Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)

infection-associated gastritis is one of the most common infectious

diseases worldwide. Epidemiological, pathophysiological and

histological evidence has demonstrated that H. pylori

infection-associated gastritis is a major cause of gastric cancer

(1–3). Although the mechanisms by which

H. pylori induces gastric lesions/malignancies have been

extensively investigated, the role of the H. pylori

infection-associated chronic inflammation microenvironment in this

process is poorly understood.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are multipotent stem

cells that have been found in several different tissues (4–6).

MSCs are able to migrate across tissues and differentiate into a

variety of cells, depending on the surrounding microenvironment

(7,8). In addition to normal tissues, MSCs

have been found in injured tissue sites, suggesting a potential for

the application of MSCs in regenerative medicine. MSC tropism for

inflammation and cancer sites has also been reported, which links

MSCs to the development of inflammation-associated cancer (9–14).

In addition, the H. pylori-induced epithelial response can

direct the homing of MSCs into the gastric mucosa (15,16). As a component of the chronic

gastritis microenvironment, MSCs play critical roles in gastric

carcinogenesis and progression; however, little is known about the

mechanisms by which MSCs participate in this process.

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), a cell

population that exists in human carcinomas, play a tumor-promoting

role (11,12). CAFs that express fibroblast

activation protein (FAP) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) create a

niche for cancer cells and promote cancer metastasis (17,18). As the main cellular component of

the tumor stroma, CAFs can also induce the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) of malignant cells and promote angiogenesis

(19). MSCs have been identified

as a major source for CAFs (18).

The transition of MSCs into CAFs contributes to tumor progression,

angiogenesis and metastasis (18). We have previously reported that

co-culture with conditioned medium (CM) and microvesicles (MVs)

from gastric cancer cells induces the differentiation of MSCs into

CAFs (20).

To further demonstrate the role of MSCs in H.

pylori-induced gastritis and gastric cancer, in this study, we

designed a human umbilical cord MSC (hucMSC)/H. pylori

co-culture model and evaluated the biological effects of the

infected hucMSCs on normal gastric epithelial cells. Our results

demonstrated that H. pylori infection induced the expression

of CAF markers and cytokines in the hucMSCs. The infected hucMSCs

promoted GES-1 normal gastric epithelial cells to acquire a

mesenchymal phenotype through the process of EMT. The infected

hucMSCs inhibited proliferation and promoted the invasion of GES-1

cells through a paracrine mechanism. Our findings may enhance the

understanding of the role of MSCs in H. pylori

infection-associated gastric cancer.

Materials and methods

HucMSCs isolation and cell culture

HucMSCs were obtained as previously described

(4). Fresh umbilical cords were

collected from informed, consenting mothers and processed within 6

h. The cords were rinsed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)

containing penicillin and streptomycin and the cord vessels were

removed. The washed cords were cut into sections of 1–3

mm2 in size and were allowed to float in DMEM containing

10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 1%

penicillin and streptomycin. The sections of the cords were

subsequently incubated at 37°C in humidified air with 5%

CO2 and the medium was changed every 3 days after the

initial plating. When well developed colonies of fibroblast-like

cells reached 80% confluence, the cultures were trypsinized and

passaged into new flasks for further expansion. The characteristics

of the isolated hucMSCs, including morphological appearance,

surface antigens, differentiation potential and gene expression

were investigated as previously described (4,21).

It was confirmed that hucMSCs were obtained and the MSCs at passage

3 were used for the experiments. All experimental protocols were

approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang,

China.

Cell culture, H. pylori strain and growth

conditions

Human immortalized GES-1 cells were purchased from

Cowin Biotech Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and maintained in

RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in

a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. The H. pylori

strain 11673 was kindly provided by Dr Shi-He Shao (Jiangsu

University). The H. pylori strain was grown in trypticase

soy agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood and incubated at 37°C

under a microaerophilic atmosphere. For the co-culture experiments,

the H. pylori strain was grown for 48 h, resuspended in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS and adjusted to OD600 nm = 1

[corresponding to 1×108 colony-forming units (CFU)/ml]

prior to infection.

Co-culture of hucMSCs with H. pylori

HucMSCs cells were trypsinized, resuspended in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS and seeded into culture flask. Twelve

hours after seeding, grown colonies of H. pylori (48 h) were

collected and the bacterial cells were added to the monolayer at a

multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100 bacteria/cell. Cultures were

maintained at 37°C under a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere

for 24 h. The culture supernatants were harvested, centrifuged for

5 min at 3,000 rpm, filtered through 0.45-μm filter units, and

stored at −80°C until use. The treated cells were harvested at the

indicated time and subjected to the following experiments. For the

controls, uninfected hucMSCs (hucMSCs) were processed in a similar

manner in the absence of bacteria. Three duplicate wells were

prepared for each experimental condition.

Exposure of GES-1 cells to CM from H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs

The GES-1 cells were harvested as described above

and cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and

antibiotics. The GES-1 cells were exposed to freshly harvested CM

from the uninfected hucMSCs or the H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs for 48 h. The control GES-1 cells were processed in a

similar manner in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. All

reactions were repeated 3 times independently to ensure the

reproducibility.

RNA extraction and quantitative reverse

transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen) and cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription

kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Toyobo, Osaka,

Japan). The primers used in this study were produced by Invitrogen

(Shanghai, China). qRT-PCR analysis was performed to detect the

changes in the expression of FAP, α-SMA, E-cadherin, N-cadherin and

vimentin genes (Rotor-Gene 6000 Real-Time PCR Machine; Corbett Life

Science, Sydney, Australia). An endogenous ‘housekeeping’ gene

(β-actin) was quantified to normalize the results. The primers used

in this study were as follows: FAP forward, 5′-ATA

GCAGTGGCTCCAGTCTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GATAA GCCGTGGTTCTGGTC-3′;

α-SMA forward, 5′-ATAGCAG TGGCTCCAGTCTC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GATAAGCCGTGG TTCTGGTC-3′; E-cadherin forward, 5′-CGCATTGCCACA

TACACTCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTGGCTGAGGATGGTGT AAG-3′; N-cadherin

forward, 5′-AGTCAACTGCAACCGT GTCT-3′ and reverse,

5′-AGCGTTCCTGTTCCACTCAT-3′; vimentin forward,

5′-GAGCTGCAGGAGCTGAATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGGTCAAGACGTGCCAGAG-3′;

and β-actin forward, 5′-CACGAAACTACCTTCAACTCC-3′ and reverse,

5′-CATACTCCTGCTTGCTGATC-3′. All experiments were performed in

triplicate.

Western blot analysis

The cells were collected and lysed in RIPA buffer

(10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM

NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mg/ml

aprotinin and 1 g/ml leupeptin) on ice. Aliquots containing

identical amounts of protein were fractionated by sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then

transferred onto methanol pre-activated polyvinylidene difluoride

(PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes

were blocked by 5% w/v non-fat dry milk. Following sequential

incubation with the primary and secondary antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., USA), the signal was visualized using HRP

substrate (Millipore) and analyzed using MD ImageQuant Software, as

perviously described (20). The

sources and dilution factors of the primary antibodies were as

follows: rabbit polyclonal anti-FAP (1:500; Abcam, USA),

anti-vimentin (1:2,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.),

anti-N-cadherin (1:400; SAB; Signalway Antibody Co., Ltd., MD,

USA), anti-E-cadherin (1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-α-SMA (1:400),

anti-BMI (1:400) (all from Bioworld Technology Inc., USA),

anti-SOX2 (1:500), anti-Nanog (1:500) (both from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-Oct4 (1:400), anti-p53 (1:800), anti-p21

(1:1,000; all SAB; Signalway Antibody Co., Ltd.) and anti-β-actin

(1:2,000; Bioworld Technology Inc.).

Luminex assay/ELISA

The concentrations of granulocyte-macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8,

platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), tumor necrosis factor

(TNF)-α, IL-10, IL-1β, epidermal growth factor (EGF), IL-15, IL-17,

IL-2, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and monocyte

chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in the supernatants of the

control (uninfected) and H. pylori-infected hucMSCs were

measured using Luminex (Millipore)/ELISA (Dakewe Biotech, Ltd.,

Beijing, China) kits in accordance with the manufacturer’s

instructions.

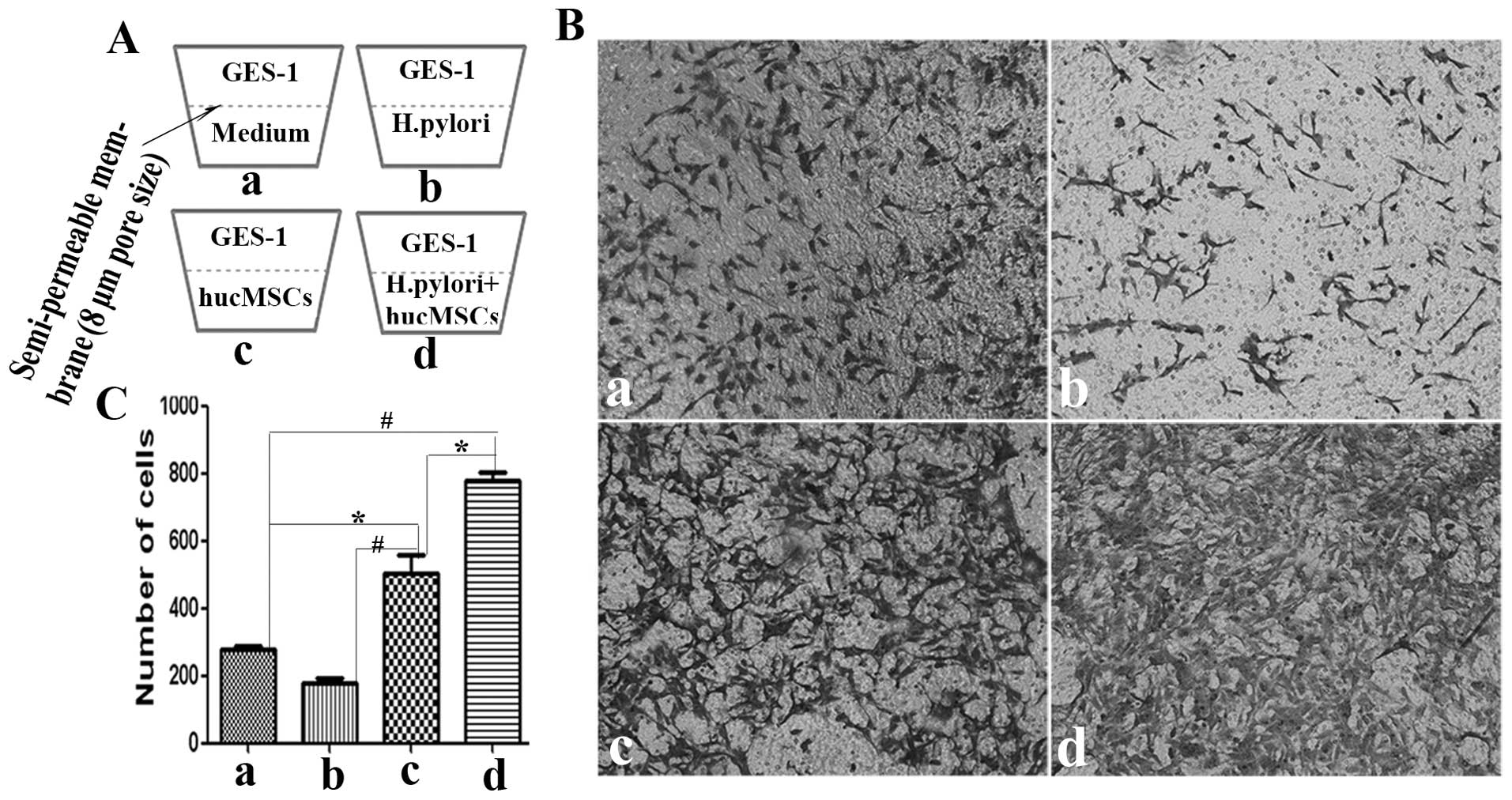

Transwell invasion assay

The invasion assay was carried out as previously

described (20). Briefly, GES-1

cells (5×104 cells/200 μl) suspended in serum-free

medium were loaded into the upper compartment of a Transwell

chamber and 600 μl of 10% FBS-DMEM medium containing hucMSCs

(5×104 cells/well) in the presence or absence of H.

pylori (MOI, 100:1) were added to the bottom well of the

Transwell chamber (Corning, Inc. Life Sciences, MA, USA). Following

culture at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 for

8 h, the cells in the upper membrane were wiped with a wet Q-tip.

The cells that had migrated through the membrane (8 μm pore size)

were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal

violet. The cells were observed under a microscope and at least 10

fields of cells were assayed for each group. Each assay was

repeated 3 times.

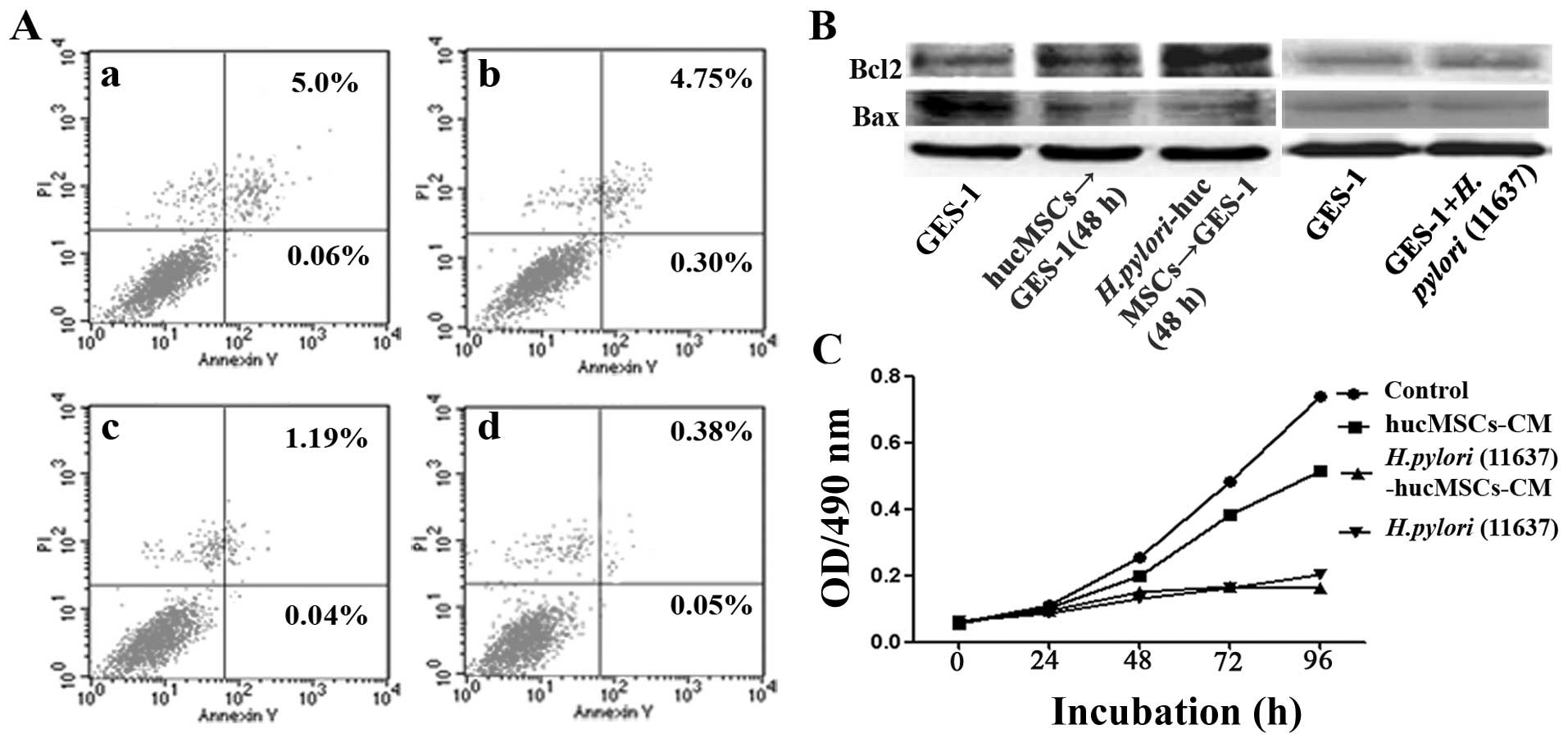

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was evaluated using the FITC-Annexin

V Apoptosis Detection kit I (BioVision Inc., San Francisco, CA,

USA). The GES-1 cells were harvested at 48 h after co-culture with

CM from the infected and uninfected hucMSCs. The fractions of

viable, necrotic and apoptotic cells were detected and quantified

by flow cytometry.

Cell proliferation assay

The GES-1 cells were plated in 96-well plates

(5×103 cells/well) and incubated at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 12 h. The cells were then

treated with CM from the infected and uninfected hucMSCs and

incubated for 4 days. At the indicated time points (0, 24, 48, 72

and 96 h), the absorbance of the samples was measured using a

VersaMax Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA,

USA) at wavelength of 450 nm. Each experiment was conducted in

triplicate and repeated twice independently.

Cell colony-forming assay

The GES-1 cells plated in 6-well plates

(1×103 cells/well) were incubated with DMEM (control),

or CM from the uninfected hucMSCs or the H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs for 48 h, and then all groups were incubated at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 for 15 days with

RPMI-1640 medium with 10% FBS (normal medium). The medium was

changed every 3 days. The number of colonies was then evaluated by

crystal violet staining. The results are the mean values of 3

experiments and 3 replicate plates.

Statistical analyses

All data are expressed as the means ± SD. SPSS

software was used to analyze the data. The means of different

treatment groups were compared by two-way ANOVA or the Student’s

t-test. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

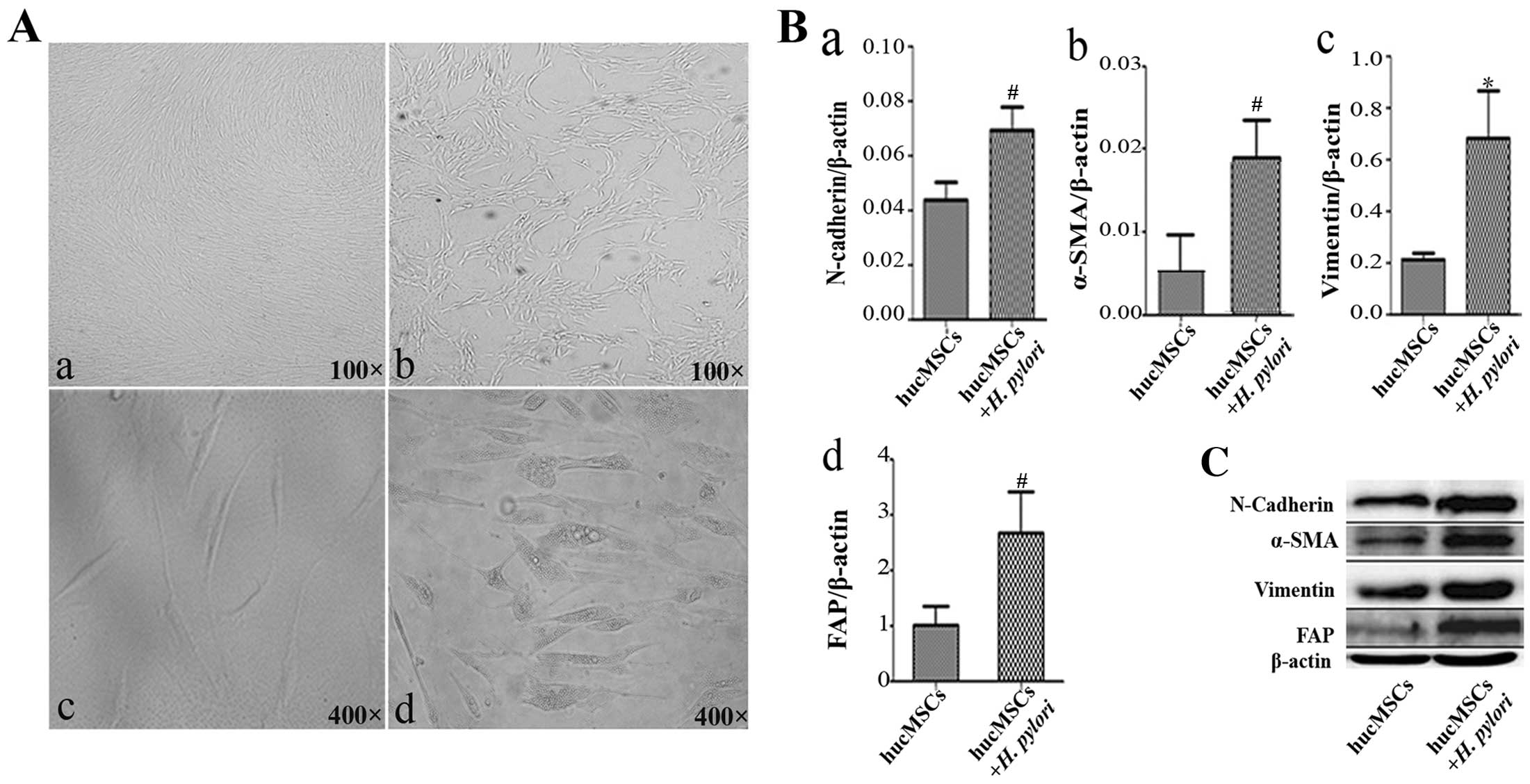

H. pylori infection promotes the

differentiation of hucMSCs into CAFs

To determine the effects of H. pylori

infection on the phenotype of hucMSCs, we infected the cells with

H. pylori at an MOI of 100:1. The hucMSCs acquired a

spindle-shaped morphology at 24 h after H. pylori infection

(Fig. 1A). An increased

expression of fibroblastic proteins (α-SMA, FAP, vimentin and

N-cadherin) has been defined as a marker for CAFs (17,18). Thus, we detected the expression of

CAF markers in the H. pylori-infected hucMSCs by qRT-PCR.

The results revealed that H. pylori infection increased the

expression of FAP, α-SMA, N-cadherin and vimentin genes in the

hucMSCs (Fig. 1B). In agreement

with the gene expression data, FAP, α-SMA, N-cadherin and vimentin

protein levels were also increased in the hucMSCs upon exposure to

H. pylori (Fig. 1C).

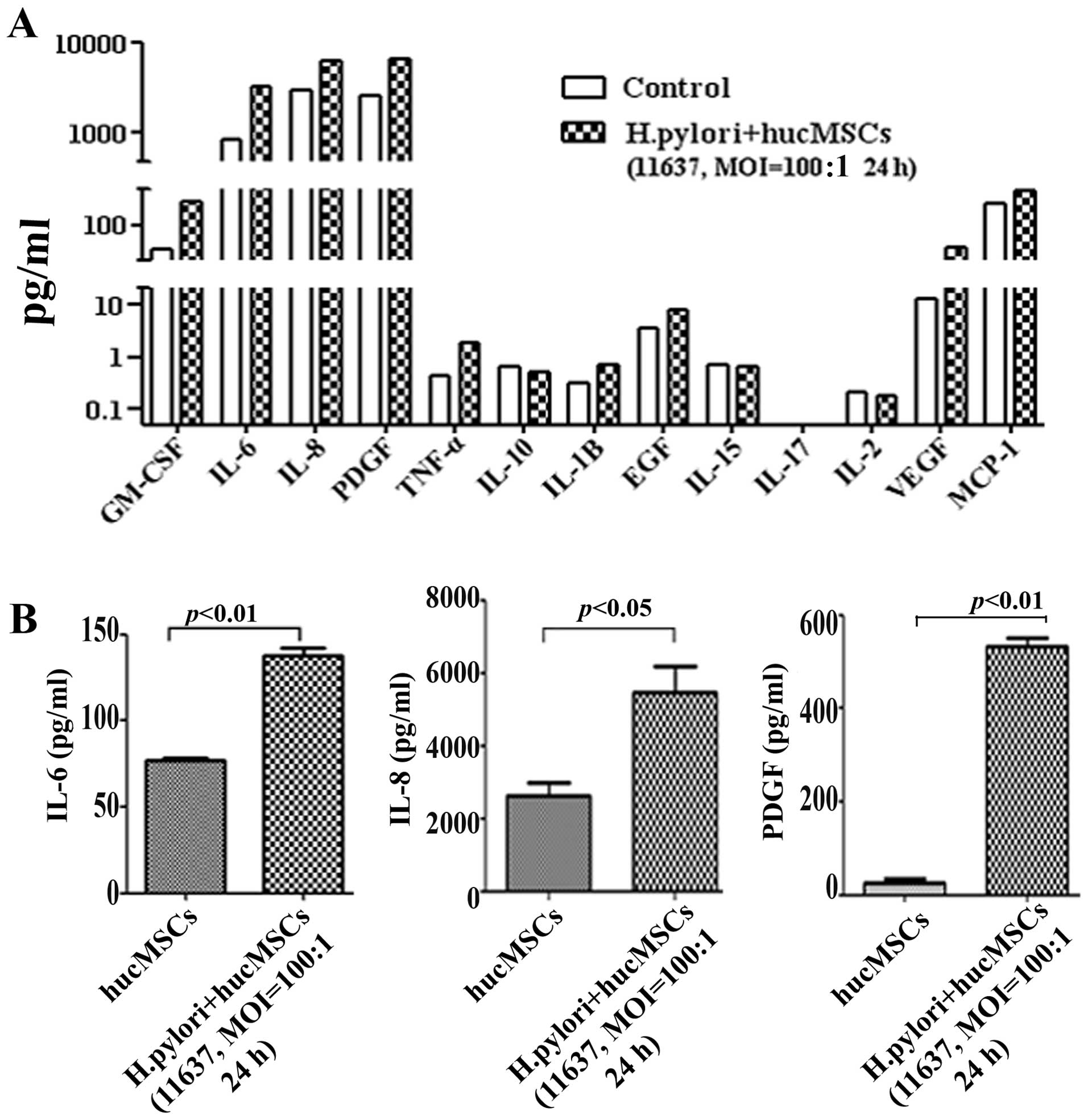

H. pylori infection induces the

production of CAF-associated factors in hucMSCs

The upregulation of specific factors (IL-6, IL-8,

VEGF and EGF) has been suggested as another marker for CAFs

(13,18,22). To that end, we detected

CAF-associated functional factors in H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs by Luminex assay. The results revealed that the expression

of several cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, IL-8 and PDGF

was markedly increased in the hucMSCs infected with H.

pylori (Fig. 2A). The

induction of IL-6, IL-8 and PDGF expression in the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs was further validated by ELISA

(Fig. 2B). These data indicate

that H. pylori infection induces the production of

CAF-associated functional factors in MSCs.

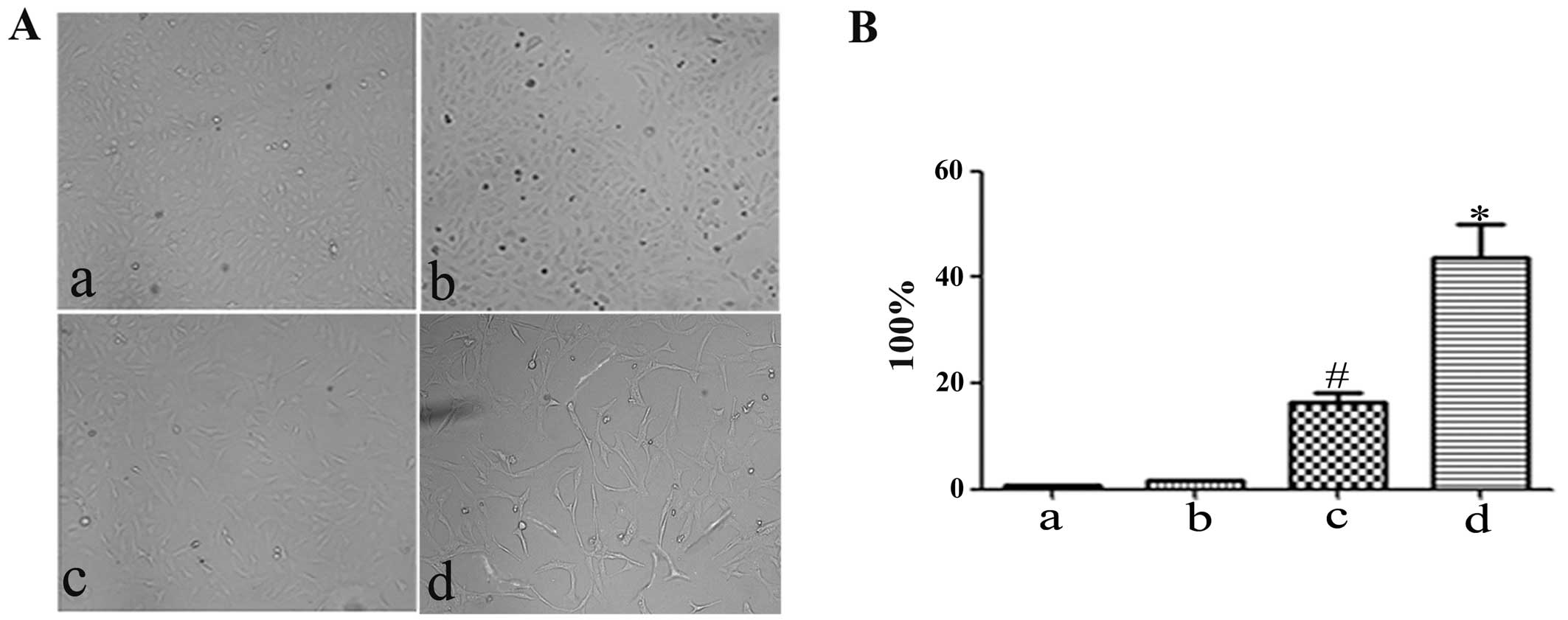

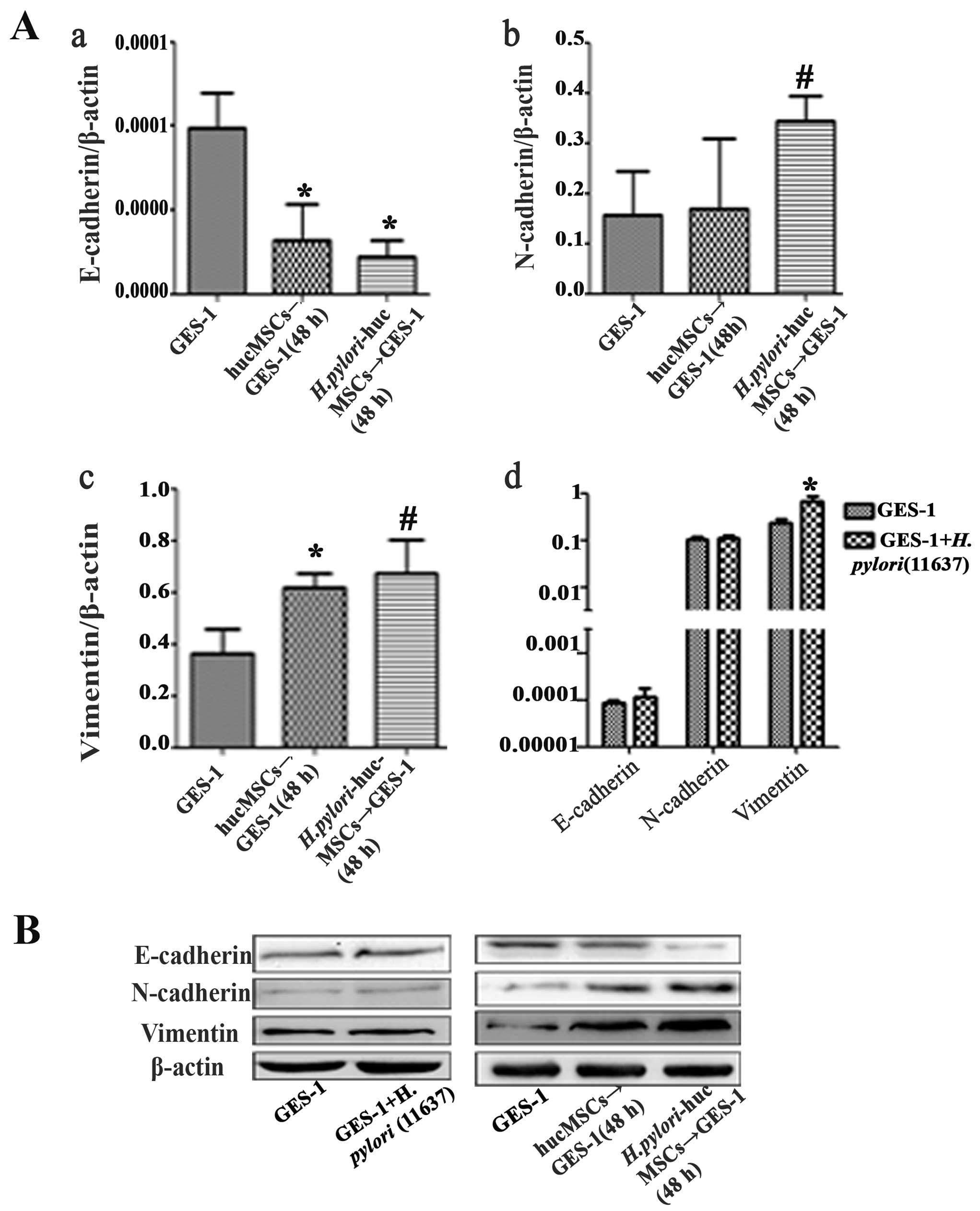

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs induce EMT in

GES-1 cells

To determine the effects of H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs on gastric epithelial cells, we

observed morphological changes in the control GES-1 cells, those

cultured with H. pylori (11637; MOI, 100:1), and those

cultured with uninfected and H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. The

morphological shift from an epithelial to a fibroblastic phenotype

was observed in the GES-1 cells treated with CM from both the

uninfected and H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. However, the

H. pylori infection of the hucMSCs significantly enhanced

their ability to induce the acquirement of a fibroblastic phenotype

in GES-1 cells (Fig. 3). We then

analyzed the expression of EMT markers, including E-cadherin,

N-cadherin and vimentin, in the GES-1 cells that were treated with

CM from the uninfected and H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. The

results revealed that GES-1 cells exhibited a mesenchymal phenotype

characterized by an impaired E-cadherin expression and an increased

expression of vimentin and N-cadherin (Fig. 4).

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs enhance the

invasive ability of GES-1 cells

EMT phenotypes are associated with an enhanced

invasive ability. To determine whether H. pylori infection

affects the pro-invasive capacity of the hucMSCs in GES-1 cells, an

in vitro Transwell cell migration assay was performed

(Fig. 5A). CM from the hucMSCs

induced the migration of GES-1 cells. Compared with the control

(control GES-1 cells) and hucMSC group, CM from the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs induced a more aggressive phenotype in

the GES-1 cells (Fig. 5B). The

number of migrated cells was then quantified (Fig. 5C).

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs reduce the

apoptosis of GES-1 cells

The GES-1 cells were treated with CM from the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs for 48 h, and cell apoptosis was

analyzed by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. The apoptotic rate

significantly decreased following exposure to CM from the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs (5.06 vs. 0.43%, p<0.05) (Fig. 6A). We also detected the expression

of apoptosis-related proteins in the GES-1 cells treated with CM

from the H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. We found that the

expression of Bax, a pro-apoptotic effector, decreased in the

treated GES-1 cells, whereas the expression of the anti-apoptotic

protein, Bcl-2, increased (Fig.

6B). These results indicated that the H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs inhibited apoptosis in gastric epithelial cells.

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs inhibit the

proliferation of GES-1 cells

The GES-1 cells were treated with CM from the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs for 4 days, and cell proliferation was

analyzed by MTT assay. The results revealed that CM obtained from

the infected hucMSCs significantly inhibited the proliferation of

GES-1 cells in vitro (Fig.

6C).

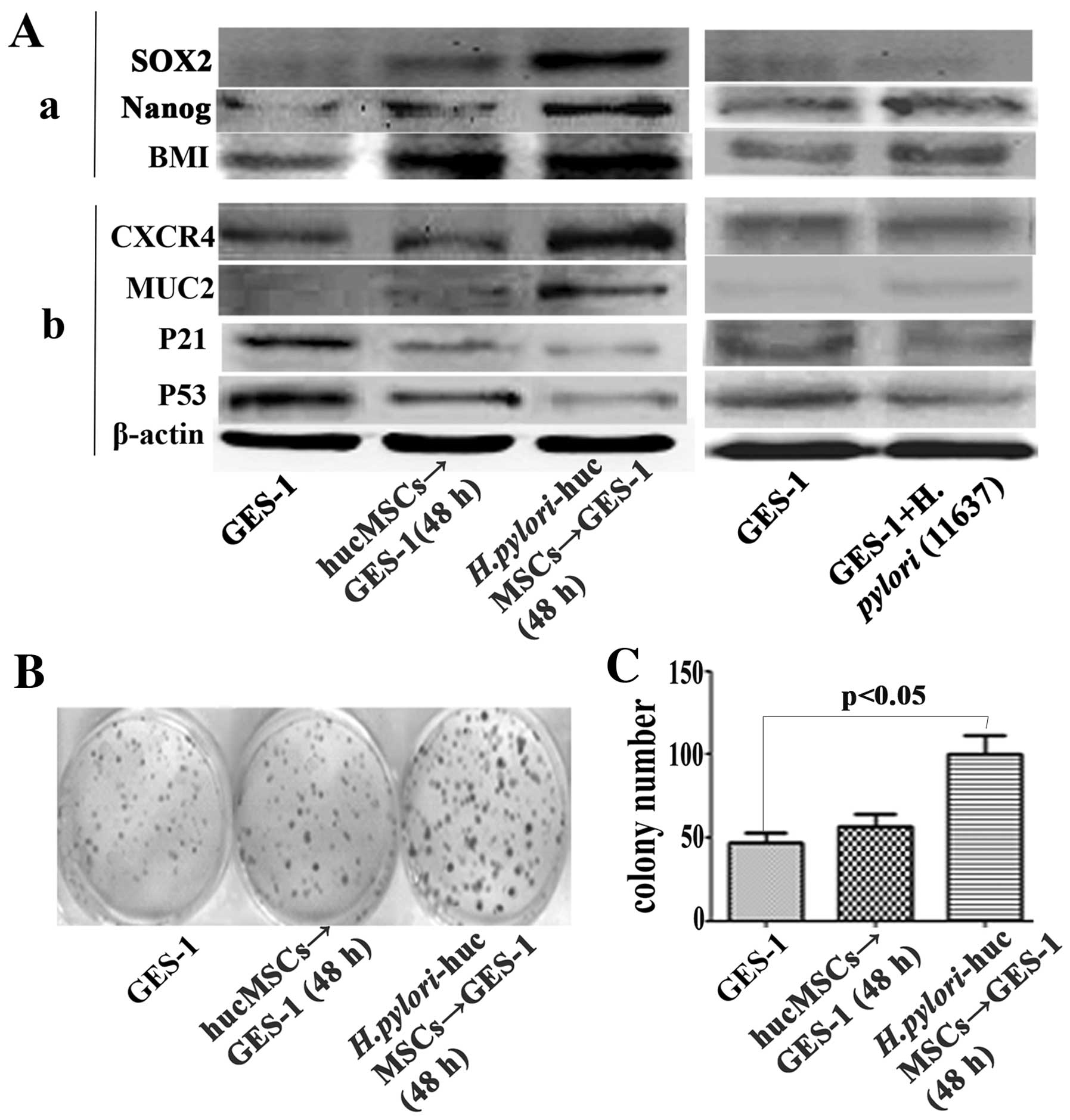

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs induce stem

cell properties in GES-1 cells

Several stem cell-related proteins, including SOX2,

Nanog and BMI were detected in the GES-1 cells treated with CM from

the H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. The H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs significantly upregulated the

expression of SOX2, Nanog and BMI-1 in the GES-1 cells (Fig. 7A-a).

Effect of H. pylori-infected hucMSCs on

the expression of oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins in

GES-1 cells

To determine whether H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs can induce the transformation of GES-1 cells, we analyzed

the expression of oncoproteins and tumor suppressor proteins in the

GES-1 cells. The GES-1 cells were treated with CM derived from the

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs for 48 h. The results revealed

that the H. pylori-infected hucMSCs increased the expression

of mucin 2 (MUC2) and chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4)

oncoproteins, and decreased the expression of the tumor suppressor

proteins, p53 and p21, in the GES-1 cells (Fig. 7A-b).

H. pylori-infected hucMSCs stimulate the

colony-forming ability of GES-1 cells

We further performed a cell colony-forming assay to

assess the oncogenic potential of GES-1 cells that were treated

with CM from the H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. Compared with

the control GES-1 cells and those treated with CM from the

uninfected hucMSCs, the cells treated with CM from the H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs showed a significantly enhanced

colony-forming ability (Fig. 7B and

C).

Discussion

CAFs that express FAP and α-SMA are key determinants

in the malignant progression of cancer growth, vascularization and

metastasis (11,17,18). After being passaged successively

10 times in vitro without ongoing interaction with carcinoma

cells, CAFs still retain their ability to promote tumor growth when

co-injected with carcinoma cells into immunodeficient mice

(11,12). MSCs have been shown to be involved

in H. pylori infection-associated gastric carcinogenesis

(15). However, the mechanisms

responsible for the promoting roles of MSCs in cancer initiation

and progression are not yet well understood. In this study, we

demonstrated that H. pylori infection induced typical CAF

differentiation with the increased expression of CAF markers and

cytokines in hucMSCs. Recent studies have demonstrated well-defined

roles for CAF-associated cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-8, PDGF, VEGF,

EGF and GM-CSF in tumorigenesis (18,22,23). The results presented in this study

suggest that H. pylori infection may induce the

differentiation of MSCs into CAFs and enhance the secretion of

multiple cytokines.

EMT is essential for the generation of new tissues

during embryogenesis and plays pivotal roles in inflammation and

wound healing (24,25). EMT is defined as a biological

process, in the course of which epithelial cell-cell adhesion is

decreased by the downregulation of adhesion molecules, such as

E-cadherin, and cell morphology becomes fibroblast-like with the

upregulation of vimentin and N-cadherin (24). In addition to a loss in epithelial

characteristics, EMT frequently coincides with the acquisition of

motility and invasiveness, as well as an increase in the resistance

to apoptosis and a markedly altered production of extracellular

matrix components. Cancer is often viewed as the corrupted form of

normal development (26–29). EMT has been implicated as a

fundamental step of carcinogenesis (30) and represents one of the steps

required for tumor progression through invasion and metastatic

spread (31). We hypothesized

that H. pylori-infected MSCs may promote gastric

lesions/malignancies under the conditions of chronic gastritis

through the induction of EMT in gastric epithelial cells. To prove

this hypothesis, we analyzed the phenotype of GES-1 cells

co-cultured with CM from H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. We

found that GES-1 cells exposed to CM from H. pylori-infected

hucMSCs not only displayed a morphological shift from an epithelial

to a fibroblastic phenotype, but also presented decreased

E-cadherin expression, increased vimentin and N-cadherin

expression, and an enhanced invasive ability in vitro. These

results are in agreement with data from previous studies,

demonstrating that the loss of E-cadherin expression augments

cellular dissemination and metastasis (32). These results support the

hypothesis that H. pylori infection-induced MSC transition

into CAFs results in gastric lesions/malignancies by promoting the

occurrence of EMT.

Tumor development involves multiple steps and

factors, including the activation of oncogenes, the inactivation of

tumor suppressor genes, and the aberrant expression of

apoptosis-related genes (33). In

this study, we demonstrated that the infected hucMSCs enhanced the

expression of the oncoproteins, MUC2 and CXCR4, whereas they

inhibited the expression of the tumor suppressor proteins, p53 and

p21, in GES-1 cells. We also demonstrated that the proliferation

rate of the GES-1 cells was reduced by CM from H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs. These results are consistent with

those of other studies, suggesting that the proliferation rate of

cancer cells decreases when the cells move and migrate (34,35). Evidence suggests that cancer cells

acquire stem cell-like properties through EMT (36). Mani et al (37) demonstrated an upregulation of stem

cell markers through the induction of EMT in mammary epithelial

cells and breast cancer cells. Additional studies have demonstrated

that the induction of EMT not only promotes tumor cell invasion and

metastasis, but also contributes to the acquisition of stem cell

properties (38). In this study,

we detected the expression of stem cell markers and evaluated the

capacity of gastric epithelial cells to form colonies. We

demonstrated that GES-1 cells expressed higher levels of the

stemness markers, Nanog, BMI and SOX2, following exposure to CM

from H. pylori-infected hucMSCs. Nanog, SOX2 and BMI have

been shown to be critical factors for cancer initiation and

progression (39–41). The upregulation of these

stemness-related factors indicated the acquirement of stem cell

properties in the GES-1 cells following exposure to CM from H.

pylori-infected hucMSCs. In addition, the H.

pylori-infected MSCs markedly enhanced the colony-forming

ability of gastric epithelial cells, suggesting that incubation

with CM from H. pylori-infected MSCs endows gastric

epithelial cells with both oncogenic potential and self-renewal

ability. However, the specific factors that mediate this process

and the signaling pathways involved remain to be identified.

Taken together, we demonstrate that H. pylori

infection induces the differentiation of MSCs into CAF-like cells

and that incubation with CM from H. pylori-infected MSCs

destroys cell junctions, promotes cell invasion and enhances the

colony-forming ability of gastric epithelial cells though the

induction of EMT. Our findings suggest that H. pylori

infection causes gastric lesions/malignancies by converting MSCs

into CAFs, creating a unique microenvironment for the malignant

transformation of the normal gastric epithelium. This study may aid

in the understanding of the role and mechanisms of action of MSCs

in the initiation and progression of H. pylori-associated

gastric cancer.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Major Research Plan

of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

91129718), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant

nos. 81071421, 81302119, 81000181 and 81201660), the Jiangsu

Province Project of Scientific and Technological Innovation and

Achievements Transformation (grant no. BL2012055), the Jiangsu

Province Outstanding Medical Academic Leader and Sci-tech

Innovation Team Program (grant no. LJ201117), the Doctoral Program

Foundation of State Education Ministry (grant no. 20113227110011),

the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (grant no.

BK20130540) and the Jiangsu Province Department of Education

Science Research Foundation (grant no. 13KJB320001).

References

|

1

|

Machado AM, Figueiredo C, Touati E, et al:

Helicobacter pylori infection induces genetic instability of

nuclear and mitochondrial DNA in gastric cells. Clin Cancer Res.

15:2995–3002. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Milne AN, Carneito F, O’Morain C and

Offerhaus GJ: Nature meets nurture: molecular genetics of gastric

cancer. Hum Genet. 126:615–628. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chan AO, Chu KM, Huang C, et al:

Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and

interleukin 1beta polymorphism predispose to CpG island methylation

in gastric cancer. Gut. 56:595–597. 2007.

|

|

4

|

Qiao C, Xu W, Zhu W, et al: Human

mesenchymal stem cells isolated from the umbilical cord. Cell Biol

Int. 32:8–15. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cao H, Xu W, Qian H, et al: Mesenchymal

stem cell-like cells derived from human gastric cancer tissues.

Cancer Lett. 274:61–71. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Schäffler A and Büchler C: Concise review:

adipose tissue-derived stromal cells - basic and clinical

implications for novel cell-based therapies. Stem Cells.

25:818–827. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Charbord P: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem

cells: historical overview and concepts. Hum Gene Ther.

21:1045–1056. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Phinney DG and Prockop DJ: Concise review:

mesenchymal stem/multipotent stromal cells: the state of

transdifferentiation and modes of tissues repair - current views.

Stem Cells. 25:2896–2902. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sasaki M, Abe R, Fujita Y, Ando S, Inokuma

D and Shimizu H: Mesenchymal stem cells are recruited into wounded

skin and contribute to wound repair by transdifferentiation into

multiple skin cell type. J Immunol. 180:2581–2587. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Spaeth E, Kloop A, Dembinski J, Andreeff M

and Marini F: Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: defining

the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther.

15:730–738. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Orimo A and Weinberg RA: Stromal

fibroblasts in cancer: a novel tumor-promoting cell type. Cell

Cycle. 5:1597–1601. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sqroi DC, et al:

Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas

promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12

secretion. Cell. 121:335–348. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Glaire MA, EI-Omar EM, Wang TC and

Worthley DL: The mesenchyme in malignancy: a partner in the

initiation, progression and dissemination of cancer. Pharmacol

Ther. 136:131–141. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B and

Middleton J: Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their

phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and

potential for homing. Stem Cells. 25:2739–2749. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S, et al:

Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science.

306:1568–1571. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ferrand J, Lehours P, Schmid-Alliana A,

Mégraud F and Varon C: Helicobacter pylori infection of

gastrointestinal epithelial cells in vitro induces mesenchymal stem

cell migration through an NF-κB-dependent pathway. PLoS One.

6:e290072011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dudás J, Fullár A, Bitsche M, et al:

Tumor-produced, active interleukin-1β regulates gene expression in

carcinoma-associated fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 317:2222–2229.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Spaeth EL, Dembinski JL, Sasser AK, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cell transition to tumor-associated fibroblasts

contributes to fibrovascular network expansion and tumor

progression. PLoS One. 4:e49922009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Giannoni E, Bianchini F, Masieri L, Serni

S, Torre E, Calorini L and Chiarugi P: Reciprocal activation of

prostate cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts stimulates

epithelial- mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness. Cancer Res.

70:6945–6956. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Gu J, Qian H, Shen L, et al: Gastric

cancer exosomes trigger differentiation of umbilical cord derived

mesenchymal stem cells to carcinoma-associated fibroblasts through

TGF-β/Smad pathway. PLoS One. 7:e524652012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Qian H, Yang H, Xu W, et al: Bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate rat acute renal failure by

differentiation into renal tubular epithelial-like cells. Int J Mol

Med. 22:325–332. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Räsänen K and Vaheri A: Activation of

fibroblasts in cancer stroma. Exp Cell Res. 316:2713–2722.

2010.

|

|

23

|

Augsten M, Hägglöf C, Olsson E, et al:

CXCL14 is an autocrine growth factor for fibroblasts and acts as a

multi-modal stimulator of prostate tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 106:3414–3419. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Thiery JP: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transitions in development and pathologies. Curr Opin Celll Biol.

15:740–746. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Allan GJ, Beattie J and Flint DJ:

Epithelial injury induces an innate repair mechanism linked to

cellular senescence and fibrosis involving IGF-binding protein-5. J

Endocrinol. 199:155–164. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kalluri R and Weinberg RA: The basics of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 119:1420–1428.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Massagué J: TGFbeta in cancer. Cell.

134:215–230. 2008.

|

|

28

|

Padua D and Massagué J: Roles of TGFbeta

in metastasis. Cell Res. 19:89–102. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Buijs JT, Henriquez NV, van Overveld PG,

van der Horst G, ten Dijke P and van der Pluijm G: TGF-beta and

BMP7 interactions in tumour progression and bone metastasis. Clin

Exp Metastasis. 24:609–617. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yang J and Weinberg RA:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: at the crossroads of development

and tumor metastasis. Dev Cell. 14:818–829. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Christiansen JJ and Rajasekaran AK:

Reassessing epithelial to mesenchymal transition as a prerequisite

for carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Cancer Res. 66:8319–8326.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Tsukamoto H, Shibata K, Kajiyama H,

Terauchi M, Nawa A and Kikkawa F: Irradiation-induced

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) related to invasive

potential in endometrial carcinoma cells. Gynecol Oncol.

107:500–504. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

SI PH and HU QG: Progress of RNA interfere

in gene therapy for oral tumor. Int J Stomatol. 134:281–283.

2007.

|

|

34

|

Berdiel-Acer M, Bohem ME, López-Doriga A,

et al: Hepatic carcinoma-associated fibroblasts promote an

adaptative response in colorectal cancer cells that inhibit

proliferation and apoptosis: nonresistant cells die by nonapoptotic

cell death. Neoplasia. 13:931–946. 2011.

|

|

35

|

Vega S, Morales AV, Ocaña OH, Valdés F,

Fabregat I and Nieto MA: Snail blocks the cell cycle and confers

resistance to cell death. Genes Dev. 18:1131–1143. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Morel AP, Lièvre M, Thomas C, Hinkal G,

Ansieau S and Puisieux A: Generation of breast cancer stem cells

through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 3:e28882008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Thiery JP, Aclogue H, Huang RY and Nieto

MA: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease.

Cell. 139:871–890. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Jeter CR, Badeaux M, Choy G, et al:

Functional evidence that the self-renewal gene NANOG regulates

human tumor development. Stem Cells. 27:993–1005. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lu Y, Futtner C, Rock JR, Xu X, Whitworth

W, Hogan BL and Onaitis MW: Evidence that SOX2 overexpression is

oncogenic in the lung. PLoS One. 5:el110222010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Qiao B, Chen Z, Hu F, Tao Q and Lam AK:

BMI-1 activation is crucial in hTERT-induced epithelial-mesenchymal

transition of oral epithelial cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 95:57–61.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|