Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) affects approximately

130–170 million people worldwide (1), however, no vaccines are available.

It is an important cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis,

hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), leading to a need for liver

transplantation (2,3). Treatment of chronic HCV is currently

based on the combination of pegylated interferon (IFN)-α and the

nucleotide analogue ribavirin, which is only effective in

approximately 50% of the patients, especially in HCV genotype 1

(4,5). HCV belongs to the Hepacivirus

genus within the Flaviviridae family, and is a

positive-stranded RNA virus with a genome of ∼9.6 kb. The HCV

genome contains a single open reading frame (ORF) encoding a large

polyprotein precursor of 3011 amino acids. The ORF is flanked by 5′

and 3′ untranslated regions. The precursor polyprotein is processed

by cellular and viral proteases into 10 proteins: structural (core,

E1 and E2), and non-structural proteins (p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B,

NS5A and NS5B) (3,6). There are six major genotypes in HCV

classification (3). The major

prevalent type in Southern Taiwan is HCV 1b, which is the most

resistant type to interferon therapy (5,7).

Curcumin, derived from eastern traditional

medicines, Curcuma longa, has been found to have a variety

of beneficial properties, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant,

chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activities (8,9).

Its multiple-target characteristics influence several activities of

intracellular molecules, including transcription nuclear factor-κB

(NF-κB), pro-inflammatory cyclooxygenase-2 and MAPK inhibitions, as

well as heme oxygenase-1 induction (9). In the antivirus bioactivity, certain

reports have indicated that curcumin showed anti-viral activity

against the human immunodeficiency (10,11), the coxsackie- (12) and the hepatitis B (HBV) viruses

(13). In the anti-HCV study, one

report showed that curcumin inhibited a lipogenic transcription

factor, sterol regulatory element binding protein-1

(SREBP-1)-induced HCV replication via the inhibition of the

PI3K-AKT pathway (14).

The catabolism of heme by heme oxygenase (HO)

resulted in the production of biliverdin, carbon monoxide and free

iron. HO-1, one of the phase II enzymes, is an enzyme in cells with

cytoprotective properties against oxidative damage (15) that has been reported to be induced

by the Nrf2 transcription factor (16). Curcumin-induced HO-1 expression

was first found in human endothelial cells (17), suggesting that a low dose of

curcumin induced HO-1 expression, which provided an intrinsic

antioxidant ability. Curcumin also induced HO-1 expression in

mesangial (18) and liver cells

(19–21), as well as in macrophages (22,23). The induction or overexpression of

HO-1 has been shown to interfere with the replication of certain

viruses, such as the human immunodeficiency virus (24), the HBV (25) and the HCV (26–28).

The properties of the transcription factor NF-κB are

extensively exploited in cells (29). In general, NF-κB is of great

importance in signal transduction pathways involved in chronic and

acute inflammatory diseases, as well as various types of cancer,

therefore, it is a good target for cancer prevention (30). Various reports have demonstrated

the correlation between curcumin and NF-κB. One of those reports

suggests the anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin, which suppresses

the ox-LDL-induced MCP-1 expression via the p38 MAPK and NF-κB

pathways in rat vascular smooth muscle cells (31). The anti-inflammatory effect of

curcumin has been reported to be due to the IκB/NF-κB system in rat

and human intestinal epithelial cells, including IEC-6, HT-29 and

Caco-2 cells (32). Curcumin has

also been found to have anti-metastatic properties via the

inhibition of NF-κB in the highly invasive and metastatic

MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line (33). Another signaling pathway,

Raf/MEK/extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), is of crucial

importance in the regulation of cell growth, differentiation,

survival, as well as the transmission of oncogenic signals

(34). This pathway has also been

reported to be a target of curcumin. For example, curcumin

inhibited connective tissue growth factor gene expression by

suppressing ERK signaling in activated hepatic stellate cells

(35). Moreover, curcumin

inhibited phorbol myristate acetate-induced MCP-1 gene expression

by inhibiting ERK and NF-κB activities in U937 cells (36). However, the manner in which

curcumin affects the activities of NF-κB and ERK in HCV-infected

hepatoma cells has yet to be determine.

Only one study suggesting that curcumin inhibited

HCV replication by suppressing the AKT-SREBP-1 pathway is currently

available (14). In this study,

the correlation between curcumin-inhibited HCV replication, HO-1,

AKT, ERK and NF-κB molecules was examined.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

Huh7.5 cells expressing the HCV genotype 1b

subgenomic replicon (Con1/SG-Neo(I) hRlucFMDV2aUb) containing

Renilla luciferase reporter, kindly provided by Apath, were

cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml

streptomycin and 0.5 mg/ml G418. The nuclear extraction kit was

purchased from Chemicon (Temecula, CA, USA). Curcumin (Acros

Organics, Geel, Belgium), LY294002, U0126 and Ro1069920 were

purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK), and dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO), then added into culture medium containing 0.1%

DMSO.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by colorimetric MTT

assay. Cells were cultured on 24-well plates at a density of

1×105 cells/well. After 24 h, the cells were incubated

with varying concentrations of curcumin or 0.1% DMSO for another 24

h. MTT was added to medium for 2 h, the medium was discarded and

DMSO was then added to dissolve the formazan product. Each well was

measured by light absorbance at 490 nm. The result was expressed as

a percentage, relative to the 0.1% DMSO-treated control group.

Luciferase reporter assay

Cells were subcultured at a density of

4×105 cells/well in 1 ml of culture medium in a 12-well

plastic dish for 6 h. Curcumin or DMSO was added to the medium for

24 h. The cells were lysed and cell lysates were prepared for a

Renilla luciferase assay (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and

protein concentration assays, with Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad,

Hercules, CA, USA). The relative luciferase activities were

normalized to the same protein concentration.

Real-time RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from Huh7.5 cells expressing

the HCV genotype 1b subgenomic replicon. Reverse transcription (RT)

was performed on 2 μg of total RNA by 1.5 μM random hexamer and

RevertAid™ reverse transcriptase (Fermentas, Glen Burnie, MD, USA).

Then, 1/20 volume of reaction mixture was used for quantitative

real-time PCR with HCV specific primers: 5′-AGCGTCTAGCCATGGCGT-3′

and 5′-GGTGTACTCACCGGTTCCG-3′, and GAPDH specific primers:

5′-CGGATTTGGTCGTATTGG-3′ and 5′-AGATGGT GATGGGATTTC-3′, as the

endogenous control. The quantitative real-time PCR was followed by

Maxima™ SYBR-Green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas). Real-time PCR

reactions contained optimal volume of the reverse transcription

mixture, 600 nM each forward and reverse primer and 1X SYBR-Green

qPCR Master Mix in 25 μl. Reactions were incubated for 40 cycles in

an ABI GeneAmp® 7500 Sequence Detection System, with an

initial denaturization step at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 63°C for 1 min. PCR product

accumulation was monitored at several points during each cycle, by

measuring the increase in fluorescence. Gene expression changes

were assessed using the comparative Ct method. The relative amounts

of mRNA for HCV were optimized by subtracting the Ct values of HCV

from the Ct values of GAPDH mRNA (ΔCt). The ΔCt of the control

group was then subtracted from the ΔCt of the curcumin-treated

groups (ΔΔCt). Data were expressed as relative levels of HCV

RNA.

Western blotting

For western blotting, analytical 10% sodium dodecyl

sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide slab gel electrophoresis was

performed. Tissue extracts were prepared and a 30–60 μg aliquot of

protein extracts was analyzed. For immunoblotting, proteins in the

SDS-PAGE gels were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride

membrane using a trans-blot apparatus. Antibodies against HCV NS5A

and HCV NA5B (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA),

HO-1 (Assay Designs, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI, USA), pAKT (308) and pERK

(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), NF-κB (Cell Signaling Technology,

Beverly, MA, USA), Sp1 (Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), α-tubulin

(GeneTex, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) and β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA) were used as the primary antibodies. Mouse, rabbit

or goat IgG antibodies coupled with horseradish peroxidase were

used as the secondary antibodies. An enhanced chemiluminescence kit

and VL Chemi-Smart 3000 were used for detection, while the quantity

of each band was determined using MultiGauge software.

HO-1 knockdown by siRNA

Cells (3×106) were seeded in 10-cm dishes

for 6 h, then negative control small interfering (siRNA) (10 nM) or

HO-1 siRNA (10 nM) (Invitrogen) was transfected into cells using

the RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen), according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Subsequent to adding siRNA for 6 h,

the medium was changed to fresh condition medium for 18 h. Then the

transfected cells were then analyzed by western blotting.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical

evaluation was carried out by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn’s

test. All statistics were calculated using SigmaStat version 3.5

(Systat Software). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

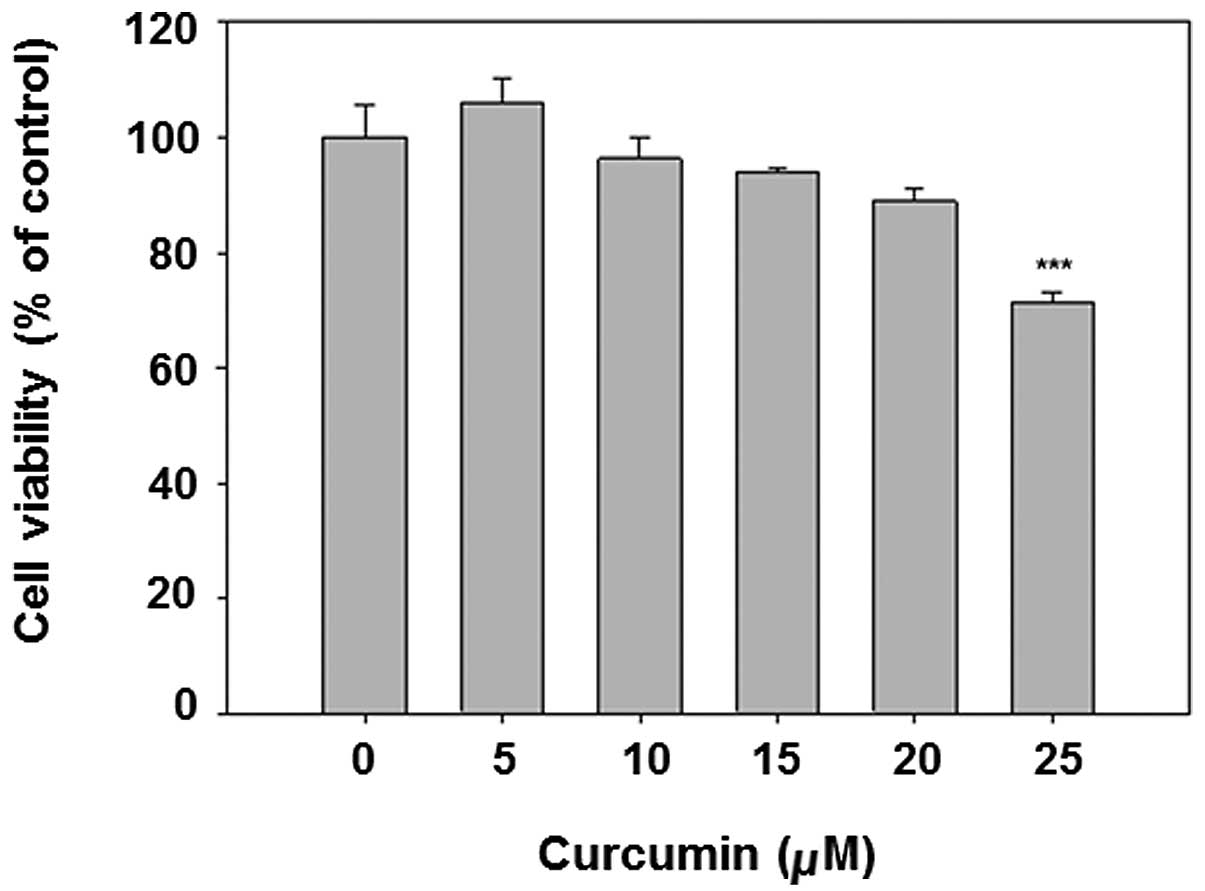

Cytotoxicity of curcumin in Huh7.5 cells

expressing the HCV genotype 1b subgenomic replicon (Huh7.5-HCV

cells)

Curcumin is known to be an anticancer chemical at

high doses. To avoid the obvious cytotocicity in the subsequent

experiments, the MTT assay was applied for cytotoxicity analysis.

The results show that curcumin dose-dependently decreased cell

viability (Fig. 1). The dose

<20 μM was selected for subsequent analysis, given that the

viability of 25 μM curcumin treatment is <80%.

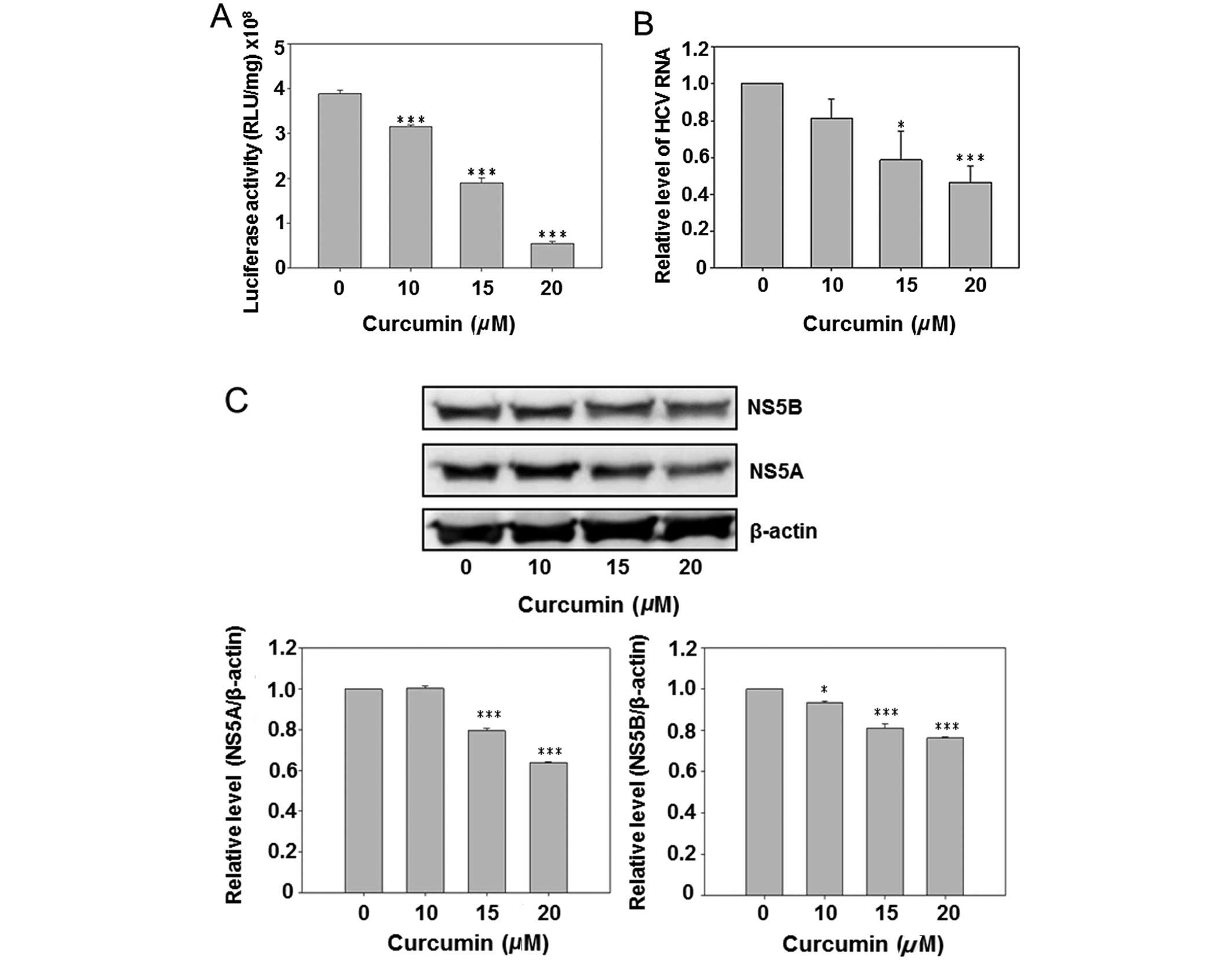

Curcumin reduced HCV replication and HCV

protein expression

Due to the presence of a luciferase reporter gene in

the HCV subgenomic replicon of Con1/SG-Neo(I)hRlucFMDV2aUb, the

culture medium luciferase activity was first analyzed subsequent to

curcumin treatment. The results show that curcumin dose-dependently

inhibited luciferase activity (Fig.

2A). However, the HCV RNA was also detected by real-time PCR.

Curcumin also reduced the intracellular HCV RNA expression in a

dose-dependent manner. Subsequent to curcumin treatment the

HCV-specific protein NS5A and NS5B were detected by western blot

analysis, indicating that curcumin dose-dependently inhibited

expression of the NS5A and NS5B. The above data suggest that

curcumin inhibited HCV replication in hepatoma cells.

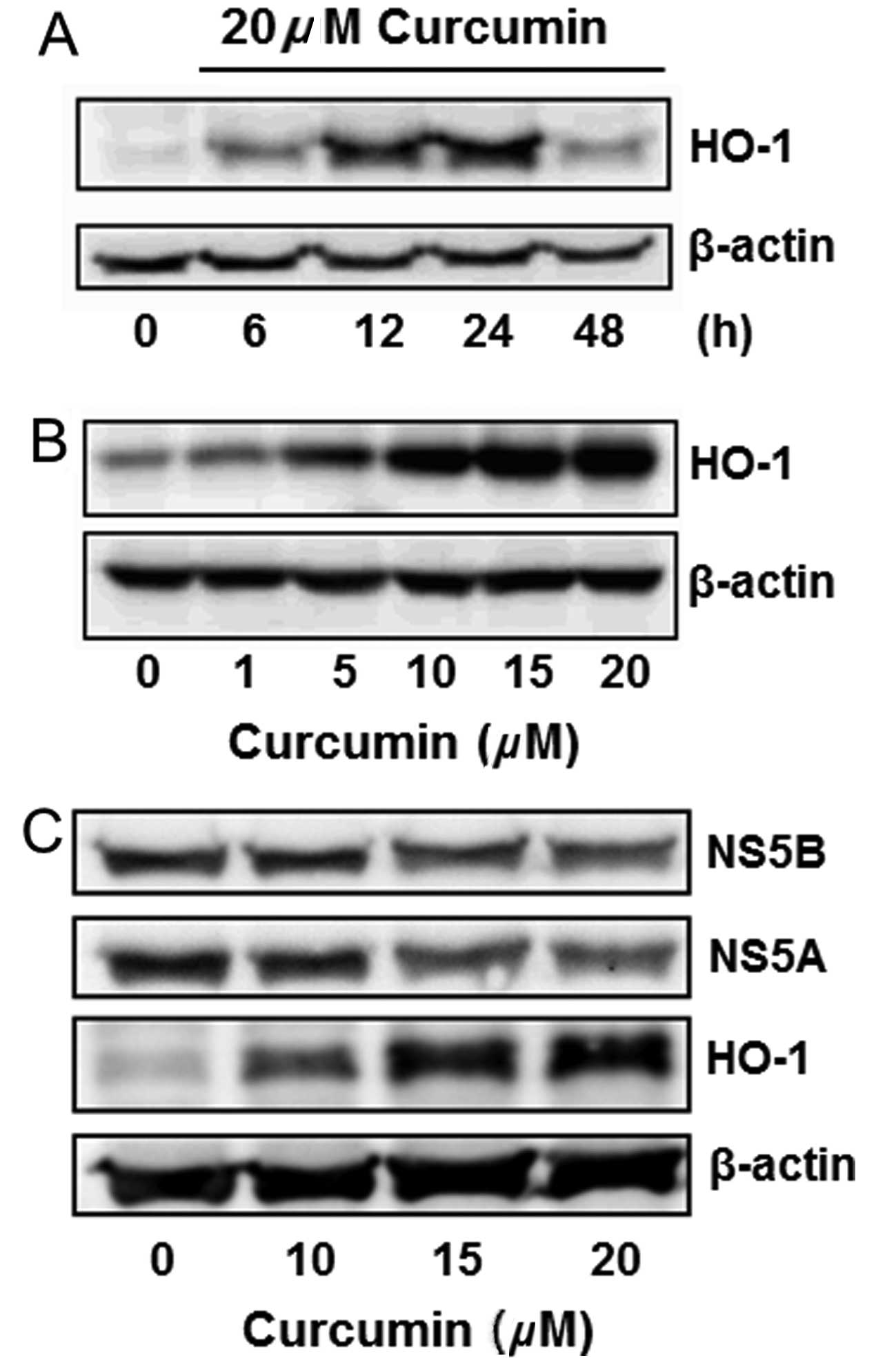

Curcumin induced HO-1 protein

expression

Curcumin is known to induce HO-1 expression in

various cells. This effect was analyzed in Huh7.5-HCV cells.

Curcumin slightly induced HO-1 expression in a 6-h treatment, while

significantly inducing it in 12 and 24 h. The HO-1 induction

declined after treatment for 48 h (Fig. 3A). Curcumin also induced HO-1

expression in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). The change of NS5A, NS5B and

HO-1 protein expressions was simultaneously detected by western

blot analysis, indicating that curcumin dose-dependently inhibited

the expression of NS5A and NS5B, while increasing the HO-1

expression (Fig. 3C).

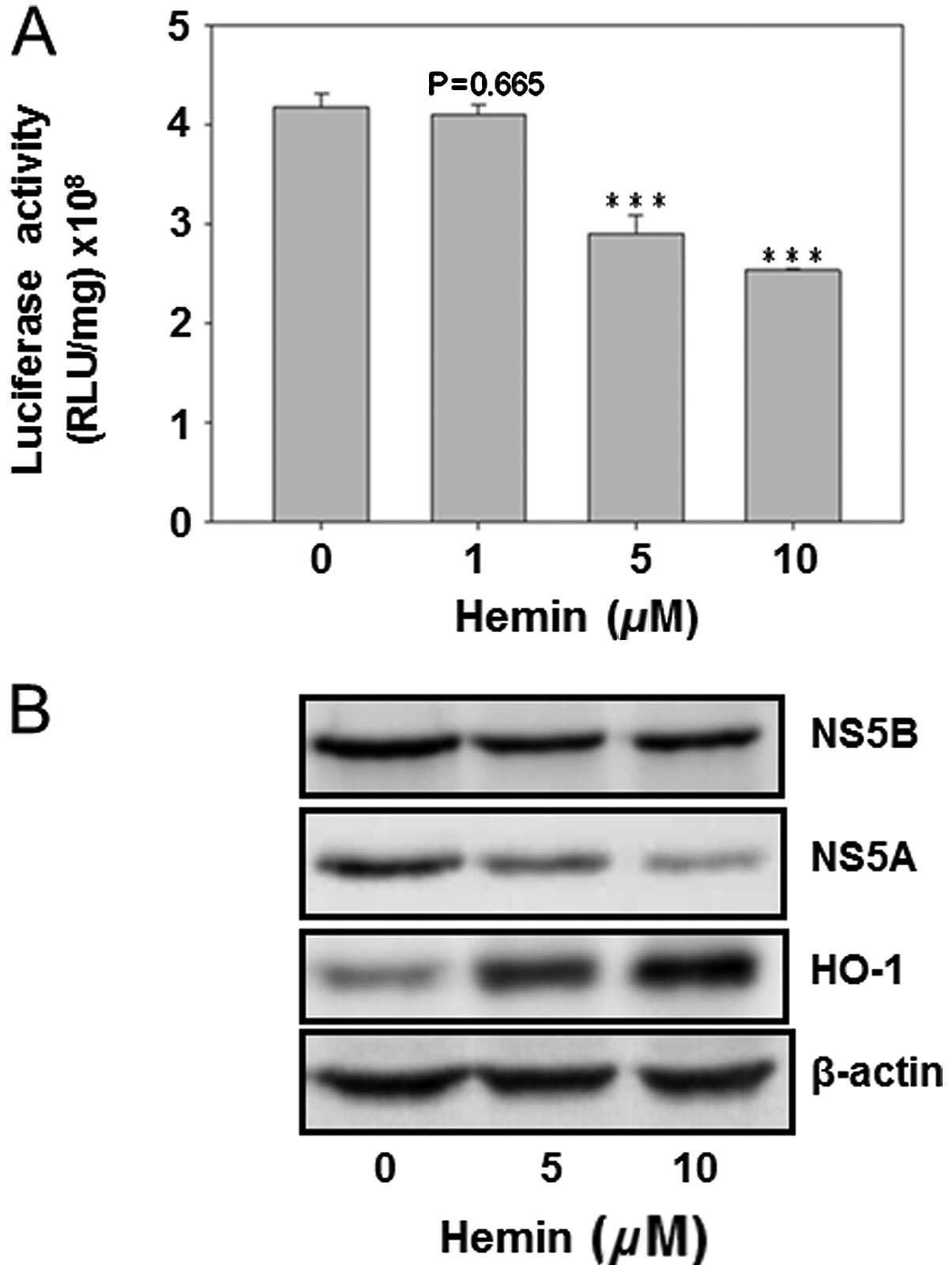

Hemin reduced HCV replication and the HCV

protein expression

The HO-1 inducer hemin was used to analyze its

effect on HCV replication as well as on the protein expression of

HCV NS5A and NS5B. The result showed that hemin dose-dependently

decreased HCV replication (Fig.

4A). Furthermore, curcumin inhibited the protein expression of

NS5A and NS5B, while enhancing the HO-1 protein expression. This

finding suggested that HO-1 protein inhibited HCV replication in

Huh7.5-HCV cells (Fig. 4).

HO-1 knockdown partially reversed the

curcumin-reduced viral protein expression

In order to prove the direct relationship between

curcumin-induced HO-1 and curcumin-inhibited HCV replication, the

HO-1 specific siRNA was used for analysis. HO-1 siRNA significantly

inhibited basal and curcumin-induced HO-1 expression (Fig. 5A). HO-1 knockdown slightly

increased the NS5A and NS5B protein expressions in the basal

condition. At the same time, it partially but significantly

reversed the curcumin-inhibited the expression of NS5A and NS5B,

suggesting that curcumin-induced HO-1 was involved in

curcumin-inhibited HCV replication, while having additional

mechanisms regarding the anti-HCV effect of curcumin.

| Figure 5.The role of HO-1, AKT, ERK and NF-κB

on curcumin-inhibited HCV protein expression is shown. (A)

Knockdown of HO-1 partially reversed curcumin-inhibited HCV protein

expression. Cells (3×106) were seeded in a 10-cm dish

for 6 h, and negative control small interfering (siRNA) (10 nM) or

HO-1 siRNA (10 nM) was transfected into cells. Subsequent to a 6-h

addition of siRNA, the medium was changed to fresh condition medium

for 18 h, and the transfected cells were analyzed by western

blotting (*P<0.05 and ***P<0.001, in 2 groups,

respectively). (B) Curcumin inhibited AKT, ERK and NF-κB. Cells

were subcultured at a density of 1.5×106 cells in 8 ml

of culture medium in a 10-cm plastic dish for 6 h. Curcumin or DMSO

was added to the medium for 24 h. Total cell lysates (up) or

cytosol-nuclear fraction (down) were isolated by western blot

analysis. Sp1 is a dominant nuclear protein and α-tubulin is a

cytosolic protein. (C) Effect of AKT, ERK and NF-κB inhibitors on

the HCV protein expression is shown. Cells were subcultured at a

density of 1.5×106 cells in 8 ml of culture medium in a

10-cm plastic dish for 6 h. Chemical (LY, LY294002; U0, U0126; Ro,

Ro1069920) or DMSO was added to the medium for 24 h. Total cell

lysates were isolated for western blot analysis.

(***P<0.001 compared to control). The experiments

were repeated three times. |

Effect of the PI3K-AKT, MEK-ERK and NF-κB

pathways on curcumin-inhibited HCV replication

Fig. 5A shows that

HO-1 is partially involved in curcumin-inhibited HCV replication.

Additional signaling pathways affected by curcumin were analyzed,

demonstrating that curcumin inhibited the protein phosphorylation

of ERK and AKT, as well as the cytoplasmic protein expression of

NF-κB (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the

specific inhibitors of PI3K-AKT (LY294002), MEK-ERK (U0126) and

NF-κB (Ro 106-9920) were used to identify the role of AKT, ERK and

NF-κB in the HCV protein expression. Fig. 5C shows that curcumin was the only

chemical to induce the HO-1 expression. Of the three inhibitors,

only PI3K-AKT LY294002 slightly inhibited the HCV protein

expression, while MEK-ERK U0126 and NF-κB inhibitors Ro 1069920 had

a slight effect on increasing the HCV protein expression,

suggesting that curcumin-inhibited HCV replication was also

partially mediated via PI3K-AKT inhibition.

Discussion

Curcumin is a common chemical ingredient of curry.

It has, however, been studied in clinical trials regarding its

applicability in treating patients suffering from pancreatic and

colon cancer, as well as multiple myeloma (37). In Taiwan, several doctors of

traditional Chinese medicine consider curcumin to be beneficial for

patients suffering from hepatitis. The results of this study

demonstrate that curcumin inhibits HCV replication in cellular

analysis, and its mechanism partially occurs through HO-1 induction

and PI3K-AKT inhibition.

HO-1, a curcumin-induced gene, is thought to be a

potential therapeutic protein for the re-establishment of

homeostasis in several pathologic conditions (38) and is also involved in inhibiting

HCV replication (28). The HO-1

products biliverdin and iron contribute to certain anti-HCV

mechanisms of HO-1 (26,39,40). In this study, HO-1 knockdown

partially reversed curcumin-inhibited HCV replication, supporting

the evidence for the anti-HCV effect of HO-1. Since HO-1 is induced

by ROS or certain electrophiles, ROS has also been reported to

inhibit HCV replication (41,42). Arsenic trioxide-inhibited HCV

replication is also suggested to be mediated through the induction

of oxidative stress (43). HO-1,

an oxidative stress-induced gene, may be involved in the

ROS-inhibited HCV replication.

As a downstream kinase of PI3K, AKT is an important

molecule in regulating a wide range of signaling pathways (44). In HCV-infected cells, the PI3K-AKT

signaling pathway is involved in certain pathological mechanisms.

For example, the activities of PI3K, AKT and their downstream

target mTOR are increased in the HCV-replicating cells (45). HCV NS5A binds to PI3K, while

enhancing the phosphotransferase activity of the catalytic domain

(46). The HCV-activated PI3K-AKT

contributes to cell survival enhancement. In addition to cell

survival, AKT leads to the protein accumulation of SREBP-1, an

important transcription factor regulating genes involved in fatty

acid and cholesterol synthesis (47). HCV NS4B has been found to enhance

the protein expression levels of SREBPs and fatty acid synthase

through PI3K activity, subsequently inducing a lipid accumulation

in hepatoma cells (48).

Therefore, inhibition of the PI3K-SREBP signaling pathway should

decrease the HCV-induced HCC development and the cellular fatty

acid level. Curcumin has been reported to inhibit HCV replication

via suppression of the AKT-SREBP-1 pathway (14). In the present study, data also

demonstrated that curcumin-inhibited PI3K-AKT was slightly involved

in the anti-HCV activity of curcumin.

Activation of the MEK-ERK signal cascade enhances

the replication of viruses, such as the human immunodeficiency

(49), the influenza (50), the corona- (51) and the herpes simplex viruses

(52). By contrast, in the case

of HBV, activation of MEK-ERK signaling led to the inhibition of

HBV replication (53). In the HCV

study, interleukin-1 has been reported to have the potential to

effectively inhibit HCV replication and protein expression by

activating the ERK signaling pathway (54). HCV IRES-dependent protein

synthesis was enhanced by MEK-ERK inhibitor PD98059 (55). Another report also suggests that

inhibition of MEK-ERK signaling leads to the upregulation of HCV

replication and protein production (56). Consistent with the results of the

present study, those findings confirm that the curcumin-inhibited

MEK-ERK signaling pathway contributes to the increase of HCV

replication.

NF-κB, one of the major signaling transduction

molecules activated in response to oxidative stress, is able to

modulate the transcription of a large number of downstream genes.

The HCV core protein has been shown to activate NF-κB, inducing

resistance to TNF-α-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells (57). HCV NS2 activates the IL-8 gene

expression by activating the NF-κB pathway in HepG2 cells (58). In the infectious JFH1 model, HCV

is suggested to enhance hepatic fibrosis progression through the

induction of TGF-β1, mediated by a ROS-induced and NF-κB-dependent

pathway (59). These evidences

indicate that the activation of NF-κB by HCV induces hepatic

disease progression. In this study, the NF-κB expression is

abundant in the cytoplasm of Huh7.5 cells, expressing the HCV

genotype 1b subgenomic replicon (Fig.

5B). The absence of NF-κB nuclear translocation indicates that

NF-κB is not likely to participate in the mechanism of

hepatocarcinogenesis in this cell line. The absense of complete HCV

core and HCV NS2 sequences in the subgenomic replicon used in this

study, is likely to be the reason for the absence of NF-κB nuclear

translocation. Therefore, it is likely to contribute to the

inability of the NF-κB inhibitor to suppress the HCV protein

expression in this cell line. In fact, the genomic variation of HCV

core protein generates a distinct functional regulation of NF-κB,

which may inhibit or activate NF-κB activity (60).

In certain reports, the inhibition of NF-κB shows

anti-HCV activity: for example, the Acacia confusa (61) and San-Huang-Xie-Xin-Tang extracts

(62) suppress HCV replication

associated with NF-κB inhibition. In the present study,

curcumin-inhibited NF-κB does not have any benefit in anti-HCV

activity. Thus, the presence or absence of the inhibition of NF-κB

in anti-HCV therapy is likely to depend on the activation status of

NF-κB, although additional investigations are required on the

subject.

In conclusion, this study proved that curcumin

inhibits HCV replication through the induction of the HO-1

expression and the inhibition of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway.

However, the curcumin-inhibited MEK-ERK mechanism contributes

negatively to its anti-HCV activity.

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by grants from

the National Science Council (NSC98-2320-B-415-002-MY3) and from

the Chiayi Christian Hospital, Taiwan.

References

|

1.

|

D LavanchyThe global burden of hepatitis

CLiver Int29Suppl 1S74S81200910.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01934.x

|

|

2.

|

N BostanT MahmoodAn overview about

hepatitis C: a devastating virusCrit Rev

Microbiol3691133201010.3109/1040841090335745520345213

|

|

3.

|

D MoradpourF PeninCM RiceReplication of

hepatitis C virusNat Rev

Microbiol5453463200710.1038/nrmicro1645

|

|

4.

|

JJ FeldJH HoofnagleMechanism of action of

interferon and ribavirin in treatment of hepatitis

CNature436967972200510.1038/nature0408216107837

|

|

5.

|

S MunirS SaleemM IdreesHepatitis C

treatment: current and future perspectivesVirol

J7296201010.1186/1743-422X-7-29621040548

|

|

6.

|

BD LindenbachCM RiceUnravelling hepatitis

C virus replication from genome to

functionNature436933938200510.1038/nature0407716107832

|

|

7.

|

CM LeeCH HungSN LuViral etiology of

hepatocellular carcinoma and HCV genotypes in

TaiwanIntervirology497681200610.1159/00008726716166793

|

|

8.

|

H HatcherR PlanalpJ ChoFM TortiSV

TortiCurcumin: from ancient medicine to current clinical trialsCell

Mol Life Sci6516311652200810.1007/s00018-008-7452-418324353

|

|

9.

|

A GoelAB KunnumakkaraBB AggarwalCurcumin

as ‘Curecumin’: from kitchen to clinicBiochem

Pharmacol757878092008

|

|

10.

|

CJ LiLJ ZhangBJ DezubeCS CrumpackerAB

PardeeThree inhibitors of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus long

terminal repeat-directed gene expression and virus replicationProc

Natl Acad Sci USA9018391842199310.1073/pnas.90.5.18398446597

|

|

11.

|

A MazumderK RaghavanJ WeinsteinKW KohnY

PommierInhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 integrase

by curcuminBiochem

Pharmacol4911651170199510.1016/0006-2952(95)98514-A7748198

|

|

12.

|

X SiY WangJ WongJ ZhangBM McManusH

LuoDysregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system by curcumin

suppresses coxsackievirus B3 replicationJ

Virol8131423150200710.1128/JVI.02028-0617229707

|

|

13.

|

MM RechtmanO Har-NoyI Bar-YishayCurcumin

inhibits hepatitis B virus via down-regulation of the metabolic

coactivator PGC-1alphaFEBS

Lett58424852490201010.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.06720434445

|

|

14.

|

K KimKH KimHY KimHK ChoN SakamotoJ

CheongCurcumin inhibits hepatitis C virus replication via

suppressing the Akt-SREBP-1 pathwayFEBS

Lett584707712201010.1016/j.febslet.2009.12.01920026048

|

|

15.

|

LE OtterbeinMP SoaresK YamashitaFH

BachHeme oxygenase-1: unleashing the protective properties of

hemeTrends

Immunol24449455200310.1016/S1471-4906(03)00181-912909459

|

|

16.

|

TO KhorMT HuangKH KwonJY ChanBS ReddyAN

KongNrf2-deficient mice have an increased susceptibility to dextran

sulfate sodium-induced colitisCancer

Res661158011584200610.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-356217178849

|

|

17.

|

R MotterliniR ForestiR BassiCJ

GreenCurcumin, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent, induces

heme oxygenase-1 and protects endothelial cells against oxidative

stressFree Radic Biol

Med2813031312200010.1016/S0891-5849(00)00294-X10889462

|

|

18.

|

J GaedekeNA NobleWA BorderCurcumin blocks

fibrosis in anti-Thy 1 glomerulonephritis through up-regulation of

heme oxygenase 1Kidney

Int6820422049200510.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00658.x16221204

|

|

19.

|

SJ McNallyEM HarrisonJA RossOJ GardenSJ

WigmoreCurcumin induces heme oxygenase-1 in hepatocytes and is

protective in simulated cold preservation and warm reperfusion

injuryTransplantation81623626200610.1097/01.tp.0000184635.62570.1316495813

|

|

20.

|

W BaoK LiS RongCurcumin alleviates

ethanol-induced hepatocytes oxidative damage involving heme

oxygenase-1 inductionJ

Ethnopharmacol128549553201010.1016/j.jep.2010.01.02920080166

|

|

21.

|

EO FarombiS ShrotriyaHK NaSH KimYJ

SurhCurcumin attenuates dimethylnitrosamine-induced liver injury in

rats through Nrf2-mediated induction of heme oxygenase-1Food Chem

Toxicol4612791287200810.1016/j.fct.2007.09.09518006204

|

|

22.

|

KM KimHO PaeM ZhungInvolvement of

anti-inflammatory heme oxygenase-1 in the inhibitory effect of

curcumin on the expression of pro-inflammatory inducible nitric

oxide synthase in RAW264.7 macrophagesBiomed

Pharmacother62630636200810.1016/j.biopha.2008.01.00818325727

|

|

23.

|

HY HsuLC ChuKF HuaLK ChaoHeme oxygenase-1

mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of Curcumin within

LPS-stimulated human monocytesJ Cell

Physiol215603612200810.1002/jcp.2120618357586

|

|

24.

|

K DevadasS DhawanHemin activation

ameliorates HIV-1 infection via heme oxygenase-1 inductionJ

Immunol17642524257200610.4049/jimmunol.176.7.425216547262

|

|

25.

|

U ProtzerS SeyfriedM QuasdorffAntiviral

activity and hepatoprotection by heme oxygenase-1 in hepatitis B

virus

infectionGastroenterology13311561165200710.1053/j.gastro.2007.07.02117919491

|

|

26.

|

E LehmannWH El-TantawyM OckerThe heme

oxygenase 1 product biliverdin interferes with hepatitis C virus

replication by increasing antiviral interferon

responseHepatology51398404201010.1002/hep.2333920044809

|

|

27.

|

Y ShanJ ZhengRW LambrechtHL

BonkovskyReciprocal effects of micro-RNA-122 on expression of heme

oxygenase-1 and hepatitis C virus genes in human

hepatocytesGastroenterology13311661174200710.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.00217919492

|

|

28.

|

Z ZhuAT WilsonMM MathahsHeme oxygenase-1

suppresses hepatitis C virus replication and increases resistance

of hepatocytes to oxidant

injuryHepatology4814301439200810.1002/hep.2249118972446

|

|

29.

|

V TergaonkarNFkappaB pathway: a good

signaling paradigm and therapeutic targetInt J Biochem Cell

Biol3816471653200610.1016/j.biocel.2006.03.02316766221

|

|

30.

|

S LuqmanJM PezzutoNFkappaB: a promising

target for natural products in cancer chemopreventionPhytother

Res24949963201020577970

|

|

31.

|

Y ZhongT LiuZ GuoCurcumin inhibits

ox-LDL-induced MCP-1 expression by suppressing the p38MAPK and

NF-kappaB pathways in rat vascular smooth muscle cellsInflamm

Res616167201210.1007/s00011-011-0389-322005927

|

|

32.

|

C JobinCA BradhamMP RussoCurcumin blocks

cytokine-mediated NF-kappa B activation and proinflammatory gene

expression by inhibiting inhibitory factor I-kappa B kinase

activityJ Immunol16334743483199910477620

|

|

33.

|

AC BhartiN DonatoS SinghBB

AggarwalCurcumin (diferuloylmethane) down-regulates the

constitutive activation of nuclear factor-kappa B and IkappaBalpha

kinase in human multiple myeloma cells, leading to suppression of

proliferation and induction of

apoptosisBlood10110531062200310.1182/blood-2002-05-1320

|

|

34.

|

GL JohnsonR LapadatMitogen-activated

protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein

kinasesScience29819111912200210.1126/science.107268212471242

|

|

35.

|

A ChenS ZhengCurcumin inhibits connective

tissue growth factor gene expression in activated hepatic stellate

cells in vitro by blocking NF-kappaB and ERK signallingBr J

Pharmacol153557567200810.1038/sj.bjp.070754217965732

|

|

36.

|

JH LimTK KwonCurcumin inhibits phorbol

myristate acetate (PMA)-induced MCP-1 expression by inhibiting ERK

and NF-kappaB transcriptional activityFood Chem

Toxicol484752201010.1016/j.fct.2009.09.01319766691

|

|

37.

|

A ShehzadF WahidYS LeeCurcumin in cancer

chemo-prevention: molecular targets, pharmacokinetics,

bioavailability, and clinical trialsArch

Pharm343489499201010.1002/ardp.20090031920726007

|

|

38.

|

MP SoaresFH BachHeme oxygenase-1: from

biology to therapeutic potentialTrends Mol

Med155058200910.1016/j.molmed.2008.12.00419162549

|

|

39.

|

Z ZhuAT WilsonBA LuxonBiliverdin inhibits

hepatitis C virus nonstructural 3/4A protease activity: mechanism

for the antiviral effects of heme

oxygenase?Hepatology5218971905201010.1002/hep.2392121105106

|

|

40.

|

C FillebeenK PantopoulosIron inhibits

replication of infectious hepatitis C virus in permissive Huh7.5.1

cellsJ Hepatol53995999201010.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.04420813419

|

|

41.

|

J ChoiKJ LeeY ZhengAK YamagaMM LaiJH

OuReactive oxygen species suppress hepatitis C virus RNA

replication in human hepatoma

cellsHepatology398189200410.1002/hep.2000114752826

|

|

42.

|

M YanoM IkedaK AbeOxidative stress induces

anti-hepatitis C virus status via the activation of extracellular

signal-regulated

kinaseHepatology50678688200910.1002/hep.2302619492433

|

|

43.

|

M KurokiY AriumiM IkedaH DansakoT WakitaN

KatoArsenic trioxide inhibits hepatitis C virus RNA replication

through modulation of the glutathione redox system and oxidative

stressJ Virol8323382348200910.1128/JVI.01840-0819109388

|

|

44.

|

DP BrazilZZ YangBA HemmingsAdvances in

protein kinase B signalling: AKTion on multiple frontsTrends

Biochem Sci29233242200410.1016/j.tibs.2004.03.00615130559

|

|

45.

|

P MannovaL BerettaActivation of the

N-Ras-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway by hepatitis C virus: control of cell

survival and viral replicationJ

Virol7987428749200510.1128/JVI.79.14.8742-8749.200515994768

|

|

46.

|

A StreetA MacdonaldK CrowderM HarrisThe

Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein activates a phosphoinositide

3-kinase-dependent survival signaling cascadeJ Biol

Chem2791223212241200410.1074/jbc.M31224520014709551

|

|

47.

|

T PorstmannB GriffithsYL ChungPKB/Akt

induces transcription of enzymes involved in cholesterol and fatty

acid biosynthesis via activation of

SREBPOncogene2464656481200516007182

|

|

48.

|

CY ParkHJ JunT WakitaJH CheongSB

HwangHepatitis C virus nonstructural 4B protein modulates sterol

regulatory element-binding protein signaling via the AKT pathwayJ

Biol Chem28492379246200910.1074/jbc.M80877320019204002

|

|

49.

|

D Yangxand GabuzdaRegulation of human

immunodeficiency virus type 1 infectivity by the ERK

mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathwayJ

Virol7334603466199910074203

|

|

50.

|

S PleschkaT WolffC EhrhardtInfluenza virus

propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling

cascadeNat Cell Biol3301305200110.1038/3506009811231581

|

|

51.

|

Y CaiY LiuX ZhangSuppression of

coronavirus replication by inhibition of the MEK signaling pathwayJ

Virol81446456200710.1128/JVI.01705-0617079328

|

|

52.

|

KD SmithJJ MezhirK BickenbachActivated MEK

suppresses activation of PKR and enables efficient replication and

in vivo oncolysis by Deltagamma(1)34.5 mutants of herpes simplex

virus 1J

Virol8011101120200610.1128/JVI.80.3.1110-1120.200616414988

|

|

53.

|

Y ZhengJ LiDL JohnsonJH OuRegulation of

hepatitis B virus replication by the ras-mitogen-activated protein

kinase signaling pathwayJ

Virol7777077712200310.1128/JVI.77.14.7707-7712.200312829809

|

|

54.

|

H ZhuC LiuInterleukin-1 inhibits hepatitis

C virus subgenomic RNA replication by activation of extracellular

regulated kinase pathwayJ

Virol7754935498200310.1128/JVI.77.9.5493-5498.200312692250

|

|

55.

|

T MurataM HijikataK ShimotohnoEnhancement

of internal ribosome entry site-mediated translation and

replication of hepatitis C virus by

PD98059Virology340105115200510.1016/j.virol.2005.06.01516005928

|

|

56.

|

J NdjomouIW ParkY LiuLD MayoJJ

HeUp-regulation of hepatitis C virus replication and production by

inhibition of MEK/ERK signalingPLoS

One4e7498200910.1371/journal.pone.000749819834602

|

|

57.

|

DI TaiSL TsaiYM ChenActivation of nuclear

factor kappaB in hepatitis C virus infection: implications for

pathogenesis and

hepatocarcinogenesisHepatology31656664200010.1002/hep.51031031610706556

|

|

58.

|

JK OemC Jackel-CramYP LiHepatitis C virus

non-structural protein-2 activates CXCL-8 transcription through

NF-kappaBArch

Virol153293301200810.1007/s00705-007-1103-118074095

|

|

59.

|

W LinWL TsaiRX ShaoHepatitis C virus

regulates transforming growth factor beta1 production through the

generation of reactive oxygen species in a nuclear factor

kappaB-dependent

mannerGastroenterology138250925182518.e1201010.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.008

|

|

60.

|

RB RayR SteeleA BasuDistinct functional

role of hepatitis C virus core protein on NF-kappaB regulation is

linked to genomic variationVirus

Res872129200210.1016/S0168-1702(02)00046-112135786

|

|

61.

|

JC LeeWC ChenSF WuAnti-hepatitis C virus

activity of Acacia confusa extract via suppressing

cyclooxygenase-2Antiviral

Res893542201110.1016/j.antiviral.2010.11.00321075144

|

|

62.

|

JC LeeCK TsengSF WuFR ChangCC ChiuYC

WuSan-Huang-Xie-Xin-Tang extract suppresses hepatitis C virus

replication and virus-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expressionJ Viral

Hepat18e315e324201110.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01424.x21692943

|