Introduction

The control of host-microbe homeostasis in the

mucosal epithelium is essential for preventing

microorganism-triggered inflammatory diseases. A number of common

pathogenic bacteria are able to invade epithelial cells. Intestinal

pathogens, such as Salmonella, Shigella,

Yersinia and Escherichia coli are able to invade

intestinal epithelial cells (1).

Respiratory pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(2), Haemophilus

influenzae (3),

Streptococcus pneumonia (4) and Klebsiella pneumoniae

(5) can enter airway epithelial

cells. Uropathogens, such as Escherichia coli and

Klebsiella pneumoniae (6)

and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (7) invade the host urothelium. Studies

have demonstrated that some host cells have the ability to remove

intracellular bacteria (8,9).

We discovered that Klebsiella pneumoniae is capable of

invading human T24 cells and that these cells, in turn, are capable

of eliminating the infection.

Innate immunity plays an important role in the

removal of invasive intracellular bacteria from epithelial cells.

As regards invertebrates, the Drosophila melanogaster

intestinal immune response relies mainly on 2 types of

complementary and synergistic molecular effectors that restrict the

proliferation of microorganisms: antimicrobial peptides and

reactive oxygen species (ROS) (10). Oxidative defense mechanisms

involving ROS play important roles in innate immunity (11). ROS mainly derive from

mitochondrial metabolism or from regulated nicotinamide adenine

dinucleotide phosphate-oxidase (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) activity

(12). The NOX family includes

NOX1-5, dual oxidase (DUOX)1 and DUOX2 (13), all of which function as components

of the mucosal immune response (14). In fact, the T helper (Th)1 and Th2

cytokines promote host defense and pro-inflammatory responses by

regulating the expression of DUOX1 and DUOX2 in human airways

(11). Moreover, as previously

demonstrated, DUOX2/dual oxidase maturation factor 2 (DUOXA2)

co-transfected human thyroid cells treated with phorbol

12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) exhibit increased

H2O2 generation, which is associated with

PMA-mediated DUOX2 phosphorylation (15).

ROS generation is necessary to initiate an innate

immune response in normal human nasal epithelial cells (16), and this response mediates

epithelial cell H2O2 production to counteract

the replication of the respiratory syncytial virus (17) and influenza A virus (18) and prevent gastric Helicobacter

felis colonization and the inflammatory response (10). DUOX2 activity is a possible source

of ROS in all of these immune responses. Additionally, in the

Listeria monocytogenes infection model, the simultaneous

overexpression of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

containing 2 (NOD2) and DUOX2 was found to result in cooperative

protection against bacterial cytoinvasion (19). Therefore, as the main NOX, DUOX2

plays a major role in host defense in epithelial cells, including

airway and intestinal epithelial cells, and acts as a host defense

mechanism in phagocytes through the generation of ROS.

Klebsiella pneumonae is a common uropathogen

found in diabetic patients and hospital settings and comprises up

to 5% of urinary tract infections (20,21). While the antimicrobial substances

in urine (such as urea) and the mucin of urinary tract mucosal

surfaces provide a physiochemical barrier, intrinsic antibacterial

activity may play an important role in maintaining bladder

sterility.

Although the activation of DUOX1 has been shown to

protect mouse urothelial cells from pathogens through the

production of H2O2 (22), to the best of our knowledge, DUOX2

expression in bladder cancer epithelial cells has not been reported

to date. Furthermore, whether Klebsiella pneumonae invades

human T24 cells and whether DUOX2 plays a role in eliminating

Klebsiella pneumonae through ROS signaling in T24 cells

remains unknown. Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate

DUOX2 expression in T24 cells and to determine whether DUOX2

contributes to immune host defense and the elimination of the

Klebsiella pneumonae K5 strain in T24 cells through ROS

production.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment

T24 human bladder carcinoma cells (maintained in our

laboratory) were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (HyClone

Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT, USA) containing 10% newborn calf

serum (Lanzhou Minhai Bioengineering Co., Ltd., Gansu, China) and

grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

The experiments were performed using cells in the exponential

growth phase.

The pro-inflammatory cytokines, interferon-γ

(IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF-)α, interleukin (IL)-1β and

IL-17 (0–20 ng/ml); the NOX activator, PMA (0–1 nM); the NOD2

cognate ligand, muramyl dipeptide (MDP; 0–1 µg/ml);

N-acetylmuramyl-D-alanyl-D-isoglutamine (MDP-DD; an MDP negative

control; 0–1 µg/ml); the NOX inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium

(DPI ; 0–50 nM/ml) and the antioxidant, catalase (CAT; 0–1,000

U/ml), were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). The

cytokines were dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 1%

bovine serum albumin (BSA). DPI and PMA were dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide (DMSO). MDP and MDP-DD were dissolved in distilled water.

CAT was dissolved in RPMI-1640 medium. Untreated cells were used as

controls.

Knockdown of DUOX2 using small

interfering RNA (siRNA)

The T24 cells were transfected with 20 nM/1 siRNA

targeting DUOX2 (DUOX2 siRNA; sense, 5′-GGCAGGAGACUAU GUUCUATT-3′

and antisense, 5′-UAGAACAUAGUCUCCU GCCTT-3′) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the T24 cells were seeded in

6- or 24-well culture plates 24 h prior to transfection.

Lipofectamine 2000 (5 µl; Invitrogen Life

Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and DUOX2 siRNA (10

µl; Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China)

were added to serum-free cell culture medium prior to use and were

then mixed. The mixture was incubated for 20 min before being added

to the T24 cells (~80% confluent) which were grown for an

additional 48 h prior to use.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions, and the RNA concentration was measured at an

absorbance of 260 nm using a spectrophotometer (ULTROSPEC 2100;

Biochrom Ltd., Cambridge, UK). The quality of the isolated RNA was

confirmed on a 1% agarose gel. qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix

Ex Taq (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan) and a Bio-Rad C1000

real-time system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The primers for DUOX2 were sense,

5′-AACCTAAGCAGCTCA CAACT-3′ and antisense,

5′-CAAGAGCAATGATGGTGAT-3′), as described in a previous study

(7). The primers for GAPDH were

sense, 5′-GGTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACA-3′ and anti-sense, 5′-AGCC

AAATTCGTTGTCATAC-3′. For each PCR reaction, cDNA was synthesized

from 3 mg of RNA. The thermal cycling conditions involved an

initial step consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 30 sec, and

then 40 cycles of the following 3 steps were performed:

denaturation at 94°C for 45 sec, annealing at 55°C for 45 sec and

elongation at 72°C for 1 min. The results of RT-qPCR were analyzed

using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Western blot analysis

The T24 cells were treated with siRNA, the cytokines

(IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-17), PMA, MDP or MDP-DD for 24 h and

lysed in 2X lysis buffer (250 mM Tris-Cl, pH 6.5, 2% SDS, 4%

β-mercaptoethanol, 0.02% bromophenol blue and 10% glycerol). The

cell lysate (30 mg protein) was electrophoresed in sample buffer

containing 10% SDS, transferred onto PVDF membranes that were

blocked for 3 h in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH

7.5, and 150 mM NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween-20 and 3% BSA, and

subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody

against DUOX2 (ab170308; Abcam Plc, Cambridge, UK) at a ratio of

1:500. The membranes were then washed 3 times with

Tween-10/Tris-buffered saline (TTBS; 0.5% Tween-20 in TBS) and

incubated with an appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibody (5127s; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA,

USA). Protein bands were visualized using ECL reagent (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Removal of intracellular bacteria

The K5 bacterial strain was first grown in

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium for 4–5 h at 37°C while being shaken, and

then further subcultured for 16–18 h. A total of 100 ml of bacteria

grown to the exponential growth phase (OD650 nm, 0.4–0.6) was

centrifuged at 10,000 x g at room temperature for 2 min and

resuspended in PBS. The T24 cells were incubated with the bacteria

and resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium at 37°C for 2 h. The

extracellular bacteria were then removed by washing 3 times with

PBS supplemented with 100 mg/ml gentamicin to kill the

extracellular bacteria. The cell monolayer was then washed twice

with PBS and solubilized in 200 µl 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS

at 37°C for 15 min for cell lysis. The solute was serially diluted

in LB and plated on LB agar plates followed by incubation at 37°C,

and on the following day the colonies were counted.

Measurement of ROS levels

The T24 cells were incubated with 10 µM

2′,7′-dichlorofuorescin diacetate (DCFDA; Molecular Probes, Eugene,

USA) for 30 min and washed with 1 ml of PBS solution at least 5

times to remove the extracellular ROS. The levels of DCFDA

fluorescence were measured at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm

and an emission wavelength of 525 nm using a microplate reader

(Thermo Fisher Scientific). The values were averaged in order to

obtain the mean relative fluorescence intensity.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the t-test

with SPSS version 19.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A

p-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

DUOX2 expression induced by infection

with Klebsiella pneumoniae strain K5 suppresses the persistence of

K5 in T24 cells

To observe the intracellular destiny of the K5

bacterial strain in the T24 cells, the intracellular bacterial

colonization level in the lysates was counted at different time

points following the bacterial infection of the T24 cells by

RT-qPCR. At the same time, we examined whether DUOX2 activity

affected the persistence of the K5 strain in the T24 cells. The

number of viable intracellular bacteria peaked at 12 h, with a 52%

increase being observed at 12 h compared to the 2-h time point

(p<0.01); however, this number significantly decreased at 24, 48

and 72 h post-infection of the T24 cells with the K5 bacterial

strain when compared with the number observed at 12 h (Fig. 1A; all p<0.01). This suggests

that the intracellular bacterial growth was effectively restricted

in the T24 cells. The expression levels of DUOX2 following

infection of the T24 cells with the K5 bacterial strain were

significantly elevated at 12, 24, 48 and 72 h, reaching peak levels

at 48 h (Fig. 1B and C).

| Figure 1Infection with the Klebsiella

pneumoniae K5 bacterial strain induces dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2)

expression in T24 cells. Bacteria and T24 cells were incubated with

the K5 bacteria for 2 h, and the extracellular bacteria were

removed with gentamicin (100 mg/ml). The number of viable

intracellular bacterial was calculated using the plate count

method, and DUOX2 expression was measured by western blot analysis

at 2, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h post-infection. (A) Number of viable

intracellular bacteria. (B) Relative DUOX2 protein band intensity.

(C) DUOX2 protein expression measured by western blot analysis.

Data are representative results of at least 3 independent

experiments, each performed in triplicate.

*,**p<0.01, compared to the number of viable bacteria

at 2 and 12 h, respectively. CFU, colony forming units. |

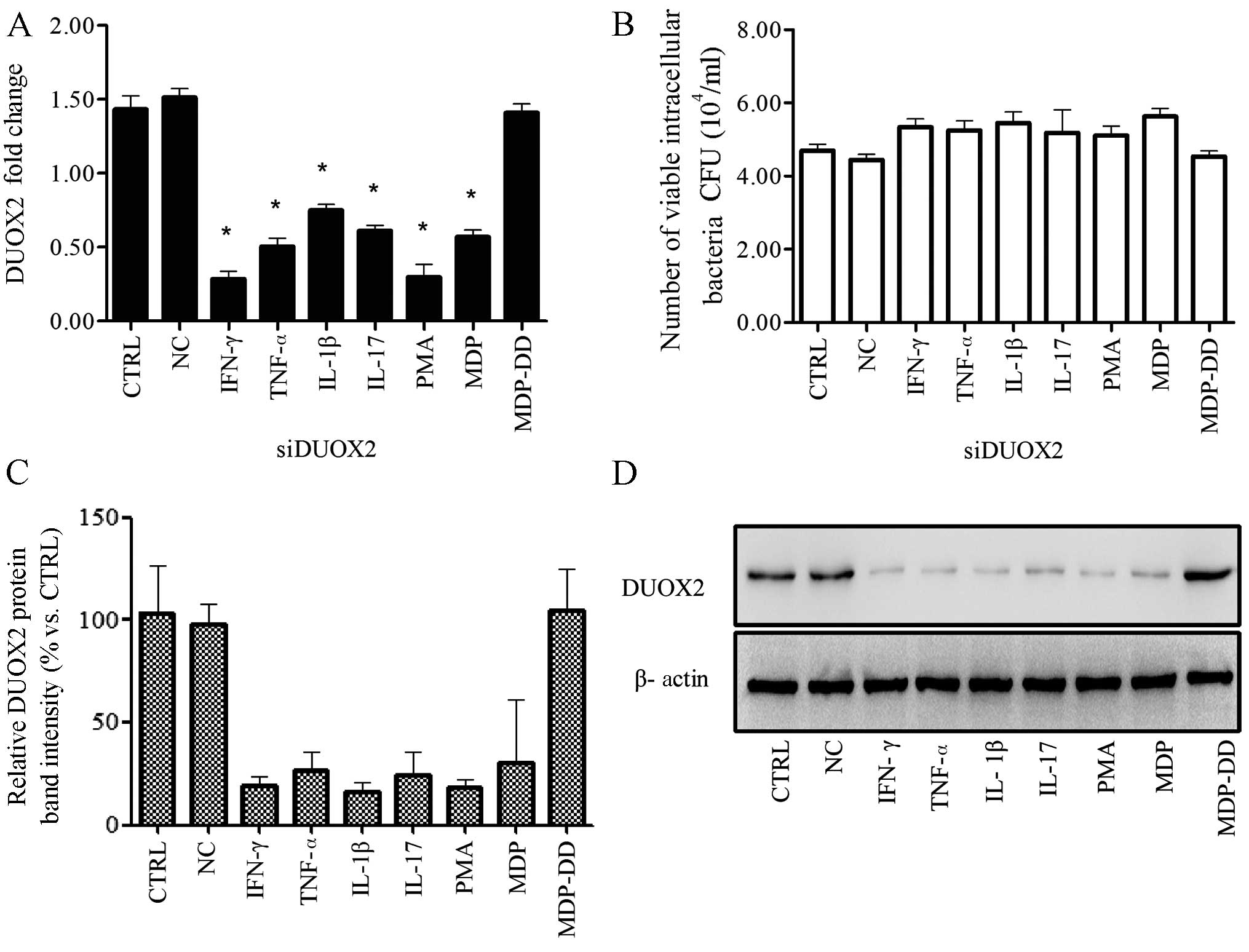

Treatment with IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, PMA

or MDP induces DUOX2 expression in T24 cells infected with the K5

bacterial strain

We verified that the T24 cells expressed DUOX2

(Fig. 1 B and C). The T24 cells

were then treated with the cytokines, TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-1β, IL-17,

or with PMA or MDP, and all treatments decreased the number of

viable intracellular bacteria when compared with the control group

(p<0.05; Fig. 2B). The DUOX2

expression levels in the T24 cells were significantly increased by

all treatments, with INF-γ (4.17-fold) and MDP (3.88-fold) having

the greatest effect on DUOX2 expression when compared with the

control group (p<0.05; Fig.

2A, C and D).

| Figure 2Chemical factors induce dual oxidase

2 (DUOX2) expression in T24 cells infected with the Klebsiella

pneumoniae K5 bacterial strain 24 h postinfection. T24 cells

were incubated with the K5 bacterial strain for 2 h, followed by

treatment with various cytokines, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

(PMA), muramyl dipeptide (MDP) and

N-acetylmuramyl-D-alanyl-D-isoglutamine (MDP-DD) for 2 h. The

extracellular bacteria were removed with gentamicin (100 mg/ml).

The number of viable intracellular bacteria was calculated using

the plate count method, and DUOX2 expression was measured by qPCR

and, western blot analysis. (A) DUOX2 was upregulated following

treatment with PMA, MDP and cytokines. Treatment with MDP-DD had no

effect. (B) The number of viable intracellular bacteria was

decreased following treatment with the reagentst. (C) Relative

DUOX2 protein band intensity. (D) DUOX2 protein expressino was

upregulated following treatment. Data are representative of at

least 3 independent experiments, performed in triplicate. CFU,

colony forming units; CTRL, control; IFN γ, interferon-γ;

TNF-α tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin. *p<0.05, compared

to the control group. |

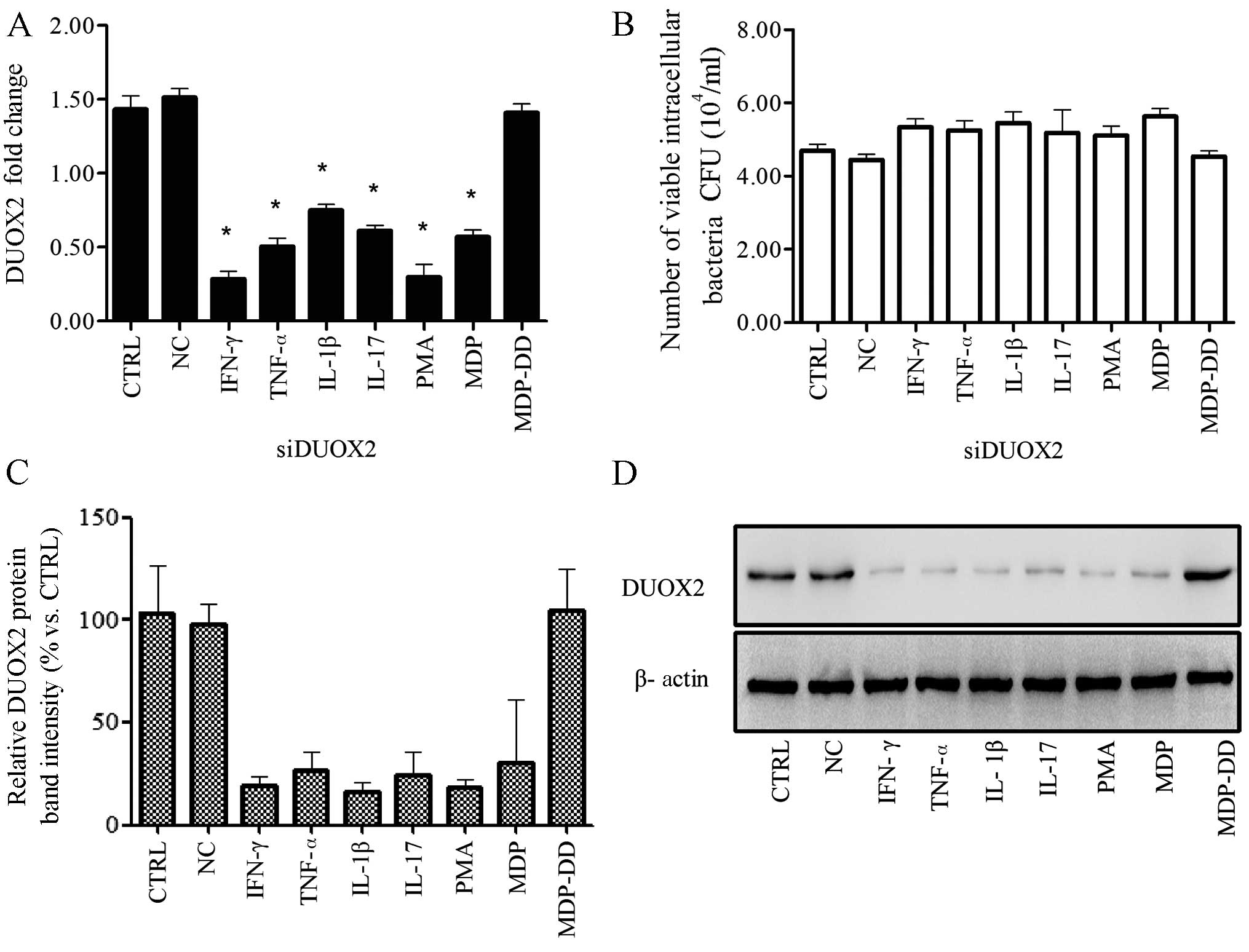

DUOX2 knockdown leads to an increase in

the number of viable K5 bacteria

The T24 cells were transfected with DUOX2 siRNA

(siDUOX2) before being infected with the K5 bacterial strain. The

extracellular bacteria were removed, and this was followed by

treatment with IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17, PMA, MDP or MDP-DD

Transfection of the cells with siDUOX2 reduced DUOX2 expression

which was induced by IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17, PMA and MDP

(Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3Knockdown of dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2)

leads to increased cell colonization 24 h post-infection with the

Klebsiella pneumoniae K5 bacterial strain. One day prior to

the knockdown of DUOX2 by siRNA, the T24 cells were incubated with

the K5 bacteria for 2 h, and this was followed by treatment with

various cytokines, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), muramyl

dipeptide (MDP) or N-acetylmuramyl-L-alanyl-D-isoglutamine (MDP-DD)

for 2 h. The extracellular bacteria were removed with gentamicin

(100 mg/ml). The number of viable intracellular bacteria was

calculated using the plate count method, and DUOX2 expression was

measured by qPCR and western blot analysis. (A) DUOX2 was

downregulated following transfection with siRNA and treatment with

cytokines, PMA, or MDP. (B) The number of viable intracellular

bacteria increased following transfection with siRNA and treatment

with the chemical reagents. (C) Relative DUOX2 intensity following

transfection with siRNA, and treatment with the cytokines, PMA, or

MDP. (D) DUOX2 protein expression was downregulated following

transfection with siRNA and treatment with the cytokines, PMA, or

MDP. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments,

performed in triplicate. CFU, colony forming units; CTRL, control;

IFN γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin.

*p<0.05, compared to the control group. |

The knockdown of DUOX2 using siRNA affected the

antibacterial activity, and the number of viable intracellular

bacteria increased by varying degrees (p>0.05) compared with the

control group (Fig. 3B). The

protein expression of DUOX2 was also suppressed to varying degrees

following transfection of the cells with siDUOX2 (p<0.01;

Fig. 3C and D).

Treatment with CAT or DPI suppresses the

clearance of bacteria mediated by cytokine-, PMA- or MDP-induced

DUOX2 expression in T24 cells infected with the K5 bacterial

strain

To determine whether the NOX inhibitor, DPI, or the

H2O2 inhibitor, CAT affects the expression of

DUOX2 in the T24 cells infected with the K5 bacterial strain, the

T24 cells were incubated with the K5 bacterial strain for 2 h, the

extracellular bacteria were removed by treatment with gentamicin

(100 mg/ml) for 1 h, and the cells were then treated with CAT or

DPI for 1 h After 1 h, the inhibitor was replaced with IFN-γ,

TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-17, PMA, MDP or MDP-DD for 24 h. Both CAT and DPI

suppressed the induction of DUOX2 expression by all cytokines, PMA,

and MDP (p<0.01; Fig. 4 A and

C) compared with the control group. This led to no significant

changes being observed in the viable intracellular bacterial

numbers compared with the control group (P>0.05; Fig. 4B and D).

| Figure 4Treatment with catalase (CAT;

H2O2 inhibitor) or diphenyleneiodonium (DPI;

NOX inhibitor) decreases dual oxidase 2 (DUOX2) expression and

suppresses the clearance of bacteria mediated by cytokine-, phorbol

12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)- or muramyl dipeptide (MDP)-induced

DUOX2 expression in T24 cells infected with the Klebsiella

pneumoniae K5 bacterial strain. T24 cells were incubated with

the K5 bacteria for 2 h and then treated with the inhibitors (CAT

and DPI) for 2 h, and the extracellular bacteria were removed with

gentamicin (100 mg/ml). The number of viable intracellular bacteria

was calculated using the plate count method, and dual oxidase 2

(DUOX2) expression was measured by qPCR. The cells were treated

with (A and C) CAT (0–1,000 U/ml) or (C and D) DPI (0–50 nM/ml).

DUOX2 expression was downregulated and the number of viable

intracellular bacteria was increased following treatment with the

inhibitors. Data are representative result of at least 3

independent experiments, performed in triplicate. CFU, colony

forming units; CTRL, control; IFN γ, interferon-γ; TNF-α tumor

necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; MDP-DD,

N-acetylmuramyl-D-alanyl-D-isoglutamine. *p<0.05,

compared to the control group. |

Treatment with cytokines, PMA or MDP

increases intracellular ROS levels and this increase is reversed by

CAT and DPI

To identify the mechanisms responsible for the

generation of intracellular ROS induced by infection with the K5

bacterial strain, the T24 cells were incubated with the K5

bacterial strain for 2 h, treated with gentamicin for 2 h to remove

extracellular bacteria, and then treated with the inhibitors (CAT

or DPI) for 2 h. The T24 cells were then incubated with 10

µM DCFDA for 30 min, and the DCFDA fluorescence levels were

then measured at 488/525 nm. All reagents (cytokines and PMA and

MDP) were found to increase ROS generation (p<0.05; Fig. 5A compared to the control group;

however, no changes in ROS levels were observed in the

MDP-DD-treated cells. Treatment with siDUOX2, CAT or DPI inhibited

the generation of intracellular ROS compared to the control group

(p<0.05; Fig. 5A-C).

Discussion

It is known that DUOX1 is expressed in uroepithelial

cells (22); however, to the best

of our knowledge, whether DUOX2 plays a role in the removal of the

K5 bacterial strain has not been reported to date. Moreover,

whether DUOX2 inhibits bacterial cytoinvasion through the ROS

signaling-mediated innate immune response in uroepithelial cells

also remains unknown. The present study demonstrated that bladder

epithelial cells have an innate antimicrobial mechanism that relies

on ROS, and that DUOX2 plays an important role in the removal of

the K5 bacterial strain through a ROS-mediated innate immune

response which promotes the elimination of intracellular bacteria.

The number of viable bacteria peaked at 12 h post-infection and

significantly diminished thereafter, as DUOX2 expression increased

(Fig. 1), indicating that

infection with the K5 bacterial strain infection induced DUOX2

expression, which in turn led to the removal of the bacteria.

The role of DUOX2 in the removal of bacteria was

confirmed by treatment with multiple cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β

and IL-17), PMA and MDP. We observed that each treatment induced

DUOX2 expression and also reduced the number of viable

intracellular bacteria (Fig. 2).

This observation was corroborated by the knockdown of DUOX2

expression with siRNA (Fig. 3).

Following the knockdown of DUOX2 expression, treatment with the

cytokines, PMA or MDP did not decrease the number of viable

intracellular bacteria, which remained relatively unaltered

compared with the control group (Fig.

3B). These findings are in line with the following findings

from other studies: the knockdown of endogenous DUOX2 expression by

RNA interference (RNAi) was shown to increase bacterial

cytoinvasion and to abrogate the cytoprotective effects exerted by

NOD2 in Caco-2 cells (23);

Drosophila dual oxidase (dDuox) was shown to be essential

for the maintenance of the intestinal redox system (24); and activated DUOX was shown to

protect zebrafish larvae from infection with Salmonella

enterica serovar Typhimurium (25).

In this study, we demonstrated that treatment with

CAT (H2O2 inhibitor and DPI (NOX inhibitor)

decreased the DUOX2 expresion levels induced by treatment with the

cytokines, PMA, or MDP. As a result, following treatment with CAT

and DPI, the numbers of viable bacterial numbers were relatively

unaltered when compared to the control groups, even those which had

been treated with the cytokines, PMA, or MDP (Fig. 4B and D). Additionally, treatment

with all of the cytokines, PMA, or MDP increased the levels of ROS,

while treatment with siDUOX2, CAT and DPI decreased the ROS levels,

suggesting that DUOX2 promotes the elimination of bacterial from

T24 cells through the ROS signaling pathway.

IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-1β are well-known classic

pro-inflammatory and anti-pathogenic cytokines. IFN-γ increases

DUOX2 expression levels in the respiratory epithelium (26). TNF-α, in synergy with IFN-β,

induces DUOX2 NOX expression (17). Signal transduction and

inflammatory responses induced by IL-1β are related to the activity

of NOX-1 in Caco-2 cells (27,28). IL-17 is essential for host defense

against a number of microbes, particularly extracellular bacteria

and fungi (29), and it induces

NOX production in human cartilage, chondrocytes and osteoarthritic

human and mouse cartilage (30,31). As an immunoadjuvant and

peptidoglycan (a structural subunit of the bacterial cell wall),

MDP enhances the ability of phagocytes to engulf bacteria,

increases natural killer (NK) cell lethality and promotes T cell

activation in order to strengthen host resistance to pathogen

infection. MDP is a well-known ligand for the intracellular NOD2

receptor (32).

NOX appears to be a particularly important enzyme

for ROS generation in non-phagocytic cells, and it is a prominent

generator of ROS in the airway epithelium (33,34). Mounting evidence indicates that

intracellular ROS facilitates cellular damage or stress and

contributes to innate immune activation (35). ROS enhance host immunity through

the prevention of pathogen-induced pro-inflammatory cytokines

(36–38).

Nuclear factor (NF)-κB is a critical signaling

molecule in H2O2-induced inflammation and

responses evoked by a variety of stimuli, including growth factors,

lymphokines, ultraviolet irradiation, pharmacological agents and

oxidative stress (39). A growing

body of evidence indicates that endogenous ROS are characteristic

of typical second messengers responsible for the activation of

NF-κB in a variety of cell types, including neutrophils,

lymphocytes, endothelial cells and epithelial cells (19). In particular, the NOX family

member, DUOX2, is involved in NOD2-dependent ROS production

(19). DUOX2 functions as a

molecular switch that enhances the protective properties of NOD2

through both direct (generation of bactericidal ROS) and indirect

mechanisms (by amplifying NF-κB signaling) (16). PMA, a protein kinase C activator,

activates NAPDH protein molecules, induces DUOX2 phosphorylation to

generate high levels of H2O2 (15,30) and promotes antibacterial effects

exerted by the NOX family. The antibacterial role of PMA may be

evidenced through the NF-κB signaling pathway. MDP is a

peptidoglycan moiety derived from commensal and pathogenic bacteria

and a ligand of its intracellular sensor NOD2. The ex vivo

stimulation of human carotid plaques with MDP has been shown to

lead to the enhanced activation of the inflammatory signaling

pathways, p38 and MAPK, and the NF-κB-mediated release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines (40).

IFN-β and IL-1β can cooperate synergistically to upregulate DUOX2

expression, and the contribution of NF-κB signaling to DUOX2

expression cannot be excluded, since IL-1β signaling also activates

NF-κB (22). TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-1β

and IL-17 are important cytokines that regulate host immune

defense, and thus we hypothesized that they may also function

through NF-κB signaling to increase DUOX2 expression in infected

T24 cells.

Mechanistically, NOX-mediated ROS generation

constitutes a well-known host defense mechanism in phagocytes, and

DUOX1 and DUOX2 provide extracellular H2O2 to

lactoperoxidase (LPO) to produce antimicrobial hypothiocyanite ions

(11). DUOX-generated

H2O2, in conjunction with LPO and thiocyanate

(SCN−), kills bacteria in the respiratory tract (41,42). The presence of

H2O2 in the airway allows LPO to oxidize the

airway surface liquid (ASL) component, SCN (27), thereby generating antimicrobial

hypothiocyanite (OSCN) in order to support oxidant-mediated

bacterial killing in the airways (42). In a previous study, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa flagellin infected human airway epithelial cells to

facilitate host invasion through the inactivation of the

DUOX/LPO/SCN−protective system (42). OSCN− is abundantly

found in saliva and other mucosal secretions, acting as an

effective microbicidal or microbiostatic agent, and the

DUOX/LPO/SCN− antimicrobial system is fully assembled

only in the final stages of saliva formation, with

H2O2 provided by DUOX2 (43). H2O2

generated by DUOX in the airway epithelium supports the production

of bactericidal OSCN(-) in the presence of the airway surface

liquid components, LPO, and SCN(-), and OSCN(-) eliminates

Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa on

airway mucosal surfaces (11).DUOX1 also plays a role in the

protection of urothelial cells, and alterations in ROS production

in the urothelium may contribute to the development of bladder

diseases (22).

In conclusion, the findings of the present study

demonstrate that innate immunity may protect T24 bladder cancer

cells from invasion by the K5 bacterial strain through the

upregulation of DUOX2 expression, mediated through ROS signaling.

Our findings provide insight into the mechanisms through which

uroepithelial cells are protected from cytoinvasion by the K5

bacterial strain, and may thus lead to the development of novel

therapeutic strategies for urinary tract infections.

References

|

1

|

Meca G, Sospedra I, Valero MA, Mañes J,

Font G and Ruiz MJ: Antibacterial activity of the enniatin B,

produced by Fusarium tricinctum in liquid culture, and cytotoxic

effects on Caco-2 cells. Toxicol Mech Methods. 21:503–512. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Rhim AD, Stoykova L, Glick MC and Scanlin

TF: Terminal glycosylation in cystic fibrosis (CF): Aa review

emphasizing the airway epithelial cell. Glycoconj J. 18:649–659.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Swords WE, Chance DL, Cohn LA, Shao J,

Apicella MA and Smith AL: Acylation of the lipooligosaccharide of

Haemophilus influenzae and colonization: an htrB mutation

diminishes the colonization of human airway epithelial cells.

Infect Immun. 70:4661–4668. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Loose M, Hudel M, Zimmer KP, Garcia E,

Hammerschmidt S, Lucas R, Chakraborty T and Pillich H: Pneumococcal

hydrogen peroxide-induced stress signaling regulates inflammatory

genes. J Infect Dis. 211:306–316. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cortés G, Alvarez D, Saus C and Albertí S:

Role of lung epithelial cells in defense against Klebsiella

pneumoniae pneumonia. Infect Immun. 70:1075–1080. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Rosen DA, Pinkner JS, Walker JN, Elam JS,

Jones JM and Hultgren SJ: Molecular variations in Klebsiella

pneumoniae and Escherichia coli FimH affect function and

pathogenesis in the urinary tract. Infect Immun. 76:3346–3356.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zgair AK and Al-Adressi AM:

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia fimbrin stimulates mouse bladder

innate immune response. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis.

32:139–146. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Michelet C, Avril JL, Cartier F and Berche

P: Inhibition of intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes by

antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 38:438–446. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nakagawa I, Amano A, Mizushima N, Yamamoto

A, Yamaguchi H, Kamimoto T, Nara A, Funao J, Nakata M, Tsuda K, et

al: Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus.

Science. 306:1037–1040. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Grasberger H, El-Zaatari M, Dang DT and

Merchant JL: Dual oxidases control release of hydrogen peroxide by

the gastric epithelium to prevent Helicobacter felis infection and

inflammation in mice. Gastroenterology. 145:1045–1054. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Rada B and Leto TL: Oxidative innate

immune defenses by Nox/Duox family NADPH oxidases. Contrib

Microbiol. 15:164–187. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Enyedi B and Niethammer P:

H2O2: a chemoattractant? Methods Enzymol.

528:237–255. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Geiszt M and Leto TL: The Nox family of

NAD(P)H oxidases: host defense and beyond. J Biol Chem.

279:51715–51718. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lees MS, H Nagaraj S, Piedrafita DM, Kotze

AC and Ingham AB: Molecular cloning and characterisation of ovine

dual oxidase 2. Gene. 500:40–46. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rigutto S, Hoste C, Grasberger H,

Milenkovic M, Communi D, Dumont JE, Corvilain B, Miot F and De

Deken X: Activation of dual oxidases Duox1 and Duox2: differential

regulation mediated by camp-dependent protein kinase and protein

kinase C-dependent phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 284:6725–6734.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kim HJ, Kim CH, Ryu JH, Kim MJ, Park CY,

Lee JM, Holtzman MJ and Yoon JH: Reactive oxygen species induce

antiviral innate immune response through IFN-λ regulation in human

nasal epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 49:855–865.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fink K, Martin L, Mukawera E, Chartier S,

De Deken X, Brochiero E, Miot F and Grandvaux N: IFNβ/TNFα

synergism induces a non-canonical STAT2/IRF9-dependent pathway

triggering a novel DUOX2 NADPH oxidase-mediated airway antiviral

response. Cell Res. 23:673–690. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Strengert M, Jennings R, Davanture S,

Hayes P, Gabriel G and Knaus UG: Mucosal reactive oxygen species

are required for antiviral response: Rrole of Duox in influenza a

virus infection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 20:2695–2709. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Lipinski S, Till A, Sina C, Arlt A,

Grasberger H, Schreiber S and Rosenstiel P: DUOX2-derived reactive

oxygen species are effectors of NOD2-mediated antibacterial

responses. J Cell Sci. 122:3522–3530. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ronald A and Ludwig E: Urinary tract

infections in adults with diabetes. Int J Antimicrob Agents.

17:287–292. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hansen DS, Gottschau A and Kolmos HJ:

Epidemiology of Klebsiella bacteraemia: Aa case control study using

Escherichia coli bacteraemia as control. J Hosp Infect. 38:119–132.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Donkó A, Ruisanchez E, Orient A, Enyedi B,

Kapui R, Péterfi Z, de Deken X, Benyó Z and Geiszt M: Urothelial

cells produce hydrogen peroxide through the activation of Duox1.

Free Radic Biol Med. 49:2040–2048. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

El Hassani RA, Benfares N, Caillou B,

Talbot M, Sabourin JC, Belotte V, Morand S, Gnidehou S, Agnandji D,

Ohayon R, et al: Dual oxidase2 is expressed all along the digestive

tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 288:G933–G942.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ha EM, Oh CT, Bae YS and Lee WJ: A direct

role for dual oxidase in Drosophila gut immunity. Science.

310:847–850. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Flores MV, Crawford KC, Pullin LM, Hall

CJ, Crosier KE and Crosier PS: Dual oxidase in the intestinal

epithelium of zebrafish larvae has anti-bacterial properties.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 400:164–168. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Harper RW, Xu C, Eiserich JP, Chen Y, Kao

CY, Thai P, Setiadi H and Wu R: Differential regulation of dual

NADPH oxidases/peroxidases, Duox1 and Duox2, by Th1 and Th2

cytokines in respiratory tract epithelium. FEBS Lett.

579:4911–4917. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Geiszt M, Lekstrom K, Brenner S, Hewitt

SM, Dana R, Malech HL and Leto TL: NAD(P)H oxidase 1, a product of

differentiated colon epithelial cells, can partially replace

glycoprotein 91phox in the regulated production of superoxide by

phagocytes. J Immunol. 171:299–306. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Geiszt M, Lekstrom K, Witta J and Leto TL:

Proteins homologous to p47phox and p67phox support superoxide

production by NAD(P)H oxidase 1 in colon epithelial cells. J Biol

Chem. 278:20006–20012. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

O’Quinn DB, Palmer MT, Lee YK and Weaver

CT: Emergence of the Th17 pathway and its role in host defense. Adv

Immunol. 99:115–163. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Miljkovic D and Trajkovic V: Inducible

nitric oxide synthase activation by interleukin-17. Cytokine Growth

Factor Rev. 15:21–32. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Trajkovic V, Stosic-Grujicic S, Samardzic

T, Markovic M, Miljkovic D, Ramic Z and Mostarica Stojkovic M:

Interleukin-17 stimulates inducible nitric oxide synthase

activation in rodent astrocytes. J Neuroimmunol. 119:183–191. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Willems MM, Zom GG, Meeuwenoord N,

Ossendorp FA, Overkleeft HS, van der Marel GA, Codée JD and

Filippov DV: Design, automated synthesis and immunological

evaluation of NOD2-ligand-antigen conjugates. Beilstein J Org Chem.

10:1445–1453. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Kim HJ, Kim CH, Ryu JH, Joo JH, Lee SN,

Kim MJ, Lee JG, Bae YS and Yoon JH: Crosstalk between

platelet-derived growth factor-induced Nox4 activation and MUC8

gene overexpression in human airway epithelial cells. Free Radic

Biol Med. 50:1039–1052. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

van der Vliet A: NADPH oxidases in lung

biology and pathology: hHost defense enzymes, and more. Free Radic

Biol Med. 44:938–955. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Arnoult D, Carneiro L, Tattoli I and

Girardin SE: The role of mitochondria in cellular defense against

microbial infection. Semin Immunol. 21:223–232. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gao XP, Standiford TJ, Rahman A, Newstead

M, Holland SM, Dinauer MC, Liu QH and Malik AB: Role of NADPH

oxidase in the mechanism of lung neutrophil sequestration and

microvessel injury induced by Gram-negative sepsis: Studies in

p47phox−/− and gp91phox−/− mice. J Immunol.

168:3974–3982. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Koarai A, Sugiura H, Yanagisawa S,

Ichikawa T, Minakata Y, Matsunaga K, Hirano T, Akamatsu K and

Ichinose M: Oxidative stress enhances toll-like receptor 3 response

to double-stranded RNA in airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell

Mol Biol. 42:651–660. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

38

|

Zmijewski JW, Lorne E, Zhao X, Tsuruta Y,

Sha Y, Liu G and Abraham E: Antiinflammatory effects of hydrogen

peroxide in neutrophil activation and acute lung injury. Am J

Respir Crit Care Med. 179:694–704. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hou Y, An J, Hu XR, Sun BB, Lin J, Xu D,

Wang T and Wen FQ: Ghrelin inhibits interleukin-8 production

induced by hydrogen peroxide in A549 cells via NF-kappaB pathway.

Int Immunopharmacol. 9:120–126. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kim JY, Omori E, Matsumoto K, Núñez G and

Ninomiya-Tsuji J: TAK1 is a central mediator of NOD2 signaling in

epidermal cells. J Biol Chem. 283:137–144. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Forteza R, Salathe M, Miot F, Forteza R

and Conner GE: Regulated hydrogen peroxide production by Duox in

human airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

32:462–469. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gattas MV, Forteza R, Fragoso MA, Fregien

N, Salas P, Salathe M and Conner GE: Oxidative epithelial host

defense is regulated by infectious and inflammatory stimuli. Free

Radic Biol Med. 47:1450–1458. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Geiszt M, Witta J, Baffi J, Lekstrom K and

Leto TL: Dual oxidases represent novel hydrogen peroxide sources

supporting mucosal surface host defense. FASEB J. 17:1502–1504.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|