Introduction

Organ transplantation is the most effective

treatment for end-stage organ failure (1). The surgical methods of organ

transplantation are now widely used; however, allograft rejection

limits its further development. A major task in transplantation

research is to rapidly achieve a state of immunological tolerance

to alloantigens (2). T cells play

a key role in regulating transplantation immunology. Allospecific T

cell tolerance implies that T cells do not mount pathogenic immune

reactions towards allogeneic organs, but preserve protective

activity towards environmental pathogens. Thus, allospecific

tolerized T cells are critical to accomplishing transplantation

tolerance (3,4).

Costimulation blockade is an emerging therapeutic

strategy in transplantation medicine that circumvents the need for

lifelong chronic immunosuppression by inhibiting the activation of

the immune system at the time of transplantation (5). OX40 is a costimulatory receptor

expressed primarily on activated CD4+ and

CD8+ T cells. OX40 ligand (OX40L) is expressed on

activated antigen-presenting cells and binds to OX40, inducing an

agonistic response in T lymphocytes, that results in cell

proliferation, increased cytokine production and the long-term

survival of T lymphocytes (6). As

a costimulator, OX40 is a promising drug target for T cell-mediated

inflammatory diseases (7). The

blockade of the OX40 and OX40L pathway has been shown to inhibit

graft rejection and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), and to

ameliorate autoimmune diseases (8,9).

In addition, we previously demonstrated that the blockade of the

OX40-OX40L pathway by OX40-Ig fusion protein (OX40Ig) may induce

antigen-specific T cell anergy in vitro in patients with

acute renal allograft rejection (10).

Cell therapies applied to solid organ

transplantation have gained much attention over the past years, and

among these therapies, mesenchymal stem/stromal cell (MSC) therapy

has strongly emerged as one of the main therapies. In addition to

their potential role in therapies for renal repair, the

immunomodulatory properties of MSCs offer promise as a novel

cellular therapy for the long-term protection of kidney allografts

(11). Although the most common

and well-characterized source of MSCs is the bone marrow, adipose

tissue is the most promising source of MSCs suitable for autologous

stem cell therapy. Adipose tissue has several advantages as a

tissue stem cell source, including the richest source, easy

accessibility, less invasive collection procedures and safe,

autologous cell transplantation without immune rejection (12–14). Although MSC-based therapies have

been shown to be safe and effective to a certain degree, the

efficacy of MSCs in vivo remains low in most cases when MSCs

are applied alone.

MSC monotherapy and costimulation blockade modulate

many of the same components of the immune system and can induce the

peripheral conversion of T cells into regulatory T cells (Tregs).

These two treatment strategies are being tested independently in

clinical organ transplantation and in autoimmune diseases. Since

these strategies share common goals and converge on some of the

same target cells, it seems imperative to study their ability to

synergize in downmodulating immune responses. For example,

Takahashi et al (15)

demonstrated that the combination of MSCs and costimulation

blockade yielded superior islet graft survival and function.

However, the half-time of an injected Ig fusion protein is reduced

and the patient needs more of the biological agent to achieve the

same effect in vivo. To enhance their therapeutic efficacy,

genetic engineering is one approach to improve the in vivo

performance of MSCs. As MSCs migrate to the target tissue, the

therapeutic agent can be released in a local and sustained

manner.

The aim of the present study was to clone OX40Ig to

generate a recombinant pcDNA3.1(−)OX40Ig vector and trans-duce the

vector into Lewis rat recipient adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal

stem cells (ADSCs). We also investigated the anti-proliferative

activity in vitro, as well as the prevention of graft

rejection following allogeneic renal transplantation.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 60 age-matched inbred male Brown Norway

(BN, RT1n) and 84 Lewis (LEW, RT1) rats

weighing 200 to 250 g were obtained from the Academy of Military

Medical Science [Beijing, China; certificate no. SCXK (JUN)

2007-004]. These animals were maintained in a standard animal

laboratory with free activity and free access to water and rodent

chow. They were maintained in a temperature controlled environment

at 22–24°C with a 12 h light/dark cycle. The rats were fasted for

12 h prior to surgery, and were provided with free access to 10%

glucose water following surgery. All the surgical procedures were

performed under sanitary conditions, and all the experiments were

performed according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (16). The present study was approved

(approval ID no. E2013008K) by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin

First Central Hospital (Tianjin, China).

Isolation and characterization of MSCs

from rat adipose tissue

ADSCs were isolated from LEW rats (n=72) using a

previously described method (17). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized

with isoflurane inhalation (LUNAN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.,

Shandong, China) 14 days before mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR)

assay and autologous cell transplantation, and the subcutaneous

adipose tissue was then obtained from the hemi-inguinal regions of

these rats, which were carefully excised and minced into ~1

mm3 sections. The adipose tissue was digested in

collagenase type I solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for

60 min at 37°C with constant agitation (100 rpm). The stromal cells

were separated from the floating adipocytes by centrifugation at

200 × g for 5 min at room temperature. The cells released were then

resuspended in DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), then

sieved through a 70 µm mesh (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA, USA).

The resulting ADSCs were cultivated in DMEM/F12 medium containing

10% FBS (Gibco). When the cells reached confluence, the adherent

cells were detached with trypsin/ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

(EDTA) (Sigma-Aldrich) and reseeded for expansion. Following in

vitro culture for 14 days at 37°C, 5% CO2 and 95%

humidity, we obtained a sufficient amount of ADSCs for autologous

transplantation. The cultured ADSCs (3×106) from each

experimental rat were respectively labeled and cryopreserved in

liquid nitrogen [Air Products and Chemicals (Tianjin) Co., Ltd.,

Tianjin, China] prior to injection.

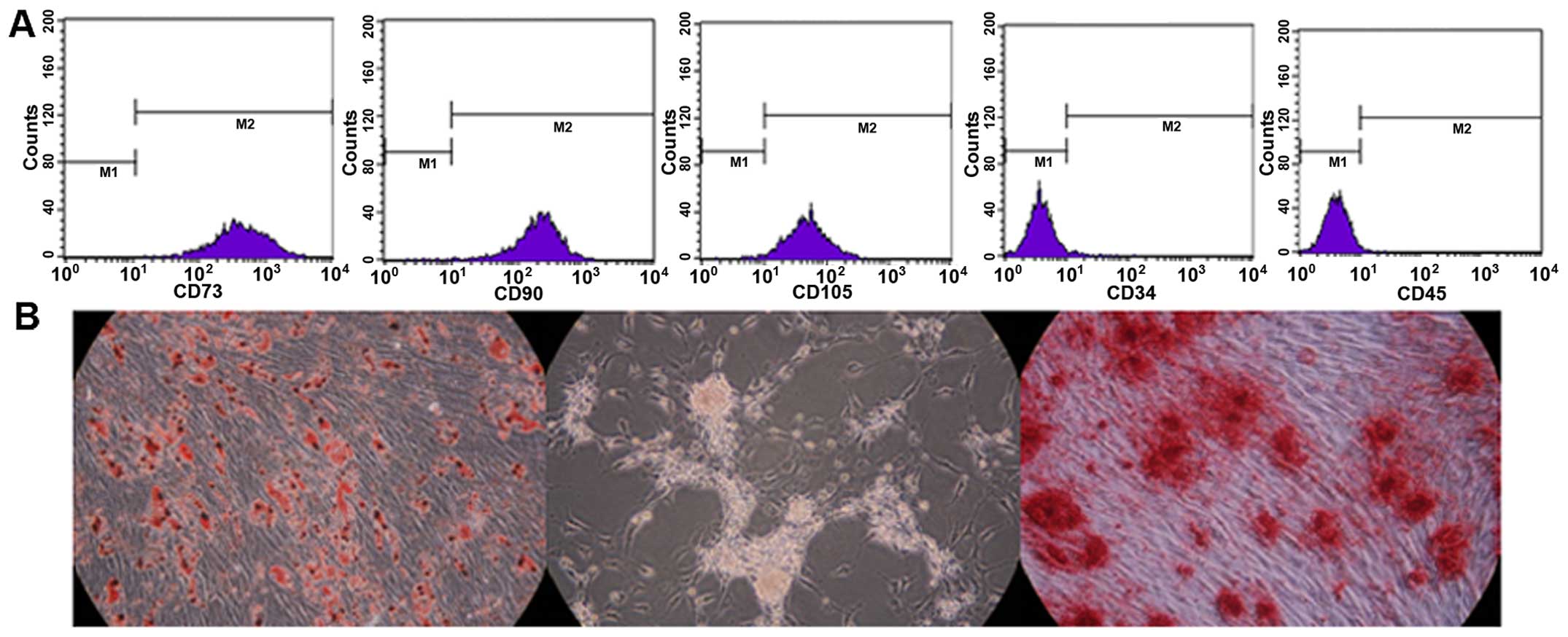

The cultured ADSCs were characterized for the

expression of hematopoietic markers, CD34 and CD45, and mesenchymal

cell markers, CD90, CD73 and CD105 by fluorescence-activated cell

sorting (FACS) analysis using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur flow

cytometer; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and data

were analyzed using the CellQuest software program.

Multi-differentiation ability of

ADSCs

DSCs were also confirmed by their capacity to

differentiate into adipogenic, islet and osteogenic lineages as

previously described (17).

Briefly, the ADSCs were seeded in medium at 2×104

cells/cm2 in 6-well tissue culture plates. When the

cells reached 100% confluency, DMEM/F12 was subsequently replaced

with specific inducer medium. Adipogenic inducer medium is DMEM/F12

containing 1 µmol/l dexamethasone, 0.5 mmol/l

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mg/l insulin

(Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µmol/l indomethacin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Islet inducer medium is DMEM (high glucose; Gibco) containing 10

mmol/l nicotinamide (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 µg/l conophylline

(BioBioPha, Yunnan, China), 10 µg/l betacellulin (PeproTech,

Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), 10 µg/l hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)

(PeproTech), 2% B27 supplement (Gibco), 1% N2 supplement (Gibco).

Osteogenic inducer medium is DMEM/F12 containing 100 nmol/l

dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 mmol/l β-sodium glycerophosphate

(Sigma-Aldrich) and 50 µg/ml vitamin C (Sigma-Aldrich).

Following a 21-day induction period, adipocytes, islet-like cells,

and osteoblasts were identified by Oil Red O staining

(Sigma-Aldrich), dithizone staining (Sigma-Aldrich), and Alizarin

Red S staining (Genmed, Shanghai, China), respectively.

Eukaryotic expression vector

construction

Briefly, the NCBI database was screened for coding

sequences of rat OX40 extracellular domains. RNA was extracted from

rat peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using TRIzol reagent

(Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using

a reverse transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The

cycling conditions for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were 94°C

for 4 min; followed by 32 cycles of 94°C for 60 sec, 58°C for 60

sec, and 72°C for 60 sec; and then 72°C for 10 min. OX40 primers,

designed with Primer Premier 5.0 software (Premier Biosoft, Palo

Alto, CA, USA), were added into the cDNA mixture for PCR

amplification (Promega). The primers used were designed as follows

(forward and reverse, respectively):

5′-ACGGGATCCACCACCATGGTTACAGTGAAGCTCAAC-3′ and

5′-CGGAATTCAGGGCCCTCAGGAGCCACC-3′ (underlined letters denote

restriction endo-nuclease recognition sequences). These PCR

products were inserted into the pcDNA3.1(+)/linker (Life

Technologies) plasmid using BamHI and EcoRI

restriction sites to generate the recombinant plasmid,

pcDNA3.1(+)/OX40-linker. The plasmid was double-checked by

BamHI-EcoRI digestion with electrophoresis on agarose

gel and sequencing (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

A PCR-amplified cDNA fragment encoding the human IgG

Fc fragment was inserted into the XhoI and XbaI sites

of the pcDNA3.1(+)/OX40-linker vector to obtain the eukaryotic

expression vector (plasmids) pcDNA3.1(+)/OX40-IgG Fc

(pcDNA3.1/OX40Ig). The human IgG Fc primers used were designed as

follows (forward and reverse, respectively): 5′-GTCAGCTCGAGGCAAGCTTCAAGGGCC-3′ and

5′-GCTCTAGACTATTTACCCGGAGACAGGGAGAG-3′

(the underlined letters denote restriction endonuclease recognition

sequences). The constructed plasmids were verified by double

restriction endonuclease digestion and DNA sequence analysis to

confirm the sequence accuracy. The cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter

pcDNA3.1(+)/GFP (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to gauge

the transfection efficiency.

ADSC nucleofection

The nucleofection of the ADSCs was performed

according to the optimized protocols provided by the manufacturer

(Amaxa Biosystems, Cologne, Germany). Briefly, prior to

nucleofection, a Petri dish culture containing 1 ml of DMEM was

incubated in the CO2 incubator at 37°C. The ADSCs were

digested and centrifuged following the adjustment of the density of

the suspended cells to 2×106/ml. The cells

(5×105) and plasmid (2 µg) were suspended in 100

µl prewarmed nucleofector solution (Amaxa Biosystems). For

nucleofection, the program U-23 was selected. Immediately,

following nucleofection, the cells were transferred into prewarmed

fresh medium in six-well plates, and incubated in a CO2

incubator at 37°C and monitored daily. The cells were analyzed 24 h

post-nucleofection for transfection efficiency by FACS (FACSCalibur

flow cytometer; Becton-Dickinson) and a Nikon Ts100 fluorescence

microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) for GFP expression. The

ADSCs transduced with pcDNA3.1/OX40Ig or pcDNA3.1/GFP are referred

to as ADSCsOX40Ig or ADSCsGFP,

respectively.

Western blot analysis

The transduced OX40Ig was confirmed by western blot

analysis, as previously described (18). Briefly, the transduced ADSCs

(ADSCsOX40Ig or ADSCsGFP) were fractionated

on a 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and the fractionated proteins were

electrophoretically transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes

(Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The protein samples were then

incubated with primary anti-OX40 rabbit polyclonal antibodies (Cat

no. ab203220) and thereafter with a horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Cat no.

ab6721) (both from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). Protein bands were

visualized using an ECL western blotting kit (Amersham Pharmacia

Biotech, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

MLR assay

To test the allostimulatory activity of the

gene-transduced ADSCs, one-way MLR were performed. Splenocytes from

the 24 BN and 24 LEW rats were filtered through nylon cell

strainers (BD Falcon). The lymphocyte population was purified by

density gradient centrifugation using a commercially lymphocyte

separation medium (Sigma-Aldrich) and centrifuged at 400 × g for 25

min. The LEW lymphocytes (1×105, responders) and BN

lymphocytes (2×105, stimulator) were co-cultured with

untransduced ADSCs (ADSCsnative), ADSCsGFP,

or ADSCsOX40Ig (1×104) in 0.2 ml of culture medium. The

stimulator was mitotically inactivated with 50 µg/ml

mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37°C for 30 min prior to MLR

co-culture, while the responder was not treated. The mitomycin C

pre-treated ADSCsnative, ADSCsGFP, or

ADSCsOX40Ig were allowed to adhere to the plate for 2 h

before the lymphocytes were added to allow attachment. The cultures

were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5%

CO2. Following routine culture for 4 days, MTT

colorimetry was used to measure the absorbance values at 570 nm in

each well. The inhibitory rate was calculated according to the

following formula: inhibitory rate (%) = (1 − average absorbance

for experimental group/average absorbance for control group)

×100.

Flow cytometric assessment of

CD4+CD25+ Tregs

The cells were analyzed for Treg markers using mouse

anti-rat monoclonal antibody to CD4 (Cat no. 554843) and CD25 (Cat

no. 554866) (both from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA). A

FACSCalibur flow cytometer was used to determine the

CD4+CD25+ cells, and data analysis was

performed using CellQuest software (both from BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Rat renal transplantation model

For orthotopic renal transplantation, the 36 LEW

rats received a kidney from the 36 BN rats using a previously

described technique (19). In

brief, following humane animal sacrifice by deep anesthesia with

isoflurane inhalation (LUNAN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.), the kidneys

from the BN rats were harvested, perfused with hypertonic

citrate-adenine preservation (HC-A) solution (provide by the Long

March Hospital of Shanghai, China) to remove blood from the

vascular beds and maintained at 4°C until implantation. The kidney

grafts were transplanted orthotopically into left nephrectomized

LEW rat recipients, and the blood flow was restored using standard

microsurgical techniques. The contralateral kidneys were removed

immediately following the implantation of the left kidney graft.

After the effect of graft reperfusion was observed, the abdomen was

closed. No immunosuppressive agents were provided. All

microsurgical procedures were performed by one surgeon. Five days

post-transplantation, the rats were euthanized by deep anesthesia

as described above, the grafts were removed and subjected to

morphological, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) and

biochemical analysis.

Cell transplantation procedures

In the BN-LEW allograft models, the LEW recipient

rats were injected with autologous 2.0×106 ADSCs diluted

in 1 ml PBS or 1 ml PBS alone via the penile vein 4 days prior to

transplantation, and intrarenal injection performed immediately

following reperfusion, followed by an intravenous injection 6 h

after the ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) procedure through the penile

vein. The LEW-LEW syngeneic transplant models (n=12) were used as a

control group.

The animals were randomly divided into 4 groups as

follows: the isografts control group (n=12), the PBS control group

(n=12), the ADSCsnative-treated group (n=12), and the

ADSCsOX40Ig-treated group (n=12).

Renal function analysis

The 2 ml of blood was collected from the inferior

vena cava at days 5 post-transplantation. Serum creatinine (SCr)

levels were determined as a measure of renal function via an

enzymatic colorimetric method using an automatic biochemistry

analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Renal histopathological analysis

The excised kidneys were fixed in formalin overnight

and embedded in paraffin wax. Five-micrometer-thick kidney sections

were deparaffinized and fixed. For histological analysis, the

sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E;

Sigma-Aldrich), and observed using a Nikon Ni-U fluorescence

microscope (Nikon Corp.).

Examination of gene expression by

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the frozen kidney

tissue samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then subjected

to reverse transcription using a High Capacity cDNA Reverse

Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies, Foster

City, CA, USA). qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 Sequence

Detection System (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies) with

SYBR-Green (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). Rat primer sequences for

intragraft interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10,

transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), forkhead box protein 3

(Foxp3) and β-actin were as follows: IFN-γ sense,

5′-AGGCCATCAGCAACAACATAAGTG-3′ and antisense,

5′-GACAGCTTTGTGCTGGATCTGTG-3′; IL-4 sense,

5′-AGAAGCTGCACCGTGAATGA-3′ and antisense,

5′-TCGTAGGATGCTTTTTAGGCTTTC-3′; IL-10 sense,

5′-AAGGCCATGAATGAGTTTGACAT-3′ and antisense,

5′-CGGGTGGTTCAATTTTTCATTT-3′; TGF-β sense,

5′-CAAGGGCTACCATGCCAACT-3′ and antisense,

5′-CCGGGTTGTGTTGGTTGTAGA-3′; Foxp3 sense,

5′-ACCGTATCTCCTGAGTTCCAT-3′ and antisense,

5′-GTCCAGCTTGACCACAGTTTAT-3′; and β-actin sense,

5′-CGTTGACATCCGTAAAGACCTC-3′ and antisense,

5′-TAGGAGCCAGGGCAGTAATCT-3′. The level of expression was calculated

using the 2−ΔCt method, in which ΔCt was calculated as

the Ct value of the target molecule - the Ct value of β-actin.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the means ± standard

deviation. Comparisons among treatment groups were analyzed by

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Animal survival analysis was

performed using Kaplan-Meier survival estimates, and statistical

significance was analyzed by the log-rank test. Statistical

analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). A value of P <0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Recombinant eukaryotic expression

plasmid

The recombinant vector, pcDNA3.1/OX40Ig, was

identified by restrict enzyme digestion assay (Fig. 1). The DNA sequencing data of the

pcDNA3.1/OX40Ig was consistent with DNA sequences of OX40 (extra)

and IgG Fc listed in GenBank (data not shown).

Phenotypic and functional

characterization of rat ADSCs

The adherent ADSCs had a spindle-shaped fibroblastic

morphology following expansion. The rat ADSCs expressed typical

markers and differentiation profiles. They strongly expressed the

stem cell markers, CD90, CD73 and CD105, but were negative for the

hematopoietic markers, CD34 and CD45, as shown by flow cytometric

analysis (Fig. 2A). In addition,

the culture-expanded ADSCs were also functionally capable of

differentiating into adipocytes, islet-like cells and osteoblasts

under inductive culture conditions, and this was confirmed using

Oil Red O, dithizone and Alizarin Red S staining (Fig. 2B).

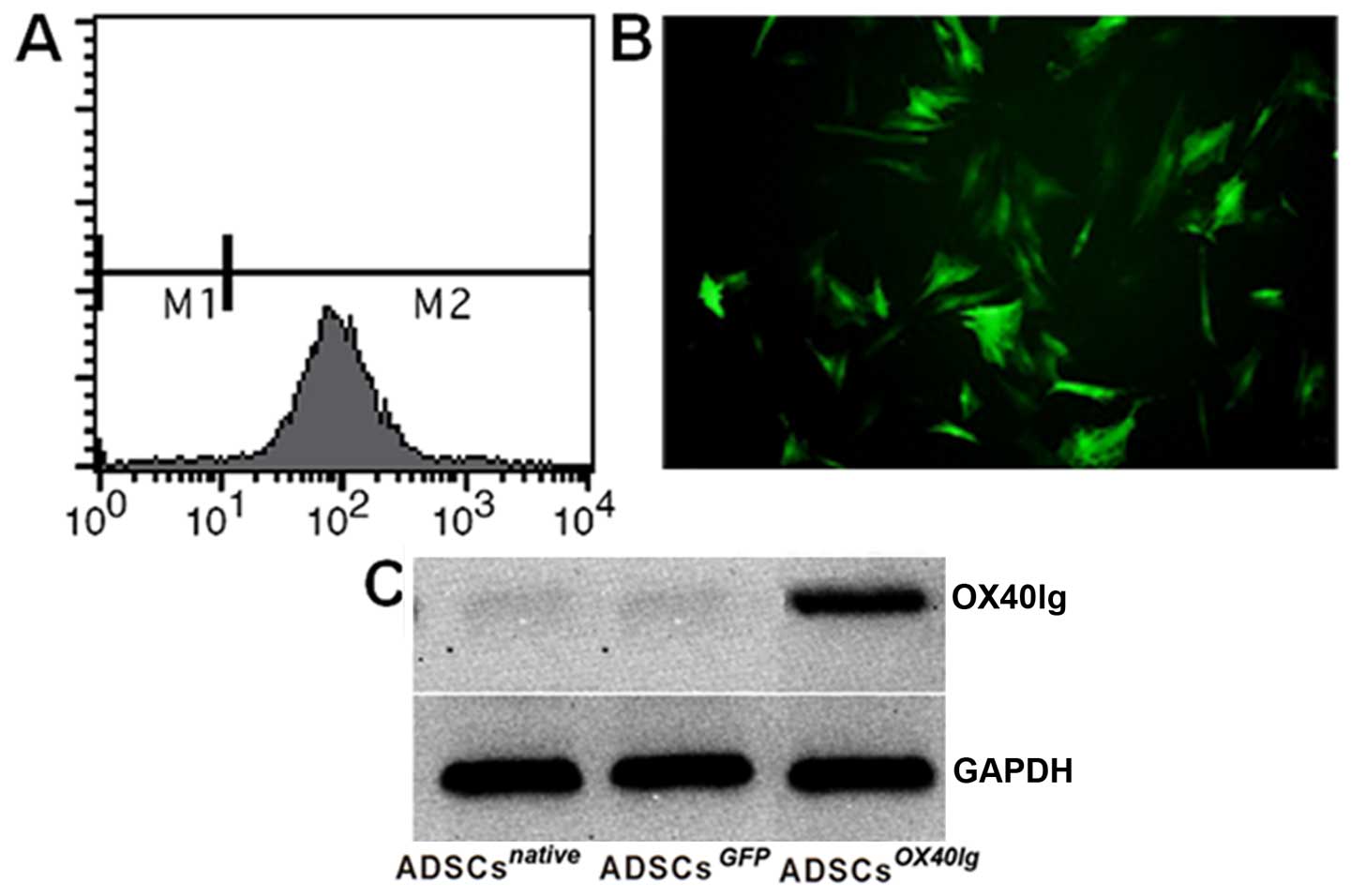

Analysis of nucleofection

To confirm the nucleofection efficiency, the vector

pcDNA3.1/green fluorescent protein (GFP) encoding for GFP was used

and observed with fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Green

fluorescent ADSCsGFP could be observed (Fig. 3A and B). The expression of OX40Ig

in the ADSCs was examined at the protein level. At 48 h

post-transduction, OX40Ig protein was specifically detected in the

ADSCsOX40Ig, but not in the ADSCsGFP and

ADSCsnative (Fig.

3C).

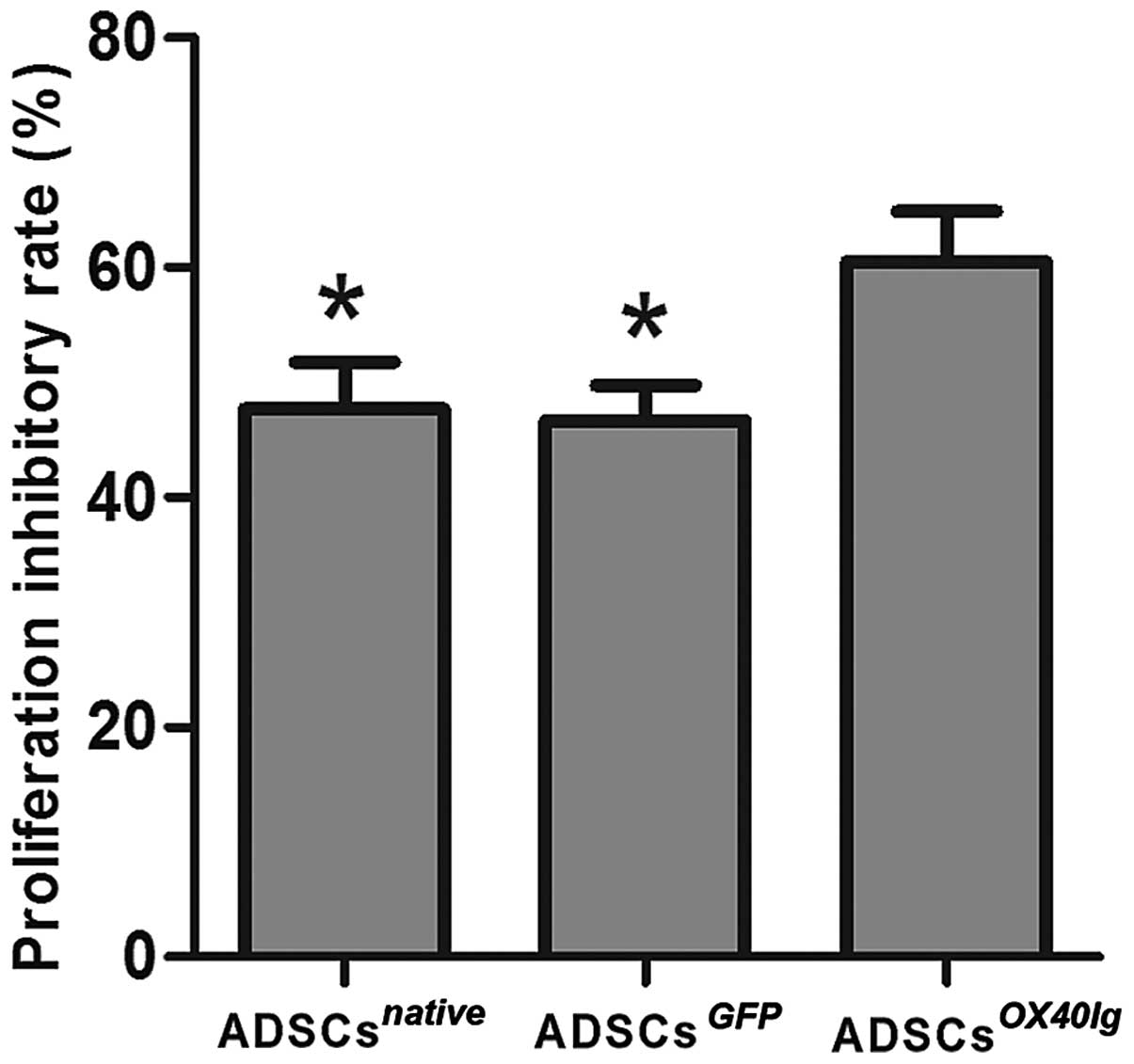

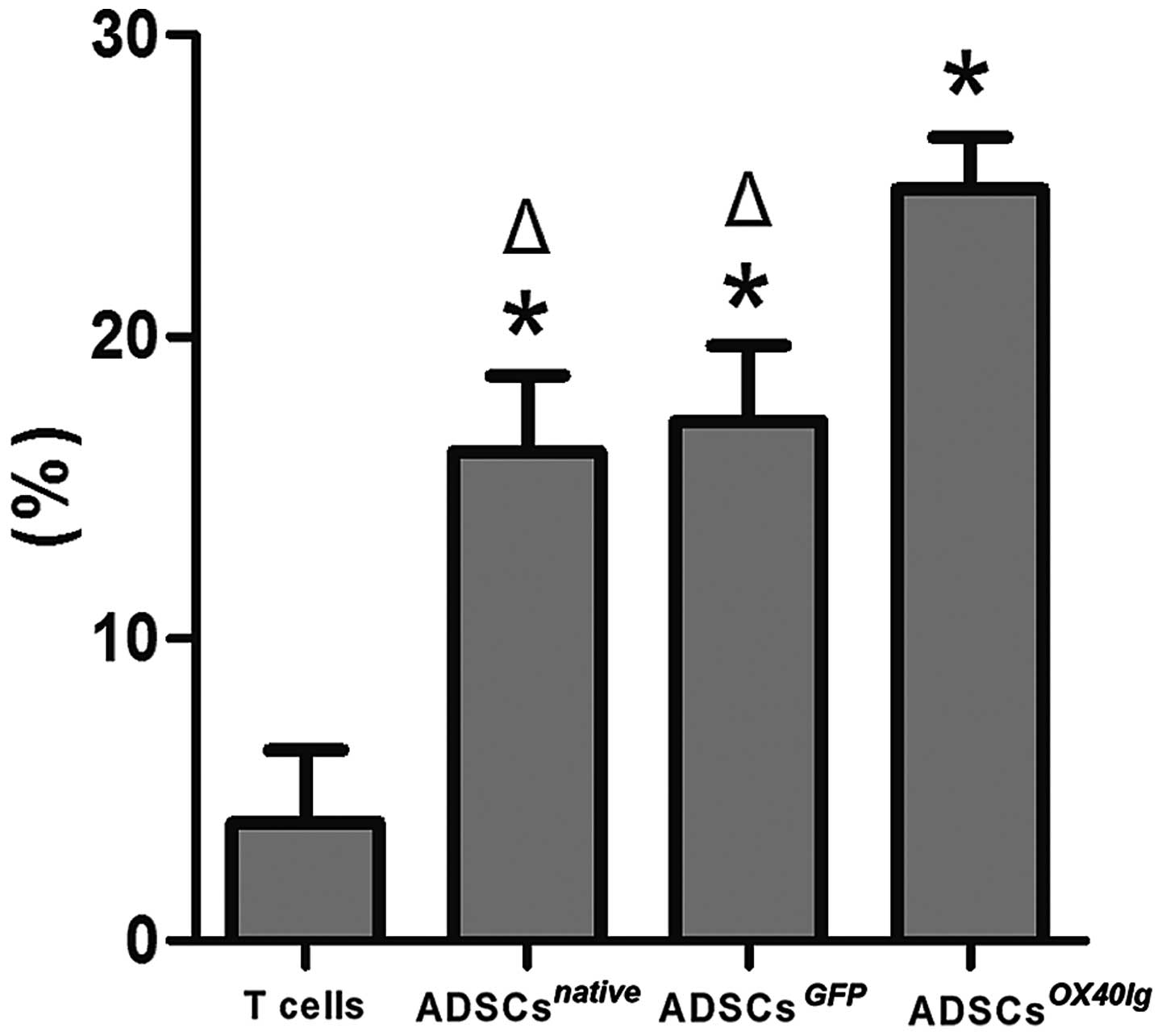

ADSCsOX40Ig suppresses the

proliferation of allostimulated T cells and modulated T cell

subsets in vitro

The data indicated that the ADSCsOX40Ig

group markedly inhibited the allostimulatory T cell proliferation

compared with the ADSCsGFP and ADSCsnative

groups (P<0.01) (Fig. 4). Flow

cytometric analysis of CD4+CD25+ Tregs

revealed that this population was significantly increased in the

ADSCsnative, ADSCsGFP and

ADSCsOX40Ig groups as compared with allogeneic T cells

cultured alone (P<0.01). The percentage of

CD4+CD25+ Tregs significantly increased in

the ADSCsOX40Ig group as compared with

ADSCsnative and ADSCsGFP groups (P<0.01)

(Fig. 5). These results indicate

that OX40Ig genetic modification may substantially enhance the

immunosuppressive ability of ADSCs to allogeneic T cell

proliferation and may increase the number of Tregs.

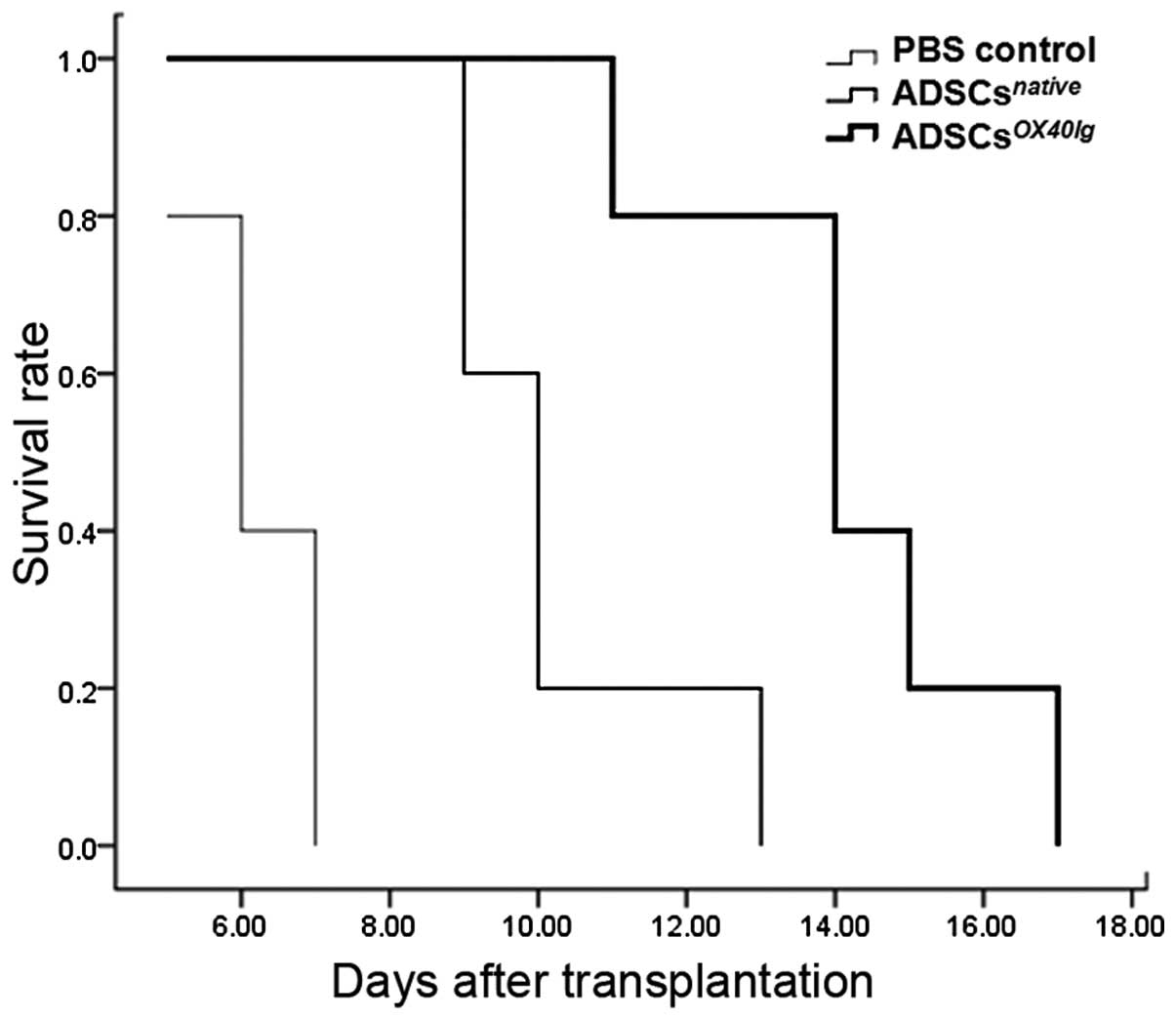

Administration of ADSCsOX40Ig

ameliorates transplanted renal failure and slightly prolongs graft

survival

Renal transplantation induced a substantial increase

in the SCr levels in the PBS control group than in the isografts

control group (P<0.01). The administration of

ADSCsOX40Ig and ADSCsnative significantly

attenuated the increase in the SCr levels compared with the PBS

control group (P<0.01). However, the ADSCsOX40Ig

treated group had significantly lower SCr levels compared with the

ADSCsnative treated group (P<0.05) (Fig. 6). Our results indicated that the

isograft survival was >90 days. The survival of the allografts

in the ADSCsnative treated group (10.2 ± 1.6 days) was

slightly, but significantly prolonged compared to that of the PBS

control group (6.2±0.8 days) (P<0.05). The administration of

ADSCsOX40Ig markeldy improved allograft survival,

increasing the mean graft survival time to 14.2±2.2 days. The

survival time of all recipients is shown in Fig. 7.

Renal histopathological evaluation

To determine the reason for graft failure, we then

evaluated renal morphologies. The allogeneic PBS control group

exhibited the histological characteristics of acute rejection, as

shown by dense parenchymal mononuclear cell infiltration, extensive

tubulitis and interstitial edema. By contrast, these changes were

significantly attenuated (the signs of acute rejection) in the

kidneys from the ADSCsnative- and

ADSCsOX40Ig-treated groups, although mild interstitial

edema and a small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration was

observed, and some tubular dilatation, or some epithelial swelling

and degeneration were present. The kidneys from the isografts

control group lacked the histological signs of rejection.

Consistent with the functional analysis data, the histological

examination also confirmed the beneficial effects of the

administration of ADSCsOX40Ig. Representative light

microscopic findings are shown in Fig. 8.

Production of cytokines related to

rejection or tolerance in allografts

Cytokines are key mediators in the induction and

effector phases of the immune and inflammatory responses in kidney

transplantation. In order to detect the effects of ADSCs on the

level of rejection or tolerance-associated cytokines in allograft

kidneys, we prepared total allograft mRNA for the measurement of

cytokine transcript expression by RT-qPCR. Compared with the

isografts control group, the allogeneic PBS control group exhibited

a significantly increased mRNA expression of IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-10,

TGF-β and Foxp3 in the allografts. Compared with the allogeneic PBS

control group, the ADSCsnative- and

ADSCsOX40Ig-treated groups exhibited a significantly

decreased expression of IFN-γ in the allografts, and there was a

marked downregulation in the IFN-γ mRNA level in the

ADSCsOX40Ig-treated group. Furthermore, compared with

the allogeneic PBS control group, the mRNA expression levels of

IL-10, TGF-β and Foxp3 were significantly increased in the

ADSCsnative- and ADSCsOX40Ig-treated groups

(Fig. 9). A significantly higher

mRNA level of the Treg marker, Foxp3, was observed in the

ADSCsOX40Ig-treated group compared with the

ADSCsnative-treated group (Fig. 9).

Discussion

The main approach designed to reduce graft rejection

has been focused on the development of immunosuppressive agents at

present. In the present study, we investigated the potential

benefits of treatment with ADSCs and OX40Ig-expressing ADSCs on the

modulation of the rejection response in an acute rat renal

transplantation model. Our results indicated that combination of

autologous ADSCs infusion and OX40-OX40L costimulation blockade may

be an intriguing strategy with which to exert a synergistic

immunosuppressive effect and thereby lead to the attenuation of

histological damage caused by acute rejection.

The ease of isolation, the absence of costimulatory

receptors, and their immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory

properties of MSCs have led to the profound idea of developing

genetically engineered MSCs expressing the desired therapeutic

factors as a cell based vector system (20,21). MSCs can be readily transduced with

all the known viral and non-viral vectors and can effectively

overexpress the transgene (22,23). However, the cytogenetic stability

of MSCs following viral transduction needs to be established to the

allay safety issues of malignant transformation. The nucleofection

technology is a safe non-viral electroporation-based transfection

system (24,25). In this study, we modified ADSCs

with the plasmid pcDNA3.1 that can expressed the OX40Ig fusion

protein in eukaryotic expressiion systems by nucleofection. The

transient expression of OX40Ig in ADSCs was obtained. It was proven

that the OX40Ig fusion protein was expressed in ADSCs, and both of

the ADSCsnative and ADSCsOX40Ig significantly

suppressed T cell proliferation, and increased the proportion of

CD4+CD25+ Tregs in allogeneic MLR assays

in vitro, with the ADSCsOX40Ig being more

effective. This indicated that the ADSCsOX40Ig expressed

OX40Ig and had biological function, and exerted synergistic effects

on ADSC-mediated antigen-specific T cell anergy through blockade

OX40/OX40L costimulation signals.

MSCs as a cell therapy have demonstrated efficacy

for GVHD, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis

(RA), multiple sclerosis (MS), type 1 diabetes, myocardial

infarction, thyroditis, different types of neurological disorders

and organ transplantation (26–32). ADSCs were used in clinical trials

as soon as 5 years after their description (14,33) and more than 100 clinical trials

have been reported at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. The first clinical

study in kidney transplantation with autologous MSC treatment was

reported by Perico et al (34) as a safety and feasibility study,

but with limited success. Other very limited studies set up

clinical trials using autologous or even allogeneic MSCs in kidney

transplantation (35,36). Tan et al (37) demonstrated that the use of

autologous MSCs as a replacement for induction therapy resulted in

a lower incidence of acute rejection, decreased risk of

opportunistic infection, and better estimated renal function at 1

year in living related kindey transplantation. In a rat organ

transplant model, Casiraghi et al (38) observed that, in contrast to

post-transplant MSC infusion, pre-transplant MSC infusion induced a

significant prolongation of kidney graft survival by a

Treg-dependent mechanism. Contrary data have also been published

for the rat heart transplantation model, with either accelerated

rejection (39) or prolonged

graft survival (40) obtained

depending on the experimental approach. Therefore, the time point

of injection and the number of cells applied seem to be important

parameters influencing the success of MSC therapy. Our observations

that pre-transplant, intro-transplant, and post-transplant ADSC

administration significantly improved renal function compared with

the PBS control group. This result is in agreement with our

previous study that autologous ADSC ameliorated acute renal damage

undergoing cold I/R injury and improved renal function (17).

However, the single administration of ADSCs is only

practical for a limited number of applications, and is insufficient

to overcome the alloreactive T cell response totally and to achieve

a long-term positive allograft outcome (41). Thus, as gene delivery vehicles,

the localization of ADSCs combined with costimulation blockade may

provide a new opportunity for successful therapy (15,42). In this study, our results revealed

that the administration of OX40Ig gene-modified ADSCs resulted in a

modest, but greater prolongation in the survival time of renal

grafts compared with ADSC monotherapy. Furthermore, renal function

and histological examination revealed that ADSCsOX40Ig

therapy significantly improved renal function and lessened tissue

damage. The present results also indicated that

ADSCsOX40Ig therapy effectively prevented T lymphocyte

infiltration to the grafts. This indicated that acute rejection was

effectively prevented by the intrarenal ADSC immunomodulatory

effect in combination with simultaneous local OX40-OX40L pathway

blockade, which may contribute to a tolerogenic environment.

Infiltrated T cells produce effector cytokines in

situ to recruit additional immune cells that mediate early

graft tissue damage. Blocking the expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines is a rational approach to the immunosuppressive therapy

of graft rejection. Cytokine transcription profiles of intragraft

tissues give us a more precise insight of the immune regulation. In

this study, one mechanism by with ADSCsOX40Ig led to the

suppression of immunity and prolongation of survival involved the

induction of Tregs. Consistent with previous data (41,43), our study demonstrated that the

gene expression profiles in grafts from the PBS group exhibited an

increased expression of genes associated with Th1 cells (IFN-γ),

Th2 cells (IL-4 and IL-10), Th3 cells (TGF-β) and Tregs (Foxp3).

The present study demonstrated that graft survival in the

ADSCsOX40Ig group was enhanced, along with the

significantly decreased mRNA expression of IFN-γ, and the increased

mRNA expression of IL-10, TGF-β and Foxp3. The upregulation of

IL-10 and TGF-β is important for the differentiation and

proliferation of Tregs. Tregs have very important immunoregulatory

effects and play a significant role in the induction of

immunotolerance or the maintenance of immunosuppressive activity

(44). These data provide

evidence that increased allograft survival following

ADSCsOX40Ig administration, at least in part, occurs in

association with the increased intragraft expression of genes

associated with altered T cell differentiation, as well as a shift

from a pro-inflammatory to an anti-inflammatory state. Further

studies are warranted in order to elucidate the signal transduction

pathways through which ADSCsOX40Ig modulate T cells and

prolong allotransplant survival.

Taken together, the results of the present study

demonstrated that the administration of ADSCsOX40Ig was

able to alleviate acute renal allograft rejection and prolong graft

survival by combining the immunomodulatory effects of ADSCs and

ADSCs-mediated intrarenal OX40/OX40L pathway blockade. More

functional assessments are still required if tolerogenic strategy

utilizing ADSCsOX40Ig is to be developed in the near

future.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81470982); the National

Clinical Key Specialty Project Foundation of the Ministry of Health

(grant no. 2013544); and the Tianjin Research Program of

Application Foundation and Advanced Technology (grant nos.

13JCYBJC23000 and 12ZCZDSY02600).

References

|

1

|

Shrestha B, Haylor J and Raftery A:

Historical perspectives in kidney transplantation: an updated

review. Prog Transplant. 25:64–69. 762015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Newell KA: Clinical transplantation

tolerance. Semin Immunopathol. 33:91–104. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Thorp EB, Stehlik C and Ansari MJ: T-cell

exhaustion in allograft rejection and tolerance. Curr Opin Organ

Transplant. 20:37–42. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Waldmann H, Hilbrands R, Howie D and

Cobbold S: Harnessing FOXP3+ regulatory T cells for

transplantation tolerance. J Clin Invest. 124:1439–1445. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kinnear G, Jones ND and Wood KJ:

Costimulation blockade: current perspectives and implications for

therapy. Transplantation. 95:527–535. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

6

|

Kaur D and Brightling C: OX40/OX40 ligand

interactions in T-cell regulation and asthma. Chest. 141:494–499.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jensen SM, Maston LD, Gough MJ, Ruby CE,

Redmond WL, Crittenden M, Li Y, Puri S, Poehlein CH, Morris N, et

al: Signaling through OX40 enhances antitumor immunity. Semin

Oncol. 37:524–532. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kotani A, Hori T, Fujita T, Kambe N,

Matsumura Y, Ishikawa T, Miyachi Y, Nagai K, Tanaka Y and Uchiyama

T: Involvement of OX40 ligand+ mast cells in chronic

GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone

Marrow Transplant. 39:373–375. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zhou YB, Ye RG, Li YJ and Xie CM:

Targeting the CD134−CD134L interaction using anti-CD134

and/or rhCD134 fusion protein as a possible strategy to prevent

lupus nephritis. Rheumatol Int. 29:417–425. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang YL, Li G, Fu YX, Wang H and Shen ZY:

Blockade of OX40/OX40 ligand to decrease cytokine messenger RNA

expression in acute renal allograft rejection in vitro. Transplant

Proc. 45:2565–2568. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Casiraghi F, Remuzzi G and Perico N:

Mesenchymal stromal cells to promote kidney transplantation

tolerance. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 19:47–53. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Marx C, Silveira MD and Beyer Nardi N:

Adipose-derived stem cells in veterinary medicine: characterization

and therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Dev. 24:803–813. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Alipour F, Parham A, Kazemi Mehrjerdi H

and Dehghani H: Equine adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells:

phenotype and growth characteristics, gene expression profile and

differentiation potentials. Cell J. 16:456–465. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Minteer DM, Marra KG and Rubin JP: Adipose

stem cells: biology, safety, regulation, and regenerative

potential. Clin Plast Surg. 42:169–179. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Takahashi T, Tibell A, Ljung K, Saito Y,

Gronlund A, Osterholm C, Holgersson J, Lundgren T, Ericzon BG,

Corbascio M, Kumagai-Braesch M, et al: Multipotent mesenchymal

stromal cells synergize with costimulation blockade in the

inhibition of immune responses and the induction of

Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Stem Cells Transl Med.

3:1484–1494. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Clark JD, Gebhart GF, Gonder JC, Keeling

ME and Kohn DF: Special Report: the 1996 guide for the care and use

of laboratory animals. ILAR J. 38:41–48. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang YL, Li G, Zou XF, Chen XB, Liu T and

Shen ZY: Effect of autologous adipose-derived stem cells in renal

cold ischemia and reperfusion injury. Transplant Proc.

45:3198–3202. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Redmond WL, Triplett T, Floyd K and

Weinberg AD: Dual anti-OX40/IL-2 therapy augments tumor

immunotherapy via IL-2R-mediated regulation of OX40 expression.

PLoS One. 7:e344672012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Seifert M, Stolk M, Polenz D and Volk HD:

Detrimental effects of rat mesenchymal stromal cell pre-treatment

in a model of acute kidney rejection. Front Immunol. 3:2022012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wu H, Ye Z and Mahato RI: Genetically

modified mesenchymal stem cells for improved islet transplantation.

Mol Pharm. 8:1458–1470. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li J, Ezzelarab MB, Ayares D and Cooper

DK: The potential role of genetically-modified pig mesenchymal

stromal cells in xenotransplantation. Stem Cell Rev. 10:79–85.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

22

|

Stiehler M, Duch M, Mygind T, Li H,

Ulrich-Vinther M, Modin C, Baatrup A, Lind M, Pedersen FS and

Bünger CE: Optimizing viral and non-viral gene transfer methods for

genetic modification of porcine mesenchymal stem cells. Adv Exp Med

Biol. 585:31–48. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fülbier A, Schnabel R, Michael S, Vogt PM,

Strauß S, Reimers K and Radtke C: Successful nucleofection of rat

adipose-derived stroma cells with ambystoma mexicanum epidermal

lipoxygenase (AmbLOXe). Stem Cell Res Ther. 5:1132014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Fakiruddin KS, Baharuddin P, Lim MN,

Fakharuzi NA, Yusof NA and Zakaria Z: Nucleofection optimization

and in vitro anti-tumourigenic effect of TRAIL-expressing human

adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cancer Cell Int.

14:1222014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Copland IB, Qayed M, Garcia MA, Galipeau J

and Waller EK: Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells from patients

with acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease deploy normal

phenotype, differentiation plasticity, and immune-suppressive

activity. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 21:934–940. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang Q, Qian S, Li J, Che N, Gu L, Wang Q,

Liu Y and Mei H: Combined transplantation of autologous

hematopoietic stem cells and allogenic mesenchymal stem cells

increases T regulatory cells in systemic lupus erythematosus with

refractory lupus nephritis and leukopenia. Lupus. 24:1221–1226.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

De Bari C: Are mesenchymal stem cells in

rheumatoid arthritis the good or bad guys? Arthritis Res Ther.

17:1132015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Xiao J, Yang R, Biswas S, Qin X, Zhang M

and Deng W: Mesenchymal stem cells and induced pluripotent stem

cells as therapies for multiple sclerosis. Int J Mol Sci.

16:9283–9302. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kong D, Zhuang X, Wang D, Qu H, Jiang Y,

Li X, Wu W, Xiao J, Liu X, Liu J, et al: Umbilical cord mesenchymal

stem cell transfusion ameliorated hyperglycemia in patients with

type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Lab. 60:1969–1976. 2014.

|

|

30

|

Chullikana A, Majumdar AS, Gottipamula S,

Krishnamurthy S, Kumar AS, Prakash VS and Gupta PK: Randomized,

double-blind, phase I/II study of intravenous allogeneic

mesenchymal stromal cells in acute myocardial infarction.

Cytotherapy. 17:250–261. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Suksuphew S and Noisa P: Neural stem cells

could serve as a therapeutic material for age-related

neurodegenerative diseases. World J Stem Cells. 7:502–511. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lim MH, Ong WK and Sugii S: The current

landscape of adipose-derived stem cells in clinical applications.

Expert Rev Mol Med. 16:e82014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Perico N, Casiraghi F, Introna M, Gotti E,

Todeschini M, Cavinato RA, Capelli C, Rambaldi A, Cassis P, Rizzo

P, et al: Autologous mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney

transplantation: a pilot study of safety and clinical feasibility.

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 6:412–422. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

34

|

Perico N, Casiraghi F, Gotti E, Introna M,

Todeschini M, Cavinato RA, Capelli C, Rambaldi A, Cassis P, Rizzo

P, et al: Mesenchymal stromal cells and kidney transplantation:

pretransplant infusion protects from graft dysfunction while

fostering immunoregulation. Transpl Int. 26:867–878. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Peng Y, Ke M, Xu L, Liu L, Chen X, Xia W,

Li X, Chen Z, Ma J, Liao D, et al: Donor-derived mesenchymal stem

cells combined with low-dose tacrolimus prevent acute rejection

after renal transplantation: a clinical pilot study.

Transplantation. 95:161–168. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Reinders ME, de Fijter JW, Roelofs H,

Bajema IM, de Vries DK, Schaapherder AF, Claas FH, van Miert PP,

Roelen DL, van Kooten C, et al: Autologous bone marrow-derived

mesenchymal stromal cells for the treatment of allograft rejection

after renal transplantation: results of a phase I study. Stem Cells

Transl Med. 2:107–111. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Tan J, Wu W, Xu X, Liao L, Zheng F,

Messinger S, Sun X, Chen J, Yang S, Cai J, et al: Induction therapy

with autologous mesenchymal stem cells in living-related kidney

transplants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 307:1169–1177.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Casiraghi F, Azzollini N, Todeschini M,

Cavinato RA, Cassis P, Solini S, Rota C, Morigi M, Introna M,

Maranta R, et al: Localization of mesenchymal stromal cells

dictates their immune or proinflammatory effects in kidney

transplantation. Am J Transplant. 12:2373–2383. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Inoue S, Popp FC, Koehl GE, Piso P,

Schlitt HJ, Geissler EK and Dahlke MH: Immunomodulatory effects of

mesenchymal stem cells in a rat organ transplant model.

Transplantation. 81:1589–1595. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Popp FC, Eggenhofer E, Renner P, Slowik P,

Lang SA, Kaspar H, Geissler EK, Piso P, Schlitt HJ and Dahlke MH:

Mesenchymal stem cells can induce long-term acceptance of solid

organ allografts in synergy with low-dose mycophenolate. Transpl

Immunol. 20:55–60. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Kato T, Okumi M, Tanemura M, Yazawa K,

Kakuta Y, Yamanaka K, Tsutahara K, Doki Y, Mori M, Takahara S and

Nonomura N: Adipose tissue-derived stem cells suppress acute

cellular rejection by TSG-6 and CD44 interaction in rat kidney

transplantation. Transplantation. 98:277–284. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Yang D, Wang LP, Zhou H, Cheng H, Bao XC,

Xu S, Zhang WP and Wang JM: Inducible costimulator gene-transduced

bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate the severity

of acute graft-versus-host disease in mouse models. Cell

Transplant. 24:1717–31. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Wang YL, Tang ZQ, Gao W, Jiang Y, Zhang XH

and Peng L: Influence of Th1, Th2, and Th3 cytokines during the

early phase after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc.

35:3024–3025. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Lee JH, Jeon EJ, Kim N, Nam YS, Im KI, Lim

JY, Kim EJ, Cho ML, Han KT and Cho SG: The synergistic

immunoregulatory effects of culture-expanded mesenchymal stromal

cells and CD4(+)25(+)Foxp3+ regulatory T cells on skin allograft

rejection. PLoS One. 8:e709682013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|