Introduction

The growth and metastatic spread of malignant tumors

cannot proceed without the development of a vascular supply.

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) plays a key role in

tumor angiogenesis (1–4). The significant amount of VEGFR

expression in the tumor vasculature presents a unique opportunity

for therapeutic intervention. VEGF and its receptor VEGFR-1/VEGFR-2

provide an alternative approach for destroying tumor endothelium

through targeting in combination with agents that kill cells,

making them targets for the delivery of potent toxins to tumor

endothelial cells (5,6). VEGF mRNA is alternatively spliced,

leading to proteins that are 208, 189, 165, or 121 amino acids in

length (7). VEGF165 and

VEGF121 are secreted as soluble factors; however,

VEGF208 and VEGF189 are secreted while

binding to the extracellular matrix (8). Compared with VEGF121,

VEGF165 retains a heparin-binding domain, which induces

binding to the cell surface receptor. Furthermore,

VEGF165 is the most abundantly expressed splice variant

(9). In the present study, we

chose melittin for fusion with VEGF. This fusion protein, denoted

as VEGFR165-melittin, was shown to potently inhibit

hepatocellular carcinoma and pancreatic cancer in vivo and

in vitro.

Melittin is the principal toxic component in venom

from the European honey bee Apis mellifera. This protein is

a cationic, hemolytic and small linear peptide composed of 26 amino

acid residues. Notably, the N-terminus is predominantly hydrophobic

and the C-terminus is hydrophilic. Melittin has various effects,

including antibacterial, antiviral, and anti-inflammatory effects,

in various cell types (10). It

has been reported that melittin can induce apoptosis, cell cycle

arrest and growth-inhibition in different tumor cells (11–13).

However, the significant toxicity of melittin is achieved through a

highly non-specific cytolytic attack of lipid membranes (14). The principle of the melittin

toxicity is its physical and chemical destruction of cellular

membranes, leading to a profound increase in the cell permeability

barrier and leakage of cell contents (15,16),

thereby precluding any meaningful therapeutic benefit. An

alternative approach for achieving practical therapeutic

applications would be designing a new paradigm for the targeted

delivery of potent toxins to tumor cells. Moreover, it has been

reported that melittin suppresses tumor growth by targeting VEGF

(17,18). Therefore, melittin as a fusion

partner should work well with VEGF.

In the present study, we prepared a novel fusion

protein, VEGF165-melittin, in Pichia pastoris. We

generated an effective method for producing the recombinant protein

in large quantities with high purity. Our results demonstrate that

VEGF165-melittin retains functional activities including

cytotoxicity and growth inhibition in HepG-2 and MHCC97-H human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells in vitro. Furthermore, the

fusion toxin was able to inhibit tumor growth in vivo. This

fusion protein has the potential to be used as a new paradigm for

the targeted delivery of cell-penetrating toxins to kill cancer

cells in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Reagents and materials

Pichia pastoris X-33, the pPICZαC vector, and

Zeocin antibiotic were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA,

USA). Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, DNA marker, and the

pMD-18T vector were purchased from Takara (Dalian, China). The

protein marker was purchased from Thermo Fermentas and New England

Biolabs (Guangzhou, China). All primers were synthesized by

Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Corp. (Shanghai, China).

Anti-VEGF165, anti-VEGFR-1, anti-VEGFR-2, anti-melittin,

HRP-goat anti-rabbit conjugate and HRP-goat anti-mouse conjugate

were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Melittin was purchased from Nanning Innovation and Technology

Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Guangxi, China). Anti-VEGF blocking

antibody was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

VEGFR-2/KDR gene was purchased from Sino Biological Inc. (Beijing,

China).

Human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (HepG-2

and MHCC97-H), a human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line

(AsPC-1), and 293 human primary embryonic kidney cells were

obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. All the cells

were passaged according to their protocol from ATCC, and no more

than 6 months elapsed after the resuscitation and culturing of the

cells. Serum and culture medium were purchased from Invitrogen.

BALB/c mice and BALB/c nude mice (4–5 weeks) were obtained from the

Experimental Animal Research Centre of Zhongshan University and

raised in its laboratory. All animal protocols followed the

National Guidelines for the Care and Use of Animals.

Yeast culture media

Pichia pastoris was cultured in YPD medium

containing 10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone and 20 g/l

D-glucose. To prepare YPD plates, 2% agar (w/v) was added into YPD

medium. YPD-Zeocin plates containing 0.1 mg/ml Zeocin were used for

the selection of transformants. The Pichia pastoris cells

were grown in BMGY medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 1%

glycerol, 1.34% yeast nitrogen base and 0.1 M potassium phosphate,

pH 6.0) and BMMY medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.5%

methanol, 1.34% yeast nitrogen base and 0.1 M potassium phosphate,

pH 6.0) for induction.

Construction of expression vector

containing pPICZαC/VEGF165-melittin

A DNA insert encoding melittin was prepared via

artificial synthesis. A linker containing (GGGGS)4,

EcoRI, ApaI, AccI and XbaI sequences

were appended when the synthetic fragment was designed. Then, the

melittin DNA fragment was digested with EcoRI and

XbaI and ligated into a linearized pPICZαC vector to

generate the plasmid pPICZαC/melittin.

To clone the VEGF165 gene,

reverse-transcription poly-merase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was

performed with the primers 5′-ATT CTC GAG AAG AGA GCA CCC ATG GCA

GAA GGA G-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTA GAA TTC CCG CCT CGG CTT GTC ACA

TTT TTA-3′ (reverse), and total RNA extracted from human hepatoma

(HepG2) cells served as the template. Following digestion with

XhoI and EcoRI, the PCR fragment was cloned into

pPICZαC/melittin and treated with the same endonucleases to

generate the recombinant eukaryotic expression plasmid

pPICZαC/VEGF165-melittin. The recombinant plasmid was

confirmed by restriction analysis and sequencing.

Transformation and screening of

recombinant strains

Recombinant plasmid DNA was linearized with

SacI and then transformed into Pichia pastoris X-33

by electroporation using a MicroPulser (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Hercules, CA, USA) following the pPICZαC vector manual. The yeast

strains transformed with empty vector pPICZαC plasmid served as a

negative control. The cells were spread on YPD plates containing

Zeocin at 100, 250, 500 and 1,000 mg/ml and incubated at 28°C.

Colonies appeared after 2–3 days of incubation at 28°C. The

inserted foreign gene in the genomic DNA of transformants were

detected by PCR assay using the primers mentioned above. Thirty

cycles of PCR were performed with incubations for 30 sec at 94°C,

30 sec at 55°C and 1.5 min at 72°C.

Optimized expression of the fusion

protein in P. pastoris

To confirm the optimal expression conditions for the

fusion protein, various culture parameters, including induction

time-points and pH values (pH 3.0–7.0 with 0.5 pH intervals), were

evaluated. The processes were the same as above. At specific

intervals, 0.5 ml cell suspensions were removed and then

substituted with the same volume of fresh medium. The cell culture

supernatant was tested by ELISA assays.

Purification of

VEGF165-melittin

VEGF165-melittin production was scaled up

in 2 l BMGY medium based on the process introduced in the

Invitrogen manual (19).

Transformants were cultured at 28°C (pH 6.0) until the culture

reached OD600=2.0–6.0, the cells were harvested by

centrifugation, redissolved in 2 l BMMY medium, and cultured at

28°C with oscillation for 72 h. The fermentation broth was

supplemented every 24 h with 10 ml methanol to maintain the induced

control.

Fermentation supernatant was collected by filtration

(0.45 μm) after harvesting by centrifugation at 12,000 r/min for 15

min. A Ni2+ NTA column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ,

USA) was equilibrated in binding buffer (20 mM

Na3PO4·12 H2O, pH 7.4, 0.5 M NaCl

and 30 mM imidazole). The supernatant was diluted 3-fold with

binding buffer and loaded onto a Ni2+ NTA column at a

speed of 0.5 ml/min. Then, the column was washed with the same

buffer at a rate of 1.0 ml/min to eliminate unbound proteins. Bound

protein was then eluted from the column with 20 mM

Na3PO4·12 H2O, pH 7.4, 0.5 M NaCl

and 0.2 M imidazole at a rate of 0.8 ml/min. Eluted protein was

then transferred to storage buffer (1X PBS) by chromatography using

a Thermo Scientific Zeba desalting column (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Waltham, MA USA).

Protein assay

The protein concentrations of the samples were

measured using the Bradford assay with bovine serum albumin as a

standard.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Individual wells of ELISA plates (Costar) were

coated with fusion toxin sample supernatants and coating buffer

(Na2CO3-NaHCO3, pH 9.6, dilution:

2 μg/100 μl) overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with 2% BSA

in TPBS (PBS1, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.2) and incubated for

2 h at room temperature. The primary antibody against rabbit was

used at 1:1,000 and precoated for 2 h at 37°C. After several washes

with TPBS, the plates were incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG

conjugated to HRP (1:2,000 dilutions at blocking buffer) for 2 h.

The color reaction was implemented with OPD zymolyte containing

0.02% H2O2, and the plates were incubated for

15 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, 50 μl of

H2SO4 solution (2 M) was used to stop the

reaction. Absorbance values at 490 nm were read using an ELX800

microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

After adding stop solution, plate reads were completed within 2

h.

SDS-PAGE and western blot assays

Cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE in 10% gels

and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane

(Millipore) using a semi-dry electroblotting apparatus (Bio-Rad

Laboratories) at 200 mA for 1 h in Towbin transfer buffer (25 mM

Tris and 192 mm glycine). The membrane was blocked with 2% BSA for

1.5 h at room temperature. Then, the membrane was incubated with

primary antibodies against rabbit for 12 h. After washing, the

membrane was incubated with a goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody

conjugated to HRP (Weijia, Shaanxi, China) that was diluted 1:250.

The bound antibody was developed with 3,30-diaminobenzidine

(DAB).

N-terminal amino acid sequence and mass

spectrometric analyses

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of the

VEGF165-melittin fusion protein was determined by

automated Edman degradation, which was performed with a model

protein sequencer-491 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

The purified protein was adsorbed onto a PVDF membrane (ProSorb)

and sequenced using established protocols. Mass spectrometric

analysis of VEGF165-melittin was performed with an

autoflex speed MALDI-TOF/TOF MS (Brucker Daltonics, Billerica, MA,

USA).

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction

Total cellular RNA was extracted from cell cultures

using the RNAiso reagent (Takara, Tokyo, Japan) according to the

manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration was detected using a

BioPhotometer (Eppendorf Scientific, Hamburg, Germany). Reverse

transcription of total RNA primed with an oligo(dT) oligonucleotide

was done with M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega, Mannheim,

Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

First-strand complementary DNA was amplified using Takara Ex Taq

(Takara).

The primers for the respective genes were designed

as follows: VEGF, 5′-GCA CCC ATG GCA GAA GGA-3′ (forward) and

5′-TTC TGT ATC AGT CTT TCC-3′ (reverse); VEGFR-1, 5′-GAA GGC ATG

AGG ATG AGA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAG GCT CAT GAA CTT GAA-3′

(reverse); KDR/VEGFR-2, 5′-CAT GTA CGG TCT ATG CCA-3′ (forward) and

5′-CGT TGG CGC ACT CTT CCT-3′ (reverse); and β-actin, 5′-TTC CTG

GGC ATG GAG TCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGC CTA GAA GCA TTT GCG-3′

(reverse). RT-PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis on a 1%

agarose gel.

Cytotoxicity assay

Cells were seeded in 96-well plates at

5–10×104 cells/well. Cells were then starved with phenol

red-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium plus 1% dialyzed fetal

calf serum (A15-107; PAA Laboratories, Dartmouth, MA, USA) for 24

h. The experiment included six VEGF165-melittin fusion

protein groups (0, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4 and 12.8 μg/ml). Human

primary embryonic kidney cells (n=293) were used for control. Cell

growth was induced by the fusion toxin for 48 h and then measured

with the MTT assay. Absorbance at 570 nm was detected with a

reference at 630 nm serving as a blank. The influence of the fusion

toxin on cell activity was evaluated and compared with control. The

control cells were set to 100% activity. The mean value of 5 wells

was counted, and triplicates were used in each experiment.

To test VEGFR-mediated effects of

VEGF165-melittin fusion protein on the proliferation and

viability of human cancer cells, HepG-2 cells was used for

subsequent studies. HepG-2 cells were cultured as described above.

Five experimental groups were designed and HepG-2 untreated was the

control group.

Inhibitory effects of

VEGF165-melittin on hepatocellular carcinoma and

pancreatic cancer xenografts in nude mice

After hypodermic injection of 2.5×107

HepG-2 or 5×106 AsPC-1 cells in BALB/c athymic nude

mice, initial tumors were observed on day 21. Afterward, all mice

in the experimental groups were intravenously injected with 0.2 mg

VEGF165-melittin daily for 28 days, and PBS was used as

a control. The subcutaneous tumor parameters were measured every

day, including the length, width and height. The tumor volume

(mm3) was estimated according to the equation

a2b/2, where a is the short diameter (mm) and b is the

long diameter (mm). The tumor weights were measured after the mice

were sacrificed. The tumor samples were maintained in formalin, and

an assessment of mortality was performed.

Results

VEGF165-melittin expression

and optimization

A plasmid was created to express the

VEGF165 fragment fused to melittin to generate a 25 kD

VEGF165-melittin fusion toxin. The structure of the

details of VEGF165-melittin is shown in Fig. 1A. pPICZαC/melittin is based on the

Pichia pastoris expression vector pPICZαC. This vector was

used to express the VEGF165-melittin fusion protein,

which is composed of the melittin fragment cut from the ApaI

and XbaI sites following the VEGF165 fragment. A

linker, (GGGGS)4, was synthesized for spatial

configuration of the fusion toxin. The VEGF165 sequence

was amplified and inserted into the pPICZαC/melittin expression

vector to create pPICZαC/VEGF165-melittin. Sequence

analysis of the plasmid DNA was used to confirm integration in

positive colonies.

After electroporation with SacI-linearized

pPICZαC/VEGF165-melittin, 90% of transformants were

Mut+. PCR analysis of genomic DNA demonstrated that the

gene of interest was integrated into the stable transformants, and

no similar bands were observed for negative control samples.

The positive transformants were germinated in BMGY

medium and induced in BMMY medium at 28°C for 7 days. The volume of

the culture medium was 10 ml. After 3 days, the culture

supernatants were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The results indicated that

the molecular weight of VEGF165-melittin was consistent

with the predicted size of 25 kDa (Fig. 1B).

Transformants expressing a high level of fusion

protein were selected, and one was chosen for the scaling up. Based

on analysis of optimized expression conditions, the parameters used

were as follows: pH: 6.0, induction time-point: 72 h, and final

methanol concentration: 0.5% (v/v) (Fig. 1C and D).

VEGF165-melittin fermentation

and purification

VEGF165-melittin supernatant was purified

by Ni2+ affinity chromatography and Thermo Scientific

Zeba desalting column chromatography. Following these processes,

~160 mg pure recombinant protein was obtained from 2 l fermentation

liquor. SDS-PAGE analysis demonstrated that the purity of

VEGF165-melittin was ~95% (Fig. 2A). At every step of purification,

the recovery, purity and yield of the fusion toxin were estimated

as shown in Table I.

| Table ISummary of purification process of

VEGF165-melittin from 2 liters of culture supernatant

purification. |

Table I

Summary of purification process of

VEGF165-melittin from 2 liters of culture supernatant

purification.

| Purification

steps | Total protein

(mg/l) |

VEGF165-melittin (mg/l) | Purity (%) | Recovery (%) |

|---|

| Supernatants | 256.5 | 154.2 | 60.1 | |

|

Ni2+-NTA | 121.1 | 115.3 | 95.2 | 74.8 |

| Desalting

column | 84.3 | 80.3 | 95.3 | 52.1 |

Western blot assays were used to preliminarily

evaluate the purified recombinant protein. The identity of

VEGF165-melittin was confirmed by immunoreactivity with

a rabbit anti-human VEGF165 polyclonal antibody

(Fig. 2B). The results were

consistent with our expectations. No band was observed in lane 1,

which contains the supernatant of the X33 pPICZαC transformant.

Molecular weight and N-terminal

sequencing analyses

To verify the molecular weight and integrity of the

recombinant protein, mass spectrometry was performed using purified

VEGF165-melittin. The expected molecular mass

VEGF165-melittin is 221 amino acids, and it primarily

exists in solution as a homodimer due to a disulfide linkage in the

linker. The results of the molecular weight analysis of the fusion

toxin are shown in Fig. 3, and

they are in accordance with our previous results, indicating that

the purified recombinant toxin is the expected

VEGF165-melittin protein.

According to N-terminal sequencing analysis, the

first 15 amino acids of the purified peptide were A P M A E G G G Q

N H H E V V. These were consistent with the N-terminal sequence of

VEGF165-melittin, thus indicating successful expression

and purification of this protein.

Cytotoxicity assay

The effects of VEGF165-melittin on the

proliferation and viability of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell

lines (HepG-2 and MHCC97-H), human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell

lines AsPC-1 and human primary embryonic kidney cells 293 were

studied for a 72-h period. The fusion protein was applied to the

cells at seven different final concentrations. Fig. 4 shows the proliferation and

viability changes that occurred during treatment. Cell counts and

an MTT-assay indicated that the fusion toxin influenced the

proliferation of HepG-2 and MHCC97-H cells more significantly than

that of AsPC-1 cells. The proliferation of the HepG-2 cells

significantly decreased by 55% in an MTT assay (P<0.01).

However, an effect of the fusion toxin on the viability of 293

cells was not observed, even at the highest

VEGF165-melittin dose.

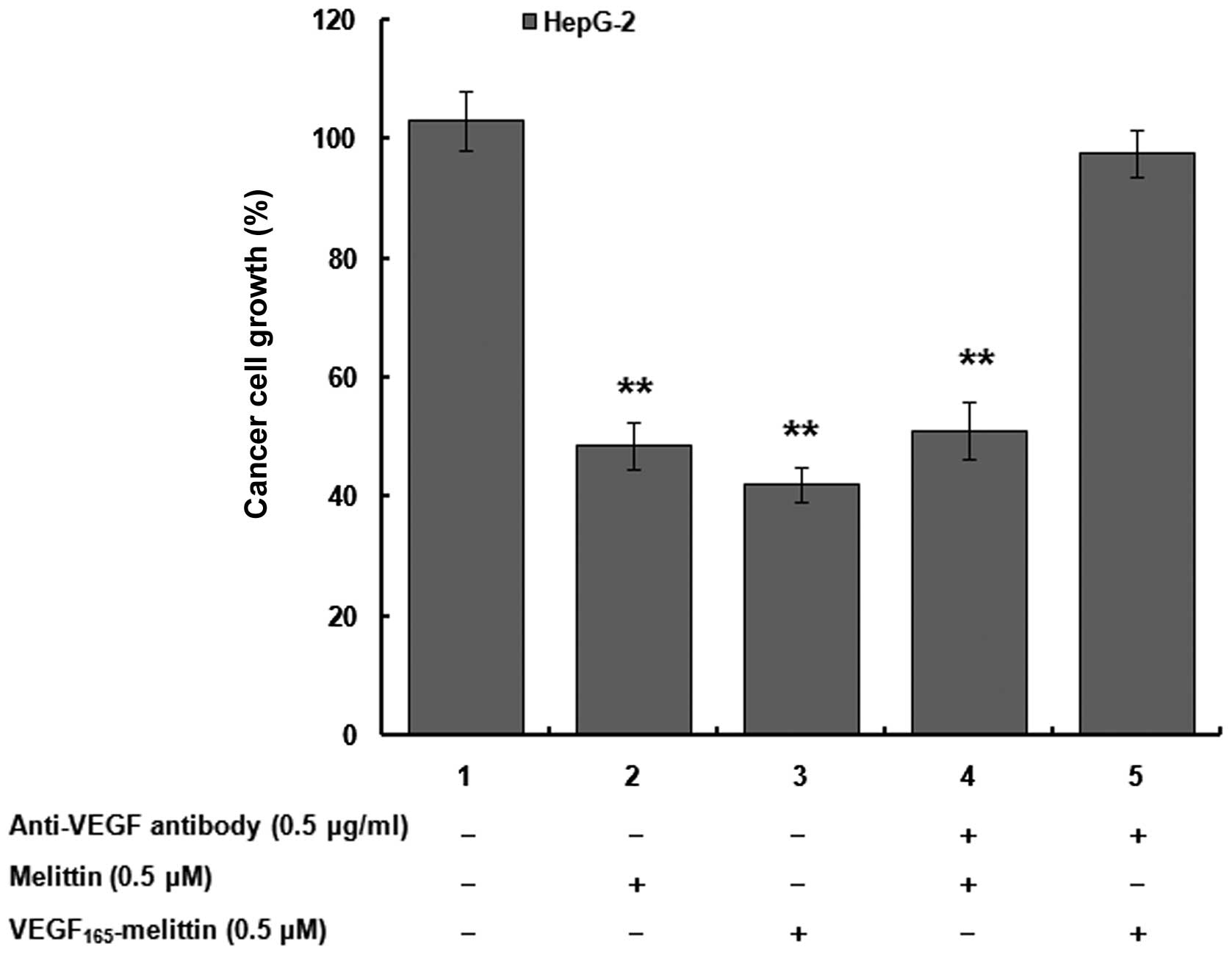

To further assess the mediation effects between

VEGF165-melittin and VEGFR inhibition, human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG-2 were incubated with

VEGF165-melittin or melittin for 48 h in the presence or

absence of 0.5 μg/ml anti-VEGF antibody. Fig. 5 shows the proliferation of the

HepG-2 cells significantly decreased when melittin or

VEGF165-melittin was added (P<0.01). However, in

VEGF165-melittin groups, the inhibitory activity was not

observed after incubated with the anti-VEGF antibody. This

sensitivity of HepG-2 might be mediated by VEGFR present on HepG-2

cells, since 293 cells without known VEGF receptors were not

affected by VEGF165-melittin at high concentrations

(Fig. 4). Presence of VEGFR

appears to be necessary for induction of HepG-2 cell death by

VEGF165-melittin.

VEGF165-melittin-mediated

tumor growth inhibition in vivo

In the HepG-2 xenograft nude mouse model, the

average tumor volume in VEGF165-melittin mice was 843

mm3, and it was 1,769 mm3 in control mice

(Fig. 6A). Therefore, the

inhibitory rate of the average tumor volume was 52.3%. Twenty-eight

days after treatment with the fusion toxin, the survival was 100%

for VEGF165-melittin mice and 60% for control mice

(Fig. 6B). In the AsPC-1 xenograft

nude mouse model, inhibition of the average tumor volume in the

experimental group was 34.4% as compared with the control group.

Significant VEGF165-melittin-mediated inhibition of

tumor growth was demonstrated. Based on these results, it was

obvious that there were stronger effects in HepG-2 compared with

AsPC-1 cells, which suggests that the high expression level of

VEGFR-2 in HepG-2 might mediate this influence.

Specific toxicity of

VEGF165-melittin targeting VEGFR-2

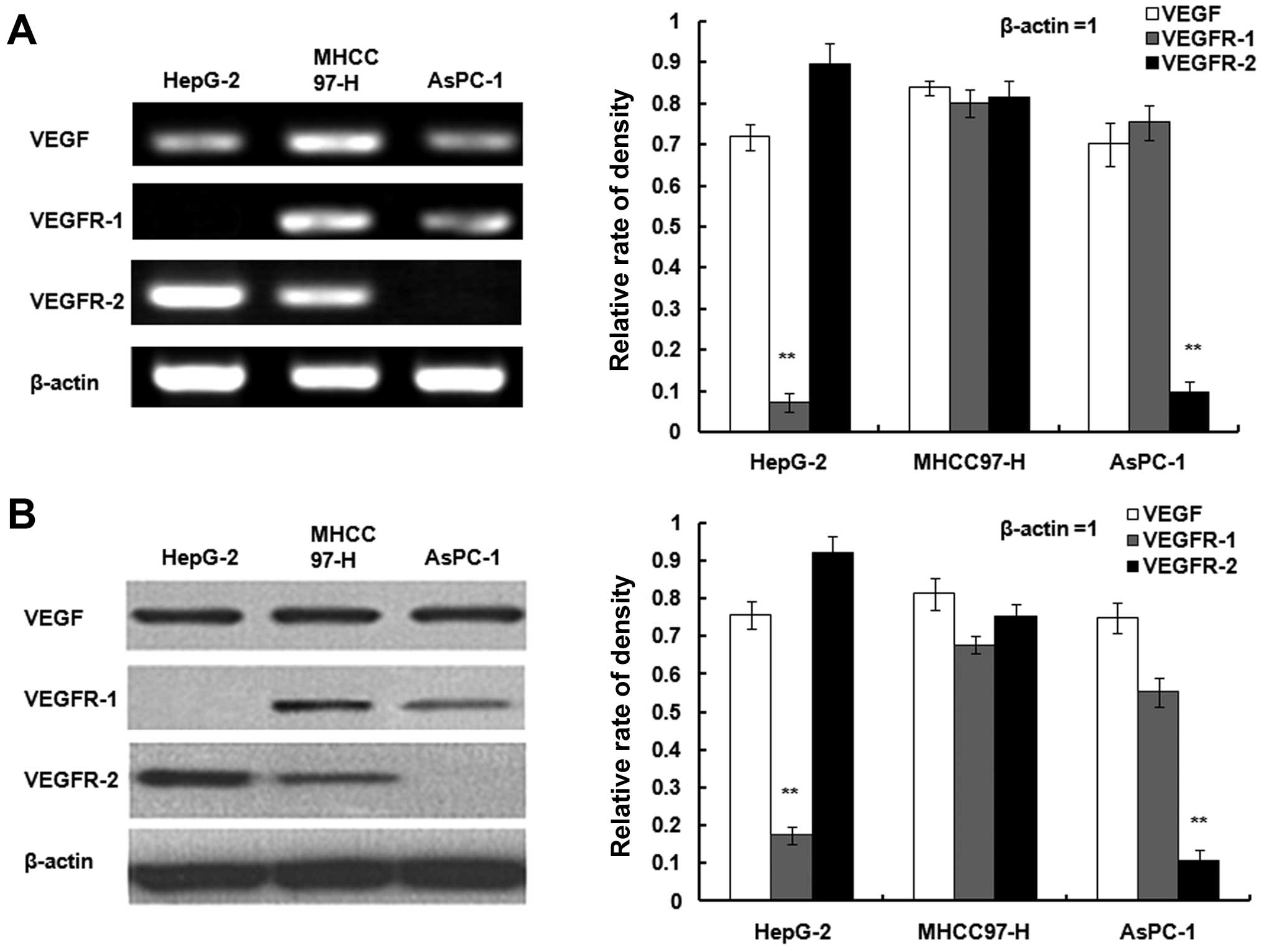

Expression of VEGF, VEGFR-1 and KDR/VEGFR-2 in

HepG-2 and MHCC97-H cells as well as AsPC-1 cells were determined

with RT-PCR and western blot assays (Fig. 7A and B). All three cell lines

exhibited VEGF. MHCC-97H cells were positive for VEGFR-1 and

KDR/VEGFR-2. KDR/VEGFR-2 was expressed in HepG-2 and VEGFR1 was

expressed in AsPC-1.

Furthermore, KDR/VEGFR-2 was overexpressed in 293

cells to evaluate the specific targeting of fusion protein

(Fig. 8A). The effect of

VEGF165-melittin on the proliferation and viability of

293 cells, 293 transfected with pCMVp-NEO-BAN/KDR plasmid (293/KDR)

and HepG-2 cells was studied. The 293 cells transfected with

pCMVp-NEO-BAN empty plasmid (293/pCMV) were used as control. In

targeted cells, the cytotoxicity of VEGF165-melittin was

strongly dependent on the VEGFR-2 density. Fig. 8B shows proliferation and viability

changes using the MTT assay.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 13.0 software. Data are

presented as the means ± SD. Statistical significance was

determined by one-way analysis of variance or the t-test. P-values

<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Discussion

It is well known that tumor cell-derived VEGF is a

key factor that acts on endothelial cells to promote angiogenesis,

tumor growth and metastasis. Targeting proangiogenic mediators such

as VEGF/VEGFR has emerged as a promising anti-cancer treatment

strategy. In particular, VEGF fusion proteins have become an

important aspect in novel cancer treatment strategies (20). In the present study, we constructed

a protein containing VEGF165 fused to melittin

(VEGF165-melittin). Successful expression of active

VEGF165-melittin was achieved in Pichia pastoris

with yields >80 mg/l. N-terminal sequencing and mass

spectrometric analysis verified that the fusion toxin was expressed

and purified as expected. MTT and xenografts assays demonstrated

that VEGF165-melittin inhibited tumor growth in

vivo and in vitro.

Among the identified proangiogenic regulators, VEGF,

particularly VEGF-A and its two tyrosine kinase receptors, fms-like

tyrosine kinase receptor (Flt1 and VEGFR-1) and kinase insert

domain-containing receptor (KDR/FLK1 and VEGFR-2), have been

identified as key mediators of the regulation of pathologic blood

vessel growth and maintenance (21). In our results,

VEGF165-melittin was more effective in HepG-2 than

MHCC97-H cells. This diversity may be caused by differences in the

VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 proteins expressed in HepG-2 and MHCC97-H

cells. In subsequent studies, the expression of VEGF and the VEGF

receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2) was evaluated in HepG-2 and

MHCC97-H cells by RT-PCR and western blot assays. Compared with the

results we reported here, the VEGF165-melittin fusion

toxin should be selective in targeting tumor cells that overexpress

VEGFR-2. We hypothesize that the enhanced efficacy of VEGF fusion

toxin may be due to the overexpression of VEGFR-2 in growing cells.

Subsequently, 293 human primary embryonic kidney cells (293/KDR)

overexpressing VEGFR-2 was constructed in our laboratory.

VEGF165-melittin inhibited growth of 293/KDR cells at a

dose of 6.4 μg/ml. These effects were mediated by VEGFR-2, since

the parental 293 cells lacking VEGFR-2 were not inhibited by fusion

protein.

Melittin is a main component of bee venom. It is a

small peptide with a linear structure composed of 26 amino acids

(22). Bee venom has a wide range

of effects including antibacterial, antiviral and anti-inflammatory

effects; thus, it has been extensively used in the field of

traditional medicine including treatments for back pain, rheumatism

and skin diseases (23,24). Furthermore, it has been shown that

bee venom and/or melittin have inhibitory effects on the tumor

growth of cervical, prostate, renal, breast, ovarian and liver

tumor cells (10,25,26).

The results of our research are in accordance with previous studies

demonstrating the suppression of melittin on the growth of human

hepatic carcinoma cell lines (11,27).

Additionally, the fusion toxin VEGF165-melittin

inhibited the proliferation of human hepatocellular carcinoma cell

lines (HepG-2 and MHCC97-H) in a concentration-dependent manner.

The most effective inhibitory concentration of

VEGF165-melittin was 6.4 μg/ml, resulting in an

inhibition ratio of 52.3%. The remarkable suppressive effects on

cell proliferation were observed after 48 h in the experimental

group. The present study indicated that the fusion toxin directly

inhibits the growth of hepG-2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells

in vitro and in vivo. In follow-up experiments, more

studies will be designed to detect the antitumor activity and

mechanism of this fusion protein.

As a lower eukaryote, Pichia pastoris was

identified as a suitable expression system for various recombinant

proteins that retains biological activity with high quantity

yields, and it also offers the benefits of E. coli

(cost-effective and easy scale-up). In addition, the advantages of

expression in a eukaryotic system include proper protein

processing, folding and post-translational modifications (28,29).

In addition, Pichia pastoris does not secrete large amounts

of intrinsic proteins, resulting in the easy isolation of foreign

proteins. In the present study, VEGF165-melittin

production was performed in a 2-liter fermentor, with yields >80

mg/l. The successful expression and purification of the recombinant

fusion toxin VEGF165-melittin and its activity in human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells demonstrates that the fusion protein

has the potential to be used as a novel cancer treatment strategy.

This is the first report to describe the secretory expression of a

human vascular endothelial growth factor fused to melittin in

Pichia pastoris.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the

Foundation for Distinguished Young Talents in Higher Education in

Guangdong, China (LYM11080), the National Nature Science Foundation

of China (No. 81101542) and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory

of Biotechnology Candidate Drug Research.

Abbreviations:

|

PBS

|

phosphate-buffered saline

|

|

OPD

|

ortho-phenyl-enediamine

|

|

DAB

|

3,3′-diaminobenzidine

|

|

BSA

|

bovine serum albumin

|

References

|

1

|

Carmeliet P and Jain RK: Angiogenesis in

cancer and other diseases. Nature. 407:249–257. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Zhu W, Kato Y and Artemov D: Heterogeneity

of tumor vasculature and antiangiogenic intervention: Insights from

MR angiography and DCE-MRI. PLoS One. 9:e865832014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ferrara N and Ferrara N: Vascular

endothelial growth factor: Molecular and biological aspects. Curr

Top Microbiol Immunol. 237:1–30. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hicklin DJ and Ellis LM: Role of the

vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in tumor growth and

angiogenesis. J Clin Oncol. 23:1011–1027. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang D, Li B, Shi J, Zhao L, Zhang X,

Wang C, Hou S, Qian W, Kou G, Wang H, et al: Suppression of tumor

growth and metastasis by simultaneously blocking vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A and VEGF-C with a

receptor-immunoglobulin fusion protein. Cancer Res. 70:2495–2503.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen AI and Advani RH: Beyond the

guidelines in the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: New drug

development. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 6:428–435. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tischer E, Mitchell R, Hartman T, Silva M,

Gospodarowicz D, Fiddes JC and Abraham JA: The human gene for

vascular endothelial growth factor. Multiple protein forms are

encoded through alternative exon splicing. J Biol Chem.

266:11947–11954. 1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Houck KA, Leung DW, Rowland AM, Winer J

and Ferrara N: Dual regulation of vascular endothelial growth

factor bioavailability by genetic and proteolytic mechanisms. J

Biol Chem. 267:26031–26037. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Koutsioumpa M, Poimenidi E, Pantazaka E,

Theodoropoulou C, Skoura A, Megalooikonomou V, Kieffer N, Courty J,

Mizumoto S, Sugahara K, et al: Receptor protein tyrosine

phosphatase beta/zeta is a functional binding partner for vascular

endothelial growth factor. Mol Cancer. 14:19–34. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Oršolić N: Bee venom in cancer therapy.

Cancer Metastasis Rev. 31:173–194. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Wang C, Chen T, Zhang N, Yang M, Li B, Lü

X, Cao X and Ling C: Melittin, a major component of bee venom,

sensitizes human hepatocellular carcinoma cells to tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-induced apoptosis

by activating CaMKII-TAK1-JNK/p38 and inhibiting IκBα kinase-NF-κB.

J Biol Chem. 284:3804–3813. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gajski G and Garaj-Vrhovac V: Melittin: A

lytic peptide with anti-cancer properties. Environ Toxicol

Pharmacol. 36:697–705. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Liu S, Yu M, He Y, Xiao L, Wang F, Song C,

Sun S, Ling C and Xu Z: Melittin prevents liver cancer cell

metastasis through inhibition of the Rac1-dependent pathway.

Hepatology. 47:1964–1973. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hoskin DW and Ramamoorthy A: Studies on

anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1778:357–375. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Soman NR, Baldwin SL, Hu G, Marsh JN,

Lanza GM, Heuser JE, Arbeit JM, Wickline SA and Schlesinger PH:

Molecularly targeted nanocarriers deliver the cytolytic peptide

melittin specifically to tumor cells in mice, reducing tumor

growth. J Clin Invest. 119:2830–2842. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lee MT, Chen FY and Huang HW: Molecular

mechanism of Peptide-induced pores in membranes. Biochemistry.

43:3590–3599. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huh JE, Kang JW, Nam D, Baek YH, Choi DY,

Park DS and Lee JD: Melittin suppresses VEGF-A-induced tumor growth

by blocking VEGFR-2 and the COX-2-mediated MAPK signaling pathway.

J Nat Prod. 75:1922–1929. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shin JM, Jeong YJ, Cho HJ, Park KK, Chung

IK, Lee IK, Kwak JY, Chang HW, Kim CH, Moon SK, et al: Melittin

suppresses HIF-1α/VEGF expression through inhibition of ERK and

mTOR/p70S6K pathway in human cervical carcinoma cells. PLoS One.

8:e693802013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Pichia Expression Kit Version F. A Manual

of Methods for Expression of Recombinant Proteins in Pichia

pastoris. Invitrogen. 2002

|

|

20

|

Ciomber A, Smagur A, Mitrus I, Cichoń T,

Smolarczyk R, Sochanik A, Szala S and Jarosz M: Antitumor effects

of recombinant antivascular protein ABRaA-VEGF121 combined with

IL-12 gene therapy. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz). 62:161–168.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Xu WW, Li B, Lam AK, Tsao SW, Law SY, Chan

KW, Yuan QJ and Cheung AL: Targeting VEGFR1- and VEGFR2-expressing

non-tumor cells is essential for esophageal cancer therapy.

Oncotarget. 6:1790–1805. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Liu M, Zong J, Liu Z, Li L, Zheng X, Wang

B and Sun G: A novel melittin-MhIL-2 fusion protein inhibits the

growth of human ovarian cancer SKOV3 cells in vitro and in vivo

tumor growth. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 62:889–895. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Lee MT, Sun TL, Hung WC and Huang HW:

Process of inducing pores in membranes by melittin. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 110:14243–14248. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sommer A, Fries A, Cornelsen I, Speck N,

Koch-Nolte F, Gimpl G, Andrä J, Bhakdi S and Reiss K: Melittin

modulates keratinocyte function through P2 receptor-dependent ADAM

activation. J Biol Chem. 287:23678–23689. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Qu L, Jiang M, Li Z, Pu F, Gong L, Sun L,

Gong R, Ji G and Si J: Inhibitory effect of biosynthetic nanoscale

peptide Melittin on hepatocellular carcinoma, driven by survivin

promoter. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 10:695–706. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Jo M, Park MH, Kollipara PS, An BJ, Song

HS, Han SB, Kim JH, Song MJ and Hong JT: Anti-cancer effect of bee

venom toxin and melittin in ovarian cancer cells through induction

of death receptors and inhibition of JAK2/STAT3 pathway. Toxicol

Appl Pharmacol. 258:72–81. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liu H, Han Y, Fu H, Liu M, Wu J, Chen X,

Zhang S and Chen Y: Construction and expression of sTRAIL-melittin

combining enhanced anticancer activity with antibacterial activity

in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 97:2877–2884. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Su M, Chang W, Cui M, Lin Y, Wu S and Xu

T: Expression and anticancer activity analysis of recombinant human

uPA1-43-melittin. Int J Oncol. 46:619–626. 2015.

|

|

29

|

Wang DD, Su MM, Sun Y, Huang SL, Wang J

and Yan WQ: Expression, purification and characterization of a

human single-chain Fv antibody fragment fused with the Fc of an

IgG1 targeting a rabies antigen in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr

Purif. 86:75–81. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|