Introduction

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and

glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) are incretin

hormones that regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells.

GLP-1 and GIP are secreted by the small intestine in response to

meal ingestion. GLP-1 is secreted from L cells in the lower small

intestine, while GIP is secreted from K cells in the upper small

intestine. These incretins stimulate insulin secretion from β cells

by binding to the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) and GIP receptor (GIPR).

Incretins also have extra-pancreatic functions in a variety of

tissues. For example, GLP-1 affects the central nervous system,

resulting in neuroprotection against amyloid β (1) and the suppression of appetite

(2). It has also been reported to

increase glucose uptake in the cardiovascular system (3) and prolong gastric acid secretion

(4). GIP affects the central

nervous system by stimulating memory recognition and

neuroprotection (5). Several

studies have also demonstrated that GIP mediates lipogenesis in

adipocytes (6) and bone

remodeling (7).

The incretin receptors, GLP-1R and GIPR, play

important roles in glucose metabolism. GLP-1R and GIPR are members

of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. GLP-1R and GIPR

are expressed in a variety of organs, such as the pancreas,

stomach, intestine, heart, lungs, pituitary gland and brain

(8,9). However, GLP-1R, but not GIPR, is

expressed in the kidneys. In addition, GIPR, but not GLP-1R, is

expressed in the adrenal cortex, adipose tissue and bone (9,10).

The binding of incretins to their receptors activates adenylate

cyclase, which increases intracellular cyclic adenosine

monophosphate (cAMP) and is followed by changes in the

intracellular Ca2+ concentration, ATP production in the

mitochondria and insulin secretion (11).

There is a correlation between glucose metabolism

and bone metabolism. For example, insulin signals in osteoblasts

activate osteocalcin production, which enhances glucose metabolism.

However, this activation does not occur under conditions of

impaired bone resorption (12).

The expression of insulin and adiponectin receptors increases

during osteoblastic differentiation (13). Adiponectin, which regulates

glucose and lipid metabolism, stimulates bone morphogenetic

protein-2 (BMP-2) expression in osteoblasts (14).

Incretins act in an insulin-dependent or

-independent manner. The GLP-1-mediated suppression of hepatic

glucose production is one of the insulin-independent effects

(15). However, the

insulin-dependent effects of GLP-1 are still controversial. For

example, it is unclear whether the effects of GLP-1 on adipocytes

are dependent on or independent of insulin since the direct role of

GLP-1R on adipocytes has not been experimentally confirmed

(16–18). It has been suggested that

incretins have a direct effect on bone as the genetic disruption of

pancreatic GLP-1R increases bone resorption in mice (19,20). Although GIPR is expressed in

osteoblasts (21), it is unclear

whether GLP-1R is also expressed in osteoblasts. GIP has been

reported to inhibit bone resorption and enhance bone formation by

stimulating osteoblast proliferation and inhibiting osteoblast

apoptosis (22). Notably,

GIPR-knockout mice exhibit reduced bone strength and quality

(23,24).

The objective of this study was to clarify the

presence of GLP-1R and GIPR in mouse osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells

and examine the associaiton between incretin receptors in

osteoblasts and glucose metabolism.

Materials and methods

Materials

MC3T3-E1 cells, a mouse osteoblastic cell line, were

obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). The reagent

used for total RNA isolation (RNA STAT-60™) was purchased from

Amsbio (Abingdon, UK). Rabbit polyclonal anti-GLP-1R and GIPR

antibodies, which cross-react with mouse antigens, were obtained

from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) was

purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). The other

reagents used were of the highest grade commercially available.

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1, mouse osteoblast-like cells, were

maintained at 37°C under 95% air/5% CO2 in Minimum

Essential Medium Eagle α modification (α-MEM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO,

USA) containing 5.6 mM glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml

streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; SAFC Biosciences,

Lenexa, KS, USA). For glucose and BMP-2 treatment,

3.75×104 cells were seeded onto 35-mm dishes and

incubated overnight at 37°C. The dishes were then randomly divided

into 8 groups and were incubated in medium containing normal (5.6

mM) or high (10, 20 or 30 mM) glucose concentrations without or

with 100 ng/ml rhBMP-2.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR)

The MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in α-MEM

supplemented with 10% FBS and 5.6 mM glucose for 72 h. Total RNA

was then isolated using RNA STAT-60™ reagent according to the

instructions provided by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized

from 1.0 μg of total RNA with oligo(dT) primers using SuperScript™

III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA) under

the conditions suggested by the manufacturer. GLP-1R, GIPR and

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA expression

was detected by RT-PCR using the following primers (forward and

reverse), as previously described: GLP-1R, 5′-GGAGTGTGAAGAGTC

TAAGC-3′ and 5′-GCAGTACTGCATGAGCAGGA-3′ (25); GIPR, 5′-CTGCCTGCCGCACGGCCCAGAT-3′

and 5′-GCG AGCCAGCCTCAGCCGGTAA-3′ (22); GAPDH, 5′-ACCACA GTCCATGCCATCAC-3′

and 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCT GTA-3′. For GLP-1R, the PCR conditions

comprised an initial activation of polymerase at 94°C for 10 min,

followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing

at 59°C for 30 sec, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final

extension at 72°C for 10 min. For GIPR, the PCR conditions

comprised an initial denaturation at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35

cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec, annealing at 65°C for 30

sec, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at

72°C for 10 min. The quality of the template was examined by

amplifying GAPDH cDNA in each PCR condition. The amplified PCR

products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel in

Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer, stained with ethidium bromide and

photographed under ultraviolet transillumination.

Quantitative PCR

The cells were seeded at a density of

3.75×104 cells in 35-mm dishes and maintained at 37°C.

The following day, the medium was substituted with medium

containing various concentrations of glucose, as described above.

Total RNA was isolated from the cells following culture for 24, 48

and 72 h, and was converted to cDNA. Four samples were prepared for

each treatment. Quantitative PCR assays were carried out in

triplicate for each sample using a StepOne™ Real-Time PCR System

(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR analyses were

conducted with gene-specific primers and fluorescently labeled

TaqMan GLP-1R-specific probes (Mm00445292_m1), GIPR

(Mm01316344_m1), Runx2 (Mm00501580_m1), alkaline phosphatase (ALP,

Mm01285814_g1) and GAPDH (Mm99999915_g1). The PCR conditions

comprised activation at 95°C for 20 sec, followed by 40 cycles of

95°C for 1 sec and 60°C for 20 sec. The ΔΔCt method of relative

quantification was used to determine the fold change in the

expression of each gene. First, the threshold cycle (Ct) of the

target mRNAs was normalized to the Ct values of the internal

control (GAPDH) in the same sample (ΔCt = Cttarget −

CtGAPDH), which was followed by normalization to the

control (ΔΔCt = ΔCtsample − ΔCtcontrol). The

fold change in expression was calculated as the relative

quantification value (RQ; 2−ΔΔCt).

Western blot analysis

Total protein was extracted from confluent cells

cultured for 72 h on 60-mm dishes in normal- (5.6 mM) or

high-glucose (30 mM) medium with or without BMP-2. Briefly, the

cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS),

scraped from the dish and collected by centrifugation. The cells

were then resuspended in 100 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl,

150 mM NaCl, 10 mM iodoacetamide, 5 mM NaF, 5 mM sodium

pyrophosphate, 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, pH 7.5,

containing 2% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail),

incubated on ice for 15 min and centrifuged at 19,000 × g for 15

min at 4°C. The supernatant was mixed with sodium dodecyl

sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis sample buffer (26) and heated at 100°C for 5 min.

Proteins (10 μg of total protein/well) were then separated on 5–20%

polyacrylamide gels (SuperSep Ace; Wako, Osaka, Japan) and

transferred onto a polyvinyldifluoride membrane (Millipore Corp.,

Billerica, MA, USA). The membrane was blocked with 1% bovine serum

albumin (BSA) in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20 for 40 min at room

temperature and then incubated for 120 min with primary antibody

(anti-GLP-1R, 1:5,000 dilution, ab39072; anti-α-tubulin, 1:10,000

dilution, ab4074). The membranes were then washed 6 times for 5 min

each in buffer containing PBS and 0.1% Tween-20, followed by

incubation with a peroxidase-coupled secondary antibody (1:2,000

dilution; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). ECL Prime (GE Healthcare Life

Sciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) was used to detect peroxidase

activity. The optical densities of the bands were quantified using

ImageJ 1.47 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). GLP-1R expression

was normalized to α-tubulin expression, which was used as an

internal loading control.

Immunofluorescence

The MC3T3-E1 cells (3.2×104 cells/well)

were grown on a glass coverslip in 24-well plates for 72 h in

normal- (5.6 mM) or high-glucose (30 mM) medium with or without

BMP-2. Shortly before fixation, fresh medium containing 500 ng/ml

Hoechst 33342 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was

added followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were then

fixed with freshly prepared 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma). The fixed

cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 10 mM

glycine-PBS, blocked with 3% BSA in PBS at room temperature for 30

min and incubated with rabbit anti-GLP-1R antibody (1:1,000

dilution, ab39072) for 1 h. After several washes with 0.1% BSA in

PBS, the cells were incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibody

conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA)

for 1 h, washed again with 0.1% BSA in PBS and mounted in ProLong

Gold Antifade reagent (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR, USA). The

samples were observed under an All-in-One Fluorescence Microscope

(BZ-9000; Keyence, Osaka, Japan).

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay

The MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at

a density of 5×103 cells/100 μl/well. Following

incubation for 24, 48 or 72 h in normal- (5.6 mM) or high-glucose

(10, 20 or 30 mM) medium containing BMP-2, cell proliferation was

assessed using the MTT Cell Counting kit-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto,

Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. MTT solution

(10 μl) was added to each well and to the control wells without

cells. Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h, the amount of the MTT

formazan product was analyzed spectrophotometrically at a

wavelength of 450 nm. The absorbance was normalized to that of

cell-free medium.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS II for

Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical significance

of differences among groups was calculated using analysis of

variance. Data are presented as the means ± standard error of the

mean (SEM). P<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant and

P<0.01 as highly significant.

Results

Expression of incretin receptors in

MC3T3-E1 cells

The MC3T3-E1 cell line, the most widely studied

mouse osteoblastic cell line, was used in this study. We first

examined the mRNA expression of GLP-1R and GIPR in these cells by

RT-PCR with specific primers. Bands at 337 and 382 bp,

corresponding to GLP-1R and GIPR, respectively, were detected

(Fig. 1), indicating that these

osteoblasts expressed both types of incretin receptors.

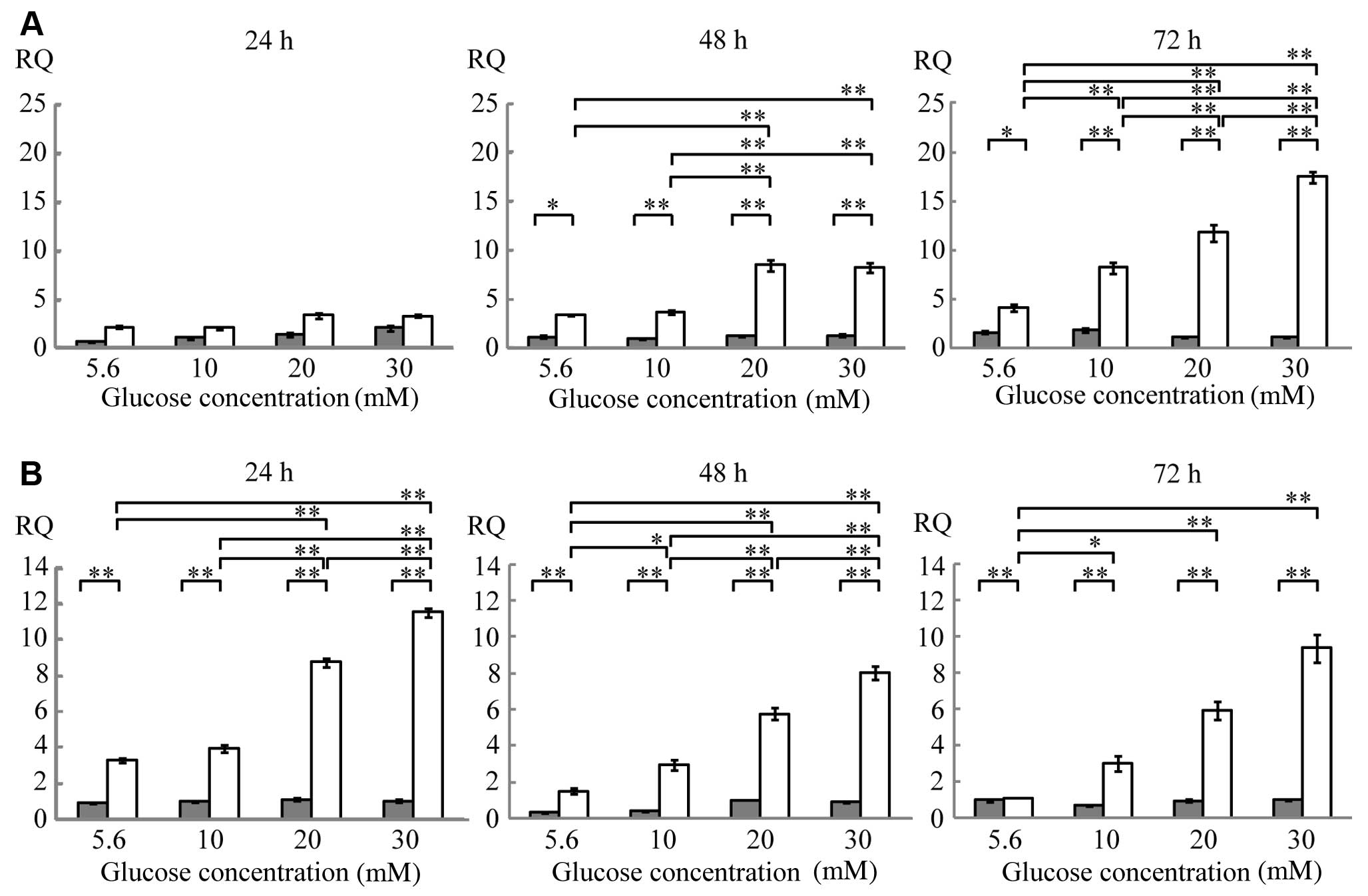

Quantitative PCR

The MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in medium

containing various glucose concentrations. The expression of GLP-1R

mRNA following 24 h of culture was unaffected by changes in glucose

concentrations either in the presence or absence of BMP-2. After 48

h of culture, GLP-1R mRNA expression increased in the presence of

BMP-2 compared with the absence of BMP-2 by 3-fold in the cells

cultured in 5.6 mM (normal) glucose, 4-fold in the cells cultured

in 10 mM glucose, and 6-fold in the cells cultured in 20 and 30 mM

glucose. After 72 h of culture, GLP-1R mRNA expression increased in

the presence of BMP-2 by 3-fold in the cells cultured in 5.6 mM

glucose, 4-fold in the cells cultured in 10 mM glucose, 11-fold in

the cells cultured in 20 mM glucose and 16-fold in the cells

cultured in 30 mM glucose (Fig.

2A and Table I). Notably, in

the presence of BMP-2, GLP-1R mRNA expression increased in response

to higher glucose concentrations. After 48 h of culture, GLP-1R

mRNA expression in the presence of BMP-2 in the cells cultured in

30 mM glucose was 2-fold higher than that in the cells cultured in

5.6 mM glucose. After 72 h of culture, GLP-1R mRNA expression in

the cells cultured in 30 mM glucose was 4-fold higher than that in

the cells cultured in 5.6 mM glucose (Fig. 2A and Table I). GLP-1R mRNA expression

increased in a time-dependent manner, since its expression after 72

h of culture in the cells cultured in 30 mM glucose in the presence

of BMP-2 was 5-fold higher than that after 24 h of culture

(Table I).

| Table IEffects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on GLP-1R mRNA expression. |

Table I

Effects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on GLP-1R mRNA expression.

| Glucose

concentration (mM) | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) |

|---|

| 5.6 | 0.82±0.08 | 2.25±0.18 | 1.16±0.17 | 3.40±0.05 | 1.62±0.15 | 4.17±0.36 |

| 10 | 1.14±0.15 | 2.21±0.15 | 0.90±0.09 | 3.67±0.25 | 1.90±0.23 | 8.23±0.56 |

| 20 | 1.52±0.25 | 3.45±0.28 | 1.29±0.09 | 8.46±0.51 | 1.11±0.07 | 11.79±0.84 |

| 30 | 2.16±0.27 | 3.38±0.16 | 1.31±0.13 | 8.22±0.49 | 1.10±0.04 | 17.49±0.55 |

GIPR mRNA expression was stimulated by BMP-2 at each

glucose concentration (Fig. 2B

and Table II). GIPR mRNA

expression increased in response to higher glucose concentrations

in the presence of BMP-2, being 4-fold higher in the cells cultured

in 30 mM glucose than in the cells cultured in 5.6 mM glucose after

24 h of culture (Fig. 2B and

Table II). After 48 and 72 h of

culture, GIPR mRNA expression in the cells cultured in 30 mM

glucose increased by 5- and 9-fold, respectively, compared with the

cells cultured in 5.6 mM glucose in the presence of BMP-2. However,

GIPR mRNA expression was not affected by the incubation time

(Table II).

| Table IIEffects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on GIPR mRNA expression. |

Table II

Effects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on GIPR mRNA expression.

| Glucose

concentration (mM) | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) |

|---|

| 5.6 | 0.91±0.05 | 3.29±0.12 | 0.28±0.03 | 1.50±0.14 | 0.96±0.11 | 1.09±0.03 |

| 10 | 0.97±0.05 | 3.95±0.20 | 0.43±0.04 | 2.94±0.26 | 0.68±0.06 | 2.98±0.40 |

| 20 | 1.09±0.10 | 8.76±0.26 | 1.01±0.03 | 5.78±0.32 | 0.94±0.09 | 5.94±0.50 |

| 30 | 1.00±0.10 | 11.54±0.28 | 0.86±0.05 | 8.04±0.35 | 1.00±0.05 | 9.33±0.74 |

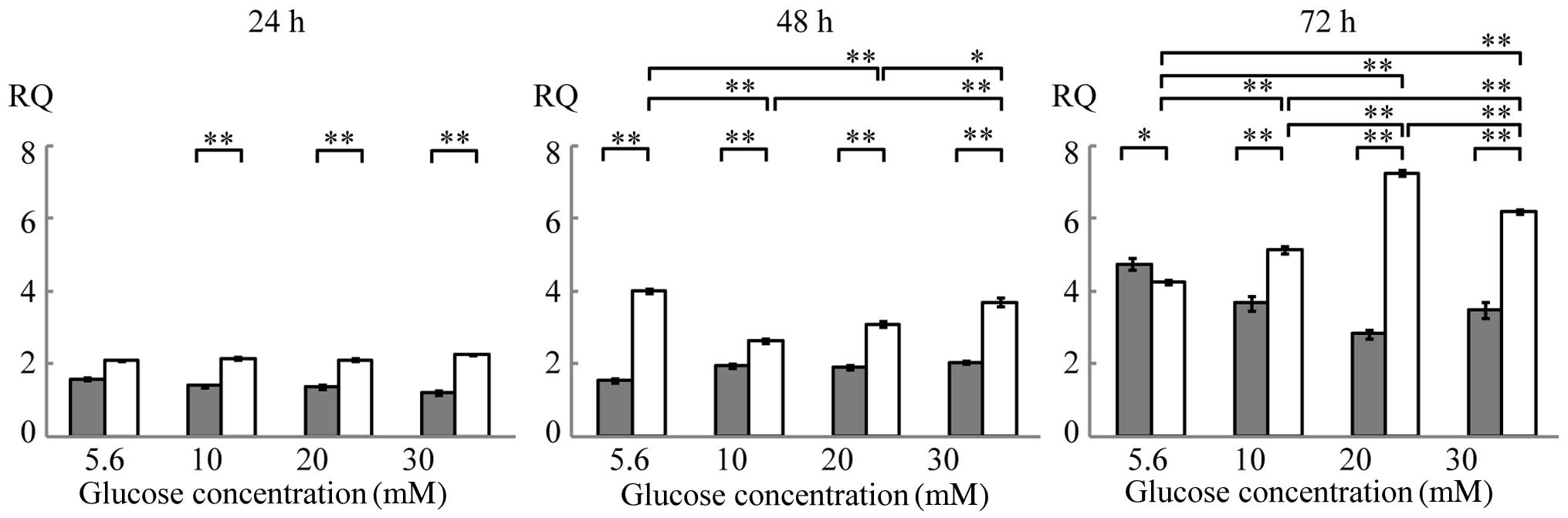

The expression of Runx2 mRNA increased in a time-

dependent manner in the presence of BMP-2. The glucose

concentration affected Runx2 mRNA expression after 48 and 72 h of

culture in the presence of BMP-2 (Fig. 3 and Table III). The expression of ALP mRNA

was below the limit of detection at all culture duration tests

(data not shown).

| Table IIIEffects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on Runx2 mRNA expression. |

Table III

Effects of glucose, BMP-2 and

incubation time on Runx2 mRNA expression.

| Glucose

concentration (mM) | 24 h | 48 h | 72 h |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) | BMP-2 (−) | BMP-2 (+) |

|---|

| 5.6 | 1.60±0.04 | 2.09±0.02 | 1.53±0.07 | 3.99±0.04 | 4.73±0.15 | 4.23±0.06 |

| 10 | 1.40±0.05 | 2.15±0.05 | 1.96±0.06 | 2.63±0.05 | 3.66±0.21 | 5.12±0.10 |

| 20 | 1.37±0.04 | 2.11±0.03 | 1.91±0.06 | 3.08±0.07 | 2.82±0.12 | 7.23±0.08 |

| 30 | 1.21±0.07 | 2.27±0.02 | 2.03±0.05 | 3.68±0.11 | 3.46±0.23 | 6.18±0.06 |

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed to determine the

protein expression levels of incretin receptors in MC3T3-E1 cells.

GLP-1R expression was determined in the total cell lysates using an

anti-GLP-1R antibody. GLP-1R expression appeared to be greater in

the cells cultured in 30 mM glucose with BMP-2 than in the cells

cultured in 5.6 mM glucose with or without BMP-2 (Fig. 4).

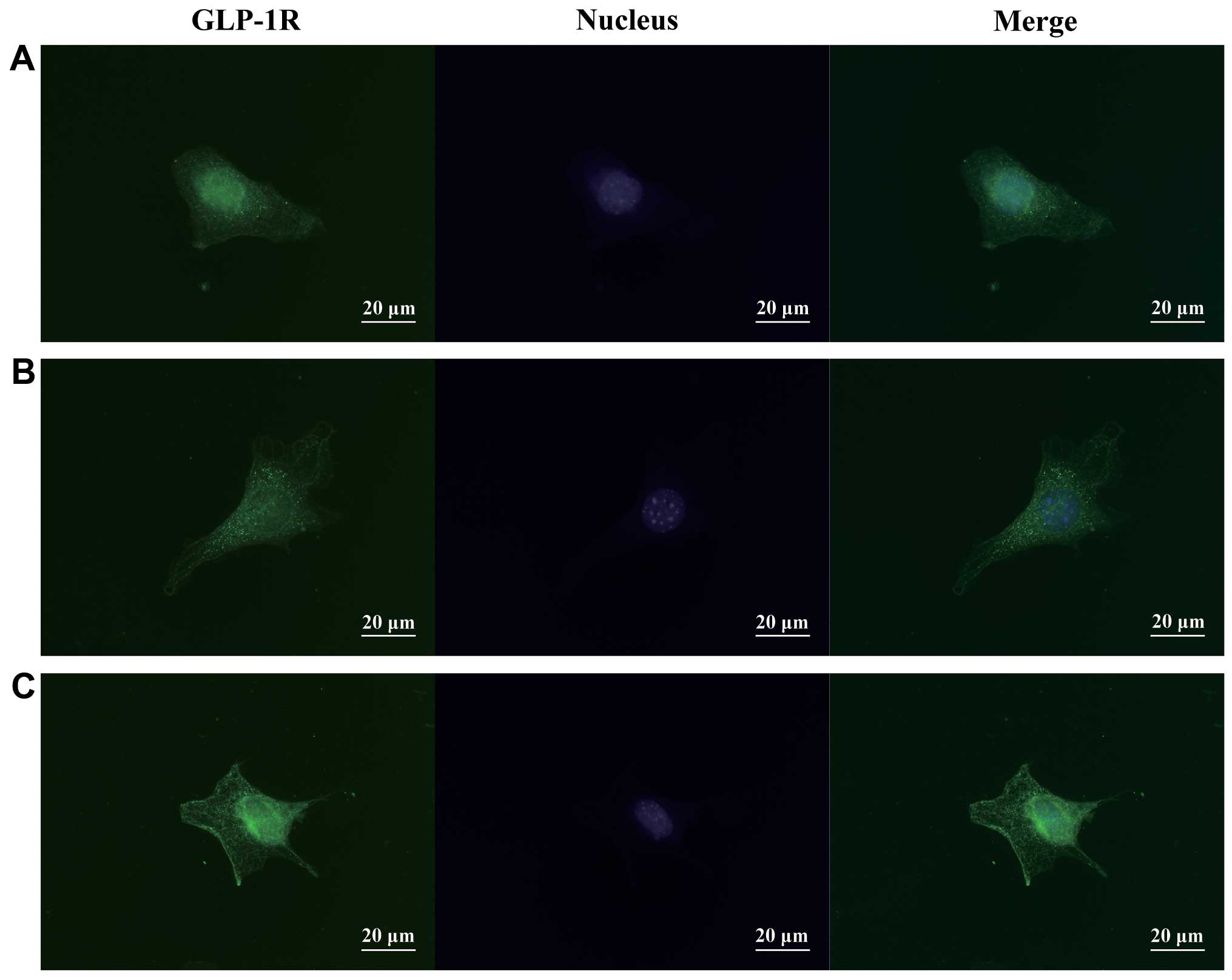

Immunofluorescence

Immunocytochemical analysis revealed a vesicular

staining pattern in the cytoplasm and cell surface, suggesting that

some cell compartments contained GLP-1R. The staining intensity was

slightly higher in the cells treated with 30 mM glucose in the

presence of BMP-2; however, the cellular distribution of GLP-1R was

not apparently affected by either glucose or BMP-2 (Fig. 5).

MTT assay

MTT assay revealed a time-dependent increase in the

number of cells in all groups analyzed. However, cell proliferation

was not affected by treatment with high glucose or BMP-2 (Fig. 6).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether

incretin receptors are expressed in osteoblasts and reveal the

correlation between glucose metabolism and bone metabolism.

Previous studies have demonstrated that GIPR is

expressed in osteoblastic cells (21); however, the presence of GLP-1R in

these cells still remains uncertain. Although osteoblastic cells

are thought to express a functional receptor for GLP-1 (27), there is no direct evidence to

confirm the mRNA and protein expression of GLP-1R in these cells.

It has been reported that GIP exerts direct effects on bone,

whereas the effects of GLP-1 on bone metabolism are mediated by the

thyroid hormone (20,28). Our RT-PCR analysis revealed that

the MC3T3-E1 cells expressed GLP-1R and GIPR, suggesting that GLP-1

may directly affect bone metabolism, similar to GIP.

In our study, at normal glucose concentrations (5.6

mM), the expression of both incretin receptors was very low and was

close to the lower limit of detection. However, treatment with 30

mM glucose increased the expression levels of GLP-1R and GIPR mRNA

by 4- and 9-fold, respectively. GLP-1R and GIPR knockout mice have

a higher risk of osteoporosis, suggesting that both receptors are

involved in bone metabolism (29). On the other hand, another study

revealed that treatment with a GLP-1R agonist may induce

polyarthritis in some patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

(30). Thus, it is possible that

the optimal effects of incretins may be achieved at moderate

expression levels.

The glucose concentration is known to regulate many

cellular events, including cell apoptosis, proliferation and

differentiation. For example, it has been reported that incubation

in high glucose concentrations stimulates the apoptosis of neurons,

retinal pericytes and endothelial cells (31–33). However, high glucose does not

affect the proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells (34). MTT assays in this study revealed

that treatment with high glucose did not affect the proliferation

of MC3T3-E1 cells, which suggests either that the proliferation of

osteoblasts is not affected by high glucose or that a longer

duration of exposure is necessary to influence proliferation

(35).

In our study, the expression of GLP-1R, but not

GIPR, increased in a time-dependent manner. Although both GLP-1R

and GIPR mediate insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells in

response to ligand binding, these receptors have the opposite

effects in other cell types. For example, GLP-1 has been shown to

inhibit glucagon secretion in pancreatic α cells in contrast to GIP

(36). Therefore, while GLP-1R

and GIPR are co-expressed in the same tissues, such as the

pancreas, they have different roles. Moreover, some tissues (e.g.,

kidneys and adipose tissue) express either GLP-1R or GIPR. Thus,

the different reactions of GLP-1R and GIPR to culture duration may

reflect the different roles of these receptors. Notably, glucose

metabolism seems to be altered after the loss of L cells, but is

not affected by the loss of K cells (37), which suggests that GLP-1 has a

greater effect on glucose metabolism than GIP.

BMP-2 stimulates bone formation and osteoblastic

differentiation. Runx2, an osteogenic master transcription factor,

is an important mediator of BMP-2 expression (38). Runx2 protein has been detected in

pre-osteoblasts, and its expression is upregulated in immature

osteoblasts, but downregulated in mature osteoblasts. Thus, the

MC3T3-E1 cells in this study were undergoing differentiation

induced by BMP-2.

GLP-1R and GIPR belong to the GPCR family, the

members of which are expressed in a variety of tissues and are

potential targets for drug discovery (39). It has been reported that the

administration of insulin and thiazolidinediones increases fracture

risk (40–42), whereas inhibitors of dipeptidyl

peptidase-4 (DPP-4) are associated with reduced fracture risk

(43). DPP-4 inactivates GLP-1

and its inhibitors improve glycemic control in patients with type 2

diabetes by preventing incretin degradation (44).

GLP-1 and GIP also reduce the expression of the

receptor of advanced glycation end products (AGE) in endothelial

and mesangial cells by increasing cAMP levels (45,46). Chronic hyperglycemia induces

non-enzymatic glycosylation and the transformation of various

proteins, particularly type I collagen, into AGE, leading to a

deterioration of bone mineralization and impaired biomechanical

properties of the skeleton. AGE can also affect bone metabolism by

inducing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as

tumor necrosis factor, which promote bone resorption and inhibit

osteoblastic activity and maturation (8).

In conclusion, in the present study, we confirmed

that MC3T3-E1 cells express both GLP-1R and GIPR. To the best of

our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that both

incretin receptors are expressed in the osteoblastic cell line. Our

results also suggest that GLP-1R expression is regulated by glucose

concentration, particularly in the presence of BMP-2, suggesting

that GLP-1R links bone metabolism and glucose metabolism in

osteoblasts, and that GLP-1 may have potential therapeutic

applications in bone diseases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Associate Professor Yoshiyuki

Sasaki for providing his statistical expertise, Associate Professor

Tatsuo Terashima and Associate Professor Miki Yokoyama for their

helpful comments during the preparation of this manuscript. This

study was financially supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific

Research (23792421, 25463169) from the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

References

|

1

|

Perry T and Greig NH: Enhancing central

nervous system endogenous GLP-1 receptor pathways for intervention

in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2:377–385.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lavin JH, Wittert GA, Andrews J, et al:

Interaction of insulin, glucagon-like peptide 1, gastric inhibitory

polypeptide, and appetite in response to intraduodenal

carbohydrate. Am J Clin Nutr. 68:591–598. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Nikolaidis LA, Elahi D, Hentosz T, et al:

Recombinant glucagon-like peptide-1 increases myocardial glucose

uptake and improves left ventricular performance in conscious dogs

with pacing-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation.

110:955–961. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dupre J, Behme MT, Hramiak IM, et al:

Glucagon-like peptide I reduces postprandial glycemic excursions in

IDDM. Diabetes. 44:626–630. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ding KH, Zhong Q, Xie D, et al: Effects of

glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide on behavior. Peptides.

27:2750–2755. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Miyawaki K, Yamada Y, Ban N, et al:

Inhibition of gastric inhibitory polypeptide signaling prevents

obesity. Nat Med. 8:738–742. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Gaudin-Audrain C, Irwin N, Mansur S, et

al: Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor

deficiency leads to modifications of trabecular bone volume and

quality in mice. Bone. 53:221–230. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ceccarelli E, Guarino EG, Merlotti D, et

al: Beyond glycemic control in diabetes mellitus: effects of

incretin-based therapies on bone metabolism. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 4:732013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hansotia T and Drucker DJ: GIP and GLP-1

as incretin hormones: lessons from single and double incretin

receptor knockout mice. Regul Pept. 128:125–134. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yip RG, Boylan MO, Kieffer TJ and Wolfe

MM: Functional GIP receptors are present on adipocytes.

Endocrinology. 139:4004–4007. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Seino Y, Fukushima M and Yabe D: GIP and

GLP-1, the two incretin hormones: similarities and differences. J

Diabetes Invest. 1:8–23. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ferron M, Wei J, Yoshizawa T, et al:

Insulin signaling in osteoblasts integrates bone remodeling and

energy metabolism. Cell. 142:296–308. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kamada A, Ikeo T, Yoshikawa Y, et al: Gene

expression of adipocytokine receptors during osteoblastic

differentiation. J Oral Tissue Eng. 7:53–60. 2009.

|

|

14

|

Huang CY, Lee CY, Chen MY, Tsai HC, Hsu HC

and Tang CH: Adiponectin increases BMP-2 expression in osteoblasts

via AdipoR receptor signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 224:475–483.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Prigeon RL, Quddusi S, Paty B and

D’Alessio DA: Suppression of glucose production by GLP-1

independent of islet hormones: a novel extrapancreatic effect. Am J

Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 285:E701–E707. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sancho V, Nuche B, Arnés L, et al: The

action of GLP-1 and exendins upon glucose transport in normal human

adipocytes, and on kinase activity as compared to morbidly obese

patients. Int J Mol Med. 19:961–966. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Vella A, Shah P, Reed AS, Adkins AS, Basu

R and Rizza RA: Lack of effect of exendin-4 and glucagon-like

peptide-1-(7,36)-amide on insulin action in non-diabetic humans.

Diabetologia. 45:1410–1415. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Egan JM, Meneilly GS, Habener JF and Elahi

D: Glucagon-like peptide-1 augments insulin-mediated glucose uptake

in the obese state. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 87:3768–3773. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Nuche-Berenguer B, Moreno P, Esbrit P, et

al: Effect of GLP-1 treatment on bone turnover in normal, type 2

diabetic, and insulin-resistant states. Calcif Tissue Int.

84:453–461. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yamada C, Yamada Y, Tsukiyama K, et al:

The murine glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor is essential for

control of bone resorption. Endocrinology. 149:574–579. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Bollag RJ, Zhong Q, Phillips P, et al:

Osteoblast-derived cells express functional glucose-dependent

insulinotropic peptide receptors. Endocrinology. 141:1228–1235.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhong Q, Itokawa T, Sridhar S, et al:

Effects of glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide on osteoclast

function. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 292:E543–E548. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Xie D, Cheng H, Hamrick M, et al:

Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor knockout mice

have altered bone turnover. Bone. 37:759–769. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Mieczkowska A, Irwin N, Flatt PR, Chappard

D and Mabilleau G: Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide

(GIP) receptor deletion leads to reduced bone strength and quality.

Bone. 56:337–342. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Noguchi H, Oishi K, Ueda M, et al:

Establishment of mouse pancreatic stem cell line. Cell Transplant.

18:563–571. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Laemmli UK: Cleavage of structural

proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4.

Nature. 227:680–685. 1970. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nuche-Berenguer B, Portal-Núñez S, Moreno

P, et al: Presence of a functional receptor for GLP-1 in

osteoblastic cells, independent of the cAMP-linked GLP-1 receptor.

J Cell Physiol. 225:585–592. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lamari Y, Boissard C, Moukhtar MS,

Jullienne A, Rosselin G and Garel JM: Expression of glucagon-like

peptide 1 receptor in a murine C cell line: regulation of

calcitonin gene by glucagon-like peptide 1. FEBS Lett. 393:248–252.

1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Tsukiyama K, Yamada Y, Yamada C, et al:

Gastric inhibitory polypeptide as an endogenous factor promoting

new bone formation after food ingestion. Mol Endocrinol.

20:1644–1651. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Ambrosio ML, Monami M, Sati L, Marchionni

N, Di Bari M and Mannucci E: GLP-1 receptor agonist-induced

polyarthritis: a case report. Acta Diabetol. Oct 25–2013.(Epub

ahead of print).

|

|

31

|

Russell JW, Sullivan KA, Windebank AJ,

Herrmann DN and Feldman EL: Neurons undergo apoptosis in animal and

cell culture models of diabetes. Neurobiol Dis. 6:347–363. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Romeo G, Liu WH, Asnaghi V, Kern TS and

Lorenzi M: Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB induced by diabetes

and high glucose regulates a proapoptotic program in retinal

pericytes. Diabetes. 51:2241–2248. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Piconi L, Quagliaro L, Assaloni R, et al:

Constant and intermittent high glucose enhances endothelial cell

apoptosis through mitochondrial superoxide overproduction. Diabetes

Metab Res Rev. 22:198–203. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Weil BR, Abarbanell AM, Herrmann JL, Wang

Y and Meldrum DR: High glucose concentration in cell culture medium

does not acutely affect human mesenchymal stem cell growth factor

production or proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp

Physiol. 296:R1735–R1743. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Balint E, Szabo P, Marshall CF and Sprague

SM: Glucose-induced inhibition of in vitro bone mineralization.

Bone. 28:21–28. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Yabe D and Seino Y: Two incretin hormones

GLP-1 and GIP: comparison of their actions in insulin secretion and

β cell preservation. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 107:248–256. 2011.

|

|

37

|

Pedersen J, Ugleholdt RK, Jørgensen SM, et

al: Glucose metabolism is altered after loss of L cells and

alpha-cells but not influenced by loss of K cells. Am J Physiol

Endocrinol Metab. 304:E60–E73. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Choi KY, Kim HJ, Lee MH, et al: Runx2

regulates FGF2-induced Bmp2 expression during cranial bone

development. Dev Dyn. 233:115–121. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Gigoux V and Fourmy D: Acting on hormone

receptors with minimal side effect on cell proliferation: A timely

challenge illustrated with GLP-1R and GPER. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 4:502013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Monami M, Cresci B, Colombini A, et al:

Bone fractures and hypoglycemic treatment in type 2 diabetic

patients: a case-control study. Diabetes Care. 31:199–203. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Meier C, Kraenzlin ME, Bodmer M, Jick SS,

Jick H and Meier CR: Use of thiazolidinediones and fracture risk.

Arch Intern Med. 168:820–825. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Bazelier MT, Gallagher AM, van Staa TP, et

al: Use of thiazolidinediones and risk of osteoporotic fracture:

disease or drugs? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 21:507–514. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Monami M, Dicembrini I, Antenore A and

Mannucci E: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and bone fractures: a

meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Care.

34:2474–2476. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Drucker DJ and Nauck MA: The incretin

system: glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and dipeptidase-4

inhibitors in type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 368:1696–1705. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Tahara N, Yamagishi S, Takeuchi M, et al:

Serum levels of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are

independently correlated with circulating levels of dipeptidyl

peptidase-4 (DPP-4) in humans. Clin Biochem. 46:300–303. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Yamagishi S and Matsui T: Pleiotropic

effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1)-based therapies on

vascular complications in diabetes. Curr Pharm Des. 17:4379–4385.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|