Introduction

The fruit of Schisandra chinensis has been

used traditionally to alleviate suffering from chronic cough and

asthma and also to promote the production of body fluid to quench

thirst and arrest sweating in East Asian countries. S.

chinensis has also been employed in the treatment and

prevention of some chronic diseases, such as inflammation,

hepatitis and cancer. The major bioactive constituents of S.

chinensis are lignans, including gomisins A, B, C, E, F, G, K,

N and J, schisandrol B, and schisandrin C (1,2).

Pharmacological studies revealed that lignans isolated from S.

chinensis show anticancer, anti-hepatotoxic, anti-oxidative and

anti-inflammatory activities (3–5).

Gomisins A and N are dibenzo[a,c]cyclooctadiene lignans with R- and

S-biphenyl configurations, respectively (6–8).

Gomisin A shows anti-apoptotic activity and protects the liver from

hepatotoxic chemicals (9). In

contrast, gomisin N induces apoptosis of human hepatic carcinoma

cells (10), and we have recently

reported that gomisin N enhances TNF-α-induced apoptosis via

inhibition of the NF-κB and EGFR survival pathways (11).

On the other hand, tumor necrosis factor

(TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the

TNF superfamily that can initiate apoptosis via the activation of

death receptor 4 (DR4) and DR5 (12,13).

Since TRAIL induces apoptosis in transformed or tumor cells but not

in normal cells, it is considered to be a promising cancer

therapeutic agent, better than other TNF superfamily members, such

as TNF and Fas ligand (14–17),

which have no selectivity for normal and cancer cells. However,

many types of cancer cells are resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis

(18), therefore, it is important

to overcome this resistance to expand the ability of TRAIL in

cancer therapy. In this study, we focused on whether gomisin N was

able to enhance TRAIL-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells and tried to

explore the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-Bcl-xL, XIAP, Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1

(PARP-1), caspase-8 and caspase-3 antibodies were purchased from

Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Antibodies

against Bcl-2, caspase-9, cytochrome-c and β-Actin (C-11) were

obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Recombinant human TRAIL Apo II ligand was obtained from PeproTech,

Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). Gomisins A and N were purchased from

Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Annexin V was

purchased from BioLegend, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-DR4 and

anti-DR5 antibodies used for receptor blockage and z-VAD-FMK were

obtained from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Farmingdale, NY, USA).

Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay

HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified

Eagle’s medium (high glucose) supplemented with 10% fetal calf

serum, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C

in 5% CO2. Cell viability was quantified using the cell

proliferation reagent WST-1

{4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1,3-benzene

disulfonate} (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). HeLa cells were plated in

96-well microplates at 6×103 cells/wells and then

incubated for 24 h. Gomisin N-containing medium was added to the

wells, and cells were incubated for 30 min and then stimulated with

TRAIL. After 24-h incubation, 10 μl of WST-1 solution was added and

absorbance was measured at 450 nm.

Immunoblotting

Cells were treated with gomisin A, gomisin N and

TRAIL, and whole-cell lysates were prepared with lysis buffer [25

mM HEPES pH 7.7, 0.3 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA,

10% Triton X-100, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium

orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 1 mM

dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 μg/ml aprotinin and 10 μg/ml leupeptin].

Cell lysates were collected from the supernatant after

centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. Cell lysates were resolved

by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

and transferred to an Immobilon-P-nylon membrane (Millipore). The

membrane was treated with Block Ace (Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co.,

Ltd., Suita, Japan) and probed with primary antibodies. The

antibodies were detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

anti-rabbit, anti-mouse and anti-goat immunoglobulin G (Dako) and

visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham

Biosciences). Some antibody reactions were carried out in Can Get

Signal solution (Toyobo).

Analyses of apoptotic cells by Annexin

V-FITC

Cells pretreated with gomisin N (100 μM) for 30 min

were treated with TRAIL (100 ng/ml) for 6 h. After harvesting, the

cells were washed twice with 1,000 μl FACS buffer and resuspended

in 500 μl FACS buffer containing 2.5 mM CaCl2 and 1 μg

Annexin V-FITC for 15 min in the dark on ice. The samples were

analyzed with the FACSCalibur System (BD Biosciences).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNAs were prepared using the RNeasy Mini kit

(Qiagen). First-strand cDNAs were synthesized by SuperScript II

reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cDNAs

were amplified quantitatively using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara).

The primer sequences are summarized in Table I (19). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was

performed using an ABI PRISM 7300 sequence detection system

(Applied Biosystems). All data were normalized to GAPDH mRNA.

| Table ISequences of RT-PCR primers. |

Table I

Sequences of RT-PCR primers.

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| GAPDH |

GCACCGTCAAGGTGAGAAC |

ATGGTGGTGAAGACGCCAGT |

| DR4 |

ACAGCAATGGGAACATAG |

GTCACTCCAGGGCGTACAAT |

| DR5 | GCACCACGACCAGAAA | CACCGACCTTGACCAT |

| DcR1 |

GTTTGTTTGAAAGACTTCACTGTG |

GCAGGCGTTTCTGTCTGTGGGAAC |

| DcR2 |

CTTCAGGAAACCAGAGCTTCCCTC |

TTCTCCCGTTTGCTTATCACACGC |

Measurement of intracellular ROS

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation was

measured by flow cytometry following staining with a chloromethyl

derivative of dichloro dihydro-fluorescein diacetate

(CMH2DCFDA; Invitrogen). Briefly, HeLa cells pretreated

with gomisin N (100 μM) for 30 min were treated with TRAIL (100

ng/ml) for 2.5 h. The cells were stained with 5 μM

CMH2DCFDA for 30 min at 37°C and harvested, and

fluorescence intensity was analyzed using the FACSCalibur System

(BD Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as the mean ± SD and were

analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the

Tukey-Kramer test. P<0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

Gomisin N augments TRAIL-induced

apoptosis in HeLa cells

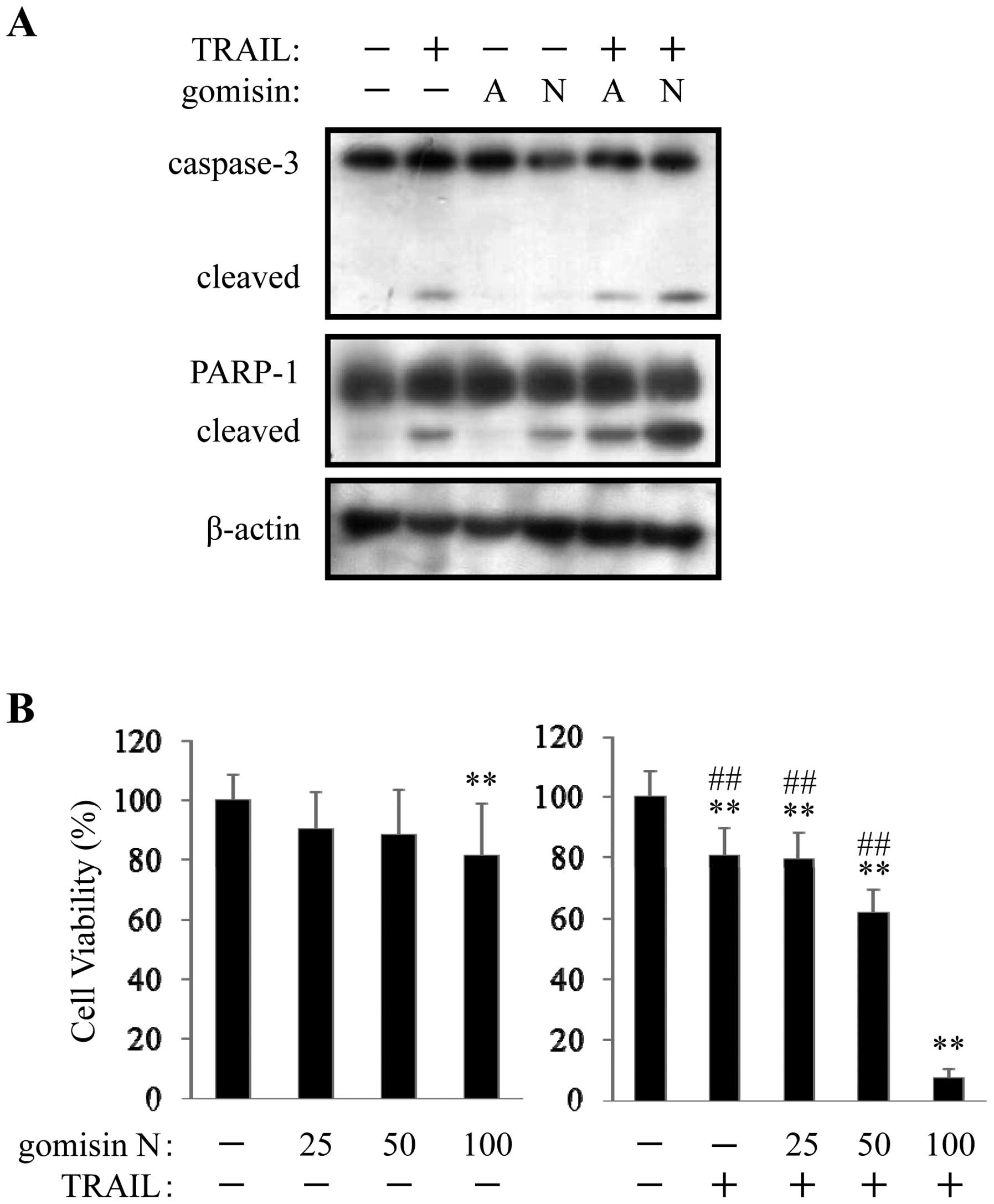

Gomisins have been shown to induce apoptosis in

cancer cells. We first confirmed the effects of gomisins A and N on

TRAIL-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Gomisin A alone did not

cause evident degradation of PARP-1, an important marker of

apoptosis, and gomisin N and TRAIL alone induced cleavage of PARP-1

weakly, however, gomisin N, but not gomisin A, significantly

enhanced TRAIL-induced cleavage of caspase-3 and PARP-1 (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, although gomisin N showed slight

inhibition at a concentration of 100 μM, gomisin N enhanced

TRAIL-induced cell death in a concentration-dependent manner. When

treated with TRAIL alone at 100 ng/ml, cleavage of PARP-1 was

detected in a time-dependent manner, and pretreatment with gomisin

N accelerated TRAIL-induced cleavage of PARP-1 (Fig. 2A). Morphological changes were also

observed after treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL together

(Fig. 2B). The flow cytogram of

Annexin V analysis is shown in Fig.

2C. For the control group, the percentage of apoptotic cells

was 4.4%. After treatment with TRAIL or gomisin N alone, the

percentage of Annexin V-positive cells was 14.7 or 10.1%,

respectively, however, after co-treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL,

the percentage of apoptotic cells markedly increased to 66.1%.

These results indicated that gomisin N enhanced TRAIL-induced

apoptosis.

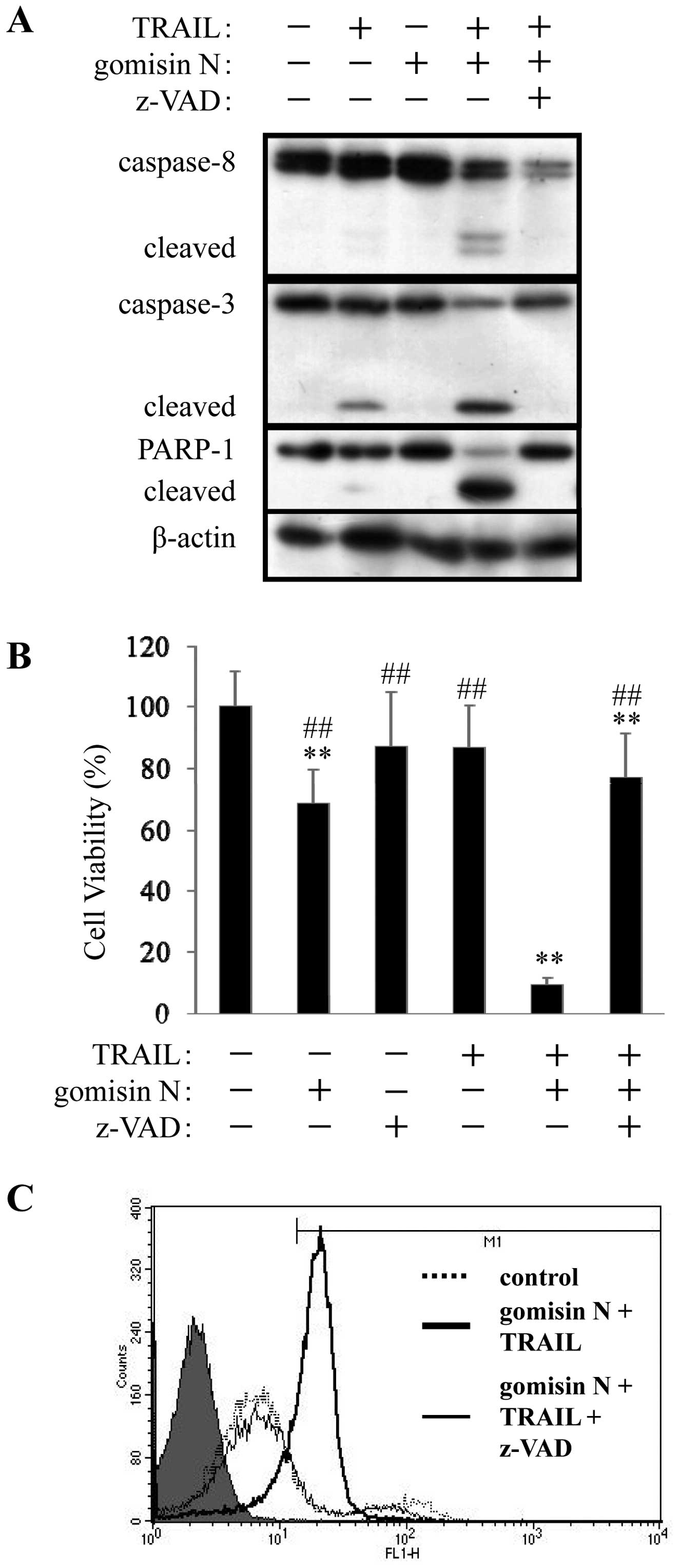

TRAIL-induced apoptosis is promoted by

gomisin N through the caspase cascade

Previous reports indicate that TRAIL-induced

apoptosis is mainly executed through the extrinsic apoptosis

pathway, involving caspase-8 and caspase-3 (20). We first examined the effect of

gomisin N on TRAIL-induced activation of the caspase cascade.

Fig. 3A shows that gomisin N alone

had no effect on the degradation of caspase-8, caspase-3 and

PARP-1, however, pretreatment with gomisin N significantly enhanced

TRAIL-induced cleavage of caspase-8, caspase-3 and PARP-1.

Moreover, pretreatment with z-VAD-FMK, a pan-caspase inhibitor,

completely inhibited cleavage of caspase-8, caspase-3 and PARP-1

(Fig. 3A). In addition, WST-1 and

Annexin V analyses showed that z-VAD-FMK also inhibited apoptosis

induced by the combined treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL

(Fig. 3B and C). These results

suggested that gomisin N was able to promote TRAIL-induced

apoptosis through the caspase cascade involving caspase-8 and

caspase-3.

Gomisin N enhances TRAIL-induced

apoptosis via up-regulation of DR4 and DR5

It is well documented that decreased expression of

TRAIL receptors DR4 and DR5 or increased expression of the decoy

receptors DcR1 and DcR2 are responsible for TRAIL resistance in

several cancer cell lines (13,20–22).

To explore the underlying mechanism by which gomisin N enhanced

TRAIL-induced apoptosis, we first detected the mRNA levels of DR4

and DR5 in HeLa cells treated with gomisin N. As shown in Fig. 4A, gomisin N significantly

up-regulated the expression of DR4 and DR5 mRNA, and the

combination of gomisin N and TRAIL accelerated the expression of

DR4 and DR5. Furthermore, although TRAIL did not up-regulate mRNA

levels of DR4 and DR5, gomisin N up-regulated DR4 and DR5

expression in a time-dependent manner until 6 h (Fig. 4B). Next to confirm the roles of DR4

and DR5 in TRAIL-induced apoptosis, TRAIL receptors were

neutralized by anti-DR4 and DR5 blocking antibodies. As shown in

Fig. 4C, WST-1 analysis

demonstrated that DR4 blocking antibody was not able to inhibit

TRAIL-induced cell death, however, after the neutralization of DR5,

the percentage of cell viability increased to 23%. Moreover, after

neutralizing both DR4 and DR5, the percentage increased to 37%.

Western blot analysis showed that DR4 and DR5 blocking antibodies

could inhibit the degradation of caspase-8, caspase-3 and PARP-1

similarly (Fig. 4D). These results

suggested that gomisin N up-regulated DR4 and DR5 expression at the

transcriptional level, and not only up-regulation of DR5 but also

that of DR4 might be one of the mechanisms in the sensitization of

TRAIL-induced apoptosis by gomisin N.

Gomisin N up-regulates DR4 and DR5

expression by increasing ROS

It has been reported that several natural products

have ROS-generating activity and ROS are related to the

up-regulation of TRAIL receptors (23–25).

Here, we measured intracellular ROS levels treated with gomisin N.

As shown in Fig. 5A, after

treatment with TRAIL alone, the intracellular ROS level was almost

the same as that of control cells without stimulation; however,

after treatment with gomisin N, the ROS level increased

significantly and co-treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL accelerated

ROS production. Moreover, pretreatment with N-acetyl cysteine

(NAC), an antioxidant, markedly reduced ROS production (Fig. 5B) and also significantly inhibited

up-regulation of DR4 and DR5 induced by gomisin N (Fig. 5C). These findings indicated that

up-regulation of DR4 and DR5 induced by gomisin N was dependent on

ROS generation.

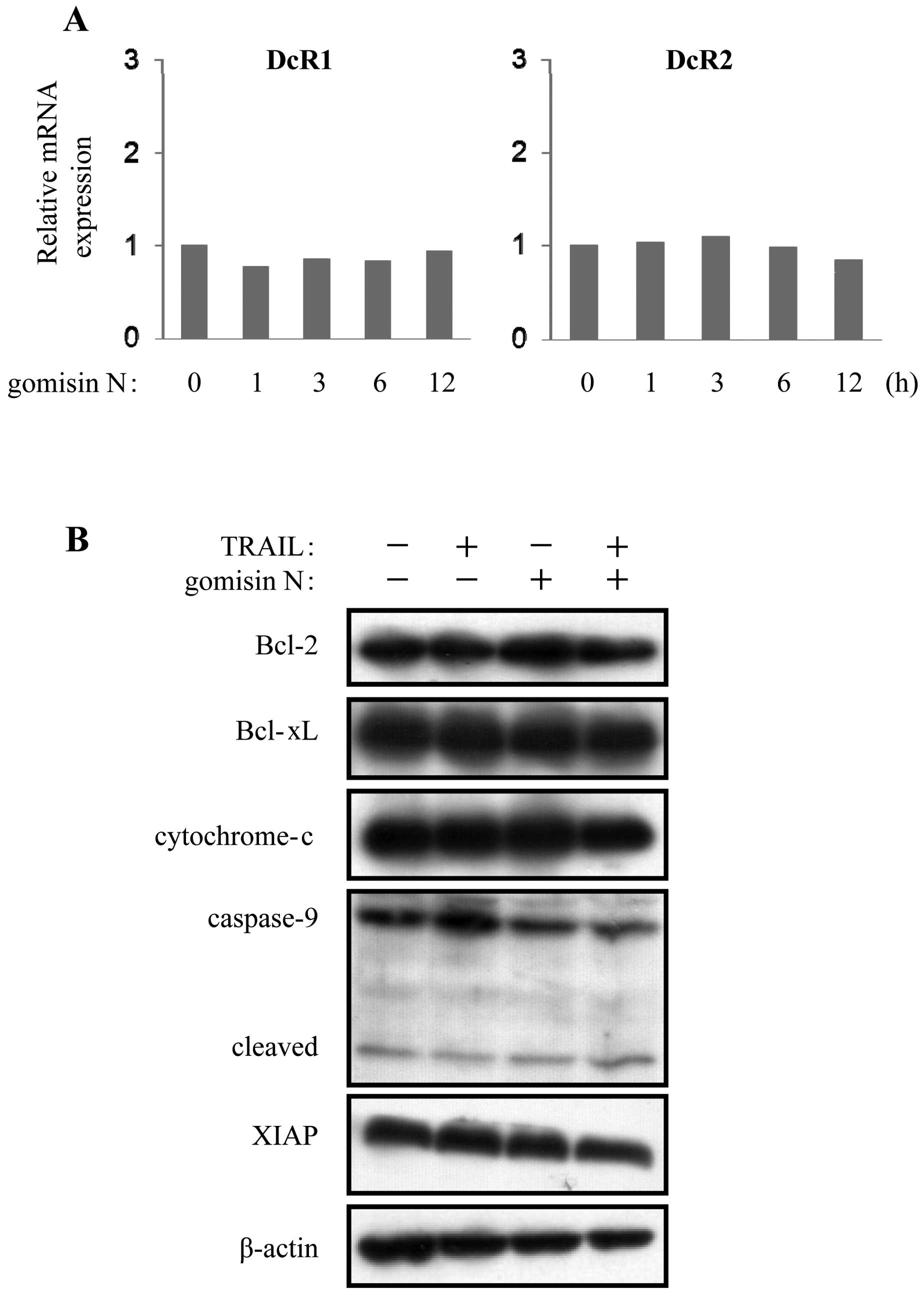

Gomisin N does not markedly affect the

mRNA expression of TRAIL decoy receptors, and protein expression of

the intrinsic apoptosis pathway

To investigate whether TRAIL decoy receptors were

relevant to the sensitization of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by gomisin

N, we examined mRNA expression of DcR1 and DcR2. As shown in

Fig. 6A, gomisin N did not change

the expression of DcR1 and DcR2. We also examined the protein

levels of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway. Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, XIAP,

cytochrome c and caspase-9 were not significantly changed by

gomisin N treatment in HeLa cells (Fig. 6B). These findings suggested that

gomisin N did not affect the mRNA expression of TRAIL decoy

receptors and the intrinsic apoptosis pathway.

Discussion

The effectiveness of chemotherapeutic drugs in

cancer treatment has been limited by systemic toxicity and drug

resistance. The distinct ability of triggering apoptosis in many

types of human cancer cells while sparing normal cells makes TRAIL

an attractive agent for cancer therapy, however, resistance to

TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells is a limitation in its

clinical application as a cancer therapeutic agent. Thus,

researchers are currently seeking TRAIL sensitizers to overcome

resistance to TRAIL in cancer cells (18). A number of chemical compounds,

including some natural products, have been identified as effective

sensitizing agents to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (23,26–36).

Gomisin N, a dibenzocyclooctadiene lignan isolated from the fruit

of S. chinensis, has been reported as an anticancer drug

candidate. Recent study demonstrated that gomisin N inhibited

proliferation and induced apoptosis in human hepatic carcinomas

(10). We have shown that gomisin

N could sensitize TNF-α-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells (11), and the findings from this study

provided substantial evidence that gomisin N was also capable of

sensitizing TRAIL-induced apoptosis in HeLa cells. Thus, this study

presents a novel anticancer effect of gomisin N and enhances the

possibility of TRAIL in clinical application.

In the present study, to explore TRAIL sensitivity

in human cervical cancer cells, HeLa cells were treated with 100

ng/ml TRAIL for 24 h. As shown in Fig.

1B, the viability of HeLa cells treated with TRAIL alone was

81%, but when treated with gomisin N (100 μM) and TRAIL, the

percentage of viability decreased significantly to 7%. Analyses of

apoptotic cells by Annexin V-FITC are shown in Fig. 2C. It was revealed that cells

induced to undergo apoptosis by TRAIL alone were only 14.7%, but

after treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL, the percentage of

apoptotic cells increased to 66.1%. These results suggested that

HeLa cells were resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis and gomisin N

could promote TRAIL-induced apoptosis. To clarify the signaling

pathway of apoptosis induced by TRAIL, we characterized the

caspase-dependent pathway. The activation of caspase-8, caspase-3

and PARP-1 confirmed that the cell death induced by gomisin N and

TRAIL was caspase-dependent apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 3, the pan-caspase inhibitor

(z-VAD-FMK) was able to prevent PARP-1 cleavage and apoptosis

induced by combined treatment with gomisin N and TRAIL, therefore,

it was clarified that the apoptosis induced by gomisin N and TRAIL

was caspase-dependent. Gomisin A enhanced the cleavage of PARP-1

induced by TRAIL slightly, but did not augment the cleavage of

caspase-3 induced by TRAIL (Fig.

1A), therefore it was necessary to investigate the molecular

mechanisms of gomisin A in enhancing the cleavage of PARP-1.

The expression level of death receptors (DR4 or DR5)

plays a key role in determining the cell fate in response to TRAIL

(20–22). There are numerous reports that the

up-regulation of DR4 or DR5 could sensitize TRAIL-resistant cells

to TRAIL-induced cell death (37,38).

In this study, we showed for the first time that gomisin N

increased DR4 and DR5 expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 4A and B). When we neutralized only

DR4 by using a blocking antibody, the percentage of cell viability

was not recovered, as compared with that of the combination of

gomisin N and TRAIL. However, pretreatment with both DR4 and DR5

blocking antibodies inhibited the cell death induced by gomisin N

and TRAIL more strongly than that of only DR5 (Fig. 4C), so we believed that both DR4 and

DR5 up-regulated by gomisin N played key roles in sensitizing HeLa

cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

ROS generation has been proposed to be involved in

the up-regulation of TRAIL receptors (23–25).

The present study revealed that the mechanism by which gomisin N

induced up-regulation of DR4 and DR5 was through the production of

ROS. The antioxidant (NAC) could abolish the up-regulation of TRAIL

receptors by gomisin N (Fig. 5C),

therefore ROS production led to the up-regulation of DR4 and DR5,

caspase cascade and eventually enhanced cell death.

In summary, we showed that gomisin N overcame TRAIL

resistance through ROS-mediated up-regulation of DR4 and DR5

expression. Gomisin N might be useful to increase TRAIL efficacy in

the treatment of malignant tumors.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid

for Challenging Exploratory Research (No. 09002374) and Scientific

Research (C) (No. 23590071) from the Ministry of Education,

Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan and a grant

from the First Bank of Toyama Foundation.

References

|

1

|

Sterbova H, Sevcikova P, Kvasnickova L,

Glatz Z and Slanina J: Determination of lignans in Schisandra

chinensis using micellar electrokinetic capillary

chromatography. Electrophoresis. 23:253–258. 2002.

|

|

2

|

He X, Lian L and Lin L: Analysis of lignan

constituents from Schisandra chinensis by liquid

chromatography-electrospray mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A.

757:81–87. 1997.

|

|

3

|

Min HY, Park EJ, Hong JY, Kang YJ, Kim SJ,

Chung HJ, Woo ER, Hung TM, Youn UJ, Kim YS, Kang SS, Bae K and Lee

SK: Antiproliferative effects of dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans

isolated from Schisandra chinensis in human cancer cells.

Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 18:523–526. 2008.

|

|

4

|

Choi MS, Kwon KJ, Jeon SJ, Go HS, Kim KC,

Ryu JR, Lee JM, Han SH, Cheong JH, Ryu JH, Shin KH and Ko CY:

Schizandra chinensis alkaloids inhibit

lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses in BV2 microglial

cells. J Biomol Tech. 17:47–56. 2009.

|

|

5

|

Oh SY, Kim YH, Bae DS, Um BH, Pan CH, Kim

CY, Lee HJ and Lee JK: Anti-inflammatory effects of gomisin N,

gomisin J, and schisandrin C isolated from the fruit of

Schisandra chinensis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 74:285–291.

2010.

|

|

6

|

Marek J and Slanina J: Gomisin N. Acta

Cryst. 54:1548–1550. 1998.

|

|

7

|

Opletal L, Sovova H and Bartlova M:

Dibenzo[a,c]cyclooctadiene lignans of the genus Schisandra:

importance, isolation and determination. J Chromatogr B Analyt

Technol Biomed Life Sci. 812:357–371. 2004.

|

|

8

|

Choi YW, Takamatsu S, Khan SI, Srinivas

PV, Ferreira D, Zhao J and Khan IA: Schisandrene, a

dibenzocyclooctadiene lignan from Schisandra chinensis:

structure-antioxidant activity relationships of

dibenzocyclooctadiene lignans. J Nat Prod. 69:356–359. 2006.

|

|

9

|

Kim SH, Kim YS, Kang SS, Bae K, Hung TM

and Lee SM: Anti-apoptotic and hepatoprotective effects of gomisin

A on fulminant hepatic failure induced by D-galactosamine and

lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Pharmacol Sci. 106:225–233. 2008.

|

|

10

|

Yim SY, Lee YJ, Lee YK, Jung SE, Kim JH,

Kim HJ, Son BG, Park YH, Lee YG, Choi YW and Hwang DY: Gomisin N

isolated from Schisandra chinensis significantly induces

antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects in hepatic carcinoma.

Mol Med Rep. 2:725–732. 2009.

|

|

11

|

Waiwut P, Shin MS, Inujima A, Zhou Y,

Koizumi K, Saiki I and Sakurai H: Gomisin N enhances TNF-α-induced

apoptosis via inhibition of the NF-κB and EGFR survival pathways.

Mol Cell Biochem. 350:169–175. 2011.

|

|

12

|

Mahmood Z and Shukla Y: Death receptors:

targets for cancer therapy. Exp Cell Res. 316:887–899. 2010.

|

|

13

|

Wu GS: TRAIL as a target in anti-cancer

therapy. Cancer Lett. 285:1–5. 2009.

|

|

14

|

Ashkenazi A, Pai RC, Fong S, Leung S,

Lawrence DA, Marsters SA, Blackie C, Chang L, McMurtrey AE, Hebert

A, DeForge L, Koumenis IL, Lewis D, Harris L, Bussiere J, Koeppen

H, Shahrokh Z and Schwall RH: Safety and antitumor activity of

recombinant soluble Apo2 ligand. J Clin Invest. 104:155–162.

1999.

|

|

15

|

Shankar S and Srivastava RK: Enhancement

of therapeutic potential of TRAIL by cancer chemotherapy and

irradiation: mechanisms and clinical implications. Drug Resist

Updat. 7:139–156. 2004.

|

|

16

|

Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney

A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Ramakrishnan L, Gray CL, Baker K, Wood

WI, Goddard AD, Godowski P and Ashkenazi A: Control of

TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy

receptors. Science. 277:818–821. 1997.

|

|

17

|

MacFarlane M: TRAIL-induced signalling and

apoptosis. Toxicol Lett. 139:89–97. 2003.

|

|

18

|

Zhang L and Fang B: Mechanisms of

resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Gene Ther.

12:228–237. 2005.

|

|

19

|

Fandy TE and Srivastava RK: Trichostatin A

sensitizes TRAIL-resistant myeloma cells by downregulation of the

antiapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

58:471–477. 2006.

|

|

20

|

LeBlanc HN and Ashkenazi A: Apo2L/TRAIL

and its death and decoy receptors. Cell Death Differ. 10:66–75.

2003.

|

|

21

|

Wang S and El-Deiry WS: TRAIL and

apoptosis induction by TNF-family death receptors. Oncogene.

22:8628–8633. 2003.

|

|

22

|

Takeda K, Stagg J, Yagita H, Okumura K and

Smyth MJ: Targeting death-inducing receptors in cancer therapy.

Oncogene. 26:3745–3757. 2007.

|

|

23

|

Zhou J, Lu GD, Ong CS, Ong CN and Shen HM:

Andrographolide sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis

via p53-mediated death receptor 4 up-regulation. Mol Cancer Ther.

7:2170–2180. 2008.

|

|

24

|

Taniguchi H, Yoshida T, Horinaka M, Yasuda

T, Goda AE, Konishi M, Wakada M, Kataoka K, Yoshikawa T and Sakai

T: Baicalein overcomes tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance via two different

cell-specific pathways in cancer cells but not in normal cells.

Cancer Res. 68:8918–8927. 2008.

|

|

25

|

Prasad S, Ravindran J, Sung B, Pandey MK

and Aggarwal BB: Garcinol potentiates TRAIL-induced apoptosis

through modulation of death receptors and antiapoptotic proteins.

Mol Cancer Ther. 9:856–868. 2010.

|

|

26

|

Li X, Wang JN, Huang JM, Xiong XK, Chen

MF, Ong CN, Shen HM and Yang XF: Chrysin promotes tumor necrosis

factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) induced

apoptosis in human cancer cell lines. Toxicol In Vitro. 25:630–635.

2011.

|

|

27

|

Lee DH, Rhee JG and Lee YJ: Reactive

oxygen species up-regulate p53 and Puma; a possible mechanism for

apoptosis during combined treatment with TRAIL and wogonin. Br J

Pharmacol. 157:1189–1202. 2009.

|

|

28

|

Ishiguro K, Ando T, Maeda O, Ohmiya N,

Niwa Y, Kadomatsu K and Goto H: Ginger ingredients reduce viability

of gastric cancer cells via distinct mechanisms. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 362:218–223. 2007.

|

|

29

|

Frese S, Pirnia F, Miescher D, Krajewski

S, Borner MM, Reed JC and Schmid RA: PG490-mediated sensitization

of lung cancer cells to Apo2L/TRAIL-induced apoptosis requires

activation of ERK2. Oncogene. 22:5427–5435. 2003.

|

|

30

|

Lee KY, Park JS, Jee YK and Rosen GD:

Triptolide sensitizes lung cancer cells to TNF-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis by inhibition

of NF-kappaB activation. Exp Mol Med. 34:462–468. 2002.

|

|

31

|

Inoue S, MacFarlane M, Harper N, Wheat LM,

Dyer MJ and Cohen GM: Histone deacetylase inhibitors potentiate

TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis in

lymphoid malignancies. Cell Death Differ. 11(Suppl 2): S193–S206.

2004.

|

|

32

|

Palacios C, Yerbes R and Lopez-Rivas A:

Flavopiridol induces cellular FLICE-inhibitory protein degradation

by the proteasome and promotes TRAIL-induced early signaling and

apoptosis in breast tumor cells. Cancer Res. 66:8858–8869.

2006.

|

|

33

|

Ganten TM, Koschny R, Haas TL, Sykora J,

Li-Weber M, Herzer K and Walczak H: Proteasome inhibition

sensitizes hepatocellular carcinoma cells, but not human

hepatocytes, to TRAIL. Hepatology. 42:588–597. 2005.

|

|

34

|

Shi RX, Ong CN and Shen HM: Protein kinase

C inhibition and x-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein

degradation contribute to the sensitization effect of luteolin on

tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced

apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65:7815–7823. 2005.

|

|

35

|

Zhang S, Shen HM and Ong CN:

Down-regulation of c-FLIP contributes to the sensitization effect

of 3,3′-diindolylmethane on TRAIL-induced apoptosis in cancer

cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 4:1972–1981. 2005.

|

|

36

|

Son YG, Kim EH, Kim JY, Kim SU, Kwon TK,

Yoon AR, Yun CO and Choi KS: Silibinin sensitizes human glioma

cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis via DR5 up-regulation and

down-regulation of c-FLIP and survivin. Cancer Res. 67:8274–8284.

2007.

|

|

37

|

Galligan L, Longley DB, McEwan M, Wilson

TR, McLaughlin K and Johnston PG: Chemotherapy and TRAIL-mediated

colon cancer cell death: the roles of p53, TRAIL receptors, and

c-FLIP. Mol Cancer Ther. 4:2026–2036. 2005.

|

|

38

|

Jin Z, McDonald ER III, Dicker DT and

El-Deiry WS: Deficient tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) death receptor transport to the

cell surface in human colon cancer cells selected for resistance to

TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 279:35829–35839. 2004.

|