Introduction

Fucoidan is a polysaccharide from the cell wall of

brown seaweed containing a substantial percentage of L-fucose and

sulfate ester groups (1). It has

numerous pharmacological properties as an anti-coagulant,

anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant agent (2–5). In

particular, its anti-tumor activity has recently attracted

considerable attention (6,7) as a potential therapeutic agent for

cancer. However, the anti-senescence effects and detailed mechanism

of action remains poorly understood in normal hepatic cells.

Treatment options for liver cancer focus primarily

on chemotherapy (8). While these

chemotherapeutic regimens are well established, the major drawback

remains their limited specificity for the tumor site.

Chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cisplatin, induce senescence by

enhancing the activity of the tumor suppressor p16INK4a

in cancer and normal cells, which results in increased toxicity to

normal cells, which require balanced expression of

p16INK4a for growth and differentiation to maintain cell

homeostasis. Thus, cancer cell-specific expression of

p16INK4a would be a valuable therapeutic strategy for

cancer treatment (9).

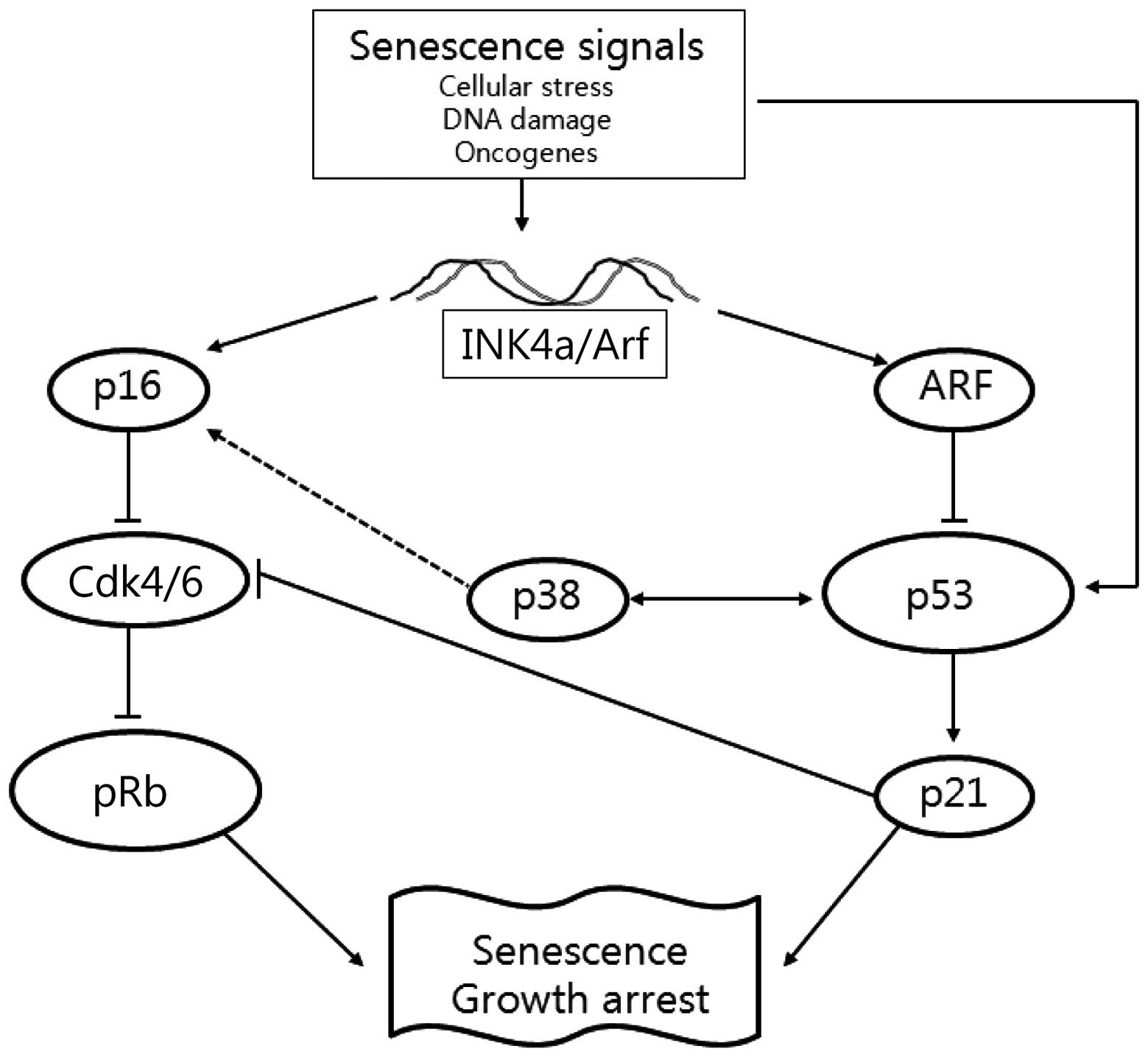

Cellular senescence, leading to cell death through

the prevention of regular cell renewal, is associated with the

upregulation of p16INK4a in most mammalian tissues

(10). This process requires

activation of several signaling pathways, including phosphorylated

retinoblastoma (pRb) and p14Arf-p53 (11). Phosphorylation of the Rb protein

results in increased p16INK4a expression to inhibit

cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk) 4/6. This leads to increased levels

of hypophosphorylated Rb that decrease p16INK4a

expression (12). Although there

is a feedback loop between p16INK4a and Rb,

p16INK4a expression does not change appreciably during

the cell cycle to correlate with the activation status of Rb

(13). However, increased

expression of p16INK4a leads to senescence and cancer

cells inactivate p16INK4a by homozygous deletion or

hypermethylation to overcome its effects. The tumor suppressor

p14Arf (p19Arf in mouse cells) has emerged as

an interesting candidate linking transformation and senescence

responses. Arf is the second protein, in addition to p16, expressed

from the INK4a/Arf locus, but bears no homology to

p16 or any other cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs)

(14). Arf neutralizes the ability

of MDM2 to promote p53 degradation, leading to the stabilization

and accumulation of p53 (15).

Increased expression of Arf also causes growth arrest, one of the

hallmarks of premature senescence (16). Thus, the tumor suppressor proteins

of the INK4a/Arf locus function in distinct

anticancer pathways as p16INK4a directly regulates pRb,

while p14Arf directly regulates p53 and indirectly

regulates pRb (Fig. 1).

Inactivation of the p53 and pRb pathways through a variety of

mechanisms occurs in the majority of, if not all, human cancers.

Although these pathways play important roles in differentiation,

development and DNA repair, the INK4a/Arf locus

responds largely to aberrant growth or oncogenic stress. Therefore,

the INK4a/Arf locus appears to function as a

dual-pronged brake to malignant growth, which engages two potent

anti-proliferative pathways represented by p16INK4a-pRb

and p14Arf-p53 signaling (17).

The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)

pathway regulates cellular processes that directly contribute to

tumor suppression, including oncogene-induced senescence and

replicative senescence (18), as

well as proliferation and tumorigenesis (19). Senescence is also accompanied by

markers associated with replicative exhaustion of normal cells,

such as senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity

and the induction of p21, p16INK4a and/or

p14Arf (16,20). A previous study suggested that

expression of α-2-macroglobulin (α2M) can be used as a

biomarker of aging in cultured human fibroblasts, can be measured

easily by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

with a limited sample, and is a more suitable biomarker candidate

of aging then the well-known senescence-associated genes such as

p16INK4a (21). In this

study, we determined the expression of α2M as a

biomarker of cellular senescence to assess the anti-senescence

effects of fucoidan in normal human liver cells.

Materials and methods

Fucoidan

Commercially available fucoidan purified form F.

vesiculosus (F5631) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St.

Louis, MO, USA).

Cell culture

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line (HepG2;

HB-8065) and the human normal liver cell line (Chang-L; CCL-13)

were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, GA,

USA). Cells were cultured in MEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100

μg/ml) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2

incubator.

Cell viability assay

Cell viability was determined by the

Cyto™ cell viability assay kit (LPS solution, Daejeon,

Korea). Cells were seeded at a density of 1×104

cells/well in a 96-well plate. After 24 h, the cells were treated

with the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) vehicle or 100, 250 and

500 μg/ml fucoidan. The Cyto solution was added to each well

and incubated for 4 h. The formazan product was estimated by

measuring absorbance at 450 nm in a microplate reader (BioTek

Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). The viability of

fucoidan-treated cells was expressed as a percentage of

vehicle-treated control cells considered 100% viable.

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were seeded at a density of 1×104

cells/well and treated with various concentrations of fucoidan for

24 h. Control and treated cells were harvested, washed in cold PBS,

fixed in 70% ethanol and stored at 4°C. The resulting cells were

stained with 200 μl of Muse™ cell cycle reagent

at room temperature for 30 min in the dark before analysis. DNA

content was assessed by Muse™ cell analyzer (EMD

Millipore Co., CA, USA).

Apoptosis analysis

The Muse Annexin V and Dead cell kit (EMD Millipore

Co., MA, USA) was used for the apoptosis assay. HepG2 cells and

Chang-L cells plated at a density of 1×106 cells/well

were treated with varying concentrations of fucoidan for 24 h.

Cells were harvested by trypsinization, washed twice with PBS, and

re-suspended in Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) for 20

min at room temperature in the dark. The cells were evaluated

immediately by Muse cell analyzer. The percentage of apoptotic

cells was assessed using the Muse™ software.

Western blotting

Samples were analyzed by western blotting, as

described previously (20).

Whole-cell lysates were prepared by lysing cell pellets in a NETN

lysis buffer [0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 12

mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 10 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, 1

mM PMSF]. Samples (50 μg) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and

transferred to Immobilion-P transfer membranes (Millipore Co., MA

USA). The primary antibodies used included monoclonal

anti-p16INK4a, polyclonal anti-Cdk4 and -Cdk6,

polyclonal anti-p21, polyclonal anti-p38, monoclonal anti-p-p38,

polyclonal anti-p53 and polyclonal anti-pRb (1:1,000, Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., TX, USA). Membranes were washed and incubated

with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at

1:10,000. Bound secondary antibody was detected using a

chemiluminescence substrate (Advansta, Menlo Park, CA, USA) and

visualized on GeneSys imaging system (SynGene Synoptics, Ltd.,

London, UK).

Real-time PCR

Cells were harvested 24 h after treatment with PBS,

100, 250 or 500 μg/ml fucoidan. Total-RNA was extracted from

HepG2 and Chang-L cells using the QIAzol lysis reagent (Qiagen

Sciences, Inc., Germantown, MD, USA). RNA quality was evaluated by

measuring absorbance at 260 and 280 nm to calculate the

concentration and to assess the purity of RNA, respectively.

Agarose electrophoresis was used to detect RNA purity and

integrity.

The GoScript™ Reverse Transcription

System (Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA) was used to prepare cDNA

according to the manufacturer’s instructions; the samples were

stored at −20°C. The quality of cDNA was assessed by amplifying an

internal reference gene, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

(GAPDH), by PCR and the results were confirmed by 2% agarose gel

electrophoresis. The products were examined by computerized gel

imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Quantitative PCR was conducted in 20 μl

reactions containing QuantiMix SYBR kit (PhilKorea Technology,

Inc., Daejeon, Korea) using the Illumina Eco™ real-time

PCR system (Illumina, Inc., Hayward, CA, USA). The oligonucleotide

primers for p16INK4a, p14Arf, p21, p53, p38,

α2M and GAPDH are shown in Table I. Reaction mixtures were incubated

for an initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min followed by 40

cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, 55°C for 15 sec and 72°C for 15 sec. For

each sample, the expression level of each mRNA was quantified as

the cycle threshold difference (ΔCt) to GAPDH mRNA. All

reactions were performed in triplicate and repeated with two

independent experiments.

| Table I.Primers for real-time PCR. |

Table I.

Primers for real-time PCR.

| Forward | Reverse |

|---|

| GAPDH | TGC ACC ACC AAC TGC

TTA GC | GGC ATG GAC TGT GGT

CAT GAG |

|

p16INK4a | GCC CAA CGC CCC GAA

CTC TTT C | TGA AGC TAT GCC CGT

CGG TCT G |

|

p14Arf | GGA GGC GGC GAG AAC

AT | TGA ACC ACG AAA ACC

CTC ACT |

| p53 | GAG GGA TGT TTG GGA

GAT GTA A | CCC TGG TTA GTA CGG

TGA AGT G |

| p38 | GAG GAT GCC AAG CCA

TG | TCT TAT CTG AGT CCA

ATA CAA GCA TC |

| p21 | CCG CGA CTG TGA TGC

GCT AAT G | CTC GGT GAC AAA GTC

GAA GTT C |

| α2M | TTG TCA GTG ACG TTT

GCC TC | CAA ACT CAT CCG TCT

CGT AG |

Statistical analysis

SPSS software (Chicago, IL, USA) was used to perform

the statistical analysis. For comparisons for more than two groups,

data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA),

followed by Duncan’s test for multiple comparisons. For all tests,

P<0.05 was considered to indicate significance.

Results

Effects of fucoidan on cell

viability

To verify the effects of fucoidan on cell viability,

cells were treated with fucoidan at the concentrations indicated

for 24 h (Fig. 2). Compared to the

untreated controls, Chang-L cells exhibited no cytotoxicity at

concentrations between 0 and 500 μg/ml. In contrast,

proliferation of HepG2 cells was dose-dependently inhibited by

fucoidan treatment (250 μg/ml, 79.75±9.94% inhibition; 500

μg/ml, 62.43±1.0% inhibition). Thus, the ability of fucoidan

to inhibit proliferation was significantly different between HepG2

and Chang-L cells.

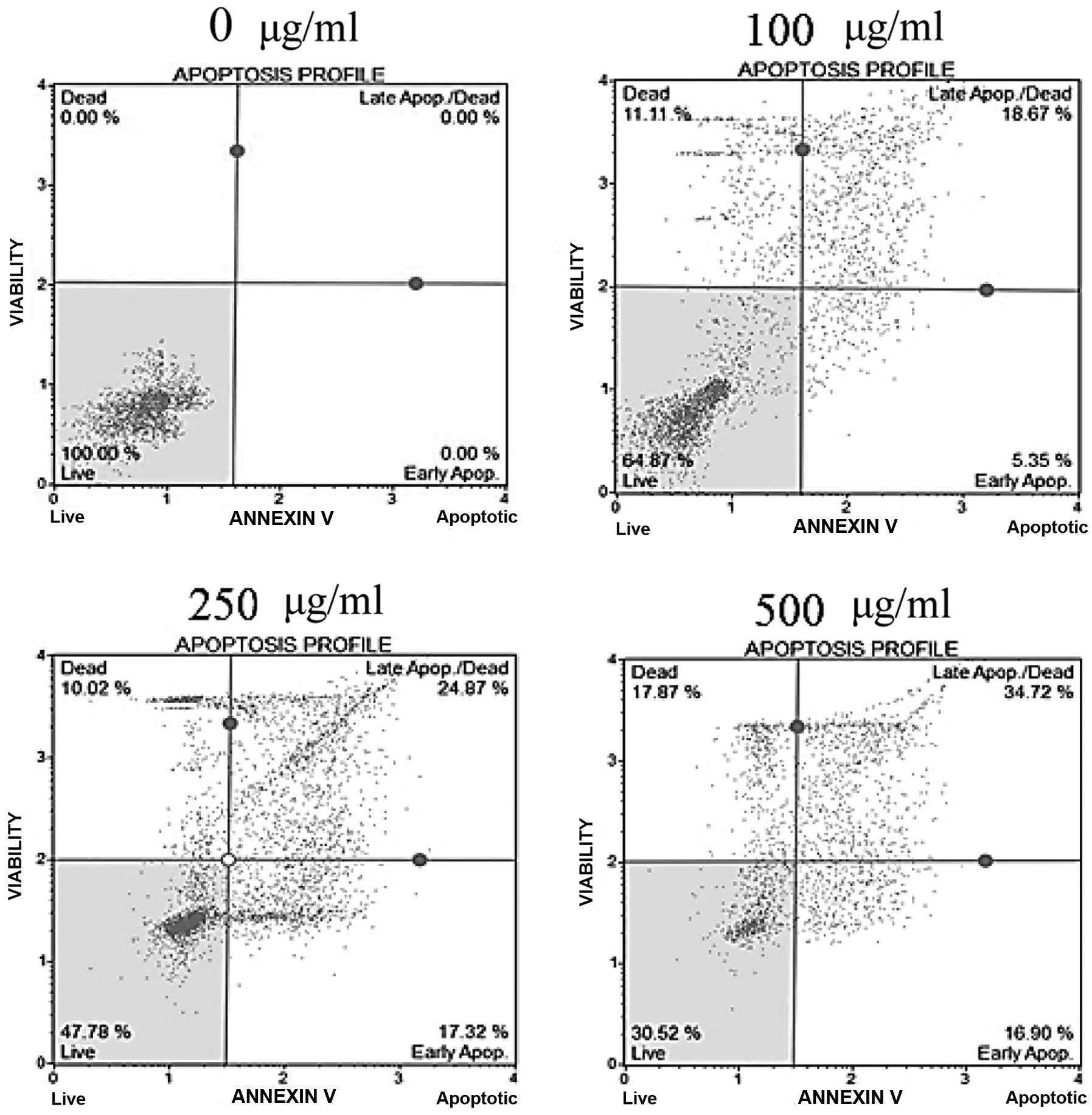

Effects of fucoidan on apoptosis

To determine whether the cytotoxicity of fucoidan

was caused by apoptosis, Annexin V/7-AAD double-staining was

performed. In fucoidan-treated HepG2 cells, the percentage of the

early apoptotic cells, as well as the total percentage of Annexin

V-positive cells indicating late apoptotic cells, was significantly

increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). In Chang-L cells, the percentage

of apoptotic cells did not differ between fucoidan-treated groups

and controls (data not shown). These results indicate that fucoidan

had a strong antitumor effect on hepatocellular carcinoma cells and

is a potent apoptosis-inducing agent.

Effects of fucoidan on the cell

cycle

To determine whether fucoidan affected the cell

cycles of HepG2 and Chang-L cells, we performed cell analysis 24 h

after fucoidan treatment. Treatment with 500 μg/ml fucoidan

led to a significant decrease in the production of S and

G2/M phases and G0/G1 phase arrest

in HepG2 cells (43.12% in W/O, 77.78% in fucoidan-treated samples;

P<0.05). Treatment at concentrations between 0 and 500

μg/ml did not significantly change the cell cycles of

Chang-L cells (Table II). These

results suggest that the anti-proliferative effect of fucoidan on

HepG2 cells can be attributed to a blocking of the

G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.

| Table II.Fractions of each cell cycle phase in

HepG2 and Chang-L cells cultured in the presence of fucoidan for 24

h. |

Table II.

Fractions of each cell cycle phase in

HepG2 and Chang-L cells cultured in the presence of fucoidan for 24

h.

| Fucoidan in

HepG2(μg/ml) |

G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M

(%) |

|

| 0 |

43.12±6.50a |

28.86±4.20a |

23.86±5.91a |

| 100 |

68.52±4.67b |

21.74±5.98a,b |

8.26±5.33b |

| 250 |

71.76±2.37b,c |

17.60±3.03b |

13.90±1.25b |

| 500 |

77.78±2.00c |

8.94±1.38c |

12.20±2.23b |

|

| Fucoidan in

Chang-L(μg/ml) |

G0/G1 (%) | S (%) | G2/M

(%) |

|

| 0 |

44.18±2.12a |

23.68±2.06a |

30.78±2.65a |

| 100 |

45.67±1.05a |

18.67±1.47b |

35.67±1.07b |

| 250 |

43.83±1.60a |

25.63±1.51a |

29.30±2.82a |

| 500 |

45.50±5.24a |

25.63±1.51a |

28.00±5.91a |

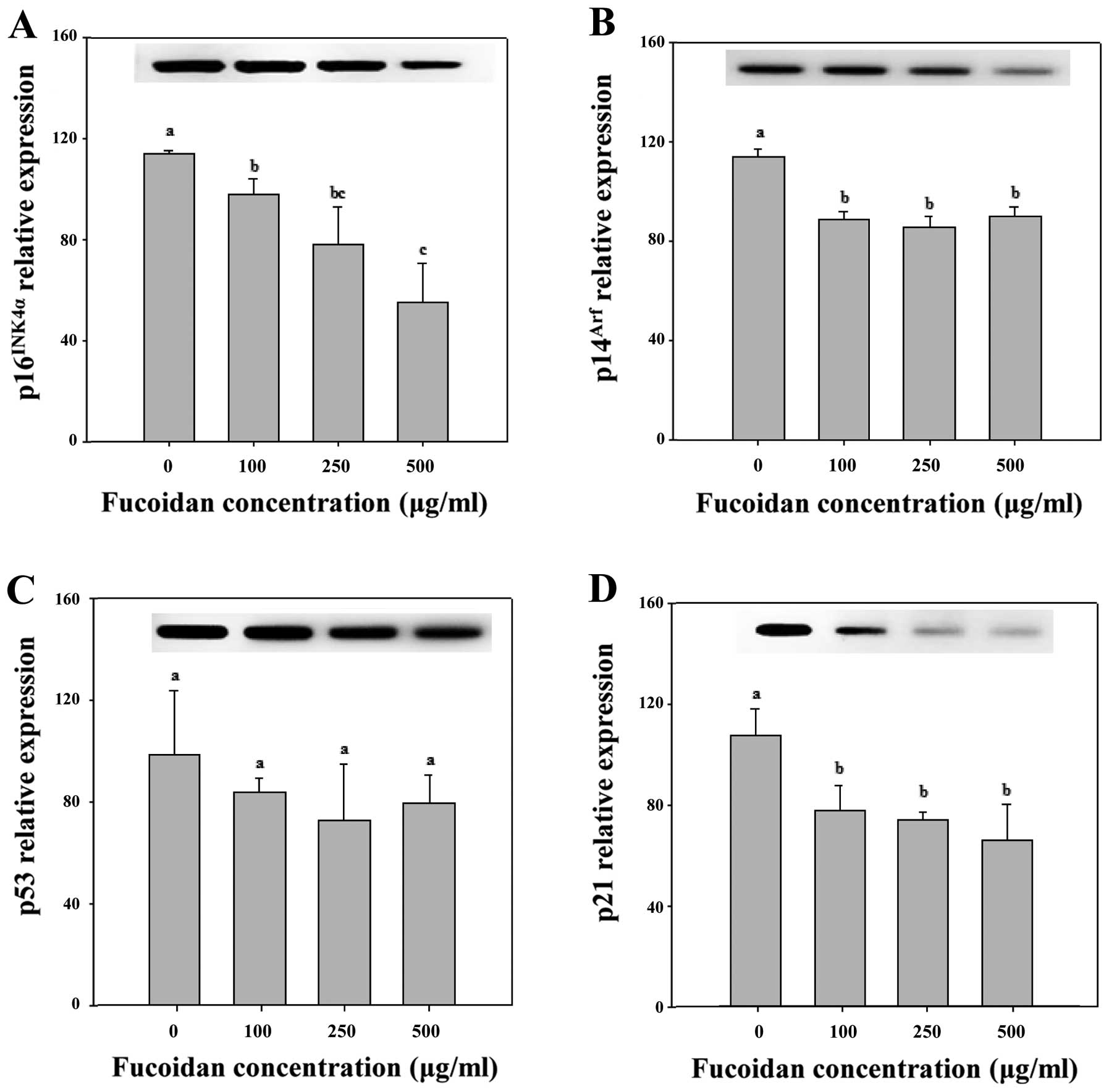

Expression of p16INK4a-pRb

pathway-related proteins in fucoidan-treated cells

To evaluate the mechanism underlying the

tumor-suppressing activity of fucoidan, we examined the expressions

of p16INK4a, Cdk4/6 and pRb by western blotting in HepG2

cells after treatment with fucoidan for 24 h. We further explored

the mechanism of this antitumor action by evaluating mRNA

expression by real-time PCR.

The p16INK4a is a key component of the Rb

pathway that can inhibit the activity of Cdks, thereby preventing

proliferating cells from entering the S phase (22). As shown in Figs. 4A and 5, 250 and 500 μg/ml fucoidan

significantly increased p16INK4a expression levels in

HepG2 cells (P<0.05). We determined that fucoidan likely

activates the Cdk4 and pRb pathway by triggering

p16INK4a overexpression and maintaining the

hypophosphorylated state of Rb (Figs.

4A and 5). Therefore, we

determined that p16INK4a arrests cells in the G1 phase

by inhibiting the activities of Cdk4 and pRb (Table II).

To identify the effects of fucoidan that regulate

cell growth arrest and thus promote cellular senescence in Chang-L

cells, we analyzed p16INK4a/Cdk4 and Cdk6/pRb, which are

primarily responsible for inhibiting cell growth and inducing

cellular senescence (23). The

activation of p16INK4a is a common step in the induction

of senescence arrest. However, in Chang-L cells treated with

fucoidan, overexpression of p16INK4a protein was not

detected (Figs. 4B and 6). In addition, Cdk4-dependent activation

of pRb, which is important for cell cycle arrest, did not

significantly change (Fig. 4). The

p16INK4a also links several senescence-initiating

signals to p53 activation. However, fucoidan resulted in a

significant downregulation of p16INK4a compared to

non-treated Chang-L cells when analyzed by real-time PCR (Fig. 6).

Expression of p14Arf-p53

pathway-related proteins in fucoidan-treated cells

The p14Arf and p16INK4a are

key tumor suppressor genes that inactivate p53. To explore the

effects of the p14Arf-p53 pathway on maintaining

senescence arrest by fucoidan, we analyzed the expression of the

pathway in Chang-L cells by western blotting and real-time PCR. We

further investigated the tumor suppressor activity of fucoidan in

HepG2 cells through the p14Arf-p53 pathway.

Although p14Arf protein expression was

not detected by western blotting, the expression of

p14Arf mRNA was detected in both HepG2 and Chang-L

cells. Real-time PCR determined that fucoidan significantly

increased p14Arf mRNA expression in HepG2 cells at

concentrations of 250 and 500 μg/ml (Fig. 5) but significantly decreased

expression in Chang-L cells (Fig.

6). Hence, fucoidan suppresses p14Arf expression as

well as p16INK4a expression in Chang-L cells.

In parallel experiments, treatment of HepG2 cells

with 250 and 500 μg/ml fucoidan increased the protein

expression of p53 and p21, which are involved in the activation of

tumor suppressors (Fig. 4A), and

upregulated p53 mRNA. Furthermore, fucoidan-induced p53 mRNA

resulted in upregulation of p21 mRNA (Figs. 4A and 5).

In Chang-L cells, the mRNA levels of

p14Arf and p21, which are involved in cellular

senescence, were significantly lower at concentrations >100

μg/ml (Fig. 6). However,

fucoidan treatment did not significantly affect p53 mRNA compared

to controls (Fig. 6). Thus,

decreased expression of p14Arf and p21 induced

senescence arrest due to inactivation of the p53 pathway, and

significant changes in the cell cycle were observed after treatment

with fucoidan (Fig. 4B, Table II).

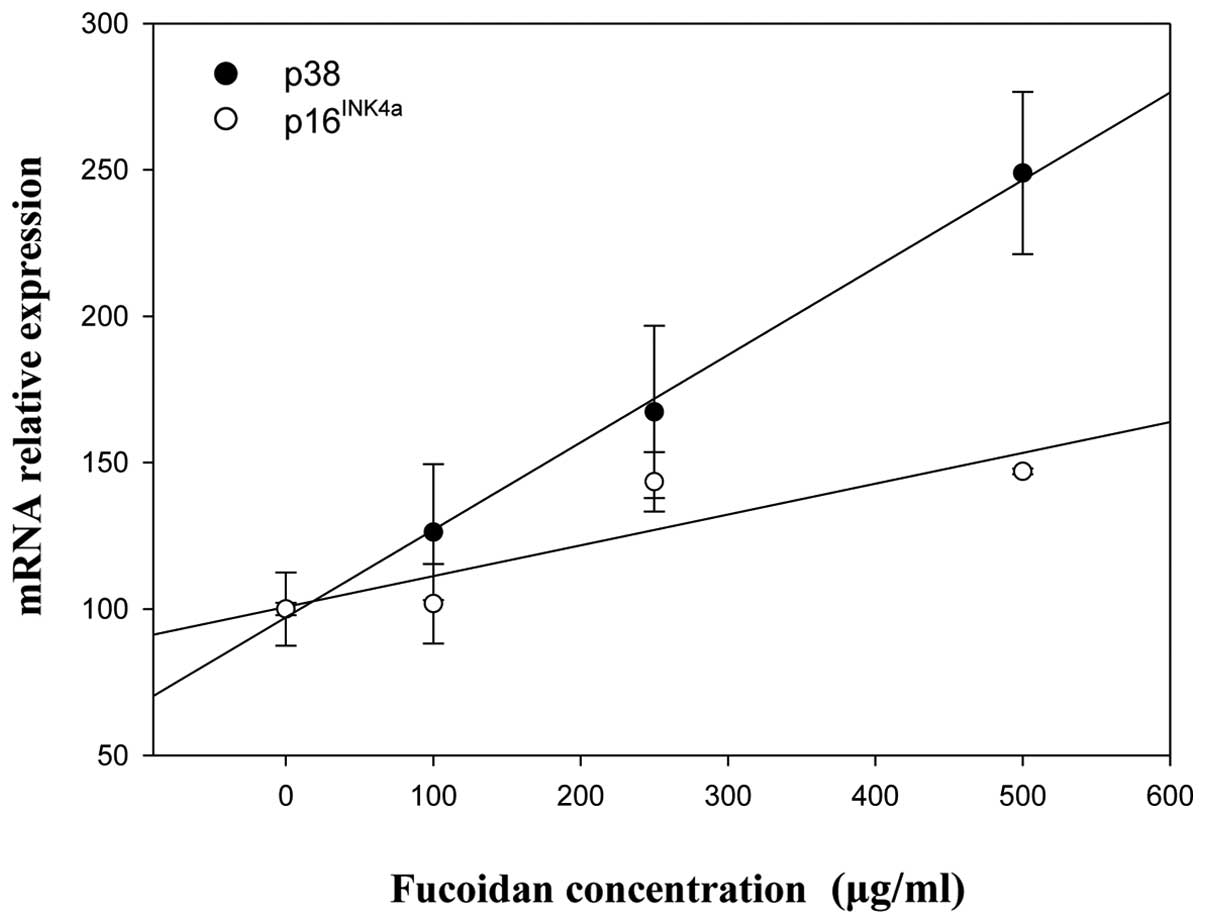

Expression of p38 MAPK in

fucoidan-treated cells

p38 MAPK can trigger premature senescence in primary

cells and permanent oncogene-induced proliferative arrest, which

has been proposed as an anti-tumorigenic defense mechanism that

induces p53 phosphorylation and upregulation of p16INK4a

(18). We defined whether

activation of p38 MAPK mediated tumor suppression and replicative

senescence, and examined the relationship between

fucoidan-stimulated activation of p16INK4a/p53 and p38

MAPK in HepG2 and Chang-L cells (Fig.

1). We further determined whether the expression of

phosphorylated p38 MAPK increased in both cell types. Fucoidan

dose-dependently elevated phospho-p38 MAPK (Fig. 4A) and p38 MAPK gene expression in

HepG2 cells (Fig. 7). In contrast,

it did not significantly affect p38 and phospho-p38 protein levels

in Chang-L cells (Fig. 4B).

Correlation analysis was used to examine the

relevance of p38 MAPK, p16INK4a and p53 expression after

fucoidan treatment of HepG2 and Chang-L cells. Positive

correlations between p38 MAPK and p16INK4a/p53 were

found in HepG2 cells (Fig. 9),

whereas p38 MAPK was closely related with p16INK4a in

Chang-L cells (data not shown). However, the levels of p53 mRNA

were not associated with p38 MAPK (data not shown).

Gene expression of α2M as an

aging biomarker

The expression of α2M can easily be

measured by real-time PCR and it is a more suitable biomarker

candidate of aging then well-known senescence-associated genes such

as p16INK4a.

Compared to controls, the mRNA level of

α2M significantly increased in HepG2 cells treated with

fucoidan in a manner similar to p16INK4a expression

(Fig. 8). In Chang-L cells,

fucoidan treatment dose-dependently decreased α2M

expression, but not p16INK4a. When we compared HepG2 and

Chang-L cells, a significant difference in α2M mRNA

levels was noted after incubation with 250 and 500 μg/ml

fucoidan (Fig. 8).

Discussion

Natural products have played a pivotal role in the

quest to develop novel chemotherapeutic agents with enhanced

specificity and potency in liver cancer. Many marine compounds have

chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effects through various

cell-signaling pathways involved in the transduction of mitogenic

signals and subsequent regulation of cell growth and proliferation

(24).

The diverse biological activities of fucoidan have

been studied intensively and include anti-oxidant,

immunomodulatory, anti-virus and anti-coagulant effects (3,4,25,26).

In particular, the anti-tumor activity has recently attracted

considerable attention and several studies have addressed its

anti-carcinogenic effects (7).

Fucoidan inhibits the growth of a wide variety of tumor cells

(3,26), which has become a focus of great

interest because it is expected to be a new candidate for

low-toxicity cancer therapy (7).

Cancer cells need to evade anti-proliferative

signals that negatively regulate growth and proliferation. Cancer

cells can avoid this control step by losing the physiological

function of the pRb, which controls all anti-proliferative signals

(24). Consequently, natural

product compounds that inhibit constitutive hyper-phosphorylation

of pRb contribute efficiently to the reestablishment of regulated

growth in cancer (24). In cancer

cells, the hyper-proliferation stress response tends to be

suppressed, allowing the continued proliferation of cells carrying

overactive mitogenic signals. Hyper-proliferation signals lead to

increased levels of p16INK4a and p14Arf

resulting in cell cycle arrest or cell death through the pRb and

p53 pathways. In many cell types, particularly in humans, the Cdk

inhibitor p16INK4a contributes to the cell cycle arrest

that occurs after hyper-proliferation stress. Thus, the loss of

p16INK4a, which occurs in many cancers, helps abolish

this response in some cell types. Some cancer-associated

chromosomal deletions disrupt both p16INK4a and

p14Arf genes, thereby knocking out regulators of both

the pRb and p53 pathways. Loss of p53 function is a remarkably

common event in tumor cells because it allows cell proliferation to

continue following different forms of stress and DNA damage

(27). In addition, the

INK4/Arf locus gene, p16INK4a and

p14Arf (or p19Arf in mouse), which is

upregulated during aging (28) has

been genetically linked to numerous aging-associated diseases in

humans (29). Accordingly, we

anticipated that marine compounds such as fucoidan could have

chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effects by regulating the

expression of p16INK4a, p14Arf and p53 in

cancer cells.

Fedorov et al showed that the natural marine

chamigrane-type sesquiterpenoid dactylone inhibited cyclin D, Cdk4

expression and pRb phosphorylation (30). The inhibition of these cell cycle

components was followed by cell cycle arrest at the G1-S

transition, with subsequent p53-independent apoptosis in human

cancer cells. Park et al described the suppression of U937

human monocytic leukemia cell growth by dideoxypetrosynol A, a

polyacetylene from the sponge Petrosia sp., via induction of

the Cdk inhibitor p16INK4a and downregulation of pRb

phosphorylation (31).

Interestingly, the wild-type p53 gene is often

inactivated in HepG2 cells (32).

However, we determined that fucoidan significantly upregulated the

expression of p53 in HepG2 cells, while simultaneously inducing

apoptosis with inhibition of cellular proliferation (Figs. 2 and 3). Real-time PCR and western blotting

studies correlated increased mRNA and protein expression for

p16INK4a and p21 (Figs.

4A and 5). These results

suggest that the growth arrest in hepatocellular carcinoma cells

results from an increase in p53-mediated p21 expression as cells

enter senescence, followed by a sustained elevation of

p16INK4a (Fig. 5).

The p21 gene is a cell cycle inhibitor and tumor

suppressor downstream of p53. When cells are damaged, p53 and p21

act together to inactivate the cyclin-Cdk complex, which could

mediate G1 and G2/M arrest (33). In this study, induction of

G1 arrest by fucoidan was accompanied by a large

accumulation of p53 and p21. In particular, p21 sustains

hypophosphorylated Rb and arrests cells in the G1 phase.

Therefore, we can deduce that the anti-proliferative effect of

fucoidan regulates pRb- or p53-mediated cell cycle arrest in HepG2

cells (Table II). This supports

the idea that p16INK4a-pRb-mediated G1 arrest

by fucoidan is elicited by p53 and p21 upregulation.

Fujii et al suggested that the expression of

INK4a/Arf locus genes p16INK4a and

p14Arf could be related to cellular senescence and

apoptosis and reported that expression of this locus was increased

by valproic acid treatment and induced apoptosis in sphere cells

from rat sarcomas (34). We also

demonstrated that fucoidan caused induction of apoptosis and tumor

suppression by p16INK4a and p14Arf

overexpression in HepG2 cells but did not affect normal Chang-L

cells. Resistance to apoptosis by cancer cells can be acquired

through a variety of strategies, including p53 tumor suppressor

gene inactivation. The p53 can lead to induction of the apoptotic

cascade (24). However, numerous

studies have determined that p38 MAPK may be correlated with

apoptosis in various cancer cells (35). The p38 MAPK can regulate cell

proliferation and apoptosis through phosphorylation of p53,

increased c-myc expression and regulation of Fas/FasL-mediated

apoptosis (36). The impact of p38

MAPK on cell cycle regulators plays a crucial role in

oncogene-induced senescence involved in the suppression of

tumorigenesis and replicative senescence (18). Indeed, we found that fucoidan

induced the activation of p38 protein and mRNA in HepG2 cells. Our

results show that activation of p38 leads to increased expression

of p16INK4a, similarly to previous reports on

oncogene-induced senescence (19).

These studies indicate that p53 is a downstream effector of p38

MAPK, which has been proposed to function as an anti-tumorigenic

defense mechanism by inducing p53 and upregulating

p16INK4a.

We found that fucoidan treatment induced

phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and concurrently increased p38 MAPK in

HepG2 cells. Consistent with these results, a previous study

determined that the anti-tumor activity of fucoidan was mediated by

the induction of apoptosis through the activation of p38 MAPK in

human colon carcinoma cells (37).

Interestingly, in a previous study, honokiol, a novel antitumor

agent isolated from a plant, increased the phosphorylated p38 MAPK

without affecting p38 expression in HepG2 cells (35). Numerous studies have demonstrated

that increased levels of phosphorylated p38 are correlated with

malignancy in various cancers (38,39).

These data support the hypothesis that fucoidan may have

therapeutic potential for cancer treatment.

In summary, in HepG2 cells, it is apparent that

p16INK4a upregulation is a key event in anti-tumor

activity, and that fucoidan-induced overexpression of p38 MPAK is

associated with the p14Arf-p53 pathway during apoptosis.

This suggests that fucoidan treatment can induce growth-suppressive

signals from both p16INK4a-Rb and p14Arf-p53

pathways, a valuable therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment

(Fig. 4A). However, in Chang-L

cells, no increase in these pathway-related proteins was noted and

no evidence for apoptosis was observed after fucoidan treatment

(Fig. 4B). Among the marine

compounds, lactone spongistatin induces the degradation of XIAP

(40), an anti-apoptotic protein

that is overexpressed in chemoresistant cancer cells (41). This compound, similar to our

results, does not induce apoptosis in healthy peripheral blood

cells (40). Therefore, we suggest

that fucoidan could have selective chemotherapeutic effects.

Cellular senescence is an aging mechanism that

prevents cell renewal, leading to apoptosis and increased

expression of the tumor suppressor gene p16INK4a

(42). As proof of the stochastic

model, early fibroblasts have low levels of p16INK4a but

aging fibroblasts show significantly increased p16INK4a

expression (43). The loss or

inactivation of p16INK4a is correlated with cell

immortality (44). Given the

postulated importance of p16INK4a in cell senescence, it

is expected that inhibition of p16INK4a would extend the

proliferative life span of cultured cells (45). In the present study, we

investigated in detail the pathways induced by fucoidan in a normal

liver cell line. The expression of p16INK4a and

p14Arf mRNA significantly decreased with increasing

fucoidan concentration (Fig. 6).

Carnero et al used a strategy to express antisense

p16INK4a and p19Arf (p14Arf in

human) RNA in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (46). Consequently, the lifespan of MEFs

was extended, and a percentage of these cells eventually became

immortal. Their study suggested that cellular immortality derived

from p16INK4a acts through the Rb pathway, whereas

p19Arf acts through both the p53 and Rb pathways.

Furthermore, Jung et al determined that the

p14Arf-p53-p21 pathway, in addition to the

p16INK4a-Rb pathway, controls senescence (47). Phosphorylation of Rb results in

increased p16INK4a expression, which inhibits Cdk4/6

resulting in increased levels of hypophosphorylated Rb and

decreased p16INK4a expression (12,13).

The p14Arf-p53 pathway is important as part of the

normal life cycle of many cells; it regulates a cell’s entrance

into senescence (48). In the

present study, the expression of p14Arf and p21 mRNA was

significantly downregulated, regardless of protein expression in

Chang-L cells. However, the expression of p53 did not appear to

change significantly under the same conditions. In agreement,

several experimental studies have observed p14Arf in

senescent human fibroblasts, independent of p53 (16,48).

Moreover, the upregulation of p21 in aging and senescent human

fibroblasts is well documented (11,49).

It should be noted that INK4a/Arf expression

is both a biomarker and effector of aging. Our results suggest that

fucoidan prevented senescence in hepatoma cells by mediating a

process that included a decrease in p14Arf expression as

cells entered quiescence followed by a decline in the level of

p16INK4a. We must be clear that these results do not

negate an anti-aging effect of fucoidan in normal hepatic cells,

but only indicate that reduced levels of these proteins are not

enough to cause cellular longevity. Therefore, we examined other

clinical biomarkers of aging. Like oncogene-induced senescence,

replicative senescence is identified by senescence biomarkers such

as SA-β-gal and α2M. The α2M and SA-β-gal

expression is accompanied by increased expression of negative

growth regulators including p53, p21, p16INK4a and

p14Arf (20).

α2M is a major plasma protein that functions as a

panprotease inhibitor. Ma et al showed that expression of

p16INK4a at each passage was exponentially correlated

with cumulative population doubling level (PDL) (21), in agreement with previous reports

on p16INK4a (45), and

provided further evidence that mRNA expression of α2M

had a positive linear correlation with cumulative PDL, similar to

p16INK4a. These results, including the positive

relationship between α2M and p16INK4a,

suggest that α2M mRNA expression can be used as a

biomarker of cellular senescence (21). Another study found that the amount

of α2M fragment derived from culture medium increased as

the cells aged (50). We attempted

to identify changes that are essential for a cellular anti-aging

response by comparing the effects of fucoidan on α2M

mRNA expression in HepG2 and Chang-L cells. We found that

expression of α2M was upregulated in HepG2 cells, but

significantly downregulated in Chang-L cells after incubation with

fucoidan. These results suggest that fucoidan has the

anti-senescence effect in normal hepatic cell line. As we have

seen, there are several independent pathways that control

replicative senescence in human cells.

In conclusion, fucoidan arrests cells in the

G1 phase through p16INK4a and

p14Arf in HepG2 cells. It also increases the activity of

tumor suppressor proteins p53 and p38 MAPK, which play a critical

role in the regulation of apoptosis. Accordingly, in addition to

directly inhibiting the proliferation of tumor cells, fucoidan may

also restrain the development of tumor cells by inducing apoptosis.

Fucoidan also affected the senescence of Chang-L cells by

decreasing mRNA expression of p16INK4a,

p14Arf, p21 and the senescence biomarker α2M.

These findings suggest that fucoidan may offer substantial

therapeutic potential for cancer treatment without inducing

senescence in normal cells, and that it may be possible to use

fucoidan therapeutically.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic

Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation

of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and

Technology (2012R1A6A1028677).

References

|

1.

|

Li Y, Nichols MA, Shay JW and Xiong Y:

Transcriptional repression of the D-type cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor p16 by the retinoblastoma susceptibility gene product

pRb. Cancer Res. 54:6078–6082. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Dürig J, Vruhn T, Zurborn KH, Gutensohn K,

Bruhn HD and Bèress L: Anticoagulant fucoidan fractions from

Fucus vesiculosus induce platelet activation in

vitro. Thromb Res. 85:479–491. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Maruyama H, Tamauchi H, Hasimoto M and

Nakano T: Antitumor activity and immune response of Mekabu fucoidan

extracted from Sporophyll of Undaria pinnatifida. In vivo.

17:245–249. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Wang J, Zhang Q, Zang Z and Li Z:

Antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide fractions extracted

from Laminaria japonica. Int J Biol Macromol. 42:127–132.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Hu T, Liu D, Chen Y, Wu J and Wang S:

Antioxidant activity of sulfated polysaccharide fractions extracted

from Undaria pinnitafida in vitro. Int J Biol Macromol.

46:193–198. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Lee H, Kim JS and Kim E: Fucoidan form

seaweed Fucus vesiculosus inhibits migration and invasion of

human lung cancer cells via PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathways. PLoS One.

7:e506242012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Xue M, Ge Y, Zhang J, et al: Anticancer

properties and mechanisms of fucoidan on mouse breast cancer in

vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 7:e434832012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Kim NY, Sun JM, Kim YJ, et al:

Cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy for advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma: a single centre experience before the

sorafenib era. Cancer Res Treat. 42:203–209. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Rayess H, Wang MB and Srivatsan ES:

Cellular senescence and tumor suppressor gene p16. Int J Cancer.

130:1715–1725. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Krishnamurthy J, Torrice C, Ramsey MR, et

al: Ink4a/Arf expression is a biomarker of aging. J Clin Invest.

114:1299–1307. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Stein GH, Drullinger LF, Soulard A and

Dulić V: Differential roles for cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

p21 and p16 in the mechanisms of senescence and differentiation in

human fibro-blasts. Mol Cell Biol. 19:2109–2117. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Li B, Lu F, Wei X and Zhao R: Fucoidan:

structure and bioactivity. Molecules. 13:1671–1695. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Hara E, Smith R, Parry D, Tahara H, Stone

S and Peters G: Regulation of p16CDKN2 expression and its

implications for cell immortalization and senescence. Mol Cell

Biol. 16:859–867. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Haber DA: Splicing into senescence: the

curious case of p16 and p19Arf. Cell. 91:555–558. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liégeois

NJ, et al: Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf,

interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM2’s inhibition of p53. Cell.

92:713–723. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Dimri GP, Itahana K, Acosta M and Campisi

J: Regulation of a senescence checkpoint response by the E2F1

transcription factor and p14Arftumor suppressor. Mol

Cell Biol. 20:273–285. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Sharpless NE: INK4a/ARF: A multifunctional

tumor suppressor locus. Mutat Res. 576:22–38. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Han J and Sun P: 2007. The pathways to

tumor suppression via route p38. Trends Biochem Sci. 32:364–371.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Bulavin DV and Fornace AJ Jr: p38 MAPK

kinase’s emerging role as a tumor suppressor. Adv Cancer Res.

92:95–118. 2004.

|

|

20.

|

Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D

and Lowe SW: Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence

associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell.

88:593–602. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Ma H, Li R, Zhang Z and Tong T: mRNA level

of alpha-2-macro-globulin as an aging biomarker of human

fibroblasts in culture. Exp Gerontol. 39:415–421. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Serrano M: The INK4a/ARF locus in murine

tumorigenesis. Carcinogenesis. 21:865–869. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, et al: A

senescence program controlled by p53 and

p16INK4acontributes to the outcome of cancer therapy.

Cell. 109:335–346. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Schumacher M, Kelkel M, Dicato M and

Diederich M: Gold from the sea: marine compounds as inhibitors of

the hallmarks of cancer. Biotechnol Adv. 29:531–547. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Ishii H, Iwatsuki M, Ieta K, et al: Cancer

stem cells and chemoradiation resistance. Cancer Sci. 99:1871–1877.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26.

|

Alekseyenko TV, Zhanayeva SY, Venediktova

AA, et al: Antitumor and antimetastatic activity of fucoidan, a

sulfated polysaccharide isolated from the Okhotsk Sea Fucus

evanescens brown alga. Bull Exp Biol Med. 143:730–732. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Meek DW: 2009. Tumour suppression by p53:

a role for the DNA damage response? . Nat Rev Cancer. 9:714–723.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, et

al: p16INK4ais a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular

aging in human skin. Aging Cell. 5:379–389. 2006.

|

|

29.

|

Melzer D: Genetic polymorphisms and human

aging: association studies deliver. Rejuvenation Res. 11:523–526.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Fedorov SN, Shubina LK, Bode AM, Stonik VA

and Dong Z: Dactylone inhibits epidermal growth factor-induced

transformation and phenotype expression of human cancer cells and

induces G1-S arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 67:5914–5920. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31.

|

Park C, Kim GY, Kim GD, et al: Suppression

of U937 human monocytic leukemia cell growth by dideoxypetrosynol

A, a polyacetylene from the sponge Petrosia sp., via induction of

Cdk inhibitor p16 and down-regulation of pRB phosphorylation. Oncol

Rep. 16:171–176. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Müller M, Strand S, Hug H, et al:

Drug-induced apoptosis in hepatoma cells is mediated by the CD95

(APO-1/Fas) receptor/ligand system and involves activation of

wild-type p53. J Clin Invest. 99:403–413. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Vogelstein B, Lane D and Levine AJ:

Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 408:307–310. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Fujii H, Honoki K, Tsujiuchi T, et al:

Reduced expression of INK4a/ARF genes in stem-like sphere cells

from rat sarcomas. Biochem Biophysic Res Commun. 362:773–778. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35.

|

Deng J, Qian Y, Geng L, et al: Involvement

of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in honokiol-induced

apoptosis in a human hepatoma cell line (HepG2). Liver Int.

28:1458–1464. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36.

|

Wang YX, Xu XY, Su WL, et al: Activation

and clinical significance of p38 MAPK signaling pathway in patients

with severe trauma. J Surg Res. 161:119–125. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Hyun JH, Kim SC, Kang JI, et al: Apoptosis

inducing activity of fucoidan in HCT-15 colon carcinoma cells. Biol

Pharm Bull. 32:1760–1764. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

Iyoda K, Sasaki Y, Horimoto M, et al:

Involvement of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in

hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 97:3017–3026. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Wagner EF and Nebreda AR: Signal

integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat

Rev Cancer. 9:537–549. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Schyschka L, Rudy A, Jeremias I, Barth N,

Pettit GR and Vollmar AM: Spongistatin 1: a new chemosensitizing

marine compound that degrades XIAP. Leukemia. 22:1737–1745. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Igney FH and Krammer PH: Death and

anti-death: tumor resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer.

2:277–288. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Verzola D, Gandolfo MT, Gaetani G, et al:

Accelerated senescence in the kidneys of patients with type 2

diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 295:F1563–F1573.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43.

|

Tsygankow D, Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Sharpless

NE and Elston TC: A quantitative model for age-dependent expression

of the p16INK4atumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:16562–16567. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44.

|

Huschtscha LI and Reddel RR:

p16INK4aand the control of cellular proliferative life

span. Carcinogenesis. 20:921–926. 1999.

|

|

45.

|

Duan J, Zhang Z and Tong T: Senescence

delay of human diploid fibroblast induced by anti-sense

p16INK4aexpression. J Biol Chem. 276:48325–48331.

2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46.

|

Carnero A, Hudson JD, Price CM and Beach

DH: p16INK4Aand p19ARF act in overlapping pathways in

cellular immortalization. Nat Cell Biol. 2:148–155. 2000.

|

|

47.

|

Jung YS, Qian Y and Chen X: Examination of

the expanding pathway for the regulation of p21 expression and

activity. Cell Signal. 22:1003–1012. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48.

|

Collado M, Blasco MA and Serrano M:

Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 130:223–233. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Tahara H, Sato E, Noda A and Ide T:

Increase in the expression level of

p21sdi1/cip1/waf1 with increasing division age

in both normal and SV40-transformed human fibroblasts. Oncogene.

10:835–840. 1995.

|

|

50.

|

Kondo T, Sakaguchi M and Namba M:

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis studies on the cellular aging:

accumulation of alpha-2-macroglobulin in human fibroblasts with

aging. Exp Gerontol. 36:487–495. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|