Introduction

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) is a secretory glycoprotein and

acts as an autocrine and paracrine factor (1). Shh binds to its receptor, patched 1

(Ptch1). In conditions in which Shh is inactivated, Ptch1 inhibits

the action of the receptor, Smoothened. When Shh binds to Ptch1,

this suppression of Smoothened is reversed, which in turn activates

the transcription factor, Gli1 (1,2).

Gli1 upregulates several downstream signaling genes, including

Ptch1 and Gli1 (3,4). Shh plays an important role in the

developmental process, which includes the regulation of axonal

guidance, cell differentiation and the proliferation of neural

progenitor cells (NPCs) (5–7).

In adults, Shh, is involved in hypoxia-induced neural progenitor

proliferation in the brain injured by stroke (8), controls stem cell maintenance in

post-natal and adult brain neurogenesis (9), regulates angiogenesis and

vasculogenesis (10,11) and strengthens vascular tightness

(12).

Angiopoietin (Ang)-1 and Ang-2 belong to the

angiopoietin family, and play an important role in blood vessel

formation both in normal development and pathological conditions

(13,14). The balance between Ang-1 and Ang-2

is important for the maintenance of the vasculature network

(15). Ang-1 upregulates vascular

integrity by modulating tight junction proteins (16,17), enhances endothelial regeneration

in diabetic mice (18) and

recovers ischemic limb injury through the recruitment of bone

marrow-derived progenitor cells (19). In addition to the role of Ang-1

and Ang-2 in angiogenesis, previous studies have shown that they

have a broad target cell spectrum. Ang-1 blocks cell death and

improves the survival of fibroblasts, skeletal myocytes and

cardiomyocytes (20–22). It also induces neurite outgrowth

(23), as well as the

proliferation and differentiation of NPCs (24). Ang-2 also regulates NPC

differentiation and migration (25). These reports indicate the

importance of angiopoietin as a broad spectrum regulatory

factor.

We have previously reported that Shh affects Ang-1

and Ang-2 mRNA expression only in fibroblasts (26). In the present study, we

demonstrate that Shh is produced by neurons, and that the mRNA

expression of Ang-1 and Ang-2 in fibroblasts is modulated by

co-culture with neurons, without exogenous Shh treatment. Moreover,

Shh-neutralizing antibody significantly blocked the regulation of

Ang-1 and Ang-2 in fibroblasts which was induced by co-culture with

neurons. Our data suggest that fibroblasts and neurons communicate

with each other through Shh signaling. Thus, we propose the concept

of fibroblast/neuron cross-talk.

Materials and methods

Animals, cell isolation and culture of

neural progenitors and neurons

All the animal experiments were performed under the

approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Subcommittee of

Inha University Hospital (Incheon, Korea). For the culture of fresh

NPCs, the cortices of fetuses obtained from CD1 mice [embryonic day

(E)14–16] were isolated, minced and incubated in a PBS solution

with 0.25% trypsin and 0.01% DNase I for 20 min as previously

described (26). The cells were

resuspended in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,

USA) containing 1% FBS, N2 supplement (Gibco/Invitrogen), 0.6%

glucose, HEPES (50 mmol/l), bFGF (20 ng/ml), EGF (20 ng/ml),

heparin (5 μg/ml) and penicillin/streptomycin/amphotericin B (1:100

dilution; Gibco/Invitrogen). The cells were plated at

2×105 cells/well into 24-well plates coated with

poly-D-lysine and laminin (PDL/L plates; Biocoat Inc., Horsham, PA,

USA; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). After 24 h, 1% FBS

was removed. For the neuron cultures, mouse cortices (E15–17) were

harvested as described in our previous study (26). The cells were seeded at

3×105 cells/well into PDL/L plates (Biocoat Inc.) and

cultured in defined neuron culture medium; neurobasal medium

(Gibco, Invitrogen) containing 2% B27, glutamine (2 mmol/l) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin. On days 1–3, glutamate (25 μg/ml) and

β-mercaptoethanol (10 μmol/l) were added. On day 3, Ara-C (10

μmol/l) was added for 24 h, and the medium was then exchanged with

fresh defined neuron culture medium.

Cell line and reagents

NIH3T3 mouse embryonic fibroblasts were purchased

[American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA, USA] and

cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS (Gibco/Invitrogen) and 1%

penicillin/streptomycin. Mouse recombinant Shh (mrShh) was

purchased from GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA; Cat. no. Z03050) and

the cells were incubated with 10 or 50 nM rShh for 16 h. MAB4641, a

neutralizing antibody against Shh [10 μg/m; R&D Systems

(Minneapolis, MN, USA)] was used for the specific blocking of Shh

in the culture medium.

Quantitative (real-time) reverse

transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using the QIAshredder and

the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA (1–2 μg)

was converted into cDNA using the PrimeScriptTM 1st

strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan). For

real-time PCR assay, mouse Ang-1, Ang-2, Ptch1, Shh and Gli1 were

analyzed with an ABI TaqMan Gene Expression Assay primer and FAM

probe sets (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Transcript

levels were normalized to the 18S rRNA. Real-time samples were run

on an ABI PRISM-7500 sequence detection system (Applied

Biosystems). In addition, end-point PCR for Ang-1 and Ang-2 was

performed using following primers and GAPDH was used for

normalization: Ang-1 forward, 5′-aaacagcaaatgggaacagg-3′ and

reverse, 5′-gggcaggtgaactccactaa-3′ (melting temperature, 60°C; 35

cycles); Ang-2 forward, 5′-caaggcactgagagacacca-3′ and reverse,

5′-ctgaactcccacggaacatt-3′ (melting temperature, 60°C; 35 cycles);

and GAPDH forward, 5′-ccactggcgtcttcaccac-3′ and reverse,

5′-cctgcttcaccaccttcttg-3′ (melting temperature, 60°C; 27

cycles).

Western blot analysis

The cells were harvested and lysed in lysis buffer

(40 mM Tris pH 7.4, 10 mM EDTA, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40) containing

protease inhibitors (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany).

Total protein (10–30 μg) was fractionated in SDS-PAGE and

immunoblotted with specific antibodies against Ang-1 (Novus

Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) and Ang-2 (Novus Biologicals).

Actin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used as an internal

control. We used the Kodak Image Station 400R to detect the bands

and Kodak Molecular Imaging Software version 4.0. The

quantification of band intensity was analysed using TINA 2.0

(Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany) and normalized to the intensity

of actin.

Co-culture assay

Neurons and NIH3T3 fibroblasts were co-cultured as

previously described with certain modifications (16). Fibroblasts were seeded at the

bottom of a 12-well plate. Neurons were plated into a Transwell

chamber at 2×105 cells/well (pore size, 0.4 μm; Corning

Life Science, Tewksbury, MA, USA). The Transwell chamber with the

confluent neurons was then placed in the 12-well plate and was

further incubated for 16 h in the defined neuron culture medium.

During co-culture, a neutralizing antibody against Shh (MAB4641; 10

μg/ml; R&D Systems) was added to the bottom well. Total RNA was

extracted from the fibroblasts to evaluate the effects of Shh

secreted from the neurons.

Statistical analysis

All the results are expressed as the means ±

standard deviation. The differences between the groups were

compared by an unpaired t-test or one-way analysis of variance

(ANOVA). P-values ≤0.05 were considered to indicate statistically

significant differences. All statistical analyses were performed

using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Results

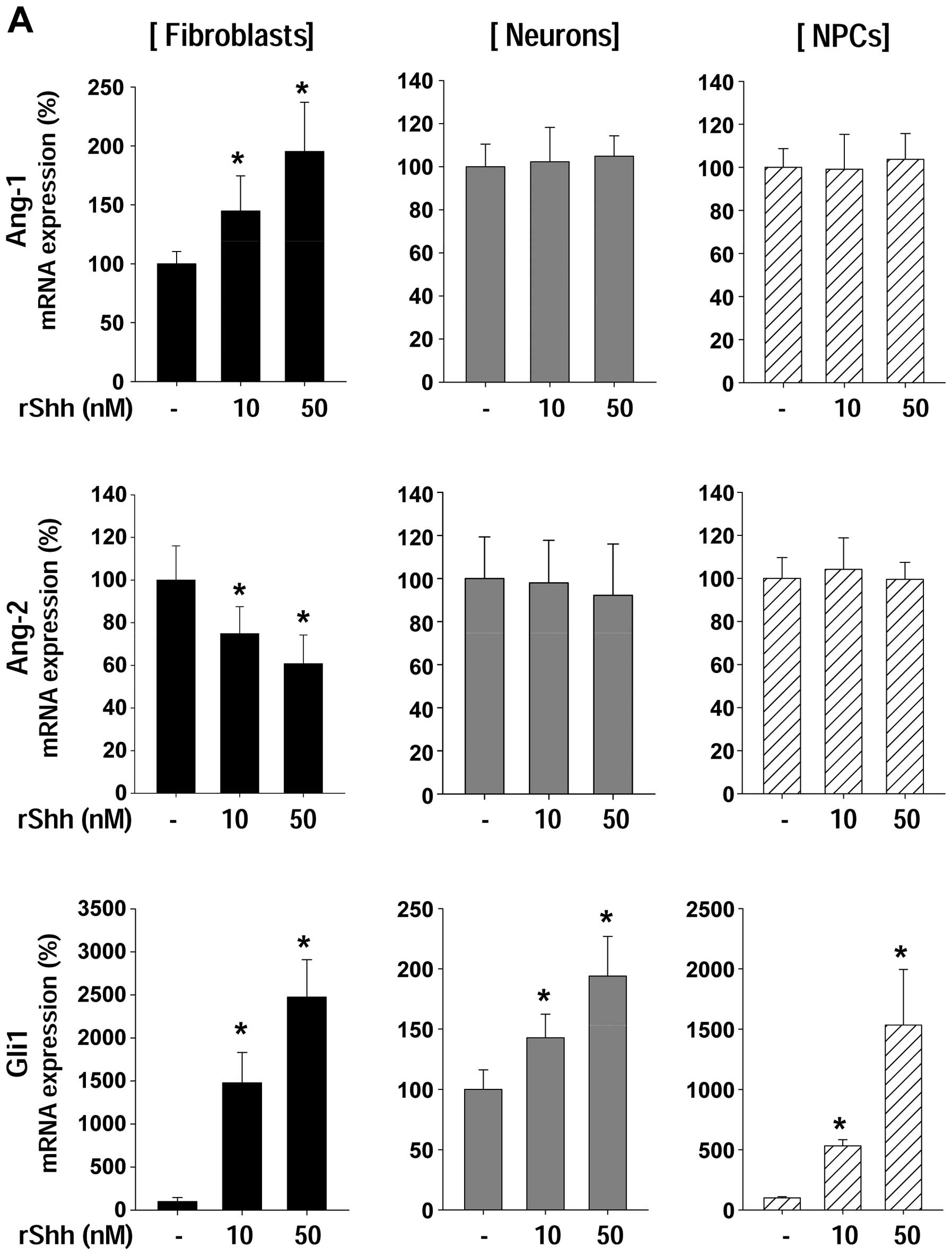

rShh regulates the expression of Ang-1

and Ang-2 in fibroblasts, but not in neurons and NPCs

We determined the expression of Ang-1 and Ang-2

following treatment with recombinant sonic hedgehog (rShh)

(Fig. 1A). Ang-1 mRNA expression

was increased in fibroblasts only, whereas Ang-2 mRNA expression

was decreased by rShh treatment. Ang-1 and Ang-2 mRNA expression

showed no change in either the neurons or the NPCs. Glil mRNA

levels significantly increased following treatment with rShh in all

cell types, indicating that neurons and NPCs responded to rShh

normally; however, rShh did not affect Ang-1 and Ang-2 mRNA

expression in neurons and NPCs (Fig.

1A), which is in accordance with the results of our previous

study (26). To confirm the

effects of rShh on angiopoietin at the protein level we performed

western blot anlaysis (Fig. 1B).

Ang-1 protein expression showed a marked increase in a

dose-dependent manner, while Ang-2 expression decreased in a

dose-dependent manner.

Shh-expressing cells and Shh-responsive

cells differ

We then investigated Shh mRNA expression in 3 types

of cells, fibroblasts, neurons and NPCs, in order to determine Shh

basal levels (Fig. 2A). Shh was

not expressed in fibroblasts, but it was expressed in both neurons

and NPCs. Of note, Shh expression levels in the neurons were much

higher than those in the NPCs (Fig.

2A). It is known that Shh acts in an autocrine and paracrine

manner (1). Shh binds to its

receptor, Ptch1, and activates its signaling with the upregulation

of Ptch1 and Gli1 expression (3).

Thus, we examined the mRNA expression of Ptch1 and Gli1 to clarify

which cells are influenced by rShh (Fig. 2B and C). We hypothesized that rShh

mainly affects neurons even though all 3 types of cells were

affected by rShh, as endogenous Shh was highly synthesized in

neurons. It should be noted however, that Shh downstream signaling,

Ptch1 and Gli1, was upregulated in fibroblasts, but not in neurons

(Fig. 2B and C). These data

indicate that although neurons are one of the major cell sources

for Shh expression, fibroblasts are the most responsive cells to

Shh. Therefore, we suggest that Shh-expressing cells and

Shh-responsive cells differ, and we suggest the existence of a cell

cross-talk in Shh-mediated angiopoietin regulation.

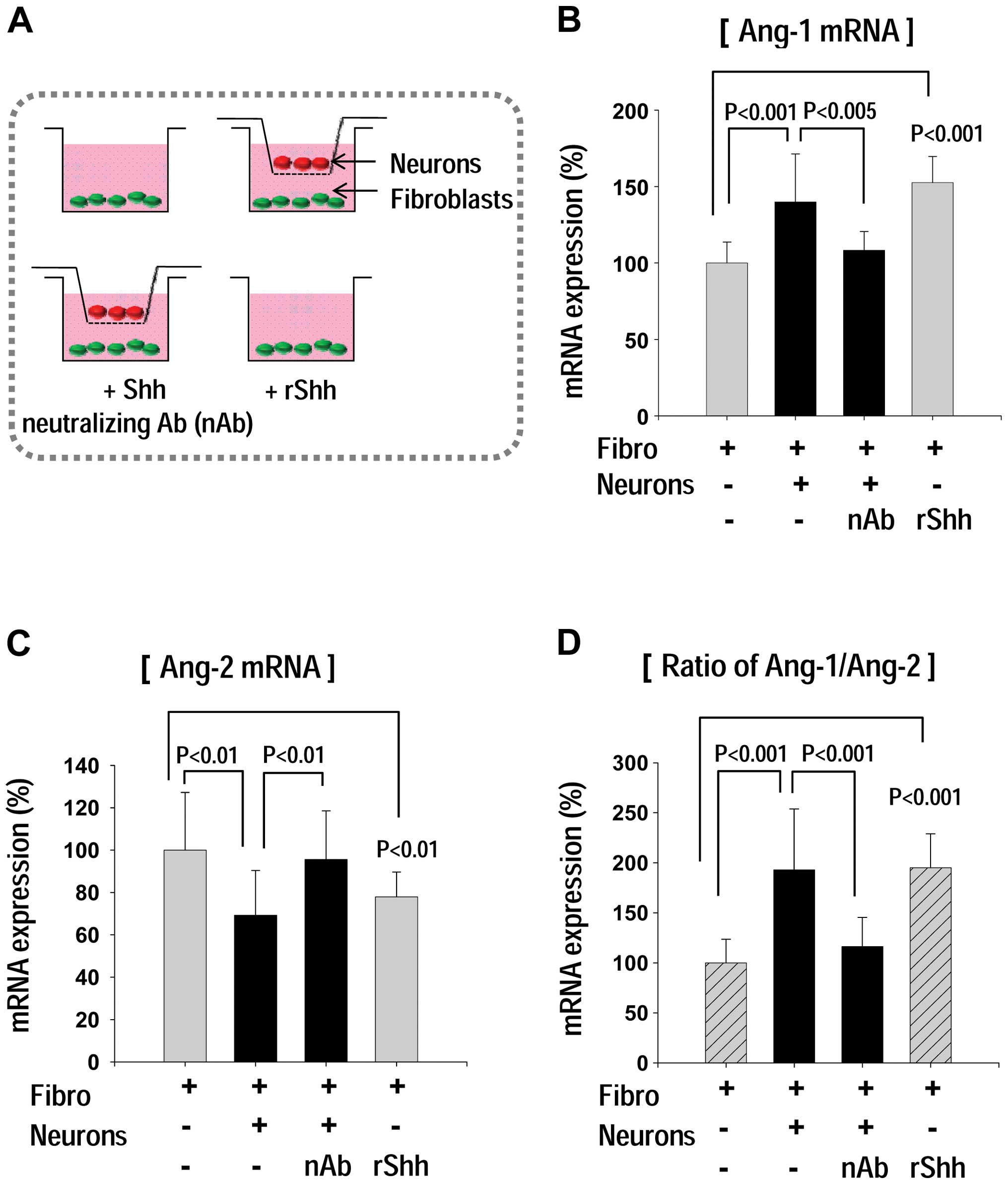

Shh secreted by neurons regulates Ang-1

and Ang-2 gene expression in fibroblasts in a co-culture

system

As shown in Fig.

2, we found that Shh expression was markedly increased in

neurons, whereas Shh mainly affects fibroblasts as opposed to

neurons. We suggested the existence of a cross-talk between neurons

and fibroblasts. To confirm our hypothesis, we performed co-culture

assay (Fig. 3). Fibroblasts were

seeded at the bottom well of 12-well plate, and then a Transwell

chamber with confluent neurons was placed in the 12-well plate

(Fig. 3A). Following further

incubation, total RNA was extracted from the fibroblasts and the

Ang-1 and Ang-2 mRNA expression was determined (Fig. 3B–D). It is of interest to note

that Ang-1 expression was markedly increased only when the neuron

co-culture system was used (Fig.

3B). Moreover, the co-culture-induced Ang-1 upregulation was

markedly inhibited by the addition of a Shh-neutralizing antibody

(MAB4641; Fig. 3B). On the other

hand, Ang-2 mRNA expression in the fibroblasts decreased in the

co-culture group; however, this reduction in Ang-2 expression

following co-culture was reversed by the addition of

Shh-neutralizing antibody (Fig.

3C). Our results suggest that Shh released from neurons, which

may influence neighboring fibroblasts, thus regulating Ang-1 and

Ang-2 expression (Fig. 3E).

Discussion

In this study, we found that neurons and fibroblasts

communicate with each other and that the main source of Shh

expression is from neurons, not fibroblasts or NPCs. In addition,

the regulation of angiopoietin expression in fibroblasts was

affected by neurons in the co-culture system, suggesting the

existence of a cross-talk between neurons and fibroblasts. Lately,

the importance of gaining an understanding of the communication

pathway between different cell types has been emphasized in the

research field of drug development. In the research area of

neurovascular and oligovascular units, there is increasing evidence

that there is a communication between blood vessels and brain cells

(27,28). Cerebral endothelial cells may

secrete trophic factors that affect neighboring cells (27,28). Likewise, astrocytes/endothelial

coupling regulate the development of the cerebral vasculature,

i.e., the blood-brain barrier, through Ang-1 (16). Nerves serve as a template for

arteries and determine the arterial differentiation through the

vascular endothelial growth factor (29,30). Osteoblast-secreted Ang-1 promotes

the survival and maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells (31). Endothelial cells stimulate

fibroblast differentiation following ischemic injury and therefore

increase tissue fibrosis following myocardial infarction (32). These studies have shown that the

complex interplay between types of cells is extensively regulated

in normal physiology.

As this cell cross-talk between cells may involve

common growth factors and may be regulated in an interconnected

manner, molecules, such as Shh hold great therapeutic potential.

Shh upregulates vascularization and osteoblastic differentiation

(33), and can also regulate both

angiogenesis and myogenesis (34). Ang-1 decreases both vascular

damage and cardiomyocyte death, thus improving cardiac function

following myocardial infarction (17). Ang-1 also stimulates muscle

regeneration after muscle injury in mice by promoting muscle

satellite cell self-renewal (35).

Moreover, previous studies have suggested that the

combined transplantation of different cell types improves

therapeutic potential. Vascular regeneration in hindlimb ischemia

was shown to be enhanced by the transplantation of a combination of

embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial and mural cells, compared

with single-cell transplantation (36). The combination of Shh gene

transfer and bone marrow-derived progenitor cells has also been

shown to improve angiogenesis and muscle regeneration in limb

ischemia to a greater degree than with each treatment individually

(37). Therefore, an improved

understanding of cell communication and the functions of regulatory

cytokines, such as Shh may provide a novel strategy for the

regeneration of damaged tissue.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Basic Science

Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea

(NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning

(2013R1A1A3012024, awarded to Sae-Won Lee), and by the Basic

Science Research Program through the NRF grant funded by the

Ministry of Education (NRF-2009-0076309, NRF-2011-0025506, awarded

to Woo Jean Kim).

References

|

1

|

Rowitch DH, BSJS, Jacques B, Lee SM, Flax

JD, Snyder EY and McMahon AP: Sonic hedgehog regulates

proliferation and inhibits differentiation of CNS precursor cells.

J Neurosci. 19:8954–8965. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Taipale J, Cooper MK, Maiti T and Beachy

PA: Patched acts catalytically to suppress the activity of

Smoothened. Nature. 418:892–897. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zedan W, Robinson PA, Markham AF and High

AS: Expression of the Sonic Hedgehog receptor “PATCHED” in basal

cell carcinomas and odontogenic keratocysts. J Pathol. 194:473–477.

2001.

|

|

4

|

Osterlund T and Kogerman P: Hedgehog

signalling: how to get from Smo to Ci and Gli. Trends Cell Biol.

16:176–180. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu G, Mehler MF, Zhao J, Yu Yung S and

Kessler JA: Sonic hedgehog and BMP2 exert opposing actions on

proliferation and differentiation of embryonic neural progenitor

cells. Dev Biol. 215:118–129. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wang YP, Dakubo G, Howley P, et al:

Development of normal retinal organization depends on Sonic

hedgehog signaling from ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci. 5:831–832.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Charron F, Stein E, Jeong J, McMahon AP

and Tessier-Lavigne M: The morphogen sonic hedgehog is an axonal

chemoattractant that collaborates with netrin-1 in midline axon

guidance. Cell. 113:11–23. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sims JR, Lee SW, Topalkara K, et al: Sonic

hedgehog regulates ischemia/hypoxia-induced neural progenitor

proliferation. Stroke. 40:3618–3626. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Palma V, Lim DA, Dahmane N, et al: Sonic

hedgehog controls stem cell behavior in the postnatal and adult

brain. Development. 132:335–344. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pola R, Ling LE, Silver M, et al: The

morphogen Sonic hedgehog is an indirect angiogenic agent

upregulating two families of angiogenic growth factors. Nat Med.

7:706–711. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Surace EM, Balaggan KS, Tessitore A, et

al: Inhibition of ocular neovascularization by hedgehog blockade.

Mol Ther. 13:573–579. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xia YP, He QW, Li YN, et al: Recombinant

human sonic hedgehog protein regulates the expression of ZO-1 and

occludin by activating angiopoietin-1 in stroke damage. PLoS One.

8:e688912013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Davis S, Aldrich TH, Jones PF, et al:

Isolation of angiopoietin-1, a ligand for the TIE2 receptor, by

secretion-trap expression cloning. Cell. 87:1161–1169. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge

JS, Wiegand SJ and Holash J: Vascular-specific growth factors and

blood vessel formation. Nature. 407:242–248. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Carmeliet P: Angiogenesis in health and

disease. Nat Med. 9:653–660. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lee SW, Kim WJ, Choi YK, et al: SSeCKS

regulates angiogenesis and tight junction formation in blood-brain

barrier. Nat Med. 9:900–906. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee SW, Kim WJ, Jun HO, Choi YK and Kim

KW: Angiopoietin-1 reduces vascular endothelial growth

factor-induced brain endothelial permeability via upregulation of

ZO-2. Int J Mol Med. 23:279–284. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jin HR, Kim WJ, Song JS, et al:

Intracavernous delivery of a designed angiopoietin-1 variant

rescues erectile function by enhancing endothelial regeneration in

the streptozotocin-induced diabetic mouse. Diabetes. 60:969–980.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Youn SW, Lee SW, Lee J, et al: COMP-Ang1

stimulates HIF-1alpha-mediated SDF-1 overexpression and recovers

ischemic injury through BM-derived progenitor cell recruitment.

Blood. 117:4376–4386. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Carlson TR, Feng Y, Maisonpierre PC,

Mrksich M and Morla AO: Direct cell adhesion to the angiopoietins

mediated by integrins. J Biol Chem. 276:26516–26525. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Dallabrida SM, Ismail N, Oberle JR, Himes

BE and Rupnick MA: Angiopoietin-1 promotes cardiac and skeletal

myocyte survival through integrins. Circ Res. 96:e8–e24. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee SW, Won JY, Lee HY, et al:

Angiopoietin-1 protects heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury

through VE-cadherin dephosphorylation and myocardiac

integrin-beta1/ERK/caspase-9 phosphorylation cascade. Mol Med.

17:1095–1106. 2011.

|

|

23

|

Chen X, Fu W, Tung CE and Ward NL:

Angiopoietin-1 induces neurite outgrowth of PC12 cells in a

Tie2-independent, beta1-integrin-dependent manner. Neurosci Res.

64:348–354. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rosa AI, Goncalves J, Cortes L, Bernardino

L, Malva JO and Agasse F: The angiogenic factor angiopoietin-1 is a

proneurogenic peptide on subventricular zone stem/progenitor cells.

J Neurosci. 30:4573–4584. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Liu XS, Chopp M, Zhang RL, et al:

Angiopoietin 2 mediates the differentiation and migration of neural

progenitor cells in the subventricular zone after stroke. J Biol

Chem. 284:22680–22689. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Lee SW, Moskowitz MA and Sims JR: Sonic

hedgehog inversely regulates the expression of angiopoietin-1 and

angiopoietin-2 in fibroblasts. Int J Mol Med. 19:445–451.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lok J, Gupta P, Guo S, et al: Cell-cell

signaling in the neurovascular unit. Neurochem Res. 32:2032–2045.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Arai K and Lo EH: Oligovascular signaling

in white matter stroke. Biol Pharm Bull. 32:1639–1644. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mukouyama YS, Shin D, Britsch S, Taniguchi

M and Anderson DJ: Sensory nerves determine the pattern of arterial

differentiation and blood vessel branching in the skin. Cell.

109:693–705. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Carmeliet P and Tessier-Lavigne M: Common

mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature. 436:193–200.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, et al:

Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell

quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 118:149–161. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lee SW, Won JY, Kim WJ, et al: Snail as a

potential target molecule in cardiac fibrosis: paracrine action of

endothelial cells on fibroblasts through snail and CTGF axis. Mol

Ther. 21:1767–1777. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Dohle E, Fuchs S, Kolbe M, Hofmann A,

Schmidt H and Kirkpatrick CJ: Sonic hedgehog promotes angiogenesis

and osteogenesis in a coculture system consisting of primary

osteoblasts and outgrowth endothelial cells. Tissue Eng Part A.

16:1235–1237. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Straface G, Aprahamian T, Flex A, et al:

Sonic hedgehog regulates angiogenesis and myogenesis during

post-natal skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Mol Med.

13:2424–2435. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Abou-Khalil R, Le Grand F, Pallafacchina

G, et al: Autocrine and paracrine angiopoietin 1/Tie-2 signaling

promotes muscle satellite cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell.

5:298–309. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yamahara K, Sone M, Itoh H, et al:

Augmentation of neovascularization [corrected] in hindlimb ischemia

by combined transplantation of human embryonic stem cells-derived

endothelial and mural cells. PLoS One. 3:e16662008.

|

|

37

|

Palladino M, Gatto I, Neri V, et al:

Combined therapy with sonic hedgehog gene transfer and bone

marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells enhances angiogenesis

and myogenesis in the ischemic skeletal muscle. J Vasc Res.

49:425–431. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|