Introduction

Neuroblastoma is an aggressive pediatric tumor that

accounts for ~15% of all cancer-related deaths in children. It

originates from neural crest cells and shows extreme heterogeneity

ranging from spontaneous regression to malignant progression.

Approximately 50% of neuroblastoma patients are stratified into a

high-risk group with the overall survival rate of <40% (1–3).

Over the years, two major advances have been incorporated into the

current therapy for high-risk patients (4). First, patients treated with the

differentiation agent 13-cis-retinoic acid (13-cis-RA) after

myeloablative consolidation therapy had a significantly decreased

rate of relapse (5). Second, the

combination of 13-cis-RA with anti-GD2 antibody and cytokines in

maintenance therapy further improved a relapse-free survival rate

(6). Despite these improvements,

50–60% of patients who complete these treatments still experience a

tumor relapse. As in other cancers, neuroblastoma relapse is

primarily driven by chemoresistant cancer stem cells (CSCs)

(7–9).

A number of studies have isolated neuroblastoma CSCs

as spheres grown in serum-free non-adherent culture used for neural

crest stem cell growth (10), side

population cells based on the efficient efflux of Hoechst 33342 dye

from stem cells used to isolate hematopoietic stem cells (11) and cell-surface marker-positive

cells based on the markers associated with stem cell populations in

other cancers (12–14). Although these studies provide an

important insight into the properties of neuroblastoma CSCs, their

definitive markers are still missing.

Aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDHs) are a family of

NAD(P)+-dependent enzymes that catalyze the oxidation of

aldehydes to their corresponding carboxylic acids. They not only

serve to protect cells from the cytotoxic effects of xenobiotic and

intracellular aldehydes such as cyclophosphamide and ethanol, but

also generate important carboxylic acids in cellular physiology

such as retinoic acid (RA) and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (15). High ALDH activity was first found

in hematopoietic stem cells and normal stem cells isolated from a

variety of tissues (16) and then

detected in CSCs of certain cancers (17,18).

Among all 19 ALDH isoforms identified in human cells, several

isoforms were proposed as CSC-markers; ALDH1A1 in lung cancer

(19), ALDH1B1 in colon cancer

(20) and ALDH7A1 in prostate

cancer (21). However, ALDH

remains elusive in neuroblastoma.

In the present study, we analyzed the ALDH activity

and expression of its 19 isoforms in spheres and parental cells of

different neuroblastoma cells and found that ALDH1A2 was involved

in the regulation of CSC properties in neuroblastoma.

Materials and methods

Neuroblastoma cells

BE(2)-C (CRL-2268) cells were obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Human

neuroblastoma NBTT1, NBTT2D and NBTT3 cells were previously

described (22,23). Tumor tissue samples were obtained

from high-risk neuroblastoma patients with written informed

consent. The use of human tissues for this study was approved by

the Ethics Committee at Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine

and conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for the Clinical

Research of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine.

Antibodies

The rabbit anti-PGK1 antibody was purchased from

Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), rabbit anti-NF-M antibody from

Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA), rabbit anti-ALDH1A2 antibody from

Atlas antibodies (Stockholm, Sweden) and rabbit anti-NANOG antibody

from ReproCELL (Tokyo, Japan).

Expression plasmids

The N-terminal 3xFLAG-tagged expression plasmid with

IRES-driven GFP and puromycin markers (pRS-3FLAG-IRES-GFP) was

constructed. Briefly, the U6 promoter expression unit of pRS vector

(Origene, Rockville, MD, USA) was first replaced with the

CMV-promoter expression unit of pCMV6-AC-IRES-GFP vector (Origene)

using In-Fusion HD Cloning kit (Takara, Otsu, Japan). The

3xFLAG-tag was then inserted into the SgfI site within multiple

cloning sites of the resulting plasmid. The full-length ALDH1A2

cDNA (NM_003888) was amplified by PCR using PrimeStar GXL DNA

polymerase (Takara), cloned into pRS-3FLAG-IRES-GFP and sequenced

using an ABI PRISM 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA, USA). Scramble and specific short hairpin RNA

(shRNA) expression plasmids (pGFP-V-RS-scramble shRNA,

pGFP-V-RS-ALDH1A2 shRNA, pGFP-V-RS-ALDH1L1 shRNA and

pGFP-V-RS-ALDH3B2 shRNA) were obtained from Origene and their

sequences are listed in Table

I.

| Table IshRNA sequences. |

Table I

shRNA sequences.

| Gene name | Accession no. | Sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| ALDH1A2 | NM_003888 | #1:

ccaataactcagactttggactcgtagca

#2: tgtgttcttcaatcaaggtcagtgctgca |

| ALDH1L1 | NM_012190 | #1:

gtggtcaccaaagcaggactcatcctctt

#2: catccagaccttccgctactttgctggct |

| ALDH3B2 | NM_000695 | #1:

cagtacctggaccagagctgctttgccgt

#2: tcatcaaccagaaacagttccagcggctg |

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA from neuroblastoma cells and spheres was

isolated with a TRIzol Plus RNA purification kit (Invitrogen,

Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed using a QuantiTect

Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to

the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as

described previously (22). Primer

sequences are listed in Table

II.

| Table IIRT-PCR primer sequences. |

Table II

RT-PCR primer sequences.

| Gene name | Accession no. | Forward sequence

(5′-3′) | Reverse sequence

(5′-3′) |

|---|

| PGK1 | NM_000291 |

ggagaacctccgctttcat |

gctggctcggctttaacc |

| ALDH1A1 | NM_000689 |

tttggtggattcaagatgtctg |

cactgtgactgttttgacctctg |

| ALDH1A2 | NM_003888 |

tgcattcacagggtctactga |

tgcctccaagttccagagtt |

| ALDH1A3 | NM_000693 |

aacccctgcatcgtgtgt |

tggttgaagaacactccctga |

| ALDH1B1 | NM_000692 |

ttctcgagagaaccgtggag |

gtccagctcaaaggggttc |

| ALDH1L1 | NM_012190 |

gaccttccgctactttgctg |

ggtctggcctggttgatg |

| ALDH1L2 | NM_001034173 |

ttgacaaggctgtgcgaat |

cccagcagcaatacagttctc |

| ALDH2 | NM_000690 |

tggatttggacatggtcctc |

gatggttttcccgtggtactt |

| ALDH3A1 | NM_001135168 |

gatccaggagcaggagca |

tgtactcgatctcctctaggacgta |

| ALDH3A2 | NM_001031806 |

agcagagatgaacaccagatttc |

aggaggttgaacaggatcattc |

| ALDH3B1 | NM_000694 |

cgcatcatcaaccagaaaca |

tctcctgcacatccaccag |

| ALDH3B2 | NM_000695 |

ttcatcaaccggcaggag |

ctccagcatctggttcacaa |

| ALDH4A1 | NM_003748 |

agagcaaggaccctcagga |

cagacagtacaggcccgaag |

| ALDH5A1 | NM_170740 |

caacgtggaccaggctgta |

tgcaccaagaattggtttga |

| ALDH6A1 | NM_005589 |

gcccctgatggaacattaaa |

tccggatgatcgcaaataa |

| ALDH7A1 | NM_001182 |

gacctatcttgccttctgaaaga |

gattccaaccaggcctacg |

| ALDH8A1 | NM_022568 |

aaccgtcaggtccagcttt |

cactatagatgctcttctggacaaa |

| ALDH9A1 | NM_000696 |

ctccagcattagcctgtggt |

agccagtagcaatgcagaaac |

| ALDH16A1 | NM_153329 |

agacgtccaggccatgtg |

gaggcccactcgacaaact |

| ALDH18A1 | NM_002860 |

tctcgtcctgactgtctaccc |

taacaagccattgccacttg |

Cell culture and transfection

Parental cells and spheres of BE(2)-C, NBTT1, NBTT2D

and NBTT3 cells were cultured as described previously (24). BE(2)-C cells were transfected with

expression plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent

(Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stably

transfected GFP-positive cells were selected by 2.0–3.0 μg/ml

puromycin (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA) and further isolated by

using MoFlo XDP (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA).

ALDH activity

ALDH activity was determined using the Aldefluor kit

(Stem Cell Technologies, Durham, NC, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, neuroblastoma cells and

spheres were dissociated with Accumax (Innovative Cell

Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA) and suspended at

~1×106 cells/ml in Aldefluor assay buffer containing

BODIPY-aminoacetaldehyde (BAAA) in the presence or absence of 15 μM

diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), incubated at 37°C for 40 min and

then treated with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI; Sigma). Flow

cytometric analysis was performed using MoFlo XDP. Specific ALDH

activity was based on the difference between the presence and

absence of DEAB.

Sphere and colony formation

Sphere formation was analyzed as described

previously (24). For colony

formation, BE(2)-C cells expressing the indicated shRNA or cDNA

were mixed in 0.325% SeaPlaque agarose (Lonza, Rockland, ME, USA)

in DMEM/Ham’s F12 (3:1) (Wako Pure Chemical, Osaka, Japan) with 10%

FBS and plated at 1,000 cells/well onto a solidified bottom layer

of 0.6% SeaPlaque agarose in DMEM/Ham’s F12 with 10% FBS in a

6-well plate. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 21 days, stained

with 0.5 mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium

bromide (MTT; Sigma) and photographed. The total number of colonies

was counted manually.

Tumor formation

Four-week-old male athymic BALB/cAJcl nu/nu (nude)

mice were obtained from CLEA (Shizuoka, Japan). All procedures

involving animals were approved by the Animal Care and Use

Committee of Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine and

carried out in strict accordance with the Guidelines for the Care

and Use of Laboratory Animals of Kobe University Graduate School of

Medicine. BE(2)-C cells expressing the indicated shRNA or cDNA in

50% Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were

injected subcutaneously into the flank of nude mice at a density of

1×105 cells per injection site. Tumor growth was

monitored 3 times per week by external caliper and tumor volume (V)

was calculated by the formula: V = 1/2 (L × W2), where L

and W were the greatest longitudinal and transverse diameters

(25). Mice were dissected when

the greatest diameter of tumor reached 20 mm. Xenograft tumors were

fixed in 20% buffered neutral formalin solution (Muto Pure

Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) and embedded in paraffin. Tumor sample was

sectioned 4-μm thick, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in

alcohol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of neuroblastoma

xenografts was performed on the 4-μm thick sections of tumor

samples. After antigen retrieval using a conventional steamer with

citrate buffer (pH 6.0), the section was immunostained with a

primary antibody in REAL antibody diluent (Dako, Glostrup,

Denmark). The section was then blocked with peroxidase blocking

reagent (Dako) and incubated with EnVision labeled polymer

peroxidase (Dako). The immune complex was visualized using 3,

3′-diaminoben-zidine (DAB; Dako) as a chromogen and hematoxylin as

a counterstain. To quantify the average percentage of immunostained

cells, three fields containing ≥300 neuroblastoma cells were

randomly selected from each sample. Positive cells were identified

microscopically as brown cytoplasmic staining and manually

counted.

Other methods

Phase-contrast images were acquired using a BZ-9000E

fluorescence microscope (Keyence, Osaka, Japan). Western blotting

was performed as described previously (26).

Results

ALDH activity and ALDH isoforms

expression are consistently induced in spheres of different

neuroblastoma cells

To begin to characterize ALDH in neuroblastoma,

NBTT2D, NBTT1 and NBTT3 cells established from distinct high-risk

neuroblastoma patients were grown as spheres in a serum-free

non-adherent condition as described previously (24). The ALDH activities in spheres and

parental cells were then determined by Aldefluor assay. Higher ALDH

activity was constantly detected in spheres compared to parental

cells (Fig. 1A and B). Because the

ALDH isoform responsible for high ALDH activity measured by

Aldefluor assay is specific for each cancer type (18), we next analyzed the fold-change of

ALDH isoform expression in spheres compared to parental cells.

Among all 19 ALDH isoforms expressed in human cells, ALDH1A2,

ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 expression was consistently induced in spheres

compared to parental cells (Fig.

1C). While the induction of ALDH1A2 expression was not so high

in NBTT1 and NBTT3 cells, ALDH1A2 showed the best correlation

between mRNA induction and enzymatic activity induction among

ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 isoforms.

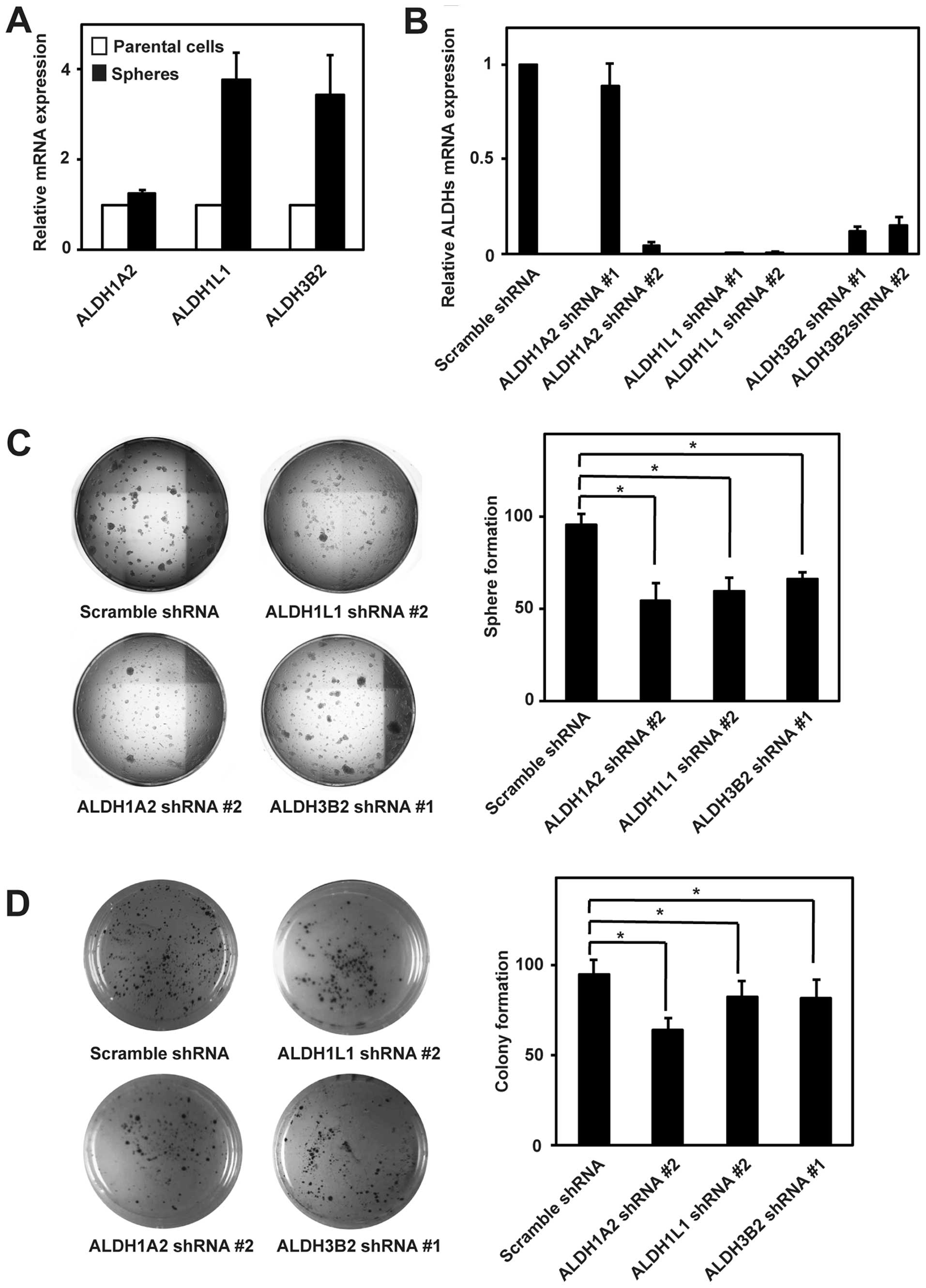

ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 isoforms are

associated with the sphere and colony formation in neuroblastoma

cells

To gain insight into the function of ALDH isoforms

induced in spheres, we first examined ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2

mRNA expression in spheres and parental cells of neuroblastoma

BE(2)-C cells. Like NBTT2D, NBTT1 and NBTT3 cells, BE(2)-C cells

also showed the induction of expression of these ALDH isoforms in

spheres (Fig. 2A). We then

generated BE(2)-C cells stably expressing scramble, ALDH1A2,

ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 shRNA. ALDH1A2 shRNA #2, ALDH1L1 shRNA #2 and

ALDH3B2 shRNA #1 achieved effective knockdown and were used in the

present study (Fig. 2B). Next, we

performed the sphere and colony formation assays that are widely

used to examine the CSC properties in vitro. In the sphere

formation assay, cells are cultured in a serum-free non-adherent

condition so that only cells with ability to self-renew will form

spheres. Knockdown of ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 in BE(2)-C cells

significantly impaired the sphere formation (Fig. 2C). In the colony formation assay,

cells with a capacity of anchorage-independent growth can grow in

soft agar and form colonies. The colony formation was also

significantly impaired upon ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 knockdown

(Fig. 2D). Among these ALDH

isoforms, ALDH1A2 knockdown showed the most profound effect on both

the sphere and colony formation.

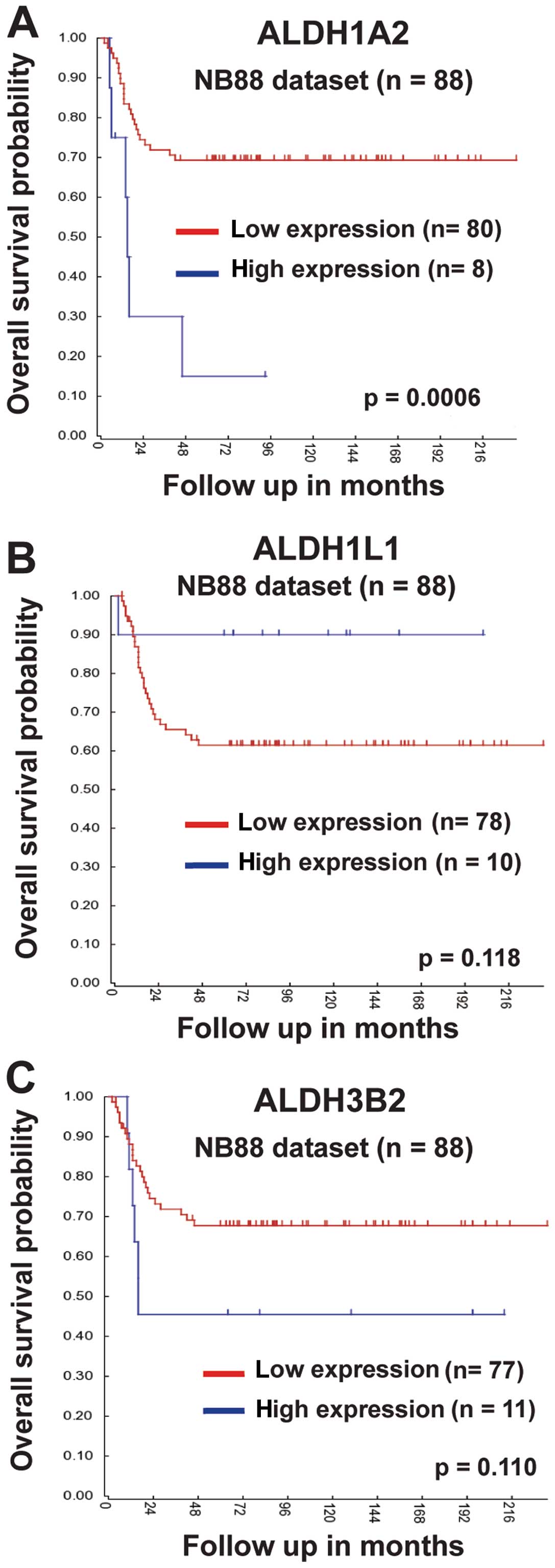

ALDH1A2 expression is correlated with the

prognosis of neuroblastoma patients

To further characterize the function of ALDH

isoforms induced in spheres, we next analyzed the correlation of

ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 expression with overall survival

probabilities of neuroblastoma patients. For this purpose, we used

the bioinformatics program R2 (http://r2.amc.nl)

and the NB88 dataset (Tumor

Neuroblastoma-Versteeg-88-MAS5.0-u133p2) that consisted of 88

primary neuroblastoma tumors of all stages. High expression of both

ALDH1A2 and ALDH3B2 was associated with low overall survival

probabilities (Fig. 3A and C). In

contrast, low ALDH1L1 expression tended to have low overall

survival probabilities (Fig. 3B).

Among ALDH1A2, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 isoforms, only ALDH1A2

expression was significantly correlated with overall survival

probabilities.

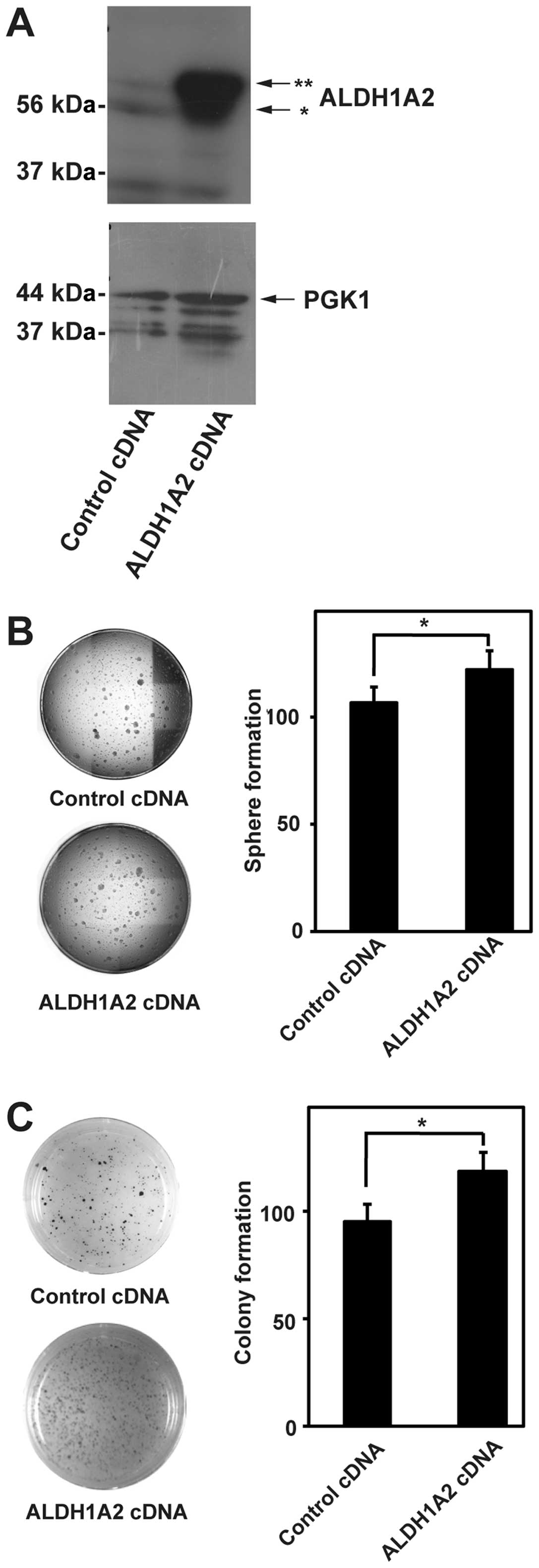

ALDH1A2 is involved in the sphere and

colony formation in neuroblastoma cells

Based on the above results, we focused on ALDH1A2

isoform in the subsequent study. If ALDH1A2 were involved in the

sphere and colony formation in neuroblastoma cells, ALDH1A2

overexpression would promote the sphere and colony formation. To

test this possibility, we generated BE(2)-C cells stably expressing

ALDH1A2 cDNA. ALDH1A2 overexpression was detected by western

blotting (Fig. 4A). The sphere and

colony formation were significantly promoted by ALDH1A2 cDNA

expression (Fig. 4B and C). These

results suggested that ALDH1A2 was involved in the sphere and

colony formation in neuroblastoma cells.

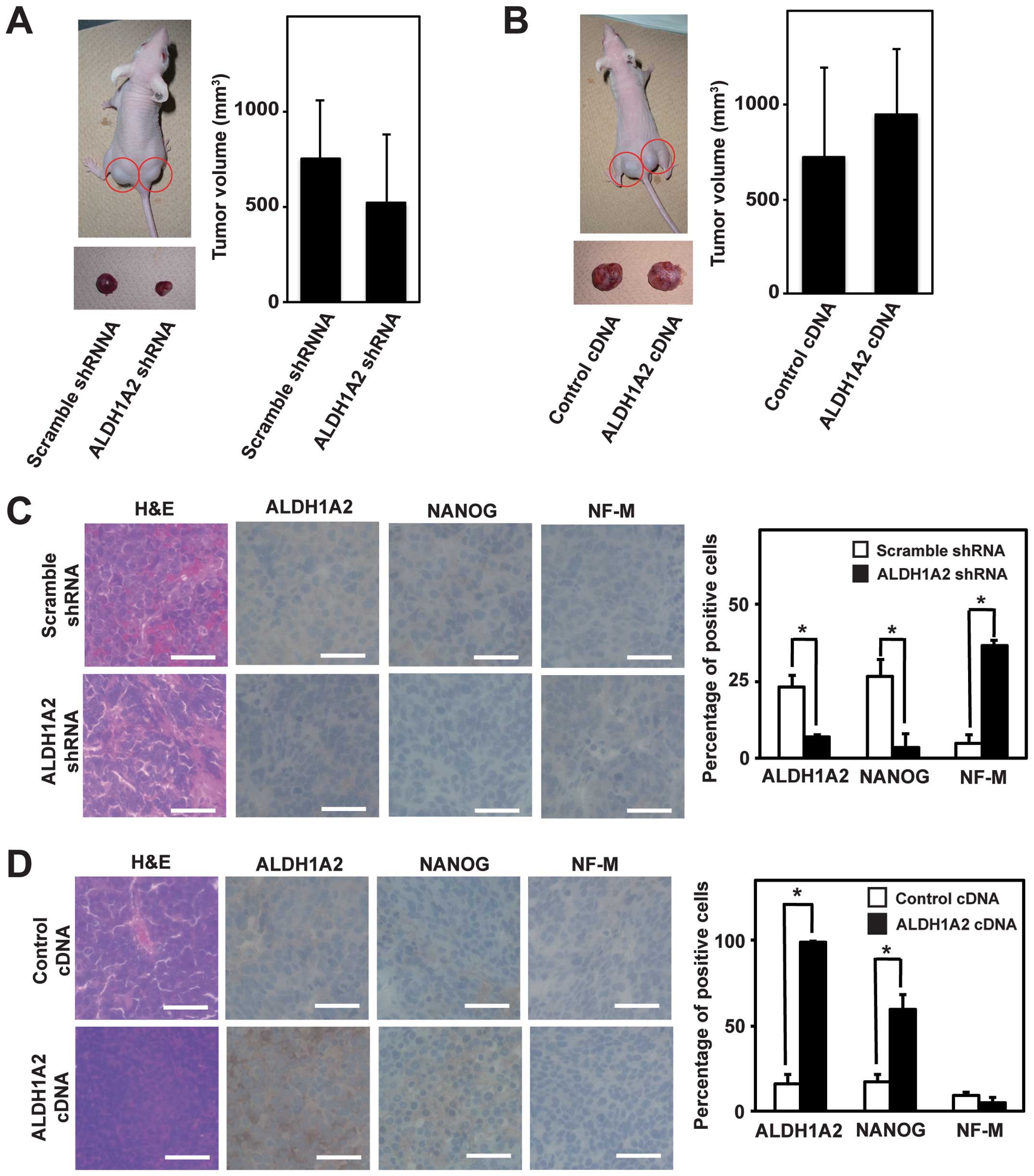

ALDH1A2 is involved in the growth and

undifferentiation of neuroblastoma xenografts

As CSC is defined as a subpopulation of cancer cells

that recapitulates their heterogeneous populations in xenograft

tumors, we next examined the function of ALDH1A2 in xenograft

tumors. To this end, we injected BE(2)-C cells stably expressing

scramble shRNA, ALDH1A2 shRNA, control cDNA and ALDH1A2 cDNA into

the flank of nude mice. All mice developed palpable tumors within

10–15 days and tumor volume was determined in 3–4 weeks. Tumor

volume tended to decrease upon ALDH1A2 knockdown and to increase

upon ALDH1A2 overexpression, albeit it was not statistically

significant (Fig. 5A and B). We

then performed the pathological examination with H&E staining.

Scramble shRNA and control cDNA tumors showed typical

characteristics of a small round cell tumor (Fig. 5C and D). Compared to scramble shRNA

tumors, ALDH1A2 shRNA tumors contained more stromal structures and

neuronal fibers (Fig. 5C,

H&E). In contrast, stromal structures were scarcer in

ALDH1A2 cDNA tumors than in control cDNA tumors (Fig. 5D, H&E). The tumors were further

examined by immunostaining with antibodies against ALDH1A2, NANOG

and NF-M. ALDH1A2-positive cells were reduced in ALDH1A2 shRNA

tumors compared to scramble shRNA tumors, whereas they were

increased in ALDH1A2 cDNA tumors compared to control cDNA tumors

(Fig. 5C and D, ALDH1A2). ALDH1A2

shRNA tumors showed more differentiated phenotypes with

NF-M-positive and NANOG-negative cells than scramble shRNA tumors,

while ALDH1A2 cDNA tumors had more undifferentiated phenotypes with

NANOG-positive and NF-M-negative cells than control cDNA tumors

(Fig. 5C and D, NANOG and NF-M).

These data suggested that ALDH1A2 was involved in the growth and

undifferentiation of neuroblastoma xenografts.

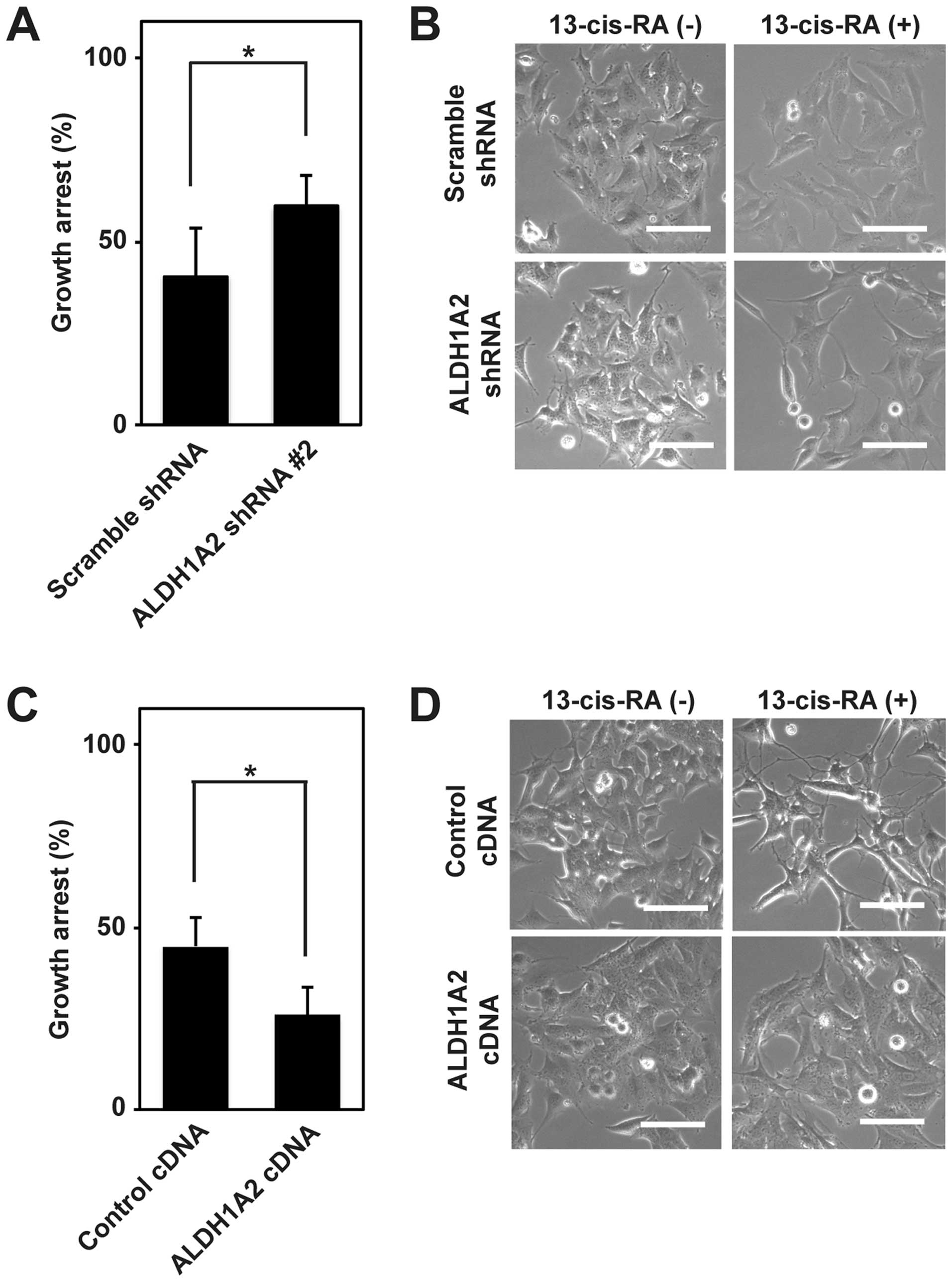

ALDH1A2 is involved in the resistance of

neuroblastoma cells to 13-cis-RA

Because CSC contributed to the chemoresistance in

addition to the sphere, colony and tumor formation, we finally

examined the function of ALDH1A2 in the resistance of neuroblastoma

cells to 13-cis-RA, which is currently used in the maintenance

therapy for high-risk neuroblastoma patients. As RA generally

induces the growth arrest and differentiation of neuroblastoma

cells, we first analyzed the growth arrest induced by 13-cis-RA

treatment for 72 h in BE(2)-C cells expressing scramble shRNA,

ALDH1A2 shRNA, control cDNA and ALDH1A2 cDNA. The 13-cis-RA-induced

growth arrest was significantly promoted by ALDH1A2 knockdown and

inhibited by ALDH1A2 overexpression (Fig. 6A and C). We then investigated their

differentiation by phase-contrast microscopy. In scramble shRNA and

control cDNA cells, the elongation of neurites started at ~48 h and

became evident at ~72 h after 13-cis-RA treatment. Compared to

scramble shRNA cells, ALDH1A2 shRNA cells showed more elongated

neurites at 48 h after 13-cis-RA treatment (Fig. 6B). In contrast, ALDH1A2 cDNA cells

did not elongate the neurites compared to control cDNA cells at 72

h after 13-cis-RA treatment (Fig.

6D). These results suggested that ALDH1A2 was involved in the

resistance of neuroblastoma cells to 13-cis-RA.

Discussion

More than half of high-risk neuroblastoma patients

experience tumor relapses and no curative salvage therapies for

recurrent neuroblastoma are currently known (4). In the present study, we analyzed ALDH

activity and expression of its 19 isoforms in spheres and parental

cells of different neuroblastoma cells. Consistent with our present

finding that ALDH1A2 was involved in the regulation of CSC

properties in neuroblastoma, ALDH1A2 was recently identified as the

highest upregulated gene along with marker genes of CD133, ABC

transporter, and WNT and NOTCH in neuroblastoma spheres (27).

While ALDH1A2 likely has diverse catalytic and

non-catalytic activities in addition to aldehyde metabolizing

activity, the physiological role of ALDH1A2 is best exemplified by

the association of genetic aberrations with disease phenotypes in

both mice and humans. ALDH1A2 knockout mice are embryonic lethal

(28), and mutations in ALDH1A2

gene are associated with spina bifida, congenital heart disease and

osteoarthritis of the hand (29–31).

As ALDH1A2 has the RA-biosynthesis activity by oxidizing retinal

aldehyde to RA, these phenotypes might be explained by the aberrant

RA-mediated cell signaling that has complex and pleiotropic

functions during development (32,33).

Among all 19 ALDH isoforms, other isoforms lacking

RA-biosynthesis activities were also upregulated in CSCs of several

cancer types (20,21,34).

Indeed, ALDH1L1 and ALDH3B2 expression was also consistently

induced in CSCs of neuroblastoma. The relation of ALDH1A2 to

ALDH1L1 and/or ALDH3B2 in neuroblastoma is currently under

investigation.

In addition to ALDH1A2, ALDH1A1, ALDH1A3 and ALDH8A1

can function in RA-signaling by their RA-biosynthesis activities

(18). Although these ALDH

isoforms were all expected to augment RA-signaling, their actual

roles were likely dependent on the cellular contexts of particular

cancer types. For instance, ALDH1A2 was downregulated and proposed

as a candidate tumor suppressor in prostate cancer (35,36),

whereas ALDH1A3 was upregulated and implicated in the maintenance

of CSCs in malignant high-grade gliomas (37).

In neuroblastoma, RA typically induces the

differentiation of tumor cells and 13-cis-RA is incorporated into

the maintenance therapy for high-risk patients with the purpose of

differentiating chemoresistant CSCs (3). However, the response to 13-cis-RA is

variable and still unpredictable in the clinic. Our present study

adds ALDH1A2 to a growing list of molecules responsible for

RA-resistance (38,39) and will provide a possible

therapeutic target.

In conclusion, we revealed that ALDH1A2 was involved

in the regulation of CSC properties in neuroblastoma. Inhibition of

ALDH1A2 deserves further evaluation as a new therapeutic approach

against high-risk neuroblastoma.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of animal facilities at Kobe

University Graduate School of Medicine and of Advanced Tissue

Staining Center at Kobe University Hospital for excellent technical

assistance. This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for

Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and grants from the

Children’s Cancer Association of Japan and Hyogo Science and

Technology Association.

References

|

1

|

Brodeur GM: Neuroblastoma: biological

insights into a clinical enigma. Nat Rev Cancer. 3:203–216. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Laverdière C, Liu Q, Yasui Y, et al:

Long-term outcomes in survivors of neuroblastoma: a report from the

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 101:1131–1140.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Maris JM: Recent advances in

neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 362:2202–2211. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Cole KA and Maris JM: New strategies in

refractory and recurrent neuroblastoma: translational opportunities

to impact patient outcome. Clin Cancer Res. 18:2423–2428. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Matthay KK, Villablanca JG, Seeger RC, et

al: Treatment of high-risk neuroblastoma with intensive

chemotherapy, radiotherapy, autologous bone marrow transplantation,

and 13-cis-retinoic acid. Children’s Cancer Group. N Engl J Med.

341:1165–1173. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yu AL, Gilman AL, Ozkaynak MF, et al:

Anti-GD2 antibody with GM-CSF, interleukin-2, and isotretinoin for

neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 363:1324–1334. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Visvader JE and Lindeman GJ: Cancer stem

cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved

questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 8:755–768. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Vermeulen L, de Sousa e Melo F, Richel DJ

and Medema JP: The developing cancer stem-cell model: clinical

challenges and opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 13:e83–e89. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Cheung N-KV and Dyer MA: Neuroblastoma:

developmental biology, cancer genomics and immunotherapy. Nat Rev

Cancer. 13:397–411. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Hansford LM, McKee AE, Zhang L, et al:

Neuroblastoma cells isolated from bone marrow metastases contain a

naturally enriched tumor-initiating cell. Cancer Res.

67:11234–11243. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, et

al: A distinct ‘side population’ of cells with high drug efflux

capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

101:14228–14233. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Takenobu H, Shimozato O, Nakamura T, et

al: CD133 suppresses neuroblastoma cell differentiation via signal

pathway modification. Oncogene. 30:97–105. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hsu DM, Agarwal S, Benham A, et al: G-CSF

receptor positive neuroblastoma subpopulations are enriched in

chemotherapy-resistant or relapsed tumors and are highly

tumorigenic. Cancer Res. 73:4134–4146. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Sartelet H, Imbriglio T, Nyalendo C, et

al: CD133 expression is associated with poor outcome in

neuroblastoma via chemo-resistance mediated by the AKT pathway.

Histopathology. 60:1144–1155. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Jackson B, Brocker C, Thompson DC, et al:

Update on the aldehyde dehydrogenase gene (ALDH) superfamily. Hum

Genomics. 5:283–303. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kastan MB, Schlaffer E, Russo JE, Colvin

OM, Civin CI and Hilton J: Direct demonstration of elevated

aldehyde dehydrogenase in human hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Blood. 75:1947–1950. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Ma I and Allan AL: The role of human

aldehyde dehydrogenase in normal and cancer stem cells. Stem Cell

Rev. 7:292–306. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Marcato P, Dean CA, Giacomantonio CA and

Lee PWK: Aldehyde dehydrogenase: its role as a cancer stem cell

marker comes down to the specific isoform. Cell Cycle.

10:1378–1384. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Sullivan JP, Spinola M, Dodge M, et al:

Aldehyde dehydrogenase activity selects for lung adenocarcinoma

stem cells dependent on notch signaling. Cancer Res. 70:9937–9948.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen Y, Orlicky DJ, Matsumoto A, Singh S,

Thompson DC and Vasiliou V: Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1B1 (ALDH1B1) is

a potential biomarker for human colon cancer. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 405:173–179. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

van den Hoogen C, van der Horst G, Cheung

H, et al: High aldehyde dehydrogenase activity identifies

tumor-initiating and metastasis-initiating cells in human prostate

cancer. Cancer Res. 70:5163–5173. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nishimura N, Pham TVH, Hartomo TB, et al:

Rab15 expression correlates with retinoic acid-induced

differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Oncol Rep. 26:145–151.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Pham TVH, Hartomo TB, Lee MJ, et al: Rab15

alternative splicing is altered in spheres of neuroblastoma cells.

Oncol Rep. 27:2045–2049. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nishimura N, Hartomo TB, Pham TVH, et al:

Epigallocatechin gallate inhibits sphere formation of neuroblastoma

BE(2)-C cells. Environ Health Prev Med. 17:246–251. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

25

|

Tomayko MM and Reynolds CP: Determination

of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 24:148–154. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kanda I, Nishimura N, Nakatsuji H,

Yamamura R, Nakanishi H and Sasaki T: Involvement of Rab13 and

JRAB/MICAL-L2 in epithelial cell scattering. Oncogene.

27:1687–1695. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Coulon A, Flahaut M, Mühlethaler-Mottet A,

et al: Functional sphere profiling reveals the complexity of

neuroblastoma tumor-initiating cell model. Neoplasia. 13:991–1004.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Niederreither K, Subbarayan V, Dollé P and

Chambon P: Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for early

mouse post-implantation development. Nat Genet. 21:444–448. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Deak KL, Dickerson ME, Linney E, et al:

Analysis of ALDH1A2, CYP26A1, CYP26B1, CRABP1, and CRABP2 in human

neural tube defects suggests a possible association with alleles in

ALDH1A2. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 73:868–875. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Pavan M, Ruiz VF, Silva FA, et al: ALDH1A2

(RALDH2) genetic variation in human congenital heart disease. BMC

Med Genet. 10:1132009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Styrkarsdottir U, Thorleifsson G,

Helgadottir HT, et al: Severe osteoarthritis of the hand associates

with common variants within the ALDH1A2 gene and with rare variants

at 1p31. Nat Genet. 46:498–502. 2014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Duester G: Retinoic acid synthesis and

signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 134:921–931. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Niederreither K and Dollé P: Retinoic acid

in development: towards an integrated view. Nat Rev Genet.

9:541–553. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Patel M, Lu L, Zander DS, Sreerama L, Coco

D and Moreb JS: ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1 expression in lung cancers:

correlation with histologic type and potential precursors. Lung

Cancer. 59:340–349. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kim H, Lapointe J, Kaygusuz G, et al: The

retinoic acid synthesis gene ALDH1a2 is a candidate tumor

suppressor in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 65:8118–8124. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Touma SE, Perner S, Rubin MA, Nanus DM and

Gudas LJ: Retinoid metabolism and ALDH1A2 (RALDH2) expression are

altered in the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate model.

Biochem Pharmacol. 78:1127–1138. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Mao P, Joshi K, Li J, et al: Mesenchymal

glioma stem cells are maintained by activated glycolytic metabolism

involving aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

110:8644–8649. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Huang S, Laoukili J, Epping MT, et al:

ZNF423 is critically required for retinoic acid-induced

differentiation and is a marker of neuroblastoma outcome. Cancer

Cell. 15:328–340. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Hölzel M, Huang S, Koster J, et al: NF1 is

a tumor suppressor in neuroblastoma that determines retinoic acid

response and disease outcome. Cell. 142:218–229. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|