Introduction

The early repolarization pattern consisting of a

J-point elevation, notching or slurring of the terminal portion of

the R wave (J wave) and tall/symmetric T wave is a common finding

on the electrocardiography (ECG) in young healthy men or athletes

and is considered a ‘benign’ ECG manifestation for a long period of

time (1–3). However, recent evidence has

demonstrated that early repolarization may be associated with an

increased risk for ventricular fibrillation (VF), depending on the

locations and magnitude of the J wave and ST-segment elevation

(4,5). Thus, Antzelevitch and Yan (1) proposed a new conceptual framework,

inherited J wave syndromes, to describe the arrhythmic phenotypes.

Inherited J wave syndromes, as a continuous spectrum of arrhythmic

phenotypes, has been divided into four different subtypes in terms

of anatomical locations of J wave and ST-segment elevation and

clinical consequences, including early repolarization in the

lateral precordial leads [early repolarization syndrome (ERS) type

1], in the inferior or inferolateral leads (ERS type 2), globally

in the inferior, lateral and right precordial leads (ERS type 3)

and in the right precordial leads [Brugada syndrome (BrS)]

(1). However, the genetic basis

of the three types of ERS has not been well defined. To date,

‘loss-of-function’ mutations in the CACNA1C, CACNB2

and CACNA2D1 genes and ‘gain-of-function’ mutations in the

KCNJ8 gene have been identified in patients with ERS

(6–8).

In the present study, we described an unreported

missense mutation of c.4297 G>C in the SCN5A gene, which

encoded the α subunit of the cardiac voltage-gated sodium channel

Nav1.5, leading to prominent J waves and ST-segment elevation in

the inferior, lateral and precordial leads accompanied with VF in a

female proband. We identified an unpublished synonymous single

nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of T5457C in the SCN5A gene in

the proband, her mother and sister. We characterized the functional

consequences of the mutation as well as the interaction between the

mutation and the SNP.

Materials and methods

Clinical examination

The proband and her first-degree relatives underwent

clinical evaluation, including medical history, physical

examination and 12-lead ECG and echocardiographic examinations

(Figs. 1 and 2). The study conformed to the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The institutional ethics

committee approved all the research protocols and written informed

consents were obtained from all participants.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood

leukocytes using a TIANamp Blood DNA isolation kit (Tiangen,

Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All

exons of the SCN5A, KCND3, CACNA1C,

CACNB2, KCNE3, SCN1B and KCNJ8 genes

were amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and were analyzed

by direct sequencing. Whenever the variant was discovered in the

proband or her family members, it would be confirmed in 500

unrelated healthy Chinese individuals (1,000 reference alleles) to

determine the distinction between mutation and polymorphism.

Mutagenesis and expression studies

The technique for site-directed mutagenesis and

wild-type (WT)-SCN5A plasmid were prepared in our laboratory

(9). Three mutations based on the

genotypes of the patient and her family (c.4297 G>C -SCN5A,

T5457C-SCN5A and c.4297 G>C-T5457C-SCN5A) were created on the

WT-SCN5A background (GenBank ID: NM198056). All mutations were

verified by sequencing and then subcloned back into the pcDNA3.1

vector. The heterologous expression was performed as previously

described (9). Briefly, the human

embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells were transiently transfected with

0.6 μg cDNA (detailed composition is shown in Table I) using an Effectene Transfection

Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s

protocol. Green fluorescent protein gene (0.2 μg) was cotransfected

as an indicator. The transfected cells were cultured for 36 h

before sodium current (INa) was recorded. More

than 3 independent experiments were conducted to confirm the

reproducibility of the results.

| Table IAverage values of activation,

inactivation and recovery from inactivation parameters. |

Table I

Average values of activation,

inactivation and recovery from inactivation parameters.

| | Steady-state

activation | Steady-state

inactivation | Recovery from

inactivation |

|---|

| |

|

|

|

|---|

| Channels | N | V1/2,

mV | k | V1/2,

mV | k | τf,

msec | τs,

msec | Af |

|---|

| WT-SCN5A (0.6

μg) | 8 | −50.72±1.46 | 3.61±0.32 | −88.61±0.78 | 5.28±0.14 | 24.25±4.26 | 189.94±14.56 | 0.70±0.01 |

| G4297C-SCN5A (0.6

μg) | 9 | −39.07±1.80a | 6.18±0.36a | −91.39±1.95 | 4.79±0.47 | 66.01±4.94a | 257.99±8.84a | 0.54±0.01a |

| T5457C-SCN5A (0.6

μg) | 8 | −47.26±2.34 | 4.50±0.54 | −90.91±1.00 | 5.35±0.17 | 29.38±3.44 | 248.93±6.95a | 0.50±0.02a |

| G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A

(0.6 μg) | 8 | −40.78±2.19a | 5.29±0.35a | −85.71±1.96 | 4.78±0.31 | 56.46±2.48a | 244.10±9.11a | 0.52±0.01a |

| G4297C-SCN5A +

T5457C-SCN5A (0.3 + 0.3 μg) | 7 | −39.10±2.69a | 5.46±0.42a | −88.64±0.86 | 5.03±0.25 | 46.43±4.36a |

232.85±10.55a | 0.50±0.01a |

| WT-SCN5A +

G4297C-SCN5A (0.3 + 0.3 μg) | 5 | −46.01±2.57 | 4.91±0.68 | −87.56±0.98 | 5.55±0.16 | 25.92±4.20 | 204.75±9.81 | 0.69±0.01 |

| WT-SCN5A +

T5457C-SCN5A (0.3 + 0.3 μg) | 5 | −47.87±3.13 | 3.99±1.80 | −87.97±1.99 | 5.36±0.27 | 27.43±3.65 |

258.76±12.74a | 0.56±0.02a |

| WT-SCN5A +

G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A (0.3 + 0.3 μg) | 9 | −42.60±1.77a | 5.31±0.44a | −85.21±1.53 | 5.09±0.27 | 47.05±6.09a |

236.03±10.13a | 0.49±0.02a |

| T5457C-SCN5A +

G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A (0.3 + 0.3 μg) | 5 | −43.72±2.51a | 4.89±0.43a | −88.67±2.94 | 5.66±0.30 | 51.47±7.14a |

252.87±13.82a | 0.51±0.01a |

Patch-clamping

INa was measured using whole-cell

configuration of the patch-clamp technique as previously described

(10) with Axonpatch 700B

amplifiers (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA). The resistance

of pipettes in the bath solution ranged from 1.5 to 2 MΩ. For

whole-cell recording, the internal pipette solution contained (in

mmol/l) CsF 120, CsCl 20, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid 2.0,

MgCl2 1.0 and HEPES 5 (pH 7.4). The bath solution

contained (in mmol/l) NaCl 30, CsCl 110, CaCl2 1.8,

MgCl2 1.0 and HEPES 10 (pH 7.4). No leak subtraction was

applied during recording. All measurements were obtained at room

temperature (20–22°C).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time

PCR

Total RNA was extracted from transfected HEK293

cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad,

CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The

concentration of RNA was determined by the UV Visible

spectrophotometer and 1 μg total RNA was subsequently

reverse-transcribed to cDNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus

reverse transcriptase (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA).

Quantitative real-time PCR (11)

was performed on an ABI 7300 real-time PCR instrument (Applied

Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the GAPDH gene, whose

expression is very stable in HEK293 cells, as an internal control

for data normalization. The primers were as follows: forward,

5′-GAGATGCTGCAGGTCGGAAAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GATGACGATGATGCTGTCGAAGA-3′. The PCR cycles consisted of

denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing and extension at 60°C

for 1 min for 40 cycles. Each sample was analyzed 3 times. The

2−ΔΔCt method was used to analyze the relative

expression of protein.

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical experiments were performed as

previously described (12).

Briefly, cells were fixed, blocked and incubated with mouse

monoclonal to Nav1.5 IgM primary antibody (1:40 dilution) (Abcam,

Cambridge, UK) overnight at 4°C. The cells were then incubated in

anti-mouse FITC-conjugated donkey secondary antibody (1:500

dilution) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h at

room temperature in the dark. Confocal images were obtained using a

confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP2; Leica, Wetzlar,

Germany) and were analyzed with NIH image software (Image J).

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as the means ± standard error

of the mean (SEM). Student’s t-test analysis was performed for the

comparison of two means, while one-way ANOVA was performed for

comparisons of multiple means using statistical software SPSS 13.0.

A value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Clinical manifestation and

genotyping

The proband, a 19-year-old female was admitted to

the Fu Wai Hospital (Beijing, China) due to a history of recurrent

syncope at rest (a total of 4 times since the age of 16). The ECG

that was obtained at the emergency department exhibited prominent J

waves and ST-segment elevation in leads I, II, III, aVF and

V2–V6 (Fig.

2B) before VF occurred (Fig.

2C). Subsequently, the VF episode was terminated by

cardioversion. There was no difference in clinical state that may

explain the marked J waves and ST-segment elevation in the

documented ECG. Myocardial infarction was excluded by cardiac

enzyme tests and coronary angiography. The routine echocardiography

demonstrated a structural and functional normal heart. The baseline

ECG was within normal limits with the exception of tiny, hump-like

J waves in the inferior leads and a borderline prolongation of the

PR interval (200 msec) (Fig. 2A).

The amplitude of ST-segment elevation fluctuated from day to day.

Programmed electrical stimulation induced VF that was converted to

sinus rhythm by cardioversion. Since the sodium channel blockers,

such as ajmaline, flecainide and procainamide, were not available

in China, drug challenge was not performed. According to the

clinical manifestations, ERS type 3 was diagnosed and an

implantable cardioverter defibrillator was implanted with the

pacing rate programmed to 60 bpm. After amiodarone (200 mg/day) and

metoprolol (50 mg/day) administration, the proband remained

symptom-free for a period of 18 months. However, in the nineteenth

month, the patient was shocked due to a VF episode with a heart

rate >260 bpm. All family members lived asymptomatic and there

was no family history of sudden death.

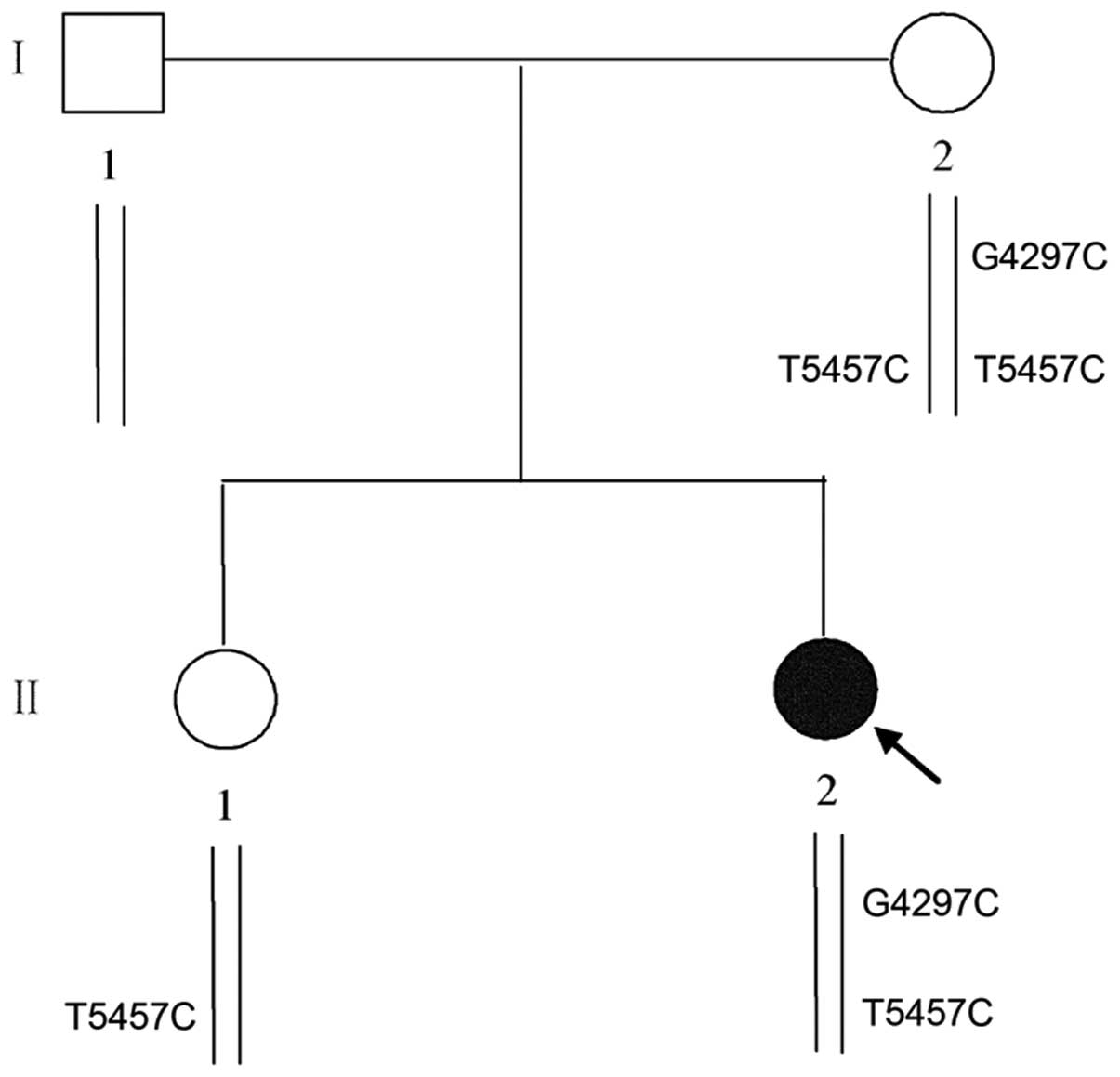

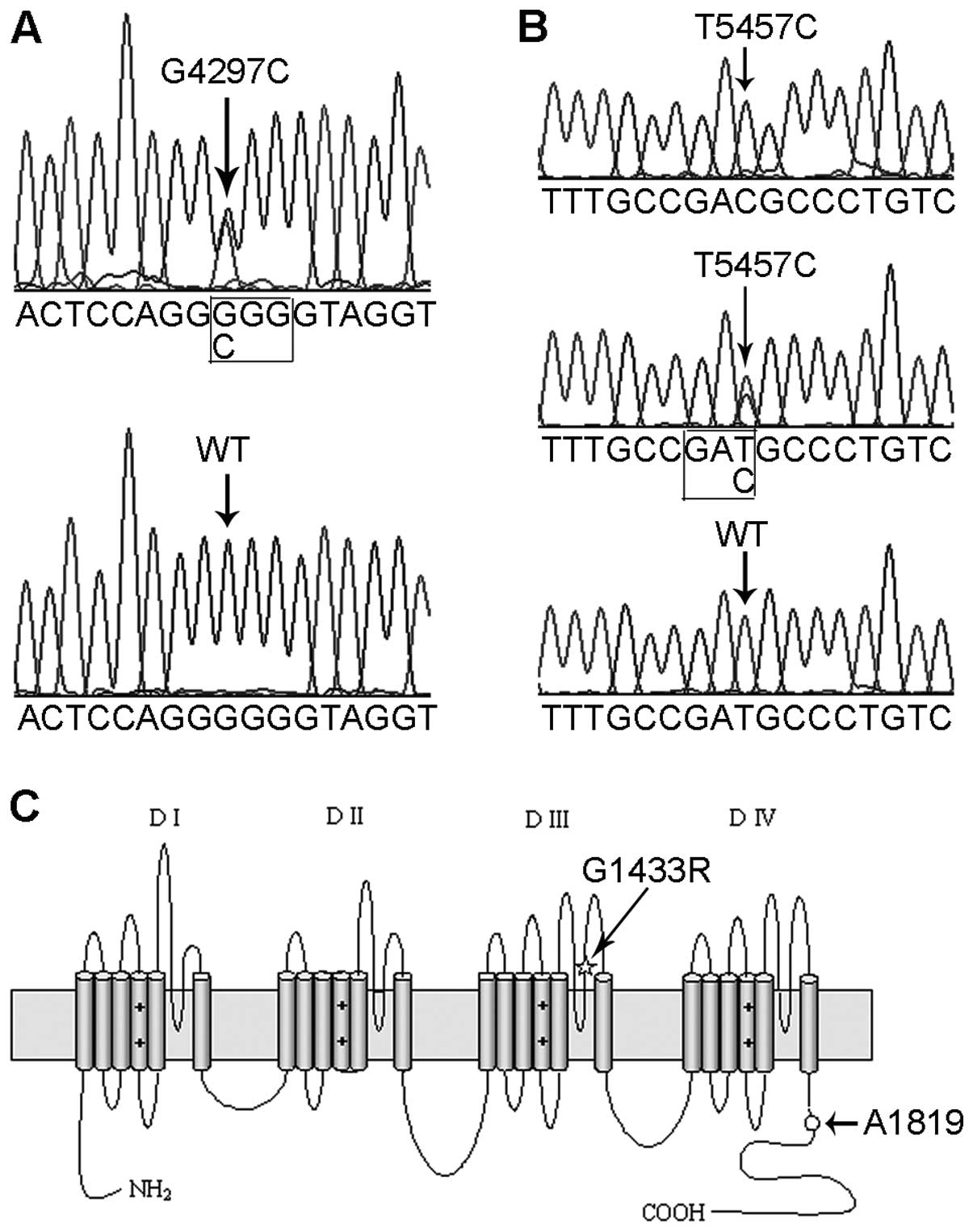

A heterozygous missense mutation of c.4297 G>C,

located in exon 24 of the SCN5A gene, was identified in the

proband using direct DNA sequencing (Fig. 3A). The mutation led to a

substitution of an arginine for a glycine at position 1433 that was

predicted to be in the extracellular loop between the pore region

and the S6 transmembrane segment in the domain III of the α subunit

of the sodium channels (Fig. 3C).

The c.4297 G>C mutation was also detected in her mother but not

in 500 unrelated healthy subjects. In addition, a heterozygous SNP,

T5457C, which is located in exon 28 of the SCN5A gene, was

discovered in the proband; however, the T5457C polymorphism did not

cause a change in the protein sequence (Fig. 3B and C). Genetic analysis revealed

that her mother carried a homozygous T5457C polymorphism and her

sister carried a heterozygous T5457C polymorphism, while her

farther carried no such variants (Fig. 1). Since the substitution of C for

T occurred at a frequency of 42.67% within a population including

500 unrelated healthy subjects, we confirmed that the T5457C

variant was a polymorphism. Moreover, no other mutations or

variants were discovered in the screened genes in the proband and

the family.

Electrophysiology of G4297C and T5457C

channels

INa was recorded from the HEK293

cells transiently transfected with the WT-SCN5A, G4297C-SCN5A or

T5457C-SCN5A plasmid using the whole-cell configuration of the

patch-clamp technique. The G4297C mutation dramatically reduced

INa density (−107.65±14.70 pA/pF in WT, n=8 vs.

−15.75±3.72 pA/pF in the mutant, n=12, P<0.05) (Fig. 4A and C) and shifted the

steady-state activation curve to a more positive potential compared

with the WT channels (P<0.05) (Fig. 5C and Table I). By contrast, the mutation had

no effect on the steady-state inactivation (Fig. 5D and Table I), although it inhibited the

recovery from inactivation (P<0.05) (Fig. 5B and Table I).

The T5457C variant was a relative benign

polymorphism since it did not change the current density

(−115.47±23.25 pA/pF, n=8, P>0.05) (Fig. 4B), steady-state activation and

steady-state inactivation of the sodium channels, although it

prolonged the recovery from inactivation compared with the WT

channels (P<0.05) (Table

I).

Rescue effect of the T5457C polymorphism

on G4297C mutant channels

Furthermore, we characterized the interaction

between the G4297C mutation and the T5457C polymorphism. Inserting

the T5457C polymorphism into the G4297C mutant construct

(G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A) partially restored the INa

density (−44.12±10.45 pA/pF, n=8) (P<0.05, Fig. 4D) but without having an effect on

mutant channel kinetics compared with the G4297C channels (Table I). However, coexpression of the

T5457C polymorphism and G4297C mutation on separate constructs had

no significant effect on the INa density of

mutant channels, since the similar current densities were recorded

from cells coexpressing G4297C-SCN5A and WT or T5457C-SCN5A

(−55.66±18.01 pA/pF, n=7 vs. −61.02±17.80 pA/pF, n=5, P>0.05)

(Fig. 4E and F). Additionally, we

expressed the cDNA constructs to simulate the distribution patterns

of G4297C and T5457C in the proband and her family. Coexpression of

G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A with WT-SCN5A (as the nature of the proband) or

G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A with T5457C-SCN5A (as the nature of her mother)

increased the INa up to 65 or 70% in the WT

channels. The peak current densities are plotted in Fig. 5A for all combinations of WT-SCN5A,

G4297C-SCN5A, T5457C-SCN5A and G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A constructs.

Transcription of WT and mutant cDNAs

Quantitative real-time PCR was used to detect the WT

and mutant mRNA levels. The mRNA of SCN5A was not detected in the

non-transfected cells. There was no significant difference in mRNA

levels between cells transfected with WT-SCN5A and the G4297C

mutant (P>0.05). The mRNA level of G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A was

increased by 6-fold compared to that of WT-SCN5A (P<0.05).

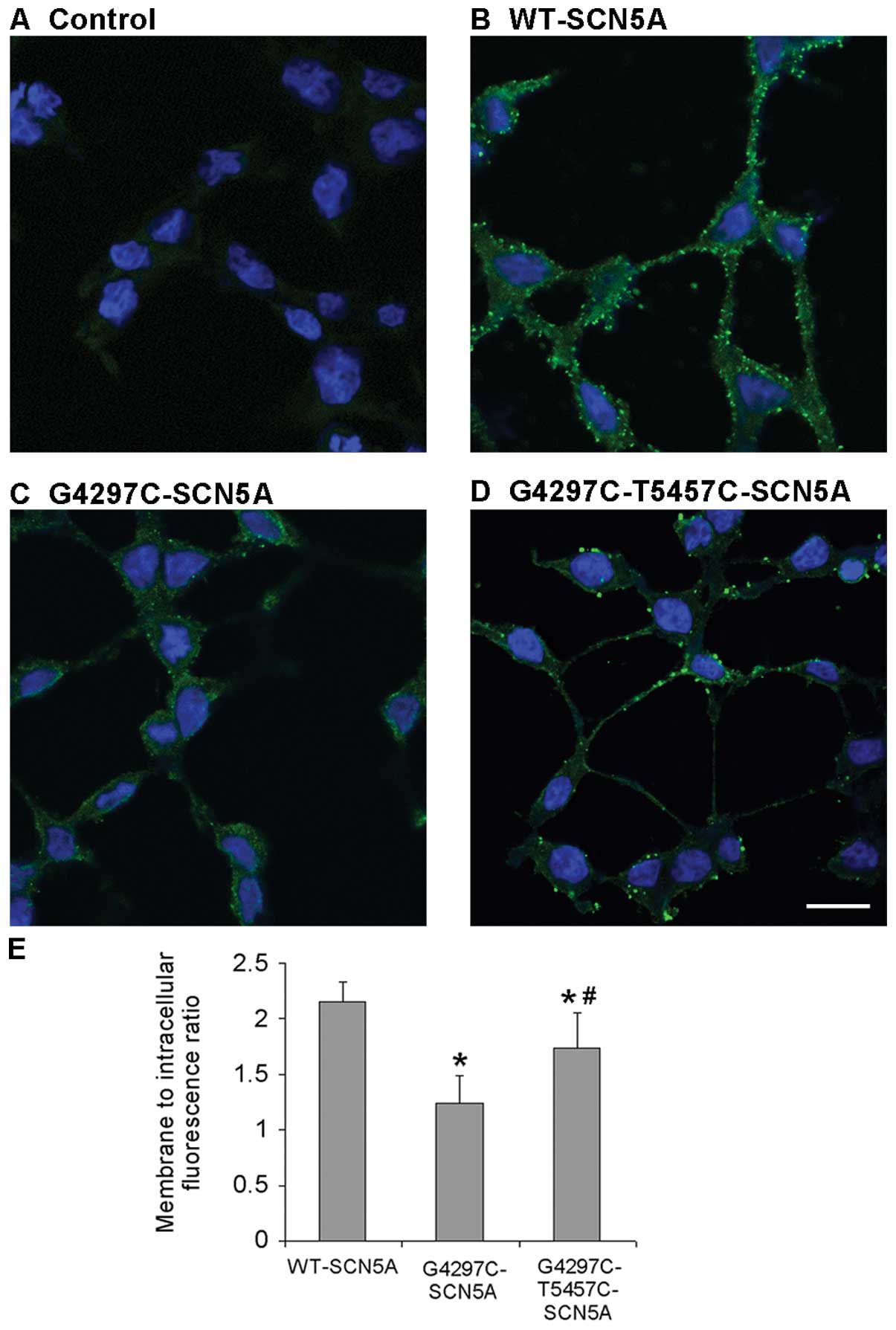

Confocal imaging

To investigate the cellular localization of the WT

and mutant channels, immunocytochemical experiments were performed.

The non-transfected cells displayed background fluorescence

(Fig. 6A). As expected, the

periphery localization was exhibited in cells with WT channels

(Fig. 6B). By contrast, cells

transfected with G4297C mutant channels displayed a very low

expression both in the cell membrane and in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6C). However, the G4297C-T5457C

channels demonstrated a significantly higher expression with a

peripheral localization pattern compared to that of the G4297C

channels, consistent with the increased mRNA levels of

G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A compared with the G4297C channels, which

indicated that the T5457C polymorphism partially rescued the

expression of G4297C mutant channels (Fig. 6D). Summary data depicted in

Fig. 6E revealed that the average

fluorescence intensity per unit area in the membrane divided by the

average fluorescence intensity per unit area in intracellular

compartments (membrane to intracellular fluorescence ratio) was

markedly reduced in the G4297C group compared to that in the WT

group (P=0.0007); however, the ratio significantly increased in the

G4297C-T5457C group compared with the G4297C group (P=0.017) (n=10

for all groups).

Discussion

In this study, we identified an unreported

SCN5A mutation G4297C in a young female patient with

idiopathic VF followed by J waves and ST-segment elevation in the

inferior, lateral and precordial leads demonstrated by documented

ECG. According to the clinical manifestation of the lack of typical

Brugada waves in the right precordial V1 lead, the

patient was not diagnosed as BrS (13,14). Recently, a multicenter study

revealed that J wave and ST-segment elevation in the inferior or

lateral leads, also termed as early repolarization (15,16), accounted for 31% of 206 patients

with idiopathic VF (4). It has

also been reported that up to 11% of patients with BrS presented J

wave and ST-segment elevation in the inferior-lateral leads

associated with an increased number of symptoms (5). Therefore, the nomenclature of ERS or

BrS remains unclear. Based on the new conceptual framework proposed

by Antzelevitch and Yan (1), our

patient may be diagnosed as ERS type 3.

In the present study, we reported a missense G4297C

mutation in the SCN5A gene. After excluding variants in

other genes associated with ERS (6–8)

and BrS (17), including

KCND3, CACNA1C, CACNB2, KCNE3,

SCN1B and KCNJ8, we speculated that the G4297C

mutation in the SCN5A gene was the causative mutation. The

patch-clamp study demonstrated that the G4297C mutation caused a

significant decrease in INa density as well as

altered biophysical characteristics of sodium channels such as

prolonged recovery time from inactivation and depolarizing shift in

activation. The altered properties predisposed the sodium channels

to a ‘loss-of-function’. Further study demonstrated that the mRNA

levels of WT and G4297C mutant channels were similar. However,

immunocytochemistry demonstrated that the G4297C mutant channels

displayed a very low expression both in the cell membrane and in

the cytoplasm. The result suggests that G4297C does not cause a

trafficking defect (18), in

contrast, it affects the translation process or degradation of the

mutant protein. This mechanism differs from three well-known

primary mechanisms that cause a ‘loss-of-function’ of sodium

channels such as i) formation of nonfunctional channels; ii)

altered gating properties; and iii) defective trafficking (18,19). Thus, our findings may represent a

novel mechanism for the ‘loss-of-function’ of sodium channels.

Moreover, several studies found that the R282H

mutation in the SCN5A gene, which leads to BrS, may be fully

rescued by the H558R polymorphism that restores the trafficking of

the mutant protein (20,21). The rescue effect of the synonymous

polymorphism T5457C identified in our study has not yet been

investigated. Our study demonstrated that T5457C did partially

restore the G4297C mutant channels based on the fact that the mRNA

level of the G4297C-T5457C-SCN5A mutant significantly increased

compared to that of the G4297C mutant, corresponding to a

concomitant proportional increase in the number of sodium channels

on the cell surface. A similar phenomenon has been observed in the

ABCC2 gene that encodes the multidrug resistance-associated

protein 2 (MRP2). The synonymous C1146G SNP in the ABCC2

gene increased MRP2 mRNA expression by 2-fold in human livers

(22). However, the essential

mechanism by which a synonymous SNP increases mRNA expression

remains unclear. Several studies have focused on the possibility

that the synonymous SNP alters the stability of mRNA, a phenomenon

suggested by the synonymous C3435T SNP in the ABCB1 gene,

encoding multidrug resistance polypeptide 1 and the synonymous

C971T SNP in the CDSN gene encoding corneodesmosin (23,24). Another explanation was that the

SNP may be in linkage disequilibrium with other polymorphism(s)

acting at the transcriptional level (22).

At present, the transmural voltage gradient mediated

by the transient outward current (Ito) during the

early repolarization phase has been accepted as an explanation of

the pathophysiological mechanism of J wave or ST-segment elevation

on the ECG when the corresponding inward INa was

reduced (25).

Ito was often more prominent in the epicardium of

the right ventricle compared to that of the left ventricle

(26), and therefore, ST-segment

elevation was predisposed to localizing in the right precordial

leads, as noted in BrS. By contrast, in our study, the J waves and

ST-segment elevation of the proband were confined to the inferior,

lateral and left precordial leads. The possible explanation may be

associated with the gender-related difference in

Ito distribution. In the human ventricle, the

transmural Ito gradient is formed by the

differential expression of KChIP2, the gene encoding the β

subunit of the Ito (27). The expression of KChIP2

gene is negatively regulated via the homeodomain Iroquois

transcription factor IRX5 and IRX3 (28). Recently, Gaborit et al

(28) provided evidence that the

expression of KChIP2 is increased in the female left

ventricle, consistent with the decreased expression of IRX3

and IRX5 compared with the right ventricle. The distinction

of expression levels of KChIP2, IRX3 and IRX5

between male and female hearts may cause the J waves and ST-segment

elevation in the inferior, lateral and left precordial leads in

female patients as noted in our proband.

We reported a missense mutation of G4297C in the

SCN5A gene, which caused the ‘loss-of-function’ of sodium

channels, leading to the clinical phenotype of ERS type 3. Our

findings may represent a novel mechanism for the ‘loss-of-function’

of sodium channels by decreasing the number of sodium channels due

to abnormal translation processes. The synonymous T5457C

polymorphism may partially restore the function of the G4297C

mutant channels through the upregulation of mRNA levels. However,

several limitations existed in this study. First, the reasons for

incomplete penetrance in patient I–2 depicted in Fig. 1 were not elucidated. Second,

although the probability was very low, it was unclear whether the

reported mutation and the SNP were on the same allele. The reason

why the T5457C SNP prolonged the recovery from the inactivation of

the sodium channels requires further investigation.

Acknowledgements

The National Basic Research Program of China (973

program, 2007CB512000 and 2007CB512008) provided support to J. Pu

for this research.

References

|

1

|

Antzelevitch C and Yan GX: J wave

syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 7:549–558. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Miyazaki S, Shah AJ and Haïssaguerre M:

Early repolarization syndrome - a new electrical disorder

associated with sudden cardiac death. Circ J. 74:2039–2044.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yan GX, Lankipalli RS, Burke JF, Musco S

and Kowey PR: Ventricular repolarization components on the

electrocardiogram: cellular basis and clinical significance. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 42:401–409. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Haïssaguerre M, Derval N, Sacher F, Jesel

L, Deisenhofer I, de Roy L, Pasquié JL, Nogami A, Babuty D,

Yli-Mayry S, et al: Sudden cardiac arrest associated with early

repolarization. N Engl J Med. 358:2016–2023. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sarkozy A, Chierchia GB, Paparella G,

Boussy T, De Asmundis C, Roos M, Henkens S, Kaufman L, Buyl R,

Brugada R, et al: Inferior and lateral electrocardiographic

repolarization abnormalities in Brugada syndrome. Circ Arrhythm

Electrophysiol. 2:154–161. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Haïssaguerre M, Chatel S, Sacher F,

Weerasooriya R, Probst V, Loussouarn G, Horlitz M, Liersch R,

Schulze-Bahr E, Wilde A, et al: Ventricular fibrillation with

prominent early repolarization associated with a rare variant of

KCNJ8/KATP channel. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 20:93–98.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Medeiros-Domingo A, Tan BH, Crotti L,

Tester DJ, Eckhardt L, Cuoretti A, Kroboth SL, Song C, Zhou Q, Kopp

D, et al: Gain-of-function mutation, S422L, in the KCNJ8-encoded

cardiac K(ATP) channel Kir6.1 as a pathogenic substrate for J-wave

syndromes. Heart Rhythm. 7:1466–1471. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Burashnikov E, Pfeiffer R,

Barajas-Martinez H, Delpón E, Hu D, Desai M, Borggrefe M,

Häissaguerre M, Kanter R, Pollevick GD, et al: Mutations in the

cardiac L-type calcium channel associated with inherited J-wave

syndromes and sudden cardiac death. Heart Rhythm. 7:1872–1882.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Teng S, Gao L, Paajanen V, Pu J and Fan Z:

Readthrough of nonsense mutation W822X in the SCN5A gene can

effectively restore expression of cardiac Na+ channels.

Cardiovasc Res. 83:473–480. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B and

Sigworth FJ: Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution

current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches.

Pflugers Arch. 391:85–100. 1981. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Okada T, Ding G, Sonoda H, Kajimoto T,

Haga Y, Khosrowbeygi A, Gao S, Miwa N, Jahangeer S and Nakamura S:

Involvement of N-terminal-extended form of sphingosine kinase 2 in

serum-dependent regulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis. J

Biol Chem. 280:36318–36325. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Yao Y, Teng S, Li N, Zhang Y, Boyden PA

and Pu J: Aminoglycoside antibiotics restore functional expression

of truncated HERG channels produced by nonsense mutations. Heart

Rhythm. 6:553–560. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wilde AA, Antzelevitch C, Borggrefe M,

Brugada J, Brugada R, Brugada P, Corrado D, Hauer RN, Kass RS,

Nademanee K, et al: Study Group on the Molecular Basis of

Arrhythmias of the European Society of Cardiology: Proposed

diagnostic criteria for the Brugada syndrome: consensus report.

Circulation. 106:2514–2519. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Borggrefe M,

Brugada J, Brugada R, Corrado D, Gussak I, LeMarec H, Nademanee K,

Perez Riera AR, et al: Brugada syndrome: report of the second

consensus conference: endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society and the

European Heart Rhythm Association. Circulation. 111:659–670. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shu J, Zhu T, Yang L, Cui C and Yan GX:

ST-segment elevation in the early repolarization syndrome,

idiopathic ventricular fibrillation, and the Brugada syndrome:

cellular and clinical linkage. J Electrocardiol. 38(Suppl 4):

S26–S32. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Di Grande A, Tabita V, Lizzio MM,

Giuffrida C, Bellanuova I, Lisi M, Le Moli C and Amico S: Early

repolarization syndrome and Brugada syndrome: is there any linkage?

Eur J Intern Med. 19:236–240. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hedley PL, Jørgensen P, Schlamowitz S,

Moolman-Smook J, Kanters JK, Corfield VA and Christiansen M: The

genetic basis of Brugada syndrome: a mutation update. Hum Mutat.

30:1256–1266. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Baroudi G, Pouliot V, Denjoy I, Guicheney

P, Shrier A and Chahine M: Novel mechanism for Brugada syndrome:

defective surface localization of an SCN5A mutant (R1432G). Circ

Res. 88:E78–E83. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Baroudi G, Acharfi S, Larouche C and

Chahine M: Expression and intracellular localization of an SCN5A

double mutant R1232W/T1620M implicated in Brugada syndrome. Circ

Res. 90:E11–E16. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Poelzing S, Forleo C, Samodell M, Dudash

L, Sorrentino S, Anaclerio M, Troccoli R, Iacoviello M, Romito R,

Guida P, et al: SCN5A polymorphism restores trafficking of a

Brugada syndrome mutation on a separate gene. Circulation.

114:368–376. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Gui J, Wang T, Trump D, Zimmer T and Lei

M: Mutation-specific effects of polymorphism H558R in SCN5A-related

sick sinus syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 21:564–573. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Niemi M, Arnold KA, Backman JT, Pasanen

MK, Gödtel-Armbrust U, Wojnowski L, Zanger UM, Neuvonen PJ,

Eichelbaum M, Kivistö KT and Lang T: Association of genetic

polymorphism in ABCC2 with hepatic multidrug resistance-associated

protein 2 expression and pravastatin pharmacokinetics.

Pharmacogenet Genomics. 16:801–808. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Kroetz DL and

Sadée W: Multidrug resistance polypeptide 1 (MDR1, ABCB1) variant

3435C>T affects mRNA stability. Pharmacogenet Genomics.

15:693–704. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Capon F, Allen MH, Ameen M, Burden AD,

Tillman D, Barker JN and Trembath RC: A synonymous SNP of the

corneodesmosin gene leads to increased mRNA stability and

demonstrates association with psoriasis across diverse ethnic

groups. Hum Mol Genet. 13:2361–2368. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yan GX and Antzelevitch C: Cellular basis

for the Brugada syndrome and other mechanisms of arrhythmogenesis

associated with ST-segment elevation. Circulation. 100:1660–1666.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Di Diego JM, Cordeiro JM, Goodrow RJ, Fish

JM, Zygmunt AC, Pérez GJ, Scornik FS and Antzelevitch C: Ionic and

cellular basis for the predominance of the Brugada syndrome

phenotype in males. Circulation. 106:2004–2011. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Rosati B, Pan Z, Lypen S, Wang HS, Cohen

I, Dixon JE and McKinnon D: Regulation of KChIP2 potassium channel

beta subunit gene expression underlies the gradient of transient

outward current in canine and human ventricle. J Physiol.

533:119–125. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Gaborit N, Varro A, Le Bouter S, Szuts V,

Escande D, Nattel S and Demolombe S: Gender-related differences in

ion-channel and transporter subunit expression in non-diseased

human hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 49:639–646. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|