Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is an

age-associated macular disease, and the most common disease of

blindness in people >60 years old (1). Its main feature is the retinopathy

of the retina and choroid, which causes decreased visual function

and reduced central vision in particular (2). Oxidative stress serves a vital role

in the pathogenesis of AMD (3).

Retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells, as the most metabolically

active type of cellin eye tissue, can engulf the outer disc of the

retina photoreceptor cells and produce a large number of lipid

peroxides and H2O2 (4). Furthermore, the photo-oxidation

effect occurs when RPE is illuminated over long durations (5). Therefore, RPE has a higher

susceptibility to oxidative stress. In addition, due to aging, the

resistance of the antioxidant system of RRE declines (6,7).

Oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant capacity may lead to

functional disorders and structural abnormalities of the RPE, which

have been identified as important pathological alterations

associated with AMD (3,6,7).

Genipin (GP), is a glycosidic ligand derived from

iridoid glycosides and is widely distributed in plants, including

Mast and Eucommia ulmoides. GP is the main metabolite of

geniposide in humans or animals, and is also the main active form

with pharmacokinetic function (8). Studies have demonstrated that GP has

certain properties, including anti-infection, anti-inflammation,

antioxidation and antitumor (9-12).

In addition, GP has been widely regarded as a specific inhibitor of

uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) (13). UCP2 is a functional protein in the

mitochondrial inner membrane, which regulates the proton pump of

mitochondria (14). Specifically,

UCP2 is involved in modulating the opening of the ion channels on

the mitochondrial membrane, inhibiting the production of reactive

oxygen species (ROS), there by suppressing the apoptosis of cells

and damage to mitochondria (15).

However, the role of GP on RPE cell injury induced by oxidative

stress is unknown.

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2),

as a transcription factor, serves a vital function in opposing cell

damage due to endogenous and exogenous stresses (16). It is well known that Nrf2 is a

main regulator of the antioxidant reaction, which can control the

antioxidant response element-regulated the expression of phase II

and antioxidant enzymes, including heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and

NAD(P)H: Quinine oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) (17,18). It has been reported that

antioxidants protect oxidative stress-induced RPE cells by

activating Nrf2 signaling (19).

The present study, aimed to establish an RPE cell

oxidative stress injury model; H2O2 acts as

an inducer of oxidative damage to RPE cells (20). In addition, the effects of GP on

H2O2-induced RPE cells were determined and

whether the underlying molecular mechanism is associated with Nrf2

signaling was investigated in the present study.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

Human RPE cell lines (ARPE-19 cells) were obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA),

which were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s

medium/Nutrient F12 Ham (DMEM/F12; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA,

Darmstadt, Germany), which contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS;

HyClone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA), 100

µg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin (Beijing Solarbio

Science & Technology, Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) in a

humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37°C (80G-2,

Shanghai Huafu Instrument Co. Ltd.).

ARPE-19 cells were transfected with pSilencer 2.1

vector (1 µg, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA) containing small interfering (si)RNA negative control (NC;

5′-CAC ACT GGA TGG CCT AGG AGG ATA T-3′) or siRNA Nrf2

(siNrf2;5′-CAC ACT GGA TCA GAC AGG AGG ATA T-3′) vectors using

Lipofectamine® 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

After transfection, cells were incubated for 24 h and then used for

subsequent experimentation; untreated cells served as the

control.

Methylthiazolyldiphenyl-tetrazolium

bromide (MTT) assay

An MTT kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology,

Shanghai, China) was employed to measure cell viability. ARPE-19

cells were seeded into 96-well plates (2×103 cell/well)

for 24 h. Cells were exposed to various concentrations of

H2O2 (0, 10, 50, 100, 200, 400 and 800

µM) and GP (0, 5, 10, 30, 50 and 100 µM) for 24 h at

37°C, respectively. Other cells were transfected with NC and siNrf2

vectors as aforementioned. Then, cells were incubated with MTT

solution for 4 h at 37°C. Subsequently, the supernatant was

removed; dimethyl sulfoxide was then added to the cells and the

optical density at 490 nm was evaluated using a microplate reader

(SpectraMax iD3, Molecular Devices, LLC, Sunnyvale, CA, USA); 200

µM H2O2 was finally used to treat

cells in the subsequent experiments.

Flow cytometry

For the analysis of ROS, a ROS assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was employed according to the

manufacturer’s protocols. In brief, cells were seeded into 6-well

plates (5×104 cell/well) for 24 h. Then, cells were

treated with 200 µM H2O2, 30 µM

GP, NC vector or siNrf2 vector for 24 h as aforementioned.

Following treatment, cells were incubated with

2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) at

37°C for 30 min and then washed with PBS for three times. The

levels of ROS were determined using a MoFlo flow cytometer (Beckman

Coulter, Inc., Brea, CA, USA) and the data was analyzed using

SUMMIT Software V4.3 (Dako; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara,

USA).

For the cell apoptosis assay, an Annexin

V-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) apoptosis

detection kit (Dalian Meilunbio Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian,

China) was employed according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Briefly, cells were seeded into 6-well plates (5×104

cell/well) for 24 h. Then, cells were treated with 200 µM

H2O2, 30 µM GP, NC vector and siNrf2

vector for 24 h as aforementioned. Following treatment, cells were

digested with 0.25% EDTA-trypsin (Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology, Co., Ltd.) at room temperature for 2 min and

resuspended in DMEM/F12. The cells were centrifuged at 1,000 × g

for 5 min at 4°C, and then incubated with Annexin V-FITC and PI in

darkness for 25 min at room temperature. Cell apoptosis was

analyzed with a MoFlo flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.) and

the data was analyzed using SUMMIT Software V4.3. The number of

apoptotic cells was calculated by adding data in the second and the

fourth quadrants of the flow cytometry data.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol

reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the

manufacturer’s protocols. RNA (1 µg) was used to synthesize

cDNA by using the Quantscript RT Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison,

WI, USA) under the following conditions: 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for

50 min, 85°C for 15 min and 4°C for 10 min. cDNA was amplified

using a SYBR Premix Taq™ II kit (Takara Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan) on

an ABI 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C

for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of at 95°C for 15 sec and at 62°C

for 30 sec, and extension for 60 sec at 72°C. The sequences of

primers were presented in Table

I. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The quantification of

gene expression was performed using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(21).

| Table ISequences of the primers employed for

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. |

Table I

Sequences of the primers employed for

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

| Primer | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| HO-1-forward |

CGTTCCTGCTCAACATCCAG |

| HO-1-reverse |

TGAGTGTAAGGACCCATCGG |

| NQO1-forward |

AGAAAGGATGGGAGGTGGTG |

| NQO1-reverse |

ATATCACAAGGTCTGCGGCT |

| Bax-forward |

AACATGGAGCTGCAGAGGAT |

| Bax-reverse |

CCAATGTCCAGCCCATGATG |

| Bcl-2-forward |

TTCTTTGAGTTCGGTGGGGT |

| Bcl-2-reverse |

CTTCAGAGACAGCCAGGAGA |

| GAPDH-forward |

CCATCTTCCAGGAGCGAGAT |

| GAPDH-reverse |

TGCTGATGATCTTGAGGCTG |

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay

buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology, Co., Ltd.) to

obtain protein extracts. A Bradford’s protein assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology) was employed to detect the

concentrations of protein extracts. Each protein (25 µg per

lane) was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Merck KGaA). The membrane was

blocked using tris-buffered saline with TBS solution (0.05%

Tween-20) containing 5% non-fat milk for 1 h at 4°C. The membrane

was incubated with anti-HO-1 (AF3169, 1:600; R&D Systems, Inc.,

Minneapolis, MN, USA), anti-Nrf2 (MAB3925, 1:800; R&D Systems,

Inc.), anti-NQO1 (AF7567, 1:1,200; R&D Systems, Inc.),

anti-cleaved-caspase-3 (AF835, 1:1,000; R&D Systems, Inc.),

anti-B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2; AF810, 1:800; R&D Systems,

Inc.), anti-Bcl-2 associated X (Bax; AF820, 1:1,000; R&D

Systems, Inc.) and anti-GAPDH (2275-PC-100, 1:600; R&D Systems,

Inc.) at 4°C overnight. Then, the membrane was washed with TBST for

three times. Following washing, the membrane was incubated with

corresponding secondary antibodies [rabbit anti-goat

IgG-horseradish peroxidase (HRP), sc-2768, 1:6,000; mouse

anti-rabbit, IgG-HRP, sc-2357, 1:7,000; donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP,

sc-2020, 1:8,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA)

at 37°C for 60 min. The membrane was washed with TBST for three

times. Subsequently, the proteins were detected by using an

enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (GE Healthcare,

Chicago, IL, USA)and exposed under an E-Gel Imager (Invitrogen;

Thermo, Fisher, Scientific, Inc.). The blot density was analyzed by

Quantity One software version 4.6.2 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.,

Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± standard

deviation using SPSS software (version 20; IBM, Corp., Armonk, NY,

USA). The differences among groups were assessed by one-way

analysis of variance followed by a Tukey’s post hoc test. All the

experiment was independently conducted at least for three times.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

GP alleviates decreased viability of

ARPE-19 cells induced by H2O2

To investigate the effects of GP and

H2O2 on the viability of ARPE-19 cells, an

MTT assay was conducted to determine cell viability. The results

revealed that cell viability was significantly suppressed in

response to treatment with 200, 400 and 800 µM

H2O2 compared with the control (Fig. 1A), while 30, 50 and 100 µM

GP significantly promoted cell viability compared with the control;

the increased cell viability at 30 µM GP was similar to that

of 50 and 100 µM (Fig.

1B). Therefore, 100 and 200 µM

H2O2 and 5, 10, 30 µM GP was selected

to further detect the effects of GP on

H2O2-treated cells. Upon treatment with

H2O2 (10, 50 and 100 µM) or GP (5 and

10 µM), no notable alterations in cell viability were

observed. Treatment with 200 µM H2O2

and GP (0, 5, 10 and 30 µM) exhibited significantly reduced

cell viability compared with the untreated control (Fig. 1C). No significant difference was

observed between the GP + 200 µM H2O2

and GP + 100 µM H2O2 groups. Thus, 30

µM GP was used to treat cells for subsequent experiments.

The present study reported that cell viability was significantly

increased in the 30 µM GP + 200 µM

H2O2 group compared with the 200 µM

H2O2 group (Fig. 1C). The results indicated that GP

increased the viability of H2O2-treated

cells.

| Figure 1GP alleviates decreased viability of

ARPE-19 cells induced by H2O2. (A-C) ARPE-19

cells were exposed to various concentrations of

H2O2 (0, 10, 50, 100, 200, 400+ and 800

µM) and GP (0, 5, 10, 30, 50 and 100 µM). Cell

viability was assessed by an MTT assay. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, vs. 0 µM group.

#P<0.05, vs. 200 µM H2O2

group. n=5. GP, genipin. |

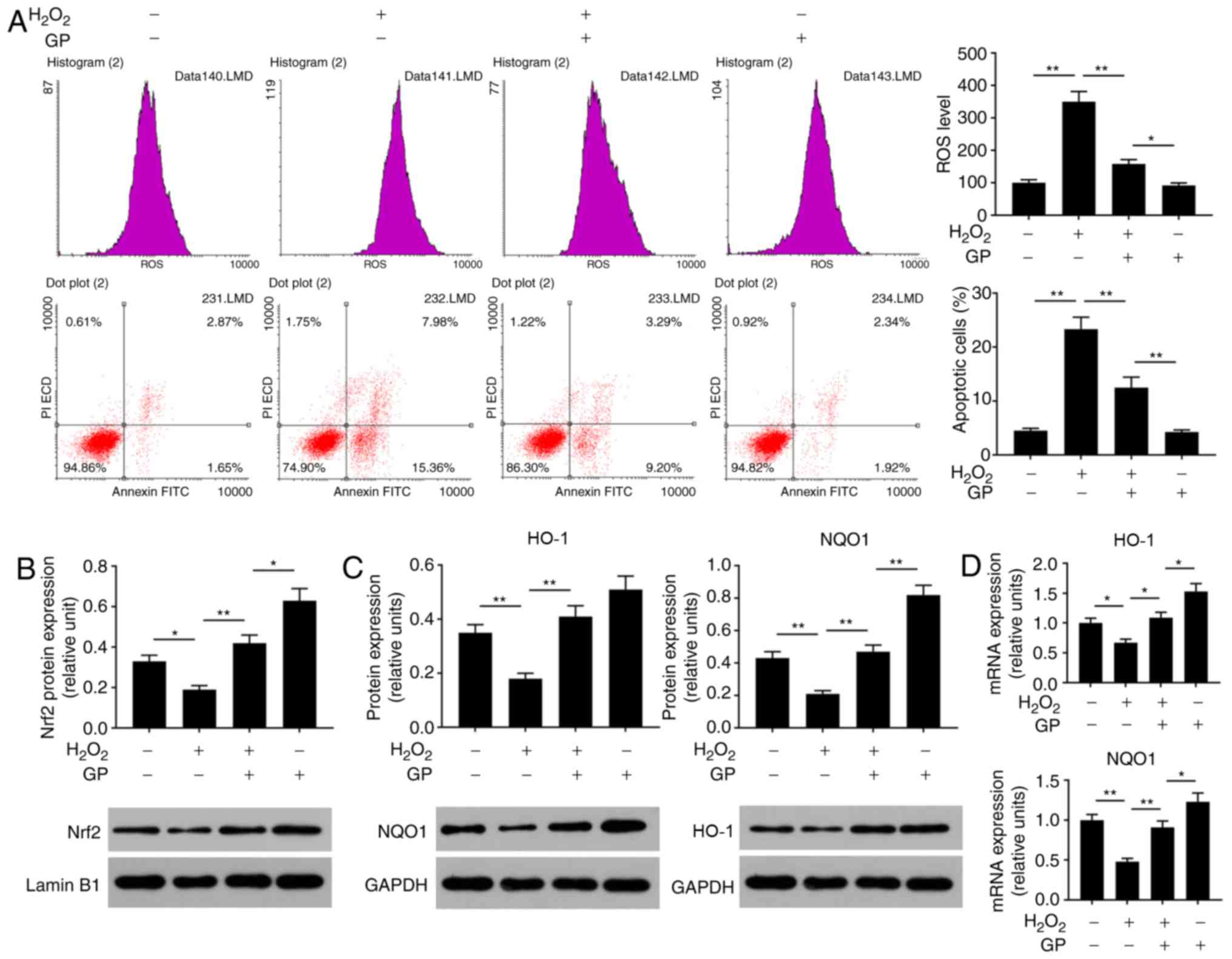

GP suppresses the effects of

H2O2 on the levels of ROS and apoptosis of

ARPE-19 cells by activating Nrf2 signaling

Oxidative stress is an important cause of injury to

RPE cells (22). To analyze the

effects of GP on H2O2-induced ARPE-19 cell

injury, the ROS levels, cell apoptosis and Nrf2 signaling were

detected. The data of flow cytometry revealed that ROS levels and

the number of apoptotic cells were significantly enhanced in cells

treated with H2O2 compared with in untreated

and H2O2-induced cells treated with GP

(Fig. 2A). In addition,

H2O2 significantly reduced the protein

expression levels of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO1, and the mRNA expression

levels of HO-1 and NQO1 compared with the control (Fig. 2B-D). On the contrary, treatment

with GP significantly increased the expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and

NQO1 in H2O2-induced cells compared with

H2O2 treatment alone (Fig. 2B-D). The results suggested that GP

suppressed H2O2-induced RPE cell

injuries.

Nrf2 silencing enhances

H2O2-induced damage to ARPE-19 cells

In the present study, to determine the effects of

Nrf2 on ARPE cells, cell viability and the expression levels of

Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO1 were respectively analyzed by an MTT assay,

RT-qPCR and western blotting. When cells were transfected with

siRNA Nrf2 vector, no notable alterations in cell viability were

observed (Fig. 3A). As the

demonstrated by western blotting, the expression levels of NQO1,

HO-1 and Nrf2 proteins were significantly suppressed in the siNrf2

group compared with in the NC group (Fig. 3B and C). In addition, the mRNA

expression profiles of NQO1 and HO-1 were similar to the protein

expression profile in each group (Fig. 3D). In order to further investigate

the effects of siNrf2 on ARPE cells induced by

H2O2, the ROS levels, cell apoptosis and Nrf2

signaling were analyzed. The present study reported that siNrf2

significantly and markedly enhanced the ROS levels and apoptosis in

ARPE-19 cells induced by H2O2, respectively,

compared with the H2O2 + NC group (Fig. 4A). The expression levels of

apoptosis-associated factors were evaluated by RT-qPCR and western

blotting. SiNrf2 significantly downregulated the expression levels

of Nrf2, NQO1 and HO-1 in cells treated with

H2O2, compared with the

H2O2 + NC group (Fig. 4B, C and E). The results also

revealed that, compared with the H2O2 and

H2O2 + NC groups, siNfr2-transfected cells

treated with H2O2 exhibited increased Bax and

cleaved-caspase-3 expression levels; the protein expression levels

of Bcl-2 were significantly decreased in the

H2O2 + siNrf2 group compared with the

H2O2 and H2O2 + NC

groups (Fig. 4D and F). These

results suggested that Nrf2 knockdown enhanced

H2O2-induced RPE cell injury.

| Figure 4Nrf2 silencing enhances

H2O2-induced damage to ARPE-19 cells. (A)

ARPE-19 cells were subjected to treatment with 200 µM

H2O2, NC vector and siNrf2 vector. Flow

cytometry was performed to analyze the levels of ROS and the number

of apoptotic cells. *P<0.05 vs.

H2O2 + NC group. (B) Proteins expression

levels of Nrf2, were determined using western blotting. (C) The

protein expression levels of NQO1 and HO-1 were detected by reverse

transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (D) The

protein expression levels of cleaved-caspase 3, Bax and Bcl-2 were

detected by western blotting. (E) The mRNA expression levels of

HO-1 and NQO1 were detected by reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. (F) The mRNA expression levels of Bax

and Bcl-2 were detected by reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. n=4. Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax,

Bcl-2-associated X; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; HO-1, heme

oxygenase-1; NQO1, NAD(P)H: Quinine oxidoreductase; Nrf2, nuclear

factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2; PI, propidium iodide; siRNA,

small interfering RNA; NC, siRNA negative control; siNrf2, siRNA

Nrf2. |

Nrf2 silencing attenuates the protective

effects of GP on H2O2-induced ARPE-19

cells

In the present study, the role of Nrf2 in

GP-induced-effects on H2O2-treated cells was

investigated. Flow cytometry revealed that, compared with the

H2O2 + GP + NC group, the ROS levels and

number of apoptotic cells were significantly increased in the

H2O2 + GP + siNrf2 group; GP significantly

decreased ROS levels and apoptosis in

H2O2-induced cells compared with

H2O2 treatment alone (Fig. 5A). When cells were exposed to GP

and siNrf2 vector, the protein expression levels of Nrf2, NQO1,

HO-1, and Bcl-2 were significantly downregulated, while that of Bax

and cleaved-caspase-3 were significantly upregulated, compared with

the GP group. Additionally, compared with the

H2O2 + GP + NC group, the expression of Nrf2,

NQO1, HO-1, and Bcl-2 were inhibited in the

H2O2 + GP + siNrf2 group; the protein

expression levels of Bax and cleaved-caspase-3 were notably and

significantly increased, respectively (Fig. 5B-D). The mRNA expression profile

of Nrf2, NQO1, HO-1, Bcl-2 and Bax was similar to their respective

trend in protein levels (Fig. 5E and

F). The results of the present study suggested that the

activation of Nrf2 signaling was associated with the protective

effects of GP on H2O2-treated RPE cells.

| Figure 5Nrf2 silencing attenuates the effects

of GP on H2O2-induced ARPE-19 cells. (A)

ARPE-19 cells were subjected to treatment with 200 µM

H2O2, 30 µM GP, NC vector and siNrf2

vector. Flow cytometry was applied to analyze the levels of ROS and

the number of apoptotic cells. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. (B-D) Proteins expression levels of Nrf2,

HO-1, NQO1, Bax, Bcl-2 and cleaved-caspase 3 were determined by

western blotting. (E and F) mRNA expression levels of HO-1, NQO1,

Bax and Bcl-2 were detected by reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01. n=4. Bcl-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; Bax,

Bcl-2-associated X; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; HO-1, heme

oxygenase-1; NQO1, NAD(P)H: Quinine oxidoreductase; Nrf2, nuclear

factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2; PI, propidium iodide; siNrf2,

small interfering RNA Nrf2. |

Discussion

Oxidative stress is one of the most important

mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of AMD (3). Oxidative damage of RPE is a key

process in the pathogenesis of AMD (4). H2O2 can induce

the production of ROS in cells, leading to oxidative damage

(23). Exogenous

H2O2 treatment is a simple and feasible cell

model for studying RPE oxidative damage, which can effectively

simulate the process of oxidative damage of RPE in AMD (24,25). Therefore, in the present study,

H2O2 was selected as an inducer of oxidative

damage to ARPE-19 cells. Additionally, 200 µM

H2O2 was identified as the optimal

concentration to generate a cellular oxidative damage model.

GP has been demonstrated to prevent or treat

cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, nervous system diseases,

pathogenic infections and inflammation (26-30). Lin et al (28) reported that GP protected renal

tissue from oxidative stress-associated injury by suppressing

oxidative stress and apoptosis. Shin and Lee (29) proposed that GP improved

age-associated insulin resistance by reducing oxidative stress in

LO2 cells; however, the role of GP in AMD remains unclear. In the

present study, it was suggested that GP exerted a protective effect

on H2O2-induced oxidative damage of ARPE-19

cells. The results of the present study revealed that GP (30, 50

and 100 µM) significantly increased the viability of ARPE-19

cells, indicating that the treatment of GP may induce some survival

signals in ARPE-19 cells; the increased cell viability in response

to 30 µM GP was similar to that of 50 and 100 µM.

Therefore, low, moderate and high concentrations of GP (5, 10 and

30 µM) were selected to analyze cell viability inhibited by

H2O2. The data demonstrated that 30 µM

GP significantly enhanced cell viability. Hence, 30 µM GP

was determined to be the optimal concentration for analysis in the

present study. The observations of the present study suggested that

GP exerted a protective effect on

H2O2-induced oxidative damage of ARPE-19

cells by enhancing cell viability.

Oxidative damage is caused by the imbalance of the

intracellular redox state, which generates a large amount of active

oxygen and produces free radicals (31). Providing the concentration of ROS

exceeds the clearance capacity of the body, tissue or cell damage

may occur (32,33). It has been reported that

antioxidant genes and drugs inhibit

H2O2-induced oxidative damage by decreasing

ROS activity (26,34-37). Studies have demonstrated that

oxidative stress injury is one of the important factors of

apoptosis (38-40). Radi et al (39) have reported that taxifolin

alleviated H2O2-induced oxidative stress

injury of ARPE-19 cells by inhibiting apoptosis. Therefore, ROS

levels and the apoptosis of ARPE-19 cells treated with

H2O2 and GP were analyzed by flow cytometry

in the present study. Similar to previous reports (34,36,37,41), the results of the present study

revealed that GP significantly reduced the levels of ROS and

apoptosis in ARPE-19 cells induced by H2O2.

In addition, GP significantly suppressed the expression of Bax and

cleaved-caspase 3, and promoted Bcl-2 expression. These

observations indicated that GP opposed the effects of

H2O2 on ARPE-19 cell injury via

anti-apoptosis and antioxidation.

Nrf2 signaling serves a key role in regulating

antioxidant enzymes, and is also an important part of maintaining

oxidative and antioxidative homeostasis, and alleviating oxidative

stress damage (42). HO-1 and

NQO1 are the key downstream factors of Nrf2 signaling, and serve an

important role in protecting cells from oxidative damage (43,44). Hu et al (43) indicated that microRNA-455

activated the Nrf2 signaling pathway to protect osteoblasts against

H2O2-induced injury. Vurusaner et al

(44) proposed that laminarin

ameliorated H2O2-induced MRC-5 cell oxidative

injury by promoting the Nrf2 signaling pathway (45). Previous studies have also reported

the beneficial effects of the Nrf2 signaling pathway on RPE cells

(46,47). In the present study, it was

proposed that the potential antioxidative mechanism of GP may

comprise Nrf2 signaling. The results demonstrated that GP reversed

the inhibitory effects of H2O2 on the

expression of Nrf2, HO-1 and NQO1 in ARPE-19 cells. In addition,

the effects of Nrf2 on ARPE-19 cells were investigated in the

present study. The results revealed that Nrf2 knockdown exhibited

no toxicity to cells; the effects of Nrf2 knockdown may be mainly

produced on the molecular level rather than at the cellular level.

However, Nrf2 silencing enhanced the effects of

H2O2 on inducing cell damage via increasing

ROS levels and apoptosis. Furthermore, Nrf2 silencing attenuated

the protective effects of GP on H2O2-induced

ARPE-19 cell injury by promoting apoptosis and oxidation.

Therefore, the activation of Nrf2 signaling may be closely

associated with the protective effects of GP. In addition, it has

been reported that GP suppressed the growth of breast cancer cells

by inhibiting UCP2 (14). Thus,

it is possible that other signals may also associate with the

protective effects of GP.

In summary, the present study proposed the novel

functions of GP, which protected ARPE-19 cells against oxidative

damage induced by H2O2 via promoting cell

viability and suppressing ROS levels and apoptosis. The molecular

mechanism was associated with the activation of Nrf2 signaling.

These results suggested that GP may be considered as a therapeutic

agent for the treatment and prevention of AMD.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed data sets generated during the study

are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors’ contributions

HZ wrote the manuscript. HZ, RW, MY and LZ

performed the experiments and data analysis. HZ and LZ designed the

study and contributed to manuscript revisions. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

References

|

1

|

Nowak JZ: Age-related macular degeneration

(AMD): Pathogenesis and therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 58:353–363.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jager RD, Mieler WF and Miller JW:

Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 358:2606–2617.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Hernández-Zimbrón LF, Zamora-Alvarado R,

Ochoa-De la Paz L, Velez-Montoya R, Zenteno E, Gulias-Cañizo R,

Quiroz-Mercado H and Gonzalez-Salinas R: Age-related macular

degeneration: New paradigms for treatment and management of AMD.

Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018:83746472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Liu L and Wu XW: Nobiletin protects human

retinal pigment epithelial cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced

oxidative damage. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 32:e220522018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Wang Y, Kim HJ and Sparrow JR: Quercetin

and cyanidin-3-glucoside protect against photooxidation and

photo-degradation of A2E in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp

Eye Res. 160:45–55. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dun Y, Vargas J, Brot N and Finnemann SC:

Independent roles of methionine sulfoxide reductase A in

mitochondrial ATP synthesis and as antioxidant in retinal pigment

epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 65:1340–1351. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jiang H, Wu M, Liu Y, Song L, Li S, Wang

X, Zhang YF, Fang J and Wu S: Serine racemase deficiency attenuates

choroidal neovascularization and reduces nitric oxide and VEGF

levels by retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Neurochem.

143:375–388. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Lee CH, Kwak SC, Kim JY, Oh HM, Rho MC,

Yoon KH, Yoo WH, Lee MS and Oh J: Genipin inhibits RANKL-induced

osteoclast differentiation through proteasome-mediated degradation

of c-Fos protein and suppression of NF-κB activation. J Pharmacol

Sci. 124:344–353. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Kim ES, Jeong CS and Moon A: Genipin, a

constituent of Gardenia jasminoides Ellis, induces apoptosis and

inhibits invasion in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Oncol Rep.

27:567–572. 2012.

|

|

10

|

Lim W, Kim O, Jung J, Ko Y, Ha J, Oh H,

Lim H, Kwon H, Kim I, Kim J, et al: Dichloromethane fraction from

Gardenia jasminoides: DNA topoisomerase 1 inhibition and oral

cancer cell death induction. Pharm Biol. 48:1354–1360. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Machida K, Oyama K, Ishii M, Kakuda R,

Yaoita Y and Kikuchi M: Studies of the constituents of Gardenia

species. II. Terpenoids from Gardeniae Fructus. Chem Pharm Bull

(Tokyo). 48:746–748. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zuo T, Zhu M, Xu W, Wang Z and Song H:

Iridoids with genipin stem nucleus inhibit

lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation and oxidative stress by

blocking the NF-κB pathway in polycystic ovary syndrome. Cell

Physiol Biochem. 43:1855–1865. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hoshovs’ka IUV, Shymans’ka TV and Sahach

VF: Effect of UCP2 activity inhibitor genipin on heart function of

aging rats. Fiziol Zh. 55:28–34. 2009.In Ukrainian.

|

|

14

|

Ayyasamy V, Owens KM, Desouki MM, Liang P,

Bakin A, Thangaraj K, Buchsbaum DJ, LoBuglio AF and Singh KK:

Cellular model of Warburg effect identifies tumor promoting

function of UCP2 in breast cancer and its suppression by genipin.

PLoS One. 6:e247922011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Dando I, Fiorini C, Pozza ED, Padroni C,

Costanzo C, Palmieri M and Donadelli M: UCP2 inhibition triggers

ROS-dependent nuclear translocation of GAPDH and autophagic cell

death in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1833:672–679. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N and Biswal S:

Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the

Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 47:89–116.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Nguyen T, Nioi P and Pickett CB: The

Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its

activation by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 284:13291–13295. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhang M, An C, Gao Y, Leak RK, Chen J and

Zhang F: Emerging roles of Nrf2 and phase II antioxidant enzymes in

neuroprotection. Prog Neurobiol. 100:30–47. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

19

|

Sachdeva MM, Cano M and Handa JT: Nrf2

signaling is impaired in the aging RPE given an oxidative insult.

Exp Eye Res. 119:111–114. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

20

|

Kang KA, Wang ZH, Zhang R, Piao MJ, Kim

KC, Kang SS, Kim YW, Lee J, Park D and Hyun JW: Myricetin protects

cells against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis via regulation of

PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 11:4348–4360.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Patel AK and Hackam AS: Toll-like receptor

3 (TLR3) protects retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE) cells from

oxidative stress through a STAT3-dependent mechanism. Mol Immunol.

54:122–131. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

23

|

Sies H: Role of metabolic

H2O2 generation: Redox signaling and

oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 289:8735–8741. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen XD, Su MY, Chen TT, Hong HY, Han AD

and Li WS: Oxidative stress affects retinal pigment epithelial cell

survival through epidermal growth factor receptor/AKT signaling

pathway. Int J Ophthalmol. 10:507–514. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Du L, Chen J and Xing YQ: Eupatilin

prevents H2O2-induced oxidative stress and

apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biomed

Pharmacother. 85:136–140. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Chen S, Sun P, Zhao X, Yi R, Qian J, Shi Y

and Wang R: Gardenia jasminoides has therapeutic effects on

L-NNA-induced hypertensio in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 15:4360–4373. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chen XL, Tang WX, Tang XH, Qin W and Gong

M: Downregulation of uncoupling protein-2 by genipin exacerbates

diabetes-induced kidney proximal tubular cells apoptosis. Ren Fail.

36:1298–1303. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin YH, Tsai SC, Lai CH, Lee CH, He ZS and

Tseng GC: Genipin-cross-linked fucose-chitosan/heparin

nanoparticles for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori.

Biomaterials. 34:4466–4479. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Shin JK and Lee SM: Genipin protects the

liver from ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating mitochondrial

quality control. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 328:25–33. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Yu D, Shi M, Bao J, Yu X, Li Y and Liu W:

Genipin ameliorates hypertension-induced renal damage via the

angiotensin II-TLR/MyD88/MAPK pathway. Fitoterapia. 112:244–253.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Dias HKI, Milward M, Grant M, Chapple ILC

and Griffiths HR: Sulforaphane decreases neutrophil hyperactivity

by reducing intracellular oxidative stress. Free Rad Biol Med.

53:S492012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Schieber M and Chandel NS: ROS function in

redox signaling and oxidative stress. Curr Biol. 24:R453–R462.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Slimen IB, Najar T, Ghram A, Dabbebi H,

Ben Mrad M and Abdrabbah M: Reactive oxygen species, heat stress

and oxidative-induced mitochondrial damage. A review. Int J

Hyperthermia. 30:513–523. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu H, Liu W, Zhou X, Long C, Kuang X, Hu

J, Tang Y, Liu L, He J, Huang Z, et al: Protective effect of lutein

on ARPE-19 cells upon H2O2-induced G2/M

arrest. Mol Med Rep. 16:2069–2074. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mitter SK, Song C, Qi X, Mao H, Rao H,

Akin D, Lewin A, Grant M, Dunn W Jr, Ding J, et al: Dysregulated

autophagy in the RPE is associated with increased susceptibility to

oxidative stress and AMD. Autophagy. 10:1989–2005. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhu C, Dong Y, Liu H, Ren H and Cui Z:

Hesperetin protects against H2O2-triggered

oxidative damage via upregulation of the Keap1-Nrf2/HO-1 signal

pathway in ARPE-19 cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 88:124–133. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhu Y, Zhao KK, Tong Y, Zhou YL, Wang YX,

Zhao PQ and Wang ZY: Exogenous NAD(+) decreases oxidative stress

and protects H2O2-treated RPE cells against

necrotic death through the up-regulation of autophagy. Sci Rep.

6:263222016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Areti A, Yerra VG, Naidu V and Kumar A:

Oxidative stress and nerve damage: Role in chemotherapy induced

peripheral neuropathy. Redox Biol. 2:289–295. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Radi E, Formichi P, Battisti C and

Federico A: Apoptosis and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative

diseases. J Alzheimers Dis. 42(Suppl 3): S125–S152. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Su J, Shi HX, Wang LJ, Guo RX, Ren TK and

Wu YB: Chemical constituents of bark of Taxus chinensis var.

mairei. Zhong Yao Cai. 37:243–251. 2014.In Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Xie X, Feng J, Kang Z, Zhang S, Zhang L,

Zhang Y, Li X and Tang Y: Taxifolin protects RPE cells against

oxidative stress-induced apoptosis. Mol Vis. 23:520–528.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Huang Y, Li W, Su ZY and Kong AN: The

complexity of the Nrf2 pathway: Beyond the antioxidant response. J

Nutr Biochem. 26:1401–1413. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hu Y, Duan M, Liang S, Wang Y and Feng Y:

Senkyunolide I protects rat brain against focal cerebral

ischemia-reperfusion injury by up-regulating p-Erk1/2, Nrf2/HO-1

and inhibiting caspase 3. Brain Res. 1605:39–48. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Vurusaner B, Gamba P, Gargiulo S, Testa G,

Staurenghi E, Leonarduzzi G, Poli G and Basaga H: Nrf2 antioxidant

defense is involved in survival signaling elicited by

27-hydroxycholesterol in human promonocytic cells. Free Radic Biol

Med. 91:93–104. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Liu X, Liu H, Zhai Y, Li Y, Zhu X and

Zhang W: Laminarin protects against hydrogen peroxide-induced

oxidative damage in MRC-5 cells possibly via regulating NRF2.

PeerJ. 5:e36422017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang K, Jiang Y, Wang W, Ma J and Chen M:

Escin activates AKT-Nrf2 signaling to protect retinal pigment

epithelium cells from oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

468:541–547. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Hu H, Hao L, Tang C, Zhu Y, Jiang Q and

Yao J: Activation of KGFR-Akt-mTOR-Nrf2 signaling protects human

retinal pigment epithelium cells from Ultra-violet. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 495:2171–2177. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|