Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA), a highly prevalent, slowly

progressive, degenerative disease of diarthrodial joints, is

characterized by a progressive degradation of articular cartilage

associated with marginal osteophyte formation, progressive

symptomatic loss of mechanical function and remodeling of the

subchondral bone, belonging to the GU BI of Traditional Chinese

Medicine (TCM) (1,2). As the precise molecular mechanism of

OA has yet to be fully elucidated, a wide variety of animal models

have been developed to study osteoarthritic progression,

characterize the features of the early pathological changes of OA

and to evaluate new drugs and/or original therapies (3). The papain-induced OA model has been

widely studied in various animal species such as rats, thus

providing new insights into pathogenic mechanisms and impact of

hyaline cartilage (4,5). In this model, there is a sequence of

events in which the degradation of the superficial zone develops

into fibrillations of the cartilage and eventually leads to

ulcerations, erosions and tidemark replication.

Tidemark, at which non-mineralized cartilage comes

to contain hydroxyapatite, is a chondro-osseous junction between

cartilage and bone in diarthrodial joints (6). The vicinity of the tidemark enhanced

metabolic activity, consistent with mineralization, including the

expression of alkaline phosphatase, the deposition of type X

collagen and the ability to bind tetracycline in vivo. The

tidemark replication is considered a characteristic of the

osteoarthrotic process with the advance of a calcification front

advancing into the non-calcified cartilage of zone IV (7). The changes of tidemark are

considered to be coordinated with the resorption of the calcified

cartilage of zone V, as the subchondral bone thickens and replaces

it (8).

The loss of chondrocyte function was found to be a

persistent and important event in OA. A variety of stimuli, such as

mechanical injury, loss of growth factors or excessive reactive

oxygen species, can induce chondrocyte depletion (9). Since chondrocyte is solely

responsible for the maintenance and production of extracellular

matrix (ECM), chondrocyte depletion is indicated in the cartilage

degradation, which pertains to OA pathogenesis (10,11). Chondrocyte apoptosis was thought

to be a major cause of chondrocyte depletion during OA progression,

so enhanced chondrocyte apoptosis is considered to be a sign of

progressive cartilage degradation. However, the extent of the

contribution of apoptotic cell death to chondrocyte depletion in OA

progression remains to be resolved. Previous studies reported that

another type of cell death, autophagy, may be involved in

chondrocyte death during OA progression (12,13).

Tougu Xiaotong capsule (TXC), a TCM formulation,

consists of a combination of four natural products including

Radix Morindae Officinalis, Radix Paeoniae Alba,

Rhizoma Chuanxiong and Glabrous Sarcandra Herb. These natural

products together confer TXC properties of nourishing Shen,

supplementing Jing, filling in Sui, stretching tenders and dredging

collaterals to strengthen tendons and bones at the theories of TCM.

TXC has been used for the osteoarthritic treatment in the Second

People's Hospital Affiliated to Fujian University of TCM for two

decades, and it has been shown to have significant therapeutic

effects on OA in the clinical trials, such as evident improvements

in osteoarthritic symptoms, pain, swelling and motion of joint.

Previously, we reported that TXC could inhibit chondrocyte

apoptosis by upregulation of Bcl-2, downregulation of p53,

caspase-9 and caspase-3 (14).

However, the molecular mechanism of the therapeutic effect of TXC

remains largely unknown. Therefore, using a papain-induced OA in

rat knee joints, we evaluated the effect of TXC on the tidemark

replication and cartilage degradation, and investigated the

underlying mechanisms of TXC in the regulation of chondrocyte

autophagy.

Materials and methods

Animals

Forty 4-week-old male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats of

Specific Pathogen Free (SPF), qualified number SCXK (Shanghai)

2007-0005, were purchased from the Shanghai Slack Laboratory Animal

Co. (Shanghai, China). The Fujian University of TCM Experimental

Animal Centre offers SPF medical laboratory animal environmental

facilities, qualified number SYXK(Min) 2009-0001. The care and use

of the laboratory animals complied with the Guidance Suggestions

for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 2006 of the Ministry of

Science and Technology, China.

Experimental design

After one week of acclimation, the rats received a

12 μl intra-articular injection of a 1 U/ml of L-cysteine-activated

papain in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO,

USA) in their double knee joints at 1, 4 and 7 days (4). Eight weeks after papain-induced OA,

the animals were randomly divided into four groups. The TXC+OA

group received oral TXC (the Second People's Hospital Affiliated to

Fujian University of TCM, medical license no. MINZHIZI Z20100006;

184 mg/kg/day). The glucosamine (GlcN)+OA group received oral GlcN

sulfate (Sigma; 150 mg/kg/day). The OA group and control group (non

papain-induced OA) received equivalent saline only. All groups were

treated once a day for 12 consecutive weeks, following which the

animals were sacrificed. The changes of cartilage structure and

tidemark were observed by digital radiography (DR), optical

microscopy, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission

electron microscopy (TEM).

Gross morphology of the knee joints

The gross morphological changes in cartilage were

examined by DR (LDRD-01BL, Beijing Aerospace Zhongxing Medical

System Co., Ltd., China), and the grade of knee joint degradation

of DR films was according to the Kellgren-Lawrence X-ray grade

standard (15).

The tibial plateau cartilage was bivalved in the

coronal plane with a sharp osteotome. The exposed surface was

rinsed with PBS repeatedly to remove blood and bone marrow.

Specimens, 5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm in size for SEM, were then fixed with

2% glutaraldehyde solution, washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate

buffer, and post-fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydrating

with an alcohol gradient series, and dehydrating with isoamyl

acetate again, the specimen was dried using a critical point dryer

with HCP-2. After coating with a layer of gold, all specimens were

observed under SEM (JSM-6380LV, JEOL, Japan).

Histopathological examination of the knee

joints

The joints were sectioned 0.5 cm above and below the

joint line, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 3 days, and

then decalcified for 2 weeks in buffered 12.5%

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and formalin solution. The

cartilage was stained with Safranin O-fast green stains to assess

the general morphology and matrix proteoglycans. Cartilage

histological changes were evaluated according to the Mankin score

(16).

Ultrastructural examination of the knee

articular cartilage

The tibial plateau cartilage, 2 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm in

size for TEM, was fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde and 1.5%

paraformaldehyde solution (pH 7.3) at 4°C for 24 h, postfixed with

1% osmic acid and 1.5% potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) solution (pH

7.3) at 4°C for 2 h. The samples were then washed, dehydrated with

graded alcohol, and embedded in Epon-Araldite resin. Ultrathin

sections were cut on a Leica ultramicrotome and stained with 2%

aqueous uranyl acetate, counter stained with 0.3% lead citrate and

examined with TEM (H7650, JEOL).

The subchondral bone was dried at 180°C for 24 h to

grind and pass the powder through 200-mesh steel sieve, and

examined with High Resolution TEM (JEM-2010, JEOL).

Western blot analysis

Protein (20 μg) of each sample was heated to 100°C

for 5 min and then resolved on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. The proteins

were transferred to methanol-wetted polyvinylidene difluoride

(PVDF) membranes in Tris/Glycine transfer buffer. Subsequently, the

membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in blocking

buffer (5% skim milk powder, 0.5% Tween-20 in tris-buffered saline;

TBS). Blots were incubated with LC3 I/II, ULK1, Beclin1 and β-actin

(Abcam, Cambridge, UK) followed by an HRP-conjugated secondary

antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized by Western Blot

Chemiluminescence Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). Immunoblot bands were quantitated with the Tocan

190 protein assay system (Bio-Rad, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are represented as the means of averages ±

standard deviation (SD) and analyzed by using the SPSS package for

Windows (version 13.0). Statistical analysis of the data was

performed with Student's t-test and ANOVA. The enumeration data was

analyzed by the Chi-square test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

No signs of drug toxicity were noted in the SD rats

treated with TXC or GlcN. The level of daily activity was similar

in all four experimental groups, and there were no significant

differences in body weight between the groups during the study

period.

TXC delays the degradation of

papain-induced OA

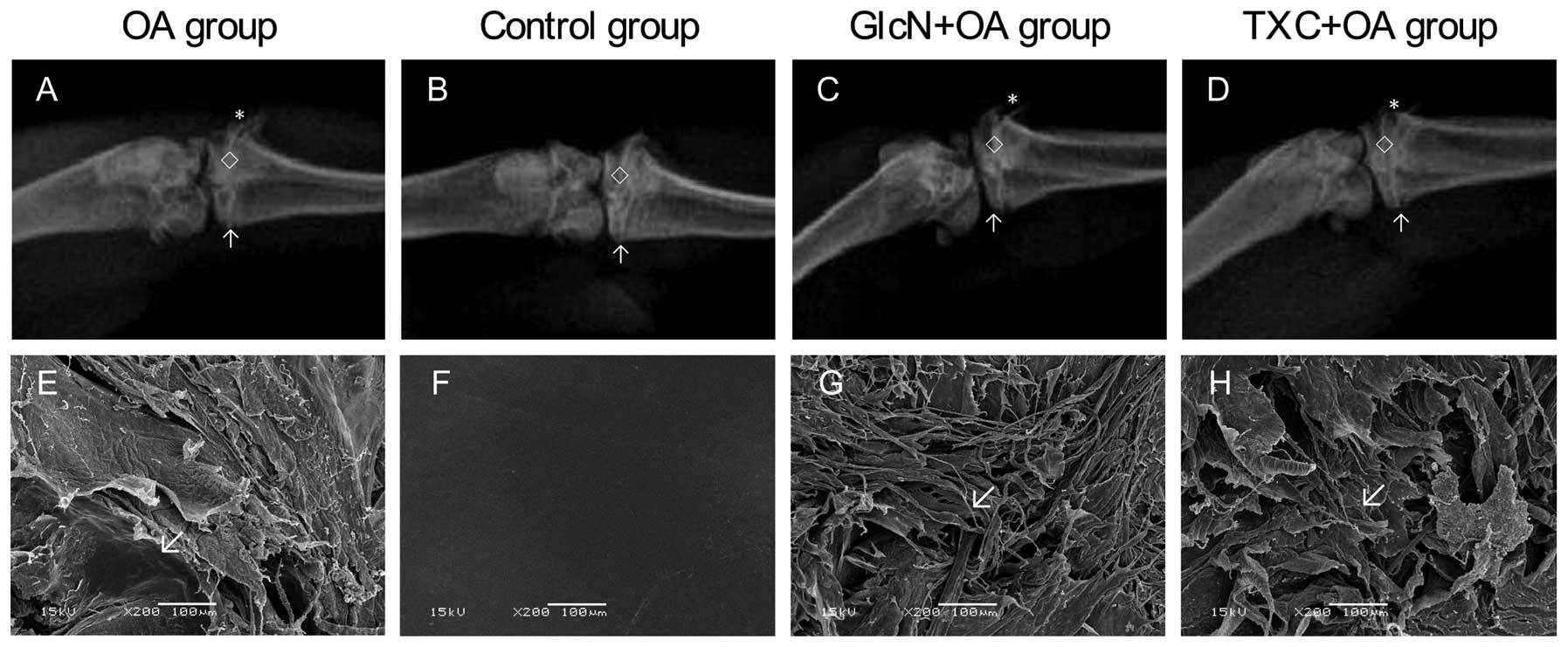

In the knee joints, gross morphologic changes with a

significant difference between the control group and the treatment

with TXC or GlcN and OA groups are shown in Fig. 1. The width of the hind limb knee

joint of the TXC or GlcN group was clearer and wider than that of

the OA group. In the OA group, gross morphologic changes were

characterized by cartilage degradation, such as fibrillation,

erosion and ulcer formation, and osteophyte formation, observed in

the femoral condyle and tibial plateau. Markedly less severity of

knee joint degradation was observed following treatment with TXC or

GlcN (Table I; P<0.05).

| Table IKellgren-Lawrence X-ray grade standard

in the different groups. |

Table I

Kellgren-Lawrence X-ray grade standard

in the different groups.

| Group | G0 | G1 | G2 | G3 | G4 |

|---|

| OA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Controlb | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

GlcN+OAa,c | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| TXC+OAa,c | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

TXC inhibits cartilage tidemark

replication

Tibial plateau cartilage from the OA group showed

evident histological changes, such as moderate-to-severe

hypocellularity, complete disorganization, proteoglycan reduction

on Safranin O-fast green staining of ECM, denudation of articular

surface and fissures extending into the deep zones, and tidemark

replication, compared to the control group (Fig. 2A–F). Osteophytes were present at

the medial margins of the tibial plateau. In turn, tibial plateau

cartilage from the control group showed homogeneous and intense

staining of proteoglycans at ECM, normal cellularity and structure

across the different layers, and tidemark wave-shaped (Fig. 2G and H). As shown in Fig. 2I–L, tibial plateau cartilage

following the treatment with TXC or GlcN displayed improvement in

cellularity and cellular organization in chondron-like manner,

although there was some diffuse hypercellurarity compared to the OA

group. There was also reduction of structure irregularities and

mild improvement of ECM. The Mankin scores of cartilage in both the

TXC or GlcN and OA groups were significantly higher than those in

the control group (P<0.01), and in the TXC or GlcN groups they

were significantly lower than those in the OA group (P<0.01)

(Fig. 2M).

| Figure 2Histology analyses of the medial

tibial plateau treated with TXC. Histological sections of the

tibial plateau stained with Safranin O-fast green to illustrate

pathological changes. The OA tibial plateau showed loss of viable

chondrocytes (A, arrow), chondrocyte proliferation (B, asterisk),

loss of proteoglycans, and tidemark replication (C and D, arrow).

The cartilage showed fibrillation, vertical fissures (E, diamond)

and delamination (F). The subchondral trabecular bone architecture

was altered with sclerosed bone (C and D, asterisk) and the

cellular bone marrow was replaced by loosely arranged spindle cells

in a fine fibrous stroma (B and E, arrow). The control tibial

plateau showed normal healthy cartilage with normally distributed

chondrocytes (G) and tidemark wave-shaped (H, arrow). The red

coloration of the hyaline cartilage, reflecting proteoglycan

content, is homogenous and the surface of the cartilage is smooth.

The GlcN+OA tibial plateau showed the cartilage is lost, the

hyaline cartilage has reduced proteoglycans (loss of staining), a

reduced thickness (erosion) is diffusely hypocellular and clones

are present at the periphery of the changes (I and J). There

appears to be an increase in the number and size of bone lacunae

under the pits. The overlying hyaline cartilage in TXC+OA has

increased proteoglycans compared to the OA cartilage (K and L).

Mankin score analysis of the medial tibial plateau (M). Symbols

represent the means of averages ± SD and SD is shown as vertical

bars. **P<0.01, significant difference vs. the OA

group; ☆☆P<0.01, significant difference vs. the

control group. |

TXC delays chondrocyte and subchondral

bone degradation

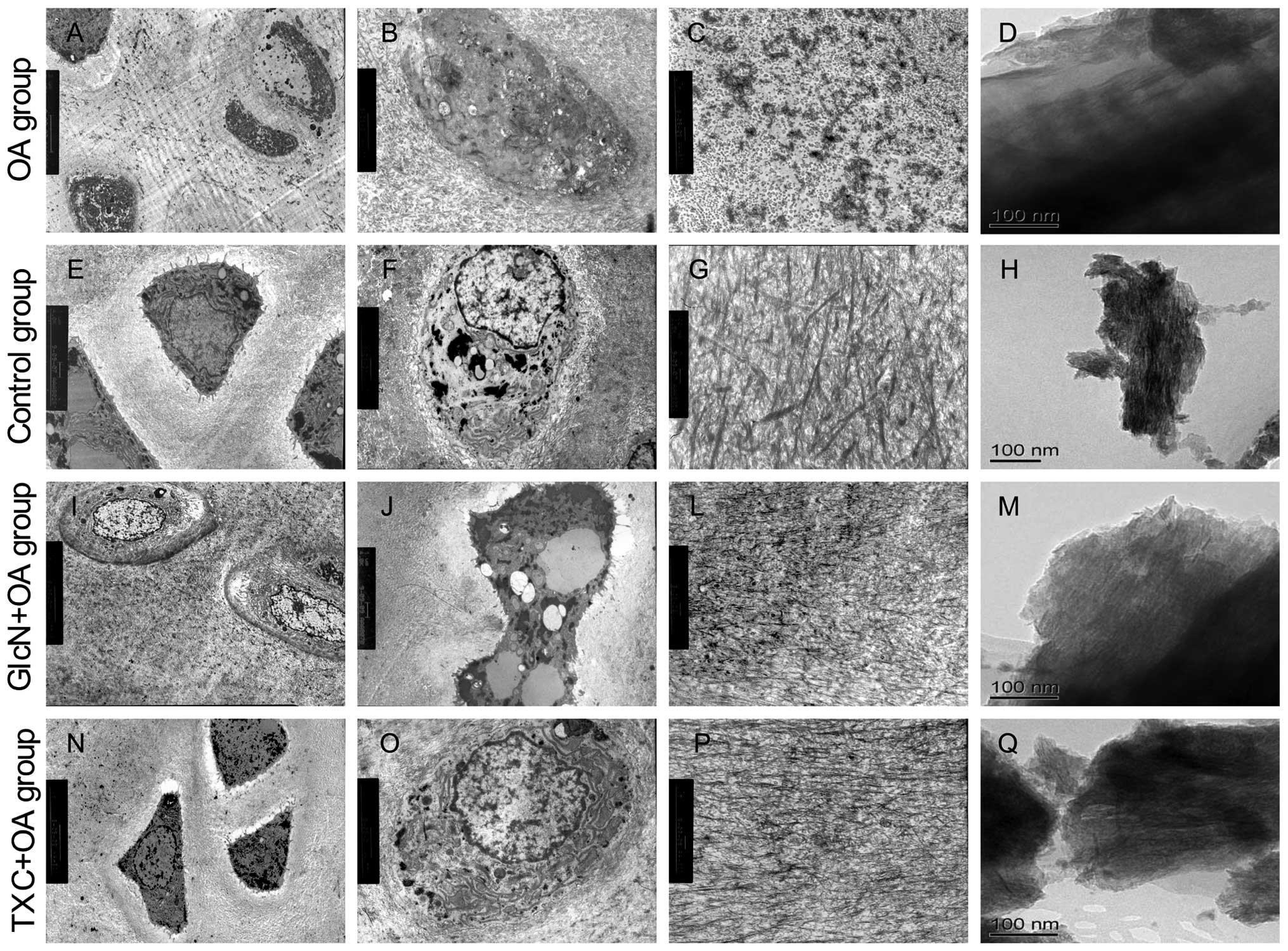

Ultrastructural study of tibial plateau cartilage in

both the TXC or GlcN and OA groups by TEM revealed distinctive

differences compared to control cartilages. The cartilage in the OA

group showed microscopic evidence of surface fibrillation, loss of

ECM staining in the superficial region for proteoglycans, several

apoptotic cells and reduced cellularity. Apoptotic cells were

shrunken and clearly retracted from the surrounding ECM. The

ultrastructural characteristics of apoptotic cells that we observed

were the presence of nuclear blebbing, apoptotic bodies and cell

shrinkage, whereas intensified staining of the cytoplasm, blebbing

of the cell membrane, and condensation of the chromatin were

observed less frequently (Fig. 3A and

B). The ECM contained degradation of several collagen fibers

(Fig. 3C).

The subchondral bone showed loosening and

irregularity of collagen arrangement, dense crystals of calcium and

phosphorus (Fig. 3D). The

cartilage in the control group showed chondrocytes were generally

round and characterized by several microvilli-like structures and

corrugations at the chondrocytic surface, some cells with the

characteristics of autophagosomes (Fig. 3E). The cytoplasm contained some

mitochondria and a relatively abundant number of organelles assumed

either rod-like or spherical morphology, and presented clearly

visible cristae. The nucleus of chondrocytes showed lobate or

indentation morphology, heterochromatin was observed preferentially

at the periphery of the nucleus (Fig.

3F). The ECM typically consists of a network of tightly packed

and highly cross-linked collagen fibrils (Fig. 3G). The subchondral bone showed

regularity of collagen arrangement, uniform distribution of calcium

phosphate crystals (Fig. 3H).

Markedly less severity of cartilage and subchondral bone

degradation was observed in the treatment with TXC or GlcN

(Fig. 3I–Q).

TXC enhances the autophagy-related

proteins against chondrocyte apoptosis

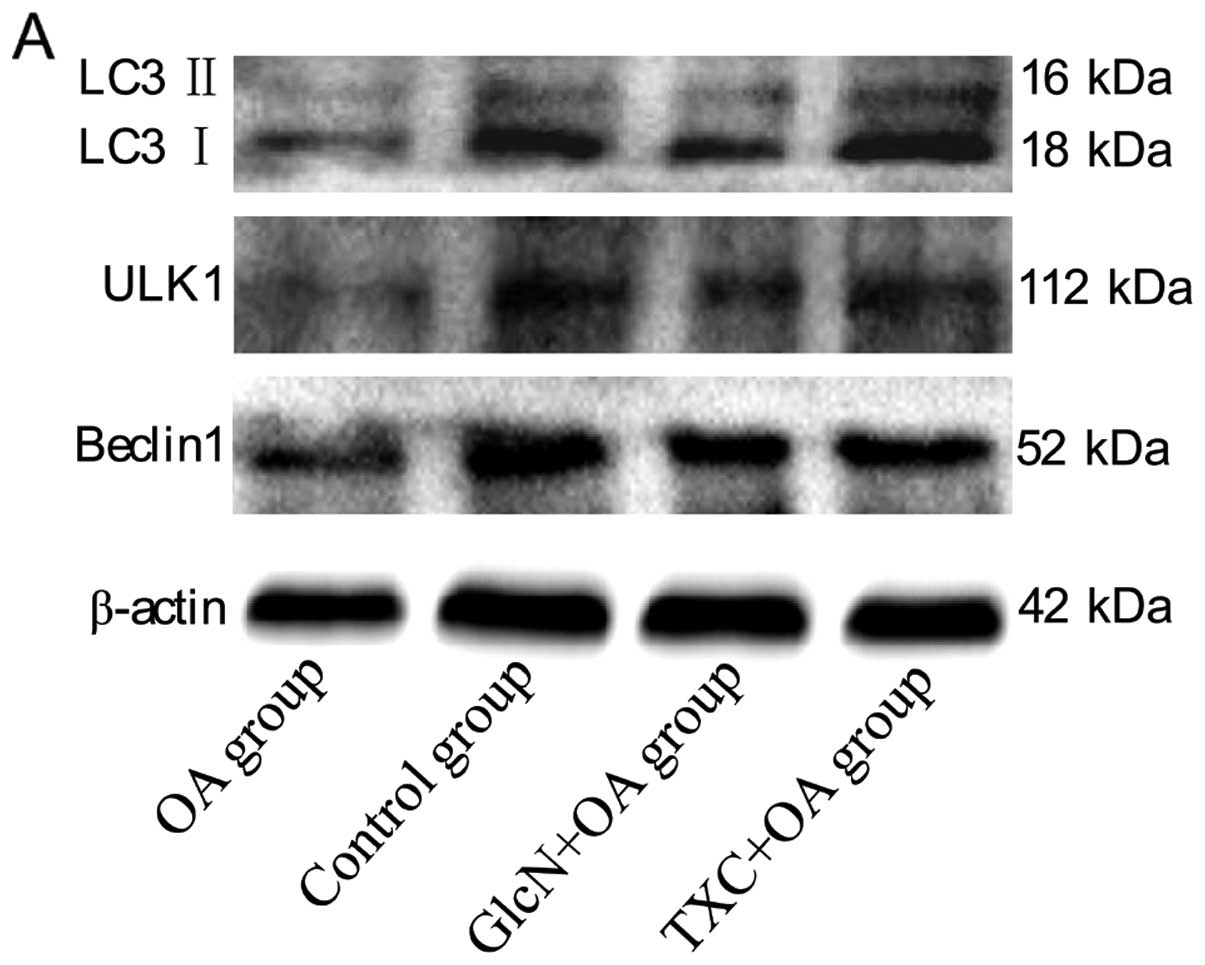

We then examined whether another type of cell death,

autophagy, was involved in OA pathogenesis. We first examined the

conversion of LC3 from an 18 kDa form (LC3 I) to a faster-migrating

16 kDa form (LC3 II), ULK1 and Beclin1. As shown in Fig. 4A–E, a western blot assay

demonstrated a decrease in LC3 I/II, ULK1 and Beclin1 levels in the

OA group compared to those in the control group (P<0.01).

However, LC3 I/II, ULK1 and Beclin1 levels in both the TXC and the

GlcN group significantly increased compared to those in the OA

group (P<0.05, P<0.01).

Discussion

The present study systematically evaluated the

cartilage protection mechanisms of TXC in papain-induced OA. Our

results clearly showed that TXC could improve the arrangement of

subchondral bone collagen fibers and calcium phosphate crystals,

inhibit the tidemark replication and delay the cartilage

degradation. In addition, our study showed that TXC upregulated the

protein levels of LC3 I/II, ULK1 and Beclin1, demonstrating that it

could inhibit the tidemark replication and cartilage degradation by

the activation of chondrocyte autophagy.

A number of treatment programs of OA have been

developed, such as medications with NSAIDs and chondroprotective

drugs. However, major problems associated with medications still

remain, particularly with the side-effects of NSAIDs. Thus, there

is a pressing need to develop alternative approaches to OA

treatment (17). Complementary

and alternative medicine is currently of interest to the general

public and the medical profession, and includes TCM. Chinese herbs

have relatively fewer-side effects compared to modern

chemotherapeutics and have long been used clinically to treat OA.

TXC, a famous TCM formulation, has been reported to be clinically

effective in treating OA by inhibiting chondrocyte apoptosis

(14). However, the molecular

mechanism of the therapeutic effect of TXC remains largely unknown.

Therefore, the present study examined whether TXC regulates the

tidemark replication and cartilage degradation by the regulation of

chondrocyte autophagy.

Tidemark, a distinct boundary between non-calcified

and calcified articular cartilage and not an artifact, has been

described as a haematoxyphil single line which is approximately

10-μm thick (18,19). Chondrocytes near the tidemark must

regulate the turnover of non-collagenous components in ECM and

maintain control over the local ECM (20). During normal development and

growth of diarthrodial joints, the tidemark clearly represents a

calcification front. In the normal adult joint, the tidemark is

still a single structure, ceases the advance of mineral into the

hyaline cartilage, although a residual ‘maintenance’ turnover of

ECM may occur (21). Under these

conditions, although the tidemark still contains some tightly bound

calcium, it may have ceased to function as a calcification front.

It is possible that the tidemark has changed in function to one of

inhibiting the growth or formation of microcrystals of

hydroxyapatite result in protecting the hyaline cartilage from

passive progressive mineralization at this stage. This may be an

irreversible change, so that if new mineralization is activated in

OA, a new tidemark may actively form distally to the original one,

leaving its predecessor as a non-functional relic, and thus

providing an explanation of tidemark replication. The tidemark

replication in OA is characterized by an endochondral ossification

process advancing calcification of zone IV and replacement of

calcified cartilage by new bone at the calcified cartilage-bone

interface, and these events must be precisely determined and

regulated by adjacent chondrocytes (22). Histological measures of articular

cartilage pathology, generally considered to be the reference

standard for presence and severity of OA, showed significant

tidemark replication and cartilage degradation in the OA group

compared to the control group, indicating that OA was successfully

induced by papain. In the present study, the TXC+OA group showed a

smaller increase in knee joint width and an inhibition of cartilage

degradation as compared to the OA group. Collectively, the above

findings support a role for TXC in the protection of cartilage and

chondrocyte metabolism, suggesting a possible mechanism by which

TXC may help to alleviate clinical signs and retard progression of

OA.

OA is a characterized by cartilage degradation and

subchondral bone changes. Microcracks in the calcified tissues may

enhance cellular activity leading to increased bone remodeling

(23,24). Although the relationship between

cartilage degradation and subchondral bone changes remains

controversial, the subchondral bone is considered to play an

important role in OA initiation and progression. During the OA

process, the subchondral bone would then become stiffer, causing a

reduced shock-absorbing capacity and leading to progression of

these lesions (25,26). However, other research shows that

the stiffness of subchondral bone in OA is actually decreased, due

to a reduced mineral content and an increased porosity (27). Further studies have shown the

phenomenon to be more complex and to involve changes in collagen

content and bone density, which potentially lead to weakened

subchondral trabecular bone (28,29). We found that the subchondral bone

degradation of the TXC+OA group significantly decreased compared to

the OA group, indicating the regulation of tide-mark replication by

affecting the arrangement of subchondral bone collagen fibers and

calcium phosphate crystals is one of the mechanisms by which TXC

may be effective in the treatment of OA.

Cell death can be classified according to

enzymological criteria, morphological appearance, immunological

characteristics or functional aspects. Based on morphological

criteria, three types of cell death can be defined; necrosis,

apoptosis and autophagy. Autophagy is a lysosomal degradation

pathway that is essential for differentiation, survival,

homeostasis and development. However, in certain physiological and

pathological conditions, autophagy can also result in a form of

cell death that is termed type II programmed cell death; the

morphological hallmark of autophagy forms the sequestering vesicle,

the autophagosome, which fuses with lysosomes and degrades and

recycles cellular components (30). Atg genes regulate the autophagy

process resulting in the induction and nucleation of autophagic

vesicles, their expansion and fusion with lysosomes, and the

enzymatic degradation and recycling (31,32). Among the Atg genes, Atg1, Atg5,

Atg6 and Atg8 (ULK1, Beclin1 and LC3 in mammals, respectively) are

four major regulators of the autophagy pathway. ULK1 is an

important intermediate in the transduction of pro-autophagic

signals to the formation of autophagosomes (33). Beclin1 forms a complex with Vps34

and type III PI3 kinase, and then allows nucleation of the

autophagic vesicle (34,35). Finally, the formation and

expansion of autophagosome demands two protein conjugation systems

including Atg12 and Atg proteins LC3 (36).

LC3 is the existence of two forms, LC3 II bound to

the autophagosome membrane and LC3 I in the cytoplasm. During the

autophagy process, LC3 I is converted to LC3 II through lipidation

by a ubiquitin-like system leading to the association of LC3 II

with autophagy vesicles. Therefore, the amount of LC3 II is

correlated with the extent of autophagosome formation (12,37). The present results showed that

autophagy was decreased in papain-induced OA, and the feature of

papain-induced cartilage degradation increased cell death

suggesting that loss of autophagy may contribute to cell death. Our

results also showed that the protein of LC3 I/II, ULK1 and Beclin1

in osteoarthritic cartilage was significantly decreased, and TXC

could increase these autophagy markers, demonstrating activation of

autophagy is one of the mechanisms by which TXC inhibits the

papain-induced cartilage degradation.

In summary, the protective role of autophagy in

endochondral ossification was further supported by observations

that its inactivation leads to severe skeletal abnormalities, due

in part to cell death (38). This

study confirmed that autophagy may be a protective or homeostatic

mechanism in normal cartilage. TXC could enhance chondrocyte

autophagy by promoting the expression of LC3 I/II, ULK1 and Beclin1

to inhibit the tidemark replication and cartilage degradation in

the papain-induced OA. These results suggested that compromised

autophagy may represent a novel avenue to delay the development of

OA. Since autophagy can serve to delay the onset of apoptosis,

further experiments are in progress to explore the mechanism of TXC

in the regulation of the relationship between the induction of

autophagy and apoptosis.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81102609),

the Key Project of Fujian Provincial Department of Science and

Technology (Grant no. 2012Y0046), the Natural Science Foundation of

Fujian Province (Grant no. 2011J05074) and the Young Talent

Scientific Research Project of Fujian Province Universities (Grant

no. JA12165).

References

|

1

|

Li X, Ye H, Yu F, et al: Millimeter wave

treatment promotes chondrocyte proliferation via G1/S

cell cycle transition. Int J Mol Med. 29:823–831. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wu MX, Li XH, Lin MN, et al: Clinical

study on the treatment of knee osteoarthritis of shensui

insufficiency syndrome type by electroacupuncture. Chin J Integr

Med. 16:291–297. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Galois L, Etienne S, Grossin L, et al:

Dose-response relationship for exercise on severity of experimental

osteoarthritis in rats: a pilot study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

12:779–786. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Panicker S, Borgia J, Fhied C, Mikecz K

and Oegema TR: Oral glucosamine modulates the response of the liver

and lymphocytes of the mesenteric lymph nodes in a papain-induced

model of joint damage and repair. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

17:1014–1021. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Eswaramoorthy R, Chang CC, Wu SC, Wang GJ,

Chang JK and Ho ML: Sustained release of PTH(1-34) from PLGA

microspheres suppresses osteoarthritis progression in rats. Acta

Biomater. 8:2254–2262. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bonde HV, Talman ML and Kofoed H: The area

of the tidemark in osteoarthritis - a three-dimensional

stereological study in 21 patients. APMIS. 113:349–352. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lyons TJ, Stoddart RW, McClure SF and

McClure J: The tidemark of the chondro-osseous junction of the

normal human knee joint. J Mol Histol. 36:207–215. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Dequeker J, Mokassa L, Aerssens J and

Boonen S: Bone density and local growth factors in generalized

osteoarthritis. Microsc Res Tech. 37:358–371. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Del Carlo M Jr and Loeser RF: Cell death

in osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 10:37–42. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Almonte-Becerril M, Navarro-Garcia F,

Gonzalez-Robles A, Vega-Lopez MA, Lavalle C and Kouri JB: Cell

death of chondrocytes is a combination between apoptosis and

autophagy during the pathogenesis of Osteoarthritis within an

experimental model. Apoptosis. 15:631–638. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim HA, Lee YJ, Seong SC, Choe KW and Song

YW: Apoptotic chondrocyte death in human osteoarthritis. J

Rheumatol. 27:455–462. 2000.

|

|

12

|

Caramés B, Taniguchi N, Otsuki S, Blanco

FJ and Lotz M: Autophagy is a protective mechanism in normal

cartilage, and its aging-related loss is linked with cell death and

osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 62:791–801. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Lotz MK and Caramés B: Autophagy and

cartilage homeostasis mechanisms in joint health, aging and OA. Nat

Rev Rheumatol. 7:579–587. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li XH, Wu MX, Ye HZ, et al: Experimental

study on the suppression of sodium nitroprussiate-induced

chondrocyte apoptosis by Tougu Xiaotong Capsule-containing serum.

Chin J Integr Med. 17:436–443. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kellgren JH and Lawrence JS: Radiological

assessment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheheum Dis. 16:485–493.

1957. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Mankin HJ, Dorfman H, Lippiello L and

Zarins A: Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular

cartilage from osteoarthritic human hips. II. Correlation of

morphology with biochemical and metabolic data. J Bone Joint Surg

Am. 53:523–537. 1971.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Klop C, de Vries F, Lalmohamed A, et al:

COX-2-selective NSAIDs and risk of hip or knee replacements: a

population-based case-control study. Calcif Tissue Int. 91:387–394.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zoeger N, Roschger P, Hofstaetter JG, et

al: Lead accumulation in tidemark of articular cartilage.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 14:906–913. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gannon FH and Sokoloff L: Histomorphometry

of the aging human patella: histologic criteria and controls.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 7:173–181. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Meirer F, Pemmer B, Pepponi G, et al:

Assessment of chemical species of lead accumulated in tidemarks of

human articular cartilage by X-ray absorption near-edge structure

analysis. J Synchrotron Radiat. 18:238–244. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Otterness IG, Chang M, Burkhardt JE,

Sweeney FJ and Milici AJ: Histology and tissue chemistry of

tidemark separation in hamsters. Vet Pathol. 36:138–145. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Pan J, Wang B, Li W, et al: Elevated

cross-talk between subchondral bone and cartilage in osteoarthritic

joints. Bone. 51:212–217. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lacourt M, Gao C, Li A, et al:

Relationship between cartilage and subchondral bone lesions in

repetitive impact trauma-induced equine osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 20:572–583. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bobinac D, Spanjol J, Zoricic S and Maric

I: Changes in articular cartilage and subchondral bone

histomorphometry in osteoarthritic knee joints in humans. Bone.

32:284–290. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Burr DB: Increased biological activity of

subchondral mineralized tissues underlies the progressive

deterioration of articular cartilage in osteoarthritis. J

Rheumatol. 32:1156–1158. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Botter SM, Glasson SS, Hopkins B, et al:

ADAMTS5−/− mice have less subchondral bone changes after induction

of osteo-arthritis through surgical instability: implications for a

link between cartilage and subchondral bone changes. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 17:636–645. 2009.

|

|

27

|

Day JS, Ding M, van der Linden JC, Hvid I,

Sumner DR and Weinans H: A decreased subchondral trabecular bone

tissue elastic modulus is associated with pre-arthritic cartilage

damage. J Orthop Res. 19:914–918. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bennell KL, Creaby MW, Wrigley TV and

Hunter DJ: Tibial subchondral trabecular volumetric bone density in

medial knee joint osteoarthritis using peripheral quantitative

computed tomography technology. Arthritis Rheum. 58:2776–2785.

2008.

|

|

29

|

Aula AS, Töyräs J, Tiitu V and Jurvelin

JS: Simultaneous ultrasound measurement of articular cartilage and

subchondral bone. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 18:1570–1576. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM and

Klionsky DJ: Auto-phagy fights disease through cellular

self-digestion. Nature. 451:1069–1075. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Srinivas V, Bohensky J, Zahm AM and

Shapiro IM: Autophagy in mineralizing tissues: microenvironmental

perspectives. Cell Cycle. 8:391–393. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Cajee UF, Hull R and Ntwasa M:

Modification by ubiquitin-like proteins: significance in apoptosis

and autophagy pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 13:11804–11831. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Chan EY, Kir S and Tooze SA: siRNA

screening of the kinome identifies ULK1 as a multidomain modulator

of autophagy. J Biol Chem. 282:25464–25474. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Furuya N, Yu J, Byfield M, Pattingre S and

Levine B: The evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin 1 is

required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor suppressor

function. Autophagy. 1:46–52. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Abounit K, Scarabelli TM and McCauley RB:

Autophagy in mammalian cells. World J Biol Chem. 3:1–6. 2012.

|

|

36

|

Ohsumi Y and Mizushima N: Two

ubiquitin-like conjugation systems essential for autophagy. Semin

Cell Dev Biol. 15:231–236. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al: LC3,

a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome

membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19:5720–5728. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Settembre C, Arteaga-Solis E, McKee MD, et

al: Proteoglycan desulfation determines the efficiency of

chondrocyte autophagy and the extent of FGF signaling during

endochondral ossification. Genes Dev. 22:2645–2650. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|