Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) constitutes one of the

most serious cardiac events with high morbidity and mortality

worldwide (1,2). Myocardial remodeling occurs after MI

as a compensatory mechanism to decrease wall stress which may lead

to inevitable cardiac dilatation, followed by heart failure

(3). At present, pharmacological

intervention remains the most effective treatment for preventing

post-infarction cardiac remodeling and dysfunction (4). The one year mortality rate of

patients hospitalized for heart failure after MI was as high as

43.2% (5). Therefore, it has been

crucial to exploit effective intervention targets for attenuating

cardiac remodeling and dysfunction post MI, thereby preventing the

development of heart failure in post-infarction patients (6).

Apoptosis and autophagy are reported to participate

in physiological processes that occur constitutively in the

myocardium (7,8). The roles of apoptosis and autophagy

in ischemic myocardial injury have been extensively demonstrated in

ischemic induced myocardial injury. Increasing evidence suggests

that apoptosis and autophagy disruption results in the development

of severe left ventricular dysfunction (9,10).

As a result, developing a strategy aimed at regulating apoptosis

and autophagy is necessary to protect against post-MI cardiac

dysfunction. Therefore, the accurate molecular mechanisms that

regulate apoptotic and autophagic responses are pivotal for

preventing the development of heart failure post MI.

The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly

conserved serine/threonine kinase, belonging to the

phosphoinositide kinase-related kinase family (11). mTOR has been reported to activated

via the protein kinase B/phosphoinositide 3 kinase pathway

(12). This signaling mechanism

is centrally involved in physiological hypertrophy but also takes

part in pathological remodeling of the heart (12). It is well established that mTOR

plays an important role in regulating cellular physiology,

metabolism and stress responses (11). Previous studies have confirmed

that mTOR can concurrently modulate apoptosis and autophagy related

pathogenesis in numerous heart diseases (13-15). Furthermore, inhibiting mTOR

induced apoptosis and autophagy may exert a protective influence

against MI injury (16,17). The exact mechanisms explaining how

this signaling pathway regulates apoptosis and autophagy during MI

remain to be clarified.

Regulated in development and DNA damage response-1

(Redd1), located on chromosome 10 (10q22.1), is a 232 amino acids

protein which is transcriptionally induced by DNA damage in various

types of cells (18,19). Redd1 plays a vital role in

biological, physiological functions and cellular functions, such as

cell growth, inflammation and autophagy (20-22). Despite its relationship with mTOR

and extensive research in multiple diseases, such as

neurodegenerative disorders (23)

and cancer (24), little is known

about the role of Redd1 in the heart. Few previous studies have

evaluated the hypothesis that Redd1 may have relevance to cardiac

physiopathology. Studies have shown that Redd1 inhibition protected

cardiomyocytes from ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury (25) or methamphetamine-induced

myocardial damage (26).

Paradoxically, Liu et al (27) demonstrated that Redd1 attenuated

cardiac hypertrophy induced by phenylephrine via enhancing

autophagy. These observations imply that Redd1 is possibly

associated with cardiac dysfunction. However, there was no study on

whether Redd1 could ameliorate the prognosis of cardiac dysfunction

post MI. At present, the role of Redd1 in the heart remains

unknown. Nonetheless, extrapolating experimental data from other

cell types, Redd1 appears to play a pivotal role in inhibiting mTOR

activation (28-30).

In this context, the present study aimed to explore

the potential contribution of Redd1 during the development of heart

failure after MI. The study presented here demonstrates the

critical role of Redd1 overexpression in cardiomyocytes during the

chronic phases of MI. A single intravenous injection of an

adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) vector expressing Redd1 reduced

left ventricular dysfunction. In addition, Redd1 improved cardiac

function after myocardial infarction through apoptosis inhibition

and autophagy enhancement mediated by mTOR inactivation. The

results of the present study suggest the critical importance of

Redd1 in the development of heart failure post MI.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 30 C57BL/6 male mice weighing 14-16 g

(4-5 weeks) were purchased from the Beijing HFK Bioscience Co.,

Ltd. Mice were kept in cages at 22±2°C with 40±5% humidity under a

12 h light/dark cycle in the Tongji Medical School Experimental

Animal Center, and fed a chow diet and water. Animal experiments

were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use

of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institute of Health

and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee at Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science

and Technology.

Injection of AAV9 vectors

The AAV9 vectors carrying enhanced green fluorescent

protein (AAV9-GFP) or mouse Redd1 (AAV9-Redd1) were purchased from

Weizhen Biotechnology Company. The sequence of the Redd1 vector was

consistent with the coding sequence of mouse Redd1, shown as

follows,

ATGCCTAGCCTCTGGGATCGTTTCTCGTCCTCCTCTTCCTCTTCGTCCTCGTCTCGAACTCCGGCCGCTGATCGGCCGCCGCGCTCCGCCTGGGGGTCTGCAGCCAGAGAAGAGGGCCTTGACCGCTGCGCGAGCCTGGAGAGCTCGGACTGCGAGTCCCTGGACAGCAGCAACAGTGGCTTCGGGCCGGAGGAAGACTCCTCATACCTGGATGGGGTGTCCCTGCCCGACTTTGAGCTGCTCAGTGACCCCGAGGATGAGCACCTGTGTGCCAACCTGATGCAGCTGCTGCAGGAGAGCCTGTCCCAGGCGCGATTGGGCTCGCGGCGCCCTGCGCGTTTGCTCATGCCGAGCCAGCTGGTGAGCCAGGTGGGCAAGGAACTCCTGCGCCTGGCATACAGTGAGCCGTGCGGCCTGCGGGGGGCACTGCTGGACGTGTGTGTGGAGCAAGGCAAGAGCTGCCATAGCGTGGCTCAGCTGGCCCTCGACCCCAGCCTGGTGCCCACCTTTCAGTTGACCCTGGTGCTGCGTCTGGACTCTCGCCTCTGGCCCAAGATCCAGGGGCTGTTAAGTTCTGCCAACTCTTCCTTGGTCCCTGGTTACAGCCAGTCCCTGACGCTAAGTACCGGCTTCAGAGTCATCAAGAAGAAACTCTACAGCTCCGAGCAGCTGCTCATTGAAGAGTGTTGA.

Mice were injected with viral solution (2.8×1011 vector

genomes per mouse) via the tail vein 4 weeks before MI surgery

(31).

MI surgery and experimental groups

MI was induced by permanent ligation of the

left-anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as previous reported

(32). Briefly, mice were

anesthetized with 3% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) by

intraperitoneal injection. Mice were mechanically ventilated. A

thoracotomy was conducted between the left third and fourth ribs.

The thymus was retracted upwards and the auricular appendix was

exposed. The LAD was ligated by a 6-0 silk suture. The sham group

mice underwent the same process except for ligating the LAD. Mice

were randomly divided into four groups: Sham with AAV9-GFP

(Sham+GFP; n=6), Sham with AAV9-Redd1 (Sham+Redd1; n=6), MI with

AAV9-GFP (MI+GFP; n=8) and MI with AAV9-Redd1 (MI+Redd1; n=8). Mice

were treated with AAV9-Redd1 or AAV9-GFP for 4 weeks before MI or

sham operation. Mice were sacrificed at 4 weeks post MI or sham

surgery.

Echocardiography

A total of 4 weeks following MI, mice were

anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane via inhalation (33). The depth of anesthesia was

determined by immobility and assessing the absence of the

withdrawal reflex of the right paw. Subsequently, cardiac function

was measured by transthoracic echocardiography with a Vevo 2100

high-resolution micro imaging system (VisualSonics, Inc.). The

echocardiography images were acquired from the long axes and the

short axis. The following parameters were measured in M-mode: Left

ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDd) and left ventricular

end-systolic diameter (LVESd). The percentage of left ventricular

fractional shortening (LVFS, %) and left ventricular ejection

fraction (LVEF, %) were automatically calculated. The parameters

were acquired and averaged from six cardiac cycles.

Masson's trichrome staining and

picrosirius red staining

Heart tissues were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde

for 24 h at room temperature, subsequently paraffin embedded and

sectioned into 5 µm thick slices. Masson's trichrome and

picrosirius red staining were carried out in accordance with

standard procedures (34). The

stained sections were used to estimate scar thickness, infarct size

and expansion index as previously stated (35,36). Picrosirius red staining was

applied to calculate the percentage of collagen content in the

border zone of the infarcted heart. The images were acquired at

×200 magnification in the border zone of the infarct area, using a

light microscope (Olympus Corporation), and analyzed with Image-Pro

Plus software 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc.).

Immunofluorescent assay

Paraffin slides were deparaffinized for

immunofluorescent staining. All sections were incubated with

primary antibodies for Redd1 (1:50; cat. no. ab106356; Abcam) and

LC3B (1:50; cat. no. Arg55799; Arigo Biolaboratories, Corps.) at

4°C overnight. Fluorescein tetramethylrhodamine-conjugated

secondary antibody affinipure goat anti-rabbit Immunoglobulin G

(H+L; 1:50; cat no. 111-025-144; Jackson ImmunoResearch Europe,

Ltd.,) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, all slides

were stained with 300 nM DAPI (D1306, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) for 5 min at room temperature. In each sample,

three random fields were observed by fluorescence microscopy at

×200 magnification. The relative fluorescence intensity was

estimated with ImageJ software (version 1.51, National Institutes

of Health).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl-transferase

mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The cardiac cell apoptosis level in the infarct zone

of the heart was determined by TUNEL staining. In accordance with

the manufacturer's protocol supplied by the TUNEL detection kit

(Roche Diagnostics), the heart sections were treated with TUNEL

reagent for 1 h at 37°C. Subsequent to washing with twice PBS, the

sections were counterstained with 300 nM DAPI (D1306, Invitrogen;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for 5 min at room temperature. In

each sample, images of three random fields were captured with a

100X lens by fluorescence microscopy. The percentage of positive

apoptotic cells was estimated with ImageJ software.

Tissue separation

The atrial tissue was removed and the left ventricle

was cut open. The infarct tissue and the border tissue were

separated from the heart for western blotting and PCR analysis. As

shown in Fig. 1A, the infarcted

area was thin and pale, located within the black solid line. The

border zone was a transitional pink area, thinner than normal

myocardial tissue, located between the black solid line and the

black dotted line (37).

Western blotting

The myocardial total protein was extracted using

with RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at 4°C

for 30 min, then quantified with a bicin-choninic acid kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal amounts of denatured

protein samples (100 µg) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and

were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The nitrocellulose

membranes were blocked in 5% milk diluted with TBS/0.1% Tween-20

(TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, following by primary antibody

incubation overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies were as

follows: Anti-β tubulin (1:1,000; cat. no. 66240-1-Ig, ProteinTech

Group, Inc.); anti-Redd1 (1:1,000; cat. no. ab106356; Abcam);

anti-Bcl2 (1:1,000; cat. no. A11025, Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.);

anti-Bax (1:1,000; cat. no. A12009; Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.);

anti-LC3B (1:1,000; cat. no. Arg55799; Arigo Biolaboratories,

Corps.); and anti-Beclin1 (1:1,000; cat. no. A7353; Abclonal

Biotech Co., Ltd.); anti-total-mTOR (1:1,000; cat. no. A2445;

Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.); anti-phosphorylated (phospho)-mTOR

(1:1,000; cat. no. AP0094; Abclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.),

anti-total-P70/S6 kinase [1:1,000; cat. no. 2708t; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc., (CST)]; anti-phospho-P70/S6 kinase (1:1,000; cat.

no. 9208t; CST); anti-total-4EBP1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 9644t; CST);

anti-phospho-4EBP1 (1:1,000; cat. no. 9451t; CST). The membranes

were washed with TBST 3 times, following by incubation with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies anti-rabbit IgG (H+L; 1:2,000;

cat. no. ANT020) and anti-mouse IgG (H+L; 1:2,000; cat. no. ANT019;

both Antgene Biotechnology co., Ltd.) for 2 h at room temperature.

Bands were detected with a chemiluminescence detection System (ECL;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and quantified by densitometry

using ImageJ software.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Myocardial total RNA was extracted with TRIzol

reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Complementary

DNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT Master Mix kit (Takara

Bio, Inc.) and then used for qPCR with a SYBR-Green Master Mixture

(Takara Bio, Inc.) on the ABI StepOnePlus RT-PCR system (Applied

Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The reverse

transcription conditions were as follows: 37°C for 15 min and 85°C

for 5 sec. The qPCR cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C for 10

min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 15 sec. qPCR was

performed with 3 replicates of each sample. The relative expression

quantity was analyzed by normalizing to the GAPDH level and

calculated with the 2−ΔΔCq method (38). The primers were as follows: 5′-AGG

TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG-3′ and 5′-AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG-3′

for GAPDH, 5′-GCT TCC AGG CCA TAT TGG AG-3′ and 5′-GGG GGC ATG ACC

TCA TCT T-3′ for natriuretic peptide type A (ANP), 5′-GAG GTC ACT

CCT ATC CTC TGG-3′ and 5′-GCC ATT TCC TCC GAC TTT TCT C-3′ for

natriuretic peptide type B (BNP), 5′-ACT GTC AAC ACT AAG AGG GTC

A-3′ and 5′-TTG GAT GAT TTG ATC TTC CAG GG-3′ for myosin heavy

polypeptide 7 (β-MHC), 5′-GCT CCT CTT AGG GGC CAC T-3′ and 5′-CCA

CGT CTC ACC ATT GGG G-3′ for collagen I, 5′-ACG TAG ATG AAT TGG GAT

GCA G-3′ and 5′-GGG TTG GGG CAG TCT AGT G-3′ for collagen III.

Statistical analysis

Each experiment was repeated ≥3 times. All data were

analyzed by Prism 5 (GraphPad Software Inc.) and presented as the

mean ± standard error of the mean. The differences in the data were

analyzed. Unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test was used for two

groups. One-way analysis of variance was used for multiple

comparisons. Post hoc differences were determined by Newman Keuls

test. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

Redd1 is downregulated in the heart

during the myocardial infarction process

To investigate whether Redd1 is involved in MI,

LAD-induced MI models were used (Fig.

1A). Redd1 mRNA and protein levels in the infarct zone declined

significantly at different time points (1 and 4 weeks) after MI

compared with sham-operation animals (P<0.001; Fig. 1B, D and E). Meanwhile, Redd1 mRNA

and protein expression declined significantly in different regions

(border area and infarct area) at 4 weeks compared with the sham

group (P<0.05; Fig. 1C, F and

G). These data indicate that Redd1 expression in the heart is

downregulated during MI, suggesting that Redd1 may participate in

the process of MI.

Redd1 overexpression protects against

cardiac dysfunction after MI

To investigate the influence of Redd1 on cardiac

dysfunction and remodeling post-MI, AAV9-Redd1 or control AAV9-GFP

was injected via the tail vein 4 weeks prior to permanent LAD

ligation. A total of 8 weeks after injection, AAV9-Redd1 group

displayed increased fluorescence intensity of Redd1 compared with

the AAV9-GFP group (Fig. 2A and

B). In addition, heart Redd1 protein level was increased nearly

three times in the sham operation mice injected with AAV9-Redd1

compared with the sham operation mice injected with AAV9-GFP.

Notably, the heart Redd1 protein level was also increased in MI

mice injected with AAV9-Redd1 compared with MI mice injected with

AAV9-GFP (Fig. 2C and D). In line

with preceding studies, the present study discovered that mice

undergoing MI surgery exhibited decreased LVEF and LVFS, as well as

increased LVEDd and LVESd (39,40), suggesting that MI surgery

successfully leads to cardiac insufficiency and ventricular

dilatation (Fig. 2E). Parameters

of echocardiography in mice at 4 weeks after sham or MI surgery are

listed in Table I. Redd1

overexpression significantly increased LVEF and LVFS (P<0.001;

Fig. 2F and G), while LVEDd and

LVESd were attenuated (Fig. 2H and

I). Sham+Redd1 group mice displayed no significant changes

compared with Sham+GFP group mice. Consistently, the MI+Redd1 group

mice also displayed decreased mRNA levels of ANP and BNP compared

with the MI+GFP group mice in the border zone (Fig. 2J and K). The β-MHC mRNA level was

also slightly decreased after the AAV-Redd1 injection but not

significantly (Fig. 2L).

Collectively, Redd1 overexpression protected against cardiac

dysfunction and cardiac dilatation at 4 weeks after MI after

MI.

| Figure 2Redd1 overexpression protects against

cardiac dysfunction after MI. (A) The temporal expression pattern

of Redd1 tested in fluorescence in the heart of AAV9-GFP and

AAV9-Redd1 mice. (B) Quantitative results of Redd1 fluorescence

intensity (n=6). (C) Protein expression of Redd1 at 4 weeks

following MI in the myocardium of mice treated with AAV9-GFP or

AAV9-Redd1 and (D) the quantitative analysis (n=6-8). (E)

Representative M-mode echocardiography image of the LV from the

four groups at 4 weeks after MI. (F-I) Quantitative results of (F)

LVEF, (G) LVFS, (H) LVESd and (I) LVEDd of mice from the four

groups at 4 weeks after MI (n=6-8). (J) ANP, (K) BNP and (L) β-MHC

determined by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR assay (n=6-8).

Data presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

&P<0.05, &&P<0.01 and

&&&P<0.001 vs. Sham+GFP group;

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the MI+GFP group. Redd1, regulated in

development and DNA damage response-1; MI, myocardial infarction;

AAV9, adeno-associated virus 9; GFP, green fluorescent protein; LV,

left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS,

left ventricular fractional shortening; LVEDd, left ventricular

end-diastolic diameter; LVESd, left ventricular end-systolic

diameter; ANP, natriuretic peptide type A; BNP, natriuretic peptide

type B; β-MHC, myosin heavy polypeptide 7. |

| Table IParameters in mice at 4 weeks after

sham or MI surgery. |

Table I

Parameters in mice at 4 weeks after

sham or MI surgery.

| Parameters | Sham+GFP (n=6) | Sham+Redd1

(n=6) | MI+GFP (n=8) | MI+Redd1 (n=8) |

|---|

| LVEF (%) | 67.10±1.84 | 64.58±2.35 | 9.55±2.01a | 20.23±1.59b |

| LVFS (%) | 36.63±1.44 | 34.76±1.73 | 4.00±0.89a | 9.17±0.76b |

| LVEDd (mm) | 3.71±0.04 | 3.68±0.06 | 5.54±0.10a | 4.85±0.19b |

| LVESd (mm) | 2.35±0.04 | 2.40±0.08 | 5.42±0.06a | 4.52±0.12b |

Redd1 overexpression protects against

cardiac expansion and fibrosis after MI

To determine cardiac dilatation post MI, heart

tissues were stained with Masson's trichrome 4 weeks after MI

(Fig. 3A). In the present study,

the MI+Redd1 group displayed a reduced heart expansion index, as

well as unaltered scar size and wall thickness compared with the

MI+GFP group (Fig. 3B-D).

Meanwhile, to analyze cardiac fibrosis, heart tissues were stained

with picrosirius red staining in the border zone. The MI+Redd1

group displayed less collagen content compared with the MI+GFP

group (Fig. 3E and F).

Furthermore, MI+Redd1 group mice also exhibited lower mRNA levels

of collagen I and collagen III compared with MI+GFP group mice

(Fig. 3G and H). Collectively,

Redd1 over-expression protected against cardiac expansion and

fibrosis after MI.

Redd1 overexpression inhibits myocardial

apoptosis after MI

In order to explore the effect of Redd1 on cardiac

cell apoptosis in the infarct zone, TUNEL staining was conducted. A

total of 4 weeks after MI, it was found that the MI+Redd1 group

mice displayed decreased TUNEL-positive cells compared with the

MI+GFP group (Fig. 4A and B). In

addition, the expression of Bcl-2 family members in the infarct

zone was examined through western blot assay. The MI+Redd1 group

mice exhibited a significant increase in the expression of Bcl-2

and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax compared with MI+GFP group mice

(P<0.01; Fig. 4C and D). These

results showed that Redd1 could attenuate cardiac cell apoptosis in

response to ischemia injury.

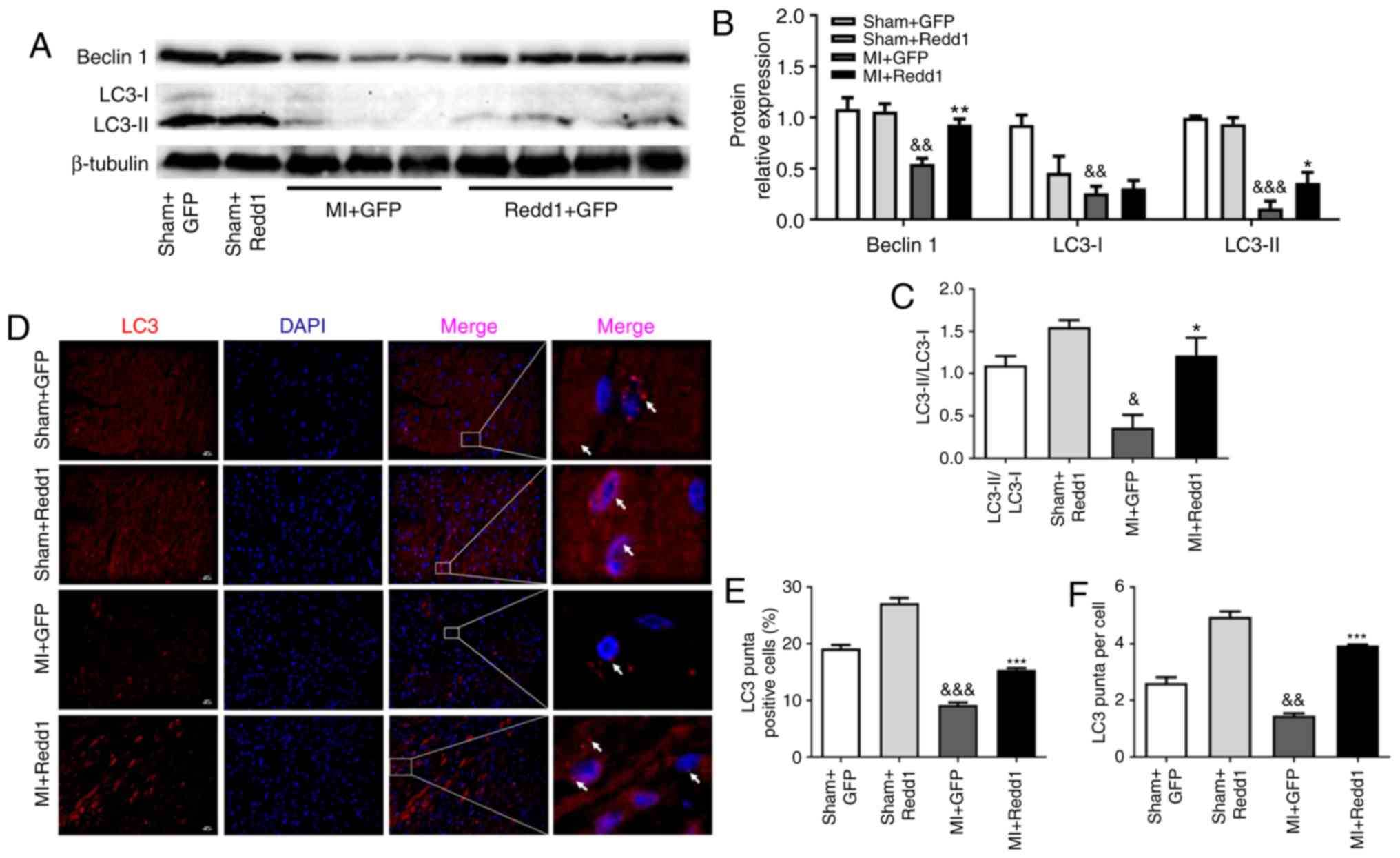

Redd1 overexpression enhances myocardial

autophagy after MI

To investigate the effect of Redd1 on myocardial

autophagy in the border zone of the infarction, LC3 and Beclin1

levels were measured through western blotting. A total of 4 weeks

following LAD ligation, Beclin1 expression and the LC3-II/LC3-I

ratio were increased in the MI+Redd1 group mice compared with in

the MI+GFP group mice (Fig.

5A-C). Similarly, the ratio of LC3 puncta positive cells to the

total cells in the border zone was increased in the MI+Redd1 group

mice compared with in the MI+GFP group mice, as well as LC3 puncta

per cell (Fig. 5D-F). These

results demonstrated that overexpression of Redd1 could improve

cardiac cell autophagy at 4 weeks after MI.

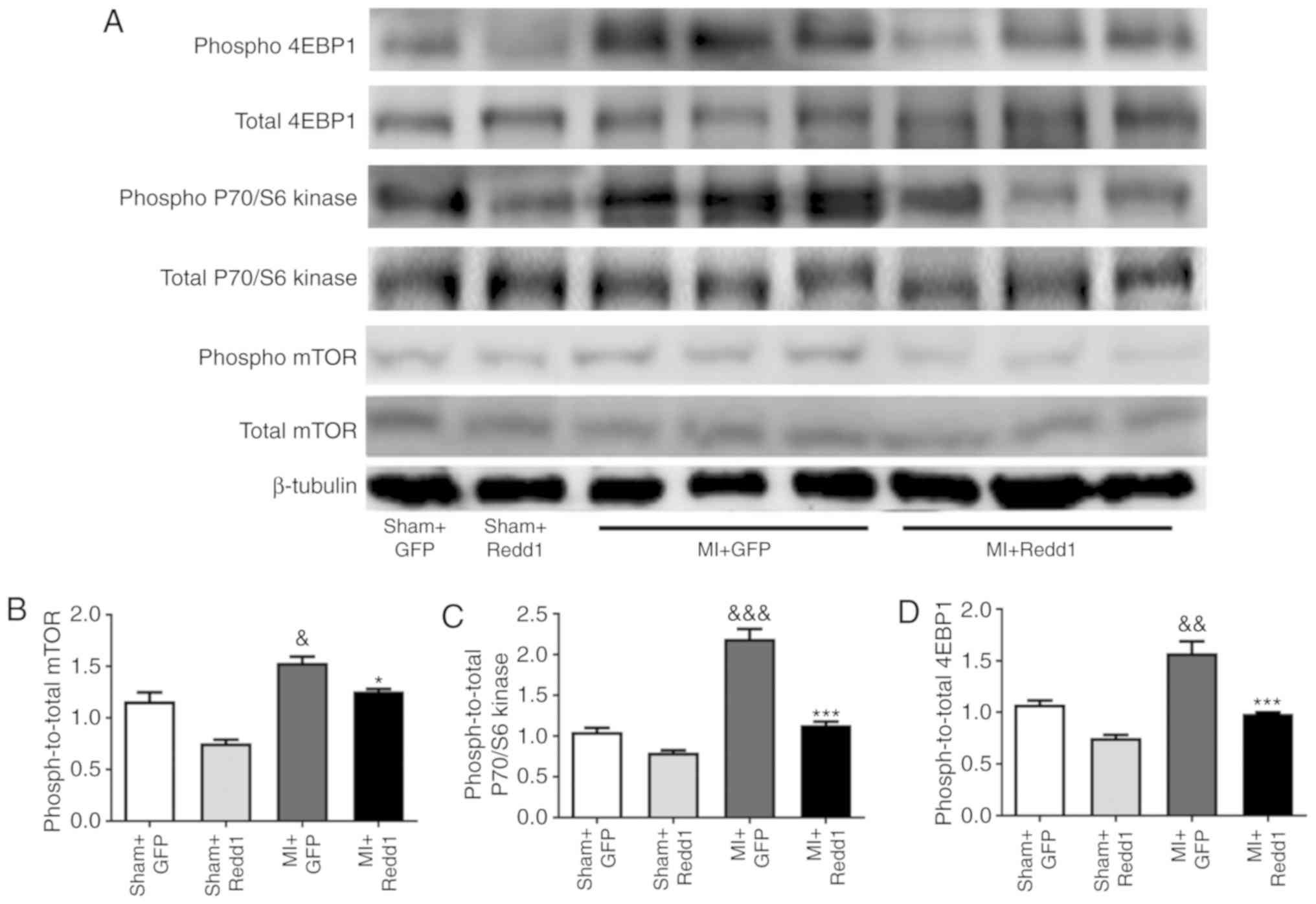

Redd1 overexpression downregulates the

mTOR/P70/S6 kinase/4EBP1 pathway after MI

To further study whether the mTOR signaling pathway

is involved in the regulation of MI mediated by Redd1, the

influence of Redd1 overexpression on mTOR phosphorylation level in

the border zone of the infarction was measured. MI surgery resulted

in increased mTOR phosphorylation, while Redd1 overexpression

partially inhibited this effect (Fig.

6A and B). The phosphorylation state of P70/S6 kinase and 4EBP1

was examined and targets of the mTOR1 complex were established. As

shown in Fig. 6, Redd1 also

significantly decreased the phosphorylation levels of P70/S6 kinase

and 4EBP1 (P<0.001; Fig. 6C and

D). These results suggested that Redd1 could alleviate ischemia

injury induced ventricular dysfunction partly through the mTOR

signaling pathway.

Discussion

MI is a major cause of morbidity and mortality

worldwide (1,2). Although significant progress has

been made in minimizing myocardial loss after MI, large numbers of

patients still develop heart failure due to myocardial remodeling

(41). The present study

demonstrated a critical role for Redd1 in post-MI cardiac

dysfunction. The Redd1 expression level decreased in different

regions (border area and infarct area) of the infarcted myocardium

at 4 weeks. Cardiac-specific overexpression of Redd1 improved

cardiac function and decreased cardiac dilatation. This protective

effect was produced via inhibiting apoptosis and enhancing

autophagy. This pattern indicates that Redd1 plays a protective

role in myocardial ischemia injury.

Redd1 has been identified as a critical

stress-regulated protein whose expression is transcriptionally

induced in various types of cells by DNA damage involved in a

variety of physiological and pathological processes (18). Most studies indicate that Redd1

serves an important role in inflammation and autophagy (20-22). In addition, Liu et al

(27) explored whether Redd1

attenuated cardiac hypertrophy induced by phenylephrine via

enhancing autophagy. Consistent with these results, the present

study also demonstrated the protective effect of Redd1 in post-MI

cardiac dysfunction. Paradoxically, previous studies have

illustrated that inhibition of Redd1 could protect cardiac against

I/R injury (42,43). Recently, Gao et al

(44) demonstrated that increased

Redd1 expression contributed to I/R injury by exaggerating

excessive autophagy during reperfusion. The present study supposed

that the contradictory conclusion was due to the different models,

as Hashmi and Al-Salam (45) has

declared that the processes of cardiomyocyte injury in MI and I/R

were indeed distinct. In addition, the local microenvironment of

the myocardium determined the particular roles of molecules and

enzymes that were part of their pathogenesis. Actually, the

pathological changes, such as inflammation, apoptosis and autophagy

in MI vary along with time (46).

It makes more sense for further experiments to explore the

functions of Redd1 in different periods of MI.

To inspect the underlying mechanism that Redd1

protects against cardiac remodeling and dysfunction, the present

study investigated the effect of Redd1 on cardiac fibrosis and

apoptosis. The occurrence of cardiac fibrosis has been identified

as a definitive characteristic of pathological remodeling and

results in cardiac dysfunction post MI (47). Previous research has demonstrated

that cardiac fibrosis not only causes systolic dysfunction, but

also interrupts the coordination of myocardial

excitation-contraction coupling (48). The results of the present study

showed that overexpression of Redd1 alleviated heart failure and

cardiac fibrosis induced by MI in vivo, as indicated by

increased cardiac function and decreased collagen content.

Apoptosis, a process of programmed cell death, has been identified

in the pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia injury (7,49)

and could determine the fate of the heart (50). In the present study, Redd1

overexpression could inhibit myocardial apoptosis in post-MI hearts

in vivo. The results indicate that Redd1 can inhibit

apoptosis by upregulating the expression of anti-apoptotic

molecules Bcl-2 and the ratio of Bcl-2/Bax. However, the exact

mechanism underlying Redd1-mediated apoptosis inhibition post MI is

not well understood.

Autophagy is a crucial intracellular process which

can increase protein turnover and may be involved in preventing the

accumulation of aberrant proteins or impaired organelles (51). Autophagy deficiency may be

responsible for polyubiquitinated protein accumulation and

endoplasmic reticulum stress elevation (52). Autophagy seems to regulate cardiac

homeostasis in response to various stresses and has a protective

role in the cardiac response to ischemia by removing damaged

mitochondria (8,53). A previous study demonstrated that

impaired autophagy contributes to adverse cardiac remodeling post

MI (54). It has been reported

that enhancing autophagy could decrease infarction size and

alleviate adverse cardiac remodeling (55), while suppressing autophagy led to

adverse cardiac remodeling following MI. The results revealed that

autophagy plays a dynamic role in the determination of infarct size

and cardiac function. In line with the previous studies, the

present study observed that the cardiac cells of MI mice exhibited

a lower rate of autophagy (46,56). This was indicated by 2

well-defined markers of Beclin1 (an indicator of autophagy

induction) and conversion of LC3-I to lipidated LC3-II (an index of

autophagosome abundance), which suggested that impaired autophagy

was related to the pathological mechanism of cardiac remodeling in

response to MI. However, Redd1 over-expression improved cardiac

cell autophagy, accompanied by elevated heart function and reduced

cardiac expansion. Based on these results, it can be concluded that

Redd1 serves a protective role in enhancing autophagy, therefore

ameliorating cardiac remodeling post MI.

mTOR is recognized as a highly conserved

serine/threonine kinase that controls cellular metabolism and

growth in response to diverse stimuli (11,57,58). Studies have demonstrated that mTOR

is necessary for embryonic cardiovascular development (59,60). However, selective pharmacological

and genetic inhibition of mTOR was shown to reduce myocardial

damage after acute and chronic MI (17). Previous studies have demonstrated

that mTOR and its downstream signaling pathways can concurrently

regulate apoptosis and autophagy (13-15). Furthermore, inhibiting mTOR

induced apoptosis and autophagy may exert a protective influence

against MI injury (16,17). Consistent with a previous study,

the current results revealed that the phosphorylation of mTOR and

its downstream signaling pathways were induced in response to MI,

along with increased apoptosis and decreased autophagy.

Additionally, Redd1 overexpression could inhibit apoptosis and

enhance autophagy, as well as suppress the phosphorylation of mTOR.

Accordingly, the results of the present study suggest that the

inhibition of mTOR signaling pathway contributes to the protective

effects of Redd1 on reducing apoptosis and improving autophagy in

the myocardium in response to MI surgery. Therefore, the authors

speculated that Redd1 protected against cardiac dysfunction and

remodeling through inhibiting the mTOR pathway.

In conclusion, the results of the present study have

provided the new insight that Redd1 exerts a beneficial influence

in improving cardiac dysfunction post-infarction. The cardiac

protective effects of Redd1 post MI are associated with the

inhibition of apoptosis and the improvement of autophagy. Redd1

exerts its effect, at least in part, by suppressing the mTOR

signaling pathway. However, the precise mechanism by which Redd1

regulates apoptosis and autophagy remains to be elucidated, and

further investigations are underway. From the clinical point of

view, Redd1 could potentially be a therapeutic candidate for the

prevention and treatment of MI-induced irreversible myocardial

remodeling and heart failure, reducing the risk of mortality. From

a clinical point of view, Redd1 could potentially be a promising

therapeutic candidate for patients with MI and other cardiovascular

diseases.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National

Nature Science Foundation of China (grant no. 8157051059), the

National Nature Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81601217)

and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (grant no.

2017CFB627).

Availability of data and materials

The analyzed datasets generated during the study are

available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

PPH designed and performed the study, analyzed the

data and wrote the manuscript. JF contributed to conducting the

experiments, analyzing data and writing the manuscript. LC, CHJ,

KFW and HXL were involved in performing the study. YL and BMQ

contributed to data analysis and interpretation. BLQ and LHL

conceived the study, participated in its design and helped to draft

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All experiments were approved by the Ethics

committee of Tongji Medical college, Huazhong University of Science

and Technology.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Michaud CM: Murray CJ and Bloom BR: Burden

of disease-implications for future research. JAMA. 285:535–539.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Deedwania PC: The key to unraveling the

mystery of mortality in heart failure: An integrated approach.

Circulation. 107:1719–1721. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

White HD, Norris RM, Brown MA, Brandt PW,

Whitlock RM and Wild CJ: Left ventricular end-systolic volume as

the major determinant of survival after recovery from myocardial

infarction. Circulation. 76:44–51. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Gajarsa JJ and Kloner RA: Left ventricular

remodeling in the post-infarction heart: A review of cellular,

molecular mechanisms, and therapeutic modalities. Heart Fail Rev.

16:13–21. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Chen J, Hsieh AF, Dharmarajan K, Masoudi

FA and Krumholz HM: National trends in heart failure

hospitalization after acute myocardial infarction for medicare

beneficiaries: 1998-2010. Circulation. 128:2577–2584. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Liu T, Li H,

Ivessa A, Sciarretta S, Del Re DP, Zablocki DK, Hsu CP, et al: Mst1

inhibits autophagy by promoting the interaction between Beclin1 and

Bcl-2. Nat Med. 19:1478–1488. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Konstantinidis K, Whelan RS and Kitsis RN:

Mechanisms of cell death in heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol. 32:1552–1562. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yan L, Sadoshima J, Vatner DE and Vatner

SF: Autophagy: A novel protective mechanism in chronic ischemia.

Cell Cycle. 5:1175–1177. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hou L, Guo J, Xu F, Weng X, Yue W and Ge

J: Cardiomyocyte dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase1

attenuates left-ventricular remodeling after acute myocardial

infarction: Involvement in oxdative stress and apoptosis. Basic Res

Cardiol. 113:282018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Liu CY, Zhang YH, Li RB, Zhou LY, An T,

Zhang RC, Zhai M, Huang Y, Yan KW, Dong YH, et al: LncRNA CAIF

inhibits autophagy and attenuates myocardial infarction by blocking

p53-mediated myocardin transcription. Nat Commun. 9:292018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Betz C and Hall MN: Where is mTOR and what

is it doing there? J Cell Biol. 203:563–574. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

McMullen JR, Shioi T, Zhang L, Tarnavski

O, Sherwood MC, Kang PM and Izumo S: Phosphoinositide

3-kinase(p110alpha) plays a critical role for the induction of

physiological, but not pathological, cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 100:12355–12360. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Boluyt MO, Zheng JS, Younes A, Long X,

O'Neill L, Silverman H, Lakatta EG and Crow MT: Rapamycin inhibits

alpha 1-adren-ergic receptor-stimulated cardiac myocyte hypertrophy

but not activation of hypertrophy-associated genes. Evidence for

involvement of p70 S6 kinase Circ Res. 81:176–186. 1997.

|

|

14

|

Mazelin L, Panthu B, Nicot AS, Belotti E,

Tintignac L, Teixeira G, Zhang Q, Risson V, Baas D, Delaune E, et

al: mTOR inactivation in myocardium from infant mice rapidly leads

to dilated cardio-myopathy due to translation defects and

p53/JNK-mediated apoptosis. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 97:213–225. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

McMullen JR, Sherwood MC, Tarnavski O,

Zhang L, Dorfman AL, Shioi T and Izumo S: Inhibition of mTOR

signaling with rapamycin regresses established cardiac hypertrophy

induced by pressure overload. Circulation. 109:3050–3055. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Yan L, Guo N, Cao Y, Zeng S, Wang J, Lv F,

Wang Y and Cao X: miRNA145 inhibits myocardial infarctioninduced

apoptosis through autophagy via Akt3/mTOR signaling pathway in

vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Med. 42:1537–1547. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Buss SJ, Muenz S, Riffel JH, Malekar P,

Hagenmueller M, Weiss CS, Bea F, Bekeredjian R, Schinke-Braun M,

Izumo S, et al: Beneficial effects of Mammalian target of rapamycin

inhibition on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial

infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 54:2435–2446. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ellisen LW, Ramsayer KD, Johannessen CM,

Yang A, Beppu H, Minda K, Oliner JD, McKeon F and Haber DA: REDD1,

a developmentally regulated transcriptional target of p63 and p53,

links p63 to regulation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell.

10:995–1005. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tirado-Hurtado I, Fajardo W and Pinto JA:

DNA damage inducible transcript 4 Gene: The switch of the

metabolism as potential target in cancer. Front Oncol. 8:1062018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Brugarolas J, Lei K, Hurley RL, Manning

BD, Reiling JH, Hafen E, Witters LA, Ellisen LW and Kaelin WG Jr:

Regulation of mTOR function in response to hypoxia by REDD1 and the

TSC1/TSC2 tumor suppressor complex. Genes Dev. 18:2893–2904. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lee DK, Kim JH, Kim J, Choi S, Park M,

Park W, Kim S, Lee KS, Kim T, Jung J, et al: REDD-1 aggravates

endotoxin-induced inflammation via atypical NF-κB activation. FASEB

J. 32:4585–4599. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Qiao S, Dennis M, Song X, Vadysirisack DD,

Salunke D, Nash Z, Yang Z, Liesa M, Yoshioka J, Matsuzawa S, et al:

A REDD1/TXNIP pro-oxidant complex regulates ATG4B activity to

control stress-induced autophagy and sustain exercise capacity. Nat

Commun. 6:70142015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Canal M, Romani-Aumedes J, Martin-Flores

N, Pérez-Fernández V and Malagelada C: RTP801/REDD1: A stress

coping regulator that turns into a troublemaker in

neurodegen-erative disorders. Front Cell Neurosci. 8:3132014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ben Sahra I, Regazzetti C, Robert G,

Laurent K, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Auberger P, Tanti JF,

Giorgetti-Peraldi S and Bost F: Metformin, independent of AMPK,

induces mTOR inhibition and cell-cycle arrest through REDD1. Cancer

Res. 71:4366–4372. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Hernandez G, Lal H, Fidalgo M, Guerrero A,

Zalvide J, Force T and Pombo CM: A novel cardioprotective

p38-MAPK/mTOR pathway. Exp Cell Res. 317:2938–2949. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen R, Wang B, Chen L, Cai D, Li B, Chen

C, Huang E, Liu C, Lin Z, Xie WB and Wang H: DNA damage-inducible

transcript 4 (DDIT4) mediates methamphetamine-induced autophagy and

apoptosis through mTOR signaling pathway in cardiomyocytes. Toxicol

Appl Pharmacol. 295:1–11. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu C, Xue R, Wu D, Wu L, Chen C, Tan W,

Chen Y and Dong Y: REDD1 attenuates cardiac hypertrophy via

enhancing autophagy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 454:215–220. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Sciarretta S, Volpe M and Sadoshima J:

Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in cardiac physiology and

disease. Circ Res. 114:549–564. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Volkers M, Konstandin MH, Doroudgar S,

Toko H, Quijada P, Din S, Joyo A, Ornelas L, Samse K, Thuerauf DJ,

et al: Mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 2 protects the heart

from ischemic damage. Circulation. 128:2132–2144. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhao Y, Xiong X, Jia L and Sun Y:

Targeting Cullin-RING ligases by MLN4924 induces autophagy via

modulating the HIF1-REDD1-TSC1-mTORC1-DEPTOR axis. Cell Death Dis.

3:e3862012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Prasad KM, Xu Y, Yang Z, Acton ST and

French BA: Robust cardiomyocyte-specific gene expression following

systemic injection of AAV: In vivo gene delivery follows a poisson

distribution. Gene Ther. 18:43–52. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Wang X, Meng H, Chen P, Yang N, Lu X, Wang

ZM, Gao W, Zhou N, Zhang M, Xu Z, et al: Beneficial effects of

muscone on cardiac remodeling in a mouse model of myocardial

infarction. Int J Mol Med. 34:103–111. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Oliveira AC, Melo MB, Motta-Santos D,

Peluso AA, Souza-Neto F, da Silva RF, Almeida JFQ, Canta G, Reis

AM, Goncalves G, et al: Genetic deletion of the alamandine receptor

MRGD leads to dilated cardiomyopathy in mice. Am J Physiol Heart

Circ Physiol. 316:H123–H133. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jia LX, Qi GM, Liu O, Li TT, Yang M, Cui

W, Zhang WM, Qi YF and Du J: Inhibition of platelet activation by

clopidogrel prevents hypertension-induced cardiac inflammation and

fibrosis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 27:521–530. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Dai W, Hale SL, Martin BJ, Kuang JQ, Dow

JS, Wold LE and Kloner RA: Allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell

transplantation in postinfarcted rat myocardium: Short- and

long-term effects. Circulation. 112:214–223. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hochman JS and Choo H: Limitation of

myocardial infarct expansion by reperfusion independent of

myocardial salvage. Circulation. 75:299–306. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lubbe WF, Peisach M, Pretorius R, Bruyneel

KJ and Opie LH: Distribution of myocardial blood flow before and

after coronary artery ligation in the baboon. Relation to early

ventricular fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 8:478–487. 1974.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Lee EJ, Park SJ, Kang SK, Kim GH, Kang HJ,

Lee SW, Jeon HB and Kim HS: Spherical bullet formation via

E-cadherin promotes therapeutic potency of mesenchymal stem cells

derived from human umbilical cord blood for myocardial infarction.

Mol Ther. 20:1424–1433. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Li Y, Yang R, Guo B, Zhang H and Liu S:

Exosomal miR-301 derived from mesenchymal stem cells protects

myocardial infarction by inhibiting myocardial autophagy. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 514:323–328. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, Dzavik V, Buller

CE, Ruzyllo W, Sadowski ZP, Maggioni AP, Carvalho AC, Rankin JM,

White HD, et al: Long-term effects of percutaneous coronary

intervention of the totally occluded infarct-related artery in the

subacute phase after myocardial infarction. Circulation.

124:2320–2328. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Park KM, Teoh JP, Wang Y, Broskova Z,

Bayoumi AS, Tang Y, Su H, Weintraub NL and Kim IM:

Carvedilol-responsive microRNAs, miR-199a-3p and -214 protect

cardiomyocytes from simulated ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 311:H371–H383. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Zhou Y, Chen Q, Lew KS, Richards AM and

Wang P: Discovery of potential therapeutic miRNA targets in cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther.

21:296–309. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Gao C, Wang R, Li B, Guo Y, Yin T, Xia Y,

Zhang F, Lian K, Liu Y, Wang H, et al: TXNIP/Redd1 signalling and

excessive autophagy: A novel mechanism of myocardial

ischaemia/reper-fusion injury in mice. Cardiovasc Res. Jun

26–2019.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Hashmi S and Al-Salam S: Acute myocardial

infarction and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: A

comparison. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8:8786–8796. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wang X, Guo Z, Ding Z and Mehta JL:

Inflammation, autophagy, and apoptosis after myocardial infarction.

J Am Heart Assoc. 7:pii: e008024. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Creemers EE and Pinto YM: Molecular

mechanisms that control interstitial fibrosis in the

pressure-overloaded heart. Cardiovasc Res. 89:265–272. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Berk BC, Fujiwara K and Lehoux S: ECM

remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. J Clin Invest.

117:568–575. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ren J, Zhang S, Kovacs A, Wang Y and

Muslin AJ: Role of p38alpha MAPK in cardiac apoptosis and

remodeling after myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol.

38:617–623. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Krijnen PA, Nijmeijer R, Meijer CJ, Visser

CA, Hack CE and Niessen HW: Apoptosis in myocardial ischaemia and

infarction. J Clin Pathol. 55:801–811. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Choi AM, Ryter SW and Levine B: Autophagy

in human health and disease. N Engl J Med. 368:1845–1846. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Lekli I, Haines DD, Balla G and Tosaki A:

Autophagy: An adaptive physiological countermeasure to cellular

senescence and ischaemia/reperfusion-associated cardiac

arrhythmias. J Cell Mol Med. 21:1058–1072. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M,

Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B and Sadoshima J: Distinct roles of

autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion: Roles of

AMP-activated protein kinase and Beclin 1 in mediating autophagy.

Circ Res. 100:914–922. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Wu X, He L, Chen F, He X, Cai Y, Zhang G,

Yi Q, He M and Luo J: Impaired autophagy contributes to adverse

cardiac remodeling in acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One.

9:e1128912014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y,

Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, et

al: The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and

in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med. 13:619–624. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Wu P, Yuan X, Li F, Zhang J, Zhu W, Wei M,

Li J and Wang X: Myocardial upregulation of cathepsin D by ischemic

heart disease promotes autophagic flux and protects against cardiac

remodeling and heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 10:pii: e004044.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Jewell JL and Guan KL: Nutrient signaling

to mTOR and cell growth. Trends Biochem Sci. 38:233–242. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Johnson SC, Rabinovitch PS and Kaeberlein

M: MTOR is a key modulator of ageing and age-related disease.

Nature. 493:338–345. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Land SC, Scott CL and Walker D: MTOR

signalling, embryo-genesis and the control of lung development.

Semin Cell Dev Biol. 36:68–78. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Sciarretta S, Forte M, Frati G and

Sadoshima J: New insights into the role of mTOR signaling in the

cardiovascular system. Circ Res. 122:489–505. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|