firstly

controlled, followed by thyroidectomy. Due to the difficulty of

tracheostomy, endotracheal intubation was performed to establish

the breathing passage, which provided vital additional time for

controlling the TS.

In conclusion, TS and acute airway obstruction are

both rare but potentially life-threatening disorders associated

with a high mortality rate. However, optimal medical treatment,

including antithyroid hormones synthesis drugs (propylthiouracil),

antithyroid hormones synthesis drug (sodium iodide) and an

antithyroid peripheral conversion drug (hydrocortisone), to control

the symptom of TS and then emergency thyroid surgery appear to be

safe options for patients with TS.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YW and JH conceived the case report. YW, LW and JH

performed the surgery. ZY, KM, LW and JH collected and analysed the

data. ZY and LW wrote and revised the manuscript. YW and JH

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Weifang People's Hospital (Weifang, China; approval

no. WF202404001).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was provided by the patient

for the case report to be published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Lahey FH: Apathetic thyroidism. Ann Surg.

93:1026–1030. 1931.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Tsakiridis I, Giouleka S, Kourtis A,

Mamopoulos A, Athanasiadis A and Dagklis T: Thyroid disease in

pregnancy: A descriptive review of guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv.

77:45–62. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wiersinga WM, Poppe KG and Effraimidis G:

Hyperthyroidism: Aetiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, management,

complications, and prognosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

11:282–298. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Galindo RJ, Hurtado CR, Pasquel FJ, García

Tome R, Peng L and Umpierrez GE: National trends in incidence,

mortality, and clinical outcomes of patients hospitalized for

thyrotoxicosis with and without thyroid storm in the United States,

2004-2013. Thyroid. 29:36–43. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Akamizu T, Satoh T, Isozaki O, Suzuki A,

Wakino S, Iburi T, Tsuboi K, Monden T, Kouki T, Otani H, et al:

Diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and incidence of thyroid

storm based on nationwide surveys. Thyroid. 22:661–679.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Ono Y, Ono S, Yasunaga H, Matsui H,

Fushimi K and Tanaka Y: Factors associated with mortality of

thyroid storm: Analysis using a National inpatient database in

Japan. Medicine (Baltimore). 95(e2848)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Farooqi S, Raj S, Koyfman A and Long B:

High risk and low prevalence diseases: Thyroid storm. Am J Emerg

Med. 69:127–135. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Eskander A, de Almeida JR and Irish JC:

Acute upper airway obstruction. N Engl J Med. 381:1940–1949.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yoyo M: Medicine and society in

martinique. Interaction between society and medical practice. Union

Med Can. 109 (Suppl):S23–S27. 1980.PubMed/NCBI(In French).

|

|

10

|

Yildirim E: Principles of urgent

management of acute airway obstruction. Thorac Surg Clin.

28:415–428. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Chiha M, Samarasinghe S and Kabaker AS:

Thyroid storm: An updated review. J Intensive Care Med. 30:131–140.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

De Almeida R, McCalmon S and Cabandugama

PK: Clinical review and update on the management of thyroid storm.

Mo Med. 119:366–371. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Burch HB and Wartofsky L: Life-threatening

thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am.

22:263–277. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Satoh T, Isozaki O, Suzuki A, Wakino S,

Iburi T, Tsuboi K, Kanamoto N, Otani H, Furukawa Y, Teramukai S and

Akamizu T: 2016 Guidelines for the management of thyroid storm from

The Japan Thyroid Association and Japan Endocrine Society (First

edition). Endocr J. 63:1025–1064. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Matsushita A, Hosokawa S, Mochizuki D,

Okamura J, Funai K and Mineta H: Emergent thyroidectomy with

sternotomy due to acute respiratory failure with severe thyroid

storm. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 100:e1–e3. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|