Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is the most common and deadly

extra-cranial solid tumor of childhood. NBs, together with the more

differentiated, less aggressive ganglioneuromas and

ganglioneuroblastomas, form the neuroblastic tumors. They are all

derived from migratory, primitive precursor cells of the developing

sympathetic nervous system. NB tumors are graded according to INSS

stage, where stages 1 and 2 represent low-risk tumors and stages

3–4 high-risk tumors (1,2). Children that are diagnosed with NB

when they are over 1 year of age generally suffer from the advanced

stages of the disease. These NB tumors, especially stage 4, can

rapidly spread to regional lymph nodes and then to distal bone and

bone marrow, resulting in very poor patient prognosis. Infants

diagnosed with NB can present a unique pattern of metastatic spread

(stage 4S, S = Special) to the liver and skin, but only rarely to

bone or bone marrow. Remarkably, these metastasized tumors usually

undergo spontaneous regression and patients have excellent

prognosis (1,2). Important prognostic features of NB

tumors are therefore INSS stage and patient age at diagnosis. In

addition, recurrent genomic aberrations like MYCN gene

amplification can be used for patient stratification (1,2).

Unfortunately, these combined NB features are still too limited to

ensure early proper treatment stratification and new prognostic

markers are needed. In addition, NB treatment, especially of

metastasized tumors is still not sufficiently efficient and more

insight is needed into the molecular pathways involved in NB

metastasis.

Prenylated Rab acceptor 1 domain family, member 2

(PRAF2, initially described as JM4) is a 19-kDa protein with four

transmembrane-spanning domains. PRAF2 belongs to the PRAF family of

vesicle transport-associated proteins. Members of the PRAF family

are structurally related and contain a large prenylated Rab

acceptor 1 (PRA1) domain. These PRAF proteins are localized in the

ER, Golgi and vesicular structures of the cell (3,4).

PRAF2 was first discovered as an interacting protein of human

chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) (3)

and of human glycerophosphoinositol phosphodiesterase (GDE1/MIR16)

(5). Human PRAF2 is highly

expressed in numerous tissues: small intestine, lung, spleen,

pancreas and most significantly in the brain. Furthermore,

overexpression of PRAF2 is observed in tumor tissue samples of

breast, colon, lung and ovary, compared to matched normal tissue

samples (4,6,7).

The other two members of PRAF protein family (PRAF1

and PRAF3) have already been extensively studied and their

biological function has been characterized. In fact, many of these

studies associated PRAF1 and PRAF3 with several well-known cancer

signaling pathways. For instance, PRAF1 (also known as Rabac1,

PRA1, prenylin and Yip3), a Golgi complex, post-Golgi vesicle and

endosomal transmembrane protein, was initially identified to

interact with small GTPase proteins that regulate intracellular

vesicle trafficking (8–10). In addition, PRAF1 has a crucial

role in colorectal tumorigenesis by regulating the nuclear

transport of β-catenin in TCF/β-catenin signaling (11). PRAF1 functions in Epstein-Barr

virus (EBV)-induced transformation: it binds and modulates the

anti-apoptotic activity of BHRF1, an EBV-encoded early protein and

enhances nuclear import of the oncogenic EBV-encoded latent

membrane protein 1 (LMP1) (12,13).

PRAF3 (also known as JWA, GTRAP3–18 and Arl6-IP5) is

an integral ER membrane protein that is upregulated by retinoic

acid (RA) and then activates the excitation amino acid carrier 1

(EAAC1), a primary neuronal glutamate transporter (14,15).

PRAF3 is also defined as a potential inhibitor of cancer cell

migration by regulation of the MAPK signaling pathway and F-actin

cytoskeleton (16). PRAF3 was

found to inhibit melanoma metastasis by suppressing integrin αvβ3

signaling, a key factor in tumor metastasis. Downregulation of

PRAF3 in melanoma cells significantly increased integrin αvβ3

expression (both at mRNA and protein level) and accelerated cell

adhesion, migration and invasion in vitro and enhanced

melanoma lung metastasis in vivo.

Unlike PRAF1 and PRAF3, PRAF2 has not yet been

widely studied and its functional role therefore remains largely

unknown. Previously, our lab found PRAF2 as a candidate prognostic

marker of neuroblastic tumors. We observed high level of PRAF2 mRNA

in most neuroblastic tumor samples. We also found that PRAF2

protein is strongly expressed in all 24 NB cell lines tested,

including SK-N-SH (17). Despite

these discoveries, the molecular role of PRAF2 in NB tumorigenesis,

or in other tumors in which it is highly expressed, has remained

unexplored. Therefore, in this study, we generated NB cell lines

that stably downregulate endogenous PRAF2 expression by RNA

interference (RNAi). We used these PRAF2 knockdown NB cell lines to

investigate the function of PRAF2 in NB tumorigenesis. Metastasis

is the main cause of death in NB patients, but its underlying

mechanisms remain elusive. Considering the role of its homolog

PRAF3 in melanoma invasion and metastasis, we were especially

interested to find out if PRAF2 is involved in NB metastasis and

therefore focused on cell migration and matrix-attachment.

Materials and methods

Cell line culture

The human NB cell line SK-N-SH was purchased from

the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were

maintained in RPMI-1640 (Media tech Inc., Manassas, VA) containing

10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corp.,

Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5%

CO2. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer in the

presence of trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Construction of stable PRAF2 knockdown NB

cell lines

HuSH 29-mer short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expression

constructs against PRAF2 (shPRAF2) and GFP (scrambled; as a

negative control) were purchased from Origene Technologies

(Rockville, MD). SK-N-SH cells were seeded in 6-well culture plates

(Greiner Bio-One Inc., Monroe, NC) at a concentration of

5.0×105 cells per well and transfected with 4 μg

shPRAF2 or scrambled plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Transfected cells were incubated for 24 h at 37°C as described

above and subsequently selected using 1.0 μg/ml puromycin

(Sigma-Aldrich). After selection for 2 weeks, cells retaining the

shPRAF2 (SK-shPRAF2) or scrambled expression vector (SK-Sc) were

maintained at 100 ng/ml puromycin.

Western blot analysis

For total protein isolation, medium was removed by

aspiration, adherent cells were washed twice in ice-cold DPBS

(Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline, Mediatech) and cell lysates

prepared by scraping on ice into radioimmunoprecipitation assay

(RIPA) buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.1% (w/v) sodium lauryl

sulfate, 0.5% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 135 mM NaCl, 1% (v/v)

Triton X-100, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM EDTA], supplemented with

Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche Diagnostic Corp.,

Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitors (20 mM sodium fluoride

and 0.27 mM sodium vanadate). Lysate samples were resuspended by

rotation at 50 rpm and 4°C for at least 30 min and clarified by

centrifugation for 15 min at 14,000 rpm and 4°C. The supernatant

was stored at − 20°C until further use. Total protein concentration

was determined by Bradford dye reagent protein assay (Bio-Rad

Laboratories Inc., Richmond, CA). Laemmli buffer (Bio-Rad)

containing 10% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol (VWR International,

Brisbane, CA) solution was added to the lysates and boiled for 5

min. Ten micrograms total protein was resolved by 12% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and

electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane

(Immobilon-P, VWR International). Membranes were incubates with

rabbit polyclonal PRAF2, peptide-blocked rabbit polyclonal PRAF2

(PRAF2-P) (QED Bioscience, San Diego, CA), or rabbit monoclonal

α-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) primary

antibodies. The membranes were then washed and incubated with

enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) rabbit or mouse IgG, horseradish

peroxidase (HRP)-linked secondary antibody (GE Healthcare

Biosciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Subsequently, membranes were again

washed and protein-antibody complexes were detected using ECL plus

western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare Biosciences) and

Blue Lite Autorad Film (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, UT). Bands were

quantified using the Bio-Rad Multi Imager and its Quantity One

Quantification software.

Cell viability assay

Cells (1.0×104 cells in 0.1 ml) were

seeded in 96-well microtiter plates (Greiner Bio-One Inc.) and

incubated for 24, 48 or 72 h. For each time point, 20 μl of

CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega Bioscience Inc.,

San Luis Obispo, CA) was added to wells and incubated at 37°C for 3

h. The conversion of MTS tetrazolium to soluble formazan in cell

cultures was measured at 490 nm using an HTS 7000 Plus Microplate

Reader (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). Optical density (OD) readings,

proportional to the number of viable cells, were calculated and

evaluated using Microsoft Excel.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation was determined with the EMD BrdU

Cell Proliferation Assay kit (EMD Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA),

following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cells were seeded

and grown as above. For each time point, 20 μl of BrdU label

was added to cell cultures and allowed to incorporate into DNA for

2 h at 37°C. Cells were fixed and denatured, upon addition of 200

μl fixative/denaturing solution, for 30 min at room

temperature. Anti-BrdU antibody (1:100) was added and incubated for

1 h at room temperature to bind incorporated BrdU label. Unbound

BrdU antibodies were removed by washing three times with wash

buffer. Peroxidase goat anti-mouse IgG HRP conjugate (200

μl) was added and incubated for 30 min at room temperature.

Cells were washed twice with wash buffer and once with deionized

water. Cells were incubated in 100 μl substrate solution for

15 min in the dark at room temperature, after which 100 μl

stop solution was added to the cells. Absorbance was measured

immediately at 450 nm using the HTS 7000 Plus Microplate Reader. OD

readings, representing cell proliferation, were calculated and

evaluated using Microsoft Excel.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells (1.0×106 cells in 1 ml) were seeded

in 60-mm culture plates (Greiner Bio-One Inc.) and incubated for 24

h. Cells were trypsinized, washed twice in DPBS and counted using a

hemocytometer. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm

and resuspended to 2.0×106 cells/ml DPBS. One million

cells per 5 ml polystyrene tube (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA)

were fixed by slow addition of 1.5 ml 70% ice-cold ethanol (Fisher

Scientific) under gentle vortexing. Ethanol-fixed cells were

incubated in an ice bath for 1 h, pelleted again and washed twice

in DPBS. Cells were then resuspended and stained with 0.5 ml

PI/RNase staining buffer (Becton-Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose,

CA) for 15 min at room temp in the dark. Finally, stained cells

were resuspended in 1 ml DPBS. A minimum of 10,000 cells was

analyzed using the FACScan flow cytometry instrument and its

CellQuest software (Becton-Dickinson).

Wound-healing assay

Cell migration in vitro was determined using

the wound-healing assay as described by Valster et

al(18). Briefly, cells were

cultured to confluency in a 6-well culture plate and wounds

scratched through the monolayer using a sterile 20 μl

pipette tip. Cells were carefully washed several times with DPBS to

remove floating cells and fresh medium was added back without

detaching cells. Cell images were taken at 0, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h

using a Leica DM-IL digital microscope (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo

Grove, IL). The rate of wound closure was calculated as the ratio

of the migrated cell surface area divided by the total surface

area.

Adhesion assay

Immulon-2 96-well microtiter plates (Fisher

Scientific) were pre-coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin (FN),

vitronectin (VN), or laminin (LM) (all from Sigma) or not coated

and incubated overnight at 4°C. Substrates were removed by

aspiration and blocking solution (2% BSA heat-inactivated in DPBS)

was added to coated and uncoated wells and incubated for 2 h at

room temperature. Afterwards, wells were washed with serum-free

RPMI. Cells (50,000 cells in 0.1 ml) were seeded and incubated for

90 min at 37°C and then washed with DPBS until cells in the

BSA-only coated control wells were completely removed. Attached

cells were fixed with 50% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in DPBS for 20 min

at room temperature, after which the solution was removed by

aspiration and the cells allowed to air-dry for 5 min. Cells were

then stained with 0.5% crystal violet in 20% methanol for 45 min

and washed three times with DPBS. The cells were air-dried and

solubilized in 10% acetic acid for 30 min. Absorbance was measured

at 560–590 nm using a Perkin-Elmer HTS 7000 Plus microplate reader.

OD readings, representing the number of adherent cells, were

calculated and evaluated using Microsoft Excel.

Affymetrix DNA micro-array hybridization

and analysis

The Affymetrix NB tumor dataset Versteeg-88 contains

the mRNA expression profiles of 88 NB tumors with documented

genetic and clinical features and has been described (19). Total RNA was extracted from frozen

NBs containing >95% tumor cells and Affymetrix HG-U133 Plus 2.0

micro-array analysis (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) performed

as described (20). The

Versteeg-88 set has been deposited for public access in a

MIAME-compliant format through the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)

database at the NCBI website (21)

under number GSE16476. Public domain data-sets Hiyama-51

(GSE16237), Jagannathan-100 (GSE19274), Łastowska-30 (GSE13136),

Maris-101 (GSE3960) were also from the NCBI GEO site, the

Oberthuer-251 set (E-TABM-38) was from EMBL-EBI ArrayExpress.

Annotations and clinical data for the tissue samples analyzed are

available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/ or http://www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress/ thru their GEO

or EMBL-EBI ID’s, respectively. CEL data for all data-sets were

downloaded and analyzed as previously described (20). Briefly, gene transcript levels were

determined from data image files using GeneChip operating software

(MAS5.0 and GCOS1.0, from Affymetrix). Samples were scaled by

setting the average intensity of the middle 96% of all probe-set

signals to a fixed value of 100 for every sample in the dataset,

allowing comparisons between micro-arrays. The TranscriptView

genomic analysis and visualization tool was used to check if

probe-sets had an anti-sense position in an exon of the gene

(http://bioinfo.amc.uva.nl/human-genetics/transcriptview/).

The Affymetrix probe-set selected for PRAF2, 203456_at meets these

criteria and showed significant expression in all 88 samples in the

Versteeg-88 set. Analyses were performed using R2; an Affymetrix

analysis and visualization platform developed in the Department of

Human Genetics at the Academic Medical Center, University of

Amsterdam. R2 can be accessed at: http://r2.amc.nl.

Statistical analyses

PRAF2 correlation with survival probability was

evaluated by Kaplan-Meier analysis using the Wilcoxon log-rank test

as described (22). PRAF2

expression and correlation with NB clinical and genetic features

were determined using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test;

correlation with other gene expressions was calculated with a 2log

Pearson test. The significance of a correlation is determined by t

= R/sqrt[(1−r^2)/(n−2)], where R is the correlation value and n is

the number of samples. Distribution measure is approximately as t

with n-2 degrees of freedom. The statistical significance of the

effects on NB cell viability, proliferation, cell cycle and

adhesion were determined using the statistical Student’s t-test.

For all tests, P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

PRAF2 expression correlates with NB

parameters indicative of poor outcome

We have previously shown that PRAF2 expression is

higher in neuroblastic tumors than in most other cancers. To

explore the potential role of PRAF2 in NB, the most aggressive

neuroblastic tumor, we investigated PRAF2 expression in a new

cohort of NB tumors. We analyzed a series of 88 NB tumors for which

extensive genetic and clinical features were available from patient

files (‘Versteeg-88’, Academic Medical Center at the University of

Amsterdam) using the genome-wide HG-U133 Plus 2.0 Affymetrix DNA

microarray. We found that PRAF2 was efficiently expressed in all 88

NB samples. Since MYCN amplification is the most dependable

prognostic marker and is associated with very poor prognosis, we

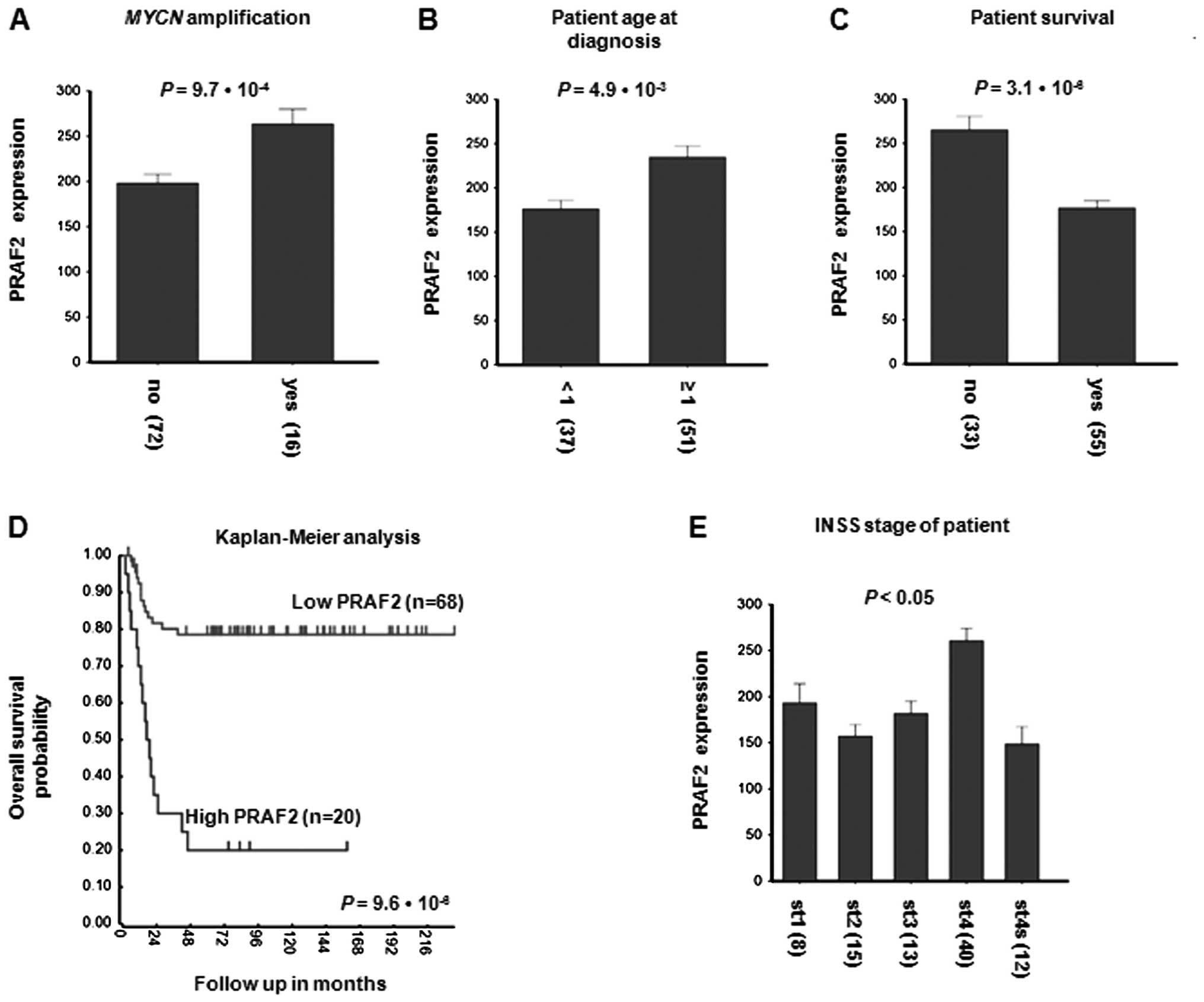

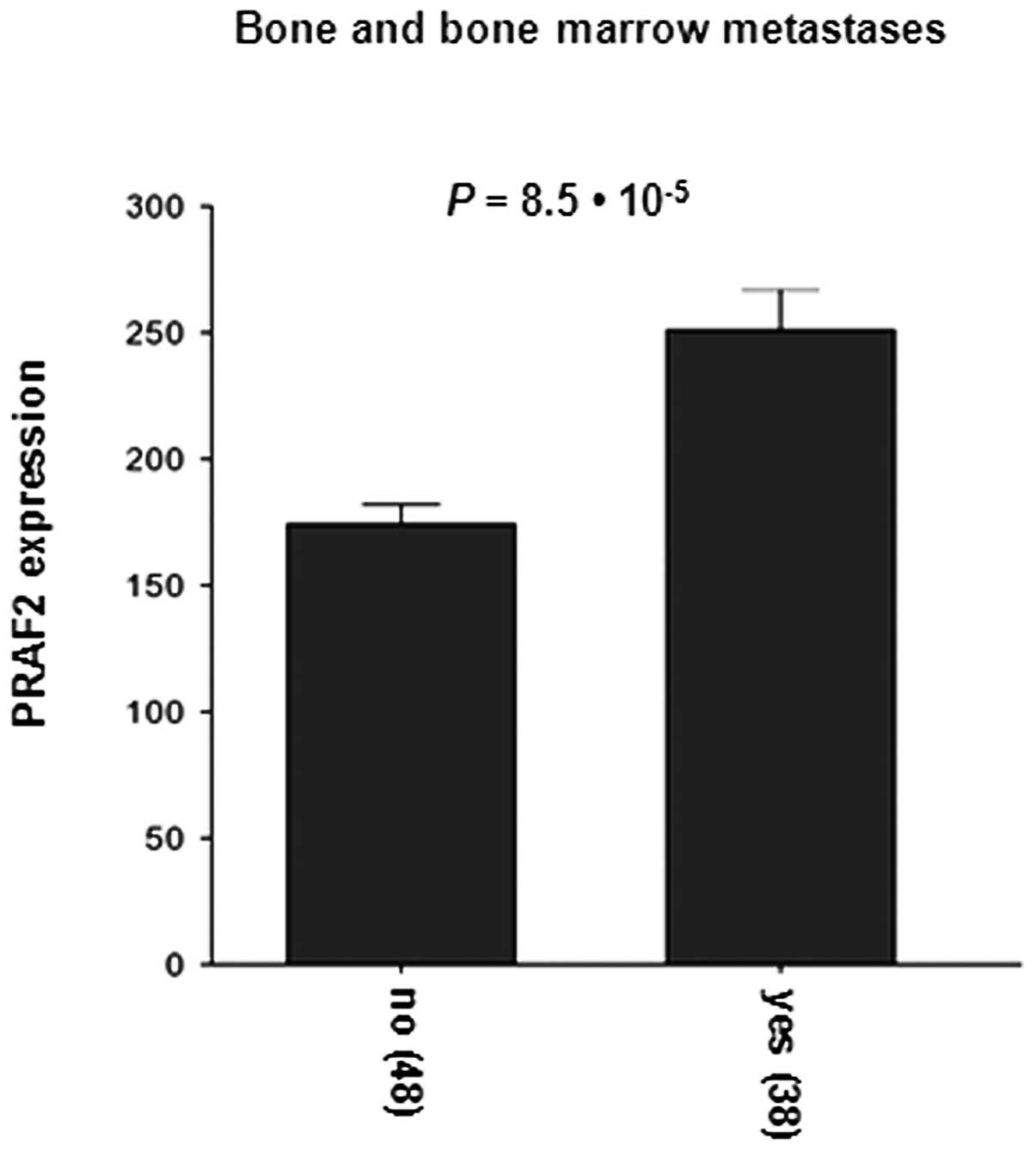

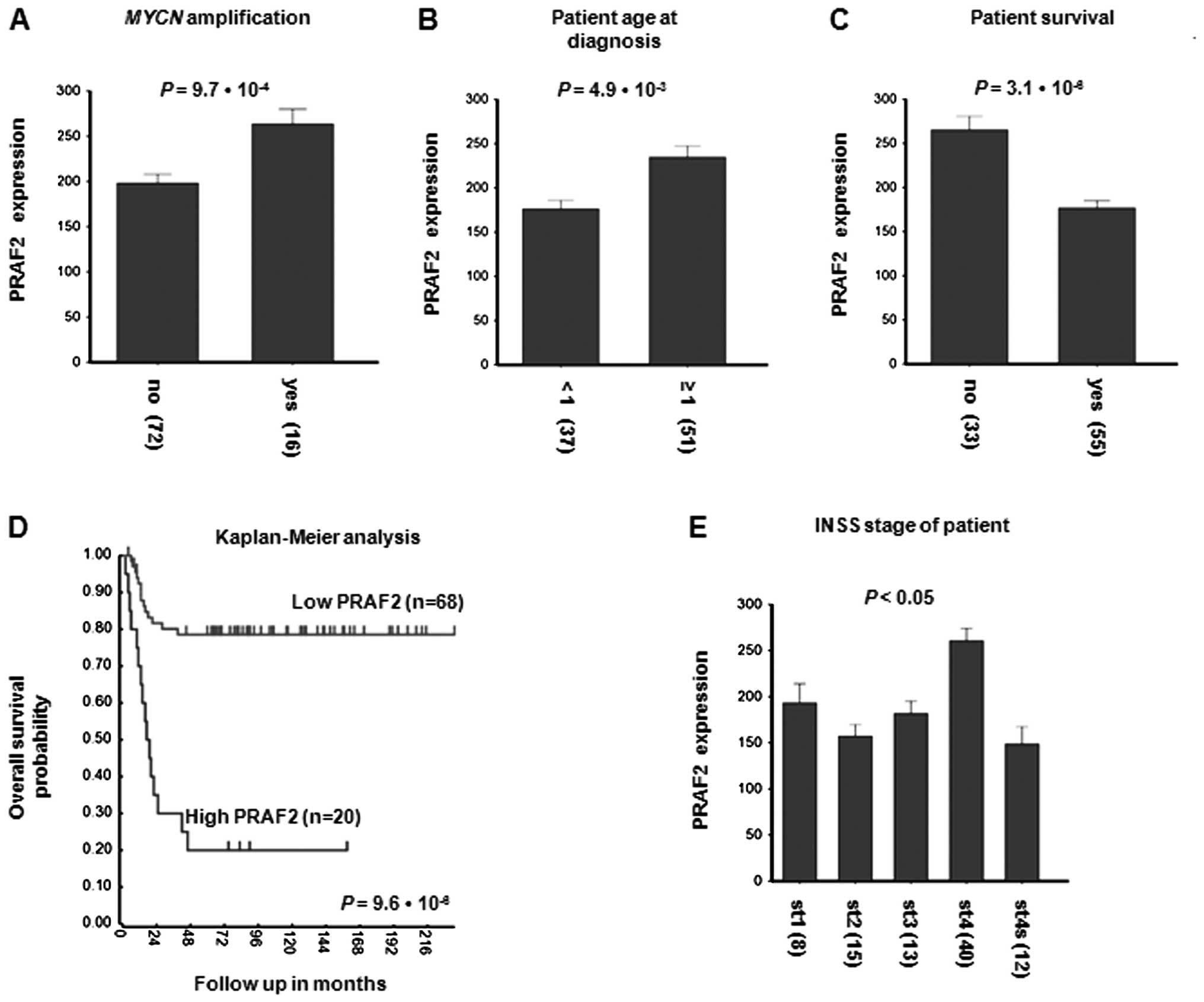

investigated a possible correlation PRAF2 expression. Fig. 1A shows that PRAF2 is significantly

higher in MYCN-amplified tumors than in tumors with a

diploid MYCN gene complement (P=9.7×10−4;

Fig. 1A). In addition, PRAF2

expression is higher in patients diagnosed when they are older than

1 year old than in younger patients (P=4.9×10−3;

Fig. 1B). Since high PRAF2

expression is correlated to two unfavorable clinical parameters of

NB, it was not surprising that PRAF2 expression in tumor samples

taken from NB patients that have since died is significantly higher

than that in NB from patients that are still alive at the time of

analysis (P=3.1×10−6; Fig.

1C). To assess the predictive value of PRAF2 expression, we

performed Kaplan-Meier analysis. The most significant P-value was

found when the Versteeg-88 set was divided into a group of 20 with

high and of 68 with low expression of PRAF2 mRNA, but also for most

other groupings within the set, high PRAF2 expression was

significantly indicative for poor outcome (Fig. 1D). Survival of patients with low

PRAF2 expression (n=68) was ∼80% for up to 216 months, while that

for patients with high PRAF2 expression (n=20) dropped to 20%

within 48 months (P=9.6×10−6; Fig. 1D). Not surprisingly therefore, when

PRAF2 expression was investigated with respect to INSS stage, we

found that PRAF2 expression was highest in the most aggressive,

stage 4 tumors, that often and rapidly metastasize to lymph nodes,

bone and bone marrow and are the major cause of

neuroblastoma-related death. Of note, PRAF2 expression was

significantly higher in stage 4 tumors than in any other stage

(P<0.05; Fig. 1E), including

stage 4S tumors. Since these tumors can metastasize to skin and

liver but have an extremely good prognosis, this would suggest

PRAF2 has a role in clinically important, but not 4S metastasis

processes. Together, the results from the Versteeg-88 set strongly

suggest a role for PRAF2 in tumor cell survival and aggressive

tumor growth and metastasis. To investigate the robustness of these

observations in the NB series presented in this report, we

investigated the correlations found between PRAF2 expression and NB

clinical parameters in five additional NB series in the public

domain (Table I). We observed

similar patterns for PRAF2 mRNA expression in these independent

series, suggesting that the results obtained with the Versteeg-88

set are representative. However, as noted before, the molecular

role of PRAF2 in these processes is still completely unknown.

| Figure 1Correlation of PRAF2 expression with

clinical features of NB. PRAF2 mRNA expression was examined by

Affymetrix micro-array in the Versteeg-88 series of 88 NB tumors

with full clinical description and compared with important clinical

parameters. PRAF2 mRNA expression correlates with (A) tumor

MYCN amplification, (B) age at diagnosis, (C) patient

survival during follow-up, (D) patient survival probability and (E)

INSS stage of the disease. (A) NB patients with tumor MYCN

amplification (16 samples) expressed significantly higher PRAF2

levels than patients without tumor MYCN amplification (72

samples; P=9.7×10−4). (B) NB patients that were

diagnosed above the age of 1 year (higher risk; 51 samples)

expressed significantly higher PRAF2 tumor levels than patients

that were diagnosed below this age (lower risk; 34 samples;

P=4.9×10−3). (C) NB patients that were still alive at

the time of analysis (55 samples) expressed significantly higher

PRAF2 tumor levels than patients who had died before that time (33

samples; P=3.1×10−6). (D) PRAF2 gene expression

correlates with NB patient survival prognosis. Shown is a

Kaplan-Meier graph representing the survival prognosis of 88 NB

patients based on high or low expression levels of PRAF2. The

survival probability of NB patients (follow-up >216 months) with

high PRAF2 expression is significantly lower than of patients with

low PRAF2 expression. For the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the P-values

were calculated for all 72 groups tested (minimum group size = 8).

For PRAF2, the 20 ‘high’ versus the 68 ‘low’ group represents the

highest P-value (P=9.6×10−6), but the P-value was

<0.05 for all groups from 28 low/60 high to 77 low/11 high. Also

when the 88 tumors were divided using the median or average PRAF2

expression, P-value was <0.05, showing that PRAF2 expression has

a robust correlation with survival. Statistical analysis was

performed with the Wilcoxon log-rank test. (E) Children with NB

tumor stages 1, 2, 3 or 4S (8, 15, 13 or 12 samples, respectively)

expressed significantly lower-level PRAF2 tumor levels than

children with tumor stage 4 (40 samples; stage 4 comparison to any

other stage has P<0.05). Statistical analysis of (A–C) and (E)

was performed using the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests, but

for reasons of representation, the bar plots show actual expression

values. Numeric values in parentheses indicate the number of

evaluated NB patient tumor samples. For expression value

calculations in all panels, see Materials and methods. |

| Table IPRAF2 correlations with clinical

parameters in additional NB tumor sets in the public domain. |

Table I

PRAF2 correlations with clinical

parameters in additional NB tumor sets in the public domain.

| Set | Kaplan-Meier | Survival | INSS | MYCNA | Platform |

|---|

| Hiyama-51 | ND | Lower in alive | ST4 highest | NS | Affymetrix HG-U133

Plus 2.0 |

|

Jagannathan-100 | ND | Lower in

low-risk | ST3 higher than

ST4 | Higher in MNA | Illumina HWG

6V2 |

| Łastowska-30 | ND | ND | ST4 highesta | NS | Affymetrix HG-U133

Plus 2.0 |

| Maris-101 | ND | ND | ST4 highest | Higher in MNA | Affymetrix HG-U95

Av2 |

| Oberthuer-251 | Poor prognosis | Lower in alive | ST4 highest | Higher in MNA | Amexp255 |

| Versteeg-88 | Poor prognosis | Lower in alive | ST4 highest | Higher in MNA | Affymetrix HG-U133

Plus 2.0 |

Generation of stable PRAF2 knockdown NB

cells using shRNA

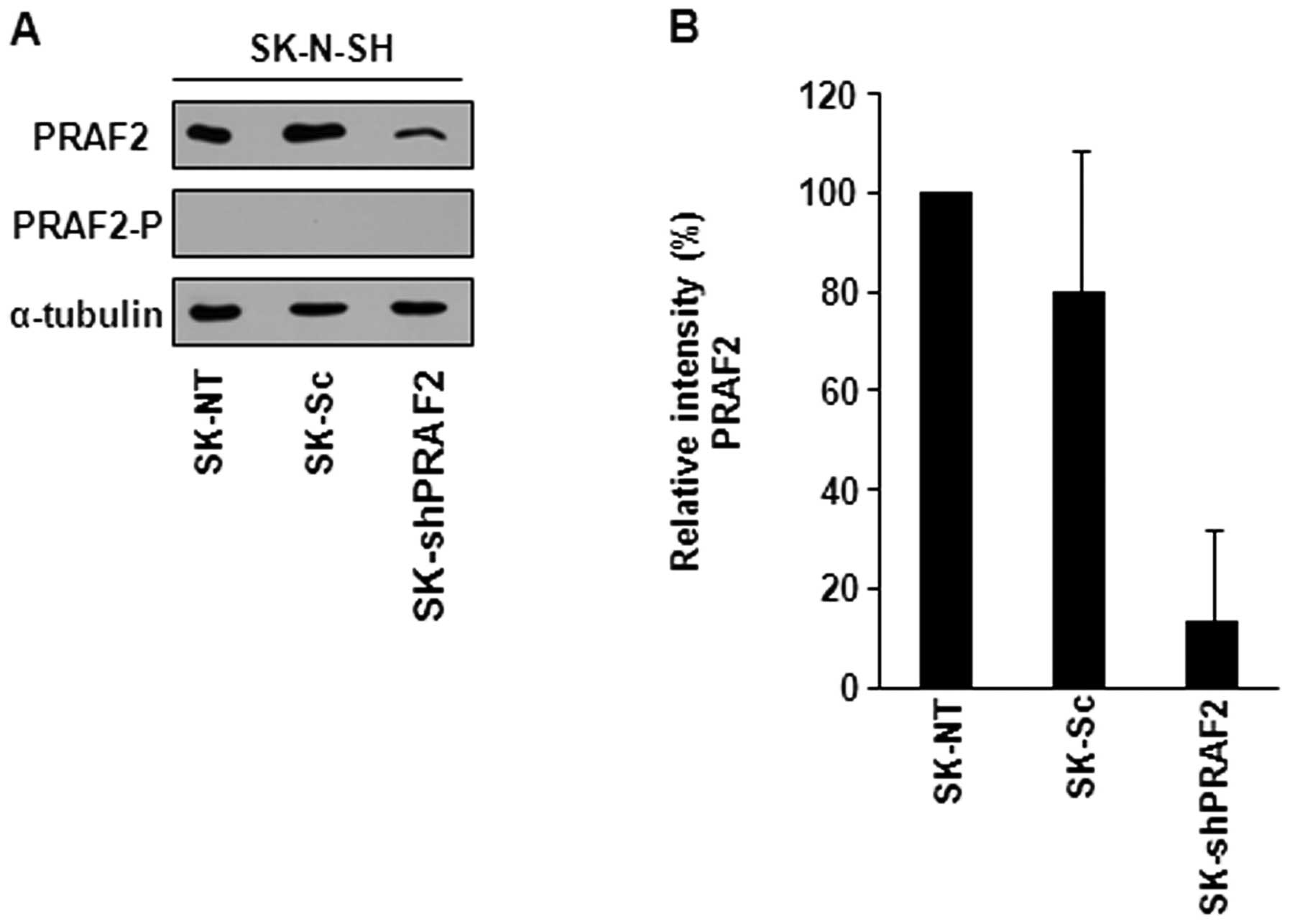

To confirm a role for PRAF2 in NB progression and to

gain insight into the molecular pathways downstream of PRAF2

function, we generated PRAF2 knockdown NB cell lines using shRNA.

We stably transfected PRAF2 shRNA (shPRAF2) or scrambled control

shRNA (Sc) expression vectors into SK-N-SH NB cells, grew

shRNA-expressing clones and analyzed the PRAF2 protein content of

these clones by western blotting. We used the peptide-blocked PRAF2

antibody (PRAF2-P) to confirm that the PRAF2 bands we detected are

specific. PRAF2-P antibody prevents PRAF2 from binding. As

expected, PRAF2-P antibody did not recognize PRAF2 (Fig. 2A). PRAF2 shRNA-transduced SK-N-SH

cells (SK-shPRAF2) showed ∼80% decrease in PRAF2 protein expression

in comparison with control cells.

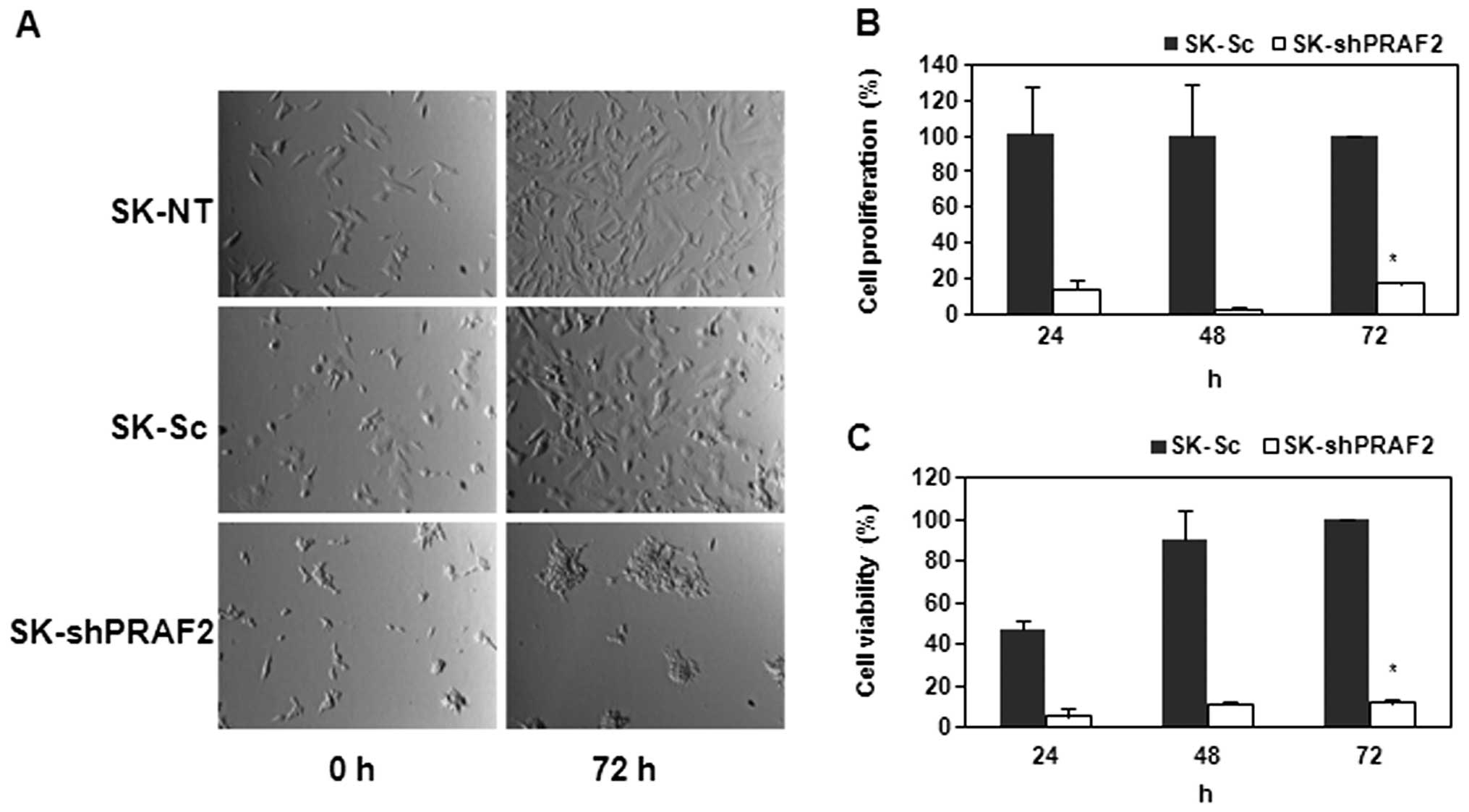

Upon establishment of this PRAF2 knockdown NB cell

line, we investigated the effect of PRAF2 downregulation in these

NB cells by observing their phenotypic morphology and viability. To

this end, we seeded equal numbers of shPRAF2-and Sc-expressing

cells. Strikingly, we found that SK-shPRAF2 cells were less able to

grow confluent than both SK controls cells, non-transfected (-NT)

and scrambled (-Sc) control cells, after 72-h incubation (Fig. 3A). These data suggest down

regulation of PRAF2 inhibits cell growth and/or adhesion in NB

cells.

PRAF2 is essential for NB cell

proliferation

We therefore examined whether PRAF2 knockdown

regulates the proliferation of NB cells. First, we used the MTS

assay to determine the cell viability of SK-shPRAF2 compared to

that of SK control cells. As shown in Fig. 3C, SK-Sc showed steadily increasing

metabolic activity indicative of viable cell growth, while

SK-shPRAF2 remained at very low levels even after 72-h incubation.

We further investigated the effect of PRAF2 down-regulation in

SK-N-SH cell proliferation using the BrdU cell proliferation assay.

We found that downregulation of PRAF2 significantly suppressed the

cell proliferation of SK-N-SH cells by ∼80% compared to that of

SK-Sc after 24, 48 or 72 h (Fig.

3B). The steady decrease in BrdU incorporation suggests that

SK-shPRAF2 cells are severely defective in DNA synthesis and hardly

undergo cell division. Together, these results show that silencing

PRAF2 suppresses the proliferation of NB cells. Similar

observations were made with another stable NB cell line (data not

shown).

PRAF2 regulates G1-S cell

cycle transition in NB

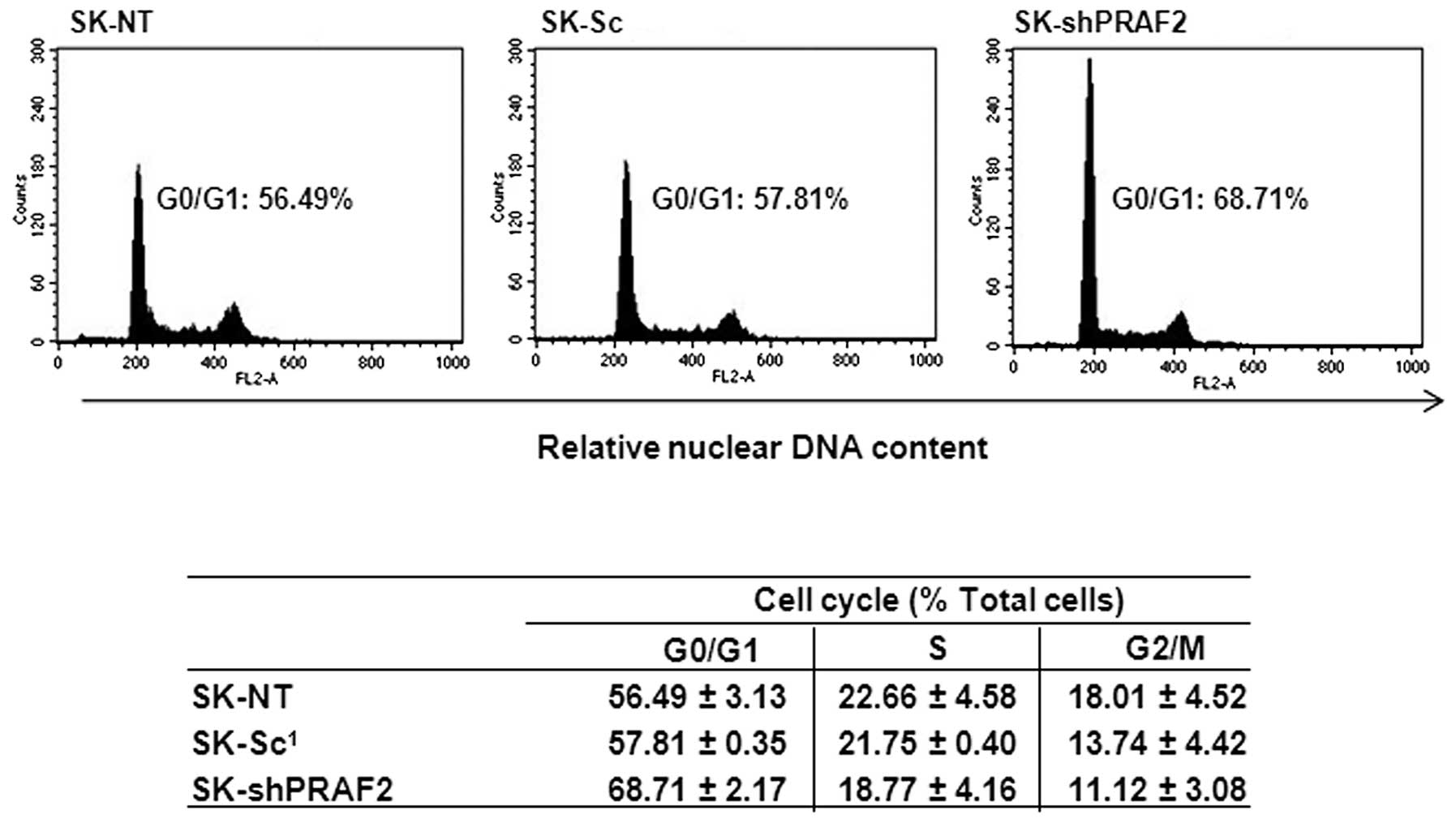

Since PRAF2 downregulation effectively suppresses

the proliferation rate of NB cells and also seems to inhibit DNA

synthesis, we wanted to further analyze if this effect is linked

with cell cycle abrogation. In order to examine this, we performed

cell cycle analysis by PI staining and FACS analysis of SK-shPRAF2

nuclei 24 h after seeding and compared with those of SK control

cells -NT and -Sc. As shown in Fig.

4, we observed an increase in G1 population (∼68%)

in the SK-shPRAF2 cells compared with SK-NT (∼55%) and SK-Sc (∼58%)

control cells. The increase in G1 was accompanied by a

similar decrease in S and G2/M phase. No changes were apparent in

the sub-G1 fraction, suggesting the observed decrease in

proliferation was not due to an increase in apoptosis. Together,

these data strongly indicate that PRAF2 downregulation inhibits the

proliferation of NB cells by causing a G1 cell cycle

arrest, explaining at least part of the decreased cell growth

observed in Fig. 3.

PRAF2 downregulation inhibits NB cell

migration

The results obtained in Fig. 4 clearly suggest that PRAF2

expression was important for NB cell growth, but decreased

confluence, observed in Fig. 3

could also result from lower cell adhesion efficiency. PRAF2

expression is highest in ST4 NB tumors (Fig. 1E), which often metastasize. We

investigated PRAF2 expression in correlation with NB metastasis.

Strikingly, PRAF2 expression was notably higher in both bone and

bone marrow-metastasized tumors (P=8.5×10−5; Fig. 5) than in local tumors. These

results show that high level of PRAF2 is also associated with NB

metastasis.

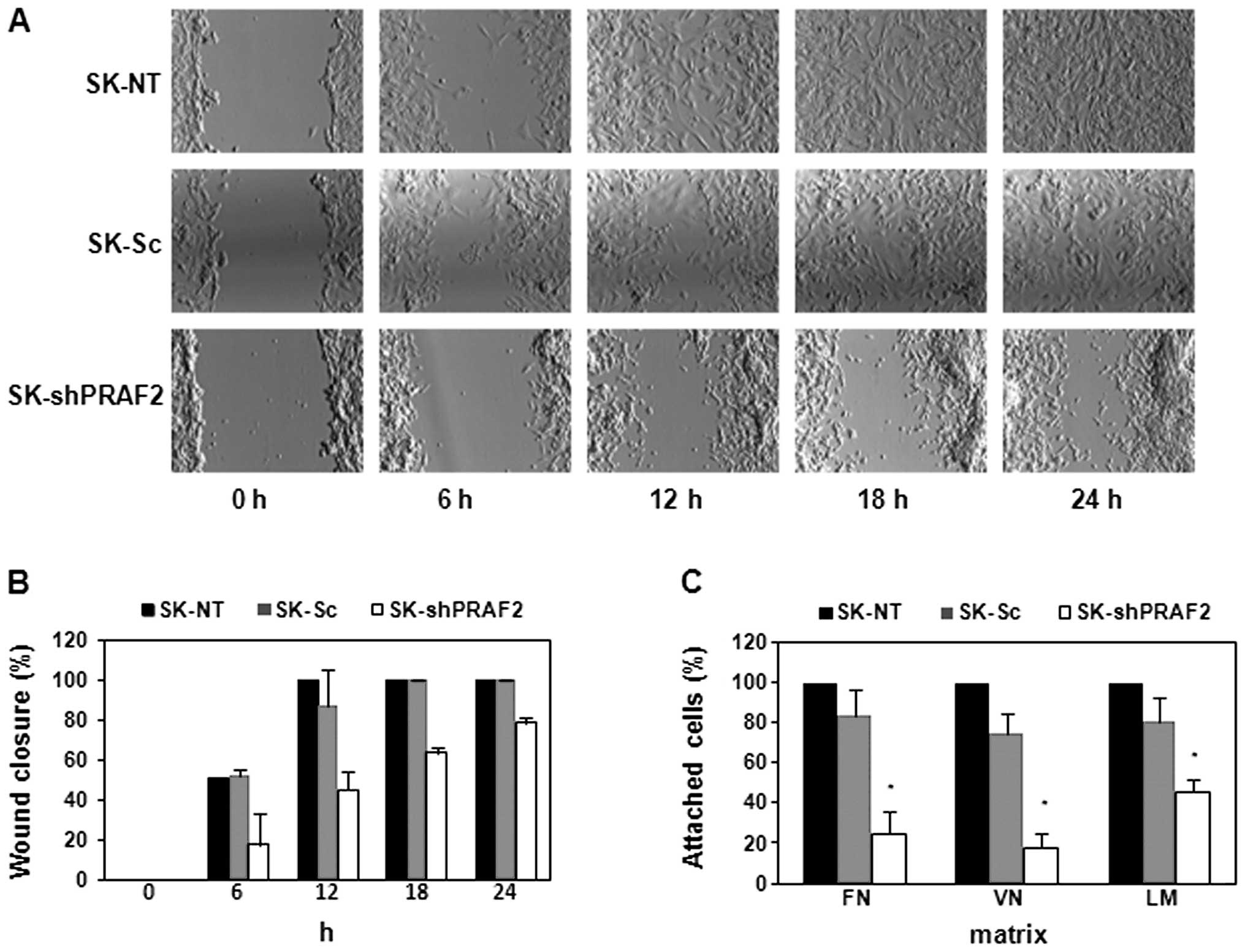

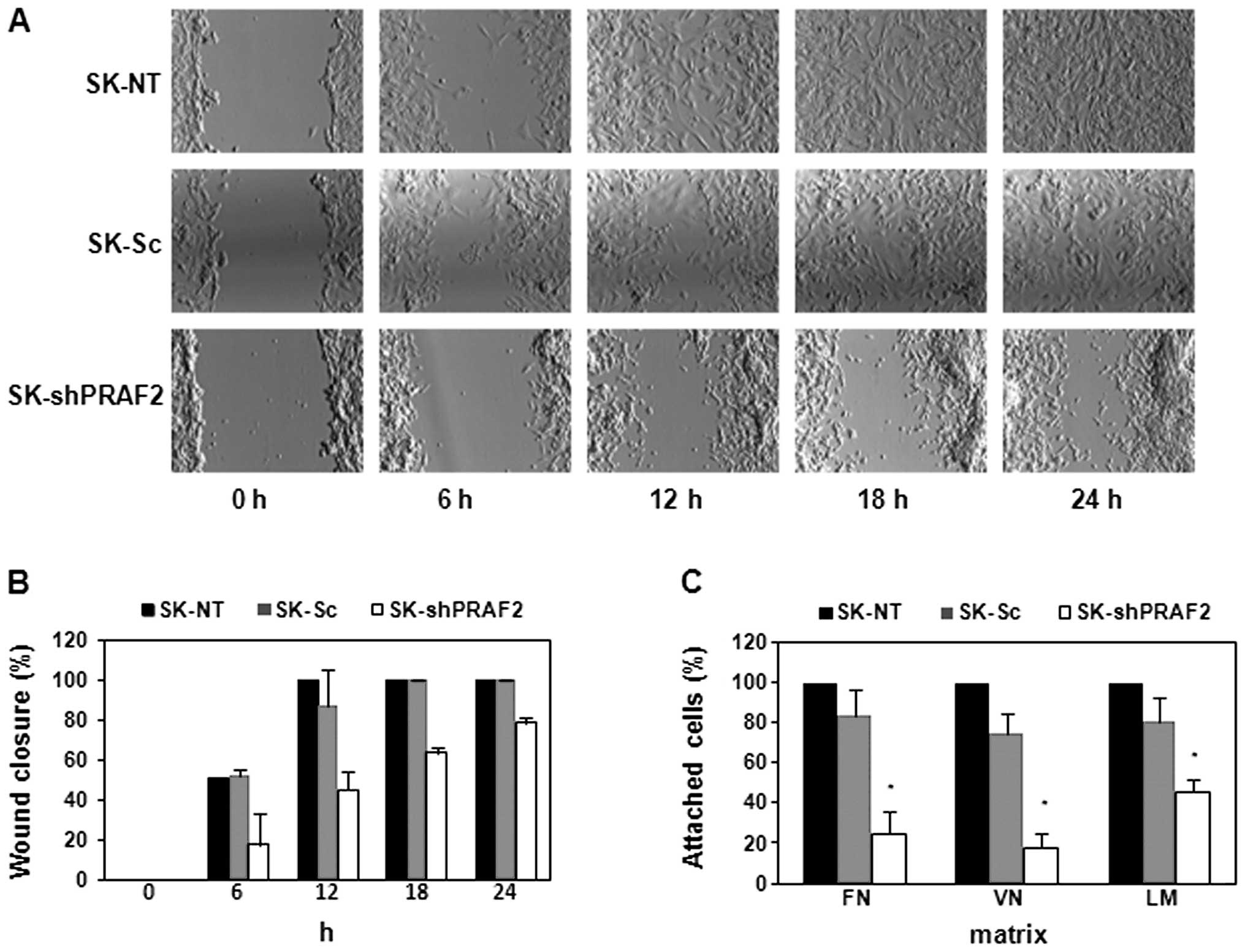

By using the SK-shPRAF2 cells, we tested the effect

of PRAF2 knockdown on NB cell migration in vitro. We used

the wound-healing assay to investigate and compare the migration

ability of SK-shPRAF2 cells with -NT and -Sc control cells. As

shown in Fig. 6A and B, PRAF2

knockdown produced SK-N-SH cells with a marked delay in wound

closure, >24 h, while both -NT and -Sc control cells showed

complete wound closure after only 12-h incubation. Finally, we

examined whether downregulation of PRAF2 regulates NB cell

attachment on fibronectin, vitronectin and laminin using an

adhesion assay. The results show that PRAF2 knockdown considerably

decreased the cell attachment ability of SK-N-SH cells on all three

substrates: fibronectin (∼75%), vitronectin (∼80%) and laminin

(∼55%) (Fig. 6C). These data

confirm a role for PRAF2 in regulating NB tumor cell migration and

suggest involvement of PRAF2 in high-stage NB, providing urgently

needed clues for unraveling the mechanisms involved in NB

metastasis.

| Figure 6PRAF2 downregulation regulates NB

cell migration and attachment. SK-N-SH cells (SK-shPRAF2, SK-NT and

SK-Sc) were grown to full confluence in 6-well plates and subjected

to monolayer wounding (A and B), or were seeded in fibronectin-

(FN), vitronectin- (VN), or laminin (LM)-coated 96-well plates,

allowed to grow for 3 h and subjected to an adhesion assay (C).

After monolayer wounding, photomicrographs were taken at 0, 6, 12,

18 and 24 h. The wound healing in cells with silenced PRAF2

(SK-shRPAF2) was significantly slower than in SK-NT or SK-Sc

control cells (A). The wound-healing assays were quantified by

measurement of the percentage of the gap closed during the time

indicated (B). While SK-shPRAF2 cells required >24 h,

identically treated SK-NT and SK-Sc control cells closed the gap

within 12 h. The cell attachment of cells was determined using an

adhesion assay with three different matrices (FN, VN and LM) and

coloring with crystal violet (C). SK-shPRAF2 cells showed

significantly lower adhesion capability than the SK-NT or SK-Sc

controls cells. Each assay was performed in duplicate and data are

presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments (n=6).

*P<0.005 compared with control cells. |

Discussion

Previously, our lab found that PRAF2 expression is

higher in neuroblastic tumors than in all other cancers examined

(17). To explore the role of

PRAF2 in NB, the most aggressive neuroblastic tumor, we

investigated PRAF2 expression in a new cohort of NB tumors. Here,

we found that PRAF2 is significantly correlated with unfavorable

genetic and clinical hallmarks of NB. PRAF2 tumor expression is

notably higher in NB patients with tumor MYCN amplification,

in high-risk patients of >1 year-old or with high-stage disease

and in patients who died during follow-up. We therefore

hypothesized that PRAF2 plays an important role in tumorigenesis

and progression of NB.

Cancer is regularly defined as a disease of the cell

cycle: the uncontrollable proliferation of tumor cells is often due

to the deregulation of cell cycle machinery (23,24)

and NB tumors can have mutations in several cell cycle checkpoints,

most notably the G1-S transition (25). Since PRAF2 is overexpressed in NB

tumor cells, we used RNAi to knock down the level of PRAF2 in NB

cells and examine possible cellular viability effects. Strikingly,

PRAF2 knockdown NB cells showed decreased cell growth in comparison

with control NB cells. This is in apparent contrast with a recent

study in which no growth retardation was detected when expression

of PRAF2 was depleted (23). We

also noted an increase of cell population at G1 phase in

PRAF2 knockdown NB cells. Therefore, these data suggest that high

PRAF2 expression, in cooperation with the decreased G1-S

threshold caused by mutated checkpoint molecules, allows NB tumor

cells to leave the G1 phase and continue the cell

cycle.

Previous studies showed that reduction of PRAF3, a

PRAF2 homologue, enhances adhesion and invasion of melanoma cells

in vitro and melanoma metastasis in vivo by

regulating integrin αvβ3 (26). We

therefore evaluated if PRAF2 is also involved in NB metastasis.

Cancer metastasis is a complex process, in which tumor cells need

to detach from their primary site, migrate, adhere at a distal

location and invade this new host environment (24, 27). Interestingly, Affymetrix analysis

showed that overexpression of PRAF2 is strongly correlated with NB

metastasis. In contrast to the role of PRAF3 in melanoma cell

migration, we found that PRAF2 downregulation delays NB cell

migration. PRAF3 expression is associated with good prognosis in NB

(data not shown). Moreover, depletion of PRAF2 decreased

cell-matrix attachment ability of NB cells in fibronectin,

vitronectin and laminin, three of the major components of

extracellular matrix.

PRAF family proteins act by virtue of their

Rab-binding activity. Most probably therefore, PRAF2 is involved in

the formation of exosome-like vesicles, which were recently

discovered as a novel mechanism in tumor metastasis that depend on

Rab function and cause changes in cell cycle, extracellular matrix,

as well as migration/invasion (28,29).

Indeed, we found that PRAF2 expression is correlated with these

processes. In addition, the expression of several crucial

exosome-associated Rab and extracellular matrix genes correlates

with that of PRAF2 in NB (data not shown). Future studies will

therefore investigate the role of PRAF2 in this mechanism in

detail.

In conclusion, we found a clinical implication of

PRAF2 expression in a cohort of 88 NB tumors. These observations

were validated in vitro by silencing PRAF2 in NB cells which

led to reduced proliferation, migration and cell-matrix adhesion.

In contrast to PRAF3 which inhibits cell migration and induces

apotosis (16,30), our experiments suggest that the

novel PRAF2 protein plays a prominent role in NB tumorigenesis and

metastasis and thus may be of value as a novel target in NB.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge Drs

Dana-Lynn Koomoa, Tamas Borsics, Joe Ramos, Florian Sulzmaier,

Joanna Gawecka and Ms. Sarah Hampe for their contributions and

expert technical advice. This study was supported by institutional

funds from the College of Pharmacy and the University of Hawaii

Cancer Center to A.S.B. and grants UVA 2005–3665 from the Dutch

Cancer Society ‘KWF Kankerbestrijding’ and EU COST BM0805 to

D.G.

References

|

1

|

Brodeur GM: Neuroblastoma: biological

insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:203–216. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R and Cohn

SL: Neuroblastoma. Lancet. 369:2106–2120. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schweneker M, Bachmann AS and Moelling K:

JM4 is a four-transmembrane protein binding to the CCR5 receptor.

FEBS Lett. 579:1751–1758. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fo CS, Coleman CS, Wallick CJ, Vine AL and

Bachmann AS: Genomic organization, expression profile, and

characterization of the new protein PRA1 domain family, member 2

(PRAF2). Gene. 371:154–165. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bachmann AS, Duennebier FF and Mocz G:

Genomic organization, characterization, and molecular 3D model of

GDE1, a novel mammalian glycerophosphoinositol phosphodiesterase.

Gene. 371:144–153. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Koomoa DL, Go RC, Wester K and Bachmann

AS: Expression profile of PRAF2 in the human brain and enrichment

in synaptic vesicles. Neurosci Lett. 436:171–176. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Borsics T, Lundberg E, Geerts D, et al:

Subcellular distribution and expression of prenylated Rab acceptor

1 domain family, member 2 (PRAF2) in malignant glioma: influence on

cell survival and migration. Cancer Sci. 101:1624–1631. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sivars U, Aivazian D and Pfeffer SR: Yip3

catalyses the dissociation of endosomal Rab-GDI complexes. Nature.

425:856–859. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Compton SL and Behrend EN: PRAF1: a Golgi

complex trans-membrane protein that interacts with viruses. Biochem

Cell Biol. 84:940–948. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Compton SL, Kemppainen RJ and Behrend EN:

Prenylated Rab acceptor domain family member 1 is involved in

stimulated ACTH secretion and inhibition. Cell Signal.

21:1901–1909. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim JT, Cho MY, Choi SC, et al: Prenylated

Rab acceptor 1 (PRA1) inhibits TCF/beta-catenin signaling by

binding to beta-catenin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 349:200–208.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li LY, Shih HM, Liu MY and Chen JY: The

cellular protein PRA1 modulates the anti-apoptotic activity of

Epstein-Barr virus BHRF1, a homologue of Bcl-2, through direct

interaction. J Biol Chem. 276:27354–27362. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu HP, Wu CC and Chang YS: PRA1 promotes

the intracellular trafficking and NF-kappaB signaling of EBV latent

membrane protein 1. EMBO J. 25:4120–4130. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lin CI, Orlov I, Ruggiero AM, et al:

Modulation of the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAC1 by the

interacting protein GTRAP3–18. Nature. 410:84–88. 2001.

|

|

15

|

Mao WG, Liu ZL, Chen R, Li AP and Zhou JW:

JWA is required for the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic effects

of all-trans retinoic acid in HeLa cells. Clin Exp Pharmacol

Physiol. 33:816–824. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chen H, Bai J, Ye J, et al: JWA as a

functional molecule to regulate cancer cells migration via MAPK

cascades and F-actin cytoskeleton. Cell Signal. 19:1315–1327. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Geerts D, Wallick CJ, Koomoa DL, et al:

Expression of prenylated Rab acceptor 1 domain family, member 2

(PRAF2) in neuroblastoma: correlation with clinical features,

cellular localization, and cerulenin-mediated apoptosis regulation.

Clin Cancer Res. 13:6312–6319. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Valster A, Tran NL, Nakada M, Berens ME,

Chan AY and Symons M: Cell migration and invasion assays. Methods.

37:208–215. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Fardin P, Barla A, Mosci S, et al: A

biology-driven approach identifies the hypoxia gene signature as a

predictor of the outcome of neuroblastoma patients. Mol Cancer.

9:1852010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Revet I, Huizenga G, Chan A, et al: The

MSX1 homeobox transcription factor is a downstream target of PHOX2B

and activates the Delta-Notch pathway in neuroblastoma. Exp Cell

Res. 314:707–719. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE, et al:

NCBI GEO: archive for high-throughput functional genomic data.

Nucleic Acids Res. 37:D885–D890. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Bewick V, Cheek L and Ball J: Statistics

review 12: survival analysis. Crit Care. 8:389–394. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vento MT, Zazzu V, Loffreda A, et al:

Praf2 is a novel Bcl-xL/Bcl-2 interacting protein with the ability

to modulate survival of cancer cell. PLoS One. 5:e156362010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Malumbres M and Barbacid M: Cell cycle,

CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:153–166.

2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Molenaar JJ, Koster J, Ebus ME, et al:

Copy number defects of G1-cell cycle genes in neuroblastoma are

frequent and correlate with high expression of E2F target genes and

a poor prognosis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 51:10–19. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Bai J, Zhang J, Wu J, et al: JWA regulates

melanoma metastasis by integrin alphaVbeta3 signaling. Oncogene.

29:1227–1237. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Hynes RO: Metastatic potential: generic

predisposition of the primary tumor or rare, metastatic variants -

or both? Cell. 113:821–823. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hendrix A, Westbroek W, Bracke M and De

Wever O: An ex(o) citing machinery for invasive tumor growth.

Cancer Res. 70:9533–9537. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Peinado H, Lavotshkin S and Lyden D: The

secreted factors responsible for pre-metastatic niche formation:

old sayings and new thoughts. Semin Cancer Biol. 21:139–146. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Shi GZ, Yuan Y, Jiang GJ, et al: PRAF3

induces apoptosis and inhibits migration and invasion in human

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 12:972012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|