Introduction

Prospective randomized clinical trials have shown

that tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) gefitinib (1–3) and

erlotinib (4,5) as initial treatment for EGFR

mutation-positive advanced NSCLC improved outcomes compared with

chemotherapy. These molecules have thus been approved in many

countries worldwide. Therefore, routine analysis of pathological

specimens is mandatory in clinical practice to predict patient

response. The potential result is an increased likelihood that

patients will receive optimal therapy for their tumour and be

spared a course of therapy with no or significantly less benefit.

For that promise to be realized, a robust process, from patient

sampling to screening methods, has to be developed to be capable of

fast, reliable, sensitive and reproducible detection of the

mutations in patient tumor samples.

In current clinical practice, the samples available

for detection of somatic mutations are most of the time

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues of various tumor sites.

The samples are usually composed of mutant and wild-type DNA from

tumor cells and wild-type DNA from non-malignant cells (normal

epithelial cells, hematopoietic cells and stromal cells such as

fibroblasts). Therefore there is a need for a sensitive technique

and a complete reliable process. If standard dideoxy sequencing has

been the ‘gold standard’ for detecting mutations in constitutive

genetics, this robust method is however time-consuming, has only

moderate sensitivity and might suffer from a lack of robustness

when working on fragmented DNA extracted from formalin fixed

paraffin embedded tumors (6,7).

These limitations of direct sequencing for detecting somatic

mutations has led to the development of more sensitive, less

expensive, and faster methods. A number of alternative procedures

have therefore been developed to detect common cancer mutations,

such as HRM (8–10), allele-specific amplification

(11,12), primer extension (13), and pyrosequencing (14). In most cases, a better sensitivity

was obtained using targeted techniques as compared to direct

sequencing (15,16); reviewed in Ellison et al

(17).

We developed assays aiming at accurately detecting

EGFR mutations in patient tumor samples in routine screening. The

assays had to detect exon 19 deletions and the p.L858R (exon 21)

mutations, the two most common mutations in NSCLC that are clearly

associated with a clinical benefit. These assays, fragment analysis

(exon 19) and allele specific PCR (L858R) have been routinely used

for the last 3 years in our laboratory. Moreover, during this

period, we collected information on the patients (age, gender) and

the samples tested: histology, thyroid transcription factor-1

(TTF-1) expression, primary or metastatic lesion, type of specimen,

and tumor cell content. We undertook the analysis of the data

obtained. This allowed us to evaluate the impact of these

parameters on the frequency and spectrum of EGFR mutations in

Caucasian NSCLC patients. Here we report our experience testing for

EGFR mutations in a large number of samples using sensitive

techniques in a clinical setting.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 1,403 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

tumor samples from NSCLC patients were referred to our laboratory

for EGFR typing between January 2010 and June 2012. There were

1,243 adenocarcinomas, 49 squamous cell carcinomas and 111

non-small cell carcinomas, from 827 men and 576 women.

Sample processing and DNA extraction

Serial sections were cut from each paraffin block.

Tumor-rich areas were marked by the pathologist on a hematoxylin

and eosin 3 μm-thick stained section. To eliminate

non-malignant, stromal and contaminating inflammatory cells and to

enrich the analyzed specimen with tumor cells, these areas were

manually macro-dissected on 10 μm-thick sections using

single-use sterilized scalpels. DNA was then extracted after

paraffin removal (toluene 5 min, ethanol 3 min, ethanol 2 min)

using the Forensic kit and an iPrep system according to the

manufacturer’s recommendations (Invitrogen, Life Technologies SAS,

Villebon sur Yvette, France). DNA concentration was quantified by

spectro-photometry (NanoDrop ND-100 instrument, Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Waltham, MA) and normalized to 5 ng/μl.

Detection of the L858R mutation - allele

specific amplification

For codon 858 mutation, we designed two forward

primers with variations in their 3′ nucleotides such that each was

specific for the wild-type (858L; TCAAGATCACAGATTT TGGGCT) or the

mutated variant (858R; TCAAGATCACAG ATTTTGGGCG), and one common

reverse primer (AS; CATC CTCCCCTGCATGTGTTAAAC). The

sequence-specific forward and the reverse primer were then combined

in ‘Primer mix L’ (primers 858L and AS), and ‘Primer mix R’

(primers 858R and AS). The amplification conditions were optimized

for the RotorGene 3000 instrument (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France).

PCR amplifications were performed using the LC480 SYBR-Green mix

(Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). The reaction mixture contained

10 μl of the supplied 2X master mix, 0.5 μl of each

primer (10 μM each), and 9 μl of the template (45 ng

genomic DNA). The cycling conditions were as follows: denaturation

for 10 min at 95°C; amplification for 45 cycles, with denaturation

for 10 sec at 95°C, annealing for 15 sec at 65°C, and extension for

20 sec at 72°C. The specific 172-bp PCR products were amplified,

and the cycle threshold (Ct)-value was determined for a fixed

normalized fluorescence of 0.05. For each sample, the Ct-value was

determined for the 858L (control) PCR, and for the 858R (mutation

specific) PCR, and the difference was calculated (ΔCt, Fig. 1A). The lower the amount of mutated

DNA in the sample, the higher the ΔCt value. Samples with ΔCt<5

were considered as positive for the p.L858R mutation. Fig. 1A illustrates the assay performed on

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded extracted DNAs containing a

p.L858R mutation (#3532, ΔCt=1.0) or wild-type for this allele

(#3533, ΔCt=12.6).

Detection of exon 19 deletions - fragment

size analysis

PCR were performed as described above using primers

19S (GTCT TCCTTCTCTCTCTGTCATAG) and 19AS (CCACACAGCA

AAGCAGAAACTCAC). Following amplification, amplicons were analyzed

by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on 5-20% acrylamide gels

(Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France). Migration was

performed for 1 h at 100 V. The wild-type EGFR gene yielded a

147-bp amplicon. Deletions were identified as faster migrating

bands. Fig. 1B illustrates the

profiles obtained for exon 19 wild-type tumor (#3221, #3223 and

#3224) and a tumor presenting an exon 19 deletion (#3222). In case

of exon 19 deletions, a doublet (or in rare cases a single band)

was seen at higher molecular weight. We have previously described

that each deletion is characterized by specific additional bands

corresponding to heteroduplexes (18).

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test, the Fisher’s exact test and

the two-tailed non-parametric Mann-Whitney test were used to assess

the association between mutation status of EGFR and each of the

clinicopathological parameters. A p-value of 0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

Assay performance

The sensitivity and specificity of our assay were

evaluated for the specified EGFR alteration in quality control

schemes.

First, serial dilutions of DNA extracted from cell

lines harboring a p.L858R mutation (NCI-H1975: p.L858R;

c.2573T>G) or an exon 19 deletion (NCI-H1650: p.E746- A750del;

c.2235-2249del) in wild-type DNA were analyzed. This revealed that

our techniques allowed us to detect an EGFR alteration when it is

present in at least 1% (p.L858R mutation) or 2% of cells (exon 19

deletions). However, DNA extracted from FFPE samples is of much

lower quality than DNA extracted from cell lines. Therefore, in

order to avoid false negative results, we considered that a minimum

of 10% of tumor cells should be present in the sample. If no

alteration was found in a sample presenting less than 10% of tumor

cells, we concluded that the test was not contributive.

To assess the specificity of our assays, we repeated

the analysis of a large number of samples using an approved kit

(Therascreen EGFR RGQ kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We tested 160

samples that did not present a mutation on exon 19 and 21, and 98

samples presenting an exon 19 deletion or the L858R point mutation.

Identical results were obtained for all these samples.

Finally, our laboratory has been involved in

external quality schemes organized in western France in 2010 and

2011. Twenty NSCLC samples were tested during this period and we

found concordant results with the 5 other centers in all these

cases. More recently we have also been involved in the first

external quality control scheme organized by the French National

Cancer Institute. Sections from 10 NSCLC specimens were sent to all

the laboratories performing EGFR testing in France. We obtained the

expected result for all these samples using our procedures.

In routine practice, FFPE sections were sent from

the department of pathology to the department of molecular biology

every wednesday, and the reports were sent to the oncologists the

next friday. The molecular biology laboratory turnaround time is

thus of 48 h.

Frequency and spectrum of EGFR

mutations

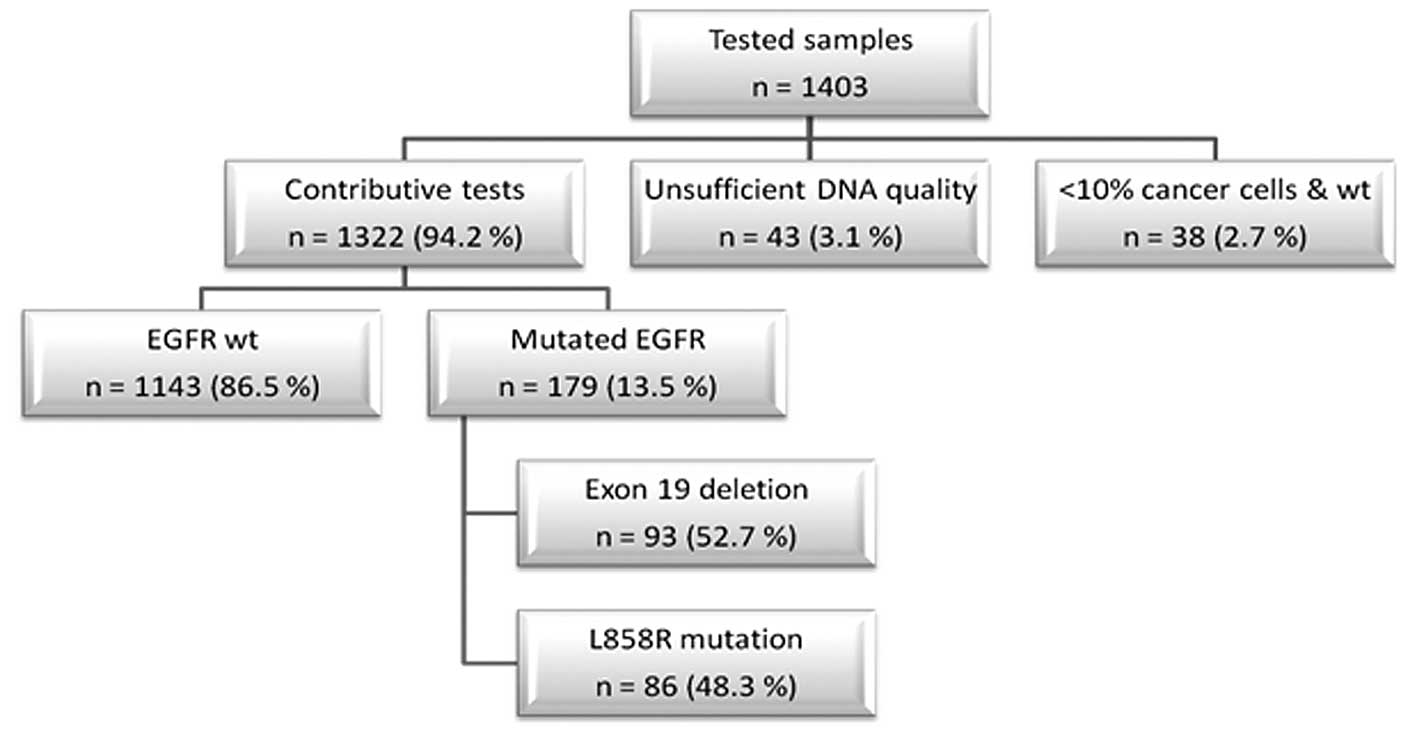

Our study population was composed of 1,403 NSCLC

patients (417 females and 725 males; median age 64). The tests

failed in 43 cases (3.1%), because of insufficient DNA quality

(Fig. 2). In 38 cases (2.7%) where

we were unable to detect an EGFR alteration, the content of tumor

cells in the sample was considered too low to conclude. The

remaining 1,322 tests performed (94.2%) were contributive. We were

able to identify an EGFR alteration in 179 patients (13.5%). These

included 93 exon 19 deletions (52.7% of the detected alterations),

and 86 L858R point mutations (48.3%) (Fig. 2).

The clinicopathologic features of patients with

EGFR- mutated or wild-type tumors in our cohort are summa rized in

Table I. Consistent with previous

observations, the mutation rate was significantly higher in women

than in men (23.0 vs 6.9%), and mutations were more frequent in

adenocarcinomas (168/1,144; 14.6%) than in other histological

types. Interestingly, EGFR-mutated patients were significantly

older than those with wild-type EGFR (median age 71 vs 63 years;

p<10−4).

| Table I.Clinical and pathological

characteristics associated with EGFR mutational status in 1,322

french patients with lung tumors. |

Table I.

Clinical and pathological

characteristics associated with EGFR mutational status in 1,322

french patients with lung tumors.

| Total | EGFR wt | EGFR mutated | P-value |

|---|

| Gender | | | | |

| Female | 543 | 418 (77.0%) | 125 (23.0%) | |

| Male | 779 | 725 (93.1%) | 54 (6.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Age, years | | | | |

| Median | | 63 | 71 | <0.0001 |

| Range | | 28–100 | 32–92 | |

| Histology | | | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 1,144 | 976 | 168 (14.7%) | |

| NSCLC-NOS | 101 | 97 | 4 (4.0%) | 0.004 |

| Squamous

cell | 45 | 42 | 3 (6.7%) | |

Recent data reported by Sun et al (19) showed a correlation between TTF-1

expression and EGFR mutation status. Thus we also analyzed TTF-1

expression in our series of patients. Our data also clearly

indicated that EGFR mutations are more likely to occur in TTF-1

positive tumors (145/675; 17.7%) than in TTF-1 negative

adenocarcinomas (3/218; 1.4%). Almost all (145/148; 98.0%) mutated

adenocarcinomas were TTF-1 positive (Table II).

| Table II.Relationship between TTF-1

immunostaining and EGFR mutation frequency in adenocarcinomas. |

Table II.

Relationship between TTF-1

immunostaining and EGFR mutation frequency in adenocarcinomas.

| Total | EGFR wt | EGFR mutated | P-value |

|---|

| TTF-1 | | | | |

|

IHC+ | 820 | 675 (82.3%) | 145 (17.7%) | |

|

IHC− | 218 | 215 (98.6%) | 3 (1.4%) | <0.0001 |

We next addressed the influence of tumor site and

type of sampling (Table III). The

frequency of EGFR alteration was found to be slightly higher in

metastases than in primary tumors (16.2 vs 13.5%, respectively),

but it was not statistically different (p=0.27). Considering

primary tumors, we did not see a significant difference between

surgical specimen (35/294; 11.9%), bronchial biopsies (42/339;

12.4%) and transthoracic needle biopsies (37/258; 14.3%). When

considering metastases, we also observed similar mutation rate when

analyzing biopsies (23/183; 12.6%), surgical resection (20/135;

14.8%), and transbronchial needle aspirates (5/38; 13.2%). The

mutation rate seemed to be higher in pleural effusions (11/44;

25.0%), but it was not statistically significant.

| Table III.Influence of tumor site and type of

sample on the EGFR mutation frequency. |

Table III.

Influence of tumor site and type of

sample on the EGFR mutation frequency.

| Total | EGFR wt | EGFR mutated |

|---|

|

Finally, we analyzed our data according to the

percentage of cancer cells present in the samples tested. Similar

mutation rates were obtained, even with samples containing less

than 10% of cancer cells (Table

IV).

| Table IV.Influence of the cellularity of

tested samples on the EGFR mutation frequency. |

Table IV.

Influence of the cellularity of

tested samples on the EGFR mutation frequency.

| Total | EGFR wt | EGFR mutated | |

|---|

| Tumor cell

content | | | | |

| >50% | 669 | 590 (88.2%) | 79 (11.8%) | |

| 25–50% | 477 | 407 (85.3%) | 70 (14.7%) | p=0.46, NS |

| 10–25% | 156 | 138 (85.5%) | 18 (11.5%) | |

| <10% | 45 | NC (84.4%)a | 7 (15.6%) | |

Discussion

EGFR is a target of the TKIs gefitinib and

erlotinib, which have been approved for advanced NSCLC treatment in

many countries. Various EGFR testing approaches have been used in

the different phase III trials that led to these approvals. The

Scorpion Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS) was used

in the phase III Iressa Pan-Asia Study (IPASS) to determine

EGFR mutation status (1). A

variety of methods, including direct sequencing, PCR-invader,

PNA-LNA PCR clamp, fragment analysis, and cycleave PCR, were used

in the WJTOG3405 phase III study to select EGFR

mutation-positive patients (2),

and the PNA-LNA PCR clamp method was used in the NEJ002 study

(3). In the European EURTAC study,

tissue samples were analyzed with Sanger sequencing (exons 19 and

21), and EGFR mutations were confirmed with an independent

technique (deletions in exon 19 by length analysis and L858R

mutations in exon 21 were detected with a 5′ nuclease PCR assay)

(5). Finally, in the Optimal

trial, testing was done by PCR-based direct sequencing, and other

methods were applied for monitoring at the same time (gel

electrophoresis for EGFR exon 19 deletions and cycleave

real-time PCR for EGFR exon 21 L858R mutations) (4).

Several years ago, we developed a sensitive

procedure for routine analysis of NSCLC tumors, and the aim of our

study was to evaluate its performance through analysis of the

results obtained during a long period. Between January 2010 and

June 2012, we tested 1,403 tumors in a routine clinical setting.

The tests failed in only 3.1% of the samples tested because of

insufficient quality of DNA. These not contributive tests were not

associated with the type or the size of the samples tested. But

this rate was significantly higher in samples processed in 2 of the

pathology centers that sent samples to our platform (not shown). We

are at present trying to identify the cause(s) of the lower quality

of DNA in some tissues processed in these centers. When excluding

these centers from the analysis, the failure rate decreased down to

1% (12/1,194 samples).

We found that 179 of the tumors tested harbored an

exon 19 deletion or an L858R point mutation. This corresponded to

13.5% of the 1,322 contributive samples. These findings are in

keeping with previous reports on Caucasian patients. For instance,

molecular testing of 755 patients from UK revealed a mutation

prevalence of 13% (20), and 13.1%

of Portuguese patients were found to present an EGFR mutation

(21). A large analysis of Spanish

patients revealed a slightly higher mutation rate (16.6%), but the

authors hypothesized that the participating centers included more

samples from women and patients who had never smoked (22).

In 2004, several groups correlated responses to

gefitinib or erlotinib with the presence of somatic mutations

clustered around the ATP-binding pocket of the tyrosine kinase

domain (23,24). Subsequent reports indicated that

the somatic mutational status of EGFR correlated with female sex

(25,26), smoking history (25,27,28),

adenocarcinoma histology (26,29)

and Asian origin (26).

We were not able to collect the smoking history of

the patients tested during this period in our platform, but the

mutation rate was clearly associated with female sex and

adenocarcinoma histology. Moreover, patients with a mutation were

clearly older than wild-type patients, as previously described for

patients from Japan (30) and

Korea (31). In addition, we

clearly demonstrated that the overwhelming majority of EGFR mutated

tumors expressed the TTF-1 antigen.

In a recent report, Girard et al collected

clinical and pathological data on a large number of patients with

NSCLC who had their tumors genotyped for EGFR mutations at

different institutions. Variables of interest (smoking history,

histological subtype, sex, stage of disease and age) were

integrated in a multivariate logistic regression model, and they

could thus build a model-based nomogram to allow for prediction of

the presence of EGFR mutations in NSCLC (32). Unfortunately, TTF-1 expression data

were lacking, and they could not include this covariate in the

final model.

In our series, the EGFR mutation prevalence was

clearly higher for women with a TTF-1 positive adenocarcinoma

(28.3%; 101/357). The mutation prevalence increased to 46.7%

(64/137) when selecting women older than 70.

Our analysis of this large series of patients

indicated that the mutation rate was not significantly different

between primary tumors and metastases. More importantly, we

demonstrated that there is no impact of the type of specimen tested

on the mutation prevalence. Similar levels of contributive results

(not shown) and of EGFR mutation rates were obtained using

different type of samples, including pleural fluids and

trans-bronchial needle aspirates.

Finally, we also found, using a sensitive approach,

that the mutation rate was not dependent on the sample cellularity.

Indeed, 23 patients for whom the tested samples contained less than

25% of cancer cells (<10 and 10–25%) presented an EGFR mutation

(23/170; 13.5%). Using a less sensitive technique such as direct

sequencing, we would have most likely missed these mutations.

Consequently, these patients would have been treated by

chemotherapy, and not benefited from TKI. That is the reason why,

in routine diagnosis, we do not reject samples containing less than

10% tumor cells. In a recent report Warth et al described an

algorithm for Sanger sequencing-based EGFR mutation analyses

(33). They demonstrated that

sequencing generated 80% reliable analysis of biopsy specimens, but

that in 20% of cases rebiopsy had to be recommended. A more

sensitive technique such as the one we use on a routine practice

avoids performing additional biopsies.

The clinical impact of detecting mutations present

in a low percentage of tumor cells has been assessed by Zhou et

al (34). They determined

whether abundance of EGFR mutations in tumors predicts

benefit from treatment with EGFR-TKIs for advanced NSCLC. They

detected EGFR mutations in lung cancer samples using both direct

DNA sequencing and the sensitive ARMS technique. Mutation-positive

tumors by both methods carried high abundance of EGFR mutations,

and tumors that were mutation positive by ARMS but mutation

negative by direct DNA sequencing harbored low abundance of EGFR

mutations. Median progression free survival of patients with low

abundance of EGFR mutations was significantly longer than for those

with wild-type tumors, and the difference between patients with

high and low abundance of EGFR mutations was not significant

regarding overall response rate and overall survival. Thus, it is

worth using a sensitive technique to detect patients with a low

abundance of mutations.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that performing EGFR

testing in routine diagnostic and clinical practice using sensitive

approaches can be successful. In our French population, the EGFR

mutation prevalence is higher in older patients, women,

adenocarcinomas and TTF-1 expressing adenocarcinomas.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all

the people involved in the different steps of the process from

tissue processing (technicians and secretaries from the Department

of Pathology) to molecular analysis (Réjane Lapied and Séverine

Huet), and all the Pathologists that provided tumors for EGFR

testing. The Departments of Biochemistry and Pathology are labelled

and funded by the French National Cancer Institute (INCa) to

perform EGFR testing of lung cancer patients.

References

|

1.

|

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al:

Gefitinib or carboplatinpaclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 361:947–957. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al:

Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal

growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): an open label, randomised phase

3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 11:121–128. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al:

Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with

mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 362:2380–2388. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Zhou C, Wu Y-L, Chen G, et al: Erlotinib

versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with

advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer

(OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase

3 study. Lancet Oncol. 12:735–742. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al:

Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for

European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive

non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label,

randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 13:239–246. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Querings S, Altmuller J, Ansen S, et al:

Benchmarking of mutation diagnostics in clinical lung cancer

specimens. PLoS One. 6:e196012011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Marchetti A, Felicioni L and Buttitta F:

Assessing EGFR mutations. N Engl J Med. 354:526–528. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Takano T, Ohe Y, Tsuta K, et al: Epidermal

growth factor receptor mutation detection using high-resolution

melting analysis predicts outcomes in patients with advanced non

small cell lung cancer treated with gefitinib. Clin Cancer Res.

13:5385–5390. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9.

|

Do H, Krypuy M, Mitchell P, Fox S and

Dobrovic A: High resolution melting analysis for rapid and

sensitive EGFR and KRAS mutation detection in formalin fixed

paraffin embedded biopsies. BMC Cancer. 8:1422008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Fukui T, Ohe Y, Tsuta K, et al:

Prospective study of the accuracy of EGFR mutational analysis by

high-resolution melting analysis in small samples obtained from

patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

14:4751–4757. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Didelot A, Le Corre D, Luscan A, et al:

Competitive allele specific TaqMan PCR for KRAS, BRAF and EGFR

mutation detection in clinical formalin fixed paraffin embedded

samples. Exp Mol Pathol. 92:275–280. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Kimura H, Kasahara K, Kawaishi M, et al:

Detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in serum as

a predictor of the response to gefitinib in patients with

non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 12:3915–3921. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Lin CH, Yeh KT, Chang YS, Hsu N and Chang

JG: Rapid detection of epidermal growth factor receptor mutations

with multiplex PCR and primer extension in lung cancer. J Biomed

Sci. 17:372010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Dufort S, Richard M-J, Lantuejoul S and de

Fraipont F: Pyrosequencing, a method approved to detect the two

major EGFR mutations for anti EGFR therapy in NSCLC. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 30:572011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Ellison G, Donald E, McWalter G, et al: A

comparison of ARMS and DNA sequencing for mutation analysis in

clinical biopsy samples. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 29:132–139. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Goto K, Satouchi M, Ishii G, et al: An

evaluation study of EGFR mutation tests utilized for non-small-cell

lung cancer in the diagnostic setting. Ann Oncol. 23:2914–2919.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Ellison G, Zhu G, Moulis A, Dearden S,

Speake G and McCormack R: EGFR mutation testing in lung cancer: a

review of available methods and their use for analysis of tumour

tissue and cytology samples. J Clin Pathol. 66:79–89. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Denis MG, Theoleyre S, Chaplais C, et al:

Efficient detection of EGFR alterations in lung adenocarcinomas.

ASCO Meeting abstracts. 28:105562010.

|

|

19.

|

Sun P-L, Seol H, Lee HJ, et al: High

incidence of EGFR mutations in Korean men smokers with no

intratumoral heterogeneity of lung adenocarcinomas: correlation

with histologic subtypes, EGFR/TTF-1 expressions, and clinical

features. J Thorac Oncol. 7:323–330. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Leary AF, Castro DGd, Nicholson AG, et al:

Establishing an EGFR mutation screening service for non-small cell

lung cancer - sample quality criteria and candidate histological

predictors. Eur J Cancer. 48:61–67. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21.

|

Castro AS, Parente B, Goncalves I, et al:

Epidermal growth factor recetor mutation study for 5 years, in a

population of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Rev Port

Pneumol. 19:7–12. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Rosell R, Moran T, Queralt C, et al:

Screening for epidermal growth factor receptor mutations in lung

cancer. N Engl J Med. 361:958–967. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al:

Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor

underlying responsiveness of non small-cell lung cancer to

gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 350:2129–2139. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Paez JG, Janne PA, Lee JC, et al: EGFR

mutations in lung cancer: correlation with clinical response to

gefitinib therapy. Science. 304:1497–1500. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Matsuo K, Ito H, Yatabe Y, et al: Risk

factors differ for non-small-cell lung cancers with and without

EGFR mutation: assessment of smoking and sex by a case-control

study in Japanese. Cancer Sci. 98:96–101. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Shigematsu H, Lin L, Takahashi T, et al:

Clinical and biological features associated with epidermal growth

factor receptor gene mutations in lung cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst.

97:339–346. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Kosaka T, Yatabe Y, Endoh H, Kuwano H,

Takahashi T and Mitsudomi T: Mutations of the epidermal growth

factor receptor gene in lung cancer: biological and clinical

implications. Cancer Res. 64:8919–8923. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28.

|

Yatabe Y, Kosaka T, Takahashi T and

Mitsudomi T: EGFR mutation is specific for terminal respiratory

unit type adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 29:633–639. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Yatabe Y and Mitsudomi T: Epidermal growth

factor receptor mutations in lung cancers. Pathol Int. 57:233–244.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Ueno T, Toyooka S, Suda K, et al: Impact

of age on epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in lung cancer.

Lung Cancer. 78:207–211. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Choi YH, Lee JK, Kang HJ, et al:

Association between age at diagnosis and the presence of EGFR

mutations in female patients with resected non-small cell lung

cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 5:1949–1952. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Girard N, Sima CS, Jackman DM, et al:

Nomogram to predict the presence of EGFR activating mutation in

lung adenocarcinoma. Eur Respir J. 39:366–372. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Warth A, Penzel R, Brandt R, et al:

Optimized algorithm for Sanger sequencing-based EGFR mutation

analyses in NSCLC biopsies. Virchows Arch. 460:407–414. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Zhou Q, Zhang X-C, Chen Z-H, et al:

Relative abundance of EGFR mutations predicts benefit from

Gefitinib treatment for advanced non small-cell lung cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 29:3316–3321. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|