Introduction

Myocardial ischemia (MI) is typically caused by

inadequate blood flow in the coronary arteries. A worldwide

epidemiological analysis indicated that the number of cases of MI

steadily increased from 1990-2019, reaching a total of 197 million

cases by 2019 (1). Myocardial

infarction, caused by prolonged and severe MI, is a prevalent

cardiovascular disease and a major cause of disability and

mortality worldwide (2,3). The accumulation of reactive oxygen

species (ROS) during MI creates conditions for the generation of

oxidative stress (4). Currently,

the primary treatment method for myocardial infarction is coronary

artery reperfusion (5). This

procedure is crucial for treating ischemic myocardial tissue damage

by removing harmful metabolites and restoring normal metabolism

(4). However, the sudden

reintroduction of high oxygen tension due to blood flow reperfusion

results in increased levels of oxygen free radicals, leading to a

surge in ROS levels. This causes more severe tissue damage than

that caused by ischemia (6-8),

a condition known as MI/reperfusion injury (MIRI). MIRI is a

complex pathological process related to the production of ROS and

mitochondrial dysfunction, involving reduced ATP production and

destruction of the mitochondrial ridge (9). Therefore, it is necessary to

clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying MIRI to develop

effective prevention strategies.

During reperfusion, uncontrolled ROS-mediated

oxidative stress has been considered a key triggering factor for

MIRI (10). ROS mainly originate

from the byproduct of the mitochondrial respiratory chain (11). Under physiological conditions,

ROS participate in signal transduction and regulate various

physiological activities of the heart (12). However, uncontrolled increases in

ROS levels cause damage to biological macromolecules, such as lipid

peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction, which may lead to

ferroptosis (13). Nuclear

factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) is a transcription

factor that activates endogenous antioxidant enzymes in response to

oxidative stress and ferroptosis (14). It is widely expressed in tissues

of oxygen-consuming organs, such as the muscles, heart and blood

vessels (15). When oxidative

stress occurs, Nrf2 is activated and is transferred from the

cytoplasm to the nucleus to maintain cellular redox balance and

avoid the occurrence of lipid peroxidation (16).

The regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) family

serves a crucial role in the regulatory processes of the

cardiovascular system (17). A

previous study reported a significant increase in the mRNA and

protein expression levels of RGS3 and RGS4 in failing heart tissues

(18). It has been shown that

the expression of RGS2 inhibits G-protein signaling in the

myocardium of adult mice, which is necessary to prevent the early

development of compensatory hypertrophy in response to pressure

overload (19). The deletion of

RGS6 exacerbates ischemic injury in the hearts of mice (20). RGS12 is currently the largest

known mammalian RGS protein (21). It has been reported that the

expression of RGS12 may contribute to pathological cardiac

hypertrophy (22). RGS12

contains a central RGS domain, a postsynaptic density

protein-95/discs-large/zona occludens homology domain, a

phosphotyrosine binding domain, tandem Ras binding domains and a

Gαi/o-Loco interaction motif (21), which suggests the versatility of

RGS12 and its association with multiple signaling pathways. RGS12

has been reported to regulate oxidative stress through Nrf2 in

various tissues, including neuronal cells (23) and osteoclasts (24); however, its role in the heart

remains unexplored. The deficiency of RGS12 activates Nrf2 and

impairs the production of ROS in osteoclast (24), but overexpression of RGS12

inhibited the activation of Nrf2 (24). Targeting RGS12 may thus alleviate

oxidative stress and inflammation by regulating the Nrf2 pathway in

the hippocampus of depressed rats (23). However, in MIRI, it is currently

unknown whether RGS12 affects the Nrf2 pathway.

Penehyclidine hydrochloride (PHC) is an

anticholinergic drug with antimuscarinic and antinicotinic activity

(25). Previous studies have

reported that preconditioning with PHC is effective in preventing

ischemia/reperfusion injury in multiple organs, which is achieved

by inhibiting apoptosis and relieving oxidative stress (26,27). Preconditioning with PHC

alleviates the mitochondrial dynamic imbalance and protects

myocardial cells against MIRI (28). This suggests a potential

protective role of PHC against MIRI; however, the underlying

molecular mechanisms have not yet been fully elucidated.

The present study aimed to establish a mouse model

of MIRI and a cell model subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R)

to investigate the regulatory role and molecular mechanisms of

RGS12 in MIRI and the myocardium after PHC preconditioning.

Materials and methods

Adenovirus (Ad) construction

The short hairpin RNA (shRNA) sequence targeting

mouse RGS12 (shRGS12, 5′-GGACCTCAGCACTCGAGAAAG-3′), along with a

non-specific sequence (shNC, 5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3′), were

synthesized and inserted into pShuttle-CMV plasmids (cat. no.

BR009; Hunan Fenghui Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) by General Biology,

Inc. A total of 25 μg shuttle plasmids were transfected into

293A cells at room temperature using Lipofectamine 3000 (cat. no.

L3000015; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and P3000 (cat. no.

L3000015; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The coding region of

RGS12 was cloned into pDC315 plasmids by YouBio (cat. no. VT1500)

to construct the RGS12 overexpression vector. The mass of nucleic

acid used was 9 μg. Empty vector without any exogenous

fragment was used as a negative control. A total of 27 μg

plasmids (shuttle plasmid: skeleton plasmid=1:2) were transfected

into the 293A cells at room temperature using Lipofectamine 3000

(41.8 μl) (cat. no. L3000015; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) and P3000 (54 μl) (cat. no. L3000015; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). After 14 days, the cell supernatant containing

Ad particles was collected.

Animal experiments

The present study utilized 210 10-week-old male

C57BL/6 mice (weighing 24.0±2.0 g) that underwent a 1-week

acclimatization period to the feeding regimen. During the

experiment, the mice were allowed to eat and drink freely. Mice

were subjected to a 12 h light/dark cycle under controlled

environmental conditions, including a temperature maintained at

22±1°C and humidity levels between 45-55%. The animal experiments

were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei North University

(approval no. HBNU202306022105; Zhangjiakou, China).

The mice were allocated into two groups (Sham and

MIRI) through a random process, and were anesthetized using an

intraperitoneal injection of 75 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg

xylazine. Mice in the MIRI group were subjected to left main

coronary artery ligation for a duration of 30 min to induce

ischemia, followed by the restoration of blood flow for 24 h to

establish the MIRI model (29).

The mice in the Sham group underwent a surgical procedure without

ligation as a control measure. After surgery, all the animals were

administered a subcutaneous injection of 5 mg/kg carprofen for pain

relief (30) and were placed in

a comfortable environment that included maintaining a constant

temperature and humidity, as well as providing a cage with adequate

space and non-toxic, non-irritating bedding material. Animal health

and behavior were monitored every 4-6 h. According to the National

Institutes of Health Guidelines for Endpoints in Animal Study

Proposals (31) the following

humane endpoints were used: Anorexia (lack or loss of appetite),

failure to drink, labored breathing, gasping, lethargy or

persistent recumbency and excessive hyperthermia or

hypothermia.

Next, the mice were randomly divided into two groups

[MIRI + Ad-RGS12 and MIRI + Ad-empty vector (EV)]. After the mice

were anesthetized, the plasmid vectors carrying the coding sequence

of RGS12 or EVs were packaged into Ads and injected into the left

ventricular free wall of the mice in both groups with a total

volume of 30 μl and a concentration of 1×1011

plaque forming units/ml, 72 h prior to the induction of MIRI

(32).

For further experiments, the mice were randomly

divided into four groups, denoted as the MIRI, MIRI + PHC, MIRI +

PHC + Ad-EV and MIRI + PHC + Ad-RGS12 groups. The mice in the

experimental MIRI + PHC, MIRI + PHC + Ad-EV and MIRI + PHC +

Ad-RGS12 groups received a tail vein injection of PHC (cat. no.

HY-137976; Merck KGaA) at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight 1 h prior

to the induction of MIRI (33).

The mice in the MIRI + PHC + Ad-EV and MIRI + PHC + Ad-RGS12 groups

received Ad injections 72 h prior to undergoing MIRI, followed by

the administration of PHC 1 h prior to the induction of MIRI.

The left ventricular function of all the mice was

evaluated under anesthesia utilizing an echocardiographic imaging

system. Subsequently, the mice were sacrificed via exsanguination.

When the mice experienced cardiac arrest and their pupils were

dilated, they were considered deceased. Blood (~1 ml) from postcava

was collected. Serum and myocardial tissues were subsequently

obtained for further analysis.

A total of 210 animals were used in the present

study, of which 195 were euthanized (n=24/group), while 15 were

found deceased during the operation. Of the animals euthanized, 2

animals experienced persistent recumbency and were euthanized at

the humane endpoints and 1 animal was used to explore the

appropriate antibody concentrations and incubation times in a

preliminary experiment.

Cell culture

The mouse myocardial cell line HL-1 (cat. no.

iCell-m077; iCell) was cultured in Minimum Essential Medium (cat.

no. 41500; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.)

containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin streptomycin and incubated at

37°C and 5% CO2.

Cell induction

HL-1 cells were exposed to various concentrations of

PHC (1, 2.5 and 5 μg/ml) at 37°C for a duration of 2 h

(34), after which they were

subjected to H/R injury according to previously established

protocols (35). Briefly, the

cells were cultured in a medium devoid of FBS for a duration of 12

h. Following this, the cells were subjected to hypoxic conditions

consisting of 1% O2, 94% N2 and 5%

CO2 for a period of 8 h. Subsequently, the cells were

returned to normal culture conditions for 12 h to induce H/R

injury. Control cells were cultured under normal conditions. Cell

viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay in

accordance with the manufacturer's protocol (cat. no. KGA317;

Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.). The cells were incubated with

CCK-8 reagent at 37°C for 2 h.

Infection

Ad was added to the culture medium. Following a 48-h

infection period, the HL-1 cells were exposed to PHC (5

μg/ml) at 37°C and H/R was induced in cells after 2 h. The

concentration of 5 μg/ml was selected on the basis that 5

μg/ml PHC treatment had the strongest inhibition of RGS12

expression and did not decrease cell viability.

Staining with 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium

chloride (TTC)

Myocardial tissues cryopreserved at -2°C were

sectioned into 1 mm slices, followed by staining with a 0.4%

solution of TTC at 37°C for 15 min in the dark. The viable

myocardial tissues exhibited a red stain, while the infarcted

region displayed a white appearance.

Measurement of biochemical markers

The activity of LDH, CK and AST in serum were

measured. The content of MDA and the activity of SOD in ischemic

penumbra of myocardial tissues were detected. The content of MDA

and the activity of SOD and CAT in the cells were detected. Samples

were preprocessed according to the instructions provided by the

kits' manufacturer. The myocardial tissues were homogenized in

normal saline, then centrifuged at 4°C at 12,000 × g for 10 min and

the supernatant was collected for analysis. The cells were lysed

using ultrasound on ice (power, 200 W; 5 sec ultrasonic treatment;

15 sec interval, repeated 5 times) and then centrifuged at 4°C at

15,000 × g for 10 min to separate the supernatant for detection.

The serum was analyzed directly without any pretreatment. The

activities of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; cat. no. A020), creatine

kinase (CK; cat. no. A032), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; cat.

no. C010), catalase (CAT; cat. no. A007), glutathione peroxidase

(GPX; cat. no. A005) and superoxide dismutase (SOD; cat. no.

A003-1), as well as the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA; cat.

no. A001), were quantified utilizing test kits procured from

Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute in accordance with the

manufacturer's protocols. The activity of all enzymes was measured

through enzymatic reaction at 37°C. MDA content was determined

based on the Thibabituric Acid assay at 95°C (cat. no. A001;

Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute). Serum troponin T (TnT)

levels were assessed using an ELISA kit (cat. no. SEB820Mu; Wuhan

USCN Business Co., Ltd.).

Histopathological analysis

Myocardial tissues obtained from the left ventricle

were preserved in a 4% paraformaldehyde solution at room

temperature for 24 h, subsequently embedded in paraffin and

sectioned into 5 μm slices. The sections underwent a

dewaxing process and were stained with hematoxylin (5 min) and

eosin (3 min) at room temperature. Subsequently, the samples were

imaged using a light microscope (BX53; Olympus Corporation).

Immunofluorescence

The HL-1 cell and ischemic penumbra of myocardial

tissue were pretreated separately. The cells (5×104)

were seeded onto coverslips in a 24-well plate and subsequently

fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min.

Cells were permeabilized using 0.1% Triton X-100 (cat. no. ST795;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) for 30 min at room

temperature. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into

5-μm slices. The slices were rehydrated in descending

alcohol series (95, 85, and 75%), and boiled in an antigen

retrieval solution (1.8% 0.1 M citrate buffer and 8.2% 0.1 M sodium

citrate buffer) at 95°C for 10 min. The slices were washed in a PBS

buffer. Subsequently, the prepared tissue or cell specimens were

treated with 1% BSA (cat. no. A602440-0050; Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. Samples were

incubated at 4°C overnight with the following primary antibodies:

RGS12 (cat. no. DF4415; 1:100; Affinity Biosciences) and Nrf2 (cat.

no. AF0639; 1:100; Affinity Biosciences). Following multiple washes

in PBS buffer, samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with Alexa

Fluor 555-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies

(cat. no. 4413; 1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.) in the

dark. DAPI (cat. no. D106471-5mg; Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical

Technology Co., Ltd.) culture for 5 min at room temperature was

utilized as a nuclear counterstain. Subsequently, the stained

sections were imaged using a fluorescence microscope.

ROS and lipid ROS detection

The ischemic penumbra of myocardial tissue was

embedded in Optimal Cutting Temperature Compound freezing medium

(cat. no. 4583; Sakura Finetek USA, Inc.), frozen at −20°C and cut

into 10 μm sections for staining. Cells (1×105)

were seeded into a 12-well plate and cultured to a confluence of

70-80%, and subsequently prepared for staining procedures. DHE (4

μM; cat. no. D807594; Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co.,

Ltd.) was added to the tissues and cells and incubated at 37°C for

30 min. The stained sections and cells were then examined using a

fluorescence microscope to determine ROS levels.

To detect lipid ROS levels, cells (5×105)

were seeded into a 6-well plate and incubated with C11-BODIPY

581/591 (cat. no. MX5211; Shanghai Maokang Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

at 37°C for 30 min, and the alteration in fluorescence emission

peak wavelength from 590-510 nm was assessed using a flow cytometer

(NovoCyte; Agilent Technologies, Inc.).

Fe2+ detection

The presence of Fe2+ in tissues and cells

was identified using a Ferrous Iron Colorimetric Assay kit [cat.

no. E-BC-K773-M (for tissues); cat. no. E-BC-K881-M (for cells);

Wuhan Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.] according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

The HL-1 cells and ischemic penumbra of myocardial

tissue were homogenized in TRIpure lysis buffer (cat. no. RP1001;

BioTeke Corporation) and the total RNA concentration was assessed

using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized using

the BeyoRT II M-MLV reverse transcriptase (cat. no. D7160L;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) as per the manufacturer's

guidelines. The resulting cDNA was utilized as a template for qPCR.

The qPCR procedure was conducted with SYBR Green (cat. no. SY1020;

Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) and 2×Taq PCR

MasterMix (cat. no. PC1150; Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd.) using a fluorescent qPCR instrument

(Exicycler 96; Bioneer Corporation). The following thermocycling

conditions were used: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 95°C for 10 sec,

60°C for 10 sec and 72°C for 15 s. The 2−ΔΔCq method was

used to analyze the target gene expression (36). The primers used were obtained

from General Biology, Inc. and the sequences were as follows: RGS12

forward (F), 5′-AAGCGGACTTTGTTTCGG-3′ and reverse (R),

5′-GGAGCACCTTTCTGTTTGT-3′; and β-actin F,

5′-CATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCC-3′ and R, 5′-ATGGAGCCACCGATCCACA-3′.

Western blotting

The HL-1 cells and ischemic penumbra of myocardial

tissue were used for western blotting. Total protein was extracted

using lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) containing phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (cat. no.

ST506; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) on ice for 5 min. The

resulting lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 5 min at 4°C

to obtain supernatants containing proteins. The cytoplasmic and

nuclear proteins were then separated using the Nuclear Protein and

Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction kit (cat. no. P0027; Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). The protein concentration was

determined using the BCA method (cat. no. P0011; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology). The 30 μg protein samples were then

separated using SDS-PAGE with varying concentrations of gel (8, 10

and 14%) and a 5% stacking gel, followed by transfer onto PVDF

membranes. The membranes were blocked using a blocking buffer (cat.

no. P023; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at room temperature

for 1 h and subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with primary

antibodies targeting RGS12 (cat. no. DF4415; 1:500; Affinity

Biosciences), GPX4 (cat. no. A1933; 1:1,000; ABclonal Biotech Co.,

Ltd.), solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11; cat. no.

DF12509; 1:500; Affinity Biosciences) and Nrf2 (cat. no. AF0639;

1:1,000; Affinity Biosciences). After washing using a washing

reagent (cat. no. P023; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology), the

blots were incubated for 45 min at 37°C with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-rabbit IgG,

cat. no. A0208; goat anti-mouse IgG, cat. no. A0216; 1:5,000;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Histone H3 (cat. no. AF0009;

1:1,000; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) and β-actin (cat. no.

sc-47778; 1:1,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) were used as

internal references for nuclear protein and total protein,

respectively. The blots were visualized using ECL reagent (cat. no.

P0018; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

analysis

The cells were fixed using an Electron Microscope

Fixative (cat. no. G1102; Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.)

and incubated at 4°C for 2 h before being embedded in 1% agarose.

Cells were treated with 1% osmium tetroxide for at room temperature

2 h. Following dehydration in ascending alcohol series (30, 50, 70,

80, 95 and 100%) the cells were encased in 812 epoxy resin monomers

(cat. no. 02659-ABl; Structure Probe, Inc.) at 37°C overnight.

Embedded cells were sliced into 60-80 nm sections, stained with 2%

uranyl acetate (8 min) and 2.6% lead citrate (8 min) at room

temperature and subsequently examined using TEM (cat. no. H-7650;

Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation). The mitochondria were

manually counted.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad

software (version 9.0; Dotmatics). The data are presented as the

mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was conducted using the unpaired

Student's t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-hoc test to

identify significant differences between the experimental groups.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

RGS12 is highly expressed in a MIRI model

of mice and in cells subjected to H/R

The MIRI model was developed using a 30 min ischemia

and 24 h reperfusion (Fig. 1A).

The present study assessed heart function and myocardial

damage-related markers in mice to confirm the successful

establishment of the MIRI model. The echocardiography results

indicated a significant reduction in the left ventricular ejection

fraction (LVEF) and left ventricular fractional shortening (LVFS)

in the mice with MIRI compared with the control group (Fig. 1B). The mice with MIRI exhibited

severe injury in the myocardial tissues, as indicated by an

increase in the size of the infarct (Fig. 1C) and significantly increased

activity levels of LDH and CK in comparison with the control mice

(Fig. 1D). The intensity of red

fluorescence in the ischemic penumbra of the mice with MIRI was

greater compared with that of the control mice, indicating an

increase in ROS levels caused by MIRI (Fig. 1E). The concentration of

Fe2+ in the myocardial tissues of mice with MIRI was

significantly higher compared with that in the control group

(Fig. 1F), suggesting the

occurrence of ferroptosis. These results indicated that MIRI was

successfully induced in the mice subjected to ischemia/reperfusion.

Subsequently, it was demonstrated that RGS12 was highly expressed

in the mice with MIRI compared with the control group, as evidenced

by the results of RT-qPCR, western blotting analysis and

immunofluorescence (Fig. 1G and

H). Moreover, a cell model of H/R-induced injury was developed

using 12 h serum starvation, 8 h hypoxia and 12 h reoxygenation

(Fig. 1I). The expression level

of RGS12 was assessed. Similar patterns of RGS12 expression levels

were also observed in HL-1 cells with H/R injury compared with

control cells (Fig. 1J and

K).

| Figure 1RGS12 is highly expressed in MIRI

mice and H/R cells. (A) The MIRI model was developed using a 30 min

ischemia and 24 h reperfusion. (B) Echocardiogram, LVEF and LVFS of

mice. (C) Quantification of the infarct area in the myocardial

tissue and images of infarct tissue. (D) Serum LDH and CK activity.

(E) ROS levels (magnification, ×400) and (F) Fe2+

content in the myocardial tissue. RGS12 expression levels in the

myocardial tissue was analyzed using (G) reverse-transcription

quantitative PCR and western blotting and (H) immunofluorescence.

Magnification, ×400. n=6. (I) A cell model of H/R-induced injury

was developed using a 12 h serum starvation, 8 h hypoxia and 12 h

reoxygenation. RGS12 expression levels in H/R cells was analyzed

using (J) reverse transcription quantitative PCR and western

blotting and (K) immunofluorescence. Magnification, ×400. n=3. Data

were presented as the mean ± SD. MIRI, myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; RGS12,

regulator of G-protein signaling 12; LVEF, left ventricular

ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase; ROS, reactive

oxygen species. |

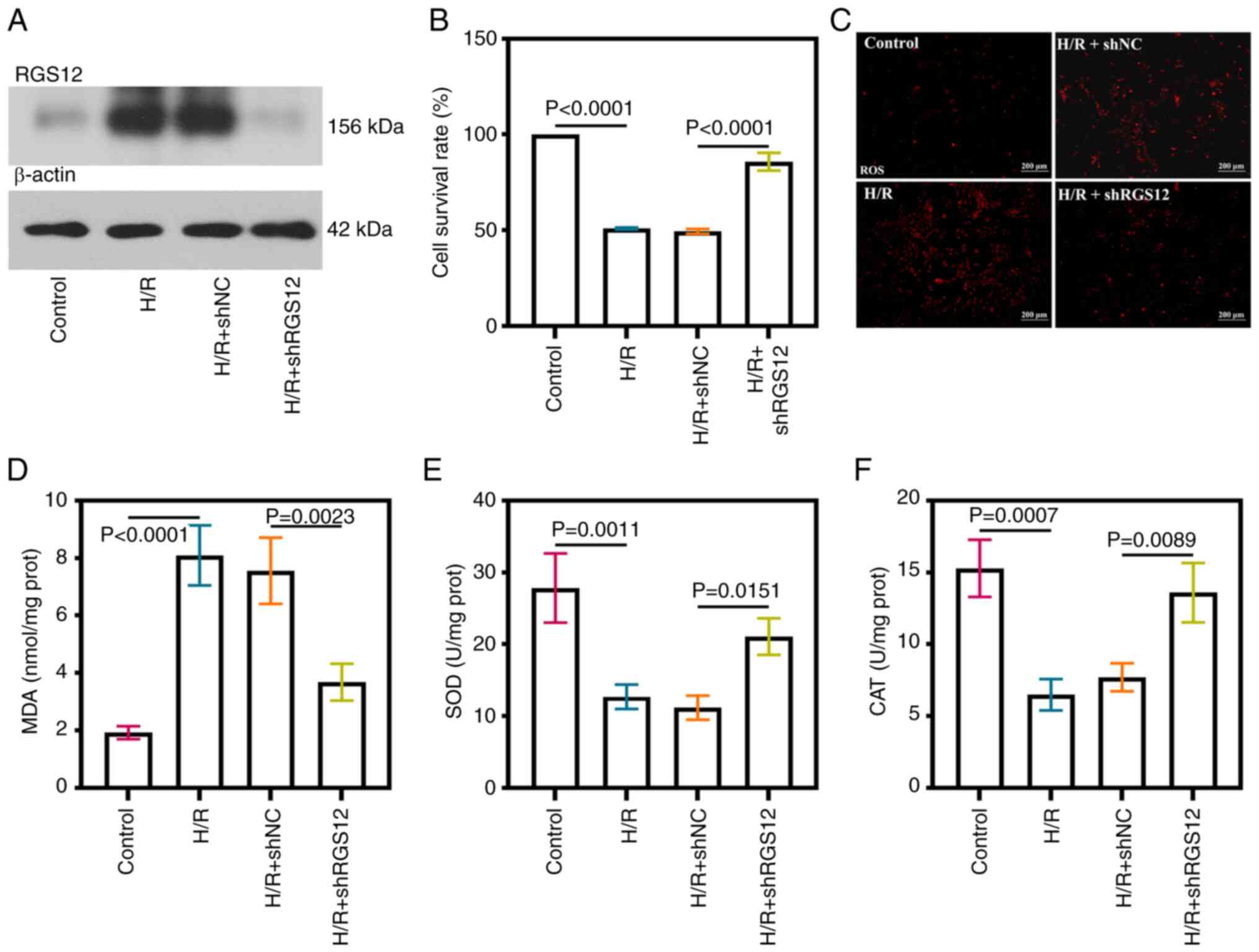

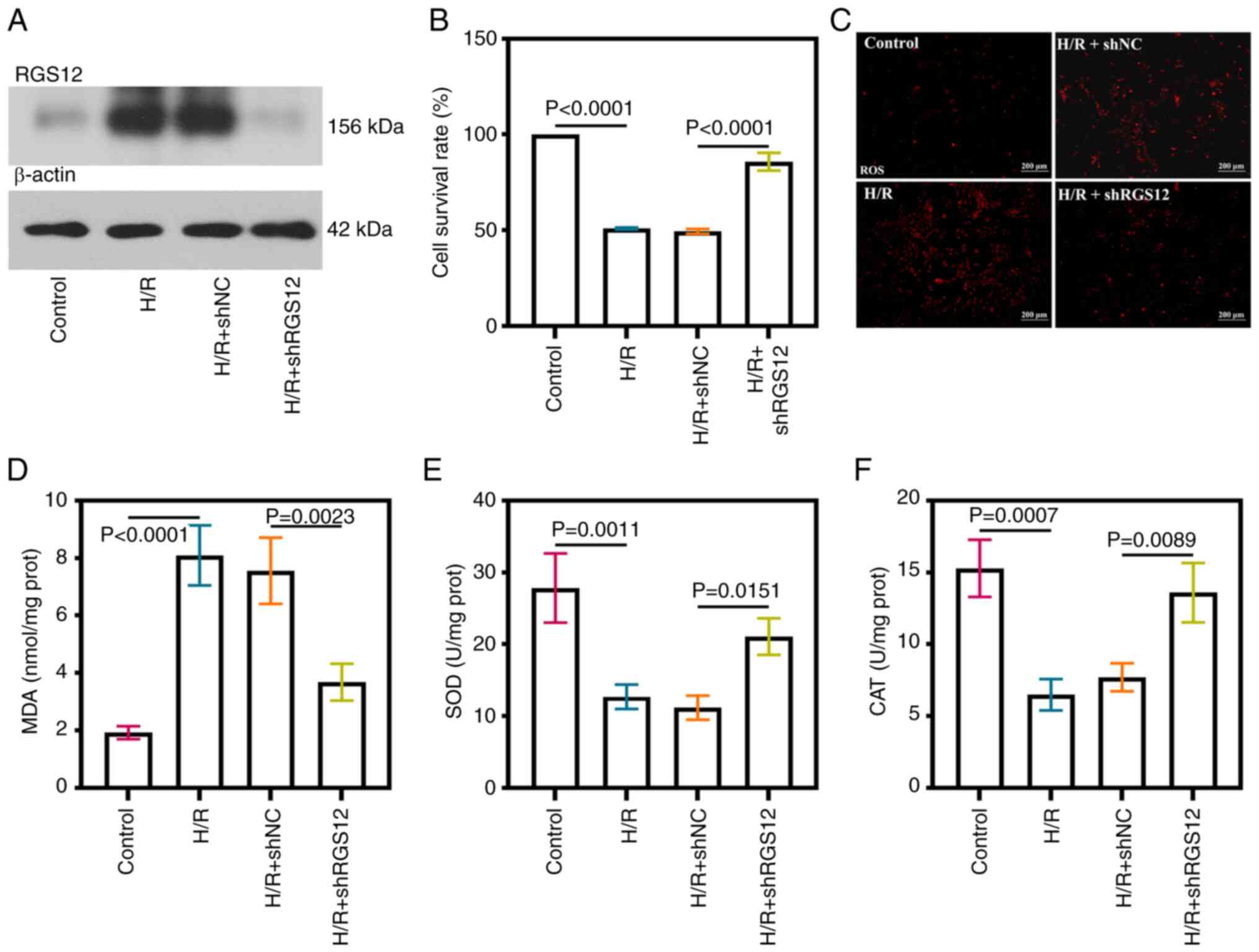

Downregulation of RGS12 relieves

oxidative stress in H/R cells

To investigate the involvement of RGS12 in MIRI, the

expression of RGS12 was knocked down in HL-1 cells (Fig. S1A and B). Increased protein

expression levels of RGS12 were observed in the cells subjected to

H/R injury, except for the cells in which RGS12 expression was

suppressed (Fig. 2A). The

viability of the cells subjected to H/R was significantly reduced

compared with the control cells; however, the silencing of RGS12

resulted in a significant increase in cell viability (Fig. 2B). Elevated levels of ROS and MDA

were detected in the cells subjected to H/R compared with those in

the controls (Fig. 2C and D).

Conversely, the silencing of RGS12 led to a reduction in ROS levels

and the inhibition of MDA production. The activities of SOD and CAT

significantly decreased following H/R-induced injury; however,

these significantly increased after the silencing of RGS12

(Fig. 2E and F).

| Figure 2RGS12 silencing relieves oxidative

stress in H/R cells. (A) RGS12 protein expression levels in H/R

cells. (B) Cell survival rate. (C) ROS levels (magnification,

×100). (D) MDA content. (E) SOD and (F) CAT activity in H/R cells.

n=3. MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; CAT,

catalase; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; RGS12, regulator of G-protein

signaling 12; sh, short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; prot,

protein; ROS, reactive oxygen species. The data are presented as

the mean ± SD. |

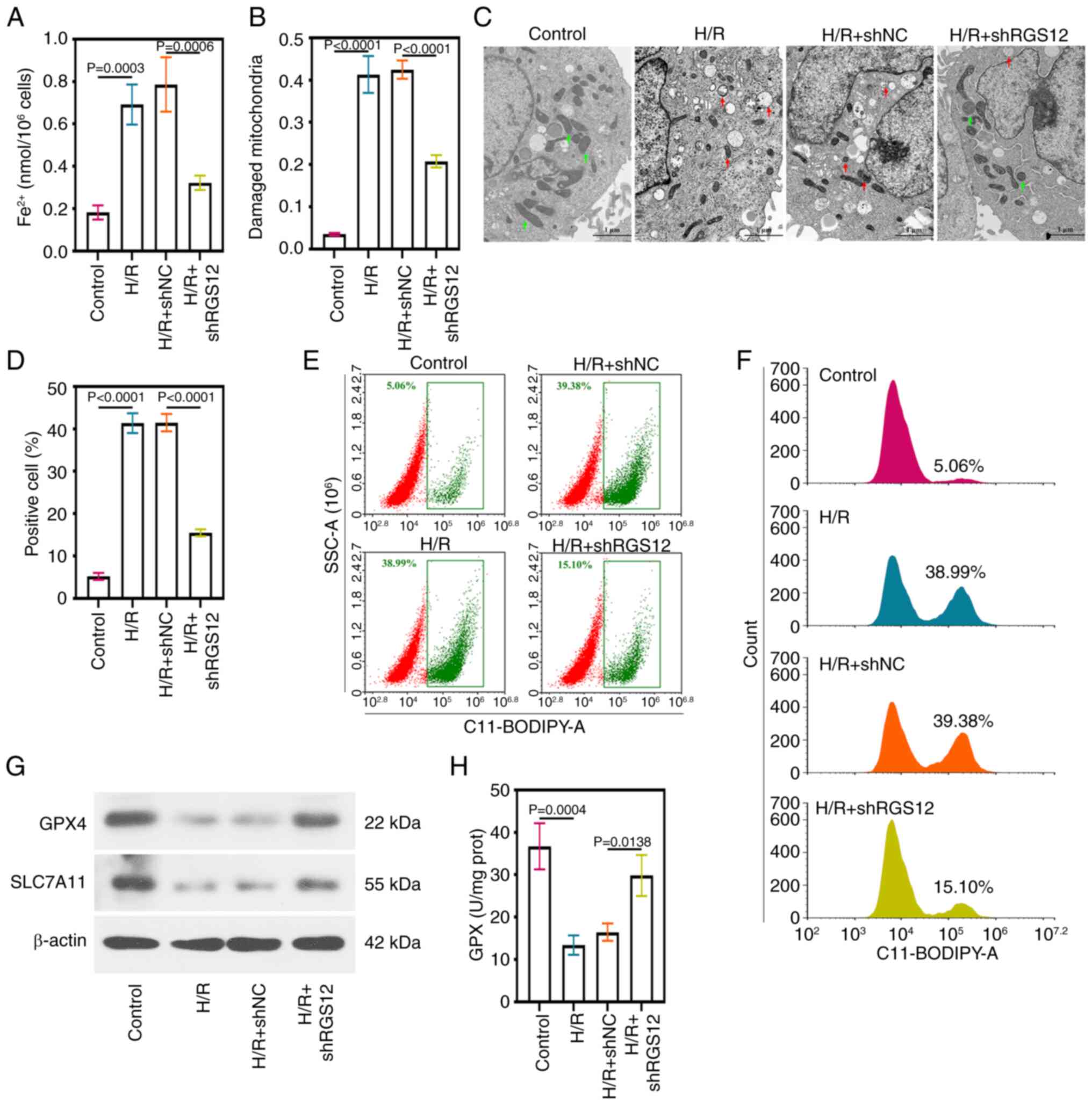

Downregulation of RGS12 inhibits

ferroptosis in H/R cells

Excess ROS and MDA levels often predict the

occurrence of ferroptosis (13).

The levels of Fe2+ in the cells subjected to H/R

significantly increased, while these levels were significantly

reduced by the silencing of RGS12 (Fig. 3A). Mitochondrial morphology was

assessed using TEM and the control cells displayed intact

mitochondria (Fig. 3B).

Conversely, H/R-induced damage was evident in the mitochondrial

membrane and cristae, with protective effects observed after the

silencing of RGS12. The proportion of damaged mitochondria was

calculated by evaluating the ratio of the number of damaged

mitochondria to the total number of mitochondria in the visual

field (Fig. 3B), which was

consistent with the results shown in the representative images

(Fig. 3C). Lipid ROS detection

using C11-BODIPY 581/591 staining, combined with flow cytometric

analysis, indicated that RGS12 silencing reduced lipid ROS

production (Fig. 3D).

Additionally, the proportion of C11-BODIPY 581/591-positive cells

in the samples were measured (Fig.

3E and F). Cells undergoing ferroptosis exhibited significantly

elevated lipid ROS levels, which were significantly suppressed by

the silencing of RGS12. In addition, the protein expression levels

of GPX4 and SLC7A11 were significantly reduced in the cells

subjected to H/R compared with those in the control cells. However,

the silencing of RGS12 expression significantly increased the

protein expression levels of GPX4 and SLC7A11.

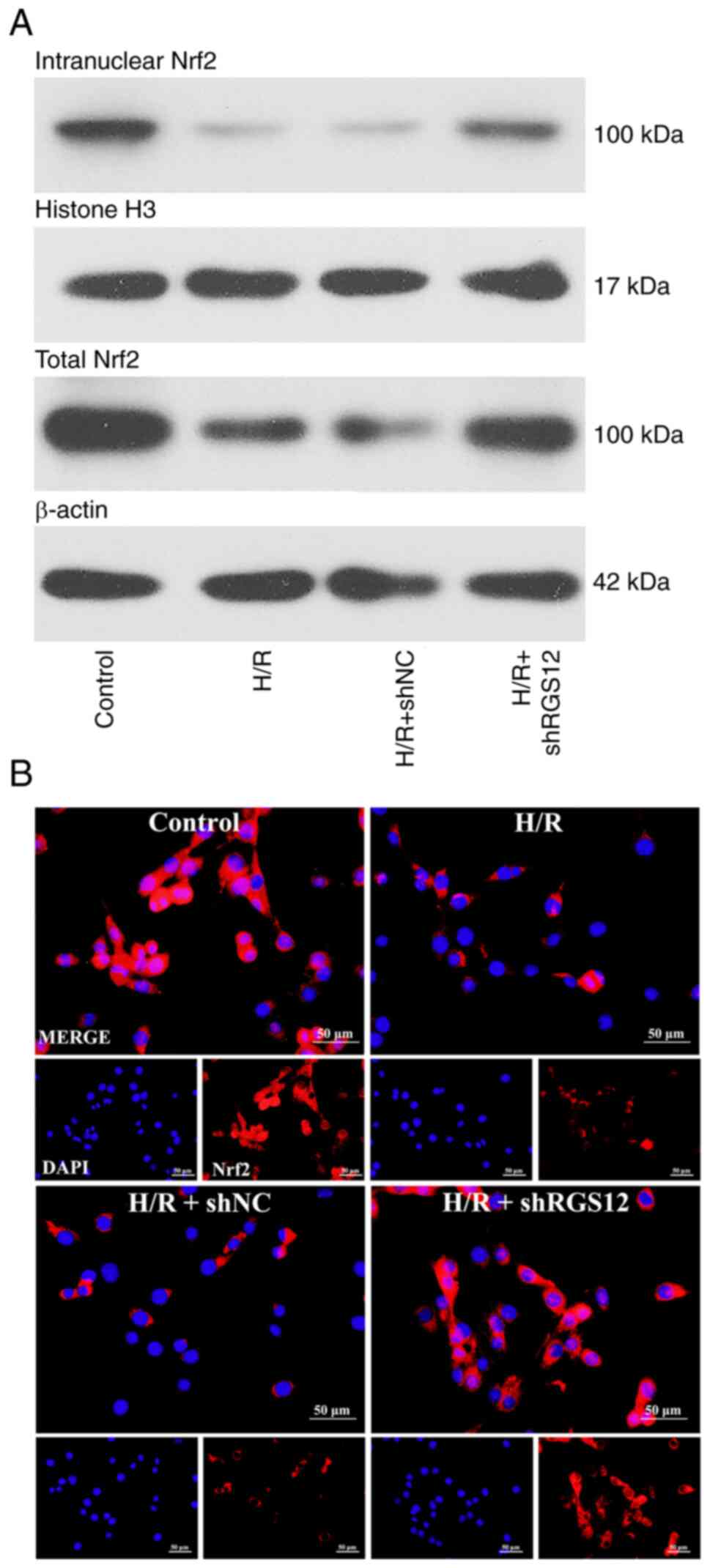

Downregulation of RGS12 activates the

Nrf2 pathway

Nrf2 serves a crucial role in the regulation of

ferroptosis and oxidative stress (37). Therefore, the present study

investigated the effects of RGS12 on Nrf2 expression. Upon the

induction of H/R, the protein expression levels of both nuclear and

total Nrf2 decreased compared with those in the control cells

(Fig. 4A). Conversely, the

silencing of RGS12 led to a significant increase in Nrf2 protein

expression levels. Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated a

similar trend, indicating that the low expression level of RGS12

induced the expression of Nrf2 in cells subjected to H/R (Fig. 4B).

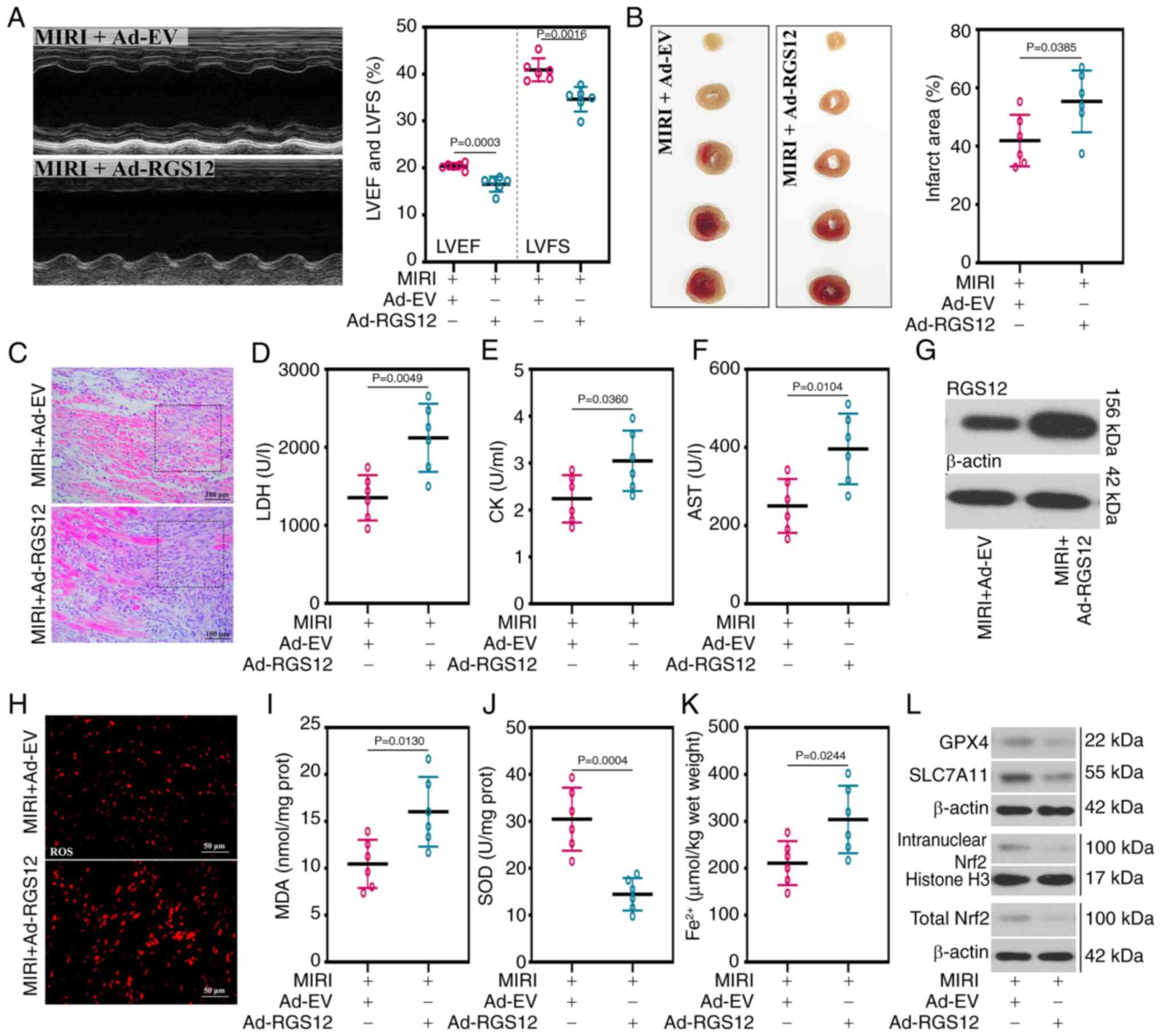

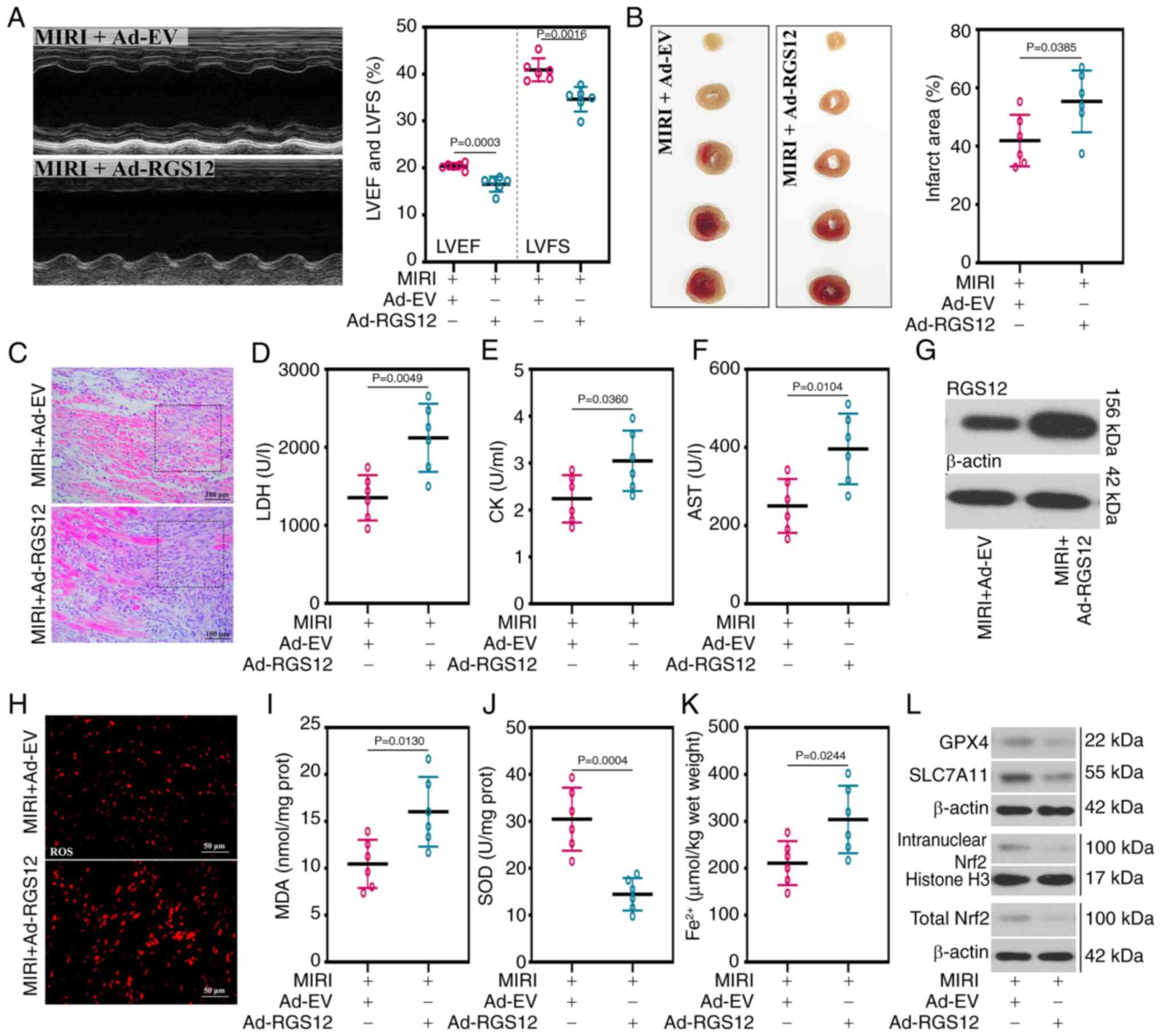

Overexpression of RGS12 exacerbates MIRI

in mice

In the aforementioned experiments, it was

demonstrated that the silencing of RGS12 mitigated H/R-injury in

HL-1 cells. Subsequently, overexpression of RGS12 was induced in

mice to further elucidate its potential role in MIRI. The LVEF and

LVFS significantly decreased in the mice with RGS12 overexpression,

compared with the control group (Fig. 5A). In addition, compared with the

MIRI + Ad-EV group, the increase in TnT serum levels of the MIRI +

Ad-RGS12 group also indicated the damage inflicted on cardiac

function (Fig. S2). In the mice

with RGS12 overexpression, a significant increase in the infarct

area of the myocardial tissue (Fig.

5B), accompanied by pronounced leukocyte infiltration in the

myocardial tissue (Fig. 5C) and

the significantly increased activity of myocardial enzymes, such as

LDH, CK and AST (Fig. 5D-F),

were observed compared with the control group. The expression of

RGS12 was examined in the myocardial tissue and it was demonstrated

that the protein expression level of RGS12 was successfully

increased in the RGS12-overexpressing mice compared with that in

the control group (Fig. 5G).

Furthermore, oxidative stress levels were significantly increased

in the mice in which RGS12 was overexpressed (Fig. 5H), resulting in significantly

increased MDA levels and decreased SOD activity compared with the

control group (Fig. 5I and J).

The overexpression of RGS12 in mice exacerbated ferroptosis, as

evidenced by the significantly elevated levels of Fe2+

and the reduced protein expression level of GPX4 (Fig. 5K and L). Additionally, the

upregulation of RGS12 inhibited the activation of the Nrf2 pathway

(Fig. 5L).

| Figure 5RGS12 upregulation exacerbates MIRI

in mice. (A) Echocardiogram, LVEF and LVFS of mice with MIRI. (B)

Representative images of 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride

staining and quantification of the infarct area in myocardial

tissues. (C) Representative images of hematoxylin and eosin

staining of myocardial tissues (magnification, ×200). The activity

of (D) LDH, (E) CK and (F) AST in serum. (G) RGS12 protein

expression levels in myocardial tissues. (H) ROS level

(magnification, ×400), (I) MDA content, (J) SOD activity and (K)

Fe2+ content. (L) Protein expression levels of GPX4,

SLC7A11, intranuclear Nrf2 and total Nrf2 in myocardial tissues.

Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=6). Ad, adenovirus; Ad-EV,

Ad-empty vectors; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GPX4,

glutathione peroxidase 4; SLC7A11, solute carrier family 7 member

11; MIRI, myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury; LVEF, left

ventricular ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional

shortening; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; RGS12, regulator of

G-protein signaling 12; ROS, reactive oxygen species; nrf2Nrf2,

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. |

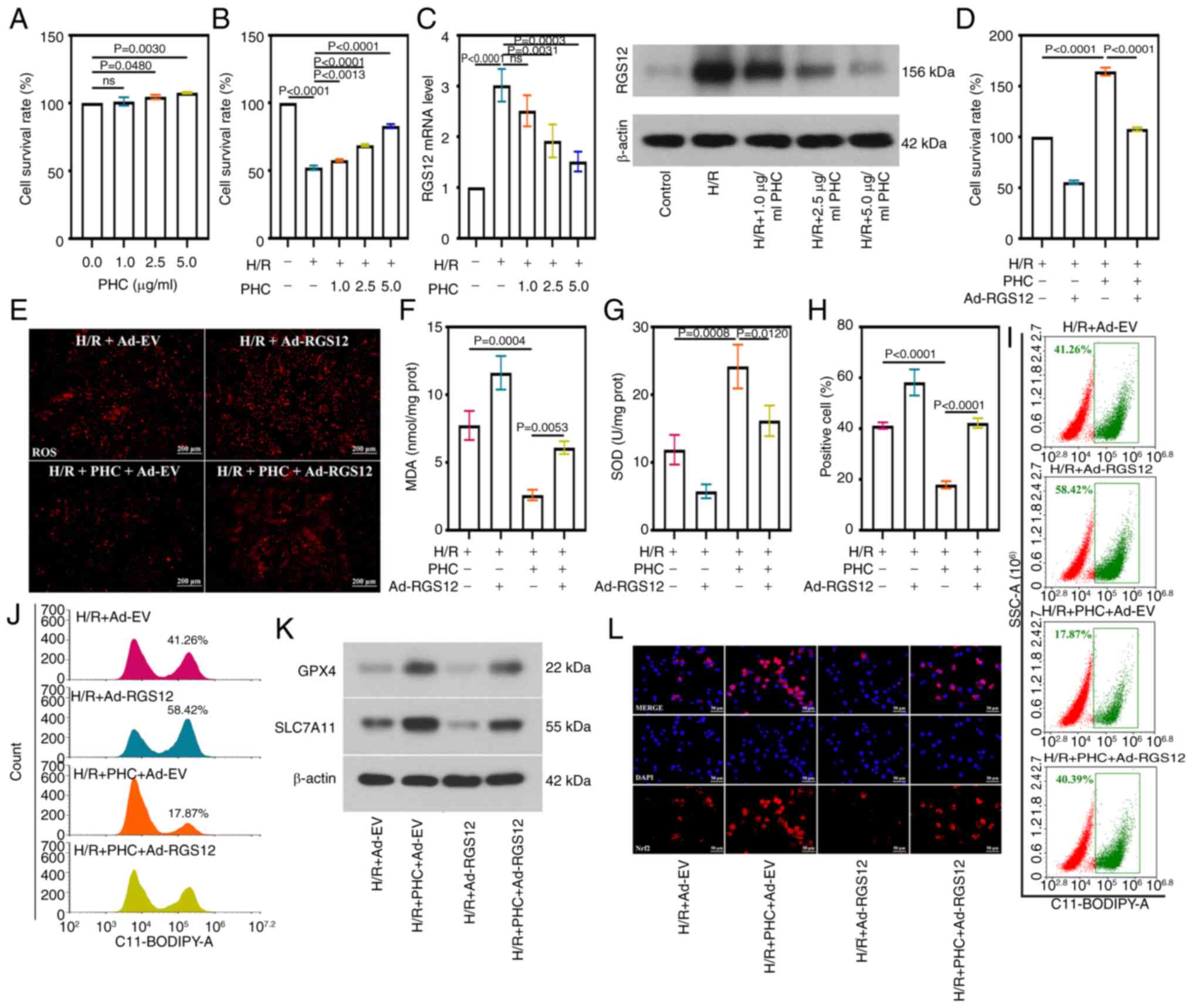

RGS12 attenuates the protective effect of

PHC on oxidative stress and ferroptosis in cells subjected to

H/R

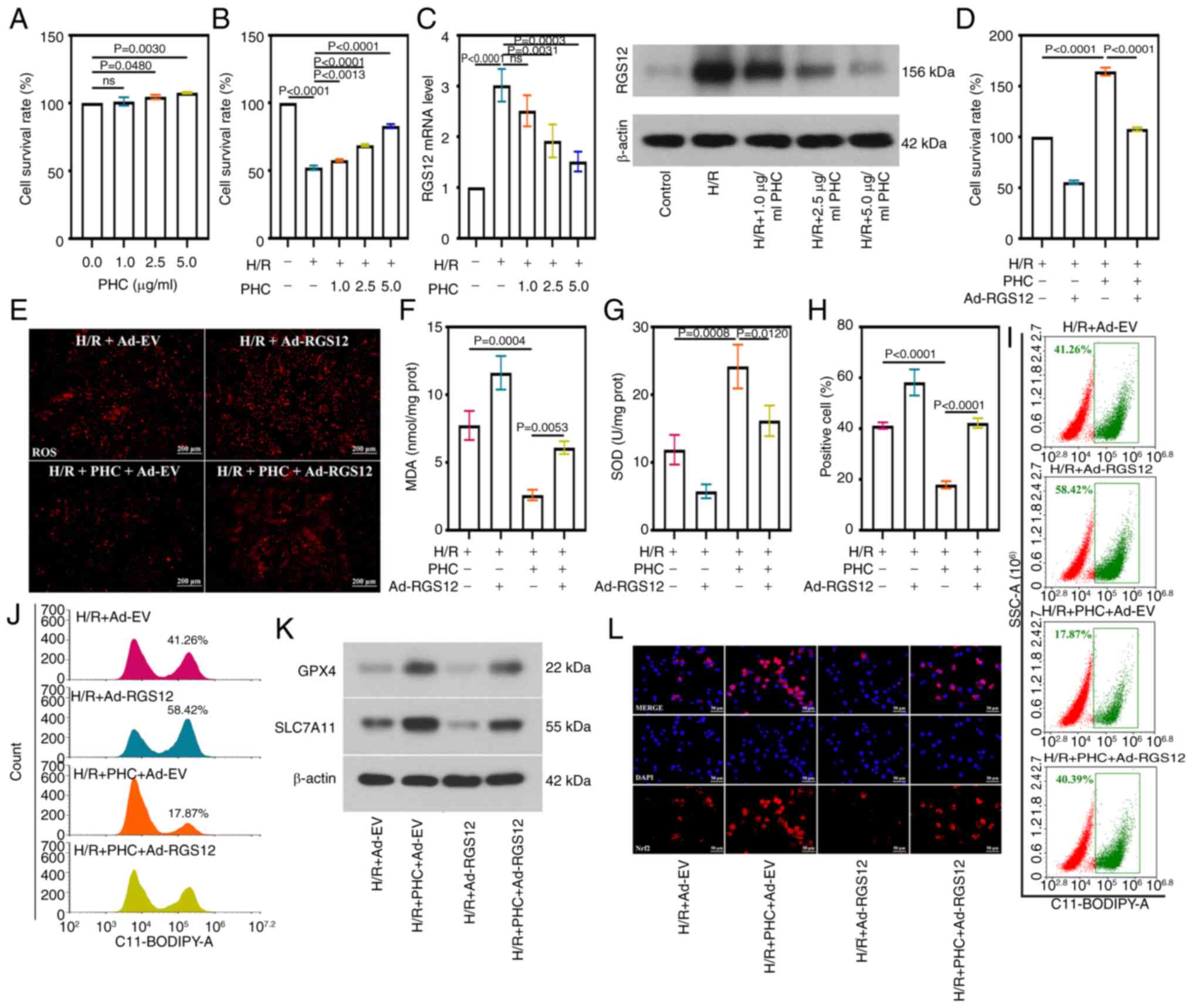

As aforementioned, in a preliminary experiment, the

present study identified the effect of RGS12 on MIRI. Subsequently,

the current study aimed to explore whether RGS12 mediates the

protective effects of PHC on the heart. PHC was shown to exert a

positive effect on the survival of HL-1 cells under normal

conditions, with cell viability significantly increasing as the

concentration of PHC treatment increased to 2.5 and 5 μg/ml,

compared with the viability of control cells and those treated with

1 μg/ml PHC (Fig. 6A).

Upon the induction of H/R, the beneficial effects of PHC on cell

survival became more pronounced, with cell viability significantly

increasing as the PHC concentration increased, peaking at 5

μg/ml (Fig. 6B).

Conversely, the expression level of RGS12 decreased as the PHC

concentration increased (Fig.

6C). A concentration of 5 μg/ml PHC was selected to be

used in subsequent experiments, resulting in a significant

downregulation of RGS12 expression in HL-1 cells. To explore the

role of RGS12 in the effect of PHC against H/R damage, RGS12 was

overexpressed in HL-1 cells (Fig.

S3A). The elevated levels of RGS12 led to a significantly

decreased cell survival rate and negated the beneficial effects of

PHC treatment in H/R-induced HL-1 cells (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, PHC treatment

reduced ROS production (Fig.

6E), MDA level (Fig. 6F) and

SOD activity (Fig. 6G) in

H/R-induced cells. PHC treatment significantly reduced the

production of lipid ROS (Fig.

6H). Additionally, PHC treatment reduced the number of cell

points within the gate (Fig. 6I)

and a reduction in the number of cells with high fluorescence

intensity (Fig. 6J). PHC

treatment increased the protein expression levels of GPX4 and

SLC7A11 in cells subjected to H/R (Fig. 6K) and promoted the activation of

the Nrf2 signaling pathway (Fig.

6L). The overexpression of RGS12 reversed the protective

effects of PHC. In addition, in cells overexpressing RGS12,

increased concentrations of PHC treatment caused increased cell

viability (Fig. S3B), decreased

MDA levels (Fig. S3C) and

increased SOD activity (Fig.

S3D). This suggested that PHC prevented MIRI through inhibiting

RGS12 in a concentration-dependent manner.

| Figure 6RGS12 attenuates the protective

effect of PHC on oxidative stress and ferroptosis in H/R cells. (A)

Survival rate of HL-1 cells treated with PHC. (B) Survival rate of

HL-1 cells treated with H/R and PHC. (C) RGS12 expression levels in

H/R cells induced with PHC. (D) Survival rate of HL-1 cells. (E)

ROS levels (magnification, ×100), (F) MDA content, and (G) SOD

activity in H/R cells. Lipid reactive oxygen species levels were

analyzed using flow cytometry (H), and the result was shown by

scatter diagram (I) and histogram. (J,K) Protein expression levels

of GPX4 and SLC7A11 and (L) the cellular location of Nrf2 in H/R

cells (magnification, ×400). Data are presented as the mean ± SD

(n=3). Ad, adenovirus; Ad-EV, Ad-empty vectors; PHC, penehyclidine

hydrochloride; RGS12, regulator of G-protein signaling 12; ROS,

reactive oxygen species; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPX4, glutathione

peroxidase 4; SLC7A11, solution carrier family 7 member 11; Nrf2,

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; prot, protein. |

RGS12 attenuates the protective effect of

PHC on MIRI

Administration of PHC resulted in the remission of

MIRI in mice in vivo. PHC treatment led to significant

improvements in LVEF and LVFS in mice with MIRI (Fig. 7A). Compared with MIRI + Ad-RGS12

group, the TnT level of MIRI + PHC + Ad-RGS12 group was reduced,

indicating that PHC administration improved cardiac function

(Fig. S2). Treatment with PHC

relieved the alleviated MIRI and ameliorated the damaged myocardial

tissue morphology (Fig. 7B and

7C), as myocardial fiber tissue

structure was clear and inflammatory cell infiltration was

decreased. Furthermore, PHC treatment significantly decreased the

activity of myocardial enzymes compared with those in the control

group, including LDH (Fig. 7D),

CK (Fig. 7E) and AST (Fig. 7F). Notably, the RGS12 protein

expression levels were lower in the myocardial tissue of all

PHC-treated mice compared with the mice with MIRI, apart from those

in the mice in which RGS12 was overexpressed (Fig. 7G). PHC administration reduced ROS

production (Fig. 7H) and

inhibited oxidative stress-induced injury, including increased MDA

level (Fig. 7I) and decreased

SOD activity (Fig. 7J).

Ferroptosis in mice with MIRI was also alleviated by PHC

administration, which was evidenced by reduced Fe2+

(Fig. 7K) and enhanced

expression of GPX4 (Fig. 7L).

Moreover, treatment with PHC induced the activation of the Nrf2

pathway in the model of MIRI (Fig.

7L). This was also observed in the MIRI + PHC + Ad-EV group.

However, the overexpression of RGS12 abrogated the effects of PHC

treatment. These findings suggested that RGS12 attenuated the

protective effects of PHC in the myocardial tissue of mice with

MIRI.

| Figure 7RGS12 attenuates the protective

effect of PHC on a MIRI mouse model. (A) Echocardiogram, LVEF and

LVFS of mice with MIRI. (B) Representative images of

2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride staining and quantification of

the infarct area in myocardial tissues. (C) Representative images

of hematoxylin and eosin staining in myocardial tissues

(magnification, ×200). Black boxes represent areas with significant

pathological changes. The activity of (D) LDH, (E) CK and (F) AST

in serum. (G) RGS12 protein expression levels in myocardial

tissues. (H) ROS levels (magnification, ×400), (I) MDA content, (J)

SOD activity and (K) Fe2+ content in myocardial tissues.

(L) Protein expression levels of GPX4 and intranuclear Nrf2. The

data are presented as the mean ± SD (n=6). RGS12, regulator of

G-protein signaling 12; PHC, penehyclidine hydrochloride; MIRI,

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury; LVEF, left ventricular

ejection fraction; LVFS, left ventricular fractional shortening;

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase; AST, aspartate

aminotransferase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MDA,

malondialdehyde; SOD, superoxide dismutase; GPX4, glutathione

peroxidase 4; prot, protein; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid

2-related factor 2. |

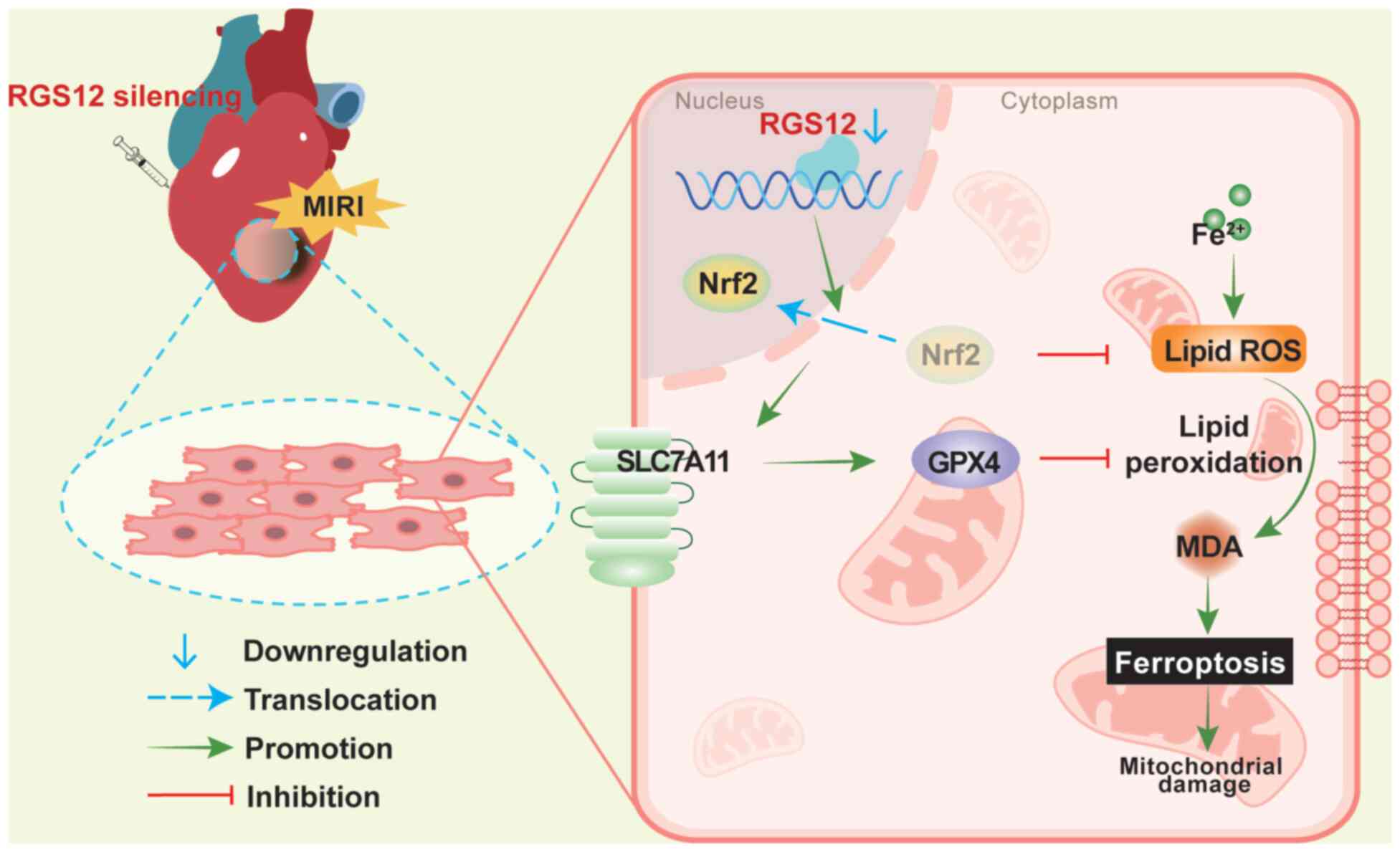

Discussion

The present study observed a high expression level

of RGS12 in a mouse model of MIRI. The mechanism of action of RGS12

in PHC pretreatment was investigated through cell experiments and

verified in a mouse model. These results suggested that the

silencing of RGS12 alleviated H/R-induced damage to myocardial

cells, including reducing oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation,

thereby preventing ferroptosis, which may involve the activation of

the Nrf2 pathway. The overexpression of RGS12 led to the opposite

results in vivo and in vitro. Preconditioning with

PHC relied on the RGS12-mediated regulatory mechanism to protect

the heart from MIRI in a concentration-dependent manner.

Oxidative stress is a key physiological process

involved in MIRI (38). The

present study demonstrated that RGS12 promoted oxidative stress in

the MIRI process by inhibiting the Nrf2 pathway, a typical

antioxidant pathway. The regulation of the Nrf2 pathway by RGS12

may involve a direct effect. For instance, it has been demonstrated

that RGS12 promotes the degradation of the Nrf2 protein in RAW

264.7 cells (24). In addition,

RGS12 may indirectly regulate the Nrf2 pathway as, for example, it

has been reported that targeting RGS12 leads to a decrease in the

expression of Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1, an upstream

regulatory molecule of Nrf2, thereby activating the Nrf2 pathway

(23,39). Therefore, based on the

aforementioned research findings, the effects of RGS12 on the Nrf2

pathway in MIRI may be either direct or indirect, both of which

support the conclusions reported herein. In addition to the Nrf2

pathway, RGS12 may be involved in the regulation of oxidative

stress by affecting other pathways. RGS12 activates the classical

NF-κB inflammatory pathway and contributes to the onset of

inflammatory arthritis (40).

Inflammation and oxidative stress are interrelated processes that

mutually promote one another, potentially due to crosstalk between

the NF-κB and Nrf2 pathways (41). Thus, RGS12 may indirectly promote

oxidative stress by activating the NF-κB pathway.

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent mechanism of cell

death closely related to oxidative stress. It is characterized by

the accumulation of Fe2+ and lipid peroxidation

(42). The regulatory effects of

RGS12 on ferroptosis remain unclear; however, targeting of the Nrf2

pathway by RGS12 may be a key mechanism involved in the promotion

of ferroptosis. Nrf2 is a crucial transcriptional regulator of

anti-ferroptosis genes and its target genes participate in the

ferroptosis cascade reaction (14). The activation of the Nrf2 pathway

mediates the inhibition of ferroptosis and exerts protective

effects on the heart, which supports the conclusion obtained in the

present study (43).

Furthermore, the regulation of ferroptosis by RGS12 may involve

other pathways, such as the MAPK pathway. It has been reported that

RGS12 activates the MAPK pathway in pathological cardiac

hypertrophy (22). The

activation of the MAPK pathway may mediate ferroptosis in rat

myocardial cells (44).

Therefore, RGS12 may enhance ferroptosis by activating the MAPK

pathway, indicating the complex mechanism by which RGS12 regulates

ferroptosis.

The present study demonstrated that RGS12 promoted

oxidative stress and aggravated MIRI by inhibiting the Nrf2 pathway

in myocardial cells. The Nrf2 signaling pathway is a classical

pathway associated with oxidative stress and ferroptosis. Previous

studies have demonstrated the therapeutic potential of the Nrf2

pathway in MIRI (15,43,45). The present study showed the

regulatory effects of RGS12 on this pathway, which further

highlighted the influence of RGS12 on the MIRI process. However,

RGS12 may affect oxidative stress and ferroptosis through various

factors. It has been reported that RGS12 is an activator of the

NF-κB and MAPK pathways (22,40), which are well-established

inflammatory signaling pathways. The activation of these pathways

stimulates the production of inflammatory factors and amplifies the

inflammatory response, while simultaneously decreasing the

expression levels of certain anti-ferroptosis-related proteins,

such as heme oxygenase 1, ultimately leading to ferroptosis

(46). Targeting the NF-κB/MAPK

pathway effectively inhibits ferroptosis in osteoarthritis

(47). In addition, the

activation of the NF-κB and MAPK pathways is a marker of oxidative

stress in peripheral blood mononuclear cell and endothelial cells

(48,49) and inhibiting the activation of

the NF-κB and MAPK pathways alleviates oxidative stress in

bronchial epithelial cells and nerve cells (50,51). Therefore, the promotion of

oxidative stress and ferroptosis by RGS12 may involve inflammatory

processes, such as the activation of the NF-κB and MAPK

pathways.

The present study primarily investigated the

regulatory mechanisms involving Nrf2-mediated ferroptosis in

myocardial cells, which are the predominant cell type in the heart

and are essential for its contractile function (52). Myocardial cell death ultimately

results in the structural and functional impairment of the heart

tissue. Preventing MIRI-induced myocardial cell damage effectively

improves cardiac function (53).

Oxidative stress leads to the ferroptosis and apoptosis of

myocardial cells, which is a typical manifestation of MIRI at the

cellular level (54). Therefore,

the present study was conducted using the mouse myocardial cell

line, HL-1. However, the regulatory pattern of RGS12 may differ

between different types of cells. Macrophages are key immune cells

in MIRI, and M1 and M2 macrophage polarization mediates the

enhancement and decrease of MIRI-induced inflammation, respectively

(55). RGS12 has been reported

to induce M1 macrophage polarization (56). IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α secreted by

M1 macrophages enhance the occurrence of ferroptosis (57), and the expression of RGS12 is

increased and the NF-κB pathway is activated in macrophages under

inflammatory conditions (58,59). This suggests that RGS12-induced

M1 macrophage polarization may mediate ferroptosis and the

activation of the NF-κB pathway.

The therapeutic effects of PHC on

ischemia/reperfusion injury have been previously well-established

in animal models and this effect on MIRI is dose-dependent

(33,60). According to previous reports

(33,60), the present study adopted an

optimal dose of 1 mg/kg PHC, which was shown to be effective in

alleviating MIRI in the mouse model. Moreover, it was demonstrated

that PHC prevented MIRI through the inhibition of RGS12 in a

dose-dependent manner using rescue experiments. The present study

demonstrated the molecular mechanism by which PHC attenuates MIRI;

therefore, it could be suggested that targeting RGS12 may be a

promising approach for preventing MIRI by alleviating oxidative

stress and ferroptosis. The present study also provided insights

into the pharmacological effects of the treatment of MIRI using PHC

and may lead to the development of novel strategies for the gene

therapy of MIRI in the future.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

the silencing of RGS12 mediated the protective effects of PHC by

activating the Nrf2 pathway in MIRI, which contributed to the

reduction of oxidative stress and the inhibition of ferroptosis

(Fig. 8). This mechanism could

potentially provide new insights into the prevention and treatment

of MIRI.

Supplementary Data

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CZ was responsible for the conceptualization,

methodology conducting the experiment, data analysis, and drafting

of the manuscript. YW was responsible for conducting the

experiments, data analysis and writing, reviewing and editing of

the manuscript. YZ was responsible for conducting the experiment,

data analysis, data visualization and obtaining resources. JF was

responsible for the use of software. YW and JF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was carried out in accordance with

the requirements in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China. All

animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Hebei

North University (approval no. HBNU202306022105; Zhangjiakou,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Abbreviations:

|

RGS12

|

regulator of G-protein signaling

12

|

|

MI

|

myocardial ischemia

|

|

MIRI

|

MI/reperfusion injury

|

|

H/R

|

hypoxia/reoxygenation

|

|

PHC

|

penehyclidine hydrochloride

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

Nrf2

|

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related

factor 2

|

|

Ad

|

adenovirus

|

|

DHE

|

dihydroethidium

|

|

TTC

|

2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium

chloride

|

|

LDH

|

lactate dehydrogenase

|

|

CK

|

creatine kinase

|

|

AST

|

aspartate aminotransferase

|

|

CAT

|

catalase

|

|

GPX

|

glutathione peroxidase

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase

|

|

TnT

|

troponin T

|

|

TEM

|

transmission electron microscopy

|

|

LVEF

|

left ventricular ejection

fraction

|

|

LVFS

|

left ventricular fractional

shortening

|

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding for the present study was provided by the Hebei Province

Natural Science Foundation Project (grant no. H2022405031).

References

|

1

|

Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, Addolorato

G, Ammirati E, Baddour LM, Barengo NC, Beaton AZ, Benjamin EJ,

Benziger CP, et al: Global burden of cardiovascular diseases and

risk factors, 1990-2019: Update from the GBD 2019 study. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 76:2982–3021. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Wang J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Huang H, Roy S, Song

Z and Guo B: Recent advances in nanomedicines for imaging and

therapy of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Control

Release. 353:563–590. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Galeone A, Grano M and Brunetti G: Tumor

necrosis factor family members and myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

injury: State of the art and therapeutic implications. Int J Mol

Sci. 24:46062023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chen QM and Maltagliati AJ: Nrf2 at the

heart of oxidative stress and cardiac protection. Physiol Genomics.

50:77–97. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

5

|

Bangalore S, Pursnani S, Kumar S and Bagos

PG: Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical

therapy for prevention of spontaneous myocardial infarction in

subjects with stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation.

127:769–781. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xiang M, Lu Y, Xin L, Gao J, Shang C,

Jiang Z, Lin H, Fang X, Qu Y, Wang Y, et al: Role of oxidative

stress in reperfusion following myocardial ischemia and its

treatments. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021:66140092021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Algoet M, Janssens S, Himmelreich U, Gsell

W, Pusovnik M, Van den Eynde J and Oosterlinck W: Myocardial

ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation.

Trends Cardiovasc Med. 33:357–366. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Deng F, Zhang LQ, Wu H, Chen Y, Yu WQ, Han

RH, Han Y, Zhang XQ, Sun QS, Lin ZB, et al: Propionate alleviates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury aggravated by Angiotensin II

dependent on caveolin-1/ACE2 axis through GPR41. Int J Biol Sci.

18:858–872. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen M, Zhong G, Liu M, He H, Zhou J, Chen

J, Zhang M, Liu Q, Tong G, Luan J and Zhou H: Integrating network

analysis and experimental validation to reveal the

mitophagy-associated mechanism of Yiqi Huoxue (YQHX) prescription

in the treatment of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.

Pharmacol Res. 189:1066822023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Peoples JN, Saraf A, Ghazal N, Pham TT and

Kwong JQ: Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart

disease. Exp Mol Med. 51:1–13. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bleier L and Dröse S: Superoxide

generation by complex III: From mechanistic rationales to

functional consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1827:1320–1331.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Burgoyne JR, Mongue-Din H, Eaton P and

Shah AM: Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ

Res. 111:1091–1106. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Wang B, Wang Y, Zhang J, Hu C, Jiang J, Li

Y and Peng Z: ROS-induced lipid peroxidation modulates cell death

outcome: Mechanisms behind apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis.

Arch Toxicol. 97:1439–1451. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R and Zhang DD:

NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and

ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 23:1011072019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shen Y, Liu X, Shi J and Wu X: Involvement

of Nrf2 in myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Int J Biol

Macromol. 125:496–502. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hybertson BM, Gao B, Bose SK and McCord

JM: Oxidative stress in health and disease: The therapeutic

potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med. 32:234–246. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

McNeill SM and Zhao P: The roles of RGS

proteins in cardiometabolic disease. Br J Pharmacol. 181:2319–2337.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Owen VJ, Burton PB, Mullen AJ, Birks EJ,

Barton P and Yacoub MH: Expression of RGS3, RGS4 and Gi alpha 2 in

acutely failing donor hearts and end-stage heart failure. Eur Heart

J. 22:1015–1020. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Takimoto E, Koitabashi N, Hsu S, Ketner

EA, Zhang M, Nagayama T, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Blanton R,

Siderovski DP, et al: Regulator of G protein signaling 2 mediates

cardiac compensation to pressure overload and antihypertrophic

effects of PDE5 inhibition in mice. J Clin Invest. 119:408–420.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Rorabaugh BR, Chakravarti B, Mabe NW,

Seeley SL, Bui AD, Yang J, Watts SW, Neubig RR and Fisher RA:

Regulator of G protein signaling 6 protects the heart from ischemic

injury. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 360:409–416. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

21

|

Siderovski DP, Diversé-Pierluissi M and De

Vries L: The GoLoco motif: A Galphai/o binding motif and potential

guanine-nucleotide exchange factor. Trends Biochem Sci. 24:340–341.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Huang J, Chen L, Yao Y, Tang C, Ding J, Fu

C, Li H and Ma G: Pivotal role of regulator of G-protein signaling

12 in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Hypertension. 67:1228–1236.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lan T, Li Y, Fan C, Wang L, Wang W, Chen S

and Yu SY: MicroRNA-204-5p reduction in rat hippocampus contributes

to stress-induced pathology via targeting RGS12 signaling pathway.

J Neuroinflammation. 18:2432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ng AYH, Li Z, Jones MM and Yang S, Li C,

Fu C, Tu C, Oursler MJ, Qu J and Yang S: Regulator of G protein

signaling 12 enhances osteoclastogenesis by suppressing

Nrf2-dependent antioxidant proteins to promote the generation of

reactive oxygen species. Elife. 8:e429512019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang YA, Zhou WX, Li JX, Liu YQ, Yue YJ,

Zheng JQ, Liu KL and Ruan JX: Anticonvulsant effects of

phencynonate hydrochloride and other anticholinergic drugs in soman

poisoning: Neurochemical mechanisms. Life Sci. 78:210–223. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Wang YP, Li G, Ma LL, Zheng Y, Zhang SD,

Zhang HX, Qiu M and Ma X: Penehyclidine hydrochloride ameliorates

renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. J Surg Res. 186:390–397.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yu C and Wang J: Neuroprotective effect of

penehyclidine hydrochloride on focal cerebral ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Neural Regen Res. 8:622–632. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang Y, Zhao L and Ma J: Penehyclidine

hydrochloride preconditioning provides cardiac protection in a rat

model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via the mechanism

of mitochondrial dynamics mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol. 813:130–139.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Jin JK, Blackwood EA, Azizi K, Thuerauf

DJ, Fahem AG, Hofmann C, Kaufman RJ, Doroudgar S and Glembotski CC:

ATF6 decreases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion damage and links ER

stress and oxidative stress signaling pathways in the heart. Circ

Res. 120:862–875. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

30

|

Wei Z, Fei Y, Wang Q, Hou J, Cai X, Yang

Y, Chen T, Xu Q, Wang Y and Li YG: Loss of Camk2n1 aggravates

cardiac remodeling and malignant ventricular arrhythmia after

myocardial infarction in mice via NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

Free Radic Biol Med. 167:243–257. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Guidelines for Endpoints in Animal Study

Proposals. Animal Research Advisory Committee NIH:

|

|

32

|

Chen L, Luo G, Liu Y, Lin H, Zheng C, Xie

D, Zhu Y, Chen L, Huang X, Hu D, et al: Growth differentiation

factor 11 attenuates cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury via

enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis and telomerase activity. Cell

Death Dis. 12:6652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yang Q, Li L, Liu Z, Li C, Yu L and Chang

Y: Penehyclidine hydrochloride ameliorates renal ischemia

reperfusion-stimulated lung injury in mice by activating Nrf2

signaling. Bioimpacts. 12:211–218. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Liu Z, Li Y, Yu L, Chang Y and Yu J:

Penehyclidine hydrochloride inhibits renal

ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury by activating the

Nrf2 pathway. Aging (Albany NY). 12:13400–13421. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Tang LJ, Zhou YJ, Xiong XM, Li NS, Zhang

JJ, Luo XJ and Peng J: Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 promotes

ferroptosis via activation of the p53/TfR1 pathway in the rat

hearts after ischemia/reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med.

162:339–352. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Liu Y, Wang T, Zhang M, Chen P and Yu Y:

Down-regulation of myocardial infarction associated transcript 1

improves myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in aged diabetic

rats by inhibition of activation of NF-κB signaling pathway. Chem

Biol Interact. 300:111–122. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Chen GH, Song CC, Pantopoulos K, Wei XL,

Zheng H and Luo Z: Mitochondrial oxidative stress mediated

Fe-induced ferroptosis via the NRF2-ARE pathway. Free Radic Biol

Med. 180:95–107. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gumpper-Fedus K, Park KH, Ma H, Zhou X,

Bian Z, Krishnamurthy K, Sermersheim M, Zhou J, Tan T, Li L, et al:

MG53 preserves mitochondrial integrity of cardiomyocytes during

ischemia reperfusion-induced oxidative stress. Redox Biol.

54:1023572022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Dong J, Liu M, Bian Y, Zhang W, Yuan C,

Wang D, Zhou Z, Li Y and Shi Y: MicroRNA-204-5p ameliorates renal

injury via regulating Keap1/Nrf2 pathway in diabetic kidney

disease. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 17:75–92. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Yuan G and Yang S, Ng A, Fu C, Oursler MJ,

Xing L and Yang S: RGS12 Is a novel critical NF-κB activator in

inflammatory arthritis. iScience. 23:1011722020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

McGarry T, Biniecka M, Veale DJ and Fearon

U: Hypoxia, oxidative stress and inflammation. Free Radic Biol Med.

125:15–24. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Li D, Pi W, Sun Z, Liu X and Jiang J:

Ferroptosis and its role in cardiomyopathy. Biomed Pharmacother.

153:1132792022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yan J, Li Z, Liang Y, Yang C, Ou W, Mo H,

Tang M, Chen D, Zhong C, Que D, et al: Fucoxanthin alleviated

myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury through inhibition of

ferroptosis via the NRF2 signaling pathway. Food Funct.

14:10052–10068. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Chen W, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Tan M, Lin J,

Qian X, Li H and Jiang T: Dapagliflozin alleviates myocardial

ischemia/reperfusion injury by reducing ferroptosis via MAPK

signaling inhibition. Front Pharmacol. 14:10782052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yang T, Liu H, Yang C, Mo H, Wang X, Song

X, Jiang L, Deng P, Chen R, Wu P, et al: Galangin attenuates

myocardial ischemic reperfusion-induced ferroptosis by targeting

Nrf2/Gpx4 signaling pathway. Drug Des Devel Ther. 17:2495–2511.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chen Y, Fang ZM, Yi X, Wei X and Jiang DS:

The interaction between ferroptosis and inflammatory signaling

pathways. Cell Death Dis. 14:2052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Zhao C, Sun G, Li Y, Kong K, Li X, Kan T,

Yang F, Wang L and Wang X: Forkhead box O3 attenuates

osteoarthritis by suppressing ferroptosis through inactivation of

NF-κB/MAPK signaling. J Orthop Translat. 39:147–162. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

van den Berg R, Haenen GR, van den Berg H

and Bast A: Transcription factor NF-kappaB as a potential biomarker

for oxidative stress. Br J Nutr. 86(Suppl 1): S121–S127. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Son Y, Cheong YK, Kim NH, Chung HT, Kang

DG and Pae HO: Mitogen-activated protein kinases and reactive

oxygen species: How can ROS activate MAPK pathways? J Signal

Transduct. 2011:7926392011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Dang X, He B, Ning Q, Liu Y, Guo J, Niu G

and Chen M: Alantolactone suppresses inflammation, apoptosis and

oxidative stress in cigarette smoke-induced human bronchial

epithelial cells through activation of Nrf2/HO-1 and inhibition of

the NF-κB pathways. Respir Res. 21:952020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tang Y, Gu W and Cheng L: Evodiamine

attenuates oxidative stress and ferroptosis by inhibiting the MAPK

signaling to improve bortezomib-induced peripheral neurotoxicity.

Environ Toxicol. 39:1556–1566. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Litviňuková M, Talavera-López C, Maatz H,

Reichart D, Worth CL, Lindberg EL, Kanda M, Polanski K, Heinig M,

Lee M, et al: Cells of the adult human heart. Nature. 588:466–472.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhang CX, Cheng Y, Liu DZ, Liu M, Cui H,

Zhang BL, Mei QB and Zhou SY: Mitochondria-targeted cyclosporin A

delivery system to treat myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury of

rats. J Nanobiotechnology. 17:182019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang S, Yan F, Luan F, Chai Y, Li N, Wang

YW, Chen ZL, Xu DQ and Tang YP: The pathological mechanisms and

potential therapeutic drugs for myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury. Phytomedicine. 129:1556492024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Zhuang Q, Li M, Hu D and Li J: Recent

advances in potential targets for myocardial ischemia reperfusion

injury: Role of macrophages. Mol Immunol. 169:1–9. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Yuan G, Huang Y, Yang ST, Ng A and Yang S:

RGS12 inhibits the progression and metastasis of multiple myeloma

by driving M1 macrophage polarization and activation in the bone

marrow microenvironment. Cancer Commun (Lond). 42:60–64. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Yang Y, Wang Y, Guo L, Gao W, Tang TL and

Yan M: Interaction between macrophages and ferroptosis. Cell Death

Dis. 13:3552022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Yuan G and Yang S and Yang S: RGS12

represses oral squamous cell carcinoma by driving M1 polarization

of tumor-associated macrophages via controlling ciliary

MYCBP2/KIF2A signaling. Int J Oral Sci. 15:112023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Yuan G and Yang S and Yang S: Macrophage

RGS12 contributes to osteoarthritis pathogenesis through enhancing

the ubiquitination. Genes Dis. 9:1357–1367. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Lin D, Ma J, Xue Y and Wang Z:

Penehyclidine hydrochloride preconditioning provides

cardioprotection in a rat model of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury. PLoS One. 10:e01380512015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|