Introduction

The generation of neurons in the mammalian central

nervous system (CNS) was traditionally believed to end by early

postnatal life. However, it has been shown that the adult mammalian

brain contains self-renewable, multipotent neural stem cells (NSCs)

that are responsible for neurogenesis and plasticity in specific

regions of the adult brain (1,2).

In the hippocampus, newly generated neurons originate from stem

cells in the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (DG), and

neurogenesis continues throughout adult life (3,4).

Although the mechanisms by which neurons are generated from stem

cells are not yet well known, studies have indicated that the

number of newly generated hippocampal neurons in adults is

influenced specifically by enriched environments, learning, and

voluntary exercise (5,6).

Mastication is a behavior that is closely related

with CNS activities. Chewing causes regional increases in cerebral

blood flow and neuronal activity in the human brain (7,8).

By contrast, it has been shown that reduced mastication and

occlusal disharmony impair spatial memory and promote the

degeneration of hippocampal neurons (9,10).

We, as well as others, have also previously demonstrated that

reducing mastication by feeding mice a soft diet inhibits the

survival of newly generated neurons in the DG (11,12). However, it remains unknown whether

the induction of mastication affects the differentiation,

proliferation, or survival of newly generated cells in the adult

DG. In this study, we aimed to investigate the effects of forced

mastication by hard diet feeding on the differentiation and

survival of NSCs in the adult DG.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six-week-old C57BL/6 mice were housed in standard

cages. Room conditions were kept at a 12:12-h light/dark cycle and

an ambient temperature of 22±2°C. Animals were allowed free access

to food and water. All animal procedures were performed in

accordance with the guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals of Tokushima University Graduate School of Dentistry.

Diet

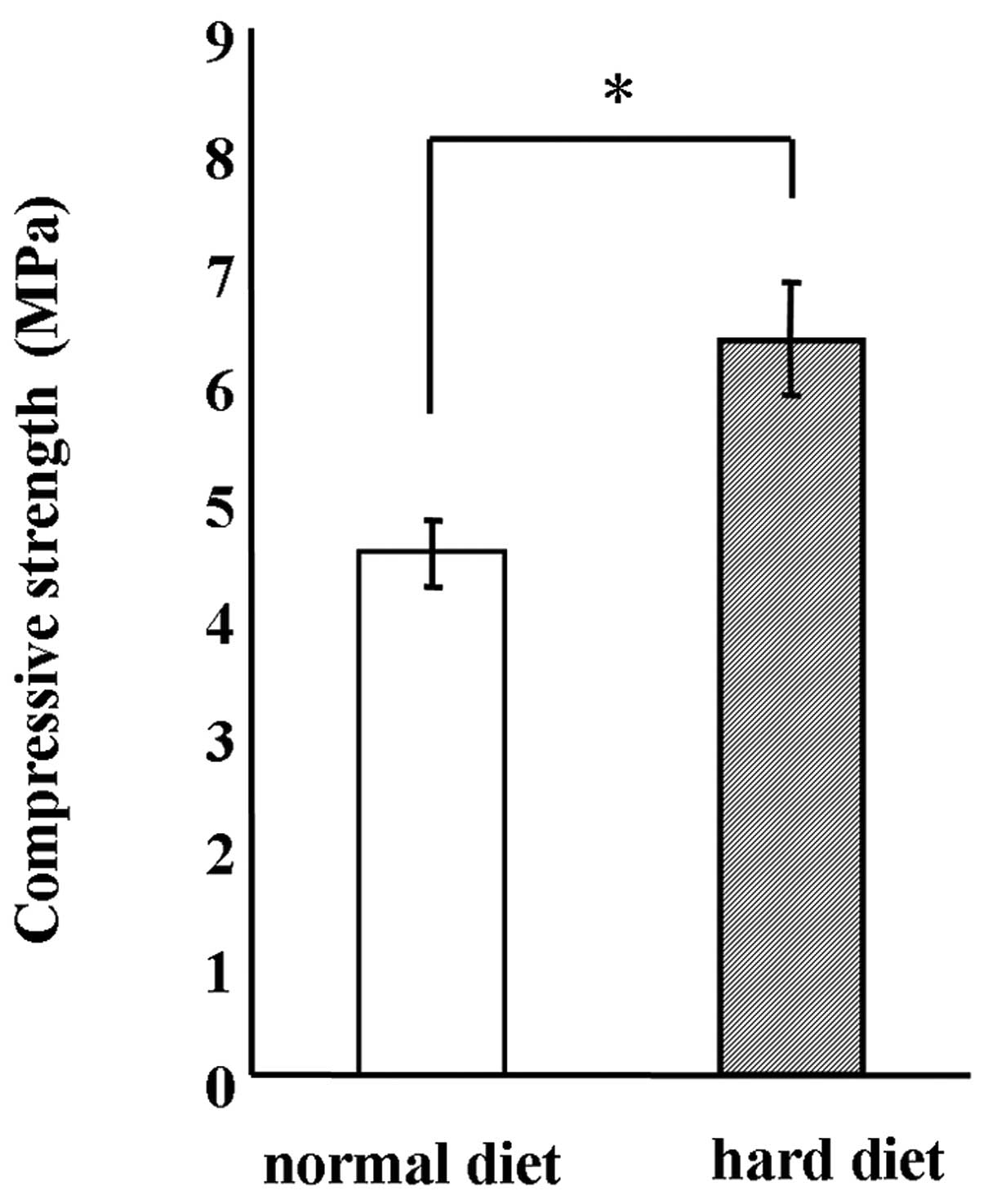

Mice were fed a standard laboratory diet, MF

(Oriental Yeast, Tokyo, Japan). To create a hard diet, MF chow was

autoclaved. The hardness of the MF chow was significantly increased

by 1.5-fold by autoclave treatment (Fig. 1). Therefore, autoclaved normal

diet chow was used as the hard diet to enforce mastication in this

study.

Experimental conditions

The time schedule of this experiment is shown in

Fig. 2. At 6 post-natal weeks,

the animals were placed in standard cages (4 or 5 animals/cage).

Control mice were allowed free access to the standard pellet

(Fig. 2A). Mice in the

experimental group were given free access to a hard diet

(autoclaved normal diet) (Fig.

2B). The animals were maintained in each experimental condition

for 8 weeks and then received bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU;

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) injections (50 mg/g body weight)

intraperitoneally once a day for 12 consecutive days. One day after

the last BrdU injection, half the mice in each group were given an

overdose of anesthetic and perfused transcardially with cold 4%

paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (11). The remaining animals in each group

were kept in their respective experimental conditions for 5

additional weeks and were perfused in a similar manner.

Body weight measurement

Throughout the experiment, the nutritional status of

the mice was monitored by weighing the mice regularly once a week

until the day of sacrifice.

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were sacrificed and perfused transcardially

with cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS as previously described

(11). The brains were removed

from the skulls and immersed in the same fixative for 5 h at 4°C

with constant rotation followed by washing with PBS overnight at

4°C. Coronal 50-μm hippocampal sections were made using a

vibratome and stored at −10°C in cryoprotectant reagent (30%

sucrose, 30% ethylene glycol and 0.25 mM polyvinylpyrrolidone in

PBS) (11). Vibratome sections

were rinsed in 1X Tris-buffered saline (TBS), blocked with 10%

normal goat serum (NGS), 1X Triton X-100 in TBS for 1 h, followed

by incubation with primary antibodies overnight. The following

primary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal antibodies against

neuronal nuclei (NeuN; 1:1,000; Millipore) and neuronal nitric

oxide synthase (nNOS; 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.),

rat-monoclonal antibodies against BrdU (1:20; Funakoshi),

rabbit-polyclonal antibodies for c-Fos (1:10,000; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.). For evaluation of the changes in neural

proliferation and survival in the DG, the BrdU in vivo

labeling protocol was used. BrdU is incorporated only in the cells

that are dividing and is integrated in the synthesized DNA enabling

them to be detected immunohistochemically. The free-floating brain

slices were initially treated with denatured solution (12 N HCl +

1X TBS) and incubated for 30 min at 37°C. After washing in TBS, the

sections were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with the

appropriate secondary antibodies: anti-mouse Alexa 594 (1:1,000)

and anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (1:1,000). Finally, nuclei were stained

with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Slices were mounted,

coverslipped in ProLong® antifade reagent (Invitrogen

Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and examined under an

epifluorescence microscope.

Volume measurement of the granular cell

layer of the DG

Brain slices stained with anti-NeuN antibody were

examined and images of the 12 sections were acquired using an

epifluorescence microscope. To calculate the DG volume, the area of

the granular cell layer was measured using ImageJ software and

multiplied by the thickness of the sections (50 μm)

according to Cavalieri’s principle (13).

Cell count

The DG was examined under a conventional

epifluorescence microscope after the slices were

immunohistochemically treated with specific antibodies. A total of

60 slices of 50-μm coronal sections were originally stored

in 5 separated tubes containing 12 slices in each tube. Sections

from every 200 μm across the whole hippocampus were selected

(12 sections from anterior to posterior). BrdU, c-Fos and nNOS

labeled cells were manually counted in each section by a blinded

observer. A ×20 objective lens was used for all counting (11). The labeled cells within the DG

were examined for both the group fed the normal diet and the group

fed the hard diet.

Morris water maze

The Morris water maze task was preformed to test

spatial learning. The task used a circular pool filled with water

containing white ink. A platform was placed in the pool so that it

was invisible at water level. The experiment was carried out after

the 5 weeks following BrdU injection. Tasks were conducted between

09:00 and 15:00 during the light cycle. After training, mice

underwent 3 trials/day for 10 consecutive days. During testing,

mice were required to locate the platform, and escape latency time

was recorded. Once mice located the platform, they were permitted

to remain on it for 10 sec. If mice did not locate the platform

within 90 sec, they were placed on the platform for 10 sec and then

removed from the pool, as previously described (14,15).

Probe test

Mice were trained in the water maze as described

above and then were subjected to a probe test. Each mouse was

subjected to a probe test immediately after the final training

trial on the 10th day. Before beginning the probe test, the

platform was removed from the pool. Mice were released from the

quadrant opposite to the previous platform quadrant, and the

swimming was tracked for 90 sec, as previously described (16,17).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from 21-week-old mice. Mice

were sacrificed by an overdose of anesthetic and the hippocampus

was dissected in RNAlater (Sigma). Total RNA of hippocampal cells

was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life

Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (1

μg) was reverse- transcribed to first-strand cDNA using a

PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A Thermal Cycler Dice

real-time system (Takara Bio, Inc.) was used for real-time PCR

(18–20). The cDNAs were amplified with

SYBR® Premix Ex Taq and specific primer pairs for

fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-1 (21), FGF-2 (22), epidermal growth factor (EGF)

(23), vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) (24,25),

insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (26), nerve growth factor (NGF),

neurotrophin-3 (NT-3), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF),

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF), neuropeptide Y,

β-tubulin III, 2′,3′-cyclic-nucleotide phosphodiesterase (CNPase),

microtubule-associated protein 2 (Map2), glial fibrillary acidic

protein (GFAP), nestin, glutamate receptor 1 (GluR1) (27), glutamate receptor 2 (GluR2)

(27), glutamate receptor 3

(GluR3) (27), glutamate receptor

4 (GluR4) (27), N-methyl

D-aspartate receptor subtype 2B (NR2B) (28) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Primers for NGF, NT-3, GDNF, β-tubulin III,

CNPase, Map2, GFAP, nestin and GAPDH were designed with Perfect

Real-Time Primer Design software (Takara Bio, Inc.). The primers

used in this study are listed in Table I. The PCR conditions were as

follows: 10 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec

and 60°C for 30 sec, and finally, 15 sec at 95°C and 30 sec at

60°C.

| Table I.Primer list for real-time PCR

(5′→3′). |

Table I.

Primer list for real-time PCR

(5′→3′).

| Genes | Primer

sequences |

|---|

| GAPDH | F:

AACTTTGGCATTGTGGAAGG |

| R:

ACACATTGGGGGTAGGAACA |

| FGF-1 | F:

AGAGTACCGAGACTGGCCAGTAC |

| R:

TCTGGCCATAGTGAGTCCGAG |

| FGF-2 | F:

CCAACCGGTACCTTGCTATG |

| R:

TATGGCCTTCTGTCCAGGTC |

| EGF | F:

ACGGTTTGCCTCTTTTCCTT |

| R:

GTTCCAAGCGTTCCTGAGAG |

| VEGF | F:

GGAGATCCTTCGAGGAGCACTT |

| R:

GGCGATTTAGCAGCAGATATAAGAA |

| IGF-1 | F:

GTGTGGACCGAGGGGCTTTTACTTC |

| R:

GCTTCAGTGGGGCACAGTACATCTC |

| NGF | F:

CAGACCCGCAACATCACTGTA |

| R:

CCATGGGCCTGGAAGTCTAG |

| NT-3 | F:

CATTCGGGGACACCAGGTC |

| R:

TTTGCACTGAGAGTTCCAGTGTTT |

| BDNF | F:

GGTATCCAAAGGCCAACTGA |

| R:

CTTATGAATCGCCAGCCAAT |

| GDNF | F:

ACCCGCTTCCATAAGGCTTTA |

| R:

CAGCCTTGTGCCGAAAGAC |

| Neuropeptide Y | F:

GCAGAGGACATGGCCAGATAC |

| R:

TGGATCTCTTGCCATATCTCTGTCT |

| β-tubulin III | F:

GGGCATTCCAACCTT |

| R:

AGCTCGGCGCCCTCTGTGTAGT |

| CNPase | F:

CCTTAGCAACAGCCGAGTGGATA |

| R:

GTTCCCAGATCACAAGCCAACA |

| Map2 | F:

AATAGACCTAAGCCATGTGACATCC |

| R:

AGAACCAACTTTAGCTTGGGCC |

| GFAP | F:

GTACCAGGACCTGCTCAATG |

| R:

TGTGCTCCTGCTTGGACTCCTT |

| Nestin | F:

CTCCAAGAATGGAGGCTGTAGGAA |

| R:

CCTATGAGATGGAGCAGGCAAGA |

| GluR1 | F:

ATGCTGGTTGCCTTAATCGAG |

| R:

ATTGATGGATTGCTGTGGGAT |

| GluR2 | F:

TTGAGTTCTGTTACAAGTCAAGGGC |

| R:

AGGAAGATGGGTTAATATTCTGTGGA |

| GluR3 | F:

AACGCCTGTAAACCTTGCAGT |

| R:

AGTCCTTGGCTCCACATTCC |

| GluR4 | F:

CCAGGGCAGAGGCGAAG |

| R:

CGTTTTCTCCCACACTCCCA |

| NR2B | F:

TCCGCCGTGAGTCTTCTGTCTATG |

| R:

CTGGGTGGTAAAGGGTGGGTTGTC |

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as the means ± SEM. For

statistical analysis of the results, the Student’s t-test and ANOVA

(Scheffe’s post hoc test) were used to compare the group fed the

normal diet with the group fed the hard diet.

Results

Effect of different food textures on

mouse growth and dietary intake

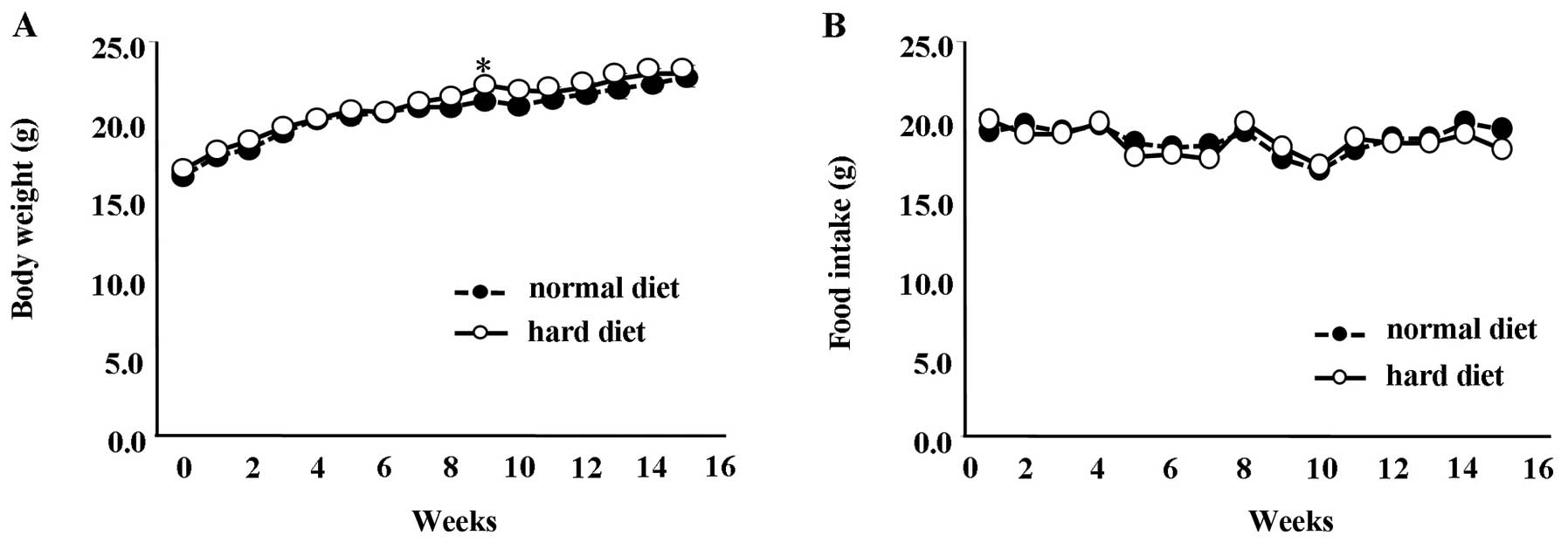

Mice fed a normal diet between the ages of 6 and 20

weeks showed a significant difference in body weight compared to

the mice fed a hard diet at 11 weeks (Fig. 3A) (P<0.01). However, at all

other time-points, the difference in body weight between the groups

was not statistically significant. Similarly, the amount of food

intake between the group fed the normal diet and the group fed the

hard diet showed no significant differences (Fig. 3B).

Proliferation of newly generated cells in

the DG

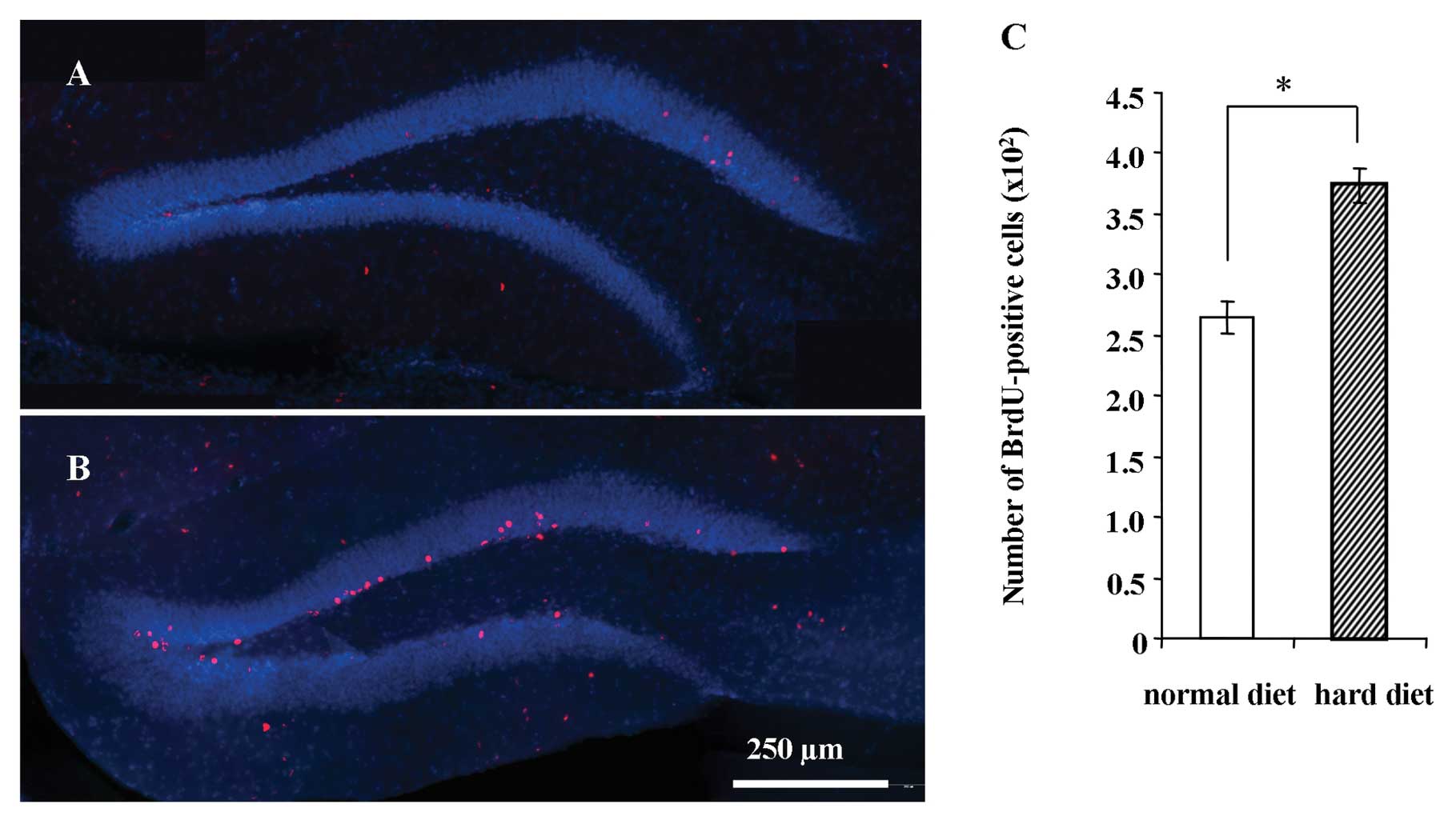

Representative images of BrdU-positive cells in the

hippocampus 1 day after the BrdU injection are shown in Fig. 4 for the group fed the normal diet

(Fig. 4A) and group fed the hard

diet (Fig. 4B). The number of

BrdU-positive cells in the DG 1 day after the BrdU injection was

not significantly different between the groups (Fig. 4C).

Survival of newly generated cells in the

DG

Representative images of BrdU-positive cells in the

hippocampus 5 weeks after BrdU injections are shown for the group

fed the normal diet (Fig. 5A) and

the group fed the hard diet (Fig.

5B). There was a significantly larger number of BrdU-positive

cells in the group fed the hard diet compared to the group fed the

normal diet 5 weeks after BrdU injection (P<0.001) (Fig. 5C).

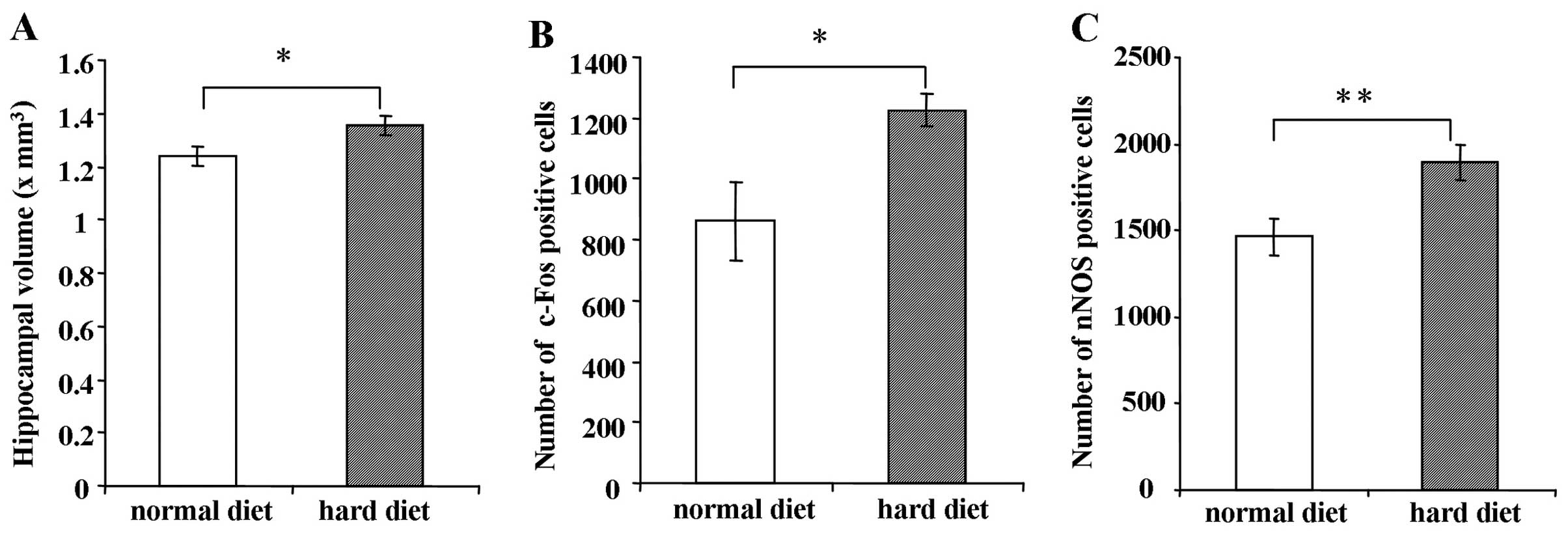

Hippocampal volume in mice fed the hard

or normal diet

As shown in Fig.

6A, the hippocampal volume of the mice fed the hard diet was

significantly larger than the hippocampal volume of the mice fed

the normal diet when measured 5 weeks after BrdU injection

(P<0.05).

Immunostaining of c-Fos and nNOS in the

DG

The number of c-Fos-positive cells in the group fed

the hard diet was greater than that in the group fed the normal

diet 5 weeks after BrdU injection (Fig. 6B) (P<0.05). Similarly, the

number of nNOS-positive cells in the DG was significantly increased

in the group fed the hard diet compared to the group fed the normal

diet 5 weeks after BrdU injection (Fig. 6C) (P<0.01).

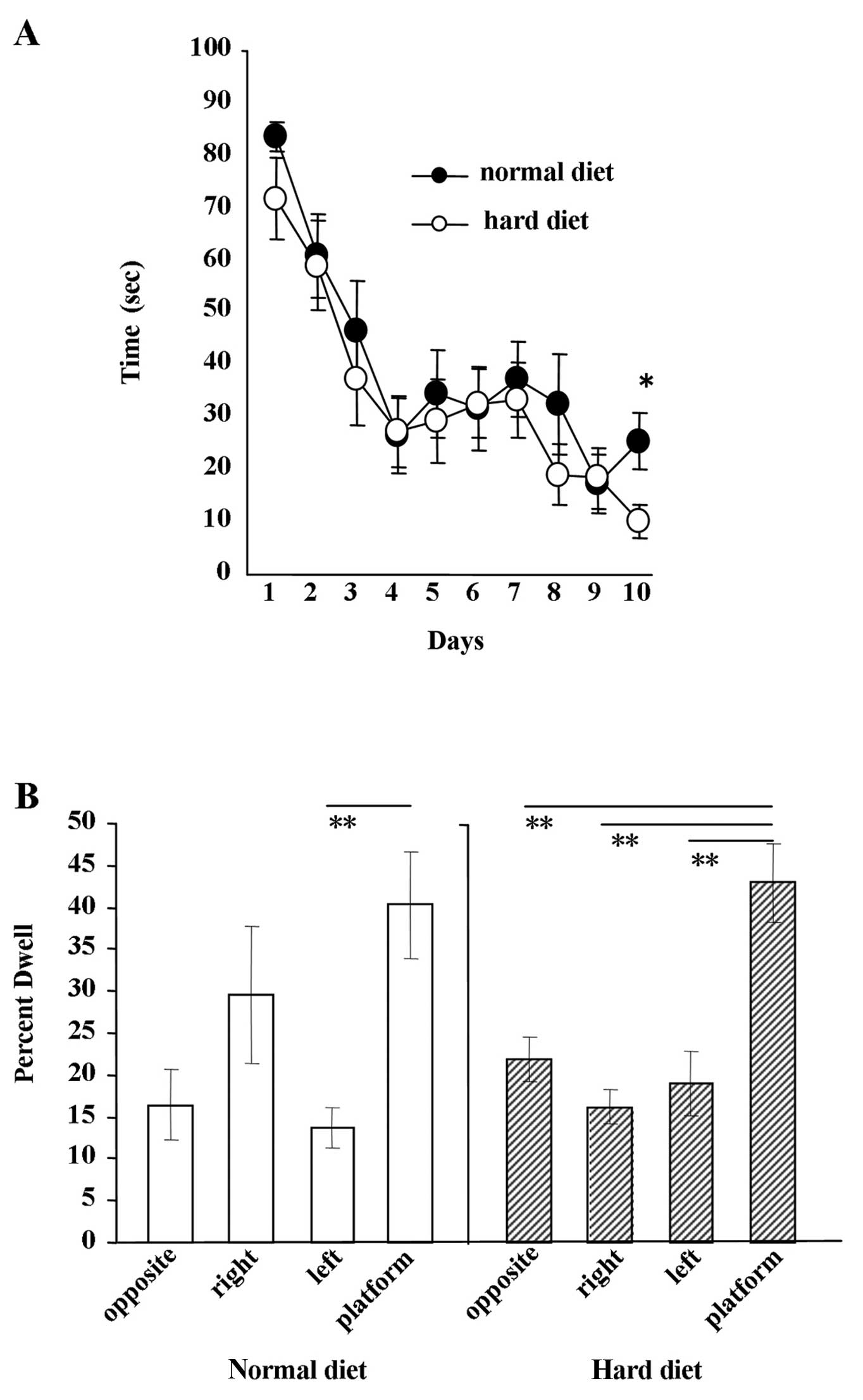

Water maze experiment

The results of the Morris water maze experiment are

shown in Fig. 7. The escape

latency in each group decreased as the number of trials progressed.

No significant difference in the escape latency was found between

the group fed the hard diet and the group fed the normal diet from

day 1 to 9 (Fig. 7A). Ten days

after the beginning of the experiment, we observed a significant

difference between the groups (Fig.

7A) (P<0.005). The results of the water maze probe test are

shown in Fig. 7B. After 10 days

of water maze experiments, the probe test was performed. When mice

fed the hard diet were allowed to search for the platform, the

period during which the mice focally searched around the former

platform location was significantly longer than searches in other

locations (P<0.01). By contrast, when mice fed the normal diet

were subjected to the probe test, the only difference observed in

their searches was between the time spent around the former

platform location and the left side of the arena (P<0.05).

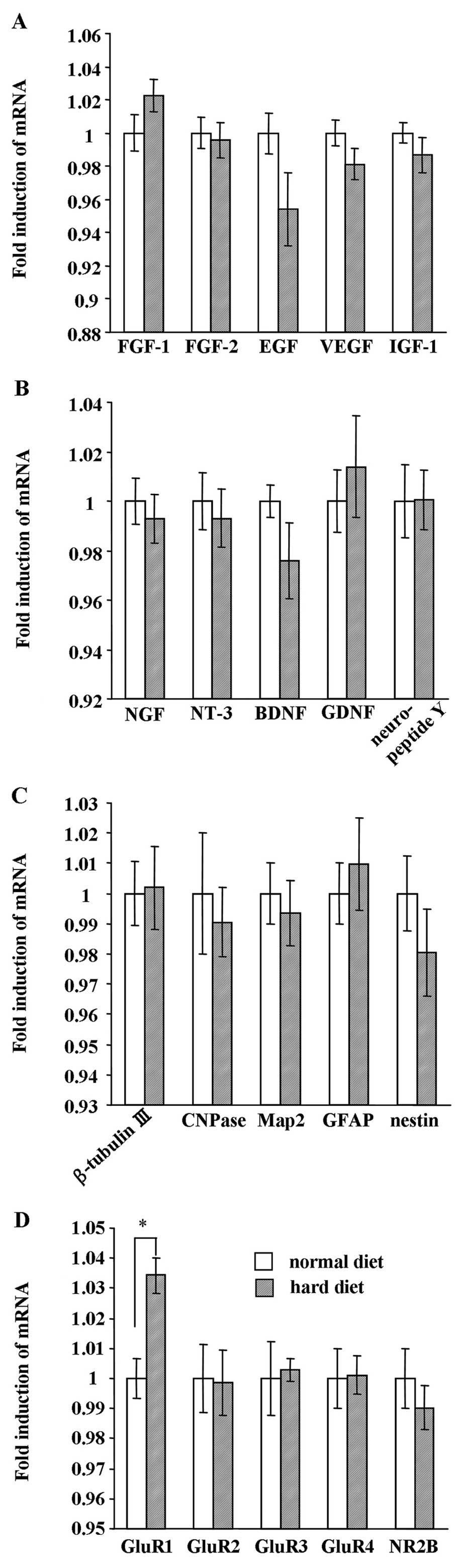

Effect of hard diet feeding on mRNA

expression of growth factors, neurotrophic factors, NSC markers and

receptors in the hippocampus

As is shown in Fig.

8, we analyzed the mRNA expression of growth factors,

neurotrophic factors, NSC markers and receptors in the hippocampus

between the group fed the hard diet and the group fed the normal

diet at the end of the experiment. Real-time PCR analysis revealed

that the mRNA expression of the growth factors, FGF-1, FGF-2, EGF,

VEGF and IGF-1, was not affected by food texture (Fig. 8A). In addition, the expression of

neurotrophic factors (NGF, NT-3, BDNF, GDNF and neuropeptide Y)

(Fig. 8B) and NSC markers

(β-tubulin III, CNPase, Map2, GFAP and nestin) (Fig. 8C) did not differ between the group

fed the hard diet and the group fed the normal diet. While the

expression of the receptors, GluR2, GluR3, GluR4 and NR2B (Fig. 8D), was not affected by food

texture, GluR1 mRNA expression was significantly increased in the

group fed the hard diet (P<0.01).

Discussion

To date, information as to how enforced mastication

regulates NSC proliferation and survival in the hippocampus is

lacking. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to

demonstrate that the NSC survival in the hippocampus is increased

and spatial memory is improved by forced mastication.

In this study, the normal diet was autoclaved to

increase its hardness and thus force the mice to chew. With respect

to body weight and food intake (Fig.

3), the growth of the mice was not affected by the autoclaved

diet. Therefore, we inferred that the major nutritional components

were not markedly different between the normal and the autoclaved

normal diet.

We assessed the proliferation of subgranular

progenitor cells in the DG of adult mice immediately after

consecutive injections of BrdU. We observed that neither the hard

diet nor the normal diet caused a change in the number of

BrdU-positive cells (Fig. 4).

These results indicated that the enforced mastication had no effect

on the proliferation of progenitor cells as evaluated by BrdU

labeling. Five weeks after the BrdU injections, a decrease in the

number of BrdU-positive cells was observed not only in the group

fed the normal diet but also in the group fed the hard diet

(Fig. 5). However, we found that

the number of surviving BrdU-positive cells was significantly

increased in the group fed the hard diet compared to the group fed

the normal diet (Fig. 5C).

Therefore, these data suggest that forced mastication in the group

fed the hard diet increased the survival rate of the newly

generated cells in the DG.

Hippocampal volume in mice fed the hard diet was

significantly increased compared to the mice fed the normal diet

(Fig. 6A). Since a number of

studies have shown that hippocampal volume affects memory functions

(29), forced mastication due to

a hard diet may be able to indirectly improve memory. For an

assessment of neural activity after forced mastication, the

expression of c-Fos in the DG of the group fed the hard diet and

the group fed the normal diet was evaluated. It has been shown that

the immunostaining of c-Fos is expressed in an activity-dependent

manner and has been used as a marker for activated neurons in the

DG (30,31). In this study, since c-Fos levels

in the DG of the mice fed the hard diet significantly increased

compared with the mice fed the normal diet (Fig. 6B), mastication does indeed appear

to influence neural activity in the DG.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an intercellular signaling

molecule that is involved in several physiological processes

(32,33). At least 3 isoforms of NO synthase

(NOS) have been identified in the CNS, including endothelial

(eNOS), neuronal (nNOS) and inducible (iNOS) forms (32,33). It has been reported that

nNOS-knockout increases the survival rate of neuronal cells in the

hippocampus (34). However, our

results showed that the number of nNOS-positive cells in the mice

fed the hard diet was significantly increased (Fig. 6C), and that the number of

BrdU-positive cells in the DG of the group fed the hard diet was

greater than that in the group fed the normal diet (Fig. 5C). Therefore, the survival of

newborn cells during adult neurogenesis in the DG may depend upon

other mechanisms in addition to nNOS signaling. For example,

sensory-motor information taken from the oral cavity may reach the

hippocampus, consequently affecting the neurogenesis rate. Another

possibility is that the muscular contractions involved in

mastication may increase cerebral blood flow, allowing an increase

in the entry of growth factors into the DG that could affect the

rate of neurogenesis.

The Morris water maze test was used to examine the

effect of induced mastication on spatial learning ability, as

previously described (35).

Although the group fed the hard diet showed a significant decrease

in escape latency only at 10 days compared with the group fed the

normal diet (Fig. 7A)

(P<0.005), the latency on the probe test after 10 days differed

between the group fed the hard diet and the group fed the normal

diet (Fig. 7B). This finding

indicated that the group fed the hard diet spent significantly more

time in the former location of the platform compared to all other

locations. For this reason, we suggest that forced mastication can

improve spatial learning ability.

We also assessed the effect of a hard diet on the

mRNA expression of various growth factors, neurotrophic factors,

neuronal stem cell markers, and receptors in the hippocampus by

real-time PCR. Although several factors were examined, we observed

a small but significant increase in the expression of GluR1 mRNA in

the group fed the hard diet compared with the group fed the normal

diet (P<0.01). GluRs are synaptic receptors located primarily on

the membranes of neuronal cells (36). One of the major functions of GluRs

appears to be the modulation of synaptic plasticity, memory and

learning (36). Therefore, these

changes in the group fed the hard diet may be attributed to the

slight increase in GluR1 mRNA expression in the hippocampus

(Fig. 8D), as well as in

hippocampal volume (Fig. 6A)

compared with the group fed the normal diet. However, since these

results may be sensitive to the timing of experimentation, further

experiments may be required to detect the critical periods of mRNA

expression in the hippocampus.

In conclusion, forced mastication alters the

survival rate and NSC activity in the DG. In addition, spatial

memory was improved in the group fed the hard diet compared to the

group fed the normal diet. These results suggest that mastication

caused by daily food texture may improve or accelerate the recovery

of spatial memory functions in the hippocampus, preventing senile

dementia.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by

the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 21390548 to M.M. and

no. 22592296 to T.H.) from the Ministry of Education, Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (2010–2014).

References

|

1.

|

Gage FH: Mammalian neural stem cells.

Science. 287:1433–1438. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Taupin P and Gage FH: Adult neurogenesis

and neural stem cells of the central nervous system in mammals. J

Neurosci Res. 69:745–749. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Altman J and Das GD: Autoradiographic and

histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in

rats. J Comp Neurol. 124:319–335. 1965. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H and Gage FH:

Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related

decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci.

16:2027–2033. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

van Praag H, Kempermann G and Gage FH:

Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult

mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 2:266–270. 1999.

|

|

6.

|

Gould E, Beylin A, Tanapat P, Reeves A and

Shors TJ: Learning enhances adult neurogenesis in the hippocampal

formation. Nat Neurosci. 2:260–265. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Momose T, Nishikawa J, Watanabe T, Sasaki

Y, Senda M, Kubota K, Sato Y, Funakoshi M and Minakuchi S: Effect

of mastication on regional cerebral blood flow in humans examined

by positron-emission tomography with 15O-labelled water

and magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Oral Biol. 42:57–61. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Onozuka M, Fujita M, Watanabe K, Hirano Y,

Niwa M, Nishiyama K and Saito S: Mapping brain region activity

during chewing: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J

Dent Res. 81:743–746. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Kato T, Usami T, Noda Y, Hasegawa M, Ueda

M and Nabeshima T: The effect of the loss of molar teeth on spatial

memory and acetylcholine release from the parietal cortex in aged

rats. Behav Brain Res. 83:239–242. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Terasawa H, Hirai T, Ninomiya T, Ikeda Y,

Ishijima T, Yajima T, Hamaue N, Nagase Y, Kang Y and Minami M:

Influence of tooth-loss and concomitant masticatory alterations on

cholinergic neurons in rats: immunohistochemical and biochemical

studies. Neurosci Res. 43:373–379. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Mitome M, Hasegawa T and Shirakawa T:

Mastication influences the survival of newly generated cells in

mouse dentate gyrus. Neuroreport. 16:249–252. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Tsutsui K, Kaku M, Motokawa M, Tohma Y,

Kawata T, Fujita T, Kohno S, Ohtani J, Tenjoh K, Nakano M, Kamada H

and Tanne K: Influences of reduced masticatory sensory input from

soft-diet feeding upon spatial memory/learning ability in mice.

Biomed Res. 28:1–7. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Gundersen HJ, Bagger P, Bendtsen TF, et

al: The new stereological tools: disector fractionator, nucleator

and point sampled intercepts and their use in pathological research

and diagnosis. APMIS. 96:857–881. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Fujioka A, Fujioka T, Tsuruta R, Izumi T,

Kasaoka S and Maekawa T: Effects of a constant light environment on

hippocampal neurogenesis and memory in mice. Neurosci Lett.

488:41–44. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Tauber SC, Bunkowski S, Ebert S, Schulz D,

Kellert B, Nau R and Gerber J: Enriched environment fails to

increase meningitis-induced neurogenesis and spatial memory in a

mouse model of pneumococcal meningitis. J Neurosci Res.

87:1877–1883. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Moser E, Moser MB and Andersen P: Spatial

learning impairment parallels the magnitude of dorsal hippocampal

lesions, but is hardly present following ventral lesions. J

Neurosci. 13:3916–3925. 1993.

|

|

17.

|

Stackman RW Jr, Lora JC and Williams SB:

Directional responding of C57BL/6J mice in the Morris water maze is

influenced by visual and vestibular cues and is dependent on the

anterior thalamic nuclei. J Neurosci. 32:10211–10225. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Hasegawa T, Chosa N, Asakawa T, Yoshimura

Y, Ishisaki A and Tanaka M: Establishment of immortalized human

periodontal ligament cells derived from deciduous teeth. Int J Mol

Med. 26:701–705. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Asakawa T, Chosa N, Yoshimura Y, Asakawa

A, Tanaka M, Ishisaki A, Mitome M and Hasegawa T: Fibroblast growth

factor 2 inhibits the expression of stromal cell-derived factor 1α

in periodontal ligament cells derived from human permanent teeth

in vitro. Int J Mol Med. 29:569–573. 2012.

|

|

20.

|

Hasegawa T, Chosa N, Asakawa T, Yoshimura

Y, Fujihara Y, Kitamura T, Tanaka M, Ishisaki A and Mitome M:

Differential effects of TGF-β1 and FGF-2 on SDF-1α expression in

human periodontal ligament cells derived from deciduous tooth in

vitro. Int J Mol Med. 30:35–40. 2012.

|

|

21.

|

Arnold RS, Sun CQ, Richards JC, Grigoriev

G, Coleman IM, Nelson PS, Hsieh CL, Lee JK, Xu Z, Rogatko A,

Osunkoya AO, Zayzafoon M, Chung L and Petros JA: Mitochondrial DNA

mutation stimulates prostate cancer growth in bone stromal

environment. Prostate. 69:1–11. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Huang CC, Yeh CM, Wu MY, Chang AY, Chan

JY, Chan SH and Hsu KS: Cocaine withdrawal impairs metabotropic

glutamate receptor-dependent long-term depression in the nucleus

accumbens. J Neurosci. 31:4194–4203. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Qu R, Li Y, Gao Q, Shen L, Zhang J, Liu Z,

Chen X and Chopp M: Neurotrophic and growth factor gene expression

profiling of mouse bone marrow stromal cells induced by ischemic

brain extracts. Neuropathology. 27:355–363. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Fabel K, Fabel K, Tam B, Kaufer D, Baiker

A, Simmons N, Kuo CJ and Palmer TD: VEGF is necessary for

exercise-induced adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci.

18:2803–2812. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Cao L, Jiao X, Zuzga DS, Liu Y, Fong DM,

Young D and During MJ: VEGF links hippocampal activity with

neurogenesis, learning and memory. Nat Genet. 36:827–835. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Iida K, Del Rincon JP, Kim DS, Itoh E,

Nass R, Coschigano KT, Kopchick JJ and Thorner MO: Tissue-specific

regulation of growth hormone (GH) receptor and insulin-like growth

factor-I gene expression in the pituitary and liver of GH-deficient

(lit/lit) mice and transgenic mice that overexpress bovine GH (bGH)

or a bGH antagonist. Endocrinology. 145:1564–1570. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Destot-Wong KD, Liang K, Gupta SK, Favrais

G, Schwendimann L, Pansiot J, Baud O, Spedding M, Lelièvre V, Mani

S and Gressens P: The AMPA receptor positive allosteric modulator,

S18986, is neuroprotective against neonatal excitotoxic and

inflammatory brain damage through BDNF synthesis.

Neuropharmacology. 57:277–286. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28.

|

Boon WC, Diepstraten J, van der Burg J,

Jones ME, Simpson ER and van den Buuse M: Hippocampal NMDA receptor

subunit expression and water maze learning in estrogen deficient

female mice. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 140:127–132. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Ystad MA, Lundervold AJ, Wehling E,

Espeseth T, Rootwelt H, Westlye LT, Andersson M, Adolfsdottir S,

Geitung JT, Fjell AM, Reinvang I and Lundervold A: Hippocampal

volumes are important predictors for memory function in elderly

women. BMC Med Imaging. 9:172009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Kee N, Teixeira CM, Wang AH and Frankland

PW: Preferential incorporation of adult-generated granule cells

into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci.

10:355–362. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Ahn SN, Guu JJ, Tobin AJ, Edgerton VR and

Tillakaratne NJ: Use of c-fos to identify activity-dependent spinal

neurons after stepping in intact adult rats. Spinal Cord.

44:547–559. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Bredt DS, Hwang PM and Snyder SH:

Localization of nitric oxide synthase indicating a neural role for

nitric oxide. Nature. 347:768–770. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Brenman JE and Bredt DS: Synaptic

signaling by nitric oxide. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 7:374–378. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34.

|

Fritzen S, Schmitt A, Köth K, Sommer C,

Lesch KP and Reif A: Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS-I)

knockout increases the survival rate of neural cells in the

hippocampus independently of BDNF. Mol Cell Neurosci. 35:261–271.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35.

|

Sharma S, Rakoczy S and Brown-Borg H:

Assessment of spatial memory in mice. Life Sci. 87:521–536. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36.

|

Peng S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wang H and Ren

B: Glutamate receptors and signal transduction in learning and

memory. Mol Biol Rep. 38:453–460. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|