Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most

common cancer worldwide and the third most common cause of death

from cancer (1). Many studies have

shown that hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a risk factor for

the development of HCC (2,3). The multifunctional oncoprotein HBx,

encoded by the smallest open reading frame of the HBV and its

interaction with signal transduction pathways are involved in the

initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis (3). In our previous study we reported that

the Notch signaling pathway is activated in HBx-transformed L02

cells and is involved in the malignant transformation of normal

hepatic cells (4). However, the

role of Notch signaling in the development of HCC has not been

fully elucidated and its relationship with HBx still requires

further exploration.

The evolutionarily conserved Notch signaling pathway

mediates cell-to-cell communication and is involved in mediating

binary cell fate decisions. There are four mammalian Notch

receptors (Notch1-4) and two groups of ligands, jagged (JAG1 and

JAG2) and δ-like protein (DLL1, 3 and 4) (5). Upon binding to Notch, the receptor is

cleaved by ADAM10 or ADAM17 (formerly, a disintegrin and

metalloproteinase domain 10 and 17) (6,7).

There is then an intramembranous cleavage by the γ-secretase

protease complex, resulting in the release of the Notch receptor’s

intracellular domain (NICD) (8).

The NICD subsequently translocates to the nucleus, binds to the

transcription factor CSL (i.e., CBF1/RBP-Jκ/suppressor of

hairless/LAG1), which then activates the transcription of a group

of downstream genes (9) including

pro-oncogenes (p21 and c-Myc), cyclin D1, cyclin A and the subunits

of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) (10–14).

Our previous research indicated that Notch signaling might be one

of the downstream targets through which HBx functions as an

oncoprotein (4).

In addition, HBx interacts with many other signal

pathways in the initiation of hepatocarcinogenesis, including

AKT/PKB, ERK1/2, SAPK, NF-κB signal transduction pathway (15). Many researchers have also shown

that HBx upregulates the activity of the NF-κB transcription factor

(16–18). The NF-κB pathway comprises a family

of transcription factors, namely p50, p52, p65 (RelA), RelB and

c-Rel (19), which homo- or

heterodimerize to form transcriptional regulatory complexes. All

five of these transcription factors contain Rel homology domains

that participate in dimerization and DNA binding. The IκB (i.e.,

nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells

inhibitor) family, including IκBα, IκBβ, IκBɛ, Bcl-3, p100 (p52

precursor) and p105 (p50 precursor), are the inhibitors of NF-κB

pathway, each with different roles (20). Activation of NF-κB typically

involves the phosphorylation of IκB by the IκB kinase (IKK)

complex, which results in IκB degradation (20). This releases NF-κB and allows it to

translocate freely to the nucleus (20).

Accumulating evidence indicates that the Notch and

NF-κB pathway are closely related and that they contribute to the

pathogenesis of malignancies. The inhibitor of κB kinase 2 (Ikk2),

a component of the canonical NF-κB signaling pathway, synergizes

with basal Notch signaling to upregulate transcription of primary

Notch target genes, resulting in suppression of anti-inflammatory

protein expression and promotion of pancreatic carcinogenesis in

mice (21). In MDA-MB-231

triple-negative breast cancer cells, genistein inhibited the growth

of cells by inhibiting NF-κB activity via the Notch-1 signaling

pathway in a dose-dependent manner (22). Schwarzer et al(23) reported that Notch is an essential

upstream regulator of alternative NF-κB signaling and confirmed

crosstalk between both pathways in B cell-derived Hodgkin and

Reed-Sternberg cells. However, little is known about the

involvement of the Notch and NF-κB pathways in the pathogenesis of

HBx-associated HCC. This requires further investigation.

In this study we investigated whether HBx directly

binds with components of the Notch and NF-κB pathways and explored

evidence of interactions between these two pathways.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The human non-tumor hepatic cell line L02/HBx, which

was derived from L02 cells via transfection with an HBx expression

plasmid, was successfully established previously (24). The cells were cultured in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA)

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY,

USA) and 250 μg/ml G418 (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China) and

maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C under a 5%

CO2 atmosphere.

Immunofluorescence assays

Immunofluorescence assays were conducted to

visualize HBx, NICD and cell nuclei in L02/HBx cells. L02/HBx cells

were cultured on glass cover slips for 24 h and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde. The fixed cells were incubated with anti-HBx and

anti-NICD (both 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA)

for 12 h at 4°C. They were then incubated in CY3-conjugated goat

anti-mouse IgG and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated

goat anti-rabbit IgG (both 1:100; Boster, China) for 1 h to stain

the HBx and NICD proteins red and green, respectively. The nuclei

were stained blue with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI;

Boster). The stained cells were observed under a FluoView 1000

laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Japan).

Co-immunoprecipitation (coIP) assays

CoIP was performed to investigate physical

interactions between HBx and components of the Notch signaling

pathway (NICD and JAG1), components of the NF-κB signaling pathway

(p65 and p50), or IκBα (inhibitor of NF-κB pathway) in L02/HBx

cells. L02/HBx cells were lysed with RIPA Lysis buffer and

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (KeyGEN Biotech, China) and the

lysates pretreated with Protein G-Agarose (Santa Cruz) to remove

non-specifically bound proteins. After centrifugation, one third of

the supernatants were immediately boiled for western blot analysis

using antibodies directed serially against NICD, JAG1, p65, or p50,

or IκBα as a positive control. The remaining supernatants were

incubated for 2 h at 4°C with 1 μg of non-immune mouse IgG

(for the negative control) or mouse anti-HBx (experimental group;

Santa Cruz). Then, the mixtures were incubated from 1 h to

overnight at 4°C with 20 μl Protein G-Agarose beads (Santa

Cruz). The immuno-complexes were extensively washed with

phosphate-buffered saline and samples were boiled in

electrophoresis sample buffer, then assayed via western blotting

using antibodies directed against NICD, JAG1, p65, p50, or

IκBα.

DAPT treatment

To repress normal activity of the Notch signaling

pathway, cells were treated with the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT.

DAPT was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and

dissolved in 100% dimethyl sulf-oxide (DMSO; Sigma) to make a stock

solution of 10 mM, which was then diluted in culture medium to

obtain the desired final concentration of 20 μM. DMSO was

diluted in culture medium to a final percentage of 0.05% without

DAPT. Untreated cells were incubated in the culture medium without

any additives. Cells with or without DAPT were cultured for 48 h.

Total RNA or protein was then extracted.

Notch1 small interfering RNA (siRNA)

transfection

To block Notch signaling, in another experiment

L02/HBx cells were transfected with Notch1 siRNA. L02/HBx cells

were seeded in 6-well plates. The next day the cells (30–50%

confluence) were treated with Notch1 siRNA (sense

5′-GGUGUCUUCCAGAUCCUGAdTdT-3′; antisense

3′-dTdTCCACAGAAGGUCUAGGACU-5′) or control siRNA (which does not

match any known mammalian GenBank sequences). Notch1 siRNA and

control siRNA were purchased from RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). Cells

were transiently transfected with Notch1 siRNA or control siRNA

using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). Media were replaced 6 h

after transfection. Cells were allowed to grow for 48 h and

harvested for further analysis.

Quantitative real-time PCR (QRT-PCR)

analysis

To quantify the expression of the genes of interest,

total RNA was isolated from cultured cells using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and cDNA was synthesized from 5

μg of total RNA using Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV)

reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and

oligo(dT)18 as the primer. Real-time quantitative PCR

was carried out using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (DRR041A, Takara, Japan).

Each real-time PCR (20.0 μl) contained 2.0 μl of

cDNA, 10.0 μl of 2X SYBR Premix Ex Taq, 7.2 μl

nuclease-free water and primers at a final concentration of 0.2

μM. Real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reactions (qRT-PCR) were performed in a Step One Real-Time PCR

system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The expression of RNA was

determined from the threshold cycle (Ct) and the relative

expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

All standards and samples were assayed in triplicate. The primer

sequences used to amplify specific target genes (p65, p50, IκBα,

β-actin) are listed in Table

I.

| Table IPrimer sequences for real-time

polymerase chain reaction analysis. |

Table I

Primer sequences for real-time

polymerase chain reaction analysis.

| Gene | Primer

sequence | PCR product

(bp) | GenBank accession

no. |

|---|

| p65 | f:

5′-GGGGACTACGACCTGAATG-3′ | 118 | NM_021975.3 |

| r:

5′-GGGCACGATTGTCAAAGAT-3′ | | |

| p50 | f:

5′-CGCGGTGACAGGAGACGTGAA-3′ | 162 | NM_003998.2 |

| r:

5′-TGAGAATGAAGGTGGATGATTGCTAATGT-3′ | | |

| IκBα | f: 5′

-TCCACTCCATCCTGAAGGCTACCAA-3′ | 108 | NM_020529.2 |

| r:

5′-GACATCAGCACCCAAGGACACCAAA-3′ | | |

| β-actin | f:

5′-GTTGCGTTACACCCTTTCTTG-3′ | 157 | NM_001101.3 |

| r:

5′-GACTGCTGTCACCTTCACCGT-3′ | | |

Extraction of nuclear and cytoplasmic

proteins

To quantify protein expression changes in the

cytoplasm and nuclei of L02/HBx cells after treatment with the

Notch signal inhibitor DAPT or Notch1 siRNA, L02/HBx cells were

treated with DAPT or DMSO for 48 h, or with Notch1 siRNA or control

siRNA for 48 h. Proteins were subsequently extracted in accordance

with the instructions in a nuclear and cytoplasmic protein

extraction kit (KeyGEN Biotech). The nuclear and cytoplasmic

proteins were measured using the bicinchoninic acid method (Boster,

Wuhan, China). The samples were stored at −80°C and assayed via

western blotting and electrophoretic mobility shift assay

(EMSA).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed and the lysates were subjected to

SDS/PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene

fluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The blotted

membranes were blocked and subsequently incubated with rabbit

anti-JAG1 and rabbit anti-NICD (both 1:400; Santa Cruz), rabbit

anti-p65 and rabbit anti-p50 (both 1:1,000; Proteintech Group,

Chicago, IL, USA), rabbit anti-IκBα (1:750; Proteintech) and rabbit

anti-actin (1:1,000; Proteintech) according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labeled

secondary antibody (1:4,000; Santa Cruz), visualization was

performed with an enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford,

IL, USA) and exposure to X-ray film (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA).

Immunoblotting with anti-actin antibody was used as an internal

control to confirm equivalent protein loading. Western blot

experiments were repeated ≥3 times. The relative intensity of each

protein band was assessed using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA).

EMSA for measuring NF-κB activity

To evaluate changes in NF-κB activation after cells

were treated with the Notch signal inhibitor DAPT (as reflected by

DNA-binding activity), cell nuclear extracts from L02/HBx cells,

L02/HBx cells treated with DMSO (0.05%), or L02/HBx cells treated

with DAPT (20 μM) were subjected to EMSA. In addition, a

reaction system sample without cell nuclear extracts was used as a

blank control and with untreated positive cell nuclear extracts

(Pierce) as a positive control. EMSA was performed by incubating 10

μg of nuclear protein extract with biotin-labeled NF-κB

oligonucleotide (Pierce). The mixture included 1 μg of poly

(dI-dC) in a binding buffer. The DNA-protein complex formed was

separated from free oligonucleotides on a 6.0% polyacrylamide gel

using buffer (45 mM Tris, 45 mM boric acid pH 8.3 and 1 mM

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) for electrophoretic transfer of

binding reactions to a nylon membrane and then transferred DNA was

UV cross-linked to a membrane at 254 nm and exposed to X-ray film.

The relative intensity of each protein band was assessed using

Quantity One software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Statistical analyses

SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS for Windows, Inc.

and Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All

results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean.

Statistical analysis was performed using standard one-way ANOVA or

one-way ANOVA for repeated measures, followed by the least

significant difference post hoc test. Bonferroni’s

correction was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. A 2-tailed

Student’s paired t-test was also used to compare the difference in

values between 2 groups. P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant.

Results

Co-localization and physical interactions

of Notch1 or NF-κB with HBx

To investigate the potential association between

Notch1 or NF-κB and HBx in the development of HCC, we performed

immunofluorescence and coIP assays with HBx-transfected L02 cells

(L02/HBx). In the L02/HBx cells, nuclei, HBx and NICD were stained

blue, red and green, respectively (Fig. 1A, a–c). Yellow areas in

dual-labeling experiments indicated overlapping of red and green

fluorescent labels (Fig. 1A, d),

suggesting the co-localization of NICD with HBx.

| Figure 1Co-localization and physical

interactions between Notch1 or NF-κB HBx in L02/HBx cells. (A)

Confocal micrograph of co-localization of NICD and HBx. Nuclei were

stained with DAPI (blue) (a), HBx protein was stained with CY3

(red) (b) and the NICD protein was stained with FITC (green) (c).

The yellow indicated overlapping areas of red and green (d)

(magnification ×100). (B) CoIP assay of interactions between NICD,

JAG1, p65, p50, or IκBα and HBx. Data shown are representative of 3

independent experiments. Specific interaction was found between

NICD and HBx and not between JAG1, p65, p50, or IκBα and HBx. PC,

positive control; anti-HBx, coIP proteins treated with anti-HBx;

NC, negative control; coIP proteins treated with non-immune mouse

IgG. |

Then we investigated the possible physical

interaction via the coIP assay. Compounds from L02/HBx cells were

immunoprecipitated with anti-HBx or non-immune mouse IgG, which

were then subjected to western blotting with anti-NICD, anti-JAG1,

anti-p65, anti-p50 and anti-IκBα. NICD was observed to

co-immunoprecipitate with HBx (Fig.

1B). No specific interaction was found between JAG1, p65, p50

or IκBα and HBx, or the protein immunoprecipitated with non-immune

IgG, which indicates the specificity of the NICD-HBx

interaction.

Downregulation of NICD decreases NF-κB

DNA-binding activity

NF-κB (p50/p65) is a ubiquitous, constitutive and

inducible heterodimer and the DNA binding activity of NF-κB

traditionally refers to the p50/p65 (p50/RelA) heterodimer-mediated

binding to DNA (25). In the

present study, we inhibited Notch1 using DAPT in L02/HBx cells

(Fig. 3) to examine the effect of

Notch on NF-κB DNA binding activity. Nuclear proteins from

untreated L02/HBx, DMSO-treated L02/HBx cells and DAPT-treated

L02/HBx cells were subjected to an EMSA for NF-κB DNA-binding

activity (Fig. 2). It was found

that downregulation of NICD via DAPT significantly decreased the

binding of NF-κB p65 to its target gene promoter. These results

revealed that after translocating into the nucleus, NICD could

function as a regulator to regulate the NF-κB DNA-binding activity,

which provided evidence for a mechanistic crosstalk between Notch

and NF-κB in HCC.

Inhibition of NICD by DAPT decreases the

activation of NF-κB pathway

To investigate whether HBx acted through Notch

signaling to activate the NF-κB pathway, we inhibited the Notch

pathway by using the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT, which blocks the

processing of transmembrane (TM)-Notch1 to Notch1-IC and has been

widely used for experimental studies of Notch signaling (4). We treated L02/HBx cells with DAPT (20

μM) for 48 h and then used western blotting to determine

NICD protein expression. It turned out that NICD decreased

significantly after DAPT treatment (Fig. 3). Moreover, our data also showed

that inhibition of Notch1 decreased NF-κB DNA-binding activity in

L02/HBx cells.

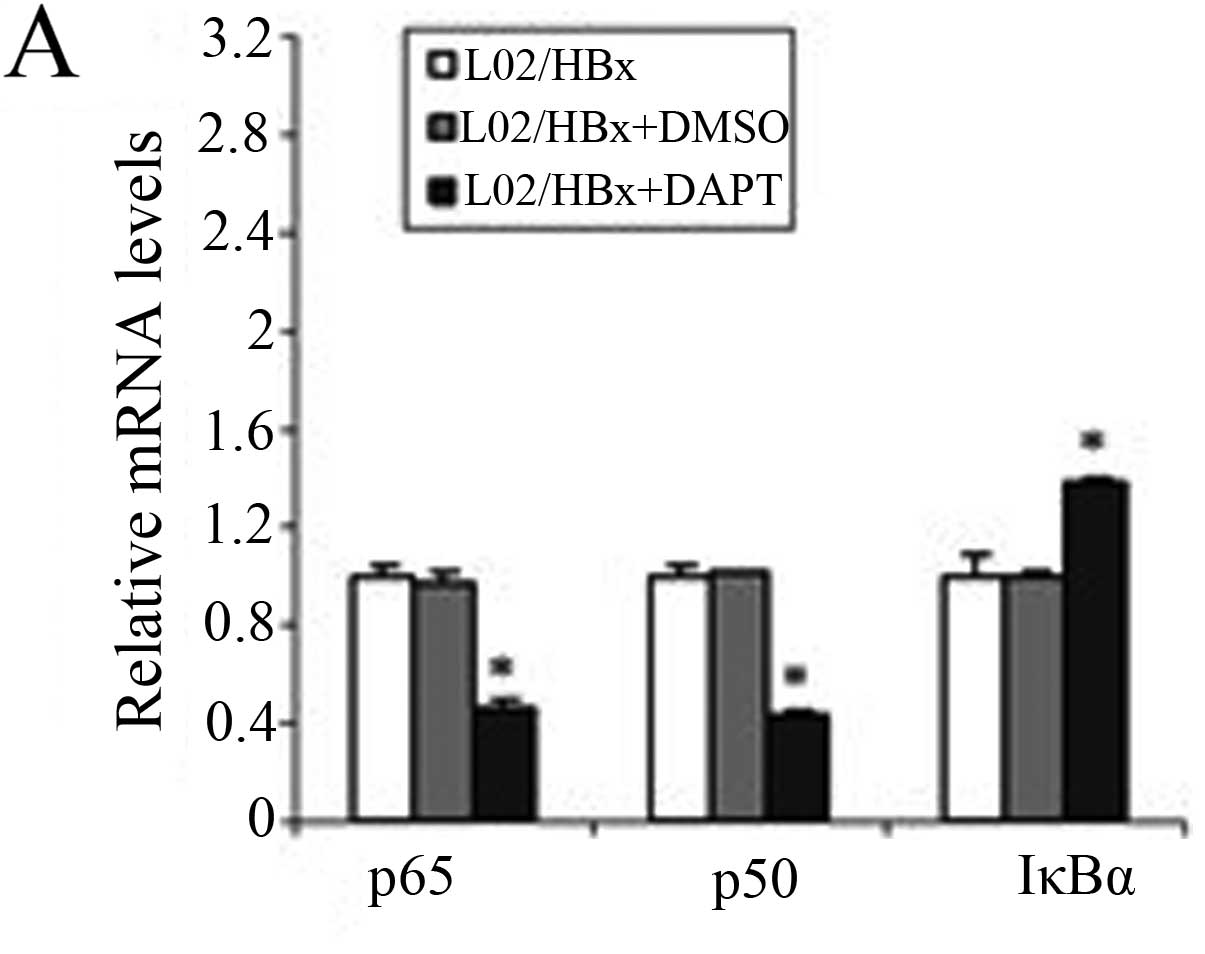

To further study the importance of activated Notch

signaling for the NF-κB pathway, we used qRT-PCR and western blot

analysis to observe changes in the NF-κB pathway after inhibition

of Notch1 (Fig. 4). The mRNA

levels of p65 and p50 were significantly decreased (P<0.001) and

the IκBα mRNA level was increased (P<0.001; Fig. 4A).

The protein levels of NF-κB were then evaluated

using western blot analysis and found that the total protein level

of IκBα was increased in L02/HBx cells after treating with DAPT

(Fig. 4B). No significant change

was observed in p65 or p50 proteins in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4C) and the nuclear extract levels of

p65 and p50 were decreased (Fig.

4D). These results indicated that inhibition of Notch1

suppressed the activation of the NF-κB pathway in L02/HBx cells by

affecting the transcription of the components of NF-κB and

inhibiting the nuclear transport of NF-κB dimers. This confirmed

that in L02/HBx cells HBx induced Notch signaling, which is

important for stimulating the NF-κB pathway.

Inhibition of Notch1 by specific siRNA

also decreases the activation of NF-κB pathway

Notch1 siRNA-transfected L02/HBx cells showed

significantly reduced Notch1 mRNA and protein expression

(P<0.001; Fig. 5A and B). We

then detected the expression of NF-κB pathway proteins in the

Notch1 siRNA-transfected L02/HBx cells. In the cytoplasm, p50 and

p65 proteins were not changed compared with either the blank or

control groups (Fig. 5C). However,

these proteins were decreased notably in the nucleus (Fig. 5D).

Consistent with the above results, Q-PCR also showed

that p50 and p65 mRNA levels were significantly decreased

(P<0.001; Fig. 5A). Moreover,

the total protein level of IκBα was increased in the Notch

siRNA-transfected L02/HBx cells (Fig.

5B) and results of the Q-PCR showed that the IκBα mRNA levels

were also increased (Fig. 5A).

Therefore, down-regulation of Notch1 suppressed the activation of

p65 and p50, accompanied by an increase in IκBα. Altogether these

results showed that the NF-κB pathway was regulated by the Notch

signaling pathway.

Discussion

Stably HBx-expressing L02/HBx cells were previously

established and the data indicated that HBx promoted growth and

malignant transformation of the human non-tumor hepatic L02 line

(24). To explore whether

associations among Notch and NF-κB may be involved in the malignant

transformation of hepatic cells induced by HBx, we investigated the

interaction between HBx and Notch, or between HBx and NF-κB, in the

present study. We found that NICD interacted with HBx directly,

while the evidence that HBx acts directly through NF-κB was

lacking. Thus, HBx affected Notch signaling by directly binding to

the NICD upon its release from the cleaved Notch receptor, whereas

HBx did not have an immediate interaction with NF-κB. We then

continued to explore whether the Notch pathway receptor Notch1 and

the NF-κB pathway are interrelated. We found that downregulation of

Notch1 via the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT decreased the ability of

NF-κB to bind to DNA. RNA-mediated or DAPT inhibition of the Notch1

signaling pathway in HBx-transfected L02 cells reduced NF-κB

expression and enhanced IκBα expression. These results showed that

NF-κB was regulated through the Notch1 signaling pathway.

The development of HCC is a multifactor, multistep,

complex process (26,27). Numerous reports have shown that

hepatocarcinogenesis is associated with the HBx protein. Our

previous research confirmed that HBx induced the malignant

transformation cells of the human non-tumor hepatic cell line L02

(24). Moreover, HBx regulated a

variety of cellular signaling pathways, including the Notch and

NF-κB pathways, thereby contributing to the progression of HCC

(28). In our previous study we

also found that activated Notch signaling is required for HBx to

promote the proliferation and survival of human hepatic cells

(4). However, little is known

about how HBx influences the Notch and NF-κB signaling pathways.

Therefore, in the present study we continued to investigate the

mechanisms by which HBx directly regulates Notch1 and NF-κB and how

Notch1 affects the NF-κB signaling pathway.

The possibility of crosstalk between the HBx and

Notch signaling pathways has become an important focus of research.

One recent report showed that the protein and mRNA expressions of

Notch1 and JAG1 were upregulated in HBx-stably transfected L02

cells (4), which was also

consistent with the report of Gao et al(29). But the underlying molecular

mechanisms are still unknown. The present research revealed a

direct association between HBx and the Notch signaling pathway and

showed that NICD interacts with HBx in HBx-transformed L02 cells,

while the ligand JAG1 did not co-precipitate with HBx. Here we

could deduce that the malignant function of HBx is directly

associated with the activity ofNotch1 signaling pathway, since HBx

could immediately regulate the Notch1 signaling pathway and the key

factor is NICD instead of other components of the Notch1 signaling

pathway. Our study thus provides some novel clues to the mechanism

by which HBx affects the Notch signaling pathway.

NF-κB is involved in the biological processes of

cancers as an important modulator of genes that promote cell

survival, proliferation, migration, inflammation, angiogenesis and

metastasis (30), including the

malignant transformation of hepatocytes (31). NF-κB (p50/p65) is a ubiquitous,

constitutive and inducible heterodimer and the DNA binding activity

of NF-κB traditionally refers to the p50/p65 (p50/RelA)

heterodimer-mediated binding to DNA (25). IκBα interacts with and sequesters

NF-κB in the cytosol (32). It can

also export NF-κB from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (19) and directly inhibits the DNA-binding

activity of NF-κB. Thus p50, p65 and IκBα play crucial roles in the

NF-κB pathway. Recent studies have reported that HBx stimulates the

phosphorylation of IκBα via the IκB kinase complex (28), thereby upregulating the activity of

the NF-κB signaling pathway (29).

In the present study our objective was to discover the mechanisms

of HBx-induced activation of the NF-κB pathway. We found that HBx

could not co-precipitate with the subunits p65 or p50 and the

suppressor IκBα of NF-κB, suggesting that HBx does not activate

NF-κB signaling by directly binding to p65, p50, or IκBα. Reports

have described the regulation of NF-κB by Notch, the mechanisms of

which are dependent on cell type. Notch1 upregulates the expression

of the NF-κB subunits p50, p65, RelB and c-Rel in murine bone

marrow hematopoietic precursors and therefore it can be concluded

that Notch1 upregulates NF-κB activity (13). In satellite liver cells, Notch1

reversed the repression of IκBα expression and lowered NF-κB

activity (33). Since numerous

studies have reported crosstalk between Notch and the NF-κB

pathway, we hypothesize that HBx may promote NF-κB signaling by

activating the Notch pathway. Our studies attempted to reveal the

molecular mechanism of the interaction between Notch1 and NF-κB in

HBx-transformed L02 cells.

Our EMSA results showed that the NF-κB DNA-binding

activity was decreased after Notch signaling was inhibited by DAPT.

To learn more about how Notch1 influence NF-κB in HBx-related HCC,

we used the γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT and Notch1 siRNA to block

Notch signaling. We found that when Notch signaling was inhibited

in HBx-transformed L02 cells, p50 and p65 mRNA levels were

significantly decreased, while IκBα mRNA level was notably

increased. This suggests that Notch activates the NF-κB pathway at

the transcription level. At the same time, in the nucleus the

proteins p50 and p65 were decreased, although their levels had not

changed in the cytoplasm. The results imply that NICD stimulated

the expression of the functional subunits and the nuclear transport

of NF-κB dimers and inhibited the suppressor of NF-κB to active the

NF-κB pathway. To our knowledge, several mechanisms potentially may

explain the effect of Notch1 on NF-κB activity. These include

transcriptional effects, physical binding between NF-κB and Notch1

and indirect effects on IκBα/β phosphorylation (13). There have been studies reported

that Notch1 signaling promoted NF-κB translocation to the nucleus

and DNA binding by increasing both phosphorylation of the IκBα/β

complex and the expression of some NF-κB family members (34). However, the details on the

molecular mechanism still required further confirmation, including

in vivo experiments and in different kinds of HBx-expressing

hepatic cells.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that

HBx could promote Notch signaling by binding to NICD, which then

activates the NF-κB pathway. Therefore, crosstalk between the NF-κB

and Notch1 pathways is partially responsible for the progression of

HBx-induced HCC. However, further investigations are needed to

delineate the exact mechanisms by which Notch1 effects IκBα/β

phosphorylation and promotes NF-κB translocation into the

nucleus.

Abbreviations:

|

ACTB

|

β-actin

|

|

ADAM

|

a disintegrin and metalloproteinase

domain

|

|

BCL

|

B-cell CLL/lymphoma

|

|

coIP

|

co-immunoprecipitation

|

|

CSL

|

CBF1/RBP-Jκ/suppressor of

hairless/LAG1

|

|

DAPI

|

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

|

|

DAPT

|

N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-1-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl

ester

|

|

DLL

|

δ-like protein

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

EMSA

|

electrophoretic mobility shift

assay

|

|

FITC

|

fluorescein isothiocyanate

|

|

HBV

|

hepatitis B virus

|

|

HBx

|

hepatitis B virus X protein

|

|

HCC

|

hepatocellular carcinoma

|

|

IκB

|

nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide

gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor

|

|

JAG

|

jagged

|

|

MMLV

|

Moloney murine leukemia virus

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κB

|

|

NICD

|

Notch receptor’s intracellular

domain

|

|

qRT-PCR

|

quantitative real-time reverse

transcription PCR

|

|

RHD

|

Rel homology domain

|

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the

National Science Foundation of China, nos. 81172063 and

30971352.

References

|

1.

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Melissa M, et al: Global

Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 55:74–108. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Hashem BE and Rudolph KL: Hepatocellular

carcinoma epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis.

Gastroenterology. 132:2557–2576. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Feitelson MA and Duan LX: Hepatitis B

virus X antigen in the pathogenesis of chronic infections and the

development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Pathol.

150:1141–1157. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Wang F, Zhou H, Xia X, et al: Activated

Notch signaling is required for hepatitis B virus X protein to

promote proliferation and survival of human hepatic cells. Cancer

Lett. 298:64–73. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Lai EC: Notch signaling: control of cell

communication and cell fate. Development. 131:965–973. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Miele L: Notch signaling. Clin Cancer Res.

12:1074–1079. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Miele L, Golde T and Osborne B: Notch

signaling in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 6:905–918. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Kopan R and Ilagan MX: Gamma-secretase:

proteasome of the membrane? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 5:499–504. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Berman JN and Look AT: Targeting

transcription factors in acute leukemia in children. Curr Drug

Targets. 8:727–737. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Rangarajan A, Talora C, Okuyama R, et al:

Notch signaling is a direct determinant of keratinocyte growth

arrest and entry into differentiation. EMBO J. 20:3427–3436. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Ronchini C and Capobianco AJ: Induction of

cyclin D1 transcription and CDK2 activity by Notch(ic): implication

for cell cycle disruption in transformation by Notch(ic). Mol Cell

Biol. 1:5925–5934. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Baonza A and Freeman M: Control of cell

proliferation in the Drosophila eye by Notch signaling. Dev Cell.

8:529–539. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Cheng P, Zlobin A, Volgina V, et al:

Notch-1 regulates NF-kappaB activity in hemopoietic progenitor

cells. J Immunol. 167:4458–4467. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Klinakis A, Szabolcs M, Politi K, et al:

Myc is a Notch1 transcriptional target and a requisite for

Notch1-induced mammary tumorigenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 103:9262–9267. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Diao J, Garces R and Richardson CD: X

protein of hepatitis B virus modulates cytokine and growth factor

related signal transduction pathways during the course of viral

infections and hepatocarcinogenesis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.

12:189–205. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16.

|

Seto E, Mitchell PJ and Yen TS:

Transactivation by the hepatitis B virus X protein depends on AP-2

and other transcription factors. Nature. 344:72–74. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Lucito R and Schneider RJ: Hepatitis B

virus X protein activates transcription factor NF-kappa B without a

requirement for protein kinase C. J Virol. 66:983–991.

1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Meyer M, Caselmann WH, Schluter V, et al:

Hepatitis B virus transactivator MHBst: activation of NF-kappa B,

selective inhibition by antioxidants and integral membrane

localization. EMBO J. 11:2991–3001. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Campbell KJ and Perkins ND: Regulation of

NF-kappaB function. Biochem Soc Symp. 73:165–180. 2006.

|

|

20.

|

Perkins ND: Integrating cell-signalling

pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

8:49–62. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Maniati E, Bossard M, Cook N, et al:

Crosstalk between the canonical NF-κB and Notch signaling pathways

inhibits PPARγ expression and promotes pancreatic cancer

progression in mice. J Clin Invest. 121:4685–4699. 2011.

|

|

22.

|

Pan H, Zhou W, He W, et al: Genistein

inhibits MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cell growth by

inhibiting NF-κB activity via the Notch-1 pathway. Int J Mol Med.

30:337–343. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Schwarzer R, Dörken B and Jundt F: Notch

is an essential upstream regulator of NF-κB and is relevant for

survival of Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells. Leukemia. 26:806–813.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Cheng B, Zheng Y, Guo XR, et al: Hepatitis

B viral X protein alters the biological features and expressions of

DNA repair enzymes in LO2 cells. Liver Int. 30:319–326. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Wang Z, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, et al:

Activated K-ras and INK4a/Arf deficiency cooperate during the

development of pancreatic cancer by activation of Notch and NF-κB

signaling pathways. PLoS One. 6:e205372011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Berasain C, Castillo J, Perugorria MJ, et

al: Infammation and liver cancer: new molecular links. Ann NY Acad

Sci. 1155:206–221. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Lupberger J and Hildt E: Hepatitis B

virus-induced concogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 13:74–81. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Qiao L, Zhang H, Yu J, et al: Constitutive

activation of NF-kappaB in human hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence

of a cytoprotective role. Hum Gene Ther. 17:280–290. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Gao J, Chen C, Hong L, et al: Expression

of Jagged1 and its association with hepatitis B virus X protein in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 356:341–347.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Karin M: NF-kappaB and cancer: mechanisms

and targets. Mol Carcinog. 45:355–361. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Luedde T and Schwabe RF: NF-κB in the

liver - linking injury, fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat

Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 8:108–118. 2011.

|

|

32.

|

Beg AA and Baldwin JR: The I kappa B

proteins: multifunctional regulators of Rel/NF-kappa B

transcription factors. Genes Dev. 7:2064–2070. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Oakley F, Mann J, Ruddell RG, et al: Basal

expression of IkappaBalpha is controlled by the mammalian

transcriptional repressor RBP-J (CBF1) and its activator Notch1. J

Biol Chem. 278:24359–24370. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Monsalve E, Ruiz-García A, Baladrón V, et

al: Notch1 upregulates LPS-induced macrophage activation by

increasing NF-kappaB activity. Eur J Immunol. 39:2556–2570. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|