Introduction

Changing life styles in China have contributed to a

rise in atherosclerosis resulting in coronary heart disease (CHD),

causing serious morbidity and mortality (1). Growing evidence has revealed that

long-lasting and low-grade inflammation is a key cause of the

progression of atherosclerosis (2,3).

The abnormal proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs)

and their expression of various pro-inflammatory cytokines such as

interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) play an

important role in the process of inflammation within

atherosclerotic plaques (4,5).

Angiotensin II (AngII), which is increased significantly in the

serum of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), may promote

the process of atherosclerosis and plaque rupture by recruiting

monocytes, activating macrophages, producing pro-inflammatory

factors and causing oxidative stress (6,7).

More importantly, these pro-atherosclerotic effects of AngII do not

depend on the elevation of systolic blood pressure.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ

(PPAR-γ), a member of the nuclear hormone family, plays a critical

role in regulating glucose homeostasis and adipose metabolism.

After activation, PPAR-γ binds to specific PPAR response elements

(PPREs) and then regulates the transcription of its target genes

(8,9). In recent years growing evidence has

shown that the activity of PPAR-γ may potentially downregulate

inflammatory responses caused by various proinflammatory stimuli

(10–12). Moreover, PPAR-γ also participates

in the production of AngII-induced proinflammatory factors by

VSMCs, and thiazolidinediones (TZDs), synthetic PPAR-γ agonists,

may significantly inhibit this inflammatory effect (13). PPAR-γ also plays an important role

in regulating VSMC proliferation which can significantly affect the

process of cardiac fibrosis (14).

Oxidative stress, characterized by the

overproduction of intercellular reactive oxygen species (iROS), can

trigger multiple pathological responses related to atherosclerosis,

including oxidation of lipids and proteins, proliferation and

migration of VSMCs, and overexpression of proinflammatory cytokines

(15). Common risk factors for

atherosclerosis such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, obesity

and smoking may enhance the production of ROS in VSMCs. NADPH

activation is the principle cause of ROS production by VSMCs

(16). Previous studies have

revealed that inhibition of the activation of NADPH reduced

high-fat diet-induced increase in the area of atherosclerostic

plaques in ApoE−/− mice (17,18), compared with the control

group.

Curcumin (Cur) is a natural polyphenol and is the

principal curcuminoid present in Curcuma longa. Cur is

responsible for the yellow color of turmeric and has been used in

herbal remedies to treat inflammation- and infection-related

diseases in China and India since ancient times (19). Cur has many pharmacological

effects including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anti-microbial,

anti-proliferative, neuroprotective and cardio-protective

activities (5,14,20,21). Recently, some studies have found

that Cur attenuates the progression of atherosclerosis by

inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and ROS production,

in vivo and in vitro (5,22).

Our previous study found that Cur inhibited LPS-induced

inflammation through a TLR4-mediated and ROS-relative signaling

pathway in VSMCs (5).

Furthermore, Cur attenuates cardiac fibrosis by elevating PPAR-γ

activation (14). However, the

molecular mechanisms underlying the anti-inflammatory and

anti-proliferative effects of Cur in AngII-stimulated VSMCs are not

well known.

Therefore, our present study aimed to ascertain

whether Cur can suppress AngII-induced expression of

pro-inflammatory mediators and whether its cardioprotective effect

is partially dependent on PPAR-γ activity and a reduction in

oxidative stress.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal

bovine serum (FBS) were provided by Gibco-BRL (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Curcumin (purity over 98%), penicillin, streptomycin, Tris, EDTA,

2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluororescein diacetate (DCFH-DA),

diphenyleneiodonium (DPI),

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT),

GW9662, and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) were purchased

from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The following primary

antibodies were used: PPAR-γ (GW21258-50UG; Sigma Chemical Co.),

p47phox (4312S; Cell Signaling Technology., Inc., Danvers, MA,

USA), inducible NO synthase (iNOS; xy-2977; Xin Yu Biotech Co.,

Shanghai, China) and histone (orb48770; Biorbyt Ltd., Cambridge,

UK). TranZol, TransStrat Green qPCR SuperMix, EasyScript Reverse

Transcriptase and the β-actin antibody (VSC47778; www.biomart.cn) were purchased from TransGen

Biotechnology (Beijing, China). IL-6 and TNF-α enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits were purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA).

VSMC culture

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of the Laboratory Animal Institute in the School of

Medicine at Zhengzhou University, and carried out in strict

accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH

publication no. 85–23, revised 1996). Male Sprague-Dawley rats

(weighing 150–180 g) were purchased from the Laboratory Animal

Institute in the School of Medicine at Zhengzhou University. VSMCs

were isolated from the thoracic aorta of rats, according to a

previously described method (23). Cells were cultured in DMEM

containing 20% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml

streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at

37°C. Cells that were between passage 3 and 10 were used for all

experiments. Cells at 80–90% confluence in culture dishes were

growth-arrested by serum starvation for 16 h.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were planted at a density of 6,000 cells/well

in 96-well plates. An MTT reduction assay and cell count

experiments were used to determine the amount of cell

proliferation. After the indicated treatments, the medium was

removed and the cells were incubated with MTT (5 mg/ml) for 4 h at

37°C. The dark blue formazan crystals that formed in intact cells

were solubilized with DMSO, and then the absorbance was measured at

490 nm on a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Cell

count experiments were performed as previously described. Cells

were counted by a hemocytometer using light microscopy.

Real-time reverse-transcriptase

polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted by TransZol reagent

(TransGen Biotechnology). The quality of total mRNA was measured by

denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis containing 1.5%

formaldehyde. Total RNA concentration and purity were determined

using UV-Vis spectroscopy with the Bio-Rad SmartSpec 5000 system

(Bio-Rad). cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA in a

20 µl reaction using oligo(dT)18 primers and

TransScript™ reverse transcriptase (TransGen Biotechnology).

Primers for rat PPAR-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS, p47phox and

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydroge-nase (GAPDH) were designed

using Beacon designer v6.0 software (Premier Biosoft, Palo Alto,

CA, USA) and are listed in Table

I. GAPDH was used as an endogenous control. mRNA levels of

PPAR-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, iNOS and GAPDH were measured using real-time

PCR on the ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection PCR system (Applied

Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A melting point dissociation

curve was used to confirm that only a single PCR product was

obtained. Results were expressed as fold difference relative to the

level of GAPDH by the 2−ΔΔCT method.

| Table IPrimers used for real-time PCR

analysis. |

Table I

Primers used for real-time PCR

analysis.

| Gene | Oligonucleotide

primer sequences (5′-3′) |

|---|

| IL-6 | F:

GAGAAAAGAGTTGTGCAATGGC |

| R:

ACTAGGTTTGCCGAGTAGACC |

| TNF-α | F:

TCCCAACAAGGAGGAGAAGT |

| R:

TGGTATGAAGTGGCAAATCG |

| p47phox | F:

GAGACATACCTGACGGCCAAAGA |

| R:

AGTCAGCGATGGCCCGATAG |

| iNOS | F:

CCACGCTCTTCTGTCTACTGAAC |

| R:

ACGGGCTTGTCACTCGAG |

| GADPH | F:

ATCGGCAATGAGCGGTTCC |

| R:

AGCACTGTGTTGGCATAGAGG |

Western blot analysis

Lysates of ~6×106 VSMCs were prepared

using 200 µl ice-cold lysis buffer (pH 7.4) (50 mmol/l

HEPES, 5 mmol/l EDTA, 100 mmol/l NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, protease

inhibitor cocktail; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in the presence of

phosphatase inhibitors (50 mmol/l sodium fluoride, 1 mmol/l sodium

orthovanadate, 10 mmol/l sodium pyrophosphate, 1 nmol/l

microcystin). The nuclear PPAR-γ protein was extracted using a

Pierce NE-PER kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The protein

concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit. Samples

underwent 10 or 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and were transferred onto a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in a semi-dry system, which was

blocked with 5% fat-free milk in TBST buffer (20 mmol/l Tris-HCl,

137 mmol/l NaCl and 0.1% Tween-20), and incubated with primary

antibodies recognizing PPAR-γ (1:400), iNOS (1:500), p47phox

(1:400), histone (1:1,000), and β-actin (1:2,000), respectively, in

TBST buffer overnight, washed and incubated with secondary

antibodies for 90 min. The optical density of the bands was scanned

and quantified using a Gel-Pro Analyzer v4.0 (Media Cybernetics LP,

Silver Spring, MD, USA). β-actin was used as an endogenous control.

Data were normalized to β-actin levels.

Enzyme-linked immunoassay for cytokines

and chemokines

VSMCs were cultured into 6-well plates at

5×106 cells/well and incubated with Cur (5, 10 and 20

µmol/l) (14) with or

without AngII (10−7 mol/l) for 24 h. Cells were

pretreated with the PPAR-γ antagonist GW9662 (10 µmol/l) and

the NADPH oxidase inhibitor DPI (25 µmol/l) for 1 h, and

then stimulated with AngII (10−7 mol/l) for another 24

h. The amounts of TNF-α and IL-6 in the supernatants were measured

by ELISA according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of nitrite

The Griess reaction was used to determine the level

of nitrite, a stable precursor of NO (24). Fifty microliters of the culture

supernatant was mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent (0.1%

naphthyl-ethylenediamine, 1% sulfanylamide and 2.5% phosphoric

acid). Absorbance was measured on a microplate reader at 540 nm,

using a calibration curve with sodium nitrite standards.

Intracellular ROS assay

The level of intracellular ROS was measured using

the DCFH-DA method, based on the ROS-dependent oxidation of DCFH to

the highly fluorescent DCF. DCFH was dissolved in methanol at 10

mmol/l and then diluted by a factor of 500 in Hank's balanced salt

solution (HBSS) to give a final DCFH concentration of 20

µmol/l. The cells were incubated with DCFH-DA for 1 h and

then treated with HBSS containing Cur (5, 10 or 20 µmol/l)

or AngII (10−7 mol/l) for another 100 min. The

fluorescence was immediately measured using 485 nm for excitation

and 528 nm for emission on the iMark™ microplate absorbance reader

(Bio-Rad).

Stable free radical scavenging

activity

Stable free radical scavenging activity was detected

using the method reported by Jeong et al (25). Briefly, 100 µmol/l of DPPH

radical solution was dissolved in 100% ethanol. The mixture was

shaken vigorously and allowed to stand for 10 min in the dark. The

test materials (100 µl each) were added to 900 µl of

the DPPH radical solution. After incubation at room temperature for

30 min, the absorbance at 517 nm was measured using the SPECTRA

(shell) reader.

Statistical analysis

The significance between groups was analyzed using

ANOVA, and the difference between each of the 2 groups was detected

using the post hoc test using 'Statistic version 8.0' (Statsoft

Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) software. Data are presented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD). A value of P<0.05 was considered to be

statistically significant.

Results

Cur inhibits IL-6 and TNF-α expression in

AngII-stimulated VSCMs

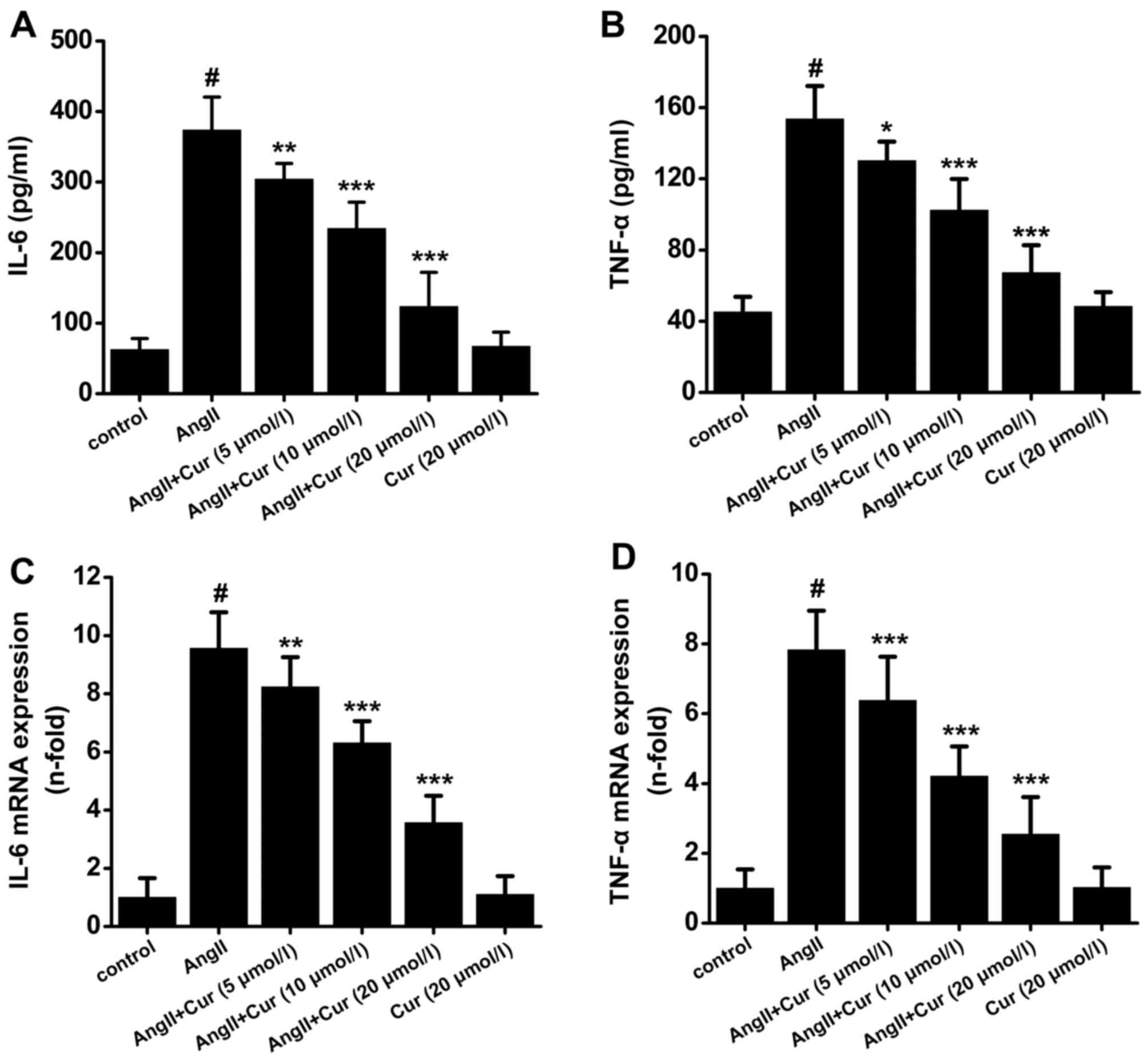

VSMCs express a number of pro-inflammatory cytokines

in response to different stimuli, which can dramatically promote

the progression of atherosclerotic plaques. As shown in Fig. 1, stimulation of VSMCs with AngII

(10−7 mol/l) for 24 h caused a significant increase in

the production of IL-6 and TNF-α. However, pretreatment with Cur

attenuated AngII-induced production of IL-6 and TNF-α in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

1A and B). Moreover, Cur also dose-dependently decreased the

mRNA expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in AngII-stimulated VSMCs

(Fig. 1C and D). Treatment with

Cur (20 µmol/l) did not affect the expression of IL-6 and

TNF-α (Fig. 1).

Cur attenuates AngII-induced NO

production and iNOS expression

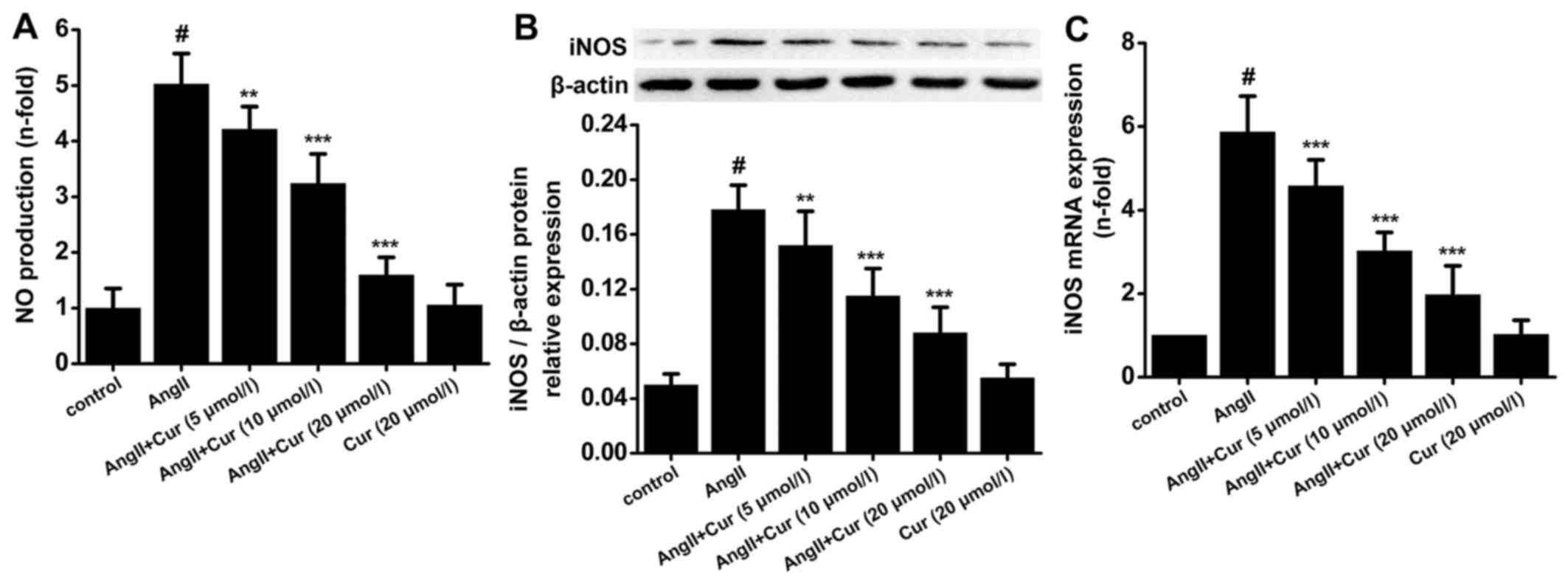

Cur markedly attenuated AngII-induced NO production

in a concentration-dependent manner, but did not change NO

production in the absence of AngII stimulation (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, AngII

significantly increased the protein and mRNA expression of iNOS in

VSMCs, which was concentration-dependently attenuated by Cur.

Treating VSMCs with only Cur had no affect on the expression of

iNOS mRNA and protein (Fig. 2B and

C). These results indicated that Cur attenuated AngII-induced

NO production in VSMCs, which was partly due to inhibition of iNOS

activity.

Cur inhibits AngII-induced proliferation

of VSMCs

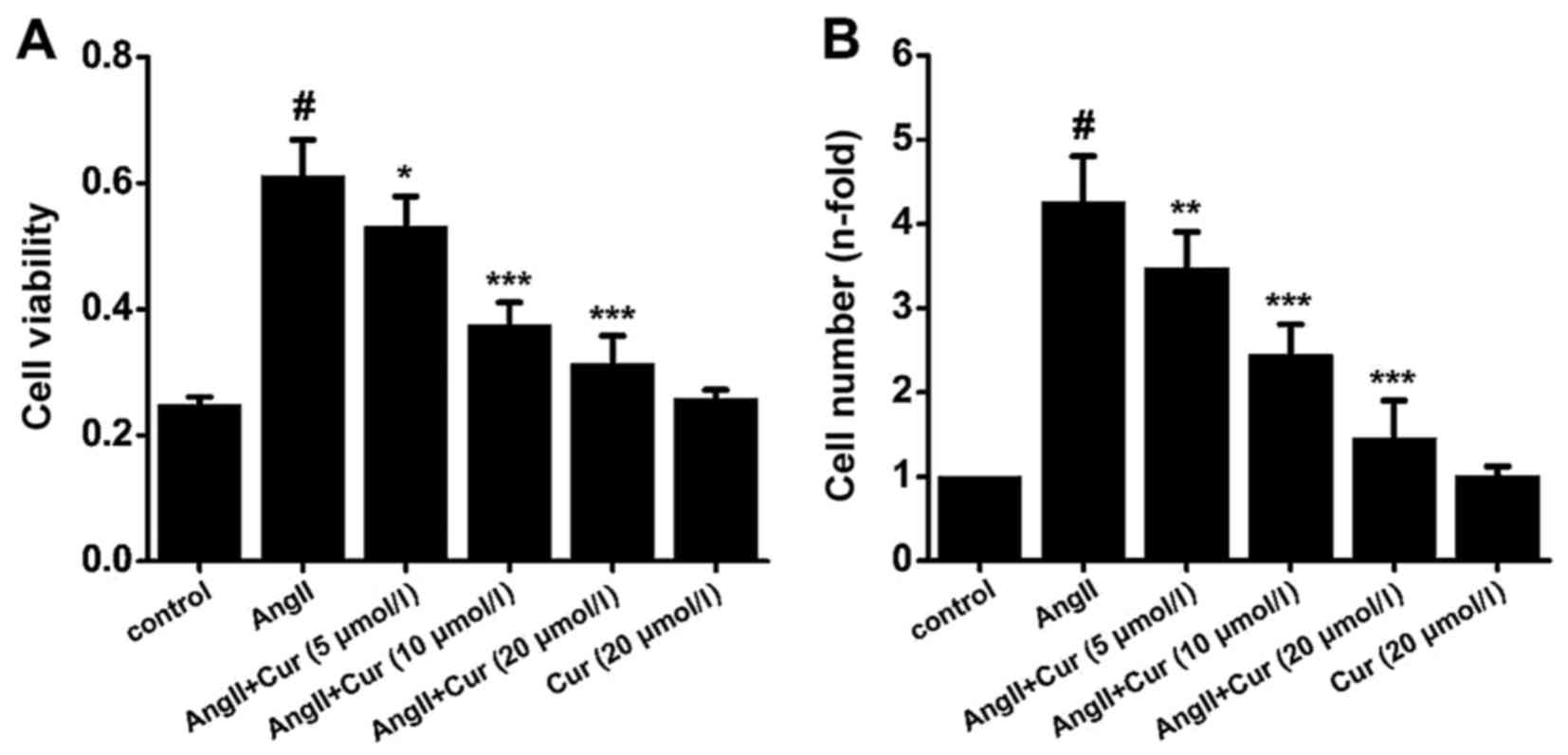

As shown in Fig.

3, treating VSMCs with AngII (10−7 mol/l) for 24 h

significantly increased their proliferation, while pretreating the

cells with Cur (5, 10 and 20 µmol/l) suppressed this effect.

However, treatment with Cur (20 µmol/l) alone did not affect

the proliferation of VSMCs (Fig.

3).

Cur reduces AngII-induced free radical

production in VSMCs

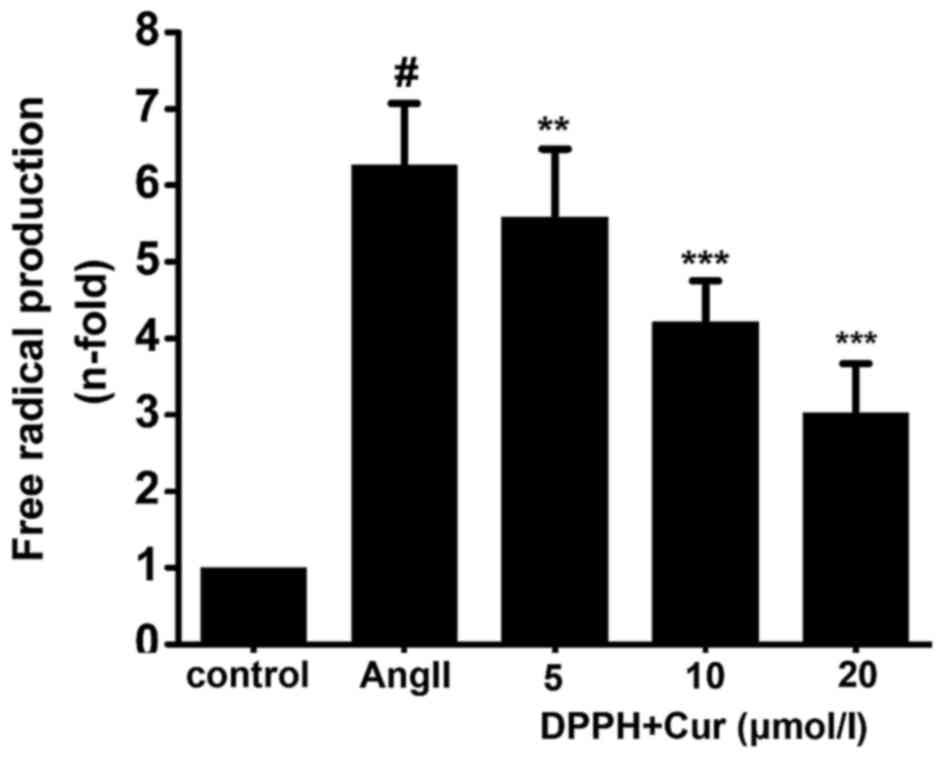

The free radical scavenging activity of Cur in

AngII-stimulated VSMCs was measured using the DPPH reduction assay.

Cur concentration-dependently scavenged the DPPH free radical

caused by ROS in the AngII-stimulated VSMCs (Fig. 4). The results indicated that Cur

exhibited free radical scavenging activity in the AngII-stimulated

VSMCs.

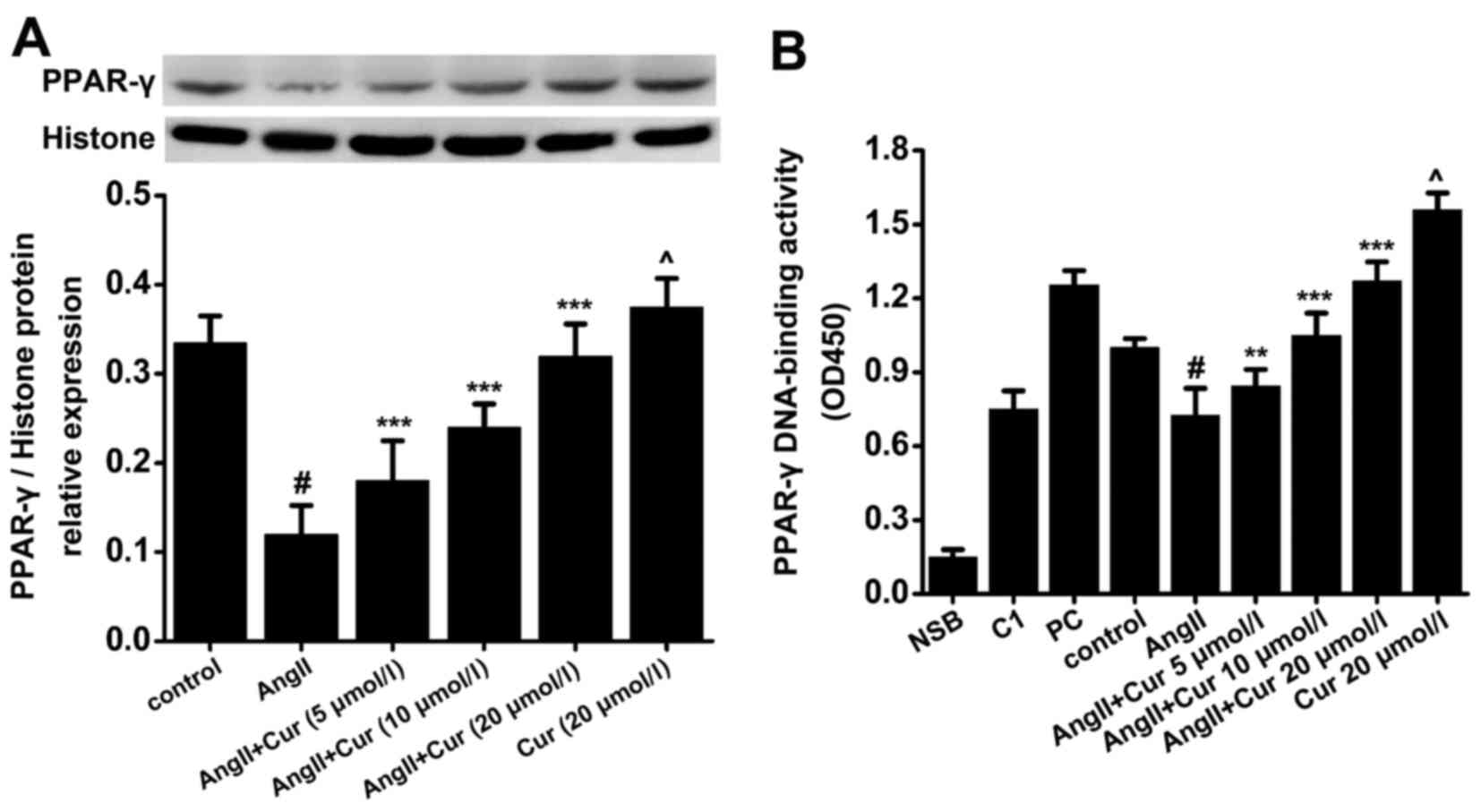

Cur elevates the expression and activity

of PPAR-γ in AngII-stimulated VSMCs

To evaluate the expression and translocation of

PPAR-γ into the nucleus, nuclear protein was extracted and analyzed

by western blot analysis and DNA-binding assay. As shown in

Fig. 4, treating the cells with

AngII (10−7 mol/l) for 24 h markedly decreased the

expression of PPAR-γ in the nucleus and blocked its ability to bind

the DNA response element PPRE. However, pretreating the cells with

Cur significantly increased both PPAR-γ translocation and bound

PPRE in a concentration manner, compared with the AngII-treated

cells (Fig. 5). Moreover,

exposure to Cur (20 µmol/l) alone for 24 h caused an

increase in the nuclear expression and activity of PPAR-γ in the

VSMCs, compared with the control cells (Fig. 5). These results indicated that Cur

may be a potential promoter of PPAR-γ activity in AngII-stimulated

VSMCs.

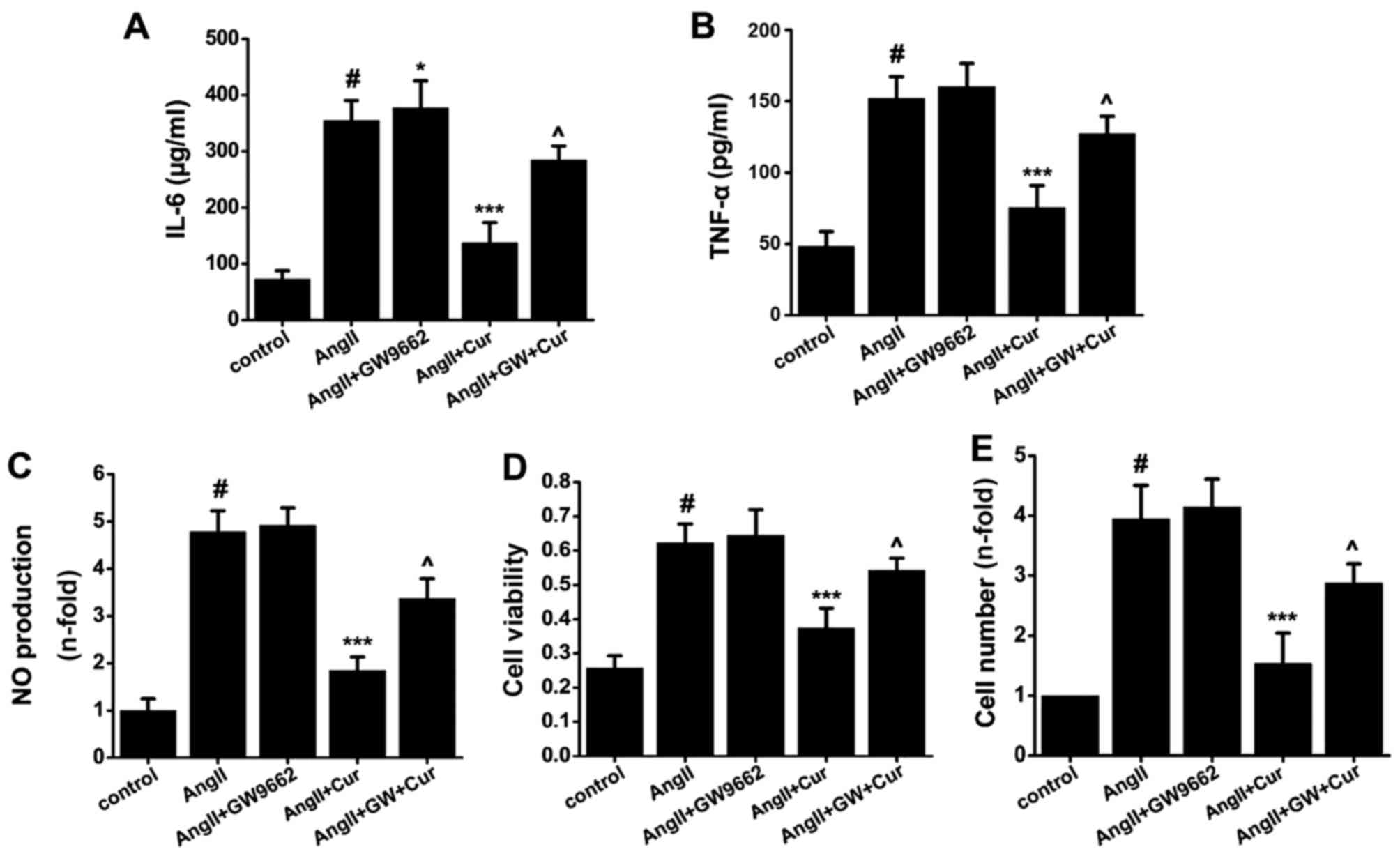

Relationship between PPAR-γ and the

anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effect of Cur in

VSMCs

To evaluate whether the anti-inflammatory and

anti-proliferative effects of Cur are dependent upon PPAR-γ, VSMCs

were pretreated with GW9662 (10 µmol/l), an antagonist of

PPAR-γ, for 1 h, treated with Cur (20 µmol/l) for 1 h, and

then exposed to AngII (10−7 mol/l) for another 24 h. As

shown in Fig. 6, compared with

the control cells, AngII significantly increased the production of

IL-6, TNF-α and NO (Fig. 6A–C),

but this was significantly attenuated by Cur treatment. The PPAR-γ

antagonist GW9662 significantly reversed the inhibitory effect of

Cur on the AngII-induced inflammation in VSMCs (Fig. 6A–C). As shown in Fig. 6, Cur significantly inhibited

AngII-induced proliferation of VSMCs, which was reversed by

pretreatment with GW9662 (Fig. 6D and

E). The results suggest that the activation of PPAR-γ plays a

key role in Cur-mediated suppression of inflammatory factor

production. However, compared with AngII and Cur, pretreating the

cells with GW9662 to inhibit the activity of PPAR-γ did not

completely suppress the anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative

effects of Cur in AngII-stimulated VSMCs, which suggests that other

PPAR-γ-independent molecular mechanisms may partially contribute to

these effects.

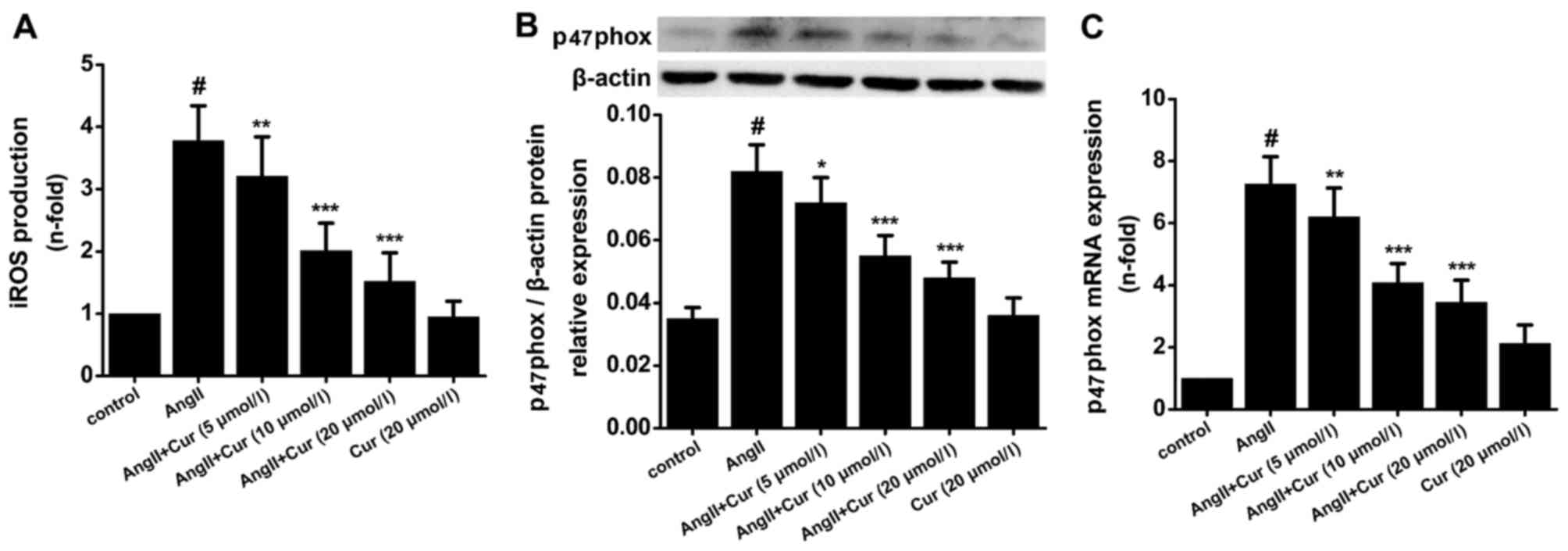

Cur suppresses AngII-induced iROS

production and p47phox expression in VSMCs

The increase in iROS during inflammation causes

various pathological responses such as the expression of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, proliferation of VSMCs, and oxidation

of lipids, which promotes the progression of atherosclerosis.

According to our data, treating VSMCs with AngII (10−7

mol/l) for 24 h significantly increased iROS production, and

pretreatment with Cur concentration-dependently attenuated this

effect (Fig. 7A). p47phox is an

important component of NAPDH oxidase which is the main source of

iROS production in VSMCs. As shown in Fig. 7, Cur concentration-dependently

suppressed AngII-induced expression of p47phox mRNA and protein

(Fig. 7B and C).

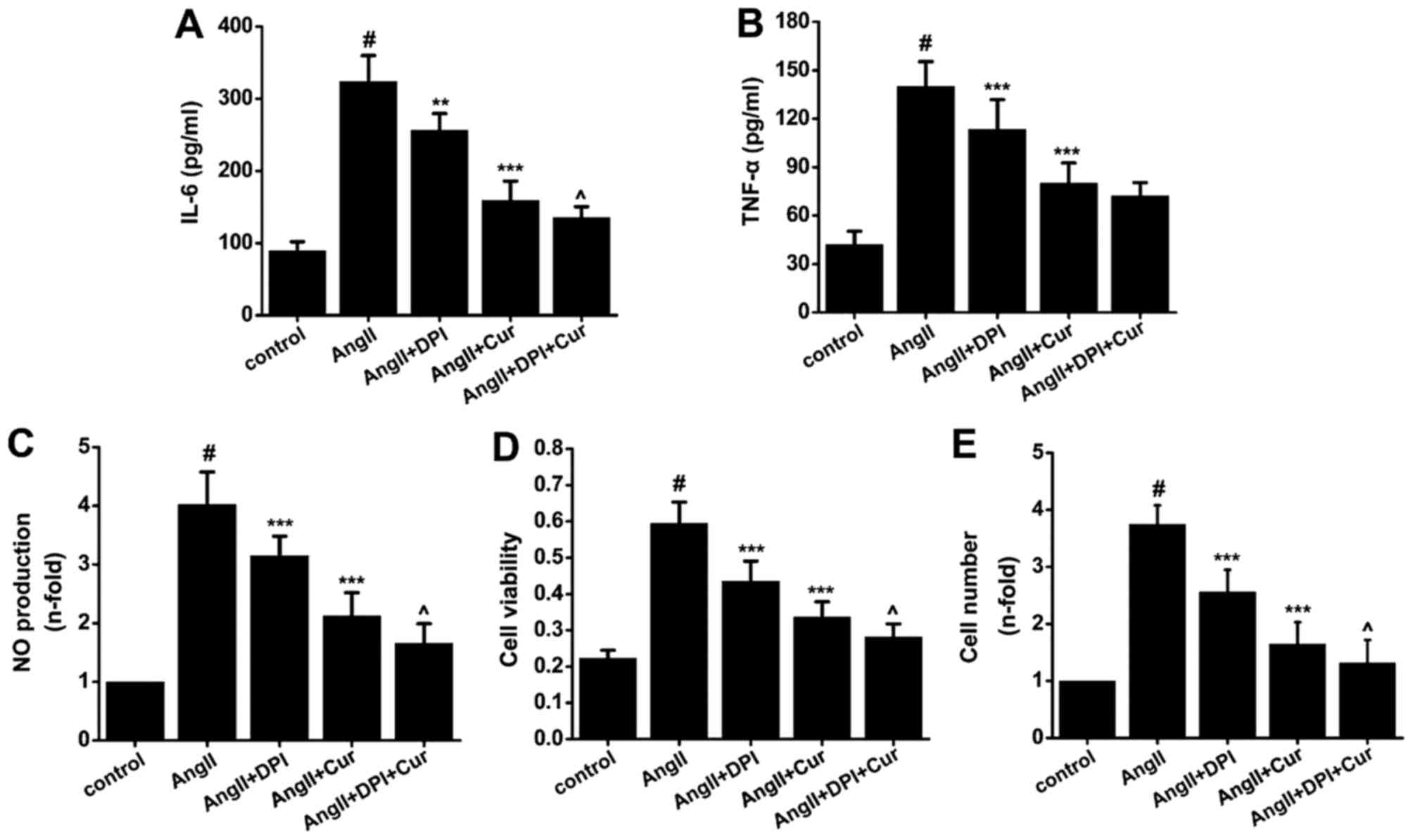

Relationship between oxidative stress and

the anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects of Cur on

VSMCs

To evaluate whether the increase in iROS was related

to the anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effect of Cur in

VSMCs, cells were pretreated with or without DPI (25

µmol/l), an antagonist of NADPH oxidase, for 1 h before

treatment with Cur (20 µmol/l) for 1 h, and then incubated

with AngII (10−7 mol/l) for 24 h. Our data indicated

that Cur and DPI both partially inhibited AngII-induced expression

of IL-6 (Fig. 8A), TNF-α

(Fig. 8B) and NO (Fig. 8C) in VSMCs. Pretreatment with a

combination of Cur and DPI synergistically inhibited AngII-induced

inflammation in VSMCs. Proliferation of VSMCs was also decreased

when the cells were pretreated with Cur and DPI (Fig. 8D and E). These results suggest

that Cur inhibits AngII-induced inflammation and proliferation in

VSMCs partly through suppressing NADPH oxidase-mediated iROS.

Discussion

In the present study, we observed that Cur

concentration-dependently suppressed AngII-induced production of

TNF-α, IL-6 and NO and inhibited the proliferation of VSMCs in

vitro. Our results indicated that the inhibitory effect of Cur

on AngII-induced inflammation and proliferation of VSMCs was partly

dependent on enhancing PPAR-γ activity and reducing NADPH-mediated

iROS production. These findings show a novel relationship between

the anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effect of Cur and

PPAR-γ activation and oxidative response in AngII-induced VSMCs,

which enables a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of

the beneficial effect of Cur on atherosclerosis.

Although atherosclerosis is regarded as a complex

pathological disease, the long-lasting and low-grade inflammatory

response within the arterial walls is a critical factor that

enhances the progression of atherosclerosis and plaque instability

(3). IL-6, which is elevated in

the serum of patients with ACS, is a potential pro-inflammatory

factor as it increases the release of fibrinogen and promotes

platelet aggregation (26). TNF-α

enhances the progression of atherosclerosis and this process

depends upon the induction of endothelium dysfunction, inflammatory

cytokine production, and the increased apoptosis of VSMCs (26). AngII promotes inflammatory

responses and oxidative stress of various cell types such as

endothelium, VSMCs, and macrophages, within atheroscle-rotic

plaques (27,28). AngII upregulates the expression of

various pro-inflammatory mediators in VSMCs including TNF-α, MCP-1,

IL-6 and nitric oxide synthase (29). In our previous study, we

demonstrated that Cur significantly suppressed LPS-induced

expression of TNF-α and MCP-1, two mediators that also play an

important role in the progression of inflammatory responses within

atherosclerotic plaques by inducing macrophage chemotaxis and cell

apoptosis in VSMCs (5).

Therefore, we postulated that Cur may inhibit AngII-induced

inflammation in VSMCs. Our data showed that Cur significantly

decreased AngII-induced production of TNF-α and IL-6, and the

anti-inflammatory effect of Cur was concentration-dependent.

Previous studies have shown that Cur also suppressed ox-LDL, TNF-α

and PMA-induced inflammation in different cell types, which

indicates that the anti-inflammatory effect of Cur is multifaceted

and not only dependent upon AngII.

The production of NO in endothelial cells by the

enzyme ecNOS is beneficial for attenuating AngII-induced

dysfunction in endothelial cells in the initial formation of

atherosclerotic plaques (30).

However, high concentrations of NO promote the progression of

atherosclerosis by enhancing intercellular ROS production and

causing significant endothelial cell dysfunction. High amounts of

NO react with superoxide to become peroxynitrite, causing oxidative

stress and then increasing intercellular ROS (31). Moreover, deficiency in iNOS is

accompanied by a decrease in NO production reducing atherosclerosis

in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (32). These studies indicate that

suppressing the production of NO by iNOS may be a possible way to

delay the progression of atherosclerosis. Additionally, in our

previous study, we found that Cur can inhibit LPS-induced activity

of iNOS and then suppress production of NO in VSMCs (5). In our present experiments, we

observed that Cur suppressed AngII-induced NO production,

accompanied by a decrease in the expression of iNOS (both protein

and mRNA) in VSMCs. These results suggest that Cur can

significantly inhibit AngII-induced NO production by suppressing

the activity of iNOS in VSMCs, providing a new molecular mechanism

for the anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic effect of

Cur.

Although PPAR-γ was initially thought to regulate

the metabolism of glucose and lipid, it also participates in

controlling various physiological functions, especially

inflammation and proliferation (33). Previous studies have shown that

AngII can inhibit PPAR-γ activity, which accelerates the

progression of atherosclerosis and increases plaque instability by

upregulating the production of numerous types of proinflammatory

factors production (12). After

treatment with AngII, the concentration of MCP-1, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1

were significantly increased in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice

(34). Moreover, some PPAR-γ

agonists such as rosiglitazone and telmis-artan can suppress

AngII-induced inflammation in vivo and in vitro

(13,35). These studies suggest that

increasing PPAR-γ activity inhibits AngII-induced production of

proinflammatory factors, providing an effective method to delay the

progression of atherosclerosis and enhance plaque stability.

Additionally, Cur is a potential PPAR-γ agonist. Siddiqui et

al reported that by upregulating PPAR-γ, Cur inhibited

inflammation in an experimental model of sepsis (36). Cur also suppressed the expression

of TNF-α and ameliorated renal failure by activating PPAR-γ in 5/6

nephrectomized rats (37). In the

liver, Cur increased PPAR-γ activity and attenuated oxidative

stress and suppressed inflammation in CCl4-induced

injury and fibrogenesis (38).

Moreover, our previous study demonstrated that Cur inhibited

hypertension-induced cardiac fibrosis by activating PPAR-γ

(14). In this study, we found

that treating VSMCs with AngII increased the expression of TNF-α

and IL-6 and caused VSMC over-proliferation. This was accompanied

by the suppression of PPAR-γ, which is consistent with previous

studies. Treatment with Cur significantly attenuated AngII-induced

expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and VSMC proliferation by

increasing PPAR-γ expression and elevating its activation.

Meanwhile, the PPAR-γ antagonist GW9662 partially reversed the

anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects of Cur in

AngII-stimulated VSMCs by inhibiting PPAR-γ activation. These

results suggest that the activation of PPAR-γ, an

inflammation-related nuclear transcription factor, is involved in

the mechanism by which Cur suppresses AngII-induced inflammation

and proliferation in VSMCs.

Growing evidence shows that oxidative stress,

characterized by the overexpression of intercellular ROS, plays a

critical role in the progression of atherosclerosis (15). The common risk factors for

atherosclerosis such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, aging,

smoking and diabetes can induce overproduction of intercellular

ROS, not only in VSMCs but also in endothelial cells and

adventitial cells (39). ROS

production affects almost all of the processes of atherosclerosis,

such as lipid overload, abnormal lipid metabolism, calcium-related

signaling pathway inhibition, endoplasmic reticulum stress, VSMC

proliferation and endothelial cell dysfunction (40). ROS cause direct cellular damage,

but it can also act as potential secondary messengers that

participate in the inflammatory response (5). Therefore, we believe that there is a

close relationship between ROS production and inflammation. Some

studies have shown that inhibition of ROS production may be an

effective way to suppress atherosclerosis (41,42). Growing evidence indicates that Cur

may be a potential scavenger of intracellular ROS (5,43,44). In our previous study, we found

that Cur can inhibit NADPH-mediated iROS and free radical

production in LPS-stimulated VSMCs (5). In the present study, we found that

AngII significantly increased intracellular ROS production in

VSMCs, which agrees with previous studies (13,45). Treatment with Cur effectively

attenuated the AngII-induced increase in intracellular ROS and

inhibited free radical production by VSMCs. To detect whether the

anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects of Cur are linked

with inhibition of ROS production, we pretreated the cells with

DPI, a ROS antagonist. Our results indicated that this was

accompanied by a decrease in ROS production, pro-inflammatory

cytokine release and cell proliferation in AngII-stimulated VSMCs.

These responses were further decreased when the cells were treated

with a combination of Cur and DPI. These results indicate that

targeting ROS may be a critical mechanism by which Cur induces its

anti-inflammatory and anti-proliferative effects on

AngII-stimulated VSMCs.

It is generally recognized that the

membrane-associated enzyme NADPH oxidase is the main source of

intracellular ROS production in mammal cells. At present, NADPH

oxidase is expressed in almost all cell types of the cardiovascular

system, including VSMCs, cardiac fibrosis, cardiomyocytes, and

endothelial cells (16). Recent

studies have focused on the relationship between NADPH oxidase

activation and the progression of atherosclerosis (18,46). p47phox is one of the three main

subunits of the NADPH oxidase cytosolic component (16). Stimulation of cells causes an

increase in p47phox expression and an elevation in intracellular

ROS (47). Therefore it is

generally recognized that detection of p47phox expression is an

effective way to determine NADPH oxidase activation. In

vivo, a previous study revealed that impaired p47phox function

significantly reduced atherosclerotic plaque area and attenuated

plaque vulnerability caused by a high-fat diet (compared with the

ApoE−/− mice of normal p47phox function) (17). These previous studies suggest that

inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation may be an effective way to

suppress the progression of atherosclerosis. Moreover, studies have

reported that the inhibitory effect of Cur on NADPH oxidase

activation may play a critical role in its antioxidation by

decreasing intracellular ROS production (5,48,49). As shown by our results, the

expression of p47phox was significantly elevated after stimulation

by AngII, and was accompanied by an increase in ROS production.

Treatment with Cur effectively suppressed AngII-induced elevation

of p47phox expression. These results revealed that the inhibitory

effect of Cur on ROS production may be partially mediated by NADPH

oxidase. It is worth mentioning that other pathways have also been

observed to contribute to ROS production, such as the mitochondrial

electron chain, and it is worthwhile to explore other signaling

pathways that participate in the inhibitory effect of Cur on ROS

production. It is possible that, in addition to NADPH oxidase,

other pathways contribute to this effect in AngII-stimulated

VSMCs.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

Cur attenuated AngII-induced production of TNF-α, IL-6 and NO, and

cell proliferation in VMSCs. The anti-inflammatory and

anti-proliferative effect of Cur may partially depend on an

increase in PPAR-γ activity and suppression of NADPH

oxidase-mediated intracellular ROS production. These results may

provide a novel mechanism to explain the pharmacological effect of

Cur on chronic inflammation-related diseases, and its potentially

beneficial effect on atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Youth Foundation of

the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University (YFFAHZZ

2013020105 to Z.M.).

References

|

1

|

Jiang G, Wang D, Li W, Pan Y, Zheng W,

Zhang H and Sun YV: Coronary heart disease mortality in China: Age,

gender, and urban-rural gaps during epidemiological transition. Rev

Panam Salud Publica. 31:317–324. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bäck M and Hansson GK: Anti-inflammatory

therapies for atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 12:199–211. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Libby P: Inflammation in atherosclerosis.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 32:2045–2051. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chistiakov DA, Orekhov AN and Bobryshev

YV: Vascular smooth muscle cell in atherosclerosis. Acta Physiol

(Oxf). 214:33–50. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Meng Z, Yan C, Deng Q, Gao DF and Niu XL:

Curcumin inhibits LPS-induced inflammation in rat vascular smooth

muscle cells in vitro via ROS-relative TLR4-MAPK/NF-κB pathways.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 34:901–911. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Pacurari M, Kafoury R, Tchounwou PB and

Ndebele K: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in vascular

inflammation and remodeling. Int J Inflam. 2014:6893602014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Askari AT, Shishehbor MH, Kaminski MA,

Riley MJ, Hsu A and Lincoff AM; GUSTO-V Investigators: The

association between early ventricular arrhythmias,

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system antagonism, and mortality in

patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: insights

from Global Use of Strategies to Open Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) V.

Am Heart J. 158:238–243. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Derosa G and Maffioli P: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonists on glycemic

control, lipid profile and cardiovascular risk. Curr Mol Pharmacol.

5:272–281. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Usuda D and Kanda T: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors for hypertension. World J Cardiol.

6:744–754. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Fuentes E, Guzmán-Jofre L, Moore-Carrasco

R and Palomo I: Role of PPARs in inflammatory processes associated

with metabolic syndrome (Review). Mol Med Rep. 8:1611–1616.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Liu WX, Wang T, Zhou F, Wang Y, Xing JW,

Zhang S, Gu SZ, Sang LX, Dai C and Wang HL: Voluntary exercise

prevents colonic inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obese mice

by up-regulating PPAR-gamma activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

459:475–480. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Marchesi C, Rehman A, Rautureau Y, Kasal

DA, Briet M, Leibowitz A, Simeone SM, Ebrahimian T, Neves MF,

Offermanns S, et al: Protective role of vascular smooth muscle cell

PPARγ in angiotensin II-induced vascular disease. Cardiovasc Res.

97:562–570. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ji Y, Liu J, Wang Z, Liu N and Gou W:

PPARgamma agonist, rosiglitazone, regulates angiotensin II-induced

vascular inflammation through the TLR4-dependent signaling pathway.

Lab Invest. 89:887–902. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Meng Z, Yu XH, Chen J, Li L and Li S:

Curcumin attenuates cardiac fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive

rats through PPAR-γ activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 35:1247–1256.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li H, Horke S and Förstermann U: Vascular

oxidative stress, nitric oxide and atherosclerosis.

Atherosclerosis. 237:208–219. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Madamanchi NR and Runge MS: NADPH oxidases

and atherosclerosis: Unraveling the details. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 298:H1–H2. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Barry-Lane PA, Patterson C, van der Merwe

M, Hu Z, Holland SM, Yeh ET and Runge MS: p47phox is required for

atherosclerotic lesion progression in ApoE(−/−) mice. J Clin

Invest. 108:1513–1522. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kinkade K, Streeter J and Miller FJ:

Inhibition of NADPH oxidase by apocynin attenuates progression of

atherosclerosis. Int J Mol Sci. 14:17017–17028. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Goel A, Kunnumakkara AB and Aggarwal BB:

Curcumin as 'Curecumin': From kitchen to clinic. Biochem Pharmacol.

75:787–809. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Barzegar A and Moosavi-Movahedi AA:

Intracellular ROS protection efficiency and free radical-scavenging

activity of curcumin. PLoS One. 6:e260122011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Feng HL, Fan H, Dang HZ, Chen XP, Ren Y,

Yang JD and Wang PW: Neuroprotective effect of curcumin to Aβ of

double transgenic mice with Alzheimer's disease. Zhongguo Zhong Yao

Za Zhi. 39:3846–3849. 2014.In Chinese.

|

|

22

|

Sahebkar A: Dual effect of curcumin in

preventing atherosclerosis: The potential role of

pro-oxidant-antioxidant mechanisms. Nat Prod Res. 29:491–492. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Griendling KK, Taubman MB, Akers M,

Mendlowitz M and Alexander RW: Characterization of

phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C from cultured

vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 266:15498–15504.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Van Hoogmoed LM, Snyder JR and Harmon F:

In vitro investigation of the effect of prostaglandins and

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on contractile activity of the

equine smooth muscle of the dorsal colon, ventral colon, and pelvic

flexure. Am J Vet Res. 61:1259–1266. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jeong JM, Choi CH, Kang SK, Lee IH, Lee JY

and Jung H: Antioxidant and chemosensitizing effects of flavonoids

with hydroxy and/or methoxy groups and structure-activity

relationship. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 10:537–546. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mehta JL and Romeo F: Inflammation,

infection and atherosclerosis: Do antibacterials have a role in the

therapy of coronary artery disease? Drugs. 59:159–170. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Peters S: Inhibition of atherosclerosis by

angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonists. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs.

13:221–224. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Durante A, Peretto G, Laricchia A, Ancona

F, Spartera M, Mangieri A and Cianflone D: Role of the

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in the pathogenesis of

atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des. 18:981–1004. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fu Z, Wang M, Gucek M, Zhang J, Wu J,

Jiang L, Monticone RE, Khazan B, Telljohann R and Mattison J: Milk

fat globule protein epidermal growth factor-8: A pivotal relay

element within the angiotensin II and monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1 signaling cascade mediating vascular smooth muscle cells

invasion. Circ Res. 104:1337–1346. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kawashima S: The two faces of endothelial

nitric oxide synthase in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis.

Endothelium. 11:99–107. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bunderson M, Coffin JD and Beall HD:

Arsenic induces peroxynitrite generation and cyclooxygenase-2

protein expression in aortic endothelial cells: Possible role in

atherosclerosis. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 184:11–18. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Detmers PA, Hernandez M, Mudgett J,

Hassing H, Burton C, Mundt S, Chun S, Fletcher D, Card DJ, Lisnock

J, et al: Deficiency in inducible nitric oxide synthase results in

reduced atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. J

Immunol. 165:3430–3435. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Grygiel-Górniak B: Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: Nutritional and

clinical implications - a review. Nutr J. 13:172014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Azhar S: Peroxisome proliferator-activated

receptors, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Future

Cardiol. 6:657–691. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Matsumura T, Kinoshita H, Ishii N, Fukuda

K, Motoshima H, Senokuchi T, Taketa K, Kawasaki S, Nishimaki-Mogami

T, Kawada T, et al: Telmisartan exerts antiatherosclerotic effects

by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ in

macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 31:1268–1275. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Siddiqui AM, Cui X, Wu R, Dong W, Zhou M,

Hu M, Simms HH and Wang P: The anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin

in an experimental model of sepsis is mediated by up-regulation of

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Crit Care Med.

34:1874–1882. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Ghosh SS, Massey HD, Krieg R, Fazelbhoy

ZA, Ghosh S, Sica DA, Fakhry I and Gehr TW: Curcumin ameliorates

renal failure in 5/6 nephrectomized rats: Role of inflammation. Am

J Physiol Renal Physiol. 296:F1146–F1157. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Fu Y, Zheng S, Lin J, Ryerse J and Chen A:

Curcumin protects the rat liver from CCl4-caused injury

and fibrogenesis by attenuating oxidative stress and suppressing

inflammation. Mol Pharmacol. 73:399–409. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tousoulis D, Psaltopoulou T, Androulakis

E, Papageorgiou N, Papaioannou S, Oikonomou E, Synetos A and

Stefanadis C: Oxidative stress and early atherosclerosis: Novel

antioxidant treatment. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 29:75–88. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Li H, Horke S and Förstermann U: Oxidative

stress in vascular disease and its pharmacological prevention.

Trends Pharmacol Sci. 34:313–319. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Sun GB, Qin M, Ye JX, Pan RL, Meng XB,

Wang M, Luo Y, Li ZY, Wang HW and Sun XB: Inhibitory effects of

myricitrin on oxidative stress-induced endothelial damage and early

atherosclerosis in ApoE−/− mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol.

271:114–126. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Hort MA, Straliotto MR, Netto PM, da Rocha

JB, de Bem AF and Ribeiro-do-Valle RM: Diphenyl diselenide

effectively reduces atherosclerotic lesions in LDLr−/−

mice by attenuation of oxidative stress and inflammation. J

Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 58:91–101. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Rong S, Zhao Y, Bao W, Xiao X, Wang D,

Nussler AK, Yan H, Yao P and Liu L: Curcumin prevents chronic

alcohol-induced liver disease involving decreasing ROS generation

and enhancing antioxidative capacity. Phytomedicine. 19:545–550.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Yu W, Wu J, Cai F, Xiang J, Zha W, Fan D,

Guo S, Ming Z and Liu C: Curcumin alleviates diabetic

cardiomyopathy in experimental diabetic rats. PLoS One.

7:e520132012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Bruder-Nascimento T, Chinnasamy P,

Riascos-Bernal DF, Cau SB, Callera GE, Touyz RM, Tostes RC and

Sibinga NE: Angiotensin II induces Fat1 expression/activation and

vascular smooth muscle cell migration via Nox1-dependent reactive

oxygen species generation. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 66:18–26. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Gray SP, Di Marco E, Okabe J,

Szyndralewiez C, Heitz F, Montezano AC, de Haan JB, Koulis C,

El-Osta A, Andrews KL, et al: NADPH oxidase 1 plays a key role in

diabetes mellitus-accelerated atherosclerosis. Circulation.

127:1888–1902. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ushio-Fukai M: Localizing NADPH

oxidase-derived ROS. Sci STKE. 2006:re82006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhao WC, Zhang B, Liao MJ, Zhang WX, He

WY, Wang HB and Yang CX: Curcumin ameliorated diabetic neuropathy

partially by inhibition of NADPH oxidase mediating oxidative stress

in the spinal cord. Neurosci Lett. 560:81–85. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Derochette S, Franck T, Mouithys-Mickalad

A, Ceusters J, Deby-Dupont G, Lejeune JP, Neven P and Serteyn D:

Curcumin and resveratrol act by different ways on NADPH oxidase

activity and reactive oxygen species produced by equine

neutrophils. Chem Biol Interact. 206:186–193. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|