Introduction

Microglia are the resident innate immune cells of

the central nervous system (CNS) that regulate neuroinflammation

(1). Activated microglia execute

host defense and repair injured tissue in the CNS, but they also

contribute to the expansion of inflammation in the CNS by means of

antigen presentation and release of inflammation-related mediators

such as cytokines, chemokines, and nitric oxide (2–4).

For example, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which is expressed in

microglia through its ligation with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), has

been reported to be involved in microglial activation and cause

neuronal injury due to the production and release of

inflammation-related mediators (5). However, much remains elusive with

regard to how the immunoregulatory molecules controlling microglial

function are involved in neuroinflammation.

The roles that semaphorins and their receptors,

plexins, play in the CNS have been previously investigated.

Semaphorins and plexins comprise two large families of molecules

that transmit signals crucial for the control of neuronal axon

guidance, cell migration, cell morphology, and cell-to-cell

interactions (6). The various

functions of semaphorins and plexins have also been exemplified in

the development of blood vessels and heart (7,8)

and in tumorigenesis (9).

Previous investigations have demonstrated a role for these

molecules in the immune system (10). For example, Plexin-C1 expressed in

dendritic cells moderately affect T-cell activation(11). Plexin-D1, which is highly

expressed in double-positive thymocytes, regulates the intrathymic

migration of immature thymocytes from the thymic cortex to medulla

(12), and Plexin-A4 is a

negative regulator in T-cell activation (13). Other studies have revealed the

diverse functions of plexins in the immune system. Plexin-A1

expressed in dendritic cells regulates the interaction between

dendritic cells and T cells to control adaptive immunity (14,15). Plexin-B1 expressed in microglia

and Plexin-A4 in macrophages exhibit a crucial role in promoting

the activation of these innate immune cells through the enhancement

of intracellular signals initiated by inflammatory stimuli. For

example, macrophages in Plexin-A4-deficient mice show the

significant attenuation of LPS-induced cytokine production

(16). Administration of a ligand

of Plexin-A4, Semaphorin 3A (Sema3A), to cultured peritoneal

macrophages enhances LPS-induced cytokine production in a

Plexin-A4-dependent manner (16).

Sema4D enhances the CD40-mediated activation of microglia through

Plexin-B1 (17).

In a previous study, we showed that

Plexin-A1-deficient microglial cells are significantly resistant to

LPS-induced inflammation and that Plexin-A1-mediated signaling

increased microglial NO production through crosstalk with the

LPS-stimulated TLR4 pathway (18). However, the role that

Plexin-A1-mediated signaling plays in the expression of other

LPS-induced inflammatory mediators in microglia has not been

clarified. Similarly, the intracellular signal transduction pathway

of Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling, which is involved in the increase of

LPS-induced microglial NO production remains to be clarified.

Against this background, using a BV-2 microglial

cell line, the aim of this study was to examine the intracellular

signal transduction pathway of Sema3A-Plexin-A1-mediated signaling,

which is involved in LPS-stimulated microglial activation.

Additionally, we aimed to demonstrate the necessity of Plexin-A1

for the optimal production of inflammatory mediators following

stimulation of the TLR4 pathway in BV-2 cells. In this study, the

targeted silencing of Plexin-A1 in BV2 cells resulted in the

significantly decreased activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and

of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) in the LPS

response. Sema3A serves as a ligand for Plexin-A1 in BV-2 cells and

enhances LPS-induced NO production in the cell line through ERK

activation in a Plexin-A1-dependent manner. Taking these findings

together, we propose the functional role of Plexin-A1 as a

regulator of the TLR4 pathway in microglia.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and transfection

BV-2 murine microglial cells immortalized by

infection with v-raf/c-myc recombinant retrovirus (19) were kindly provided by Dr N. Kaneda

(Faculty of Pharmacy, Meijo University) with permission to use the

cell line from Dr E. Blasi (Department of Diagnostics, Clinical and

Public Health Medicine, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia,

Modena, Italy). In brief, BV2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s

modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Wako, Osaka, Japan) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Equitech Bio, Inc., Kerrville,

TX, USA), penicillin (20 U/ml), and streptomycin (20 μg/ml,

Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). For transfection with small

interfering RNA (siRNA), BV-2 cells were seeded in 6-well plates

for western blotting, 24-well plates for reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and quantitative

RT-PCR, and 96-well plates for the Griess reaction and

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay at cell densities of 1×105, 2×104, and

0.3×104, respectively. Plated cells were grown in DMEM

with 10% FBS overnight, and were then transfected with

siRNA-Plexin-A1 (MS0178728; Takara Bio Inc., Shiga, Japan) and

siRNA-control (SNC01; Takara Bio Inc.) using the Lipofectamine

RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

48 h prior to treatment with reagents such as LPS and Sema3A,

according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Mice

Plexin-A1-deficient mice were produced by the

gene-targeting method with E14.1 embryonic stem (ES) cells

(15). The gene-targeting vector

was designed to replace the exon covering the initiation codon with

a neomycin-resistance gene and then transfected into ES cells by

electroporation. G418 and ganciclovir-resistant clones were

screened by PCR and confirmed by Southern blotting. Mutant ES cells

were introduced into mouse blastocysts, then transferred into

pseudopregnant mice to generate chimeras. Chimeras were bred with

Balb/c mice to transmit the mutant allele to the germline. Pairs of

resultant heterozygous mice were bred to gain homozygous knockout

mice, which were backcrossed with Balb/c mice. This study used F10

generation knockout mice, with their wild-type littermates as

controls. Mice were housed in the animal facilities of Wakayama

Medical University and the animal center of the Faculty of

Pharmacy, Meijo University. The care and use of mice and other

experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the

guidelines of the Physiological Society of Japan as well as the

guidelines on animal experimentation of both Wakayama Medical

University and Meijo University. The Animal Ethics Review Committee

of both institutions approved the experimental protocol.

Genotype analysis

Genotyping was performed by PCR with mouse tail DNA

as the template and a Plexin-A1 gene-specific primer set as

previously reported (15).

RT-PCR analysis for Plexin-A1 and

Neuropilin-1 gene transcripts

RNA was extracted from primary microglia, the BV-2

microglial cell line, or murine hippocampus by the SV Total RNA

Isolation System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Reverse transcription

of RNA was performed with SuperScript III reverse transcriptase and

random primers (Life Technologies). All the samples were normalized

with β-actin amplification for semiquantification. The following

oligonucleotides were used for PCR amplification: Plexin-A1,

forward: 5′-GTGTGTGGATAGC CATCA-3′ and reverse:

5′-CCAGCCTCTCGAACACT-3′; Neuropilin-1, forward:

5′-GGCCTCCTGCGATTCGTTACTGC T-3′ and reverse:

5′-CTTAGCCTTGCGCTTGCTGTCATC-3′; and Sema3A, forward:

5′-ATTGAATTCAACTATGCAAACGG AAAGAA-3′ and reverse:

5′-TAAGCGGCCGCGACACTTCTG GGTGCCCGCT-3′. Control primers used were:

β-actin, forward: 5′-GGGACGACATGGAGAAGATC-3′ and reverse: 5′-AGG

TCTTTACGGATGTCAACG-3′. All the primers were annealed at 63°C, and

35 cycles of amplification were performed.

Western blotting

For western blotting, tissue extracts were prepared

by homogenizing murine hippocampal tissue in T-PER Tissue Protein

Extraction Reagent (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA)

containing the protease inhibitor, α-complete (Roche Applied

Science, Penzberg, Germany). Fifteen micrograms of each sample were

adjusted to give a final solution of 60 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 2%

SDS, 10% glycerol, 0.1% bromophenol blue, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol.

The solution was heated at 95°C for 5 min, electrophoresed through

a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to polyvinylidine

difluoride membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Buckinghamshire,

UK). Plexin-A1, Neuropilin-1, TLR4, iNOS, p-NF-κB, NF-κB, p-IκB-α,

IκB-α, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, and β-actin were detected with their

respective antibodies using an enhanced chemiluminescence western

blot detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in accordance

with the manufacturer’s instructions. Antibodies used were

anti-Plexin-A1 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA),

anti-Neuropilin1 antibody (Abcam), anti-TLR4 antibody (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), anti-iNOS antibody (Merck

Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), anti-p-NF-κB antibody (Cell

Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), anti-NF-κB antibody (Cell

Signaling Technology), anti-p-IκB-α antibody (Cell Signaling

Technology), anti-IκB-α antibody (Cell Signaling Technology),

anti-p-ERK1/2 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ERK1/2

antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Sema3A antibody (Abcam),

and anti-β-actin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology).

NO assay and cell viability assay

To investigate the effect of Sema3A on NO production

in the BV-2 microglial cell line, the nitrite content was measured

with Griess reagent [1% sulfanilamide/0.1%

N-(1-naphthyl)-ethylenediamine dihydrochloride in 5% phosphoric

acid] according to the manufacturer’s instructions. BV-2 microglial

cells were plated at 0.3×104 cells/well in a 96-well

plate and cultured overnight in a CO2 incubator at 37°C,

combined with control siRNA or Plexin-A1-specific siRNA, and

incubated for two additional days. Eighteen hours after stimulation

of BV-2 cells with LPS and Sema3A or control IgG, 50 μl of the

culture supernatant were mixed with 50 μl of Griess reagent and

incubated for 15 min. Absorbance values were measured at 540 nm in

a plate reader (Bio-Rad, Gladesville, NSW, Australia), with fresh

DMEM as a blank in all the experiments. NO concentration was

calculated with reference to the nitrite standard curve. To analyze

cell viability of the BV-2 cells subjected to NO assay, 5 μl of MTT

(5 mg/ml; Sigma, Tokyo, Japan) were added to the BV-2 cells and

incubated at 37°C for 4 h. After the medium was removed, formazan,

a product of the MTT tetrazolium ring that was precipitated by the

action of mitochondrial dehydrogenases, was dissolved with 0.1 N

HCl in anhydrous isopropanol containing 10% Triton X-100 and

quantified spectrophotometrically at 595 nm for measurement of cell

viability.

Quantitative RT-PCR for analysis of

inflammatory gene transcripts

RNA was isolated from BV-2 microglial cells cultured

on a 24-well plate using the SV Total RNA Isolation System

(Promega). Quantitative RT-PCR with SYBR-Green (Qiagen, Tokyo,

Japan) was performed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied

Biosystems, Tokyo, Japan). Amplification of Rn18s was performed for

sample normalization. For the detection and quantification of

Rn18s, TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS transcripts, quantitative RT-PCR was

performed using QuantiTect Primer Assays following the

manufacturer’s protocol (Mm_Rn18s_2_SG QT01036875Mm_Tnf_1_SG

QT00104006, Mm_Il1b_2_SG QT01048355, and Mm_iNOS_1_SG QT00100275,

respectively; Qiagen).

Reagents for cell cultures

LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5),

Griess reagent, and MTT were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Recombinant Sema3A, which consists of the extracellular region of

Sema3A and the Fc portion of murine IgG2A (Sema3A-Fc) and murine

IgG2A, was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 was purchased from Cell Signaling

Technology.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as the means ± standard error of

mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed with the Student’s

t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by post-hoc

analysis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Plexin-A1 is expressed by BV-2 cells

In a previous study, we found that murine primary

microglia expressed Plexin-A1 (18). In the present study, the

expression of Plexin-A1 in the BV-2 mouse microglial cell line was

confirmed by RT-PCR analysis and western blotting (Fig. 1).

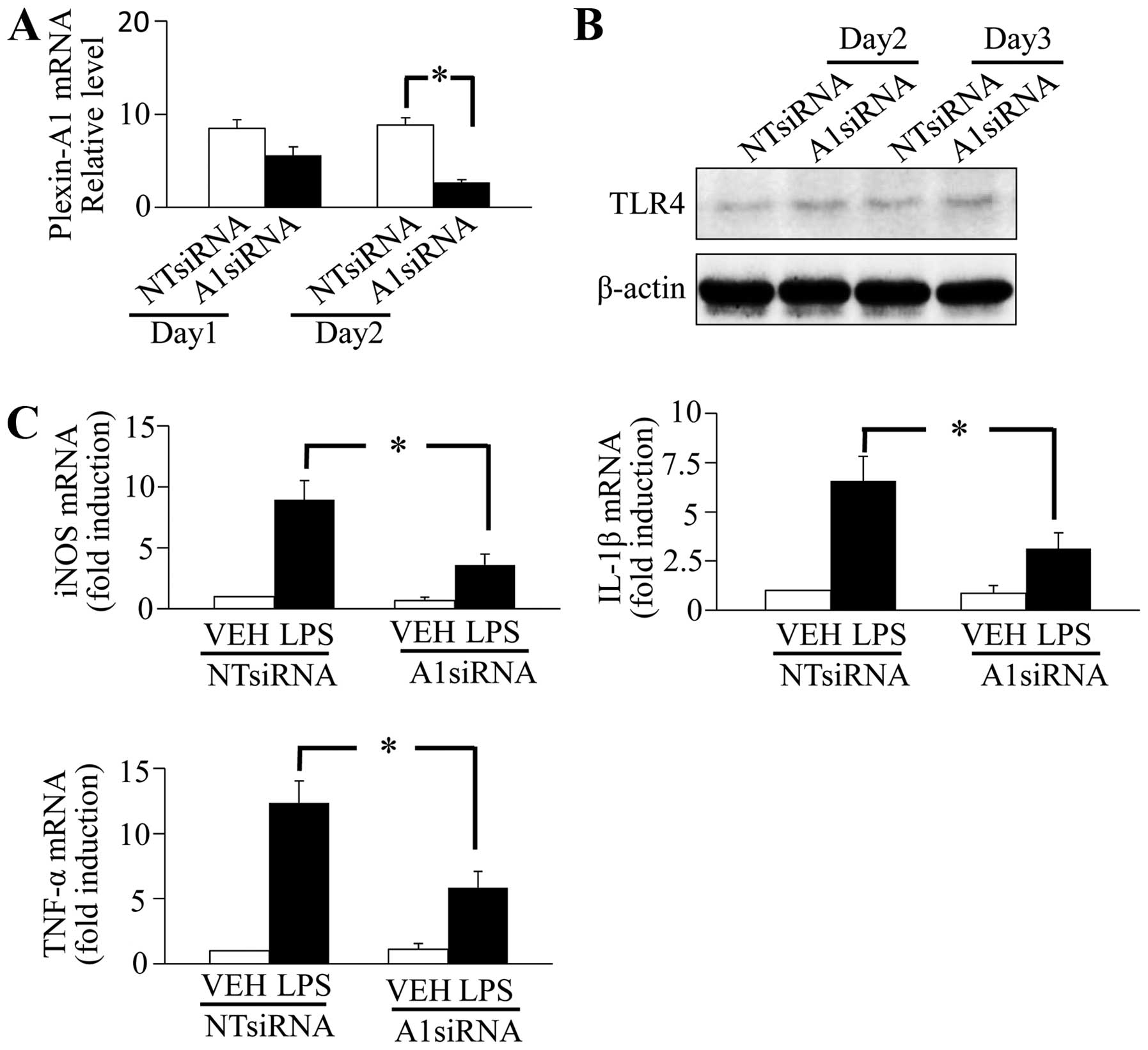

Plexin-A1 is required for iNOS, IL-1β and

TNF-α expression in BV-2 cells

As in primary microglia, LPS stimulation induces an

increased expression of inflammatory mediators such as iNOS, IL-1β,

and TNF-α in BV-2 cells (20–22). Although we previously demonstrated

that Plexin-A1 is involved in LPS-induced NO production in primary

microglia (unpublished data), the involvement of Plexin-A1 in the

expression of other TLR4-induced inflammatory mediators has yet to

be adequately examined. In the present study, we examined the role

of Plexin-A1 in inflammatory factor production in response to TLR4

activation in BV-2 cells. After BV-2 cells were treated with

Plexin-A1-specific siRNA and cultivated for 1 or 2 days, the

knockdown efficiency of Plexin-A1 was confirmed using quantitative

RT-PCR, and a significant decrease of Plexin-A1 mRNA was observed

in the BV-2 cells that were cultured for 2 days after siRNA

treatment (Fig. 2A). To examine

the effect of Plexin-A1 on TLR4 expression, TLR4 expression level

was assessed using western blotting in Plexin-A1 knockdown cells;

however, no significant change was observed (Fig. 2B). To examine the role of

Plexin-A1 in the LPS-TLR4 signaling pathway in BV-2 cells, the

expression levels of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α were assessed with

quantitative RT-PCR in Plexin-A1 knockdown cells treated with

vehicle or LPS. During TLR4 stimulation with LPS, a significantly

lower amount of iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA was generated in BV-2

cells with Plexin-A1 knockdown than BV-2 cells treated with control

non-target (NT) siRNA (Fig. 2C).

These findings showed that Plexin-A1 is required for the

TLR4-mediated generation of proinflammatory factors in BV-2 cells.

Assessment of LPS-induced iNOS protein expression using western

blotting showed a significantly lower level of iNOS protein

expression in BV-2 cells with targeted silencing of Plexin-A1 than

in control siRNA-treated BV-2 cells (Fig. 3A and B). Assessment of LPS-induced

NO production by the Griess reaction revealed a significant

decrease in NO in Plexin-A1-specific siRNA-treated BV-2 cells

compared with control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3C). MTT assay showed no significant

differences in cell viability among any BV-2 cell treatments

(Fig. 3D).

Plexin-A1 mediates the activation of

NF-κB and ERK

During the microglial response to TLR agonists and

microbial pathogens, NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK) signaling pathways are known to regulate the production of

inflammatory mediators (23–26). Since the generation of iNOS,

IL-1β, and TNF-α was decreased by Plexin-A1 knockdown (Figs. 2C and 3), we investigated the role of Plexin-A1

in these signaling pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. In a previous

study, we reported that Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling increased NO

production through crosstalk with the TLR4 pathway in primary

microglia (18). Sema4D-Plexin-B1

signaling also increased NO production through ERK1/2 activation,

which is dependent on inflammatory stimulation in primary microglia

(17). Activation of ERK1/2 also

plays a crucial role in the induction of iNOS expression in

TLR4-stimulated microglia (27).

In neuronal cells, Plexin-A1 is involved in the determination of

the direction of axonal extension and the induction of growth cone

collapse in an ERK1/2 activation-dependent manner through crosstalk

with Plexin-B1 (28–32). Plexin-A1-mediated signaling in

microglia may therefore be involved in the production of

inflammatory factors through ERK1/2 activation by cooperating with

the TLR4 pathway. Accordingly, to examine whether Plexin-A1 is

involved in the activation of NF-κB and ERK1/2 in LPS-stimulated

microglia, the phosphorylation state of these proteins was assessed

in vehicle- or LPS-treated BV-2 cells with either control siRNA or

Plexin-A1-specific siRNA. Control NT siRNA-treated BV-2 cells

exhibited enhanced phosphorylation of NF-κB, IκB-α, and ERK1/2

after LPS stimulation. In contrast, BV-2 cells with targeted

knockdown of Plexin-A1 exhibited a significant decrease in NF-κB

and IκB-α phosphorylation compared with cells treated with control

siRNA (Fig. 4). LPS stimulation

induced a significant increase of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in control

siRNA-treated BV-2 cells, but not in Plexin-A1-specific

siRNA-treated BV-2 cells (Fig.

4). These findings indicate that Plexin-A1 deficiency leads to

a significant defect in NF-κB and ERK1/2 activation in

TLR4-mediated signaling in BV-2 microglial cells.

Sema3A enhances LPS-induced nitrite

production through ERK activation in a Plexin-A1-dependent

manner

Since Plexin-A1 knockdown suppressed the expression

of LPS-induced inflammatory mediators, the BV-2 cell itself may

produce the Plexin-A1 ligand Sema3A. A possible mechanism may be

that the production and/or secretion of Sema3A in BV-2 cells is

facilitated by LPS, after which Sema3A binds with Plexin-A1 to

activate BV-2 cells in an autocrine manner. To test the

possibility, BV-2 cells were treated with LPS and examined for

evidence of Sema3A mRNA production and Sema3A protein secretion in

the culture medium. Two-hour LPS treatment of BV-2 cells

significantly increased Sema3A mRNA levels (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, 4-h LPS treatment

of BV-2 cells induced the appearance of proteolytically processed

Sema3A (65 kDa; Fig. 5B) in the

supernatant, as shown in other experimental systems (33–35). The data suggest that the

production and secretion of Sema3A induced by the TLR4 activation

of BV-2 cells may cause Plexin-A1 to function in a signaling loop,

thereby enhancing inflammatory signals and cytokine production. The

above results suggested that Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling is involved

in the increase of LPS-induced NO production through ERK1/2 in BV-2

cells (Figs. 3 and 4). Thus, BV-2 cells transduced with

control NT or Plexin-A1 siRNA were treated with Sema3A in the

presence (100 ng/ml) or absence of LPS to functionally examine

whether Sema3A functions as a ligand for Plexin-A1 in BV-2 cells.

The Sema3A ligand was composed of Sema3A fused with the murine

IgG2A Fc fragment, and the IgG2A Fc fragment alone was utilized as

a negative control. In the presence of LPS, nitrite levels were

increased (Fig. 5C); in its

absence, Sema3A did not induce nitrite production in BV-2 cells.

Following the addition of soluble Sema3A (Fig. 5C), LPS-induced NO production was

intensified in BV-2 cells transduced with NT siRNA. By contrast,

the addition of the IgG2A Fc control made no effect. Enhancement of

LPS responsiveness was not observed in BV-2 cells with Plexin-A1

knockdown (Fig. 5C). Accordingly

it is indicated that Sema3A ligation to Plexin-A1 intensifies NO

generation of BV-2 cells only in the presence of LPS, which

suggests that in BV-2 cells, both LPS and Sema3A are necessary for

the establishment of optimal intracellular signaling to produce

inflammatory mediators. To clarify whether the increase in NO

production from Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling is dependent on the

activation of ERK1/2, we examined whether treatment with ERK1/2

inhibitor suppressed the increase in LPS-induced NO production

following the addition of Sema3A in BV-2 cells. BV-2 cells treated

with LPS, Sema3A, and ERK1/2 inhibitor showed significantly

decreased NO production, as compared with BV-2 cells treated with

only LPS and Sema3A (Fig. 5C).

These findings indicated that Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling was

involved in the increased production of NO through ERK1/2

activation in the microglial response to LPS. These in vitro

results suggested that Plexin-A1 binding by Sema3A is synergized

with LPS engagement of TLR4 on microglia to expand innate

inflammatory responses in the brain.

Discussion

Findings of this study have shown three novel

findings concerning the roles of Plexin-A1 expressed in BV2

microglial cells. First, Plexin-A1 enhances the LPS-induced

increase in inflammatory mediators in BV-2 cells, suggesting that

Plexin-A1 plays a crucial role in the activation process of

microglia. Second, the results clarified that Plexin-A1 in BV-2

cells is involved in the activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathway in

the LPS response. Third, the results indicate that Sema3A-Plexin-A1

signaling increases LPS-induced NO production through ERK

activation in BV-2 cells, thereby demonstrating that part of the

intracellular Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling pathway operates in the

activation of microglia. Results of a previous study (18) have shown that Sema3A-Plexin-A1

signaling increases NO production through crosstalk with TLR4

signaling in primary microglia. However, the mechanisms involved in

the intracellular signaling pathway were not identified. Therefore,

to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study showing the

crucial involvement of Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling in the

LPS-induced production of inflammatory mediators through NF-κB and

ERK activation in microglia.

We confirmed the expression of Plexin-A1 and

Neuropilin-1 with RT-PCR and western blotting in BV-2 cells

(Fig. 1). The binding of Sema3A

to the receptor complex of Neuropilin-1 and Plexin-A1 on the cell

membrane transduces intracellular signaling (36). Our earlier study has confirmed the

involvement of Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling in increased LPS-induced

NO production in primary microglia (18). Similar to primary microglia,

LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells increase the expression of inflammatory

mediators such as iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α (20–22), although previous studies have not

directly demonstrated that Plexin-A1 is involved in the induction

of inflammatory mediators by the stimulation of TLR4. To

investigate the role of Plexin-A1 in BV-2 cells stimulated by LPS,

Plexin-A1 was knocked down using Plexin-A1-specific siRNA and the

expression level of inflammatory mediators was assessed in

microglia with TLR4 activation. As a result, Plexin-A1-specific

siRNA-treated BV-2 cells showed a significant decrease in iNOS,

IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression in LPS-treated cells as compared

with control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 2C). Quantification of the iNOS

protein with western blotting and NO in the culture supernatant

using the Griess reaction showed significant decreases of iNOS and

NO levels in Plexin-A1-specific siRNA treated-BV-2 cells compared

with control siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 3A–C). Since the assessment of cell

viability by MTT assay did not show any significant differences

between Plexin-A1-specific siRNA-treated and control NT

siRNA-treated BV-2 cells, the significant decrease in NO production

may not reflect group-based differences of cell viability.

Accordingly Plexin-A1 is required to increase the expression of

inflammatory mediators in LPS-stimulated BV-2 cells.

During the microglial response to microbial

pathogens and TLR agonists, MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways are

known to regulate the production of inflammatory mediators

(23–26). The decreased generation of iNOS,

IL-1β and TNF-α after targeted silencing of Plexin-A1 led to the

investigation of the potential role of Plexin-A1 in these signaling

pathways (Figs. 2C, 3A and B). Previously, we clarified that

Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling is involved in NO production in primary

microglia by crosstalk with TLR4-mediated signaling (18). Activation of ERK1/2 plays a

crucial role in the induction of iNOS expression in TLR4-stimulated

microglia (27). Sema4D-Plexin-B1

signaling increases NO production through ERK1/2 activation

dependent on inflammatory stimulation in primary microglia

(17). In neuronal cells,

Plexin-A1 is involved in determining the direction of axonal

extension and growth cone collapse in an ERK1/2

activation-dependent manner through crosstalk with Plexin-B1

(28–32). In microglial cells, therefore,

Plexin-A1 signaling may be involved in the production of

inflammatory factors through ERK1/2 activation and cooperative

action with the TLR4 pathway. To clarify the intracellular

signaling molecules located downstream of Plexin-A1 signaling that

have crosstalk with the TLR4 pathway in microglial activation, we

assessed the activation level of NF-κB, IκB-α and ERK1/2 by western

blotting. Phosphorylated NF-κB and IκB-α significantly increased in

control siRNA-treated BV-2 cells 1 h after LPS stimulation as

compared with Plexin-A1-specific siRNA-treated BV2 cells. These

findings suggest that Plexin-A1 is involved in the phosphorylation

of NF-κB and IκB-α in the LPS response of BV-2 cells. In

Plexin-A1-specific siRNA-treated BV-2 cells, LPS treatment induced

a significant increase of phosphorylated NF-κB and IκB-α compared

with vehicle-treated cells (Fig.

4). This result may be explained by the imperfect removal of

Plexin-A1 or the significant phosphorylation of NF-κB and IκB-α

through a pathway other than that of Plexin-A1 signaling. Sema3A

secreted from macrophages enhances the LPS response by acting in an

autocrine manner to activate Plexin-A4-mediated signaling (16). Therefore, the involvement of

Plexin-A4 signaling in LPS-dependent activation in microglia may be

a useful explanation for the fact that even in cells with targeted

silencing of Plexin-A1, phosphorylated NF-κB and IκB-α were

significantly increased with LPS treatment compared with vehicle

treatment. Since Plexin-A1 signaling may strengthen microglial

activation through ERK activation in response to LPS, the level of

phosphorylation of ERK was quantified by western blotting.

Phosphorylated ERK was found to increase significantly in control

siRNA-treated BV-2 cells compared with Plexin-A1-specific

siRNA-treated cells. This result suggests that Plexin-A1 may be

involved in LPS-induced microglial activation through ERK

phosphorylation. Since the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in LPS

treatment of Plexin-A1-specific siRNA-treated BV-2 cells was not

found to be significantly greater than in the vehicle-treated BV-2

cells with Plexin-A1 knockdown, phosphorylation of ERK in the LPS

response may be dependent on Plexin-A1. In the LPS response of

macrophages, Plexin-A4-mediated signaling is involved in c-jun

N-terminal kinase phosphorylation (16), suggesting that plexin receptors

may increase the LPS response through differential pathways,

depending on various cell types or receptor families. Thus,

Plexin-A1 is crucial for the amplification of the LPS response in

microglia.

In BV-2 microglial cells, Sema3A was found to be

secreted by the cell itself in an autocrine manner, as in

macrophages (Fig. 4B). Whereas

injured neurons are suggested to produce Sema3A and Sema3A induces

microglial apoptosis (37),

microglia are also suggested to produce Sema3A which appears to

increase LPS-induced microglial activation through

Plexin-A1-mediated signaling. In control siRNA-treated BV-2 cells,

Sema3A generated a significant increase of LPS-induced NO

production as compared with control IgG, and this increase was

significantly suppressed by pretreatment with ERK inhibitor. By

contrast, NO levels did not increase significantly in BV-2 cells

with targeted knockdown of Plexin-A1 even after treatment with

Sema3A, when compared with the IgG treatment. These results suggest

that Sema3A-Plexin-A1 signaling is involved in the increase of

LPS-induced NO production in activated microglia through ERK

activation. Therefore, both Plexin-A1 and Sema3A are potential

targets for the treatment of encephalopathy triggered by LPS and

neuroinflammation-related mental disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Department

of Physiology of Meijo University for their helpful discussion and

technical assistance. The study was primarily supported by a

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of

Education, Science, Sports and Culture, Japan (No. 22590195), and

research grants from Meijo University.

References

|

1

|

Ransohoff RM and Perry VH: Microglial

physiology: unique stimuli, specialized responses. Annu Rev

Immunol. 27:119–145. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Heppner FL, Greter M, Marino D, et al:

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis repressed by microglial

paralysis. Nat Med. 11:146–152. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jack C, Ruffini F, Bar-Or A and Antel JP:

Microglia and multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 81:363–373. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ponomarev ED, Shriver LP and Dittel BN:

CD40 expression by microglial cells is required for their

completion of a two-step activation process during central nervous

system autoimmune inflammation. J Immunol. 176:1402–1410. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Lee SJ and Lee S: Toll-like receptors and

inflammation in the CNS. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy.

1:181–191. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tran TS, Kolodkin AL and Bharadwaj R:

Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annu Rev Cell Dev

Biol. 23:263–292. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gu Y, Filippi MD, Cancelas JA, et al:

Hematopoietic cell regulation by Rac1 and Rac2 guanosine

triphosphatases. Science. 302:445–449. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, et al:

Guidance of myocardial patterning in cardiac development by Sema6D

reverse signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 6:1204–1211. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Neufeld G and Kessler O: The semaphorins:

versatile regulators of tumour progression and tumour angiogenesis.

Nat Rev Cancer. 8:632–645. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Suzuki K, Kumanogoh A and Kikutani H:

Semaphorins and their receptors in immune cell interactions. Nat

Immunol. 9:17–23. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Walzer T, Galibert L and De Smedt T:

Dendritic cell function in mice lacking Plexin C1. Int Immunol.

17:943–950. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Choi YI, Duke-Cohan JS, Ahmed WB, et al:

PlexinD1 glycoprotein controls migration of positively selected

thymocytes into the medulla. Immunity. 29:888–898. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yamamoto M, Suzuki K, Okuno T, et al:

Plexin-A4 negatively regulates T lymphocyte responses. Int Immunol.

20:413–420. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Wong AW, Brickey WJ, Taxman DJ, et al:

CIITA-regulated plexin-A1 affects T-cell-dendritic cell

interactions. Nat Immunol. 4:891–898. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Takegahara N, Takamatsu H, Toyofuku T, et

al: Plexin-A1 and its interaction with DAP12 in immune responses

and bone homeostasis. Nat Cell Biol. 8:615–622. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wen H, Lei Y, Eun SY and Ting JP:

Plexin-A4-semaphorin 3A signaling is required for Toll-like

receptor- and sepsis-induced cytokine storm. J Exp Med.

207:2943–2957. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Okuno T, Nakatsuji Y, Moriya M, et al:

Roles of Sema4D-plexin-B1 interactions in the central nervous

system for pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune

encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 184:1499–1506. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ito T, Yoshida K, Negishi T, et al:

Plexin-A1is required for Toll-like receptor-mediated microglial

activation in the development of lipopolysaccharide-induced

encephalopathy. Int J Mol Med. 33:1122–1130. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Blasi E, Barluzzi R, Bocchini V, Mazzolla

R and Bistoni F: Immortalization of murine microglial cells by a

v-raf/v-myc carrying retrovirus. J Neuroimmunol. 27:229–237. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Zeng KW, Wang S, Dong X, Jiang Y and Tu

PF: Sesquiterpene dimer (DSF-52) from Artemisia argyi

inhibits microglia-mediated neuroinflammation via suppression of

NF-κB, JNK/p38 MAPKs and Jak2/Stat3 signaling pathways.

Phytomedicine. 21:298–306. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Manivannan J, Tay SS, Ling EA and Dheen

ST: Dihydropyrimidinase-like 3 regulates the inflammatory response

of activated microglia. Neuroscience. 253:40–54. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Oh WJ, Jung U, Eom HS, Shin HJ and Park

HR: Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced proinflammatory

responses by Buddleja officinalis extract in BV-2 microglial cells

via negative regulation of NF-κB and ERK1/2 signaling. Molecules.

18:9195–9206. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kaminska B: MAPK signalling pathways as

molecular targets for anti-inflammatory therapy - from molecular

mechanisms to therapeutic benefits. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1754:253–262. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kaminska B, Gozdz A, Zawadzka M,

Ellert-Miklaszewska A and Lipko M: MAPK signal transduction

underlying brain inflammation and gliosis as therapeutic target.

Anat Rec (Hoboken). 292:1902–1913. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Koistinaho M and Koistinaho J: Role of p38

and p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinases in microglia. Glia.

40:175–183. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Johnson GL and Lapadat R:

Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and

p38 protein kinases. Science. 298:1911–1912. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Bhat NR, Zhang P, Lee JC and Hogan EL:

Extracellular signal regulated kinase and p38 subgroups of

mitogen-activated protein kinases regulate inducible nitric oxide

synthase and tumor necrosis factor-α gene expression in

endotoxin-stimulated primary glial cultures. J Neurosci.

18:1633–1641. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Bechara A, Nawabi H, Moret F, et al:

FAK-MAPK-dependent adhesion disassembly downstream of L1

contributes to semaphorin3A-induced collapse. EMBO J. 27:1549–1562.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Lerman O, Ben-Zvi A, Yagil Z and Behar O:

Semaphorin3A accelerates neuronal polarity in vitro and in its

absence the orientation of DRG neuronal polarity in vivo is

distorted. Mol Cell Neurosci. 36:222–234. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Bagnard D, Sainturet N, Meyronet D, et al:

Differential MAP kinases activation during semaphorin3A-induced

repulsion or apoptosis of neural progenitor cells. Mol Cell

Neurosci. 25:722–731. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Campbell DS and Holt CE: Apoptotic pathway

and MAPKs differentially regulate chemotropic responses of retinal

growth cones. Neuron. 37:939–952. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kruger RP, Aurandt J and Guan KL:

Semaphorins command cells to move. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

6:789–800. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Adams RH, Lohrum M, Klostermann A, Betz H

and Püschel AW: The chemorepulsive activity of secreted semaphorins

is regulated by furin-dependent proteolytic processing. EMBO J.

16:6077–6086. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Catalano A, Caprari P, Moretti S, Faronato

M, Tamagnone L and Procopio A: Semaphorin-3A is expressed by tumor

cells and alters T-cell signal transduction and function. Blood.

107:3321–3329. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Lepelletier Y, Moura IC, Hadj-Slimane R,

et al: Immunosuppressive role of semaphorin-3A on T cell

proliferation is mediated by inhibition of actin cytoskeleton

reorganization. Eur J Immunol. 36:1782–1793. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Banks WA and Erickson MA: The blood-brain

barrier and immune function and dysfunction. Neurobiol Dis.

37:26–32. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Majed HH, Chandran S, Niclou SP, et al: A

novel role for Sema3A in neuroprotection from injury mediated by

activated microglia. J Neurosci. 26:1730–1738. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|