Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most common degenerative diseases involving the whole joint, which causes joint pain and dysfunction, seriously affecting the quality of life and productivity of patients (1). With the acceleration of aging in the global population, the incidence of OA is increasing on a yearly basis (2). However, the etiology and pathogenesis of OA are complex, and at present there is no means available for effecting the complete cure of OA. Patients with advanced OA inevitably require surgical intervention, which has a huge impact on patients and society (3). Therefore, it is urgently required to search for drugs that can effectively delay or block the progression of OA, and to further explore its pathogenesis in order to elucidate the underlying mechanism.

Subchondral bone is located below the articular cartilage, and remodeling of subchondral bone fulfills an important role in the pathogenesis of OA (4). Under normal physiological conditions, bone remodeling is a dynamically balanced process that is maintained by osteoclast-mediated bone resorption and osteoblast-mediated bone formation. When stimulated by biomechanical or biochemical factors, however, the balance of bone remodeling becomes disrupted (5). In the early stages of OA, osteoclast-mediated bone resorption increases, the microstructure of subchondral bone changes, and the bearing and conduction of mechanical load of articular cartilage are affected, resulting in the degeneration of articular cartilage (6). As the disease progresses, osteoblast-mediated bone formation increases, osteosclerosis occurs in the subchondral bone, and further degeneration of articular cartilage occurs (7). In ovariectomized mice, estrogen deficiency was shown to lead to enhanced osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, a loss of bone mass in the subchondral bone and changes in microstructure, resulting in the degeneration of articular cartilage (8). In a different study, bisphosphonates were used to inhibit abnormal bone resorption mediated by osteoclasts in anterior cruciate ligament transection models of OA, and it was shown that loss of bone mass in the subchondral bone and the degeneration of articular cartilage were both reduced (9). These studies demonstrated that abnormal bone resorption mediated by osteoclasts causes changes in the microstructure and micro-environment of subchondral bone, leading to degeneration of articular cartilage.

Osteoclasts are derived from bone-marrow macrophages and achieve their bone resorptive function courtesy of the decomposing organic and mineral components in bone tissue through secreting acid and proteases (10). The formation and activation of osteoclasts are associated with cytokines in the microenvironment, including NF-κB ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin (OPG), tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) and osteoclast differentiation factor (11-13). The RANKL/RANK/OPG axis has a critical regulatory role in osteoclast formation. RANKL derived from osteoblasts and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) binds to RANK on the surface of osteoclast precursors, which subsequently activates a series of transcription factors, including NF-κB, activator protein 1, AKT and nuclear factor of activated T-cell cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1), and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) associated biomolecules, including ERK, JNK and p38 (14). Activation of these downstream factors initiates the transcription of genes that are associated with osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption function, including the genes encoding tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), cathepsin K (CTSK), calcitonin receptor (CTR) and MMP-9, ultimately resulting in the formation of mature multinucleated osteoclasts (15). OPG is able to act as a decoy receptor, replacing RANK and binding to RANKL, thereby inhibiting the formation and bone resorption of mature osteoclasts (10). C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) is mainly derived from BMSCs and can bind to C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) on the surface of osteoclast precursors to promote cell migration to the bone resorption sites (16). These biomolecules associated with their respective signaling pathways may serve as potential targets for regulating osteoclast formation and function.

Natural plant-derived compounds have received an increasing amount of attention for their beneficial effects in the treatment of certain complex diseases, such as tumors and inflammation (17). Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) is a water-insoluble semisynthetic derivative from artemisinin, an anti-malarial drug derived from the herb artemisia, with few side effects in clinical therapy (18). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated that DHA has a range of cellular biochemical properties, including anti-angiogenic effects (19), anti-proliferation (20) and the induction of cell apoptosis and oxidative stress (21), which all provide evidence in supporting of the fact that DHA functions as an anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory drug (22,23). Feng et al (24) described how DHA can effectively inhibit osteoclastogenesis, thereby preventing breast cancer-induced bone osteolysis through the suppression of the AKT signaling cascade. Li et al (25) found that DHA ameliorates the lupus symptoms of BXSB mice by inhibiting the production of TNF-α and blocking the translocation of NF-κB in its signaling pathway. Zhou et al (26) demonstrated that DHA attenuates bone loss in ovariectomized mice through inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and function, and this group also proposed that DHA may act as a potential treatment option against osteolytic bone diseases. However, the effects of DHA on OA, and the underlying mechanism, have yet to be fully elucidated. Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate the therapeutic effects of DHA on knee OA in rats through in vivo experiments and the creation of a rat OA model; furthermore, the effects of DHA on osteoclast-mediated bone resorption were examined through in vitro experiments, with a view to delineating the possible underlying mechanism.

Materials and methods

Cell isolation and culture

A total of 12 10-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats (Laboratory Animal Center of Ning Xia Medical University, Yinchuan, China; protocol no. 2020-0001) weighing 294±13 g, were group-housed at a constant temperature (25°C), at 55% humidity in a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) and BMSCs were isolated from whole bone marrow of the rats as described previously (27). Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed out of the medullary cavity of the femur and tibia using α modified Eagle's medium (α-MEM, cat. no. 01-042-1ACS; Biological Industries) containing 2% FBS (cat. no. 10099141) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (cat. no. 15140122; both from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), erythrocytes were removed with lysis buffer (cat. no. R1010; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.), and the remaining cells were resuspended in α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 30 ng/ml macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF, cat. no. 216-MC-025; R&D Systems, Inc.) and incubated at a density of 1×106 cells/ml in a 10-cm dish for 24 h. Non-adherent cells were considered as BMMs, which were centrifuged (1,000 × g, 5 min, 20°C) and reseeded in another 10-cm dish and incubated in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C for a further 3-4 days until the cells reached 90% confluence. At the same time, adherent cells continued to be cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and the culture medium was replaced every 2 days until a large number of BMSCs were obtained by cell passage. RAW264.7 cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in α-MEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C and the medium was replaced every 2 days.

Osteoclastogenesis assay in vitro

BMMs were plated into a 96-well plate at a density of 6×103 cells/well and incubated overnight, and subsequently the medium was replaced with fresh α-MEM containing 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL (cat. no. 390-TN-010; R&D Systems, Inc.), and various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 or 5 µM) of DHA (cat. no. D7439; MilliporeSigma). The α-MEM was replaced every 2 days until mature osteoclasts had formed. Cells were stained for TRAP using a kit (cat. no. PMC-AK04F-COS; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd.), following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cells were washed with PBS three times (5 min each wash), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37°C for 15 min, and incubated in the presence of the TRAP solution for 5 min at 20°C. TRAP-positive cells with more than three nuclei were identified as mature osteoclasts and counted, and the number and area of osteoclasts in five fields of view per well were measured using the Olympus DP71 light microscope (Olympus Corporation) (24).

Osteogenic differentiation and mineralization of BMSCs in vitro

Osteogenic differentiation was detected when BMSCs were cultured to 3-5 generations. In brief, BMSCs were plated at a density of 1×105 cells/well into collagenase-treated 6-well plates (cat. no. 354400; Corning, Inc.) and incubated overnight at 37°C, and then simulated with osteogenic medium (α-MEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate and 50 µg/ml ascorbate; cat. no. RASMX-90021; Cyagen Biosciences, Inc.) and various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 and 5 µM) of DHA for 7 and 21 days, with the medium being replaced with fresh medium every 2 days. The alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralization nodules of BMSCs were observed following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at 20°C for 15 min and staining with an ALP detection kit (cat. no. SCR004; MilliporeSigma) in the dark at 20°C for 10 min and 1% alizarin red (cat. no. G1038-100ML; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) at 20°C for 10 min. ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health) was used to measure the percentages of the mineralized area and ALP-positive cells (28).

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay for cell proliferation and viability

CCK-8 kit (cat. no. C0038; Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.) was used to determine the effects of DHA on the proliferation and viability of BMMs and BMSCs, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 6×103 cells/well and incubated overnight. α-MEM containing various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 µM) of DHA were added, and cells were incubated for 96 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 buffer was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for a further 2 h at 37°C. The optical density (OD) was then measured at 450 nm on a Multiskan absorbance microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Cell viability was calculated according to the following formula: Cell viability=(experimental group OD-zeroing OD)/(control group-OD zeroing OD) (24).

Immunofluorescence assay for F-actin rings

Tetraethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated phalloidin [cat. no. 40734ES75; Yeasen Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd.] was used to detect the F-actin rings in osteoclasts, following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, BMMs were seeded into 24-well plates at a density of 2×104 cells/well. Cells were cultured to adhere to the plate overnight at 37°C, and were subsequently cultured with medium containing different concentrations (0, 1 and 5 µM) of DHA, 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL. The medium was replaced every 2 days. After 6 days of culture, cells were washed thrice with preheated (37°C) PBS (5 min each wash), followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde at 20°C for 10 min, and washed three times with PBS again (5 min each wash). Subsequently, the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 (cat. no. 9002-93-1; MilliporeSigma) for 5 min, and washed three times with PBS again (5 min each wash). The cells were then incubated with 200 nM TRITC-conjugated phalloidin diluted in 0.5% (w/v) Invitrogen® BSA (cat. no. D1205; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)-PBS for 1 h at 37°C, washed three times with PBS (5 min each wash), and fluorescence quenching resistant sealing tablets containing DAPI (cat. no. ZLI-9557; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) were used for staining the nuclei at 20°C for 10 min. The F-actin ring distribution was observed using an LSA1 confocal microscope (Nikon Corporation). Finally, the fluorescence images were processed using NIS-Elements AR 4500 software (Nikon Corporation), and the number of intact F-actin rings was counted using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health).

Bone resorption assay

Bone resorption of the osteoclasts was determined using a resorption assay system using cell cultures on bone slices (cat. no. DT-1BON1000; Immunodiagnostic Systems, Ltd.). BMMs were seeded in 96-well plates with bone slices at a density of 6×103 cells/well. Cells were first cultured overnight at 37°C to adhere to the plates, and subsequently were cultured with α-MEM containing different concentrations (0, 1 and 5 µM) of DHA, 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL, the medium was replaced every 2 days. After 8 days of culture, the bone slices were rinsed in PBS, fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 4°C for 7 min, placed in 0.25 M ammonium hydroxide and sonicated three times with 50 Hz (5 min each sonication) to remove the cells. Bone slices were washed in distilled water and dehydrated by passing through graded (40, 75, 80, 95 and 100%) alcohol for 10 min. After being air-dried, bone slices were stained with 0.5% (w/v) aqueous toluidine blue (cat. no. G3668; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) at 20°C for 3 min, and the bone resorption areas were subsequently examined under a light microscope. To detect resorption pits, bone slices were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde at 20°C for 2 h, then fixed in 1% osmic acid at 20°C for a further 2 h, then washed in distilled water and dehydrated by passing through graded (40, 75, 80, 95 and 100%) alcohol for 10 min. The bone slices were then dried by passing through graded (75, 100%) tert-butyl alcohol. Following which, bone slices were sputtered with gold in an airless spray unit, and the presence of resorption pits on bone slices was observed using an S-3400N scanning electron microscope (Hitachi, Ltd.). Finally, the number of resorption pits was measured using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health) (29).

Luciferase assay

RAW264.7 cells were transfected with the pGL4.32 (luc2P/NF-κB-RE/Hygro) vector (NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid, 0.5 µg, cat. no. E8491) and the pGL4.30 (luc2P/NFAT-RE/Hygro) vector (NFAT luciferase reporter plasmid, 0.5 µg, cat. no. E8481; both from Promega Corporation) using the Gene Pulser Xcell™ Electroporation system (cat. no. 165-2660; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for stable transfection, according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the following electroporation parameters: i) Voltage, 200 V; ii) capacitance, 950 µF; iii) pulse duration, 5 msec; iv) number of pulses, 1; and v) electroporator buffer, Opti-MEM (cat. no. 51985091; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The pSV-β-galactosidase control vector (0.5 µg, cat. no. E1081; Promega Corporation) was co-transfected, according to the manufacturer's instructions, for normalization. Cells transfected with NFATc1, NF-κB and β-galactosidase were selected using 400 µg/ml G418 (cat. no. 10131035; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) to investigate NFATc1 and NF-κB activation as described previously (30,31). Briefly, the transfected RAW264.7 cells were plated in 48-well plates at a density of 1×105 or 5×105 cells/well in triplicate. After 24 h, the cells were pretreated with various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 and 5 µM) of DHA for 1 h, and the cells were subsequently incubated with α-MEM containing 50 ng/ml RANKL for 6 h to activate NF-κB, and 24 h to activate NFATc1. Cells were rinsed in PBS buffer, then lysed with cell culture lysis reagent (120 µl/well, cat. no. E1531; Promega Corporation) for 10 min at 4°C, before the supernatant was collected by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 25 min) at 4°C. The luciferase activities of NFATc1 and NF-κB were detected using the Luciferase Assay Kit (cat. no. E1483; Promega Corporation) and normalized to the β-galactosidase activity in each sample.

Western blot assay

BMMs were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and cultured at 37°C to allow the cells to adhere to the plates. BMMs were pretreated with 5 µM DHA for 4 h, and then stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL for the indicated time periods (0, 10, 30 and 60 min and 0, 1, 3 and 5 days). Subsequently, the cells were treated for protein extraction following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the medium was removed, and the cells were collected using 0.25% trypsin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) digestion at 37°C for 3 min. After centrifugation (1,000 × g, 5 min, 20°C) and washing, cells were lysed using a buffer containing protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors from the whole cell lysis assay kit (cat. no. KGP250; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) at 4°C for 20 min. The protein concentrations were quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. KGPBCA; Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) after centrifugation (12,000 × g, 10 min, 4°C). The extracted proteins were then boiled in the loading buffer (cat. no. GH101-01; TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) for 10 min. Total proteins (30 µg) from each group were separated via sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (8 or 12% gels), and then transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) at 20°C for 2 h, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against IκBα (1:1,000; cat. no. 51066-1-AP), NF-κB (1:1,000; cat. no. 66535-1-Ig; both from ProteinTech Group, Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-ERK (1:10,000; cat. no. ab229912), ERK (1:10,000; cat. no. ab184699), p-JNK (1:10,000; cat. no. ab4821), JNK (1:10,000; cat. no. ab179461), p-p38 (1:10,000; cat. no. ab4822), p38 (1:10,000; cat. no. ab170099), NFATc1 (1:10,000, cat. no. ab264530; all from Abcam) and β-actin (1:5,000; cat. no. 20536-1-AP; ProteinTech Group, Inc.). After washing three times with TBST (5 min each wash), the membranes were incubated with goat anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000; cat. no. SA00001-2; ProteinTech Group, Inc.) at 20°C for 1 h. Finally, membranes were soaked in enhanced chemiluminescence reagent (cat. no. KGP1121; Shanghai Beiyi Bioequip Information Co., Ltd.) for 1 min, and imaged. Band intensities were detected, the data were semi-quantified using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health), and are shown relative to the intensity of the β-actin control.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-q) PCR assay

BMMs were plated into 6-well plates at a density of 1×106 cells/well and cultured overnight at 37°C to allow the cells to adhere to the plates. The α-MEM was then replaced with fresh medium containing different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 and 5 µM) of DHA, 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL, and cell culture was allowed to continue with the medium being replaced every 2 days. After 6 days of culture, cells were collected and treated for total RNA isolation using Multisource Total RNA Prep kits (cat. no. AP-MN-MS-RNA-250; Axygen; Corning, Inc.) following the manufacturer's instructions. The same procedure was performed in BMSCs cultured for 14 days with osteogenic medium for osteogenic differentiation. Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 µg total RNA using a TransScript® All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (cat. no. AT341-01; TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's protocol, and an S1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). qPCR was performed to quantify the expression of the target genes during osteoclast formation and the osteoblastic differentiation of BMSCs using PerfectStart™ Green qPCR SuperMix (cat. no. AQ602-21; TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with the following thermocycling conditions: 45 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec; 54°C for 30 sec; and 72°C for 34 sec. The primer sequences are listed in Table I. qPCR for each group was performed in triplicate, and the expression levels of target genes were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCq method (32). The mean Cq value in each experimental group was normalized to the control group, and β-actin was used as the quantitative control gene.

|

Table I

Primer sequences for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

|

Table I

Primer sequences for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

| Genes |

Sequence (5′-3′) |

| CTSK |

F: CGGCTATATGACCACTGCCTTC |

| R: CTCTGTACCCTCTGCACTTAGC |

| CTR |

F: CGAGGATCAACGTCTGCGCT |

| R: AAGTTGACCACCAGAGCCGC |

| TRAP |

F: AGAAAGAGCCACCCGGAGGT |

| R: GTGACAGGCCACAGGCACAT |

| MMP-9 |

F: CTCGGGCACCCAGATGATG |

| R: CTCGGGCACCCAGATGATG |

| RANK |

F: GCCCAGTCTCATCGTCCTGC |

| R: GCCGAGTGGGAACCAACACA |

| CXCR4 |

F: CACACTCCAAGGGCCACCAG |

| R: GCTGGAGCCTCTGCTCATGG |

| Runx 2 |

F: CATCACCGACGTACCCAGGC |

| R: TGGTAGTGATGGTGGCGGA |

| Alp |

F: CGAGGTCACGTCCATCCTGC |

| R: GGGCGCATCTCATTGTCCGA |

| Bglap |

F: GACTCCGGCGCTACCTCAAC |

| R: AGATGCGCTTGTAGGCGTCC |

| β-actin |

F: CTCCATCCTGGCCTCGCTGT |

| R: GCTGTCACCTTCACCGTTCG |

In vivo experiments

A total of 36 10-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats (Laboratory Animal Center of Ning Xia Medical University, Yinchuan; protocol no. 2020-0001) weighing 294±13 g, were group-housed at a constant temperature (25°C) at 55% humidity in a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All 36 rats were randomly divided into three groups, with 12 rats per group: i) The sham-operated group; ii) the destabilization of medial meniscus (DMM) + vehicle group; and iii) the DMM + DHA group. Rats were acclimated for 1 week and anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium in PBS (60 mg/kg). Surgery was performed on the right knee of each rat, as previously described (33). Briefly, the right knee joint capsule of each rat for which DMM surgery was performed was exposed according to a medial parapatellar approach; subsequently, the medial meniscotibial ligament was transected with micro-scissors, and the medial meniscus was reflected proximally towards the femur before suturing the joint capsule and skin with a 5-0 synthetic absorbable suture. By contrast, the rats of the sham-operated group were subjected to the same procedure without transections of medial meniscotibial ligament and medial meniscus. The rats of the DMM + DHA group were subjected to an intraperitoneal injection of DHA at 1 mg/kg every 2 days after the first post-operative day until the time of sacrifice (4 and 8-weeks after the operation). The rats in the sham-operated and DMM + vehicle groups were subjected to an intraperitoneal injection of 1% DMSO as a control. DHA was prepared as described previously in the literature (34). In brief, 25 mg DHA was weighed out and dissolved in 1 ml prepared DMSO, and then diluted in 99 ml sterile PBS solution to prepare a 1 mg/kg DHA. As a vehicle, the sham-operated and DMM + vehicle groups were administered solvent with the same dose, frequency and duration as the DMM + DHA group. A schematic representation of the experimental design is shown in Fig. 1.

|

Figure 1

Schematic diagram of the animal experiment design. DMM, destabilization of medial meniscus; DHA, dihydroartemisinin.

|

All experimental procedures in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Experiment Committee of Ningxia Medical University (approval. no. IACUC-NYLAC-2020-51; Yinchuan, China), and all measures were taken in accordance with the principles and guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (35) to minimize the number and suffering of rats included in this experiment.

Analysis of serum biomarkers

Six rats from each group were fasted, but had free access to water, for 6 h prior to euthanasia. Sodium pentobarbital (1%, 60 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally for anesthesia prior to cardiac puncture, and additional sodium pentobarbital (1%, 100 mg/kg) was injected intraperitoneally for euthanasia in the study. Blood collected at 4 and 8 weeks post-operatively was clotted at 20°C for 30 min, and then centrifuged (4,000 × g, 20 min) at 4°C. Serum was then separated and stored at -80°C. The levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were analyzed using ELISA kits (cat. nos. AE90375Ra and AE91382Ra, respectively; Shanghai Lianshuo Biological Technology Co., Ltd.), as described by the manufacturer (28).

Micro-CT (μCT)

In order to observe the effects of DHA on bone remodeling, a Skyscan 1,176 µCT (Bruker Corporation) was used to examine the microstructural changes in the tibial subchondral bone as described previously (36). Briefly, the knee joints of six rats in each group were collected, and excess soft tissue was dissected. Following fixation using 10% neutral formalin buffer for 48 h at 20°C, the cleaned knee joints were imaged by µCT with the following instrument settings: Resolution, 10 µm/pixel; voltage, 40 kV; current, 250 µA; exposure time, 0.9 sec; and rotation, 0.4° step through 180°. A region of interest was identified as the portion (3.5 mm ventrodorsal length, 0.5 mm below the growth plate and 1 mm in height) of the load-bearing region at the medial tibial plateau to use for determination of the bone parameters, including bone volume fraction (BV/TV), trabecular number (Tb.N), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) and connectivity density (CD).

Histology and immunohistochemistry assay

After fixation using 10% neutral formalin buffer for 48 h at 20°C, the knee joints of six rats in each group were decalcified in 10% disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (cat. no. E8030; BioInsight) for 4 weeks at 20°C prior to embedding in paraffin, and the joints were sectioned at 5-µm thickness along the coronal plane for staining. H&E staining kit (cat. no. G1005; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to calculate the thickness of the hyaline and calcified (CC) cartilage layers, as described previously (37). Briefly, the sections were placed in xylene twice for 15 min, anhydrous ethanol twice (7 min immersion) and finally, in 75% alcohol for 7 min. The sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 min at 20°C, rinsed in running water for 5 min, dehydrated in 85 and 95% alcohol for 10 min each, and finally stained with eosin for 5 min at 20°C. Before staining with Safranin O-Fast Green and TRAP (G1053 and G1050, respectively; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.), the slides were deparaffinized as described above, and subsequently stained with Fast Green for 6 min, washed at 20°C, dehydrated, and stained with Safranin O for 3 min at 20°C. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) scores were graded to evaluate the degeneration of articular cartilage, as described previously (38). TRAP staining was performed to measure the number of mature osteoclasts and the ratio of osteoclast surface per bone surface (Oc.S/BS), as described previously (39). Slides were incubated in working fluid derived from the TRAP staining kit for 2 h, washed three times with distilled water, and subsequently stained with hematoxylin for 5 min at 20°C. After covering the slides with neutral resin, five random views from three sections per rat were visualized using a DP71 light microscope with DP controller 3.3.1.292 software (Olympus Corporation) and quantified using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health).

For immunohistochemistry staining, after decalcification and fixation according to the same conditions described above, slides from each treatment group at 4-weeks after the surgery were incubated with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min at 37°C, and then blocked with 5% BSA (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies (all diluted 1:100) against RANKL (cat. no. 23408-1-AP), CXCL12 (cat. no. 17402-1-AP; both from ProteinTech Group Inc.) and NFATc1 (cat. no. ab264530; Abcam). After washing three times (5 min each wash), sections were incubated with the goat anti-mouse/rabbit poly-HRP secondary antibody (1:200; cat. no. PR30009; ProteinTech Group, Inc.) for 1 h at 37°C, and subsequently 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) (cat. no. ZLI-9018; Beijing Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was added to develop the color prior to counterstaining with hematoxylin for 5 min at 20°C. After covering the slides with neutral resin, positively stained cells from three sections per rat were visualized using a DP71 light microscope with DP controller 3.3.1.292 software (Olympus Corporation) and quantified using ImageJ 1.48v software (National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). An unpaired Student's t-test was used to compare the parameters between two groups, whereas ANOVA followed by Tukey's post-hoc test was used to compare the parameters among ≥3 groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

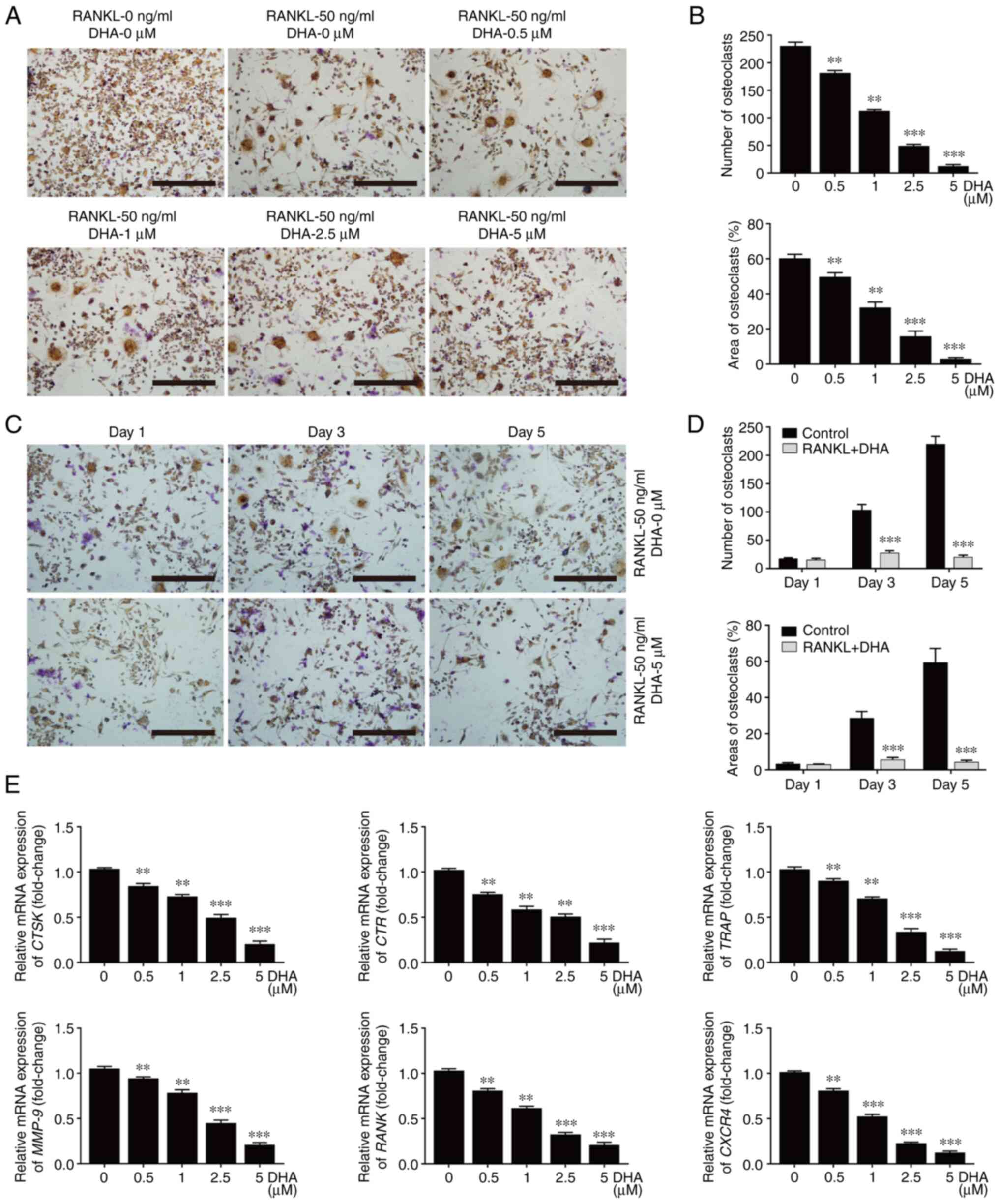

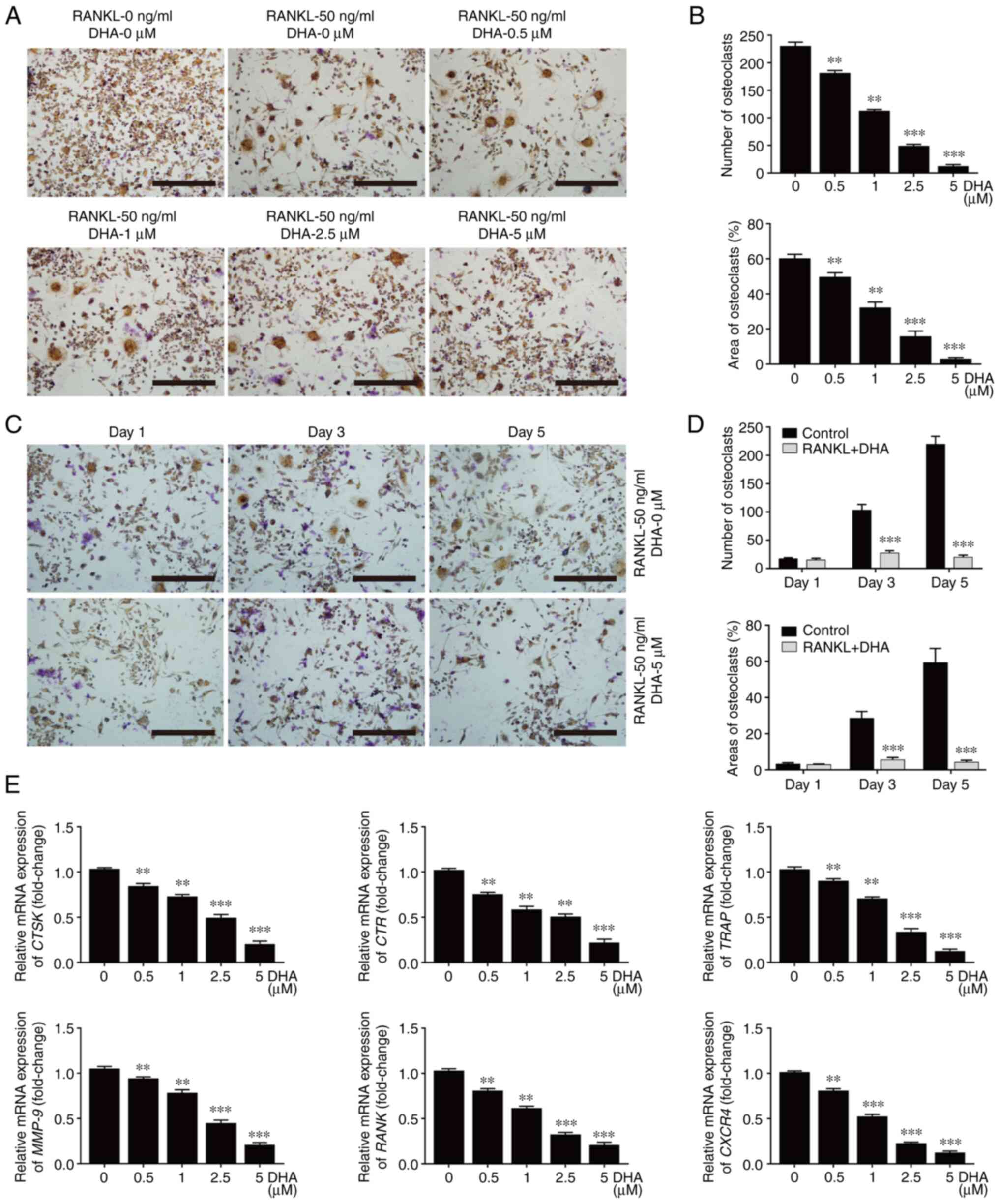

DHA inhibits differentiation of BMMs into osteoclasts in vitro

To ascertain the effects of DHA on the differentiation of BMMs into osteoclasts, the BMMs were first isolated and treated with M-CSF and RANKL in the absence or presence of DHA at various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 or 5 µM). As shown by TRAP staining, BMMs underwent differentiation into mature TRAP-positive multinucleated osteoclasts in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL. On the other hand, the formation of multinucleated osteoclasts was notably suppressed by DHA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). The number of osteoclasts (TRAP-positive with >3 nuclei) was 232.00±3.86 per well in the group treated without DHA, and 11.85±2.20 per well in the group treated with 5 µM DHA (Fig. 2B). Additionally, BMM differentiation was observed by TRAP staining at different time points, and osteoclast formation was found to be notably suppressed after 3 days of treatment with 5 µM DHA (Fig. 2C). The numbers and areas of osteoclasts further supported that DHA could exert an inhibitory effect on the early stage of osteoclastogenesis (Fig. 2D).

|

Figure 2

DHA inhibits RANKL-induced differentiation of BMMs into osteoclasts in vitro. (A) BMMs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL and various concentrations of DHA for 6 days and then subjected to TRAP staining. Scale bar, 200 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of the numbers and areas of osteoclasts from (A). (C) BMMs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL in the presence or absence of 5 µM DHA for 1, 3 and 5 days, and then subjected to TRAP staining. Scale bar, 200 µm. (D) Quantitative analysis of the numbers and areas of osteoclasts from (C). (E) BMMs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL and various concentrations of DHA for 6 days, and subsequently genes associated with osteoclastogenesis were detected using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. n=3 per group. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µM control group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; BMMs, bone marrow-derived macrophages; M-CSF, macrophage-colony stimulating factor; CTSK, cathepsin k; CTR, calcitonin receptor; TRAP, tartrate resistant acid phosphatase; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor kB; CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4.

|

In order to further explore the underlying mechanism of DHA affecting osteoclast formation, the expression levels of genes associated with osteoclastogenesis and function were then examined. In response to RANKL stimulation, the expression levels of genes, including CTSK, CTR, TRAP, MMP-9, RANK and CXCR4 were high in the group treated without DHA. However, the expression levels of these genes were significantly inhibited in a dose-dependent manner in the groups treated with various concentrations of DHA (Fig. 2E).

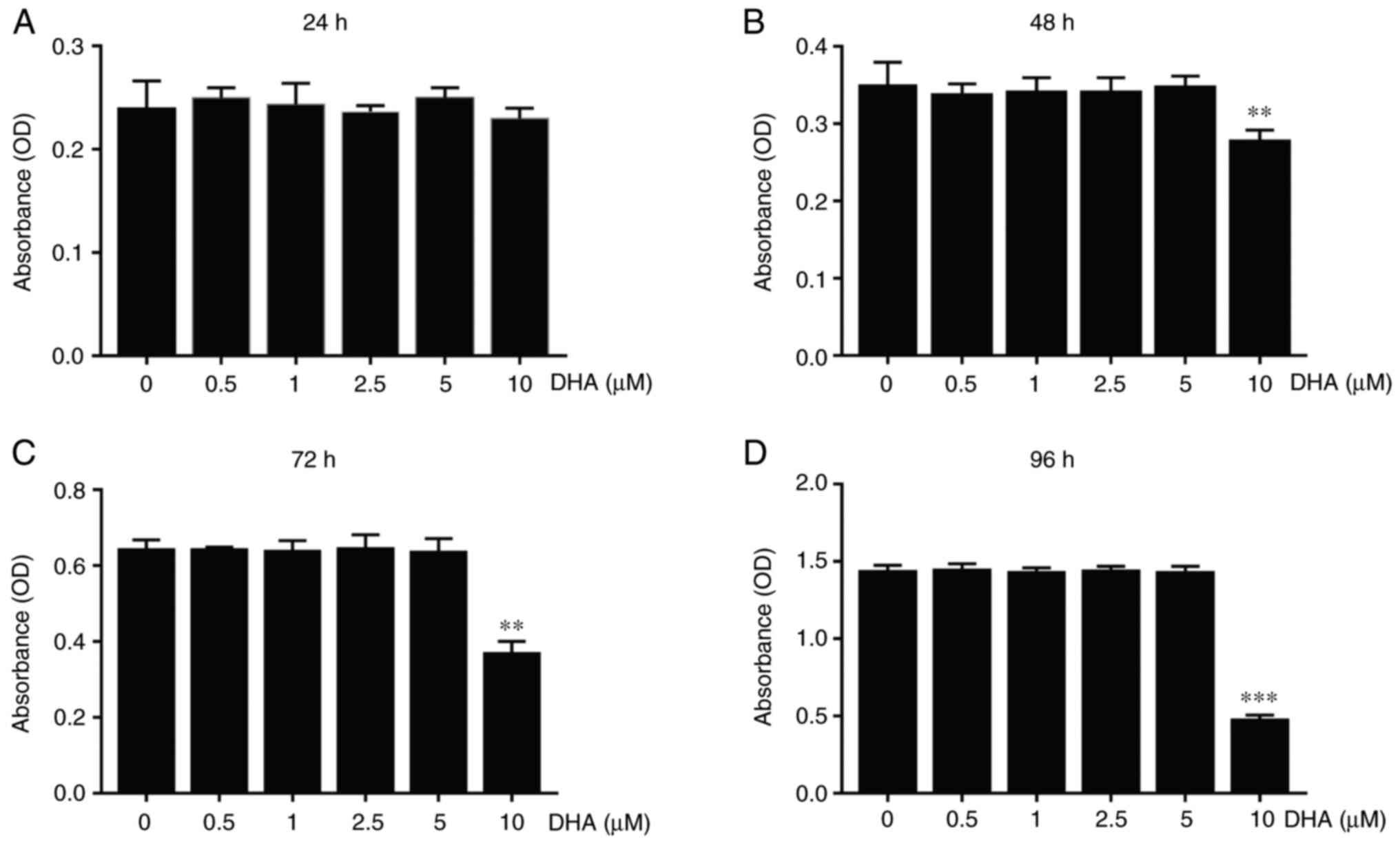

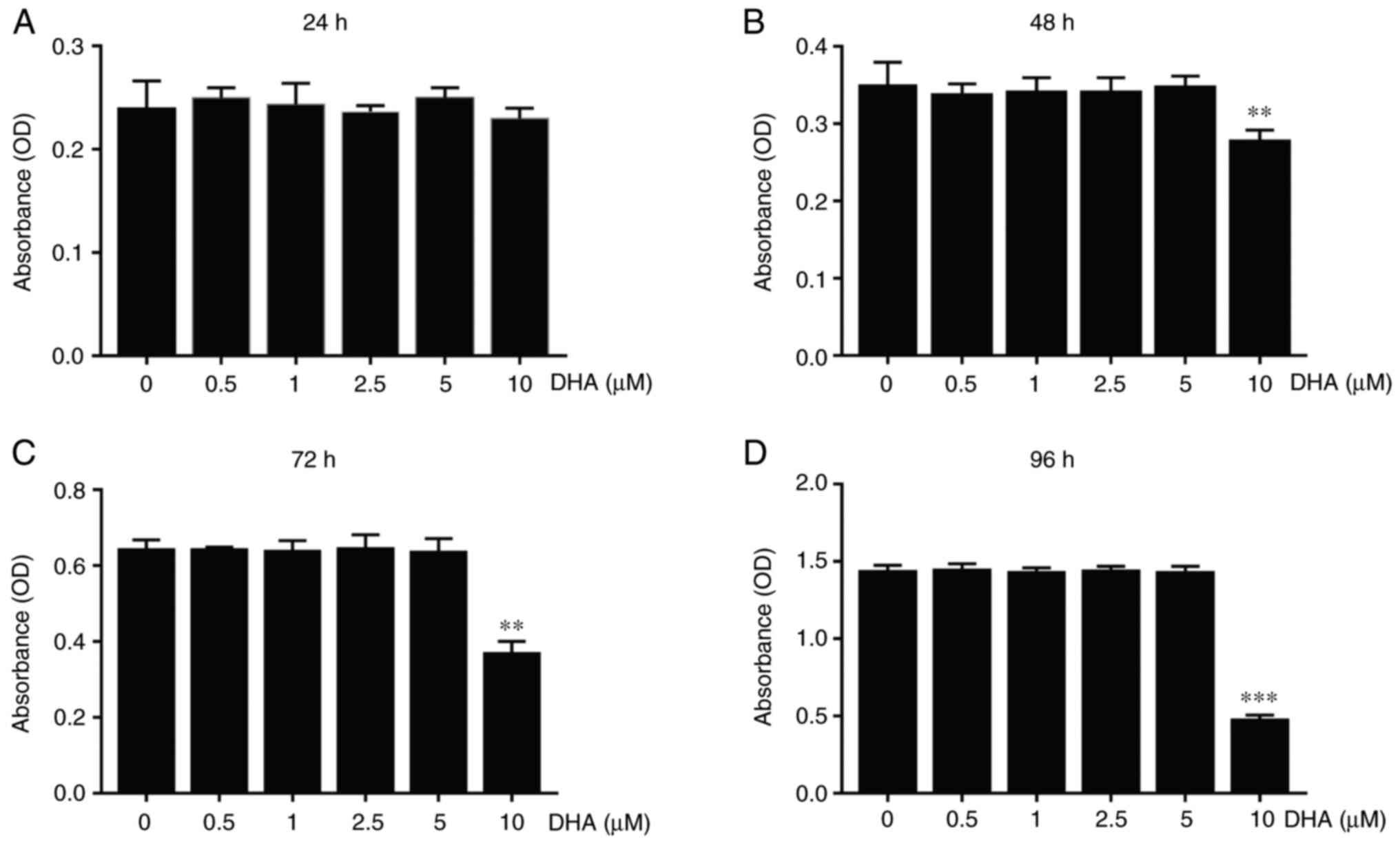

DHA inhibits osteoclast formation without cytotoxicity to BMMs in vitro

To determine whether the inhibitory effect of DHA on osteoclast formation was associated with cytotoxicity, BMM viability assays were performed by using CCK-8. The results obtained demonstrated that DHA did not produce cytotoxicity with BMMs at concentrations below 10 µM (Fig. 3A), at which concentration the formation of osteoclasts was significantly suppressed after 48-96 h of treatment (Fig. 3B-D).

|

Figure 3

DHA inhibits differentiation of BMMs into osteoclasts without cytotoxicity in vitro. BMMs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL and various concentrations of DHA for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, and the cell viability was subsequently measured using Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. The OD values at (A) 24, (B) 48, (C) 72 and (D) 96 h were quantitatively analyzed. n=3 per group. **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µM control group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; BMMs, bone marrow-derived macrophages; M-CSF, macrophage-colony stimulating factor; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; OD, optical density.

|

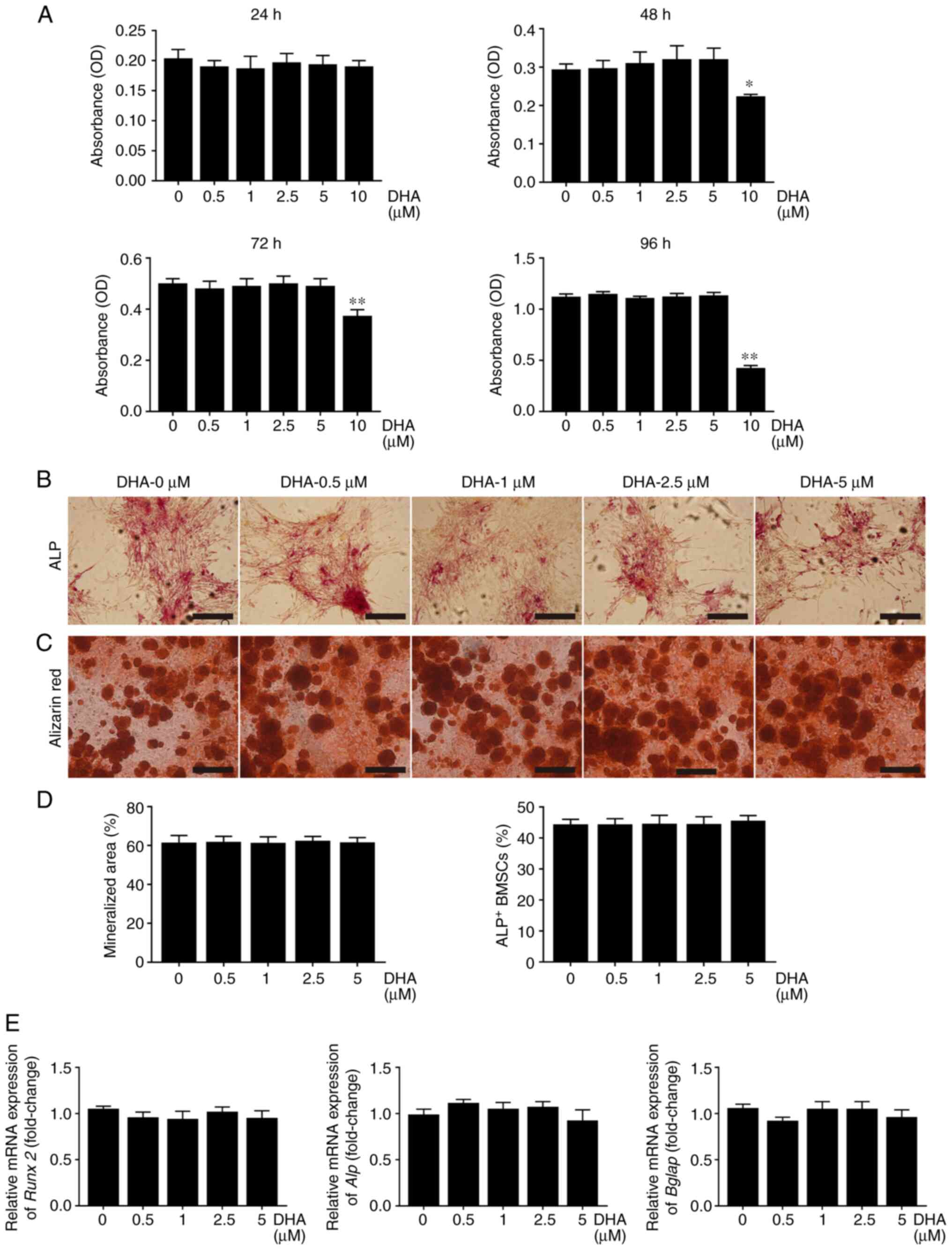

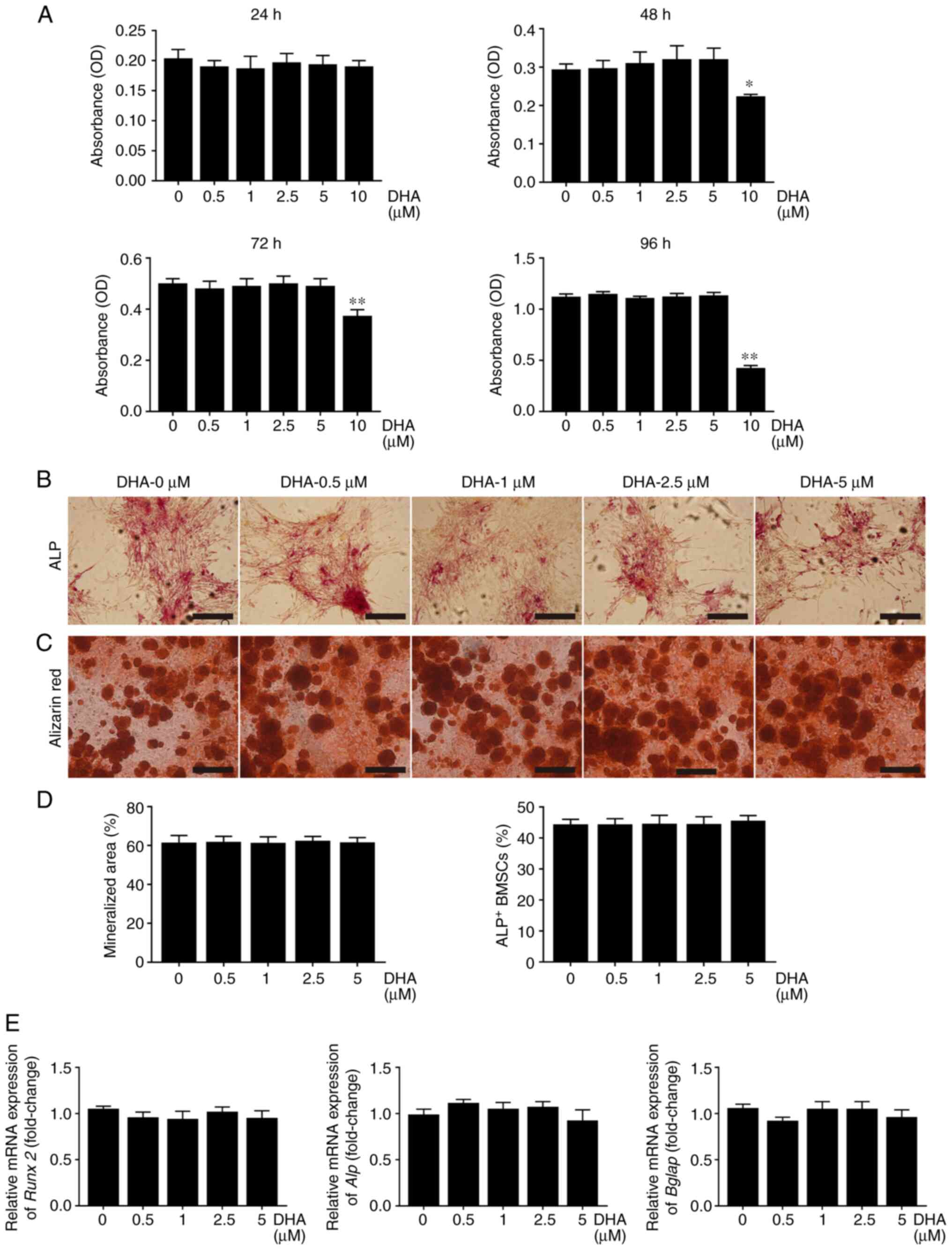

DHA do not affect proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in vitro

BMSCs have the ability to differentiate into osteoblasts, which are the major source of RANKL, affecting osteoclast formation (40). Therefore, further experiments were designed to investigate whether DHA affected the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. Similar to the experiments performed on BMMs, no cytotoxicity was observed with BMSCs at concentrations of DHA up to 5 µM (Fig. 4A). Given that the expression of ALP is a representative phenotypic indicator of the early osteogenic differentiation stage of BMSCs (41), an ALP staining kit was used to evaluate the effect of DHA on ALP activity of BMSCs cultured with osteogenic medium. The results obtained showed that treatment with different concentrations of DHA for 7 days did not change ALP activity (Fig. 4B and D). To evaluate the effect of DHA on calcium mineralization, BMSCs cultured with osteogenic medium for 21 days were stained with alizarin red. As shown in Fig. 4C, DHA did not affect the formation of mineralization nodules in BMSCs cultured with osteogenic medium. Furthermore, RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that DHA had no effect on the expression of osteoblast marker genes, including Runx family transcription factor 2 (Runx2), Alp and bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein (Bglap) (Fig. 4E). These results suggested that DHA did not affect the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

|

Figure 4

DHA does not affect proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in vitro. (A) BMSCs were cultured in α-MEM containing various concentrations of DHA for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, and cell viability as determined from the OD values, was assessed using Cell Counting Kit-8 assays. BMSCs were cultured in α-MEM containing osteogenic medium and various concentrations of DHA for 7 and 21 days prior to staining with (B) ALP and (C) alizarin red, respectively. Scale bar, 200 µm. (D) Quantitative analysis of the numbers of ALP-positive BMSCs from (B) and mineralization nodules from (C). (E) BMSCs were cultured in α-MEM containing osteogenic medium and various concentrations of DHA for 14 days, and subsequently genes (Runx 2, Alp and Bglap) associated with osteogenic differentiation were detected using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. n=3 per group. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. 0 µM control group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; BMSCs, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells; α-MEM, α modified Eagle's medium; OD, optical density; Runx 2, runx family transcription factor 2; Alp, alkaline phosphatase; Bglap, bone γ-carboxyglutamate protein.

|

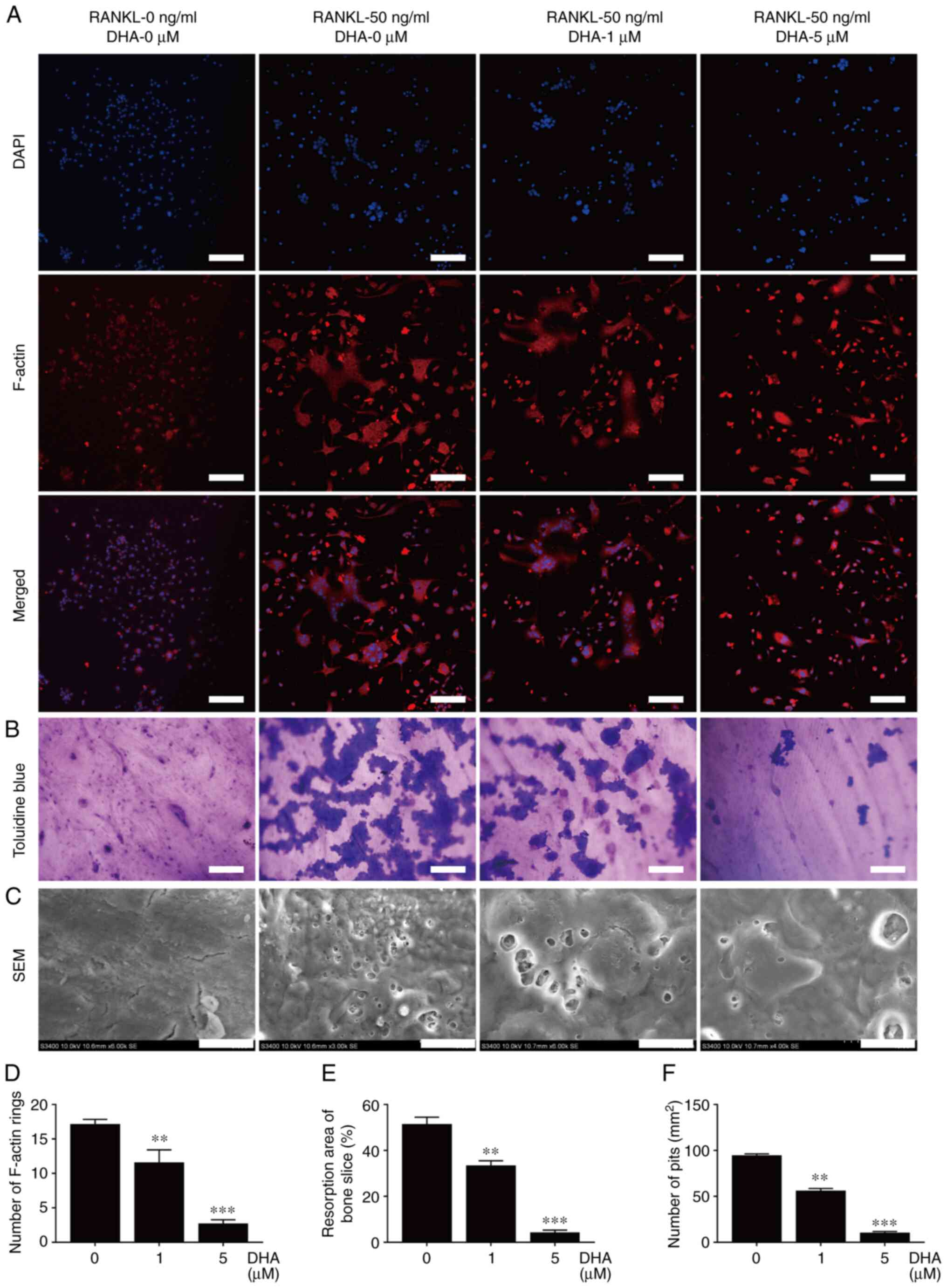

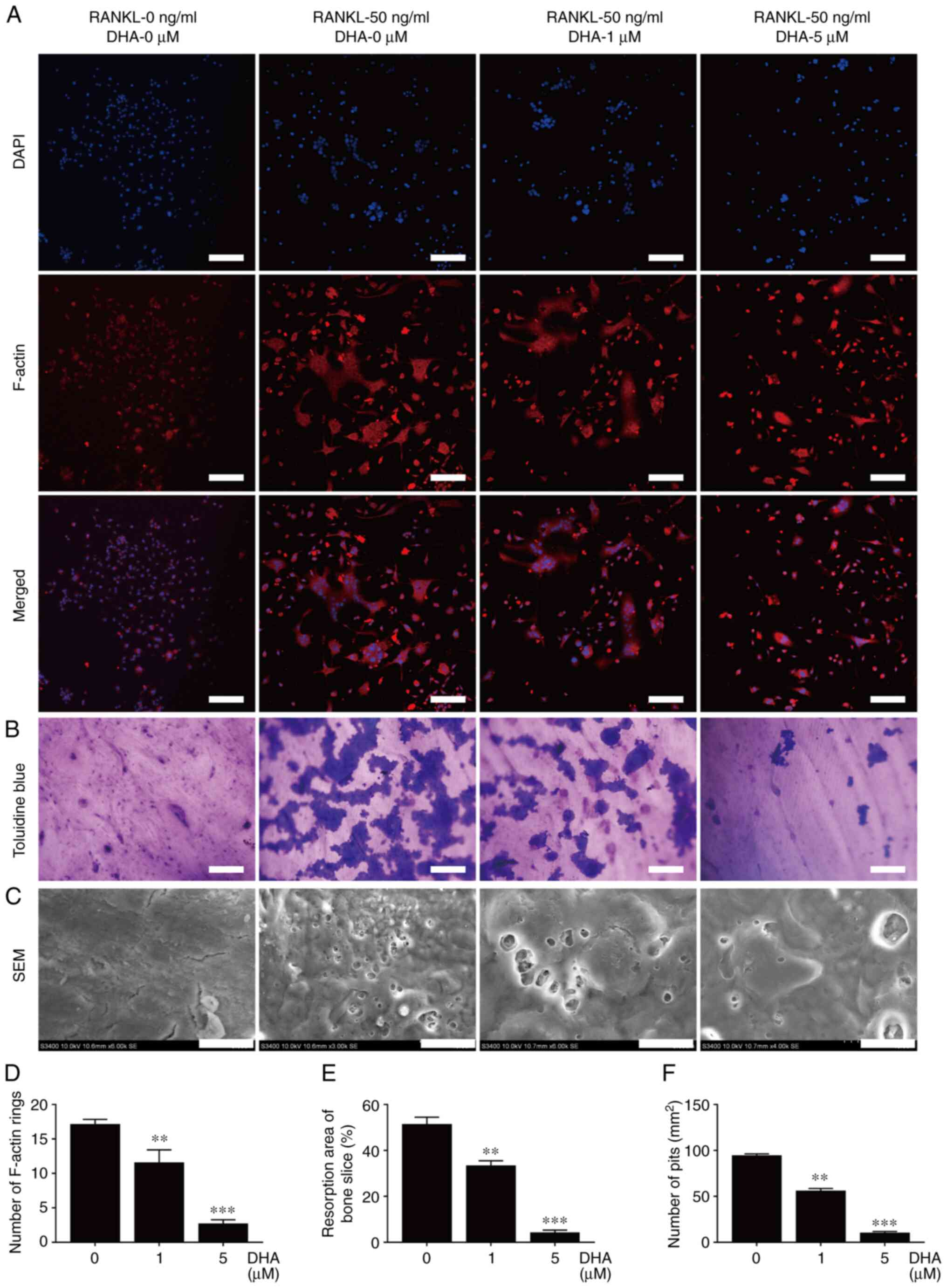

DHA inhibits F-actin ring formation and bone resorption of osteoclasts in vitro

Given that the formation of F-actin rings is necessary for osteoclastic bone resorption (29), the effect of DHA on F-actin rings was further investigated. F-actin rings with a typical appearance, stained with TRITC-conjugated phalloidin were observed in the group treated without DHA. However, treatment with different concentrations of DHA resulted in marked alterations in the number and morphology of F-actin rings (Fig. 5A). The number of F-actin rings per view was 17.13 in the group treated without DHA, 11.58 in the group treated with 1 µM DHA and 1.33 in the group treated with 5 µM DHA (Fig. 5D). These results suggested that DHA inhibited F-actin ring formation in osteoclasts in vitro.

|

Figure 5

DHA inhibits F-actin ring formation and bone resorption of osteoclast in vitro. (A) BMMs were stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL and various concentrations of DHA for 6 days, before being stained with tetraethyl rhodamine isothiocyanate-conjugated phalloidin and DAPI to indicate the F-actin rings and nucleus. Scale bar, 200 µm. (B) BMMs were seeded on bone slices and stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF, 50 ng/ml RANKL and various concentrations of DHA for 8 days, and subsequently bone resorption areas stained with toluidine blue were examined. Scale bar, 200 µm. (C) Bone resorption pits were shown by SEM. Scale bar, 20 µm. Quantitative analysis of (D) F-actin rings, (E) resorption areas and (F) resorption pits is also shown. n=3 per group. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µM control group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; BMMs, bone marrow-derived macrophages; M-CSF, macrophage-colony stimulating factor; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; SEM, scanning electron microscope.

|

As bone resorption is associated with the formation of osteoclasts and F-actin rings (29), the effects of DHA on osteoclast bone resorption using bone slices were investigated next. As shown in Fig. 5B and C, large areas were stained with toluidine blue and a number of large bone resorption pits were observed on the bone slices in the group treated without DHA; by contrast, smaller areas stained with toluidine blue and fewer bone resorption pits were observed on the bone slices in the groups treated with DHA. The resorption areas decreased from 51.38 to 33.36% and values <5% after treatment with 1 and 5 µM DHA, respectively (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, the number of resorption pits/mm2 was reduced from 94.39 to 10.3 after treatment with 5 µM DHA (Fig. 5F). Taken together, these results suggested that DHA suppressed osteoclast bone resorption in vitro.

DHA inhibits RANKL-induced NFATc1, NF-κB and MAPK activation in osteoclastogenesis

In order to further unravel the mechanism involved in the inhibition of DHA on osteoclast formation and bone resorption, RAW264.7 cells stably transfected with NFATc1 and NF-κB luciferase reporter constructs were used to investigate the activities of the two transcription factors. The data revealed that various concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2.5 and 5 µM) of DHA significantly inhibited NFATc1 and NF-κB luciferase activities in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6A and B).

|

Figure 6

DHA inhibits RANKL-induced NFATc1, NF-κB and MAPK activation in osteoclastogenesis. RAW264.7 cells transfected with NFATc1 and NF-κB were pretreated with various concentrations of DHA for 1 h, and subsequently incubated with α-MEM containing 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL for 6 h to activate NF-κB, and 24 h to activate NFATc1. Luciferase activities of (A) NFATc1 and (B) NF-κB were quantitatively analyzed. BMMs were pretreated with or without DHA (5 µM) for 4 h, and then stimulated with 30 ng/ml M-CSF and 50 ng/ml RANKL for the indicated time periods (0, 10, 30 and 60 min, and 0, 1, 3 and 5 days), before the cell lysates were quantitatively analyzed using western blotting for the (C and D) NFATc1, (E and F) NF-κB and (G and H) MAPK signaling pathways. n=3 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. 0 µM control group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T cell cytoplasmic 1; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; α-MEM, α modified Eagle's medium; M-CSF, macrophage-colony stimulating factor; BMMs, bone marrow derived macrophages; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase; p-, phosphorylated.

|

The two important transcription factors, NFATc1 and NF-κB, and the protein kinases associated with the MAPK signaling pathway (such as ERK, JNK and p38) fulfill important roles in osteoclast formation. Consequently, western blot analysis was performed to examine the protein levels of NFATc1, IκBα, NF-κB, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-JNK, JNK, p-p38 and p38 in BMMs pretreated with or without 5 µM DHA for 4 h, followed by treatment with 50 ng/ml RANKL for the indicated time periods. As shown by western blot analysis, NFATc1 was significantly reduced upon treatment with 5 µM DHA from 3 to 5 days post-stimulation of RANKL (Fig. 6C and D). Administration of 5 µM DHA significantly inhibited IκBα degradation and NF-κB activation at 30 min post-stimulation of RANKL (Fig. 6E and F). The inhibitory effect of DHA on p-p38 and p-JNK was observed at 30 min post-stimulation of RANKL, whereas its inhibitory effect on p-ERK1/2 was observed at 60 min post-stimulation of RANKL (Fig. 6G and H). Taken together, these results suggested that DHA could suppress RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through inhibiting the NFATc1, NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways.

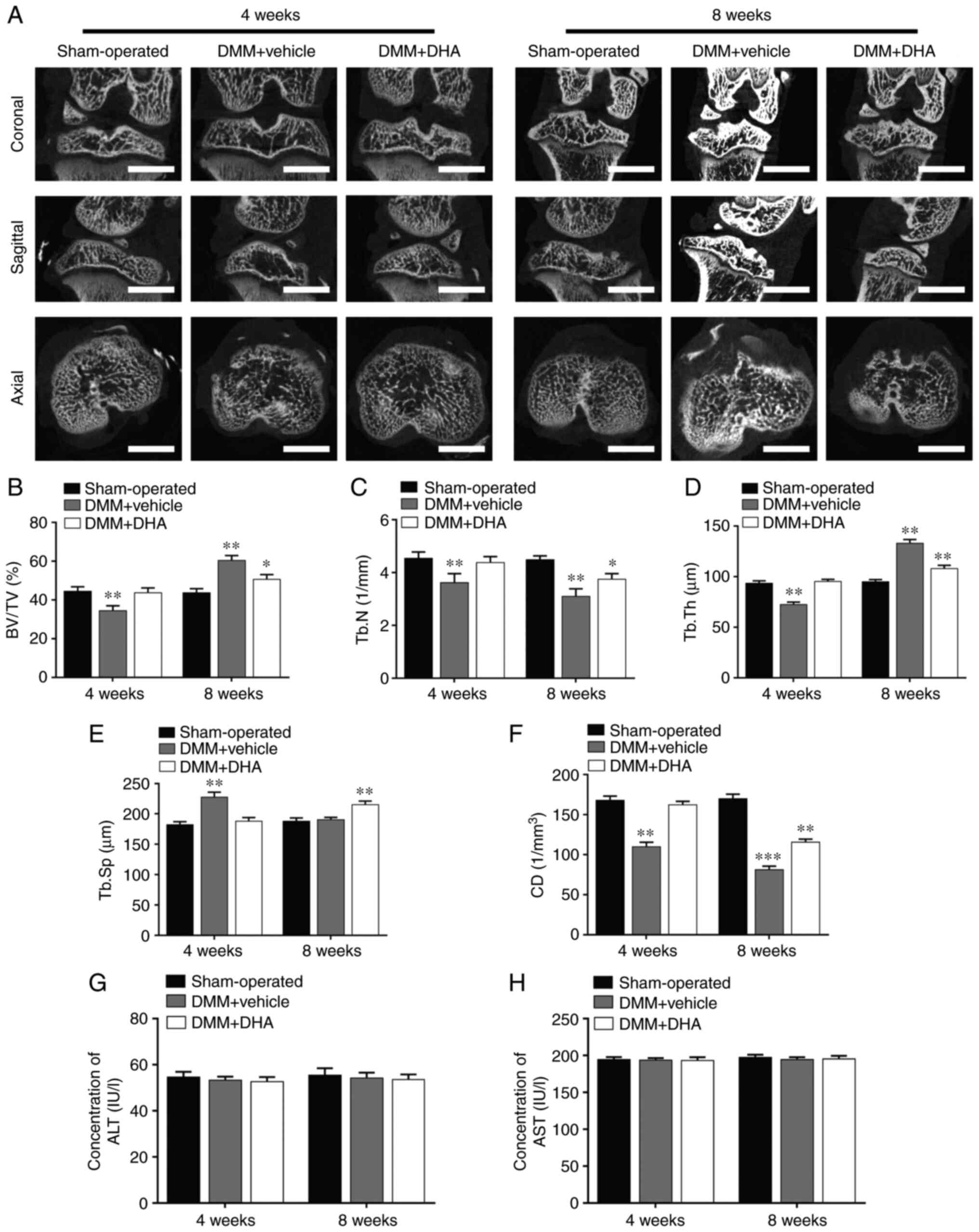

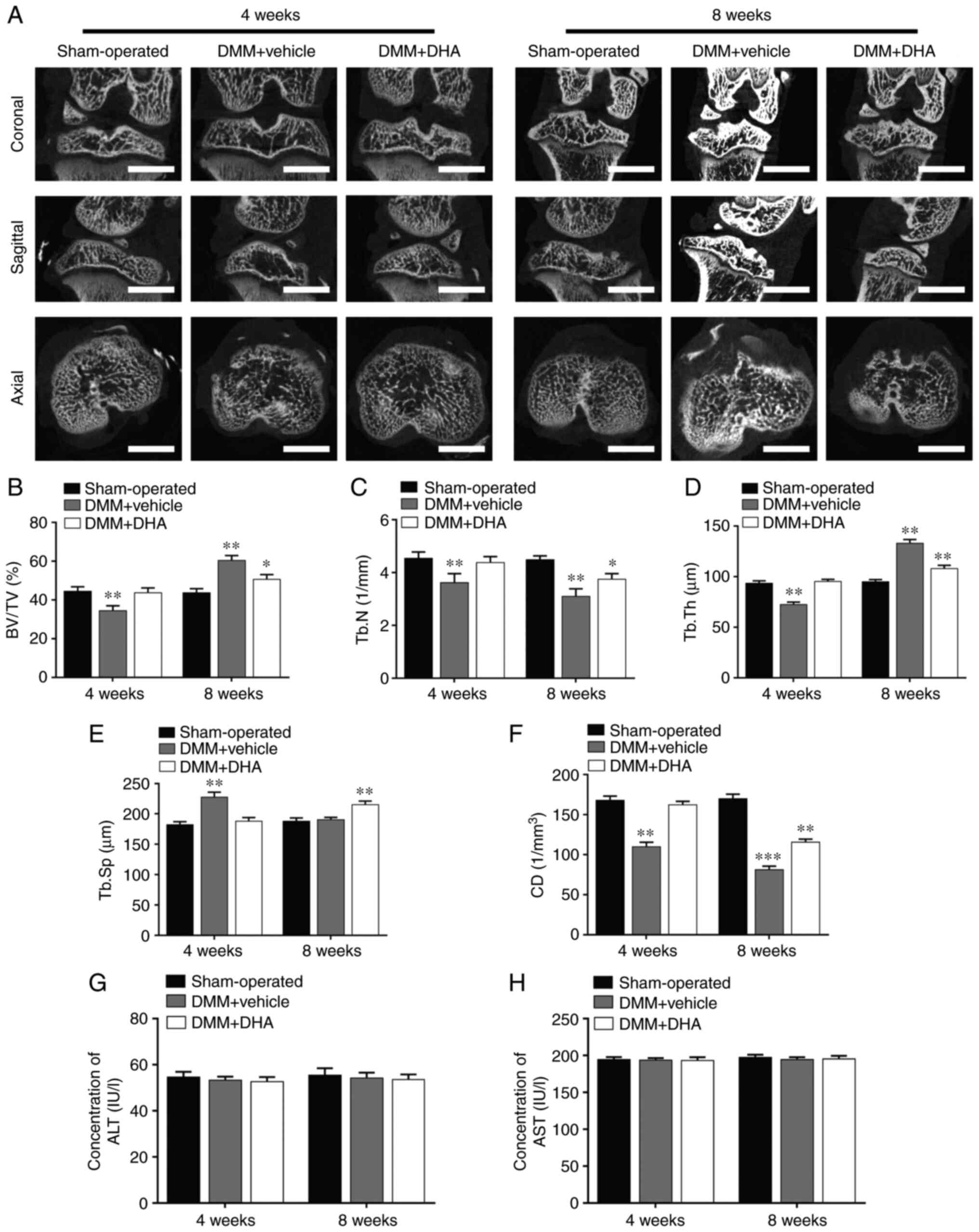

DHA inhibits bone loss in the early stage of DMM-induced OA in rats

The DMM-induced OA rats were treated with or without DHA for 4 and 8 weeks and, subsequently, the microstructure of the tibial subchondral bone was examined by µCT (Fig. 7A). The resultant microstructure indices demonstrated that a significant bone loss occurred in the DMM + vehicle group compared with the sham-operated group in terms of decreased BV/TV (Fig. 7B), Tb.N (Fig. 7C) and CD (Fig. 7F), reduced Tb.Th (Fig. 7D) and increased Tb.Sp (Fig. 7E) values at 4 weeks after the surgery. However, the overall trends in these changes in the DMM + DHA group were preserved by an intraperitoneal injection of DHA at 1 mg/kg every 2 days for 4 and 8 weeks, and the levels of the ALT (Fig. 7G) and AST (Fig. 7H) biomarkers indicated that DHA was not toxic to rats.

|

Figure 7

DHA inhibits bone loss during the early stage of DMM-induced OA in a rat model. (A) The DMM-induced OA rats were treated with or without DHA for 4 and 8 weeks, and subsequently the microarchitecture in tibial subchondral bone was examined by µCT. Scale bar, 2,000 µm. Quantitative µCT analyses of microarchitecture in tibial subchondral bone are shown, as follows: (B) BV/TV (%), (C) Tb.N, (D) Tb.Th, (E) Tb.Sp and (F) CD. Quantitative analyses of the serum biomarkers are shown, as follows: (G) ALT and (H) AST. n=6 per group/time point. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. sham-operated group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; DMM, destabilization of medial meniscus; OA, osteoarthritis; µCT, micro-CT; BV/TV, bone volume/total volume; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular separation; CD, connectivity density; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase.

|

DHA inhibits osteoclastogenesis in the early stage of DMM-induced OA in rats

According to the results of TRAP staining on tibial subchondral bone, it was found that the number of TRAP-positive osteoclasts was higher in the DMM + vehicle group compared with that in the sham-operated group, whereas DHA significantly inhibited osteoclast formation at 4 weeks post-surgery (Fig. 8A and D). These results corroborated the experiments wherein subchondral bone resorption was detected by µCT, supporting the hypothesis that DMM causes subchondral bone loss by enhancing bone resorption mediated by promoting osteoclast formation during the early stage of OA.

|

Figure 8

DHA suppresses cartilage degeneration by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis in the early stage of DMM-induced OA rats. The DMM-induced OA rats were treated with or without DHA for 4 and 8 weeks, and histological analysis of osteoclasts in the subchondral bone and cartilage was performed with (A) TRAP, (B) H&E and (C) Safranin O-Fast Green staining. Scale bar, 200 µm. Quantitative analysis of (D) Oc.S/BS, (E) CC/TAC and (F) OARSI scores (n=6 per group/time point). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. sham-operated group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; DMM, destabilization of the medial meniscus; OA, osteoarthritis; TRAP, tartrate resistant acid phosphatase; Oc.S, osteoclast surface; BS, bone surface; CC, calcified cartilage; TAC, total articular cartilage; OARSI, Osteoarthritis Research Society International.

|

DHA suppresses articular cartilage degeneration in DMM-induced OA in rats

H&E and Safranin O-Fast Green staining was subsequently used to assess histomorphological changes in the cartilage during OA progression. It was found that cartilage degeneration generally occurred, and become more severe in a time-dependent manner, after OA induction. H&E staining revealed that the thickness of HC decreased, whereas that of CC increased and moved closer to the articular surface in the DMM + vehicle group compared with the sham-operated group (Fig. 8B). Treatment with DHA, however, significantly attenuated the increasing thickness of CC and the CC/total articular cartilage (TAC) ratio (Fig. 8E).

Safranin O-Fast Green staining showed that, compared with the sham-operated group, the matrix and chondrocytes in the DMM + vehicle group were lost, and irregular cracks had developed at 4 weeks post-surgery; in addition, full-thickness degeneration of articular cartilage occurred and became more widespread by 8 weeks, with the development of OA (Fig. 8C). However, DHA significantly alleviated the cartilage degeneration grade and delayed the onset of OA. The OARSI score results demonstrated that, compared with the sham-operated group, a markedly increased rate of cartilage degeneration occurred in the DMM + vehicle group, whereas cartilage degeneration was suppressed in the DMM + DHA group (Fig. 8F).

DHA attenuates expression of RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATc1 in the early stage of DMM-induced OA in rats

RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATC1 are proteins that are known to affect the formation and migration of osteoclasts (16,42), and immunohistochemical staining was performed to assess the effect of DHA on these proteins. The results revealed that significantly more cells in the DMM + vehicle group were stained positively for RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATc1 (Fig. 9A-D) compared with the sham-operated group; however, DHA suppressed the increased expression levels of RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATc1 induced by DMM (Fig. 9A-D). These findings further corroborated the inhibitory effect of DHA on osteoclast formation and function.

|

Figure 9

DHA attenuates the expression levels of RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATc1 during the early stage of DMM-induced OA in a rat model. The DMM-induced OA rats were treated with or without DHA for 4 weeks, and the expression levels of (A) RANKL, (B) CXCL12 and (C) NFATc1 were revealed by immunohistochemistry staining. Scale bar, 200 µm. (D) Quantitative analysis of RANKL, CXCL12 and NFATc1 (n=6 per group/time point). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 vs. sham-operated group. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; CXCL12, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T cell cytoplasmic 1; DMM, destabilization of the medial meniscus; OA, osteoarthritis.

|

Discussion

OA is an inflammatory disease characterized by chronic, progressive degeneration of the joints. Bone remodeling in subchondral bone has a significant role in the occurrence and development of OA (4). In the early stage of OA, prior to the degeneration of articular cartilage, bone resorption and loss mediated by osteoclasts in subchondral bone are enhanced, and inflammatory factors, including TGF-β, prostaglandin E2 and CXCL12, in the microenvironment are increased, which leads to the activation of the signaling pathways associated with osteogenesis, resulting in osteosclerosis in the late stage of OA (37). Based on the spatio-temporal order of OA, several studies have demonstrated that drugs which inhibit osteoclasts, such as bisphosphonates (as represented by zoledronic acid), elicit positive effects in the treatment of OA (9,43). However, these drugs also generate a number of adverse reactions, such as osteonecrosis of the jaw and gastrointestinal reactions (44). Therefore, it is necessary to identify drugs to treat OA that have less severe adverse effects.

Previously, DHA was reported to inhibit estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis (26), to enhance doxorubicin-induced breast cancer cell apoptosis (45) and to restrain breast cancer-induced osteolysis in vivo (24). However, it remains unclear whether DHA is able to prevent DMM-induced OA in rats. Therefore, the present study was designed to observe the effects of DHA on DMM-induced OA rats in vivo, and to investigate the underlying mechanism of DHA on osteoclast formation and function in vitro. Of note, DHA was able to suppress osteoclast formation and alleviate DMM-induced OA in vivo. On the one hand, the suppressive effects were due to the inhibitory effects of DHA on osteoclast formation and function, which was associated with subchondral bone remodeling. On the other hand, it may also be due to the fact that DHA can delay the procession of OA, consequently inhibiting the degeneration of articular cartilage.

The main physiological functions of osteoclasts in vivo are to absorb bone matrix and minerals, to participate in the bone remodeling cycle and to maintain the integrity of the skeleton (46). Mature osteoclasts with bone resorption function are multinucleated cells derived from hematopoietic stem cells or the monocyte-macrophage lineage that arise from the fusion of mononuclear precursor cells in the presence of specific cytokines, including M-CSF and RANKL (11). In the present study, the results obtained indicated that BMMs differentiate into osteoclasts in a time-dependent manner in the presence of RANKL and M-CSF, whereas DHA inhibited RANKL-induced osteoclast formation in a dose-dependent manner without any cytotoxicity. In addition, DHA did not affect the osteogenic differentiation and proliferation of BMSCs at concentrations <10 µM. Taken together, these results suggested that DHA is an attractive candidate drug for osteolytic bone diseases, including OA.

With the formation of mature osteoclasts, bone minerals represented by hydroxyapatite are dissolved by acids secreted from osteoclasts, and the organic matrix is degraded by certain specific proteolytic enzymes, including CTSK, TRAP, CTR and MMP-9 (47). In addition, the numbers of certain receptors located on the surface of osteoclast precursor cells that, are associated with cell migration and differentiation, such as CXCR4 and RANK, are increased during osteoclast formation (48,49). Consistent with previous reports, the present study revealed that, during osteoclastogenesis, the expression levels of certain osteoclast-associated genes, such as CTSK, CTR, TRAP, MMP-9, RANK and CXCR4, were upregulated. However, DHA reversed this trend of upregulation, which further confirmed our hypothesis that DHA inhibits the bone resorption of osteoclasts.

Osteoclasts are required to polarize prior to performing their role in bone resorption. During this process, the F-actin cytoskeleton is organized to form a 'ring-like' structure for sealing the area beneath and forming a closed compartment, in which the resorption pits are generated through resorbing the bone matrix and minerals (29). Therefore, the formation of pits is regarded as a typical hallmark of osteoclast activity and, in the present study, bone slices were used as a mineral substrate of seeded osteoclasts to detect their resorption ability in vitro. The results obtained demonstrated that RANKL-induced BMMs generated more F-actin rings and had a stronger bone resorption capability, although these features could be suppressed by DHA. However, the underlying mechanism that accounts for the inhibition of osteoclast formation and resorption mediated by DHA remains unclear.

To explore the potential mechanism underlying how DHA affects osteoclast formation and function, the effects of DHA on critical signaling pathways associated with osteoclast formation were investigated. During osteoclastogenesis, the differentiation and migration of osteoclast precursors has been shown to be associated with the NF-κB signaling pathway (50), which may be activated by the binding of RANKL to its receptor, RANK (42). The RANKL/RANK/TRAF6 signaling pathway may lead to the activation of IκB kinase (IKK), which subsequently causes IκBα to become phosphorylated and degraded. NF-κB is then released, and is translocated to the nucleus, where it causes upregulation of the expression of NFATc1, which has been confirmed as an important transcription factor that regulates osteoclast formation and function through initiating the transcription of certain downstream targets associated with osteoclastogenesis (51,52).

Compared with the primary BMMs, RAW264.7 cell lineage is prevailing in the luciferase assay for transcription factors because it merits advantages for providing a much easier accessible osteoclastic cellular model, which ensures the stability and accuracy of experimental results (30,31). However, results from BMMs may be influenced by factors such as operation and source. Therefore, the RAW264.7 cell lineage was chosen to perform the luciferase assay instead of BMMs. The results obtained in the present study through detecting the protein levels and luciferase activities of NF-κB and NFATc1 during RANKL-induced osteoclast formation were in agreement with the previously published reports. In addition, the present study also demonstrated that DHA was able to inhibit the RANKL-induced degradation of IκBα, and the upregulation of NF-κB and NFATc1. Collectively, these results suggested that DHA may suppress RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through inhibiting the NF-κB and NFATc1 signaling pathways.

The MAPK signaling pathway is another pathway downstream of RANKL/RANK/TRAF6 signaling (53). The binding of RANKL to RANK results in the phosphorylation of MAPKs, including ERK, JNK and p38, and previous studies have confirmed that the phosphorylation levels of ERK, JNK and p38 are associated with osteoclast formation (14,54). In the present study, the western blotting results demonstrated that DHA attenuated the RANKL-induced phosphorylation of ERK, JNK and p38. These findings, however, stand in contrast with previous findings reported by Feng et al (24), whose results demonstrated that DHA exerted no suppressive effect on the phosphorylation levels of proteins associated with the MAPK pathway. The reason for this discrepancy may be due to the following two factors: First, Feng et al (24) measured the phosphorylation levels of ERK, JNK and p38 at 10 and 30 min post-stimulation of RANKL, whereas the present experiments revealed that DHA exerted a marked inhibitory effect at 60 min post-stimulation of RANKL. Second, different types of cells were utilized for osteoclastogenesis in the two sets of experiments, RAW264.7 murine macrophages were used in the study by Feng et al (24), whereas BMMs were used in the present study. Therefore, further studies are required to confirm the biological efficacy of DHA, and selective inhibitors of NF-κB, NFATc1 and MAPKs should also be administered to investigate the expression of associated targets, so as to further verify the results reported in the current work. Based on the afore-mentioned analysis, it may be speculated that the inhibition or downregulation of the MAPK signaling pathway by DHA may also result in decreased expression of downstream targets required for osteoclast formation and function. Taken together, it is possible to surmise that NF-κB, NFATc1 and MAPKs are likely to be the crucial downstream signaling pathways that mediate the inhibitory effects of DHA on osteoclast formation and function.

In the present study, the DMM-induced OA experiment was designed in rats for the following reasons: i) The DMM method can successfully induce OA in rats; and ii) compared with the anterior cruciate ligament resection method, the DMM method is minimally invasive, and does not generate interference due to trauma, or acute inflammatory or immune responses, and thus, better simulates chronic, progressive and degenerative OA, which is more useful in observing the pathological changes during the early stage of OA (33). Therefore, the DMM method was selected to establish the OA model to investigate the effect of DHA on OA. The findings obtained revealed that the DMM method successfully induced OA in the rats, as shown by the increased OARSI score and the CC:TAC ratio, and abnormal subchondral bone remodeling was characterized by a turnover from enhanced bone resorption in early OA to enhanced bone formation in advanced OA, which was consistent with the changes observed in the number of osteoclasts in subchondral bone. Furthermore, the expression levels of biomolecules associated with osteoclastogenesis, including RANKL, NFATc1 and CXCL12, were increased. However, DHA was effectively able to reduce the increases recorded in the OARSI score and the CC:TAC ratio, to suppress the enhanced resorption and levels of biomolecules associated with osteoclastogenesis, to reduce cartilage degeneration and to delay OA progression. These results confirmed that there is crosstalk between the processes that coordinate abnormal subchondral bone remodeling and articular cartilage degeneration.

Under physiological conditions, articular cartilage and the lower subchondral bone form a structural and functional unit that participates in transmitting signals of pressure, tension and shear during joint movement (55). Both the degeneration of articular cartilage and changes in the microstructure of subchondral bone are pathological characteristics of OA. An increasing body of evidence has shown that there are material and information exchanges between articular cartilage and subchondral bone in the form of crosstalk. During OA progression, an increased porosity occurs in the subchondral plate, which used to be considered as a barrier between articular cartilage and subchondral bone (56). In addition, highly increased numbers of vessels and nerves generated in the subchondral bone penetrate into calcified cartilage and connect with the bone marrow microenvironment, thereby providing a material basis for the crosstalk between the two different structures. Moreover, bone marrow acts as a complex micro-environment in which there are multiple forms of crosstalk, depending on the microenvironment among different types of cells (57,58). Therefore, the findings of the present study led us to speculate that, in early OA, DMM treatment results in a sequence of changes that affect both the mechanical and the chemical environment, and certain biomolecules derived from other cells associated with osteoclastogenesis, including RANKL and CXCL12, are released into the bone marrow microenvironment, resulting in an increased rate of osteoclast formation, enhanced subchondral bone resorption and further destruction of the microstructure, which contributes to the degeneration of articular cartilage. However, the mechanism that accounts for how osteoclast formation and function are affected by other cells remains poorly understood, and further studies are required to precisely delineate the mechanism(s) involved.

The present study does, however, have certain limitations. The fusion and migration of osteoclast precursors are necessary actions for the formation of functional multinucleated osteoclasts, which are regulated by certain cytokines, including E-cadherin, dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein, macrophage fusion receptor, CD44 and CXCR4 (59). In the present study, the effects and underlying mechanism of DHA were mainly investigated only regarding osteoclast formation and function, whereas the effects and mechanism of DHA in terms of the fusion and migration of osteoclast precursors should be investigated in the future. Additionally, due to the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of DHA (22,23), the direct effects of DHA on articular cartilage need to be further explored.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated how DHA can improve the imbalance of subchondral bone remodeling by inhibiting osteoclast formation and bone resorption in early OA, thereby delaying OA progression and alleviating cartilage degeneration. In addition, the mechanism through which DHA inhibits osteoclast formation and function in early OA has been shown to be associated with the NF-κB, MAPK and NFATc1 signaling pathways (Fig. 10), which may be candidates as therapeutic targets for the precise treatment of OA.

|

Figure 10

Schematic representation of DHA inhibiting RANKL-induced osteoclast formation. RANKL binds to RANK and recruits TRAF6 to activate the NF-κB and MAPK pathways. The signal is then transmitted to NFATc1 and c-Fos. Sequentially stimulated NFATc1 translocates into the nucleus, where it initiates the expression of osteoclast marker genes, including CTSK, CTR, TRAP, MMP-9, RANK and CXCR4. DHA, dihydroartemisinin; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB; TRAF6, tumor necrosis factor-associated factor 6; NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; NFATc1, nuclear factor of activated T cell cytoplasmic 1; CTSK, cathepsin k; CTR, calcitonin receptor; TRAP, tartrate resistant acid phosphatase; MMP-9, matrix metallopeptidase 9; RANK, receptor activator of nuclear factor κB; CXCR4, C-X-C motif chemokine receptor 4; BMMs, bone marrow derived macrophages; OA, osteoarthritis; ERK, extracellular regulated protein kinases; JNK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase.

|

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

QJ designed the experiment. DD, JY, GF, YZ and LM conducted the main experiments. DD analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript and revised it. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. QJ and DD confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Animal Care and Experiment Committee of Ningxia Medical University (Yinchuan, China; approval no. IACUC-NYLAC-2020-51).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The experiments for this study were performed in the Key Laboratory of Fertility Preservation and Maintenance of Ministry of Education (Yinchuan, China), so the authors gratefully acknowledge this laboratory for providing the experimental site and equipment.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81660373).

References

|

1

|

Driban JB, Harkey MS, Barbe MF, Ward RJ, MacKay JW, Davis JE, Lu B, Price LL, Eaton CB, Lo GH and McAlindon TE: Risk factors and the natural history of accelerated knee osteoarthritis: A narrative review. Bmc Musculoskel Dis. 21:3322020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators: Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 392:1789–1858. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bruyère O, Cooper C, Arden N, Branco J, Brandi ML, Herrero-Beaumont G, Berenbaum F, Dennison E, Devogelaer JP, Hochberg M, et al: Can we identify patients with high risk of osteoarthritis progression who will respond to treatment? A focus on epidemiology and phenotype of osteoarthritis. Drug Aging. 32:179–187. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Goldring SR and Goldring MB: Changes in the osteochondral unit during osteoarthritis: Tructure, function and cartilage-bone crosstalk. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 12:632–644. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Zhu X, Chan YT, Yung PSH, Tuan RS and Jiang Y: Subchondral bone remodeling: A therapeutic target for osteoarthritis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:6077642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Li G, Ma Y, Cheng TS, Landao-Bassonga E, Qin A, Pavlos NJ, Zhang C, Zheng Q and Zheng MH: Identical subchondral bone microarchitecture pattern with increased bone resorption in rheumatoid arthritis as compared to osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 22:2083–2092. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lin C, Liu L, Zeng C, Cui ZK, Chen Y, Lai P, Wang H, Shao Y, Zhang H, Zhang R, et al: Activation of mTORC1 in subchondral bone preosteoblasts promotes osteoarthritis by stimulating bone sclerosis and secretion of CXCL12. Bone Res. 7:52019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Cui Z, Xu C, Li X, Song J and Yu B: Treatment with recombinant lubricin attenuates osteoarthritis by positive feedback loop between articular cartilage and subchondral bone in ovariectomized rats. Bone. 74:37–47. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Khorasani MS, Diko S, Hsia AW, Anderson MJ, Genetos DC, Haudenschild DR and Christiansen BA: Effect of alendronate on post-traumatic osteoarthritis induced by anterior cruciate ligament rupture in mice. Arthritis Res Ther. 17:302015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Pereira M, Petretto E, Gordon S, Bassett J, Williams GR and Behmoaras J: Common signalling pathways in macrophage and osteoclast multinucleation. J Cell Sci. 131:jcs2162672018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL, Kelley MJ, Dunstan CR, Burgess T, Elliott R, Colombero A, Elliott G, Scully S, et al: Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell. 93:165–176. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kong YY, Yoshida H, Sarosi I, Tan HL, Timms E, Capparelli C, Morony S, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Van G, Itie A, et al: OPGL is a key regulator of osteoclastogenesis, lymphocyte development and lymph-node organogenesis. Nature. 397:315–323. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N, Yamaguchi K, Kinosaki M, Mochizuki S, Tomoyasu A, Yano K, Goto M, Murakami A, et al: Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:3597–3602. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yang X, Liang J, Wang Z, Su Y, Zhou B, Wu Z, Li J, Li X, Chen R, Zhao J, et al: Sesamolin protects mice from ovariectomized bone loss by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and RANKL-mediated NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Front Pharmacol. 12:6646972021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zou W and Teitelbaum SL: Integrins, growth factors, and the osteoclast cytoskeleton. Ann Ny Acad Sci. 1192:27–31. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lian WS, Ko JY, Chen YS, Ke HJ, Hsieh CK, Kuo CW, Wang SY, Huang BW, Tseng JG and Wang FS: MicroRNA-29a represses osteoclast formation and protects against osteoporosis by regulating PCAF-mediated RANKL and CXCL12. Cell Death Dis. 10:7052019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang X, Yamauchi K and Mitsunaga T: A review on osteoclast diseases and osteoclastogenesis inhibitors recently developed from natural resources. Fitoterapia. 142:1044822020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tu Y: The development of new antimalarial drugs: Qinghaosu and dihydro-qinghaosu. Chin Med J (Engl). 112:976–977. 1999.

|

|

19

|

Wartenberg M, Wolf S, Budde P, Grünheck F, Acker H, Hescheler J, Wartenberg G and Sauer H: The antimalaria agent artemisinin exerts antiangiogenic effects in mouse embryonic stem cell-derived embryoid bodies. Lab Invest. 83:1647–1655. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Hwang YP, Yun HJ, Kim HG, Han EH, Lee GW and Jeong HG: Suppression of PMA-induced tumor cell invasion by dihydroartemisinin via inhibition of PKCalpha/Raf/MAPKs and NF-kappaB/AP-1-dependent mechanisms. Biochem Pharmacol. 79:1714–1726. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lu JJ, Meng LH, Cai YJ, Chen Q, Tong LJ, Lin LP and Ding J: Dihydroartemisinin induces apoptosis in HL-60 leukemia cells dependent of iron and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation but independent of reactive oxygen species. Cancer Biol Ther. 7:1017–1023. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Xu H, He Y, Yang X, Liang L, Zhan Z, Ye Y, Yang X, Lian F and Sun L: Anti-malarial agent artesunate inhibits TNF-alpha-induced production of proinflammatory cytokines via inhibition of NF-kappaB and PI3 kinase/Akt signal pathway in human rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 46:920–926. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Dong YJ, Li WD and Tu YY: Effect of dihydro-qinghaosu on auto-antibody production, TNF alpha secretion and pathologic change of lupus nephritis in BXSB mice. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 23:676–679. 2003.In Chinese. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Feng MX, Hong JX, Wang Q, Fan YY, Yuan CT, Lei XH, Zhu M, Qin A, Chen HX and Hong D: Dihydroartemisinin prevents breast cancer-induced osteolysis via inhibiting both breast caner cells and osteoclasts. Sci Rep. 6:190742016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li WD, Dong YJ, Tu YY and Lin ZB: Dihydroarteannuin ameliorates lupus symptom of BXSB mice by inhibiting production of TNF-alpha and blocking the signaling pathway NF-kappa B translocation. Int Immunopharmacol. 6:1243–1250. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhou L, Liu Q, Yang M, Wang T, Yao J, Cheng J, Yuan J, Lin X, Zhao J, Tickner J and Xu J: Dihydroartemisinin, an anti-malaria drug, suppresses estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis, osteoclast formation, and RANKL-induced signaling pathways. J Bone Miner Res. 31:964–974. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hu JP, Nishishita K, Sakai E, Yoshida H, Kato Y, Tsukuba T and Okamoto K: Berberine inhibits RANKL-induced osteoclast formation and survival through suppressing the NF-kappaB and Akt pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 580:70–79. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ryoo GH, Moon YJ, Choi S, Bae EJ, Ryu JH and Park BH: Tussilagone promotes osteoclast apoptosis and prevents estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 531:508–514. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Würger T, Roschger P, Zwettler E, Fratzl P, Rogers MJ, Klaushofer K and Rumpler M: Osteoclasts on bone and dentin in vitro: Mechanism of degradation and comparison of resorption behaviour. Bone. 51:S92012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Wang C, Steer JH, Joyce DA, Yip KH, Zheng MH and Xu J: 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) inhibits osteoclastogenesis by suppressing RANKL-induced NF-kappaB activation. J Bone Miner Res. 18:2159–2168. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kwak SC, Cheon YH, Lee CH, Jun HY, Yoon KH, Lee MS and Kim JY: Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract prevents bone loss via regulation of osteoclast differentiation, apoptosis, and proliferation. Nutrients. 12:31642020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Glasson SS, Blanchet TJ and Morris EA: The surgical destabilization of the medial meniscus (DMM) model of osteoarthritis in the 129/SvEv mouse. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 15:1061–1069. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Zhao YG, Wang Y, Guo Z, Gu AD, Dan HC, Baldwin AS, Hao W and Wan YY: Dihydroartemisinin ameliorates inflammatory disease by its reciprocal effects on Th and regulatory T cell function via modulating the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. J Immunol. 189:4417–4425. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals: Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition. National Academies Press (US); Washington, DC: 2011

|

|

36

|

Bei M, Tian F, Liu N, Zheng Z, Cao X, Zhang H, Wang Y, Xiao Y, Dai M and Zhang L: A novel rat model of patellofemoral osteoarthritis due to patella baja, or low-lying patella. Med Sci Monit. 25:2702–2717. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhen G, Wen C, Jia X, Li Y, Crane JL, Mears SC, Askin FB, Frassica FJ, Chang W, Yao J, et al: Inhibition of TGF-β signaling in mesenchymal stem cells of subchondral bone attenuates osteoarthritis. Nat Med. 19:704–712. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Moskowitz RW: Osteoarthritis cartilage histopathology: Grading and staging. Osteoarthr Cartilage. 14:1–2. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhu S, Zhu J, Zhen G, Hu Y, An S, Li Y, Zheng Q, Chen Z, Yang Y, Wan M, et al: Subchondral bone osteoclasts induce sensory innervation and osteoarthritis pain. J Clin Invest. 129:1076–1093. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

40

|

Simon D, Derer A, Andes FT, Lezuo P, Bozec A, Schett G, Herrmann M and Harre U: Galectin-3 as a novel regulator of osteoblast-osteoclast interaction and bone homeostasis. Bone. 105:35–41. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang J, Cai L, Tang L, Zhang X, Yang L, Zheng K, He A, Boccaccini AR, Wei J and Zhao J: Highly dispersed lithium doped mesoporous silica nanospheres regulating adhesion, proliferation, morphology, ALP activity and osteogenesis related gene expressions of BMSCs. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 170:563–571. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kang MR, Jo SA, Yoon YD, Park KH, Oh SJ, Yun J, Lee CW, Nam KH, Kim Y, Han SB, et al: Agelasine D suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via down-regulation of c-Fos, NFATc1 and NF-κB. Mar Drugs. 12:5643–5656. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cai G, Aitken D, Laslett LL, Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Hill C, March L, Wluka AE, Wang Y, Antony B, et al: Effect of intravenous zoledronic acid on tibiofemoral cartilage volume among patients with knee osteoarthritis with bone marrow lesions: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 323:1456–1466. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Nakamura T, Fukunaga M, Nakano T, Kishimoto H, Ito M, Hagino H, Sone T, Taguchi A, Tanaka S, Ohashi M, et al: Efficacy and safety of once-yearly zoledronic acid in Japanese patients with primary osteoporosis: Two-year results from a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study (ZOledroNate treatment in Efficacy to osteoporosis; ZONE study). Osteoporosis Int. 28:389–398. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wu GS, Lu JJ, Guo JJ, Huang MQ, Gan L, Chen XP and Wang YT: Synergistic anti-cancer activity of the combination of dihydroartemisinin and doxorubicin in breast cancer cells. Pharmacol Rep. 65:453–459. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Crockett JC, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Hocking LJ and Helfrich MH: Bone remodelling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 124:991–998. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

L Fvall H, Newbould H, Karsdal MA, Dziegiel MH, Richter J, Henriksen K and Thudium CS: Osteoclasts degrade bone and cartilage knee joint compartments through different resorption processes. Arthritis Res Ther. 20:672018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Luo T, Liu H, Feng W, Liu D, Du J, Sun J, Wang W, Han X, Guo J, Amizuka N, et al: Adipocytes enhance expression of osteoclast adhesion-related molecules through the CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling pathway. Cell Prolif. 50:e123172017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Tran MT, Okusha Y, Feng Y, Morimatsu M, Wei P, Sogawa C, Eguchi T, Kadowaki T, Sakai E, Okamura H, et al: The inhibitory role of Rab11b in osteoclastogenesis through triggering lysosome-induced degradation of c-Fms and RANK surface receptors. Int J Mol Sci. 21:93522020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

50

|

Kimachi K, Kajiya H, Nakayama S, Ikebe T and Okabe K: Zoledronic acid inhibits RANK expression and migration of osteoclast precursors during osteoclastogenesis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 383:297–308. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|