Introduction

Peripheral nerve injury causes a loss of sensory and

motor function, and has a significant impact on the quality of life

(1). In the United States alone,

>200,000 nerve repair treatments are performed each year

(2). For short lengths of nerve

damage, the conventional clinical procedure, end-to-end

anastomosis, is appropriate (3).

If the damaged nerve is too long to be repaired with tension-free

sutures, autologous transplantation can be used for nerve

reconstruction, which is considered the 'gold standard' of

contemporary nerve repair treatment (4). In recent decades, several

configurations of potential autografts for nerve conduits have been

investigated (5). Despite recent

advances in the understanding of nerve regeneration and surgical

techniques, complete functional repair of damaged nerves is rarely

achieved (6).

Pericytes, which promote vessel growth and maintain

the neurovascular unit, are thought to be progenitor cells and may

play a role in neurovascular regeneration (7). It has also been proposed that

peripheral nerve pericytes may stimulate axon regeneration and

barrier enhancement, preventing neuronal loss in the central

nervous system (8,9). Degeneration of pericytes has been

observed in diseases related to neurovascular dysfunction, such as

dementia and Alzheimer's disease (10). Our previous study showed that

pericytes enhanced neurovascular regeneration in a mouse model of

cavernous nerve injury (11).

Several researchers have demonstrated that

extracellular vesicles (EVs) incorporate proteins, lipids, and RNA,

which are involved in physiological and pathological communications

between cells (12,13). Previous studies have shown that

EVs from particular cell types and environments can affect tissue

regeneration (14,15). However, one of the most

significant disadvantages of EVs is their poor production yield

(16). Therefore, to overcome

this limitation, a mini extruder system was developed, and

>100-fold greater EV-mimetic NVs were extracted from different

cell types, such as embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and mouse cavernous

pericytes (MCPs). In addition, ESC-derived EV-mimetic NVs (ESC-NVs)

and MCP-derived EV-mimetic NVs (PC-NVs) showed similar qualities to

natural EVs, thus might be helpful for studies on neurovascular

regeneration (17,18). However, the detailed molecular

mechanisms by which PC-NVs promote nerve regeneration remains

largely unknown.

The sciatic nerve is the longest nerve in the human

body. It is composed of motor and sensory fibers, and has been used

as a model of neurovascular regeneration. Regeneration of severed

nerves requires polarized vasculature induced by macrophages in the

hypoxic bridge to guide the collective migration of Schwann cells

(19). Our recent studies showed

that ESC-NVs could rescue erectile function in diabetic mice,

whereas PC-NVs significantly improved erectile dysfunction in a

mouse cavernous nerve injury (CNI) model (17,18). However, there are no studies

assessing the functional evaluation of PC-NVs in the peripheral

nervous system (PNS), to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, it

was hypothesized that PC-NVs may also induce peripheral nervous

regeneration through these aforementioned effects, including

macrophage-induced angiogenesis to guide Schwann cell

migration.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the

role of PC-NVs in peripheral nerve regeneration. The results showed

that the exogenous delivery of PC-NVs increased the content of

endothelial cells, macrophages, Schwann cells and neuronal cells in

the sciatic nerve transection (SNT) model, thereby inducing

neurovascular regeneration. Therefore, we hypothesize that PC-NVs

may display a protective effect and accelerate nerve recovery,

thereby improving damaged nerve function.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement and animal study

design

In total, 85 adult male C57BL/6J mice (8 weeks old;

weight, 20-25 g; Orient Bio, Inc.) were used in the present study:

10 for the MCP primary culture and PC-NV isolation, 45 for mouse

sciatic nerve neurovascular regeneration and pathway signaling

experiments, and 30 for the motor function recovery test. All

animals' health and behavior were monitored every day and

experiments performed in this study were approved by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Inha University

(approval no. 171129-527). Mice were fed with commercial standard

laboratory food and water ad libitum, and maintained at room

temperature (23±2°C) with 40-60% humidity, specific pathogen-free

conditions and 12-h light/dark cycles. The cage, bedding, food and

water were strictly disinfected. All animals were placed under

general anesthesia with intramuscular injections of ketamine (100

mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) before preparing the models. All

animals were euthanized by 100% CO2 gas replacement rate

at 10-30% container volume/min, and cessation of the heartbeat and

respiratory arrest were confirmed before harvesting tissues. No

mice were found dead during any of the experimental procedures

MCP culture, preparation and

characterization of PC-NVs

The MCP primary cultures were performed as described

previously (20). Briefly,

8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were euthanized immediately, the

urethra and dorsal neurovascular bundle were removed from the penis

tissue and only the corpus cavernosum tissues were used. The corpus

cavernosum tissues were sectioned into 1-2 mm sections and cultured

at 37°C with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 20% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and 10 nM human pigment epithelium-derived factor

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The medium was changed every 2 days,

and the cells were sub-cultured after 10 days. Cells from passages

2-4 were used for all of the experiments.

As described in our previous study, a mini extruder

system (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) was used to prepare PC-NVs

(17). Briefly, MCPs were

detached with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) and re-suspended in HEPES buffer solution (HBS;

Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cell suspension was

extruded 10 times through filters with 10, 5 and 1 µm

polycarbonate membranes (Nuclepore; Whatman plc; Cytiva). Next,

they were subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for 2 h

at 4°C with a step gradient, which was overlapped with 50%

iodixanol (1 ml; Axis-Shield Diagnostics, Ltd.) and 10% iodixanol

(2 ml) and the extruded samples were placed (7 ml) on top. The

PC-NVs were filtered through a 0.45 µm filter (Altmann

Analytik Gmbh & Co. KG) and stored at -80°C until subsequent

analysis. The EXOCET exosome quantitation analysis kit (System

Biosciences, LLC) was used to quantify the PC-NVs, and their

concentration was adjusted to 1 µg/µl.

The morphology of the PC-NVs was detected by

transmission electron microscopy (TEM; Electron Microscopy

Sciences) as described previously (17). The PC-NVs were verified by

determining the expression of one negative and three positive NV

markers by western blotting (according to the western blotting

protocol): Golgi matrix protein 130 (GM130; negative marker; cat.

no. 610822; 1:1,000; BD Biosciences), programmed cell death

6-interacting protein (Alix; positive marker; cat. no. NB100-65678;

1:1,000; Novus Biologicals, LLC), tumor susceptibility 101 (TSG101;

positive marker; cat. no. NB200-112; 1:1,000, Novus Biologicals,

LLC) and CD81 (cat. no. NBP1-77039; positive marker; 1:1,000; Novus

Biologicals, LLC).

Fluorescence dye labelling of the PC-NVs

for the tracking analysis

The PC-NVs were labelled with

1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-Tetramethyl indodicarbo cyanine,

4-Chlorobenzene sulfonate salt (DiD) red-fluorescent dye (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Briefly, 2.5 µl DiD dye solution was added to

100 µg PC-NVs in a total volume of 500 µl HBS,

incubated at room temperature for 10 min and then further diluted

with 9.5 ml cold HBS. The samples were then ultracentrifuged at

100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C. Next, the PC-NVs pellet in HBS were

centrifuged again at 100,000 × g for 2 h at 4°C to remove the free

DiD dye. The particles containing the DiD-labeled PC-NVs were then

resuspended in HBS and used for tracking analysis.

Establishment of the sciatic nerve

crushing (SNC) and SNT model

In order to evaluate the neurovascular regenerative

ability of the PC-NVs, the SNC and SNT model were prepared as

described previously (21,22). The SNC model was used for the

tracking analysis of the injected PC-NVs. The 8-week-old male

C57BL/6J mice were immediately placed under general anesthesia with

intramuscular injections of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5

mg/kg). The right hind paw sciatic nerves were exposed and crushed

with a non-serrated needle holder under uniform pressure for 30

sec. After suturing the muscle layer, DiD-labeled PC-NVs (5

µg/100 µl) were immediately injected around the

crushed sciatic nerve, and the skin layer was sutured. A total of

24 h after SNC model preparation, the mice from all groups were

euthanized and the nerves were harvested after the confirming a

lack of heartbeat and respiratory arrest. The nerves were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. After fixing, a longitudinal

section (15 µm) was prepared and the DiD-labeled PC-NVs were

observed under a confocal fluorescence microscope (K1-Fluo;

Nanoscope Systems, Inc.).

The SNT model was used to study the sciatic nerve

function index, as well for immunofluorescence and western blot

experiments. The surgical procedure was the same as that of the SNC

model. The 8-week-old male C57BL/6J mice were immediately

anesthetized, and the right hind paw sciatic nerve was exposed and

cut across the middle of the thigh with scissors. After suturing

the muscle layer, HBS or PC-NVs (1 or 5 µg, respectively)

was immediately injected around the SNT and the skin layer was

sutured. A total of 5 and 14 days after SNT model preparation, the

mice from all of the groups were euthanized, and the nerves were

harvested after confirmation of a lack of heartbeat and respiratory

arrest. The nerves were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at

4°C and a longitudinal section (15 µm) was prepared for

subsequent experiments. A phase contrast image of the sciatic

nerves was observed under a confocal fluorescence microscope.

Histological examination

For fluorescence microscopy, the sciatic nerve

tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h at 4°C. After

blocking with 1% BSA (cat. no. A3294-50G; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) for 1 h at room temperature, the frozen tissue sections (15

µm) were incubated with antibodies against CD31 (1:50; cat.

no. MAB1398Z; MilliporeSigma), neurofilaments (NF; 1:100; cat. no.

N-5389; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), glial fibrillary acidic protein

(GFAP; 1:100; cat. no. ab53554; Abcam), ionized calcium-binding

adapter molecule 1 (Iba-1; 1:100; cat. no. ab5076; Abcam) and

neural specific 10 (SCG10; 1:100; cat. no. NBP1-49461; Novus

Biologicals, LLC) at 4°C overnight. After several washes with PBS,

the sections were incubated with secondary antibodies against FITC

Affinipure Goat anti-armenian hamster IgG (H+L) (1:100; cat. no.

127-095-160; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), rhodamine

(TRITC) Affinipure Rabbit anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (1:100; cat. no.

315-025-003; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), Alexa

Fluor 488 affinipure Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H+L) (1:100; cat. no.

705-545-147; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), Donkey

anti-Rabbit IgG H&L (DyLight® 550) (1:100; cat. no.

ab98489; Abcam) for 2 h at room temperature. After washing with

PBS, the samples were mounted in a solution containing DAPI (100

µl; cat. no. H-1500; Vector Laboratories, Inc.). DAPI was

used for nuclei labeling for 2 min at room temperature. The signals

were visualized and digital images were obtained using a confocal

fluorescence microscope (K1-Fluo; Nanoscope Systems, Inc.).

Quantitative analysis of the histological examinations was

performed using ImageJ version 1.34 (National Institutes of

Health).

Rotarod test

The rotarod test was performed on a rotarod machine

with automatic timers and falling sensors (cat. no. JD-A-07TS;

Jeung-Do Bio & Plant Co., Ltd.) as described previously

(23). The 8-week-old male

C57BL/6J mice were allowed to acclimate to the test room for 30

min. The mice were trained on the rotarod for 5 min for 3

consecutive days under the following conditions: Initially set the

rod to a low speed of 4 rpm, and then increased to 12 rpm in 1 min.

A total of 3 days later, SNT model preparation and PC-NV injections

were performed. The rotarod test was performed from 2 weeks after

SNT model preparation under the following conditions: The rotarod

was set to accelerate mode at a speed of 4-50 rpm for a maximum of

5 min. The machine automatically recorded the time and latency of

each test mouse before it fell. The longest falling latency of

three test trials was selected to represent the motor function of

each mouse. Rotarod test results were recorded at 2, 4, 6 and 8

weeks after the sciatic nerve injury. At 2 weeks after the final

rotarod test, the mice from all of the groups were euthanized.

Walking track analysis

Motor function recovery was evaluated by calculating

the sciatic nerve function index (SFI). Walking track analysis was

carried out by using open narrow corridors, and the assessment of

gait in this model has been widely used as previously described

(24). The walking track

analysis was performed immediately after the rotarod test (2, 4, 6

and 8 weeks after the sciatic nerve injury). Briefly, mouse

footprints were obtained by painting the hind paws and then letting

the mouse walk along a 5×50 cm narrow corridor covered with paper.

Based on previous a study (25),

the tracks were evaluated according to three different parameters:

i) Toe spread (TS), the distance between the first toe and the

fifth toes; ii) intermediate toe spread (IT), the distance between

the second, third and fourth toes; and iv) print length (PL), the

distance between the third toe and the hind pad. The measurements

were taken on both the experimental (E) and normal control side

(N). SFI was calculated using the following formula:

-38.3[(EPL-NPL)/NPL]+ 109.5[(ETS-NTS)/NTS]+13.3[(EIT-NIT)/NIT]-8.8

(26). An SFI value close to 0

means normal nerve function, and a value close to -100 means

complete dysfunction. All tracks were analyzed by an experimenter

blinded to the group assignments. Pawprints were recorded at 2, 4,

6 and 8 weeks after the sciatic nerve injury. At 2 weeks after the

final pawprint recordings, the mice from all of the groups were

euthanized.

Western blot

The sciatic nerve tissues (from the cut site and at

the area located 5 mm distal or proximal to the cut site) were

harvested for western blot analysis (n=4). The sciatic nerve

tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

supplemented with protease inhibitors (GenDEPOT, LLC) and

phosphatase inhibitors (GenDEPOT, LLC). Equal amounts of protein

(30 µg per lane) were subjected 8-15% SDS-PAGE and then

transferred to PVDF membranes. After blocking with 5% non-fat dry

milk for 1.5 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated at

room temperature with antibodies against brain-derived nerve growth

factor (BDNF; 1:500; cat. no. sc-546; Santa Cruz Biotechnology,

Inc.), nerve growth factor (NGF; 1:500; cat. no. sc-548; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc.), neurotrophin-3 (NT-3; 1:500; cat. no. sc-547;

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), phosphorylated (p)-PI3K (1:500;

cat. no. 4228; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), total (t)-PI3K

(1:1,000; cat. no. 4292; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), p-Akt

(1:500; cat. no 9271; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), t-Akt

(1:1,000; cat. no. 9272; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), p-c-JUN

(1:500; cat. no. 9261; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), t-c-JUN

(1:1,000; cat. no. 9165; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

p-SAPK/JNK (1:500; cat. no. 9251; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.),

t-JNK (1:1,000; cat. no. 9252; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) and

β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. ab16051; Abcam) for 2 h. The membranes

were washed three times for 10 min with PBST (0.1% Tween-20) at

room temperature. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with

goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (1:1,000; cat. no. ab6721;

Abcam) and goat anti-mouse IgG H&L (HRP) (1:1,000; cat. no.

ab6789; Abcam) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature.

The signals were visualized using an ECL (Amersham Pharmacia

Biotech, Inc.) detection system. The results were quantified by

densitometry analysis with ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM of at least

four independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed

using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test (Figs. 1-8) or an unpaired Student's t-test

(Fig. 9) in GraphPad Prism

version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

| Figure 1PC-NV isolation and characterization.

(A) Schematic diagram of the isolation of PC-NVs. (B)

Representative TEM phase images of PC-NVs. Magnification, ×100,000.

(C) Representative western blots for EV-positive markers (Alix,

TSG101 and CD81) and an EV-negative marker (GM130) in the MCP cell

lysates and PC-NVs. EV, extracellular vesicle; MCP, mouse cavernous

pericyte; PC-NV, pericyte-derived EV-mimetic nanovesicles; TEM,

transmission electron micrograph; AMT, Advanced Microscopy

Techniques; Alix, programmed cell death 6-interacting protein;

TSG101, tumor susceptibility 101; GM130, golgi matrix protein

130. |

| Figure 8PC-NVs induce neurovascular

regeneration by enhancing NF expression and survival signaling in

SNT model mice. (A) Representative western blot for NFs (BDNF, NT-3

and NGF), survival signaling (activation of PI3K and Akt) and cell

death signaling (activation of JNK and c-Jun) in sciatic nerve

tissue from SNT model mice at 5 days after injection with HBS or

PC-NVs (1 and 5 µg). Data are presented as the relative

density of (B) BDNF, (C) NGF, (D) NT-3, (E) p-PI3K/PI3K, (F)

p-Akt/Akt, (G) p-JNK/JNK and (H) p-c-Jun/c-Jun, with β-actin as the

loading control. Each bar depicts the mean ± SEM of four repeats.

The relative ratio of the HBS group was arbitrarily set to 1.

*P<0.05 vs. HBS group; #P<0.05 vs.

PC-NVs (1 µg) group. ns, not significant. HBS, HEPES buffer

solution; PC-NV, pericyte-derived extracellular vesicle-mimetic

nanovesicle; SNT, sciatic nerve transection; NF, neurotrophic

factor; BDNF, brain-derived nerve growth factor; NT-3,

neurotrophin-3; NGF, nerve growth factor. |

Results

PC-NV measurements

PC-NVs were extracted from MCPs according to

previous methods (17) and a

schematic overview of the experimental procedure is shown in

Fig. 1A. The PC-NVs exhibited a

unique cup-shaped form, similar to the shape of endogenous EVs seen

on TEM (Fig. 1B). The diameter

of the purified PC-NVs was ~30 nm. As previous studies have shown,

the NVs also expressed EV surface markers, such as Alix, TSG101 and

CD81 (17,18). Therefore, the extracted PC-NVs

were characterized by western blot analysis. The expression of

EV-positive markers, such as Alix, TSG101 and CD81, was higher in

PC-NVs than in the PC lysate. Conversely, the expression of the

EV-negative marker, GM130, was lower in the PC-NVs than in the PC

lysates (Fig. 1C).

PC-NVs tracking in the SNC model

In order to determine the distribution of

exogenously injected PC-NVs, DiD was used to label the PC-NVs,

which were then injected into the SNC model mice. After 24 h,

PC-NVs labelled with DiD were primarily detected in the crush site,

and only partially detected in the proximal and distal areas

(Fig. 2). This data indicated

that PC-NVs were more preferably absorbed by injured tissues.

| Figure 2Tracking analysis of DiD-red

fluorescently labeled PC-NVs in SNC model mice. DiD-labeled PC-NVs

were injected around the crushed sciatic nerve for 24 h.

Representative phase images of mice sciatic nerve longitudinal

sections showed that DiD-labeled PC-NVs were detected in the

crushed site of the SNC model mice. White arrows indicate the

absorbed PC-NVs. Scale bar in upper image, 200 µm. Scale bar

in lower image, 100 µm. PC-NV, pericyte-derived

extracellular vesicle-mimetic nanovesicle; SNC, sciatic nerve

crushing; DiD,

1,1′-Dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-Tetramethylindodicarbocyanine,

4-Chlorobenzenesulfonate salt. |

PC-NVs promote neurovascular regeneration

in the SNT model

Given that PC-NVs play critical roles in cavernous

nerve injury induced erectile dysfunction (18), we hypothesized that the PC-NVs

could also influence neurovascular regeneration in peripheral

nerves, such as the sciatic nerve. In order to determine the effect

of PC-NVs on sciatic nerve regeneration, SNT was performed and

PC-NVs (1 and 5 µg) were injected after the transection

surgery (Fig. 3A). At day 5,

phase images of the sciatic nerve showed that the high-dose of

PC-NVs (5 µg) group transection region contained a notable

influx of blood vessels compared with the HBS group. Interestingly,

the number of blood vessels increased markedly at the proximal

stump rather than the distal stump (Fig. 3B). At day 14, phase images of the

sciatic nerves showed that, compared with the HBS group, the

sciatic nerve link in the high-dose of PC-NVs (5 µg) group

appeared to be closer and stronger (Fig. 3C).

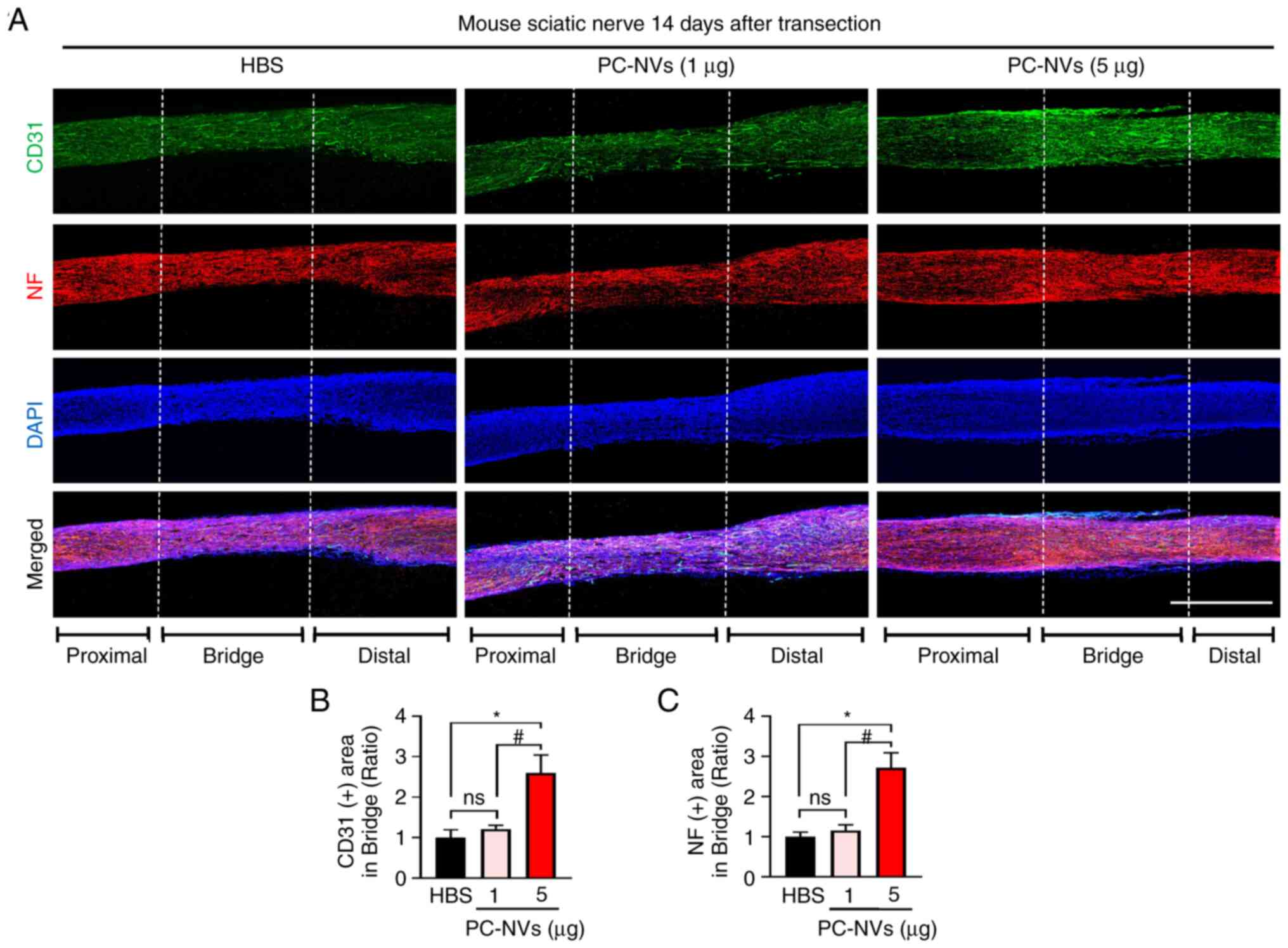

In addition, consistent with the sciatic nerve phase

images, immunofluorescence staining of the sciatic nerve with CD31

(an endothelial cell marker) and NF (an axonal marker) revealed

that the high-dose of PC-NVs significantly induced the endothelial

cells and axonal content compared with the HBS group, which may

have led to the sciatic nerve becoming more vascularized. A low

dose of PC-NVs (1 µg) injection showed a partial effect on

sciatic nerve neurovascular regeneration (Fig. 4). At day 14, the CD31 and NF

immunofluorescence staining showed that the blood vessels and axons

succeeded in crossing the bridged part in the PC-NVs (5 µg)

group (Fig. 5). Taken together,

these data showed that PC-NVs promoted neurovascular regeneration

in the SNT model.

PC-NVs promote macrophage and Schwann

cell content in the SNT model mice

During the regeneration of the sciatic nerve,

macrophages play an important role in inducing the polarized

vasculature in the nerve bridge and in guiding the migration of

Schwann cells during (19,21). To determine whether PC-NVs could

regulate the expression of macrophages to promote sciatic nerve

regeneration, immunofluorescence staining of the sciatic nerve with

Iba-1 (a macrophage marker) and GFAP (a Schwann cell marker) was

performed. The results showed that the high-dose of PC-NVs

significantly increased the presence of macrophages and Schwann

cells compared with the HBS group. Injection of a low dose of

PC-NVs only resulted in a significant increase in the presence of

macrophages, but not Schwann cells. In addition, both Iba-1 and

GFAP expression levels were high in the proximal transected site,

but not the distal site in the high-dose PC-NVs treatment group

(Fig. 6). These data are

consistent with previous studies showing (19,27) that the increased presence of

macrophages may provide signals to direct the movement of Schwann

cells to assist them in crossing the gap left by the wound during

the early stages of sciatic nerve regeneration.

PC-NVs promote nerve regeneration in SNT

model mice

SCG10 is expressed in adult sensory neurons and is

an effective and selective marker for sensory axon regeneration

during the early stages of axon regeneration (28). Therefore, in order to evaluate

the regenerative state in the early stage of axonal regeneration,

immunofluorescence staining was performed for SCG10 in the SNT

tissues after 5 days of treatment with PC-NVs. The results showed

that, compared with the HBS group, low-dose and high-dose PC-NV

treatment significantly increased the levels of SCG10 in the area

of bridge (Fig. 7). This finding

indicated that PC-NVs promoted nerve regeneration by increasing

axon regeneration in the early stages of sciatic nerve

regeneration.

PC-NVs induced neurovascular regeneration

by enhancing expression of NFs and survival signaling in SNT model

mice

In the mammalian PNS, growth factor-mediated

PI3K/Akt signaling is associated with intrinsic neurite outgrowth

and synaptic plasticity (29).

Consistent with previous reports (18,29), it was found that PC-NVs also

significantly upregulated the expression of NFs (BDNF, NT-3 and

NGF) and cell survival signaling-related proteins (PI3K/Akt

signaling), whereas cell death signaling-related proteins, such as

JNK, were significantly attenuated in the SNT model mice compared

with those in the HBS group (Fig.

8). Collectively, these results suggested that regulation of

BDNF, NT-3, NGF, PI3K, Akt, JNK and c-JUN occurred via

PC-NV-mediated neurovascular regeneration in SNT model mice.

PC-NVs promote the recovery of sciatic

nerve function in SNT model mice

In order to evaluate the motor coordination, balance

and sensory function recovery of the injured sciatic nerve, most

researchers use the rotarod test and walking track analysis

(23). Therefore, SNT was

performed on mice locally treated with a high-dose of PC-NVs (5

µg) around the transected site of the sciatic nerves and

then made to undergo the rotarod test and walking track analysis

every 2 weeks for a total of 8 weeks. The sensory motor

coordination was evaluated by measuring the SFI. The results showed

that the toe extension of SNT model mice was notably reduced

compared with that in the uncut group; however, after 8 weeks of

local application of PC-NVs in SNT model mice, toe extension

abilities were markedly improved (Fig. 9A). In the accelerating rotarod

examination, local application of PC-NVs improved motor functions

(latency and speed to fall) significantly from 4 weeks onwards

compared with those in the transfected group (Fig. 9B and C). In addition, in the

walking track analysis, walking patterns were analyzed to evaluate

sensory and motor functionality during exercise. The pace of a

normal mouse and an SNT mouse is shown in Fig. 9D. The SFI score was measured from

0 to 8 weeks after SNT. At 2 weeks after SNT, mice showed obvious

neurological dysfunction (SFI score, -69±2.35). However, after

PC-NV treatment, the SFI score improved significantly from 4 weeks

(SFI score, -44±2.58) to 8 weeks (SFI score, -28±4.98) after SNT

(Fig. 9E). Taken together, the

functional examinations showed that the local application of PC-NVs

significantly improved the impaired motor and sensory function in

SNT model mice.

Discussion

Compared with the CNS, one of the conspicuous

characteristics of the PNS is its greater regenerative ability

(30). Although peripheral axons

can regenerate and form functional connections, factors such as

age, delay before intervention and type of injury determine the

degree of functional recovery after repair (31,32). Therefore, in order to improve

regeneration, increasing the speed of axonal growth, increasing

neuron survival and preventing neuronal apoptosis are potential

strategies. In the present study, it was demonstrated that

exogenous PC-NVs were capable of improving the injured sciatic

nerve through the increased expression of NFs, promotion of the

cell survival signaling pathway and attenuation of the apoptotic

signaling pathway. Thus, determining the functions of PC-NVs and

identifying its detailed mechanisms may provide important clues to

assist in developing a rapid and effective treatment strategy for

the repair of peripheral nerve damage with limited side

effects.

Pericytes play a crucial role in the early phases of

angiogenesis in damaged tissue, such as disintegration of the

basement membrane and directing endothelial sprouting for

angiogenesis (33). Previously,

a relationship between peripheral nerve regeneration and

angiogenesis following nerve damage was discovered (11,19). Previous studies showed how

various NVs, such as PC-NVs and ESC-derived EV-mimetic NVs

(ESC-NVs), could restore the erectile function of the autonomic

nervous system of diabetic mice (17,18). Therefore, it was hypothesized

that PC-NVs may play a beneficial role in the PNS.

To evaluate this hypothesis, PC-NVs were injected

around the sciatic nerve immediately after transection. According

to previous studies, the time point for sciatic nerve neurovascular

regeneration is 5 days for angiogenesis and 14 days for nerve

regeneration (19,34). In the present study, high-dose

PC-NVs (5 µg) significantly promoted angiogenesis at the

proximal stump in the transected sciatic nerve 5 days after

treatment, and the sciatic nerve connections were closer and

stronger in the PC-NVs (5 µg) treatment group after 14 days

of treatment. In addition, a previous study showed that macrophages

may detect hypoxia within the neural bridge and generate a

polarized vasculature, which provides a scaffold for Schwann cell

migration (19). Schwann cells

have been shown to migrate with blood vessels to damaged tissues,

produce neurotrophic substances and use autophagy to clear the

necrotic tissue produced by Wallerian degeneration, thereby

promoting nerve regeneration (35). Consistently, the present study

showed that PC-NVs increased the content of endothelial cells

(CD31), macrophages (Iba-1) and Schwann cells (GFAP), and enhanced

SCG10 expression in the transected sciatic nerve bridge. Based on

these results, it was hypothesized that the Schwann cells induced

by PC-NVs might be involved in the removal of necrotic tissues

produced by Wallerian degeneration. However, at present, there are

no relevant experimental results to support this hypothesis, thus

more detailed experiments are required to assess. These findings

strongly suggested that PC-NVs may serve an important role in

peripheral nerve neurovascular regeneration.

It has been reported that Schwann cell-derived NVs

could increase the production of NFs (BDNF, NT-3 and NGF), thereby

improving neurite outgrowth in vitro (36). The activation of Akt signaling

has been shown to promote cell proliferation and the migration of

multiple cell types (37). In

addition, previous studies have also shown that PC-NVs could

improve erectile function by enhancing the expression of NFs and

activating survival signaling in a mouse CNI model (18). Consistently, it was also found

that a high-dose of PC-NVs significantly enhanced these

factors.

Finally, in order to evaluate the role of PC-NVs in

PNS functional regeneration, a rotarod test and walking track

analysis were performed in the present study. The results showed

that from 4 weeks after treatment, high-dose PC-NVs significantly

improved the sensory-motor coordination and motor function. These

findings indicated that local injection of PC-NVs may be a

promising strategy for the treatment of peripheral nerve

injury.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study was

the first to evaluate the therapeutic impact of PC-NVs in sciatic

nerve injury models. The current research did have several

limitations. Only the effect of PC-NVs injected immediately after

nerve injury was evaluated, and different time frames between

injury and treatment should be assessed to determine the optimal

time frame. Only male mice were used to prepare SNC and SNT models;

therefore, the use of both female and male mice may be more

meaningful for experimental study. The present study did elucidate

which components of PC-NVs were involved in neurovascular

regeneration and how long PC-NVs remained at the injection site.

Additional studies to evaluate which components of PC-NVs play a

role in neurovascular regeneration may help in understanding the

detailed mechanism of action of PC-NVs in neurovascular

regeneration.

In summary, the present study showed that PC-NVs

significantly enhanced cell survival signaling and the expression

of NFs in neurovascular regeneration in the SNT mouse model. Thus,

PC-NVs may serve as a novel treatment strategy for management of

neurovascular diseases.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

GNY, TYS, JO, JKS and JKR conceived and designed the

study. GNY, TYS, JO, MJC, AL, MHK, FYL, SSH, JHK and YSG performed

the experiments, the data collection, statistical analysis, data

interpretation. GNY, TYS, and JO confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. GNY, TYS, JO and JKR wrote the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The experiments performed with animals were approved

by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Inha

University (Incheon, Republic of Korea; approval no.

171129-527).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of

Korea (grant no. 2019R1A2C2002414), the Medical Research Center

(grant no. NRF-2021R1A5A2031612), the Joint Grant [composed of the

Korean government (Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning),

the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the

National Research Foundation and the Korean government (MSIT);

grant no. 2019069621] and the National Research Foundation of Korea

(grant no. 2021R1A2C4002133).

References

|

1

|

Thomas S, Ajroud-Driss S, Dimachkie MM,

Gibbons C, Freeman R, Simpson DM, Singleton JR, Smith AG; PNRR

Study Group; Höke A: Peripheral neuropathy research registry: A

prospective cohort. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 24:39–47. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Peters BR, Russo SA, West JM and Moore AM:

Schulz SA. Targeted muscle reinnervation for the management of pain

in the setting of major limb amputation. SAGE Open Med.

8:20503121209591802020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Korus L, Ross DC, Doherty CD and Miller

TA: Nerve transfers and neurotization in peripheral nerve injury,

from surgery to rehabilitation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry.

87:188–197. 2016.

|

|

4

|

Hoshal SG, Solis RN and Bewley AF: Nerve

grafts in head and neck reconstruction. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head

Neck Surg. 28:346–351. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Vijayavenkataraman S: Nerve guide conduits

for peripheral nerve injury repair: A review on design, materials

and fabrication methods. Acta Biomater. 106:54–69. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Al-Massri KF, Ahmed LA and El-Abhar HS:

Mesenchymal stem cells in chemotherapy-induced peripheral

neuropathy: A new challenging approach that requires further

investigations. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 14:108–122. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Geranmayeh MH, Rahbarghazi R and Farhoudi

M: Targeting pericytes for neurovascular regeneration. Cell Commun

Signal. 17:262019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Tamaki T, Hirata M, Nakajima N, Saito K,

Hashimoto H, Soeda S, Uchiyama Y and Watanabe M: A long-gap

peripheral nerve injury therapy using human skeletal muscle-derived

stem cells (Sk-SCs): An achievement of significant morphological,

numerical and functional recovery. PLoS One. 11:e01666392016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rivera FJ, Hinrichsen B and Silva ME:

Pericytes in multiple sclerosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1147:167–187.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kisler K, Nelson AR, Rege SV, Ramanathan

A, Wang Y, Ahuja A, Lazic D, Tsai PS, Zhao Z, Zhou Y, et al:

Pericyte degeneration leads to neurovascular uncoupling and limits

oxygen supply to brain. Nat Neurosci. 20:406–416. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Yin GN, Jin HR, Choi MJ, Limanjaya A,

Ghatak K, Minh NN, Ock J, Kwon M, Song KM, Park HJ, et al:

Pericyte-derived Dickkopf2 regenerates damaged penile

neurovasculature through an angiopoietin-1-Tie2 pathway. Diabetes.

67:1149–1161. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li C, Qin F, Hu F, Xu H, Sun G, Han G,

Wang T and Guo M: Characterization and selective incorporation of

small non-coding RNAs in non-small cell lung cancer extracellular

vesicles. Cell Biosci. 8:22018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

O'Brien K, Breyne K, Ughetto S, Laurent LC

and Breakefield XO: RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in

mammalian cells and its applications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

21:585–606. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Mäe MA, He L, Nordling S, Vazquez-Liebanas

E, Nahar K, Jung B, Li X, Tan BC, Foo JC, Cazenave-Gassiot A, et

al: Single-cell analysis of blood-brain barrier response to

pericyte loss. Circ Res. 128:e46–e62. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Liu Y and Holmes C: Tissue regeneration

capacity of extracellular vesicles isolated from bone

marrow-derived and adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal/stem cells.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:6480982021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kim OY, Lee J and Gho YS: Extracellular

vesicle mimetics: Novel alternatives to extracellular vesicle-based

theranostics, drug delivery, and vaccines. Semin Cell Dev Biol.

67:74–82. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Kwon MH, Song KM, Limanjaya A, Choi MJ,

Ghatak K, Nguyen NM, Ock J, Yin GN, Kang JH, Lee MR, et al:

Embryonic stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle-mimetic

nanovesicles rescue erectile function by enhancing penile

neurovascular regeneration in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic

mouse. Sci Rep. 9:200722019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Yin GN, Park SH, Ock J, Choi MJ, Limanjaya

A, Ghatak K, Song KM, Kwon MH, Kim DK, Gho YS, et al:

Pericyte-derived extracellular vesicle-mimetic nanovesicles restore

erectile function by enhancing neurovascular regeneration in a

mouse model of cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. 17:2118–2128.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cattin AL, Burden JJ, Van Emmenis L,

Mackenzie FE, Hoving JJA, Calavia NG, Guo Y, McLaughlin M,

Rosenberg LH, Quereda V, et al: Macrophage-induced blood vessels

guide schwann cell-mediated regeneration of peripheral nerves.

Cell. 162:1127–1139. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yin GN, Park SH, Song KM, Limanjaya A,

Ghatak K, Minh NN, Ock J, Ryu JK and Suh JK: Establishment of in

vitro model of erectile dysfunction for the study of

high-glucose-induced angiopathy and neuropathy. Andrology.

5:327–335. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Meng FW, Jing XN, Song GH, Jie LL and Shen

FF: Prox1 induces new lymphatic vessel formation and promotes nerve

reconstruction in a mouse model of sciatic nerve crush injury. J

Anat. 237:933–940. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chen B, Carr L and Dun XP: Dynamic

expression of Slit1-3 and Robo1-2 in the mouse peripheral nervous

system after injury. Neural Regen Res. 15:948–958. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lim EF, Nakanishi ST, Hoghooghi V, Eaton

SE, Palmer AL, Frederick A, Stratton JA, Stykel MG, Whelan PJ,

Zochodne DW, et al: AlphaB-crystallin regulates remyelination after

peripheral nerve injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114:E1707–E1716.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Lee JI, Hur JM, You J and Lee DH:

Functional recovery with histomorphometric analysis of nerves and

muscles after combination treatment with erythropoietin and

dexamethasone in acute peripheral nerve injury. PLoS One.

15:e02382082020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kaka G, Arum J, Sadraie SH, Emamgholi A

and Mohammadi A: Bone marrow stromal cells associated with poly

L-Lactic-Co-Glycolic acid (PLGA) nanofiber scaffold improve

transected sciatic nerve regeneration. Iran J Biotechnol.

15:149–156. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Moldovan M, Pinchenko V, Dmytriyeva O,

Pankratova S, Fugleholm K, Klingelhofer J, Bock E, Berezin V,

Krarup C and Kiryushko D: Peptide mimetic of the S100A4 protein

modulates peripheral nerve regeneration and attenuates the

progression of neuropathy in myelin protein P0 null mice. Mol Med.

19:43–53. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Stratton JA, Holmes A, Rosin NL, Sinha S,

Vohra M, Burma NE, Trang T, Midha R and Biernaskie J: Macrophages

regulate schwann cell maturation after nerve injury. Cell Rep.

24:2561–2572.e6. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Kim KJ and Namgung U: Facilitating effects

of Buyang Huanwu decoction on axonal regeneration after peripheral

nerve transection. J Ethnopharmacol. 213:56–64. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Li R, Li DH, Zhang HY, Wang J, Li XK and

Xiao J: Growth factors-based therapeutic strategies and their

underlying signaling mechanisms for peripheral nerve regeneration.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 41:1289–1300. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

El Seblani N, Welleford AS, Quintero JE,

van Horne CG and Gerhardt GA: Invited review: Utilizing peripheral

nerve regenerative elements to repair damage in the CNS. J Neurosci

Methods. 335:1086232020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kuffler DP and Foy C: Restoration of

neurological function following peripheral nerve trauma. Int J Mol

Sci. 21:18082020. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

32

|

Alsmadi NZ, Bendale GS, Kanneganti A,

Shihabeddin T, Nguyen AH, Hor E, Dash S, Johnston B, Granja-Vazquez

R and Romero-Ortega MI: Glial-derived growth factor and

pleiotrophin synergistically promote axonal regeneration in

critical nerve injuries. Acta Biomater. 78:165–177. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Sweeney M and Foldes G: It takes two:

Endothelial-perivascular cell cross-talk in vascular development

and disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 5:1542018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Wang H, Zhu H, Guo Q, Qian T, Zhang P, Li

S, Xue C and Gu X: Overlapping mechanisms of peripheral nerve

regeneration and angiogenesis following sciatic nerve transection.

Front Cell Neurosci. 11:3232017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Chen G, Luo X and Wang W, Wang Y, Zhu F

and Wang W: Interleukin-1β promotes schwann cells

de-differentiation in wallerian degeneration via the c-JUN/AP-1

pathway. Front Cell Neurosci. 13:3042019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Rhode SC, Beier JP and Ruhl T: Adipose

tissue stem cells in peripheral nerve regeneration-in vitro and in

vivo. J Neurosci Res. 99:545–560. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Manning BD and Toker A: AKT/PKB signaling:

Navigating the network. Cell. 169:381–405. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|