Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) can be a fatal, and

chronic infection caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or

hepatitis C virus (HCV) is usually related to hepatocarcinogenesis.

Globally, HBV carriers are estimated to total 3 million, and

approximately 1 million people suffer from HBV-related HCC

(1). HBV is an oncogenic virus

which integrates with the genome of hepatocytes. The quantity of

HBV-DNA is strongly associated with the generation of HCC (2,3).

In general, the diagnosis of HBV infection is based

on the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the

serum. However, it was recently reported that HBV-DNA is

periodically detected in the serum or liver and is recognized as

occult HBV infection (4,5). In particular, HBcAb positivity is

thought to be a latent risk factor for hepatocarcinogenesis, since

the covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) of HBV is responsible

for the persistent HBV infection of hepatocytes in these cases

(6,7).

In order to examine the clinical characteristics of

HCC negative for HBsAg and the anti-hepatitis C virus antibody

(HCV-Ab) (NBNC-HCC) and HBV-DNA in relation to hepatocarcinogenesis

in NBNC-HCC, 32 cases of resected HCC were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

Thirty-two cases of HCC (26 males and 6 females,

median age 65.7 years) that underwent surgical resection in Kobe

University and related hospitals were enrolled in this study.

Clinical characteristics including age, gender, biochemical data

and surrounding liver tissues were examined. Histological features

were graded according to the New Inuyama Classification (8).

Analysis of occult HBV infection

To examine occult HBV infection in HBsAg-negative

cases, DNA was extracted in 12 cases from surrounding liver tissues

using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan). The detection

of HBV-DNA was carried out by employing PCR analysis using specific

primers (9,10). PCR products were directly sequenced

using an ABI PRISM® 3100 Avant Genetic Analyzer

(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and nucleotide

alignment using 20 reference strains was performed with Clustal X

software. The HBV genotype was determined by phylogenetic analysis

using the Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis 4 (MEGA4)

software program (available at http://www.megasoftware.net) (11).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using JMP7

software (SAS Institute Japan, Co., Ltd.). P<0.05 was considered

significant.

Results

Clinical data

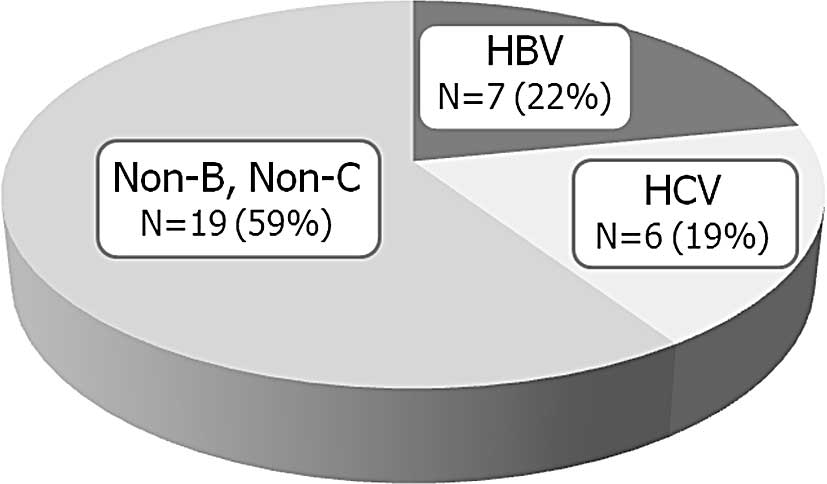

The etiology of the HCC cases is illustrated in

Fig. 1. Seven cases (22%) were

positive for HBsAg, 6 (19%) were positive for HCV-Ab and 19 (59%)

were negative for both HBsAg and HCV-Ab. Clinical data in the

hepatitis virus-related HCC (HV-HCC) cases were compared with those

in NBNC-HCC (Table I). The

activity and fibrosis scores of the background liver tissues in

HV-HCC were higher than those in NBNC-HCC. The average diameter of

the cancer in HV-HCC was smaller than that in NBNC-HCC.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of NBNC-HCC

and hepatitis virus-related HCC. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of NBNC-HCC

and hepatitis virus-related HCC.

| NBNC-HCC | HV-HCC | P-value |

|---|

| Cases (no.) | 19 | 13 | |

| Age (years) | 68.70±8.27 | 61.40±14.50 | 0.0794 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 74.70±36.20 | 48.80±29.60 | 0.0415a |

| Activity | 0.50±0.514 | 1.090±0.302 | 0.0019a |

| Fibrosis | 1.53±1.81 | 3.000±0.444 | 0.0061a |

| PLT

(×104/μl) | 20.40±9.80 | 15.90±8.01 | 0.1849 |

| ALT (IU/l) | 41.40±28.20 | 46.50±26.50 | 0.6151 |

| AFP (ng/ml) | 1,302±3,988 | 13,508±24,412 | 0.0984 |

| PIVKA-II

(mAU/ml) | 16,672±36,142 | 923±1,250 | 0.0738 |

Occult HBV infection in NBNC-HCC

To examine occult HBV infection, HBV-DNA was

assessed by PCR analysis from extracted liver tissue in NBNC-HCC.

The total characteristics of occult HBV were clinically compared

with those of non-occult HBV cases (Table II). No significant difference,

excluding the indocyanine green test, was detected between the two

groups.

| Table II.Clinical data of NBNC-HCC between

occult HBV-infected cases and others. |

Table II.

Clinical data of NBNC-HCC between

occult HBV-infected cases and others.

| Occult HBV in

NBNC-HCC | Non-occult HBV in

NBNC-HCC | P-value |

|---|

| Cases (no.) | 7 | 12 | |

| Age (years) | 65.7±11.4 | 70.10±6.45 | 0.2925 |

| Tumor size (mm) | 84.7±46.3 | 70.2±10.2 | 0.4335 |

| Activity | 0.20±0.22 | 0.615±0.137 | 0.1284 |

| Fibrosis | 1.170±0.672 | 1.540±0.457 | 0.6530 |

| PLT

(×104/μl) | 24.40±3.91 | 18.50±2.68 | 0.2341 |

| ALT (IU/l) | 38.5±33.0 | 42.8±27.2 | 0.7690 |

| ICG-R 15% (%) | 11.30±1.62 | 17.80±2.01 | 0.0199a |

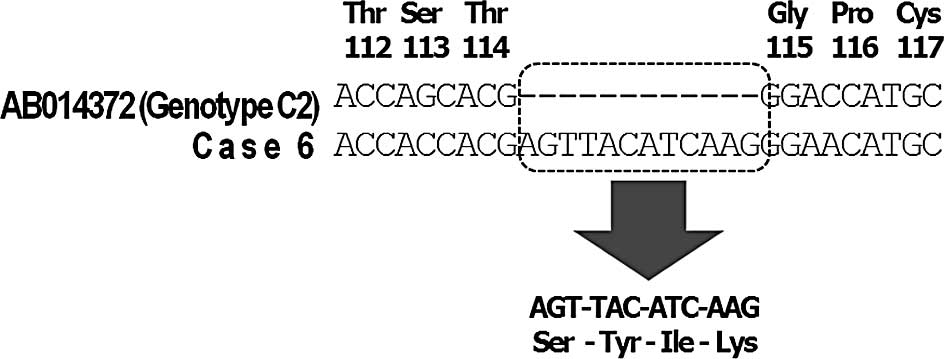

HBV-DNA in the pre-S/S region was amplified and

detected in 4 out of 7 cases (57%); the X region was detected in 4

cases (57%), and the core promoter/pre-core region was detected in

3 cases (43%). Mutation of codon 38 was detected in 1 case

(12,13). C1653T in the enhancer box α-region

was found in 3 out of 4 cases, and A1762T/G1764A in the basic core

promoter region was detected in all 4 cases (Table III). A 12-nucleotide insertion

(4-amino acid insertion) in the S region was noted in 1 case

(Fig. 2). Phylogenetic analysis

showed that all 4 cases were grouped into genotype C (Fig. 3).

| Table III.Mutation/variation of occult HBV

infection. |

Table III.

Mutation/variation of occult HBV

infection.

| Case no. | HBsAg | Pre-S/S | X region

| BCP region

|

|---|

| C1653T | T1753V | A1762T/G1764A |

|---|

| 2 | ND | ND | T | T | T/A |

| 3 | ND | ND | T | T | T/A |

| 5 | + | + | T | T | T/A |

| 6 | + | 4-AA insertion | ND | ND | ND |

| 11 | − | + | ND | ND | ND |

| 12 | ND | + | ND | ND | ND |

| 16 | + | ND | C | T | ND |

HBcAb was serologically examined in 12 out of 19

NBNC-HCC cases. Five out of 12 cases (42%) were positive for HBcAb,

which were thought to have been previously infected and resolved

naturally.

Discussion

Liver resection for HCC is a potentially curative

treatment. However, it has been reported that resection is possible

in only 30–35% of the HCC cases evaluated for surgical therapy due

to co-existing cirrhosis or the multicentric generation of HCC

(14). NBNC-HCC is estimated to

comprise 10% of HCC in Japanese patients. In this study, 19 out of

32 resected HCC cases (56%) were diagnosed as NBNC-HCC. It has been

suggested that cases of hepatic fibrosis of HCC with hepatitis

viral infection are usually more severe than those of NBNC-HCC. In

this study, HCC of more than 5 cm in diameter was present in 13 out

of 19 cases (68%) of NBNC-HCC. In addition, the average diameter of

NBNC-HCC was larger than that of HV-HCC. It is thought that HV-HCC

is diagnosed at an early stage, since patients with chronic

infection of hepatitis virus are regularly examined. It was

recently reported that the prevalence of non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis is increasing among NBNC-HCC cases (15). In this study, 5 cases (26%) showed

impaired glucose tolerance, and 3 cases (16%) were obese. Thus our

findings indicated that abnormal glucose tolerance was associated

with hepatocarcinogenesis in this study.

Occult HBV infection is diagnosed when HBsAg in

serum is negative and HBV-DNA in serum or liver is positive,

regardless of the positivity for anti-HBc. It is still

controversial whether or not occult HBV infection is associated

with liver damage. Althought it was reported that occult HBV

infection does not progress to severe liver disease (16), another study showed that occult HBV

infection caused liver disease progression in cases of chronic

infection of HCV (17,18). In this study, the activity and

fibrosis scores in the HCC cases with occult HBV infection were

lower than those in HV-HCC. Thus, our data indicated that occult

HBV infection is not related to the progression of liver disease.

As for hepatocarcinogenesis, it is also controversial whether or

not occult HBV infection is associated with HCC. Although it was

reported that occult HBV infection is an independent risk factor

for carcinogenesis in patients with HCV (19,20),

another study showed that occult HBV infection was not related to

hepatocarcinogenesis (21).

Several studies have demonstrated that the basic

core promoter region in the HBV genome is associated with

hepatocarcinogenesis (22,23). In Japan, it was reported that

C1653T and T1753V are associated with HCC (24,25).

Although T1753V was detected in only 1 case, C1653T and

A1762T/G1764A were relatively common in this study. It was also

reported that a mutation of the X region is associated with HCC

(12,13), but the codon 38 mutation was

detected in only 1 case and no mutation was found in codon 31 in

the present study. It is probable that the mutation/variation in

occult HBV infection in relation to HCC is different from that in

HBsAg-positive cases. A recent study showed that virological

factors of HBV related to HCC are different between occult

HBV-infected and HBsAg-positive patients, and G1721A, M1I and Q2K

in the pre-S2 gene might be useful viral markers for HCC in occult

HBV carriers (24).

In this study, a 12-nucleotide insertion (4-amino

acid insertion) between nt 114 and 115 in the S region was found in

1 case (Fig. 2). We considered

that the α-loop region in the S region was important for the

conformation of the S antigen, and amino acid substitutions at 122,

123, 126, 141 and 145 were found in the vaccine-escaping mutant. It

was possible that the insertion caused the conformational change to

the S antigen, and this resulted in the serological HBsAg

negativity in this case. It has also been reported that several

insertions in the HBx and Pre-S2 regions are associated with HCC

(25,26), but there were no such mutations

identified in this study.

In the present study, phylogenetic analysis revealed

that all cases of occult HBV infection were grouped into genotype

C. Since HBV genotype C is the most prevalent in Japanese patients,

it is reasonable that occult HBV in Japan is derived from genotype

C.

In conclusion, HBV-DNA was frequently found in the

NBNC-HCC tissues. No significant difference was noted between

occult HBV and other forms of infection among the NBNC-HCC cases.

Therefore, further investigation is necessary to assess whether

occult HBV infection is related to hepatocarcinogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a

grant-in-aid through the Program of Founding Research Centers for

Emerging and Reemerging Infectious Diseases, the Ministry of

Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT),

Japan.

References

|

1.

|

Lee WM: Hepatitis B virus infection. N

Engl J Med. 337:1733–1743. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Tang B, Kruger WD, Chen G, et al:

Hepatitis B viremia is associated with increased risk of

hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic carriers. J Med Virol.

72:35–40. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Harris RA, Chen G, Lin WY, Shen FM, London

WT and Evans AA: Spontaneous clearance of high-titer serum HBV DNA

and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population.

Cancer Causes Control. 14:995–1000. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Shih LN, Sheu JC, Wang JT, et al: Serum

hepatitis B virus DNA in healthy HBsAg-negative Chinese adults

evaluated by polymerase chain reaction. J Med Virol. 32:257–260.

1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Marusawa H, Uemoto S, Hijikata M, et al:

Latent hepatitis B virus infection in healthy individuals with

antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. Hepatology. 31:488–495.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Tuttleman JS, Pourcel C and Summers J:

Formation of the pool of covalently closed circular viral DNA in

hepadnavirus-infected cells. Cell. 47:451–460. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Seeger C and Mason WS: Hepatitis B virus

biology. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 64:51–68. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8.

|

Ichida F, Tsuji T, Omata M, et al: New

Inuyama Classification; new criteria for histological assessment of

chronic hepatitis. Int Hepatol Commun. 6:112–119. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9.

|

Sugauchi F, Mizokami M, Orito E, et al: A

novel variant genotype C of hepatitis B virus identified in

isolates from Australian Aborigines: complete genome sequence and

phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 82:883–892. 2001.

|

|

10.

|

Sugauchi F, Ohno T, Orito E, et al:

Influence of hepatitis B virus genotypes on the development of preS

deletions and advanced liver disease. J Med Virol. 70:537–544.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M and Kumar S:

MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software

version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 24:1596–1599. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Yeh CT, Shen CH, Tai DI, Chu CM and Liaw

YF: Identification and characterization of a prevalent hepatitis B

virus X protein mutant in Taiwanese patients with hepatocellular

carcinoma. Oncogene. 19:5213–5220. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Muroyama R, Kato N, Yoshida H, et al:

Nucleotide change of codon 38 in the X gene of hepatitis B virus

genotype C is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 45:805–812. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Sotiropoulos GC, Lang H, Frilling A, et

al: Resectability of hepatocellular carcinoma: evaluation of 333

consecutive cases at a single hepatobiliary specialty center and

systematic review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology.

53:322–329. 2006.

|

|

15.

|

Hatanaka K, Kudo M, Fukunaga T, et al:

Clinical characteristics of NonBNonC-HCC: comparison with HBV and

HCV-related HCC. Intervirology. 50:24–31. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY and Chen DS:

Occult hepatitis B virus infection and clinical outcomes of

patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Microbiol. 40:4068–4071.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Mrani S, Chemin I, Menouar K, et al:

Occult HBV infection may represent a major risk factor of

non-response to antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C. J Med

Virol. 79:1075–1081. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Tamori A, Nishiguchi S, Kubo S, et al:

Possible contribution to hepatocarcinogenesis of X transcript of

hepatitis B virus in Japanese patients with hepatitis C virus.

Hepatology. 29:1429–1434. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Pollicino T, Squadrito G, Cerenzia G, et

al: Hepatitis B virus maintains its pro-oncogenic properties in the

case of occult HBV infection. Gastroenterology. 126:102–110. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Tamori A, Hayashi T, Shinzaki M, et al:

Frequent detection of hepatitis B virus DNA in hepatocellular

carcinoma of patients with sustained virologic response for

hepatitis C virus. J Med Virol. 81:1009–1014. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Kusakabe A, Tanaka Y, Orito E, et al: A

weak association between occult HBV infection and non-B non-C

hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 42:298–305.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Kim JK, Chang HY, Lee JM, et al: Specific

mutations in the enhancer II/core promoter/precore regions of

hepatitis B virus subgenotype C2 in Korean patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Virol. 81:1002–1008. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Kao JH, Chen PJ, Lai MY and Chen DS: Basal

core promoter mutations of hepatitis B virus increase the risk of

hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B carriers. Gastroenterology.

124:327–334. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Shinkai N, Tanaka Y, Ito K, et al:

Influence of hepatitis B virus X and core promoter mutations on

hepatocellular carcinoma among patients infected with subgenotype

C2. J Clin Microbiol. 45:3191–3197. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Tanaka Y, Mukaide M, Orito E, et al:

Specific mutations in enhancer II/core promoter of hepatitis B

virus subgenotypes C1/C2 increase the risk of hepatocellular

carcinoma. J Hepatol. 45:646–653. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Chen CH, Changchien CS, Lee CM, et al: A

study on sequence variations in pre-S/surface, X and enhancer

II/core promoter/precore regions of occult hepatitis B virus in

non-B, non-C hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Taiwan. Int J

Cancer. 125:621–629. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Tabor E: Pathogenesis of hepatitis B

virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Res. 37:110–114.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Lupberger J and Hildt E: Hepatitis B

virus-induced oncogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 13:74–81. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|