Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is among the malignancies with the

worst patient outcome, representing the fourth most common cause of

cancer-related death in the US (1,2).

Unfortunately, at the time of diagnosis, only a minority of tumors

are restricted locally and therefore resectable, while the majority

(>85%) already shows regional or distant spread. For these late

stage tumors, systemic chemotherapy with antimetabolites such as

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) or gemcitabine is only a palliative option.

Although gemcitabine has shown improved objective response rates

over 5-FU (3) in terms of tumor

mass reduction and time to progression, most studies investigating

gemcitabine-based combinations have failed to show a statistically

significant survival benefit compared to gemcitabine alone. An

exception is the combination of gemcitabine with the tyrosine

kinase inhibitor erlotinib, for which an increase of 6% in one-year

survival rates over gemcitabine alone could be achieved. However,

the median survival improvement was merely ten days and no

statistically significant objective response rates compared to

gemcitabine monotherapy were achieved (4). The recent FOLFIRINOX study reports

median overall survival rates of about 10%, however, these rates

still lag behind achievable rates in other gastrointestinal tumors

(5). Overall, poor response rates

after single agent and combined therapies as well as the

development of chemoresistance result in a disappointing 5-year

median survival rate of 5%, a number that has not changed

significantly during the past 40 years (1,6,7).

A characteristic feature of pancreatic cancer is its

intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy, which is mediated by various

factors, such as hypovascularization, prominent desmoplasia, the

expression of drug metabolizing enzymes, and, as recent

publications suggest, the presence of putative pancreatic cancer

stem cells (8–10). The concept of organ stem cells,

slow-cycling cells with the capacity of unlimited self-renewal,

asymmetric cell division and differentiation into mature cell types

which reside in a supportive microenvironment/niche, is widely

accepted (5,9,11–15).

In the context of cancer, it implicates that cell types within a

tumor are unequal at any given time and that there is a

predetermined cell population with a stem cell phenotype, which

perpetuates the tumor while other cells of the same cancer are

incapable of self-renewal. It has also been shown that the cancer

stem cell subpopulation exhibits an enhanced resistance to

chemotherapy and radiation, both in hematologic malignancies and

solid tumors (16,17) and cell lines (18,19).

At present, however, the exact stem cell phenotype characterizing

this subpopulation of cells is not known for most solid tumors.

CD24+CD44+ESA+ or

CD133+CXCR4+ cells have been proposed to

represent this subpopulation in pancreatic cancer based on their

ability to self-renew, to effectively form xenografts in nude mice

or being able to metastasize (20). Side populations, defined as cells

that are able to exclude DNA-binding dyes such as Hoechst 33342,

have also been shown to be rich in CD133+ cells and also

express higher levels of drug-efflux pumps such as ABCG2, which

have been associated with gemcitabine resistance (21). Besides the pre-existence of

inherently resistant stem cells, several studies showed that the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is another mechanism that

is triggered when cells are challenged by cytostatic drugs

(22–24). In the context of cancer, tumor

cells of epithelial origin revert to a mesenchymal state, survive

chemotherapy and acquire an enhanced migratory and invasive

potential that might be responsible for tumor recurrence and

metastasis. Interestingly, when EMT is induced in tumor cells, not

only the presence of transformed mesenchymal cells increases, but

also the presence of cells with the above described cancer stem

cell phenotype (25). Taken

together, these studies indicate that the stem cell phenotype and

the EMT process are functionally linked and might confer resistance

to chemotherapy.

We therefore hypothesized that high-dose gemcitabine

treatment would enrich chemotherapy resistant cells which can be

identified by their expression of stem cell associated genes. Here

we investigate the expression of several known and new stem cell

markers along with EMT-associated genes in response to high-dose

gemcitabine treatment and show that surviving cells express

increased levels of stem cell genes and acquire the molecular

characteristics typical for EMT.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Panc-1 cells were grown in DMEM (Biochrom, Berlin,

Germany) substituted with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biochrom).

Capan-1 cells were maintained in RPMI (Biochrom) with 20% FBS. All

media contained 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 0.5% gentamicin

(Biochrom). Cells were grown in culture flasks (Nunc,

Langenselbold, Germany) under standard culture conditions (37°C, 5%

CO2). Medium was changed every 3 days. Passages 6 to 18

were used for all experiments. Cells tested negative for Mycoplasma

infection. Primary pancreatic cancer cells PaCaDD135, -159, -161,

-165 and -188 were established and cultured as described previously

(26,27).

Drug preparation

Gemcitabine was obtained from GRY Pharma

(Kirchzarten, Germany). Fresh stock solutions were prepared in

concentrations of 144 mM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS,

Biochrom), kept in aliquots at −20°C and diluted in medium to the

final concentrations.

Viable cell counting

Of each cell line, 105 cells/well were

seeded in 6-well plates and allowed to attach overnight. Medium was

removed, wells washed with PBS once and new medium added to the

wells, containing gemcitabine in final concentrations of 0.01 to

100 μM. Untreated controls were run in parallel. At each time-point

of analysis, cells were washed, trypsinized using trypsin/EDTA

solutions (Biochrom) and resuspended in medium. Cells were counted

after trypan blue staining in a Neubauer chamber. Experiments were

performed in triplicates.

RNA purification and reverse

transcription

For the extraction of total cellular RNA, the medium

was removed from the culture flasks and the cell layer was washed

with PBS prior to adding trypsin. The trypsinized cells were

resuspended in medium and counted. Cells (1.5x106) were

centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 10 min and the cell pellet was

subsequently used for RNA purification with RNeasy mini kit

(Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. RNA concentration was determined photometrically on

an Eppendorf BioPhotometer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). RNA (1

μg) was used for cDNA synthesis using the iScript cDNA Synthesis

kit (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany) following the manufacturer’s

instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed on a

Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich,

Germany) using SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) and QuantiTect

Primer Assays for SHH, PDX1, GLI, PTCH, SMO, NOTCH, CD24, CD44,

CD133, EpCAM, SNAI1 (Snail), SNAI2 (Slug), TWIST, OCT4, CBX7 and

GAPDH (all from Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s standard

procedure outlined in the SYBR-Green leaflet. Reaction efficiency

was determined using standard curves. Gene expression analysis was

computed using CFX Manager 2.0 (Bio-Rad) and REST 2009 (Qiagen). To

indicate the baseline expression of each gene of interest in

untreated cells, the ΔCt value was calculated as

follows: ΔCtgene of interest = Ctgene of

interest - CtGAPDH, whereby high ΔCt

values indicate low baseline expression. Changes in gene expression

comparing treated with untreated cells were computed using the

2−ΔΔCt method with GAPDH as reference gene and expressed

as efficiency corrected n-fold changes ± standard error of the mean

(SEM). Measurements were performed in triplicates. Statistical

significant changes in gene expression were assessed using the

algorithm within the REST 2009 software (28,29)

and a p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Preparation of cell blocks and cover

slips

Cell pellets were resuspended in 200 μl citrate

plasma and 200 μl Thromborel S (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics,

Deerfield, IL, USA) was added. After coagulation, cells were fixed

for 1 h in neutral-buffered saline containing 7% formalin and were

paraffin-embedded. In cases where morphology was to be preserved,

cells grown on coverslips were used. Fifty thousand cells per well

were plated in 24-well plates on round glass cover slips (Thermo

Scientific, Braunschweig, Germany), allowed to attach overnight

before treatment was performed as indicated. At each respective

time-point, cells were washed with PBS and fixed with

acetone/methanol (1:2 v/v) and stored at −20°C until

immunocytochemical staining.

Immunocytochemical staining

Cell blocks were cut into 5-μm sections and

deparaffinized using graded alcohols. Antigen retrieval was

performed by heat-induced epitope retrieval in pH 9.0 antigen

retrieval buffer (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) at 95°C for 60 min.

Endogenous peroxidase blocking was carried out for 10 min with

peroxidase-blocking reagent (Dako). Subsequently, mouse monoclonal

primary antibodies against β-catenin (1:200, Dako), E-cadherin

(1:100, NeoMarkers), vimentin (1:2000, Dako) and Ki-67 (1:500,

Dako) were applied for 30 min at RT. Primary rabbit and mouse

antibodies were detected using the EnVision Detection System

(Dako). Staining of the coverslips was performed against SHH

(rabbit monoclonal, 1:100), CD133 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:100), OCT4

(rabbit polyclonal, 1:80) and PDX-1 (rabbit polyclonal, 1:3000)

(all from Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and diluted in background reducing

antibody diluent (Dako), with Vectastain Elite ABC Kit Rabbit

(Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) adhering to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Visualization was performed using DAB

(Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Control experiments for all stainings were negative using PBS

replacement of primary or secondary antibodies and same processing

as described above. The stained slides were digitalized using the

ImageAccess 9 Enterprise software (Imagic Bildverarbeitung,

Glattbrugg, Switzerland) and percentage of positive cells evaluated

using the Cell Explorer 2006 software (BioSciTec, Frankfurt,

Germany). In addition, staining intensities were graded

semiquantitatively as negative, low, moderate and high.

In vitro wound healing (scratch)

assay

Panc-1 cells (105/well) were seeded into

6-well plates and allowed to grow to approximately 80% confluence.

One day prior to the application of the scratch, gemcitabine was

added to the wells to a final concentration of 10 μM. PBS was used

as control. After 24 h of incubation, a scratch was applied to the

cell layer across each well using a 200 μl pipette tip. The cell

layer was washed twice with PBS to remove lose cells from the

scratch margins. The wells were refilled with 2 ml of fresh medium

and gemcitabine added, except in the controls. At regular,

intervals images were taken from definite locations of the

scratches with a Nikon Coolpix 995 digital camera on a Zeiss

Axiovert 40C phase contrast inverted microscope with scattered

light illumination.

Time-lapse microscopy

Time-lapse recording was performed using the JuLi

Smart Fluorescent Cell Analyzer (PAA Laboratories, Cölbe, Germany)

under standard conditions.

RNA-interference

Gene knockdown experiments were performed in 6-well

plates using the siLentFect Lipid Reagent (Bio-Rad) and siRNA

against SHH (Hs_SSH_6, SI03080182) and control non-coding siRNA

(AllStars Negative Control, 1027280, both from Qiagen). Cells

(1.5×105/well) were seeded 1 day prior to transfection

and allowed to attach overnight. One hour prior to transfection,

the medium was replaced with fresh antibiotics-free medium

containing 1% FCS. For each well to be transfected, 3 μl siLentFect

reagent was diluted in 150 μl OptiMEM I (Life Technologies,

Darmstadt, Germany) and 3.6 μl siRNA solution in 150 μl OptiMEM.

Diluted siRNA and diluted siLentFect were mixed and incubated at

room temperature for 20 min after which they were slowly added to

the respective wells. The cells were incubated overnight, after

which they were trypsinized and used in the xCELLigence assay. A

portion of the same cells was used for determining the knockdown

efficiency by qPCR.

xCELLigence assay

Impedance-based real-time measurement of cellular

proliferation and IC50 calculation were performed on the

xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analyzer (RTCA) in designated 96-well

electrode plates (E-plates) (all from Roche Applied Science,

Penzberg, Germany) under standard culture conditions (30). The RTCA software v. 1.2 was used

for data recording, analysis of proliferation and IC50

calculation. In all experiments, 50 μl of cell-free medium was

added to each well of the E-plate and background measurement

performed. Next, 100 μl of cell suspension (104

cells/100 μl) were added to each well, measurement was started and

the cells allowed at attach and proliferate for 24 h prior to the

addition of the compound. Readings were performed every 15 min for

at least 3 days. IC50 at day 3 was determined by

incubating the cells with serial concentrations of gemcitabine

ranging from 0.001 to 10 μM. The readout as recorded by the RTCA is

expressed as a dimensionless cell index (CI) value which correlates

with cell number and size. Measurements were performed in

quadruplicates.

Results

Determination of optimal gemcitabine

concentration

Aiming to analyze only the most resistant cells, we

decided to find the optimal concentration that would allow 5% of

the cells to survive 3 days of continuous gemcitabine incubation.

By treating Capan-1 and Panc-1 cells with serial concentrations of

gemcitabine and counting surviving cells after 3 days, we

determined that 1 and 10 μM, respectively, of gemcitabine were

needed to kill 95% of the cells. After 6 days of treatment at the

indicated concentrations, surviving cells could still be observed.

Therefore, gene expression analysis was performed at time-points of

1, 3 and 6 days of continuous gemcitabine incubation in order to

capture time-dependent changes in gene expression. Capan-1 cells

still viable after day 12 of 100 μM gemcitabine could be

observed.

mRNA expression of stem cell- and

EMT-associated markers

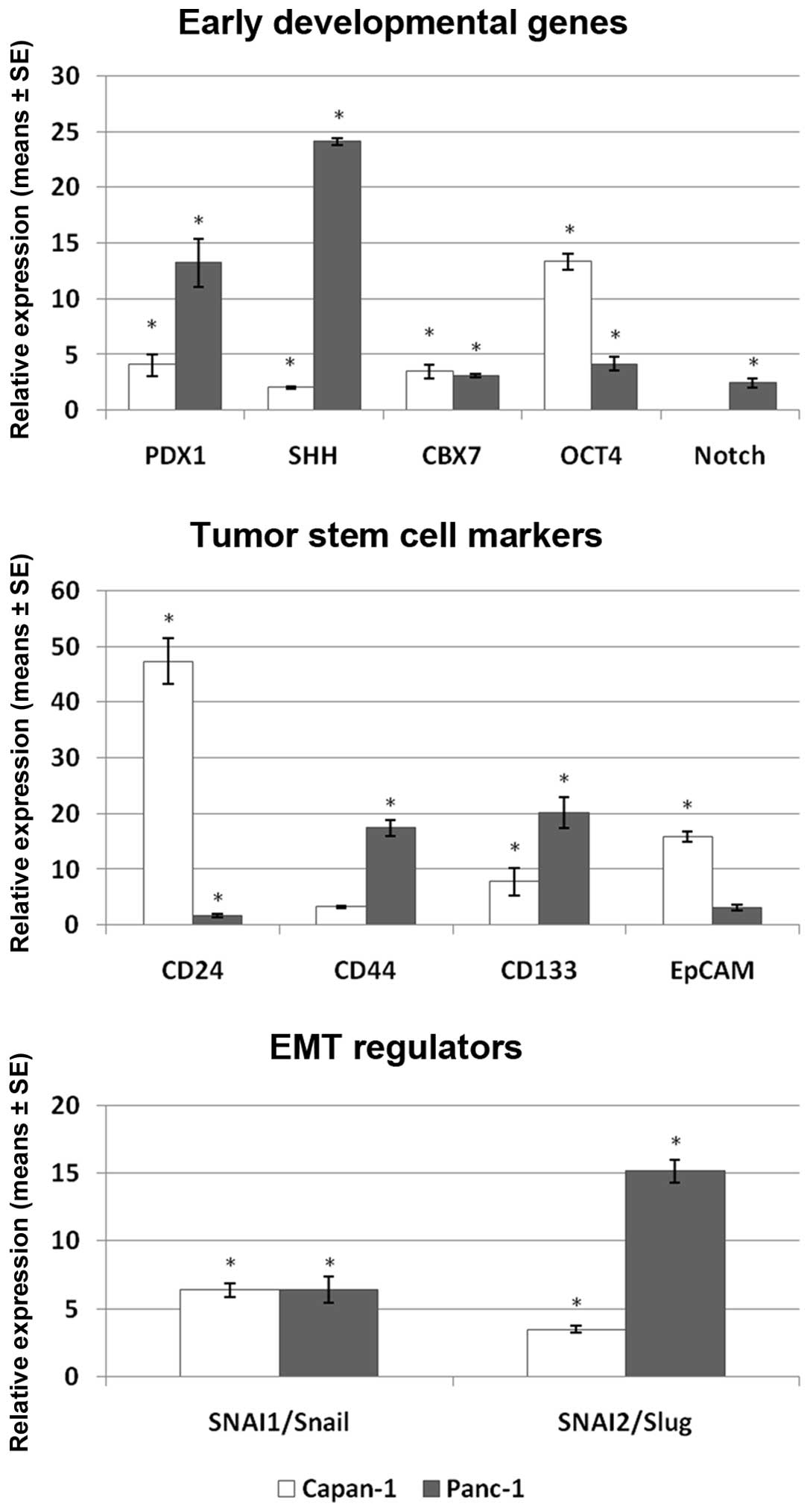

The expression of all investigated markers was

increased in the surviving cells after 6 days of continuous

incubation with gemcitabine (Fig.

1). In the group of the stem-cell associated markers, PDX1 and

SHH reached the highest expression after 6 days in Panc-1 cells

(13.4 and 24.1-fold, respectively) and PDX1 and OCT4 in Capan-1

cells (4.1 and 13.4-fold, respectively). OCT4 and PDX1 in Capan-1

and Panc-1 cells, respectively, were also the genes most strongly

induced already after 1 day of treatment (Table IA). In the group of tumor stem cell

markers, CD44 and CD133 showed the highest increase in Panc-1 (17.4

and 20.2-fold, respectively), while CD24 and EpCAM demonstrated the

highest expression in Capan-1 (47.3 and 15.9-fold, respectively).

Interestingly, genes which reached the highest expression in Panc-1

(CD44 and CD133) showed only moderate expression levels in Capan-1,

while reciprocally, the highest expressed genes in Capan-1 (CD24

and EpCAM) reached only low to moderate levels in Panc-1 cells. The

EMT regulators SNAI1/Snail and SNAI2/Slug showed a time-dependent

increase in expression in both cell lines. Snail and Slug were

induced 6.4- and 3.5-fold in Capan-1 and 6.4- and 15.2-fold in

Panc-1 cells after 6 days of continuous gemcitabine treatment.

TWIST was not detectable in either of the two cell lines. A

complete list of gene expression levels at 1, 3 and 6 days of

treatment are listed in Table

IA.

| Table IGene expression analysis in Capan-1

and Panc-1 cell lines. |

Table I

Gene expression analysis in Capan-1

and Panc-1 cell lines.

A, Gene expression

analysis of the investigated genes.a

|

|---|

| Capan-1

| Panc-1

|

|---|

| ΔCt | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 | ΔCt | Day 1 | Day 3 | Day 6 |

|---|

| PDX1 | 10.45 |

1.75±0.43 |

0.66±0.16 |

4.07±0.99 | 17.52 | 2.50±0.38 |

2.76±0.44 |

13.27±2.16 |

| SHH | 4.26 |

0.68±0.06 |

0.34±0.02 |

2.01±0.09 | 12.20 | 1.01±0.15 | 4.12±0.36 |

24.13±0.32 |

| CBX7 | 6.67 |

0.44±0.08 |

0.46±0.08 |

3.50±0.61 | 8.28 | 1.23±0.18 | 0.89±0.02 |

3.11±0.19 |

| OCT4 | 7.15 |

2.14±0.08 | 1.31±0.10 |

13.35±0.73 | 12.91 |

1.65±0.19 |

2.11±0.10 |

4.16±0.62 |

| NOTCH | | | not expressed | | 7.81 | 0.84±0.16 | 0.72±0.30 |

2.43±0.42 |

| CD24 | 6.31 | 0.56±0.05 | 6.00±0.54 |

47.33±4.11 | 4.13 |

0.75±0.13 | 0.54±0.03 |

1.71±0.31 |

| CD44 | 8.44 |

3.12±0.18 | 0.50±0.06 | 3.23±0.19 | 11.67 |

0.83±0.07 | 0.45±0.03 |

17.41±1.45 |

| CD133 | 5.22 | 1.17±0.40 | 1.20±0.38 |

7.81±2.46 | 16.72 | 1.38±0.02 |

5.23±1.60 |

20.18±2.73 |

| EpCAM | 0.30 |

0.65±0.04 |

1.79±0.16 |

15.90±0.92 | 6.78 |

1.59±0.26 |

1.85±0.10 | 3.14±0.59 |

| SNAI1/Snail | 10.30 |

0.38±0.03 |

1.43±0.19 |

6.39±0.53 | 15.93 |

1.26±0.18 | 2.29±0.23 |

6.38±0.97 |

| SNAI2/Slug | 10.71 |

0.34±0.03 | 0.65±0.05 |

3.50±0.27 | 26.54 | 1.47±0.20 | 2.45±0.39 |

15.16±0.85 |

| TWIST | | | not expressed | | | | not expressed | |

B, Gene expression

analysis in 5 primary pancreatic cancer cell lines.b

|

|---|

| PaCaDD135

| PaCaDD159

| PaCaDD161

| PaCaDD165

| PaCaDD188

|

|---|

| ΔCt | Day 3 | Day 6 | ΔCt | Day 3 | Day 6 | ΔCt | Day 3 | Day 6 | ΔCt | Day 3 | Day 6 | ΔCt | Day 3 | Day 6 |

|---|

| PDX1 | 11.24 |

2.56±0.09 | 1.44±0.11 | 11.00 | 0.98±0.02 |

1.90±0.09 | 21.06 | 0.98±0.00 | 2.15±0.10 | 19.77 |

8.92±0.37 |

8.75±0.51 | 10.47 |

0.76±0.07 |

0.70±0.03 |

| SHH | 13.26 | 2.68±0.05 | 1.65±0.15 | 11.64 | 1.33±0.02 |

1.91±0.15 | 15.59 | 1.32±0.04 | 1.05±0.12 | 12.91 |

4.08±0.33 |

2.28±0.08 | 12.01 | 1.19±0.12 | 0.91±0.05 |

| CBX7 | 9.91 |

3.23±0.09 |

1.45±0.14 | 9.70 | 1.35±0.04 |

2.97±0.12 | 11.30 |

2.04±0.02 | 2.00±0.08 | 10.76 |

9.71±0.22 | 4.25±0.20 | 10.26 | 1.14±0.11 | 1.09±0.06 |

| OCT4 | 11.10 |

3.47±0.24 | 1.86±0.14 | 11.20 | 0.98±0.30 |

1.20±0.07 | 11.23 |

1.49±0.03 |

1.41±0.07 | 8.56 |

2.08±0.10 | 1.23±0.07 | 11.25 | 1.73±0.21 | 1.87±0.09 |

| CD24 | 3.58 | 1.89±0.01 |

1.56±0.11 | 5.42 |

3.07±0.26 |

4.10±0.23 | 4.38 |

1.61±0.02 |

2.30±0.08 | 3.28 | 1.25±0.03 |

0.78±0.02 | 5.56 | 2.24±0.20 | 2.10±0.09 |

| CD44 | 12.76 | 4.24±0.05 | 2.85±0.21 | 7.59 | 0.92±0.10 | 1.59±0.35 | 9.79 | 1.05±0.08 | 0.88±0.08 | 14.60 |

1.81±0.11 |

1.42±0.20 | 7.83 | 0.36±0.04 | 0.99±0.32 |

| CD133 | 14.50 |

9.24±0.29 |

7.38±1.08 | 7.42 |

2.00±0.19 |

1.24±0.13 | 15.23 |

2.74±1.26 | 5.98±1.58 | 9.45 | 2.94±0.16 |

1.48±0.07 | 8.07 |

0.62±0.06 |

0.85±0.05 |

| EpCAM | 3.51 |

2.90±0.07 | 2.11±0.18 | 2.96 |

1.95±0.05 | 1.87±0.09 | 3.51 |

1.41±0.01 | 1.38±0.06 | 10.34 |

4.11±0.15 | 2.23±0.05 | 2.55 |

1.68±0.16 |

1.12±0.06 |

| SNAI1/Snail | 17.41 |

20.61±1.05 |

4.36±0.37 | 14.93 |

2.40±0.47 | 5.26±0.53 | 14.49 |

4.57±0.39 | 1.71±0.09 | 12.77 |

4.85±0.14 | 5.47±0.37 | 14.63 |

3.92±0.38 |

5.05±0.23 |

| SNAI2/Slug | 13.93 | 3.07±0.01 |

2.87±0.36 | 8.98 | 0.34±0.03 |

1.38±0.06 | 12.68 |

2.35±0.06 | 2.07±0.30 | 12.25 |

4.65±0.11 | 3.18±0.15 | 8.79 |

0.48±0.05 |

1.81±0.21 |

| TWIST | 23.73 |

4.04±0.89 | 1.72±0.13 | | not expressed | | 24.13 |

14.97±0.49 | 9.37±1.03 | | not expressed | | 20.46 |

39.57±8.49 |

51.72±7.01 |

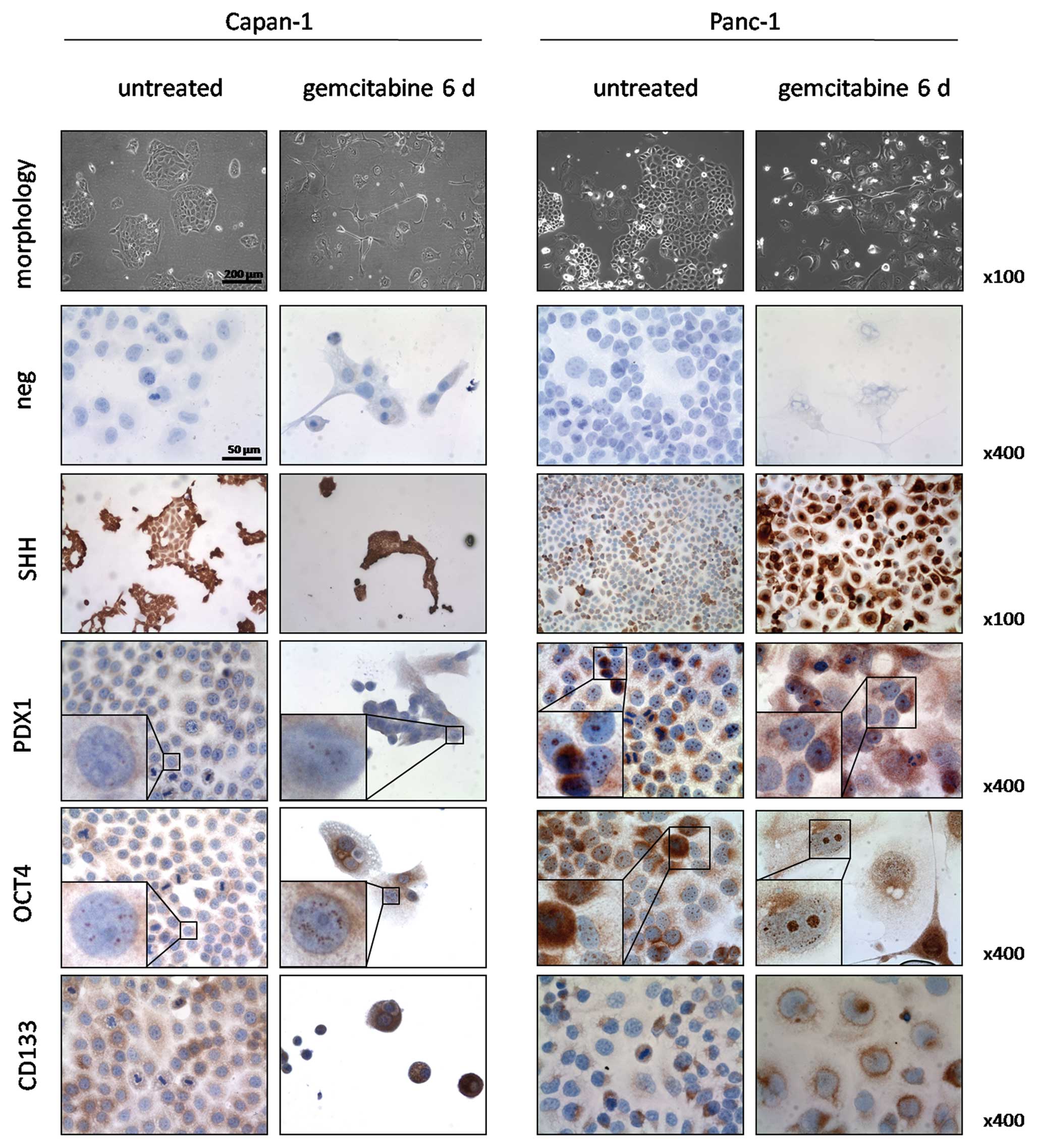

Immunocytochemical validation of gene

expression

We performed immunocytochemical stainings for SHH,

OCT4, PDX1 and CD133 in untreated cells and after 6 days of

gemcitabine incubation to confirm the qPCR results (Fig. 2). Both untreated and treated

Capan-1 cells expressed SHH in 100% of the cells. However, the

gemcitabine treated cells showed a stronger staining intensity. Of

note was that small colonies and single cells showed a stronger

expression in contrast to larger colonies in both untreated and

treated cells. PDX1 was nuclearly expressed in 30% of untreated

Capan-1 cells and increased in foci number and intensity of

staining in the nuclei of treated cells. OCT4 stained positive in

granular fashion within the nuclei of 100% of untreated cells and

to a greater extent both in number of foci and intensity in the

treated cells. CD133 was expressed in 50% of the untreated Capan-1

cells at low to moderate intensities. Occasionally, strong staining

intensities were observed in singular cells or groups of 4–10

cells. In the treated group, all cells stained positive for CD133

and staining intensity reached moderate to high levels.

In untreated Panc-1 cells, SHH was expressed in 40%

of the cells in moderate to strong staining intensity and these

cells were arranged in groups. After gemcitabine incubation, 90% of

the cells showed strong staining intensity. Nuclear staining for

PDX1 was observed in 100% and cytoplasmic staining in 20% of

untreated Panc-1 cells. Treatment increased the number of nuclear

foci, accompanied by a cytoplasmic reaction in 90% of the cells.

Granular OCT4 positivity was observed in 100% of the nuclei of both

untreated and treated cells and in the cytoplasm and perinuclear

region of 30% of cells. Treatment with gemcitabine led to an

increase in nuclear foci along with stronger staining intensities.

CD133 was positive in 30% of untreated cells and expressed in a

polar pattern with weak to moderate intensities. After treatment,

70% of the cells stained positive and CD133 was localized in the

perinuclear region.

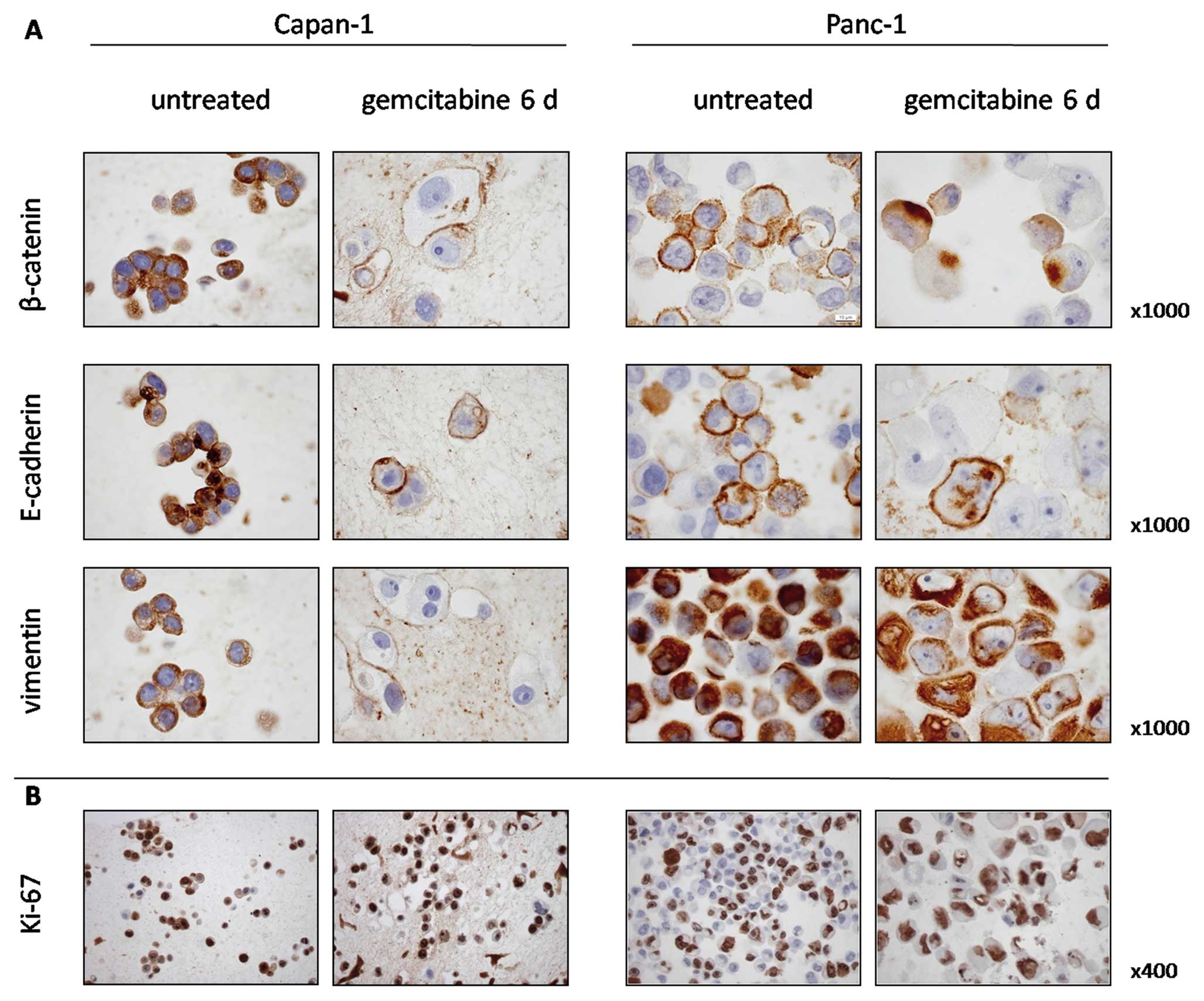

Validation of EMT

We demonstrated an induction of EMT markers by qPCR

in Panc-1 and to a lesser extent also in Capan-1 cells after 6 days

of gemcitabine treatment. We therefore investigated β-catenin and

E-cadherin expression, and 40–50% of the untreated Panc-1 cells

expressed β-catenin and E-cadherin on the cell membranes (Fig. 3A). Continuous incubation with

gemcitabine for 6 days resulted in a marked nuclear translocation

of β-catenin and repression of membranous E-cadherin. Similar but

less distinct patterns were observed in Capan-1 cells. Expression

of vimentin, considered a marker of immature and mesenchymal

phenotypes, was prominent in untreated Panc-1 cells and gemcitabine

incubation did not further increase its expression. In Capan-1

cells, vimentin was present in untreated cells, while,

interestingly, most cells showed a decrease in vimentin expression

after gemcitabine incubation.

To determine if the surviving cells retained their

proliferative capacity, Ki-67 was used to identify the cells

undergoing DNA replication. Ki-67 expression was present in 86% of

untreated Capan-1 cells and in 95% of the surviving cells after

gemcitabine incubation. In untreated Panc-1 cells, 46% were Ki-67

positive and 86% after gemcitabine incubation (Fig. 3B).

Wound healing assay

EMT is associated with loss of cell-cell adhesions

and increased cell migration. We therefore performed a wound

healing assay to assess cell migration in the gemcitabine treated

Panc-1 cells, which showed the quickest and highest induction of

Snail and Slug. Wound closure was achieved after 3.5 days after

scratch application (corresponding to day 4.5 of gemcitabine

treatment) due to an increased cell migration (Fig. 4). In contrast, the wound in the

untreated cells was still clearly visible at this time. These

findings were confirmed by time-lapse microscopy showing an

increased undirected migration in treated cells starting from day 2

of treatment, while untreated controls showed little movement

throughout the observation period (not shown).

siRNA mediated downregulation of SHH

The expression of SHH after 6 days of gemcitabine

incubation showed the highest difference among the two investigated

cell lines. Therefore, siRNA mediated knockdown of SHH was

performed and its influence on IC50 values of

gemcitabine was assessed using the xCELLigence system (Fig. 5 A, B, D and E). A knockdown ratio

for siSHH below 33% was achieved in both cases (Fig. 5, C and F). IC50 of

control siRNA transfected Capan-1 cells was 30.1 nM (Fig. 5A) and siSHH transfection decreased

IC50 to 27.6 nM (Fig.

5B). In control siRNA transfected Panc-1 cells, IC50

was 106.8 nM (Fig. 5D).

Interestingly, siSHH transfection revealed that proliferation in

Panc-1 cells is dependent on SHH as the transfected cells did not

show an increase in cell index (Fig.

5E). After 72–96 h, when the transient knockdown effect

attenuated, the cells reverted to an increased proliferation rate,

indicating a reversible inhibition of proliferation through

transient SHH knockdown. Determining the IC50 in these

cells was therefore not possible.

Expression of stem cell associated genes

and EMT regulators in primary pancreatic cancer cell lines

To confirm our results in a further model which

resembles patient tumors more closely, we performed the same

treatment with 10 μM gemcitabine in five recently established

primary pancreatic cancer cell lines PaCaDD-135, -159, -161, -165

and -188 and determined gene expression by qPCR (Table IB) after 3 and 6 days. Genes

upregulated more than 2-fold compared to untreated cells were

observed in the stem cell marker group (CD24, CD44, CD144 or EpCAM)

in all 5 cell lines, in the stem cell associated gene group (PDX1,

SHH, CBX7 or OCT4) in 4 of the 5 cell lines and in the EMT

regulator group (SNAI1/Snail, SNAI2/Slug, TWIST) in all cell lines.

While the pattern of upregulated individual genes varies among the

cell lines, the only gene being upregulated in all cell lines under

gemcitabine incubation was SNAI1/Snail, indicating a central role

of EMT induction as a response to chemotherapy also in primary

pancreatic cancer cell lines.

Discussion

In our study, we investigated the molecular

alterations after 6 days of gemcitabine treatment in 2 distinct

cell lines: the well-differentiated Capan-1 (which was G1 in the

original patient and shows G1 differentiation in nude or SCID mice

xenografts) and the poorly differentiated Panc-1 cells (G3)

(31,32). We could show that cells surviving 6

days of continuous gemcitabine exposure express higher levels of

almost all investigated stem cell markers, especially of PDX1, SHH,

CD44, CD133 and Slug in Panc-1 cells and PDX1, OCT4, CD24, CD133,

EpCAM and Snail in Capan-1 cells, respectively. The high expression

of Slug in Panc-1 cells was accompanied by an increased migration

in the scratch assay and by EMT-typical changes in the expression

pattern of β-catenin and E-cadherin.

Efforts have been made to explain drug resistance

based on the intrinsic detoxifying mechanisms of cancer stem cells.

Some of the genes investigated here have been linked with

chemoresistance in various models. One study investigating

pancreatic cancer cell chemoresistance found that the repopulation

of tumor cells following high-dose gemcitabine treatment was driven

by CD44+ cells (33).

Resistant pancreatic cancer cells cultured in the presence of

gemcitabine with synchronous radiation therapy expressed increased

levels of CD24, CD133, OCT4 and ABCG2 and showed phenotypic and

molecular changes consistent with EMT (34). Consequently, their ability to

migrate, form spheres and initiate tumors in nude mice was

increased. In our study, we also show an increase in stem cell

marker expression after 6 days of gemcitabine incubation. Most

notably, even after only one day of treatment, PDX1, OCT4 and CD44

were already induced more than two-fold, indicating an induction in

gene expression rather than selection of resistant cells. During

organ development, PDX1 is expressed in epithelial cells in the

foregut that give rise to the pancreatic buds and to the whole

pancreas. Its expression is reactivated during the formation of

pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and correlates with

PanIN grade, is maintained in pancreatic cancer and affects patient

survival (35). Similarly, in a

study investigating OCT4 expression in pancreatic cancer samples,

OCT4 expression was commonly found in metaplastic ducts (strong

expression in 79.2% of cases), followed by pancreatic cancer cells

(positive in 19.4% of cases) and lowest in non-tumorous pancreatic

tissue (positive in 16.7% of cases) (36). These data indicate that stem cell

associated genes are re-activated during tumor initiation. Our data

indicate that OCT4 is induced early in tumor cell response to

chemotherapeutic stimuli.

An increasing number of studies show that there is a

link between cancer stem cells and EMT. During development, SHH

signals to the epithelial ventromedial somite wall and induces the

connective tissue mesenchyme of the sclerotome, which is a

physiological example of EMT (37), and is essential for forming

three-dimensional structures from epithelial precursors. In our

experiments, we see a strong increase of SHH accompanied by a

strong increase of Slug in treated Panc-1 cells, and a weaker

increase of SHH and Slug in Capan-1 cells. The downstream effector

of the hedgehog pathway, Gli1, has been shown to induce the

accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus through Snail and

E-cadherin (38). Loss of

E-cadherin during EMT relocates β-catenin away from the cell

membrane allowing individual cells to separate from cell clusters.

We show that in response to gemcitabine, both Snail and Slug as

well as SHH are overexpressed. Concordantly, we show the nuclear

trans-location of β-catenin and the loss of membraneous expression

of E-cadherin, as expected in EMT. Further, EMT can also be

regulated by Notch signaling, which is also increased in our

experiments in Panc-1 cells. While Snail is equally induced in

Capan-1 and Panc-1 cells, Slug is differentially expressed between

the two cell lines. This behavior could be explained by their

respective baseline expression levels: Slug is expressed at low

levels in Panc-1 cells and could thus be induced stronger compared

Snail, which is expressed at higher baseline levels. Similar

baseline expression levels of Snail and Slug have been shown by

others both on transcript and protein levels (39). In cells surviving gemcitabine

incubation, both EMT regulators are overexpressed thus indicating a

protective role of this mechanism against the chemotherapeutic

drug.

These data link the role of cells expressing stem

cell markers to those undergoing EMT. Data obtained from

experiments in benign mammary glands and mammary carcinomas show a

direct link between EMT and the gain of epithelial stem-cell

properties (25): in immortalized

non-malignant human mammary epithelial cells, EMT was induced by

treatment with TGF-β or by ectopic expression of Snail or TWIST. As

expected, these cells acquired a mesenchymal phenotype and a mRNA

expression pattern consistent with EMT, and, most interestingly,

exhibited a CD44high/CD24low surface marker

configuration - the antigenic phenotype ascribed to neoplastic

mammary stem cells. This phenotype was also functionally associated

with properties of stem cells as shown in their ability to form

more mammospheres than untransformed cells.

Identifying a general marker or a set of markers to

pinpoint stem cells in solid tumors has proven difficult, as

exemplified by CD133, the expression of which has been used in the

identification of cancer stem cells in various tumors, such as

brain, lung, colon, kidney, prostate, liver, colon and skin cancer.

However, its importance as a general ‘stemness’ marker has been

questioned by recent studies on its expression in various normal

glandular tissues in general (40,41)

and in normal adult pancreata and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas

(42). In the healthy pancreas,

CD133 expression is seen to be initiated in cells at the center of

the acini soon after lumen formation, and continues along the

ductal system into the following ducts up to the larger ducts,

thereby fading in expression intensity. CD133 and CK19 (a ductal

marker) are generally co-localized in the fully differentiated

ductal epithelium. Although apical staining is seen in the majority

of epithelial cells, cells located near the luminal surface within

the acini showed strong cytoplasmic CD133 staining paired with CK19

negativity, indicating an altered differentiation. In tumor

specimens, CD133 positive cells are identified in 80% of the cases,

with mostly apical/endoluminal expression, and cytoplasmic staining

is observed in about 1% of the malignant cells. In summary, in both

normal pancreata and adenocarcinomas of the pancreas, there seem to

exist two distinct populations of CD133 expressing cells: a major

population with apical/endoluminal CD133 expression, which

represents a particular stage in cell differentiation related to

the formation of lumina and ducts, and a minor, rare, population

which expresses CD133 in the cytoplasm. In our study we show that

CD133 is enriched both on mRNA and protein levels in treated cells

and particularly the treated Panc-1 cells differ in their

subcellular localization of CD133. Similar findings were reported

from glioblastoma patients, which showed that CD133 positive cells

were enriched in recurrent glioblastoma and showed increased

resistance against a multitude of chemotherapeutic agents (43). While each of the putative stem cell

markers CD24, CD44 or CD133 was increased in our two investigated

established cell lines and partly in the primary cell lines as

well, also other stem cell associated genes were upregulated. Along

with the induction of these genes, downstream effectors of

chemoresistance, such as ATP-binding cassette transporters could

confer the resistant phenotype (33). While our experimental design does

not allow to fully differentiate between gene induction and

selection of putative cancer stem cells, based on our data we

deduct that stem cell associated genes are an important factor in

cellular response to chemotherapeutic agents such as gemcitabine.

However, the role of each gene in chemoresistance and its

downstream effectors has to be investigated carefully to elucidate

a possible key gene, which might act as a therapeutic target.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Astrid Taut and

Isabel Zeitträger for their help in conducting the experiments.

This study was in part funded by a grant of the ‘Stiftung P. E.

Kempkes’ at the Philipps University of Marburg, Germany.

References

|

1.

|

Ellison LF and Wilkins K: An update on

cancer survival. Health Rep. 21:55–60. 2010.

|

|

2.

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J and Ward E: Cancer

statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 60:277–300. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Burris HA III, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et

al: Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine

as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a

randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 15:2403–2413. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al:

Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in

patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the

National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin

Oncol. 25:1960–1966. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5.

|

Conroy T, Paillot B, François E, et al:

Irinotecan plus oxaliplatin and leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil

in advanced pancreatic cancer - a Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of the

Federation Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer study. J

Clin Oncol. 23:1228–1236. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6.

|

Ducreux M, Boige V and Malka D: Treatment

of advanced pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 34:S25–S30. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al: Global

cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8.

|

Wang Z, Li Y, Ahmad A, et al: Pancreatic

cancer: understanding and overcoming chemoresistance. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 8:27–33. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Klonisch T, Wiechec E, Hombach-Klonisch S,

et al: Cancer stem cell markers in common cancers - therapeutic

implications. Trends Mol Med. 14:450–460. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Liu QH, Zhang J, Zhao CY, et al: Surviving

cells after treatment with gemcitabine or 5-fluorouracil for the

study of de novo resistance of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett.

314:119–125. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Bonner-Weir S and Sharma A: Pancreatic

stem cells. J Pathol. 197:519–526. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12.

|

O’Brien CA, Kreso A and Jamieson CH:

Cancer stem cells and self-renewal. Clin Cancer Res. 16:3113–3120.

2010.

|

|

13.

|

Zhang YQ, Kritzik M and Sarvetnick N:

Identification and expansion of pancreatic stem/progenitor cells. J

Cell Mol Med. 9:331–344. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Lee CJ, Dosch J and Simeone DM: Pancreatic

cancer stem cells. J Clin Oncol. 26:2806–2812. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Quante M and Wang TC: Stem cells in

gastroenterology and hepatology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

6:724–737. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Wang JC and Dick JE: Cancer stem cells:

lessons from leukemia. Trends Cell Biol. 15:494–501. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Zou GM: Cancer initiating cells or cancer

stem cells in the gastrointestinal tract and liver. J Cell Physiol.

217:598–604. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H, et al:

Characterization of a side population of cancer cells from human

gastrointestinal system. Stem Cells. 24:506–513. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Haraguchi N, Inoue H, Tanaka F, et al:

Cancer stem cells in human gastrointestinal cancers. Hum Cell.

19:24–29. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20.

|

Hermann PC, Bhaskar S, Cioffi M and

Heeschen C: Cancer stem cells in solid tumors. Semin Cancer Biol.

20:77–84. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Zhou J, Wang CY, Liu T, et al: Persistence

of side population cells with high drug efflux capacity in

pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 14:925–930. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, et al: Acquisition

of epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype of

gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells is linked with

activation of the notch signaling pathway. Cancer Res.

69:2400–2407. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23.

|

Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Fournier KF,

et al: Epithelial to mesenchymal transition contributes to drug

resistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 69:5820–5828. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Kim MP and Gallick GE: Gemcitabine

resistance in pancreatic cancer: picking the key players. Clin

Cancer Res. 14:1284–1285. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, et al: The

epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties

of stem cells. Cell. 133:704–715. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Rückert F, Werner K, Aust D, et al:

Immunohistological analysis of six new primary pancreatic

adenocarcinoma cell lines. Global J Biochem. 3:112012.

|

|

27.

|

Rückert F, Aust D, Böhme I, et al: Five

primary human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines established by

the outgrowth method. J Surg Res. 172:29–39. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Pfaffl MW, Horgan GW and Dempfle L:

Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison

and statistical analysis of relative expression results in

real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e362002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Pfaffl MW: A new mathematical model for

relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res.

29:e452001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Ke N, Wang X, Xu X and Abassi YA: The

xCELLigence system for real-time and label-free monitoring of cell

viability. Methods Mol Biol. 740:33–43. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Sipos B, Moser S, Kalthoff H, et al: A

comprehensive characterization of pancreatic ductal carcinoma cell

lines: towards the establishment of an in vitro research platform.

Virchows Arch. 442:444–52. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Neureiter D, Zopf S, Dimmler A, et al:

Different capabilities of morphological pattern formation and its

association with the expression of differentiation markers in a

xenograft model of human pancreatic cancer cell lines.

Pancreatology. 5:387–397. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33.

|

Hong SP, Wen J, Bang S, Park S and Song

SY: CD44-positive cells are responsible for gemcitabine resistance

in pancreatic cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 125:2323–2331. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Du Z, Qin R, Wei C, et al: Pancreatic

cancer cells resistant to chemoradiotherapy rich in

‘stem-cell-like’ tumor cells. Dig Dis Sci. 56:741–750.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35.

|

Quint K, Stintzing S, Alinger B, et al:

The expression pattern of PDX-1, SHH, Patched and Gli-1 is

associated with pathological and clinical features in human

pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 9:116–26. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36.

|

Wen J, Park JY, Park KH, et al: Oct4 and

Nanog expression is associated with early stages of pancreatic

carcinogenesis. Pancreas. 39:622–626. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Fan CM and Tessier-Lavigne M: Patterning

of mammalian somites by surface ectoderm and notochord: evidence

for sclerotome induction by a hedgehog homolog. Cell. 79:1175–1186.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

Li X, Deng W, Lobo-Ruppert S and Ruppert

J: Gli1 acts through Snail and E-cadherin to promote nuclear

signaling by β-catenin. Oncogene. 26:4489–4498. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Hotz B, Arndt M, Dullat S, et al:

Epithelial to mesenchymal transition: expression of the regulators

Snail, Slug, and Twist in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

13:4769–4776. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Missol-Kolka E, Karbanová J, Janich P, et

al: Prominin-1 (CD133) is not restricted to stem cells located in

the basal compartment of murine and human prostate. Prostate.

71:254–267. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Karbanová J, Missol-Kolka E, Fonseca AV,

et al: The stem cell marker CD133 (Prominin-1) is expressed in

various human glandular epithelia. J Histochem Cytochem.

56:977–993. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Immervoll H, Hoem D, Sakariassen PØ,

Steffensen OJ and Molven A: Expression of the ‘stem cell marker’

CD133 in pancreas and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas. BMC

Cancer. 8:482008.

|

|

43.

|

Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, et al: Analysis of

gene expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer

stem cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 5:672006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|