Introduction

Myocardial infarction (MI) remains the leading

cardiovascular disease worldwide and the number of people with

cardiovascular disease is expected to increase by 40.5% by 2030,

which imposes a substantial economic burden on society (1). While blood reperfusion strategies

effectively reduce the risk of death in patients with MI, the

restoration of blood and oxygen to regions of ischemic myocardium

can result in additional cardiac damage and complications known as

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (MIRI) (2). MIRI is characterized by

pathophysiological phenomena, such as excessive calcium influx,

reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, impaired endothelial

function, disturbances in mitochondrial function and autophagy of

cardiomyocytes (3,4). Owing to the complexity of the

molecular mechanisms of MIRI, a single therapeutic regimen has not

shown satisfactory therapeutic outcomes, indicating that targeting

multiple pathophysiological features may lead to improved

therapeutic outcomes (5,6). Of note, many studies have shown

that blood reperfusion therapy combined with drugs can effectively

reduce MIRI and improve the heart pumping function (7-9).

Turmeric has been used for the treatment of cancer,

neurological disorder, chronic inflammation and cardiovascular

disease in traditional Chinese medicine (10,11). The plant has been found to

contain several active compounds, of which curcumin (Cur) is the

primary component (12). Cur

scavenges free radical activity and maintains cellular function

through various molecular mechanisms (13). There is increasing evidence that

Cur exhibits cardioprotective effects in cardiovascular disease

(14,15). A pharmacological study by Hong

et al (16) demonstrated

that a continuous 3-day Cur treatment (75 mg/kg/day) regimen

improves cardiac function and reduced MI size. Duan et al

(17) showed that the Cur-based

modulation of the JAK2/STAT3 pathway attenuates IRI, significantly

reducing infarct size and ROS levels. In addition to directly

modulating downstream molecular activity, Cur attenuates

mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress mediated by MIRI

(18). Based on the

cardioprotective effects of Cur via inhibition of the different

modes of regulated cell death (13), it was hypothesized that Cur

attenuates MIRI through multiple pathways.

Ferroptosis is a newly defined form of

iron-dependent cell death characterized by ROS production and lipid

peroxidation (19). The

mechanisms by which ferroptosis occurs differ from those of

apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. However, there is a complex

crosstalk between these processes (20,21). Ferroptosis is characterized by an

imbalance in iron metabolism, which induces production of large

amounts of ROS and lipid peroxides that lead to cell death

(22,23). Excessive iron deposition can lead

to pathological iron overload; excess iron in cardiomyocytes can

directly induce ferroptosis via accumulation of phospholipid

hydroperoxides in the cell membrane (24). Increasing evidence has suggested

that iron overload during MIRI is associated with the activation of

ferritin phagocytosis, in which autophagic vesicles release ferric

ions into labile iron pools by interacting with ferritin heavy

chain 1 (FTH1) via nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), directly

contributing to impaired iron metabolism in cardiomyocytes

(25,26). In addition, iron can catalyze ROS

production via the Fenton reaction and promote lipid peroxidation,

causing further oxidative injury to cells (19). In summary, autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis-mediated pathological iron deposition may exacerbate

MIRI, but the associated molecular mechanisms have not been

elucidated. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family member 1 protects

against cardiac ischemic injury by decreasing forkhead box O3A

(FoxO3a) phosphorylation and sequestering it in the cytoplasm to

inhibit autophagy (27).

Therefore, it was hypothesized that Cur modulates localization of

FoxO3a in cardiomyocytes, thereby regulating autophagy and

attenuating ferroptosis.

Silent information regulator 1 (Sirt1), a class III

histone deacetylase (28), is

involved in regulation of cell energy metabolism, senescence and

the transcription of oxidative stress-associated factors (29). In addition, Sirt1 can exhibit

chromatin-modifying activity and maintenance of gluconeogenesis,

fatty acid oxidation, oxidative phosphorylation and other processes

depends on the regulation of Sirt1 (29,30). Thus, Sirt1 regulates multiple

molecular mechanisms to maintain cardiac function.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway is activated by

Sirt1 to promote endothelial histiocyte migration and

proliferation, which may be achieved by promoting phosphorylation

of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) (31). In the heart, Sirt1 can block the

accumulation of FoxO1 via the PI3K/AKT pathway, decreasing ROS

levels and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the diabetic heart and

ameliorating metabolic abnormalities. Nevertheless, the molecular

mechanism between Sirt1 and MIRI remains unclear. Furthermore, the

ability of Cur to regulate downstream molecules via Sirt1 to

alleviate MIRI requires further investigation.

Here, a H9c2 cell anoxia/reoxygenation (A/R) and a

rat MIRI model were used to verify whether MIRI induces

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis and whether Cur attenuates MIRI by

attenuating autophagy-dependent ferroptosis, to investigate whether

the cardioprotective effect of Cur is related to the

Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a pathway.

Materials and methods

Materials

Cur (purity ≥98%, batch no. DC0279-0005) was

purchased from Dester Technology Co., Ltd. and Akt inhibitor

triciribine (API-2; cat. no. GC15392) was purchased from GLPBIO

Technology LLC. In addition, 3-methyladenine (3-MA, cat. no.

HY-19312), an inhibitor of autophagy, was procured from

MedChemExpress. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) specific to Sirt1,

along with non-specific siRNA (scrambled control), were synthesized

by RIBOBIO Co., Ltd. The primary antibodies targeting Bcl-2 (cat.

no. 381702), Bax (cat. no. R22708), Sirt1 (cat. no. R25721), FTH1

(cat. no. R23306), phosphorylated (p-) FoxO3a (cat. no. R24347),

FoxO3a (cat. no. 381451) and microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3β (LC3II; cat. no. 381544) as well as anti-rabbit (cat. no.

550076) and anti-mouse (cat. no. 550047) secondary antibodies

conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP) were sourced from

ZEN-BIOSCIENCE Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primary antibodies against

caspase 3 (cat. no. AF7022) and P62 (cat. no. AF5384) were

purchased from Affinity Biosciences Co., Ltd. Primary antibodies

targeting β-actin (cat. no. 20536-1-AP) and PCNA (cat. no.

60097-1-Ig) were sourced from Proteintech Inc. Finally, primary

antibodies targeting NCOA4 (cat. no. A5695) were sourced from

ABclonal Technology Co., Ltd. and antibodies against p-AKT (cat.

no. 9271) and AKT (cat. no. 9272) were sourced from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.

Sprague Dawley (SD) rats and H9c2

cells

A total of 18 adult male SD rats (weight, 250±20 g;

age, 8 weeks) were sourced from Tianqin Biotechnology Co. The

experimental protocols were performed following principles

established by the National Institutes of Health regarding the

treatment and utilization of laboratory animals (32). The research protocol was approved

by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Nanchang University (approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202211QR010).

H9c2 cells were sourced from the Cell Bank or Stem

Cell Bank at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The cells were

cultured in DMEM (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.),

supplemented with 10% FBS (HyClone; Cytiva), in a 37°C incubator

containing 5% CO2 and 21% O2 at 95%

humidity.

Animal experiments

All rats had unrestricted access to water and food,

a temperature range of 22-24°C, humidity of 40-60%, and a 12/12-h

light/dark cycle. To simulate MIRI, SD rats were anesthetized with

2.5% isoflurane gas inhalation and 100 mg/kg ketamine

intraperitoneal injection. The rats were tracheally intubated and

connected to a ventilator to maintain respiration. To maintain body

temperature, anesthetized SD rats were positioned on a continuously

heated plate. The hair on the left chest was removed and the chest

cavity opened at the fourth intercostal space to expose the heart.

A 7-0 silk suture was used to ligate the left anterior descending

coronary artery and the ligature wire was removed after 30 min

ischemia, followed by 2 h of reperfusion after chest closure. Any

residual intrathoracic air was removed before closing the chest

with a 4-0 wire silk suture.

A total of 18 SD rats were randomly assigned to one

of three groups (n=6/group): Sham, SD rats were fed routinely and

underwent open chest surgery without ligation; I/R, SD rats were

subjected to continuous intraperitoneal injection of saline before

induction of MIRI and I/R + Cur, Cur (50 mg/kg) was injected

continuously intraperitoneally for 4 weeks before induction of MIRI

(13). Rats were checked daily

for weight, health and behavior. The following conditions were

defined as humane endpoints: i) Weight loss >20%; ii) inability

to eat, drink or stand; iii) depression (immobility, sniffing,

trembling, scratching) and body temperature <37°C in

unanesthetized or sedated animals and iv) abnormal central nervous

system responses and inability to effectively control pain (foot

retraction and licking and abdominal retraction). The total

duration of the experiment was 4 weeks and no humane endpoints were

observed in all animals. All rats were subjected to blood sampling

and echocardiographic assessment at the end of the experiment. Rats

were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation at a flow rate of

60% of luminal volume/min according to the American Veterinary

Medical Association guidelines for animal euthanasia (33), and death was confirmed based on

respiratory arrest and loss of muscle tone.

Echocardiographic measurement

SD rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation

(induction and maintenance concentration of isoflurane were 2.5%)

with 1 l/min O2. An echocardiographic probe (V6, 23 MHz

linear transducer, VINNO) was placed anteriorly on the left chest

wall to assess left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and left

ventricular shortening fraction (LVFS). For each parameter, three

individual measurements were performed and the mean value was

subsequently computed (34).

Determination of lactate dehydrogenase

(LDH) and creatine kinase isoenzyme (CK-MB) levels

SD rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation

(induction and maintenance, 2.5%) with 1 l/min O2,

connected to a ventilator and fixed on a continuously heated plate.

After MIRI induction, heart function was assessed using an

echocardiography system (V6, 23 MHz linear transducer, VINNO).

Then, 0.5 ml blood samples were taken by cardiac puncture and

collected in a heparinized tube. Rats were euthanized and their

hearts were rapidly harvested, cleaned with PBS and stored in

liquid nitrogen (-210°C) for subsequent experiments (13). The blood samples were stored

overnight at 4°C and centrifuged for 15 min to obtain serum (13,400

× g, 4°C). LDH and CK-MB levels were determined using assay kits

according to the manufacturer's instructions (cat. nos. E006-1-1;

A020-2-2; both Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute).

Evans blue and triphenyl tetrazolium

chloride (TTC) staining

SD rats were anesthetized with isoflurane inhalation

(induction and maintenance; 2.5%) with 1 l/min O2,

connected to a ventilator and fixed on a continuously heated plate.

The chest was opened in the left anterior thoracic region between

the 4 and 5th intercostal spaces and the left anterior descending

flow was blocked by ligating a 7-0 silk thread and injecting Evans

blue dye (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat.

no. E8010) from the apex of the heart until cardiac arrest. The

hearts were removed and frozen at -80°C for 30 min, sliced (2 mm

thickness) and incubated in 2% TTC solution (Merck KGaA; cat. no.

298-96-4) at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. The images were captured

using a digital camera (×5; EOS M200; Canon; n=3/group) and

analyzed using the ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health).

Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and TUNEL

staining

Isolated rat hearts were fixed in 10%

paraformaldehyde for 24 h at room temperature and embedded in

paraffin. To determine the extent of cardiomyocyte apoptosis and

necrosis, sections (5 μm) were prepared and subjected to HE

(cat. no. G1005) and TUNEL staining (both Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. G1507) kits according to the

manufacturer's instructions (n=3/group). Sections were stained with

0.50 hematoxylin for 10 and 0.05% eosin for 2 min at room

temperature. TdT incubation buffer (2 μl recombinant TdT

enzyme, 5 μl biotin-dUTP labeling mix, 50 μl

equilibration buffer) was added at 37°C for 1 h and sections were

washed 3 times with PBS, 0.5% streptavidin-HRP buffer was incubated

at 37°C for 30 min and then washed 3 times with PBS, 5% DAB

chromogenic solution was added at room temperature for 30 min and

then washed 3 times with PBS, and 0.5% hematoxylin staining

solution was stained at room temperature for 5 min. Percentage of

TUNEL-positive nuclei=number of TUNEL-positive nuclei (brown

staining) in 3 different fields of view/total nuclei ×100%. The

images were captured from three fields per slide using a light

microscope (BX53, Olympus Corporation) at a magnification of

×400.

Cell transfection

siRNA against Sirt1 (si-Sirt1) and the non-targeting

control siRNA (si-NC; cat. no. siN0000001-1-5; both Guangzhou

RiboBio Co., Ltd.; Table SI)

were introduced into H9c2 cells. Transfection was performed using

jetPRIME (Polyplus-transfection SA; cat. no. 101000006) according

to the manufacturer's protocol. A total of 5 μl si-RNA (20

μM), 200 μl jetPRIME buffer, 5 μl jetPRIME

reagent were mixed for 20 min at room temperature, followed by the

addition of the above complexes to 2 ml of culture DMEM (Final

siRNA concentration was 50 nM), and transfected for 8 h at 37°C.

Following transfection, cells were allowed to recover for 24 h

before subsequent experimentation. Transfection efficiency was

determined via reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR and

western blotting.

Cell treatment

H9c2 cell A/R model was established as previously

described (35). In brief, H9c2

cells were treated with an anoxia medium (CaCl2 1.0,

HEPES 20.0, KCl 10.0, MgSO4 1.2, NaCl 98.5,

NaH2PO4 0.9, NaHcO3 6.0, sodium

lactate 40.0 mM, pH 6.8) for 4 h under oxygen-deficient conditions

(95% N2, 5% CO2; 37°C). Subsequently, the

anoxia medium was replaced with a reoxygenation medium

(CaCl2 1.0, glucose 5.5, HEPES 20.0, KCl 5.0, MgSO4 1.2

mM, NaCl 129.5, NaH2PO4 0.9 and

NaHcO3 20.0 mM, pH 7.4) and incubated for 4 h at 37°C in

an air-tight reoxygenation chamber containing 5% CO2 and

95% O2.

The experimental groups were as follows: i) control,

untreated cells; ii) A/R, cells subjected to A/R injury; iii) Cur

(2.5, 5.0, 10.0, 20.0 and 40.0 μM) + A/R, prior to A/R

injury, cells were pretreated with Cur at 37°C for 48 h; iv) Cur

(10 μM) + A/R, prior to A/R injury, cells were pretreated

with 10 μM Cur at 37°C for 48 h; v) 3-MA (5 mM)+ A/R, prior

to A/R injury, cells were treated with 5 mM 3-MA at 37°C for 24 h;

vi) Cur (10 μM) + si-NC +A/R group: prior to A/R injury,

cells were transfected with si-NC and pretreated with 10 μM

Cur at 37°C for 48 h; vii) Cur (10 μM) + si-Sirt1 + A/R,

prior to A/R injury, cells transfected with si-Sirt1 and pretreated

with 10 μM Cur at 37°C for 48 h and viii) Cur (10 μM)

+ API-2 + A/R, prior to A/R injury, cells pretreated with 10

μM Cur and 20 μM API-2 at 37°C for 48 h.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) and LDH

activity assay

Cellular viability was assessed using CCK-8 assay

(GLPBIO Technology LLC; cat. no. GK10001) according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Subsequent to A/R procedure, 100

μl serum-free DMEM containing 10 μl CCK-8 reaction

solution was introduced into a 96-well plate, and the cells were

incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the optical density

(OD) value was determined at 450 nm. Cell survival rate was

calculated as a percentage.

LDH activity was assessed using a detection kit

(cat. no. C0016; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the culture fluid or

cell lysate supernatant from each group was collected and LDH

activity was detected. The OD value was determined at 490 nm, and

the percentage of LDH activity was calculated.

Caspase 3 activity assay

Caspase 3 activity was quantified using an assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. C1116) according to

the manufacturer's instructions. First, supernatant was collected

from the H9c2 cell lysate, and protein concentration was measured

using the Bradford method. Subsequently, 40 μl activation

reagent, 50 μl cell homogenate and 10 μl caspase 3

substrates were incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Finally, the OD value

was measured at 405 nm.

Apoptosis assay

The ratio of apoptotic cells (early + late apoptotic

cells) was measured using an Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis assay kit

(BestBio, Inc.; cat. no. BB-4101) according to the manufacturer's

instructions. After harvesting treated H9c2 cells, 5 μl

Annexin V-FITC was added and incubated at 4°C for 15 min in the

dark, after which 5 μl PI was added and incubated for an

additional 5 min under the same conditions. Apoptotic cells were

detected using Cytomics FC500 flow cytometer at 488 and 578 nm,

respectively, and data were analyzed using NovoExpress (v.10.8;

Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Measurement of total iron, superoxide

dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione disulfide

(GSSG) and glutathione (GSH) levels

As previously described (30), after collecting the cell lysis

supernatant from each group, the levels of total iron (Applygen;

cat. no. E1042), SOD (cat. no. S0131S), MDA (cat. no. S0053), GSSG

(cat. no. S0101S) and GSH (all Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology;

cat. no. S0101S) as well as the ratio of GSH/GSSG were assessed

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

The intracellular level of ROS was detected using

DCFH-DA (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology; cat. no. S0033S).

Treated cells were incubated with the cell culture DMEM containing

DCFH-DA (0.1%) for 15 min at 37°C in the dark. Subsequently, ROS

levels were measured using fluorescence microscopy (×200; Olympus

IX 73, Olympus Corporation). ImageJ (version 1.8.0; National

Institutes of Health) was employed for the analysis of alterations

in fluorescence intensity across the various experimental

groups.

Detection of lysosome level

Intracellular lysosomal generation was detected

using a LysoTracker Red detection kit (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology; cat. no. C1046). Treated cells were incubated with

the cell culture DMEM containing LysoTracker (0.1%) for 15 min at

37°C in the dark. Subsequently, lysosome levels were measured using

fluorescence microscopy (×200; Olympus IX 73; Olympus Corporation).

The ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health)

was employed for the analysis of alterations in fluorescence

intensity across the various experimental groups.

Detection of ferrous iron level

The level of ferrous ion was measured via an assay

kit (Dojindo Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no. F374). Threated cells

were incubated with the cell culture DMEM containing

FerroOrangeTracker (0.1%) for 15 min at 37°C in the dark.

Subsequently, intracellular ferrous iron levels were measured using

fluorescence microscopy (×200; Olympus IX 73; Olympus Corporation).

ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes of Health) was

employed for the analysis of alterations in fluorescence intensity

across the various experimental groups.

Western blotting

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were obtained using

commercially available kits (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology;

cat. no. P0027), and total proteins were extracted from H9c2 cells

and cardiac tissue using RIPA buffer (Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology; cat. no. R0010). A bicinchoninic acid kit (GLPBIO

Technology LLC; cat. no. GK10009) was used to measure the protein

concentration. The components of protein supernatants were

denatured by boiling for 5 min following the addition of a loading

buffer. Next, 20 μg/lane protein was separated using 8-12%

sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and

transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes. Protein bands

were incubated overnight at 4°C with the primary antibody (1:1,000)

following 1 h blocking using 5% skimmed milk or 5% bovine serum

albumin (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.; cat.

no. A8020) at room temperature. Afterward, the membranes were

incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5,000;

ZEN-BIOSCIENCE Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; cat. no. 550076; 550047) at

room temperature for 2 h. The membranes were analyzed using an

ultra-high sensitivity enhanced chemiluminescence kit (GLPBIO

Technology LLC; cat. no. GK10008) and imaged with FluorChemFC3

(ProteinSimple). In this experiment, protein expression was

measured using ImageJ software (version 1.8.0; National Institutes

of Health). The relative expression of the target proteins was

obtained by comparing protein levels to β-actin levels.

RT-qPCR

As described previously (35), total RNA was extracted from H9c2

cells using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). RT kit (Vazyme Biotech, cat. no. R412-01) was used to obtain

cDNA according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reaction

solution was prepared by mixing 12 SYBR Green Mix (Selleck

Chemicals, cat. no. B21202), 1 each forward and reverse primers (10

μM), 4 cDNA and 2 μl nuclease-free water. The

reaction solution was pre-denatured at 95°C for 30 sec, followed by

40 cycles at 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min. Target gene

expression was detected using the BIO-RAD CFX detection system and

the relative expression of target genes in terms of RNA levels was

measured using the 2-ΔΔCq method (36). The primers were designed and

synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Table SII).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation

of three independent experimental repeats. GraphPad Prism software

(version 8.0.2; graphpad.com/) was used for

statistical analysis. One-way analysis of variance followed by

Tukey's post hoc multiple comparison test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Cur pretreatment attenuates A/R injury in

H9c2 cells

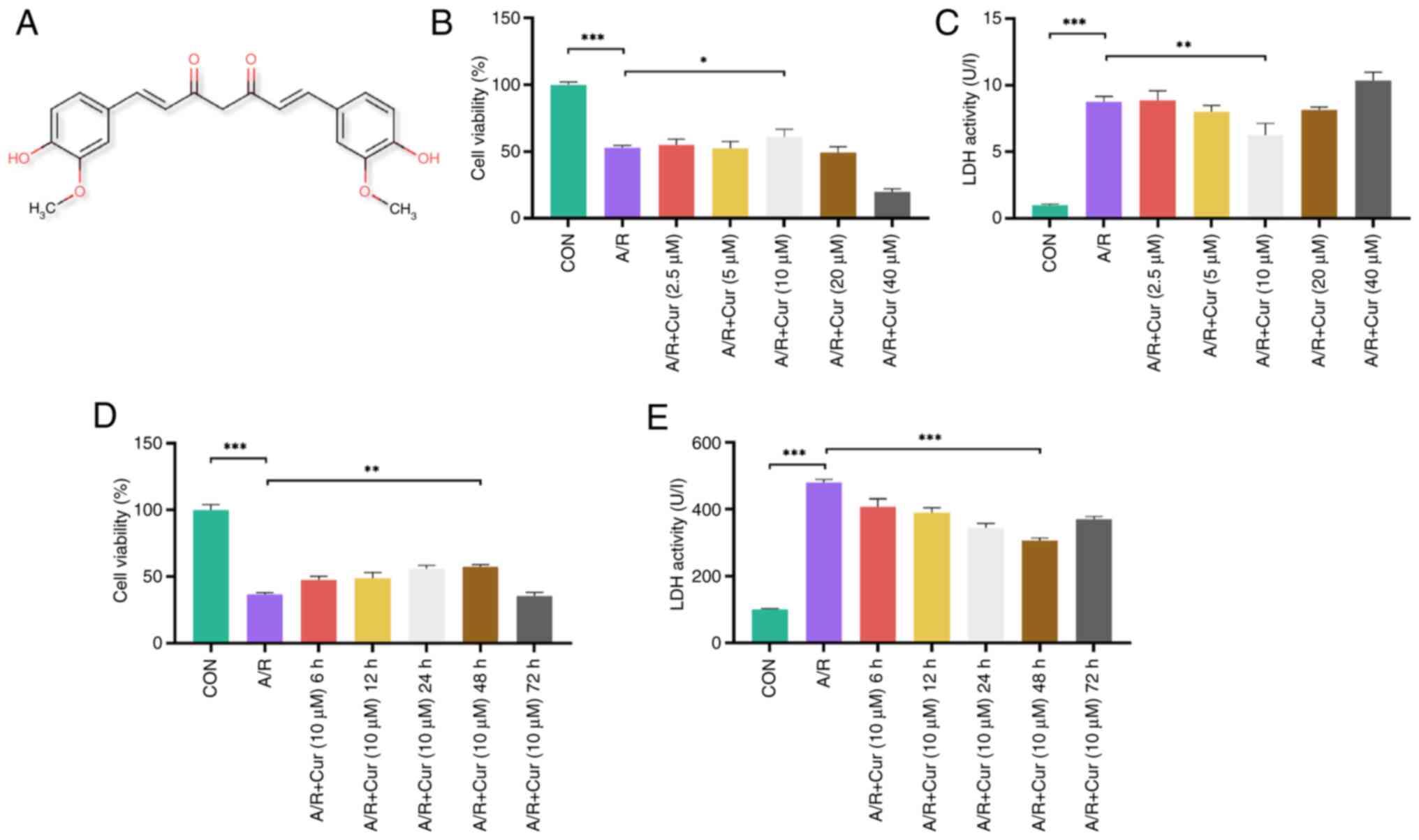

Fig. 1A

illustrates the chemical structure of Cur. CCK-8 and LDH assays

were used to identify the optimal drug treatment concentration.

H9c2 cells were pretreated with Cur, followed by A/R injury, and

cell viability and LDH release levels were assessed. A/R injury

significantly decreased cell viability and increased LDH levels.

Treatment with 10 μM Cur resulted in a significant increase

in cell viability and a decrease in LDH levels compared with the

A/R group, whereas no significant difference was observed in the 20

with the 10 μM Cur group (Fig. 1B and C). Therefore, 10 μM

Cur was deemed to represent the threshold for a safe drug

concentration and used for subsequent experiments. Significantly

higher cell viability was observed after 48 h 10 μM Cur

treatment than in the A/R group, whereas significantly lower cell

viability was observed after 72 h compared with 48 h 10 μM

Cur treatment (Fig. 1D and E).

Thus, 10 μM Cur for 48 h was selected as the optimal drug

pretreatment.

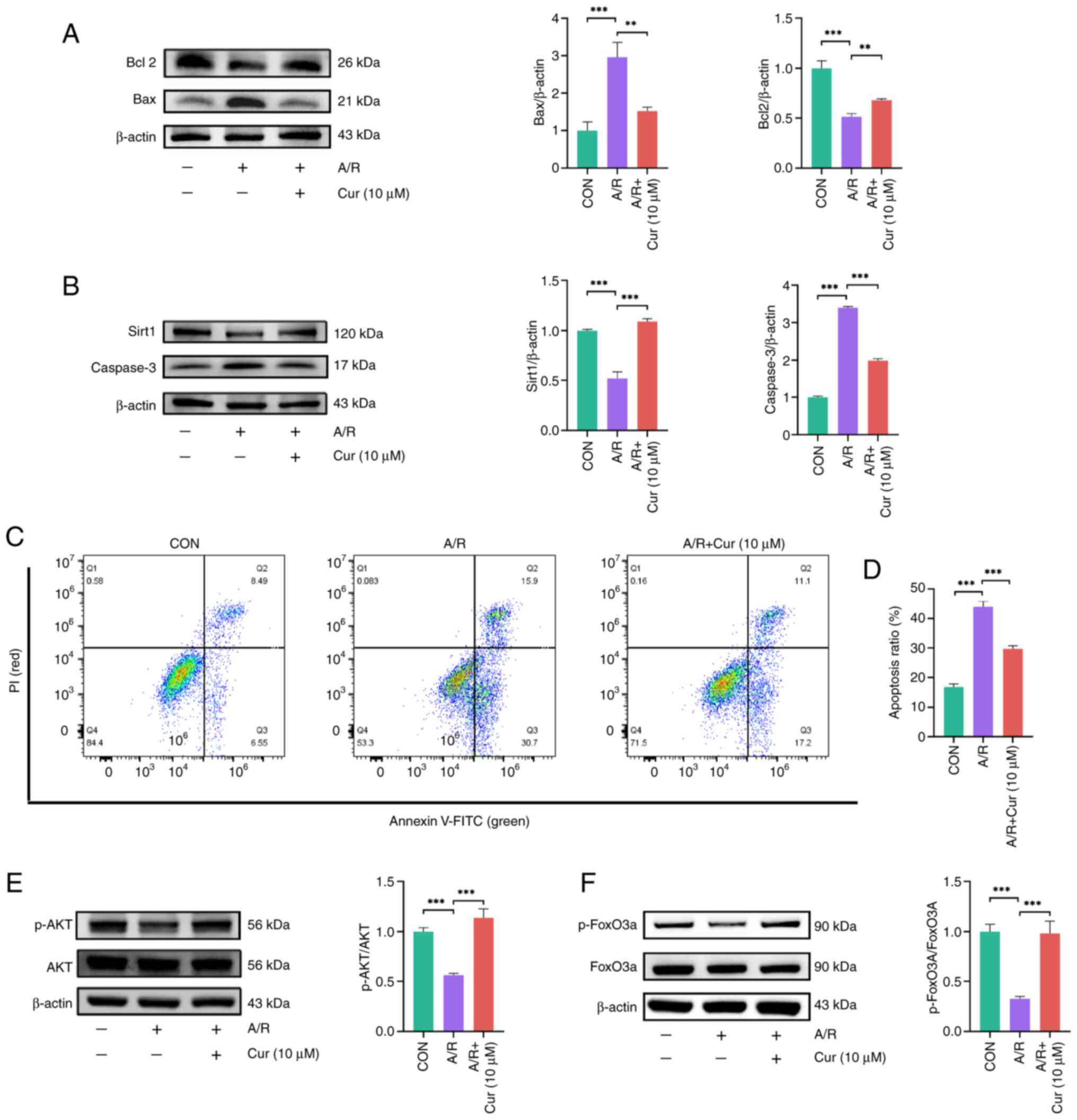

Cur attenuates A/R injury in H9c2 cells

via the Sirt1-based activation of Akt/FoxO3a

To assess the ability of Cur to attenuate A/R

injury, protein expression of Bcl-2, Bax and caspase 3, which are

apoptotic markers (37), and

that of Sirt1 were assessed in H9c2 cells. Caspase 3 and Bax

protein expression in the Cur group was lower than that in the A/R

group (Fig. 2A and B). By

contrast, Bcl-2 and Sirt1 protein expression was significantly

higher in Cur-pretreated than in A/R-treated H9c2 cells. These

results suggested that Cur attenuated A/R injury in H9c2 cells.

The detection of apoptosis in H9c2 cells was

performed via flow cytometry. The apoptosis rate of H9c2 cells in

the A/R group was significantly increased compared with the control

group. However, compared with A/R group, the apoptosis rate of H9c2

cells in the Cur group was significantly decreased (Fig. 2C and D). This finding indicated

that Cur pretreatment is an effective method for attenuating A/R

injury.

The AKT/FoxO3a signaling pathway is involved in the

regulation of autophagy and promotion of phagocytosis of abnormal

organelles and proteins (38).

Thus, the expression of AKT, p-AKT, FoxO3a and p-FoxO3a was

evaluated in cells. A/R injury decreased both p-AKT/AKT and

p-FoxO3a/FoxO3a ratios in H9c2 cells compared with the control

group. However, in the Cur groups, p-AKT/AKT and p-FoxO3a/FoxO3a

ratios were both increased (Fig.

2E-G). These results indicate that Cur decreased A/R injury in

H9c2 via the Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a pathway.

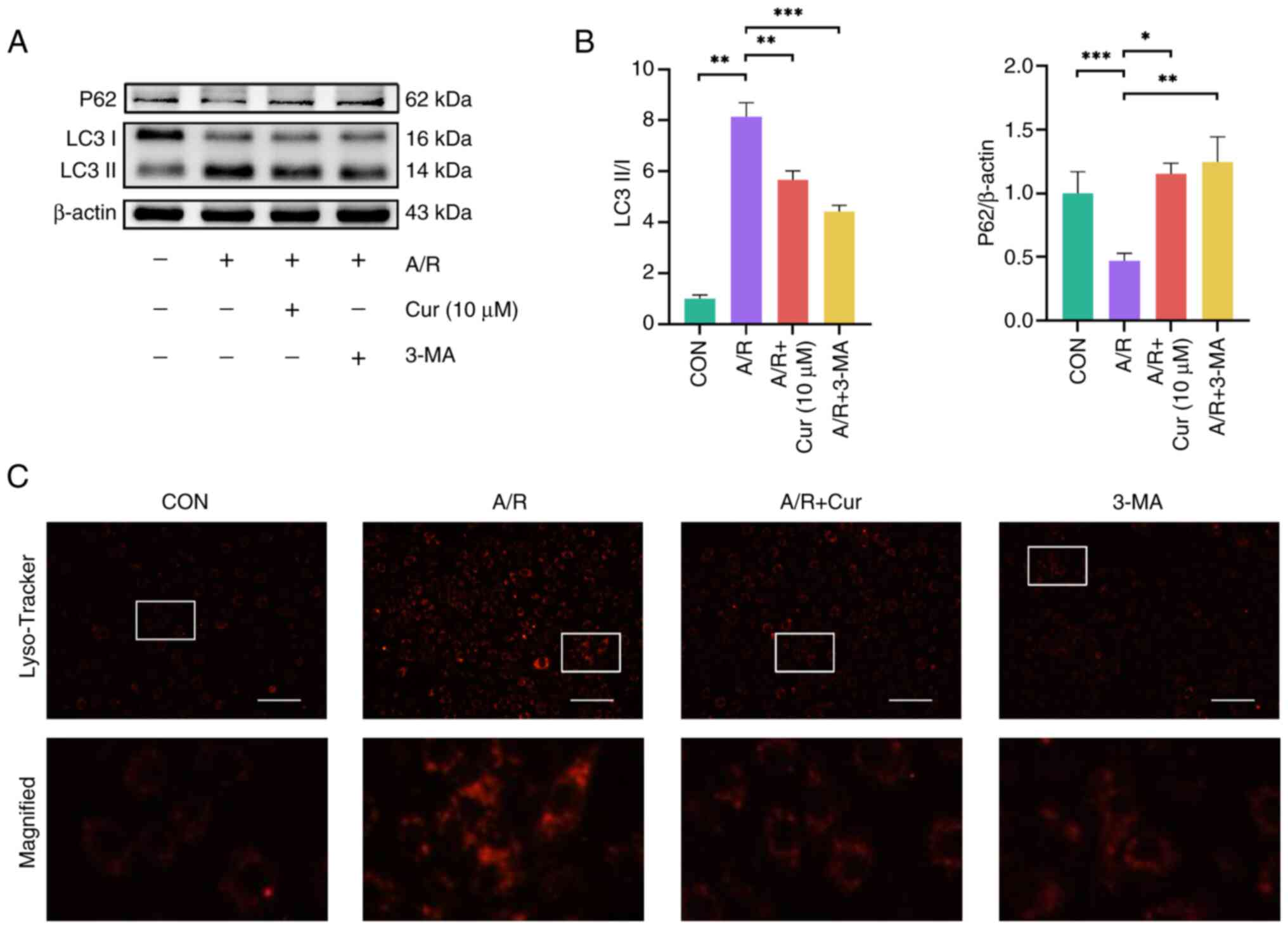

Cur inhibits excessive autophagy due to

A/R injury

A/R injury results in overactivation of

intracellular autophagy in H9c2 cells, which exacerbates myocardial

injury (9). Therefore, changes

in protein expression of autophagy markers LC3II and P62 were

analyzed (39). A/R injury

reduced P62 protein expression in H9c2 cells compared with the

control group, whereas Cur pretreatment of H9c2 cells reversed

these changes (Fig. 3A and B).

Likewise, P62 protein levels increased significantly in the 3-MA

+A/R compared with the A/R injury group. Consequently, LC3II/LC3I

protein ratio was higher in H9c2 cells from the AR group than in

cells from the control group. By contrast, LC3II/LC3I protein ratio

was reduced in the Cur and 3-MA group. LysoTracker Red was used to

identify the number of lysosomes in a cell (9). A/R injury increased intracellular

lysosomal fluorescence intensity compared with the control group,

suggesting A/R injury increases intracellular lysosomes. Cur or

3-MA could effectively attenuate the intracellular lysosomal

fluorescence intensity (Fig.

3C). These findings indicated that Cur pretreatment can prevent

excessive autophagic injury induced by A/R and avoid further damage

to H9c2 cells.

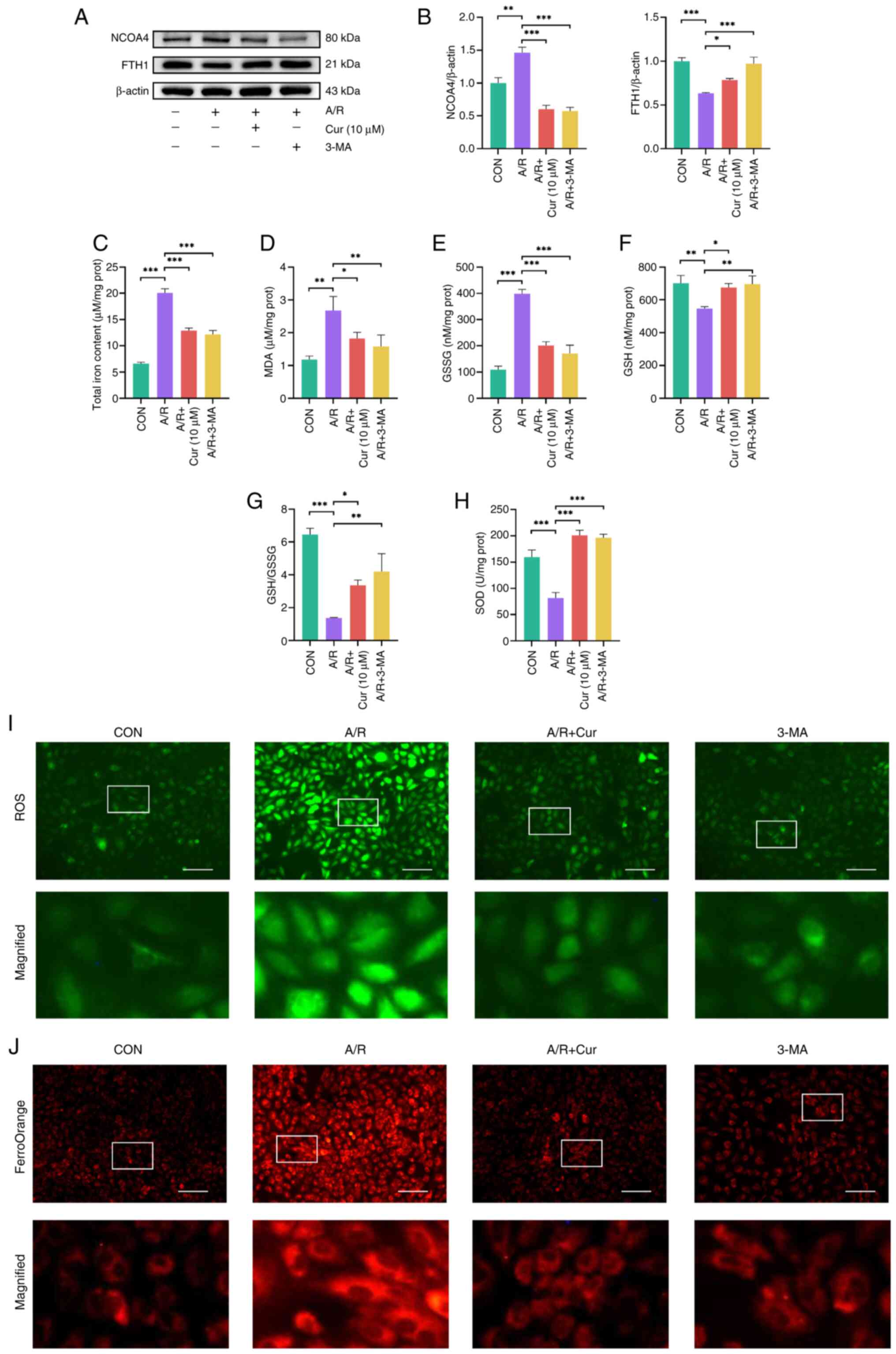

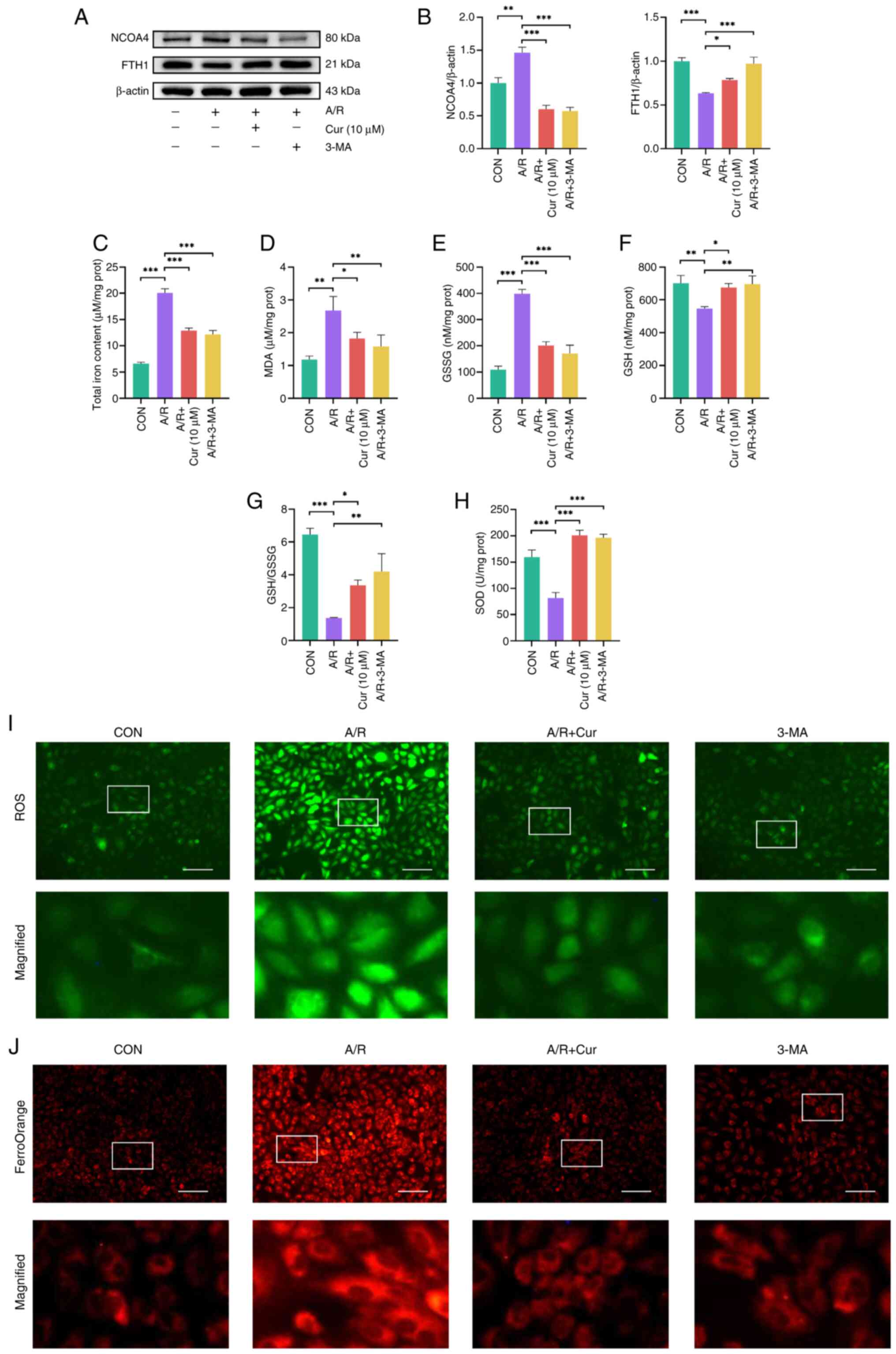

Cur attenuates autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis induced by A/R injury in H9c2 cells

There may be crosstalk between autophagy and

ferroptosis pathways during MIRI (24). Therefore, whether autophagy

inhibition attenuates ferroptosis was explored by analyzing changes

in the protein levels of NCOA4 and FTH1, which are markers of

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis (21). A/R injury increased NCOA4

expression and decreased FTH1 expression in H9c2 cells, whereas Cur

and 3-MA reversed these changes (Fig. 4A and B). The features of

ferroptosis include Fe2+ accumulation, lipid

peroxidation and ROS overload (19). Thus, intracellular MDA, SOD, GSH,

GSSG, and total iron ion levels were measured. A/R injury increased

the total iron, GSSG and MDA levels in H9c2 cells, whereas Cur and

3-MA reduced these levels significantly (Fig. 4C-E). By contrast, A/R injury

decreased intracellular SOD and GSH levels as well as GSSG/GSH

ratio compared with the control group. Cur or 3-MA increased

intracellular SOD and GSH levels as well as GSSG/GSH ratio

(Fig. 4F-H). Of note, ROS and

Fe2+ levels were higher in H9c2 cells following A/R

injury than in the control group and Cur or 3-MA attenuated ROS and

Fe2+ accumulation in H9c2 cells (Fig. 4I and J). These results suggest

that autophagy-dependent ferroptosis is involved in A/R injury and

that Cur and 3-MA pretreatment can attenuate autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis injury in H9c2 cells.

| Figure 4Cur attenuates autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis induced by A/R injury in H9c2 cells. (A) Expression of

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis-associated proteins (FTH1 and

NCOA4) was detected in A/R-injured H9c2 cells after Cur or 3-MA

treatment. (B) Relative protein expression of FTH1 and NCOA4.

Detection of (C) total iron ions, (D) MDA, (E) GSSG, (F) GSH, (G)

GSH/GSSG and (H) SOD in H9c2 cells with A/R injury by Cur or 3-MA

intervention. (I) ROS and (J) Fe2+ levels in H9c2 cells

following AR injury after Cur or 3-MA treatment (magnification,

×200; scale bar, 400 μm). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Cur, curcumin;

A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; FTH1, ferritin heavy chain 1; NCOA4,

nuclear receptor coactivator 4; 3-MA, 3-Methyladenine; MDA,

malondialdehyde; GSSG, glutathione disulfide; GSH, glutathione;

SOD, superoxide dismutase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; CON,

control; prot, protein. |

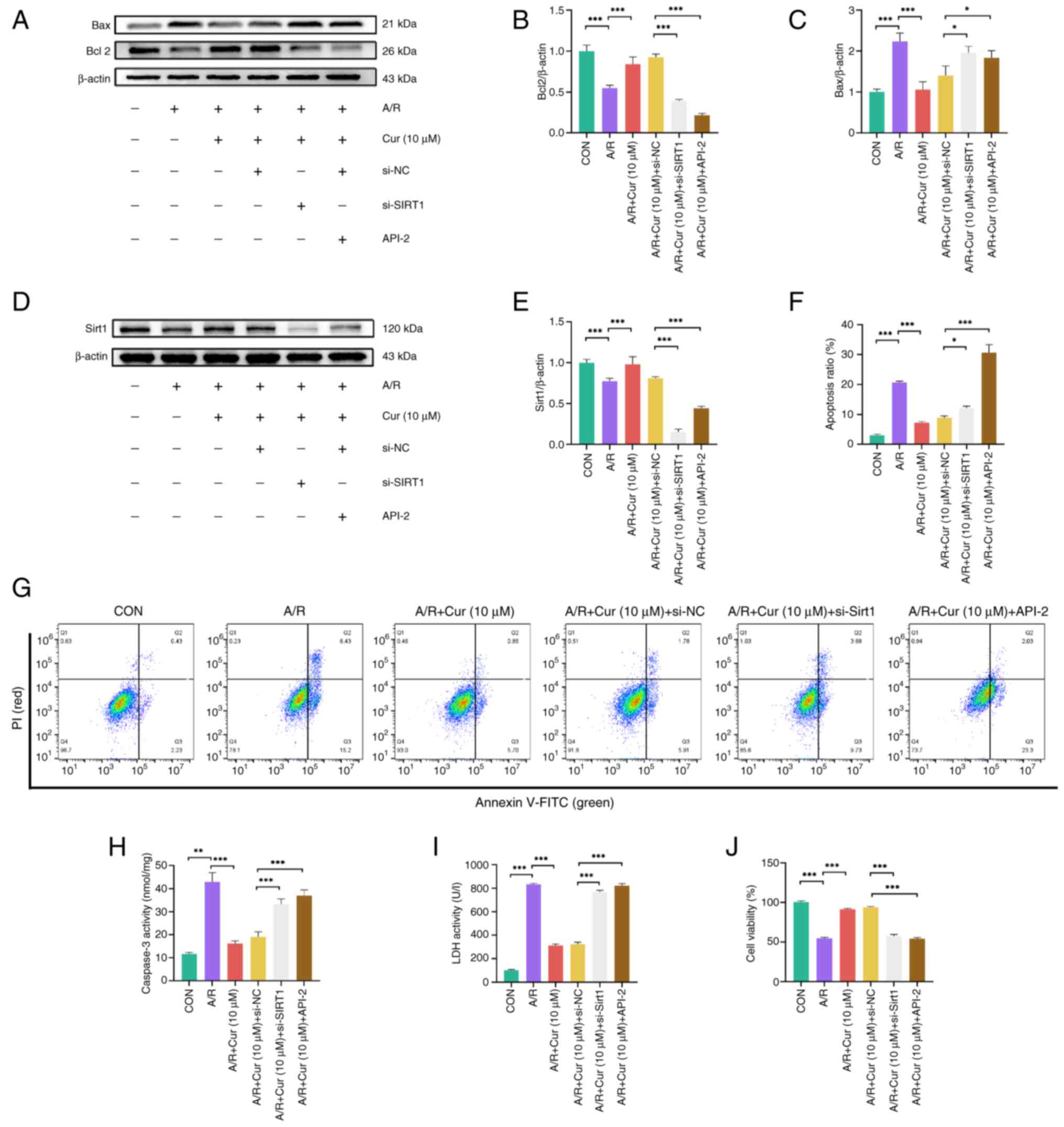

Cur attenuates A/R injury via Sirt1

Sirt1 influences many biological processes,

including apoptosis, senescence and mitochondrial biogenesis in

cardiomyocytes (40). Sirt1

deficiency may exacerbate MIRI and there may be crosstalk between

Sirt1 and AKT/FoxO3a (41).

Consequently, it was hypothesized that Cur decreases

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis in MIRI by modulating the

AKT/FoxO3a pathway via Sirt1. siRNAs were used to silence Sirt1.

First, the infection efficiency of siRNAs was verified at both the

protein and RNA levels in cells (Fig. S1); all siRNAs reduced the

protein and mRNA expression of Sirt1, but si-Sirt1-002 reduced

Sirt1 expression most significantly. si-Sirt1-002 was selected for

subsequent experiments. Next, molecular regulation experiments were

performed to verify whether Cur affects AKT/FoxO3a signaling and

decreases apoptosis via Sirt1. The results showed that A/R

treatment caused apoptosis in H9c2 cells and pretreatment with Cur

reduced apoptosis caused by A/R (Fig. 5A-C). Of note, silencing of Sirt1

in H9c2 cells or API-2 counteracted the protective effect of Cur,

suggesting that Cur exerted its protective effect through Sirt1 and

AKT (Fig. 5D and E).

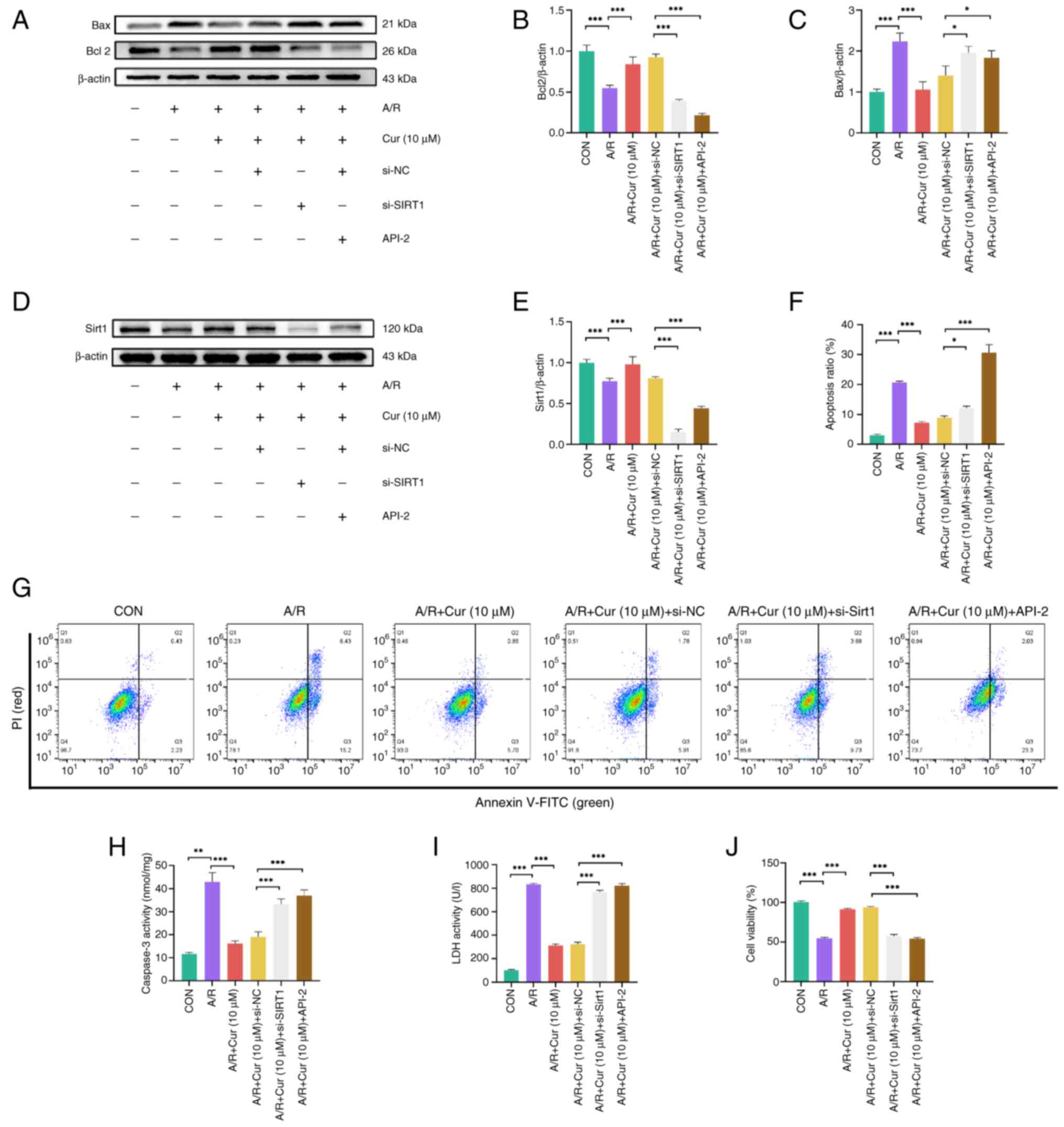

| Figure 5Cur decreases A/R injury in H9c2

cells via Sirt1. Expression of (A) apoptosis-associated proteins in

A/R-injured H9c2 cells following Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing

and targeted inhibition of AKT activity. (B) Relative protein

expression of Bcl2. (C) represents the relative protein expression

of Bax. Expression of Sirt1 (D) in A/R-injured H9c2 cells following

Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing and targeted inhibition of AKT

activity. (E) Relative protein expression of Sirt1. Apoptosis rate

of H9c2 cells was measured by flow cytometry (F and G) illustrates

the proportion of apoptotic cells as determined by flow cytometry.

(H) caspase 3, (I) LDH activity and (J) viability of A/R injured

H9c2 cells after Cur pretreatment, silencing of Sirt1 expression

and targeted inhibition of AKT activity. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Cur, curcumin;

A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; Sirt, silent information regulator 1;

LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; si, small interfering; NC,

non-targeting control; API-2, triciribine; CON, control. |

Flow cytometry demonstrated that A/R injury resulted

in elevated apoptosis rate in H9c2 cells and Cur effectively

reduced the apoptosis rate after A/R injury. si-Sirt1 increased the

apoptotic rate in H9c2 cells, thereby preventing the protective

effect of Cur (Fig. 5F and G).

A/R injury also increased caspase 3 activity in H9c2 cells, whereas

Cur effectively decreased caspase 3 activity. However, silencing of

Sirt1 protein expression or inhibition of AKT activity increased

caspase 3 activity in H9c2 cells (Fig. 5H). The same results were obtained

in CCK-8 and LDH activity assay; A/R resulted in release of LDH

from cells. The administration of Cur led to a reduction in LDH

levels. Furthermore, the silencing of Sirt1 protein expression or

the inhibition of Akt activity resulted in a stimulation of LDH

release (Fig. 5I); A/R injury

decreased H9c2 cell viability to ~50% of the control group.

However, the addition of Cur rescued cell viability, whereas

silencing of Sirt1 protein expression or inhibition of Akt activity

decreased viability (Fig. 5J).

These findings suggest that Cur attenuated A/R injury in H9c2 cells

through Sirt1.

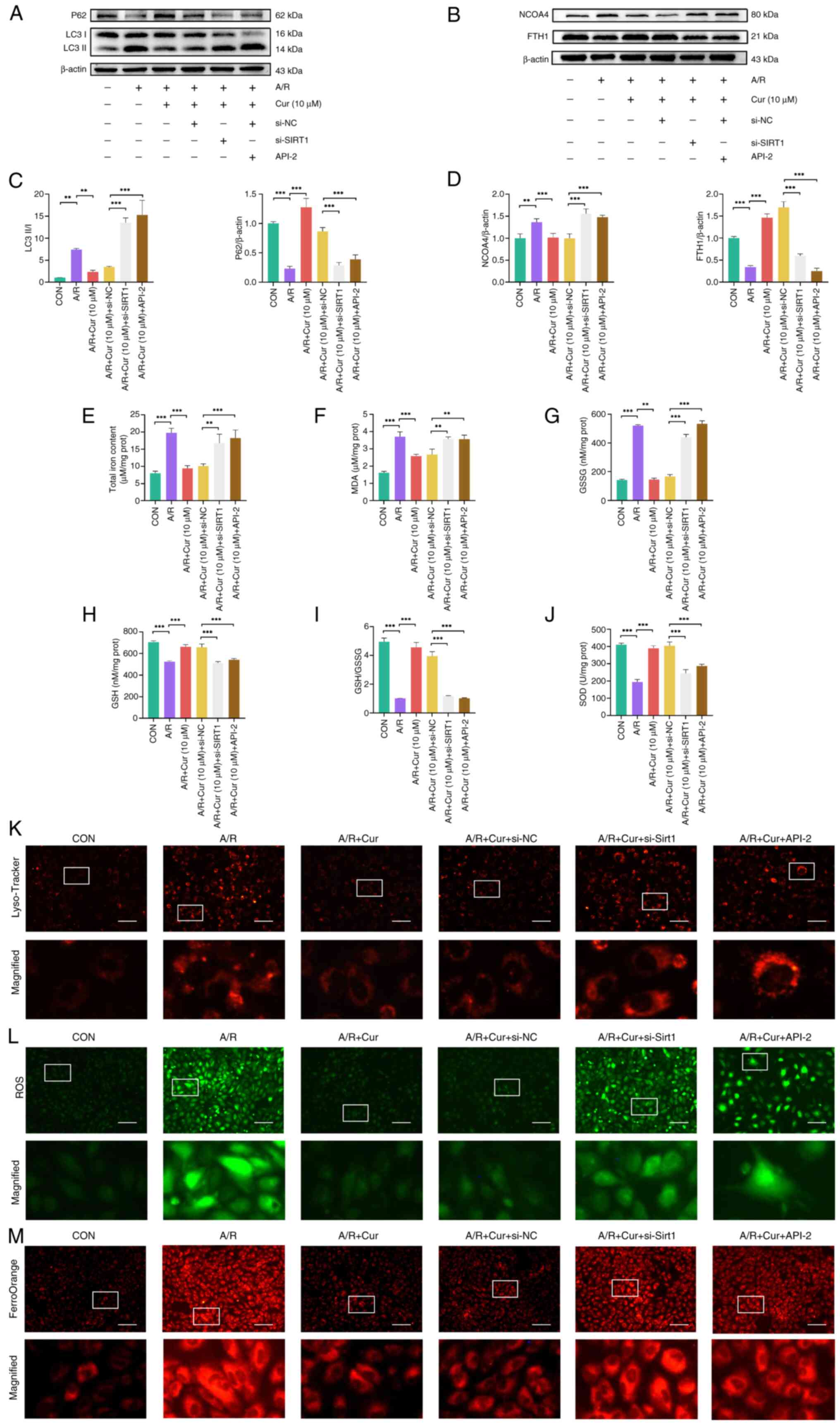

Cur decreases autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis via Sirt1 in H9c2 cells following A/R injury

To validate the ability of Cur to attenuate

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis via Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a in A/R-injured

H9c2 cells, changes in proteins associated with autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis injury were assessed. A/R injury led to an elevated

LC3II/I ratio as well as increased NCOA4 expression, whereas P62

and FTH1 protein expression decreased compared with the control

group. These changes were reversed in H9c2 cells pretreated with

Cur. Silencing of Sirt1 expression or cotreatment with API-2

effectively attenuated the protective effect of Cur. These results

indicated that Cur is effective in attenuating autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis in A/R. However, these effects were dependent on the

expression of Sirt1 and activity of AKT (Fig. 6A-D).

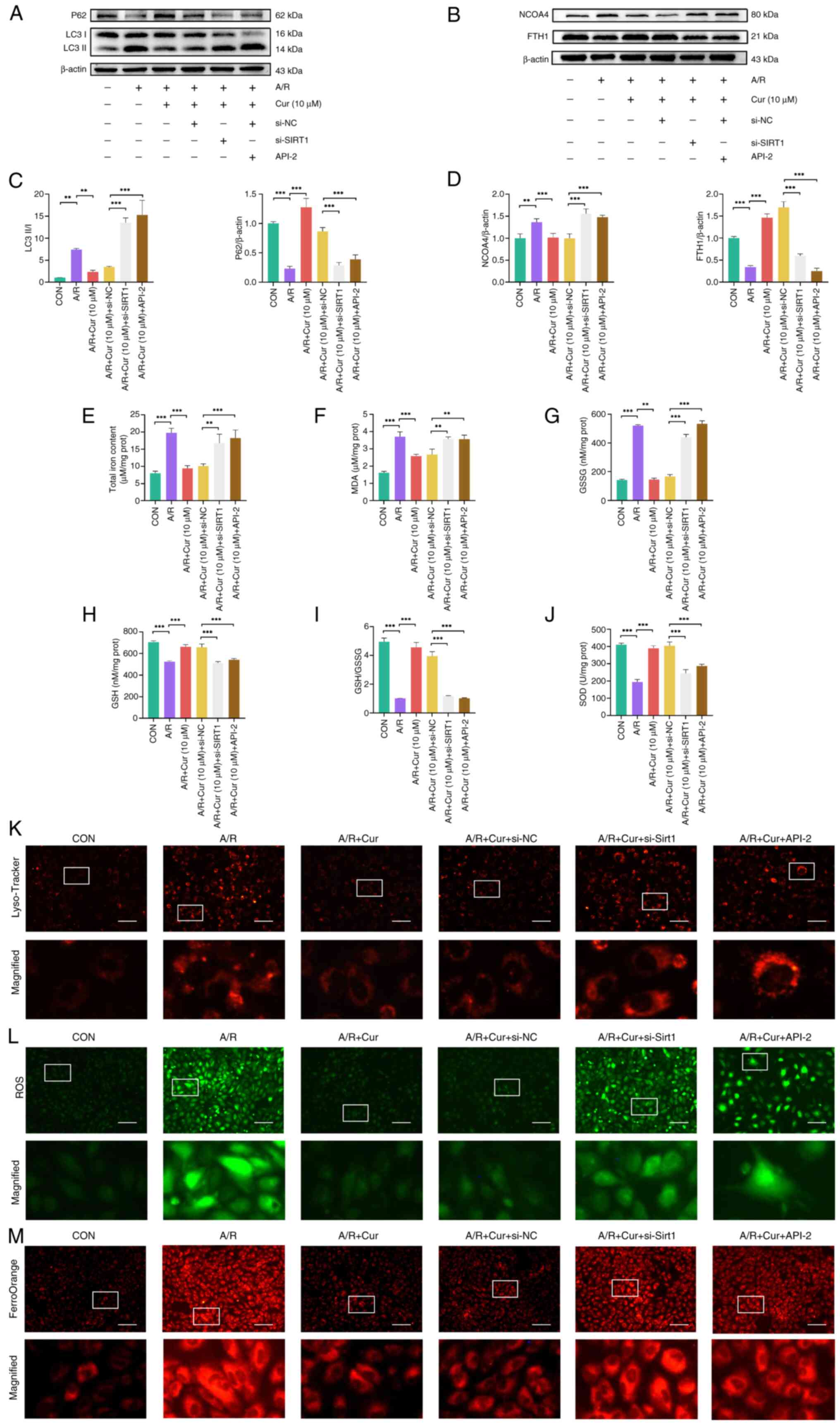

| Figure 6Cur reduces autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis in H9c2 cells associated with A/R injury via Sirt1.

Expression of autophagy-(A) and ferroptosis-related proteins (B) in

A/R-injured H9c2 cells following Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing

and targeted inhibition of AKT activity. (C) Relative protein

expression of P62 and the ratio of LC3II/I. (D) Relative protein

expression of NCOA4 and FTH1. Detection of (E) total iron ions, (F)

MDA, (G) GSSG, (H) GSH, (I) GSH/GSSG and (J) SOD in A/R injured

H9c2 cells following Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing and targeted

inhibition of AKT activity. Fluorescence intensity of (K)

lysosomes, (L) ROS and (M) Fe2+ in A/R-injured H9c2

cells following Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing and targeted

inhibition of AKT activity (magnification, ×200; scale bar, 400

μm). **P<0.05, ***P<0.01. Cur,

curcumin; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; Sirt, silent information

regulator 1; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSSG, glutathione disulfide;

GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; ROS, reactive oxygen

species; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; FTH1, ferritin

heavy chain 1; CON, control; si, small interfering; prot, protein;

API, triciribine; LC3II, microtubule-associated protein 1 light

chain 3 β; NC, non-targeting control. |

To validate whether Cur can attenuate

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis via Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a in A/R-injured

H9c2 cells, ferroptosis- and autophagy-related biochemical indices

were compared (Fig. 6E-J). The

results revealed that A/R injury increased total iron ion, MDA and

GSSG levels and decreased GSH and SOD levels as well as the

GSH/GSSG ratio relative to the control group. These changes were

reversed in H9c2 cells pretreated with Cur. By contrast, silencing

of Sirt1 expression or API-2 cotreatment led to a weakened

protective effect of Cur, increased total iron ion, MDA, and GSSG

levels and decreased GSH and SOD levels as well as the GSH/GSSG

ratio in H9c2 cells. LysoTracker Red, DCFH-DA and

FerroOrangeTracker staining (Fig.

6K-M) showed that autophagic lysosomes, ROS, and

Fe2+ in H9c2 cells were increased following A/R injury.

However, Cur pretreatment decreased levels of autophagic lysosomes,

ROS and Fe2+ relative to the A/R injury group.

Fluorescence intensity of ROS and Fe2+ was significantly

enhanced following the addition of si-Sirt1 or API-2. These results

indicate that Cur attenuates autophagy-dependent ferroptosis

induced by A/R.

Cur mediates nuclear localization of

FoxO3a via Sirt1/Akt

FoxO3a is retained in the cytoplasm following

phosphorylation by Akt, which inhibits the transcription of the

target genes of FoxO3a (42).

Previous studies have shown that FoxO3a may regulate autophagy

levels by regulating genes such as LC3II, γ-aminobutyric acid

receptor-associated protein-like 1 (Gabarapl1) and autophagy

related 12 homolog (ATG12) (27,43). To demonstrate that FoxO3a is a

key gene for adaptive autophagy in A/R injury, the phosphorylation

of AKT and FoxO3a and the distribution of FoxO3a proteins were

analyzed. Western blotting showed that A/R injury decreased the

phosphorylation of AKT and FoxO3a compared with the control group

and expression of FoxO3a was significantly increased in nuclear

extracts of H9c2 cells but decreased in the cytoplasmic extracts.

Cur pretreatment increased phosphorylation levels of AKT and FoxO3a

compared with the A/R group. Expression of FoxO3a was significantly

decreased in nuclear extract of H9c2 cells and significantly

increased in the cytoplasmic extract in the Cur group compared with

the A/R group. si-Sirt1 or API-2 with Cur pretreatment restored

phosphorylation levels of AKT and FoxO3a to those of the A/R group.

Expression of FoxO3a in the nuclear extracts of H9c2 cells in the

si-Sirt1 and API-2 groups also increased to that of the A/R group.

By contrast, there was a decrease in the expression of FoxO3a in

the cytoplasm of H9c2 cells (Fig.

7A-D). These results indicated that Cur regulated the

phosphorylation of AKT through Sirt1, which subsequently regulated

phosphorylation of FoxO3a and affected the localization of FoxO3a

in H9c2 cells.

| Figure 7Cur mediates nuclear localization of

FoxO3a via Sirt1/AKT. (A) Western blot analysis of (B)

phosphorylation of AKT and FoxO3a in A/R-injured H9c2 cells after

Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing and targeted inhibition of AKT

activity. (C) Western blot analysis of (D) distribution of FoxO3a

in the cytoplasm and nucleus of A/R-injured H9c2 cells following

Cur pretreatment, Sirt1 silencing and targeted inhibition of AKT

activity. ***P<0.01. Cur, curcumin; PCNA,

proliferating cell nuclear antigen; Sirt, silent information

regulator 1; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; p-, phosphorylated; si,

small interfering; NC, non-targeting control; API, Triciribine;

CON, control. |

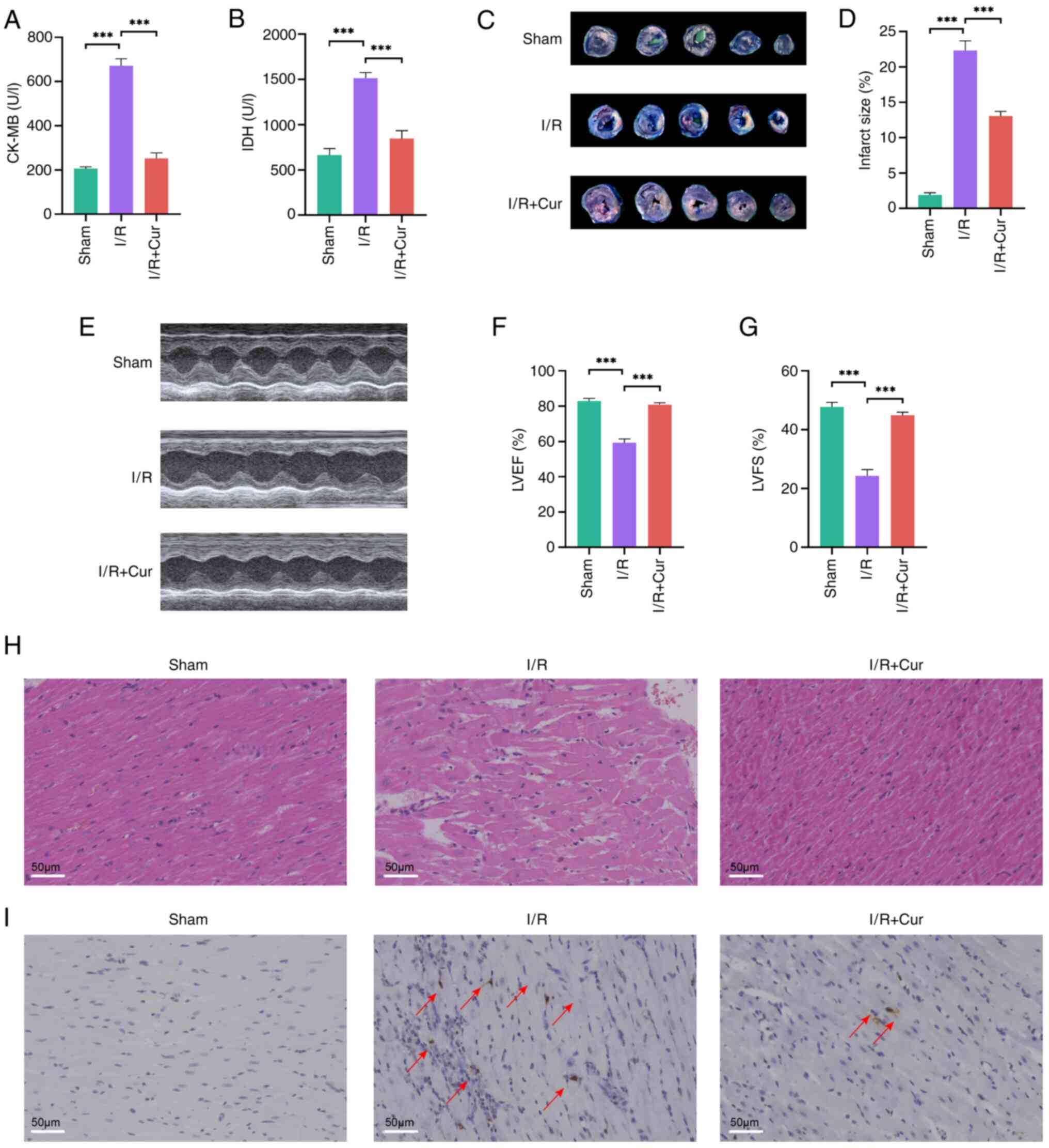

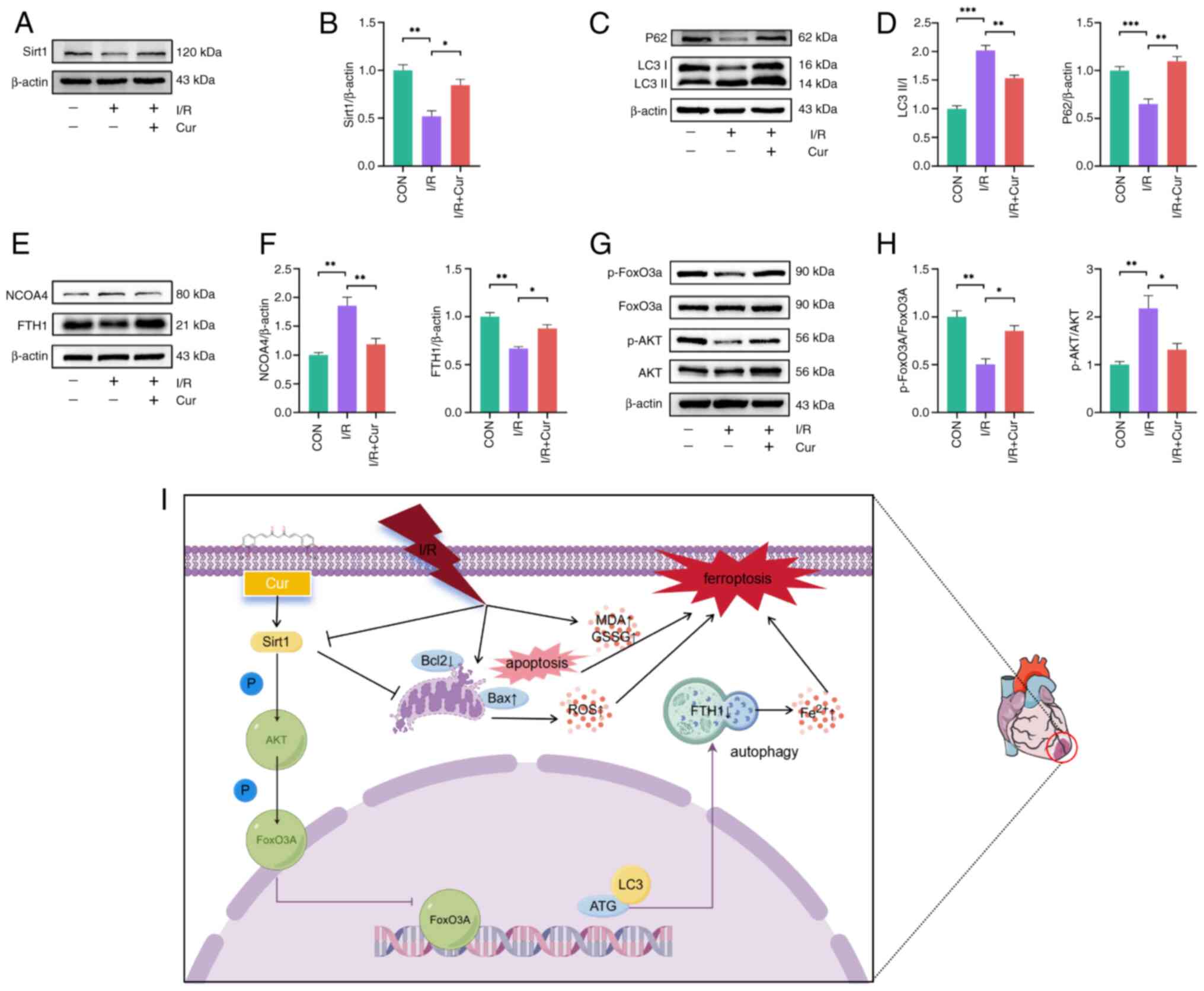

Cur protects cardiomyocytes from MIRI via

Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a signaling

I/R model in the rat heart was established to

confirm the protective effect of Cur against MIRI. CK-MB and LDH

(myocardial injury marker enzymes) (13) levels were significantly elevated

in the serum samples of I/R-injured rats and Cur effectively

restored these abnormal enzymatic indices (Fig. 8A and B). Evans blue and TTC

staining revealed MI area was significantly increased in

I/R-injured rats compared with that in the sham group, whereas Cur

pretreatment significantly decreased the infarct area after MIRI

(Fig. 8C and D).

Echocardiography assessment of left ventricle function in rats

showed that MIRI impaired cardiac function by decreasing LVEF and

LVFS. Cur was effective in restoring these abnormal functions

(Fig. 8E-G). HE staining showed

that the myocardium exhibited myofiber separation, cardiomyocyte

swelling and interstitial cell hypertrophy and TUNEL staining

revealed an increase in TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes following

MIRI. However, Cur pretreatment eliminated these MIRI-induced

morphological changes in myocardial tissue (Fig. 8H and I).

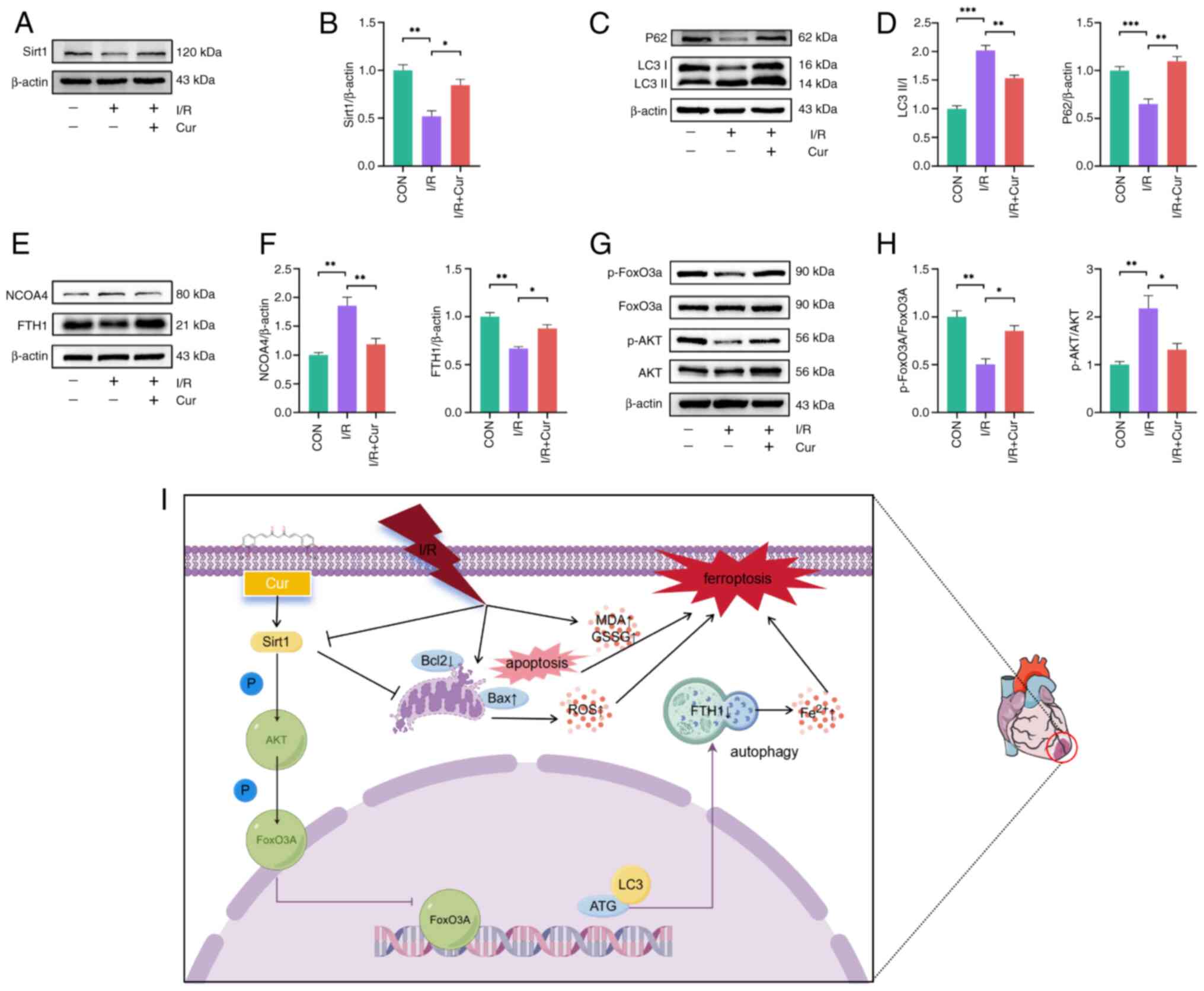

The protein expression of Sirt1, LC3II, P62, NCOA4

and FTH1 and the ratios of p-AKT/AKT and p-FoxO3a/FoxO3a in rat

myocardium were assessed to validate the molecular mechanism of Cur

(Fig. 9A-H). I/R decreased the

expression of Sirt1 in cardiomyocytes, whereas Cur-pretreated rats

did not exhibit a decrease in expression of Sirt1 after I/R, which

suggested that Cur can activate Sirt1 in cardiomyocytes to

attenuate MIRI (Fig. 9A and B).

I/R increased the ratio of LC3II/LC3Ⅰ and expression of NCOA4 in

rat cardiomyocytes, with a corresponding decrease in expression of

P62 and FTH1, which indicated that I/R induced autophagy-dependent

ferroptosis in rat cardiomyocytes and Cur pretreatment eliminated

these effects (Fig. 9C-F). p-AKT

and p-FoxO3a levels showed a decreasing trend after I/R, whereas

Cur increased p-AKT and p-FoxO3a levels in the rat myocardium

(Fig. 9G and H). These results

indicated that Cur attenuated MIRI by regulating

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis via Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a signaling

(Fig. 9I).

| Figure 9Potential mechanism of action of Cur

in MIRI. (A) Western blot was performed to detect protein

expression of Sirt1 in MIRI heart tissues after Cur treatment, (B)

Relative protein expression of Sirt1. Western blot was performed to

detect protein expression of LC3II and P62 (C) in MIRI heart

tissues after Cur treatment, (D represents the relative protein

expression of P62 and the ratio of LC3II/I. Western blot was

performed to detect protein expression of NCOA4 and FTH1 (E) in

MIRI heart tissues after Cur treatment, (F) represents the relative

protein expression of NCOA4 and FTH1. Western blot was performed to

detect the ratios of p-AKT/AKT and p-FoxO3a/FoxO3a (G) in MIRI

heart tissues after Cur treatment, (H) showed statistical figures.

(I) Cur inhibits MIRI-induced autophagy-dependent ferroptosis and

apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a, which increases

cardiomyocyte survival and maintains cardiac function. Part of the

figure was created using Figdraw (https://www.figdraw.com). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01, ***P<0.001. Cur, curcumin;

MIRI, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury; Sirt, silent

information regulator 1; LC3II, microtubule-associated protein 1

light chain 3 beta; NCOA4, nuclear receptor coactivator 4; FTH1,

ferritin heavy chain 1; p-, phosphorylation; I/R,

ischemia/reperfusion; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide

dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione; GSSG,

glutathione disulfide; A/R, anoxia/reoxygenation; ATG, autophagy

related gene. |

Discussion

MIRI, a notable complication with poor prognosis

among patients with cardiac disorder, causes irreversible damage to

the heart (44). Therefore, it

is key to understand molecular mechanisms underlying MIRI and

investigate the potential of effective therapeutic agents in

mitigating MIRI. Ferroptosis process is iron-dependent and involves

enhanced accumulation of ROS and impairment of the GSH-dependent

antioxidant system, which are the primary causes of IRI (19). Cur exhibits potent modulatory

activity on multiple signaling pathways associated with

inflammation and oxidative stress (45). Consequently, Cur may be a

promising candidate compound for MIRI attenuation (46). The present study provided

insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying the protective

role of Cur in MIRI. MIRI induced autophagy-dependent ferroptosis

and apoptosis. In addition, Cur modulated Sirt1 to attenuate

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes.

Modulation of Sirt1 demonstrated that Sirt1 regulated the

phosphorylation level of AKT and FoxO3a, which localized FoxO3a in

the cytoplasm and blocked its entry into the nucleus to prevent

initiation of transcription. In turn, reduced translation decreased

expression of autophagy and ferroptosis biomarkers, thereby

protecting cardiomyocyte function. These findings elucidated the

molecular mechanisms by which Cur attenuates MIRI, offering novel

insights and avenues for future therapeutic strategies for

MIRI.

In addition to traditional treatment options for

cardiovascular disease, a growing body of research has suggested

that functional food compounds treat cardiovascular disease via

their effect on the epigenome (13,47-49). Cur is a bioactive component of

turmeric that exerts multiple protective effects on the

cardiovascular system, and its pleiotropic effects in

cardiovascular disease have been studied extensively to establish

it as a potential candidate for the treatment of MI (17,46). Cur attenuates MIRI by modulating

redox dysregulation; however, Cur also modulates downstream protein

activity and expression to attenuate MIRI (50,51). Duan et al (17) showed that Cur activates the

JAK2/STAT3 pathway and decreases oxidative damage, which in turn

inhibits MIRI. In addition, Kim et al (52) suggested that Cur modulates the

toll-like receptor 2/NF-κB pathway to attenuate MIRI. The present

study revealed that Cur effectively reduced serum LDH and CK-MB

levels after MIRI and changes in histopathology and myocardial

apoptosis after MIRI were notably suppressed. Of note, both in

vivo and in vitro experiments showed that IRI or A/R

injury decreased Sirt1 protein expression in cardiomyocytes,

whereas Cur effectively increased Sirt1 protein expression,

improved cardiomyocyte viability and decreased apoptosis. Further

studies should determine whether Sirt1 activates the downstream

pathway proteins to regulate cardiomyocyte phenotype.

Ferroptosis is an iron ion-dependent mode of cell

death in which stress conditions decrease the antioxidant capacity

of the cell, causing ROS accumulation, peroxidation and ultimately

cell death (26). Autophagy is a

conserved cell survival mechanism that maintains cell function and

morphology by removing damaged organelles or proteins; however,

uncontrolled autophagy can cause cell death (9,53). Autophagy is an upstream mechanism

of ferroptosis that promotes iron oxidation by regulating

intracellular iron metabolism and ROS production (54-56). Ferroptosis occurs predominantly

during the reperfusion phase in the myocardium, as intracellular

iron overload occurs only when myocardial blood flow is restored

(57). This leads to

accumulation of intracellular Fe2+ and ROS, resulting in

cardiomyocyte dysfunction (19).

Excessive autophagy also occurs in cardiomyocytes at this stage

(9). Consequently, it was

hypothesized that autophagy-dependent ferroptosis is involved in

MIRI. In the present study, 3-MA (autophagy inhibitor) was used to

inhibit excessive autophagy in cardiomyocytes, leading to an

increase in FTH (a protein that stores iron and serves a key role

in maintaining intracellular iron homeostasis) (55) and decrease in NCOA4 (a specific

mediator of ferritin phagocytosis that selectively degrades

ferritin) (58). This indicates

that autophagy-dependent ferroptosis occurs during MIRI. Cur

pretreatment effectively inhibited ferroptosis induced by excessive

autophagy during MIRI, although the molecular mechanisms were not

fully investigated. Based on the present results, it is reasonable

to speculate that Cur further attenuates MIRI-induced

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis via Sirt1-based activation of

downstream pathways.

Sirt1 is a member of the NAD-dependent histone

deacetylases (59). Sirt1 exerts

a protective effect in various models of cardiovascular oxidative

stress and mitigate doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through the

regulation of H2A histone family member X (60,61). In addition, there is evidence

suggesting its involvement in other processes, such as

cardiomyocyte apoptosis, autophagy, oxidative stress, cellular

senescence and metabolic regulation (62). These findings are consistent with

the present results, which demonstrated that increased expression

of Sirt1 by Cur was accompanied by decreased cell death, autophagy

and ferroptosis. However, silencing of Sirt1 expression resulted in

a decreased protective effect of Cur, indicating that the

protective effect of Cur was dependent on Sirt1. Sirt1 has been

shown to mediate the activity of several key cellular proteins

(AMPK, Bcl2, and Nrf2) associated with cardioprotection in addition

to deacetylating lysine residues in histones for epigenetic

regulation (63-65). AKT regulates the activity of

several targets, including the pro-apoptotic protein Bad, caspase 9

and members of the FoxO transcription factor/protein family (FoxO1,

FoxO3a and FoxO4) (42). The

present study results indicated that Cur is an effective activator

of the phosphorylation of AKT and FoxO3a. However, phosphorylation

level of AKT and FoxO3a was reduced following the intervention of

si-Sirt1. Cur failed to induce FoxO3a phosphorylation after AKT

phosphorylation was blocked, which indicated that Cur activated AKT

phosphorylation via Sirt1, followed by the subsequent activation of

FoxO3a phosphorylation by AKT. Previous studies have shown that the

AKT-induced phosphorylation of FoxO proteins leads to their nuclear

export, localizing FoxO in the cytoplasm (42,66). This is in line with the present

results. Nucleoplasm separation experiments showed that A/R injury

retained FoxO3a in the nucleus and Cur impaired this effect.

However, after inhibiting Sirt1 protein expression, FoxO3a was

translocated from cytoplasm to the nucleus; the blockade of AKT

activity also promoted FoxO3a translocation to the nucleus. FoxO3a

entry into the nucleus during MIRI stimulates translation of

autophagy-associated proteins (LC3, Gabarapl1 and ATG12), which

impairs mitochondrial metabolism, promotes apoptosis and

exacerbates ischemic injury in cardiomyocytes (27). The present study revealed that

autophagy and ferroptosis levels were increased and viability

decreased in H9c2 cells after the A/R-promoted FoxO3a entry into

the nucleus. By contrast, apoptosis rate, number of autophagic

lysosomes and accumulation of intracellular ROS and Fe2+

decreased in H9c2 cells after Cur retained FoxO3a in the cytoplasm.

These results indicated that Cur attenuates both apoptosis and

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis induced by A/R injury in H9c2 cells

via the Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a pathway. As post-translational

modification alters subcellular localization of FoxO3a and its

functional release (40), it is

unclear whether phosphorylation or acetylation exerts a greater

effect on nuclear translocation of FoxO3a. It is unclear whether

target genes of FoxO3a directly affect ferroptosis.

Taken together, the present study showed that

MIRI-induced excessive autophagy caused intracellular iron ion

accumulation, which promoted ferroptosis and impaired cardiac

function. By contrast, Cur inhibited MIRI-induced

autophagy-dependent ferroptosis and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via

Sirt1/AKT/FoxO3a, thereby increasing cardiomyocyte survival and

maintaining cardiac function. These findings provide novel

perspectives to understand autophagy-dependent ferroptosis during

MIRI.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

STZ, ZCQ and ZQX performed experiments, analyzed

data and wrote the manuscript. LFZ and HZP performed experiments

and analyzed data. RBQ and EDT analyzed and interpreted data. SQL

and LW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. SQL and LW

designed the experiments. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present research protocol was reviewed and

approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital

of Nanchang University (approval no. CDYFY-IACUC-202211QR010).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by National Nature Science

Foundation of China (grant nos. 82460057 and 82160073) and Jiangxi

Provincial Natural Science Foundation (grant nos. 20212ACB206011,

20224ACB206002 and 20232BAB206009).

References

|

1

|

Abdollahi E, Momtazi AA, Johnston TP and

Sahebkar A: Therapeutic effects of curcumin in inflammatory and

immune-mediated diseases: A nature-made jack-of-all-trades? J Cell

Physiol. 233:830–848. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Xie W, Gan J, Zhou X, Tian H, Pan X, Liu

W, Li X, Du J, Xu A, Zheng M, et al: Myocardial infarction

accelerates the progression of MASH by triggering

immunoinflammatory response and induction of periosti. Cell Metab.

36:1269–1286.e9. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shen H, Yao Z, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Yao C and

Tong C: miR-21 enhances the protective effect of loperamide on rat

cardiomyocytes against hypoxia/reoxygenation, reactive oxygen

species production and apoptosis via regulating Akap8 and Bard1

expression. Exp Ther Med. 17:1312–1320. 2019.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang Z, Yao M, Jiang L, Wang L, Yang Y,

Wang Q, Qian X, Zhao Y and Qian J: Dexmedetomidine attenuates

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-induced ferroptosis via

AMPK/GSK-3β/Nrf2 axis. Biomed Pharmacother. 154:1135722022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hausenloy DJ, Garcia-Dorado D, Bøtker HE,

Davidson SM, Downey J, Engel FB, Jennings R, Lecour S, Leor J,

Madonna R, et al: Novel targets and future strategies for acute

cardioprotection: Position paper of the european society of

cardiology working group on cellular biology of the heart.

Cardiovasc Res. 113:564–585. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Davidson SM, Ferdinandy P, Andreadou I,

Bøtker HE, Heusch G, Ibáñez B, Ovize M, Schulz R, Yellon DM,

Hausenloy DJ, et al: Multitarget strategies to reduce myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury: JACC review topic of the week. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 73:89–99. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhao GL, Yu LM, Gao WL, Duan WX, Jiang B,

Liu XD, Zhang B, Liu ZH, Zhai ME, Jin ZX, et al: Berberine protects

rat heart from ischemia/reperfusion injury via activating

JAK2/STAT3 signaling and attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress.

Acta Pharmacol Sin. 37:354–367. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yao M, Wang Z, Jiang L, Wang L, Yang Y,

Wang Q, Qian X, Zeng W, Yang W, Liang R and Qian J: Oxytocin

ameliorates high glucose- and ischemia/reperfusion-induced

myocardial injury by suppressing pyroptosis via AMPK signaling

pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 153:1134982022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Wen L, Cheng X, Fan Q, Chen Z, Luo Z, Xu

T, He M and He H: TanshinoneIIA inhibits excessive autophagy and

protects myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury via

14-3-3η/Akt/Beclin1 pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 954:1758652023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Anand P, Thomas SG, Kunnumakkara AB,

Sundaram C, Harikumar KB, Sung B, Tharakan ST, Misra K,

Priyadarsini IK, Rajasekharan KN and Aggarwal BB: Biological

activities of curcumin and its analogues (Congeners) made by man

and mother nature. Biochem Pharmacol. 76:1590–1611. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Aggarwal BB, Sundaram C, Malani N and

Ichikawa H: Curcumin: The Indian solid gold. Adv Exp Med Biol.

595:1–75. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kumar G, Mittal S, Sak K and Tuli HS:

Molecular mechanisms underlying chemopreventive potential of

curcumin: Current challenges and future perspectives. Life Sci.

148:313–328. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

He H, Luo Y, Qiao Y, Zhang Z, Yin D, Yao

J, You J and He M: Curcumin attenuates doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity via suppressing oxidative stress and preventing

mitochondrial dysfunction mediated by 14-3-3γ. Food Funct.

9:4404–4418. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jiang C, Shi Q, Yang J, Ren H, Zhang L,

Chen S, Si J, Liu Y, Sha D, Xu B and Ni J: Ceria nanozyme

coordination with curcumin for treatment of sepsis-induced cardiac

injury by inhibiting ferroptosis and inflammation. J Adv Res.

63:159–170. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

15

|

El-Far AH, Elewa YHA, Abdelfattah EZA,

Alsenosy AWA, Atta MS, Abou-Zeid KM, Al Jaouni SK, Mousa SA and

Noreldin AE: Thymoquinone and curcumin defeat aging-associated

oxidative alterations induced by D-galactose in rats' brain and

heart. Int J Mol Sci. 22:68392021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hong D, Zeng X, Xu W, Ma J, Tong Y and

Chen Y: Altered profiles of gene expression in curcumin-treated

rats with experimentally induced myocardial infarction. Pharmacol

Res. 61:142–148. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Duan W, Yang Y, Yan J, Yu S, Liu J, Zhou

J, Zhang J, Jin Z and Yi D: The effects of curcumin post-treatment

against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion by activation of the

JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Basic Res Cardiol. 107:2632012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kang JY, Kim H, Mun D, Yun N and Joung B:

Co-delivery of curcumin and miRNA-144-3p using heart-targeted

extracellular vesicles enhances the therapeutic efficacy for

myocardial infarction. J Control Release. 331:62–73. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Jiang X, Stockwell BR and Conrad M:

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 22:266–282. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yang B, Xu Y, Yu J, Wang Q, Fan Q, Zhao X,

Qiao Y, Zhang Z, Zhou Q, Yin D, et al: Salidroside pretreatment

alleviates ferroptosis induced by myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

through mitochondrial superoxide-dependent AMPKα2 activation.

Phytomedicine. 128:1553652024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Fang X, Ardehali H, Min J and Wang F: The

molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in

cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:7–23. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Chen YR and Zweier JL: Cardiac

mitochondria and reactive oxygen species generation. Circ Res.

114:524–537. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pasricha SR, Tye-Din J, Muckenthaler MU

and Swinkels DW: Iron deficiency. Lancet. 397:233–248. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Fang X, Wang H, Han D, Xie E, Yang X, Wei

J, Gu S, Gao F, Zhu N, Yin X, et al: Ferroptosis as a target for

protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

116:2672–2680. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kremastinos DT and Farmakis D: Iron

overload cardiomyopathy in clinical practice. Circulation.

124:2253–2263. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kim CH and Leitch HA: Iron

overload-induced oxidative stress in myelodysplastic syndromes and

its cellular sequelae. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 163:1033672021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Wang C, Xu W, Zhang Y, Zhang F and Huang

K: PARP1 promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes via modulating FoxO3a

transcription. Cell Death Dis. 9:10472018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

D'Onofrio N, Servillo L and Balestrieri

ML: SIRT1 and SIRT6 signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease

protection. Antioxid Redox Signal. 28:711–732. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Karbasforooshan H and Karimi G: The role

of SIRT1 in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biomed Pharmacother.

90:386–392. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Verdin E: The many faces of sirtuins:

Coupling of NAD metabolism, sirtuins and lifespan. Nat Med.

20:25–27. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Li W, Du D, Wang H, Liu Y, Lai X, Jiang F,

Chen D, Zhang Y, Zong J and Li Y: Silent information regulator 1

(SIRT1) promotes the migration and proliferation of endothelial

progenitor cells through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. Int J

Clin Exp Pathol. 8:2274–2287. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

National Research Council Committee for

the Update of the Guide for the C and Use of Laboratory A: The

National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National

Institutes of Health. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals. National Academies Press; US: Copyright © 2011, National

Academy of Sciences, Washington (DC). 2011

|

|

33

|

Nolen RS: New AVMA guidelines aim to limit

animal suffering in emergencies. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 254:1242–1243.

2019.

|

|

34

|

He H, Wang L, Qiao Y, Yang B, Yin D and He

M: Epigallocatechin-3-gallate pretreatment alleviates

doxorubicin-induced ferroptosis and cardiotoxicity by upregulating

AMPKα2 and activating adaptive autophagy. Redox Biol.

48:1021852021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhao ST, Qiu ZC, Zeng RY, Zou HX, Qiu RB,

Peng HZ, Zhou LF, Xu ZQ, Lai SQ and Wan L: Exploring the molecular

biology of ischemic cardiomyopathy based on ferroptosis-related

genes. Exp Ther Med. 27:2212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Teringova E and Tousek P: Apoptosis in

ischemic heart disease. J Transl Med. 15:872017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Li Y, An M, Fu X, Meng X, Ma Y, Liu H, Li

Q, Xu H and Chen J: Bushen Wenyang Huayu Decoction inhibits

autophagy by regulating the SIRT1-FoXO-1 pathway in endometriosis

rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 308:1162772023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dong Y, Chen H, Gao J, Liu Y, Li J and

Wang J: Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and

autophagy in coronary heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 136:27–41.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen L, Li S, Zhu J, You A, Huang X, Yi X

and Xue M: Mangiferin prevents myocardial infarction-induced

apoptosis and heart failure in mice by activating the Sirt1/FoxO3a

pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 25:2944–2955. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yang X, Jiang T, Wang Y and Guo L: The

role and mechanism of SIRT1 in resveratrol-regulated osteoblast

autophagy in osteoporosis rats. Sci Rep. 9:184242019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Tang L, Zeng Z, Zhou Y, Wang B, Zou P,

Wang Q, Ying J, Wang F, Li X, Xu S, et al: Bacillus

amyloliquefaciens SC06 Induced AKT-FOXO signaling pathway-mediated

autophagy to alleviate oxidative stress in IPEC-J2 cells.

Antioxidants (Basel). 10:15452021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Sengupta A, Molkentin JD and Yutzey KE:

FoxO transcription factors promote autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J

Biol Chem. 284:28319–28331. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson

CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK,

Buxton AE, et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2023 update:

A report from the american heart association. Circulation.

147:e93–e621. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Li H, Sureda A, Devkota HP, Pittalà V,

Barreca D, Silva AS, Tewari D, Xu S and Nabavi SM: Curcumin, the

golden spice in treating cardiovascular diseases. Biotechnol Adv.

38:1073432020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Mokhtari-Zaer A, Marefati N, Atkin SL,

Butler AE and Sahebkar A: The protective role of curcumin in

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cell Physiol.

234:214–222. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jabczyk M, Nowak J, Hudzik B and

Zubelewicz-Szkodzińska B: Curcumin in metabolic health and disease.

Nutrients. 13:44402021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Li M, Wu H, Yuan Y, Hu B and Gu N: Recent

fabrications and applications of cardiac patch in myocardial

infarction treatment. VIEW. 3:202001532022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Lin L, Liu S, Chen Z, Xia Y, Xie J, Fu M,

Lu D, Wu Y, Shen H, Yang P and Qian J: Anatomically resolved

transcriptome and proteome landscapes reveal disease-relevant

molecular signatures and systematic changes in heart function of

end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. VIEW. 4:202200402023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Guo S, Meng XW, Yang XS, Liu XF, Ou-Yang

CH and Liu C: Curcumin administration suppresses collagen synthesis

in the hearts of rats with experimental diabetes. Acta Pharmacol

Sin. 39:195–204. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

51

|

Ramachandran C, Rodriguez S, Ramachandran

R, Raveendran Nair PK, Fonseca H, Khatib Z, Escalon E and Melnick

SJ: Expression profiles of apoptotic genes induced by curcumin in

human breast cancer and mammary epithelial cell lines. Anticancer

Res. 25:3293–3302. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Kim YS, Kwon JS, Cho YK, Jeong MH, Cho JG,

Park JC, Kang JC and Ahn Y: Curcumin reduces the cardiac

ischemia-reperfusion injury: Involvement of the toll-like receptor

2 in cardiomyocytes. J Nutr Biochem. 23:1514–1523. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Hu F, Hu T, Qiao Y, Huang H, Zhang Z,

Huang W, Liu J and Lai S: Berberine inhibits excessive autophagy

and protects myocardium against ischemia/reperfusion injury via the

RhoE/AMPK pathway. Int J Mol Med. 53:492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Chen HY, Xiao ZZ, Ling X, Xu RN, Zhu P and

Zheng SY: ELAVL1 is transcriptionally activated by FOXC1 and

promotes ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by

regulating autophagy. Mol Med. 27:142021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ,

Kroemer G and Tang D: Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent

cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 66:89–100. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Wu D, Zhang K and Hu P: The role of

autophagy in acute myocardial infarction. Front Pharmacol.

10:5512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Cai W, Liu L, Shi X, Liu Y, Wang J, Fang

X, Chen Z, Ai D, Zhu Y and Zhang X: Alox15/15-HpETE aggravates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte

ferroptosis. Circulation. 147:1444–1460. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW and

Kimmelman AC: Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo

receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 509:105–109. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Guo Z, Liao Z, Huang L, Liu D, Yin D and

He M: Kaempferol protects cardiomyocytes against

anoxia/reoxygenation injury via mitochondrial pathway mediated by

SIRT1. Eur J Pharmacol. 761:245–253. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Huang L, He H, Liu Z, Liu D, Yin D and He

M: Protective effects of isorhamnetin on cardiomyocytes against

anoxia/reoxygenation-induced injury is mediated by SIRT1. J

Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 67:526–537. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Kuno A, Hosoda R, Tsukamoto M, Sato T,

Sakuragi H, Ajima N, Saga Y, Tada K, Taniguchi Y, Iwahara N and

Horio Y: SIRT1 in the cardiomyocyte counteracts doxorubicin-induced

cardiotoxicity via regulating histone H2AX. Cardiovasc Res.

118:3360–3373. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Ding X, Zhu C, Wang W, Li M, Ma C and Gao

B: SIRT1 is a regulator of autophagy: Implications for the

progression and treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion.

Pharmacol Res. 199:1069572024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Wei YJ, Wang JF, Cheng F, Xu HJ, Chen JJ,

Xiong J and Wang J: miR-124-3p targeted SIRT1 to regulate cell

apoptosis, inflammatory response, and oxidative stress in acute

myocardial infarction in rats via modulation of the

FGF21/CREB/PGC1α pathway. J Physiol Biochem. 77:577–587. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yu S, Qian H, Tian D, Yang M, Li D, Xu H,

Chen J, Yang J, Hao X, Liu Z, et al: Linggui Zhugan Decoction

activates the SIRT1-AMPK-PGC1α signaling pathway to improve

mitochondrial and oxidative damage in rats with chronic heart

failure caused by myocardial infarction. Front Pharmacol.

14:10748372023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Zhang W, Wang X, Tang Y and Huang C:

Melatonin alleviates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via

inhibiting oxidative stress pyroptosis and apoptosis by activating

Sirt1/Nrf2 pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 162:1145912023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Xie W, Zhu T, Zhang S and Sun X:

Protective effects of Gypenoside XVII against cerebral

ischemia/reperfusion injury via SIRT1-FOXO3A- and

Hif1a-BNIP3-mediated mitochondrial autophagy. J Transl Med.

20:6222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|