Introduction

Tumor hypoxia is prognostic for poor response to

cancer therapy. The prognostic value of tumor hypoxia has been

demonstrated in radiotherapy studies of human head and neck

(1,2) and uterine cervix (3) tumors, which show that patients with

less hypoxic tumors had a better chance of overall or disease-free

survival than did patients with more hypoxic tumors. Furthermore,

some chemotherapeutic agents such as bleomycin and doxorubicin

exhibit a cytotoxicity that is strongly oxygen dependent,

suggesting that hypoxia may be a prognostic factor for

chemotherapeutic response as well (4–6).

Therefore, development of methods allowing measurement of hypoxia

in human patients may allow physicians to better manage tumors that

exhibit considerable hypoxia.

Ilangovan et al demonstrated in tumor-bearing

mice that carbogen breathing increased the oxygenation in the

tumor, and that this increased oxygenation was related to a

decreased rate of nitroxide reduction (7). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can

accurately measure nitroxide reduction rates (8,9),

suggesting that nitroxide contrast agents could serve as an

MRI-based assessment of tumor oxygenation. Although the study by

Ilangovan showed that nitroxides were sensitive to oxygenation

changes during carbogen breathing, another use of nitroxides would

be to detect hypoxia in tumors (7). In this case, it is expected that

hypoxia will have the opposite effect of carbogen on the rate of

nitroxide reduction. Namely, it is expected that greater hypoxia

will be associated with a greater rate of nitroxide reduction.

The purpose of this study was to test if there is a

relationship between the reduction rate of Tempol as measured with

MRI and the hypoxic fraction of a tumor. The hypoxic fraction of

the tumor was measured using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)

imaging and the triarylmethyl (TAM) spin probe Oxo63 and the

reduction rate of Tempol was measured with a 7T small animal MRI

scanner.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

The triarylmethyl (TAM) radical Oxo63 was obtained

from GE healthcare. Tempol

(4-hydroxy-2,2,6,6,-tetramethyl-1-piperidynyloxyl) was purchased

from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Animals

C3HHenCrMTV- mice were obtained from the Frederick

Cancer Research Center, Animal Production (Frederick, MD, USA).

Mice were housed in a climate controlled circadian rhythm adjusted

room and were allowed access to food and water ad libitum.

The body weight of the mice at the time of imaging was 22–30 g.

SCCVII (murine squamous cell carcinoma) cells (2–3×105)

were injected 7–15 days before imaging. Experiments were carried

out in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animal Resources (National Research Council, 1996) and approved by

the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Animal experiment protocol

Starting 7 days after injection of SCCVII cells,

mice were imaged every 1–2 days. For anesthesia during imaging, a

mixture of isofluorane (4% to induce, 1–2% to maintain) and medical

air (750 ml/min) was blown into a nose-cone fitted to the animal’s

head. For EPR measurements, the mouse was placed on a platform with

its legs hanging downward into a vertical coil. For MRI

measurements, the mouse was placed on a cradle, which was then

placed inside the horizontal bore of the magnet. For both EPR and

MRI experiments, a pressure transducer (SA Instruments Inc.) was

used to monitor the breathing rate, and a rectal thermocouple was

used to monitor the core body temperature. Warm air was blown over

the mouse to maintain its temperature. The breathing rate was kept

at 60±10 breaths per min and the body temperature was maintained at

37±1°C. To enable injection of contrast agents during imaging, a

catheter was made by inserting a 30.5-gauge needle tip into

polyethylene (PE-10) tubing. Using this catheter, the tail vein of

the mouse was cannulated. Oxo63 (10 μl/g body weight of 75

mM solution) or Tempol (5 μl/g body weight of 150 mM

solution) was manually injected through the catheter.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic Resonance Imaging was performed using a 4.7

Tesla small animal scanner (Bruker Bio-Spin MRI GmbH). After a

survey scan, T2-weighted images were obtained using multi-slice

multi-echo (MSME) sequence with a 10-echo train and an echo time of

15 min. SPGR (also referred as gradient echo fast imaging, GEFI)

(TR=75 ms, TE=3 ms, FA=45°, NEX=2) was employed to observe T1

effect. The scan time for 6 slices with the SPGR sequence was 20

sec. Other common image parameters are as follows; image resolution

was 256 x 256, FOV was 3.2 x 3.2 cm, slice thickness was 2.0 mm.

Number of slices was 6.

EPR oximetry

A pulsed (time domain) EPR imaging scanner was used

to measure tissue pO2. Details of this method are

described elsewhere (10).

Briefly, Oxo63 is injected into the mouse via tail vein catheter.

Imaging was initiated once the EPR signal intensity reached a

steady state value, indicating that the Oxo63 radical had reached a

steady state concentration in the tissue. pO2 mapping

relies on the linear relationship between the pO2 of the

tissue and linewidth of the TAM radical (Oxo63.) To quantify the

linewidth in a voxel, several images with increasing readout delay

are obtained. As the readout delay increases, the signal decreases

in a manner that depends on the linewidth of the voxel. From the

images with successively increasing readout delay, the linewidth of

oxo63 is mapped over the tissue region. Finally, using the

linewidth map, the pO2 is calculated from a calibration

curve calculated in vitro. EPR imaging was performed in a

300 MHz single point-imaging scanner. The imaging parameters were

as follows: excitation pulse, 80 ns, 80 W; TR, 5.5 μs; flip

angle, 70°C; field gradient, 0.8 Gauss/cm, 1.0 Gauss/cm, 1.2

Gauss/cm; no. of gradient steps, 21 x 21, number of averages,

100,000.

Statistical analyses

The statistical differences were estimated with

TTEST function in the Microsoft Excel XP. The suitable ‘type’ for

the test was selected according to the correspondence and variance

of the data. Significances were estimated when p-value was less

than 0.05.

Results

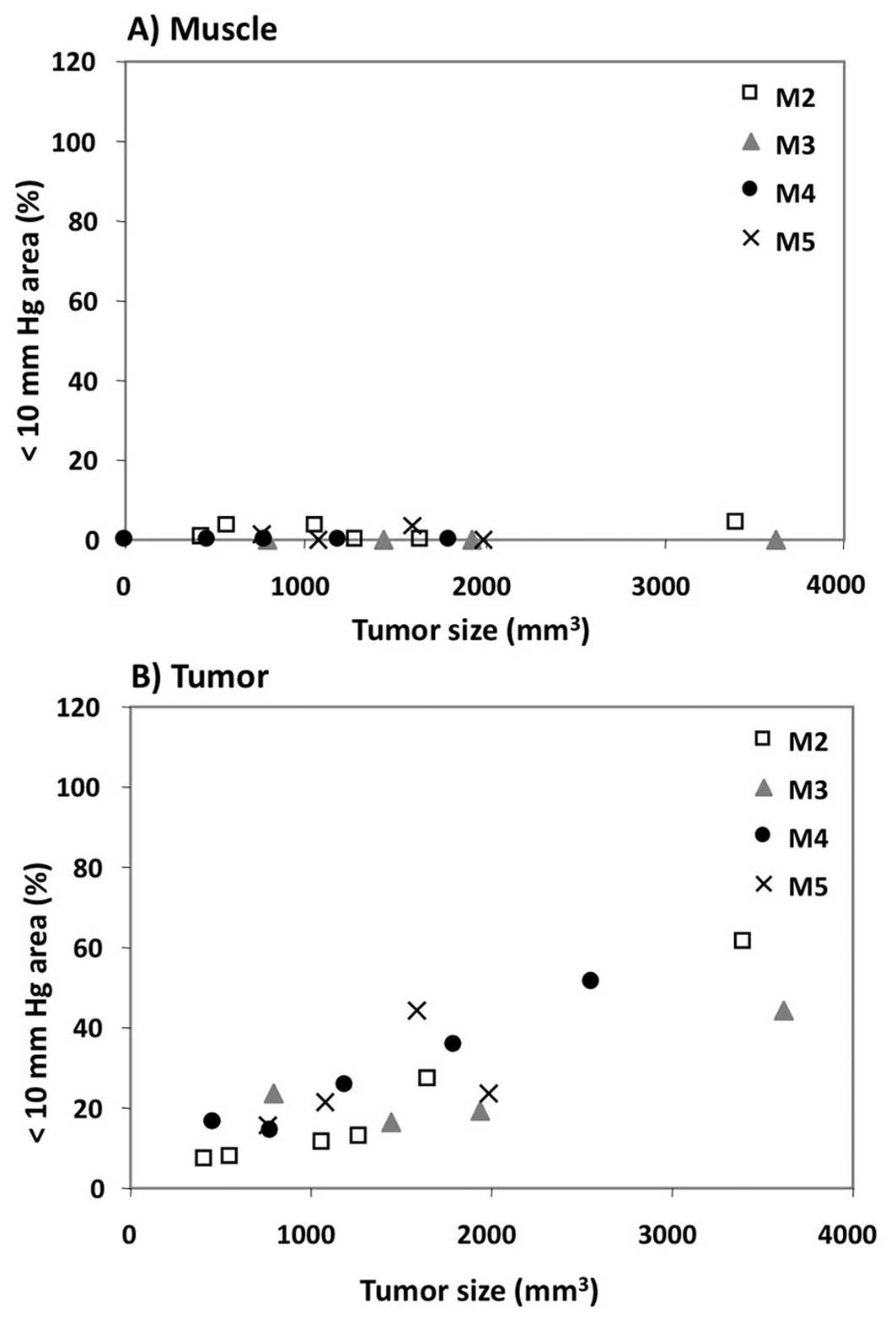

The growth of the SCCVII tumor as a

function of time after implantation (Fig. 1A)

Between days 7 and 15, the volume of the tumor

increased linearly with time from 500 to 3,500 mm3.

Fig. 1B shows representative

EPR-based pO2 maps (bottom panels) obtained at 8 and 12

days after tumor implantation. Comparison of the MRI T2-weighted

images (top panels) at day 8 and day 12 clearly shows increase in

tumor size with time. The pO2 maps overlaid with the MRI

scans show significant hypoxia regions (black and blue areas on the

images) within the tumor by day 12. The pO2 maps as

shown in Fig. 1B were converted

into histograms and representative histograms for a representative

mouse on days 7 and 15 are displayed in Fig. 2. These histograms show that over

the course of the study, a slight 3 mmHg decrease in median

pO2 was observed in the muscle, while a marked 8 mmHg

decrease in median pO2 was observed in the tumor. To

test if the hypoxic fraction of the tumor changed as the tumor

grew, the percentage of tumor volume with pO2 less than

10 mmHg (i.e., the hypoxic fraction) was plotted as a function of

tumor size (Fig. 3). Between days

7 and 15 of the study, the hypoxic fraction of the muscle remained

well below 5%. In contrast, the hypoxic fraction of the tumor

increased linearly as the tumor progressed, reaching approximately

50% by the end of the study. Taken together with the data from

Figs. 1 and 2, these results strongly suggest that

growth of the SCCVII tumor correlates with the development of

hypoxic regions within the tumor.

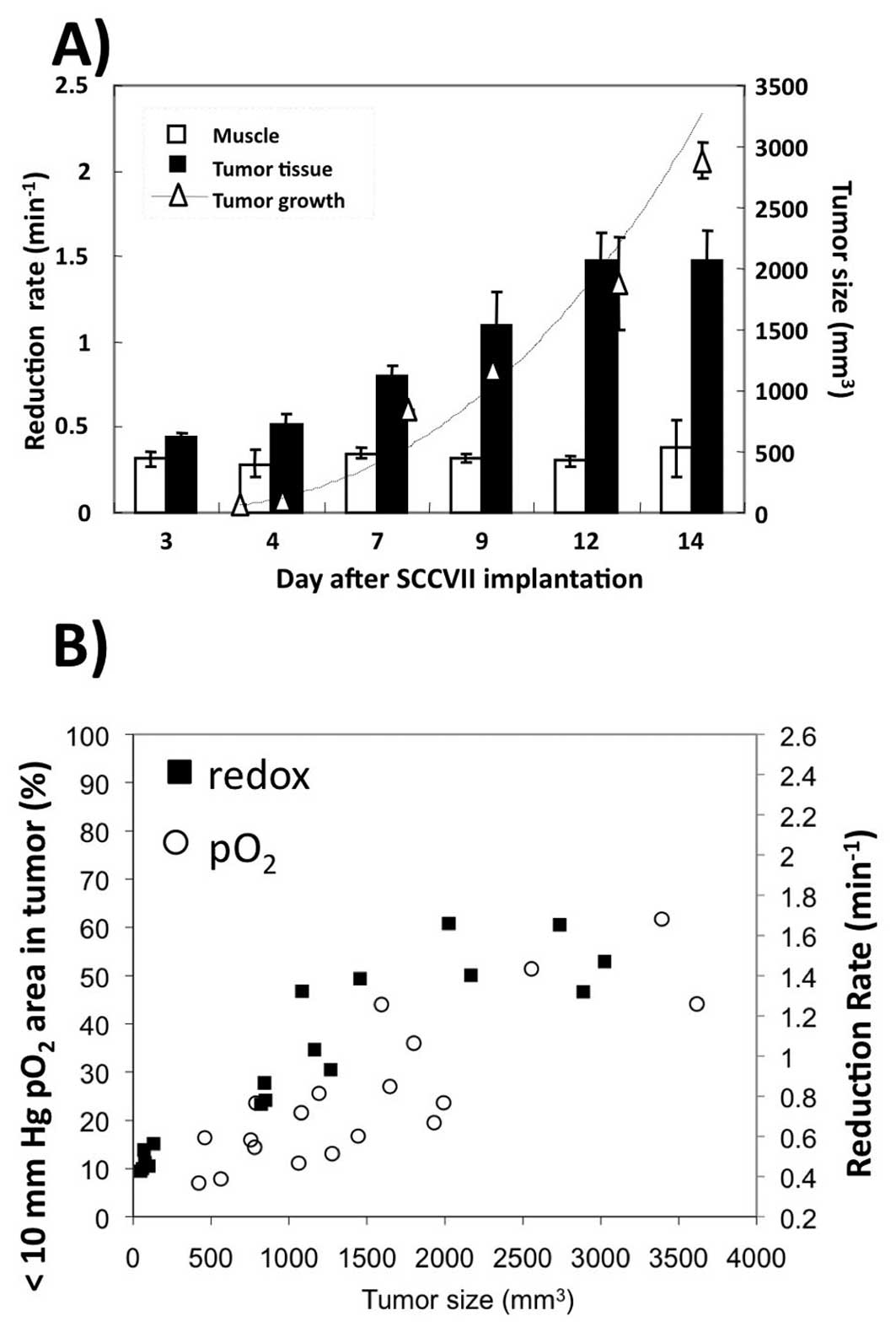

The redox status of the tissue was

monitored using Tempol as a redox-sensitive magnetic resonance

imaging contrast agent

Fig. 4 shows a

representative redox data set for a mouse taken at days 7 and 14

after tumor implantation. Fig. 4A

shows T2-weighted images of the tumor region, with regions of

interest (ROI) outlined with yellow lines for muscle and tumor.

ROIs were used to calculate the rate of Tempol reduction. Fig. 4B shows the observed signal

enhancement 40 sec after Tempol injection. On both days 7 and 14,

the rate of Tempol reduction was greater in tumor tissue than in

muscle. As the tumor grew in size, the rate at which muscle reduced

Tempol did not appreciably change, while the rate at which the

tumor reduced Tempol more than doubled. Fig. 5A summarizes the changes in tumor

volume and Tempol reduction rates for 4 mice. As the tumor volume

increased, the rate at which the tumor reduced Tempol also

increased. As for muscle, Tempol reduction essentially the same

over the 14 days. Finally, the rate of Tempol reduction and the

hypoxic fraction of a SCCVII tumor were plotted as a function of

tumor size as shown on Fig. 5B.

This graph shows that larger tumors have hypoxic fractions ranging

from 40%–60% and reduction rates varying from 1.2–1.6

min−1, while smaller tumors have hypoxic fractions of

only 5–20% and reduction rates of only 0.4–0.6 min−1.

This comparison suggests that the rate of Tempol reduction and the

hypoxic fraction of a tumor were positively correlated.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine if the

hypoxic fraction of a SCCVII tumor correlated with the rate of

Tempol reduction in the tumor. It was found that both the rate of

Tempol reduction as well as the hypoxic fraction (the fraction of

voxels with less than 10 mmHg) increased as the tumor grew

(Fig. 5B). This implies a

correlation between the rate of Tempol reduction and the hypoxic

fraction. Because high tumor hypoxia predicts a decreased

likelihood of survival during clinical cancer therapy (1–3), the

data from the current study suggest that rapid Tempol reduction may

be indicative of a poor prognosis for cancer therapy.

In this study, it was noted that the tumor hypoxic

fraction generally increased as the tumor size increased, in

agreement with other published studies (11,12).

Early studies showing a relationship between tumor size and hypoxic

fraction used a radiobiological assay of hypoxia (11). One of the most common

radiobiological assays of hypoxia involves performing an in

vivo/in vitro colony-forming assay on two experimental

groups: mice breathing ambient air, and mice asphyxiated with

nitrogen gas. The hypoxic fraction is calculated from the

difference in cell survival between the air breathing group and the

asphyxiated hypoxic group. Using assays such as these, it was

generally found that in a variety of tumors weighing less than a

gram, larger tumors exhibited more hypoxia than smaller tumors

(11,13–15).

In the case of KHT sarcomas, it was noted that tumors larger than

0.7 g did not show a further increase in hypoxic fraction,

indicating that some tumors may reach a plateau in their hypoxic

fraction (14). In contrast with

these studies, studies with both a rhabdosarcoma (16) and in a 9L line (17) were not able to show a dependence of

hypoxic fraction on tumor size. Later studies used an invasive

polargraphic needle electrode to assess the dependence of hypoxic

fraction on tumor size. These studies found that in OCa-I, MCa-r,

KHT, C3H mammary carcinoma and SCCVII tumors with weights ranging

from 0.15 to 1.5 g, the hypoxic fraction increased as the tumor

grew (18–20). In the case of SCCVII (also used in

this study), polarographic oxygen measurements showed that the

hypoxic fraction (defined in that study as % volume with

pO2 <5 mmHg) ranged from approximately 50 to 100% as

the tumor grew from 150 mm3 to 1,500

mm3(20). These

measurements report hypoxia fractions greater than observed in the

present study, where the hypoxic fraction (defined in this study as

% volume with pO2 <10 mmHg) was found to increase

from 10 to 50% as the tumor grew from 500 mm3 to 3,500

mm3. In summary, most of the literature is consistent

with the current finding that implanted animal tumors weighing less

than a few grams exhibit an increased hypoxic fraction as the

tumors grow.

Although most murine tumors exhibit a dependence of

hypoxic fraction on tumor size, there are data suggesting that in

the case of human tumors, the situation is more complex. Using

F-MISO PET, hypoxia was measured in tumors of 12 patients with

non-small cell lung cancer, where the tumor size ranged from 50

cm3 to 350 cm3(21). In this study, no dependence of

hypoxic fraction on tumor size was observed. In other studies in

human uterine cervix cancers (22)

and squamous cell carcinoma metastasis (23), hypoxia was measured using a

polarographic needle. Again, no dependence of hypoxic fraction on

tumor size was observed in either of these studies. Although these

data are limited, they suggest that tumor size is not a valid

single surrogate marker for hypoxia in the clinical setting. It is

not completely clear why animal tumors exhibit a size-dependent

hypoxia relationship and human tumors do not, but the difference

may be related to the relative volume of murine versus human

tumors. In general, the human tumors were at least 5 g (assuming

water density) (11,13,14),

indicating that by the time human tumors are observed in the

clinic, they may have surpassed a threshold for size-hypoxia

dependence. Indeed, the hypoxic fraction cannot increase

indefinitely, and murine KHT sarcomas exhibited a plateau in

hypoxia above a weight of 0.7 g (14). Because tumor size, which is

commonly measured during routine clinical scans, is apparently a

poor marker for tumor hypoxia, novel biological imaging techniques

must be developed in order to assess tumor hypoxia in humans.

During this study, it was observed that tumor

hypoxia and the rate of Tempol reduction both increased as the

tumor grew. The question remains if the increasing hypoxia observed

during tumor growth actually caused Tempol to be reduced more

quickly. In theory, it is possible that low oxygen levels in a

tumor will result in a more reductive tumor microenvironment, and

an important example involves the NADPH/NADP+ redox pair

(24). NADPH is an endogenous

antioxidant, and its oxidation is catalyzed by an enzyme called

NADPH oxidase (NOX) in a reaction that requires molecular oxygen.

Furthermore, NADPH oxidase is overexpressed in some cancers

(25), including SCC (26) (used in this study), implying that

NOX activity may have affected NADPH levels in the tumor models

used during this study. NADPH, in turn, is coupled to the reduction

of GSSG to glutathione, which is the most abundant endogenous

anti-oxidant. Thus, oxygen levels directly and indirectly may

affect the intracellular levels of NADPH and GSH, both of which in

turn affect the rate of Tempol reduction (7,27–30).

Hypoxia may therefore cause the cellular milieu to become more

reduced, which would result in a high rate constant for Tempol

reduction.

Although increasing hypoxia may cause the

intracellular environment to become more reduced through the

mechanisms described above, those effects alone cannot account for

the large increase in tumor redox observed in the current study. To

put in perspective the findings of this study, it is useful to cite

in vitro studies showing that compared to tumor cells

exposed to 160 mmHg oxygen, cells exposed to 0 mmHg oxygen exhibit

a 20–160% greater reduction rate constant (31,32).

Furthermore, in a RIF-1 tumor, it was found that the tumor

pO2 varied between 2.5–15 mmHg, but that the correlation

between the nitroxide reduction rate constant and pO2

was weak (r=0.357) (33). It

therefore seems unlikely that a small change in median

pO2 of 5 mmHg would result in a 100% increase in the

reduction rate constant due only to the mechanisms described in the

previous paragraph. These considerations suggest that the rapid

Tempol reduction observed during this study may be due to factors

more complex than simple accumulation of oxygen-dependent

antioxidants due to low levels of molecular oxygen.

An alternative explanation of the apparent

correlation between the hypoxic fraction and the rate of Tempol

reduction observed in the current study could be a hypoxia-induced

shift to glycolytic metabolism. Under conditions of hypoxia,

signaling molecules such as hypoxia inducible factors (HIFs) become

relatively abundant in the cellular milieu. The most commonly

studied hypoxia inducible factor, HIF-1, is known to activate

glycolytic enzymes and genes, thereby increasing glycolytic

metabolism (34–36). Recently, glycolytic metabolism has

been shown to provide resistance to H2O2

toxicity, decrease production of reactive oxygen species, and

decrease the extent of oxidized DNA fragments. In other words,

glycolytic metabolism has been shown to evoke an antioxidant

response (34–36). Although the mechanism for this

antioxidant response is not yet fully understood, it may also

contribute to the more reductive tumor environment that was

observed in this study.

In this study, it is observed that both hypoxia and

the rate of nitroxide reduction increased as the tumor grew,

suggesting that hypoxia and the rate of nitroxide reduction are

correlated. Due to the prognostic value of hypoxia, this suggests

that rapid nitroxide reduction may indicate poor response to cancer

therapy. In conclusion, nitroxides such as Tempol may provide a

clinically feasible magnetic resonance imaging based assay of

hypoxia.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the

Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research,

National Cancer Institute, NIH.

References

|

1.

|

M NordsmarkSM BentzenV RudatD BrizelE

LartigauP StadlerA BeckerM AdamM MollsJ DunstDJ TerrisJ

OvergaardPrognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck

tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international

multi-center studyRadiother

Oncol771824200510.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.03816098619

|

|

2.

|

DM BrizelRK DodgeRW CloughMW

DewhirstOxygenation of head and neck cancer: changes during

radiotherapy and impact on treatment outcomeRadiother

Oncol53113117199910.1016/S0167-8140(99)00102-410665787

|

|

3.

|

M HockelC KnoopK SchlengerB VorndranE

BaussmannM MitzePG KnapsteinP VaupelIntratumoral pO2

predicts survival in advanced cancer of the uterine cervixRadiother

Oncol2645501993

|

|

4.

|

L Roizin-TowleEJ HallStudies with

bleomycin and misonidazole on aerated and hypoxic cellsBr J

Cancer37254260197810.1038/bjc.1978.3475740

|

|

5.

|

BA TeicherJS LazoAC

SartorelliClassification of anti-neoplastic agents by their

selective toxicities toward oxygenated and hypoxic tumor

cellsCancer Res41738119817448778

|

|

6.

|

BA TeicherSA HoldenA al-AchiTS

HermanClassification of antineoplastic treatments by their

differential toxicity toward putative oxygenated and hypoxic tumor

subpopulations in vivo in the FSaIIC murine fibrosarcomaCancer

Res50333933441990

|

|

7.

|

G IlangovanH LiJL ZweierMC KrishnaJB

MitchellP KuppusamyIn vivo measurement of regional oxygenation and

imaging of redox status in RIF-1 murine tumor: effect of

carbogen-breathingMagn Reson

Med48723730200210.1002/mrm.1025412353291

|

|

8.

|

F HyodoBP SouleK MatsumotoS MatusmotoJA

CookE HyodoAL SowersMC KrishnaJB MitchellAssessment of tissue redox

status using metabolic responsive contrast agents and magnetic

resonance imagingJ Pharm

Pharmacol6010491060200810.1211/jpp.60.8.001118644197

|

|

9.

|

F HyodoK MatsumotoA MatsumotoJB MitchellMC

KrishnaProbing the intracellular redox status of tumors with

magnetic resonance imaging and redox-sensitive contrast

agentsCancer

Res6699219928200610.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-087917047054

|

|

10.

|

K MatsumotoS SubramanianN DevasahayamT

AravalluvanR MurugesanJA CookJB MitchellMC KrishnaElectron

paramagnetic resonance imaging of tumor hypoxia: enhanced spatial

and temporal resolution for in vivo pO2

determinationMagn Reson

Med5511571163200610.1002/mrm.2087216596636

|

|

11.

|

WU ShipleyJA StanleyGG SteelTumor size

dependency in the radiation response of the Lewis lung

carcinomaCancer Res352488249319751149047

|

|

12.

|

JA StanleyWU ShipleyGG SteelInfluence of

tumour size on hypoxic fraction and therapeutic sensitivity of

Lewis lung tumourBr J

Cancer36105113197710.1038/bjc.1977.160889677

|

|

13.

|

R JirtleKH CliftonThe effect of tumor size

and host anemia on tumor cell survival after irradiationInt J

Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys4395400197810.1016/0360-3016(78)90068-8689941

|

|

14.

|

RP HillAn appraisal of in vivo assays of

excised tumoursBr J Cancer (Suppl)423023919806932930

|

|

15.

|

DW SiemannTumour size: a factor

influencing the isoeffect analysis of tumour response to combined

modalitiesBr J Cancer (Suppl)429429819806932939

|

|

16.

|

HS ReinholdC De BreeTumour cure rate and

cell survival of a transplantable rat rhabdomyosarcoma following

x-irradiationEur J

Cancer4367374196810.1016/0014-2964(68)90026-15760725

|

|

17.

|

CA WallenSM MichaelsonKT WheelerEvidence

for an unconventional radiosensitivity of rat 9L subcutaneous

tumorsRadiat Res84529541198010.2307/35754917454994

|

|

18.

|

K De JaegerFM MerloMC KavanaghAW FylesD

HedleyRP HillHeterogeneity of tumor oxygenation: relationship to

tumor necrosis, tumor size, and metastasisInt J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys4271772119989845083

|

|

19.

|

AA KhalilMR HorsmanJ OvergaardThe

importance of determining necrotic fraction when studying the

effect of tumour volume on tissue oxygenationActa

Oncol3429730019957779412

|

|

20.

|

CG MilrossSL TuckerKA MasonNR HunterLJ

PetersL MilasThe effect of tumor size on necrosis and

polarographically measured pO2Acta

Oncol36183189199710.3109/028418697091092289140436

|

|

21.

|

JS RaseyWJ KohML EvansLM PetersonTK

LewellenMM GrahamKA KrohnQuantifying regional hypoxia in human

tumors with positron emission tomography of

[18F]fluoromisonidazole: a pretherapy study of 37 patientsInt J

Radiat Oncol Biol Phys3641742819968892467

|

|

22.

|

HD WeitmannB GustorffP VaupelTH KnockeR

PotterOxygenation status of cervical carcinomas before and during

spinal anesthesia for application of brachytherapyStrahlenther

Onkol179633640200310.1007/s00066-003-1060-x14628130

|

|

23.

|

RA GatenbyHB KesslerJS RosenblumLR CoiaPJ

MoldofskyWH HartzGJ BroderOxygen distribution in squamous cell

carcinoma metastases and its relationship to outcome of radiation

therapyInt J Radiat Oncol Biol

Phys14831838198810.1016/0360-3016(88)90002-83360652

|

|

24.

|

FQ SchaferGR BuettnerRedox environment of

the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione

disulfide/glutathione coupleFree Radic Biol

Med3011911212200110.1016/S0891-5849(01)00480-411368918

|

|

25.

|

IK IlonenJV RasanenEI SihvoA KnuuttilaKM

SalmenkiviMO AhotupaVL KinnulaJA SaloOxidative stress in non-small

cell lung cancer: role of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

phosphate oxidase and glutathioneActa

Oncol4810541061200910.1080/0284186090282490919308756

|

|

26.

|

M Czesnikiewicz-GuzikB LorkowskaJ ZapalaM

CzajkaM SzutaB LosterTJ GuzikR KorbutNADPH oxidase and uncoupled

nitric oxide synthase are major sources of reactive oxygen species

in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Potential implications for immune

regulation in high oxidative stress conditionsJ Physiol

Pharmacol591391522008

|

|

27.

|

A IannoneA TomasiV VanniniHM

SwartzMetabolism of nitroxide spin labels in subcellular fractions

of rat liver. II. Reduction by microsomesBiochimica Biophysica

Acta1034285289199010.1016/0304-4165(90)90052-X

|

|

28.

|

E FinkelsteinGM RosenEJ

RauckmanSuperoxide-dependent reduction of nitroxides by

thiolsBiochim Biophys

Acta8029098198410.1016/0304-4165(84)90038-2

|

|

29.

|

KI YamadaP KuppusamyS EnglishJ YooA IrieS

SubramanianJB MitchellMC KrishnaFeasibility and assessment of

non-invasive in vivo redox status using electron paramagnetic

resonance imagingActa

Radiol43433440200210.1034/j.1600-0455.2002.430418.x12225490

|

|

30.

|

P KuppusamyH LiG IlangovanAJ CardounelJL

ZweierK YamadaMC KrishnaJB MitchellNoninvasive imaging of tumor

redox status and its modification by tissue glutathione

levelsCancer Res62307312200211782393

|

|

31.

|

RM DavisS MatsumotoM BernardoA SowersK

MatsumotoMC KrishnaJB MitchellMagnetic resonance imaging of organic

contrast agents in mice: capturing the whole-body redox

landscapeFree Radic Biol

Med50459468201110.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.02821130158

|

|

32.

|

Y SamuniJ GamsonA SamuniK YamadaA RussoMC

KrishnaJB MitchellFactors influencing nitroxide reduction and

cytotoxicity in vitroAntioxid Redox

Signal6587595200410.1089/15230860477393434115130285

|

|

33.

|

K TakeshitaK KawaguchiK Fujii-AikawaM

UenoS OkazakiM OnoMC KrishnaP KuppusamyT OzawaN IkotaHeterogeneity

of regional redox status and relation of the redox status to

oxygenation in a tumor model, evaluated using electron paramagnetic

resonance imagingCancer

Res7041334140201010.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4369

|

|

34.

|

H KondohME LleonartD BernardJ

GilProtection from oxidative stress by enhanced glycolysis; a

possible mechanism of cellular immortalizationHistol

Histopathol228590200717128414

|

|

35.

|

H KondohME LleonartJ GilJ WangP DeganG

PetersD MartinezA CarneroD BeachGlycolytic enzymes can modulate

cellular life spanCancer Res65177185200515665293

|

|

36.

|

F LuoX LiuN YanS LiG CaoQ ChengQ XiaH

WangHypoxia-inducible transcription factor-1alpha promotes

hypoxia-induced A549 apoptosis via a mechanism that involves the

glycolysis pathwayBMC

Cancer626200610.1186/1471-2407-6-2616438736

|