Introduction

African-American men have a two-fold risk of

mortality from prostate cancer, and currently one of the most

unsettled debates is whether this high risk is driven by behavior,

biology or both (1,2). Pathological features, such as larger

prostate sizes, greater tumor volumes and tumor grades of African

Americans, in contrast to Caucasians strongly implicate biological

differences for this disparity (3–5). In

contrast, the disparity in incidence of the disease between second

generation Asian migrants and their prostate cancer-free pedigrees

strongly implicate environmental or behavioral/lifestyle variables

as risk factors in the etiology or prognosis of the disease

(6). Adoption of a Western

lifestyle characterized by less physical activity, increased intake

of red meat and dairy products high in saturated fats and

cholesterol has been associated with increased risk and poor

prognosis of the disease (6–8).

Regardless, epidemiological and population studies reveal that

lifestyle or environmental factors alone seldom account for the

disparity in cancer risk among different populations (9). Current evidence rather suggests that,

the interaction of specific genetic and lifestyle factors

predispose populations to most cancers (10–12).

The suggestion that some diets increase the burden

of prostate cancer has encouraged the increased scrutiny of

cholesterol-rich, Western-style diets as risk factors for the

disease. Overwhelming evidence suggests that all direct human

ancestors were largely herbivorous, and that the shift to meat or

cholesterol-rich diets in our immediate human ancestors selected

for genes that modulate the extra cholesterol burden (13). One meat-adaptive gene that

critically mediates cholesterol and lipid uptake by cells

throughout the body is apolipoprotein (Apo) E (13,14).

ApoE displays genetic polymorphism with three common alleles

namely, ε2, ε3, and ε4 in a single gene-locus in chromosome 19,

giving rise to 3 homo-zygous (apoε2/ε2, apoε3/ε3, apoε4/ε4) and 3

heterozygous genotypes (Apoε2/ε3, Apoε2/ε4, Apoε3/ε4) (15). Variants of this gene account for

more genetic differences in cholesterol metabolism than any other

gene (16,17). Apoε3 genotype is reportedly

selected for its positive effects in cholesterol control and for

reducing the risk of various diseases (13). Yet again for cholesterol control,

the ε2 and ε4 alleles are regarded as dysfunctional forms of the ε3

alleles (18), and are considered

to enhance the susceptibility to certain cancers (19). The ApoE3 gene is the most prevalent

in all human populations, and is considered to have evolved from

ancestral ApoE 4-like gene (13).

Based on the different binding affinities of apoE4 and apoE2 to the

LDL receptor and the LDL-related protein receptor, rates of

postprandial clearance of remnant lipoproteins are reportedly low

in subjects with the ApoE2/E2 phenotype, and high in those with the

apoE4/E4 phenotype (20). Overall,

carriers of the ε2 allele have lower serum LDL-cholesterol

concentrations relative to carriers of the ε3 and ε4 alleles

(21).

The ApoE gene also regulates reverse cholesterol

transport by transporting the excess cholesterol in peripheral

tissues (including the prostate) to the liver for excretion

(22). Efficient cellular

cholesterol efflux depends on ATP-binding cassette transporters

(ABCA1 and ABCG1), and uses poor ApoAI and ApoE-containing

particles (γ-LpE) from ApoE3/E3 subjects as avid cholesterol

acceptors (22). In some cells,

the transcription of ApoE is induced by exposure to cholesterol,

and its release into the extracellular medium is by classical

secretory pathway (23). There is

evidence that secreted ApoE also removes cholesterol in an

ABCA1-independent manner (24).

This pathway requires the intracellular synthesis and transport of

ApoE through internal membranes before its secretion (24). Regardless of the pathway used for

cholesterol efflux, theApoE isoforms differ in their ability to

deliver cholesterol to cells, and in their ability to mediate

cholesterol efflux (25,26). This is consistent with the

plausible differences in isoform-specific build-up in intracellular

cholesterol. Nascent cellular cholesterol first appears in rafts or

caveolae domains of plasma membranes, where it forms a complex with

caveolin-1 (cav-1), a cholesterol-binding protein (27,28).

The caveolae provide scaffolds for the aggregation of signaling

molecules that increase biological activities for cell survival,

and cell proliferation (29). Also

stored cholesterol is vital for mammalian cell growth, as growth

requires cholesterol for membrane biogenesis (28). Since cav-1 is a growth signaling

molecule, it may serve as a surrogate for cell proliferation, which

is the major feature of prostate tumor progression. The aim of this

study is to explore whether prostate cancer cells with apoE2/E4

phenotypes accumulate higher prostatic tissue cholesterol, and

whether cholesterol storage in such cell lines is associated with

aggressive cell phenotypes.

Materials and methods

Materials

Human prostatic adenocarcinoma cells LNCaP, PC3,

DU145 and MDA PCa 2b were obtained from American Type Culture

Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Cell culture media, MEM and

RPMI-1640 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA),

while HPC1 serum free medium and FNC coating mix were obtained from

Athena Enzyme Systems (Baltimore, MD, USA). Sigma-Aldrich supplied

all the cell culture supplements, adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic

monophosphate (cAMP), acyl-CoA cholesterol acyltransferase (ACAT)

inhibitor (Sandoz 58-035), cholic acid, enhanced avian reverse HS

RT-PCR kit, and (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin.

BODIPY-cholesterol was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.

(Alabaster, AL, USA), while Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY,

USA) supplied fetal bovine serum (FBS). Human ApoAI was purchased

from BioVision Inc. (Milpitas, CA, USA). Gene ruler ultra-low range

DNA ladder and Fast digest HhaI restriction enzyme kit was

supplied by Fermentas Inc. (Glen Burnie, MD, USA), while Novex TBE

running buffer, Hi-density sample buffer and polyacrylamide 8% TBE

gels were supplied by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). QIAmp DNA

mini kit and RNeasy kit were supplied by Qiagen (Valencia, CA,

USA).

Cell cultures

LNCaP cells were grown in RPMI-1640 medium

supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% L-glutamine, 0.5 ml fungizone, 5 ml

100 mM sodium pyruvate, 1% penicillin-streptomycin and buffered

with 0.75% HEPES. PC3 and DU145 cells were cultured in MEM with 10%

FBS 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% glutamine, 1% non-essential

amino acids, 0.1% gentamicin and fungizone, and buffered with 0.75%

HEPES. MDA PCa 2b cells were grown in HPC1 medium in FNC-precoated

6-well plates. The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5%

CO2.

Amplification of ApoE sequences from

genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was extracted as described in QIAMP DNA

Mini and blood Mini handbook (Qiagen) from confluent prostate

cancer cells. ApoE sequences were amplified from 0.5 μg of

genomic DNA using Jump Start AccuTaq DNA polymerase

(Sigma-Aldrich), and oligonucleotide primers F4

(5′-ACAGAATTCGCCCCGGCCTGGTACAC-3′) and F6

(5′-TAAGGTTGGCACGGCTGTCCAAGGA-3′) in a Master cycler (Eppendorf) as

previously described (30). The

ApoE sequences were amplified using the enhanced avian reverse

transcriptase-PCR kit procedure (Sigma-Aldrich). The reaction was

carried out in a reaction mixture volume of 50 μl. Reaction

conditions were: 1 cycle of 95°C for 5 min. This was followed by 30

cycles of heating (denaturation) at 95°C for 1 min and annealing at

60°C for 1 min. Extension was at 70°C for 2 min, and final

extension was at 70°C for 2 min. To confirm the amplification of

the ApoE sequences, the PCR products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose

gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining methods using the

Gel Imaging Kodak MI standard Logic. The concentration of PCR

products was then measured using NanoDrop 1000 spectrophotometer

(Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

Restriction isotyping of amplified ApoE

sequences with HhaI and gel analysis

After PCR amplification 3 μl of FastDigest

HhaI enzyme (Fermentas) was added directly to each reaction

mixture comprised of 30 μl of PCR amplification product, 51

μl of nuclease free water and 6 μl of 10X FastDigest

green buffer. The reaction mixtures were mixed gently and incubated

at 37°C in a water bath for 5 min, and then loaded onto 8%

non-denaturing pre-cast Novex polyacrylamide TBE gels (1.5-mm thick

and 8-cm long) and electrophoresed with 5X Novex TBE running buffer

for 20 min. The gel was run in an XCell SureLock Mini-Cell

electrophoresis tank at 200 constant voltage and stopped when the

bromophenol tracking dye was approximately two inches from the

bottom of the tank to enable visibility of the 20- and 25-bp bands.

After electrophoresis, the gel was treated with ethidium bromide (6

μl of 30%) for 10 min, washed three times in distilled water

and visualized by UV using the Gel Imaging Kodak MI standard Logic.

The sizes of the HhaI fragments were estimated by comparison

with Ultra low range DNA gene ruler (Fermentas Inc.).

Cav-1 gene expression analysis by

RT-PCR

After seeding all the prostate cancer cell lines to

confluence as described above, they were washed with PBS,

trypsinized and harvested on ice. RNA was extracted from them

according to the procedure described in the RNeasy isolation kit

(Qiagen). From each sample, 0.25 μg of total RNA was

subjected to first-strand cDNA synthesis using the enhanced avian

reverse transcriptase-PCR kit procedure (Sigma-Aldrich). The same

amount of each cDNA was used to amplify fragments of cav-1 and

GAPDH genes in the presence of Taq DNA polymerase (Sigma-Aldrich).

Specific primers for PCR amplification of the two genes were: i)

cav-1: sense 5′-CAACAAGGCCATGGCA GACGAGCT-3′ and antisense

5′-CATGGTACAACTGCC CAGATG-3′; (b) GAPDH: sense 5′-AGGTCGGAGTCAACG

GATTG-3′ and antisense 5′-GTGATGGCATGGACTGT GGT-3′. Cycling

conditions were: one initial denaturation cycle of 95°C for 5 min.

This was followed by 38 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 2 min

(for cav-1) or 1 min (for GAPDH), and annealing at 55°C for 2 min

(for cav-1) or 57°C for 1 min (for GAPDH). Extension was at 72°C

for 2 min and final extension was for 1 cycle at 72°C for 5 min.

The amplified products were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel and

visualized by ethidium bromide staining method. The intensity of

the bands was quantified with the Gel Imaging Kodak MI standard

Logic. All the reactions were normalized with GAPDH mRNA

expression.

Treatment of cells with

BODIPY-cholesterol

After growing the cells to confluence in their

respective media, they were washed with phosphate buffered saline

(PBS), and labeled with a complex mixture of 2 μg/ml ACAT

inhibitor, unlabeled cholesterol, BODIPY-cholesterol and

2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2HβCD), prepared as previously

described (31). All the cells

were incubated in 1 ml of the labeling medium for 1 h, and then

washed with their respective HEPES-buffered growth media. The cells

were then equilibrated with these growth media containing 0.2% BSA,

ACAT inhibitor, and cAMP (0.3 mmol/l) for 18 h. After the

equilibration period, the cells were washed with the HEPES-buffered

media and triplicates of the experimental groups were incubated for

12 h in the media having cholesterol acceptors (10 μg/ml of

ApoA-I), while the control group received no such treatment.

Analysis of efflux and intracellular

BODIPY-cholesterol

At the end of the incubation period, the efflux

media in the control and cholesterol acceptor groups were removed,

filtered through a 0.45-μm filter, and the fluorescence

intensity measured with Infinite M200 microplate reader (Tecan) at

482-nm excitation and 515-nm emission. To analyze the intracellular

concentration of BODIPY-cholesterol, all the cells in the control

and cholesterol acceptor groups were solubilized with 1% cholic

acid and thoroughly mixed by shaking on a plate shaker for 4 h at

room temperature. The fluorescence was again measured as

described.

Microscopy and image analysis

After labeling the cells with BODIPY-cholesterol

mixture and subsequent equilibration in the respective growth

media, the cells were washed with PBS and treated with cholesterol

acceptors as described above. They were then split into two groups;

one group was incubated for 12 h in cholesterol acceptors (ApoAI),

and the second group had no acceptors. In both groups, the labeled

BODIPY-cholesterol was visualized within the living cells using an

IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with a polychrome IV

monochromator (TILL Photonics) with appropriate filters. BODIPY

fluorescence intensity in the plasma membrane was then analyzed

with Image-Pro Plus software (Cybernetics).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Minitab 16

(Minitab Inc., University Park, PA, USA) and SigmaPlot 10.0 (Systat

Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Data are presented as the means

± SD, n=3. Differences between the groups were analyzed by a

one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and by Tukey’s post-hoc

test.

Results

ApoE genotypes of the prostate cancer

cell lines

In this study, the unique restriction fragments from

the Apoε2 genotypes were detected as the 91- and 83-bp bands, while

the fragments for the Apoε3 genotypes aligned with the 91-, 48- and

35-bp bands of the DNA marker. The restriction fragments of the

Apoε4 genotypes were identified by their 48- and 35-bp fragments as

well as their unique 72-bp fragment. The intensities of the

overlapping 35/38-bp bands were lower for all the Apoε2/ε4

restriction fragments because of the absence of the 35 bp fragment

in all Apoε2 genotypes. Fig. 1

shows the polyacrylamide gel separation of ApoE isoforms from

genomic DNA of prostate cancer cells, after the DNA amplification

by PCR, and digestion with the restriction enzyme HhaI. The

digested fragments revealed the presence of homozygous and

heterozygous combinations of Apoε alleles. From the HhaI

cleavage signature fragments, the LNCaP cell line carried

homozygous Apoε3/ε3 alleles, while PC3 and DU145 were both

heterozygous for the Apoε2/ε4 alleles. Another heterozygous allele

combination (Apoε3/ε4) was found in MDA PCa 2b cell line.

Relative expression of cav-1 gene in

aggressive and non-aggressive prostate cancer cell lines

Endogenous ApoE colocalizes with cav-1 at the plasma

membrane to maintain lipid flux (32), thus we investigated the relative

expression of cav-1 mRNA in the prostate cancer cell lines in order

to validate its relationship with variants of ApoE gene and

cholesterol balance. Our results showed a relationship between

specific ApoE isoforms and the level of expression of cav-1 mRNA in

prostate cancer cell lines. According to the agarose gel

electrophoresis separation image shown in Fig. 2a, cav-1 mRNA expressed markedly in

the aggressive cell lines (PC3 and DU145). By contrast, cav-1 mRNA

was undetectable in the non-aggressive cell lines (LNCaP and MDA

PCa 2a). Semi-quantitative evaluation of cav-1 expression by RT-PCR

showed almost a two-fold increase in cav-1 expression in the

aggressive cell lines as compared to the non-aggressive cell lines

(Fig. 2b). The difference between

cav-1 gene expression in the aggressive (PC3 and DU145) and

non-aggressive (LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b) cell lines was statistically

significant (p<0.05).

Analysis of intracellular

BODIPY-cholesterol efflux

Examination of the relationship between ApoE

phenotypes and its cholesterol regulatory mechanism revealed a

significantly (p<0.001) greater efflux of BODIPY-cholesterol

from the non-aggressive cell lines compared to the aggressive cell

lines (Fig. 3a). The statistical

summary of the reverse cholesterol transport process showed a

significant difference (p<0.001) in cholesterol efflux across

all cell lines. Specifically, interval plots illustrating the

differences in cholesterol efflux between aggressive and

non-aggressive prostate cancer cell lines assessed with Tukey’s

test (Fig. 3b) revealed a

significantly higher cholesterol efflux in the non-aggressive

prostate cancer cell lines (LNCap, 56.32±3.33% and MDA PCa 2b,

63.49±2.28%) than from the aggressive cell lines (PC-3, 45.29±2.40%

and DU-145, 40.46±4.49%). It has been established that cells

incubated in the presence of cholesterol acceptors such as ApoA-I

release more cholesterol to the medium than those incubated without

the acceptors. This is consistent with our data showing a

statistically significant (p<0.05) difference between the mean

values of cholesterol efflux from cells cultured in the presence

and absence of cholesterol acceptors. There was no interaction

(p>0.17) between prostate cancer cell lines and the presence or

absence of cholesterol acceptors.

Analysis of retained

BODIPY-cholesterol

Consistent with the expected relationship between

apoE phenotypes and intra-cellular cholesterol regulation, we

observed a significantly higher (p<0.001) retention of

cholesterol by the aggressive cell lines, compared to the

non-aggressive cell lines (Fig.

3c) Likewise, the difference between cholesterol retention in

the presence and absence of efflux acceptors in some of the cell

lines was statistically significant (p<0.001).

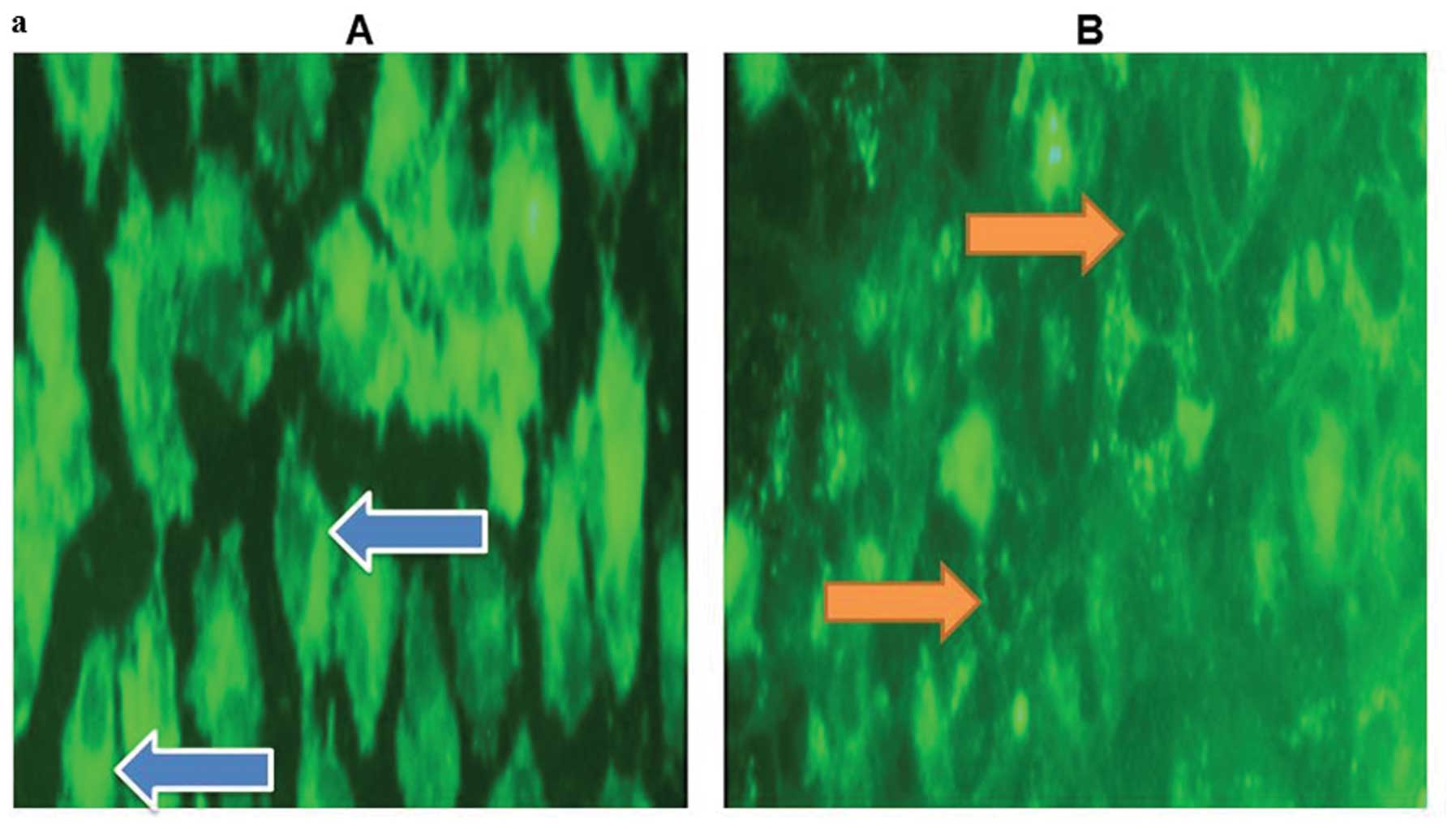

Microscopic analysis of membrane

localized BODIPY-cholesterol

To probe the actual localization of the retained

BODIPY-cholesterol using fluorescence microscopy, we observed

higher membrane localization in of BODIPY-cholesterol in cell

cultures lacking cholesterol acceptors (Fig. 4a). Finally, the fluorescence

microscopy images showed a higher localization of

BODIPY-cholesterol in membranes of aggressive prostate cancer cell

lines, than those of non-aggressive ones (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

In this study, we explored the association between

ApoE phenotypes of prostate cancer cell lines and the risk of

aggressive prostate cancer. We investigated PC3 and DU145, the two

established androgen-insensitive cell lines that are highly

invasive and tumorigenic in athymic nude mice, and uniquely express

PROS1, a crucial protein mediator of cancer progression, thus

justifying their consistently undisputed characterization as

hallmarks of aggressiveness (33,34).

In contrast, LNCaP and MDA PCa 2b, which are androgen

receptor-expressing, androgen-refractory, poorly migratory and less

invasive cell lines that universally characterize

non-aggressiveness were also investigated (33,35–39).

Accordingly, we classified tumor aggressiveness by regarding the

highly tumorigenic and the moderately tumorigenic prostate cancer

cell lines (PC3 and DU145, respectively) as ‘aggressive’; while the

weakly tumorigenic cell lines (LNCaP and MDAPCa 2b) (33) were regarded as ‘non-aggressive’. We

observed that the aggressive cell lines were heterozygous for the

Apoε2/ε4 genotype, while the non-aggressive cell lines were

heterozygous carriers of at least one Apoε3 genotype. The

complementary alleles of the non-aggressive cell lines were Apoε3

(PC3) and Apoε4 (MDAPCa 2b). Thus, PC3 was homozygous for the

ApoE3/E3 phenotype, while MDAPCa 2b was heterozygous for the

ApoE3/E4 phenotype.

To the best of our knowledge, the genetic

polymorphism of ApoE in prostate cancer cell lines has not been

previously documented. Rather, an earlier investigation focused on

the linear relationship between the expression of ApoE mRNA and the

aggressiveness of prostate cancer cell lines (40). Remarkably, a number of previous

investigations had investigated the relationship between genetic

polymorphism of ApoE and susceptibility to breast (41) and prostate tumors (42). While these studies were generally

focused on the transcriptional regulation of tumor aggressiveness

by ApoE, the present study exclusively investigated the

relationship between ApoE variants and acknowledged aggressive

prostate cancer cell lines. Accordingly, we observed that the

aggressive prostate cancer cell lines carried the ApoE2/E4

phenotype, while the non-aggressive types carried the ApoE3/E3 or

E3/ E4 phenotypes. Although there is scarcely any data on the

allelic variation of prostate cancer cell lines, an earlier study

in human subjects revealed overexpressed Apoε2/ε4 alleles in

hormone-refractory, locally recurrent prostate cancer patients as

compared to control subjects (43). The observed carriage of the

Apoε2/ε4 alleles in these patients and our demonstration of its

frequency in aggressive prostate cancer cell lines highlight its

probable role in aggressive disease, since hormone-refractory and

recurrent prostate carcinomas are regarded as clinically aggressive

(44).

Currently, there are no clearly defined mechanisms

to explain the relationship between the ApoE isoforms, especially

the ApoE2/E4 phenotype and aggressive prostate cancer. However, a

possible link could be inferred from our observed accumulation of

intracellular cholesterol in cells carrying certain ApoE

phenotypes. A preponderance of evidence suggests that intracellular

cholesterol overload supports the progression of prostate cancer to

advanced disease (45). In this

context, the role of ApoE in clearing circulating cholesterol is

the regulation of its influx to cells (18), and its efflux by reverse

cholesterol transport, involving its extraction from peripheral

tissues to the liver for excretion (46). Phenotypic differences in the

regulation of cholesterol efflux from cells by ApoE (46,47),

may govern cholesterol accumulation in macrophages and RAW 264.7

cell lines (47,48). Although we are not aware of such a

relationship in prostate cancer cell lines, the concept is

consistent with our findings that the three ApoE phenotypes in our

prostate cancer cell lines have distinct abilities to promote

cholesterol efflux, and to inversely accumulate cholesterol.

The Apoε3 allele-carrying non-aggressive cell lines,

or precisely the LNCaP which carries the ApoE3/E3 phenotype, and

the MDA PCa 2b, which carries the ApoE3/E4 phenotype displayed

higher BODIPY-cholesterol efflux, while the aggressive cell lines

carrying the ApoE2/E4 phenotype (PC3 and DU145) displayed lower

BODIPY-cholesterol efflux. There was no significant difference in

the BODIPY-cholesterol efflux of the poorly aggressive cell lines,

and neither was there any difference in that of the aggressive cell

lines. To support the isoform-mediated differences in cellular

cholesterollevels, an assessment of BODIPY-cholesterol accumulation

by fluorescence microscopy revealed that the non-aggressive

prostate cancer cell lines, which carry at least one Apoε3 allele

retained less membrane cholesterol, in contrast to the Apoε3

allele-deficient aggressive cell lines. These data appear

consistent with the high expression of key effectors of cholesterol

production and downregulation of the expression of major

cholesterol exporters in prostate cancer cells, thus supporting the

reprogramming of their cholesterol metabolism to favor its

increased production and rapid cell growth (48). Our data revealed a higher

BODIPY-cholesterol within membranes of the aggressive prostate

cancer cell lines, which carry the ApoE2/E4 phenotype, while a

lower amount was found in membranes of the non-aggressive prostate

cancer cell lines, which carry at least one Apoε3 allele.

Taken together, these exploratory findings support

the premise that in prostate cancer cell lines, efficient

cholesterol efflux and its resultant depletion is associated with

certain ApoE isoforms. To the contrary, our data imply that other

ApoE isoforms are associated with deregulated cholesterol efflux,

and membrane accumulation. Consistent with this, our results

suggest that aggressive prostate cancer cell lines, carrying the

ApoE2/E4 phenotype, exhibited low BODIPY-cholesterol efflux and

accumulated BODIPY-cholesterol in the membranes.

To our knowledge there is paucity of data on how the

different ApoE isoforms influence cholesterol efflux in prostate

cancer cell lines. Nevertheless, studies from human intact

fibroblasts showed that lipoprotein-containing ApoE particles

(γ-LpE) from ApoE3/E3 individuals stimulated 7- to 13-fold more

cholesterol efflux than from ApoE2/E2 or ApoE4/E4 individuals

(46). Earlier studies using RAW

264.7 mouse macrophage cells did not find any difference in

cholesterol efflux from cells with the three ApoE isoforms

(49). However, all the clonal

macrophage cell lines used in that study carried three different

homozygous ApoE-isoforms, whereas our investigated prostate cancer

cell lines had a combination of heterozygous and homozygous ApoE

isoforms. Again, the differences in the ApoE isoform-dependent

cholesterol efflux in RAW 264.7 cells may have been annulled by the

presence in the culture of a cAMP analogue, which induces a

cellular ApoE receptor-mediated transfer of cholesterol to all

apolipoproteins, followed by the subsequent release of the

lipoprotein particles (49).

ApoE influences cholesterol efflux from cells by

reverse cholesterol transport, and rids cells of excess

cholesterol, which is transported to the liver for excretion. To

influence this cholesterol efflux, ApoE is generally synthesized in

various cell types including the prostate, and then transported to

the plasma membrane for secretion (23). In cholesterol-rich cells, this

secreted ApoE promotes cholesterol efflux even in the absence of

cholesterol acceptors (23). The

exact mechanism by which ApoE mediates cellular cholesterol efflux

and whether this cholesterol efflux is isoform-specific is still

unknown. The most consistent explanation for ApoE-mediated

cholesterol efflux had relied on the intracellular association of

ApoE with cAMP-induced ABCA1, which induces increased secretion of

ApoE and catalysis of an initial transfer of cholesterol to the

lipid poor ApoE (16). Doubt has

been cast on the sole regulation of cholesterol efflux by ABCA1,

leading to the recognition of ABCG1 as finalizing the full transfer

of this cholesterol to the apolipoprotein (16). One reason cited for the

plausibility of the ApoE isoform-dependent cholesterol efflux was

the low affinity of the apoE2 isoform versus the ApoE3 or ApoE4

isoforms for heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), which modulate

cholesterol depleting ability of ApoE (50). The higher cholesterol efflux of

ApoE2-carrying cells was explained by several demonstrations that

the higher affinity of ApoE3 and ApoE4 for HSPGs caused the

sequestration of the latter isoforms into the pericellular

proteoglycan matrix, leading to their eventual cellular degradation

(47,50). Thus, ApoE2 is the most effective

for cholesterol efflux, followed by ApoE3, while ApoE4 is least

effective. The effective cholesterol efflux of the ApoE2/E2

phenotype-carrying cells is consistent with an earlier observation

that cholesterol loaded cells redirect this ApoE isoform from the

degradatory to the secretory pathway (47). This study also revealed that cells

carrying the ApoE3/E3 phenotype secreted nearly 77% of ApoE

proteins, leading to reduced intracellular cholesterol accumulation

(47). These investigations

concluded that ApoE4/ E4-carrying cells secreted the most ApoE

apolipoproteins, but lacked effective net cholesterol efflux

because of greater HSPGs affinity and re-uptake of cholesterol

particles (47,50).

Our observed reduction in cholesterol efflux and

increased cholesterol retention by the ApoE2/E4 phenotype-carrying

prostate cancer cell lines highlights the dominance of the ε4

allele over the ε2 allele in heterozygosity. Elucidating how the ε4

allele dominates the ε2 allele in cholesterol transport will

significantly improve our understanding of the isoform-dependent

regulation of cholesterol efflux and retention. The preceding

discussion is consistent with previous evidence showing that

reduced cholesterol efflux by ApoE contributes to membrane

cholesterol accumulation (51).

The current paradigm in cholesterol homeostasis holds that the

increased prevalence of lipid rafts and caveolae in cells is

attributable to membrane cholesterol accumulation. Cav-1 is the

most celebrated structural protein of the caveolae that binds

cholesterol, and its absence impairs cholesterol homeostasis

(52). Additionally, membrane

cholesterol enrichment has been associated with increased cav-1

mRNA expression (53). This is

consistent with our studies showing that

BODIPY-cholesterol-accumulating and aggressive prostate cancer cell

lines overexpress cav-1 mRNA, whereas BODIPY-cholesterol poor and

non-aggressive prostate cancer cell lines express low or no cav-1

mRNA.

It has been previously demonstrated that cav-1

expression is highly dependent on the availability of cholesterol

(54), and its depletion

diminishes the caveolae by removing cav-1 from the membrane

(55). We observed a higher

retention of the fluorescent cholesterol analogue in the aggressive

prostate cancer cell lines, which concurrently overexpressed cav-1

mRNA, further strengthening the relationship between cav-1

expression and cell aggression. This relationship supports earlier

demon stration that cav-1 is a potential biomarker of aggressive

prostate cancer (56). To the

contrary, we found no expression of cav-1 mRNA in the

non-aggressive prostate cancer cell lines. This finding is

consistent with previous studies indicating the overexpression of

cav-1 in mouse and human metastatic prostate cancer cells (57). This has been corroborated by a

recent report indicating that the absence of cav-1 significantly

inhibited the progression of prostate cancer to highly invasive and

metastatic disease (58). Overall,

molecular approaches highlight the plausible relationship between

intracellular cholesterol accumulation and prostate cancer.

Pathological studies of prostate tumor samples had provided

evidence for such relationship by demonstrating a positive

correlation between Gleason grade and the levels of expression of

this cholesterol-binding protein or cav-1 (55).

Although the role of caveolae in the progression of

solid tumors is not fully understood, the contribution of cav-1 to

signaling processes that initiate prostate cancer has been

extensively investigated. The initiation and progression of cancer

by cav-1 is linked to its tendency to form platforms that aggregate

membrane proteins for cell proliferation signaling. This function

of cav-1 is partly related to its possession of an amino acid

domain that binds a variety of signaling proteins (49), which recently includes ABCA1 and

ApoE (32,59). Binding of these proteins to cav-1

is believed to inactivate downstream growth signals (59). An interaction between cav-1, ABCA1

and ApoE is appropriate as it suggests crosstalk among them

favoring cholesterol balance, reduced cholesterol overload and

inhibition of cell proliferation. However, the effect of cav-1

expression on cholesterol efflux is still controversial and has

been attributed to differences in the cell types used for such

studies (60). The molecular

mechanism by which these membrane-anchored proteins maintain the

correct intracellular cholesterol balance and the particular ApoE

isoforms that perturb such equilibrium has not been elucidated. Our

results highlight the need for further experiments to confirm

whether the ApoE2/E4 is the dysfunctional phenotype that inhibits

cholesterol efflux, leading to prostate cancer cell

proliferation.

In summary, our data suggest the possibility of the

relationship between the ApoE2/E4 phenotype, the intracellular

cholesterol efflux and cholesterol content of prostate cancer

cells. This is consistent with our observed overexpression of

cav-1, the sentinel gene for cholesterol overload exclusively by

the ApoE2/E4-carrying aggressive prostate cancer cell lines.

We conclude that the overexpression of cav-1 and

cholesterol overload in aggressive prostate cancer cell lines,

suggests that cav-1 may confer survival advantage on prostate

cancer cells leading to disease progression. The less than

anticipated aggressiveness of the African American cancer cell line

(MDA PCa 2b) suggests that the Apoε3 allele masks the deregulated

cholesterol balance associated with the ancestral Apoε4 allele. The

low cholesterol efflux and higher cholesterol retention in ApoE2/E4

phenotype-carrying aggressive prostate cancer cells justifies

further investigation of ApoE2/E4 phenotype as a biomarker of

aggressive disease. While the evidence amassed so far and elsewhere

clearly indicates that genetic factors play a key role in

determining the susceptibility to aggressive prostate cancer, the

sample size in our study imposes limited statistical power and

restrains definitive conclusions. Unraveling the mechanism by which

the dysfunctional apoE isoforms transforms the prostate cancer cell

lines to aggressive phenotypes could be a daunting task, which

however could be overcome by genetic manipulation under varying

physiological conditions, and may provide new insights into the

pathogenesis and therapeutic targets of the disease.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National

Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Prevention and Control Training

Program Grant R25 CA04788 (G.O.I.).

References

|

1.

|

Williams SD, Cook ED, Anderson KB and

Hamilton SJ: Bridging the gap between populations: the challenge of

reducing cancer disparities among African-American and other ethnic

minority populations. US Oncol. 4:72–75. 2008.

|

|

2.

|

Ifere GO, Abebe F and Ananaba GA: Emergent

trends in the reported incidence of prostate cancer in Nigeria.

Clin Epidemiol. 4:19–32. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Sakr WA: Prostatic intraepithelial

neoplasia: A marker for high-risk groups and a potential target for

chemoprevention. Eur Urol. 35:474–478. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Bock CH, Powell I, Kittles RA, Hsing AW

and Carpten J: Racial disparity in prostate cancer incidence,

biochemical recurrence, and mortality. Prostate Cancer. 716178:1–2.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Bigler SA, Pound CR and Zhou X: A

retrospective study on pathological features and racial disparities

in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer. 2011:2394602011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Lee J, Demissie K, Lu SE and Rhoads GG:

Cancer incidence among Korean-American immigrants in the United

States and native Koreans of South Korea. Cancer Control. 14:78–85.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Ma RW and Chapman K: A systematic review

of the effect of diet in prostate cancer prevention and treatment.

J Hum Nutr Diet. 22:187–199. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Michaud DS, Augustsson K, Rimm EB,

Stampfer MJ, Willet WC and Giovanucci E: A prospective study on

intake of animal products and risk of prostate cancer. Cancer

Causes Control. 12:557–567. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Waddell WJ: Epidemiological studies and

effects of environmental estrogens. Int J Toxicol. 17:173–191.

1998. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10.

|

Le Marchand L and Wilkens LR: Design

considerations for genomic association studies: importance of

gene-environment interactions. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev.

17:263–267. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Nothlings U, Yamamoto JF, Wilkens LR,

Murphy SP, Park SY, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN and Le Marchand L:

Meat and heterocyclic amine intake, smoking, NAT1 and NAT2

polymorphisms, and colorectal cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort

study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 18:2097–2106. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Wünsch Filho V and Zago MA: Modern cancer

epidemiology research: genetic polymorphism and environment. Rev

Saude Publica. 39:490–497. 2005.

|

|

13.

|

Finch CE and Stanford CB: Meat-adaptive

genes and the evolution of slower aging in humans. Q Rev Biol.

79:3–50. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Mahley RW: Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol

transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science.

240:622–630. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Antonoglou CO,

Veletza S, Tentes IK, Kortsaris AX, Hatseras DI and Kaski JC:

Apolipoprotein E genotype and circulating interleukin-10 levels in

patients with stable and unstable coronary artery disease. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 48:2471–2481. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Leduc V, Domenger D, De Beaumont L,

Lalonde D, Bélanger-Jasmin S and Poirier J: Function and

comorbidities of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J

Alzheimers Dis. 2011:1–22. 2011.

|

|

17.

|

Eichner JE, Dunn ST, Perveen G, Thompson

DM, Stewart KE and Stroehla BC: Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and

cardiovascular disease: a HuGE review. Am J Epidemiol. 155:487–495.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Mahley RW and Rall SC Jr: Apolipoprotein

E: far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu Rev Genomics Hum

Genet. 1:507–537. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Moore RJ, Chamberlain RM and Khuri FR:

Apolipoprotein E and the risk of breast cancer in African-American

and non-Hispanic white women. A review. Oncology. 66:79–93. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Kallio MJ, Salmenperä L, Siimes MA,

Perheentupa J, Gylling H and Miettinen TA: Apolipoprotein E

phenotype determines serum cholesterol in infants during both

high-cholesterol breast feeding and low-cholesterol formula

feeding. J Lipid Res. 38:759–764. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Berglund L: The APOE gene and diets - food

(and drink) for thought. Am J Clin Nutr. 73:669–670.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Papaioannou I, Simmons JP and Owen JS:

Targeted in situ gene correction of dysfunctional APOE alleles to

produce atheroprotective plasma ApoE3 protein. Cardiol Res Pract.

2012:1487962012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Kockx M, Jessup W and Kritharides L:

Regulation of endogenous apolipoprotein E secretion by macrophages.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 28:1060–1067. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Huang ZH, Fitzgerald ML and Mazzone T:

Distinct cellular loci for the ABCA1-dependent and

ABCA1-independent lipid efflux mediated by endogenous

apolipoprotein E expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

26:157–162. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Huang Y, von Eckardstein A, Wu S and

Assmann G: Effects of the apolipoprotein E polymorphism on uptake

and transfer of cell derived cholesterol in plasma. J Clin Invest.

96:2693–2701. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Lane RM and Farlow MR: Lipid homeostasis

and apolipoprotein E in the development and progression of

Alzheimer’s disease. J Lipid Res. 46:949–968. 2005.

|

|

27.

|

Uittenbogaard A, Ying Y and Smart EJ:

Characterization of a cytosolic heat-shock protein-caveolin

chaperone complex. Involvement in cholesterol trafficking. J Biol

Chem. 273:6525–6532. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Liscum L and Munn NJ: Intracellular

cholesterol transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1438:19–37. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29.

|

Li YC, Park MJ, Ye SK, Kim CW and Kim YN:

Elevated levels of cholesterol-rich lipid rafts in cancer cells are

correlated with apoptosis sensitivity induced by

cholesterol-depleting agents. Am J Pathol. 168:1107–1118. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Hixson JE and Vernier DT: Restriction

isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and

cleavage with Hha I. J Lipid Res. 31:545–548.

1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Sankaranarayanan S, Kellner-Weibel G, de

la Llera-Moya M, Phillips MC, Asztalos BF, Bittmam R and Rothblat

GH: A sensitive assay for ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux using

BODIPY-cholesterol. J Lipid Res. 52:2332–2340. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Yue L and Mazzone T: Endogenous adipocyte

apolipoprotein E is colocalized with caveolin at the adipocyte

plasma membrane. J Lipid Res. 52:489–498. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Nair HK, Rao KV, Aalinkeel R, Mahajan S,

Chawda R and Schwartz SA: Inhibition of prostate cancer cell colony

formation by the flavonoid quercetin correlates with modulation of

specific regulatory genes. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 11:63–69.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Saraon P, Musrap N, Cretu D, Karagiannis

GS, Batruch I, Smith C, Drabovich AP, Trudel D, van der Kwast T,

Morrissey C, Jarvi KA and Diamandis EP: Proteomic profiling of

androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines reveals a role for

protein S during the development of high grade and

castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 287:34019–34031.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35.

|

Wang B, Yang Q, Ceniccola K, Bianco F,

Andrawis R, Jarret T, Frazier H, Patierno SR and Lee NH: Androgen

receptor-target gene in African American prostate cancer

disparities. Prostate Cancer. 2013:7635692013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36.

|

Kim DH and Wirtz D: Recapitulating cancer

cell invasion in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 108:6693–6694.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Hoosein NM: Neuroendocrine and immune

mediators in prostate cancer progression. Front Biosci.

3:D1274–D1279. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

Hara T, Miyazaki H, Lee A, Tran CP and

Reiter RE: Androgen receptor and invasion in prostate cancer.

Cancer Res. 68:1128–1135. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Nomura DK, Lombardi DP, Chang JW, Niessen

S, Ward AM, Long JZ, Hoover HH and Cravatt BF: Monoacylglycerol

lipase exerts dual control over endocannabinoid and fatty acid

pathways to support prostate cancer. Chem Biol. 18:846–856. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Venanzoni MC, Giunta S, Murara GB, Storari

L, Crescini C, Mazzucchelli R, Montironi R and Seth A:

Apolipoprotein E expression in localized prostate cancers. Int J

Oncol. 22:779–786. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Saadat M: Apolipoprotein E (ApoE)

polymorphism and susceptibility to breast cancer: a meta-analysis.

Cancer Res Treat. 44:121–126. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Niemi M, Kervinen K, Kiviniemi H,

Lukkarinen O, Kyllönen AP, Apaja-Sarkkinen M, Savolainen MJ,

Kairaluoma MI and Kesäniemi YA: Apolipoprotein E phenotype,

cholesterol and breast and prostate cancer. J Epidemiol Community

Health. 54:938–939. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43.

|

Haapla K, Lehtimäki T, Ilveskoski E and

Koivisto PA: Apolipoprotein E is not linked to locally recurrent

hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis.

3:107–109. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44.

|

Koivisto P, Visakorpi T, Rantala I and

Isola J: Increased cell proliferation activity and decreased cell

death are associated with the emergence of hormone-refractory

recurrent prostate cancer. J Pathol. 183:51–56. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45.

|

Mostaghel EA, Solomon KR, Pelton K,

Freeman MR and Montgomery RB: Impact of circulating cholesterol

levels on growth and intratumoral androgen concentration of

prostate tumors. PLoS One. 7:e300622012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46.

|

Krimbou L, Denis M, Haidar B, Carrier M,

Marci M and Genest J Jr: Molecular interactions between apoE and

ABCA1: impact on apoE lipidation. J Lipid Res. 45:839–848. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47.

|

Cullen P, Cignarella A, Brennhausen B,

Mohr S, Assmann G and Von Eckardstein A: Phenotype-dependent

differences in apolipoprotein E metabolism and in cholesterol

homeostasis in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Clin Invest.

101:1670–1677. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48.

|

Murtola TJ, Syvälä H, Pennanen P, Bläuer

M, Solakivi T, Ylikomi T and Tammela TL: The importance of LDL and

cholesterol metabolism for prostate epithelial cell growth. PLoS

One. 7:e394452012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Smith JD, Miyata M, Ginsberg M, Grigaux C,

Shmookler E and Plump AS: Cyclic AMP induces apolipoprotein E

binding activity and promotes cholesterol efflux from a macrophage

cell line to apolipoprotein acceptors. J Biol Chem.

271:30647–30655. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50.

|

Hara M, Matsushima T, Satoh H, Iso-o N,

Noto H, Togo M, Kimura S, Hashimoto Y and Tsukamoto K:

Isoform-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages by

apolipoprotein E is modulated by cell surface proteoglycan.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 23:269–274. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51.

|

Karasinska JM and Hayden MR: Cholesterol

metabolism in Huntington disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 7:561–572. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52.

|

Fernández-Hernando C, Yu J, Dávalos A,

Prendergast J and Sessa WC: Endothelial-specific overexpression of

caveolin-1 accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein

E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 177:998–1003. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53.

|

Cohen AW, Hnaska R, Schubert W and Lisanti

MP: Role of caveolae and caveolins in health and disease. Physiol

Rev. 84:1341–1379. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54.

|

Frank PG, Cheung MW, Pavlides S, Llaverias

G, Park DS and Lisanti MP: Caveolin-1 and regulation of cellular

cholesterol homeostasis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

291:H677–H686. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55.

|

Daniel EE, El-Yazbi A and Cho WJ: Caveolae

and calcium handling, a review and a hypothesis. J Cell Mol Med.

10:529–544. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56.

|

Yang G, Truong LD, Wheeler TM and Thompson

TC: Caveolin-1 expression in clinically confined human prostate

cancer: a novel prognostic marker. Cancer Res. 59:5719–5723.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57.

|

Thompson TC: Metastasis-related genes in

prostate cancer: the role of caveolin-1. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

17:439–442. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58.

|

Williams TM, Hassan GS, Li J, Cohen AW,

Medina F, Frank PG, Pestell RG, Di Vizio D, Loda M and Lisanti MP:

Caveolin-1 promotes tumor progression in an autochthonous mouse

model of prostate cancer. J Biol Chem. 280:25134–25145. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59.

|

Lin YC, Ma C, Hsu WC, Lo HF and Yang VC:

Molecular interaction between caveolin-1 and ABCA1 on high-density

lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux in aortic endothelial

cells. Cardiovasc Res. 75:575–583. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60.

|

Le Lay S, Rodriguez M, Jessup W, Rentero

C, Li Q, Cartland S, Grewal T and Gaus K: Caveolin-1-mediated

apolipoprotein A-I membrane binding sites are not required for

cholesterol efflux. PLoS One. 6:e233532011.PubMed/NCBI

|