Introduction

Obesity is the most common metabolic disease in

developed nations and has become a global epidemic in recent years

(1). Furthermore, obesity is

associated with a variety of chronic diseases, including glucose

intolerance, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and hypertension. A

combination of these abnormalities is now referred to as the

metabolic syndrome (2). An

increase in fat mass is a result of an increase in adipocyte number

and size. Cellular and molecular studies focusing on the

development of obesity have shown that changes in the number of

adipocytes (hyperplasia) and adipocyte size (hypertrophy) can be

triggered by dietary factors (3,4).

The findings of a previous study indicated that an increased

adipocyte number during the aging process may contribute to the

increase in the incidence and severity of obesity observed in older

individuals (5). Thus,

hyperplasia of adipocytes may be an important factor in the

development of obesity.

Adipocytes are derived from mesenchymal stem cells,

which have the potential to differentiate into myoblasts,

chondroblasts, osteoblasts or adipocytes (6). Adipocyte differentiation involves an

elaborate network of transcription factors that regulate the

expression of numerous genes responsible for the phenotype of

mature adipocytes (7). Among the

various transcription factors that promote preadipocyte

differentiation and influence adipogenesis, peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) is considered the ‘master

regulator of adipogenesis’ (8–10).

Other adipogenic transcription factors include the CCAAT/enhancer

binding proteins (C/EBPα, C/EBPβ and C/EBPγ) (5,7,11).

These factors are necessary for the expression of

adipocyte-specific genes (adiponectin) (12). These transcription factors,

especially PPARγ and C/EBPα are regulated by the mitogen-activated

protein kinase (MAPK) pathway during adipogenesis (13–15).

Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) is a member of an

important group of signaling sphingolipids now recognized to play a

role in a diverse array of cell processes, such as apoptosis, cell

motility, differentiation, and proliferation in a variety of cell

types including endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and

macrophages (16,17). S1P is generated by the

phosphorylation of the sphingosine mediated by sphingosine

kinases-1 (Sphk-1) and Sphk-2 (18). S1P exerts most of its activity as

a ligand of G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (19). At present, five members of the S1P

receptor family have been identified in mammals, notably S1P1-5,

possessing distinct expression profiles and affinities towards S1P

(20,21).

S1P regulates the differentiation via MAPK pathways

in a variety of cell types including osteoclasts, monocytes,

placental trophoblasts, myoblasts and vascular smooth muscle cells

(16,19,22–24). In addition, a number of studies

have shown that S1P and sphingosine kinases have multifunctional

characteristics, including a correlation with weight gain in breast

cancer patients, a sensitivity to acute myeloid leukemia cells, a

chemotherapy sensor in prostate cancer and enhancing sensitivity to

hormone-resistant prostate cancer (25–28). ERK, p38 and JNK MAPKs are

intracellular signaling pathways that play a pivotal role in

numerous essential cell processes such as proliferation and

differentiation (3,13,24). Chemotherapy induces the

downregulation of S1P by inhibiting Sphk and this decrease of

circulating S1P by chemotherapy may switch S1P-mediated adipose

cell stasis to adipogenesis.

In the present study, we investigated whether S1P

inhibited adipocyte differentiation and regulated MAPK pathways

including ERK, p38 and JNK MAPKs. S1P was found to exert novel and

physiologically important biological effects on preadipocytes,

acting as an anti-differentiation agent.

Materials and methods

Reagents

S1P was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor,

MI, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). S1P was prepared

as a 2 mM solution in 0.3 M NaOH or methanol or 125 μM solution in

fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin, subsequently diluted in cell

culture medium.

Cell culture and differentiation

3T3-L1 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified

Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% calf serum and antibiotics

(100 μg/ml gentamycin and 100 μg/ml penicillin-streptomycin). To

induce differentiation, 2-day post confluent 3T3-L1 cells were

incubated in MDI induction media [DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine

serum, 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), 1 μm

dexamethasone and 1 μg/ml of insulin] for 2 days. In some

experiments, S1P (10 μM) was added at the time of the induction of

differentiation. The AdipoRed Assay and detection of glycerol

release contents were performed on day 7.

Quantification of lipid content

Lipid content was quantified using the commercially

available AdipoRed assay reagent (Lonza, Verviers, Belgium)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief,

preadipocytes grown in 24-well plates were incubated with MDI

medium or with the test compounds during the adipogenic phase and

on day 6, the culture supernatant was removed and carefully washed

with 500 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The wells were

subsequently filled with 300 μl PBS and 30 μl of AdipoRed reagent

were added followed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C. The AdipoRed

of the cells was photographed using a light microscope and

fluorescence was measured with an excitation at 485 nm and an

emission at 572 nm.

Adipolysis assay

Glycerol release was measured using a commercially

available Adipolysis assay kit (Cayman Chemical) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the differentiated adipocytes

in a 96-well plate were stimulated with S1P or isoproterenol

solution used as a positive control for 24 h. After stimulation,

the cell culture supernatants were collected from each well and

stored until use at −20°C. A total of 100 μl of free glycerol assay

reagent was added to 25 μl of each supernatant. Following

incubation for 15 min at room temperature, the absorbance was

measured at 540 nm.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from 3T3-L1 cells treated

with S1P using the Easy-spin™ total RNA extraction kit (Intron

Biotechnology, Seoul, Korea). cDNA synthesis was carried out

following the instructions of the Takara PrimeScript™ 1st Strand

cDNA synthesis kit (Takara Bio, Tokyo, Japan). For the RT-qPCR, 1

μl of gene primers with SYBR-Green (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules,

CA, USA) in 20 μl of reaction volume was applied. The primer

sequences used for qPCR were: PPARγ (forward, 5′-CGGAAGCCCTTTGG

TGACTTTATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCAGCAGGTTGTCTT GGATGTC-3′), C/EBP-α

(forward, 5′-CGGGAACGCAAC AACATCGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TGTCCAGTTCACGGCT CAGC-3′), adiponectin (forward,

5′-TGACGGCAGCACT GGCAAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGATACTGGTCGTAGGTGAA

GAGAAC-3′) β-actin (forward, 5′-TGAGAGGGAAATCG TGCGTGAC-3′ and

reverse, 5′-GCTCGTTGCCAATAGTGA TGACC-3′). All reactions with iTaq

SYBR-Green Supermix were performed on the CFX96 real-time PCR

detection system (both from Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Western blot analysis

The 3T3-L1 cells were lysed in a lysis buffer (25 mM

HEPES; pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1

mM dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitor mixture). Proteins were

electrophoretically resolved on an 8–15% sodium dodecyl sulfate

(SDS) gel, and immunoblotting was performed as previously described

(29). Images were captured using

the Fusion FX7 acquisition system (Vilber Lourmat, Eberhardzell,

Germany). Densitometry of the signal bands was analyzed using

Bio-1D (Vilber Lourmat) (30).

The antibodies used for immunoblotting were PPARγ (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), p-JNK and p-p38 (both

from Cell Signaling Technology Beverly, MA, USA) and β-actin

(Sigma-Aldrich).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of

the mean (SEM). Data were compared using the Student’s t-test,

analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Duncan test with the SAS

statistical package. The results were considered significant for

values of P<0.05 or P<0.01.

Results

S1P inhibits adipocyte differentiation of

3T3-L1 cells

Since S1P regulates the differentiation of various

cell types, the effect of S1P on adipocyte differentiation of the

3T3-L1 cells was investigated. Preadipocytes grown in 24-well

plates were incubated with MDI media with or without S1P during the

adipogenic differentiation phase. When 3T3-L1 cells differentiated

over 6 days in the presence of various concentrations of S1P in the

adipogenic medium, a reduction in lipid accumulation was observed

(Fig. 1A and B). The inhibition

effect of S1P was significantly detected at 0.5 μM and was maximal

at 50 μM. To confirm inhibition of triglyceride accumulation of

S1P, we measured the triglycerides directly in 3T3-L1 cells

differentiated over 6 days that were treated with S1P. S1P

treatment also inhibited triglyceride accumulation during the

differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (Fig. 1C). To study the effect of S1P on

lipolysis, the differentiated adipocytes were incubated with

various concentrations of S1P for 24 h, and the glycerol level was

determined in the medium. However, S1P did not affect glycerol

release, marked to lipolysis of differentiated adipocytes (Fig. 1D), indicating that S1P inhibited

lipid accumulation by blocking adipogenic differentiation, not by

lipolysis of differentiated adipocytes.

We investigated whether the inhibition effects of

S1P are maintained in various dissolving solutions of S1P,

including fatty acid-free albumin and methyl alcohol. We tested the

adipogenic differentiation, lipid contents and glycerol release

assay using S1P dissolved in methyl alcohol (MeOH) and fatty

acid-free albumin stock solution in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes (Fig. 2). S1P dissolved in MeOH and in

fatty acid-free albumin inhibited lipid accumulation but did not

affect the glycerol release. The results demonstrated that S1P

inhibited lipid accumulation by inhibiting adipogenic

differentiation without regulating the lipolysis of adipocyte in

3T3-L1 cells.

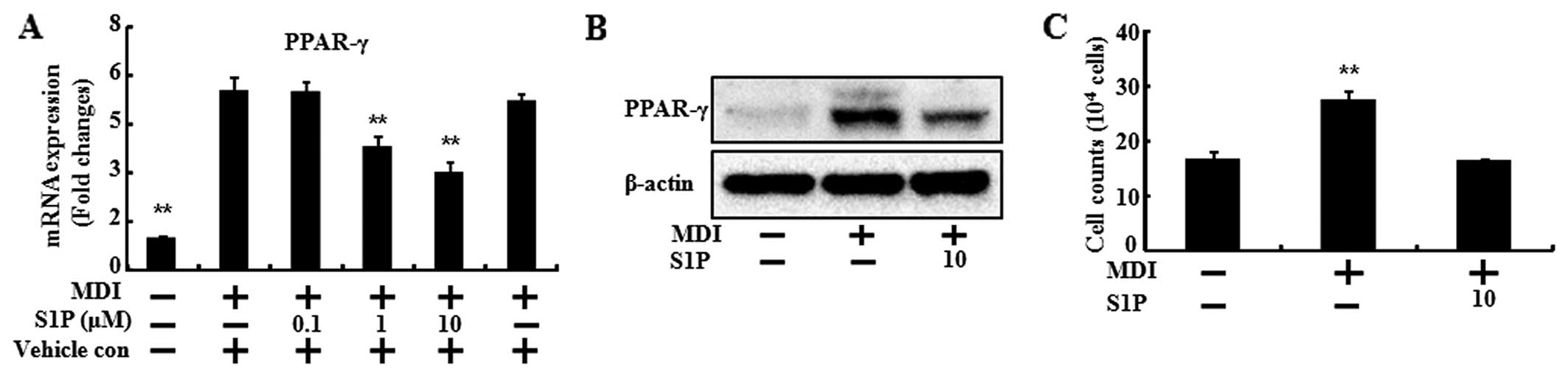

S1P downregulates the transcriptional

factor, PPARγ, involved in adipocyte differentiation

To confirm the inhibitory effects of SIP on

adipogenic differentiation, the mRNA levels of biochemical markers

of differentiation (PPARγ, C/EBPα and adiponectin) were determined

(Figs. 3 and 4). When the 3T3-L1 preadipocytes

differentiated with MDI treatment, the mRNA levels of the

biochemical markers of differentiation increased compared to the

control. However, S1P treatment led to a significant reduction by

increasing the dose of S1P in the mRNA level of PPARγ, C/EBPα and

adiponectin (Figs. 3A, 4A and 4B). In the case of PPARγ, the

protein expression was also decreased by S1P (Fig. 3B).

S1P is interconvertible with ceramide and it is a

critical mediator of apoptosis. Therefore, we investigated the cell

number of 3T3-L1 cells during the differentiation in the presence

of 10 μM of S1P. At 24 h after MDI induction, mitosis occurred,

thus the cell numbers were doubled (31). Consistent with results of that

study, in the present study, the cell numbers of the MDI induction

were doubled in the control and those of the S1P treatment were

similar to the control (Fig. 3C).

These results demonstrated that S1P exhibits anti-adipogenic

activity through downregulation of the transcription factors

involved in adipocyte differentiation.

S1P mediates its action on MAPK pathways

via the S1P2 receptor subtype

It is well known that preadipocyte differentiation

involves the activation of several key signaling pathways such as

JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK (13). To

gain insight into the molecular mechanisms responsible for the

observed biological effects of S1P, the ability of the sphingolipid

to inactivate these protein kinases was examined. The MDI

containing adipocyte differentiation cocktail induced the

phosphorylation of JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK, at 12, 6 and 3 h,

respectively, after MDI addition (Fig. 4C). However, 10 μM of S1P decreased

the phosphorylation of JNK1/2 and p38 MAPK at 12 h after the

addition of MDI. Taken together, these results showed that S1P

inhibited the adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation, and

the inhibition effects were mediated by the downregulation of

transcription factors and by inactivation of the MAPK signals.

Discussion

Excessive adipose tissue accumulation is a key

factor leading to insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes,

hyperlipidemia and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Obesity is no longer considered to be only a cosmetic problem, but

is associated with an increased risk for the development of

numerous adverse health conditions (1,6).

The recruitment of new fat cells in adipose tissue requires the

differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes (adipogenesis), a

process closely controlled by the transcription factors PPARγ and

C/EBPα (32,33).

Studies on the effects of S1P on cell

differentiation are available. S1P acts as a regulator of

osteoclast differentiation (22)

as well as myogenic differentiation (24,34). S1P and the S1P1 receptor are

associated with angiogenic differentiation of vascular endothelial

cells (35). Although S1P has

been demonstrated to promote the differentiation of endothelial

cells and myocytes, the ability of S1P to affect cell

differentiation appears to be dependent on the cell type. In

placental trophoblasts and human monocytes, S1P shows

anti-differentiating effects. S1P inhibits the differentiation of

cytotrophoblasts into syncytiotrophoblasts through a G(i)-coupled

S1P receptor interaction (16).

In addition, S1P interferes with the differentiation of human

monocytes into competent dendritic cells (23). Results of previous studies are in

concordance with our results showing that S1P inhibits the

differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes in 3T3-L1 cells

(Figs. 1 and 2).

S1P levels inside cells are closely regulated by the

balance between its synthesis by sphingosine kinases and

degradation. S1P is interconvertible with ceramide, which is a

critical mediator of apoptosis. In the present study, a high dose

of S1P was utilized to determine the anti-adipogenic effect of S1P.

To verify whether the high dose of S1P can be converted to ceramide

and can equally activate the S1P receptors, further experiments are

required in future studies. The ceramide itself served as an

important second messenger in various stress responses and growth

mechanisms (36). While S1P

functions mainly via GPCR, ceramide and its metabolite appears to

bind directly to targets (36).

The p38 and JNK MAPKs are intracellular signaling

pathways that play a pivotal role in numerous essential cell

processes such as proliferation and differentiation (3,13,

24). MAPKs are activated by a

large variety of stimuli and one of their major functions is to

connect cell surface receptors to transcription factors in the

nucleus, which consequently triggers long-term cell responses

(13). Previously, it was

established that, the MAPK signaling pathway regulates the

expression of PPARγ and C/EBPα during adipogenesis in preadipocytes

(37). A well-known stimulus that

affects the MAPK signaling pathways is S1P. The results of this

study have shown that S1P inhibited MDI-induced phosphorylation of

p38 and JNK1/2 (Fig. 4C).

When induced to differentiate, growth-arrested

3T3-L1 preadipocytes synchronously re-enter the cell cycle and

undergo mitotic clonal expansion (MCE). MCE is a prerequisite for

the differentiation of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes into adipocytes

(31). Consistent with that

study, our results show that the number of cells at 24 h after MDI

induction was increased whereas the addition of S1P significantly

decreased cell populations (Fig.

3C). The results suggest that S1P inhibited the first round of

mitosis, thereby preventing the expression of adipogenic regulator

genes.

In conclusion, the results of this study have shown

that exposure of preadipocytes to S1P inhibited their

differentiation into adipocytes, as confirmed by a reduction in

triglyceride accumulation and a reduction in the expression of

adipocyte specific genes. Therefore, S1P functioned as an

anti-adipogenic compound. The results also suggest that the

adipogenic transcription factors and various MAPK pathways are a

potential therapeutic target for obesity.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the

National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Korean

government (2013R1A1A2063931).

References

|

1

|

Lei F, Zhang XN, Wang W, et al: Evidence

of anti-obesity effects of the pomegranate leaf extract in high-fat

diet induced obese mice. Int J Obes (Lond). 31:1023–1029. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Boyle KB, Hadaschik D, Virtue S, et al:

The transcription factors Egr1 and Egr2 have opposing influences on

adipocyte differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 16:782–789. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim KJ, Lee OH and Lee BY: Fucoidan, a

sulfated polysaccharide, inhibits adipogenesis through the

mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes.

Life Sci. 86:791–797. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gregoire FM, Smas CM and Sul HS:

Understanding adipocyte differentiation. Physiol Rev. 78:783–809.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yanagiya T, Tanabe A and Hotta K:

Gap-junctional communication is required for mitotic clonal

expansion during adipogenesis. Obesity (Silver Spring). 15:572–582.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rayalam S, Della-Fera MA and Baile CA:

Phytochemicals and regulation of the adipocyte life cycle. J Nutr

Biochem. 19:717–726. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lee H, Lee YJ, Choi H, Ko EH and Kim JW:

Reactive oxygen species facilitate adipocyte differentiation by

accelerating mitotic clonal expansion. J Biol Chem.

284:10601–10609. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Wakabayashi K, Okamura M, Tsutsumi S, et

al: The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma/retinoid X

receptor alpha heterodimer targets the histone modification enzyme

PR-Set7/Setd8 gene and regulates adipogenesis through a positive

feedback loop. Mol Cell Biol. 29:3544–3555. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tontonoz P and Spiegelman BM: Fat and

beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem.

77:289–312. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rosen ED and MacDougald OA: Adipocyte

differentiation from the inside out. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

7:885–896. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nerurkar PV, Lee YK and Nerurkar VR:

Momordica charantia (bitter melon) inhibits primary human adipocyte

differentiation by modulating adipogenic genes. BMC Complement

Altern Med. 10:342010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Xing Y, Yan F, Liu Y and Zhao Y: Matrine

inhibits 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation associated with

suppression of ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

396:691–695. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bost F, Aouadi M, Caron L and Binétruy B:

The role of MAPKs in adipocyte differentiation and obesity.

Biochimie. 87:51–56. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Alonso-Vale MI, Peres SB, Vernochet C,

Farmer SR and Lima FB: Adipocyte differentiation is inhibited by

melatonin through the regulation of C/EBPbeta transcriptional

activity. J Pineal Res. 47:221–227. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Chen TH, Chen WM, Hsu KH, Kuo CD and Hung

SC: Sodium butyrate activates ERK to regulate differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 355:913–918.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Johnstone ED, Chan G, Sibley CP, Davidge

ST, Lowen B and Guilbert LJ: Sphingosine-1-phosphate inhibition of

placental trophoblast differentiation through a G(i)-coupled

receptor response. J Lipid Res. 46:1833–1839. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Goetzl EJ, Wang W, McGiffert C, Liao JJ

and Huang MC: Sphingosine 1-phosphate as an intracellular messenger

and extracellular mediator in immunity. Acta Paediatr Suppl.

96:49–52. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

He X, H’ng SC, Leong DT, Hutmacher DW and

Melendez AJ: Sphingosine-1-phosphate mediates proliferation

maintaining the multipotency of human adult bone marrow and adipose

tissue-derived stem cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2:199–208. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Schüppel M, Kürschner U, Kleuser U,

Schäfer-Korting M and Kleuser B: Sphingosine 1-phosphate restrains

insulin-mediated keratinocyte proliferation via inhibition of Akt

through the S1P2 receptor subtype. J Invest Dermatol.

128:1747–1756. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Bieberich E: There is more to a lipid than

just being a fat: sphingolipid-guided differentiation of

oligodendroglial lineage from embryonic stem cells. Neurochem Res.

36:1601–1611. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Pyne S and Pyne NJ: Sphingosine

1-phosphate signalling in mammalian cells. Biochem J. 349:385–402.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ryu J, Kim HJ, Chang EJ, Huang H, Banno Y

and Kim HH: Sphingosine 1-phosphate as a regulator of osteoclast

differentiation and osteoclast-osteoblast coupling. EMBO J.

25:5840–5851. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Martino A, Volpe E, Auricchio G, et al:

Sphingosine 1-phosphate interferes on the differentiation of human

monocytes into competent dendritic cells. Scand J Immunol.

65:84–91. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Donati C, Meacci E, Nuti F, Becciolini L,

Farnararo M and Bruni P: Sphingosine 1-phosphate regulates myogenic

differentiation: a major role for S1P2 receptor. FASEB J.

19:449–451. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pchejetski D, Nunes J, Sauer L, et al:

Circulating sphingosine-1- phosphate inversely correlates with

chemotherapy-induced weight gain during early breast cancer. Breast

Cancer Res Treat. 124:543–549. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bonhoure E, Pchejetski D, Aouali N, et al:

Overcoming MDR-associated chemoresistance in HL-60 acute myeloid

leukemia cells by targeting sphingosine kinase-1. Leukemia.

20:95–102. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Pchejetski D, Golzio M, Bonhoure E, et al:

Sphingosine kinase-1 as a chemotherapy sensor in prostate

adenocarcinoma cell and mouse models. Cancer Res. 65:11667–11675.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sauer L, Nunes J, Salunkhe V, et al:

Sphingosine kinase 1 inhibition sensitizes hormone-resistant

prostate cancer to docetaxel. Int J Cancer. 125:2728–2736. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Moon MH, Jeong JK, Seo JS, et al:

Bisphosphonate enhances TRAIL sensitivity to human osteosarcoma

cells via death receptor 5 upregulation. Exp Mol Med. 43:138–145.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Seo JS, Moon MH, Jeong JK, et al: SIRT1, a

histone deacetylase, regulates prion protein-induced neuronal cell

death. Neurobiol Aging. 33:1110–1120. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tang QQ, Otto TC and Lane MD: Mitotic

clonal expansion: a synchronous process required for adipogenesis.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100:44–49. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Simon MF, Daviaud D, Pradère JP, et al:

Lysophosphatidic acid inhibits adipocyte differentiation via

lysophosphatidic acid 1 receptor-dependent down-regulation of

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma2. J Biol Chem.

280:14656–14662. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fu L, Tang T, Miao Y, Zhang S, Qu Z and

Dai K: Stimulation of osteogenic differentiation and inhibition of

adipogenic differentiation in bone marrow stromal cells by

alendronate via ERK and JNK activation. Bone. 43:40–47. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Meacci E, Cencetti F, Donati C, et al:

Down-regulation of EDG5/S1P2 during myogenic differentiation

results in the specific uncoupling of sphingosine 1-phosphate

signalling to phospholipase D. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1633:133–142.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu Y, Wada R, Yamashita T, et al: Edg-1,

the G protein-coupled receptor for sphingosine-1-phosphate, is

essential for vascular maturation. J Clin Invest. 106:951–961.

2000. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chalfant CE and Spiegel S: Sphingosine

1-phosphate and ceramide 1-phosphate: expanding roles in cell

signaling. J Cell Sci. 118:4605–4612. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Prusty D, Park BH, Davis KE and Farmer SR:

Activation of MEK/ERK signaling promotes adipogenesis by enhancing

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma ) and

C/EBPalpha gene expression during the differentiation of 3T3-L1

preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 277:46226–46232. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|